Defense Spending Under an Interim Continuing Resolution: In Brief

Changes from December 15, 2017 to December 26, 2017

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Defense Spending Under an Interim Continuing Resolution: In Brief

Contents

- Background

- Full Text Versus Formulaic Continuing Appropriations

- Limitations that Continuing Resolutions May Impose

- Anomalies

- How Agencies Implement a CR

- Unique Implementation Challenges Faced by DOD

- Prohibitions on Certain Contracting Actions

- Misalignments in CR-Provided Funding

- Timing of the NDAA

- DOD Management Challenges Under a CR

- Managing with an Expectation of a CR

Summary

This report provides a basic overview of interim continuing resolutions (CRs) and highlights some specific issues pertaining to operations of the Department of Defense (DOD) under a CR.

As with regular appropriations bills, Congress can draft a CR to provide funding in many different ways. Under current practice, a CR is an appropriation that provides either interim or full-year funding by referencing a set of established funding levels for the projects and activities that it funds (or covers). Such funding may be provided for a period of days, weeks, or months and may be extended through further continuing appropriations until regular appropriations are enacted, or until the fiscal year ends. In recent fiscal years, the referenced funding level on which interim or full-year continuing appropriations has been based was the amount of budget authority that was available under specified appropriations acts from the previous fiscal year.

CRs may also include provisions that enumerate exceptions to the duration, amount, or purposes for which those funds may be used for certain appropriations accounts or activities. Such provisions are commonly referred to as anomalies. The purpose of anomalies is to preserve Congress's constitutional prerogative to provide appropriations in the manner it sees fit, even in instances when only interim funding is provided.

The lack of a full-year appropriation and the uncertainty associated with the temporary nature of a CR can create management challenges for federal agencies. DOD faces unique challenges operating under a CR while providing the military forces needed to deter war and defend the country. For example, an interim CR may prohibit an agency from initiating or resuming any project or activity for which funds were not available in the previous fiscal year (i.e., prohibit new starts). Such limitations in recent CRs have affected a large number of DOD programs. Before the beginning of FY2018, DOD identified approximately 75 weapons programs that would be delayed by the FY2018 CR's prohibition on new starts and nearly 40 programs that would be affected by a restriction on production quantity.

In addition, Congress may include provisions in interim CRs that place limits on the expenditure of appropriations for programs that spend a relatively high proportion of their funds in the early months of a fiscal year. Also, if a CR provides funds at the rate of the prior year's appropriation, an agency may be provided additional (even unneeded) funds in one account, such as research and development, while leaving another account, such as procurement, underfunded.

By its very nature, an interim CR can prevent agencies from taking advantage of efficiencies through bulk buys and multiyear contracts. It can foster inefficiencies by requiring short-term contracts that must be reissued once additional funding is provided, requiring additional or repetitive contracting actions.

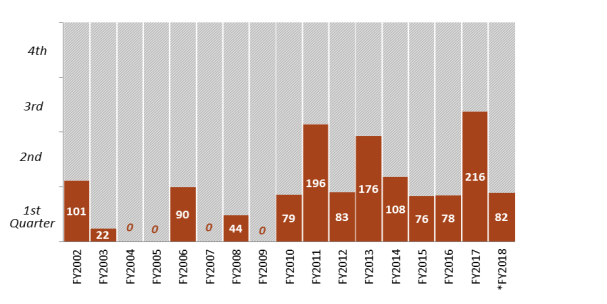

DOD has started the fiscal year under a CR for 13 of the past 17 years (FY2002-FY2018) and every year since FY2010. The amount of time DOD has operated under CR authorities during the fiscal year has increased in the past 9 years and equates to a total of more than 3536 months since 2010.

