Parliamentary Reference Sources: Senate

Changes from May 28, 2019 to October 3, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Parliamentary Reference Sources: Senate

Contents

- Introduction

- Principles of Senate Parliamentary Practice

- Multiple Sources of Senate Procedure

- Constitutional Rulemaking Authority of the Senate

- Enforcing the Senate Rules and Precedents

- The Senate's Reliance on Unanimous Consent

- The Importance of Precedents

- The Senate's Unofficial Practices

- The Senate Manual and Authorities It Contains

- Standing Rules of the Senate

- Permanent Standing Orders

- Laws Relating to the Senate

- Constitution

- Additional Parliamentary Resources Included in the Manual

- Rules for Regulation of the Senate Wing

- Rules for Impeachment Trials

- Cleaves' Manual on Conferences

- Annotated Excerpt from the Manual

- Other Official Senate Parliamentary Authorities

- Riddick's Senate Procedure

- Standing Orders by Unanimous Consent

- Unanimous Consent (UC) Agreements

- Committee Rules of Procedure

- Rulemaking Statutes and Budget Resolutions

- Legislative Reorganization Acts

- Expedited Procedures

- Budget Process Statutes

- Procedural Provisions in Budget Resolutions

- Rules of Senate Party Conferences

- Publications of Senate Committees and Offices

- Electronic Senate Precedents

- A Compendium of Laws and Rules of the Congressional Budget Process

- Senate Cloture Rule

- Treaties and Other International Agreements

- Enactment of a Law

- How Our Laws Are Made

Summary

The Senate's procedures are determined not only by its standing rules but also by standing orders, published precedents, committee rules, party conference rules, and informal practices. The Constitution and rulemaking statutes also impose procedural requirements on the Senate.

Official parliamentary reference documents and other publications set forth the text of the various authorities or provide information about how and when they govern different procedural situations. Together, these sources establish the parameters by which the Senate conducts its business. They provide insight into the Senate's daily proceedings, which can be unpredictable. In order to understand Senate procedure, it is often necessary to consider more than one source of authority. For example, the Senate's standing rules provide for the presiding officer to recognize the first Senator who seeks recognition on the floor. By precedent, however, when several Senators seek recognition at the same time, the majority leader is recognized first, followed by the minority leader. This precedent may have consequences for action on the floor.

This report reviews the coverage of Senate parliamentary reference sources and provides information about their availability to Senators and their staff. Among the resources presented in this report, four may prove especially useful to understand the Senate's daily order of business: the Senate Manual, Riddick's Senate Procedure, the rules of the Senate standing committees, and the publication of unanimous consent agreements.

The Senate sets forth its chief procedural authorities in a Senate document called the Senate Manual (S.Doc. 113-1), a new edition of which appears periodically. The Manual contains the text of the Senate's standing rules, permanent standing orders, laws relating to the Senate, and the Constitution, all of which establish key Senate procedures. The most recent version of the Manual can be accessed online at govinfo.gov, a website of the Government Publishing Office (GPO) at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/SMAN-113/pdf/SMAN-113.pdf. It is also accessible via the Senate resources page of Congress.gov (a website of the Library of Congress) at https://www.congress.gov/resources/display/content/Senate.

Riddick's Senate Procedure (S.Doc. 101-28) presents a catalog of Senate precedents arranged alphabetically on topics ranging from adjournment to recognition to voting. Summaries of the precedents are accompanied by citations to the page and date in the Congressional Record or the Senate Journal on which the precedent was established. Individual chapters of Riddick's Senate Procedure are available for download through govinfo.gov at https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-RIDDICK-1992. A searchable version is also accessible via the Senate resources page of Congress.gov at https://www.congress.gov/resources/display/content/Senate.

The Senate's standing rules require each standing committee to adopt its own rules of procedure. These rules may cover topics such as how subpoenas are issued. Each Congress, the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration prepares a compilation of these rules and other relevant committee materials, such as jurisdiction information, in a document titled Authority and Rules of Senate Committees. The most recent version (S.Doc. 115-4116-6) is available via govinfo.gov at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CDOC-115sdoc4116sdoc6/pdf/CDOC-115sdoc4116sdoc6.pdf.

To facilitate the legislative process, the Senate often conducts its business through unanimous consent agreements that may schedule the time for taking up a measure or specify what motions are in order during its consideration. These can be found, via Congress.gov, in the Congressional Record (https://www.congress.gov/) and the Senate Calendar of Business or the Executive Calendar (https://www.congress.gov/resources/display/content/Calendars+and+Schedules).

Introduction

The Senate's procedures are not based solely on its standing rules. Rather, the foundations of Senate procedure also include the body's standing orders, published precedents, rulemaking statutes, constitutional mandates, committee rules, party conference rules, and informal practices.

Various reference sources provide information about how and when these procedural authorities of the Senate govern specific parliamentary situations, and together, they establish the framework by which the Senate conducts its business. This report discusses the contents, format, and availability of reference sources that provide information about contemporary procedures in the Senate. The report covers official documents that set forth the Senate rules, precedents, or other sources of parliamentary authority, such as the Senate Manual, Riddick's Senate Procedure, and the rules adopted by Senate committees. The report also discusses publications on procedure from committees and offices of the Senate and the rules of the Senate's party conferences.

Prior to describing the individual parliamentary reference sources, this report reviews some principles of Senate parliamentary procedure that are applicable when using and evaluating information from these sources.

The report then covers the Senate's official parliamentary reference sources. These are documents that set forth authoritativeauthoritative statements of Senate rules, procedures, and precedents. Senators often cite these official sources when raising a point of order or defending against one.

Finally, the report reviews the rules of the party conferences, as well as a number of additional publications of committees and other offices of the Senate. Although these resources do not themselves constitute official parliamentary authorities of the Senate, they nevertheless provide background information on official parliamentary authorities.

Text boxes throughout the report provide information on how to consult a source, or group of sources, with an emphasis on online access. This report aims to present access points to these reference sources that are relevant for Senators and congressional staff and does not present an exhaustive list of websites and other locations where these references can be found.

Two appendixes supplement the information on parliamentary reference sources provided throughout the report. Appendix A provides a selected list of CRS products on Senate procedure. An overview of the two primary websites through which many of the resources included in this report can be accessed is provided in Appendix B.

