Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy

Afghanistan has been a significant U.S. foreign policy concern since 2001, when the United States, in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, led a military campaign against Al Qaeda and the Taliban government that harbored and supported it. In the intervening 18 years, the United States has suffered approximately 2,400 military fatalities in Afghanistan, with the cost of military operations reaching nearly $750 billion. Congress has appropriated approximately $133 billion for reconstruction. In that time, an elected Afghan government has replaced the Taliban, and most measures of human development have improved, although Afghanistan’s future prospects remain mixed in light of the country’s ongoing violent conflict and political contention.

Topics covered in this report include:

Security dynamics. U.S. and Afghan forces, along with international partners, combat a Taliban insurgency that is, by many measures, in a stronger military position now than at any point since 2001. Many observers assess that a full-scale U.S. withdrawal would lead to the collapse of the Afghan government and perhaps even the reestablishment of Taliban control over most of the country. Taliban insurgents operate alongside, and in periodic competition with, an array of other armed groups, including regional affiliates of Al Qaeda (a longtime Taliban ally) and the Islamic State (a Taliban foe and increasing focus of U.S. policy).

U.S. military engagement. The size and goals of U.S. military operations in Afghanistan have evolved over the course of the 18-year war, the longest in American history. Various factors, including changes in the security situation and competing U.S. priorities, have necessitated adjustments. While some press reports indicate that the Trump Administration may be considering at least a partial withdrawal, U.S. officials maintain that no decision has been made to reduce U.S. force levels.

Regional context. Afghanistan has long been an arena for, and victim of, regional and great power competition. Pakistan’s long-standing, if generally covert, support for the Taliban makes it the neighbor whose influence is considered the most important. Other actors include Russia and Iran (both former Taliban foes now providing some measure of support to the group); India (Pakistan’s main rival); and China.

Reconciliation efforts. U.S. officials have long contended that there is no military solution to the war in Afghanistan. Direct U.S.-Taliban negotiations, ongoing since mid-2018, on the issues of counterterrorism and the presence of U.S. troops could offer greater progress than past efforts. However, U.S. negotiators caution that the Taliban’s continued refusal to negotiate with the Afghan government could preclude the stated U.S. goal of a comprehensive settlement.

Afghan governance and politics. Afghanistan’s democratic system has achieved some success since its post-2001 establishment, but corruption, an evident failure to provide sufficient security and services, and infighting between political elites has undermined it. The unsettled state of Afghan politics complicates ongoing efforts to negotiate a settlement: the presidential election has been postponed twice and is now scheduled for September 2019.

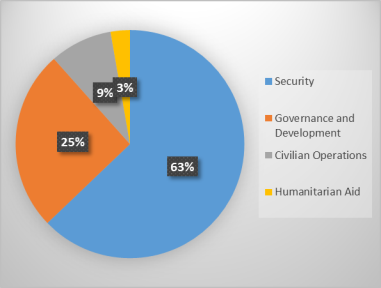

U.S. and foreign assistance. Military operations have been complemented by large amounts of development assistance; since 2001, Afghanistan has been the largest single recipient of U.S. aid. Most of that assistance has been for the Afghan military (a trend particularly pronounced in recent years), but aid has also supported efforts to build Afghan government capacity, develop the Afghan economy, and promote human rights.

Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Purpose and Scope

- Overview

- U.S. Military Operations

- September 11 and Start of Operation Enduring Freedom (2001-2009)

- Obama Administration: "Surge" and Drawdown (2009-2014)

- Bilateral Accords: Strategic Partnership Agreement (SPA) and Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA)

- Resolute Support Mission (2015-Present)

- Alterations to the Drawdown Schedule and Rules of Engagement

- Developments during the Trump Administration

- Security Dynamics: The Taliban and Other Armed Groups

- Taliban Insurgency

- Haqqani Network

- Islamic State-Khorasan Province

- Al Qaeda

- Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF)

- Regional Dimension

- Pakistan

- Iran

- India

- Russia

- China

- Persian Gulf States

- Multilateral Fora

- Reconciliation Efforts

- Afghan Government Initiatives

- U.S.-Taliban Talks

- Developments under the Trump Administration

- Afghan Governance and Politics

- Constitution and Political System

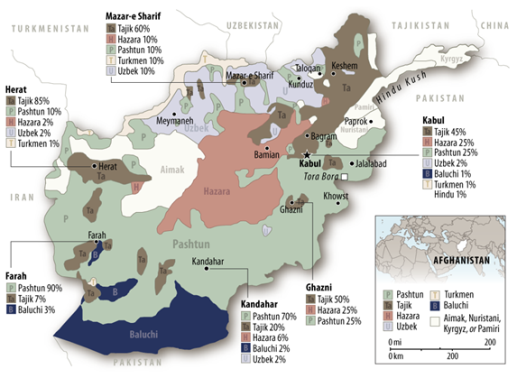

- Politics of Ethnicity and Elections

- Aid, Economic Development, and Human Rights

- U.S. Assistance to Afghanistan

- Aid Conditionality and Oversight

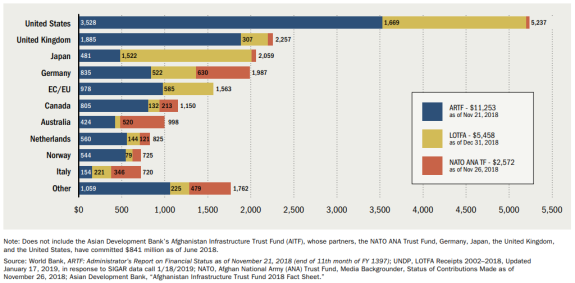

- Other International Donors and Multilateral Trust Funds

- Economic and Human Development

- Infrastructure

- Agriculture

- Mining and Gems

- Oil, Gas, and Related Pipelines

- Education

- Trade

- General Human Rights Issues

- Status of Women

- Religious Freedoms and Minorities

- Human Trafficking

- Outlook

Figures

- Figure 1. Afghanistan at a Glance

- Figure 2. U.S. Troop Levels in Afghanistan

- Figure 3. Control of Districts in Afghanistan Jan. 2016 to Jan. 2019

- Figure 4. Insurgent Activity in Afghanistan by District

- Figure 5. Map of Ethnicities in Afghanistan (2003)

- Figure 6. U.S. Funding for Reconstruction and Related Activities by Category

- Figure 7. SIGAR: Cumulative Contributions to ARTF, LOTFA, and NATO ANA TF

Summary

Afghanistan has been a significant U.S. foreign policy concern since 2001, when the United States, in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, led a military campaign against Al Qaeda and the Taliban government that harbored and supported it. In the intervening 18 years, the United States has suffered approximately 2,400 military fatalities in Afghanistan, with the cost of military operations reaching nearly $750 billion. Congress has appropriated approximately $133 billion for reconstruction. In that time, an elected Afghan government has replaced the Taliban, and most measures of human development have improved, although Afghanistan's future prospects remain mixed in light of the country's ongoing violent conflict and political contention.

Topics covered in this report include:

- Security dynamics. U.S. and Afghan forces, along with international partners, combat a Taliban insurgency that is, by many measures, in a stronger military position now than at any point since 2001. Many observers assess that a full-scale U.S. withdrawal would lead to the collapse of the Afghan government and perhaps even the reestablishment of Taliban control over most of the country. Taliban insurgents operate alongside, and in periodic competition with, an array of other armed groups, including regional affiliates of Al Qaeda (a longtime Taliban ally) and the Islamic State (a Taliban foe and increasing focus of U.S. policy).

- U.S. military engagement. The size and goals of U.S. military operations in Afghanistan have evolved over the course of the 18-year war, the longest in American history. Various factors, including changes in the security situation and competing U.S. priorities, have necessitated adjustments. While some press reports indicate that the Trump Administration may be considering at least a partial withdrawal, U.S. officials maintain that no decision has been made to reduce U.S. force levels.

- Regional context. Afghanistan has long been an arena for, and victim of, regional and great power competition. Pakistan's long-standing, if generally covert, support for the Taliban makes it the neighbor whose influence is considered the most important. Other actors include Russia and Iran (both former Taliban foes now providing some measure of support to the group); India (Pakistan's main rival); and China.

- Reconciliation efforts. U.S. officials have long contended that there is no military solution to the war in Afghanistan. Direct U.S.-Taliban negotiations, ongoing since mid-2018, on the issues of counterterrorism and the presence of U.S. troops could offer greater progress than past efforts. However, U.S. negotiators caution that the Taliban's continued refusal to negotiate with the Afghan government could preclude the stated U.S. goal of a comprehensive settlement.

