China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress

Changes from April 25, 2018 to May 21, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Introduction

- Issue for Congress

- Scope, Sources, and Terminology

- Background

- Overview of China's Naval Modernization Effort

- Underway for More Than 25 Years

- A Broad-Based Modernization Effort

- Quality vs. Quantity

- Limitations and Weaknesses

- Roles and Missions for China's Navy

- 2014 ONI Testimony

- Selected Elements of China's Naval Modernization Effort

- Anti-Ship Ballistic Missiles (ASBMs) and Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCMs)

- Submarines, Mines, and Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs)

- Aircraft Carriers and Carrier-Based Aircraft

- Navy Surface Combatants and Coast Guard Cutters

- Amphibious Ships and Aircraft, and Potential Floating Sea Bases

- Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs)

- Land-Based Aircraft and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs)

- Electromagnetic Railgun

- Nuclear and Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Weapons

- Maritime Surveillance and Targeting Systems

- Naval Cyber Warfare Capabilities

- Quantum Technology Capabilities

- Reported Potential Future Developments

- Chinese Naval Operations Away from Home Waters

- General

- Bases Outside China

- Numbers of Chinese Ships and Aircraft; Comparisons to U.S. Navy

- Numbers Provided by ONI

- Numbers Presented in Annual DOD Reports to Congress

- Comparing U.S. and Chinese Naval Capabilities

- DOD Response to China Naval Modernization

- 2017 National Security Strategy and 2018 National Defense Strategy

- Concept of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP)

- Efforts to Preserve U.S. Military Superiority

- Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in Global Commons (JAM-GC)

- Navy Response to China Naval Modernization

- May 2017 CNO White Paper

- Force Posture and Basing Actions

- Acquisition Programs

- Training and Forward-Deployed Operations

- Increased Naval Cooperation with Allies and Other Countries

- Issues for Congress

- Future Size and Capability of U.S. Navy

- Long-Range Carrier-Based Aircraft and Long-Range Weapons

- MQ-25 Stingray (Previously UCLASS Aircraft)

- Long-Range Anti-Ship and Land Attack Missiles

- Long-Range Air-to-Air Missile

- Navy's Ability to Counter China's ASBMs

- Breaking the ASBM's Kill Chain

- Endo-Atmospheric Target for Simulating DF-21D ASBM

- Navy's Ability to Counter China's Submarines

- Navy's Fleet Architecture

- Legislative Activity for FY2019

- FY2019 Budget Request

- Legislative Activity for FY2018

FY2018Coverage in Related CRS Reports FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R.2810/S. 1519 /P.L. 115-91)- House

- Senate

- Conference

- House

Figures

- Figure 1. Jin (Type 094) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine

- Figure 2. Yuan (Type 039A) Class Attack Submarine

- Figure 3. Acoustic Quietness of Chinese and Russian Nuclear-Powered Submarines

- Figure 4. Acoustic Quietness of Chinese and Russian Non-Nuclear-Powered Submarines

- Figure 5. Liaoning (Type 001) Aircraft Carrier

- Figure 6. Type 001A Aircraft Carrier

- Figure 7. J-15 Carrier-Capable Fighter

- Figure 8. Renhai (Type 055) Cruiser (or Large Destroyer)

- Figure 9. Luyang II (Type 052C) Class Destroyer

- Figure 10. Jiangkai II (Type 054A) Class Frigate

- Figure 11. Jingdao Type 056 Corvette

- Figure 12. Houbei (Type 022) Class Fast Attack Craft

- Figure 13. China Coast Guard Ship

- Figure 14. Yuzhao (Type 071) Class Amphibious Ship

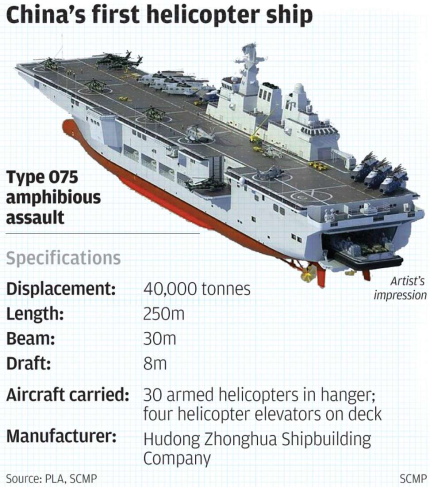

- Figure 15. Type 075 LHD

- Figure 16. AG-600 Amphibious Aircraft

- Figure 17. Very Large Floating Structure (VLFS)

Tables

- Table 1. PLA Navy Submarine Commissionings

- Table 2. PLA Navy Destroyer Commissionings

- Table 3. PLA Navy Frigate Commissionings

- Table 4. Numbers of PLA Navy Ships Provided by ONI in 2013

- Table 5. Numbers of PLA Navy Ships and Aircraft Provided by ONI in 2009

- Table 6. Numbers of PLA Navy Ships Presented in Annual DOD Reports to Congress

Summary

The question of how the United States should respond to China's military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, is a key issue in U.S. defense planning and budgeting.

China has been steadily building a modern and powerful navy since the early to mid-1990s. China's navy has become a formidable military force within China's near-seas region, and it is conducting a growing number of operations in more-distant waters, including the broader waters of the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and waters around Europe.

Observers view China's improving naval capabilities as posing a challenge in the Western Pacific to the U.S. Navy's ability to achieve and maintain control of blue-water ocean areas in wartime—the first such challenge the U.S. Navy has faced since the end of the Cold War. More broadly, these observers view China's naval capabilities as a key element of a broader Chinese military challenge to the long-standing status of the United States as the leading military power in the Western Pacific.

China's naval modernization effort encompasses a wide array of platform and weapon acquisition programs, including anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), submarines, surface ships, aircraft, unmanned vehicles (UVs), and supporting C4ISR (command and control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) systems. China's naval modernization effort also includes improvements in maintenance and logistics, doctrine, personnel quality, education and training, and exercises.

Observers believe China's naval modernization effort is oriented toward developing capabilities for doing the following: addressing the situation with Taiwan militarily, if need be; asserting and defending China's territorial claims in the South China Sea and East China Sea, and more generally, achieving a greater degree of control or domination over the SCS; enforcing China's view that it has the right to regulate foreign military activities in its 200-mile maritime exclusive economic zone (EEZ); defending China's commercial sea lines of communication (SLOCs), particularly those linking China to the Persian Gulf; displacing U.S. influence in the Western Pacific; and asserting China's status as a leading regional power and major world power.

Consistent with these goals, observers believe China wants its military to be capable of acting as an anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) force—a force that can deter U.S. intervention in a conflict in China's near-seas region over Taiwan or some other issue, or failing that, delay the arrival or reduce the effectiveness of intervening U.S. forces. Additional missions for China's navy include conducting maritime security (including antipiracy) operations, evacuating Chinese nationals from foreign countries when necessary, and conducting humanitarian assistance/disaster response (HA/DR) operations.

Potential oversight issues for Congress include the following:

- whether the U.S. Navy in coming years will be large enough and capable enough to adequately counter improved Chinese maritime A2/AD forces while also adequately performing other missions around the world;

- whether the Navy's plans for developing and procuring long-range carrier-based aircraft and long-range ship- and aircraft-launched weapons are appropriate and adequate;

- whether the Navy can effectively counter Chinese ASBMs and submarines; and

- whether the Navy, in response to China's maritime A2/AD capabilities, should shift over time to a more distributed fleet architecture.

Introduction

Issue for Congress

This report provides background information and issues for Congress on China's naval modernization effort and its implications for U.S. Navy capabilities. The question of how the United States should respond to China's military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, is a key issue in U.S. defense planning and budgeting. Many U.S. military programs for countering improving Chinese military forces (particularly its naval forces) fall within the U.S. Navy's budget.

The issue for Congress is how the U.S. Navy should respond to China's military modernization effort, particularly its naval modernization effort. Decisions that Congress reaches on this issue could affect U.S. Navy capabilities and funding requirements and the U.S. defense industrial base.

For an overview of the strategic and budgetary context in which China's naval modernization effort and its implications for U.S. Navy capabilities may be considered, see Appendix A.