This report assumes a basic familiarity with Senate procedures. Official guidance on Senate procedure is available from the Office of the Senate Parliamentarian. CRS staff can also assist with clarifying Senate rules and procedures.

Principles of Senate Parliamentary Practice

The Senate applies the regulations set forth in its various parliamentary authorities in accordance with several principles that remain generally applicable across the entire range of parliamentary situations. Among these principles may be listed the following: (1) Senate procedures derive from multiple sources; (2) the Senate has the constitutional power to make its own rules of procedure; (3) Senators must often initiate enforcement of their rules; (4) the Senate conducts much of its business by unanimous consent; (5) the Senate usually follows its precedents; and (6) the Senate adheres to many informal practices. Each of these principles is discussed below.

Multiple Sources of Senate Procedure

The standing rules of the Senate may be the most obvious source of Senate parliamentary procedure, but they are by no means the only one. Other sources of Senate procedures include:

- requirements imposed by the Constitution,

- standing orders of the Senate,

- precedents of the Senate,

- statutory provisions that establish procedural requirements,

- rules of procedure adopted by each committee,

- rules of the Senate's party conferences,

- procedural agreements entered into by unanimous consent, and

- informal practices that the Senate adheres to by custom.

In order to answer a question about Senate procedure, it is often necessary to take account of several of these sources. For example, Rule XIX of the Senate's standing rules provides that "the presiding officer shall recognize the Senator who shall first address him." When several Senators seek recognition at the same time, however, there is precedent that "priority of recognition shall be accorded to the majority leader and minority leader, the majority manager and minority manager, in that order."1 This precedential principle can have consequences on the Senate floor. For example, it allows the majority leader the opportunity to be recognized to offer the debate-ending motion to table or to propose amendments. Familiarity with this Senate practice, and not the standing rule alone, is key to an understanding of how the Senate conducts its business.

Constitutional Rulemaking Authority of the Senate

Article I of the Constitution gives the Senate the authority to determine its rules of procedure. There are two dimensions to the Senate's constitutional rulemaking authority. First, the Senate can decide what rules should govern its procedures. The Senate exercises this rulemaking power when it adopts an amendment to the standing rules, or creates a new standing rule, by majority vote.2 The Senate also uses its rulemaking power when it creates standing orders and when it enacts rulemaking provisions of statutes such as those included in the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974. Standing orders and rulemaking provisions of law have the same standing and effect as the Senate's standing rules, because all are created through an exercise of the Senate's constitutional rulemaking authority.

The second dimension to the Senate's rulemaking authority is that the chamber can decide when its rules of procedure should not govern. In practical terms, this means the Senate can waive its rules by unanimous consent. Under a provision of Senate Rule V, the body can also suspend its rules by a two-thirds vote, although this course is procedurally difficult and rare. The Senate has no established means to supersede its rules by majority vote, an option that is available to the House through the adoption of a "special rule."3 The Senate can achieve the effect of waiving a rule if a majority votes either to overrule a decision of the presiding officer to sustain a point of order or, instead, votes not to sustain a point of order that has been submitted to the Senate for decision.4 Action of this kind not only sets the rule aside for the immediate situation but also thereby establishes a precedent to govern subsequent rulings of the presiding officer regarding the meaning and applicability of that rule.

Enforcing the Senate Rules and Precedents

The Senate's presiding officer (whether it is the Vice President or a Senator of the majority party) does not always call a violation of Senate rules to the chamber's attention.5 The Senate can violate its procedures unless a Senator, at the right moment, makes a point of order that the proposed action violates the standing rules, a constitutional provision, or another authoritative source of procedure (i.e., standing order, rulemaking statute, or unanimous consent agreement).6

When a point of order is raised, the presiding officer usually makes a ruling without debate. Under Rule XX, the presiding officer has the option of submitting "any question of order for the decision of the Senate." This is rare but may occur if the existing rules and precedents do not speak clearly on the parliamentary question at hand.7

Any Senator can appeal the ruling of the presiding officer on a point of order. The Senate might then decide, usually by majority vote, to uphold or overturn the presiding officer's decision.8 This vote establishes a precedent that guides the presiding officer in deciding future questions of order unless this precedent is overturned by another decision of the Senate or by a rules change. Some rulemaking statutes require a supermajority vote to overturn on appeal the presiding officer's ruling on a point of order.9

Parliamentary actions taken on the basis of an informal practice, or pursuant to a rule of one of the Senate's party conferences, are not enforceable on the Senate floor. While informal practices and party conference rules can affect actions taken in Senate committee and the Senate floor, they are not invoked through an exercise of the Senate's constitutional rulemaking authority. Hence, they do not have the authority of Senate rules and procedures. Informal practices evolve over the years as custom and party conference rules are adopted and enforced by each party.

The Senate's Reliance on Unanimous Consent

The Senate's standing rules emphasize the rights of individual Senators, in particular by affording each Senator the right to debate at length and the right to offer amendments that are not relevant to the bill under consideration. It would be difficult for the Senate to act on legislation in a timely fashion if Senators always exercised these two powerful rights. For this and other reasons, the Senate often agrees, by unanimous consent, to operate outside its standing rules.10

In practice, Senate business is frequently conducted under unanimous consent (UC) agreements.11 UC agreements may be used to bring up a measure, establish how the measure will be considered on the floor, and control how the Senate will consider amendments.12

Given the fact that it takes only one Senator to object to a UC agreement, each agreement is carefully crafted by the majority leader in consultation with the minority leader, leaders of the committee with jurisdiction over the bill in question, and other Senators who express an interest in the legislation. The agreement is then orally propounded on the floor, usually by the majority leader, and takes effect if no Senator objects.

Once entered into, a UC agreement has the same authority as the Senate's standing rules and is enforceable on the Senate floor. Consent agreements have the effect of changing "all Senate rules and precedents that are contrary to the terms of the agreement."13 Once entered into, UC agreements can be altered only by unanimous consent.

The Importance of Precedents

The published precedents of the Senate detail the ways in which the Senate has interpreted and applied its rules. The precedents both complement and supplement the rules of the Senate. As illustrated by the example of according priority recognition to the majority leader, it may be necessary to refer to the precedents for guidance on how the Senate's rules are to be understood. The brevity of the Senate's standing rules often makes the body's precedents particularly important as a determinant of proceedings.

