Immigration: Nonimmigrant (Temporary) Admissions to the United States

Changes from December 8, 2017 to September 10, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Immigration: Nonimmigrant (Temporary) Admissions to the United States: Policy and Trends

Contents

- Introduction

- Admission of Nonimmigrants

- Periods of Admission

- Length of Stay

- Duration of Visa

- Employment Authorization

- Permission to Work

- Labor Market Tests

- Exclusion and Removal

- Inadmissibility

- Presumption of the Intent to Settle Permanently

- Termination of Nonimmigrant Status

- Broad Categories of Nonimmigrants

- Diplomats and Other International Representatives

- Visitors as Business Travelers and Tourists

- Temporary Workers

- Multinational Corporate Executives and International Investors

- Exchange Visitors

- Foreign Students

- Family-Related Visas

- Law Enforcement-Related Visas

- Aliens in Transit and Crew Members

- Statistical Trends

- Analysis of Nonimmigrants by Visa Category

- Temporary Visas Issued

- Temporary Admissions

- Analysis of Nonimmigrants by Region

- Temporary Visas Issued

- Temporary Admissions

- Analysis of

NonimmigrantsNonimmigrant Admissions by Destination - Estimates of the Resident Nonimmigrant Population

- Pathways to Permanent Residence

- Nonimmigrant Visa Overstays

Figures

- Figure 1. Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Category,

FY2016FY2018

- Figure 2. Nonimmigrant Visas Issued,

FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018

- Figure 3. "Other Than B" Visas Issued,

FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018

- Figure 4. I-94 Nonimmigrant Admissions by Category,

FY2015FY2017

- Figure 5. Visa Waiver Program

Admissions FY2006-FY2015and B Visa Admissions FY2008-FY2017

- Figure 6. "

Other than B VisaNon-visitor" Nonimmigrant Admissions,FY2006-FY2015FY2008-FY2017

- Figure 7. Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Region,

FY2016FY2018

- Figure 8. Trends in Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Region,

FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018

- Figure 9. Nonimmigrant Admissions by Region,

FY2015FY2017

- Figure 10. Trends in Nonimmigrant Admissions by Region,

FY2006-FY2015FY2008-FY2017

- Figure 11. Nonimmigrant Admissions by State of Destination,

FY2015FY2017

- Figure 12. Top Sending Countries of Estimated Resident Nonimmigrants in

20142016

Summary

U.S. law provides for the temporary admission of foreign nationals, who are known as nonimmigrants. Nonimmigrants. Nonimmigrants are foreign nationals who are admitted for a designated period of time and a specific purpose. There are 24 major nonimmigrant visa categories, which are commonly referred to by the letter and numeral that denote their subsection in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA); for example, B-2 tourists, E-2 treaty investors, F-1 foreign students, H-1B temporary professional workers, J-1 cultural exchange participants, or S-5 law enforcement witnesses and informants.

A U.S. Department of State (DOS) consular officer (at the time of application for a visa) and a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) inspector (at the time of application for admission) must be satisfied that an alien is entitled to nonimmigrant status. The burden of proof is on the applicant to establish eligibility for nonimmigrant status and the type of nonimmigrant visa for which the application is made. Both DOS consular officers (when the alien is applying for nonimmigrant status abroad) and DHS inspectors (when the alien is entering the United States) must also determine that the alien is not ineligible for a visa under the INA's "grounds for inadmissibility," which include criminal, terrorist, and public health grounds for exclusion.

In FY2016FY2018, DOS consular officers issued 10.49.0 million nonimmigrant visas, down from a peak of 10.9 million in FY2015. There were approximately 6.8 million tourism and business visas, which comprised more than three-quarters of all nonimmigrant visas issued in FY2016FY2018. Other notable groups were temporary workers (883924,000, or 8.510.2%), students (513399,000, or 4.94%), and cultural exchange visitors (380382,000, or 3.74.2%). Visas issued to foreign nationals from Asia made up 4543% of nonimmigrant visas issued in FY2016FY2018, followed by North America (2021%), South America (1718%), Europe (1112%), and Africa (5%).

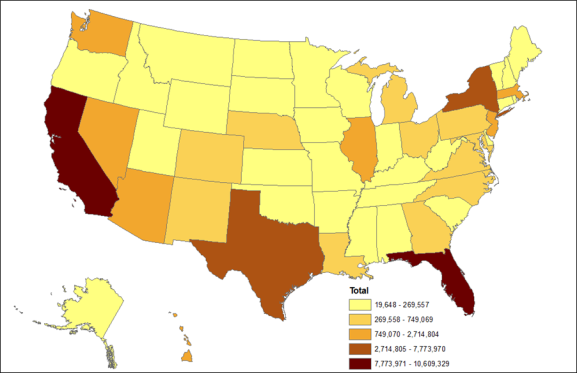

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) inspectors approved 181.31 million temporary admissions of foreign nationals to the United States during FY2016FY2017. CBP data enumerate arrivals, thus counting frequent travelers multiple timeseach time they were admitted to the United States during the fiscal year. Mexican nationals with border crossing cards and Canadian nationals traveling for business or tourist purposes accounted for the vast majority of admissions, representing approximately 104.7103.5 million entries in FY2016. In FY2015, FY2017. California and Florida were the top two destination states for nonimmigrant visa holders in FY2017, with each state being listed as the destination for more than 10 million nonimmigrant admissions. In addition, 10nine other states and the territory of Guam werewere each listed as the destination for more thanat least 1 million nonimmigrant admissions each in that year.

Current law and regulations set terms for nonimmigrant lengths of stay in the United States, typically include foreign residency requirements, and often limit what aliens are permitted to do while in the country (e.g., engage in employment or enroll in school). Some observers assert that the law and regulations are not uniformly or rigorously enforced, and the issue of visa overstays has received an increasing amount of attention in recent years. Achieving an optimal balance among policy priorities, such as ensuring national security, facilitating trade and commerce, protecting public health and safety, and fostering international cooperation, remains a challenge.

Introduction

The United States has long distinguished temporary migration from settlement migration.1 The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) establishes the circumstances under which foreign nationals may be admitted temporarily or come to live permanently.2 Those admitted on a permanent basis are knownreferred to as immigrants, or lawful permanent residents (LPRs), while those admitted on a temporary basis are known as nonimmigrants. The INA provides for the admission of nonimmigrants for designated periods of time and a variety of specific purposes. Nonimmigrants include tourists, foreign students, diplomats, temporary agricultural workers, cultural exchange visitors, internationally known entertainers, foreign media representatives, intracompany business personnel, and crew members on foreign vessels, among others.

