Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

Changes from May 21, 2019 to December 9, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Role of Digital Trade in the U.S. and Global Economy

- Economic Impact of Digital Trade

- Digitization Challenges

- Digital Trade Policy and Barriers

- Tariff Barriers

- Nontariff Barriers

- Localization Requirements

- Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Infringement

- National Standards and Burdensome Conformity Assessment

- Filtering, Blocking, and Net Neutrality

- Cybersecurity Risks

- U.S. Digital Trade with Key Trading Partners

- European Union

- EU-U.S. Privacy Shield

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

- Digital Single Market (DSM)

- China

- Internet Governance and the Concept of "Internet Sovereignty"

- Cyber-Theft of U.S. Trade Secrets

- Cybersecurity Laws

- Section 301 Action against China over Intellectual Property and Innovation Issues

- Digital Trade Provisions in Trade Agreements

- WTO Provisions

- General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)

- Declaration on Global Electronic Commerce

- Information Technology Agreement (ITA)

- Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Internet Treaties

- WTO Plurilateral Effort

- U.S. Bilateral and Plurilateral Agreements

- Existing U.S. Free Trade Agreements (FTAs)

- United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)

- Other International Forums for Digital Trade

- Issues for Congress

Figures

- Figure 1. Effect on World GDP (percent)

- Figure 2. Snapshot of Most Popular Websites

- Figure 3. What is Digital Trade?

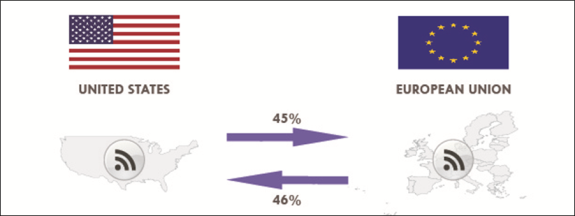

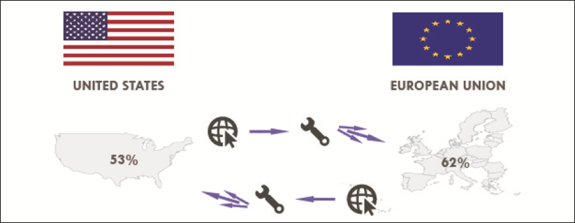

- Figure 4. Select U.S.-EU Cross-Border E-Commerce Purchases

- Figure 5. Digitally Deliverable Service Exports 2017

- Figure 6. Digitally Deliverable Services Incorporated into Global Value Chains

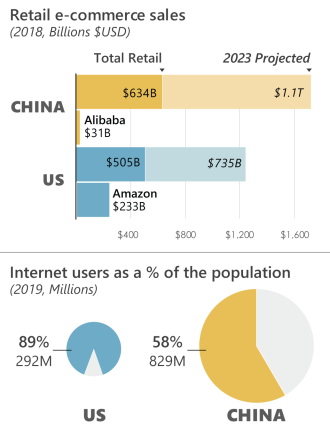

- Figure 7. The U.S. and China Digital Trade Markets

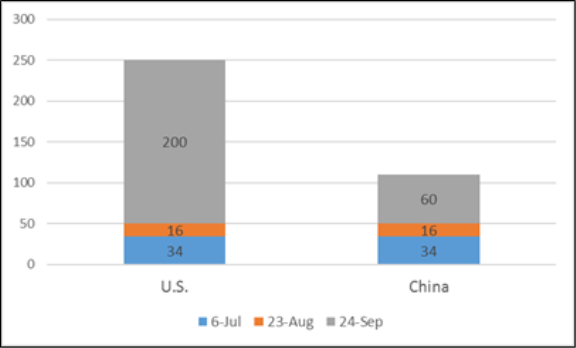

- Figure 8. Three Rounds of U.S.-China Tariff Hikes in 2018

- Figure A-1. Levels of Perceived Digital Trade Barriers in Selected Countries

Appendixes

Summary

As the global internet develops and evolves, digital trade has become more prominent on the global trade and economic policy agenda. The economic impact of the internet was estimated to be $4.2 trillion in 2016, making it the equivalent of the fifth-largest national economy. The digital economy accounted for 6.9% of current‐dollar gross U.S. domestic product (GDP) in 2017. Digital trade has been growing faster than traditional trade in goods and services.

Congress has an important role to play in shaping global digital trade policyDigital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

December 9, 2021

As the global internet expands and evolves, digital trade has become prominent on the global trade and economic policy agenda. According to the Department of Commerce, the “digital

Rachel F. Fefer,

economy” accounted for 9.6% of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 and supported 7.7

Coordinator

million U.S. jobs, or 5.0% of total U.S. employment in 2019. From 2005 to 2019, real value

Analyst in International

added for the U.S. digital economy grew at an average annual rate of 5.2% per year, outpacing

Trade and Finance

the 2.2% growth in the overall economy each year. Digital trade has been growing faster than

traditional trade in goods and services, with the pandemic further spurring its expansion.

Shayerah I. Akhtar Specialist in International

Congress plays an important role in shaping U.S. policy on digital trade, from oversight of

Trade and Finance

federal , from oversight of agencies charged with regulating cross-border data flows to shaping and considering legislation implementing

legislation to implement new trade rules and disciplines through trade negotiations. Congress also works with the executive branch to identify the rightappropriate balance between digital tradetrasde and

Michael D. Sutherland

and other policy objectives, including privacy and national security.

Analyst in International Trade and Finance

Digital trade includes end-products, such as downloaded movies, and products and services that rely on or facilitate digital trade, such as streaming services and productivity-enhancing tools like

cloud data storage and email. In 20172020, U.S. exports of information and communications technology-enabled services (excluding digital goods) were an estimated $439technologies (ICT) services increased to $84 billion, while services exports that could be ICT-enabled totaled $520 billion. Digital trade is growing on a global basis, contributing more to global domestic product (GDP)GDP than financial or merchandise flows.

The increase in digital trade raises new challenges in U.S. trade policy, including how to best address new and emerging trade barriers. As with traditional trade barriers, digital trade constraints can be classified as tariff or nontariff barriers. In addition to high tariffs, barriers to digital trade may include localization requirements, cross border data flow limitations, intellectual property rights (IPR) infringement, forced technology transfer, web filtering, economic espionage, and cybercrime exposure or state-directed theft of trade secrets. China'’s policies, in particular, such as those on internet sovereignty and cybersecurity, particularly pose challenges for U.S. companies.

Digital trade issues often overlap and cut across policy areas, such as IPR and national security; this raises questions for Congress as it weighsintellectual property rights (IPR) and national security, raising complex questions for Congress on how to weigh different policy objectives. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) points out three potentially conflicting policy goals in the internet economy: (1) enabling the internet; (2) boosting or preserving competition within and outside the internet; and (3) protecting privacy and consumers, more generally.

While no multilateral agreement on digital trade exists in the World Trade Organization (WTO), othercertain WTO agreements cover some aspects of digital trade. Recent bilateral and plurilateral agreements have begun to address digital trade rules and barriers more explicitly. For example, the proposed U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and ongoing plurilateral discussions in the WTO on a potentialan e-commerce agreement could address digital trade barriers to varying degrees. Digital trade is also being discussed in a variety of international forumsOther international fora also are discussing digital trade, providing the United States with multiple opportunities to engage in and shape global norms.

With workers

With workers and firms in the high-tech sector in every U.S. state and congressional district, and with over two-thirds of U.S. jobs requiring digital skills, Congress has an interest in ensuring and developing the global rules and norms of the internet economy in line with U.S. laws and norms, and in establishing a U.S. trade policy on digital trade that advances U.S. interests.

