Management of the Colorado River: Water Allocations, Drought, and the Federal Role

Changes from March 21, 2019 to May 17, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Management of the Colorado River: Water Allocations, Drought, and the Federal Role

Contents

- Introduction

- The Law of the River: Foundational Documents and Programs

- Colorado River Compact

- Boulder Canyon Project Act

- Arizona Ratification and Arizona v. California Decision

- 1944 U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty

- Upper Basin Compact and Colorado River Storage Project Authorizations

- Water Storage and Operations

- Annual Operating Plans

- Mitigating the Environmental Effects of Colorado River Basin Development

- Salinity Control

- Endangered Species Efforts and Habitat Improvements

- Upper Colorado Endangered Fish Recovery Program

- San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program

- Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program

- Lower Colorado Multi-Species Conservation Program (MSCP)

- Tribal Water Rights

- Drought and the Supply/Demand Imbalance in the Colorado River Basin

- 2012 Reclamation Study

- Developments and Agreements Since 2000

- 2003 Quantitative Settlement Agreement

- 2004 Arizona Water Settlements Act

- 2007 Interim Guidelines/Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead

- Pilot System Conservation Program

- Minute 319 and Minute 323 Agreements with Mexico

Proposed2019 Drought Contingency Plans- Upper Basin Drought Contingency Plan

- Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan

- Drought Contingency Plan

ApprovalOpposition

- Issues for Congress

- Funding and Oversight of Existing Facilities and Programs

- Indian Water Rights Settlements and Plans for New and Augmented Water Storage

- Drought Contingency

PlansPlan Implementation

Figures

Summary

The Colorado River Basin covers more than 246,000 square miles in seven U.S. states (Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California) and Mexico. Pursuant to federal law, the Bureau of Reclamation (part of the Department of the Interior) manages much of the basin's water supplies. Colorado River water is used primarily for agricultural irrigation and municipal and industrial (M&I) uses, but it also is important for power production, fish and wildlife, and recreational uses.

In recent years, consumptive uses of Colorado River water have exceeded natural flows. This causes an imbalance in the basin's available supplies and competing demands. A drought in the basin dating to 2000 has raised the prospect of water delivery curtailments and decreased hydropower production, among other things. In the future, observers expect that increasing demand for supplies, coupled with the effects of climate change, will further increase the strain on the basin's limited water supplies.

River Management

The Law of the River is the commonly used shorthand for the multiple laws, court decisions, and other documents governing Colorado River operations. The foundational document of the Law of the River is the Colorado River Compact of 1922. Pursuant to the compact, the basin states established a framework to apportion the water supplies between the Upper and Lower Basins of the Colorado River, with the dividing line between the two basins at Lee Ferry, AZ (near the Utah border). The Upper and Lower Basins each were allocated 7.5 million acre-feet (mafMAF) annually under the Colorado River Compact; an additional 1.5 mafMAF in annual flows was made available to Mexico under a 1944 treaty. Future agreements and court decisions addressed numerous other issues (including intrastate allocations of flows), and subsequent federal legislation provided authority and funding for federal facilities that allowed users to develop their allocations. A Supreme Court ruling also confirmed that Congress designated the Secretary of the Interior as the water master for the Lower Basin, a role in which the federal government manages the delivery of all water below Hoover Dam.

Reclamation and basin stakeholders closely track the status of two large reservoirs—Lake Powell in the Upper Basin and Lake Mead in the Lower Basin—as an indicator of basin storage conditions. Under recent guidelines, dam releases from these facilities are tied to specific water storage levels. For Lake Mead, the first tier of "shortage," under which Arizona's and Nevada's allocations would be decreased, would be triggered if Lake Mead's January 1 elevation is expected to fall below 1,075 feet above mean sea level. As of early 2019, Reclamation projected that there is an almost 70was a 69% chance of a shortage condition at Lake Mead beginning in 2020; there iswas also a lesser chance of Lake Powell reaching critically low levels in the next five years.

Drought Contingency Plans

Drought Contingency PlansDespite previous efforts to alleviate shortages in the basin, the possibility of water delivery curtailments for basin users has increased. After several years of negotiations, Reclamation and the basin states in 2019 announced finalized drought contingency plans (DCPs) for the Upper and Lower Basins. These plans would commit states to water supply cutbacks tied to reservoir storage levels (i.e., cutbacks in excess of previous cutback commitments), among other things. Federal implementation of the agreements also requires congressional authorization, and the basin states have requested that Congress authorize the agreements by April 22, 2019. If the DCPs are not finalized, then DOI may implement additional curtailments outside of the framework of those plans. Improved hydrology in early 2019 may decrease the chances of shortage in the immediate future.

Congressional Role

Congress plays a multifaceted role in federal management of the Colorado River basin. Congress funds and oversees management of basin facilities, including operations and programs to protect and restore endangered species. It also hashas also enacted and continues to consider Indian water rights settlements involving Colorado River waters and development of new water storage facilities in the basin. In addition, Congress has authorized and approved funding to mitigate water shortages and conserve basin water supplies and has considered enactingenacted new authorities to combat drought and its effects on basin water users (i.e., the DCPs and other related efforts).

Introduction

From its headwaters in Colorado and Wyoming to its terminus in the Gulf of California, the Colorado River Basin covers more than 246,000 square miles.1 The river runs through seven U.S. states (Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California) and Mexico. Pursuant to federal law, the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation, part of the Department of the Interior [DOI]) plays a prominent role in the management of the basin's waters. In the Lower Basin (i.e., Arizona, Nevada, and California), Reclamation also serves as water master on behalf of the Secretary of the Interior, a role that elevates the status of the federal government in basin water management.2 The federal role in the management of Colorado River water is magnified by the multiple federally owned and operated water storage and conveyance facilities in the basin, which provide low-cost water and hydropower supplies to water users.

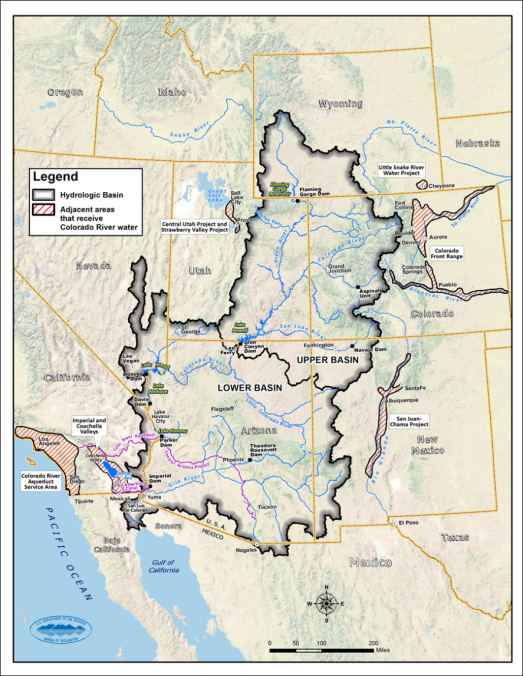

Colorado River water is used primarily for agricultural irrigation and municipal and industrial (M&I) purposes. The river's flow and stored water also are important for power production, fish and wildlife, and recreation, among other uses. A majority (70%) of basin water supplies are used to irrigate 5.5 million acres of land; basin waters also provide M&I water supplies to nearly 40 million people.3 Much of the area that depends on the river for water supplies is outside of the drainage area for the Colorado River Basin. Storage and conveyance facilities on the Colorado River provide trans-basin diversions that serve areas such as Cheyenne, WY; multiple cities in Colorado's Front Range (e.g., Fort Collins, Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, CO); Provo, UT; Albuquerque and Santa Fe, NM; and Los Angeles, San Diego, and the Imperial Valley in Southern California (Figure 1). Colorado River hydropower facilities can provide up to 42 gigawatts of electrical power per year. The river also provides habitat for a wide range of species, including several federally endangered species. It flows through 7 national wildlife refuges and 11 National Park Service (NPS) units; these and other areas of the river support important recreational opportunities.