Policy discussions about nonimmigrant admissions are as varied as the visa classes under which temporary migrants enter. Tourists, business visitors, and foreign students, for example, are usually seen as a boon to the U.S. economy, while the economic costs and benefits of temporary workers arebut may also raise overstay and security concerns. Debates continue over the implementation of a system to document the complete set of foreign national entries into and exits from the United States. Recent estimates suggest that nonimmigrants who overstay their visas now account for more than half of all new entrants to the unauthorized alien population.3 The economic costs and benefits of temporary workers continue to be hotly debated. In addition, cultural exchange programs are a foreign policy tool, intended to foster democratic principles and spread American values across the globe, but some of these programsthose that include work authorization have come under scrutinybeen criticized for an alleged lack of protections for both U.S. workers and program participants. Further, the entry of nonimmigrants has prompted national security concerns—particularly over those who enter under the Visa Waiver Program. Debates also continue over the implementation of a system to document the exits of foreign nationals from the United States, as nonimmigrants who remain in the country after their visas expire are accounting for a growing share of the unauthorized alien3 populationCongress has expressed concern that foreign nationals using such programs may be exerting undue influence on U.S. college campuses, and in some cases are allegedly attempting to spy on and steal federally funded research.

Achieving an optimal balance among policy priorities—ensuring national security, facilitating trade and commerce, supporting fair labor practices, protecting public health and safety, and fostering international cooperation—remains a challenge. As policymakers consider modifying nonimmigrant visa categories, they may be interested in learning more about each of the categories and their relationship to the policy priorities. This report explains the statutory and regulatory provisions that govern nonimmigrant admissions to the United States before turning to a description of the major nonimmigrant categories. It describes trends in temporary migration, including changes over time in the number of nonimmigrant visas issued and nonimmigrant admissions. Estimates of nonimmigrants who establish residence in the United States are briefly discussed, as are estimates of those who stay beyond their authorized period of admission. The report concludes with a detailed table showing key admissions requirements across all nonimmigrant visa types.

Admission of Nonimmigrants

The Department of State (DOS), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Department of Labor (DOL) each play key roles in administering the law and setting policies on the admission of nonimmigrants. Foreign nationals living outside the United States who wish to enter the country apply for a visa at a U.S. embassy or consulate abroad. Two agencies within DHS handle the admission procedures that occur on U.S. soil: Customs and Border Protection (CBP) determines whether to admit nonimmigrants at U.S. ports of entry (POEs), and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) handles applications for extending or changing an individual's nonimmigrant status and the adjudication of visa petitions by employers for nonimmigrant workers. For certain classes of workers, an employer must first submit an application to DOL's Office of Foreign Labor Certification, a process that is designed to protect the interests of U.S. workers. If approved, the employer then petitions USCIS for the visa on behalf of the worker. Finally, DOS interviews the worker and issues a visa if conditions are met.

A DOS consular officer (at the time of application for a visa) and a CBP immigration inspector (at the time of application for admission) must be satisfied that an alien is entitled to a nonimmigrant status. The burden of proof is on the applicant to establish eligibility for nonimmigrant status and the type of nonimmigrant visa for which the application is made.

Periods of Admission

The time period that a visa lasts has two elements: how long the foreign national is authorized to stay in the United States, and how long the visa is valid for entry into the United States.

Length of Stay

Section 214 of the INA and 8 C.F.R. §214 address length and extensions of stay for the various classes of nonimmigrants. For example, A-1 ambassadors are allowed to remain in the United States for the duration of their service, F-1 students for the duration of their studies, D crew members for up to 29 days, and R-1 religious workers for 30 months (with the possibility of extension for an additional 30 months).4 H-1B visa holders may stay in the country for three years with the option to renew once for up to six years total. Many categories of nonimmigrants are required to have a residence in their home country that they intend to return to as a stipulation of obtaining a visa. (See the Appendix for requirements for each visa type.) Nonimmigrants who remain in the United States past their lawful period of admission are known as referred to as "overstays.

Duration of Visa

Separate from the length of stays authorized for nonimmigrant visas is their validity period, or the time during which the visa is valid for travel. These time periods are negotiated country-by-by country and category-by-category. For example, a B visitor visa from Germanyfor a German national is valid for 10 years while a B visa from Indonesiafor an Indonesian national is valid for five years. The D crew member visa is valid for five years for Egyptians, but two years for Russians. R-1 religious worker visas have a validity period of 36 months for Ugandans and 60 months for Italians. The country-specific validity periods generally reflect reciprocal authorizations of validity periods for U.S. citizens who travel to those countries. DOS publishes frequent updates to reciprocity agreements and explanations of how they affect different visa classes.5

Employment Authorization

Permission to Work

With the exception of the nonimmigrants who are temporary workers (i.e., H-1B, H-2A, H-2B, O, P, R, and Q visa holders), treaty traders (i.e., E visa holders), international representatives (i.e., A and G visa holders), or the executives of multinational corporations (i.e., L visa holders), most nonimmigrants are not allowed to work in the United States. Exceptions to this policy are noted in the Appendix. Working without authorization is a violation of law and results in the termination of nonimmigrant status.

6Labor Market Tests

Labor market tests are required for employers petitioning for workers under the H visa classes, E-3 professional worker visas for Australians, and D crewmember visas. The H-2 visas require employers to complete the labor certification process, which includes applying to DOL for certification that there are not sufficient U.S. workers who are able, willing, qualified, and available to perform the needed work, and that admitting alien workers will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of similarly employed U.S. workers.67 As part of the labor certification process, employers must offer wages at or above specified levels and meet various other requirements.78

The labor market test required for H-1 and E-3 workers, known as labor attestation, is less stringent than labor certification. Any employer wishing to bring in an H-1B or E-3 nonimmigrant must attest in an application to DOL that the employer will pay the nonimmigrant the greater of the actual compensation paid to other employees in the same job or the prevailing compensation for that occupation; the employer will provide working conditions for the nonimmigrant that do not cause the working conditions of the other employees to be adversely affected; and there is no strike or lockout at the place of employment.8

The D visa is for crewmembers working on sea vessels or international airlines but typically does not allow the visa holder to perform longshore work. There are a few exemptions. If an employer is requesting authorization for a D visa holder to perform longshore work via one of these exemptions, the employer must attest that the use of alien crewmembers to perform longshore work is the prevailing practice for the activity at that port, there is no strike or lockout at the place of employment, and notice of the attestation has been given to U.S. workers or their representatives.910

There are no labor market tests for foreign nationals seeking to enter under the other employment-related visas.

Exclusion and Removal

Inadmissibility

DOS consular officers (when the alien is applying abroad), CBP inspectors (when the alien is at a United States port of entry), and USCIS adjudicators (when the alien is applying for an extension or adjustment of status) must confirm that the alien is not ineligible for a visa under the "grounds for inadmissibility" found in §Section 212(a) of the INA.1011 These grounds fall into the following categories:

- health-related grounds,

- criminal history,

- security and terrorist concerns,

- public charge (e.g., indigence),

- seeking to work without proper labor certification,

- illegal entrants and immigration law violations,

- lacking proper documents,

- permanently ineligible for citizenship,

- aliens previously removed, and

- miscellaneous (including polygamists, child abductors, and unlawful voters).