Introduction

national interests

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 9 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 22 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 26 link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 30 link to page 32 link to page 33 link to page 34 link to page 36 link to page 37 link to page 42 link to page 43 link to page 44 link to page 44 link to page 44 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 46 link to page 47 link to page 48 link to page 49 link to page 50 link to page 51 link to page 52 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 13 link to page 29 Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Role of Digital Trade in the Economy ............................................................................................. 2

Economic Impact of Digital Trade ............................................................................................ 5

COVID-19 and Digital Trade ............................................................................................ 10 Digitization Challenges ...................................................................................................... 11

Digital Trade Policy and Barriers .................................................................................................. 12

Tariff and Tax Barriers ............................................................................................................ 14 Nontariff Barriers .................................................................................................................... 16

Localization Requirements ............................................................................................... 16 Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Infringement ............................................................... 18 National Standards and Burdensome Conformity Assessment ......................................... 20 Filtering, Blocking, and Net Neutrality ............................................................................ 21 Cybersecurity Risks .......................................................................................................... 22

U.S. Digital Trade with Key Trading Partners .............................................................................. 24

European Union ...................................................................................................................... 24

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) ................................................................... 25 The EU’s Digital Policy .................................................................................................... 26 New EU Copyright Rules ................................................................................................. 28 U.S.-EU Digital Cooperation ............................................................................................ 29

China ....................................................................................................................................... 30

“Cyber Sovereignty” and China’s Involvement in Global Internet Governance .............. 32 China’s Emerging Cyberspace and Data Protection Regime ............................................ 33 U.S. Efforts to Address Digital Trade Barriers and IP Theft Issues in China ................... 38

Digital Trade Provisions in Trade Agreements .............................................................................. 39

WTO Provisions ...................................................................................................................... 40

General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) ............................................................ 40 Declaration on Global Electronic Commerce ................................................................... 40 Information Technology Agreement (ITA) ....................................................................... 41 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) ............... 41 World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Internet Treaties ................................ 42 Current WTO Plurilateral Negotiations ............................................................................ 43

U.S. Bilateral and Plurilateral Agreements ............................................................................. 44

United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) ...................................................... 45 U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement ................................................................................ 46

Other International Forums for Digital Trade ......................................................................... 47

Issues for Congress ........................................................................................................................ 48

Figures Figure 1. Digital Economy Value Added by Component ................................................................ 3 Figure 2. U.S. Trade in ICT and Potentially ICT-Enabled Services, by Type of Service ................ 5 Figure 3. Cloud Computing Infrastructure Global Market Share .................................................... 9 Figure 4. Trans-Atlantic Digitally Enabled Services Trade Flows ................................................ 25

Congressional Research Service

link to page 35 link to page 54 Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

Tables Table 1. American Chamber of Commerce in China 2021 Business Survey ................................ 31

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 50

Congressional Research Service

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

Introduction The rapid growth of digital technologies in recent years has created new opportunities for U.S. consumers and businesses but also new challenges in international trade. For example, consumers today access e-commerce, social media, telemedicine, and other offerings not imagined thirty years ago. Businesses use advanced technology to reach new markets, track global supply chains, analyze big data, and create new products and services. New technologies facilitate economic activity but also create new trade policy questions and concerns. Data and data flows form a pillar of innovation and economic growth.

The "“digital economy"” accounted for 6.99.6% of U.S. GDP in 2017, gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019, including (1) the information and communications technologies (ICT) sector and underlying infrastructure, (2) business-to-business and business-to-consumer e‐commerce, and (3) priced digital services (e.g., internet cloud or intermediary services).1 The digital economy supported 7.7 U.S. million jobs, or 5.0% of total U.S. employment in 2019.2 One study found that the “tech-ecommerce ecosystem” added 1.4 million U.S. jobs between September 2017 and September 2021, and was the main job producer in 40 states.3infrastructure, (2) digital transactions or e‐commerce, and (3) digital content or media.1 The digital economy supported 5.1 million jobs, or 3.3% of total U.S. employment in 2017, and almost two-thirds of jobs created in the United States since 2010 required medium or advanced levels of digital skills.2 As digital information increases in importance in the U.S. economy, issues related to digital trade have become of growing interest to Congress.

While there is no globally accepted definition of digital trade, the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) broadly defines digital trade as follows:

:

The delivery of products and services over the Internetinternet by firms in any industry sector, and of associated products such as smartphones and Internet-connected sensors. While it of associated products such as smartphones and internet-connected sensors. While it includes provision of e-commerce platforms and related services, it excludes the value of sales of physical goods ordered online, as well as physical goods that have a sales of physical goods ordered online, as well as physical goods that have a digital counterpart (such as books, movies, music, and software sold on CDs or DVDs).3

4

A joint report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCED), World Trade Organization (WTO), and International Monetary Fund (IMF) defined digital trade more broadly as “all trade that is digitally ordered and/or digitally delivered.”5

The rules governing digital trade are evolving as governments across the globe experiment with different approaches and consider diverse policy priorities and objectives. Barriers to digital trade, such as infringement of intellectual property rights (IPR) or protectivedata localization requirements or protectionist industrial policies, often overlap and cut across sectors. In some cases, policymakers may struggle to balance digital trade objectives with other legitimate policy issues related to, such as national security and privacy. Digital trade policy issues have been in the spotlight recently, due in part to the rise of new trade barriers, heightened concerns over data privacy, the rise of misinformation and disinformation, and an increasing number of cybertheftcybersecurity incidents that have affected U.S. consumers and companies, companies, and government entities. These concerns may raise the general U.S. interest in promoting, or restricting,managing cross-border data flows and in, enforcing compliance with existing rules. Congress has an , and establishing new ones. Congress has an

1 These estimates exclude free digital services. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Updated Digital Economy Estimates – June 2021, June 2021. For more information, see https://www.bea.gov/data/special-topics/digital-economy.

2 Ibid. 3 Michael Mandel, “Tech-Ecommerce Drives Job Growth in Most States,” Progressive Policy Institute, October 18, 2021, at: https://www.progressivepolicy.org/blogs/tech-ecommerce-drives-job-growth-in-most-states/.

4 U.S. International Trade Commission, Global Digital Trade 1: Market Opportunities and Key Foreign Trade Restrictions, August 2017, p.33, at: https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4716.pdf.

5 OECD, WTO, IMF, Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade, Version 1, 2020, at: http://www.oecd.org/sdd/its/Handbook-on-Measuring-Digital-Trade-Version-1.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 7 Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

interest in ensuring the global rules and norms of the internet economy are in line with U.S. laws and norms.

and allow for fair global competition for U.S. businesses and workers.

Trade negotiators continue to explore ways to address evolving digital issues in trade agreements, including in the proposedUnited States’ newest agreements, the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement(USMCA). Congress has an important role in shaping digital trade policy, including oversight ofoverseeing agencies charged with regulating cross-border data flows, as part of trade negotiations, and in working with the executive branch to identify the right balance between digital trade and other policy objectives.

This report discusses the role of digital trade in the U.S. economy, barriers to digital trade, digital trade agreement provisions and negotiations, and other selected policy issues.

Role of Digital Trade in the U.S. and Global Economy

The internet is not only a facilitator ofEconomy The digital economy not only facilitates international trade in goods and services, but is itself a platform for new digitally-originated services. The internet is enabling technological shifts that are transforming businesses. The Group of Twenty (G-20) Digital Economy Task Force identified the digital economy as incorporating “all economic activity reliant on, or significantly enhanced by the use of digital inputs, including digital technologies, digital infrastructure, digital services and data. It refers to all producers and consumers, including government, that are utilizing these digital inputs in their economic activities.”6

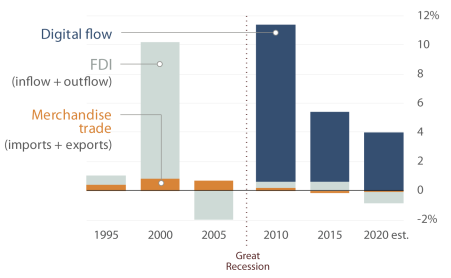

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) estimates that, from 2005 to 2019are transforming businesses. According to one estimate, the volume of global data flows (sending of digital data such as from streaming video, monitoring machine operations, sending communications) is growing faster than trade or financial flows. One analysis forecasts the global flows of goods, foreign direct investment (FDI), and digital data will add 3.1% to gross domestic product (GDP) from 2015-2020. The volume of global data flows is growing faster than trade or financial flows, and its positive GDP contribution offsets the lower growth rates of trade and FDI (see Figure 1).4 Focusing domestically, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) estimates that, from 1997-2017, real value added for the U.S. digital economy grew at an average annual rate of 5.2% per year, outpacing the 2.2% the digital economy outpaced overall growth in the overall economy each year.7 During that time, business-to-consumer e-commerce was the fastest growing component of the digital economy (see Figure 1).