- Afghan governance and politics. Afghanistan's democratic system has achieved some success since its post-2001 establishment, but corruption, an evident failure to provide sufficient security and services, and infighting between political elites has undermined it. The unsettled state of Afghan politics complicates ongoing efforts to negotiate a settlement: the presidential election has been postponed twice and is now scheduled for September 2019.

- U.S. and foreign assistance. Military operations have been complemented by large amounts of development assistance; since 2001, Afghanistan has been the largest single recipient of U.S. aid. Most of that assistance has been for the Afghan military (a trend particularly pronounced in recent years), but aid has also supported efforts to build Afghan government capacity, develop the Afghan economy, and promote human rights.

Purpose and Scope

The purpose of this report is to provide information and analysis for Congress on Afghanistan and the nearly two-decade U.S. project there. Topics covered include U.S. military engagement and security dynamics; the regional context; reconciliation efforts; Afghan politics and governance; foreign assistance; and social and economic development. Supplementary materials, including a historical timeline and background on the Soviet war in Afghanistan, are included as appendices. This information is meant to provide background and context for lawmakers as they consider administration budget requests, oversee U.S. military operations and aid programs, and examine the U.S. role in South Asia and the world. For a more frequently updated treatment of current events in Afghanistan and developments in U.S. policy, refer to CRS Report R45122, Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy In Brief, by Clayton Thomas.

|

|

General |

Area: 652,230 sq. km. (251,827 sq. mile), slightly smaller than Texas |

|

People and Society |

Population: 34,940,837 (July 2018 est.) Languages: Dari (official) 77%, Pashto (official) 48%, Uzbek 11%, English 6%, Turkmen 3%, Urdu 3%, others (e.g., Pashayi, Nuristani, Balochi), 1% (2017 est. of most widely spoken languages; shares sum to more than 100% because there is much bilingualism in the country and respondents were allowed to select more than one.) Religions: Muslim 99.7% (Sunni 84.7 - 89.7%, Shia 10 - 15%), other 0.3% (2009 est.) Median Age: 19 years Life expectancy: Male: 50.6 years Female: 53.6 years (2018 est.) Infant mortality rate (per 1000 births): 108.5 (2018 est.) Maternal mortality rate: 396 deaths per 100,000 live births (2015 est.) Adult literacy: 38.2% (2015 est.) Male: 52%, Female: 24.2% |

|

Economy |

GDP: growth rate: 2.7% (2017 est.) per capita: $2,000 (2017 est.) Unemployment: 23.9% (2017); Youth: 17.6% (2017) Population below the poverty line: 54.5% (2017 est.) Exports: $784 million (2017 est.); India 56.5%; Pakistan 29.6%; commodities: fruits and nuts, carpets, wool, cotton, precious and semi-precious gems Imports: $7.2 billion (December 2017 est.); China 21%, Iran 20.5%, Pakistan 11.8%, (2017); commodities: machinery and other capital goods, food, textiles, petroleum products |

Source: Graphic created by CRS. Fact information from CIA World Fact Book.

Overview

|

By the Numbers: U.S. Efforts in Afghanistan1 15,000: Current U.S. troop level (8,475 as part of NATO-led Resolute Support Mission, remainder counterterrorism) 898,696: Total number of U.S. troops deployed since 2002 (as of March 2018) 2,419: U.S. military fatalities (including 10 to date in 2019) $133 billion: Total U.S. reconstruction spending since FY2002 $5.4 billion: U.S. foreign assistance in FY2018 (including $4.7 billion in ASFF, $500 million in ESF, and $95 million in INCLE) $745 billion: Cost of U.S. military operations since 2002 $46.3 billion2: FY2019 request for Operation Freedom's Sentinel (OFS) |

The U.S. and Afghan governments, along with partner countries, remain engaged in combat with a robust Taliban-led insurgency. While U.S. military officials maintain that Afghan forces are "resilient" against the Taliban,3 by some measures insurgents are in control of or contesting more territory today than at any time since 2001.4 The conflict also involves an array of other armed groups, including active affiliates of both Al Qaeda (AQ) and the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIS, ISIL, or by the Arabic acronym Da'esh).

Since early 2015, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)-led mission in Afghanistan, known as "Resolute Support Mission" (RSM), has focused on training, advising, and assisting Afghan government forces. Combat operations by U.S. counterterrorism forces, along with some partner forces, have increased since 2017. These two "complementary missions" make up Operation Freedom's Sentinel (OFS).5

Simultaneously, the United States is engaged in a diplomatic effort to end the war, most notably through direct talks with Taliban representatives (a reversal of previous U.S. policy). In January 2019, U.S. and Taliban negotiators reached a draft framework, in which the Taliban would prohibit terrorist groups from operating on Afghan soil in return for the eventual withdrawal of U.S. forces, though lead U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad insists that "nothing is agreed until everything is agreed."6 As of July 2019, negotiations do not directly involve representatives of the Afghan government, leading some Afghans to worry that the United States will prioritize a military withdrawal over a complex political settlement that preserves some of the social, political, and humanitarian gains made since 2001. A major complicating factor underlying the negotiations is the unsettled state of Afghan politics; Afghanistan held inconclusive parliamentary elections in October 2018 and the presidential election, originally scheduled for April 2019, has been postponed until September 2019. The Afghan government has made some notable progress in reducing corruption and implementing its budgetary commitments, but faces domestic criticism for its failure to guarantee security and prevent insurgent gains.

The United States has spent more than $132 billion in various forms of reconstruction aid to Afghanistan over the past decade and a half, from building up and sustaining the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) to economic development. This assistance has increased Afghan government capacity, but prospects for stability in Afghanistan still appear distant. Some U.S. policymakers hope that the country's largely underdeveloped natural resources and geographic position at the crossroads of future global trade routes might improve the economic life of the country, and, by extension, its social and political dynamics. Nevertheless, in light of the ongoing hostilities Afghanistan's economic and political prospects remain uncertain at best.

U.S. Military Operations

September 11 and Start of Operation Enduring Freedom (2001-2009)

On September 11, 2001, the United States suffered a series of coordinated terrorist attacks executed by the Islamist terrorist group Al Qaeda. Al Qaeda leadership was based in Afghanistan and protected by the Taliban government that ruled most of that country (see textbox below). U.S. President George W. Bush articulated a policy that equated those who harbor terrorists with terrorists themselves, and asserted that a friendly regime in Kabul was needed to enable U.S. forces to search for Al Qaeda members there.

|

Taliban: Rise to Power In 1993-1994, Afghan Islamic clerics and students, mostly of rural, Pashtun origin, formed the Taliban movement. Many were former anti-Soviet fighters known as mujahideen who had become disillusioned with conflict among mujahideen parties that arose after the Soviet withdrawal and who had moved into Pakistan to study in Islamic seminaries ("madrassas") mainly of the conservative "Deobandi" school of Islam.7 Taliban practices were also consonant with conservative Pashtun tribal traditions. The Taliban's leader, Mullah Muhammad Omar, had been a mujahideen fighter during the Soviet occupation, though the party with which he was affiliated was generally seen as moderately Islamist at that time. Like Omar, most of the senior figures in the Taliban regime were Ghilzai Pashtuns, one of the major Pashtun tribal confederations; most modern Afghan rulers have been from the Durrani tribal confederation. The Taliban viewed the post-Soviet government of Burhanuddin Rabbani as weak, corrupt, and anti-Pashtun. The four years of civil war between the mujahideen groups (1992-1996) created popular support for the Taliban as they were seen as less corrupt and more able to deliver stability.8 The Taliban began by taking control of the southern city of Kandahar in November 1994 and the movement captured Kabul on September 27, 1996. The Taliban lost international and domestic support as it imposed strict adherence to Islamic customs in areas it controlled and employed harsh punishments, including public executions, to enforce strict Islamic practices, including bans on television, Western music, and dancing. It prohibited women from attending school or working outside the home, except in health care, and publicly executed some women for alleged adultery. In March 2001 the Taliban blew up the monumental sixth century Buddha statues carved into hills above Bamyan city, considering them idols. The Taliban's hosting of Al Qaeda's leadership gradually became the overriding U.S. concern with the Taliban. Omar reportedly forged a political and personal bond with Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, who relocated to Afghanistan from Sudan in May 1996. Omar refused U.S. demands to extradite bin Laden. After the August 7, 1998, Al Qaeda bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, the Clinton Administration increased pressure on the Taliban to extradite bin Laden by imposing U.S. sanctions on Afghanistan, achieving adoption of some U.N. sanctions as well, and firing cruise missiles at Al Qaeda training camps in eastern Afghanistan. |