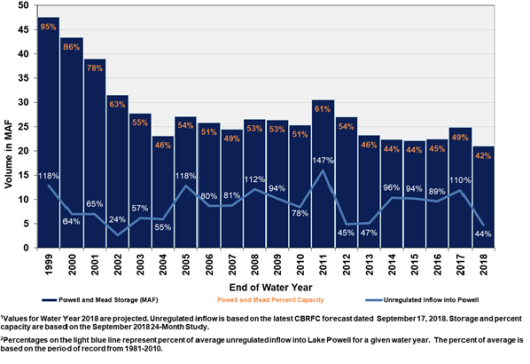

Precipitation and runoff in the basin are highly variable. Water conditions on the river depend largely on snowmelt in the basin's northern areas. Observed data (1906-2018) show that natural flows in the Colorado River Basin in the 20th century averaged about 14.8 million acre-feet (mafMAF) annually.4 Flows have dipped significantly during the current drought, which dates to 2000; natural flows from 2000 to 2018 averaged approximately 12.4 mafMAF per year.5 In 2018, Reclamation estimated that the 19-year period from 2000 to 2018 was the driest period in more than 100 years of record keeping.6 The dry conditions are consistent with prior droughts in the basin that were identified through tree ring studies; some of these droughts lasted for decades.7 Climate change impacts, including warmer temperatures and altered precipitation patterns, may further increase the likelihood of prolonged drought in the basin.

Pursuant to the multiple compacts, federal laws, court decisions and decrees, contracts, and regulatory guidelines governing Colorado River operations (collectively known as the Law of the River), Congress and the federal government play a prominent role in the management of the Colorado River. Specifically, Congress funds and oversees Reclamation's management of Colorado River Basin facilities, including facility operations and programs to protect and restore endangered species. Congress also hashas also approved and continues to actively consider Indian water rights settlements involving Colorado River waters, and development of new and expanded water storage in the basin. In addition, Congress has approved funding to mitigate drought and stretch basin water supplies and has considered new authorities for Reclamation to combat drought and enter into agreements with states and Colorado River contractors.

This report provides background on management of the Colorado River, including a discussion of trends and agreements since 2000. It also discusses the congressional role in the management of basin waters.

|

Figure 1. Colorado River Basin and Areas That Import Colorado River Water |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Reclamation, Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study, 2012. |

The Law of the River:

Foundational Documents and Programs

In the latter part of the 19th century, interested parties in the Colorado River Basin began to recognize that local interests alone could not solve the challenges associated with development of the Colorado River. Plans conceived by parties in California's Imperial Valley to divert water from the mainstream of the Colorado River were thwarted because these proposals were subject to the sovereignty of both the United States and Mexico.8 The river also presented engineering challenges, such as deep canyons and erratic water flows, and economic hurdles that prevented local or state groups from building the necessary storage facilities and canals to provide an adequate water supply. Because local or state groups could not resolve these "national problems," Congress considered ideas to control the Colorado River and resolve potential conflicts between the states.9 Thus, in an effort to resolve these conflicts and prevent litigation, Congress gave its consent for the states and Reclamation to enter into an agreement to apportion Colorado River water supplies in 1921.10

The below sections discuss the resulting agreement, the Colorado River Compact, and other documents and agreements that form the basis of the Law of the River, which governs Colorado River operations.11

Colorado River Compact

The Colorado River Compact of 1922, negotiated by the seven basin states and the federal government, was signed by all but one basin state (Arizona).12 Under the compact, the states established a framework to apportion the water supplies between the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin, with the dividing line between the two basins at Lee Ferry, AZ,13 near the Utah border.14 Each basin was apportioned 7.5 mafMAF annually for beneficial consumptive use, and the Lower Basin was given the right to increase its beneficial consumptive use by an additional 1 mafMAF annually. The agreement also required Upper Basin states to deliver to the Lower Basin a total of 75 million acre-feet (maf)MAF over each 10-year period, thus allowing for averaging over time to make up for low-flow years.15 The compact did not address inter- or intrastate allocations of water (which it left to future agreements and legislation), nor did it address water to be made available to Mexico, the river's natural terminus; this matter was addressed in subsequent international agreements. The compact was not to become binding until it had been approved by the legislatures of each of the signatory states and by Congress.

Boulder Canyon Project Act

Congress approved and modified the Colorado River Compact in the Boulder Canyon Project Act (BCPA) of 1928.16 The act ratified the 1922 compact, authorized the construction of a federal facility to impound water in the Lower Basin (Boulder Dam, later renamed Hoover Dam) and related facilities to deliver water in Southern California (e.g., the All-American Canal, which delivers Colorado River water to California's Imperial Valley), and apportioned the Lower Basin's 7.5 mafMAF per year among the three Lower Basin states (Table 1, Figure 1). It provided 4.4 mafMAF per year to California, 2.8 mafMAF to Arizona, and 300,000 acre-feet (afAF) to Nevada, with the states to divide any surplus waters among them. It also directed the Secretary of the Interior to serve as the sole contracting authority for Colorado River water use in the Lower Basin and authorized several storage projects for study in the Upper Basin.

Congress's approval of the compact in the BCPA was conditioned on a number of factors, including ratification by California and five other states (thereby allowing the compact to become effective without Arizona's concurrence), and California agreeing by act of its legislature to limit its water use to 4.4 mafMAF per year and not more than half of any surplus waters. California met this requirement by passing the California Limitation Act of March 4, 1929.17

Arizona Ratification and Arizona v. California Decision

Arizona did not ratify the Colorado River Compact until 1944, at which time the state began to pursue a federal project to bring Colorado River water to its primary population centers in Phoenix and Tucson. California opposed the project, arguing that under the doctrine of prior appropriation,18 California's historical use of the river trumped Arizona's rights to the Arizona allotment.19 California also argued that Colorado River apportionments under the BCPA included water developed on Colorado River tributaries, whereas Arizona claimed, among other things, that these apportionments included the river's mainstream waters only.

In 1952, Arizona filed suit in the U.S. Supreme Court to settle the issue. Eleven years later, in the 1963 Arizona v. California decision,20 the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Arizona, finding that Congress had intended to apportion the mainstream of the Colorado River and that California and Arizona each would receive one-half of surplus flows.21 The same Supreme Court decision held that Section 5 of the BCPA controlled the apportionment of waters among Lower Basin States, and that the BCPA (and not the law of prior appropriation) controlled the apportionment of water among Lower Basin states.22 The ruling was notable for its directive to forgo traditional Reclamation deference to state law under the Reclamation Act of 1902, and formed the basis for the Secretary of the Interior's unique role as water master for the Lower Basin.23 The decision also held that Native American reservations on the Colorado River were entitled to priority under the BCPA.24 Later decrees by the Supreme Court in 1964 and 1979 supplemented the 1963 decision.25

Following the Arizona v. California decision, Congress eventually authorized Arizona's conveyance project for Colorado River water, the Central Arizona Project (CAP), in the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968 (CRBPA).26 As a condition for California's support of the project, Arizona agreed that, in the event of shortage conditions, California's 4.4 mafMAF has priority over CAP water supplies.

1944 U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty27

In 1944, the United States signed a water treaty with Mexico (1944 U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty) to guide how the two countries share the waters of the Colorado River and the Rio Grande. The treaty established water allocations for the two countries and created a governance framework (the International Boundary and Water Commission) to resolve disputes arising from the treaty's execution.28 The treaty requires the United States to provide Mexico with 1.5 mafMAF of water annually, plus an additional 200,000 afAF when a surplus is declared. During drought, the United States may reduce deliveries to Mexico in similar proportion to reductions of U.S. consumptive uses. The treaty has been supplemented by additional agreements between the United States and Mexico, known as minutes.29

Upper Basin Compact and Colorado River Storage Project Authorizations

Projects originally authorized for study in the Upper Basin under BCPA were not allowed to move forward until the Upper Basin states determined their individual water allocations, which they did under the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact of 1948

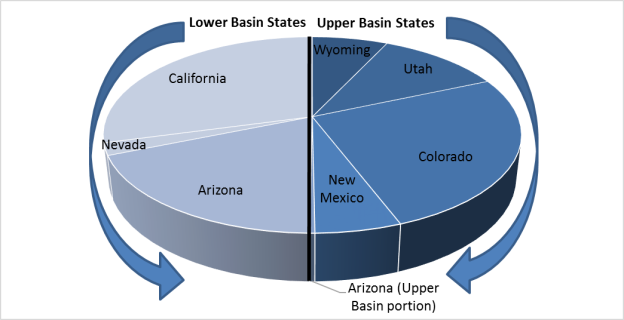

Percentages of overall allocation and million acre-feet (MAF) Source: CRS, using data from USGS, ESRI Data & Maps, 2017, Central Arizona Project, and ESRI World Shaded Relief Map. (Table 1, Figure 2). The Upper Basin Compact established Colorado (where the largest share of runoff to the river originates) as the largest entitlement holder in the Upper Basin, with rights to 51.75% of any Upper Basin flows after Colorado River Compact obligations to the Lower Basin have been met. Other states also received percentage-based allocations, including Wyoming (14%), New Mexico (11.25%), and Utah (23%). Arizona was allocated 50,000 afAF in addition to its Lower Basin apportionment, in recognition of the small portion of the state in the Upper Basin. Basin allocations by state following approval of the Upper Basin Compact (i.e., the allocations that generally guide current water deliveries) are shown below in Figure 2. The Upper Basin Compact also established the Upper Colorado River Commission, which coordinates operations and positions among Upper Basin states.

in addition to its Lower Basin apportionment, in recognition of the small portion of the state in the Upper Basin. The Upper Basin Compact also established the Upper Colorado River Commission, which coordinates operations and positions among Upper Basin states.