The increase in the digital economy and digital trade parallels the growth in internet usage globally. According to one study, over half of the world’s population uses the internet.8 As of 2020, 93% of American adults use the internet, including 15% who only access the internet via smart phones.9 In the third quarter of 2021, approximately 48% of internet traffic in the United States came from mobile devices.10 Internet traffic is growing globally, with users making almost

6 OECD, “A Roadmap Toward a Common Framework for Measuring the Digital Economy for G20 Digital Economy Task Force,” Saudi Arabia, 2020, http://www.oecd.org/sti/roadmap-toward-a-common-framework-for-measuring-the-digital-economy.pdf?utm_source=Adestra&utm_medium=email&utm_content=A%20roadmap%20toward%20a%20common%20framework%20for%20measuring%20the%20Digital%20Economy%20-%20Read%20more&utm_campaign=Stats%20Flash%2C%20August%202020&utm_term=sdd.

7 U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Updated Digital Economy Estimates – June 2021, June 2021. For more information, see https://www.bea.gov/data/special-topics/digital-economy.

8 Internet World Stats, World Internet Usage and Population Statistics, as of December 31, 2020, at https://internetworldstats.com/stats.htm.

9 Pew Research Center, Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet, April 7, 2021, at https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/.

10 Statistica, “Percentage of mobile device website traffic in the United States from 1st quarter 2015 to 2nd quarter 2021,” September 30, 2021, at https://www.statista.com/statistics/683082/share-of-website-traffic-coming-from-mobile-devices-usa/.

Congressional Research Service

2

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

4.5 million Google searches each minute in 2019.11 In 2020, the global population is estimated to have generated 47 zettabytes of data – 534 million times the internet’s size in 1997.12

Figure 1. Digital Economy Value Added by Component

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, June 2021.

economy each year and, in 2017, the real value-added growth of the digital economy accounted for 25% of total real GDP growth.5

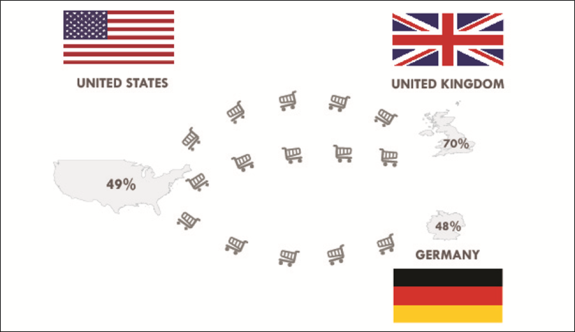

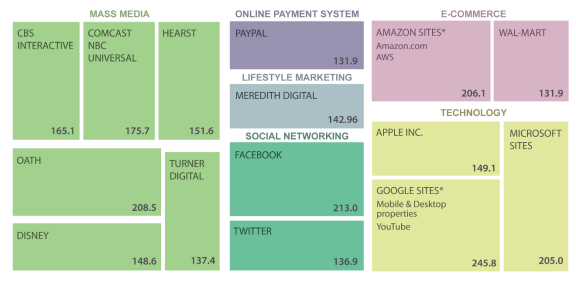

The increase in the digital economy and digital trade parallels the growth in internet usage globally. According to one study, over half of the world's population use the internet, including 95% of people in North America.6 As of 2017, 75% of U.S. households use wired internet access, but an increasing number rely on mobile internet access as the internet is integrated into people's everyday lives; 72% of U.S. adults own a smartphone.7 As of the end of 2018, approximately 40% of internet traffic in the United States came from mobile devices.8 Each day, companies and individuals across the United States depend on the internet to communicate and transmit data via various media and channels that continue to expand with new innovations (see Figure 2).

December 2018, Millions of unique U.S. visitors |

|

|

Source: Statistica.com. Note: * Examples of web properties owned by multinational companies. |

Cross-border data and communication flows are part of digital trade; they also facilitate trade and the flows of goods, services, people, and finance, which together are the drivers ofdrive globalization and interconnectedness. The highest levels reportedly are thosethe flows between the United States and Western Europe, Latin America, and China.13 Efforts to impede cross-border data flows could decrease efficiency and other potential benefits of digital trade.

Powering all these connections and data flows are underlying ICT.9 infrastructure.14 ICT spending is a large and growing component of the international economy and essential to digital trade and innovation. Worldinnovation. According to the United Nations, world trade in ICT physical goods grew to $2.3 trillion in 20172020, with U.S. ICT goods exports over $146totaling $138 billion.15 U.S. exports of ICT goods accounted for 8.7% of total U.S. goods exports in 2019.16

Semiconductors, a key component in many electronic devices, including systems that undergird U.S. technological competitiveness and national security, are a top U.S. ICT export. With major semiconductor manufacturing facilities in 18 states, the industry is estimated to employ almost a

11 Note: Google search is not available in all countries. OECD, “A Roadmap Toward a Common Framework for Measuring the Digital Economy for G20 Digital Economy Task Force,” Saudi Arabia, 2020, at https://www.oecd.org/sti/roadmap-toward-a-common-framework-for-measuring-the-digital-economy.pdf.

12 A zettabyte is one sextillion (1021) bytes. Digital Economy Compass 2019, Statista.com, at https://www.statista.com/study/52194/digital-economy-compass/.

13 James Manyika, et al., “Digital globalization: The new era of global flows,” McKinsey, Global Institute, February 16, 2016.

14 ICT is an umbrella term that includes any communication device or application, including radio, television, cellular phones, computer and network hardware and software, satellite systems, and associated services and applications.

15 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNTAC), UNCTADstat, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=15850.

16 World Bank, Table: ICT goods exports (% of total goods exports) - United States, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.ICTG.ZS.UN?locations=US.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 9 Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

quarter million U.S. workers.17 The U.S. semiconductor industry dominates many parts of the semiconductor supply chain, such as chip design, and it accounted for 48% (or $193 billion) of the global market of revenue as of 2020.18 Industry forecasts expect continued strong annual global sales growth of 19.7% in 2021 (to an estimated $527 billion) and a further 8.8% in 2022 (reaching $573 billion).19 The U.S. share of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity, however, has declined from 37% in 1990 to 12% in 2020.20 billion.10

Semiconductors, a key component in many electronic devices, are a top U.S. ICT export. Global sales of semiconductors were $468.8 billion in 2018, an increase of 6.81% over the prior year.11 U.S.-based firms have the largest global market share with 45% and accounted for 47.5% of the Chinese market. Given the importance of semiconductors to the digital economy and continued advances in innovation, countries such as China are seeking to grow their own semiconductor industry to lessen their dependence on U.S. exports.

