Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy In Brief

Changes from August 1, 2019 to September 19, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy In Brief

Contents

Summary

Afghanistan has beenwas elevated as a significant U.S. foreign policy concern sincein 2001, when the United States, in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, led a military campaign against Al Qaeda and the Taliban government that harbored and supported it. In the intervening 1718 years, the United States has suffered around 2,400 military fatalities in Afghanistan (including twelveseventeen in combat in 2019 to date) and Congress has appropriated approximately $133 billion for reconstruction there. In that time, an elected Afghan government has replaced the Taliban, and most measures of human development have improved, although future prospects of those measures remain mixed. The fundamental objective of U.S. efforts in Afghanistan is "preventing any further attacks on the United States by terrorists enjoying safe haven or support in Afghanistan."

In mid-Until September 2019, U.S. military engagement in Afghanistan appearsappeared closer to endingan end than perhaps ever before, as U.S. officials negotiatenegotiated directly with Taliban interlocutors on the issues of counterterrorism and the presence of some 14,000 U.S. troops. However, on September 7, 2019, President Trump announced that those talks, led by U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad, had been called off. It remains unclear under what conditions negotiations might be restarted. Afghan government representatives were not directly involved in those talks, leading some to worry that the United States wouldU.S. troops. U.S. negotiators report progress, but Afghan government representatives have not been directly involved. Lead U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad insists that the United States seeks a comprehensive peace agreement but some worry that the United States will prioritize a military withdrawal over a complex political settlement that preserves some of the social, political, and humanitarian gains made since 2001. It remains unclearObservers speculate about what kind of political arrangement, if any, could satisfy both Kabul and the Taliban to the extent that the latter fully abandons armed struggle.

President Trump has expressed his intention to withdraw U.S. forces from Afghanistan, though U.S. officials maintain that no policy decision has been made to reduce U.S. force levels. Many observers assess that a full-scale U.S. withdrawal would lead to the collapse of the Afghan government and perhaps even the reestablishment of Taliban control. By many measures, the Taliban are in a stronger military position now than at any point since 2001, though at least some once-public metrics related to the conduct of the war have been classified or are no longer produced (including district-level territorial and population control assessments, as of the April 30, 2019, quarterly report from the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction). Underlying the negotiations is the unsettled state of Afghan politics, which is a major complicating factor: the all-important presidential election, originally slated for April 2019, has been postponed twice and is now scheduled for September 2019.

For additional information on Afghanistan and U.S. policy there, see CRS Report R45818, Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy, by Clayton Thomas. For background information and analysis on the history of congressional engagement with Afghanistan and U.S. policy there, as well as a summary of recent Afghanistan-related legislative proposals, see CRS Report R45329, Afghanistan: Legislation in the 115th CongressIssues for Congress and Legislation 2017-2019, by Clayton Thomas.

Overview

The U.S. and Afghan governments, along with partner countries, remain engaged in combat with a robust Taliban-led insurgency. While U.S. military officials maintain that Afghan forces are "resilient" against the Taliban,1 by some measures insurgents are in control of or contesting more territory today than at any point since 2001.2 The conflict also involves an array of other armed groups, including active affiliates of both Al Qaeda (AQ) and the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIS, ISIL, or by the Arabic acronym Da'esh). Since early 2015, the NATO-led mission in Afghanistan, known as "Resolute Support Mission" (RSM), has focused on training, advising, and assisting Afghan government forces; combat operations by U.S. counterterrorism forces, along with some partner forces, also continue. These two "complementary missions" make up Operation Freedom's Sentinel (OFS).3

SimultaneouslyAlongside the military campaign, the United States iswas engaged in a diplomatic effort to end the war, most notably through direct talks with Taliban representatives (a reversal of previous U.S. policy). A draft framework, in which the Taliban would prohibit terrorist groups from operating on Afghan soil in return for the eventual withdrawal of U.S. forces, was reached between U.S. and Taliban negotiators in January 2019, though lead U.S. negotiator Zalmay Khalilzad insists that "nothing is agreed until everything is agreed."4 Negotiations do not, as of August 2019, directly involve representatives of the Afghan governmentHowever, on September 7, 2019, President Trump announced that those talks had been called off. It remains unclear under what conditions negotiations might be restarted. Afghan government representatives were not directly involved in those talks, leading some Afghans to worry that the United States willwould prioritize a military withdrawal over a complex political settlement that preserves some of the social, political, and humanitarian gains made since 2001.

Underlying the negotiationsFurther complicating U.S. policy is the unsettled state of Afghan politics, which is a major complicating factor: Afghanistan held inconclusive parliamentary elections in October 2018 and the all-important presidential election, originally scheduled for April 2019, has now been postponed until September 28, 2019. The Afghan government has made some progress in reducing corruption and implementing its budgetary commitments, but faces domestic criticism for its failure to guarantee security and prevent insurgent gains.

The United States has spent approximately $133 billion in various forms of aid to Afghanistan over the past decade and a half, from building up and sustaining the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) to economic development. This assistance has increased Afghan government capacity, but prospects for stability in Afghanistan appear distant. Some U.S. policymakers still hope that the country's largely underdeveloped natural resources and/or geographic position at the crossroads of future global trade routes might improve the economic life of the country, and, by extension, its social and political dynamics as well. Nevertheless, Afghanistan's economic and political outlook remains uncertain, if not negative, in light of ongoing hostilities.

U.S.-Taliban Negotiations

In August 2017, President Trump announced what he termed a new South Asia strategy in a nationally-televised address. Many Afghan and U.S. observers interpreted the speech and the policies it promised (expanded targeting authorities for U.S. forces, greater pressure on Pakistan, a modest increase in the number of U.S. and international troops) as a sign of renewed U.S. commitment.5 However, after less than a year of continued military stalemate, the Trump Administration in July 2018 reportedly ordered the start of direct talks with the Taliban that did not include the Afghan government. This represented a dramatic reversal of U.S. policy, which had previously been to support an "Afghan-led, Afghan-owned" peace process.6

In September 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo appointed former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad to the newly-created post of Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation; Khalilzad has since met several times with Taliban representatives in Doha, Qatar (where the group maintains a political office). He has also had consultations with the Afghan, Pakistani, and other regional governments.