Background

Congress uses an annual appropriations process to fund the routine activities of most federal agencies. This process anticipates the enactment of 12 regular appropriations bills to fund these activities before the beginning of the fiscal year. When this process is delayed beyond the start of the fiscal year, one or more continuing appropriations acts (commonly known as continuing resolutions or CRs) can be used to provide funding until action on regular appropriations is completed.

|

What's a "CR"? Continuing appropriations acts are commonly referred to as "continuing resolutions" because they usually provide continuing appropriations in the form of a joint resolution rather than a bill. However, continuing appropriations are also occasionally provided through a bill. For further information on the annual appropriations process and additional background on congressional practice related to CRs, see CRS Report R42388, The Congressional Appropriations Process: An Introduction and CRS Report R42647, Continuing Resolutions: Overview of Components and Recent Practices, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

An interim continuing resolution (CR) typically provides that budget authority is available at a certain rate of operations or funding rate for the covered projects and activities, and for a specified period of time. The funding rate for a project or activity is based on the total amount of budget authority that would be available annually at the referenced funding level, and is prorated based on the fraction of a year for which the interim CR is in effect.

In recent fiscal years, the referenced funding level has been the amount of budget authority that was available under specified appropriations acts from the previous fiscal year. For example, the first CR for FY2018 (H.R. 601\P.L. 115-56) provided, "... such amounts as may be necessary, at a rate of operations as provided in the applicable appropriations Acts for fiscal year 2017."

While a blanket continuation of the prior year's spending levels is one option for establishing the CR's funding rate, other funding levels also have been used to provide the funding rate. For example, H.R. 601 stipulated that funding be continued at the rate provided in the applicable FY2017 appropriations bill, minus 0.6791%. While recent CRs have provided that the funding rates for certain accounts are to be calculated with reference to the funding rates in the previous year, Congress could establish a CR funding rate on any basis (e.g., the President's pending budget request, the appropriations bill for the pending year as passed by the House or Senate, or the bill for the pending year as reported by a committee of either chamber).

Full Text Versus Formulaic Continuing Appropriations

CRs have sometimes provided budget authority for some or all covered activities by incorporating the text of one or more regular appropriations bills for the current fiscal year. When this form of funding is provided in a CR or other type of annual appropriations act, it is often referred to as full text appropriations.

When full text appropriations are provided, those covered activities are not funded by a rate for operations, but by the amounts specified in the incorporated text. This full text approach is functionally equivalent to enacting regular appropriations for those activities, regardless of whether that text is enacted as part of a CR. The "Department of Defense and Full-Year Continuing Appropriations Act, FY2011" (P.L. 112-10) is one recent example. For DOD, the text of a regular appropriations bill was included in Division A, thus funding those covered activities via full text appropriations. In contrast, a formula based on the previous fiscal year's appropriations laws was used to provide full-year continuing appropriations for the other projects and activities that normally would have been funded in the remaining 11 FY2011 regular appropriations bills (P.L. 112-10, Division B).

If formulaic interim or full-year continuing appropriations were to be enacted for DOD, the funding levels for both base defense appropriations and Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) spending could be determined in a variety of ways. A separate formula could be established for defense spending, or the defense and nondefense spending activities could be funded under the same formula. Likewise, the level of OCO spending under a CR could be established by the general formula that applies to covered activities (as discussed above), or by providing an alternative rate or amount for such spending. For example, the first CR for FY2013 (P.L. 112-175) provided the following with regard to OCO funding:

Whenever an amount designated for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism pursuant to Section 251(b)(2)(A) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (in this section referred to as an "OCO/GWOT amount") in an Act described in paragraph (3) or (10) of subsection (a) that would be made available for a project or activity is different from the amount requested in the President's fiscal year 2013 budget request, the project or activity shall be continued at a rate for operations that would be permitted by ... the amount in the President's fiscal year 2013 budget request.

Limitations that Continuing Resolutions May Impose

CRs may contain limitations that are generally written to allow execution of funds in a manner that provides for minimal continuation of projects and activities in order to preserve congressional prerogatives prior to the time a full appropriation is enacted.1 As an example, an interim CR may prohibit an agency from initiating or resuming any project or activity for which funds were not available in the previous fiscal year. Congress has, in practice, included a specific section (usually Section 102) in the CR to expressly prohibit DOD from starting production on a program that was not funded in prior years (i.e., a new start), and from increasing production rates above levels provided in the prior year.2 Congress may also limit certain contractual actions such as multiyear procurement contracts.3 Such prohibitions are typically only applied to the Department of Defense.