The law provides for waivers of these grounds (except for most of the security and terrorist-related grounds) for nonimmigrants on a case-by-case basis.11

Presumption of the Intent to Settle Permanently

Section 214(b) of the INA generally presumes that all aliens seeking admission to the United States are comingintend to settle permanently; as a result, most foreign nationals seeking to qualify for nonimmigrant visas must demonstrate that they are not coming to reside permanently.1213 The §Section 214(b) presumption is the most common basis for rejecting nonimmigrant visa applications, accounting for three -quarters of ineligibility findings in FY2016.13FY2018.14 There are three nonimmigrant visas for which "dual intent" is allowed, meaning that the prospective nonimmigrant visa holder mayis permitted simultaneously to seek LPR status. Nonimmigrants seeking H-1B visas (professional workers), L visas (intracompany transferees), or V visas (accompanying family members)1415 are exempt from the requirement that they proveto show that they are not coming to the United States to live permanently.

Termination of Nonimmigrant Status

NonimmigrantsThe INA treats nonimmigrants who violate the terms of their visas—such as working without authorization—or stay beyond the period of admission are consideredas unauthorized aliens. As such, they are subject to removal. (deportation).16 The legal status of a nonimmigrant in the United States may also be terminated for national security, public safety, or diplomatic reasons, or following the conviction of a crime of violence that has a sentence of more than one year (i.e., a felony).15

Broad Categories of Nonimmigrants

CurrentlyUnder current law, there are 24 major nonimmigrant visa categories and more than 80 specific types of nonimmigrant visas. Most of the nonimmigrant visa categories are defined in §Section 101(a)(15) of the INA. For most nonimmigrant visa categories, there are and include specific visas for derivatives, typically dependent spouses and minor children, of the principal visa holder. In thisthe following report section, nonimmigrant visas are grouped under broad labels. For a listing of all the current visa types in alphabetical order, see Table A-1 in the Appendix. For each visa type, itthe table provides information from current law and regulations regarding length of stay, foreign residence requirements, employment authorization, labor market test requirements, annual numerical limit, and the number of visas issued in FY2016FY2018.

Diplomats and Other International Representatives

Ambassadors, consuls, and other official representatives of foreign governments (and their immediate family and personal employees) enter the United States on A visas. Official representatives of international organizations (and their immediate family and personal employees) are admitted on G visas. Nonimmigrants entering under the auspices of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have their own visa category, called NATO (or N 1-7).

Visitors as Business Travelers and Tourists

B-1 nonimmigrants are visitors who travel to the United States for business-related purposes such as negotiating a contract, consulting with business associates, or attending a professional conference. To be classified as a visitor for business, an alien must receive his or her salary from abroad, must maintain a foreign residence, and must not receive any remuneration from a U.S. source other than an expense allowance or reimbursement for other expenses incidental to the temporary stay.

B-2 visas are granted to temporary visitors for "pleasure," otherwise known as tourists. Examples of acceptable activities include visiting family or friends, vacationing, and seeking medical treatment. Tourists have consistently been the largest nonimmigrant class of admission to the United States. A B-2 visa holder may not engage in any employment in the country.

Those who wish to travel to the United States for a combination of business and pleasure may obtain a combined B-1/B-2 visa. B visas usually allow for multiple entries and may remain valid for up to 10 years, depending on the applicable Department of State reciprocity schedule. B visa holders are typically admitted to the United States for a period of stay up to six months.1618

Visa Waiver Program

Many business travelers and tourists enter the United States without visas through the Visa Waiver Program (VWP).1719 This provision of the INA (§217) allows the Secretary of Homeland Security to waive the visa documentary requirements for visitors from countries that meet certain statutory criteria.1820 Currently, 38 countries are designated under the VWP, allowing their nationals to visit the United States for up to 90 days without a visa.1921 A separate program is in place for Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). The Guam-CNMI Visa Waiver Program covers admission only to Guam and the CNMI, and 12 countries currently qualify.22 Although not part of the Visa Waiver Program, citizens of Canada and Bermuda who wish to travel to the United States as business visitors or tourists may do so without a visa.20

Border Crossing Card

The border crossing card (BCC), or "laser visa," allows Mexican citizens who reside in Mexico to gain short-term entry to the United States border zone for business or tourism.2123 It may be used for multiple entries and is typically valid for 10 years. Mexican citizens can be granted a laser visa if they are found to be otherwise admissible as B-1 (business) or B-2 (pleasure) nonimmigrants. The laser visa is a combined B-1/B-2/BCC nonimmigrant visa.2224 Current rules limit the BCC holder to visits of up to 30 days within designated border zones in Texas, California, New Mexico, and Arizona.23

Temporary Workers

The major nonimmigrant category for temporary workers is the H visa. The current H-1 category includes workers in specialty occupations (H-1B visa holders), which, at a minimum, require the attainment of a bachelor's degree or its equivalent.2426 Current law sets numerical restrictions on the number of visas that may be issued annually to new H-1B workers at 65,000 with an additional 20,000 for applicants holding a U.S. master's degree or higher. Most H-1B workers enter on visas that are exempt from this cap, however. Exemptions apply to workers who are renewing their visas or are petitioned for by an institution of higher education, or a nonprofit or government research institution.2527

There are two visa categories for bringing in seasonal or temporary workers; agricultural workers enter on H-2A visas, and nonagricultural workers enter on H-2B visas.2628 Annually, the Secretary of Homeland Security designates countries eligible to participate in the H-2 programs.2729 There is no annual numerical limit on the admission of H-2A workers, and the annual limit for the H-2B visa is 66,000.28

H-3 visas are issued to nonimmigrants coming for the purpose of job-related training that is unavailable in their countries of origin and that relates to work that will be performed outside the United States.

The E-3 treaty professional visa is a temporary work visa limited to citizens of Australia. It is similar to the H-1B visa in that the foreign worker in the United States on an E-3 visa must be employed in a specialty occupation.2931

Temporary professional workers who are citizens of Canada or Mexico may enter on TN visas according to terms set by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).32 TN visas are approved for those in certain professions to work in prearranged business activities for U.S. or foreign employers.3033

Persons with extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics, or with extraordinary recognized achievements in the motion picture and television fields are admitted on O visas. Extraordinary ability means a level of expertise indicating that the person has risen to the very top of the field of endeavor and is nationally or internationally acclaimed.31

Internationally recognized athletes or members of an internationally recognized entertainment group coming to the United States to compete or perform enter on P visas. An individual or team athlete, or an entertainer on a P-1 visa must have achieved significant international recognition.35 There are also P visas for performers in reciprocal cultural exchange programs and culturally unique performers, as well as for persons providing essential support services for these performers.

Foreign nationals who work for foreign media companies enter on I visas. Nonimmigrants working in religious vocations enter on R visas. Religious work is currently defined as habitual employment in an occupation that is primarily related to a traditional religious function and is recognized as a religious occupation within the denomination.36 Q visas are issued to participants in employment-oriented cultural exchange programs whose stated purpose is to provide practical training and employment as well as share history, culture, and traditions. USCIS must approve the Q cultural exchange programs.37 Unlike the J cultural exchange program (see "Exchange Visitors"), employers must petition for nonimmigrants under the Q visa program.

