Israel: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from July 31, 2018 to June 15, 2022

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Country Background

- Historical Overview

- Government, Politics, and Society

- Overview

- Political and Societal Evolution

- Current Government

- Corruption Allegations Involving Netanyahu

- Major Domestic Issues

- Economy

- Israeli Security and Challenges

- Strategic and Military Profile

- Military Superiority and Homeland Security Measures

- Undeclared Nuclear Weapons Capability

- U.S. Cooperation

- Iran and the Region

- Iranian Nuclear Agreement and the U.S. Withdrawal

- Iran in Syria: Cross-Border Attacks with Israel

- Hamas and Gaza

- Key U.S. Policy Issues

- Security Cooperation

- Background

- Preserving Israel's Qualitative Military Edge (QME)

- U.S. Aid and Arms Sales to Israel

- Missile Defense Cooperation

- Pending Security Cooperation Legislation

- Sensitive Technology and Intelligence

- Bilateral Trade

- Israeli-Palestinian Issues

- Peace Process and International Involvement

- Jerusalem

- Settlements

Figures

Summary

Since Israel'Israel: Background and U.S. Relations

June 15, 2022

Since Israel’s founding in 1948, successive U.S. Presidents and many Members of Congress have demonstrated a commitment to Israel'’s security and to close U.S.-Israel

Jim Zanotti

cooperation. Strong bilateral ties influence U.S. policy in the Middle East, and Congress

Specialist in Middle

provides active oversight of the executive branch'’s actions. Israel is a leading recipient

Eastern Affairs

of U.S. foreign aid and a frequent purchaser of major U.S. weapons systems. By law, U.S. arms sales cannot adversely affect Israel's "qualitative military edge" over other countries in its region. The two The two

countries signed a free trade agreement in 1985, and the United States is Israel'’s largest

trading partners largest trading partner.

Israel regularly seeks help from the United States to bolster its regional security and defense capabilities. Legislation in Congress frequently includes proposals to strengthen U.S.-Israel cooperation.

Israel has a robust economy and an active democracy. The current power-sharing government came to power in June 2021 and includes eight parties from across the political spectrum, including the first-ever instance of an Arab-led party in the governing coalition. Prime Minister Naftali Bennett of the Yamina party and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid of the Yesh Atid party lead the coalition, which has been struggling to survive since losing majority support in Israel’s Knesset (parliament) in April 2022. Under the power-sharing agreement, Lapid could become a caretaker prime minister if the Knesset votes to hold new elections. Benjamin Netanyahu of the Likud party, who led Israel from 2009 to 2021 (and during an earlier stint in the 1990s) heads the opposition, and is on trial for allegations of criminal corruption. Domestic debates in Israel have centered on policies regarding the Palestinians and Israel’s Arab citizens, as well as issues regarding the economy, religion, and the judiciary’s role.

Israel’s political impasse with the Palestinians continues. Biden Administration officials have said that they seek to preserve the viability of a negotiated two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, while playing down near-term prospects for direct Israeli-Palestinian negotiationsU.S.-Israel cooperation, such as the U.S.-Israel Security Assistance Authorization Act of 2018 (S. 2497 and H.R. 5141).

Concerns about Iran dominate Israel's strategic calculations. Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu influenced President Trump's May 2018 decision to withdraw from the 2015 Iranian nuclear agreement and to reimpose sanctions on Iran, and Israel has made common cause with several Arab states to counter Iran's regional activities. During 2018, Israel and Iran have clashed over Iran's presence in Syria, fueling speculation about the possibility of broader conflict between the two countries and how Russia's presence in Syria might affect the situation. A serious threat persists from Hezbollah's rocket arsenal in Lebanon, adding to the uncertainty along Israel's northern border.

Hamas and other militant groups in Gaza may present less of an immediate threat to Israeli population centers. Nevertheless, various forms of conflict have taken place around the Gaza-Israel frontier in 2018. Improving difficult living conditions for Palestinians in Gaza while also ensuring Israel's security presents a challenge, given: Hamas' control of Gaza, Israeli and Egyptian control of its access points, and recent reductions in U.S. and Palestinian Authority (PA) funding.

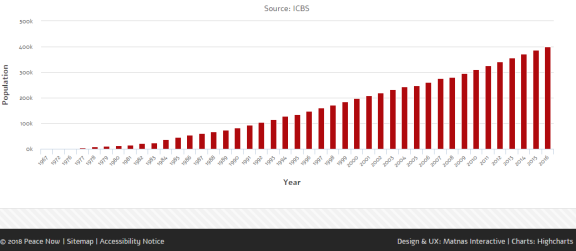

Israel's political impasse with the Palestinians continues. Israel has militarily occupied the West Bank since the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, with the PAPalestinian Authority exercising limited self-rule in some areas since the mid-1990s. The Sunni Islamist group Hamas (which the United States has designated as a terrorist organization) has controlled the Gaza Strip since 2007, and has clashed at times with Israel from there while also supporting unrest and violence elsewhere in the Israeli-Palestinian arena. Jerusalem and its holy sites continue to be a flashpoint, and the Trump Administration controversially recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and moved1990s. The Trump Administration's recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital in December 2017 and its relocation of the U.S. embassy there. In March 2022, Congress enacted legislation providing $1 billion in supplemental funding for the Iron Dome anti-rocket system after Israel heavily relied on Iron Dome during a May 2021 Gaza conflict. Israel may face challenges in improving difficult living conditions for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza while ensuring its own security. Concerns about both points have shaped some debates in Congress about how Israel uses U.S. aid. Approximately 660embassy there in May 2018 were greeted warmly by Israel but rejected by Palestinians and many other international actors. The success of an anticipated U.S. diplomatic proposal may depend on a number of factors, including whether Israel embraces it and can persuade Palestinians or Arab state leaders to do so. Approximately 590,000 Israelis live in residential neighborhoods or "settlements"“settlements” in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. These settlements are of disputed legality under international law.

Concerns about Iran strongly affect Israel’s strategic calculations. The Israeli government has previously sought to influence U.S. policy on Iran’s nuclear program, and its officials have varying views about a possible U.S. return to the 2015 international agreement. Meanwhile, Israel has made common cause with some Arab states to counter Iran’s regional activities. Israeli observers who anticipate the possibility of a future war similar in magnitude to Israel’s 2006 war against Iran’s ally Lebanese Hezbollah refer to skirmishes and covert actions since then involving Israel, Iran, and Iran’s allies as “the campaign between the wars.” A threat along Israel’s northern border persists from Hezbollah’s rocket arsenal and Iran-backed efforts to use Syrian bases and territory to bolster Hezbollah.

Growing Israeli cooperation with some Arab and Muslim-majority states led to the Abraham Accords: U.S.-brokered agreements in 2020 and 2021 to normalize or improve Israel’s relations with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan. Palestinian leaders decry Arab normalization with Israel that happens before Palestinian national demands are met, and the Biden Administration has stated it wants further Israeli-Arab state normalization to occur alongside progress on Israeli-Palestinian diplomacy.