Table 1. Colorado River Apportionments: U.S. States

(apportionments assuming 15 million acre-feet in available natural flows annually)

|

Sub-basin/States |

Annual Apportionment (% of Sub-basin Apportionment) |

Annual Apportionment (acre-feet) |

|

|

Upper Basin States |

|||

|

Colorado |

51.75% |

[3,855,000] |

|

|

Wyoming |

14.00% |

[1,043,000] |

|

|

New Mexico |

11.25% |

[838,000] |

|

|

Utah |

23.00% |

[1,714,000] |

|

|

Arizona (Upper Basin portion) |

Approx. 0.60% |

50,000 |

|

|

Lower Basin States |

|||

|

Arizona (Lower Basin portion) |

37.33% |

2,800,000 |

|

|

California |

58.67% |

4,400,000 |

|

|

Nevada |

4.00% |

300,000 |

|

Sources: Colorado River Compact of 1922, Boulder Canyon Project Act (43 U.S.C. §617), Upper Colorado River Basin Compact of 1948, and 1944 U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty.

Notes: Allocations in table assume annual total flows of 15 million acre-feet (maf). Table does not reflect 1.5 maf to Mexico pursuant to the 1944 U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty. Deliveries under the treaty are shared equally between the amounts available in the Upper and Lower Basins. The Upper Basin Compact (other than amounts provided to Arizona) provides its apportionments in terms of percentage of the overall Upper Basin allocation, since there was uncertainty about how much water would remain after Colorado River Compact obligations to Lower Basin states were fulfilled.

after Colorado River Compact obligations to Lower Basin states were fulfilled. Therefore, outside of 50,000 AF provided annually to Arizona, the Upper Basin Compact provides its apportionments in terms of percentage of the overall Upper Basin allocation. Subsequent federal legislation paved the way for development of Upper Basin allocations. The Colorado River Storage Project (CRSP) Act of 1956 authorized storage reservoirs and dams in the Upper Basin, including the Glen Canyon, Flaming Gorge, Navajo, and Curecanti Dams. The act also established the Upper Colorado River Basin Fund, which receives revenues collected in connection with the projects, to be made available for defraying the project's costs of operation, maintenance, and emergency expenditures.

In addition to the aforementioned authorization of CAP in Arizona, the 1968 CRBPA amended CRSP to authorize several additional Upper Basin projects (e.g., the Animas La Plata and Central Utah projects) as CRSP participating projects. It also directed that the Secretary of the Interior propose operational criteria for Colorado River Storage Project units (including the releases of water from Lake Powell) that prioritize (1) Treaty Obligations to Mexico, (2) the Colorado River Compact requirement for the Upper Basin to deliver 75 mafMAF to Lower Basin states over any 10-year period, and (3) carryover storage to meet these needs. The CRBPA also established the Upper Colorado River Basin Fund and the Lower Colorado River Basin Development Fund, both of which were authorized to utilize revenues from hydropowerpower generation from relevant Upper and Lower Basin facilities to fund certain expenses in the sub-basins.30

Water Storage and Operations

Due to the basin's large water storage projects, basin water users are able to store as much as 60 mafMAF, or about four times the Colorado River's annual flows. Thus, storage and operations in the basin receive considerable attention, particularly at the basin's two largest dams and their storage reservoirs: Glen Canyon Dam/Lake Powell in the Upper Basin (26.2 mafMAF of storage capacity) and Hoover Dam/Lake Mead in the Lower Basin (26.1 mafMAF). The status of these projects is of interest to basin stakeholders and observers and is monitored closely by Reclamation.

Glen Canyon Dam, completed in 1963, provides the linchpin for Upper Basin storage and regulates flows from the Upper Basin to the Lower Basin, pursuant to the Colorado River Compact. It also generates approximately 5 billion kilowatt hours (KWh) of electricity per year, which the Western Area Power Administration (WAPA) supplies to 5.8 million customers in Upper Basin States.31 Other significant storage in the Upper Basin includes the initial "units" of the CRSP: the Aspinall Unit in Colorado (including Blue Mesa, Crystal, and Morrow Point dams on the Gunnison River, with combined storage capacity of more than 1 mafMAF),32 the Flaming Gorge Unit in Utah (including Flaming Gorge Dam on the Green River, with a capacity of 3.78 mafMAF), and the Navajo Unit in New Mexico (including Navajo Dam on the San Juan River, with a capacity of 1 mafMAF). The Upper Basin is also home to 16 "participating" projects which are authorized to use water for irrigation, municipal and industrial uses, and other purposes.33

In the Lower Basin, Hoover Dam, completed in 1936, provides the majority of the Lower Basin's storage and generates about 4.2 billion KWh of electricity per year for customers in California, Arizona, and Nevada.34 Also important for Lower Basin Operations are Davis Dam/Lake Mohave, which regulates flows to Mexico under the 1944 Treaty, and Parker Dam/Lake Havasu, which impounds water for diversion into the Colorado River Aqueduct (thereby allowing for deliveries to urban areas in southern California) and CAP (allowing for diversion to users in Arizona). Further downstream on the Arizona/California border, Imperial Dam (a diversion dam) diverts Colorado River water to the All-American Canal for use in California's Imperial and Coachella Valleys.

Annual Operating Plans

Reclamation monitors Colorado River reservoir levels and projects them 24 months into the future in monthly studies (called 24-month studies). The studies take into account forecasted hydrology, reservoir operations, and diversion and consumptive use schedules to model a single scenario of reservoir conditions. The studies inform operating decisions by Reclamation looking one to two years into the future. They express water storage conditions at Lake Mead and Lake Powell in terms of elevation, as feet above mean sea level (ft).

In addition to the 24-month studies, the CRBPA requires the Secretary to transmit to Congress and the governors of the basin states, by January 1 of each year, a report describing the actual operation for the preceding water year and the projected operation for the coming year. This report is commonly referred to as the annual operating plan (AOP). The AOP's projected January 1 water conditions for the upcoming calendar year establish a baseline for future annual operations.35

Since the adoption of guidelines by Reclamation and basin states in 2007 (see below section, "2007 Interim Guidelines"), operations of the Hoover and Glen Canyon Dams have been tied to specific pool elevations at Lake Mead and Lake Powell. For Lake Mead, the first level of shortage (1st Tier Shortage Condition), under which Arizona and Nevada's allocations would be decreased, would be triggered if Lake Mead falls below 1,075 ft. For Lake Powell, releases under tiered operations are based on storage levels in both Lake Powell and Lake Mead (specific delivery curtailments based on lake levels similar to Lake Mead have not been adopted).

As of January 2019, Reclamation predicted that Lake Mead's 2019 elevation would remain above 1,075 ft (approximately 9.6 mafMAF of storage) and that Lake Powell would remain at its prior year level (i.e., the Upper Elevation Balancing Tier) during 2019. However, Reclamation also projected that there was a 69% chance of a 1st Tier Shortage Condition at Lake Mead beginning in January 2020.36 Reclamation predicted a small (3%) chance of Lake Powell dropping to 3,490 feet, or minimum power pool (i.e., a level beyond which hydropower could not be generated) by 2020; the chance of this occurring by 2022 was greater (15%).37

Mitigating the Environmental Effects of Colorado River Basin Development

Construction of most of the Colorado River's water supply infrastructure predated major federal environmental protection statutes, such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA; 42 U.S.C. §§4321 et seq.) and the Endangered Species Act (ESA; 87 Stat. 884, 16 U.S.C. §§1531-1544). Thus, many of the environmental impacts associated with the development of basin resources were not originally taken into account. Over time, multiple efforts have been initiated to mitigate these effects. Some of the highest-profile efforts have been associated with water quality (in particular, salinity control) and the effects of facility operations on endangered species.