In 2011, a transitional worker visa category was established for foreign workers in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), a U.S. territory, was established.32 Employers of.38 This visa classification allows employers in the CNMI to apply for permission to employ nonimmigrant workers who are ineligible for other employment-based nonimmigrant visa classifications under the INA can apply for temporary permission to employ workers in the CNMI under the CW visa classification. The CW visa program is scheduled to end on December 31, 2019. Foreign workers in the CNMI under the CW visa program are expected to find a suitable alternative immigration status before the end of the program if they wish to remain in the CNMI lawfully.33

Multinational Corporate Executives and International Investors

International intracompany transferees who work in an executive or managerial capacity or have specialized knowledge are admitted to the United States on L visas.3439 The L visa enables multinational firms to transfer top-level personnel to their locations in the United States for five to seven years. To be eligible for an L-1 visa, the foreign national must have worked for the multinational firm abroad for one year prior to transferring to a U.S. location.

Treaty traders and investors (and their spouses and children) may enter the United States on E-1 or E-2 visas. To qualify, a foreign national must be a citizen or national of a country with which the United States maintains a treaty of commerce and navigation.3541 The foreign national also must demonstrate that the purpose of coming to the United States is one of the following: "to carry on substantial trade, including trade in services or technology, principally between the United States and the treaty country; or to develop and direct the operations of an enterprise in which the national has invested, or is in the process of investing, a substantial amount of capital."3642 Unlike most nonimmigrant visas, the E visa may be renewed indefinitely. The E-2C visa is for treaty traders (and their spouses and children) working in the CNMI only.

Exchange Visitors

The J visa, also known as the Fulbright program, is used by professors and research scholars, students, foreign medical graduates, teachers, resort workers, camp counselors, au pairs, and others who are participating in an approved exchange visitor program (e.g., the Fulbright Program). DOS's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs is responsible for approving the cultural exchange programs, which must be designed to promote the interchange of persons, knowledge, and skills in the fields of education, arts, and science. J visa holders are admitted for the duration of the cultural exchange program and may be required to return to their home country for two years after completion of the program.3743 Many foreign nationals on J-1 visas are permitted to work as part of their cultural exchange program participation.

Foreign Students

While some foreign students enter the U.S. on J-1 visas, the most common visa for foreign students is the F-1 visa. It is tailored to international students pursuing full-time academic education or language training. To obtain an F-1 visa, a prospective student must be accepted by a school that has been approved by the U.S. government to enroll foreign students. Prospective students must also document that they have sufficient funds or have made other arrangements to cover all their expenses for the entire course of study. Finally, they must demonstrate that they have the scholastic preparation to pursue a full course of study at the appropriate academic level and a sufficient knowledge of English (or have made arrangements with the school for special tutoring or to study in a language they know). Students on F visas are permitted to work in practical training that relates to their degree program, such as paid research and teaching assistantships.44 They are also permitted to engage in Optional Practical Training (OPT), which is temporary employment that is directly related to the student's major area of study.

45Students who wish to pursue a non-academicnonacademic (e.g., vocational) course of study apply for M visas. Much like F visa applicants, those seeking an M visa must show that they have been accepted by an approved school, have the financial means to pay for tuition and expenses and otherwise support themselves during the course of study, and have the requisite scholastic preparation and language skills. Canadian and Mexican nationals who commute to school in the United States enter on F-3 (academic) or M-3 (vocational) visas; they are permitted to work only in practical training that relates to their degree program.

Family-Related Visas

Fiancé(e)s of U.S. citizens may obtain K-1 visas. The intending bride and groom must demonstrate that they are both legally free to marry, meaning any previous marriages must have been legally terminated by divorce, death, or annulment; that they plan to marry within 90 days of the date the K-1 visa holder is admitted to the United States; and that they have met in person during the two years immediately prior to filing the petition. Following the marriage, the K-1 visa holder may apply to adjust to LPR status. Eligible children of K-1 visa applicants can immigrate toenter the United States under a K-2 visa.

To shorten the time that families are separated, spouses who are already married to U.S. citizens, as well as the spouse's children, may obtain K-3 and K-4 visas, respectively. The K-3 and K-4 visas allow the spouse and children to enter the United States and become authorized for employment while waiting for USCIS to process their immigrant petitions. Once admitted to the United States, K-3 nonimmigrants may apply to adjust to LPR status at any time, and K-4 nonimmigrants may do so concurrently or any time after their parent has done so.

V visas are similar to K-3 and K-4 visas except that the sponsoring relative is an LPR rather than a U.S. citizen. No new V visas have been issued since 2007, but individuals are still admitted to the United States on V visas issued prior to 2007.46.38

Law Enforcement-Related Visas

The law enforcement-related visas are among the most recently created. The S visa is issued to informants in criminal and terrorist investigations. Victims of human trafficking who participate in the prosecution of those responsible may receive a T visa.3947 The U visa protects crime victims who assist law enforcement agencies' efforts to investigate and prosecute domestic violence, sexual assault, and other qualifying crimes.40

Aliens in Transit and Crew Members

The C visa is for a foreign national traveling through the United States en route to another country or destination (including the United Nations Headquarters District in New York). The D visa is for an alien crew member on a vessel or aircraft. A combination C-1/D visa is issued to a foreign national traveling to the United States as a passenger to join a ship or aircraft as a worker.

Statistical Trends

DOS and CBP collect data on nonimmigrant visa issuances and nonimmigrant admissions to the United States, respectively. Both sets of data have strengths and shortcomings for analyzing trends related to nonimmigrants.

Data from DOS on the number of visas issued showsshow the potential number of foreign nationals who may gain admission to the United States because not all visa recipients end up traveling to the country, and some who do are denied admission.

Most CBPData from CBP on the number of admissions data come from I-94 forms, which are used to document entries of foreign nationals into the United States.4149 These data enumerate arrivals, thus counting frequent travelers multiple times.4250 Notably, Mexican nationals with border crossing cards and Canadian nationals traveling for business or tourist purposes are not required to fill out I-94 forms and are thusthus are not reflected in CBP data tables. Because Canadian and Mexican visitors make up the vast majority of nonimmigrant admissions, less than half of nonimmigrant admissions to the United States each year are included in the I-94 totals.

Data on nonimmigrant departures are much less completeincomplete because the United States does not have a comprehensive exit system in place. Nonimmigrants may and does not directly track when nonimmigrants overstay their visas, depart the country without submitting a departure form, gain the right to live in the United States permanently, or receive an extension of their nonimmigrant stay, making. Thus, a direct count of nonimmigrants in the country impossible.43is not currently possible.52 Nevertheless, recent improvements in data sharing have allowed DHS to produce estimates of nonimmigrants residing in the United States and overstay rates for nonimmigrants who entered at air or sea ports.4453

The following sections present both visa issuance and admissions data for nonimmigrants by category and geographic region, including trends over the past decade. Estimates of the number of nonimmigrants who have overstayed their visas are also presented, as are estimates of those who have (legally or otherwise) established a residence in the United States.