Scope, Sources, and Terminology

This report focuses on China's naval modernization effort and its implications for U.S. Navy capabilities. For an overview of China's military as a whole, see CRS Report R44196, The Chinese Military: Overview and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed] and David Gitter.

This report is based on unclassified open-source information, such as the annual Department of Defense (DOD) report to Congress on military and security developments involving China,1 2015 and 2009 reports on China's navy from the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI),2 published reference sources such as IHS Jane's Fighting Ships, and press reports.

For convenience, this report uses the term China's naval modernization effort to refer to the modernization not only of China's navy, but also of Chinese military forces outside China's navy that can be used to counter U.S. naval forces operating in the Western Pacific, such as land-based anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), land-based surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), land-based Air Force aircraft armed with anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), and land-based long-range radars for detecting and tracking ships at sea.

China's military is formally called the People's Liberation Army (PLA). Its navy is called the PLA Navy, or PLAN (also abbreviated as PLA[N]), and its air force is called the PLA Air Force, or PLAAF. The PLA Navy includes an air component that is called the PLA Naval Air Force, or PLANAF. China refers to its ballistic missile force as the PLA Rocket Force (PLARF).

This report uses the term China's near-seas region to refer to the Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea—the waters enclosed by the so-called first island chain. The so-called second island chain encloses both these waters and the Philippine Sea that is situated between the Philippines and Guam.3

Background

Overview of China's Naval Modernization Effort4

Underway for More Than 25 Years

China's naval modernization effort has been underway for more than 25 years: Design work on the first of China's newer ship classes, for example, appears to have begun in the late-1980s.5 Some observers believe that China's military (including naval) modernization effort may have been reinforced or accelerated by China's observation of U.S. military operations against Iraq in Operation Desert Storm in 1991,6 and by a 1996 incident in which the United States deployed two aircraft carrier strike groups to waters near Taiwan in response to Chinese missile tests and naval exercises near Taiwan.7 One observer states that "since the end of [China's] ninth Five-Year Plan in 2000, China has embarked on an ambitious naval construction program. The goal was to dramatically increase the ability of the PLA Navy and the Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) to stage "blue-water" operations within the first and second island chains (including the Philippines and Indonesia) while enabling 'far-seas' deployments around much of the globe."8

A Broad-Based Modernization Effort

Although press reports on China's naval modernization effort sometimes focus on a single element, such as China's aircraft carrier program or its anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), China's naval modernization effort is a broad-based effort with many elements. China's naval modernization effort includes a wide array of platform and weapon acquisition programs, including programs for ASBMs, anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), land-attack cruise missiles (LACMs), surface-to-air missiles, mines, manned aircraft, submarines, aircraft carriers, destroyers, frigates, corvettes, patrol craft, amphibious ships, mine countermeasures (MCM) ships, underway replenishment ships, hospital ships, unmanned vehicles (UVs), and supporting C4ISR9 systems. Some of these acquisition programs are discussed in further detail below. China's naval modernization effort also includes improvements in maintenance and logistics, doctrine, personnel quality, education and training, and exercises.

Quality vs. Quantity

Until recently, China's naval modernization effort appeared to be focused less on increasing total platform (i.e., ship and aircraft) numbers than on increasing the modernity and capability of Chinese platforms. Changes in platform capability and the percentage of the force accounted for by modern platforms had generally been more dramatic than changes in total platform numbers. In some cases (such as submarines and coastal patrol craft), total numbers of platforms actually decreased over the past 20 years or so, but aggregate capability nevertheless increased because a larger number of older and obsolescent platforms have been replaced by a smaller number of much more modern and capable new platforms. ONI stated in 2015 that "China's force modernization has concentrated on improving the quality of its force, rather than its size. Quantities of major combatants have stayed relatively constant, but their combat capability has greatly increased as older combatants are replaced by larger, multi-mission ships."10

Some categories of ships, however, are now increasing in number; examples include (but are not necessarily limited to) the following:

- Ballistic missile submarines. Through 2008, China had only one ballistic missile submarine. By 2016, that figure had grown to four.

- Aircraft carriers. Until 2012, China had no aircraft carriers. China's first carrier entered service in 2012. China is building two additional carriers, and observers speculate China may eventually field a total force of four to six carriers.

- Corvettes (i.e., light frigates). Until 2014, China had no corvettes. Since then, China has built corvettes at a rapid rate, and 37 had reportedly entered service as of November 2017, with some observers projecting an eventual force of 60.

In addition, as shown in the 2017 column of Table 6, total numbers of destroyers and LST/LPD-type amphibious ships may now be increasing above the levels at which they had been over the last decade or so.

China is also building large numbers of cutters for its coast guard, and total numbers of larger cutters have grown substantially in recent years.

Whether they are to replace older ships or increase total numbers of ships, new ships are entering service with China's navy at a relatively high rate. A February 22, 2017, press report states the following:

In 2016, the PLA Navy commissioned 18 ships, including a Type 052D guided missile destroyer, three Type 054A guided missile frigates as well as six Type 056 corvettes.

These [18] ships have a total displacement of 150,000 tons, roughly half of the overall displacement of the [British] Royal Navy.

In January alone, the Navy commissioned three ships—one destroyer, one electronic reconnaissance ship and one corvette.11

China in late-2016 or early-2017 may have decided to increase its role on the world stage beyond previously planned levels, perhaps in part in reaction to a perception, correct or not, that the United States is reducing its role on the world stage.12 Such a decision by China could affect its naval modernization effort: pursuing a larger role on the world stage than previously planned could lead China to shift to a naval modernization effort that, while maintaining a focus on improving quality, also focuses more than previously planned on increasing total numbers of platforms. Put differently, while China until recently may have been aiming at developing a regionally powerful Navy with an added capability for conducting occasional, limited, or tightly focused naval operations in more distant waters, it might now pursue a more ambitious goal of developing a navy with more extensive capabilities for global operations.

Limitations and Weaknesses

Although China's naval modernization effort has substantially improved China's naval capabilities in recent years, observers believe China's navy currently has limitations or weaknesses in certain areas, including joint operations with other parts of China's military,13 antisubmarine warfare (ASW),14 a dependence on foreign suppliers for some ship components,15 and long-range targeting.16 China is working to overcome such limitations and weaknesses.17 ONI states that "Although the PLA(N) faces some capability gaps in key areas, it is emerging as a well equipped and competent force."18

The sufficiency of a country's naval capabilities is best assessed against that navy's intended missions. Although China's navy has limitations and weaknesses, it may nevertheless be sufficient for performing missions of interest to Chinese leaders. As China's navy reduces its weaknesses and limitations, it may become sufficient to perform a wider array of potential missions.

Roles and Missions for China's Navy

Observers believe China's naval modernization effort is oriented toward developing capabilities for doing the following:

- addressing the situation with Taiwan militarily, if need be;

- asserting and defending China's territorial claims in the South China Sea (SCS) and East China Sea (ECS), and more generally, achieving a greater degree of control or domination over the SCS;19

- enforcing China's view—a minority view among world nations—that it has the legal right to regulate foreign military activities in its 200-mile maritime exclusive economic zone (EEZ);20

- defending China's commercial sea lines of communication (SLOCs), particularly those linking China to the Persian Gulf;

- displacing U.S. influence in the Western Pacific; and

- asserting China's status as a leading regional power and major world power.21

Most observers believe that, consistent with these goals, China wants its military to be capable of acting as an anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) force—a force that can deter U.S. intervention in a conflict in China's near-seas region over Taiwan or some other issue, or failing that, delay the arrival or reduce the effectiveness of intervening U.S. forces.22 (A2/AD is a term used by U.S. and other Western writers. During the Cold War, U.S. writers used the term sea-denial force to refer to a maritime A2/AD force.) ASBMs, ASCMs, attack submarines, and supporting C4ISR systems are viewed as key elements of China's emerging maritime A2/AD force, though other force elements are also of significance in that regard.

China's maritime A2/AD force can be viewed as broadly analogous to the sea-denial force that the Soviet Union developed during the Cold War with the aim of denying U.S. use of the sea and countering U.S. naval forces participating in a NATO-Warsaw Pact conflict. One difference between the Soviet sea-denial force and China's emerging maritime A2/AD force is that China's force includes conventionally armed ASBMs capable of hitting moving ships at sea.