U.S. officials regularly engage with Israeli interlocutors regarding their concerns about China and Russia (including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine). Israel seeks to address these concerns while expanding economic relations with China and avoiding Russian disruptions to Israeli military operations in Syria.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 31 link to page 31 link to page 34 link to page 35 link to page 36 link to page 36 link to page 36 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 43 link to page 44 link to page 45 link to page 5 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 29 link to page 30 Israel: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Country Background ....................................................................................................................... 3

Government and Politics ........................................................................................................... 3

Current Government and Its Uncertain Future ................................................................... 5 Major Domestic Issues ........................................................................................................ 7

Arab Citizens of Israel .................................................................................................. 7 Other Issues .................................................................................................................. 8

Economy ................................................................................................................................... 9 Military and Security Profile ................................................................................................... 10

General Overview ............................................................................................................. 10 Presumed Nuclear Capability ............................................................................................ 11

U.S.-Israel Security Cooperation .................................................................................................... 11 Israeli-Palestinian Issues and U.S. Policy ..................................................................................... 13

Overview of Disputes and Diplomatic Efforts ........................................................................ 13 The Biden Administration: Diplomacy and Human Rights Considerations ........................... 15 Settlements .............................................................................................................................. 17

Overview ........................................................................................................................... 17 Implications ...................................................................................................................... 20 U.S. Policy ........................................................................................................................ 21

Jerusalem ................................................................................................................................. 22

East Jerusalem Controversies ........................................................................................... 23 The “Status Quo”: Jews and Muslims at the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif .................. 27

Background ................................................................................................................. 27 Tensions in 2021 and 2022 ......................................................................................... 30

Reopening of U.S. Consulate in Jerusalem? ..................................................................... 31

Regional Threats and Relationships .............................................................................................. 32

Countering Iran ....................................................................................................................... 32

Iranian Nuclear Issue and Regional Tensions ................................................................... 32 Syria .................................................................................................................................. 34 Hezbollah in Lebanon ....................................................................................................... 34 Palestinian Militants and Gaza .......................................................................................... 35

Arab States .............................................................................................................................. 35

The Abraham Accords....................................................................................................... 35 Arab-Israeli Regional Energy Cooperation ....................................................................... 39

Turkey ..................................................................................................................................... 40

China: Investments in Israel and U.S. Concerns ........................................................................... 41

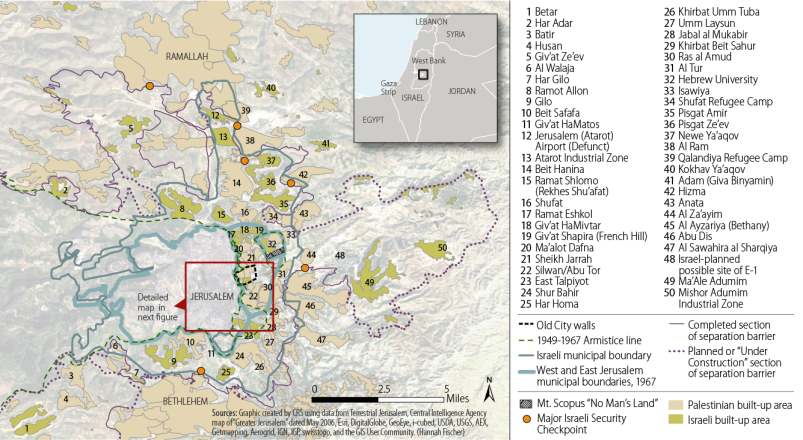

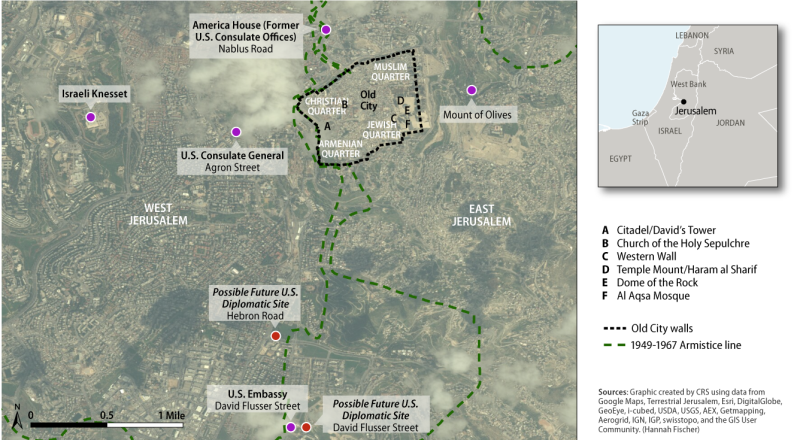

Figures Figure 1. Israel: Map and Basic Facts ............................................................................................. 1 Figure 2. Population of Israeli West Bank Settlements ................................................................. 18 Figure 3. Map of West Bank .......................................................................................................... 19 Figure 4. Greater Jerusalem ........................................................................................................... 25 Figure 5. Jerusalem: Key Sites in Context .................................................................................... 26

Congressional Research Service

link to page 32 link to page 52 link to page 9 link to page 15 link to page 21 link to page 47 link to page 49 link to page 52 link to page 54 link to page 54 Israel: Background and U.S. Relations

Figure 6. Old City of Jerusalem .................................................................................................... 28

Figure C-1. Map of the Golan Heights .......................................................................................... 48

Tables Table 1. Israeli Power-Sharing Government: Key Positions ........................................................... 5 Table 2. Security Forces in Israel ................................................................................................... 11 Table 3. Jewish Population in Specific Areas ................................................................................ 17

Appendixes Appendix A. Historical Background ............................................................................................. 43 Appendix B. Israeli Knesset Parties and Their Leaders ................................................................ 45 Appendix C. Golan Heights .......................................................................................................... 48 Appendix D. Examples of U.S.-Based, Israel-Focused Organizations ......................................... 50

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 50

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 5

Israel: Background and U.S. Relations

Overview U.S.-Israel defense, diplomatic, and economic cooperation has been close for decades, based on common democratic values, religious affinities, and security interests. On May 14, 1948, the United States was the first country to extend de facto recognition to the state of Israel (see Figure 1). Subsequently, relations have evolved through legislation, bilateral agreements, and trade.

Figure 1. Israel: Map and Basic Facts

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generatedand East Jerusalem. These settlements are of disputed legality under international law.

Israel has a robust economy and an active democracy. Prime Minister Netanyahu's governing coalition includes various right-of-center and religious parties. Domestic debates continue about the government's commitment to rule of law and freedom of expression, and how to balance market-friendly economic policies with individuals' concerns about cost of living. The role and status of Arab citizens presents challenges for the state and society. Netanyahu is facing a number of corruption allegations, and some political commentators anticipate that Netanyahu will call national elections ahead of the attorney general's decision on whether to indict him.

Introduction

U.S.-Israel defense, diplomatic, and economic cooperation has been close for decades, based on common democratic values, religious affinities, and security interests. On May 14, 1948, the United States was the first country to extend de facto recognition to the state of Israel. Subsequently, relations have evolved through legislation, bilateral agreements, and trade.

U.S. officials and lawmakers often consider Israel's security as they make policy choices in the Middle East. Congress provides military assistance to Israel and has enacted other legislation in explicit support of its security. Such support is part of a regional security order—largely based on U.S. arms sales to Israel and Arab countries—that has avoided major Arab-Israeli interstate conflict for about 45 years. Some Members of Congress have occasionally authorized and appropriated funding for programs benefitting Israel at a level exceeding that requested by the executive branch. Other Members have sought greater scrutiny of some of Israel's actions.

Iran continues to be a top Israeli security concern. Israel has sought to influence U.S. policy on Iran, and supported the Trump Administration's May 2018 withdrawal from the Iranian nuclear agreement. In recent years, Israel and Arab Gulf states have discreetly cultivated closer relations with one another in efforts to counter Iran.1 As Iran-backed groups have been successful in helping Syria's government regain effective control of the country, Israel has conducted a number of airstrikes targeting these groups. Israeli officials consider an indefinite Iranian presence in Syria to be a serious security threat exacerbating the threat already posed by Hezbollah in Lebanon, and have vowed to prevent it. As a result, Israel's relationship with Russia, which cooperates with Iran in Syria and hosts advanced air defense systems there, has become more important. Israel also remains threatened by Hamas and other terrorist groups in the Gaza Strip while considering ways to work on Gaza's difficult humanitarian and security situation with neighboring Egypt and a wide range of actors.