Analysis of Nonimmigrants by Visa Category

Temporary Visas Issued45

54

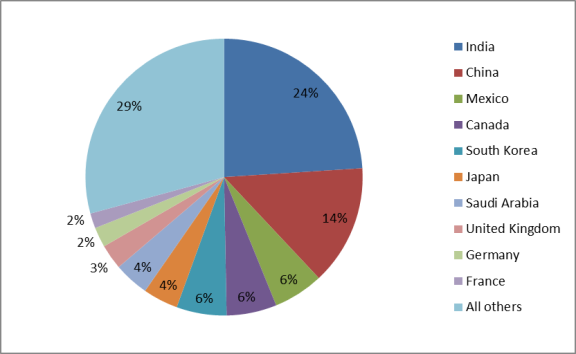

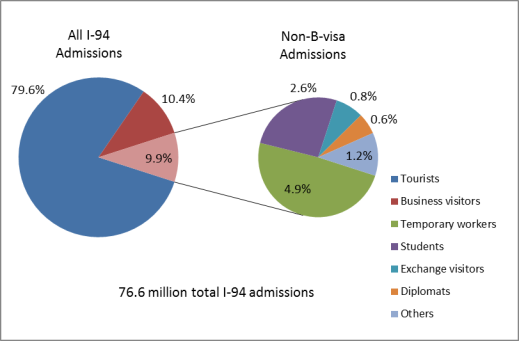

In FY2016FY2018, DOS consular officers issued 10.49.0 million nonimmigrant visas, down from a peak of 10.9 million in FY2015. Combined, visitor visas issued in FY2016FY2018 for tourism and business comprised by far the largest category of nonimmigrant visas: about 6.8 million, or 7875% of the total (see Figure 1). Temporary workers (including H visa holders, treaty traders and investors, intracompany transferees, and representatives of foreign media) received 8.510.2% of all nonimmigrant visas issued in FY2016FY2018, followed by students and exchange visitors with 4.94% and 3.74.2%, respectively (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Category,

|

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from the Department of State's Notes: All visa categories include derivatives (i.e., family, dependents). The temporary workers category includes the following visa types: CW, E, H, I, L, O, P, Q, R, TD, and TN. |

From FY2007 to FY2016In FY2018, the number of nonimmigrant visas issued grew by 61%, from 6.4 million in FY2007 to 10.4 million in FY2016 (see Figure 2). During this time, nonimmigrant visa issuances were at their lowest levelvisa issuances was 55% higher than in FY2009 (9.0 million in FY2018, up from 5.8 million in FY2009) (see Figure 2). Nonimmigrant visa issuances hit a low point for the decade in FY2009, due, in part, to the impact of the economic downturn beginning in 2007 (Great Recession) on international travel. After FY2009, there was a steady increase in the number of visas issued until FY2015; from FY2015 to FY2016FY2018, issuances declined by half a million, or 5%. The number of tourist and business visitor visas (B visas) issued increased by 78% over the entire decade, but like nonimmigrant visas overall, they saw a drop of 5% from FY2015 to FY20161.8 million, or 17%, driven in large part by a decrease in tourist and business visitor visas (B visas). While the number of tourist and business visitor visa issuances increased by 65% over the entire decade, they saw a drop of 20% from FY2015 to FY2018.

| FY2009-FY2018 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from the Department of State's FY1997- |

Because tourist and business visitor visas (B visas) dominate the nonimmigrant flow, it is useful to examine trends in other nonimmigrant categories separately. Figure 3 reveals that the number ofSince FY2009, visas issued for temporary workers saw a sharp drop from FY2008 to FY2009. This timing coincides with the start of the Great Recession. While most other visa categories also experienced some fluctuation, visas issued to diplomats and other representatives held steady across the decade. Since FY2009, visas issued to temporary workers and students have seen large and steady increases resulting in growth rates of 38% and 55%, respectively, over the decade. From FY2015 to FY2016, however, the number of student visas experienced a 25% drop. This sharp decline was largely driven by a 46% decreaseto temporary workers saw large and steady increases, resulting in a growth rate of 79.4% over the decade. The number of visas issued to students also grew considerably, increasing 90% between FY2009 and FY2015; this was followed by a decline (42.1%) between FY2015 and FY2018. Almost two-thirds of this decline was attributed to a decrease (64% overall) in the number of F-1 visas issued to applicants from mainland China, the most frequent recipient of F-1 visas. Saudi Arabia, Mexico, BrazilIndia, and IndiaMexico also experienced steep drops in the number of F-1 visas issued from FY2015 to FY2016FY2018.

| FY2009-FY2018 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from the Department of State's FY1997- Note: All visa categories include derivatives (i.e., family, dependents). |

Temporary Admissions46

55

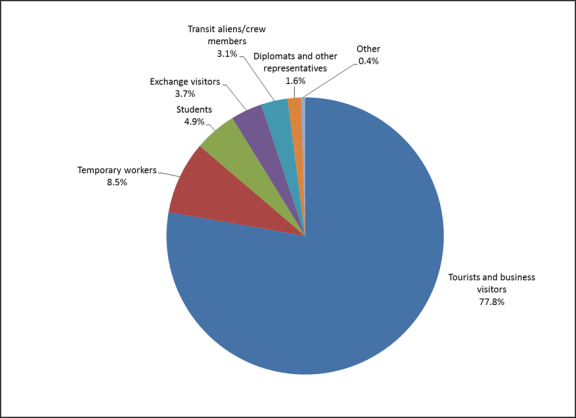

During FY2015FY2017, CBP inspectors granted 181.31 million nonimmigrant admissions to the United States, according to DHS workload estimates. Mexican nationals with border crossing cards, Canadian nationals traveling for business or pleasure, and others not required to complete a forman I-94 form56 accounted for over half (5857%) of these admissions, with approximately 104.7103.5 million entries (see "Statistical Trends"). The remaining categories and countries of the world contributed the remaining 76contributed 77.6 million I-94 admissions in FY2015FY2017. The following analysis of admissions data is limited to I-94 admissions.

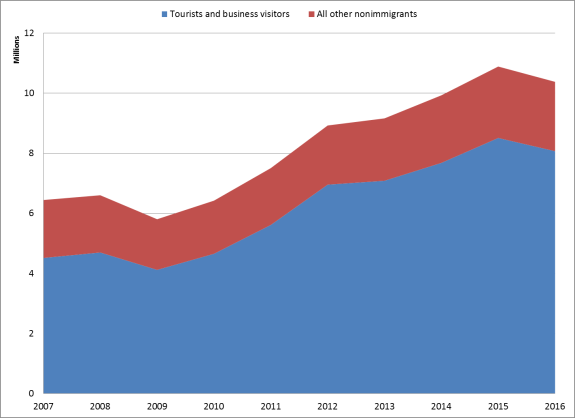

Total I-94 admissions more thanalmost doubled between FY2006 and FY2015, from 33.7FY2008 and FY2017, from 39.4 million to 76.6 million. The trend in admissions of temporary visitors (for business and pleasure) mirrored that for visa issuances: a decline from FY2008 to FY2009 followed by a steady increase. Because DHS has not yet released FY2016 data, it is unknown whether the FY2015 to FY2016 drop in nonimmigrant visas issued will also appear in the admissions data.