On September 14, 2001, in Congress, S.J.Res. 23 (P.L. 107-40), passed 98-0 in the Senate and with no objections in the House, authorized the use of military force, stating that:

[t]he President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001 or harbored such organizations or persons in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

The Administration also sought United Nations (U.N.) backing for military action. On September 12, 2001, the U.N. passed Security Council Resolution 1368, expressing the Council's "readiness to take all necessary steps to respond to the September 11 attacks."9

When the Taliban refused the Bush Administration's demand to extradite Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, the Administration launched military operations against the Taliban to "disrupt the use of Afghanistan as a terrorist base of operations, and to attack the military capability of the Taliban regime."10

Combat operations in Afghanistan began on October 7, 2001, with the launch of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). Initial military operations initially consisted primarily of U.S. air strikes on Taliban and Al Qaeda forces, facilitated by the cooperation between reported small numbers (about 1,000) of U.S. special operations forces and Central Intelligence Agency operatives. The purpose of these operations was to help Afghan forces opposed to the Taliban (led by an armed coalition known as the Northern Alliance) advance by directing U.S. air strikes on Taliban positions. In October 2001, about 1,300 Marines were deployed to pressure the Taliban in the southern province of Kandahar, but there were few pitched U.S.-Taliban battles.

Northern Alliance forces—despite promises that they would not enter Kabul—did so on November 12, 2001, to widespread popular approval.11 The Taliban subsequently lost the south and east to U.S.-supported Pashtun leaders, including Hamid Karzai. The Taliban regime ended on December 9, 2001, when Taliban head Mullah Omar and other leaders fled Kandahar, leaving it under tribal law. A provisional government was set up (see "Constitution and Political System," below) and on May 1, 2003, U.S. officials declared an end to "major combat."

From 2003 to mid-2006, U.S. and international troops (as part of the U.N.-mandated and NATO-led International Security Assistance Force, ISAF) trained nascent Afghan forces and fought relatively low levels of insurgent violence with focused combat operations mainly in the south and east.12 By late 2005, U.S. and partner commanders considered the insurgency mostly defeated and NATO assumed lead responsibility for security in all of Afghanistan during 2005-2006. Those optimistic assessments proved misplaced when violence increased in mid-2006. NATO-led operations during 2006-2008 cleared Taliban fighters from some areas but did not prevent subsequent reinfiltration by the Taliban, nor did preemptive combat and increased development work produce durable success. Taking into account the deterioration of the security situation, the United States and its partners decided to increase force levels.

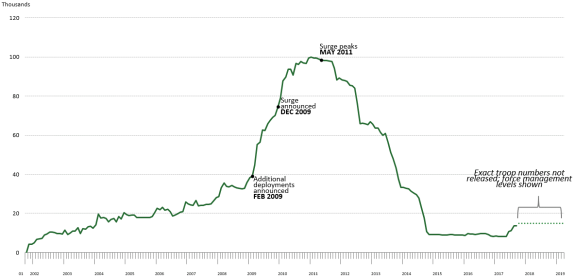

Obama Administration: "Surge" and Drawdown (2009-2014)

Upon taking office, the Obama Administration declared that the Afghanistan mission was a high priority, but that the U.S. level of effort there would eventually need to be reduced. The Administration convened a 60-day inter-agency "strategy review," chaired by former CIA analyst Bruce Riedel and co-chaired by then-Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan Richard Holbrooke and then-Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Michele Flournoy. In response to that review, President Barack Obama announced a "comprehensive" strategy on March 27, 2009, that would require the deployment of an additional 21,000 U.S. forces. 13

In June 2009, U.S. Army General Stanley McChrystal, who headed U.S. Special Operations forces from 2003 to 2008, became the top U.S. and NATO commander in Afghanistan. In August 2009, General McChrystal delivered a strategy assessment recommending that the goal of the U.S. military should be to protect the population rather than to search out and combat concentrations of Taliban fighters, warning of the potential for "mission failure" in the absence of a fully resourced, comprehensive counterinsurgency strategy. His assessment stated that about 44,000 additional U.S. combat troops would be needed to provide the greatest chance for success.14

The assessment set off debate within the Administration and launched another policy review. Some senior U.S. officials argued that adding many more U.S. forces could produce a potentially counterproductive sense of U.S. occupation.15 President Obama announced the following at West Point on December 1, 2009:

- 30,000 additional U.S. forces (a "surge") would be sent to "reverse the Taliban's momentum" and strengthen the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF); and

- beginning in July 2011, there would be a transition to Afghan security leadership and a corresponding drawdown of U.S. forces.16

The troop surge brought U.S. force levels to 100,000, with most of the additional forces deployed to the south. When the surge was announced, the Afghan Interior Ministry estimated that insurgents controlled 13 of the country's 356 districts and posed a "high-risk" to another 133.17 The Taliban had named "shadow governors" in 33 out of 34 of Afghanistan's provinces, although some were merely symbolic.18

Operations by U.S., NATO, and Afghan forces throughout 2010 and 2011 reduced areas under Taliban control substantially and the transition to Afghan security leadership began on schedule in July 2011. In concert with the transition, and asserting that the killing of Osama bin Laden represented a key accomplishment of the core U.S. mission, President Obama announced on June 22, 2011 that:

- U.S. force levels would fall to 90,000 (from 100,000) by the end of 2011.

- U.S. force levels would drop to 68,000 by September 2012.

In his February 2013 State of the Union message, President Obama announced that the U.S. force level would drop to 34,000 by February 2014, which subsequently occurred. Most partner countries drew down their forces at roughly the same rate and proportion as the U.S. drawdown, despite public pressure in some European countries to more rapidly reduce or end military involvement in Afghanistan. During 2010-2012, the Netherlands, Canada, and France ended their combat missions, but they continued to train the ANDSF until the end of 2014.

On June 18, 2013, NATO and Afghanistan announced that Afghan forces were now taking the lead on security throughout all of Afghanistan. As international forces were reduced in 2014, Afghan and international officials expressed uncertainty about U.S. and partner plans for the post-2014 period.19 On May 27, 2014, President Obama clarified Administration plans by announcing the size of the post-2014 U.S. force and plan for a U.S. military exit according to the following timeline:

- The U.S. military contingent in Afghanistan would be 9,800 in 2015, deployed in various parts of Afghanistan, consisting mostly of trainers in the NATO-led "Resolute Support Mission" (RSM).

- The U.S. force would decline to about 5,000 by the end of 2016 and consolidate in Kabul and at Bagram Airfield.

- After 2016, the U.S. military presence would be consistent with normal security relations with Afghanistan (about 1,000 military personnel) under U.S. Embassy authority (without a separate military chain of command in country). Their mission would be to protect U.S. installations, process Foreign Military Sales (FMS) of weaponry to Afghanistan, and train the Afghans on that weaponry.20

During 2014, the United States and its partners prepared for the end of the ISAF mission. U.S. airpower in country was reduced, ISAF turned over the vast majority of about 800 bases to the ANDSF, and the provincial reconstruction teams (PRTs) were turned over to Afghan institutions.21

Bilateral Accords: Strategic Partnership Agreement (SPA) and Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA)

On May 1, 2012, President Obama and then-President Hamid Karzai signed an Enduring Strategic Partnership Agreement (SPA) between Afghanistan and the United States.22 The signing followed a long negotiation that focused on resolving Afghan insistence on control over detention centers and a halt to or control over nighttime raids on insurgents by U.S. forces. In addition to provisions designating Afghanistan as a Major Non-NATO Ally, the agreement committed the two countries to negotiating a Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) that would detail the terms of U.S. engagement in Afghanistan.23 The BSA was approved by a loya jirga (consultative assembly) called by then-President Karzai in November 2013, though he then refused to sign; the agreement was eventually signed by President Ashraf Ghani as one of his first acts after taking office in September 2014.24 The BSA was considered as an executive agreement was not submitted for congressional approval.