Precedents are analogous to case law in their effect. Just as attorneys in court will cite previous judicial decisions to support their arguments, Senators will cite precedents of the Senate to support a point of order, defend against one, or argue for or against an appeal of the presiding officer's ruling on a point of order. Similarly, the presiding officer will often support his or her ruling by citing the precedents. In this way, precedents influence the manner in which current Senate rules are applied by relating past decisions to the specific case before the chamber.

Most precedents are established when the Senate votes on questions of order (i.e., on whether to uphold or overturn a ruling of the presiding officer or on a point of order that the presiding officer has submitted to the body) or when the presiding officer decides a question of order and the ruling is not appealed. Historically, the Senate follows such precedents until "the Senate in its wisdom should reverse or modify that decision."14 Precedents can also be created when the presiding officer responds to a parliamentary inquiry.

Precedents do not carry equal weight. Inasmuch as the Senate itself has the ultimate constitutional authority over its own rules, precedents reflecting the judgment of the full Senate are considered the most authoritative. Accordingly, precedents based on a vote of the Senate have more weight than those based on rulings of the presiding officer. Responses of the presiding officer to parliamentary inquiries have even less weight, because they are not subject to a process of appeal through which the full Senate could confirm or contest them. In addition, more recent precedents generally have greater weight than earlier ones, and a precedent that reflects an established pattern of rulings will have more weight than a precedent that is isolated in its effect. All precedents must also be evaluated in the historical context of the Senate's rules and practices at the time the precedents were established. Senators seeking precedents to support or rebut an argument may consult the Senate Parliamentarian's Office.

The Senate's Unofficial Practices

Some Senate procedural actions are based on unofficial practices that have evolved over the years and become accepted custom. These practices do not have the same standing as the chamber's rules, nor are they compiled in any written source of authority. Although these unofficial practices cannot be enforced on the Senate floor, many of them are well established and customarily followed. Some contemporary examples of unofficial practices include respecting "holds" that individual Senators sometimes place on consideration of specific measures and giving the majority leader or a designee the prerogative to offer motions to proceed to the consideration of a bill, recess, or adjourn.

The Senate Manual and Authorities It Contains

The Senate Manual compiles in a single document many of the chief official parliamentary authorities of the Senate.15 The publication, prepared under the auspices of the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, appears periodically in a new edition as a Senate document. The current edition, which was issued in the 113th Congress, contains the text of the following parliamentary authorities (the titles given are those found in the Manual):

- Standing Rules of the Senate;

- Nonstatutory Standing Orders Not Embraced in the Rules, and Resolutions Affecting the Business of the Senate;

- Rules for Regulation of the Senate Wing of the U.S. Capitol and Senate Office Buildings;

- Rules of Procedure and Practice in the Senate When Sitting on Impeachment Trials;

- Cleaves' Manual of the Law and Practice in Regard to Conferences and Conference Reports;

- General and Permanent Laws Relating to the U.S. Senate; and

- Constitution of the United States of America.

The following sections of this part of the report discuss each of these authorities in more detail.

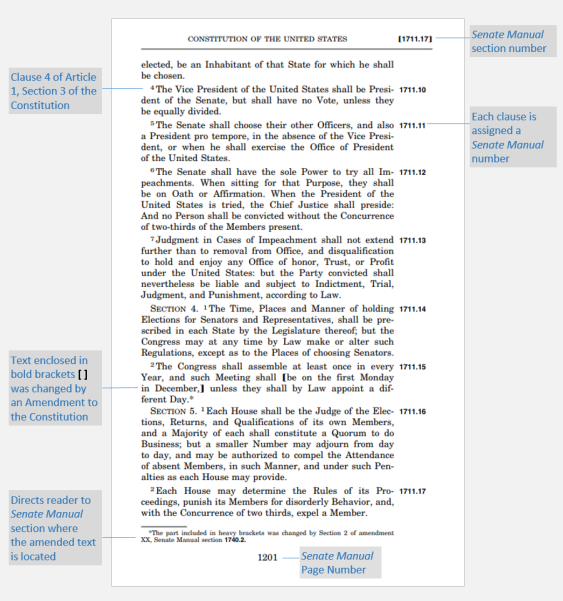

The Manual contains a general table of contents and an index. Some of the respective components in the Manual have their own tables of contents and indices that provide additional details about that source. Individual provisions of each procedural authority are assigned section numbers that run throughout the Manual in a single sequence and always appear in bold type.16 The section numbers assigned to the standing rules correspond to the numbers of the rules themselves. For example, paragraph 2 of Senate Rule XXII, which sets forth the cloture rule, is found at section 22.2 of the Manual. The indices to the Manual direct readers to these section numbers. The indices indicate, for example, that the motion to adjourn is covered in Manual sections 6.4, 9, and 22.1. For this reason, the document is cited by section number rather than page number.

|

Senate Manual (and the Authorities It Contains) U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Senate Manual, 113th Cong., 1st sess., 113-1 (Washington: GPO, 2014). Online: The Senate Manual can be accessed via govinfo.gov, a website of the Government Publishing Office (GPO), at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/SMAN-113/pdf/SMAN-113.pdf. The GPO version is also accessible through Congress.gov at https://www.congress.gov/resources/display/content/Senate. Print: When published, the Senate Manual is distributed to offices of Senators and committees. Limited copies are available from Senate Printing and Document Services. The Senate Manual can also be consulted at the CRS La Follette Congressional Reading Room (reserved for use by Members of Congress, their families, and their staff). |

Standing Rules of the Senate

The Senate does not re-adoptreadopt its standing rules at the beginning of each new Congress but instead regards its rules as continuing in effect without need for re-adoptionreadoption.17 The Senate follows this practice on grounds that it is a continuing body; only one-third of its membership enters on new terms of office after every biennial election, so a quorum is continuous. Changes to the standing rules are proposed in the form of Senate resolutions, which can be adopted by majority vote. At the start of the 116th Congress, there were 44 standing rules of the Senate.