After a six-day seriesFor almost a year, Khalilzad held a near-continuous series of meetings with Taliban representatives, along with consultations with the Afghan, Pakistani, and other regional governments. After six days of negotiations in Doha in late January 2019, Khalilzad stated that, "The Taliban have committed, to our satisfaction, to do what is necessary that would prevent Afghanistan from ever becoming a platform for international terrorist groups or individuals," in return for which U.S. forces would eventually fully withdraw from the country.7 Khalilzad later cautioned that "we made significant progress on two vital issues: counter terrorism and troop withdrawal. That doesn't mean we're done. We're not even finished with these issues yet, and there is still work to be done on other vital issues like intra-Afghan dialogue and a complete ceasefire."8 After a longer series of talks that ended on March 12, 2019, Khalilzad announced that an agreement "in draft" had been reached on counterterrorism assurances and U.S. troop withdrawal. He noted that after the agreement iswas finalized, "the Taliban and other Afghans, including the government, will begin intra-Afghan negotiations on a political settlement and comprehensive ceasefire."8 During a trip to Kabul in June 2019, Secretary of State Pompeo stated, "I hope we have a peace deal before September 1. That's certainly our mission set."9

Kabul is not directly involved in the ongoing U.S.-Taliban negotiations: the Taliban have long refused to negotiate with representatives of the Afghan government, which they characterize as a corrupt and illegitimate puppet of foreign powers.10 That refusal, along with continued Taliban attacks, have led some to call for the United States to suspend talks until the Taliban make concessions on one or both issues.11

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani has promised that his government will not accept any settlement that limits Afghans' rights. In a January 2019 televised address, he further warned that any agreement to withdraw U.S. forces that did not include Kabul's participation could lead to "catastrophe," pointing to the 1990s-era civil strife following the fall of the Soviet-backed government that led to the rise of the Taliban.12 A meeting between several dozen Afghans and 17 Taliban representatives took place in July 2019; the Afghan delegation included some government officials, who participated in a personal capacity. The two-day "Intra-Afghan Conference for Peace" concluded with a joint statement that stressed the importance of an intra-Afghan settlement, and was hailed by Khalilzad as a "big success."13

It remains unclear what kind of political arrangement could satisfy both Kabul and the Taliban to the extent that the latter fully abandons armed struggle in pursuit of its goals. The Taliban have given some more conciliatory signs, with one spokesman saying in January 2019 that the group is "not seeking a monopoly on power."14 Still, many Afghans, especially women, who remember Taliban rule and oppose the group's tactics and beliefs, remain wary.15

Afghan Political Situation

By August 2019, the process appeared to be reaching its conclusion, with multiple reports detailing the outlines of an emerging U.S.-Taliban arrangement.10 In a September 2, 2019 interview with Afghanistan's TOLOnews, Special Representative Khalilzad confirmed "we have reached an agreement in principal" in which the United States would withdraw about 5,000 of its 14,000 troops from five bases within 135 days if the Taliban reduces violence in two key provinces. U.S. troops would gradually be withdrawn from Afghanistan entirely within 16 months, or by the end of 2020; the removal of foreign forces is the key Taliban demand. It is less clear what specific concessions the Taliban would make in return. As part of the tentative deal, U.S. officials reportedly "expected" the Taliban to enter direct negotiations with the Afghan government after a U.S. withdrawal begins, but the Taliban have not publicly reversed their long-standing refusal to negotiate with Kabul, and the U.S. arguably has little leverage to compel them to do so once a U.S. withdrawal takes place.11 On September 7, 2019, President Trump revealed in a series of tweets that he had invited "major Taliban leaders" and Afghan President Ashraf Ghani to meet with him separately at Camp David on the following day. He wrote that, because a Taliban attack killed several people, including a U.S. soldier, in Kabul on September 5, he "immediately cancelled the meeting and called off peace negotiations."12 The surprise announcement, which reportedly caught even some senior White House officials off guard, raises questions about Trump Administration policy going forward.13 In interviews the day after the President's tweets, Secretary Pompeo said that "we were close," but "the Taliban failed to live up to a series of commitments they had made," leading President Trump to walk away from the deal.14 Secretary Pompeo also stated that a U.S. troop withdrawal, along the lines outlined above, was still a possibility. That course of action was reportedly favored by former National Security Advisor Bolton, who reportedly advocated reducing U.S. forces without concluding a deal with the Taliban, which Bolton argued could not be trusted.15 That view is echoed by some analysts who argue, as former U.S. diplomat Laurel Miller did, "if all the United States wanted to do was withdraw from Afghanistan, it doesn't need to make a deal with the Taliban to do it. It can just do it…The only value of a U.S.-Taliban deal is if it is a prelude to an actual peace process among Afghans."16 It is not clear why the September 5 attack would have prompted President Trump to cancel the negotiations; 17 U.S. troops have been killed in combat in 2019 so far and the Taliban have conducted multiple large-scale bombings of civilian targets during the talks in Doha (alongside their military campaign against Afghan forces). Other potential motivating factors include negative reactions to the prospective deal from some Members of Congress.17 The commander of U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), General Kenneth McKenzie, stated that going forward, U.S. operations against the Taliban will increase across "a total spectrum," from air strikes to ground raids, commensurate with Taliban attacks.18 Secretary Pompeo added that "we're not going to reduce our support for the Afghan Security Forces," and claimed "over a thousand Taliban" had been killed in the last ten days.19 Some U.S. analysts argue that the President's publicly stated desire for a U.S. withdrawal undermines negotiations, with one observer asking, "Why would the Taliban give up anything in exchange for something the president has already said he wants to do?"20 In July 2019, Secretary Pompeo said that his "directive" from President Trump was to bring about the reduction of U.S. troops before the 2020 U.S. presidential election; he later stated that "there is no deadline" for the U.S. military mission.21 Afghans opposed to the Taliban doubt the group's trustworthiness, and express concern that, in the absence of U.S. military pressure, the group will have little incentive to comply with the terms of an agreement, the most crucial aspect of which would arguably be concluding a comprehensive political settlement with the Afghan government.22 Afghan President Ghani has promised that his government will not accept any settlement that limits Afghans' rights. In a January 2019 televised address, he further warned that any agreement to withdraw U.S. forces that did not include Kabul's participation could lead to "catastrophe," pointing to the 1990s-era civil strife following the fall of the Soviet-backed government that led to the rise of the Taliban.23 Going forward, it remains unclear what kind of political arrangement could satisfy both Kabul and the Taliban to the extent that the latter fully abandons its armed struggle. The Taliban have given contradictory signs, with one spokesman saying in January 2019 that the group is "not seeking a monopoly on power," and another in May speaking of the group's "determination to re-establish the Islamic Emirate in Afghanistan."24 Still, many Afghans – especially women – who remember Taliban rule and oppose the group's policies and beliefs remain wary.25The unsettled state of Afghan politics is a major complicating factor for current negotiations. The leadership partnership (referred to as the national unity government) between President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Abdullah Abdullah, which was brokered by the United States in the wake of the disputed 2014 election, has encountered challenges but remains intact. However, a trend in Afghan society and governance that worries some observers is increasing political fragmentation along ethnic lines.16 Such fractures have long existed in Afghanistan but were relatively muted during Hamid Karzai's presidency.17 These divisions are sometimes seen as a driving force behind some of the political upheavals that have challenged Ghani's government.189