77.6 million. The recent 10-year trend in I-94 admissions reveals a decline from FY2008 to FY2009 (during the Great Recession) followed by increases through FY2014 and a subsequent plateau through FY2017. Annual growth in I-94 admissions averaged 12.0% from FY2008 to FY2014 but dropped to 1.2%, on average, from FY2014 to FY2017.

| FY2017 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2017 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Table 25

|

As with the visa issuance data, tourists and business visitors dominate the admissions data (see Figure 4). Over three-quarters of all. Almost four out of five I-94 admissions in FY2015FY2017 were tourists, and another 10.49% were business visitors. Similar to visa issuances, other nonimmigrant categories with measurable percentages of admissions were temporary workers (5.1%, including intracompany transferees, treaty traders/investors, and representatives of foreign media), at almost 5%, students (2.65%), cultural exchange visitors (0.8%), and diplomats (0.6%).

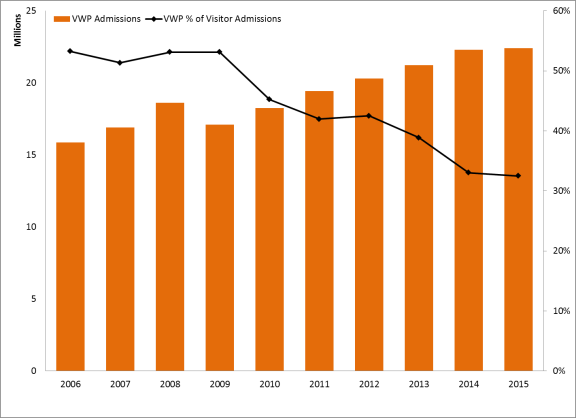

Included in the I-94 admissions data are tourists and business visitors who entered without a visa under the Visa Waiver Program (VWP). While the number of VWP admissions has climbed steadily since FY2009, the share of visitor (B visa)all visitor admissions accounted for by VWP admissions dropped from more than half (53.21%) in FY2006 to less thanFY2008 to about one-third (32.533.7%) in FY2015FY2017 (see Figure 5). This corresponds with an increase in the share of admissions coming from Asia (see Figure 8), as European countries dominate, a continent with few countries that participate in the VWP.

| and B Visa Admissions FY2008-FY2017 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2017 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Table 25 Notes: Includes I-94 admissions only. "Visitor admissions" refers to temporary visitors for pleasure or business (i.e., |

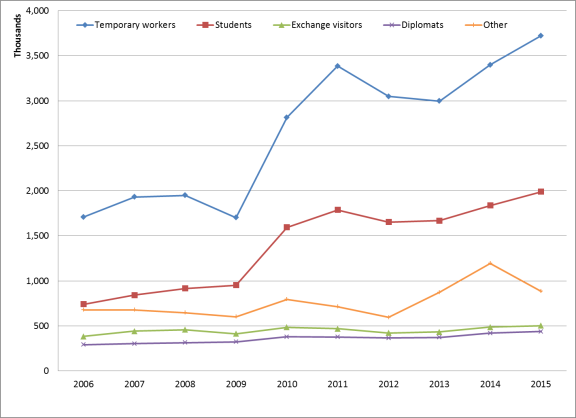

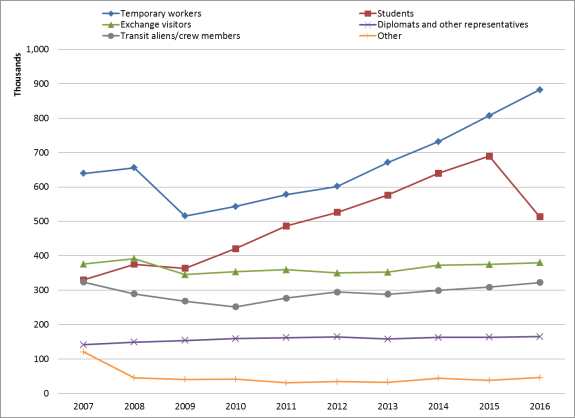

Figure 6 shows FY2006-FY2015FY2008-FY2017 admission trends for all nonimmigrant visa types except for B visa holders. As was also shown in Figure 4, temporary workers are the largest category of "other than B-Visavisa" nonimmigrant admissions, and the number of temporary worker admissions continues to rise. Overall, the temporary workers category saw a 118103.5% increase in the number of admissions from FY2006 to FY2015FY2008 to FY2017, second only to student admissions, which grew by 169111.5%. Admissions of diplomats and exchange visitors grew 5043.0% and 3517.4%, respectively.

Analysis of Nonimmigrants by Region

Temporary Visas Issued47

57

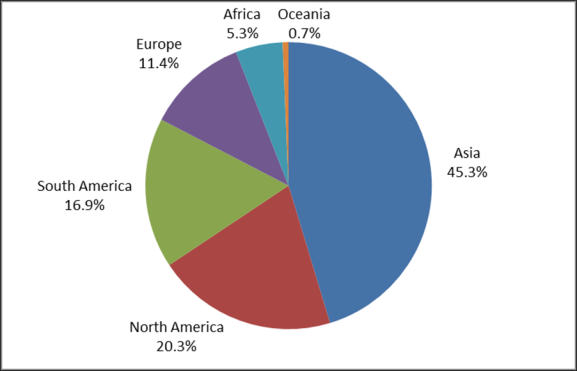

Visas issued to foreign nationals from Asia made up 45.342.7%, or 4.73.9 million, of the 10.49.0 million nonimmigrant visas issued in FY2016FY2018 (see Figure 7). North American nonimmigrants (i.e., those from Canada, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean) accounted for the next largest group of FY2016 nonimmigrant visa issuances, with 2.1 million individualswith 1.9 million nonimmigrant visas issued in FY2018. South America accounted for 1.86 million of the nonimmigrant visa issuances. Europe's 1.21 million visas comprised 11.412.0% of all nonimmigrant visas issued, down from 16.1% in FY2007. Half. Close to half a million nonimmigrant visas were issued to Africans, and less than 7064,000 went to thoseindividuals from Oceania.

|

Figure 7. Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Region,

|

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from the Department of State's FY1997- |

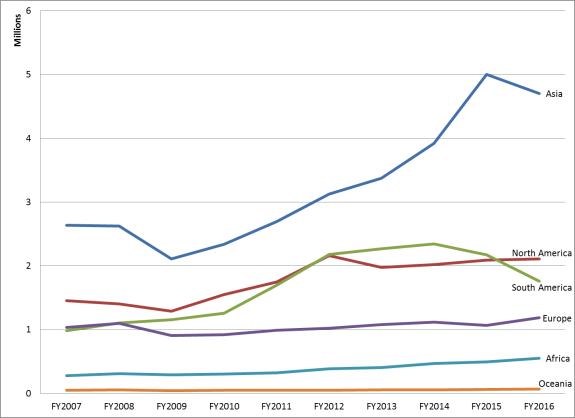

Over the past decadeIn spite of the decline in nonimmigrant visa issuances since FY2015, the number of nonimmigrant visas issued in FY2018 is still higher than a decade ago for each major world region. From FY2009 to FY2018, nonimmigrant visas issued to nationals from Asia increased 78%83%, from 2.6 million visas issued in FY2007 to 4.7 million in FY2016 (see Figure 8). Although Asian nationals experienced the largest numerical increase during that time, the number of nonimmigrant visas issued to South American nationals also increased by 78%, and visas issued to African nationals doubled over the same time period, surpassing 500,000 in FY2016 for the first time1 million to 3.9 million (see Figure 8), the largest numerical and percentage increase of any region. Nonimmigrant visas issued to African nationals increased by 70% during the same time, the second-highest percentage increase.