The standing rules of the Senate are set forth at the beginning of the Manual.18 The standing rules appear with footnotes indicating amendments adopted since their last general revision in 1979. The footnotes cite the resolution adopted by the Senate to make the rules change. The Manual presents the standing rules with an itemized table of contents and a detailed, separate index.

Permanent Standing Orders

From time to time, the Senate adopts a resolution or agrees to a unanimous consent request to create a standing order of the Senate. A standing order, while not embraced in the standing rules, operates with the same authority as a standing rule and is enforceable on the Senate floor in the same way. A standing order remains in effect until repealed by the Senate unless otherwise specified in the order itself.

The standing orders the Senate has created by adopting resolutions and that remain in effect are compiled in the Manual in sections 60-139.19 This is the only readily available compilation of permanent standing orders currently in effect. In addition to setting forth the text of these standing orders, the Manual provides (1) a heading stating the subject matter of each and (2) a citation to the Senate resolution(s) that created and amended it.20 Footnotes provide supplementary information, such as noting when references in the standing order (e.g., the name of a committee) were changed.21

Laws Relating to the Senate

The most voluminous component of the Manual presents a compilation of "General and Permanent Laws Relating to the U.S. Senate." The statutory excerpts appear in their codified version (i.e., organized under the relevant title, chapter, and section of the United States Code). The Manual provides a separate table of contents to the provisions included, but it sets forth the provisions themselves without citation or commentary.

Although most of the selected provisions address the administration and operations of the Senate, some of them bear on questions related to Senate procedure, such as those concerning Senators' oaths of office, officers of the Senate, and investigative procedure in Senate committees. The compilation also includes "rulemaking statutes," or statutory provisions that establish procedures for Senate action on specified measures. Rulemaking provisions of statute are discussed further in the section below on "Rulemaking Statutes and Budget Resolutions."

Constitution

The U.S. Constitution imposes several procedural requirements on the Senate. For example, Article I, Section 5, requires the Senate to keep and publish an official Journal of its proceedings, requires a majority quorum to conduct business on the Senate floor, and mandates that a yea and nay vote take place upon the request of one-fifth of the Senators present. The Constitution also bestows certain exclusive powers on the Senate: Article II, Section 2, grants the Senate sole authority to provide advice and consent to treaties and executive nominations, and Article I, Section 3, gives the Senate the sole power to try all impeachments.

The Manual presents the text of the Constitution and its amendments. The Manual places bold brackets around text that has been amended, and a citation directs readers to the Manual section containing the amendment. The Manual also provides historical footnotes about the ratification of the Constitution and each amendment, as well as a special index to the text.

Additional Parliamentary Resources Included in the Manual

Rules for Regulation of the Senate Wing

Senate Rule XXXIII authorizes the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration to make "rules and regulations respecting such parts of the Capitol ... as are or may be set apart for the use of the Senate." The rule is framed to extend this authority to the entire Senate side of the Capitol complex and explicitly includes reference to the press galleries and their operation.22 Several of the regulations adopted by the Committee on Rules and Administration under this authority have a bearing on floor activity, including ones addressing (1) the floor duties of the secretaries for the majority and for the minority, (2) the system of "legislative buzzers and signal lights," and (3) the "use of display materials in the Senate chamber."23

Rules for Impeachment Trials

The Senate has adopted a special body of rules to govern its proceedings when sitting as a Court of Impeachment to try impeachments referred to it by the House of Representatives. The Senate treats these rules, like its standing rules, as remaining permanently in effect unless altered by action of the Senate. On occasion, the Senate has adopted amendments to these rules.24

Cleaves' Manual on Conferences

Cleaves' Manual presents a digest of the rules, precedents, and other provisions of parliamentary authorities governing Senate practice in relation to the functioning of conference committees and conference reports as they stood at the end of the 19th century. Although rules and practices governing conferences to resolve legislative differences between the House and the Senate have since altered in many respects, and many of the precedents now applicable to conferences were established after Cleaves' Manual was prepared, many of the principles set forth in Cleaves' Manual still apply to current practice.

As presented in the Senate Manual, Cleaves' Manual includes excerpts from the Manual of Parliamentary Practice prepared by Thomas Jefferson as Vice President at the turn of the 19th century, as well as statements by other Vice Presidents and by Speakers, excerpts from Senate rules, statements of principles established by precedent, and explanatory notes. In addition, a section at the end sets forth forms for conference reports and joint explanatory statements.

Annotated Excerpt from the Manual

The page below displays an excerpt from the section of the Manual that presents the Constitution. The excerpt shows the format of the Manual, and the annotations explain some of the key features for using the reference, such as distinguishing between the Manual section numbers in bold text and the Manual page numbers at the bottom of the page.

Other Official Senate Parliamentary Authorities

Riddick's Senate Procedure

Riddick's Senate Procedure, often referred to simply as Riddick's, is the most comprehensive reference source covering Senate rules, precedents, and practices. Its principal purpose is to present a digest of precedents established in the Senate. The current edition, published in 1992, covers significant Senate precedents established from 1883 to 1992.25 It was written by Floyd M. Riddick, Parliamentarian of the Senate from 1964 to 1974, and Alan S. Frumin, Parliamentarian of the Senate from 1987 to 1995 and 2001 to 2012 and Parliamentarian Emeritus since 1997.26

As implied by its full title, Riddick's Senate Procedure: Precedents and Practices presents Senate precedents as well as discussions of the customary practice of the Senate. It is organized around procedural topics, which are presented in alphabetical order. For each procedural topic, the volume first presents a summary of the general principles governing that topic followed by the text of relevant standing rules, constitutional provisions, or rulemaking provisions of statute. Summaries of the principles established by individual precedents are then presented under subject headings and subtopics organized in alphabetical order. For example, the topic "Cloture Procedure" has a subject heading "Amendments After Cloture," which is further divided into 18 topics, such as "Drafted Improperly" and "Filing of Amendments."

Footnotes provide citations to the date, the Congress, and the session when each precedent was established and to the Congressional Record or Senate Journal pages where readers can locate the pertinent proceedings (e.g., "July 28, 1916, 64-1, Record, pp. 11748-50"). Footnote citations beginning with the word see indicate proceedings based on presiding officers' responses to parliamentary inquiries. Citations without see indicate precedents created by ruling of the presiding officers or by votes of the Senate.