Salinity Control

Salinity and water quality are long-standing issues in the Colorado River Basin. Parts of the Upper Basin are covered by salt-bearing shale (which increases salt content in water inflows), and salinity content increases as the river flows downstream due to both natural leaching and return flows from agricultural irrigation. The 1944 U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty did not set water quality or salinity standards in the Colorado River Basin. However, after years of dispute between the United States and Mexico regarding the salinity of the water reaching Mexico's border, the two countries reached an agreement on August 30, 1973, with the signing of Minute 242 of the International Boundary and Water Commission.3839 The agreement guarantees Mexico that the average salinity of its treaty deliveries will be no more than 115 parts per million higher than the salt content of the water diverted to the All-American Canal at Imperial Dam in Southern California. To control the salinity of Colorado River water in accordance with this agreement, Congress passed the Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-320), which authorized desalting and salinity control facilities to improve Colorado River water quality. The most prominent of these facilities is the Yuma Desalting Plant, which was largely completed in 1992 but has never operated at capacity.3940 In 1974, the seven basin states also established water quality standards for salinity through the Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Forum.40

Endangered Species Efforts and Habitat Improvements

Congress enacted the ESA in 1973.4142 As basin species became listed in accordance with the act,4243 federal agencies and nonfederal stakeholders consulted with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to address the conservation of the listed species. As a result of these consultations, several major programs have been developed to protect and restore fish species on the Colorado River and its tributaries. Summaries of some of the key programs are below.

Upper Colorado Endangered Fish Recovery Program

The Upper Colorado Endangered Fish Recovery Program was established in 1988 to assist in the recovery of four species of endangered fish in the Upper Colorado River Basin.4344 Congress authorized this program in P.L. 106-392. The program is implemented through several stakeholders under a cooperative agreement signed by the governors of Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming; DOI; and the Administrator of WAPA. The recovery goals of the program are to reduce threats to species and improve their status so they are eventually delisted from the ESA. Some of the actions taken in the past include providing adequate instream flows for fish and their habitat, restoring habitat, reducing nonnative fish, augmenting fish populations with stocked fish, and conducting research and monitoring. Reclamation is the lead federal agency for the program and provides the majority of federal funds for implementation. It is also funded through a portion of Upper Basin hydropower revenues from WAPA; FWS; the states of Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah; and water users, among others.

San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program

The San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program was established in 1992 to assist in the recovery of ESA-listed fish species on the San Juan River, the Colorado's largest tributary.4445 The program is concerned with the recovery of the Razorback sucker (Xyrauchen texanus) and Colorado pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus Lucius). Congress authorized this program in P.L. 106-392 with the aim to protect the genetic integrity and population of listed species, conserve and restore habitat (including water quality), reduce nonnative species, and monitor species. The Recovery Program is coordinated by FWS. Reclamation is responsible for operating the Animas-La Plata Project and Navajo Dam on the San Juan River in a way that reduces effects on the fish populations. The program is funded by a portion of revenues from power generation, Reclamation, participating states, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Recovery efforts for listed fish are coordinated with the Upper Colorado River Program discussed above.

Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program

The Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program was established in 1997 in response to a directive from Congress under the Grand Canyon Protection Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-575) to operate Glen Canyon Dam "in such a manner as to protect, mitigate adverse impacts to, and improve the values for which Grand Canyon National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area were established."4546 This program uses experiments to determine how water flows affect natural resources south of the dam. Reclamation is in charge of modifying flows for experiments, and the U.S. Geological Survey conducts monitoring and other studies to evaluate the effects of the flows. The results are expected to better inform managers how to provide water deliveries and conserve species. The majority of program funding comes from hydropower revenues generated at Glen Canyon Dam.

Lower Colorado Multi-Species Conservation Program (MSCP)

The MSCP is a multistakeholder initiative to conserve 27 species (8 listed under ESA) along the Lower Colorado River while maintaining water and power supplies for farmers, tribes, industries, and urban residents.4647 The MSCP began in 2005 and is planned to last for at least 50 years.4748 The MSCP was created through consultation under ESA. To achieve compliance under ESA, federal entities involved in managing water supplies in the Lower Colorado River met with resource agencies from Arizona, California, and Nevada; Native American Tribes; environmental groups; and recreation interests to develop a program to conserve species along a portion of the Colorado River. A biological opinion (BiOp) issued by the FWS in 1997 served as a basis for the program. Modifications to the 1997 BiOp were made in 2002, and in 2005, the BiOp was renewed for 50 years. Nonfederal entities received an incidental take permit under Section 10(a) of the ESA for their activities in 2005 and shortly thereafter implemented a habitat conservation plan.

The objective of the MSCP is to create habitat for listed species, augment the populations of species listed under ESA, maintain current and future water diversions and power production, and abide by the incidental take authorizations for listed species under the ESA. The estimated total cost of the program over its lifetime is approximately $626 million in 2003 dollars ($882 million in 2018 dollars) and is to be split evenly between Reclamation (50%) and the states of California, Nevada, and Arizona (who collectively fund the remaining 50%).4849 The management and implementation of the MSCP is the responsibility of Reclamation, in consultation with a steering committee of stakeholders.

|

Hydropower Revenues Funding Colorado River Basin Activities Hydropower revenues are used to finance a number of activities throughout the Colorado River Basin. In the Lower Basin, the Lower Colorado River Basin Development Fund collects revenues from the CAP, as well as certain revenues from the Boulder Canyon and Parker-Davis Projects. These revenues are available without further appropriation toward defraying CAP operation and maintenance costs, salinity control efforts, and funding for Indian water rights settlements identified under the Arizona Water Settlements Act of 2004 (i.e., funding for water systems of the Gila River Indian Community and the Tohono O'odham Nation, among others). The Colorado River Dam fund utilizes power revenues generated by the Boulder Canyon Project (i.e., Hoover Dam) to fund operational and construction costs associated with that facility. In the Upper Basin, the Upper Colorado River Basin Fund collects revenues from the initial units of CRSP and funds operation and maintenance expenses, salinity control, the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program, and endangered fish studies on the Colorado and San Juan rivers. |

Tribal Water Rights

Twenty-two federally recognized tribes in the Colorado River Basin have quantified water diversion rights that have been confirmed by court decree or final settlement. These tribes collectively possess rights to 2.9 mafMAF per year of Colorado River water.4950 However, as of 2015, these tribes typically were using just over half of their quantified rights.5051 Additionally, 13 other basin tribes have reserved water rights claims that have yet to be resolved.5152 Increased water use by tribes with existing water rights, and/or future settlement of claims and additional consumptive use of basin waters by other tribes, is likely to exacerbate the competition for basin water resources.

The potential for increased use of tribal water rights (which, once ratified, are counted toward state-specific allocations where the tribal reservation is located) has been studied in recent years. In 2014, Reclamation, working with a group of 10 tribes with significant reserved water rights claims on the Colorado River, initiated a study known as the 10 Tribes Study.5253 The study, published in 2018, estimated that, cumulatively, the 10 tribes could have reserved water rights (including unresolved claims) to divert nearly 2.8 mafMAF per year.5354 Of these water rights, approximately 2 mafMAF per year were decreed and an additional 785,273 afAF (mostly in the Upper Basin) remained unresolved.5455 The report estimated that, overall, the 10 tribes are diverting (i.e., making use of) almost 1.5 mafMAF of their 2.8 mafMAF in resolved and unresolved claims. Table 21 shows these figures at the basin and sub-basin levels.5556 According to the study, the majority of unresolved claims in the Upper Basin are associated with the Ute Tribe in Utah (370,370 afAF per year), the Navajo Nation in Utah (314,926 afAF), and the Navajo Nation in the Upper Basin in Arizona (77,049 afAF).

Table 21. 10 Tribes Study: Tribal Water Rights and Diversions

(values in terms of acre-feet per year)

|

Current Use Diversions |

Reserved/Settled Water Rights |

Unresolved Water Rights |

Total Estimated Tribal Water Rights |

||

|

Upper Basin |

672,964 |

1,060,781 |

762,345 |

1,823,125 |

|

|

Lower Basin |

800,392 |

952,190 |

22,928 |

975,119 |

|

|

Total Basin |

1,473,356 |

2,012,971 |

785,273 |

2,798,244 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Colorado River Ten Tribes Partnership, Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes Partnership Tribal Water Study, Study Report, December 2018.