Reflecting the decrease in total visa issuances from FY2015 to

FY2016FY2018, visa issuances to nationals from Asia, South America, and North and South America alsoall decreased during this time. The drop in visas issued to nationals from Asia is due almost equallywas due mostly to decreases in business and tourist visitors (B) and, but also to a drop in student (F-1) visas. Chinese nationals, for example, received about 237,103almost 1 million fewer B visas and 126,444176,000 fewer F-1 visas in FY2016FY2018 than in FY2015.48 Foreign nationals from Brazil—South America's largest economy and a country suffering from a deep recession—accounted for most of the decrease in business and tourist visitor visas for South America.

|

Figure 8. Trends in Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Region, |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from Department of State's FY1997- |

Temporary Admissions49

60

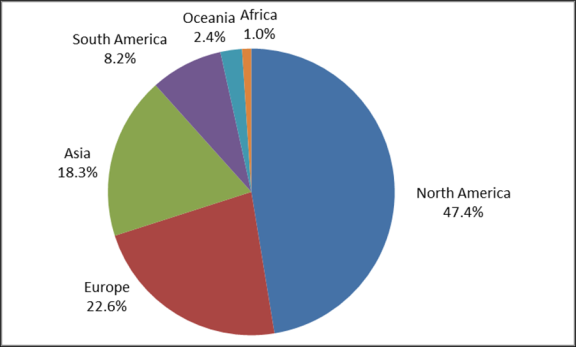

Citizens of North American countries accounted for almost half (47.4%), primarily Mexico and Canada, accounted for 45.6% of I-94 nonimmigrant admissions in FY2015FY2017 (see Figure 9).5061 In addition to sharing a border with the United States, Canadian and Mexican nationals have expedited entry in many cases.5162 Admissions of European nationals made up almost one -quarter (22.623.1%) of FY2015FY2017 nonimmigrant admissions, followed by Asian nationals (18.319.5%). Citizens of South America, Oceania, and Africa each accounted for less than 10% of nonimmigrant admissions. It is worth noting that 30 of the 38 Visa Waiver Program countries are European, which, coupled with the continent's proximity to the United States, helps explain how European nationals can make up almost a quarter of admissions but 9.8only 12.2% of visas issued in FY2015. AlthoughFY2017. In contrast, although foreign nationals from Asia held 45.942.2% of visas issued in FY2015FY2017, they comprised 18.3only 19.5%, or 1417.9 million, of I-94 admissions. This could be due in part to the fact that only five Asian countries are designated in the VWP, and along with the lower likelihood of repeat entries from Asia given its distance from the United States compared to Europe, these factors may explain the larger numbers of visas issued to citizens of Asia than admissions. Citizens from Africa. Citizens from Africa, Oceania, and South America also accounted for a higher share of visas issued than admissions in FY2017.

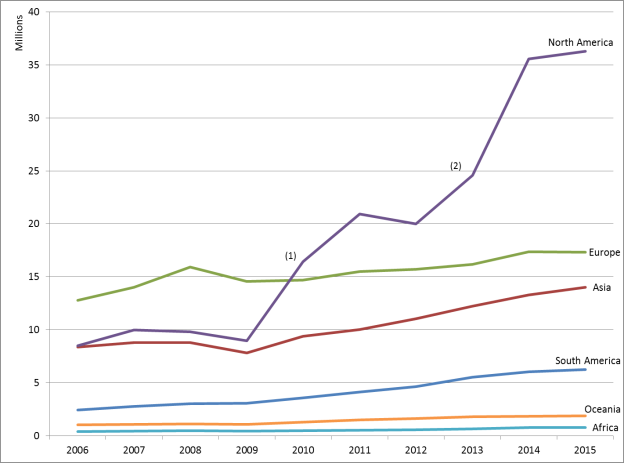

Figure 10 depicts the region of citizenship for I-94 admissions into the United States from FY2006 to FY2015FY2008 to FY2017. The dramatic increase in admissions from North America is due largely to significant changes in the way CBP records I-94 admissions.52 Before the changes in procedure, North American admissions trends mirrored those from Asia. 63 Aside from the large increase in North American admissions that was largely due to improvements in data collection, admissions from South America and Africa had the fastest growth rates from FY2006 to FY2015: 157.3% and 100.9%, respectivelyincreased 108.9% from FY2008 to FY2017. Admissions of European nationals grew the slowest, increasing 35.6% over the decade. Asian admissions increased 67.5%, and those from Oceania grew by 78.8%12.3% over the 10-year time period. Admissions of citizens from Oceania, Asia, and Africa increased by 74.8%, 72.3%, and 70.6%, respectively.

Analysis of NonimmigrantsNonimmigrant Admissions by Destination

Foreign nationals coming to the United States as nonimmigrants go to destinations around the country.53 Eleven states and Guam are asked to report their "address while in the United States." This information allows for the destinations of nonimmigrants to be better understood (see Figure 11).64 Eleven states were identified as the destination for 1.0 million or more nonimmigrant admissions each in FY2015FY2017. California and Florida were the top two destination states, with over 10 million admissions each (see Figure 11)14.1 million and 11.0 million admissions; over 90% of these admissions were tourists and business travelers (B visa holders). New York and Texas were also among the top destinations for all types of nonimmigrants.

Certain states and one territory stood out as primarily tourist destinations for nonimmigrants in FY2017in FY2015: in Hawaii, Nevada, and Guam, more than 98% of nonimmigrant admissions were on B visasfor tourists and business travelers (i.e., B-visa holders plus VWP travelers). Other states stood out as those that attract a disproportionate share of students: in Massachusetts, students and exchange visitors accounted for 12% of nonimmigrant admissions; California and New York had higher numbers of student/exchange visitor admissions than Massachusetts (though, but they made up about 43% of nonimmigrant admissions in each of these states). Michigan (19%) and New Jersey (10%) received a disproportionate share of temporary workers. Temporary workers make up a disproportionate share of nonimmigrant admissions going to Michigan (27%) and New Jersey (10%), compared to the overall share of 5% nationwide. In additionNot surprisingly, the District of Columbia had the highest share of its nonimmigrant admissions classified as diplomats (1413%).