Additional missions for China's navy include conducting maritime security (including antipiracy) operations, evacuating Chinese nationals in foreign countries when necessary, and conducting humanitarian assistance/disaster response (HA/DR) operations.

DOD states that

As China's global footprint and international interests have grown, its military modernization program has become more focused on supporting missions beyond China's periphery, including power projection, sea lane security, counterpiracy, peacekeeping, and humanitarian assistance/disaster relief (HA/DR).23

DOD also states that

China's maritime emphasis and attention to missions guarding its overseas interests have increasingly propelled the PLA beyond China's borders and its immediate periphery. The PLAN's evolving focus—from "offshore waters defense" to a mix of "offshore waters defense" and "far seas protection"—reflects the high command's expanding interest in a wider operational reach. Similarly, doctrinal references to "forward edge defense" that would move potential conflicts far from China's territory suggest PLA strategists envision an increasingly global role.24

DOD also states that

The PLAN continues to develop into a global force, gradually extending its operational reach beyond East Asia and into what China calls the "far seas." The PLAN's latest naval platforms enable combat operations beyond the reaches of China's land-based defenses. In particular, China's aircraft carrier and planned follow-on carriers, once operational, will extend air defense umbrellas beyond the range of coastal systems and help enable task group operations in "far seas." The PLAN's emerging requirement for sea-based land-attack will also enhance China's ability to project power. More generally, the expansion of naval operations beyond China's immediate region will also facilitate non-war uses of military force.25

DOD states that China's 2015 defense white paper, labeled a "military strategy" and released in May 2015, "elevated the maritime domain within the PLA's formal strategic guidance and shifted the focus of its modernization from 'winning local wars under conditions of informationization' to 'winning informationized local wars, highlighting maritime military struggle."26 The white paper states that

With the growth of China's national interests, its national security is more vulnerable to international and regional turmoil, terrorism, piracy, serious natural disasters and epidemics, and the security of overseas interests concerning energy and resources, strategic sea lines of communication (SLOCs), as well as institutions, personnel and assets abroad, has become an imminent issue....

To implement the military strategic guideline of active defense in the new situation, China's armed forces will adjust the basic point for PMS [preparation for military struggle]. In line with the evolving form of war and national security situation, the basic point for PMS will be placed on winning informationized local wars, highlighting maritime military struggle and maritime PMS....

In line with the strategic requirement of offshore waters defense and open seas protection, the PLA Navy (PLAN) will gradually shift its focus from "offshore waters defense" to the combination of "offshore waters defense" with "open seas protection," and build a combined, multi-functional and efficient marine combat force structure. The PLAN will enhance its capabilities for strategic deterrence and counterattack, maritime maneuvers, joint operations at sea, comprehensive defense and comprehensive support....

The seas and oceans bear on the enduring peace, lasting stability and sustainable development of China. The traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned, and great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests. It is necessary for China to develop a modern maritime military force structure commensurate with its national security and development interests, safeguard its national sovereignty and maritime rights and interests, protect the security of strategic SLOCs and overseas interests, and participate in international maritime cooperation, so as to provide strategic support for building itself into a maritime power.27

2014 ONI Testimony

In his prepared statement for a January 30, 2014, hearing on China's military modernization and its implications for the United States before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Jesse L. Karotkin, ONI's Senior Intelligence Officer for China, summarized China's naval modernization effort. For the text of Karotkin's statement, see Appendix B.

Selected Elements of China's Naval Modernization Effort

Anti-Ship Ballistic Missiles (ASBMs) and Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCMs)

Anti-Ship Ballistic Missiles (ASBMs)

China is fielding an ASBM, referred to as the DF-21D, that is a theater-range ballistic missile equipped with a maneuverable reentry vehicle (MaRV) designed to moving hit ships at sea. A second type of Chinese theater-range ballistic missile, the DF-26, may also have an anti-ship capability. DOD states that

China's conventionally armed CSS-5 Mod 5 (DF-21D) anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) gives the PLA the capability to attack ships, including aircraft carriers, in the western Pacific Ocean.

In 2016, China began fielding the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), which is capable of conducting conventional and nuclear precision strikes against ground targets and conventional strikes against naval targets in the western Pacific Ocean.28

Observers have expressed strong concern about China's ASBMs, because such missiles, in combination with broad-area maritime surveillance and targeting systems, would permit China to attack aircraft carriers, other U.S. Navy ships, or ships of allied or partner navies operating in the Western Pacific. The U.S. Navy has not previously faced a threat from highly accurate ballistic missiles capable of hitting moving ships at sea. For this reason, some observers have referred to ASBMs as a "game-changing" weapon. Due to their ability to change course, the MaRVs on an ASBM would be more difficult to intercept than nonmaneuvering ballistic missile reentry vehicles.29

DOD has been reporting on the DF-21D in its annual reports to Congress since 2008.30 One observer states that "based on Chinese defense documents, what sets the [DF]-21D apart from the others is that it has a maneuverable re-entry vehicle with synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and optical sensors, which could enable it to hit a moving target."31 According to press reports, the DF-21D has been tested over land but has not been tested in an end-to-end flight test against a target at sea. A January 23, 2013, press report about a test of the weapon in the Gobi desert in western China stated the following:

The People's Liberation Army has successfully sunk a US aircraft carrier, according to a satellite photo provided by Google Earth, reports our sister paper Want Daily—though the strike was a war game, the carrier a mock-up platform and the "sinking" occurred on dry land in a remote part of western China.32

A January 30, 2018, press report states the following:

Media reports suggest that a new variant of China's mighty DF-21D missile has just gone through pre-deployment tests by a specialist brigade of the People's Liberation Army's Rocket Force, and that it has ramped-up assault capabilities that could put an aircraft-carrier strike group out of action.

State broadcaster China Central Television and Sina Military reported that the new missile was "30%" more powerful than the previous-generation DF-21D, but no details of its specifications or the parameters of the tests were provided.

It is believed that the series' launch vehicle has received a big boost to its ability to travel off-road, as compared with the previous model that required support vehicles and would need to park on a huge solid-surface area prior to a launch.

It is not clear if the missile itself has been improved in terms of range or speed.33

On September 3, 2015, at a Chinese military parade in Beijing that displayed numerous types of Chinese weapons, an announcer stated that the DF-26 may have an anti-ship capability.34 The DF-26 has a reported range of 1,800 miles to 2,500 miles, or more than twice the reported range of the DF-21D.35

China reportedly is developing a hypersonic glide vehicle that, if incorporated into Chinese ASBMs, could make Chinese ASBMs more difficult to intercept.36

Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCMs)

Among the most capable of the new ASCMs that have been acquired by China's navy are the Russian-made SS-N-22 Sunburn (carried by China's four Russian-made Sovremenny-class destroyers) and the Russian-made SS-N-27 Sizzler (carried by 8 of China's 12 Russian-made Kilo-class submarines). China's large inventory of ASCMs also includes several indigenous designs, including some highly capable models. DOD states that

China deploys a wide range of advanced ASCMs with the YJ-83 series as the most numerous, which are deployed on the majority of China's ships as well as multiple aircraft. China has also outfitted several ships with YJ-62 ASCMs and claims that the new LUYANG III class DDG and future Type 055 CG will be outfitted with a vertically launched variant of the YJ-18 ASCM. The YJ-18 is a long-range torpedo-tube-launched ASCM capable of supersonic terminal sprint which has likely replaced the older YJ-82 on SONG, YUAN, and SHANG class submarines. China has also developed the long range supersonic YJ-12 ASCM for the H-6 bomber. At China's military parade in September 2015, China displayed a ship-to-ship variant of the YJ-12 called the YJ-12A. China also carries the Russian SS-N-22 SUNBURN on four Russian built SOVREMENNYY-class DDGs and the Russian SS-N-27b SIZZLER on eight Russian built KILO-class submarines.37