Afghanistan held parliamentary elections in October 2018 that were marred by logistical, administrative, and security problems; the new parliament was inaugurated in April 2019 but the lower house quickly fell into a months-long dispute, including physical confrontation between parliamentarians, over the election of a speaker.1929 The all-important presidential election, originally scheduled for April 2019, has now been postponed twice, until September 2019. It is unclear to what extent, if any, those delays are related to ongoing U.S.-Taliban talks.20 U.S. officials have denied that the establishment of an interim government is part of their negotiations with the Taliban, but some observers speculate that such an arrangement (which Ghani has rejected) might be necessary to accommodate the reentry of Taliban figures into public life and facilitate the establishment of a new political system, which a putative settlement might require.21

Military and Security Situation

Since early 2015, the NATO-led mission in Afghanistan of 17,000 troops, known as "Resolute Support Mission" (RSM), has focused on training, advising, and assisting Afghan government forces. Combat operations by U.S. forces also continue and have increased in number since 2017. These two "complementary missions" comprise Operation Freedom's Sentinel (OFS).22.32 There are around 14,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan, of which approximately 8,500 are part of RSM. The remaining 8,700 troops of RSM come from 38 partner countries.

|

|

|

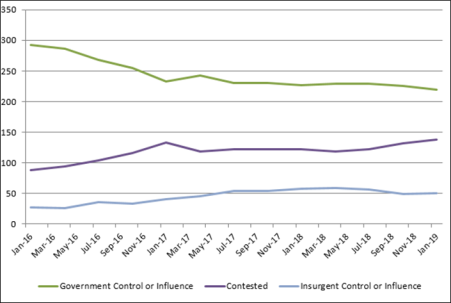

Source: SIGAR Quarterly Reports. Notes: The y-axis represents the number of districts, of which the U.S. government counts 407 in Afghanistan. |

Since at least early 2017, U.S. military officials have publicly stated that the conflict is "largely stalemated."

Source: SIGAR Quarterly Reports. Notes: The y-axis represents the number of districts, of which the U.S. government counts 407 in Afghanistan.2333 Arguably complicating that assessment, the extent of territory controlled or contested by the Taliban has steadily grown in recent years by most measures (see Figure 1). In its January 30, 2019, report, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) reported that the share of districts under government control or influence fell to 53.8%, as of October 2018. This figure, which marks a slight decline from previous reports, is the lowest recorded by SIGAR since tracking began in November 2015; 12% of districts are under insurgent control or influence, with the remaining 34% contested.2434

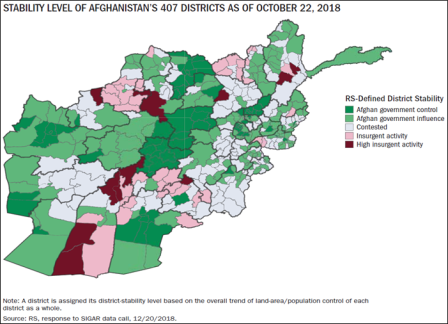

According to SIGAR's April 30, 2019, quarterly report, the U.S. military is "no longer producing its district-level stability assessments of Afghan government and insurgent control and influence." This information, which was in every previous SIGAR quarterly report going back to January 2016, estimated the extent of Taliban control and influence in terms of both territory and population, and was accompanied by charts portraying those trends over time along with a color-coded map of control/influence by district (see Figure 2). SIGAR reports that it was told by the U.S. military that the assessment is no longer being produced because it "was of limited decision-making value to the [U.S.] Commander."25

|

|

|

Source: SIGAR, January 30, 2019, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress. |

While the Taliban retain the ability to conduct high-profile urban attacks, they also demonstrate considerable tactical capabilities.

Source: SIGAR, January 30, 2019, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress.2636 Reports indicate that ANDSF fatalities have averaged 30-40 a day in recent months, and President Ghani stated in January 2019 that over 45,000 security personnel had paid "the ultimate sacrifice" since he took office in September 2014.2737 Insider attacks on U.S. and coalition forces by Afghan nationals are a sporadic, but persistent, problem—several U.S. servicemen died in such attacks in 2018, as did 85 Afghan soldiers.2838 In October 2018, General Miller was present at an attack inside the Kandahar governor's compound by a Taliban infiltrator who killed a number of provincial officials, including the powerful police chief Abdul Raziq; Miller was unhurt but another U.S. general was wounded.2939

Beyond the Taliban, a significant share of U.S. operations are aimed at the local Islamic State affiliate, known as Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP, also known as ISIS-K). ISKP and Taliban forces have sometimes fought over control of territory or because of political or other differences.3040 U.S. officials are reportedly tracking attempts by IS fighters fleeing Iraq and Syria to enter Afghanistan, which may represent a more permissive operating environment.3141 Some U.S. officials have stated that ISKP aspires to conduct attacks in the west, though there is reportedly disagreement within the U.S. government about the nature of the threat.42 ISKP also has claimed responsibility for a number of large-scale attacks, many targeting Afghanistan's Shia minority. Some raise the prospect of Taliban hardliners defecting to ISKP in the event that Taliban leaders agree to a political settlement or to continued U.S. counterterrorism presence.3243 The UN reports that Al Qaeda, while degraded in Afghanistan and facing competition from ISKP, "remains a longer-term threat."33

ANDSF Development and Deployment

The effectiveness of the ANDSF is key to the security of Afghanistan. As of June 2019, SIGAR reports that Congress has appropriated at least $82.7 billion for Afghan security since 2002.3445 Since 2014, the United States generally has provided around 75% of the estimated $5-6 billion a year to fund the ANDSF, with the balance coming from U.S. partners ($1 billion annually) and the Afghan government ($500 million).