ICT services are outpacing the growth of international trade inmany policymakers see U.S. strength in semiconductor technology and fabrication as vital to U.S. economic and national security interests and have raised concerns about the declining U.S. share in semiconductor manufacturing capacity. Some U.S. policymakers have also expressed concerns about China's state-led efforts to develop an indigenous vertically-integrated semiconductor industry, in part to lessen the country’s dependence on U.S. exports.21

The growth in traded ICT services is outpacing the growth of traded ICT goods. The OECD estimates that ICT services trade increased 40% from 2010 to 2016. 22 The United States is the fourth-largest OECDthird-largest exporter of ICT services, after Ireland, India, and the Netherlands.12 and India.23 ICT services include telecommunications and computer services, as well as charges for the use of intellectual property (e.g., licenses and rights). ICT-enabled services are those services with outputs delivered remotely over ICT networks, such as online banking or education. ICT services can augment the productivity and competitiveness of goods and services. U.S. ICT services are often inputs to final demand products that may be exported by other countries, such as China. U.S. exports of ICT services have grown almost every year since 2000 (see Figure 2).24 In 2020, U.S. In 2017, exports of ICT services grew to $7184 billion of U.S. exports, while exports of potentially ICT-enabled services totaled $520 while services exports that could be ICT-enabled were another $439 billion, demonstrating the impact of the internet and digital revolution.13

25

17 Semiconductor Industry Association, https://www.semiconductors.org/semiconductors-101/industry-impact/. 18 Semiconductor Industry Association, “Semiconductor Shortage Highlights Need to Strengthen U.S. Chip Manufacturing, Research,” February 4, 2021. 19 Semiconductor Industry Association, “Global Semiconductor Sales Increase 1.9% Month-to-Month in April; Annual Sales Projected to Increase 19.7% in 2021, 8.8% in 2021,” June 9, 2021.

20 Semiconductor Industry Association, “Invest in Domestic Semiconductor Manufacturing and Research,” https://www.semiconductors.org/chips/, accessed March 12, 2021.

21 See CRS Report R46581, Semiconductors: U.S. Industry, Global Competition, and Federal Policy, by Michaela D. Platzer, John F. Sargent Jr., and Karen M. Sutter, CRS Report R46767, China’s New Semiconductor Policies: Issues for Congress, by Karen M. Sutter, and Cheng Ting-Fang and Lauly Li, “US-China tech war: Beijing's secret chipmaking champions,” Nikkei Asia, May 5, 2021.

22 OECD (2017), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276284-en.

23 Nationmaster, Top Countries in Exports of ICT Services, https://www.nationmaster.com. 24 Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 3.1. U.S. Trade in ICT and Potentially ICT-Enabled Services, by Type of Service, June 30, 2020.

25 According to the Department of Commerce, potentially-ICT enabled services are those that “can predominantly be delivered remotely over ICT networks, a subset of which are actually delivered via that method” and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Table 3.1. U.S. Trade in ICT and Potentially ICT-Enabled Services, by Type of Service October 19, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

4

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

Figure 2. U.S. Trade in ICT and Potentially ICT-Enabled Services, by Type of Service

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, July 2021.

ICT and other online services depend on software; the value added to U.S. GDP from support services and software has increased over the past decade relative to that of telecommunications and hardware.1426 According to one estimate, software contributed more than $1.149 trillion to the total U.S. value added to GDP in 2016, an increase of 6.4% over 2014, and the U.S.GDP in 2020 and the software industry accounted for 2.93.3 million jobs directly in 2020, a 7.2% increase from 2018.27 According to an industry group, software and the software industry contributes to jobs in all 50 states, with the value-added GDP of the software industry growing more than 35% in Nevada and Washington from 2018 to 2020.28 The average salary of a software developer is over $114,000.29 In addition, the software industry claims that the sector funds 27% of all domestic research and development (R&D).30

directly in 2016.15 Internet-advertising, an industry that would not exist without ICT, generated an additional 10.4 million U.S. jobs.16

Economic Impact of Digital Trade

Economic Impact of Digital Trade As the internet and technology continue to develop rapidly, increasing digitization affects finance and data flows, as well as the movement of goods and people. Beyond simple communication, digital technologies can affect global trade flows in multiple ways and have broad economic impactimpact (see Figure 3). First, digital technology enables the creation of new goods and services, such as e-books, online education, or online banking services. Digital technologies may also add value by raising productivity and/or loweringraise productivity

26 BEA, Measuring the Digital Economy: An Update Incorporating Data from the 2018 Comprehensive Update of the Industry Economic Accounts, March 2018, p.9.

27 Ibid. 28 Software.org, “Software: Growing US Jobs and the GDP,” https://software.org/wp-content/uploads/2019SoftwareJobs.pdf.

29 Ibid. 30 Software.org, Software: Supporting US Through COVID, 2021, https://software.org/reports/software-supporting-us-through-covid-2021/.

Congressional Research Service

5

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

and/or lower the costs and barriers related to flows of traditional goods and services. For example, some refer to the application of emerging technologies as the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), as example, companies may rely on radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags forand blockchain for global supply chain tracking, 3-D printing based on data files, robotics for manufacturing, or devices or objects connected via the Internet of Things (see text boxIoT), and data analytics driven by artificial intelligence (AI) (see text box on key technology terms). In addition, digital platforms serve as intermediaries for multiple forms of digital trade, including e-commerce, social media, and cloud computing and allow businesses to reach customers around the globe. In these ways, digitization pervades every industry sector, creating challenges and opportunities for established and new players.

Key Technologies Driving Innovation

Artificial Intelligence (AI) can generally be thought of as computerized systems that work and react in ways commonly thought to require intelligence, such as solving complex problems in real-world situations.

Blockchain is a distributed record-keeping system (each user can keep a copy of the records) that provides for auditable transactions and secures those transactions with encryption. Using blockchain, each transaction is traceable to a user, each set of transactions is verifiable, and the data in the blockchain cannot be edited without each user’s knowledge. Compared to traditional technologies, blockchain allows two or more parties without a trusted relationship to engage in reliable transactions without relying on intermediaries or central authority (e.g., a bank or government).

Internet of Things (IoT) is a system of interrelated devices connected to a network and/or to one another, exchanging data without necessarily requiring human-to-machine interaction. In other words, IoT is a collection of electronic devices that can share information among themselves.

Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) is characterized by advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning, the Internet of Things, autonomous hardware and software robotics, and advanced data systems that enable real-time and predictive analytics.

Source: CRS In Focus IF10608, Overview of Artificial Intelligence, by Laurie A. Harris; CRS In Focus IF10810, Blockchain and International Trade, by Rachel F.

Fefer; CRS In Focus IF11239, The Internet of Things (IoT): An Overview, by Patricia Moloney Figliola, John Karr, et. al.; and COVID-19, 4IR, and the Future of

Work, APEC Policy Brief No. 34, June 2020.

In an international context, one source estimates that digitally-enabled trade in 2019 was worth $800 billion to $1.5 trillion (3.5%-6.0% of global trade).31 Furthermore, up to 70% of all global trade flows could “eventually be meaningfully affected by digitization.” One think tank categorizes these trade flows to include digitally-sold trade (e.g., e-commerce), digitally-enhanced trade (e.g., services such as movie streaming or car maintenance monitoring that complement physical goods), and digitally-native trade (e.g., non-fungible token (NFT) or cryptocurrency purchase of digital art or digital platforms).

opportunities for established and new players.

Looking at digital trade in an international context, approximately 12% of physical goods are traded via international e-commerce.17 Global e-commerce grew from $19.3 trillion in 2012 to $27.7 trillion in 2016, of which 86% was business-to-business (B2B).18 One source estimates that cross-border business-to-consumer (B2C) e-commerce sales will reach approximately $1 trillion by 2020.19

These estimates do not quantify the additional benefits of digitization uponfor business efficiency and productivity, or of increased customer and market access, which enable greater volumes of international trade for firms in all sectors of the economy. in all sectors of the economy. Technology advancements have helped drive efficiency and automation across diverse U.S. industries, but may raise other policy considerations, such as their impact on employment in the manufacturing sector. Digitization efficiencies have the potential to both increase international trade and decrease international tradecosts. For example, one analysis found that logistics optimization technologies could reduce shipping and customs processing times by 16% to 28%, boosting overall trade by 6% to 11% by 2030; at the same time, however, automation, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and 3-D printing could enable more local production, thereby reducing global trade by as much as 10% by 2030.20 The overall impact of digitization has yet to be seen.