An interim CR may provide funds at the rate of the prior year's appropriation and, as a result, may provide funds in a manner that differs from an agency's budget request. For example, if a CR is based on the prior year's enacted appropriation, a mismatch could occur at the account level between the agency's request and the CR funding level. The Antideficiency Act prohibits a federal employee from making or authorizing "an expenditure or obligation exceeding an amount available in an appropriation or fund for the expenditure or obligation" unless authorized by law.4 A mismatch at account level between the agency's request and the CR funding level is sometimes referred to as an issue with the color of money.5

Anomalies

Even though CRs typically provide funds at a particular rate, CRs may also include provisions that enumerate exceptions to the duration, amount, or purposes for which those funds may be used for certain appropriations accounts or activities. Such provisions are commonly referred to as anomalies. The purpose of anomalies is to insulate some operations from potential adverse effects of a CR while providing time for Congress and the President to agree on full-year appropriations and avoiding a government shutdown.6

A number of factors could influence the extent to which Congress decides to include such additional authority or flexibility for DOD under a CR. Consideration may be given to the degree to which funding allocations in full-year appropriations differ from what would be provided by the CR. Prior actions concerning flexibility delegated by Congress to DOD may also influence the future decisions of Congress for providing additional authority to DOD under a longer-term CR. In many cases, the degree of a CR's impact can be directly related to the length of time that DOD operates under a CR. While some mitigation measures (anomalies) might not be needed under a short-term CR, extended delays in passing a full-year defense appropriations bill may increase management challenges and risks for DOD.

An anomaly might be included to stipulate a set rate of operations for a specific activity, or to extend an expiring authority for the period of the CR. For example, the second CR for FY2017 (H.R. 2028\P.L. 114-254)), granted three anomalies for DOD:

- Section 155 funded the Columbia Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program (Ohio Replacement) at a specific rate for operations of $773,138,000.

- Section 156 allowed funding to be made available for multiyear procurement contracts, including advance procurement, for the AH–64E Attack Helicopter and the UH–60M Black Hawk Helicopter.

- Section 157 provided funding for the Air Force's KC–46A Tanker, up to the rate for operations necessary to support the production rate specified in the President's FY2017 budget request (allowing procurement of 15 aircraft, rather the FY2016 rate of 12 aircraft).

In anticipation of an FY2018 CR, DOD submitted a list of programs that would be affected under a CR to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). This "consolidated anomalies list" included approximately 75 programs that would be delayed by a prohibition on new starts and nearly 40 programs that would be negatively affected by a limitation on production quantity increases.7

OMB may or may not forward such a list to Congress as a formal request for consideration. Some analysts contend that OMB rarely supports inclusion of anomalies in a CR because anomalies generally reduce the impetus for Congress to reach a budget agreement. According to Mark Cancian, a defense budget analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, "a CR with too many anomalies starts looking like an appropriations bill and takes the pressure off."8

H.R. 601 (P.L. 115-56), the initial FY2018 CR, did not include any anomalies to address the programmatic issues included on the DOD list. H.J.Res. 123 (P.L. 115-90), which extended the CR through December 22, 2017, did not change the terms of H.R. 601 and did not provide any anomalies for DOD.

H.R. 601 was extended through January 19, 2018 by two measures: H.J.Res. 123 (P.L. 115-90) and H.R. 1370 (P.L. 115-96).How Agencies Implement a CR

After enactment of a CR, OMB provides detailed directions to executive agencies on the availability of funds and how to proceed with budget execution. OMB will typically issue a bulletin that includes an announcement of an automatic apportionment of funds that will be made available for obligation, as a percentage of the annualized amount provided by the CR. Funds usually are apportioned either in proportion to the time period of the fiscal year covered by the CR, or according to the historical, seasonal rate of obligations for the period of the year covered by the CR, whichever is lower. A 30-day CR might, therefore, provide 30 days' worth of funding, derived either from a certain annualized amount that is set by formula or from a historical spending pattern. In an interim CR, Congress also may provide authority for OMB to mitigate furloughs of federal employees by apportioning funds for personnel compensation and benefits at a higher rate for operations, albeit with some restrictions.9