DOD also states that

The PLAN continues to emphasize anti-surface warfare (ASUW). Older surface combatants carry variants of the YJ-83 ASCM (65 nm, 120 kilometers (km)), while newer surface combatants such as the LUYANG II DDG are fitted with the YJ-62 (150 nm, 222 km). The LUYANG III DDG and RENHAI CG will be fitted with a variant of China's newest ASCM, the YJ-18 (290 nm, 537 km). Eight of China's 12 KILO SS are equipped with the SS-N-27 ASCM (120 nm, 222 km), a system China acquired from Russia. China's newest indigenous submarine-launched ASCM, the YJ-18 and its variants, represents an improvement over the SS-N-27, and will be fielded on SONG SS, YUAN SSP, and SHANG SSN units.38

Submarines, Mines, and Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs)

Submarines: Overview

China's submarine modernization effort has attracted substantial attention and concern. DOD states, "The PLAN places a high priority on the modernization of its submarine force."39 ONI states that

China has long regarded its submarine force as a critical element of regional deterrence, particularly when conducting "counter-intervention" against modern adversary. The large, but poorly equipped [submarine] force of the 1980s has given way to a more modern submarine force, optimized primarily for regional anti-surface warfare missions near major sea lines of communication.40

Submarine Types Acquired in Recent Years

China since the mid-1990s has acquired 12 Russian-made Kilo-class non-nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSs) and put into service at least four new classes of indigenously built submarines, including the following:

- a new nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) design called the Jin class or Type 094 (Figure 1);

- a new nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) design called the Shang class or Type 093/093A;

- a new SS design called the Yuan class or Type 039A/B/C (Figure 2);41 and

- another (and also fairly new) SS design called the Song class or Type 039/039G.

|

|

Source: Photograph provided to CRS by Navy Office of Legislative Affairs, December 2010. |

|

|

Source: Photograph provided to CRS by Navy Office of Legislative Affairs, December 2010. |

Submarine Capabilities and Armaments

The Kilos and the four new classes of indigenously built submarines are regarded as much more modern and capable than China's previous older-generation submarines. At least some of the new indigenously built designs are believed to have benefitted from Russian submarine technology and design know-how,42 and from knowledge from scientists who had worked at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California before moving back to China.43

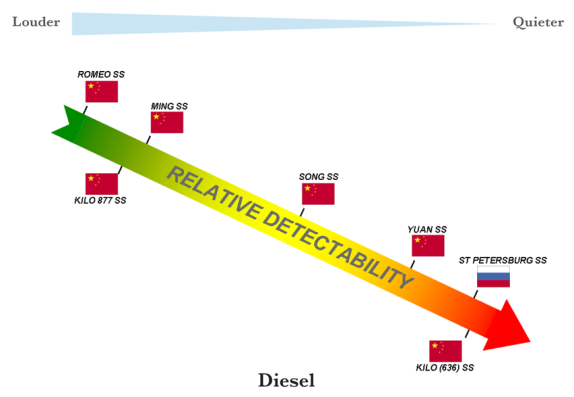

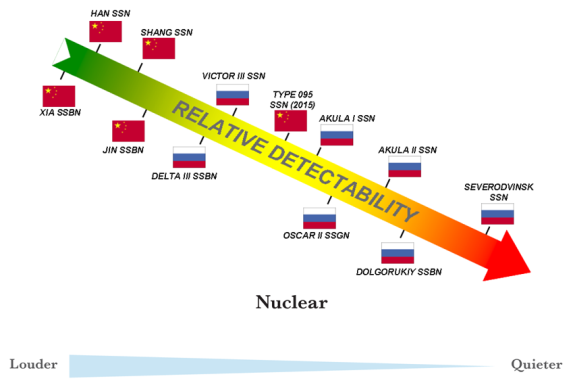

Figure 3 and Figure 4, which are taken from the August 2009 ONI report, show the acoustic quietness of Chinese nuclear- and non-nuclear-powered submarines, respectively, relative to that of Russian nuclear- and non-nuclear-powered submarines. In Figure 3 and Figure 4, the downward slope of the arrow indicates the increasingly lower noise levels (i.e., increasing acoustic quietness) of the submarine designs shown. In general, quieter submarines are more difficult for opposing forces to detect and counter. The green-yellow-red color spectrum on the arrow in each figure might be interpreted as a rough indication of the relative difficulty that a navy with capable antisubmarine warfare forces (such as the U.S. Navy) might have in detecting and countering these submarines: Green might indicate submarines that would be relatively easy for such a navy to detect and counter, yellow might indicate submarines that would be less easy for such a navy to detect and counter, and red might indicate submarines that would be more difficult for such a navy to detect and counter.44

|

Figure 3. Acoustic Quietness of Chinese and Russian Nuclear-Powered Submarines |

|

|

Source: 2009 ONI Report, p. 22. |

China's submarines are armed with one or more of the following: ASCMs, wire-guided and wake-homing torpedoes, and mines.45 Eight of the 12 Kilos purchased from Russia (presumably the ones purchased more recently) are armed with the highly capable Russian-made SS-N-27 Sizzler ASCM. In addition to other weapons, Shang-class SSNs may carry LACMs. Although ASCMs are often highlighted as sources of concern, wake-homing torpedoes are also a concern because they can be very difficult for surface ships to counter.

China has announced that it is developing electric-drive propulsion systems using permanent magnet motors, as well as electrically powered, rim-driven propellers that could help make future Chinese submarines quieter.46

Ballistic Missile Submarines

Regarding ballistic missile submarines, a January 10, 2017, press report states the following:

New photos of China's latest nuclear ballistic missile submarine, the "Jin" Type 094A, hints at a much-improved vessel—one that is larger, with a more pronounced "hump" rear of the sail that lets it carry 12 submarine-launched ballistic missiles.

First seen in late November 2016, the Type 094A differs from the previous four Type 094 SSBNs, what with its curved conning tower and front base that's blended into the submarine hull, possibly to reduce hydrodynamic drag. The Type 094A's conning tower has also removed its windows. Additionally, the Type 094A has a retractable towed array sonar (TAS) mounted on the top of its upper tailfin, which would make it easier for the craft to "listen" for threats and avoid them.

While the original Type 094 is considered to be nosier (and thus less survivable) than its American counterpart (the Ohio-class SSBN), the Type 094A is likely to include acoustic quieting technologies found on the Type 093A.47

Nuclear-Powered Attack Submarines

Regarding nuclear-powered attack submarines, DOD states, "Over the next decade, China probably will construct a new variant of the SHANG class, the Type 093B guided-missile nuclear attack submarines (SSGN), which not only would improve the PLAN's anti-surface warfare capability but might also provide it with a more clandestine land-attack option."48 ONI states that

The SHANG-class SSN's initial production run stopped after only two hulls that were launched in 2002 and 2003. After nearly 10 years, China is continuing production with four additional hulls of an improved variant, the first of which was launched in 2012. These six total submarines will replace the aging HAN class SSN on nearly a one-for-one basis in the next several years. Following the completion of the improved SHANG SSN, the PLA(N) will progress to the Type 095 SSN, which may provide a generational improvement in many areas such as quieting and weapon capacity.49

A June 27, 2016, blog post states the following:

Is China's new Type 093B nuclear-powered attack submarine on par with the U.S. Navy's Improved Los Angeles-class boats?

At least some U.S. naval analysts believe so and contend that the introduction of the new People's Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) submarines is an indication of just how quickly Beijing is catching up to the West.

"The 93B is not to be confused with the 93. It is a transition platform between the 93 and the forthcoming 95," said Jerry Hendrix, director of the Defense Strategies and Assessments Program at the Center for a New American Security—who is also a former U.S. Navy Captain. "It is quieter and it has a new assortment of weapons to include cruise missiles and a vertical launch capability. The 93B is analogous to our LA improved in quietness and their appearance demonstrates that China is learning quickly about how to build a modern fast attack boat."

Other sources were not convinced that Beijing could have made such enormous technological strides so quickly—but they noted that the topic of Chinese undersea warfare capability is very classified. Open source analysis is often extremely difficult, if not impossible. "Regarding the question on the Type 093B, I really don't know, anything is possible I suppose, but I doubt it," said retired Rear Adm. Mike McDevitt, now an analyst at CNA's Center for Naval Analyses. "I have no doubt that the PLAN has ambitions to at least achieve that level of capability and quietness."50

A February 4, 2018, press report states that

China is working to update the rugged old computer systems on nuclear submarines with artificial intelligence to enhance the potential thinking skills of commanding officers, a senior scientist involved with the programme told the South China Morning Post.