One study coined the term "digital spillovers" to fully capture the digital economy and estimated the global digital economy, including such spillovers, was $11.5 trillion in 2016, or 15.5% of global GDP.21 Their analysis indicated that the long-term return on investment (ROI) for digital technologies is 6.7 times that of nondigital investments.22

.32 A

31 Christian Ketels, et al., “Global Trade Goes Digital,” Boston Consulting Group, August 12, 2019. 32 Susan Lund, et at., “Globalization in Transition: The Future of Trade and Value Chains,” McKinsey & Company, January 2019 Commercial Assistant - Open to: All Interested Applicants / All Sources

Congressional Research Service

6

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

study of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Asia found that digital tools reduced export costs by 82%, and transaction times by 29%.33

One example of digitization driving efficiencies is the use of AI to help companies forecast demand, understand trends and identify patterns, and allow companies to quickly adjust shipping routes or optimize supply chains when confronted with disruptions or unexpected events.34 For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Samsung noted that “we inserted COVID-specific information, such as closed stores and traffic changes due to the pandemic, into the AI tool to predict the demands more accurately in each region.”35 At the same time, automation, AI, and 3-D printing could enable more local production, thereby reducing global trade by as much as 10% by 2030.36

Blockchain is one emerging software technology some companies are using to increase efficiency and transparency and lower supply chain costs that depends on open data flows of digital trade.23 For example37 For example, it is helping services industries, such as insurance, become more efficient by utilizing smart contracts based on blockchain to respond real-time to customers’ claims or to streamline fraud mitigation processes.38 Another example is how, in an effort to streamline processes, save costs, and improve public health outcomes, Walmart and IBM built a blockchain platform to increase transparency of global supply chains and improve traceability for certain imported food products.2439 The initiative aims to expand to include several multinational food suppliers, farmers, and retailers and depends on connections via the Internet of ThingsIoT and open international data flows.

The work schedule for this position is: Full Time (40 hours per week) Start date: Candidate must be able to begin working within a reasonable period of time of receipt of agency authorization and/or clearances/certifications or their candidacy may end.

Salary:

(GBP) £54,805/Per Year

Series/Grade:

LE - 1510 - 7

Agency:

Embassy London

Position Info:

Location:

London, UK

Close Date:

(MM/DD/YYYY)

01/09/2022.

33 AlphaBeta, “Micro-Revolution: The New Stakeholders of Trade in APAC,” Asia Pacific MSME Trade Coalition, February 2018.

34 James Rundle, “Supply Chain Strains Sharpen Focus on AI,” The Wall Street Journal, March 31, 2021. 35 Edward White, “Companies try to cut geopolitical risk from supply chains,” The Financial Times, April 6, 2021. 36 Ibid. 37 For more on blockchain, see CRS Report R45116, Blockchain: Background and Policy Issues, by Chris Jaikaran. 38 Adelyn Zhou, “How Blockchain Smart Contracts Are Reinventing the Insurance Industry,” Nasdaq, January 29, 2021, and Gemini, “Blockchain and the Insurance Industry,” Cryptopedia, March 24, 2021. 39 Walmart, “Food Traceability Initiative Fresh Leafy Greens,” letter to suppliers, September 24, 2018, https://corporate.walmart.com/media-library/document/blockchain-supplier-letter-september-2018/_proxyDocument?id=00000166-088d-dc77-a7ff-4dff689f0001.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 13 Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

According to one global estimate, there are 26 billion internet-connected vehicles, industrial equipment and household items that could transmit data for companies and government to analyze to improve processes and outcomes, whether efficiency or consumer welfare.40 Software drives these connected products, merging the physical and digital world and facilitating the delivery of new global services embedded in products. The overall and long-term impact of digitization has yet to be seen. One think tank estimates that 60% of global GDP will be digitized by 2022, with growth in every industry driven by data flows and digital technology.41

data flows. With increased applications, the Internet of Things may have a global economic impact of as much as $11.1 trillion per year, according to one study.25

|

Key Emerging Technologies Internet of Things (IoT) "encompass(es) all devices and objects whose state can be read or altered via the internet, with or without the active involvement of individuals.... The internet of things consists of a series of components of equal importance—machine-to-machine communication, cloud computing, big data analysis, and sensors and actuators. Their combination, however, engenders machine learning, remote control, and eventually autonomous machines and systems, which will learn to adapt and optimise themselves."26 Blockchain "is a distributed record-keeping system (each user can keep a copy of the records) that provides for auditable transactions and secures those transactions with encryption. Using blockchain, each transaction is traceable to a user, each set of transactions is verifiable, and the data in the blockchain cannot be edited without each user's knowledge. Compared to traditional technologies, blockchain allows two or more parties without a trusted relationship to engage in reliable transactions without relying on intermediaries or central authority (e.g., a bank or government)."27 Artificial Intelligence (AI) "AI can generally be thought of as computerized systems that work and react in ways commonly thought to require intelligence, such as solving complex problems in real-world situations."28 |

Because of its ubiquity, the benefits and economic impact of digitization are not restricted to certain geographic areas, and businesses and communities in every U.S. state feel the impact of digitizationdigitization, as new business models and jobs are created and existing ones disrupted.29are disrupted.42 For example, a small business that uses accounting software may no longer need to employ a bookkeeper, while a neighborhood store may confront new competition from online sellers based in other countries, but also develop its own online sales channel. One study found that the more intensively a company uses the internet, the greater the productivity gain. The increase in internet usage is also associated with increased value and diversity of products being sold.30

The internet, and cloud services specifically, has43

One driver of the diffusion of the benefits of the internet and digitization has been cloud computing. Cloud services have been called the great equalizer, since it allowsthey generally allow small companies access to the same information and the same computing power as large firms using a flexible, scalable, and on-demand model. For example, Thomas Publishing Co., a U.S. mid-sized, private, family-owned and -operated business, is transporting data from its own computer servers to data centers run by Amazon.com Inc.31 Digital platforms can minimize costs and enable small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)In 2020, the global cloud computing market was estimated to be worth $130 billion annually—dominated by U.S. and Chinese firms, with Amazon Web Services (AWS) as the world’s largest supplier (see Figure 3).44

40 Hosuk Lee-Makiyama and Kimberley Botwright, “5 ways to ensure trust when moving data across borders,” World Economic Forum, April 13, 2021.

41 Frank Gens, et al., “IDC FutureScape: Worldwide IT Industry 2019 Predictions,” October 2018. 42 John Wu, Adams Nager, and Joseph Chuzhin, High-Tech Nation: How Technological Innovation Shapes America’s 435 Congressional Districts, ITIF, November 28, 2016, p. 4, https://itif.org/publications/2016/11/28/technation.

43 The World Bank Group, World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends, 2016, http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2016.

44 Synergy Research Group, “Race for the Cloud,” Politico, April 22, 2021.

Congressional Research Service

8

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

Figure 3. Cloud Computing Infrastructure Global Market Share

As of end 2020

Source: Synergy Research Group, “Cloud Market Ends 2020 on a High while Microsoft Continues to Gain Ground on Amazon,” February 2, 2021.

Digital platforms can minimize costs and enable SMEs to grow through extended reach to customers or suppliers or by integrating into a global value chain (GVC). More than 50% of businesses globally rely on data flows for cloud computing (see text box).32

chains (GVCs). For example, Amazon notes that hundreds of thousands of SMEs launch and scale their businesses using AWS and that SMEs selling on Amazon.com have created an estimated 1.1 million jobs.45 Netflix, a U.S. firm offering online streaming services, earned more revenue from international markets than from the U.S. domestic market in the first quarter of 2021.46

Digitization of customs and border control mechanisms also helpsmay help simplify and speed delivery of goods to customers. Regulators are looking to blockchain technology to improve efficiency in managing and sharing data for functions such as border control and customs processing of international shipments.3347 With simpler border and customs processes, more firms are able to conduct business in global markets (or are more willing to do so). A study of U.S. SMEs on the e-commerce platform eBay found that 97% export, while that number is a full 100% in countries as diverse as Peru and Ukraine.34 Netflix, a U.S. firm offering online streaming services, increased its international revenue from $4 million in 2010 to more than $5 billion in 2017.35

|

A Local Manufacturer Grows Through Digital Trade Kirk Anton and Tricia Hudson launched their business in 2010 as a one-stop shop for heat transfer materials, importing heat-applied materials and creating customized products for clients. The company moved online and converted to completely digital in 2013, using services such as Google Analytics to inform their marketing campaigns. Growing by more than 70% over four years, in 2017 the company employed forty people in Florida, Kentucky, Nevada, and North Dakota, and boasted over 85,000 customers across the globe.36 |

96% export to an average of 17 foreign countries.48 Digital trade facilitation (e.g., digitizing customs, legal documents, and supply chain finance) has gained prominence on the international trade agenda, as policymakers and businesses seek to enable export opportunities for SMEs.