Note: Unresolved water rights include claims for potential water rights that have yet to be resolved.

Drought and the Supply/Demand Imbalance in the Colorado River Basin

When the Colorado River Compact was originally approved, it was assumed based on the historical record that average annual flows on the river were 16.4 mafMAF per year.5657 According to Reclamation data, from 1906 to 2018, observed natural flows on the river at Lee Ferry, AZ—the common point of measurement for observed basin flows—averaged 14.8 mafMAF annually.5758 Natural flows from 2000 to 2018 (i.e., during the ongoing drought) averaged considerably less than that—12.4 mafMAF annually.5859 While natural flows have trended down, consumptive use in the basin has grown and has regularly exceeded natural flows since 2000. From 1971 to 2015, average total consumptive use grew from 13 mafMAF to over 15 mafMAF annually.5960 Combined, the two trends have caused a significant drawdown of basin storage levels (Figure 3).

From 2009 to 2015, the largest consumptive water use occurred in the Lower Basin (7.5 mafMAF per year), while Upper Basin consumptive use averaged about 3.8 mafMAF annually.6061 Use of Treaty water by Mexico (1.5 mafMAF per year) and evaporative loss from reservoirs (approximately 2 mafMAF per year) in both basins also factored significantly into total basin consumptive use.6162 Notably, consumptive use in the Lower Basin, combined with mandatory releases to Mexico, regularly exceeds the mandatory 8.23 mafMAF per year that must be released from the Upper Basin to the Lower Basin and Mexico pursuant to Reclamation requirements.6263 This imbalance between Lower Basin inflows and use, known as the structural deficit, causes additional stress on basin storage.

The current drought in the basin has included some of the lowest flows on record.6364 According to Reclamation, the 19-year period from 2000 to 2018 was the driest period in more than 100 years of record keeping.6465 Observers have pointed out that flows in some recent years have been lower than would be expected given the amount of precipitation that has occurred, and have noted that warmer temperatures appear to be a significant contributor to these diminished flows.6566 Based on these and other observations, some have argued that Colorado River flows are unlikely to return to 20th century averages, and that future water supply risk is high.66

2012 Reclamation Study

A 2012 study by Reclamation projected a long-term imbalance in supply and demand in the Colorado River Basin.6768 In the study, Reclamation noted that the basin had thus far avoided serious impacts on water supplies due to the significant storage within the system, coupled with the fact that some Upper Basin states have yet to fully develop the use of their allocations.6869 However, Reclamation projected that in the coming half century, flows would decrease by an average of 9% at Lee Ferry and drought would increase in frequency and duration.6970 At the same time, Reclamation projected that demand for basin water supplies would increase, with annual consumptive use projected to rise from 15 mafMAF to 18.1-20.4 mafMAF by 2050, depending on population growth.7071 A range of 64%-76% of the growth in demand was expected to come from increased M&I demand.7172

Reclamation's 2012 study also posited several potential ways to alleviate future shortages in the basin, such as alternative water supplies, demand management, drought action plans, water banking, and water transfer/markets. Some of these options already are being pursued. In particular, some states have become increasingly active in banking unused Colorado River surface water supplies, including through groundwater banks or storage of unused surface waters in Lake Mead (see below section, "2007 Interim Guidelines").

Developments and Agreements Since 2000

Drought conditions throughout the basin have raised concerns about potential negative impacts on water supplies. Concerns center on uncertainty that might result if the Secretary of the Interior were to determine that a shortage condition exists in the Lower Basin, and that related curtailments were warranted. Some in Upper Basin States are also concerned about the potential for a compact call of Lower Basin states on Upper Basin states.7273 Drought and other uncertainties related to water rights priorities (e.g., potential tribal water rights claims) spurred the development of several efforts that generally attempted to relieve pressure on basin water supplies, stabilize storage levels, and provide assurances of available water supplies. Some of the most prominent developments since the year 2000 (i.e., the beginning of the current drought) are discussed below.

2003 Quantitative Settlement Agreement

Prior to the 2003 QSA, California had been using approximately 5.2 mafMAF of Colorado River on average each year (with most of its excess water use attributed to urban areas). Under the QSA, an agreement between several California water districts and DOI, California agreed to reduce its use to the required 4.4 mafMAF under the Law of the River.7374 It sought to accomplish this aim by quantifying Colorado River entitlement levels of several water contractors; authorizing efforts to conserve additional water supplies (e.g., the lining of the All-American Canal); and providing for several large-scale, long-term agriculture-to-urban water transfers. The QSA also committed the state to a path for restoration and mitigation related to the Salton Sea, a water body in Southern California that was historically sustained by Colorado River irrigation runoff from the Imperial and Coachella Valleys.7475

A related agreement between Reclamation and the Lower Basin states, the Inadvertent Overrun and Payback Policy (IOPP), went into effect concurrently with the QSA in 2004.7576 IOPP is an administrative mechanism that provides an accounting of inadvertent overruns in consumptive use compared to the annual entitlements of water users in the Lower Basin. These overruns must be "paid back" in the calendar year following the overruns, and the paybacks must be made only from "extraordinary conservation measures" above and beyond normal consumptive use.76

2004 Arizona Water Settlements Act

The 2004 Arizona Water Settlements Act (P.L. 108-451, AWSA) significantly altered the allocation of CAP water in Arizona and set the stage for some of the cutbacks in the state that are currently under discussion.7778 It ratified three water rights settlements (one in each title) between the federal government and the State of Arizona, the Gila River Indian Community (GRIC), and the Tohono O'odham Nation, respectively.7879 For the state and its CAP water users, the settlement resolved a final repayment cost for CAP by reducing the water users' reimbursable repayment obligation from about $2.3 billion to $1.65 billion. Additionally, Arizona agreed to new tribal and non-tribal allocations of CAP water so that approximately half of CAP's annual allotment would be available to Indian tribes in Arizona, at a higher priority than most other uses. The tribal communities were authorized to lease the water so long as the water remains within the state via the state's water banking authority. The act also authorized funds to cover the cost of infrastructure required to deliver the water to the Indian communities, much of it derived from hydropowerpower receipts accruing to the Lower Colorado River Basin Development Fund.

2007 Interim Guidelines/Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead

Another significant development in the basin was the 2007 adoption of the Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and the Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead (2007 Interim Guidelines). Development of the agreement began in 2005, when, in response to drought in the Southwest and the decline in basin water storage (and a record low point in Lake Powell of 33% active capacity), the Secretary of the Interior instructed Reclamation to develop coordinated strategies for Colorado River reservoir operations during drought or shortages.7980 The resulting guidelines included criteria for releases from Lakes Mead and Powell determined by "trigger levels" in both reservoirs, as well as a schedule of Lower Basin curtailments at different operational tiers (Table 32). Under the guidelines, Arizona and Nevada, which have junior rights to California, would face reduced allocations if Lake Mead elevations dropped below 1,075 ft. At the time, it was thought that the 2007 Guidelines would significantly reduce the risk of Lake Mead falling to 1,025 feet. The guidelines are considered "interim" because they were scheduled to expire in 20 years (i.e., at the end of 2026).