A submarine with AI-augmented brainpower not only would give China's large navy an upper hand in battle under the world's oceans but would push applications of AI technology to a new level, according to the researcher, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the project's sensitivity....

Joe Marino, CEO of Rite-Solutions, a technical company supporting the US Naval Undersea System Command, touted the value of using AI to enhance submarine commanding officers' decision-making powers.

"[Without matching other countries' advances in AI submarine technology] our CO (commanding officers) would be fighting an opponent who could make faster, more informed and better decisions," Marino wrote in an article on the company's website.

"Combined with undersea technology advancements by near-peer competitors such as Russia and China in areas such as stealth, sensors, weapons, this 'cognitive advantage' could threaten US undersea dominance," he wrote.51

Non-Nuclear-Powered Attack and Auxiliary Submarines

Some of China's newer non-nuclear-powered submarines reportedly are equipped with so-called air-independent propulsion (AIP) systems.52 Examples of AIP systems include fuel cells, Sterling engines, and close-cycle diesel engines. In comparison with traditional non-nuclear-powered submarines (i.e., diesel-electric submarines), which generally have a low-speed or stationary submerged endurance of a few days, AIP-equipped non-nuclear-powered submarines reportedly can have a low-speed or stationary submerged endurance of perhaps up to two or three weeks. (At high submerged speeds, both traditional and AIP-equipped non-nuclear-powered submarines drain their batteries quickly and consequently have a high-speed submerged endurance of perhaps a few hours.)

A January 5, 2017, press report states the following:

Images posted on Chinese online forums in December show three new Yuan-class (Type 039B) patrol submarines being fitted out in the water at the Wuchang Shipyard in Wuhan, central China: a clear indication that China has resumed production of these diesel-electric boats after a near-three-year hiatus.

The latest of the three submarines appears to have been launched around 12 December, [2016] according to online forums.53

Although China's aged Ming-class (Type 035) submarines are based on old technology and are much less capable than China's newer-design submarines, China may decide that these older boats have continued value as minelayers or as bait or decoy submarines that can be used to draw out enemy submarines (such as U.S. SSNs) that can then be attacked by other Chinese naval forces.

China in 2012 commissioned into a service a new type of non-nuclear-powered submarine, called the Type 032 or Qing class according to IHS Jane's Fighting Ships 2017-2018, that is about one-third larger than the Yuan-class design. Observers believe the boat may be a one-of-kind test platform; IHS Jane's Fighting Ships 2017-2018 refers to it as an auxiliary submarine (SSA).54

A June 29, 2015, press report showed a 2014 satellite photograph of an apparent Chinese mini- or midget-submarine submarine that "has not been seen nor heard of since."55

Submarine Acquisition Rate and Potential Submarine Force Size

Table 1 shows actual and projected commissionings of Chinese submarines by class since 1995, when China took delivery of its first two Kilo-class boats. The table includes the final nine boats in the Ming class, which is an older and less capable submarine design.

|

Jin (Type 094) SSBN |

Shang (Type 093/ 093A) SSN |

Kilo SS (Russian-made) |

Ming (Type 035) SSa |

Song (Type 039/039G) |

Yuan (Type 039A/B/C) SSb |

Qing (Type 032) SS |

Annual total for all types shown |

Cumulative total for all types shown |

Cumulative total for modern attack boatsc |

|

|

1995 |

2d |

1 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

|||||

|

1996 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

||||||

|

1997 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

7 |

3 |

|||||

|

1998 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

10 |

4 |

|||||

|

1999 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

5 |

||||||

|

2000 |

1 |

1 |

12 |

5 |

||||||

|

2001 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

15 |

7 |

|||||

|

2002 |

1 |

1 |

16 |

7 |

||||||

|

2003 |

2 |

2 |

18 |

9 |

||||||

|

2004 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

22 |

13 |

|||||

|

2005 |

6 |

3 |

9 |

31 |

22 |

|||||

|

2006 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

36 |

27 |

|||

|

2007 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

38 |

28 |

|||||

|

2008 |

0 |

38 |

28 |

|||||||

|

2009 |

2 |

2 |

40 |

30 |

||||||

|

2010 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

42 |

31 |

|||||

|

2011 |

3 |

3 |

45 |

34 |

||||||

|

2012 |

1 |

5 |

1e |

7 |

52 |

39 |

||||

|

2013 |

0 |

52 |

39 |

|||||||

|

2014 |

0 |

52 |

39 |

|||||||

|

2015 |

1 |

2f |

3 |

55 |

41 |

|||||

|

2016 |

2h |

2 |

57 |

43 |

||||||

|

2017 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|||||

|

2018 |

1g |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

||||

|

2019 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Source: IHS Jane's Fighting Ships 2017-2018, and (for Ming class) previous editions.

Note: n/a = data not available.

a. Figures for Ming-class boats are when the boats were launched (i.e., put into the water for final construction). Actual commissioning dates for these boats may have been later.

b. Some sources refer to the Yuan class as the Type 041.

c. This total excludes the Jin-class SSBNs (because they are not attack boats), the Ming-class SSs (because they are generally considered to not be of a modern design), and the Qing-class boat (because IHS Jane's considers it to be an auxiliary submarine).

d. IHS Jane's Fighting Ships 2017-2018 lists the commissioning date of one of the two Kilos as November 15, 1994.

e. Observers believe this boat may be a one-of-kind test platform; IHS Jane's Fighting Ships 2017-2018 refers to it as an auxiliary submarine (SSA).

f. IHS Jane's Fighting Ships 2017-2018 states that a class of 20 boats is expected.

g. IHS Jane's Fighting Ships 2017-2018 states that a total of five boats are expected, with the final four boats built to a modified (Type 093A) design.

h. IHS Jane's Fighting Ships 2017-2018 states that a total of six boats is expected.

As shown in Table 1, China by the end of 2016 was expected to have a total of 43 relatively modern attack submarines—meaning Shang-, Kilo-, Yuan-, and Song-class boats—in commission. As shown in the table, much of the growth in this figure occurred in 2004-2006, when 18 attack submarines (including 8 Kilo-class boats and 8 Song-class boats) were added, and in 2011-2012, when 8 Yuan-class attack submarines were added.

The figures in Table 1 show that between 1995 and 2016, China was expected to place into service a total of 57 submarines of all kinds, or an average of about 2.6 submarines per year. This average commissioning rate, if sustained indefinitely, would eventually result in a steady-state submarine force of about 52 to 78 boats of all kinds, assuming an average submarine life of 20 to 30 years. A May 16, 2013, press report quotes Admiral Samuel Locklear, then-Commander of U.S. Pacific Command, as stating that China plans to acquire a total of 80 submarines.56

As shown in Table 1, most of the submarines built in China have been non-nuclear-powered submarines. By contrast, as shown in the first two data columns of Table 1, China has built nuclear-powered submarines in small numbers and at annual rates of less than one per year.

Excluding the 12 Kilos purchased from Russia, the total number of domestically produced submarines placed into service between 1995 and 2016 is 44, or an average of 2.05 per year. This average rate of domestic production, if sustained indefinitely, would eventually result in a steady-state force of domestically produced submarines of about 41 to 61 boats of all kinds, again assuming an average submarine life of 20 to 30 years.