In the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, political disputes persist over key issues including security parameters, Israel-West Bank borders, Jewish settlements, Palestinian refugees, and the status of Jerusalem. Polls suggest wide skepticism among the Israeli public about prospects for a negotiated end to the conflict.2 Contentious domestic politics for both Israelis and Palestinians make it difficult for them to make diplomatic concessions, particularly in a climate where questions surround the continued leadership of Prime Minister Netanyahu (see "Corruption Allegations Involving Netanyahu" below) and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman and Palestinian Authority (PA) President Abbas.3 Possibly complicating the situation further, President Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital in December 2017 and the Administration moved the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem in May 2018. The Trump Administration may be contemplating a diplomatic proposal aimed at restarting Israeli-Palestinian negotiations with the support of the Arab states that Israel has been discreetly cooperating with against Iran. Israelis debate how their leaders should prioritize options such as participating in diplomatic initiatives, preserving the current facts on the ground, and acting unilaterally to influence outcomes.

Israeli leaders and significant segments of Israeli civil society regularly emphasize the importance of closeness with the United States. Yet, a number of geopolitical factors distinguish Israel from other developed countries, including the regional threats it faces, its unique historical experience, and its population's relatively higher level of direct military service.4

|

|

|

Country Background

Historical Overview

The quest for a modern Jewish homeland can be traced to the publication of Theodor Herzl's The Jewish State in 1896. Herzl was inspired by the concept of nationalism that had become popular among various European peoples in the 19th century, and was also motivated by European anti-Semitism. The following year, Herzl described his vision at the first Zionist Congress, which encouraged Jewish settlement in Palestine, the territory that had included the Biblical home of the Jews and was then part of the Ottoman Empire.

During World War I, the British government issued the Balfour Declaration, supporting the "establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people." Palestine became a British Mandate after the war and British officials simultaneously encouraged the national aspirations of the Arab majority in Palestine, insisting that its promises to Jews and Arabs did not conflict. Jews immigrated to Palestine in ever greater numbers during the Mandate period, and tension between Arabs and Jews and between each group and the British increased, leading to periodic clashes. Following World War II, the plight of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust gave the demand for a Jewish home added urgency, while Arabs across the Middle East concurrently demanded self-determination and independence from European colonial powers.

In 1947, the United Nations General Assembly developed a partition plan (Resolution 181) to divide Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, proposing U.N. trusteeship for Jerusalem and some surrounding areas. The leadership of the Jewish Yishuv (or polity) welcomed the plan because it appeared to confer legitimacy on the Jews' claims in Palestine despite their small numbers. The Palestinian Arab leadership and the League of Arab States (Arab League) rejected the plan, insisting both that the specific partition proposed and the entire concept of partition were unfair given Palestine's Arab majority. Debate on this question prefigured current debate about whether it is possible to have a state that both provides a secure Jewish homeland and is governed in accordance with democratic values and the principle of self-determination.

After several months of civil conflict between Jews and Arabs, Britain officially ended its Mandate on May 14, 1948, at which point the state of Israel proclaimed its independence and was immediately invaded by Arab armies. During and after the conflict, roughly 700,000 Palestinians were driven or fled from their homes, an occurrence Palestinians call the nakba ("catastrophe").5 Many became internationally designated refugees after ending up in areas of Mandate-era Palestine controlled by Jordan (the West Bank) or Egypt (the Gaza Strip), or in nearby Arab states. Palestinians who remained in Israel became Israeli citizens.

The conflict ended with armistice agreements between Israel and its neighboring Arab states: Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. The territory controlled by Israel within these 1949-1950 armistice lines is roughly the size of New Jersey. Israel has engaged in further armed conflict with neighbors on a number of occasions since then—most notably in 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982. Since the 1950s, Israel also has dealt with the threat of Palestinian guerrilla or terrorist attacks. In 1979, Israel concluded a peace treaty with Egypt, followed in 1994 by a peace treaty with Jordan, thus making another multi-front war less likely. Nevertheless, as discussed throughout the report, security challenges persist from Iran and groups allied with it, and from other developments in the Arab world.

Government, Politics, and Society

Overview

Israel is a parliamentary democracy in which the prime minister is head of government (see textboxAdditionally, the United States recognized the Golan Heights as part of Israel in 2019; however, U.N. Security Council Resolution 497, adopted on December 17, 1981, held that the area of the Golan Heights control ed by Israel’s military is occupied territory belonging to Syria. The current U.S. executive branch map of Israel is available at https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/israel/map.

U.S. officials and lawmakers often consider Israel’s security as they make policy choices in the Middle East. Congress regularly enacts legislation to provide military assistance to Israel and

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 39 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 36 Israel: Background and U.S. Relations

explicitly support its security. Such support is part of a regional security order—based heavily on U.S. arms sales to Israel and Arab countries—that has avoided major Arab-Israeli interstate conflict for nearly 50 years. Israel has provided benefits to the United States by sharing intelligence, military technology, and other innovations.

While Israel is the largest regular annual recipient of U.S. military aid, some Members of Congress have sought greater scrutiny of some of Israel’s actions. Some U.S. lawmakers express concern about Israel’s use of U.S. military assistance against Palestinians, in light of entrenched Israeli control in the West Bank and around the Gaza Strip, and diminished prospects for a negotiated Israeli-Palestinian two-state solution. A few seek oversight measures and legislation to distinguish certain Israeli actions in the West Bank and Gaza from general U.S. support for Israeli security.1

Since U.S. aid to Israel significantly increased in the 1970s in connection with Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt, developments in international trade have impacted Israel’s relations with the United States and other global actors. During that time, Israel’s economy has gone from that of a developing nation to one integrated into and on par with economies in Western countries, fueled by a booming high-tech industry and other scientific fields that attract worldwide investment and trade. Leveraging its military power, arms export capacity, and economic and technical strengths, Israel has deepened its relations with India and China as well as other countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

After the Cold War ended, the Middle East became more central to U.S. policy, especially after the September 11, 2001, Al Qaeda terrorist attacks on the U.S. homeland. Consequently, U.S.-Israel ties focused more on regional challenges—including those from various terrorist groups and Iran. Some changes in U.S. military posture and political emphasis in the region could affect Israeli assessments regarding the need for action independent from the United States. The United States helped Israel negotiate the Abraham Accords in 2020 and 2021 to normalize or improve Israel’s relations with various Arab and Muslim-majority states (see “The Abraham Accords”), and Israel has taken some steps without direct U.S. involvement to strengthen relations with other Abraham Accords states such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Within this context, President Biden has reemphasized the longtime U.S. commitment to Israel’s security (see “U.S.-Israel Security Cooperation”).

Iran continues to be a top Israeli security concern (see “Countering Iran”). Israel has sought to influence U.S. policy on Iran, including the approach to Iran’s nuclear program and deterrence of Iran-backed actors in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, the Gaza Strip, and Yemen. Israeli officials welcomed the U.S. withdrawal in 2018 from the international agreement on Iran’s nuclear program (known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA) and accompanying reimposition of U.S. sanctions on Iran’s core economic sectors. They seek to coordinate with U.S. counterparts on future action to prevent Iranian progress toward a nuclear weapon, whether or not the United States reenters the JCPOA or negotiates a separate international agreement. Low-level Israel-Iran conflict and covert rivalry persists in various settings—Iran itself, countries bordering Israel, cyberspace, and international waters.

In the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, political disputes persist over key issues including security parameters, Israel-West Bank borders, Jewish settlements, Palestinian refugees, and the status of

1 Rebecca Kheel, “Progressives ramp up scrutiny of US funding for Israel,” The Hill, May 23, 2021. One bill, the Two-State Solution Act (H.R. 5344), would expressly prohibit U.S. assistance (including defense articles or services) to further, aid, or support unilateral efforts to annex or exercise permanent control over any part of the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) or Gaza.

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 17 link to page 45 link to page 38 Israel: Background and U.S. Relations

Jerusalem (see “Israeli-Palestinian Issues and U.S. Policy”). Polls suggest widespread skepticism among the Israeli public about prospects for a negotiated end to the conflict.2 This skepticism fuels speculation and debate about Israeli alternatives such as indefinitely controlling or annexing West Bank areas, improving Palestinian living conditions and economic prospects to reduce tensions, or focusing more on building relations with Arab states.