45 Amazon, 2020 Amazon SMB Impact Report, https://assets.aboutamazon.com/4d/8a/3831c73e4cf484def7a5a8e0d684/amazon-2020-smb-report.pdf.

46 Netflix, Streaming Revenue and Membership Information by Region, Netflix First Quarter 2021 Earnings Interview, https://ir.netflix.net/ir-overview/profile/default.aspx.

47 Commercial Customs Operations Advisory Committee (COAC), Trade Progress Report, November 2017, https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2017-Nov/Global%20Supply%20Chain%20Subcommittee%20Trade%20Executive%20Summary%20Nov%202017.pdf.

48 Cathy Foster, “eBay’s 2020 U.S. Small Online Business Report: How We’re Creating Economic Opportunity,” July 16, 2020, https://www.ebayinc.com/stories/news/ebays-2020-u-s-small-online-business-report-how-were-creating-economic-opportunity/.

Congressional Research Service

9

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

A similar argument has been made for firms and governments in low- and middle-income countries who can take advantage of the power of the internet to foster economic development. According to one official of In the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC), technology has enabled SMEs to open in new sectors such as ride-sharing and online order delivery services, and provides them with a "bigger, better opportunity to grow and learn that to join a global value chain."37 Another(APEC) region, which includes the United States, for example, SMEs account for over 97% of all business and employ over half of the workforce.49 Recognizing the importance of digitization, APEC officials agreed to focus on initiatives to develop the digital potential of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), including women-owned businesses.50 A 2011 study of SMEs estimated that the internet is a net creator of jobs, with 2.6 jobs created for every job that may be displaced by internet technologies; companies that use the internet intensively effectively doubled the average number of jobs.38 However, the costs of digital trade can be concentrated on particular sectors (see next section).

Digitization Challenges

The U.S. digital economy supported 3.3% of total U.S. employment in 2017, and those jobs earned approximately one and a half times the average annual worker compensation of the overall U.S. economy, making them attractive source for future growth.39 Software, and the software industry, contributes to the GDP in all 50 states, with the value-added GDP of the software industry growing more than 40% in Idaho and North Carolina.40 Industries, such as media and firms in urban centers, account for a larger share of the benefits. Many in business and research communities are only beginning to understand how to take advantage of the vast amounts of data being collected every day.

However, sources of "e-friction" or obstacles can prevent consumers, companies, and countries from realizing the full benefits of the online economy.41 Causes of e-friction can fall into four categories: infrastructure, industry, individual, and information. Government policy can influence e-friction, from investment in infrastructure and education to regulation and online content filtering. According to some experts, economies with lower amounts of e-friction may be associated with larger digital economies.42

While there are numerous positive digital dividends, there are also possible negative and uneven results across populations, such as the displacement of unskilled workers, an imbalance between companies with and without internet access, and the potential for some to use the internet to establish monopolies.43 51 As technology has evolved since 2011, the job impact may be greater today, but the benefits and costs of digitization and digital trade can vary across sectors.

COVID-19 and Digital Trade

When the COVID-19 pandemic began in early 2020, services trade declined across the globe, with tourism (the top U.S. cross-border services export), transport, and distribution impacted the most.52 Despite the overall decline, digital trade in services, including online retail, health, education, audio-visual services, and telecommunications, saw some significant gains as consumers and workers stayed home. The WTO noted the global shift to digital services, stating that “consumers are adopting new habits that may contribute to a long-term shift towards online services.”53 Governments have helped enable the transition through new permanent and temporary measures, such as allowing for medical consultations online, demonstrating the importance of digital trade.54 Software and digital connections also allowed the shift to telework (or remote work) for many employees accustomed to working in a busy office or traveling domestically or abroad to meet customers or suppliers in person. However, gains from digitization did not fully compensate for the decline in trade as the WTO noted that total global trade in services was down by a 21% in 2020, compared to 2019.55

Just as the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the shift to online provision of services, it also pushed companies to adopt new Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) technologies, such as robotics and automation. According to one study, 40% of companies worldwide are increasing their use of automation as a response to the pandemic and restrictions, such as social distancing guidelines.56 For example, one grocery chain in the Netherlands is developing robotics and AI for use in store operations to place and remove products.57

49 Https://www.apec.org/Groups/SOM-Steering-Committee-on-Economic-and-Technical-Cooperation/Working-Groups/Small-and-Medium-Enterprises.

50 2020 APEC SME Ministerial Statement, “Navigating the New Normal: Restarting and Reviving MSMEs through Digitalisation, Innovation and Technology, October 23, 2020.

51 Matthieu Pélissié du Rausas, James Manyika, and Eric Hazan et al., Internet matters: The Net’s sweeping impact on growth, jobs, and prosperity, McKinsey Global Institute, May 2011, p. 21, http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/high-tech/our-insights/internet-matters.

52 WTO, “Trade in Services in the Context of COVID-19,” May 28, 2020. 53 Ibid. 54 For more information and examples see, WTO, COVID-19: Measures affecting trade in services, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/trade_related_services_measure_e.htm.

55 WTO, “Services trade slump persists as travel wanes; other service sectors post diverse gains,” July 23, 2021. 56 Angus Loten, “Tech Workers Fear Their Jobs Will Be Automated in Wake of Coronavirus,” The Wall Street Journal, May 27, 2020.

57 Catherine Stupp, “Ahold Delhaize Accelerates Automation as Coronavirus Pressures Workforce,” The Wall Street

Congressional Research Service

10

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

The growth in online services and automation created increased demand for the ICT goods that enable such shifts (e.g., laptops for e-learning and telework), leading to a surge in semiconductor demand, which outstripped supply.58 Auto plants in particular were hit hard, after the industry initially lowered their purchases of semiconductors during initial pandemic lockdowns, reflecting lower customer demand for autos. When demand began to grow as countries opened up, automakers around the world found themselves without needed components, leading many to decrease or stop auto production altogether.59 Many U.S. policymakers and other observers have called for increased investment in semiconductor manufacturing to power the shift online and to further digital advancements.60

The pandemic further underscored ongoing digital challenges in the United States and across the world. For example, mitigation efforts, such as the switch to online shopping, education, and telemedicine, revealed discrepancies in broadband availability and accessibility—termed the digital divide—across the United States.61

Digitization Challenges

The importance of digitization to the U.S. economy is expected to grow. Many in business and research communities are only beginning to understand how to take advantage of the vast amounts of data being collected every day, one important aspect of the digital economy. One study estimates companies are using 32% of data available to them to create value.62

While new technologies and new business models present opportunities to enhance efficiency and expand revenues, innovate faster, develop new markets, and achieve other benefits, new challenges also arise with the disruption of supply chains, labor markets, and some industries. For example, one study found a mismatch between workforce skills and job openings such as in Nashville, TN, which has an abundance of workers with music production and radio broadcasting skills but a scarcity of workers with IT infrastructure, systems management, and web programming skills.44 Another source notes over 11,000 open computing jobs in Michigan, with average salaries of over $80,000.45