Projections of potential the size of China's submarine force in 2020 include the following:

- DOD states that "By 2020, [China's submarine] force will likely grow to between 69 and 78 submarines."57

- ONI stated in 2015 that "by 2020, the [PLA(N)] submarine force will likely grow to more than 70 submarines."58 In an accompanying table, ONI provided a more precise projection of 74 submarines in 2020, including 11 nuclear-powered boats and 63 non-nuclear-powered boats.59

- An October 4, 2017, blog post from two nongovernment observers projects that China's submarine force in 2020 will include a total of 58 boats, including four Jin-class (Type-094) SSBNs, six Shang-class SSNs (two Type 093 and four Type 093A), and 48 SSs (20 Yuan-class boats, 12 Song-class boats, 12 Kilo-class boats, and four Ming-class boats).60

JL-2 SLBM on Jin-Class SSBN

A December 9, 2015, press report stated that China had sent a Jin-class SSBN out on its first deterrent patrol.61 Each Jin-class SSBN is expected to be armed with 12 JL-2 nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). DOD states that

China's four operational JIN-class SSBNs represent China's first credible, sea-based nuclear deterrent. China's next-generation Type 096 SSBN, will likely begin construction in the early-2020s, and reportedly will be armed with the JL-3, a follow-on SLBM.62

A range of 7,400 km for the JL-2 SLBM could permit Jin-class SSBNs to attack

- targets in Alaska (except the Alaskan panhandle) from protected bastions close to China;

- targets in Hawaii (as well as targets in Alaska, except the Alaskan panhandle) from locations south of Japan;

- targets in the western half of the 48 contiguous states (as well as Hawaii and Alaska) from midocean locations west of Hawaii; and

- targets in all 50 states from midocean locations east of Hawaii.

China reportedly is developing a new SLBM, potentially to be called the JL-3, as a successor to the JL-2.63

Mines

China has modernized its substantial inventory of naval mines.64 ONI states that

China has a robust mining capability and currently maintains a varied inventory estimated at more than 50,000 [naval] mines. China has developed a robust infrastructure for naval mine-related research, development, testing, evaluation, and production. During the past few years, China has gone from an obsolete mine inventory, consisting primarily of pre-WWII vintage moored contact and basic bottom influence mines, to a vast mine inventory consisting of a large variety of mine types such as moored, bottom, drifting, rocket-propelled, and intelligent mines. The mines can be laid by submarines (primarily for covert mining of enemy ports), surface ships, aircraft, and by fishing and merchant vessels. China will continue to develop more advanced mines in the future such as extended-range propelled-warhead mines, antihelicopter mines, and bottom influence mines more able to counter minesweeping efforts.65

Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs)

A July 26, 2017, press report states that "China is testing large-scale deployment of underwater drones in the South China Sea with real-time data transmission technology, a breakthrough that could help reveal and track the location of foreign submarines." The report describes the work as an "effort by China to speed up and improve collection of dee-sea data in the South China Sea for its submarine fleet operation...."66

Aircraft Carriers and Carrier-Based Aircraft67

Overview

China's first aircraft carrier entered service in 2012. China's second aircraft carrier (and its first indigenously built carrier) was launched (i.e., put into the water for the final stages of construction) in April 2017 and reportedly began sea trials in April 2018. China reportedly has begun construction of a third aircraft carrier. Observers speculate China may eventually field a force of four to six aircraft carriers.68 In September 2017, it was reported that China had hired a retired Ukrainian national whose prior work experience includes having assisted the Soviet Union's efforts in building aircraft carriers.69

First Carrier: Liaoning (Type 001)

On September 25, 2012, China commissioned into service its first aircraft carrier—the Liaoning or Type 001 design (Figure 5), a refurbished ex-Ukrainian aircraft carrier, previously named Varyag, that China purchased from Ukraine in 1998 as an unfinished ship.70

The Liaoning is conventionally powered, has an estimated full load displacement of almost 60,000 tons,71 and might accommodate an eventual air wing of 30 or more aircraft, including fixed-wing airplanes and helicopters. A September 7, 2014, press report, citing an August 28, 2014, edition of the Chinese-language Shanghai Morning Post, stated that the Liaoning's air wing may consist of 24 J-15 fighters, 6 anti-submarine warfare helicopters, 4 airborne early warning helicopters, and 2 rescue helicopters, for a total of 36 aircraft.72 The Liaoning lacks aircraft catapults and instead launches fixed-wing airplanes off the ship's bow using an inclined "ski ramp."

|

|

Source: "Highlights of Liaoning Carrier's One-Year Service," China Daily, September 26, 2013, accessed September 30, 2013, at http://www.china.org.cn/china/2013-09/26/content_30142217.htm. This picture shows the ship during a sea trial in October 2012. |

By comparison, a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier is nuclear powered (giving it greater cruising endurance than a conventionally powered ship), has a full load displacement of about 100,000 tons, can accommodate an air wing of 60 or more aircraft, including fixed-wing aircraft and some helicopters, and launches its fixed-wing aircraft over both the ship's bow and its angled deck using catapults, which can give those aircraft a range/payload capability greater than that of aircraft launched with a ski ramp. The Liaoning, like a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, lands fixed-wing aircraft using arresting wires on its angled deck. Some observers have referred to the Liaoning as China's "starter" carrier.73 DOD states that "When fully operational, Liaoning will be less capable than the U.S. Navy's NIMITZ-class carriers in projecting power. Its smaller size limits the number of aircraft it can embark and the ski-jump configuration limits aircraft fuel and ordnance loads."74 ONI states that

LIAONING is quite different from the U.S. Navy's NIMITZ-class carriers. First, since LIAONING is smaller, it will carry far fewer aircraft in comparison to a U.S.-style carrier air wing. Additionally, the LIAONING's ski-jump configuration significantly restricts aircraft fuel and ordnance loads. Consequently, the aircraft it launches have more a limited flight radius and combat power. Finally, China does not yet possess specialized supporting aircraft such as the E-2C Hawkeye.75

The PLA Navy is currently learning to operate aircraft from the ship. ONI states that "full integration of a carrier air regiment remains several years in the future, but remarkable progress has been made already,"76 and that "it will take several years before Chinese carrier-based air regiments are operational."77 A September 2, 2015, press report states that "China's aircraft carrier Liaoning can carry at least 20 fixed-wing carrier-based J-15 fighter jets and the ratio between the pilots and planes is about 1.5:1. So China needs to train more pilots for the future aircraft carrier, said a military expert recently."78

In November 2016, the ship was reportedly described as being ready for combat.79 An October 26, 2017, press report states that "despite its inauguration in 2012, it appears the vessel's genuine war-readiness is still in doubt."80

Second Carrier: Type 001A

China's second aircraft carrier (and its first indigenously built carrier), referred to as the Type 001A design (Figure 6), was launched (i.e., put into the water for the final stages of construction) on April 26, 2017,81 and reportedly began its first sea trial on April 23, 2018, a date that observers noted was the anniversary of establishment of the PLAN.82

The ship—which reportedly might be given the name Shandong, for the Chinese province—is thought to be a modified version of the Liaoning design that incorporates some design improvements. A December 11, 2017, press report states that the ship may embark up to 35 J-15 carrier-based fighters, as opposed to 24 on the Liaoning.83

Third Carrier (Type 002) and Subsequent Carriers

As stated earlier, observers speculate China may eventually field a force of four to six aircraft carriers, meaning Liaoning, the Type 001A carrier, and two to four additional carriers. Press reports state that China's third and subsequent carriers may use catapults rather than ski ramps, that the catapults might be new-technology electromagnetic catapults rather than traditional steam-powered catapults, and that at least some of the ships might be nuclear-powered rather than conventionally powered.

A March 1, 2018, press report states the following:

One of China's largest shipbuilders has revealed plans to speed up the development of China's first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, as part of China's ambition to transform its navy into a blue-water force by the middle of the next decade.

In a since-amended news release outlining the company's future strategic direction in all of its business areas, the state-owned China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation, or CSIC, said the shipbuilding group will redouble efforts to achieve technological breakthroughs in nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, new nuclear-powered submarines, quieter conventionally powered submarines, underwater artificial intelligence-based combat systems and integrated networked communications systems....

The company release added that these breakthroughs are required for China's People's Liberation Army Navy, or PLAN, to enhance its capability to globally operate in line with the service's aim to become a networked, blue-water navy by 2025.

The original news release, which Defense News has seen and translated, has since been deleted from CSIC's website and replaced by one missing all references to the details listed above.84

Another March 1, 2018, press report states the following:

China is ready to build larger aircraft carriers having mastered the technical ability to do so, a major state-run newspaper said on Friday [March 2] ahead of the release of the country's annual defense budget....

Liu Zheng, chairman of Dalian Shipbuilding Industry in Liaoning province, said his company and its parent, China Shipbuilding Industry Corp, the world's largest shipbuilder, could design and build carriers.