An appendix to Riddick's Senate Procedure contains sample floor dialogues showing the terminology that Senators and the presiding officer use in different parliamentary situations. Examples of established forms used in the Senate (e.g., for various types of conference reports, the motion to invoke cloture) are also provided. Useful supplementary information appears in brackets throughout the appendix. The appendix also has a separate index.

The publication's main index is useful for locating information on specific topics of Senate procedure. The table of contents lists only the main procedural topics covered in the book.

|

Riddick's Senate Procedure U.S. Congress, Senate, Riddick's Senate Procedure: Precedents and Practices, prepared by Floyd M. Riddick and Alan S. Frumin, 101st Cong., 1st sess., S.Doc. 101-28 (Washington: GPO, 1992). Online: Individual topical chapters of Riddick's Senate Procedure are available for download through govinfo.gov at https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-RIDDICK-1992. For a full text search of Riddick's Senate Procedure, visit https://www.riddick.gpo.gov/home.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1. The searchable version is also accessible via Congress.gov at https://www.congress.gov/resources/display/content/Senate. Print: Riddick's Senate Procedure is distributed to the offices of new Senators. Limited copies are available from Senate Printing and Document Services. |

Standing Orders by Unanimous Consent

In addition to the standing orders created by resolution, the Senate also establishes standing orders by agreeing to unanimous consent requests. These agreements usually make these standing orders effective only for the duration of a Congress or some other limited period. The current Senate practice is to adopt an established package of these standing orders at the beginning of each successive Congress. Standing orders of this kind are not included in the Senate Manual but appear only in the Congressional Record on the day they are adopted. For example, on the first day of the 116th Congress in 2019, the Senate adopted 11 unanimous consent agreements re-establishingreestablishing standing orders from the previous Congress on topics such as the procedures for allowing Members' staff access to the Senate floor during the consideration of matters and when the Senate Ethics Committee is permitted to meet.27

Unanimous Consent (UC) Agreements

UC agreements also include orders that function as parliamentary authorities in the Senate. These consent agreements establish conditions for floor consideration of specified measures, which, in relation to those measures, override the regulations established by the standing rules and other Senate parliamentary authorities. Commonly, agreements of this kind may set the time for taking up or for voting on the measure, limit the time available for debate, or specify what amendments and other motions are in order.

UC agreements constitute parliamentary authorities of the Senate because, once propounded and accepted on the Senate floor, they are enforced just as are the Senate's standing rules and other procedural authorities. UC agreements are propounded orally, and therefore, they are printed in the Congressional Record. Those that are accepted are printed at the front of the Senate's daily Calendar of Business and Executive Calendar until they are no longer in effect.

|

Unanimous Consent Agreements UC agreements are printed in the Congressional Record once they are propounded on the Senate floor. Accepted agreements are printed at the front of the Senate's daily Calendar of Business or the Executive Calendar until they are no longer in effect. Online: The Congressional Record for the 116th Congress is available in searchable form through Congress.gov at https://www.congress.gov/. The Senate Calendar of Business and Executive Calendar are both available at Congress.gov at https://www.congress.gov/resources/display/content/Calendars+and+Schedules and govinfo.gov at https://www.govinfo.gov/app/collection/ccal/116. Print: Senate offices may receive printed copies of the Congressional Record and the Senate's Calendar of Business delivered to their offices. |

Committee Rules of Procedure

Rule XXVI, paragraph 2, of the Senate's standing rules requires that each standing committee adopt written rules of procedure and publish these rules in the Congressional Record not later than March 1 of the first session of each Congress.28 Committee rules cover important aspects of the committee stage of the legislative process, such as the procedures for preparing committee reports and issuing subpoenas, and committees are responsible for enforcing their own rules. Subcommittees may also have their own supplemental rules of procedure. Committee rules of procedure do not supersede those established by the standing rules of the Senate.

Each committee's rules appear in the Congressional Record on the day they are submitted for publication. Some committees also publish their rules in a committee print, or in the committee's interim or final "Legislative Calendar," and many post them on theirthe committee websites. In addition, the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration issues a document each Congress that compiles the rules of procedure adopted by all Senate committees. This document, Authority and Rules of Senate Committees, also presents the jurisdiction statement for each committee from Rule XXV of the Senate's standing rules as well as related information, such as provisions of public law affecting committee procedures.29

|

Rules of Senate Committees U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Authority and Rules of Senate Committees, Online: Authority and Rules of Senate Committees is available through govinfo.gov at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/ Print: Authority and Rules of Senate Committees for the |

Rulemaking Statutes and Budget Resolutions

The constitutional grant to each chamber of Congress of authority over its own rules permits the Senate to establish procedural regulations through simple resolutions, which are adopted by the Senate alone. In certain cases, the Senate institutes procedures through provisions included in statutory measures (bills and joint resolutions), which can become effective only through agreement between both houses and presentation to the President (or through concurrent resolutions, which require agreement between both houses). Given that these procedures are created through an exercise of each chamber's constitutional rulemaking authority, they have the same standing as Senate and House rules. A statute or concurrent resolution that contains "rulemaking provisions," in this sense, often incorporates a section titled "Exercise of Rulemaking Power." This section asserts the rulemaking authority of each chamber by declaring that the pertinent provisions "shall be considered as part of the rules of each House" and are subject to being changed "in the same manner ... as in the case of any other rule of such House"—that is, for example, by adoption of a simple resolution of the Senate.30

In the Senate, statutory rulemaking provisions are principally of three kinds: (1) those derived from Legislative Reorganization Acts, (2) those establishing expedited procedures for consideration of specific classes of measures, and (3) those derived from the Congressional Budget Act and related statutes governing the budget process. In addition, provisions regulating action in the Senate (or House of Representatives, or both) in the congressional budget process may be contained in congressional budget resolutions, which are concurrent resolutions adopted pursuant to the Congressional Budget Act.

Legislative Reorganization Acts

The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946 (P.L. 79-601, 60 Stat. 812) and the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 (P.L. 91-510, 84 Stat. 1140) are important rulemaking statutes that affected legislative procedures. Many rulemaking provisions in these statutes were later incorporated into the Senate's standing rules, and some others appear in the compilation of Laws Relating to the Senate presented in the Senate Manual, as discussed earlier.