The World Bank identified policy areas to try to ensure, and maintain, the potential benefits of digitization. Policy areas include establishing a favorable and competitive business climate, developing strong human capital, ensuring good governance, investing to improve both physical and digital infrastructure, and raising digital literacy skills. According to the World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Index 4.0, the United States is ranked at the top with a score of 85.6% compared to the global median score of 60%.46 The study identifies the key drivers of productivity as human capital, innovation, resilience, and agility, noting that future productivity depends not only on investment in technology but investment in digital skills. While the United States is considered a "super innovator," the report also notes "indications of a weakening social fabric … and worsening security situation … as well as relatively low checks and balances, judicial independence, and transparency."47

With the rapid pace of technology innovation, more jobs may become automated, with digital skills becoming a foundation for economic growth for individual workers, companies, and national GDP.48 Over two-thirds of U.S. jobs created since 2010 require some level of digital skills.49 The OECD found that generic ICT skills are insufficient among a significant percentage of the global workforce and few countries have adopted comprehensive ICT skills strategies to help workers adapt to changing jobs.50

Digital Trade Policy and Barriers

Policies that affect digitization in any one country's economy can have consequences beyond its borders, and because the internet is a global "network of networks," the state of a country's digital economy can have global ramifications. Protectionist policies may erect barriers A 2020 study found that, in the United States and United Kingdom, almost 20% of jobs are in ICT-intensive occupations, highlighting the importance of a digitally-skilled workforce.63 Another found a mismatch between workforce skills and job openings—67% of new U.S. science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) jobs are in computing whereas 11% of STEM degrees are in computer science.64

With the rapid pace of technology innovation, more jobs may become automated, with digital skills becoming a foundation for economic growth for individual workers, companies, and

Journal Pro, May 15, 2020.

58 Falan Yinug, “Semiconductor Shortage Highlights Need to Strengthen U.S. Chip Manufacturing, Research,” Semiconductor Industry Association, February 4, 2021.

59 Mike Colias, “GM to Halt Production at Several North American Plants Due to Chip Shortage,” The Wall Street Journal, April 8, 2021. For more information on semiconductors, see CRS Report R46581, Semiconductors: U.S. Industry, Global Competition, and Federal Policy, by Michaela D. Platzer, John F. Sargent Jr., and Karen M. Sutter.

60 See CRS Report R46581, Semiconductors: U.S. Industry, Global Competition, and Federal Policy, by Michaela D. Platzer, John F. Sargent Jr., and Karen M. Sutter.

61 For more information on the U.S. digital divide and COVID-19, see CRS Insight IN11239, COVID-19 and Broadband: Potential Implications for the Digital Divide, by Colby Leigh Rachfal.

62 Seagate, “Rethink Data: Put More of Your Business Data to Work – From Edge to Cloud,” July 2020, https://www.seagate.com/files/www-content/our-story/rethink-data/files/Rethink_Data_Report_2020.pdf.

63 OECD, “A Roadmap Toward a Common Framework for Measuring the Digital Economy for G20 Digital Economy Task Force,” Saudi Arabia, 2020, https://www.oecd.org/sti/roadmap-toward-a-common-framework-for-measuring-the-digital-economy.pdf.

64 STEM stands for Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Computer Science Education Stats, https://code.org/promote.

Congressional Research Service

11

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

national GDP.65 An OECD survey found that most countries, except the United States, have federal policies to promote the use of digital technologies by businesses.66 A separate OECD study found that, in general, SMEs tend to lag in some areas of digitization.67 The report includes policy recommendations, such as government investments in awareness campaigns and technology training, as well as the development of SME-tailored digital solutions. 68

The World Bank identified policy areas to try to ensure, and maintain, the potential benefits of the digital economy.69 These policy areas include establishing a favorable and competitive business climate, developing strong human capital, ensuring good governance, investing to improve both physical and digital infrastructure, and raising digital literacy skills. Some countries have established national digital strategies (NDSs) to help governments shape the way digital transformation takes place in a country that define policy priorities, set objectives and outline actions for implementation.70 Although the United States lacks an overarching digital strategy, according to the World Economic Forum’s 2020 Global Competitiveness Report, the United States is ranked number one for “digital legal framework” (the U.S. legal framework is able to adapt to digital business models), but it is not in the top ten countries for “digital skills” (a high percentage of the U.S. workforce may not be able to adapt to digitization due to a lack of digital skills).71

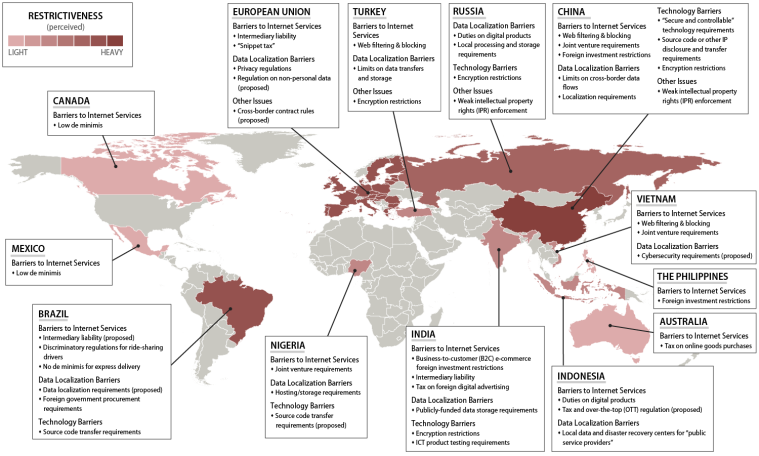

Digital Trade Policy and Barriers Policies that affect digitization in any one country’s economy can have consequences beyond its borders. Because the internet is a global “network of networks,” the state of a country’s digital economy also can have global ramifications. Protectionist policies may erect barriers and create discriminatory practices to digital trade, or damage trust in the underlying digital economy, and can result in the fracturing, or so-called balkanization, of the internet, lessening any economic gains.72gains. What some policymakers see as protectionist, however, others may view as necessary to protect domestic interests. For examples of the types of digital trade barriers that are in place around the globe, please see Appendix.

Despite common core principles, such as protecting citizen'scitizens’ privacy and expanding economic growth, many governments face multiple challenges in designing policies around digital trade. The OECD points out three potentially conflicting policy goals in the internetdigital economy: (1)

65 The World Bank Group, World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends, 2016, http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2016.

66 OECD (2020), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bb167041-en.

67 OECD (2021), The Digital Transformation of SMEs, OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bdb9256a-en.

68 Ibid. 69 The World Bank Group, World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends, 2016, http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2016.

70 OECD (2020), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bb167041-en.

71 World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report Special Edition 2020: How Countries are Performing on the Road to Recovery, December 16, 2020.

72 For example see, A. Michael Spence, “Preventing the Balkanization of the Internet,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 28, 2018, or Keith Wright, “The ‘splinternet’ is already here,” TechCrunch, March 3, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

12

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

economy: (1) enabling the internet; (2) boosting or preserving competition within and outside the internet; and (3) protecting privacy and consumers more generally.51

73

Ensuring a free the free flow of information and open internet is a stated policy priority for the U.S. government.52and defending freedom of online expression are longstanding U.S. policy priorities.74 Like other cross-cutting policy areas, such as cybersecurity or privacy, no one federal entity has policy primacy on all aspectsin every area of digital trade, and the United States has taken a sectoral approach to regulating digitization. According to an OECD study, the United States is the only OECD country that uses a decentralized, market-driven approach for a digital strategy, rather than having an overarching national digital strategy, agenda, or program.75

The executive branch advocates for U.S. digital priorities and noted many of them, such as working with allies to counter digital authoritarianism and establish international rules for emerging technologies, in its National Security Strategy report.76 Federal agencies identify and challenge foreign trade barriers through trade negotiations. The Department of Commerce works to promote U.S. digital trade policies domestically and abroad. Commerce’s digital attaché program under its foreign commercial service helps U.S. businesses navigate regulatory issues and overcome trade barriers to e-commerce exports in key markets.77

The U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), a Cabinet-level official in the Executive Office of the President, is the President’s principal advisor on trade policy, chief U.S. trade negotiator, and head of the interagency trade policy coordinating process. In describing the Biden Administration’s worker-centric digital trade policy, USTR Katherine Tai stated that “our efforts to formulate and pursue digital trade policies should, therefore, begin with a high level of ambition to be holistic and inclusive,” and that “digital trade policy must be grounded in how it affects our people and our workers.”78 She explained that in defining the Administration’s digital trade policy, USTR is asking “big and consequential questions,” including on the linkage with national security, domestic, and foreign policy interests; how best to work with allies; and how to balance the right of governments to regulate with the need for international trade rules.79

In passing Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) in 2015, Congress set negotiating objectives for USTR to pursue in trade negotiations, including related to digital trade (see text box).