"We have complete ownership of the expertise, in terms of design, technology, technique, manufacturing and project management, that is needed to make an advanced carrier," Liu told the official China Daily ahead of Monday's opening of the annual session of parliament.

"We are ready to build larger ones," he said.

China Shipbuilding said earlier this week they were developing technologies to build a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.85

A January 19, 2018, press report states the following:

China's third aircraft carrier is under construction and will likely see several technological improvements over the country's first two. The ship, known for now only as 002, has been under construction since 2015. The new carrier will likely be larger than her predecessors and sport an electromagnetic launch system for aircraft, allowing for larger, heavier aircraft to conduct longer distance flights with more weaponry....

The third aircraft carrier, 002, began construction in March 2015 at the Jiangnan Changxingdao Shipyard in Shanghai. The first two ships were studied and built as learning experiences with minimal changes or improvements. The third ship, however, is expected to be substantially different.

One of the major differences between the three carriers is size. The first carrier, Liaoning, was locked into the size of the existing 67,000 ton hull. The second carrier is expected to be about the same size, as China learned how to make a copy of an aircraft carrier. The third carrier is expected to tip the scales at about 80,000 tons, and 002 will also likely be slightly longer than Liaoning's 999 feet.

A larger carrier will mean several things. 002 will carry more fuel, both for its aircraft and itself, enabling the carrier to operate farther from China and the aircraft to fly more sorties from the carrier. The newer, larger carrier will also have more room for aircraft, both in the hangar and on the flight deck itself. The second carrier, 001A, has a smaller island than Liaoning, freeing up deck space, and 002 will likely shrink her island even more.

As a result, the carrier's air wing can be expected to grow substantially larger. Liaoning can carry up to 24 Shenyang J-15 "Flying Shark" multi-role fighters, while 001A will probably increase that to 30 J-15s. 002's air wing could grow to 40 fighters plus a handful of propeller-driven carrier onboard delivery transports and airborne early warning aircraft....

Another major difference is that, unlike Liaoning and 001A, 002 is expected ditch the bow-mounted ski ramp and use an aircraft catapult launching system....

China is reportedly skipping over steam-driven aircraft catapults to instead build an electromagnetic aircraft launching system (EMALS), similar to that recently put into service on the U.S. Navy's newest carrier, USS Gerald R. Ford. A report from Defense News in November 2017 stated that Chinese leader Xi Jinping had wanted EMALS installed on 002, but engineers couldn't reconcile a conventional power plant with the huge power demands of the electromagnetic launch system. Chinese naval engineers have now apparently solved the power issue....

002 will undoubtedly come with other improvements. A more robust air defense weapons suite is likely, with close-in weapons such as the HQ-10 Flying Leopard short-range air defense system similar to the American RIM-116 Rolling Airframe Missile (RAM). Passive anti-missile and anti-torpedo defenses will be expanded to give the ship a fighting chance under attack. Expanded medical and water desalination capabilities, already a necessity, could make the ship useful in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief missions as American carriers already are.86

A January 4, 2018 press report updated on January 5, 2018, states the following:

China started building its third aircraft carrier, with a hi-tech launch system, at a Shanghai shipyard last year, according to sources close to the People's Liberation Army.

One of the sources said Shanghai Jiangnan Shipyard Group was given the go-ahead to begin work on the vessel after military leaders met in Beijing following the annual sessions of China's legislature and top political advisory body in March.

"But the shipyard is still working on the carrier's hull, which is expected to take about two years," the source said. "Building the new carrier will be more complicated and challenging than the other two ships."...

The sources all said it was too early to say when the third vessel would be launched, but China plans to have four aircraft carrier battle groups in service by 2030, according to naval experts.

Shipbuilders and technicians from Shanghai and Dalian are working on the third vessel, which will have a displacement of about 80,000 tonnes – 10,000 tonnes more than the Liaoning, according to another source close to the PLA Navy.

"China has set up a strong and professional aircraft carrier team since early 2000, when it decided to retrofit the Varyag [the unfinished vessel China bought from Ukraine] to launch as the Liaoning, and it hired many Ukrainian experts ... as technical advisers," the second source said.

The sources also confirmed that the new vessel, the CV-18, will use a launch system that is more advanced than the Soviet-designed ski-jump systems used in its other two aircraft carriers.

Its electromagnetic aircraft launch system will mean less wear and tear on the planes and it will allow more aircraft to be launched in a shorter time than other systems....

Sources said the layout of the new aircraft carrier, including its flight deck and "island" command centre, would be different from the other two.

"The new vessel will have a smaller tower island than the Liaoning and its sister ship because it needs to accommodate China's carrier-based J-15 fighter jets, which are quite large," the first source said.87

A March 15, 2018, press report states that following the Type 002 carrier design, China will begin building a Type 003 carrier design:

The biggest item in CSIC's [China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation's] not-so-secret portfolio is China's first nuclear-powered carrier. Popularly identified as the Type 003, it will be the largest non-American warship in the world when its launched in the late 2020s. CSIC's Dalian Shipyard, which refurbished the aircraft carrier Liaoning, and launched China's first domestically built carrier, CV-17, in 2017, will presumably build China's first "Type 003" CVN.

The Type 003 will displace between 90,000-100,000 tons and have electromagnetically assisted launch system (EMALS) catapults for getting aircrafts off the deck. It'll likely carry a large air wing of J-15 fighters, J-31 stealth fighters, KJ-600 airborne early warning and control aircraft, anti-submarine warfare helicopters, and stealth attack drones.88

Carrier-Based Aircraft

China has developed a carrier-capable fighter, called the J-15 or Flying Shark, that can operate from the Liaoning (Figure 7).

|

|

Source: Zachary Keck, "China's Carrier-Based J-15 Likely Enters Mass Production," The Diplomat (http://thediplomat.com), September 14, 2013. |

DOD states that the J-15 is "modeled after the Russian Su-33 [Flanker]," and that "although the J-15 has a land-based combat radius of 1,200 km, the aircraft will be limited in range and armament when operating from the carrier, because the ski-jump design does not provide as much airspeed and, therefore, lift at takeoff as a catapult design."89

A February 1, 2107, press report speculates that China may be developing a carrier-based airborne early warning and control aircraft broadly similar to the U.S. Navy's E-2 Hawkeye carrier-based airborne early warning and control aircraft.90

A November 19, 2017, press report states the following:

China spent more than a decade developing its first carrier-based fighter, the J-15, based on a prototype of a fourth-generation Russian Sukhoi Su-33 twin-engined air superiority fighter—a design that is now more than 30 years old.

The J-15, with a maximum take-off weight of 33 tonnes, is the heaviest active carrier-based fighter jet in the world but the sole carrier-based fighter in the People's Liberation Army Navy....

"The maximum take-off weight of the J-15 fighter is 33 tonnes and experiments found that even the US Navy's new generation C13-2 steam catapult launch engines, installed on Nimitz-class aircraft carriers, would struggle to launch the aircraft efficiently," the source, who requested anonymity, said.

The US Navy also relied on a heavy carrier-based fighter in the past, the 33.7 tonne F-14 Tomcat. But they were replaced by the lighter F-18 Super Hornet in 2006 after 32 years of service. The maximum take-off weight of an F-18 Super Hornet is 29.9 tonnes according to the website of manufacturer Boeing.

China has been trying to develop a new generation carrier-based fighter, the FC-31, with a maximum take-off weight of 28 tonnes, to replace the J-15, and put J-15 chief designer Sun Cong in charge of the project.

Pictures posted on mainland military websites show that Shenyang Aircraft Corporation, the manufacturer of the J-15, has produced two FC-31 prototypes, with one debuting at the Zhuhai air show in 2014.

However, the two military sources said, the development of the FC-31 had not proceeded smoothly and it had failed to meet the PLA Navy's requirements, with the key obstacle being what one described as "heart disease".

"China is still incapable of developing an engine for the FC-31 fighter," the first source said. "The FC-31 has needed to be equipped with Russian RD-93 engines for test flights."