Expedited Procedures

The term rulemaking statute is most often used in connection with laws that include provisions specifying legislative procedures to be followed in the Senate or the House, or both, in connection with the consideration of a class of measure also specified by the statute. This type of rulemaking statute, commonly referred to as "expedited procedures" or "fast track" provisions, defines special procedures for congressional approval or disapproval of specified actions proposed to be taken by the executive branch or independent agencies. A well-known example includes the Congressional Review Act, which provides for special procedures Congress can use to overturn a rule issued by a federal agency.31 Some of these expedited procedures are listed in the Senate Manual section titled "General and Permanent Laws Relating to the U.S. Senate."32

Budget Process Statutes

Four of the most important rulemaking statutes define specific procedures for considering budgetary legislation: the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 (commonly known as the Congressional Budget Act), the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act (the "Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act"), the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990, and the Budget Control Act of 2011. For example, Section 305(b) of the Congressional Budget Act defines Senate floor procedures for considering the congressional budget resolution.

Procedural Provisions in Budget Resolutions

When adopted, the chief purpose of the concurrent resolution on the budget (provided for in the Congressional Budget Act) is to establish, between the House and the Senate, a budget plan for the fiscal year. The Senate has often included in this congressional budget resolution supplementary procedural regulations to govern subsequent action on spending bills or other budget-related measures. Many of these procedural provisions institute new points of order that, similar to those established by the Congressional Budget Act itself, are available against budgetary measures or provisions contained in these measures. For example, beginning in 1993, some budget resolutions have established "pay-as-you-go" (PAYGO) procedures for Senate consideration of legislation affecting direct spending and revenues.33

The procedures established by these provisions may be made applicable only to budgetary action for the coming year or an established time period, but they may also be established as permanent procedures that are altered or abolished only by further action in a subsequent budget resolution. Procedures set forth in congressional budget resolutions are not comprehensively compiled in a single source and may best be identified by examining the texts of adopted congressional budget resolutions for successive years.

|

Rulemaking Provisions in Statutes and Budget Resolutions A discussion of statutory expedited procedures for "Congressional Approvals and Disapprovals" appears in Riddick's Senate Procedure at pages 496-501. Rulemaking statutes related to the congressional budget process are presented in A Compendium of Laws and Rules of the Congressional Budget Process (discussed below) and Riddick's Senate Procedure on pages 502-642. Procedural provisions in budget resolutions are best identified by examining the texts of the congressional budget resolutions themselves. They can be identified via the search tools on Congress.gov at https://www. |

Rules of Senate Party Conferences

The rules of the conferences of the two parties in the Senate are not adopted by the Senate itself, and accordingly, they cannot be enforced on the Senate floor. Conference rules may nevertheless affect proceedings of the Senate, for they may cover topics such as the selection of party leaders, meetings of the conference, and limitations on committee assignments for conference members. The Senate Republican Conference adopted rules for the 116th Congress that are available online.

|

Rules of Senate Party Conferences (Online Access) An online version of the Rules of the Senate Republican Conference for the 116th Congress can be accessed via https://www.republican.senate.gov/ For the Senate Democratic Conference, no source makes available any formal rules. |

Publications of Senate Committees and Offices

Some publications prepared by committees and offices of the Senate provide valuable information about Senate parliamentary procedure and practices. While these publications are not official parliamentary reference sources, they often make reference to official sources such as the Senate's standing rules and published precedents.

Electronic Senate Precedents

Senators and their staff may access, via Webster (which is not available to the public), the Electronic Senate Precedents, a catalog of recent precedents compiled by the Office of the Parliamentarian. These unofficial documents, provided by the Office of the Secretary of the Senate, are updated periodically to reflect precedents on topics such as cloture and germaneness of amendments that were established after the publication of Riddick's Senate Procedure (1992).

A Compendium of Laws and Rules of the Congressional Budget Process

A Compendium of Laws and Rules of the Congressional Budget Process, a print of the House Committee on the Budget, presents the text of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act, and additional information related to the budget -making process, such as House and Senate rules affecting the budget process.34 Although this document was printed by the House Budget Committee, it presents valuable information related to the budgetary process in the Senate.35

Senate Cloture Rule

Senate Cloture Rule, a print prepared for the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration by CRS, was last issued during the 112th Congress (2011-12).36 The print covers the rule's history and application through its publication and may be useful to those wanting a more detailed knowledge of the cloture rule. Significantly, however, this print does not capture precedents established during the 113th (2013-142014) and 115th (2017-182018) Congresses that changed the vote thresholds for invoking cloture on various presidential nominations or the change to the post-cloturepostcloture debate time established during the 116th Congress.37

Treaties and Other International Agreements

Treaties and Other International Agreements: The Role of the United States Senate, was prepared as a print for the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations by CRS.38 The print provides detailed information about the Senate's advice and consent role, covers the procedures that govern all stages of Senate consideration of treaties and international agreements, and discusses congressional oversight of treaties and other international agreements. The latest edition (S.Prt. 106-71) appeared in the 106th Congress.

Enactment of a Law

Enactment of a Law presents a concise summary of the legislative process.39 This document, prepared by Robert B. Dove, former Parliamentarian of the Senate, explains Senate floor procedures and the functions of the various Senate officials, such as the Secretary of the Senate, the Sergeant at Arms, and the Senate Parliamentarian.

How Our Laws Are Made

How Our Laws Are Made, first published in 1953 by the House Committee on the Judiciary, provides a summary of the legislative process from the drafting of legislation to final approval and presidential action.40 While this document focuses on House procedures, it includes a review of Senate committee and floor procedures prepared by the Office of the Parliamentarian of the Senate. Although the document is intended for nonspecialists, its summary descriptions of House procedures serve as a useful reference source.

|

Publications of Senate Offices and Committees (Online Access)

|

Appendix A. Selected CRS Products on Senate Procedure

Most of these reports are available to congressional staff through the CRS home page at http://www.crs.gov. These reports may also be accessed through the Congressional Process, Administration, and Elections section of the CRS website at https://www.crs.gov/iap/congressional-process-administration-and-elections.