The BSA governs the United States' post-2014 presence in Afghanistan through the end of 2024 "and beyond" unless terminated by mutual written agreement or by either country with two years' written notice. The agreement does not set (or otherwise refer to) U.S. and partner force levels, but lays out the parameters and goals of the U.S. military mission and provides for U.S. access to Afghan bases. The BSA also stipulates that "the United States shall have the exclusive right to exercise jurisdiction over such [U.S.] persons in respect of any criminal or civil offenses committed in the territory of Afghanistan." The BSA does not commit the United States to defend Afghanistan from attack from another country, but states that "the United States shall regard with grave concern any external aggression or threat" thereof. Some Afghan figures, including Karzai (who remains active in Afghan politics), advocate revising the BSA, but such efforts do not appear to have the support of the current Afghan government.25

Resolute Support Mission (2015-Present)

The NATO-led ISAF ended at the close of 2014, and was replaced by Resolute Support Mission (RSM) on January 1, 2015. The legal framework for NATO's presence is based on a Status of Forces Agreement signed between the Afghan government and NATO in September 2014 and ratified by the Afghan parliament in November 2014.26 That agreement defines RSM as a "non-combat training, advising and assistance mission," though combat operations by some U.S. forces, in support of Afghan forces, continue.

|

NATO Contribution The current train, advise, and assist mission in Afghanistan, Resolute Support Mission (RSM), is led by NATO, and NATO partners have been heavily engaged in Afghanistan since 2001. At its height in 2012, the number of NATO and non-NATO partner forces reached 130,000, around 100,000 of whom were American. As of June 2019, RSM is made up of around 17,100 troops from 39 countries, of whom 8,475 are American. This represents an increase of about 3,000 troops from NATO and other partner countries. At the NATO summit in July 2018, NATO leaders extended their financial commitment to Afghan forces to 2024 (previously 2020), a commitment NATO reaffirmed in June 2019.27 |

Alterations to the Drawdown Schedule and Rules of Engagement

Concerns about Taliban gains after 2015 led to several changes to the U.S. mission in the final two years of the Obama Administration.

- On March 24, 2015, in concert with the visit to Washington, DC of President Ghani and Chief Executive Officer Abdullah Abdullah, President Obama announced that U.S. forces would remain at a level of about 9,800 for all of 2015, rather than being reduced to 5,500 by the end of the year, as originally announced.

- In January 2016, the Obama Administration authorized U.S. commanders in Afghanistan to attack the local Islamic State affiliate, Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP, more below) forces.

- In June 2016, President Obama authorized U.S. forces to conduct preemptive combat. According to then-Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter on July 12, 2016, U.S. forces were enabled to "anticipate battlefield dynamics and ... deploy and employ their forces together [with the ANDSF] in a way that stops a situation from deteriorating [or] interrupts an enemy in the early stages of planning and formulating an attack."

- On July 6, 2016, President Obama again adjusted planned U.S. force levels, stating that the level would drop to 8,400 at the end of 2016, rather than to the 5,500 that was previously announced.

- The communique of the NATO summit in Warsaw, Poland (July 8-9, 2016), announced that other NATO countries would continue to support RSM beyond 2016, both with force contributions and donations to the ANDSF (the latter until 2020).28 No force or budget levels were specified in the declaration.

Developments during the Trump Administration

In a national address on August 21, 2017, President Donald Trump announced a "new strategy" for Afghanistan and South Asia. Despite expectations that he would describe specific elements of his new strategy, particularly the prospects for additional troops, President Trump declared "we will not talk about numbers of troops or our plans for further military activities."29 Some policymakers characterized the strategy as "short on details" and serving "only to perpetuate a dangerous status quo."30 Others welcomed the decision, contrasting it favorably with proposed alternatives such as a full withdrawal of U.S. forces (which President Trump conceded was his "original instinct") or heavy reliance on contractors.31

Beyond additional troops, the strategy also gave broader authority for U.S. forces to operate independently of Afghan forces and "attack the enemy across the breadth and depth of the battle space," expanding the list of targets to include those related to "revenue streams, support infrastructure, training bases, [and] infiltration lanes."32 This was exercised in a series of operations, beginning in fall 2017, against Taliban drug labs. These operations, often highlighted by U.S. officials, sought to degrade what is widely viewed as one of the Taliban's most important sources of revenue, namely the cultivation, production, and trafficking of narcotics.33 Some analysts have questioned the impact of these strikes, which ended in late 2018.34

|

U.S. Force Levels and Recent Congressional Action Since 2001, U.S. military personnel levels in Afghanistan have evolved, due to a combination of changes in U.S. strategy, operational demands, and the Afghanistan security situation. Figure 2 illustrates the levels of deployed uniformed U.S. military personnel in Afghanistan between October 2001 and present. The size of the NATO-led military presence in Afghanistan peaked at around 130,000 international troops, of which nearly 100,000 were American, between 2010 and 2012. Scheduled drawdowns under the Obama Administration (many of which were delayed or otherwise altered) brought the number of U.S. forces to about 11,000 by January 2017.35 At a February 2017 Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, then-U.S. commander General John Nicholson indicated that the United States had a "shortfall of a few thousand" troops that, if filled, could help break the "stalemate."36 In June 2017, President Trump delegated to then-Secretary of Defense Mattis the authority to set force levels, reportedly limited to around 3,500 additional troops; Secretary Mattis signed orders to deploy those additional personnel in September 2017.37 With the increase to in-country U.S. forces, most observers and analysts put the total number of U.S. troops in the country at around 14,000, though U.S. commanders and media reports sometimes cite a figure of 15,000. Official troop level data has been unavailable since the Trump Administration stopped publishing information about troop deployments in Afghanistan and other conflict zones starting with the December 30, 2017 quarterly report from the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC).38 Some Members of Congress have since engaged with administration officials at hearings, written letters to administration officials, and introduced legislative measures that would require the Secretary of Defense to rescind the decision to withhold information, but DMDC quarterly reports, as well as other U.S. government releases, still lack deployment data for Afghanistan (as well as Syria and Iraq).39 Some reports from late 2018 and early 2019 indicated that President Trump may be contemplating ordering the withdrawal of some U.S. forces from Afghanistan.40 Still, U.S. officials maintain that no policy decision has been made to reduce U.S. force levels. In the 116th Congress, legislation has been introduced both supporting and opposing such moves:

|

|

|

Source: Department of Defense "Boots on the Ground" monthly reports to Congress, media reports. Notes: Reported DOD figures through October 2017 include all active and reserve component personnel physically located in Afghanistan as of the first calendar day of each month. |

Security Dynamics: The Taliban and Other Armed Groups

Decades of instability, civil war, and weak central government control have contributed to the existence of a complex web of militant groups in Afghanistan. While the Taliban are by far the largest and best-organized, they operate alongside (and sometimes in competition with) other armed groups, including regional affiliates of both the Islamic State and Al Qaeda.

Taliban Insurgency

While U.S. commanders have asserted that the ANDSF performs well despite taking heavy casualties, Taliban forces have retained, and by some measures are increasing, their ability to contest and hold territory and to launch high-profile attacks. U.S. officials often have emphasized the Taliban's failure to capture a provincial capital since their week-long seizure of Kunduz city in northern Afghanistan in September 2015, but Taliban militants briefly overran two capitals, Farah and Ghazni, in May and August 2018, respectively. Then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis described the Taliban assault on Ghazni, which left hundreds dead, as a failure for the Taliban, saying "every time they take [a city] ... they're unable to hold it."42

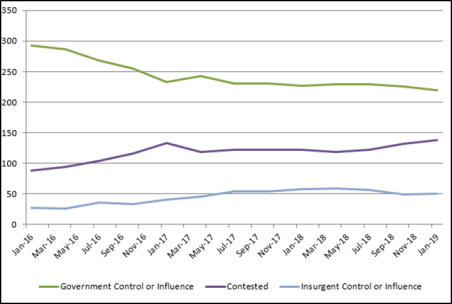

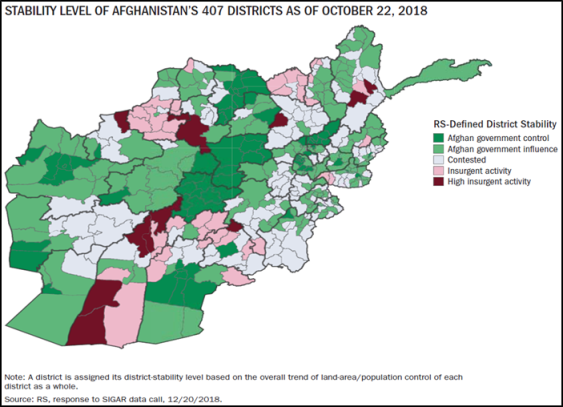

Since at least early 2017, U.S. military officials have stated that the conflict is "largely stalemated."43 Arguably complicating that assessment, the extent of territory controlled or contested by the Taliban has generally grown since 2016 by most measures (see Figure 3). In November 2015, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) began publishing in its quarterly reports a district-level assessment of stability in Afghanistan produced by the U.S. military. This assessment estimated the extent of Taliban control and influence in terms of both territory and population, and was typically accompanied by charts portraying those trends over time as well as a color-coded map of control/influence by district (see Figure 4). That data showed a gradual increase in the share of Afghan districts controlled, influenced, or contested by insurgents (46% as of October 2018, the last month such data was evidently collected, compared to 28% in November 2015). According to SIGAR's April 30, 2019 quarterly report, the U.S. military is "no longer producing its district-level stability assessments of Afghan government and insurgent control and influence." SIGAR reports that it was told by the U.S. military that the assessment is no longer being produced because it "was of limited decision-making value to the [U.S.] Commander."44

|

|

Source: SIGAR, January 30, 2019, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress. |