The second source said the FC-31's failure to meet the PLA Navy's basic requirements for a new generation fighter meant "that in the next two decades, the J-15 will still be the key carrier-based fighter on China's aircraft carriers".91

A December 6, 2017, press report states the following:

China's future straight-deck aircraft carriers with the electromagnetic launcher system will carry fifth-generation jet fighters like [the] J-20 and J-31, Chinese experts said on Wednesday [December 6]....

The J-20 and J-31 will surely be installed on future Chinese aircraft carriers with the catapult system, to protect the carriers, Yin Zhuo, a senior researcher at the PLA Naval Equipment Research Center, told the Military Time.

Yin predicted the J-15 fighters on the Type 001A will be around 40, about the same as that for Liaoning ship.

Song Zhongping, a TV commentator and military expert, told the Global Times that "It is more likely that J-15 fighters and improved versions will be on board together with stealth fighters such as the J-20 and J-31, as they will be playing different roles."

However, Song pointed out that since the J-20 and J-31 are primarily designed for the air force, adapting them as navy fighters will entail some costs. "The J-20 will be more expensive to modify than the J-31."92

A January 23, 2018, press report states the following:

China's carrier aviation programs continue apace with the focus starting to shift toward the development and introduction of training and specialized aircraft as China's first domestically built carrier approaches the start of sea trials....

Currently, the PLAN only has a single type of fixed-wing carrierborne aircraft in service. This is the Shenyang J-15 Flying Shark multirole fighter....

Approximately two dozen J-15s have been produced so far in two production batches, and these are currently only able to operate from the ski jump-equipped Liaoning aircraft carrier and the Type 002 carrier being fitted out in the city of Dalian.

China is known to have at least one of the six J-15 prototypes fitted with catapult launch accessories on its nose landing gear, and the country is carrying out catapult tests with this aircraft, using what are believed to be a steam catapult and EMALS at an air base near Huludao, Liaoning province in northern China.

In addition, China is developing a twin-seat variant of the J-15, with at least a single prototype known to be flying from Shenyang Aircraft Corporation's facilities located in its namesake city. It is likely this variant, designated the J-15S, will operate from the future, catapult-equipped carrier China will build after the Type 002 as a two-seat multirole fighter alongside single-seat J-15s, much like the mix of single-seat Boeing F/A-18E Super Hornets and twin-seat F/A-18Fs onboard a typical U.S. Navy carrier air wing.

Future production batches of J-15s are also expected to be fitted with more modern avionics, such as those already fitted to the J-16 fighter that will included an active electronically scanned array radar.

The electronic warfare/electronic attack technology being developed for a specialized variant of the J-16 may also be introduced on the J-15.

However, these are unlikely to be fielded in the near term, but rather are expected to enter service in the early part of the next decade, at the earliest....

The PLAN is also revamping its pilot training program with the intention of streamlining the process of training its pilots. The service sees an urgent need for 400 new pilots in the coming years with the introduction of new land- and carrier-based aircraft types....

However, the PLAN lacks a dedicated trainer aircraft used to qualify carrier pilots, with the J-15 currently being used in this role. An attempt was made to develop a carrier trainer version of the JL-9 for this purpose, but this was unsuccessful; reports suggest the JL-9's fuselage was unable to cope with the stress involved in arrested landings onboard carriers....

As Defense News previously reported, if China were to build its third carrier equipped with an EMALS as expected, the PLAN will be able to operate a wider variety of aircraft from its carriers, opening up the possibility of equipping its air wings with an aircraft similar to the Northrop Grumman E-2 Hawkeye airborne early-warning aircraft.

The PLAN's current shipboard airborne early-warning asset is the Changhe Z-8 helicopter fitted with a radar that can be stowed when not in use....

China previously built a mock-up of a Xi'an Y-7 with a heavily modified tailplane and a radar rotodome on top of its fuselage around the year 2010. Yet, there has been no further development of that project since then.

A similar mock-up was seen on the carrier flight deck test bed at a naval testing facility in Wuhan, Hubei province, in early 2017, indicating that China is still interested in developing such a platform.93

Press reports dated April 3 and 4, 2018, stated that China is developing carrier based UAVs.94

Potential Roles, Missions, and Strategic Significance

Although aircraft carriers might have some value for China in Taiwan-related conflict scenarios, they are not considered critical for Chinese operations in such scenarios, because Taiwan is within range of land-based Chinese aircraft. Consequently, most observers believe that China is acquiring carriers primarily for their value in other kinds of operations, and to demonstrate China's status as a leading regional power and major world power.

Chinese aircraft carriers could be used for power-projection operations, particularly in scenarios that do not involve opposing U.S. forces, and to impress or intimidate foreign observers.95 Chinese aircraft carriers could also be used for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR) operations, maritime security operations (such as antipiracy operations), and noncombatant evacuation operations (NEOs). Politically, aircraft carriers could be particularly valuable to China for projecting an image of China as a major world power, because aircraft carriers are viewed by many as symbols of major world power status. In a combat situation involving opposing U.S. naval and air forces, Chinese aircraft carriers would be highly vulnerable to attack by U.S. ships and aircraft,96 but conducting such attacks could divert U.S. ships and aircraft from performing other missions in a conflict situation with China.97

DOD states that

Liaoning will probably focus on fleet air defense missions, extending air cover over a fleet operating far from land-based coverage. It probably also will play a significant role in developing China's carrier pilots, deck crews, and tactics for future carriers.98

DOD also states that

Last year, China continued to learn lessons from operating its first aircraft carrier, Liaoning, while constructing its first domestically produced aircraft carrier—the beginning of what the PLA states will be a multi-carrier force. China's next generation of carriers will probably have greater endurance and be capable of launching more varied types of aircraft, including EW, early warning, and ASW aircraft. These improvements would increase the potential striking power of a potential "carrier battle group" in safeguarding China's interests in areas beyond its immediate periphery; it would also be able to protect nuclear ballistic missile submarines stationed on Hainan Island in the South China Sea. The carriers would most likely also perform such missions as patrolling economically important SLOCs, conducting naval diplomacy, regional deterrence, and HA/DR operations.99

ONI states that

Unlike a U.S. carrier, LIAONING is not well equipped to conduct long-range power projection. It is better suited to fleet air defense missions, where it could extend a protective envelope over a fleet operating in blue water. Although it possesses a full suite of weapons and combat systems, LIAONING will likely offer its greatest value as a long-term training investment.100

Navy Surface Combatants and Coast Guard Cutters101

Overview

China since the early 1990s has purchased four Sovremenny-class destroyers from Russia and put into service 10 new classes of indigenously built destroyers and frigates (some of which are variations of one another) that demonstrate a significant modernization of PLA Navy surface combatant technology. DOD states that "The PLAN also remains engaged in a robust surface combatant construction program that will provide a significant upgrade to the PLAN's air defense capability. These assets will be critical as the PLAN expands operations into distant seas beyond the range of shore-based air defense systems."102 ONI states that

In recent years, shipboard air defense is arguably the most notable area of improvement on PLA(N) surface ships. China has retired several legacy destroyers and frigates that had at most a point air defense capability, with a range of just several miles. Newer ships entering the force are equipped with medium-to-long range area air defense missiles.103

China is also building a new class of cruiser (or large destroyer) and a new class of corvettes (i.e., light frigates), and previously put into service a new kind of missile-armed fast attack craft that uses a stealthy catamaran hull design. ONI states, "The JIANGKAI-class (Type 054A) frigate series, LUYANG-class (Type 052B/C/D) destroyer series, and the upcoming new cruiser (Type 055) class are considered to be modern and capable designs that are comparable in many respects to the most modern Western warships."104

A June 1, 2017, press report states that China is exploring potential design concepts for submersible or semi-submersible arsenal ships—ships equipped with large numbers of missiles that that could operate with part or most of their hulls below the waterline so as to reduce their detectability.105

China is also building substantial numbers of new cutters for the China Coast Guard (CCG), which China often uses for asserting and defending its maritime territorial claims in the East and South China Seas. In terms of numbers of ships being built and put into service, production of corvettes for China's navy and cutters for the CCG are currently two of China's most active areas of noncommercial shipbuilding. Russia reportedly has assisted China's development of new surface warfare capabilities.106

New Renhai (Type 055) Cruiser (or Large Destroyer)