Unique Implementation Challenges Faced by DOD

CRs essentially lock DOD funding accounts at the levels appropriated the previous year and prevent scheduled activities. Funding needs typically change from year to year across DOD accounts due to a variety of factors―including emerging or increasing threats to national security―and accounts that are funded below their budgeted level under a CR cannot obligate funds at the anticipated rate. This can restrict planned personnel actions, maintenance and training activities, and a wide variety of contracted support actions. Delaying or deferring such actions can also cause a ripple effect, generating personnel shortages, equipment maintenance backlogs, oversubscribed training courses, and a surge in end-of-year contract spending.10

Prohibitions on Certain Contracting Actions

As discussed, a CR typically includes a provision prohibiting DOD from initiating a new programs or increasing production quantities beyond the prior year's rate. DOD is typically the only federal agency limited in this manner. These DOD-unique prohibitions can directly result in delayed development, production, testing, and fielding of DOD weapon systems. An inability to execute funding as planned can induce costly delays and repercussions in the complex schedules of weapons system development programs. Under a CR, DOD's ability to enter into planned long-term contracts is also typically restricted, thus forfeiting the program stability and efficiencies that can be gained by such contracts.

Misalignments in CR-Provided Funding

DOD may also encounter significant color of money issues under a CR, meaning money is available but it is in the wrong appropriations account. Many defense acquisition programs may face challenges if they were going through a transitional period in the acquisition process amid a CR. For example, a weapons program ramping down development activities and transitioning into production could be allocated research, development, test and evaluation (RDT&E) funding under a CR (i.e. based on the prior year's appropriation) when the program is presently in need of procurement funding.

One example of a program affected by limitations on the color of money is the Columbia class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program, which received funding exclusively for RDT&E in years prior to FY2017.11 In FY2017, however, the budget request for the Columbia class program included not only RDT&E funding, but also advance procurement (AP) funding. With no anomaly there could be no AP funding available for the program under a CR.

Similar to generating issues with the color of money, a CR can result in problems specific to the apportionment of funding in the Navy's shipbuilding account, known formally as the Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN) appropriation account. SCN appropriations are specifically annotated at the line-item level in the DOD annual appropriations bill. As a consequence, under a CR, SCN funding is managed not at the appropriations account level, but at the line-item level. For the SCN account—uniquely among DOD acquisition accounts—this can lead to misalignments (i.e., excesses and shortfalls) in funding under a CR for SCN-funded programs, compared to the amounts those programs received in the prior year. The shortfalls in particular can lead to program execution challenges under an extended or full-year CR.

Timing of the NDAA

Along with specific authorization for military construction projects, the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) provides additional authorities that DOD needs to conduct its mission.12 These authorities range from authorization of end strengths for active and reserve military forces to authorization for specific training activities with allied forces in contingency operations.13 Some such authorities are slated to expire at the start of the fiscal year, while others, such as certain authorities for special pay and bonuses, expire at the end of the calendar year.14 Should final action on the NDAA be delayed, Congress may consider addressing expiring authorities or the need for specific authorizations through the inclusion of relevant policy anomalies in a CR.

While there are many examples of the effects of a CR on the military, many are difficult to quantify. For instance, DOD prioritized funding for readiness activities such as training, equipment maintenance, logistics, and civilian personnel pay in its FY2018 budget request. The budget request included $188.6 billion for the Operation and Maintenance (O&M) account, which funds many of these activities―a $21 billion increase from FY2017. The rate for operations provided under the FY2018 CR is 13% below the President's budget request for O&M. The resulting lack of availability of O&M funding at or near the planned level―combined with the uncertainty of the CR's duration―results in decisions to prioritize the use of available funding to meet urgent and critical needs. The consequent deferral of annual and routine training, preventative maintenance actions, and routine supply activities can erode the readiness of the force.15

DOD Management Challenges Under a CR

In testimony before the Senate Subcommittee on Federal Spending Oversight and Emergency Management, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, a senior Government Accountability Office (GAO) analyst remarked that CRs can create budget uncertainty and disruptions, complicating agency operations and causing inefficiencies.16 Director of Strategic Issues Heather Krause asserts that "this presents challenges for federal agencies continuing to carry out their missions and plan for the future. Moreover, during a CR, agencies are often required to take the most limited funding actions."17 Krause testified that agency officials report taking a variety of actions to manage inefficiencies resulting from CRs, including shifting contract and grant cycles to later in the fiscal year to avoid repetitive work, and providing guidance on spending rather than allotting specific dollar amounts during CRs, to provide more flexibility and reduce the workload associated with changes in funding levels.