The Taliban have demonstrated considerable, and some observers would argue growing, tactical capabilities.45 Due to the high levels of casualties inflicted by the Taliban, the Trump Administration has reportedly urged Afghan forces to pull out of some isolated outposts and rural areas.46 Reports indicate that ANDSF fatalities have averaged 30-40 a day in recent months, and President Ghani confirmed in November 2018 that Afghan forces had suffered more than 28,000 fatalities since 2015.47 So-called "green on blue" attacks (insider attacks on U.S. and coalition forces by Afghan nationals) are a sporadic, but persistent, problem—several U.S. servicemen died in such attacks in 2018, as did 85 Afghan soldiers.48 In October 2018, General Miller was present at an attack inside the Kandahar governor's compound by a Taliban infiltrator who killed a number of provincial officials, including the powerful police chief Abdul Raziq; Miller was unhurt but another U.S. general was wounded.49

|

Taliban Leaders Mullah Mohammad Omar, 1994-2013 (died in hiding of natural causes in April 2013; death confirmed by the Taliban in July 2015) Mullah Akhtar Mansour, 2015-2016 (killed in a May 2016 U.S. drone strike in Pakistan) Haibatullah Akhundzada, 2016-present |

The May 2016 death of then-Taliban head Mullah Mansour in a U.S. drone strike demonstrated Taliban vulnerabilities to U.S. intelligence and combat capabilities, although his death did not appear to have a measurable effect on Taliban effectiveness; it is unclear to what extent current leader Haibatullah Akhundzada exercises effective control over the group and how he is viewed within its ranks.50

Haqqani Network

Founded by Jalaluddin Haqqani, a mujahideen commander and U.S. ally during the war against the Soviet occupation, the Haqqani Network is a semiautonomous wing of the Afghan Taliban. As such, it has been cited by U.S. officials as a potent threat to U.S. and allied forces and interests, as well as a "critical enabler of Al Qaeda."51

Jalaluddin Haqqani served as a minister in the Taliban regime, and after 2001 reestablished a presence in the Pakistani tribal territory of North Waziristan. By 2006, he was credited as "the architect of the Taliban's current attacks on U.S. and coalition forces in Afghanistan."52 Within a few years, Jalaluddin's son Sirajuddin took over the group's operations, becoming increasingly influential in setting overall insurgency strategy, and was selected as deputy leader of the Taliban in 2015.53 The Taliban announced the death of Jalaluddin, who reportedly had been ill for years, in September 2018.

The Haqqani network is blamed for a number of major attacks, including a devastating May 2017 bombing in Kabul's diplomatic district that left over 150 dead and sparked violent protests against the government. The Haqqani network has historically targeted Indian interests in Afghanistan, reinforcing perceptions by some observers and officials that the group often acts as a tool of Pakistani foreign policy.54 In September 2011, then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Michael Mullen testified in front of the Senate Armed Services Committee that the Haqqani network acts "as a veritable arm" of Pakistan's main intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI). Additionally, it reportedly holds captive two professors (Timothy Weeks, an Australian, and American citizen Kevin King, who is reportedly seriously ill)55 kidnapped from the American University of Afghanistan in August 2016; and a journalist (Paul Overby) seized in 2014 after crossing into Afghanistan to try to interview the Haqqani leadership.56

The faction's participation in a political settlement potentially could be complicated by its designation as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) under the Immigration and Naturalization Act. That designation was made on September 9, 2012, after the 112th Congress enacted S. 1959 (Haqqani Network Terrorist Designation Act of 2012, P.L. 112-168), requiring an Administration report on whether the group met the criteria for FTO designation.

Islamic State-Khorasan Province

Beyond the Taliban, a significant share of U.S. operations are aimed at the local Islamic State affiliate, known as Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP, also known as ISIS-K), although experts debate the degree of threat the group poses.57

ISKP (also referred to as ISIS-K) has been active in Afghanistan since mid-2014. ISKP was named as an FTO by the State Department on January 14, 2016. The group's presence in Afghanistan crystallized from several small Afghan Taliban and other militant factions that announced affiliation with the organization in 2013; ISKP presence grew further as additional Taliban factions defected to the group and captured some small areas primarily in eastern Afghanistan. ISKP has reportedly received financial assistance from the core organization formerly located in the self-declared "caliphate" in parts of Iraq and Syria.58 Estimates of the number of ISKP fighters generally range from 1,000 to 3,000.

To address the ISKP threat, U.S. commanders have had authorization since December 2015 to combat ISKP fighters by virtue of their affiliation with the Islamic State, whether or not these fighters pose an immediate threat to U.S. and allied forces. U.S. operations have repeatedly targeted the group's leaders, with three killed in less than a year: Hafiz Saeed Khan died in a July 2016 U.S. airstrike and successors Abdul Hasib and Abu Sayed were killed in April and July 2017, respectively. ISKP has survived these leadership losses and appears to be a growing factor in U.S. and Afghan strategic planning. ISKP was the target of the much publicized April 2017 use of a GBU-43 (also known as a Massive Ordnance Air Blast, or MOAB), reportedly the first such use of the weapon in combat. A number of U.S. military, as well as CIA personnel, have been killed in anti-ISKP operations.59

ISKP and Taliban forces have sometimes fought over control of territory or because of political or other differences.60 In April 2018, a U.S. air strike killed the ISKP leader (himself a former Taliban commander) in northern Afghanistan, Qari Hekmatullah. NATO described neighboring Jowzjan province as "the main conduit for external support and foreign fighters from Central Asian states into Afghanistan."61 ISKP also has claimed responsibility for a number of large-scale attacks, many targeting Afghanistan's Shia minority. ISKP is also reported to have ambitions beyond Afghanistan; an unnamed U.S. intelligence officials was quoted in June 2019 as saying that, absent sustained counterterrorism pressure, "Afghanistan's IS affiliate will be able to carry out a large-scale attack in the U.S. or Europe within the next year."62

Al Qaeda63

While the Al Qaeda attacks of September 11 precipitated U.S. military operations in Afghanistan, the group has been a relatively minor player on the Afghan battlefield since. However, the relationship between Al Qaeda and the Taliban has important implications for U.S.-Taliban negotiations and a potential settlement.

From 2001 until 2015, Al Qaeda was considered by U.S. officials to have only a minimal presence (fewer than 100 members) within Afghanistan, operating mostly as a facilitator for insurgent groups and mainly in the northeast. However, in late 2015 U.S. Special Operations forces and their ANDSF partners discovered and destroyed a large Al Qaeda training camp in Kandahar Province—a discovery suggesting a stronger Al Qaeda presence in Afghanistan than had been generally understood. In April 2016, U.S. commanders publicly raised their estimates of Al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan to 100-300, and said that relations between Al Qaeda and the Taliban had become increasingly close; Afghan estimates are generally higher.64 The United Nations reports that Al Qaeda, while degraded in Afghanistan and facing competition from ISKP, "remains a longer-term threat."65

U.S. efforts to find remaining senior Al Qaeda leaders reportedly focus on bin Laden's successor Ayman al-Zawahiri, who is presumed to be on the Pakistani side of the border. While most successful U.S. strikes on high-ranking Al Qaeda operatives have taken place in Pakistan, several have been killed in Afghanistan in recent years, including operative Abu Bara Al Kuwaiti (October 2014, in Nangarhar Province); and Al Qaeda's commander for northeastern Afghanistan, Faruq Qahtani (October 2016).