Concerns about the ANDSF raised by SIGAR, the Department of Defense, and others include

- absenteeism, the fact that about 35% of the force does not reenlist each year, and the potential for rapid recruitment to dilute the force's quality;

- widespread illiteracy within the force;

3546 - credible allegations of child sexual abuse and other potential human rights abuses;

3647 and - casualty rates often described as unsustainable.

Total ANDSF strength was reported at 272,000 in May 2019, a decrease of about 11% since the previous quarter; the U.S. military stated that the reason for the decrease "is not known."3748 Other metrics related to ANDSF performance, including casualty and attrition rates, were classified by U.S. Forces-Afghanistan (USFOR-A) starting with the October 2017 SIGAR quarterly report, citing a request from the Afghan government. Although SIGAR had previously published those metrics as part of its quarterly reports, they remain withheld.3849 In both legislation and public statements, some Members have expressed concern over the decline in the types and amount of information made public by the executive branch. In both legislation and public statements, some Members have expressed concern over the decline in the types and amount of information made public by the executive branch.

U.S. Troop Levels and Authorities

At a February 2017 Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, then-mission commander of Resolute Support Mission General Nicholson indicated that the United States had a "shortfall of a few thousand" troops that, if filled, could help break the "stalemate."39 In June 2017, President Trump delegated to then-Secretary Mattis the authority to set force levels, reportedly limited to around 3,500 additional troops, in June 2017; Secretary Mattis signed orders to deploy them in September 2017.40 Those additional forces put the total number of U.S. troops in the country at around 14,000.41

Some reports in late 2018 and early 2019 indicate that President Trump may be contemplating ordering the withdrawal of some U.S. forces from Afghanistan.42 Still, U.S. officials maintain that no policy decision has been made to reduce U.S. force levels. In February 2019, the Senate passed S. 1, which includes language (Section 408) warning against a "precipitous withdrawal" of U.S. forces from Afghanistan and Syria.43 In July 2019, Secretary Pompeo said in an interview that his "directive" from President Trump was to bring about the reduction of U.S. forces before the 2020 U.S. presidential election, before later stating that "there is no deadline" for the U.S. military mission.44

|

NATO Contribution The current train, advise, and assist mission in Afghanistan, Resolute Support Mission (RSM), is led by NATO, and NATO partners have been heavily engaged in Afghanistan since 2001. At its height in 2012, the number of NATO and non-NATO partner forces reached 130,000, around 100,000 of whom were American. As of June 2019, RSM is made up of around 17,100 troops from 39 countries, of whom 8,475 are American. This represents an increase of nearly 4,000 troops from NATO and other partner countries since January 2017. At the NATO summit in July 2018, NATO leaders extended their financial commitment to Afghan forces to 2024 (previously 2020).45 |

Additionally, U.S. forces now have broader authority to operate independently of Afghan forces and "attack the enemy across the breadth and depth of the battle space," expanding the list of targets to include those related to "revenue streams, support infrastructure, training bases, infiltration lanes."46 This was demonstrated in a series of operations, beginning in the fall of 2017, against Taliban drug labs. These operations, often highlighted by U.S. officials, sought to degrade what is widely viewed as one of the Taliban's most important sources of revenue, namely the cultivation, production, and trafficking of narcotics.47 Some have questioned the impact of that campaign, which came to an end in late 2018.48 In November 2018, the United Nations reported that the total area used for poppy cultivation in 2018 was 263,000 hectares, the second-highest level recorded since monitoring began in 1994.49

Regional Dynamics: Pakistan and Other Neighbors

Regional dynamics, and the involvement of outside powers, are central to the conflict in Afghanistan. The neighboring state widely considered most important in this regard is Pakistan, which has played an active, and by many accounts negative, role in Afghan affairs for decades. Pakistan's security services maintain ties to Afghan insurgent groups, most notably the Haqqani Network, a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) that has become an official, semiautonomous component of the Taliban.50 Afghan leaders, along with U.S. military commanders, attribute much of the insurgency's power and longevity either directly or indirectly to Pakistani support; President Trump has accused Pakistan of "housing the very terrorists that we are fighting."51 U.S. officials have long identified militant safe havens in Pakistan as a threat to security in Afghanistan, though some Pakistani officials dispute that charge and note the Taliban's increased territorial control within Afghanistan itself.52

Pakistan may view a weak and destabilized Afghanistan as preferable to a strong, unified Afghan state (particularly one led by an ethnic Pashtun-dominated government in Kabul; Pakistan has a large and restive Pashtun minority).53 However, instability in Afghanistan could rebound to Pakistan's detriment; Pakistan has struggled with indigenous Islamist militants of its own. Afghanistan-Pakistan relations are further complicated by the presence of over a million Afghan refugees in Pakistan, as well a long-running and ethnically-tinged dispute over their shared 1,600-mile border.54 Pakistan's security establishment, fearful of strategic encirclement by India, apparently continues to view the Afghan Taliban as a relatively friendly and reliably anti-India element in Afghanistan. India's diplomatic and commercial presence in Afghanistan—and U.S. rhetorical support for it—exacerbates Pakistani fears of encirclement. Indian interest in Afghanistan stems largely from India's broader regional rivalry with Pakistan, which impedes Indian efforts to establish stronger and more direct commercial and political relations with Central Asia.