Israel seeks to balance various considerations regarding China and Russia. Its leaders have taken some steps to address U.S. concerns regarding China’s possible misuse of Israeli technology or access to Israeli infrastructure (see “China: Investments in Israel and U.S. Concerns”), and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (see text box below). Yet, many leading Israeli government and business figures also favor maintaining a strong economic relationship with China, and Israeli security decisionmakers have an interest in avoiding Russian disruptions to Israel’s ability to act militarily in Syria.

Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

The Israeli government has publicly condemned Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine through statements and votes in international fora. Meanwhile, it has sought to provide political support for Ukraine and humanitarian relief for Ukrainians—including allowing over 15,000 Jewish and non-Jewish refugees to enter Israel—without alienating Russia.3 About 1.2 mil ion (around 15%) of Israel’s population are Russian speakers with family origins in the former Soviet Union.4 Since 2015, Russia’s military presence and air defense capabilities in Syria have given it influence over Israel’s ability to conduct airstrikes there (see “Syria”). Israel has used access to Syrian airspace to target Iranian personnel and equipment, especially those related to the transport of munitions or precision-weapons technology to Iran’s ally Hezbol ah in Lebanon.5 To date, Israel has refrained from providing lethal assistance to Ukraine or approving third-party transfers of weapons with proprietary Israeli technology.6 Under some Western pressure, Israel has contemplated providing defensive equipment, personal combat gear, and/or warning systems to Ukraine’s military, partly to project to existing arms export clients that it would be a reliable supplier in crisis situations.7 Israel announced an initial shipment of helmets and flak jackets to Ukrainian rescue forces and civilian organizations in May 2022.8

Country Background

Government and Politics Israel is a parliamentary democracy in which the prime minister is head of government (see text box below for more information) and the president is a largely ceremonial head of state. The unicameral parliament (the Knesset) elects a president for a seven-year term. The current president, Reuven Rivlin, took office in July 2014

2 See, e.g., Tamar Hermann and Or Anabi, “What Solutions to the Conflict with the Palestinians are Acceptable to Israelis?” Israel Democracy Institute, August 3, 2021.

3 Isabel Kershner, “Israelis Debate How Many, and What Kind of, Refugees to Accept,” New York Times, March 24, 2022.

4 Lilly Galili, “Russia-Ukraine war: For Israel's Russian speakers conflict is painful and personal,” Middle East Eye, February 25, 2022.

5 Zev Chafets, “Why Israel Won’t Supply the Iron Dome to Ukraine,” Bloomberg, March 11, 2022. 6 Barak Ravid, “Scoop: Israel rejects U.S. request to approve missile transfer to Ukraine,” Axios, May 25, 2022. 7 Yaniv Kubovich and Jonathan Lis, “Israeli Officials Inclined to Increase Ukraine Aid in Face of Russian Atrocities,” haaretz.com, May 3, 2022; Anna Ahronheim, “Israel to increase military, civilian aid to Ukraine – report,” jpost.com, May 4, 2022.

8 “In first, Israel sends 2,000 helmets, 500 flak jackets to Ukraine,” Times of Israel, May 18, 2022.

Congressional Research Service

3

Israel: Background and U.S. Relations

president, Isaac Herzog, took office in July 2021. Israel does not have a written constitution. Instead, Basic Laws lay down the rules of government and enumerate fundamental rights. Israel has an independent judiciary, with a system of magistrates'’ courts and district courts headed by a Supreme Court.

The political spectrum is highly fragmented, with small parties exercising disproportionate power due to the relatively low vote threshold for entry into the Knesset (3.25%), and larger parties needing small-party support to form and maintain coalition governments. Since Israel's founding, the average lifespan of an Israeli government has been about 23 months. In 2014, however, the Knesset somewhat tightened the conditions for bringing down a government.

through a dispersal or no-confidence vote.9 Primer on Israeli Electoral Process and Government-Building

Elections to Israel National laws provide parameters for candidate eligibility, general elections, and party primaries—including specific conditions and limitations on campaign contributions and public financing for parties.

|

|

Member |

Party |

Ministerial Position(s) |

Previous Knesset Terms |

|

Binyamin Netanyahu |

Likud |

Prime Minister Minister of Foreign Affairs |

8 |

|

Avigdor Lieberman |

Yisrael Beiteinu |

Minister of Defense |

5 (resigned Knesset seat in May 2016) |

|

Moshe Kahlon |

Kulanu |

Minister of Finance |

3 |

|

Naftali Bennett |

Ha'bayit Ha'Yehudi |

Minister of Education |

1 |

|

Ayelet Shaked |

Ha'bayit Ha'Yehudi |

Minister of Justice |

1 |

|

Gilad Erdan |

Likud |

Minister of Public Security Minister of Strategic Affairs Minister of Information |

4 |

|

Aryeh Deri |

Shas |

Minister of Interior |

3 |

|

Yisrael Katz |

Likud |

Minister of Transportation Minister of Intelligence and Atomic Energy |

6 |

|

Yoav Galant |

Kulanu |

Minister of Construction and Housing |

0 |

|

Sofa Landver |

Yisrael Beiteinu |

Minister of Immigrant Absorption |

6 |

Political and Societal Evolution

Israeli society and politics have evolved. In the first decades following its founding, Israeli society was dominated by secular Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jews who constituted the large majority of 19th- and early 20th-century Zionist immigrants. Many leaders from these immigrant communities sought to build a country dedicated to Western liberal and communitarian values. From 1948 to 1977, the social democratic Mapai/Labor movement led Israeli governing coalitions.

The 1977 electoral victory of Menachem Begin's more nationalistic Likud party helped boost the influence of previously marginalized groups, particularly Mizrahi (Eastern) Jews who had immigrated to Israel from Arab countries and Iran. This electoral result came at a time when debate in Israel was intensifying over settlement in the territories occupied during the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Begin and his successor in Likud, Yitzhak Shamir, helped drive the political agenda over the following 15 years. Although Labor under Yitzhak Rabin later initiated the Oslo peace process with the Palestinians, its political momentum slowed and reversed after Rabin's assassination in 1995.

Despite Labor's setbacks, its warnings that high Arab birth rates could eventually make it difficult for Israel to remain both a Jewish and a democratic state while ruling over the Palestinians gained traction among many Israelis. In this context, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, a longtime champion of the Israeli right and the settlement movement, split from Likud and established Kadima as a more centrist alternative in 2005. He was succeeded as Kadima's leader and prime minister by Ehud Olmert in 2006. Likud returned to power in 2009 with Netanyahu as prime minister (he had previously served in the position from 1996 to 1999). Since then Netanyahu has led two additional coalitions following elections in 2013 and 2015.9

The enduring appeal of Netanyahu and right-of-center parties to Israeli voters in recent years may stem from a number of factors, including

- Arguments by some that Palestinians have rejected peace and that Israeli military withdrawals from southern Lebanon (in 2000) and the Gaza Strip (in 2005) emboldened Hezbollah and Hamas and contributed to subsequent conflict.10

- The influence of distinct religious, ethnic, or ideological groups, such as Russian speakers who emigrated from the former Soviet Union in the 1990s, and citizens aligned with the "national religious" (modern Orthodox) movement. Both groups skew toward the political right and include many of the biggest supporters of settlements.

Given the fragmentation of Israeli political parties under its electoral system, compromise among diverse groups is a necessity for forming and maintaining a governing coalition. As mentioned above, the system generally gives smaller parties disproportionate influence on key positions they espouse. For example, Netanyahu relies on support from two Haredi (ultra-Orthodox Jewish) parties that are generally aligned with the other right-of-center parties on national security issues, but make specific demands (i.e., subsidies and military exemptions to support traditional lifestyles) in exchange for their backing. Such support is largely anathema to secular Israeli middle class voters, many of whom would prefer that government resources be used to benefit a broader cross-section of Israelis.