CRS Report 98-853, The Amending Process in the Senate, by Christopher M. Davis.

CRS Report R41003, Amendments Between the Houses: Procedural Options and Effects, by Elizabeth Rybicki.

CRS Report RL30862, The Budget Reconciliation Process: The Senate's "Byrd Rule",," by Bill Heniff Jr.

CRS Report 96-708, Conference Committee and Related Procedures: An Introduction, by Elizabeth Rybicki.

CRS Report RL30360, Filibusters and Cloture in the Senate, by Valerie Heitshusen and Richard S. Beth.

CRS Report 98-865, Flow of Business: A Typical Day on the Senate Floor, by Christopher M. Davis.

CRS Report R43563, "Holds" in the Senate, by Mark J. Oleszek.

CRS Report RS20668, How Measures Are Brought to the Senate Floor: A Brief Introduction, by Christopher M. Davis.

CRS Report 98-425, Invoking Cloture in the Senate, by Christopher M. Davis.

CRS Report 96-548, The Legislative Process on the Senate Floor: An Introduction, by Valerie Heitshusen.

CRS Report 98-306, Points of Order, Rulings, and Appeals in the Senate, by Valerie Heitshusen.

CRS Report R42929, Procedures for Considering Changes in Senate Rules, by Richard S. Beth.

CRS Report 98-696, Resolving Legislative Differences in Congress: Conference Committees and Amendments Between the Houses, by Elizabeth Rybicki.

CRS Report RL33939, The Rise of Senate Unanimous Consent Agreements, by Walter J. Oleszek.

CRS Report RL31980, Senate Consideration of Presidential Nominations: Committee and Floor Procedure, by Elizabeth Rybicki.

CRS Report 98-308, Senate Legislative Procedures: Published Sources of Information, by Christopher M. Davis.

CRS Report 98-311, Senate Rules Affecting Committees, by Valerie Heitshusen.

CRS Report 96-452, Voting and Quorum Procedures in the Senate, coordinated by Elizabeth Rybicki.

Appendix B. Senate Parliamentary Reference Information Available Online

The vast majority of the referenced links found throughout this report can be accessed through one of two "gateway" websites maintained by legislative branch organizations: Congress.gov (a website of the Library of Congress) and govinfo.gov (a website of GPO). Each of these sites provides an entry point for research into Senate procedures. The websites provided for the documents discussed in this report are current as of the report's publication date.

Congress.gov

Congress.gov is the official website for U.S. federal legislative information.41 The site is designed to provide access to accurate, timely, and complete legislative information for Members of Congress, legislative agencies, and the public. Congress.gov also contains information on topics such as nominations, public laws, communications, and treaties. It is presented by the Library of Congress using data from the Office of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives, the Office of the Secretary of the Senate, GPO, Congressional Budget Office, and CRS.

govinfo.gov

Govinfo.gov is a service of the GPO. The website provides public access to official publications of the Congress.42

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

The original version of this report was written by Richard S. Beth, former Senior Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process at CRS, and Megan S. Lynch, SpecialistSpecialist on Congress and the Legislative Process. Thank you to CRS Visual Information Specialist Amber Wilhelm for creating the graphic in this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Floyd M. Riddick and Alan S. Frumin, Riddick's Senate Procedure: Precedents and Practices, S.Doc. 101-28, 101st Cong., 2nd sess. (Washington: GPO, 1992), p. 1098. |

| 2. |

A simple majority of Senators may vote to amend the standing rules of the Senate. However, both the measure proposing the rules change and the motion to proceed to consider it are debatable and subject to a filibuster. To overcome the filibuster, it may be necessary to invoke cloture first on the motion to proceed and then on the measure. Invoking cloture on proposals to amend the Senate's standing rules directly and the motion to proceed to such a proposal requires the vote of two-thirds of Senators present and voting. See CRS Report R42929, Procedures for Considering Changes in Senate Rules, by Richard S. Beth. |

| 3. |

Special rules are resolutions reported by the House Rules Committee that specify how a measure is to be considered on the floor. Once the House adopts a special rule by a majority vote, it governs consideration of the measure. Special rules often waive procedural requirements imposed by the rules of the House or rulemaking statutes. |

| 4. |

Section 904 of the Congressional Budget Act establishes a procedure by which the Senate can vote to waive certain budget-related prohibitions and requirements. See CRS Report 97-865, Points of Order in the Congressional Budget Process, by James V. Saturno. |

| 5. |

An exception occurs when the Senate is operating under cloture. When this happens, the precedents provide that the presiding officer has the authority to rule all dilatory motions out of order on his or her own initiative. See Senate Rule XXII, paragraph 2, in Senate Manual, §22.2. |

| 6. |

See CRS Report 98-306, Points of Order, Rulings, and Appeals in the Senate, by Valerie Heitshusen. |

| 7. |

The presiding officer must submit two types of questions of order to the Senate for it to decide. First, under Rule XVI, paragraph 4, the Senate decides questions concerning the germaneness or relevance of most amendments to appropriations bills and does so without debate. Second, according to the Senate's precedents, the Senate is to decide all constitutional questions, with debate usually allowed. This practice rests on the principle that the presiding officer possesses authority only over the interpretation of procedures established by the Senate, and only the Senate itself possesses any such authority in relation to the Constitution See Riddick's Senate Procedure, pp. 989 and 1491-1492. |

| 8. |

Appeals in the Senate are usually debatable, so they are subject to a filibuster. Under certain circumstances, it may be necessary for three-fifths of the Senate to invoke cloture in order to reach a vote on the appeal. For more information, see CRS Report R42929, Procedures for Considering Changes in Senate Rules, by Richard S. Beth; and CRS Report 98-306, Points of Order, Rulings, and Appeals in the Senate, by Valerie Heitshusen. |

| 9. |

For examples of provisions that would require such a supermajority, see Section 904(d) of the Congressional Budget Act, P.L. 93-344 as amended (2 U.S.C. 621 note). In some cases, Senate rules may also be waived by three-fifths of the Senate to avoid the effects of a point of order. For example, Rule XXVIII in the Senate, which precludes conference agreements from including policy provisions deemed to be out of scope according to Senate rules and precedents, may be waived by three-fifths of all Senators duly chosen and sworn. See CRS Report RS22733, Senate Rules Restricting the Content of Conference Reports, by Elizabeth Rybicki. |