In his August 2017 speech, President Trump announced what he characterized as a new approach to Pakistan, saying, "We can no longer be silent about Pakistan's safe havens for terrorist organizations, the Taliban, and other groups that pose a threat to the region and beyond."55 He also, however, praised Pakistan as a "valued partner," citing the close U.S.-Pakistani military relationship. In January 2018, the Trump Administration announced plans to suspend security assistance to Pakistan, a decision that has affected billions of dollars in aid.56

Since late 2018, the Trump Administration has been seeking Islamabad's assistance in facilitating U.S. talks with the Taliban. One important action taken by Pakistan was the October 2018 release of Taliban co-founder Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, who was captured in Karachi in a joint U.S.-Pakistani operation in 2010. Khalilzad, who has since met with Baradar several times in Doha, said in February 2019 that Baradar's release "was my request," and later thanked Pakistan for facilitating the travel of Taliban figures to talks in Doha.57 The Administration has since given differing accounts of Pakistan's stance. In April 2019, the State Department reported to Congress that, "While Pakistan has taken some limited, reversible actions in support of the [U.S.] South Asia strategy…we have not seen it take the sustained, irreversible actions that would warrant lifting the [security aid] suspension."58 A biannual Department of Defense report on Afghanistan released in July 2019 asserted that "Pakistan is actively supporting Afghan reconciliation."59

Afghanistan largely maintains cordial ties with its other neighbors, includingnotably the post-Soviet states of Central Asia, though some warn that rising instability in Afghanistan may complicate those relationswhose role in Afghanistan has been relatively limited but could increase.60 In the past two years, multiple U.S. commanders have warned of increased levels of assistance, and perhaps even material support, for the Taliban from Russia and Iran, both of which cite IS presence in Afghanistan to justify their activities.61 Both nations were opposed to the Taliban government of the late 1990s, but reportedly see the Taliban as a useful point of leverage vis-a-vis the United States. Afghanistan may also represent a growing priority for China in the context of broader Chinese aspirations in Asia and globally.62

President Trump mentioned neither Iran nor Russia in his August 2017 speech, and it is unclear how, if at all, the U.S. approach to them might have changed as part of the new strategy. Afghanistan may also represent a growing priority for China in the context of broader Chinese aspirations in Asia and globally.63 In his speech, President Trump did encourage India to play a greater role in Afghan economic development; this, along with other Administration messaging, has compounded Pakistani concerns over Indian activity in Afghanistan.64 India has been the largest regional contributor to Afghan reconstruction, but New Delhi has not shown an inclination to pursue a deeper defense relationship with Kabul.

Economy and U.S. Aid

Economic development is pivotal to Afghanistan's long-term stability, though indicators of future growth are mixed. Decades of war have stunted the development of most domestic industries, including mining.65 The economy has also been hurt by a steep decrease in the amount of aid provided by international donors. Afghanistan's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has grown an average of 7% per year since 2003, but growth slowed to 2% in 2013 due to aid cutbacks and political uncertainty about the post-2014 security situation. Since 2015, Afghanistan has experienced a "slight recovery" with growth of between 2% and 3% in 2016 and 2017, though the increase in the poverty rate (55% living below the national poverty line in 2017 compared to 38% in 2012-2013) complicates that picture.66 Social conditions in Afghanistan remain equally mixed. On issues ranging from human trafficking67 to religious freedom to women's rights, Afghanistan has, by allsome accounts, made significant progress since 2001, but future prospects in these areas remain uncertain.

Congress has appropriated more than $132 billion in aid for Afghanistan since FY2002, with about 63% for security and 28% for development (and the remainder for civilian operations and humanitarian aid).68 In September 2019, the Administration announced that it would withhold $160 million in direct funding to the Afghan government for various development projects due to "the Afghan government's inability to transparently manage U.S. government resources" and "failure to meet benchmarks for transparency and accountability in public financial management."69

The Administration's FY2020 budget requests $4.8 billion for the ANDSF, $400 million in Economic Support Funds, and smaller amounts to help the Afghan government with tasks like combating narcotics trafficking.6970 This is down slightly from both the FY2019 request as well as the FY2018 enacted level of about $5.5 billion in total funding for Afghanistan (down from nearly $17 billion in FY2010). These figures do not include the cost of U.S. combat operations (including related regional support activities), which was estimated at a total of $756 billion since FY2001 as of March 2019, according to the DOD's Cost of War report, with approximately $45 billion requested for each of FY2018 and FY2019.7071 In its FY2020 budget request, the Pentagon identified $18.6 billion in direct war costs in Afghanistan, as well as $35.3 billion in "enduring theater requirements and related missions," though it is unclear how much of this latter figure is for Afghanistan versus other theaters.

Outlook

Insurgent and terrorist groups have demonstrated considerable capabilities in 2019, throwing into sharp relief the daunting security challenges that the Afghan government and its U.S. and international partners face. At the same time, hopesprospects for a negotiated settlement have risen, driven by direct U.S.-Taliban talks, though the prospects for such negotiations to deliver a settlement are uncertainare uncertain in light of the September 2019 cancelation of those negotiations and the Taliban's continued refusal to talk to the Afghan government.

U.S. policy has sought to force the Taliban to negotiate with the Afghan government by compelling the group to conclude that continued military struggle is futile in light of combined U.S., NATO, and ANDSF capabilities. It is still unclear, however, how the Taliban perceives its fortunes; given the group's recent battlefield gains, one observer has said that "the group has little reason to commit to a peace process: it is on a winning streak."7172

Observers differ on whether the Taliban pose an existential threat to the Afghan government, given the current military balance. That dynamic could change if the United States alters the level or nature of its troop deployments in Afghanistan or funding for the ANDSF. President Ghani has said, "[W]e will not be able to support our army for six months without U.S. [financial] support."7273 Notwithstanding direct U.S. support, Afghan political dynamics, particularly the willingness of political actors to directly challenge the legitimacy and authority of the central government, even by extralegal means, may pose a serious threat to Afghan stability in 2019 and beyond, regardless of Taliban military capabilities. Increased political instability, fueled by questions about the central government's authority and competence and rising ethnic tensions, may pose as serious a threat to Afghanistan's future as the Taliban does.73

A potential collapse of the Afghan military and/or the government that commands it could have significant implications for the United States, particularly given the nature of negotiated security arrangements. Regardless of how likely the Taliban would be to gain full control over all, or even most, of the country, the breakdown of social order and the fracturing of the country into fiefdoms controlled by paramilitary commanders and their respective militias may be plausible, even probable. Afghanistan experienced a similar situation nearly thirty years ago. Though Soviet troops withdrew from Afghanistan by February 1989, Soviet aid continued, sustaining the communist government in Kabul for nearly three years. However, the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991 ended that aid, and a coalition of mujahedin forces overturned the government in April 1992. Almost immediately, mujahedin commanders turned against each other, leading to a complex civil war during which the Taliban was founded, grew, and took control of most of the country, eventually offering sanctuary to Al Qaeda. While the Taliban and Al Qaeda are still "closely allied" according to the UN,7475 Taliban forces have clashed repeatedly with the Afghan Islamic State affiliate. Under a more unstable future scenario, alliances and relationships among extremist groups could evolve or security conditions could change, offering new opportunities to transnational terrorist groups whether directly or by default.