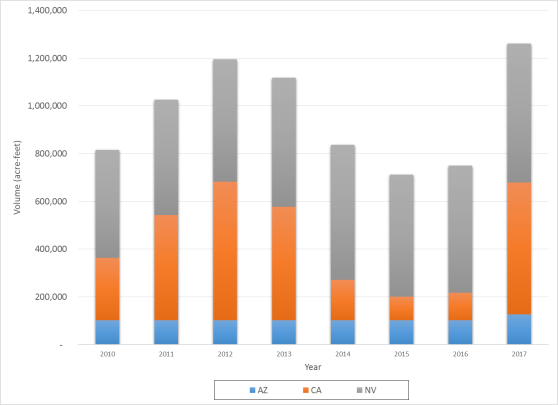

The 2007 agreement also included for the first time a mechanism by which parties in the Lower Basin were able to store conserved water in Lake Mead, known as Intentionally Created Surplus (ICS). Reclamation accounts for this water annually, and the users storing the water may access the surplus in future years, in accordance with the Law of the River. From 2013 to 2017, the portion of Lake Mead water in storage that was classified as ICS ranged from a low of 711,864 afAF in 2015 to a high of 1.261 mafMAF in 2017 (Figure 4).

|

Figure 4. U.S. Lower Basin States Intentionally Created Surplus Balance, 2010-2017 |

|

|

Source: Figure by CRS, based on data from Bureau of Reclamation, Colorado River Accounting and Water Use Report, Calendar Years 2010-2017, at https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/wtracct.html. |

Pilot System Conservation Program

In 2014, Reclamation and several major basin water supply agencies (Central Arizona Water Conservation District, Southern Nevada Water Authority, Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, and Denver Water) executed a memorandum of understanding to provide funding for voluntary conservation projects and reductions of water use. These activities had the goal of developing new system water,8081 to be applied toward storage in Lake Mead, by the end of 2019.8182 Congress formally authorized federal participation in these efforts in the Energy and Water Development and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2015 (P.L. 113-235, Division D), with an initial sunset date for the authority at the end of FY2018.8283 The Energy and Water Development and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244, Division A) extended the authority through the end of FY2022, with the stipulation that Upper Basin agreements could not proceed without the participation of the Upper Basin states through the Upper Colorado River Commission.8384 As of mid-2018, Reclamation estimated that the program had resulted in a total of 194,000 afAF of system water conserved.8485 These savings were carried out through 64 projects conserving 47,000 afAF in the Upper Basin and 11 projects conserving 147,000 afAF in the Lower Basin.8586

Minute 319 and Minute 323 Agreements with Mexico86

87

In 2017, the United States and Mexico signed Minute 323, which extended and replaced elements of a previous agreement, Minute 319, signed in 2012.8788 Minute 323 included, among other things, options for Mexico to hold water in reserve in U.S. reservoirs for emergencies and water conservation efforts, as well as U.S. commitments for flows to support the ecological health of the Colorado River Delta. It also extended initial Mexican cutback commitments made under Minute 319 (which were similar in structure to the 2007 cutbacks negotiated for Lower Basin states) and established a Binational Water Scarcity Contingency Plan that included additional cutbacks that would be triggered if drought contingency plans (DCPs) are approved by U.S. basin states (see following section, "Proposed2019 Drought Contingency Plans").

Proposed2019 Drought Contingency Plans

Ongoing drought conditions and the potential for water supply shortages have prompted renewedprompted discussions and negotiations focused on how to conserve additional basin water supplies. OnAfter several years of negotiations, on March 19, 2019, Reclamation and the Colorado River Basin states finalized DCPs for both the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin. BothThese plans require final approval by the states and authorization by Congress before they can be implementedrequired final authorization by Congress to be implemented. Following House and Senate hearings on the DCPs in early April, on April 16, 2019, Congress authorized the DCP agreements in the Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan Authorization Act (P.L. 116-14). Each of the basin-level DCPs is discussed below in more detail.

Upper Basin Drought Contingency Plan

The Upper Basin DCP aims to protect against Lake Powell reaching critically low elevations; it also authorizes storage of conserved water in the Upper Basin that could help establish the foundation for a water use reduction effort (i.e., a "Demand Management Program") that may be developed in the future.8889 Under the Upper Basin DCP, the Upper Basin states agree to operate system units to keep the surface of Lake Powell above 3,525 ft, which is 35 ft above the minimum elevation needed to run the dam's hydroelectric plant. Other large Upper Basin reservoirs (e.g., Navajo Reservoir, Blue Mesa Reservoir, and Flaming Gorge Reservoir) would be operated to protect the targeted Lake Powell elevation, potentially through drawdown of their own storage. TheIf established by the states, an Upper Basin DCP Demand Management Program also wouldwould likely entail willing seller/buyer agreements allowing for temporary paid reductions in water use that would provide for more storage volume in Lake Powell.

Reclamation has stated itsand other observers have stated their belief that these efforts will significantly decrease the risk of Lake Powell's elevation falling below 3,490 ft, an elevation at which significantly reduced hydropower generation is possible.89

Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan

The Lower Basin DCP is designed to require Arizona, California, and Nevada to curtail use and thereby contribute additional water to Lake Mead storage at predetermined "trigger" elevations, while also creating additional flexibility to incentivize voluntary conservation of water to be stored in Lake Mead, thereby increasing lake levels. Under the DCP, Nevada and Arizona (which were already set to have their supplies curtailed beginning at 1,075 ft under the 2007 Interim Guidelines) wouldare to contribute additional supplies to maintain higher lake levels (i.e., beyond previous commitments). The reductions of supply would reach their maximums when reservoir levels drop below 1,045 ft. At the same time, the Lower Basin DCP would, for the first time, include commitments for delivery cutbacks by California. These cutbacks would begin with 200,000 afAF (4.5%) in reductions at Lake Mead elevations of 1,040-1,045 ft, and would increase to as much as 350,000 afAF (7.9%) at elevations of 1,025 ft or lower.

The curtailments in the Lower Basin DCP would beare in addition to those agreed to under the 2007 Interim Guidelines and under Minute 323 with Mexico. Specific and cumulative reductions are shown in Table 32. In addition to the state-level reductions, under the Lower Basin DCP, Reclamation also would agree to pursue efforts to add 100,000 afAF or more of system water within the basin. Some of the largest and most controversial reductions under the Lower Basin planDCP would occur in Arizona, where pursuant to previous changes under the 2004 AWSA, a large group of agricultural users would face major cutbacks to their CAP water supplies.

Reclamation noteshas noted that the Lower Basin DCP significantly decreases the chance of Lake Mead elevations falling below 1,020 ft, which would be a critically low level.9091 Some parties have pointed out that although the DCP is unlikely to prevent a shortage from being declared at 1,075 ft, it would slow the rate at which the lake recedes thereafter.9192 Combined with the commitments from Mexico, total planned cutbacks under shortage scenarios (i.e., all commitments to date, combined) would reduce Lower Basin consumptive use by 241,000 afAF to 1.375 mafMAF per year, depending on Lake Mead's elevation.92

Table 32. Lower Basin Water Curtailment Volumes Under Existing and Proposed Agreements

(values in thousands of acre-feet)

|

Lake Mead Elevation (ft) |

2007 Interim Shortage Guidelines |

Minute 323 Delivery Reductions |

DCP Curtailment |

Binational Water Scarcity Conting. Plan |

Total Volume of Curtailment |

|||||||

|

AZ |

NV |

Mexico |

AZ |

NV |

CA |

Mexico |

AZ |

NV |

CA |

Lower Basin |

Mexico |

|

|

1,090 ->1,075 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

192 |

8 |

0 |

41 |

192 (6.8%) |

8 (2.6%) |

0 (0%) |

200 |

41 |

|

1,075 ->1,050 |

320 |

13 |

50 |

192 |

8 |

0 |

30 |

512 (18.2%) |

21 (7%) |

0 (0%) |

533 |

80 |

|

1,050 ->1,045 |

400 |

17 |

70 |

192 |

8 |

0 |

34 |

592 (21.1%) |

25 (8.3%) |

0 (0%) |

617 |

104 |

|

1,045 ->1,040 |

400 |

17 |

70 |

240 |

10 |

200 |

76 |

640 (22.8%) |

27 (9.0%) |

200 (4.5%) |

867 |

146 |

|

1,040 ->1,035 |

400 |

17 |

70 |

240 |

10 |

250 |

84 |

640 (22.8%) |

27 (9.0%) |

250 (5.6%) |

917 |

154 |

|

1,035 ->1,030 |

400 |

17 |

70 |

240 |

10 |

300 |

92 |

640 (22.8%) |

27 (9.0%) |

300 (6.8%) |

967 |

162 |

|

1,030 - 1,025 |

400 |

17 |

70 |

240 |

10 |

350 |

101 |

640 (22.8%) |

27 (9.0%) |

350 (7.9%) |

1,017 |

171 |

|

<1,025 |

480 |

20 |

125 |

240 |

10 |

350 |

150 |

720 (22.8%) |

30 (10.0%) |

350 (7.9%) |

1,100 |

275 |

Sources: Table by CRS, using data in the 2007 Interim Shortage Guidelines, Minute 323 between Mexico and the United States, the Draft Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan, and the Binational Water Scarcity Contingency Plan in Minute 323 between Mexico and the United States.