When operating under a CR, agencies encounter consequences that can be difficult to quantify, including additional obligatory paperwork, need for additional short-term contracting actions, and other managerial complications as the affected agencies work to implement funding restrictions and other limitations that the CR imposes. For example, the government can normally save money by buying in bulk under annual appropriations lasting a full fiscal year or enter into new contracts (or extend their options on existing agreements) to lock in discounts and exploit the government's purchasing power. These advantages may be lost when operating under a CR.

All federal agencies face management challenges under a CR, but DOD faces unique challenges in providing the military forces needed to deter war and defend the country. In a letter to the leaders of the armed services committees dated September 8, 2017, Secretary of Defense James Mattis asserted that "longer term CRs impact the readiness of our forces and their equipment at a time when security threats are extraordinarily high. The longer the CR, the greater the consequences for our force."18 DOD officials argue that the department depends heavily on stable but flexible funding patterns and new start activities to maintain a modernized force ready to meet future threats. Former Defense Secretary Ashton Carter posited that CRs put commanders in a "straight-jacket" that limits their ability to adapt, or keep pace with complex national security challenges around the world while responding to rapidly evolving threats like the Islamic State.19

Managing with an Expectation of a CR

In all but 4 of the past 40 years, Congress has passed CRs to enable agencies to continue operating when annual appropriation bills have not been enacted before the start of the fiscal year.20 DOD has started the fiscal year under a CR for 13 of the past 17 years (FY2002-FY2018) and every year since FY2010. The average number of days of operation under a CR has increased over that same period. DOD has operated under a CR for an average of 126125 days per year during the period FY2010-FY2017 compared to an average of 32 days per year during the period FY2002-FY2009 (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Days Under a Continuing Resolution: Department of Defense (FY2002-FY2018*) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of dates of enactment of public law. See the CRS Appropriations Status Table at http://www.crs.gov/AppropriationsStatusTable/Index. Notes: *FY2018 began with a continuing resolution |

Since 2010, DOD has spent over 3536 months operating under a CR, compared to less than 9 months during the preceding 8 years. Senior defense officials have stated that the military services and defense agencies have consequently come to expect that a full-year appropriations bill will not be completed by the start of the fiscal year.21 According to Admiral John Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations, "The services are essentially operating in three fiscal quarters per year now. Nobody schedules anything important in the first quarter."22

Given the frequency of CRs in recent years, many DOD program managers and senior leaders work well in advance of the outcome of annual decisions on appropriations to minimize contracting actions planned for the first quarter of the fiscal year.23 The Defense Acquisition University, DOD's education service for acquisition program management, imparts that, "Members of the OSD, the Services and the acquisition community must consider late enactment to be the norm [emphasis in original] rather than the exception and, therefore, plan their acquisition strategy and obligation plans accordingly."24 Replanning and executing short-term contracting actions can be reduced by building a program schedule in which planned contracting actions are pushed to later in the fiscal year when it is more likely that a full appropriation would be enacted. Additionally, managers can take steps to defer hiring actions, restrict travel policies, or cancel nonessential education and training events for personnel.

These efforts by defense officials to prepare for the potential of a CR appear to have reduced some of the need to request that specific anomalies be included in the CR.25 However, former Defense Department Comptroller Mike McCord also held that no matter how the Pentagon responds to these repeated cycles of CRs, "there is no question that short-term funding creates enormous inefficiency.... "26

|

Defense spending and the FY2018 CR For additional specifics about the FY2018 CR (H.R. 601/P.L. 115-56) and the effect on DOD see CRS In Focus IF10734, FY2018 Defense Spending Under an Interim Continuing Resolution, by [author name scrubbed]. |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

CRS Report RL34700, Interim Continuing Resolutions (CRs): Potential Impacts on Agency Operations, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 2. |