73 Koske, I. et al. (2014), “The Internet Economy—Regulatory Challenges and Practices,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1171, OECD Publishing, Paris. DOI, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jxszm7x2qmr-en.

74 Https://www.state.gov/world-press-freedom-day/. 75 OECD (2017), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, p. 34, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276284-en.

76 The White House, Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, March 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf.

77 For more information, see https://www.export.gov/digital-attache. 78 U.S. Trade Representative, Remarks of Ambassador Katherine Tai on Digital Trade at the Georgetown University Law Center Virtual Conference, November 3, 2021.

79 Ibid.

Congressional Research Service

13

link to page 44 Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

or program.53

|

Protect a Free and Open Internet54 Protecting a free and open internet is a policy priority as stated in President Trump's 2017 National Security Strategy. "The United States will advocate for open, interoperable communications, with minimal barriers to the global exchange of information and services. The United States will promote the free flow of data and protect its interests through active engagement in key organizations, such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), the UN, and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU)." |

The Department of Commerce works to promote U.S. digital trade policies domestically and abroad. In 2015, Commerce launched a Digital Economy Agenda that identifies four pillars:55

- 1. "Promoting a free and open Internet worldwide, because the Internet functions best for our businesses and workers when data and services can flow unimpeded across borders";

- 2. "Promoting trust online, because security and privacy are essential if electronic commerce is to flourish";

- 3. "Ensuring access for workers, families, and companies, because fast broadband networks are essential to economic success in the 21st century"; and

- 4. "Promoting innovation, through smart intellectual property rules and by advancing the next generation of exciting new technologies."

Commerce's digital attaché program under the foreign commercial service helps U.S. businesses navigate regulatory issues and overcome trade barriers to e-commerce exports in key markets.56

The Administration also works to promote U.S. digital priorities by identifying and challenging foreign trade barriers and through trade negotiations. As with traditional trade barriers, digital trade constraints can be classified as tariff or nontariff barriers. Tariff barriers may be imposed on imported goods used to create ICT infrastructure that make digital trade possible or on the products that allow users to connect, while nontariff barriers, such as discriminatory regulations or local content rules, can block or limit different aspects of digital trade. Often, such barriers are intended to protect domestic producers and suppliers. Some estimates indicate that removing foreign barriers to digital trade could increase annual U.S. real GDP by 0.1%-0.3% ($16.7 billion-$41.4 billion), increase U.S. wages up to 1.4%, and add up to 400,000 U.S. jobs in certain digitally intensive industries.57

2015 U.S. Digital Trade Negotiating Objectives 2015 U.S. Digital Trade Negotiating Objectives

Congress enhanced its digital trade policy objectives for U.S. trade negotiations in the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-26), or Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), signed into law in June 2015.

|

Tariff Barriers

Historically, trade policymakers focused on overt trade barriers such as tariffs on products entering countries from abroad

Other negotiating objectives in TPA had implications for digital trade. For instance, objectives related to intellectual property rights (IPR) included ensuring that “rightsholders have the legal and technological means to control the use of their works through the Internet and other global communications media, and to prevent the unauthorized use of their works” and “providing strong protection for new and emerging technologies and new methods of transmitting and distributing products embodying intellectual property, including in a manner that facilitates legitimate digital trade.” TPA expired on July 1, 2021. Should Congress consider new TPA legislation, an issue that it may confront is whether to expand or amend the digital trade negotiating priorities. See CRS In Focus IF10038, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), by Ian F. Fergusson, and CRS Report RL33743, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and the Role of Congress

in Trade Policy, by Ian F. Fergusson.

As with traditional trade barriers, digital trade constraints can be classified as tariff or nontariff barriers. Tariff barriers may increase the cost of imported goods used to create ICT infrastructure that make digital trade possible or on the products that allow users to connect, while nontariff barriers, such as discriminatory regulations or local content rules, can block or limit different aspects of digital trade. Such barriers may be intended to shield domestic producers and suppliers, safeguard national security, or protect consumer safety.

Tariff and Tax Barriers Historically, trade policymakers focused on addressing overt trade barriers, such as tariffs or quotas for imported products. Tariffs at the border impact goods trade by raising the prices of products for producers or end customers, if tariff costs are passed down, thus limiting market access for U.S. exporters selling products, including ICT goods. Quotas may limit the number or value of foreign goods, persons, suppliers, or investments allowed in a market. Since 1998, WTO countries have agreed to not impose customs duties on electronic transmissions covering both goods (such as e-books and music downloads) and services.

80 Whether the moratorium will be continued after its current expiration after the upcoming Ministerial meeting or made permanent is subject to debate in the WTO (see “Declaration on Global Electronic Commerce” below).

While the United States is a major exporter and importer of ICT goods, tariffs are not levied on many of the products due to commitments in U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) WTO Information Technology Agreement (see belowITA). Tariffs may still serve as trade barriers for those countries or products not covered by existing FTAs or the WTO ITA.

80 The Geneva Ministerial Declaration on global electronic commerce, WT/MIN(98)/DEC/2, May 25, 1998.

Congressional Research Service

14

Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy

Digital Tariff and Tax Barriers: Selected Examples

An Indonesian regulation placed software and other digital products transmitted electronically, including applications, software, video, and audio, on its tariff schedule. Although the tariffs are currently set to zero, U.S. companies are raising concerns about potential tariffs and administrative burdens, including customs documentation.81

In Bangladesh, foreign satellite television service and social media suppliers must pay a 15% VAT and open local offices or appoint local representatives to facilitate tax collection.

The Mexican government has the power to order local Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to block access to electronically delivered services from foreign service suppliers who do not comply with Mexican VAT rules.

Source: U.S. Trade Representative, 2021 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers, March 31, 2021, p. 282, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/reports/2021/2021NTE.pdf

More recently, noting the growth of the digital economy, some countries, particularly in Europe and Asia, have proposed, announced, or implemented unilateral digital services taxes (DSTs) on the gross revenues earned by multinational corporations (MNCs) active in the digital economy. For example, France enacted a DST that applies a 3% levy on gross revenues derived from two digital activities of which French “users” are deemed to play a major role in value creation. Some countries have argued that such DSTs can serve as a market access barriers. USTR concluded that France's DST discriminates against major U.S. digital companies and is inconsistent with prevailing international tax policy principles.82

In June 2021, the United States and more than 130 countries agreed to update the global tax system and develop an international digital tax framework at the OECD. In support of the G-20/OECD Inclusive Framework negotiations, in June 2021, the United States and other G-7 countries announced agreement on (1) how to allocate taxing rights of the largest and most profitable multinational enterprises, including digital companies, and (2) a global minimum tax.83 In October, the United States reached a compromise— the “Agreement on DSTs”—with several European countries to withdraw their national DSTs once the multilateral deal goes into effect and to credit companies with any excess taxes paid. As part of it, the United States agreed to terminate the currently-suspended Section 301 trade actions against Austria, France Italy, Spain, and the UK.84 The United States reached a similar agreements with Turkey and India in November.85 The USTR, in coordination with the U.S. Department of the Treasury, is to monitor the implementation of the agreement.

81 U.S. Trade Representative, 2021 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers, March 31, 2021, p. 282, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/reports/2021/2021NTE.pdft.

82 For more information on the USTR investigations, see CRS In Focus IF11564, Section 301 Investigations: Foreign Digital Services Taxes (DSTs), by Andres B. Schwarzenberg.