Also, many Arab Israelis, who make up nearly 20% of the population, are largely separate from Jewish Israeli citizens in where and how they live, are educated, and otherwise socialize. Arab Israeli citizens generally identify more closely with left-of-center parties. However, left-of-center parties face increased difficulty in forming governing coalitions because no Arab party has ever been part of a one.

Current Government

Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu presides over a coalition government that includes six parties generally characterized as right of center (see Appendix A). The varying interests of the coalition's members and some intra-party rifts contribute to difficulties in building consensus on several issues, including

- How to strengthen Israel's security and protect its Jewish character while preserving rule of law and freedom of expression for all citizens.

- How to promote general economic strength while addressing popular concerns regarding economic inequality and cost of living.

Corruption Allegations Involving Netanyahu

The Israeli police recommended in February 2018 that Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit indict Prime Minister Netanyahu for bribery, fraud, and breach of trust.11 Mandelblit may decide in 2019 whether to press charges.12 In response to the police recommendations, Netanyahu—who has consistently denied the allegations—said that the recommendations "will end with nothing" and that he will stay in office to pursue Israel's well-being.13 However, they could threaten Netanyahu's position as prime minister.

The recommendations cover two specific cases. One Israeli media source has summarized them as follows:

In Case 1000, Netanyahu and his wife are alleged to have received illicit gifts from billionaire benefactors, most notably the Israeli-born Hollywood producer Arnon Milchan, totaling NIS 1 million ($282,000). In return, Netanyahu is alleged by police to have intervened on Milchan's behalf in matters relating to legislation, business dealings, and visa arrangements.

Case 2000 involves a suspected illicit quid pro quo deal between Netanyahu and Yedioth Ahronoth publisher Arnon Mozes that would have seen the prime minister weaken a rival daily, the Sheldon Adelson-backed Israel Hayom, in return for more favorable coverage from Yedioth.14

Later in February, developments in ongoing investigations appeared to implicate Netanyahu or his close associates in additional instances of alleged corruption. One case deals with possible overtures made to a judge about quashing an investigation of Netanyahu's wife Sara in exchange for the judge's appointment as attorney general, and another deals with possible actions to enrich a telecom magnate in expectation of favorable media coverage.15 In June 2018, Sara Netanyahu was indicted, along with a former staffer from Netanyahu's office, for the fraudulent use of state funds.16

Legally, Netanyahu could continue in office if indicted, but he could face public pressure to resign, and his coalition partners could face public pressure to withdraw their support for the government. Israel's previous prime minister, Ehud Olmert, announced his decision to resign in July 2008 amid corruption-related allegations, two months before the police recommended charges against him.17

Major Domestic Issues

The Knesset has recently passed some notable legislation. In July 2018, it passed a Basic Law defining Israel as the national homeland of the Jewish people.18 Also in July, the Knesset voted to withhold funds from the Palestinian Authority to "penalize it for paying stipends to Palestinian prisoners in Israel, their families and the families of Palestinians killed or wounded in confrontations with Israelis."19 Another bill passed in July permits single women to be surrogate parents, but does not extend the same permission to single men or same-sex couples.20

Additionally, controversial legislation has passed to apply some aspects of Israeli law to settlements in the West Bank,21 and is pending to limit the Supreme Court's power of judicial review over legislation.22 Several of the government's opponents and critics have voiced warnings that these and other initiatives may stifle dissent or undermine the independence of key Israeli institutions such as the media, the judiciary, and the military.

Some government policies in the domestic sphere are the subject of contention. For example, in 2017, the government suspended a decision it had previously made to allow for a mixed-gender prayer space in the Western Wall plaza in Jerusalem's Old City. According to Netanyahu, the government is reviewing the issue and plans to suggest another approach.23 Another issue has been Israeli government policy regarding African migrants who have reached Israel. The policy has fluctuated, partly based on rulings from Israel's Supreme Court. Considerable international criticism had centered on government proposals—which have since been scrapped—to forcibly deport some migrants to third countries (Rwanda and Uganda).24

Early elections could happen (legally, elections are required in the second half of 2019) if the governing coalition splits over the cases against Prime Minister Netanyahu or some other issue. If early elections take place, Netanyahu (if he runs) could face challenges from figures on the right of the political spectrum (including Education Minister Naftali Bennett and Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman), or nearer the center or left (former finance minister Yair Lapid, Labor Party leader Avi Gabbay, and retired generals Gabi Ashkenazi and Benny Gantz). Reportedly, Netanyahu may call for elections before the attorney general decides on whether to bring criminal charges against him, in hopes of claiming a popular mandate to continue in office even if he is indicted.25

Economy

Israel has an advanced industrial, market economy in which the government plays a substantial role. Despite limited natural resources, the agricultural and industrial sectors are well developed. The engine of the economy is an advanced high-tech sector, including aviation, communications, computer-aided design and manufactures, medical electronics, and fiber optics. Israel still benefits from loans, contributions, and capital investments from the Jewish diaspora, but economic strength has lessened its dependence on external financing.

Israel's economy is experiencing a period of moderate growth (between 2.5% and 4% annually since 2014).26 While International Monetary Fund (IMF) growth projections for Israel remain close to 3% over

Aside from a moderate 2020 slump and robust 2021 recovery during the COVID-19 pandemic, over the past five years Israel’s economy has shown steady growth (around 3-5% annually). International Monetary Fund (IMF) growth projections remain in a similar range for the next five years, with inflation and unemployment expectations remaining generally low.37

Bilateral Trade

The United States is Israel’s largest single-country trading partner,38 and—according to 2021 data from the U.S. Census Bureau and Bureau of Economic Analysis—Israel is the United States’s 24th-largest trading partner.39 The two countries concluded a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in 1985, eliminating all customs duties between the two trading partners. The FTA includes provisions that protect both countries’ more sensitive agricultural sub-sectors with nontariff barriers, including import bans, quotas, and fees. Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZs) in Jordan and Egypt are considered part of the U.S.-Israel free trade area.40 In 2021, Israel imported approximately $12.8 bil ion in goods from and exported $18.7 bil ion in goods to the United States.41 The United States and Israel have launched several programs to stimulate Israeli industrial and scientific research, for which Congress has authorized and appropriated funds on several occasions.42

Although Israel’s overall macroeconomic profile and fiscal position appear favorable, itsyears,27 the Economist Intelligence Unit projects average growth of 3.8% through 2022 over much of that time due to expectations of greater domestic consumption and exports.28 For information on prospective natural gas exports, see CRS Report R44591, Natural Gas Discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean, by [author name scrubbed].

Although Israel's overall macroeconomic profile and fiscal position appears positive, the country has the highest relative poverty levels are the fifth highestpoverty level and the sixth-highest income inequality level within the 37-country Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).43 Israeli Haredim (ultra-Orthodox Jews) and Arabs are particularly at risk, with nearly half of both groups living in material poverty.44

35 Gila Stopler, “Basic Law Legislation: The Basic Law That Can Make or Break Israeli Constitutionalism,” ConstitutionNet, August 16, 2021.

36 Yonah Jeremy Bob and Gil Hoffman, “Is Gideon Sa’ar Israel's most impactful minister?” jpost.com, October 7, 2021.

37 Based on data from the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook Database, April 2022. 38 According to the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Trade, for 2021 the countries of the European Union accounted for 29.9% of Israel’s total trade volume, while the United States accounted for 16.4% and China 10.1%. Document available at https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/isdb_results/factsheets/country/details_israel_en.pdf.

39 Monthly U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, December 2021, available at https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/ft900/ft900_2112.pdf.

40 See https://www.trade.gov/qualifying-industrial-zones. 41 Statistics compiled by Foreign Trade Division, U.S. Census Bureau, available at http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5081.html.