Drought Contingency Plan Approval

Opposition

Although the DCPs and the related negotiations have been widely praised, uncertainties and concerns remain, particularly those associated with approval and implementation of the agreements. Most of these concerns center on intrastate apportionment of reductions and related assurances by states and the federal government, including those related to the implementation of the DCPs as they relate to federal and state environmental laws. If the plans are not finalized in a timely manner, Reclamation has indicated that it may (in its delegated capacity as water master for the Secretary of the Interior) have to make cutbacks to state entitlements.93

Reclamation originally called on the basin states to approve their DCPs by the end of 2018, a goal that the seven states' representatives reportedly endorsed.94 When this deadline was not met, Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman set a January 31, 2019, deadline for approval by relevant entities. Citing the lack of DCP approval and completion, Reclamation on February 1, 2019, issued a Federal Register notice requesting input from state governors during the 15-day period beginning March 4 regarding recommendations for potential departmental actions in the event the DCPs are not completed. The DCPs were finalized in a signing ceremony on March 19, 2019, at which time Reclamation rescinded its Federal Register notice and the basin states formally requested DCP authorization by Congress.95 One major basin contractor, Imperial Irrigation District (a major holder of Colorado River water rights in Southern California), did not approve the DCPs.96 In their letter to Congress, the basin states requested that the DCPs be authorized by Congress by April 22, 2019.97

Issues for Congress

Funding and Oversight of Existing Facilities and Programs

The principal role of Congress as it relates to storage facilities on the Colorado River is funding and managementoversight of facility operations, construction, and programs to protect and restore endangered species (e.g., Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program and the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Program). In the Upper Basin, Colorado River facilities include the 17 active participating units in the Colorado River Storage Projects, as well as the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project. In the Lower Basin, major facilities include the Salt River Project and Theodore Roosevelt Dam, Hoover Dam and All-American Canal, Yuma and Gila Projects, Parker-Davis Project, Central Arizona Project, and Robert B. Griffith Project (now Southern Nevada Water System).

Congressional appropriations in support of Colorado River projects and programs typically account for a portion of overall project budgets. For example, the Lower Colorado Region's FY2017 operating budget was $517 million; $119.8 million of this total was provided by congressionaldiscretionary appropriations, and the remainder of funding came from power revenues (which are made available without further appropriation) and nonfederal partners.9897 In recent years, Congress has also authorized and appropriated funding that has targeted the Colorado River Basin in general (i.e., the Pilot System Conservation Plan). ItCongress may choose to extend or amend these and other authorities specific to the basin.

While discretionary appropriations for the Colorado River are of regular interest to Congress, Congress may also be asked to weigh in on Colorado River funding that is not subject to regular appropriations. For instance, in the coming years, the Lower Colorado River Basin Development Fund is projected to face a decrease in revenues98 and may thus have less funding available for congressionally established funding priorities for the Development Fund.

Indian Water Rights Settlements and Plans for New and Augmented Water Storage

Congress has previously approved Indian water rights settlements associated with more than 2 mafMAF of tribal diversion rights on the Colorado River. Only a portion of this water has been developed. Congress likely will face the decision of whether to fund development of previously authorized infrastructure associated with Indian water rights settlements in the Colorado River Basin. For example, the ongoing Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project is being built to serve the Jicarilla Apache Nation, the Navajo Nation, and the City of Gallup, New Mexico.99 Congress may also be asked to consider new settlements that may result in tribal rights to more Colorado River water. For example, in the 116th Congress, H.R. 244 would authorize the Navajo Nation Water Settlement in Utah.

In addition to development of new tribal water supplies, some states in the Upper Basin have indicated their intent to further develop their Colorado River water entitlements. For example, in the 115th Congress, Section 4310 of America's Water Infrastructure Act (P.L. 115-270) authorized the Secretary of the Interior to enter into an agreement with the State of Wyoming whereby the state would fund a project to add erosion control to Fontenelle Reservoir in the Upper Basin. The project would allow the state to potentially utilize an additional 80,000 acre-feet of water storage on the Green River, a tributary of the Colorado River.

Drought Contingency Plans

In addition to nonfederal state and stakeholder approvals, congressional authorization is needed to move forward with several significant parts of the DCPs. For instance, according to Reclamation, authority is needed for contractors to access ICS volumes in Lake Mead at elevations below 1,075 feet.100 Authority is also needed to for implementation of the Upper Basin DCP's demand management program, which would alter requirements for Lake Powell releases to the Lower Basin pursuant to the compact.

If the DCPs are not finalized and authorized by Congress, the 2007 Interim Guidelines would remain in effect through 2026, but the additional curtailments and programs agreed to in the DCPs and the binational water scarcity agreement with Mexico would not be implemented pursuant to those documents. Reclamation has warned that if the DCPs (or similar agreements) are not approved, the Secretary may assert his or her authority as water master to mandate additional cutbacks.101

Users in both the Upper and Lower Basins have an incentive to support negotiated curtailments in lieu of cutbacks and other operational changes they have not planned for. In the Lower Basin, negotiated curtailments and mutually agreed-upon conservation efforts are widely seen as preferable to the uncertainty that would come with unilateral federal cutbacks in the Lower Basin. They would also prevent drawdown of ICS balances that might occur in Lake Mead without authority for contractors to access these balances and receive deliveries in excess of their annual allotments. In the Upper Basin, if Lake Powell fell to levels such that hydropower production was not possible, the lack of low-cost power could negatively impact the economy of Upper Basin states. Similarly, the lack of hydropower revenues could imperil funding for infrastructure operations and maintenance and programs to conserve species and habitat on the river, among other things. Finally, if prolonged drought meant that Lake Powell could no longer make Colorado River Compact-required deliveries to the Lower Basin, then the Lower Basin might initiate a compact call on the Upper Basin. Such a scenario likely would lead to a protracted legal battle and could result in additional mandatory curtailments.

Congress may remain interested in implementation of the DCPs, including their success or failure at stemming further Colorado River cutbacks and the extent to which the plans comply with federal environmental laws such as NEPA. Similarly, Congress may be interested in the overall hydrologic status of the Colorado River Basin, as well as future efforts to plan for increased demand in the basin and stretch limited basin water supplies.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

J. C. Kammerer, "Largest Rivers in the United States," USGS Fact Sheet, May 1990, at https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1987/ofr87-242/pdf/ofr87242.pdf. |

||||

| 2. |

As discussed in the below section, "The Law of the River: Foundational Documents and Programs," the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928 made the Secretary of the Interior responsible for the distribution (via contract) of all Colorado River water delivered below Hoover Dam, and authorized such regulations as necessary to enter into these contracts. Subsequent court decisions confirmed the Secretary's power to apportion surpluses and shortages among and within Lower Basin states. |

||||

| 3. |

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study, p. 4, December 2012, at https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/programs/crbstudy/finalreport/index.html. Hereinafter "Reclamation 2012 Supply/Demand Study." |

||||

| 4. |

Department of the Interior, Open Water Data Initiative, Drought in the Colorado River Basin, accessed November 1, 2018, at https://www.doi.gov/water/owdi.cr.drought/en/#SupplyDemand. |

||||

| 5. |

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Lower Colorado Region, "Colorado River Basin Natural Flow and Salt Data-Current Natural Flow Data 1906-2016," at http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/NaturalFlow/current.html. Provisional natural flow measurements for 2017 and 2018 by U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Lower Colorado River Operations, at https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/riverops/model-info.html. Documentation for the natural flow calculation methods is available at http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/NaturalFlow/NaturalFlowAndSaltComptMethodsNov05.pdf. Hereinafter "Bureau of Reclamation Flow Data, 1906-2018." |

||||

| 6. |

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Annual Operating Plan for Colorado River Reservoirs, 2019, September 10, 2018, p. 8. Hereinafter "Reclamation 2019 Draft AOP." |

||||

| 7. |

For additional discussion on historic drought in the Colorado River, see CRS Report R43407, Drought in the United States: Causes and Current Understanding, by Peter Folger. |

||||

| 8. |

Arizona v. California, 373 U.S. 546 (1963). Hereinafter "Arizona v. California." |

||||

| 9. |

S. Doc. No. 67-142 (1922). For example, the states in the Upper Basin (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico), where the majority of the river's runoff originates, feared that a storage facility making water available downstream might form a basis for claims by Lower Basin states (California, Arizona, and Nevada) under prior appropriation doctrine before Upper Basin states could develop means to access their share. |

||||

| 10. |

Ch. 72, 42 Stat. 171 (1921). In lieu of litigation, interstate compacts have historically been a preferred means of allocating water among competing uses. Pursuant to the U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 10, Clause 3, no such compacts can be entered into without the consent of Congress. |