Section 102(a) of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 (H.R. 601) states "No appropriation or funds made available or authority granted pursuant to section 101 for the Department of Defense shall be used for: (1) the new production of items not funded for production in fiscal year 2017 or prior years; (2) the increase in production rates above those sustained with fiscal year 2017 funds; or (3) the initiation, resumption, or continuation of any project, activity, operation, or organization ... for which appropriations, funds, or other authority were not available during fiscal year 2017. " |

| 3. |

Section 102(b) of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 (H.R. 601) states "No appropriation or funds made available or authority granted pursuant to section 101 for the Department of Defense shall be used to initiate multiyear procurements utilizing advance procurement funding for economic order quantity procurement unless specifically appropriated later." |

| 4. |

31 U.S.C. §1341. |

| 5. |

The colloquialism color of money is often used in defense circles to refer to accounts (e.g., Military Personnel, Operation and Maintenance, Procurement, and Research, Development, Test and Evaluation) used in appropriations acts. A color of money problem would imply that funding was provided in one account, when it was actually needed in another. |

| 6. |

CRS Report RL34680, Shutdown of the Federal Government: Causes, Processes, and Effects, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 7. |

Tony Bertuca, "Pentagon sends White House detailed list of budget priorities threatened by Capitol Hill stalemate," September 11, 2017, Inside Defense, https://insidedefense.com/share/189868. |

| 8. |

Ibid. |

| 9. |

CRS Report RL34700, Interim Continuing Resolutions (CRs): Potential Impacts on Agency Operations, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 10. |

For more information see CRS In Focus IF10365, End-Year DOD Contract Spending, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 11. |

The Columbia class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program has also been referred to the Ohio Replacement Program or SSBN(X). |

| 12. |

10 U.S.C. §2802 requires specific authorization in law for military construction projects, land acquisitions, and defense access road projects. This authorization typically comes in the form of the annual NDAA. |

| 13. |

Title VI of the annual National Defense Authorization Act provides military personnel authorizations for the Department of Defense. |

| 14. |

For example, Section 611 of H.R. 2810 provides a one-year extension (from December 31, 2017 to December 31, 2018) of authorities for special pay for enlisted members assigned to certain high-priority units, Ready Reserve enlistment bonuses, and authorities related to income replacement payments for reserve component members experiencing extended and frequent mobilization for active duty service. Furthermore, Section 612 provides a similar extension of authorities related to accession and retention bonuses for psychologists, nurses, nurse anesthetists, and other health professionals in critically short wartime specialties. |

| 15. |

For more information on what constitutes readiness activities see CRS Report R44867, Defining Readiness: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 16. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Federal Spending Oversight and Emergency Management, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate, Budget Uncertainty and Disruptions Affect Timing of Agency Spending, GAO-17-807T, September 20, 2017, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687264.pdf. |

| 17. |

Ibid. |

| 18. |

Letter from Secretary of Defense James Mattis to Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) on the potential effects of a continuing resolution on the U.S. military, September 8, 2017. https://news.usni.org/2017/09/13/document-secdef-mattis-letter-mccain-effects-new-continuing-resolution-pentagon. |

| 19. |

U.S. Department of Defense, "Statement from Secretary of Defense Ash Carter on Omnibus Bill Negotiations," press release, December 8, 2015, http://www.defense.gov/News/News-Releases/News-Release-View/Article/633403/statement-from-secretary-of-defense-ash-carter-on-omnibus-bill-negotiations?source=GovDelivery. |

| 20. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Federal Spending Oversight and Emergency Management, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate, Budget Uncertainty and Disruptions Affect Timing of Agency Spending, GAO-17-807T, September 20, 2017, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687264.pdf. |

| 21. |

CRS discussion with Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) Mike McCord, August 8, 2016. |

| 22. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Armed Services, Long-term Military Budget Challenges, 114th Cong., 2nd sess., September 15, 2016. |

| 23. |

Ibid. |

| 24. |

Gregory Martin, "President's Budget Submission and the Congressional Enactment Process," Teaching Note, National Defense University, VA, April 2013, https://acc.dau.mil/adl/en-US/44269/file/76896/Congressional%20Enactmanet%20Process%20April%202013.pdf. |

| 25. |

CRS discussion with Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) Mike McCord, August 8, 2016. |

| 26. |

Sandra Erwin, "Defense Budget: CR's Impact on Military Readiness," August 31, 2017, Real Clear Defense. https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2017/08/31/defense_budget_crs_impact_on_military_readiness_112202.html. |