42 CRS Report RL33222, U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel, by Jeremy M. Sharp. 43 OECD Economic Surveys: Israel, September 2020. 44 Ibid.

Congressional Research Service

9

link to page 15 Israel: Background and U.S. Relations

Military and Security Profile

General Overview

and Development (OECD).29 Poverty and inequality particularly disadvantage Arab Israelis and Israeli Haredim (ultra-Orthodox Jews).30

Israeli Security and Challenges

Strategic and Military Profile

Israel relies on a number of strengths, along with discreet coordination with Arab states, to manage potential threats to its security and existence.

Military Superiority and Homeland Security Measures

Israel maintains conventional military superiority relative to its neighbors and the Palestinians. Shifts in regional order and evolving asymmetric threats have led Israel to update its efforts to project military strength, deter attack, and defend its population and borders. Israel appears to have reduced some unconventional threats viaalso has developed advanced missile defense systems, and reported cyber defense and warfare capabilities, and heightened security measures vis-à-vis Palestinians.

capabilities.

According to estimates from IHS Jane'sJanes, Israel'’s military (see Table 2 for descriptions of various Israeli security forces) s military features total active duty manpower across the army, navy, and air force of approximately 180,000, plus 445,000 in reserve—numbers aided by mandatory conscription for most young Jewish Israeli men and women, followed by extended reserve duty. Israel'’s overall annual defense budget is approximately $16.417.6 billion, constituting about 4.63.7% of its total gross domestic product (GDP).31

45

Israel has a robust homeland security system featuring sophisticated early warning practices, thorough border and airport security controls, and reinforced rooms or shelters that are engineered to withstand explosions in most of the country'’s buildings. Israel also has proposed and partially constructed a national border fence network of steel barricades (accompanied at various points by watch towers, patrol roads, intelligence centers, and military brigades) designed to minimize militant infiltration, illegal immigration, and smuggling from Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and the Gaza Strip.46

Some observers cited in State Department reporting on human rights characterize certain Israeli security measures, including administrative detentions that affect many Palestinians, as violations of human rights or due process norms.47 Israeli authorities justify administrative detention to prevent imminent attacks or to detain suspects without releasing sensitive information,48 and the practice is subject to Israeli legal standards.49

45 “Israel - Defence Budget,” Jane’s Defence Budgets, April 4, 2022. For purposes of comparison, IHS Jane’s reports that the U.S. defense budget totals close to $759 billion annually, constituting approximately 3.3% of total GDP. The World Bank, citing data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, states the following figures for defense spending as a percentage of GDP in other key Middle Eastern countries as of 2020: Egypt-1.2%, Iran-2.2%, Iraq-4.1%, Jordan-5.0%, Lebanon-3.0%, Saudi Arabia-8.4%, Turkey-2.8%, United Arab Emirates-5.6%. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS.

46 Judah Ari Gross, “‘A wall of iron, sensors and concrete’: IDF completes tunnel-busting Gaza barrier,” Times of Israel, December 7, 2021; Gad Lior, “Cost of border fences, underground barrier, reaches NIS 6bn,” Ynetnews, January 30, 2018.

47 State Department, 2021 Country Report on Human Rights Practices: Israel, West Bank and Gaza. 48 “Israel weighs extending administrative detention of sick Palestinian teen,” Times of Israel, January 10, 2022. 49 State Department, 2021 Country Report on Human Rights Practices: Israel, West Bank and Gaza.

Congressional Research Service

10

Israel: Background and U.S. Relations

Table 2. Security Forces in Israel

Unit (and Supervising Ministry) Current Leader

Key Sub-units (if applicable)

Israel Defense Forces

Lieutenant General

Ground forces (including Oz Brigade commando units –

(Defense Ministry)

Aviv Kochavi

Maglan, Duvdevan, and Egoz)

Navy (including Shayetet 13 commando unit) Air force (including Shaldag commando unit) Intelligence directorate (Aman) (including Sayeret

Matkal commando unit)

Unit 8200 (decryption and signals intelligence)

Institute for Intelligence and

David Barnea

Special Operations (Mossad) (Prime Ministry)

Israel Security Agency

Ronen Bar

Yamas (undercover counterterrorism unit formally part

(Shin Bet or Shabak)

of border police but subordinate to Shin Bet)

(Prime Ministry)

Israel Police

Kobi Shabtai

Border police (Magav)

(Public Security Ministry)

o Regular units deployed at checkpoints and in rural

areas, the West Bank, and Jerusalem

o Yamam (special counterterrorism and rescue unit)

Yasam (riot and crowd control unit)

Israel Prison Service

Katy Perry

(Public Security Ministry)

Presumed Nuclear Capability

the Gaza Strip.32

Undeclared Nuclear Weapons Capability

Israel is not a party to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and maintains a policy of "“nuclear opacity"” or amimut. A 2017One report estimatedestimates that Israel possesses a nuclear arsenal of around 90 warheads.50around 80-85 warheads.33 The United States has countenanced Israel'’s nuclear ambiguity since 1969, when Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir and U.S. President Richard Nixon reportedly reached an accord whereby both sides agreed never to acknowledge Israel'’s nuclear arsenal in public.3451 Israel might have nuclear weapons deployable via aircraft, submarine, and ground-based missiles.3552 No other Middle Eastern country is generally thought to possess nuclear weapons.

U.S. Cooperation

Israeli officials closely consult with U.S. counterparts in an effort to influence U.S. decisionmaking on key regional issues. Israel's leaders and supporters routinely make the case to U.S. officials that Israel's security and the broader stability of the region remain critically important for U.S. interests. They also argue that Israel has multifaceted worth as a U.S. ally and that the Israeli and American peoples share core values.36 See Appendix B for selected U.S.-based interest groups relating to Israel. The United States and Israel do not have a mutual defense treaty or agreement that provides formal U.S. security guarantees.37

Iran and the Region

Iran remains of primary concern to Israeli officials largely because of (1) Iran's antipathy toward Israel, (2) Iran's broad regional influence, and (3) the possibility that Iran will be free of nuclear program constraints in the future. As mentioned above, in recent years Israel and Arab Gulf states have discreetly cultivated closer relations with one another in efforts to counter Iran.

Iranian Nuclear Agreement and the U.S. Withdrawal

Prime Minister Netanyahu has sought to influence U.S. decisions on the international agreement on Iran's nuclear program (known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA). He argued against the JCPOA when it was negotiated in 2015, and welcomed President Trump's May 2018 withdrawal of the United States from the JCPOA and accompanying reimposition of U.S. sanctions on Iran's oil and central bank transactions. In a September 2017 speech before the U.N. General Assembly, Netanyahu had called on the signatories of the JCPOA to "fix it or nix it."38 Then, a few days before President Trump's May announcement, Netanyahu presented information that Israeli intelligence operatives apparently seized in early 2018 from an Iranian archive. Netanyahu used the information, which purportedly describes past work by Iran on a nuclear weapons program, to express concerns about Iran's credibility and its potential to parlay existing know-how into nuclear-weapons breakthroughs after the JCPOA expires.39

Although concern about Iran and its nuclear program is widespread among Israelis, their views on the JCPOA vary. Netanyahu and his supporters in government have routinely complained that the JCPOA fails to address matters not directly connected to Iran's nuclear program, such as Iran's development of ballistic missiles and its sponsorship of terrorist groups.40 Media reports suggest that a number of current and former Israeli officials have favored preserving the JCPOA because of the limits it placed on Iranian nuclear activities for some time or these officials' doubts about achieving international consensus for anything stricter.41

Commentators speculate on the possibility that Israel might act militarily against Iranian nuclear facilities if Iran resumes certain activities currently stopped under the JCPOA.42 According to one analyst, one group of Israeli officials have preferred to keep the nuclear deal in place while focusing on pressing challenges in Syria, while another group (including Netanyahu) have favored seizing the opportunity to make common cause with the Trump Administration to pressure Iran economically and militarily.43 However, shortly after Netanyahu publicly presented the Iranian nuclear archive, he said in an interview that he was not seeking a military confrontation with Iran.44

Iran in Syria: Cross-Border Attacks with Israel45

A "shadow war" has developed between Israel and Iran over Iran's presence in Syria. In the early years of the Syria conflict, Israel primarily employed airstrikes to prevent Iranian weapons shipments destined for Hezbollah in Lebanon. Since 2017, with the government of Bashar al Asad increasingly in control of large portions of Syria's territory, Israeli leaders have expressed intentions to prevent Iran from constructing and operating bases or advanced weapons manufacturing facilities in Syria. The focus of Israeli military operations in Syria has expanded in line with an increasing number of Iran-related concerns there. Further exacerbating Israeli sensitivities, Iran-backed forces (particularly Hezbollah) have moved closer to the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights since late 2017 via actions against Syrian opposition groups.