||||

| 11. |

The Law of the River is the commonly used shorthand for the multiple compacts, federal laws, court decisions and decrees, contracts, and regulatory guidelines collectively known under this heading. |

||||

| 12. |

Because the Colorado River Compact of 1922 did not specify the apportionments for individual states, Arizona initially refused to sign and ratify the agreement out of concern that rapidly growing California would lay claim to most of the Lower Basin's share of water. Arizona eventually signed and ratified the compact in 1944. See below section on "Arizona Ratification and Arizona v. California Decision." |

||||

| 13. |

Although the compact names the point as "Lee Ferry," it is also commonly referred to as "Lees Ferry," or "Lees Ferry." |

||||

| 14. |

Arizona receives water under both the Upper and the Lower Basin apportionments, since parts of the state are in both basins. |

||||

| 15. |

As a result, in some years in which Upper Basin inflows are less than 7.5 |

||||

| 16. |

Boulder Canyon Project Act (BCPA), Ch. 42, 45 Stat. 1057 (1928), codified as amended at 43 U.S.C. 617. |

||||

| 17. |

The Department of the Interior also requested that California prioritize its Colorado River rights among users before the Colorado River Compact became effective; the state established priority among these users for water in both "normal" and "surplus" years in the California Seven-Party Agreement, signed in August 1931. |

||||

| 18. |

Historically, water in the western United States has been governed by some form of the rule of prior appropriation. Under this rule, the party that first appropriates water and puts it to beneficial use thereby acquires a vested right to continue to divert and use that quantity of water against claimants junior in time. |

||||

| 19. |

Under the BCPA, Arizona and California also were to divide any excess, or surplus, supplies (i.e., amounts exceeding the 7.5 |

||||

| 20. |

Arizona v. California, 373 U.S. 546 (1963). |

||||

| 21. |

Id. at 546, 573. |

||||

| 22. |

Id. at 585-586. This decision gave the Secretary the power to apportion surpluses and shortages among and within Lower Basin states. |

||||

| 23. |

Pursuant to Section 8 of the Reclamation Act of 1902 (32 Stat. 388), Reclamation is not to interfere with state laws, "relating to the control, appropriation, use, or distribution of water used in irrigation" and that "the Secretary of the Interior, in carrying out provisions of the Act, shall proceed in conformance with such laws." |

||||

| 24. |

Indian reserved water rights were first recognized by the Supreme Court in Winters v. United States in 1908. Winters v. United States, 207 U.S. 564, 575-77 (1908). Under the Winters doctrine, when Congress reserves land (i.e., for an Indian reservation), it implicitly reserves water sufficient to fulfill the purpose of the reservation. Because the establishment of Indian reservations (and, therefore, of Indian water rights) generally predated large-scale development of water resources for non-Indian users, the water rights of tribes often are senior to those of non-Indian water rights. For more information on the resulting settlements, see below section on "Tribal Water Rights" and CRS Report R44148, Indian Water Rights Settlements, by Charles V. Stern. |

||||

| 25. |

Arizona v. California, 376 U.S. 340, 341 (1964). The 1964 decree determined, among other things, that all water in the mainstream of the Colorado River below Lee Ferry and within the United States would be "water controlled by the United States" and that the Secretary would release water under only three types of designations for a year: "normal, surplus, and shortage." The 1979 supplemental decree determined the present perfected rights of various parties in the Lower Basin. |

||||

| 26. |

Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968, P.L. 90-537. |

||||

| 27. |

For more information on the 1994 U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty and Colorado River water sharing issues with Mexico, see CRS Report R45430, Sharing the Colorado River and the Rio Grande: Cooperation and Conflict with Mexico, by Nicole T. Carter, Stephen P. Mulligan, and Charles V. Stern. |

||||

| 28. |

Treaty Between the United States of America and Mexico Respecting Utilization of Waters of the Colorado and Tijuana Rivers and of the Rio Grande, U.S.-Mex., February 3, 1944, 59 State. 1219, at https://www.ibwc.gov/Treaties_Minutes/treaties.html. The United States ratified the treaty on November 1, 1945, and Mexico ratified it on October 16, 1945. It became effective on November 8, 1945. |

||||

| 29. |

The complete list of minutes is available at https://www.ibwc.gov/Treaties_Minutes/Minutes.html. For more information on recent minutes, see below section, "Minute 319 and Minute 323 Agreements with Mexico." |

||||

| 30. |

Basin-wide operational commitments on the Colorado River were established in the 1970 Criteria for Coordinated Long-Range Operation of Colorado River Reservoirs, which coordinated the operation of reservoirs in the Upper and Lower Basins, including releases from Lake Powell and Lake Mead. These operating instructions have been modified by more recent operational agreements intended to mitigate the effects of long-term drought. |

||||

| 31. |

Bureau of Reclamation, Upper Colorado Region, "Glen Canyon Unit," accessed February 21, 2019, https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/crsp/gc/. |

||||

| 32. |

The Curecanti Unit was renamed the Aspinall Unit in 1980 in honor of U.S. Representative Wayne N. Aspinall of Colorado. |

||||

| 33. |

In total, 16 of the 22 Upper Basin projects authorized as part of CRSP have been developed. (The five remaining projects were determined by Reclamation to be infeasible.) For a complete list of projects, see https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/crsp/index.html. |

||||

| 34. |

Bureau of Reclamation, "Hoover Dam Frequently Asked Questions and Answers," accessed February 21, 2019, Bureau of Reclamation, Upper Colorado Region, Glen Canyon Unit, accessed February 21, 2019, https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/crsp/gc/. |

||||

| 35. |

Current and historical AOPs are available at https://www.usbr.gov/uc/water/rsvrs/ops/aop/. |

||||

| 36. |

Bureau of Reclamation, Colorado River System 5-Year Projected Future Conditions, accessed |

||||

| 37. |

The potential for Glen Canyon Dam being unable to generate hydropower is significant in part because of the importance of hydropower revenues (which fund operation and maintenance of CRSP facilities and environmental programs) to the Upper Basin. |

||||

| 38. |

Bureau of Reclamation, "Snowpack Benefits Colorado River Operations," press release, April 15, 2019, https://www.usbr.gov/newsroom/newsrelease/detail.cfm?RecordID=65645.

|

||||

|

The Yuma Desalting Plant's limited operations have been due in part to the cost of its operations (desalination can require considerable electricity to operate) and surplus flows in the Colorado River during some years compared to what was expected. In lieu of operating the plant, high-salinity irrigation water has been separated from the United States' required deliveries to Mexico and disposed of through a canal that enters Mexico and discharges into wetlands called the Ciénega de Santa Clara, near the Gulf of California. Whether and how the plant should be operated, and how the impacts on the Ciénega de Santa Clara from the untreated irrigation runoff should be managed, remain topics of some debate in the basin and between Mexico and the United States. |

|||||

|

Additional information about the forum and related salinity control efforts is available at Colorado River Basin, Salinity Control Forum, at https://www.coloradoriversalinity.org/. |

|||||

|

For more information on the ESA, see CRS Report RL31654, The Endangered Species Act: A Primer, by Pervaze A. Sheikh. |

|||||

|

There are several endangered species throughout the Colorado River Basin and some that are specifically found in the Colorado River, such as the Razorback sucker (Xyrauchen texanus), Bonytail chub (Gila elegans), Colorado pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus Lucius), and Humpback chub (Gila cypha). |

|||||

|

For more information, see Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program at http://www.coloradoriverrecovery.org/. |

|||||

|

For more information, see San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program at https://www.fws.gov/southwest/sjrip/. |

|||||

|

For more information, see Bureau of Reclamation, Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program, "Glen Canyon Dam High Flow Experimental Release," at https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/gcdHFE/. |

|||||

|

The stakeholders include six federal and state agencies, six tribes, and 36 cities and water and power authorities. Stakeholders serve more than 20 million residents in the region, and irrigate two million acres of farmland. For more information, see Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Program at https://www.lcrmscp.gov/. |

|||||

|

The program was formally authorized by Congress under Subtitle E of Title IX of P.L. 111-11. |

|||||

|

As of the end of 2018, more than $295 million had been spent on program implementation. Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Program, "Funding," https://www.lcrmscp.gov/steer_committee/funding.html. Accessed February 22, 2019. |

|||||

|

Reclamation 2012 Supply/Demand Study, Technical Report C, Appendix C9, p. C9-4. |

|||||

|