In light of these uncertainties, Members of Congress and other U.S. policymakers may reassess notions of what success in Afghanistan looks like, examining how potential outcomes might harm or benefit U.S. interests, and the relative levels of U.S. engagement and investment required to attain them.7576 The present condition, which is essentially a stalemate that has existed for several years, could persist; some argue that the United States "has the capacity to sustain its commitment to Afghanistan for some time to come" at current levels.7677 In May 2019, former National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster compared the U.S. effort in Afghanistan to an "insurance policy" against the negative consequences of the government's collapse.7778 Others counter that "the threat in Afghanistan doesn't warrant a continued U.S. military presence and the associated costs—which are not inconsequential."78

The Trump Administration has described U.S. policy in Afghanistan as "grounded in the fundamental objective of preventing any further attacks on the United States by terrorists enjoying safe haven or support in Afghanistan."7980 For years, some analysts have challenged that line of reasoning, describing it as a strategic "myth" and arguing that "the safe haven fallacy is an argument for endless war based on unwarranted worst-case scenario assumptions."8081 Some of these analysts and others dismiss what they see as a disproportionate focus on the military effort, citing evidence that "the terror threat to Americans remains low" to argue that "a strategy that emphasizes military power will continue to fail."8182

Core issues for Congress in Afghanistan include Congress's role in authorizing, appropriating funds for, and overseeing U.S. military activities, aid, and regional policy implementation. Additionally, Members of Congress may examine how the United States can leverage its assets, influence, and experience in Afghanistan, as well as those of Afghanistan's neighbors and international organizations, to encourage more equal, inclusive, and effective governance. Congress also could seek to help shape the U.S. approach to talks with the Taliban, or to potential negotiations aimed at altering the Afghan political system, through oversight, legislation, and public statements.8283

How Afghanistan fits into broader U.S. strategy is another issue on which Members might engage, especially given the Administration's focus on strategic competition with other great powers.8384 Some recognize fatigue over "endless wars" like that in Afghanistan but argue against a potential U.S. retrenchment that could create a vacuum Russia or China might fill.8485 Others describe the U.S. military effort in Afghanistan as a "peripheral war," and suggest that "the billions being spent on overseas contingency operation funding would be better spent on force modernization and training for future contingencies."8586

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Lolita C. Baldor and Matthew Pennington, "Attack in Afghanistan is Reminder of Formidable Task," Washington Post, October 20, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. |

SIGAR, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, January 30, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. |

"Operation Freedom's Sentinel, Quarterly Report to Congress, July 1 to September 30, 2018," Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations, November 19, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. |

Pamela Constable and Paul Sonne, "U.S.-Taliban Talks Appear Closer to Pact after Marathon Negotiations in Qatar," The Washington Post, January 26, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. |

Pamela Constable, "In Afghanistan, Trump's Speech Brings Relief to Some. To Others, 'It Means More War, Destruction,'" Washington Post, August 22, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. |

Mujib Mashal and Eric Schmitt, "White House Orders Direct Taliban Talks to Jump-Start Afghan Negotiations," New York Times, July 15, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. |

Mujib Mashal, "U.S. and Taliban Agree in Principle to Peace Framework, Envoy Says," New York Times, January 28, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. |

U.S. Special Representative Zalmay Khalilzad, Twitter, January 31, 2019. Available at https://twitter.com/US4AfghanPeace/status/1090944551500607488.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. |

Ryan Crocker, "I Was Ambassador to Afghanistan. This Deal is a Surrender," Washington Post, January 29, 2019; Husain Haqqani, "The Taliban Smell Blood," Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. |

Hasib Danish Alikozai and Mohammad Habibzada, "Afghans Worry as US Makes Progress in Taliban Talks," Voice of America, January 29, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. |

"Afghanistan talks agree 'roadmap to peace,'" BBC, July 9, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14. |

Kathy Gannon, "Taliban Say They Are Not Looking to Rule Afghanistan Alone," Associated Press, January 30, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. |

Cora Engelbrecht, "The Taliban Promise to Protect Women. Here's Why Women Don't Believe Them," New York Times, July 13, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. |

Frud Bezhan, "Leaked Memo Fuels New Allegations of Ethnic Bias in Afghan Government," RFERL, November 20, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17. |

See, for example, Azam Ahmed and Habib Zahori, "Afghan Ethnic Tensions Rise in Media and Politics," New York Times, February 18, 2014. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.

|

|

Donald J. Trump, Twitter, September 7, 2019. Available at https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1170469618177236992. 13.

|

|

Peter Baker, Mujib Mashal, and Michael Crowley, "How Trump's Plan to Secretly Meet With the Taliban Came Together, and Fell Apart," New York Times, September 8, 2019. 14.

|

|

Interview: Secretary Michael R. Pompeo With George Stephanopoulos of ABC's This Week, U.S. Department of State, September 8, 2019. 15.

|

|

Karen DeYoung, "Collapse of Afghanistan peace talks spotlights internal Trump administration divisions," Washington Post, September 8, 2019. 16.

|

|

Diaa Hadid, "In Afghanistan, A Mix Of Surprise And Relief After Trump Cancels Taliban Talks," NPR, September 9, 2019. 17.

|

|

Lindsey Graham and Jack Keane, "We can't outsource our security to anyone – especially the Taliban," Washington Post, August 28, 2019. 18.

|

|

Phil Stewart, "U.S. military likely to ramp up operations against Taliban: U.S. general," Reuters, September 9, 2019. 19.