Al Qaeda is allied with the Taliban; bin Laden pledged allegiance to Taliban founder Mullah Omar and bin Laden successor Ayman al Zawahiri has done the same with Omar's two successors, in turn.66 According to a January 2019 U.N. report, Al Qaeda "continues to see Afghanistan as a safe haven for its leadership, based on its long-standing, strong ties with the Taliban."67 Some observers have noted operational cooperation between Al Qaeda and the Taliban, particularly in the east, in recent years.68 The AQ-Taliban alliance may complicate U.S. demands that the Taliban foreswear support for terrorism as part of a potential U.S. troop withdrawal deal; some analysts have recommended that "as part of any final deal, the Taliban should be required to state, in no uncertain terms, its official position" on Al Qaeda.69

Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) is an affiliate of Al Qaeda based in and including members from various terrorist groups in South and Central Asia. Zawahiri announced the group's formation in 2014. In June 2016, the State Department designated the group as an FTO and its leader, Asim Umar, as a specially designated global terrorist. The large terrorist training camp found in Kandahar in 2015 was attributed by U.S. military officials to AQIS.

Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF)

The primary objective of the post-2015 NATO-led Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan is training, advising, and assisting the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) in their struggle against the Taliban and other armed groups.

Funding the ANDSF costs an estimated $6 billion per year, of which the U.S. has provided about $4.5 billion in recent years. At the NATO summit in Warsaw in July 2016, U.S. partners pledged $1 billion annually for the ANDSF during 2017-2020. U.S. officials assess that Afghanistan is contributing its pledged funds—$500 million (as calculated in Afghan currency)—despite budgetary difficulties. At the 2012 NATO summit in Chicago, Afghanistan agreed to assume full financial responsibility for the ANDSF by 2024, though current security dynamics and economic trends make that unlikely.

The Department of Defense (DOD), SIGAR, and others have reported on deficiencies of the ANDSF, citing challenges such as absenteeism, high casualties, illiteracy, inconsistent leadership, and a deficit of logistical capabilities, such as airlift, medical evacuation, resupply, and other associated functions.70 ANDSF units and personnel also have been associated with credible allegations of child sexual abuse and other potential human rights abuses.71

A number of metrics related to ANDSF performance have been classified in recent years. In October 2017, SIGAR reported that "in a significant development," U.S. officials "classified or otherwise restricted information" SIGAR had previously reported, such as casualty rates, personnel strength, and attrition within the ANDSF. U.S. officials have cited a request from the Afghan government as justification for the decision.72 Personnel figures and attrition rates for some ANDSF components have since been made available in SIGAR reports.

Other public information about ANDSF capabilities is also generally not encouraging. Media reports indicate that ANDSF fatalities have averaged 30-40 a day in recent months, and President Ghani stated in January 2019 that more than 45,000 security personnel had paid "the ultimate sacrifice" since he took office in September 2014.73 Partly in response to those casualty rates, Afghan forces are reportedly shuttering small checkpoints (where the majority of successful Taliban attacks take place) in favor of larger bases in more secure territory.74 U.S. advisors have long advocated for such moves, although critics claim that these steps effectively cede swaths of the country to the Taliban.75

The major components of the ANDSF are:

Afghan National Army (ANA). The Afghan National Army has been built from scratch since 2002—it is not a direct continuation of the national army that existed from the nineteenth century until the Taliban era. That army disintegrated during the 1992-1996 mujahideen civil war and the 1996-2001 Taliban period. Of its authorized size of 195,000, the ANA (all components) had about 190,000 personnel as of January 2019. Its special operations component, known as the Afghan Special Security Forces (ASSF) numbers nearly 21,000. The ASSF is trained by U.S. Special Operations Forces, and U.S. commanders say it might be one of the most proficient special forces in the region.76 Afghan special forces are utilized extensively to reverse Taliban gains, and their efforts reportedly have reportedly made up 70% to 80% of the fighting in recent years.77 A December 2018 DOD report assessed that ASSF "misuse increased to unsustainable levels" in late 2018, saying that the ASSF's deployment for such missions as static defense operations (in lieu of the conventional ANA) undermines anti-Taliban efforts.78

Afghan Air Force (AAF). Afghanistan's Air Force is emerging as a key component of the ANDSF's efforts to combat the insurgency. The AAF has been mostly a support force but, since 2014, has increased its bombing operations in support of coalition ground forces, mainly using the Brazil-made A-29 Super Tucano. The force is a carryover from the Afghan Air Force that existed prior to the Soviet invasion, though its equipment was virtually eliminated in the 2001-2002 U.S. combat against the Taliban regime. Since FY2010, the United States has appropriated about $8.4 billion for the AAF, including $1.7 billion in FY2019. Still, equipment, maintenance, logistical difficulties, and defections continue to plague the Afghan Air Force, which has about 104 aircraft including four C-130 transport planes and 46 Mi-17 (Russian-made) helicopters.79 DOD plans to purchase up to 159 UH-160 Black Hawk helicopters for the AAF have been complicated by shortages of Afghan engineers and pilots.80

Afghan National Police (ANP). U.S. and Afghan officials believe that a credible and capable national police force is critical to combating the insurgency. DOD reports on Afghanistan assess that "significant strides have been made in professionalizing the ANP." However, many outside assessments of the ANP are negative, asserting that there is rampant corruption to the point where citizens mistrust and fear the ANP.81 According to SIGAR, as of 2019, the U.S. has obligated $21.4 billion (in Afghanistan Security Forces Funds, ASFF) to support the ANP since FY2005. The force is largely supported by the U.N.-managed Law and Order Trust Fund for Afghanistan (LOTFA).

The U.S. police training effort was first led by State Department/Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL), but DOD took over the lead role in April 2005. Police training has been highlighted by SIGAR and others as a potentially problematic area where greater interagency cooperation is needed.82 The target size of the ANP, including all forces under the ANP umbrella (except the Afghan Local Police, which are now under the command of the Ministry of the Interior), is 124,000; as of December 2018, it has 116,000 personnel. According to a December 2018 DOD assessment, women reportedly have a higher presence in the ANP than they do in the ANA.

Afghan Local Police (ALP). In 2008, the failure of several police training efforts led the Afghan government, with U.S. assistance, to support local forces in protecting their communities, despite some reluctance to create local militias, which previously had been responsible for human rights abuses in Afghanistan. The ALP concept grew out of earlier programs to organize and arm local civilians to provide security in their home districts; fighters are generally selected by local elders. The current number of ALP members (known as "guardians") is around 28,000.

The ALP have the authority to detain criminals or insurgents temporarily, and transfer them to the ANP or ANA, but have been cited by Human Rights Watch and other human rights groups, as well as by DOD investigations, for killings, rapes, arbitrary detentions, land grabs, and sexual abuse of young boys.83 Others criticize the ALP as incompatible with the goal of creating nationalized defense and security forces and characterize ALP forces as unaccountable militias serving the interests of local strongmen.84 There have been discussions around incorporating ALP elements into the ANDSF. The ALP are funded by the United States at approximately $60 million a year (ASFF funds disbursed by CSTC-A).

Regional Dimension

Regional developments and relationships have long influenced events inside Afghanistan. The Trump Administration has linked U.S. policy in Afghanistan to broader regional dynamics, particularly as they relate to South Asia. Key states include Afghanistan's most important neighbors, Pakistan and Iran; the larger regional players India, Russia, and China; and the politically influential Gulf States.

Pakistan

The neighbor that is considered most crucial to Afghanistan's security is Pakistan, which has played an active and, by many accounts, negative role in Afghan affairs for decades. Experts and officials debate the extent of Pakistan's commitment to Afghan stability in light of its attempts to exert control over events in Afghanistan through ties to insurgent groups. DOD reports on Afghanistan's stability repeatedly have identified Afghan militant safe havens in Pakistan as a key threat to Afghan stability.

|

Afghanistan-Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement U.S. efforts to persuade Pakistan to forge a "transit trade" agreement with Afghanistan bore success with the signature of a trade agreement between the two on July 18, 2010, though implementation has been uneven. The agreement allows for easier exportation via Pakistan of Afghan products, which are mostly agricultural products that depend on rapid transit and are key to Afghanistan's economy. Under the agreement, Afghan goods have access to Pakistani markets and ports, but cannot reach India directly. Afghan efforts to secure Pakistani approval for land transit of Afghan goods to India have been unsuccessful, a frequent irritant in the countries' relations. Total annual trade between the two is around $2 billion, but Pakistan is much more important for Afghanistan than the reverse. Afghanistan is the fifth-largest destination for Pakistani exports, comprising about 6% of the total, while nearly 40% of all Afghan exports go to Pakistan. |