On February 10, 2018, Iranian personnel based at Tiyas air base in central Syria apparently sent an armed drone into Israeli airspace. A senior Israeli military source was quoted as saying, "This is the first time we saw Iran do something against Israel—not by proxy. This opened a new period."46

In May 2018, Prime Minister Netanyahu asserted that Iran had transferred advanced weaponry to Syria (weaponized drones, ground-to-ground missiles, anti-aircraft batteries) in recent months. He stated that Israel was "determined to block Iran's aggression" and that "we do not want escalation, but we are prepared for any scenario."47

Since the February 10 incident, Israel has reportedly struck Iranian targets on multiple occasions. The resulting exchanges of fire (including the downing of an Israeli F-16 during the February incident) and subsequent official statements from Israel, Iran, Syria, and Russia have highlighted the possibility that limited Israeli strikes to enforce "redlines" against Iran-backed forces could expand into wider conflict, particularly in cases of miscalculation by one or both sides.

On May 10, according to the Israeli military, Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force fired rockets at Israeli military positions in the Golan Heights, as retaliation against earlier Israeli strikes against Iranian targets in Syria.48 This triggered Israeli strikes in Syria on a larger scale than any Israeli operations there since the 1973 Yom Kippur War.49 Reportedly, Israel has since conducted some additional airstrikes in Syria, and on two separate occasions in July its military claimed that it shot down a Syrian drone and a fighter jet over the Golan Heights using Patriot missiles.50

Russia51

Russia's advanced air defense systems in Syria could affect Israeli operations.52 To date, Russia does not appear to have acted militarily to thwart Israeli airstrikes against Iranian or Syrian targets. However, Russian officials' statements in response to Israeli actions in Syria since February have fueled speculation about Russia's position vis-à-vis Israel and Iran,53 given that Russia's military presence in Syria is protected by Iran-backed ground forces.

Israeli officials reportedly continue to consult with Russian officials about deconflicting Israeli military operations in Syria and discussing ways to limit Iran's presence there.54 In May 2018, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov called for the withdrawal of all non-Syrian forces from the southern border area "on a reciprocal basis."55 However, as of July, Hezbollah reportedly has been helping lead an offensive against rebels in southern Syria.56 In a press conference following his July 16 summit with President Trump, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated a desire to have the situation between Israel and Syria in the Golan Heights return to what it had been before Syria's civil war.57

Hezbollah in Lebanon

Hezbollah has challenged Israel's security near the Lebanese border for decades—with the antagonism at times contained near the border, and at times escalating into broader conflict.58 Speculation persists about the potential for wider conflict and its regional implications.59 In recent years, Israeli officials have sought to draw attention to Hezbollah's weapons buildup—including reported upgrades to the range, precision, and power of its projectiles—and its alleged use of Lebanese civilian areas as strongholds.60 Previously during Syria's civil war, Israel reportedly provided various means of support to rebel groups in the vicinity of the Syria-Israel border in order to prevent Hezbollah or other Iran-linked groups from controlling the area.61

Increased conflict between Israel and Iran over Iran's presence in Syria raises questions about the potential for Hezbollah's Lebanon-based forces to open another front against Israel. In April 2018, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah said that an Israeli strike on Iranian targets at Tiyas air base was a "pivotal incident in the history of the region that can't be ignored" and a "historic mistake." Earlier that same day, Hezbollah's deputy leader Naim Qassem said that Hezbollah would not open a front against Israel from Lebanon, but that it was ready for "surprises."62 One May analysis expressed doubt that either Israel or Iran would seek to expand the scope of their emerging conflict in Syria to Lebanon.63 However, the same analysis and some others speculated that if Israel-Iran conflict in Syria worsens and Iran feels cornered, it could look to gain leverage over Israel by having Hezbollah launch attacks from Lebanon.64

Hamas and Gaza

|

Major Israel-Hamas Conflicts Since 2008 December 2008-January 2009: Israeli code name "Operation Cast Lead" Three-week duration, first meaningful display of Palestinians' Iranian-origin rockets, Israeli air strikes and ground offensive Political context: Impending leadership transitions in Israel and United States; struggling Israeli-Palestinian peace talks (Annapolis process) Fatalities: More than 1,100 (possibly more than 1,400) Palestinians; 13 Israelis (3 civilians) November 2012: "Operation Pillar of Defense (or Cloud)" Eight-day duration, Palestinian projectiles of greater range and variety, Israeli airstrikes, prominent role for Iron Dome Political context: Widespread Arab political change, including rise of Muslim Brotherhood to power in Egypt; three months before Israeli elections Fatalities: More than 100 Palestinians, 6 Israelis (4 civilians) July-August 2014: "Operation Protective Edge/Mighty Cliff" About 50-day duration, Palestinian projectiles of greater range and variety, Israeli air strikes and ground offensive, extensive Palestinian use of and Israeli countermeasures against tunnels, prominent role for Iron Dome Political context: Shortly after (1) unsuccessful round of Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, (2) PA consensus government formation and end of Hamas's formal responsibilities for governing Gaza, (3) prominent youth killings Fatalities: More than 2,100 Palestinians, 71 Israelis (5 civilians), and 1 foreign worker |

Israel faces a threat from the Gaza Strip (via Hamas and other militant groups).65 Although Palestinian militants maintain rocket and mortar arsenals, the threat from projectiles has reportedly been diminished by Israel's Iron Dome defense system.66 Tunnels that Palestinian militants used somewhat effectively in a 2014 conflict with Israel have been largely neutralized by systematic Israeli efforts, with some financial and technological assistance from the United States.67 Under President Abdel Fattah al Sisi, Egyptian military efforts have significantly reduced smuggling over land into Gaza.

In 2018, protests and violence along security fences dividing Gaza from Israel have attracted international attention. Israel's use of live fire and the death of more than 120 Palestinians in the spring (including several deaths on May 14, the day that the U.S. embassy opened in Jerusalem) led the U.N. Human Rights Council to call in May for an "independent, international commission of inquiry" to produce a report.68 A June U.N. General Assembly resolution condemned both Israeli actions against Palestinian civilians and the firing of rockets from Gaza against Israeli civilians.69 Subsequently, some Israel-Gaza violence has ensued over Palestinians' use of incendiary kites or balloons to set fires in southern Israel and a sniper's killing of an Israeli soldier in July, fueling speculation about possible escalation.70

U.S. and PA funding reductions have added to questions about humanitarian assistance for Gaza's population, who remain largely dependent on external donor funding and face chronic economic difficulties and shortages of electricity and safe drinking water.71 Since 2007, as part of a larger regime of Israeli-Egyptian control over access to and from Gaza, Israel has limited the shipment of building materials into Gaza because of concerns that Hamas might divert materials for reconstruction toward military infrastructure. The possibility that humanitarian crisis could destabilize Gaza has prompted discussions among U.S., Israeli, and Arab leaders aimed at improving living conditions and reducing spillover threats.72 These discussions have sparked public debate about how closely humanitarian concerns should be linked with political outcomes involving Israel, Hamas, and the PA, or with an anticipated U.S. diplomatic initiative (see "Peace Process and International Involvement").73

Key U.S. Policy Issues

Security Cooperation74

Background

Strong bilateral relations have reinforced significant U.S.-Israel cooperation on defense, including military aid, arms sales, joint exercises, and information sharing. It also has included periodic U.S.-Israel cooperation in developing military technology.