|

|

Interview: Secretary Michael R. Pompeo With Jake Tapper of CNN's State of the Union, U.S. Department of State, September 8, 2019. 20.

|

|

Wesley Morgan, "How Trump trips up his own Afghan peace efforts," Politico, August 16, 2019. 21.

|

|

Leo Shane, "Pompeo backtracks on Afghanistan withdrawal by fall 2020," Military Times, July 31, 2019. 22.

|

|

Pamela Constable, "Afghans voice fears that the U.S. is undercutting them in deal with the Taliban," Washington Post, August 17, 2019. 23.

|

|

Hasib Danish Alikozai and Mohammad Habibzada, "Afghans Worry as US Makes Progress in Taliban Talks," Voice of America, January 29, 2019. 24.

|

|

Kathy Gannon, "Taliban Say They Are Not Looking to Rule Afghanistan Alone," Associated Press, January 30, 2019; Abdul Qadir Sediqi and Rupman Jain, "Taliban fighters double as reporters to wage Afghan digital war," Reuters, May 10, 2019. 25.

|

|

Pamela Constable, "The Return of a Taliban Government? Afghanistan Talks Raise Once-Unthinkable Question," Washington Post, January 29, 2019. 26.

|

|

Frud Bezhan, "Leaked Memo Fuels New Allegations of Ethnic Bias in Afghan Government," RFERL, November 20, 2017. 27.

|

|

See, for example, Azam Ahmed and Habib Zahori, "Afghan Ethnic Tensions Rise in Media and Politics," New York Times, February 18, 2014. |

Namely, contention with such powerbrokers as Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum, leader of the country's Uzbek minority; former Balkh governor Atta Mohammad Noor, prominent member of Afghanistan's major Tajik political party; and former President Hamid Karzai, who maintains support among some Afghans. |

|

Mujib Mashal and Jawad Sukhanyar, "Long, Rowdy Feud in Afghan Parliament Mirrors Wider Political Fragility," New York Times, June 19, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

32Pamela Constable, "With U.S.-Taliban peace talks canceled, Afghan president is on the hot seat," Washington Post, September 9, 2019. |

Gul Maqsood Sabit, "On the Verge of Peace, Afghanistan Needs a Carefully Managed Strategy," Diplomat, January 4, 2019; Ali Yawar Adili, "Afghanistan's 2019 Elections (1): The Countdown to the Presidential Election Has Kicked Off," Afghanistan Analysts Network, January 23, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Operation Freedom's Sentinel, Quarterly Report to Congress, July 1 to September 30, 2018," Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations, November 19, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ellen Mitchell, "Afghanistan War at a Stalemate, Top General Tells Lawmakers," The Hill, December 4, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

SIGAR, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, October 30, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

SIGAR, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, April 30, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alec Worsnop, "From Guerilla to Maneuver Warfare: A Look at the Taliban's Growing Combat Capability," Modern War Institute, June 6, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Afghanistan's Ghani says 45,000 Security Personnel Killed Since 2014," BBC, January 25, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Richard Sisk, "85 Afghan Troops Killed in Insider Attacks This Year, Report Finds," Military.com, November 5, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pamela Constable and Sayed Salahuddin, "U.S. Commander in Afghanistan Survives Deadly Attack at Governor's Compound That Kills Top Afghan Police General," Washington Post, October 18, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See, for example, Amira Jadoon, et al., "Challenging the ISK Brand in Afghanistan-Pakistan: Rivalries and Divided Loyalties," CTC Sentinel, Vol. 11, Issue 4, April 26, 2018; Najim Rahim and Rod Nordland, "Taliban Surge Routs ISIS in Northern Afghanistan," New York Times, August 1 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"ISIS terrorists heading to Afghanistan from Syria and Iraq to plot attacks," Khaama Press, April 30, 2019. In April 2018, a U.S. air strike killed the ISKP leader (himself a former Taliban commander) in northern Jowzjan province, which NATO described as "the main conduit for external support and foreign fighters from Central Asian states into Afghanistan." NATO Resolute Support Media Center, "Top IS-K Commander Killed in Northern Afghanistan," April 9, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

43.

Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Julian Barnes, "U.S. Military Calls ISIS in Afghanistan a Threat to the West. Intelligence Officials Disagree," New York Times, August 2, 2019. |

David Ignatius, "Uncertainty clouds the path forward in Afghanistan." Washington Post, July 22, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Twenty- |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

SIGAR, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, January 30, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

SIGAR reported in January 2014 that means of measuring the effectiveness of ANDSF literacy programs were "limited," and that judgment seems not to have changed in the years since. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See SIGAR Report 17-47, "Child Sexual Assault in Afghanistan: Implementation of the Leahy Laws and Reports of Assault by Afghan Security Forces," June 2017 (released on January 23, 2018). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

SIGAR, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, July 30, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Shawn Snow, "Report: US Officials Classify Crucial Metrics on Afghan Casualties, Readiness," Military Times, October 30, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39. |

Statement for the record by General John W. Nicholson, Commander, U.S. Forces – Afghanistan before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Situation in Afghanistan, February 9, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40. |

Tara Copp, "Mattis Signs Orders to Send about 3,500 More US Troops to Afghanistan," Military Times, September 11, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 41. |

As of September 30, 2017, the total number of active duty and reserve forces in Afghanistan was 15,298. Defense Manpower Data Center, Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country Quarterly Report, September 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 42. |

Dan Lamothe and Josh Dawsey, "Trump Wanted a Big Cut in Troops in Afghanistan. New U.S. Military Plans Fall Short," Washington Post, January 8, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 43. |

Patricia Zengerle, "Senate Breaks from Trump with Syria Troops Vote," Reuters, February 4, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44. |

Leo Shane, "Pompeo backtracks on Afghanistan withdrawal by fall 2020," Military Times, July 31, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45. |

Brussels Summit Declaration, issued July 11, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 46. |

Department of Defense Press Briefing by General Nicholson via teleconference from Kabul, Afghanistan, November 20, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 47. |

Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan estimated in a February 6, 2018, Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing that 65% of Taliban revenues are derived from narcotics. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 48. |

Kyle Rempfer, "Doubts Rise Over Effectiveness of Bombing Afghan Drug Labs," Military Times, February 5, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 49. |