Afghanistan-Pakistan Relations. Many Afghans approved of Pakistan's backing the mujahideen that forced the Soviet withdrawal in 1988-1989, but later came to resent Pakistan as one of three countries to formally recognize the Taliban as the legitimate government. (Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are the others.) Relations improved after Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf left office in 2008 but remain troubled as Afghan leaders continue to accuse Pakistan of supporting the Taliban and meddling in Afghan affairs. On several occasions, President Ghani has accused Pakistan of waging an "undeclared war" on Afghanistan.85

Some analysts argue that Pakistan sees Afghanistan as potentially providing it with "strategic depth" against India.86 Pakistan has long asserted that India uses its diplomatic facilities in Afghanistan to recruit anti-Pakistan insurgents, and that India is using its aid programs to build anti-Pakistan influence there. Long-standing Pakistani concerns over Indian activities in Afghanistan are being exacerbated by President Trump's pledge to further develop the United States' strategic partnership with India as part of the new U.S. approach to Afghanistan and South Asia.87

About 2 million Afghan refugees have returned from Pakistan since the Taliban fell, but 1.4 million registered refugees remain in Pakistan, according to the United Nations, along with perhaps as many as 1 million unregistered refugees.88 Many of these refugees are Pashtuns, the ethnic group that makes up about 40% of Afghanistan's 35 million people and 15% of Pakistan's 215 million; Pashtuns thus represent a plurality in Afghanistan but are a relatively small minority among many others in Pakistan, though Pakistan's Pashtun population is considerably larger than Afghanistan's. Pakistan condemns as interference statements by President Ghani (who is Pashtun) and other Afghan leaders about an ongoing protest campaign by Pakistani Pashtuns for greater civil and political rights.89

Afghanistan-Pakistan relations are also complicated by the two countries' long-running dispute over their shared 1,600-mile border, the "Durand Line." Pakistan, the United Nations, and others recognize the Durand Line as an international boundary, but Afghanistan does not. Afghanistan contends that the Durand Line, a border agreement reached between the British Empire and Afghanistan in 1893, was drawn unfairly to separate Pashtun tribes and should be renegotiated. Tensions between the two neighbors have erupted several times in recent years, most recently in 2017, when clashes at the Chaman border crossing (which sits on the Durand Line) reportedly led to civilian and military casualties on both sides. Previous agreements led to efforts to deconflict the situation, but such bilateral mechanisms evidently have proven insufficient.90 Pakistan claims to have established nearly 1,000 border posts along the Durand Line, nearly five times as many as operated by Afghanistan.91

Pakistan and U.S. Policy in Afghanistan. For several years after the September 11, 2001 attacks, Pakistani cooperation with the United States against Al Qaeda was, arguably, relatively effective. Pakistan arrested more than 700 Al Qaeda figures after the September 11 attacks and allowed U.S. access to Pakistani airspace, some ports, and some airfields for the major combat phase of OEF.92 However, traditional support for the Taliban by elements of the Pakistani government and security establishment caused strains with the U.S. that were compounded by the May 1, 2011, U.S. raid that killed Osama bin Laden in Pakistan. Relations worsened further after a November 26, 2011, incident in which a U.S. airstrike killed 24 Pakistani soldiers, and Pakistan responded by closing border crossings, suspending participation in the border coordination centers, and boycotting the December 2011 Bonn Conference. Relations improved from the 2011 low in subsequent years but have remained tense.

President Trump, in announcing a new Afghanistan strategy in August 2017, declared that "we can no longer be silent about Pakistan's safe haven for terrorist organizations," and that while "in the past, Pakistan has been a valued partner ... it is time for Pakistan to demonstrate its commitment to civilization, order, and to peace."93 Despite that praise for Pakistan as a "valued partner," and U.S. other officials hailing successful Pakistani efforts to secure the release of several Americans held by the Haqqanis in Afghanistan in October 2017, the Trump Administration announced plans in January 2018 to suspend security assistance to Pakistan. That decision has impacted hundreds of millions of dollars of aid.94

Beyond the issue of aid (which had been withheld in the past, to little apparent effect), observers have speculated about such measures as reexamining Pakistan's status as a major non-NATO ally, increasing U.S. drone strikes on targets within Pakistan, and imposing sanctions on Pakistani officials.95 Pakistani officials and others warn that such measures could be counterproductive, highlighting the potential geopolitical costs of increasing pressure on Pakistan, especially as they relate to U.S. counterterrorism efforts and Pakistan's critical role in facilitating U.S. ground and air lines of communication to landlocked Afghanistan.96

Iran

Iran has long sought to exert its historic influence over western Afghanistan and to protect Afghanistan's Shia minority. Tensions between Iran and the U.S., whose presence in Afghanistan has long concerned Tehran, may be driving Iran's reported attempts to support the Taliban, its erstwhile foe.

Iran historically opposed the Taliban, which Iran saw as a threat to its interests in Afghanistan, especially after Taliban forces captured the western city of Herat in September 1995, and Iran supported the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance with fuel, funds, and ammunition.97 In September 1998, Iranian and Taliban forces nearly came into direct conflict when Taliban forces killed several Iranian diplomats in the course of the Taliban's offensive in northern Afghanistan. Iran massed forces at the border and threatened military action, but the crisis cooled without a major clash. Iran offered search and rescue assistance in Afghanistan during the U.S.-led war to topple the Taliban, and it also allowed U.S. humanitarian aid to the Afghan people to transit Iran. Iran helped broker Afghanistan's first post-Taliban government, in cooperation with the United States, at the December 2001 Bonn Conference.

At the same time, Iran has had diplomatic contacts with the Taliban since at least 2012, when Iran allowed a Taliban office to open in Iran, and high-level Taliban figures have visited Iran.98 While some analysts see the contacts as Iranian support of the insurgency, others see them as an effort to exert some influence over reconciliation efforts.99 Iran likely seeks to ensure that U.S. forces cannot use Afghanistan as a base from which to pressure or attack Iran. Since at least early 2017, however, U.S. officials have reported more active Iranian backing for Taliban elements, particularly in western Afghanistan. In November 2018, Trump Administration officials displayed a number of Iranian-origin rockets that they alleged had been provided to the Taliban.100

Iran's support of Taliban fighters, many of whom are Pashtun, is in contrast with Iran's traditional support of non-Pashtun Persian-speaking and Shia factions in Afghanistan. For example, Iran has funded pro-Iranian armed groups in the west and has supported Hazara Shias in Kabul and in Hazara-inhabited central Afghanistan, in part by providing scholarships and funding for technical institutes as well as mosques. There are consistent allegations that Iran has funded Afghan provincial council and parliamentary candidates in areas dominated by the Persian-speaking and Shia minorities.101

|

Afghan Fighters in Syria: Iran's Fatemiyoun Division The Fatemiyoun Division (Liwa Fatemiyoun) is an Iranian-financed and -commanded military unit operating in Syria that is made up of Shia Afghans. The organization, formed in 2014, has its roots in various Iranian-supported groups that were active in fighting both against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan in the 1980s (the "Tehran Eight") and alongside Iranian forces in the Iran-Iraq War. By late 2013, reports of Shia Afghans fighting alongside Iranian and Bashar al Asad government-aligned forces had emerged out of Syria.102 The likely motivations behind Afghan participation in the Syrian war are numerous, ranging from religious allegiances to economic and legal incentives to outright coercion by Iranian authorities. In 2018, the Washington Post reported, "Even more than religion, these Afghan recruits seem mainly driven by necessity, reenlisting again and again to take home another few hundred dollars in military pay — even as they risk injury or death in front-line battles where few Iranian troops are sent."103 Human Rights Watch has documented alleged instances of Iranian recruitment of child soldiers from Afghan refugees.104 The role of Afghans in the Iranian effort to support the Asad government has been, by some measures, significant. The size of the Fatemiyoun Division is generally estimated at between 10,000 and 15,000, with "4,000-8,000 fighters deployed at any given time."105 By some reports, Afghan fighters are used as "cannon fodder," with many knowing little about the dynamics of the war in which they fight given their cultural and linguistic isolation.106 With the Asad government recapturing most areas of Syria formerly under opposition control, the future of Fatemiyoun fighters is an open question. According to one February 2018 report, "there are indications that Fatemiyoun recruitment has stopped and some fighters are being returned to Iran."107 The most serious concern among U.S. and Afghan policymakers is that Iran could potentially use Fatemiyoun fighters in Afghanistan itself, perhaps as part of Iran's regional rivalry with Saudi Arabia, which has also supported various groups in Afghanistan.108 However, as noted by one analyst, "the Fatemiyoun Division's disproportionately high casualties and reliance on Iranian midlevel commanders reflect its limited usefulness for Tehran."109 The Fatemiyoun could also redouble to Iran's disadvantage in Afghanistan, where the group has proven politically controversial. Mohammad Mohaqeq, the deputy chief executive of Afghanistan and the highest ranking Hazara official in government, drew criticism from President Ghani and others after Mohaqeq praised the role of Iran and its regional proxies in the Syrian conflict in November 2017.110 |

Even as it funds anti-government groups as a means of pressuring the United States, Iran has built ties to the Afghan government. President Ghani generally has endorsed his predecessor's approach on Iran; Karzai called Iran a "friend" of Afghanistan and said that Afghanistan must not become an arena for disputes between the United States and Iran.111 At other times, Afghanistan and Iran have had disputes over Iran's efforts to expel Afghan refugees. There are approximately 1 million registered Afghan refugees in Iran, with as many as 2 million more unregistered.112 Iran's ties to the Shia community in Afghanistan have facilitated its recruitment of Afghan Shias to fight on behalf of the Asad regime in Syria, though there is some evidence that Shia Afghan refugees have been coerced into joining the war effort (see textbox).