| 10. |

See CRS Report RL33939, The Rise of Senate Unanimous Consent Agreements, by Walter J. Oleszek; and CRS Report 98-310, Senate Unanimous Consent Agreements: Potential Effects on the Amendment Process, by Valerie Heitshusen. |

| 11. |

These agreements have sometimes been known as "time agreements" when they include limits on the time for debating measures, amendments, motions, or other questions. |

| 12. |

A body of precedents has developed on how UC agreements are to be interpreted and applied in different procedural situations. These precedents are covered in Riddick's Senate Procedure, pp. 1311-1369. The majority leader often calls up a measure by unanimous consent rather than by offering a motion to proceed to consideration of the measure. In most instances, the motion to proceed is debatable and hence open to a filibuster. See CRS Report RS21255, Motions to Proceed to Consider Measures in the Senate: Who Offers Them?, by Richard S. Beth and Mark J. Oleszek. |

| 13. |

Riddick's Senate Procedure, p. 1311. |

| 14. |

Riddick's Senate Procedure, p. 987. |

| 15. |

The Manual also includes a variety of historical and statistical information. This report describes only those materials included in the Manual that constitute procedural authorities. |

| 16. |

There are often gaps between the end of one section and the start of the next. |

| 17. |

This principle is now embodied in paragraph 2 of Senate Rule V. See CRS Report R42929, Procedures for Considering Changes in Senate Rules, by Richard S. Beth. |

| 18. |

The standing rules are also available in a free-standing document periodically issued by the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration. The most recent edition is Standing Rules of the Senate (S.Doc. 113-18). |

| 19. |

Standing orders adopted since the most recent publication of the Manual (e.g., S.Res. 463 in the 115th Congress) are not included. |

| 20. |

A citation to the Senate Journal is sometimes provided, especially for older standing orders. |

| 21. |

Sources for standing orders adopted by unanimous consent and effective only for a single Congress or other limited period of time are covered below in the section "Unanimous Consent Agreements." |

| 22. |

Senate Rule XXXIII, paragraph 2, in Senate Manual, §33.2. |

| 23. |

Rules II, XV, and XVII for Regulation of the Senate Wing, in Senate Manual, §§151, 164, and 166, respectively. |

| 24. |

Significant changes occurred in 1974, when an impeachment of President Richard Nixon was impending. The most recent amendments were adopted in 1986, pursuant to S.Res. 479 (99th Congress), in preparation for the trial of the impeachment of Federal District Judge Harry E. Claiborne. |

| 25. |

The Electronic Senate Precedents present a catalog of precedents established since the publication of Riddick's Senate Procedure in 1992. They are discussed in this report below. |

| 26. |

This edition is an updated and revised version of the 1981 edition, written by Riddick. Earlier editions of this and predecessor documents appeared under the names of earlier Parliamentarians of the Senate, such as Charles J. Watkins, or Chief Clerks of the Senate, such as Henry H. Gilfry, extending back to the 19th century. |

| 27. |

Senator Mitch McConnell, "Unanimous Consent Agreements," Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 165 (January 3, 2019), p. S7. |

| 28. |

According to Rule XXVI, paragraph 2, the March 1 deadline does not apply to committees established on or after February 1. Such committees must publish their rules of procedure not later than 60 days after being established. In addition, any amendments to committee rules do not take effect until they are published in the Congressional Record. |

| 29. |

|

| 30. |

For example, Sections 904(a)(1) and 904(a)(2) of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Act of 1974, P.L. 93-344. |

| 31. |

5 U.S.C. §§801-808. |

| 32. |

Selected rulemaking statutes affecting Senate procedure are also listed in Constitution, Jefferson's Manual, and Rules of the House of Representatives (H.Doc. 114-192), commonly referred to as the House Manual. |

| 33. |

For more information on PAYGO, see CRS Report RL31943, Budget Enforcement Procedures: The Senate Pay-As-You-Go (PAYGO) Rule, by Bill Heniff Jr. |

| 34. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Budget, A Compendium of Laws and Rules of the Congressional Budget Process, committee print, 114th Cong., 1st sess., H.Prt. 114-1 (Washington: GPO, 2015). |

| 35. |

Budget Process Law Annotated (Senate Print 103-49), a print of the Senate Committee on the Budget, presents statutes and additional information related to the budget process as of October 1993. This resource is no longer in print, but its great value lies in its informative annotations prepared by William G. Dauster, then chief counsel of the Committee on the Budget. These annotations provide summaries of, and citations to, important Senate precedents. |

| 36. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Senate Cloture Rule: Limitation of Debate in the Senate of the United States and Legislative History of Paragraph 2 of Rule XXII of the Standing Rules of the United States Senate (Cloture Rule), committee print, prepared by CRS, 112th Cong., 1st sess., S.Prt. 112-31 (Washington: GPO, 2011). |

| 37. |

In November 2013 and then in April 2017, the Senate set separate precedents that lowered the vote threshold for invoking cloture on certain presidential nominations from three-fifths of the full Senate to a simple majority. For more information, see CRS Report R43331, Majority Cloture for Nominations: Implications and the "Nuclear" Proceedings of November 21, 2013, by Valerie Heitshusen; and CRS Report R44819, Senate Proceedings Establishing Majority Cloture for Supreme Court Nominations: In Brief, by Valerie Heitshusen. In the 116th Congress, the Senate established a precedent for |

| 38. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Treaties and Other International Agreements: The Role of the United States Senate, committee print, prepared by CRS, 106th Cong., 2nd sess., S.Prt. 106-71 (Washington: GPO, 2001). |

| 39. |

U.S. Senate, Enactment of a Law, prepared by Robert B. Dove, Parliamentarian (Washington: GPO, 1997). |

| 40. |

U.S. Congress, House, How Our Laws Are Made, prepared by John V. Sullivan, Parliamentarian, 110th Cong., 1st sess., H.Doc. 110-49 (Washington: GPO, 2007). |

| 41. |

See https://www.congress.gov/about for more information about the website. |

| 42. |

See https://www.govinfo.gov/about for more information about the website. |