"Afghanistan Opium Survey 2018," United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, November 19, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50. |

For more, see CRS In Focus IF10604, Al Qaeda and Islamic State Affiliates in Afghanistan, by Clayton Thomas. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 51. |

White House Office of the Press Secretary, Remarks by President Trump on the Strategy in Afghanistan and South Asia, August 21, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 52. |

Author interviews with Pakistani military officials, Rawalpindi, Pakistan, February 21, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 53. |

Pashtuns are an ethnic group that makes up about 40% of Afghanistan's 35 million people and 15% of Pakistan's 215 million; they thus represent a plurality in Afghanistan but are a relatively small minority among many others in Pakistan, though Pakistan's Pashtun population is considerably larger than Afghanistan's. Pakistan condemns as interference statements by President Ashraf Ghani (who is Pashtun) and other Afghan leaders about an ongoing protest campaign by Pakistani Pashtuns for greater civil and political rights. Ayaz Gul, "Afghan Leader Roils Pakistan With Pashtun Comments," Voice of America, February 7, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 54. |

About 2 million Afghan refugees have returned from Pakistan since the Taliban fell in 2011, but 1.4 million registered refugees remain in Pakistan, according to the United Nations, along with perhaps as many as 1 million unregistered refugees. Many of these refugees are Pashtuns ("Afghanistan's refugees: forty years of dispossession," Amnesty International, June 20, 2019). Pakistan, the United Nations, and others recognize the Durand Line as an international boundary, but Afghanistan does not. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 55. |

White House Office of the Press Secretary, Remarks by President Trump on the Strategy in Afghanistan and South Asia, August 21, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 56. |

Mark Landler and Gardiner Harris, "Trump, Citing Pakistan as a 'Safe Haven' for Terrorists, Freezes Aid," New York Times, January 4, 2018. Pakistan closed its ground and air lines of communication (GLOCs and ALOCs, respectively) to the United States after the latter suspended security aid during an earlier period of U.S.-Pakistan tensions in 2011-2012. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 57. |

"Mullah Baradar released by Pakistan at the behest of US: Khalilzad," The Hindu, February 9, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 58. |

Department of State, "Report to Congress on U.S. Security Assistance to Pakistan, P.L. 116-6," April 30, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 59. |

Department of Defense, Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan, July 12, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 60. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 61. |

In October 2018, the Trump Administration sanctioned several Iranian military officials for providing support to the Taliban. "Treasury and the Terrorist Financing Targeting Center Partners Sanction Taliban Facilitators and their Iranian Supporters," U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 23, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62. |

Thomas Ruttig, "Climbing on China's Priority List: Views on Afghanistan from Beijing," Afghanistan Analysts Network, April 10, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63. |

Thomas Ruttig, "Climbing on China's Priority List: Views on Afghanistan from Beijing," Afghanistan Analysts Network, April 10, 2018; Michael Martina, "Afghan Troops to Train in China, Ambassador Says," Reuters, September 6, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 64. |

Author interviews with Pakistani military and political officials, Islamabad and Rawalpindi, Pakistan, February 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 65. |

Much attention has been paid to Afghanistan's potential mineral and hydrocarbon resources, which by some estimates could be considerable but have yet to be fully explored or developed. Once estimated at nearly $1 trillion, the value of Afghan mineral deposits has since been revised downward, but those deposits reportedly have attracted interest from the Trump Administration. Mark Landler and James Risen, "Trump Finds Reason for the U.S. to Remain in Afghanistan: Minerals," New York Times, July 25, 2017. Additionally, Afghanistan's geographic location could position it as a transit country for others' resources. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 66. |

"Afghanistan," CIA World Factbook, last updated July 10, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67. |

Afghanistan was ranked as "Tier 2" in the State Department Trafficking in Persons Report for 2017, an improvement from 2016 when Afghanistan was ranked as "Tier 2: Watch List" on the grounds that the Afghan government was not demonstrating increased efforts against trafficking since the prior reporting period. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 68. |

SIGAR, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, January 30, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

69.

|

|

70.

U.S. Department of State, Statement on Accountability and Anti-Corruption in Afghanistan, September 19, 2019. |

For more, see CRS Report R45329, Afghanistan: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cost of War Update as of March 31, 2019. That figure includes the DOD contribution to reconstruction. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Michael Semple, "The Taliban's Battle Plan," Foreign Affairs, November 28, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Anwar Iqbal, "Afghan Army to Collapse in Six Months Without US Help: Ghani," Dawn, January 18, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sayed Salahuddin, "Strongman's Loyalists Show Taliban Isn't Only Threat in Afghanistan," Washington Post, July 4, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Twenty-second report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2368 (2017) concerning ISIL (Da'esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities, United Nations Security Council, July 27, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See, for example Jim Banks, "The Public Deserves an Afghanistan War Progress Report," National Review, October 23, 2018; Seth Jones, "The U.S. Strategy in Afghanistan: The Perils of Withdrawal," Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 26, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Semple, op. cit. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kyle Rempfer, "H.R. McMaster Says The Public Is Fed A 'War-Weariness' Narrative That Hurts US Strategy," Military Times, May 9, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Charles Pena, "We Can't Win-and Don't Have To-In Afghanistan." Real Clear Defense, October 9, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

U.S. Department of State, "Integrated Country Strategy: Afghanistan," September 27, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A. Trevor Thrall and Erik Goepner, "Another Year of the War in Afghanistan," Texas National Security Review, September 11, 2018. See also Micah Zenko and Amelia Mae Wolfe, "The Myth of the Terrorist Safe Haven," Foreign Policy, January 26, 2015. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Erik Goepner, "In Afghanistan, the Withdrawal of U.S. Troops Is Long Overdue," Cato Institute, September 29, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Omar Samad, "A Pivotal Year Ahead for Afghanistan," Atlantic Council, November 27, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See CRS In Focus IF11139, Evaluating DOD Strategy: Key Findings of the National Defense Strategy Commission, by Kathleen J. McInnis. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eric Edelman, "The US Role In The Middle East In An Era Of Renewed Great Power Competition," Hoover Institution, April 2, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Benjamin Denison, "Confusion in the Pivot: The Muddled Shift from Peripheral War to Great Power Competition," War on the Rocks, February 12, 2019. |