India

India's past involvement in Afghanistan reflects its long-standing concerns about potential Pakistani influence and Islamic extremism emanating from Afghanistan, though its current role is focused on development. India also views Afghanistan as a trade and transit gateway to Central Asia, but Pakistan blocks a direct route, so India has sought to develop Iran's Chabahar Port.

India supported the Northern Alliance against the Taliban in the mid-1990s and retains ties to Alliance figures. India saw the Afghan Taliban's hosting of Al Qaeda during 1996-2001 as a major threat because of Al Qaeda's association with radical Islamic organizations in Pakistan that seek to end India's control of part of the disputed territories of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.113 Some of these groups have committed major acts of terrorism in India, including the attacks in Mumbai in November 2008 and in July 2011.

Afghanistan has sought to strengthen its ties to India—in large part to access India's large and rapidly growing economy—but has sought to do so without causing a backlash from Pakistan. In October 2011, Afghanistan and India signed a "Strategic Partnership." The pact affirmed Pakistani fears by giving India, for the first time, a formal role in Afghan security; it provided for India to train ANDSF personnel, of whom thousands have been trained since 2011.114 However, India has resisted playing a greater role in Afghan security, probably to avoid becoming ever more directly involved in the conflict in Afghanistan or inviting Pakistani reprisals.

India's involvement in Afghanistan is dominated by development issues. India is the fifth-largest single country donor to Afghan reconstruction, funding projects worth over $3 billion.115 Indian officials assert that their projects are focused on civilian, not military, development and are in line with the development priorities set by the Afghan government.116 As part of the new U.S. strategy for Afghanistan, President Trump called in August 2017 for India to "help us more with Afghanistan, especially in the area of economic assistance and development," though he also derided Indian aid to Afghanistan in January 2019.117

- Prime Minister Modi visited Afghanistan in December 2015 and June 2016 to inaugurate major India-sponsored projects, including the new parliament complex in Kabul and the Afghan-India Friendship Dam in Herat province. In May 2016, India, Iran and Afghanistan signed the Chahbahar Agreement, under which India is to invest $500 million to develop Iran's Chahbahar port on the Arabian Sea. That port is designed to facilitate increased trade between India and Afghanistan, bypassing Pakistan. The Trump Administration is providing India with a waiver under applicable Iran sanctions laws to be able to continue to develop the port.

Russia

For years Russia tacitly accepted the U.S. presence in Afghanistan as furthering the battle against radical Islamists in the region. Recently, however, in the context of renewed U.S.-Russian rivalry, Russia has taken a more active role both in the conflict (including providing some political and perhaps material support for the Taliban) and in efforts to bring it to a negotiated end.

During the 1990s, after the Soviet Union's 1989 withdrawal from Afghanistan and subsequent breakup (see Appendix B), Russia supported the Northern Alliance against the Taliban with some military equipment and technical assistance in order to blunt Islamic militancy emanating from Afghanistan.118 After 2001, Russia agreed not to hinder U.S. military operations, later cooperating with the United States in developing the Northern Distribution Network supply line to Afghanistan. About half of all ground cargo for U.S. forces in Afghanistan flowed through the Northern Distribution Network from 2011 to 2014, despite the extra costs as compared to the route through Pakistan.119 Nevertheless, Russian-U.S. collaboration in Afghanistan, a relative bright spot in the two countries' relationship, has suffered in light of a more general deterioration of bilateral ties.

Moscow has taken a markedly more assertive role in Afghanistan since at least late 2015. U.S. officials have differed in how they characterize both the nature of and motivation for Russia's actions, but there appears to be widespread agreement that they represent a challenge to U.S. goals. Former Secretary Mattis said that Russia was "choosing to be strategic competitors" with the United States in Afghanistan, while former U.S. commander General Nicholson said the Russians were motivated by a desire to "undermine the United States and NATO."120 Other analysts have noted Russian anxieties about a potential long-term U.S. military presence in Central Asia, a region that has been in Moscow's sphere of influence since the 19th century.121 The Russian government frames its renewed interest in Afghanistan as a reaction to the growth of ISKP, for which Russia faults the United States. However, Russian descriptions of ISKP strength and geographic location generally surpass estimates by the United States and others, perhaps overstating the threat to justify supporting the Taliban, which Russia may see as less of a direct danger.122

The Washington Post, citing unnamed U.S. defense officials, reported in 2017 that Russia had provided weapons (including heavy machine guns) to the Taliban ostensibly to be used against the Islamic State affiliated fighters, but that the weapons had surfaced in places far from ISKP strongholds, like Helmand province.123 Russia had previously condemned such claims as "groundless" and "absurd fabrications;" a Taliban spokesman also denied the reports, saying "our contacts with Russia are for political and diplomatic purposes only."124 General Nicholson echoed such reports in a March 2018 interview, saying, "We've had weapons brought to this headquarters and given to us by Afghan leaders and said, this was given by the Russians to the Taliban."125

Russia also has sought to establish itself as a player in Afghanistan by its efforts to bring about a negotiated settlement. In December 2016, Moscow hosted Chinese and Pakistani officials in a meeting that excluded Afghan representatives, drawing harsh condemnation from the Afghan government.126 Significantly, Russia has also hosted Taliban officials for talks in Moscow, in February and May 2019—meetings in which Afghan government representatives did not participate.

China

China's involvement in Afghanistan, with which it shares a small, remote border, is motivated by several interests, of which reducing what China perceives as a threat from Islamist militants in Afghanistan and securing access to Afghan minerals and other resources are considered the most important.

Since 2012, China has deepened its involvement in Afghan security issues and has taken on a more prominent role as a potential mediator in Afghan reconciliation, though its role in both is still relatively modest. In 2012, China signed a series of agreements with Afghanistan, one of which reportedly promised Chinese training and funding for Afghan forces, though some reports, citing participants, question how beneficial that training is.127 In October 2014, China hosted Ghani for his first working trip abroad as president, during which China agreed to provide $330 million in bilateral aid over the coming three years, in addition to other forms of support. As a consequence of that visit, some Taliban figures reportedly visited China, apparently accompanied by Pakistani security officials, as part of an effort to promote an Afghan political settlement.128

In 2018, Chinese officials denied reports of plans to build a military base in the Wakhan Corridor, a sparsely inhabited sliver of Afghanistan with which China has a 47-mile border, saying, "no Chinese military personnel of any kind on Afghan soil at any time."129 China did agree to help Afghanistan stand up a "mountain brigade" in the Wakhan Corridor to take on any Islamist fighters who return to the country from the Middle East. China fears that some of the returned fighters may be Chinese nationals who may be planning attacks in China's northwestern region of Xinjiang, across the border from Afghanistan.130 In a September 2018 interview with Reuters, Afghanistan's ambassador to Beijing said China will be doing "some training" of Afghan troops as part of that effort, but in China, rather than in Afghanistan, as some reports had suggested.131

Looking ahead, China may be seeking to play a larger role in reconciliation efforts in Afghanistan; China has considerable influence with its ally Pakistan, which is generally considered the most important regional player in the Afghan conflict. China participates in various multilateral fora dedicated to fostering Afghan peace talks, such as the Quadrilateral Coordination Group (comprising representatives from Afghanistan, China, Pakistan, and the United States). Chinese officials reportedly have met with Taliban representatives several times in the past year as well.132