U.S. military aid has helped transform Israel's armed forces into one of the most technologically sophisticated militaries in the world. This aid for Israel has been designed to maintain Israel's "qualitative military edge" (QME) over neighboring militaries, since Israel must rely on better equipment and training to compensate for a manpower deficit in a conflict against one or more regional states. U.S. military aid, a portion of which may be spent on procurement from Israeli defense companies, also has helped Israel build a domestic defense industry, and Israel in turn is one of the top exporters of arms worldwide.75

On November 30, 1981, the United States and Israel signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) establishing a framework for consultation and cooperation to enhance the national security of both countries. In 1983, the two sides formed a Joint Political Military Group to implement provisions of the MOU. Joint air and sea military exercises began in 1984, and the United States has constructed facilities to stockpile military equipment in Israel. In 1986, Israel and the United States signed an MOU—the contents of which are classified—for Israeli participation in the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI/"Star Wars"), under which U.S.-Israel co-development of the Arrow ballistic missile defense system has proceeded. In 1987, Israel was designated a "major non-NATO ally" by the Reagan Administration, and in 1996, under the terms of Section 517 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended, Congress codified this status, affording Israel preferential treatment in bidding for U.S. defense contracts and expanding its access to weapons systems at lower prices. In 2001, an annual interagency strategic dialogue, including representatives of diplomatic, defense, and intelligence establishments, was created to discuss long-term issues.

The U.S.-Israel Enhanced Security Cooperation Act (P.L. 112-150) of 2012 and U.S.-Israel Strategic Partnership Act (P.L. 113-296) of 2014 encouraged continued and expanded U.S.-Israel cooperation in a number of areas, including defense, homeland security, cyber issues, energy, and trade. The latter act designated Israel as a "major strategic partner" of the United States—a designation whose meaning has not been further defined in U.S. law or by the executive branch.

Preserving Israel's Qualitative Military Edge (QME)

Since the late 1970s, successive Administrations have argued that U.S. arms sales are an important mechanism for addressing the security concerns of Israel and other regional countries. During this period, some Members of Congress have argued that sales of sophisticated weaponry to Arab countries may erode Israel's QME over its neighbors. However, successive Administrations have maintained that Arab countries are too dependent on U.S. training, spare parts, and support to be in a position to use sophisticated U.S.-made arms against the United States, Israel, or any other U.S. ally in a sustained campaign. Arab critics routinely charge that Israeli officials exaggerate the threat they pose. The threat of a nuclear-armed or regionally bolstered Iran, though it has partially aligned Israeli and Sunni Arab interests in deterring a shared rival, may be exacerbating Israeli fears of a deteriorated QME, as Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states dramatically increase defense procurements from U.S. and other foreign suppliers.

In 2008, Congress enacted legislation requiring that any proposed U.S. arms sale to "any country in the Middle East other than Israel" must include a notification to Congress with a "determination that the sale or export of such would not adversely affect Israel's qualitative military edge over military threats to Israel."76 In parallel with this legal requirement, U.S. and Israeli officials frequently signal their shared understanding of the U.S. commitment to maintaining Israel's QME. However, the codified definition focuses on preventing arms sales to potential regional Israeli adversaries based on a calculation of conventional military threats, raising questions about the definition's applicability to evolving unconventional threats to Israel's security.

What might constitute a legally defined adverse effect to QME is not clarified in U.S. legislation. After the passage of the 2008 legislation, a bilateral QME working group was created allowing Israel to argue its case against proposed U.S. arms sales in the region.77 For example, former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates wrote that, in 2010, the Obama Administration addressed concerns that Israel's leaders had about the possible effect on QME of a large U.S. sale of F-15 aircraft to Saudi Arabia by agreeing to sell Israel additional F-35 aircraft.78

The U.S.-Israel Strategic Partnership Act (P.L. 113-296) enacted in December 2014 requires more frequent QME assessments and executive-legislative consultations. It also requires that QME determinations include evaluations of how potential arms sales would change the regional balance, while identifying measures Israel may need to take in response to the potential sales, and assurances or possible assurances from the United States to Israel as a result of the potential sales.

U.S. Aid and Arms Sales to Israel

Specific figures and comprehensive detail regarding various aspects of U.S. aid and arms sales to Israel are discussed in CRS Report RL33222, U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel, by [author name scrubbed]. That report includes information on conditions that, in each fiscal year, generally allow Israel to use its military aid earlier and more flexibly than other countries.

Aid

Israel is the largest cumulative recipient of U.S. foreign assistance since World War II. Since 1976, Israel has generally been the largest annual recipient of U.S. foreign assistance, with occasional exception of Iraq and Afghanistan after 2004. Since 1985, the United States has provided approximately $3 billion in grants annually to Israel. In the past, Israel received significant economic assistance, but now almost all U.S. bilateral aid to Israel is in the form of Foreign Military Financing (FMF). U.S. FMF to Israel represents approximately one-half of total FMF and between 15-20% of Israel's defense budget. The new 10-year bilateral military aid MOU commits the United States to $3.3 billion annually from FY2019 to FY2028, subject to congressional appropriations. The United States also generally provides some annual American Schools and Hospitals Abroad (ASHA) funding and funding to Israel for migration assistance.

Arms Sales

Israel uses approximately 74% of its FMF to purchase arms from the United States, in addition to receiving U.S. Excess Defense Articles (EDA). Given the new MOU's phase-out of Israeli use of FMF for domestic arms producers, by FY2028 all of Israel's FMF will go toward U.S.-origin arms.

Israel's procurement of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter from the United States has been underway since 2016. To date, Israel has received 12 F-35s, and it is under contract to receive a total of 50 by 2024.79 In late 2017, Israel was the first non-U.S. country to declare operational capability for the F-35, and it has reportedly used the aircraft in combat over Israel's northern border. Under the terms of its arrangements with the United States, Israel has had domestic contractors install customized equipment and weaponry, and it is the only F-35 recipient to date with the right to perform depot-level aircraft maintenance within its own borders.80

End-Use Monitoring and Leahy Law Vetting

Sales of U.S. defense articles and services to Israel are made subject to the terms of both the Arms Export Control Act (AECA) and the July 23, 1952, Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement between the United States and Israel (TIAS 2675). The 1952 agreement states:

The Government of Israel assures the United States Government that such equipment, materials, or services as may be acquired from the United States ... are required for and will be used solely to maintain its internal security, its legitimate self-defense ... and that it will not undertake any act of aggression against any other state.

Past Administrations have acknowledged that some Israeli uses of U.S. defense articles may have failed to meet the requirements under the AECA and the 1952 agreement that Israel only use such articles for self-defense and internal security purposes. These past Administrations have transmitted reports to Congress stating that "substantial violations" of agreements between the United States and Israel regarding arms sales "may have occurred." The most recent report of this type was transmitted in January 2007 in relation to concerns about Israel's use of U.S.-supplied cluster munitions during military operations against Hezbollah in Lebanon during 2006.81 Other examples include findings issued in 1978, 1979, and 1982 with regard to Israel's military operations in Lebanon and Israel's air strike on Iraq's nuclear reactor complex at Osirak in 1981.

Additionally, Section 620M of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA), as amended (commonly known as the Leahy Law),82 prohibits the furnishing of assistance authorized by the FAA and the AECA to any foreign security force unit where there is credible information that the unit has committed a gross violation of human rights. The State Department implements Leahy vetting to determine which foreign security force units (and individuals within the units) are eligible to receive U.S. assistance or training.