Estimates of the Resident Nonimmigrant Population

Not all nonimmigrant visas are issued for brief visits, and some lengths of stay are sufficiently long for a person to establish residence in the United States. The term "resident nonimmigrant" refers to foreign nationals admitted on nonimmigrant visas whose classes of admission are associated with stays long enough to establish a residence. As noted, A-1 ambassadors are allowed to remain in the United States for the duration of their service, F-1 students are allowed to complete their studies, and H-1B professionalsH-1B workers are allowed to remain for three years or more. The term "resident nonimmigrant" refers to foreign nationals admitted on nonimmigrant visas whose classes of admission are associated with stays long enough to establish a residence, and F-1 students are allowed to complete their studies and, in some cases, remain in the United States to perform temporary work related to their field of study.

The most recent DHS estimates of the resident nonimmigrant population in the United States are for FY2014FY2016. That year, DHS estimated the average population of resident nonimmigrants to be 1.72.3 million on any given day. Of these, 45.6% (790the 2.3 million, 48% (1,100,000) were temporary workers and their families, 38.7% (670% (870,000) were students and their families, 11.6% (20010% (240,000) were cultural exchange visitors and their families, and 4.0% (70% (90,000) were diplomats, other representatives, and their families.5465 DHS estimated that 30% were ages 18 to 24, and 5051% were ages 25 to 44. More than half (57%)In FY2016, 56% of resident nonimmigrants in FY2014FY2016 were male.55

Foreign nationals from Asia made up more than half (56%)61% of resident nonimmigrants in the United States in FY2014FY2016, with India and China making up 2425% and 1415% of the total, respectively. Europe and North America comprised another 14% and 13%15% each of the total, respectively. The top 10 sending countries accounted for 7172% of the total, as depicted in Figure 12.56

Pathways to Permanent Residence

Although the U.S. immigration system is generally bifurcated into temporary and permanent admissions of foreign nationals, there are significant connections between the two. Overall, about half of those receiving lawful permanent residence each year are adjusting to LPR status from another status within the United States, and the other half are new arrivals.57 The adjusters may have entered the country inthrough various capacitiesmeans, including as refugees, asylees, parolees, nonimmigrants, or illegal entrants.58

As discussed earlier, most foreign nationals seeking to qualify for a nonimmigrant visa must demonstrate that they are not coming to the United States to reside permanently. By statute, three nonimmigrant visas permit the visa holderthere are exceptions that allow nonimmigrant visa holders in three categories to simultaneously seek LPR status, (also known as "dual intent"): H-1 professional workers, L intracompany transfers, and V accompanying family members.59

The connections between the temporary and permanent immigration systems affect both employment-based and family-based immigration, the two main mechanismspathways for permanent immigration. While about half (51.648.7%) of all individuals receiving LPR status in FY2015FY2017 adjusted from another status (versus new arrivals), a larger share (84.782.2%) of those receiving employment-based LPR status were adjusting from another status, compared to 35.5% of family-based immigrants.70.60 Presumably, many of thesethe individuals were previously H-1B and L visa holdersadjusting to employment-based LPR status were previously temporary workers with H-1B or L visas, both of which allow for immigrant intent.

The H-1B visa also provides a link for foreign students to become employment-based LPRs. U.S. firms that want to hire foreign students can obtain H-1B visaspetition for H-1B status for recent graduates—a process which is usually faster than sponsoring them for permanent residence—and if the employees meet expectations, the employers may alsothen petition for them to become LPRs through one of the employment-based immigration categories. Some policymakers consider this a natural and positive chain of events, arguing that it would be foolish to educate nonimmigrantsforeign students only to make them leave the country to work for foreign competitors. To that end, there have been legislative proposals to allow aliens who have earned a Ph.D. in a STEM field from a U.S. university to be exempt from numerical limits on H-1Bs and employment-based green cards.6171 Others consider this "F-1 to H-1B to LPR" pathway an abuse of the temporary element of nonimmigrant status72 and a way to circumvent the laws and procedures that protect U.S. workers from being displaced by immigrants. To that end, other proposals would prevent foreign students from gaining U.S. employment through the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program.6273

OPT has become a common mechanism for temporary employment (ranging from 12 to 36 months) that is directly related to an F-1 student's major area of study.63 In FY2014, USCIS reported that74 According to ICE data, there were 136,617 F-1 foreign students approved for OPT, up from 90,896 in FY2009.64218,772 F-1 students in the OPT program as of August 1, 2017, up from 112,779 in 2012.75 In addition to the 12 to 36 months of OPT work authorization, F-1 students with pending H-1B petitions can extend their F-1 status and employment authorization until their H-1B employment begins.65

Nonimmigrant Visa Overstays

It is estimated that each year, hundreds of thousands of foreign nationals overstay their nonimmigrant visas and, as a consequence, become unauthorized aliens. The absence of a comprehensive system to track the exit of foreign nationals from the United States has made direct, complete measurement of overstays impossiblenot currently possible. However, DHS has reportedly made progress in identifying and quantifying overstays and issued a report in each of 2016 and 2017has issued annual reports for the last four years on this topic.6677 According to the 2017FY2018 report, which accounted for 50.4 million nonimmigrants who entered54.7 million nonimmigrant admissions to the United States through an air or sea port andof entry who were expected to depart in FY2016FY2018, an estimated 1.47% (or 739,478 individuals) were overstays. 67 This number22% (or 666,582) overstayed their visa. The number of overstays includes individuals who left the country after their visa expired ("out-of-country overstays") and those who were suspected to still be in the United States.

Given the historical lack of nonimmigrant departure data, immigration scholars have used estimation techniques to study the number and characteristics of the overstay population (and the population of unauthorized aliens writ large). Recent reportsanalyses from the Center for Migration Studies found that, in each year from 2007 to 20142010 to 2017, the number of aliens becoming unauthorized by overstaying a nonimmigrant visa was higher than the number who did so by entering the country without inspection (EWI).6879 This is mainly a result of the sharp decline in the number of EWIs since the early 2000s.69 Of80 Even though recent trends through 2017 reveal that more foreign nationals are overstaying their visas than are entering without inspection, the majority (58%) of the 11 million unauthorized aliens estimated to be living in the United States in 2014, 42% (4.5 million)as of 2014 were estimated to have arrived inentered the country legally and overstayed a visa.70without inspection.81

Appendix. Delineating Current Law for Nonimmigrant Visas

|

Visa |

Class Description |

Period of Stay |

Renewal Option |

Foreign Residence Required |

Employment Authorization |

Labor Market Test |

Annual Numerical Limit |

|

|||||

|

A-1 |

Ambassador, public minister, career diplomat, consul, and immediate family |

Duration of assignment |

Within scope of official duties |

10,754 |

|||||||||

|

A-2 |

Other foreign government official or employee and immediate family |

Duration of assignment |

Within scope of official duties |

101,778 |

|||||||||

|

A-3 |

Attendant or personal employee of A-1/A-2, and immediate family |

Up to three years |

Up to two-year intervals |

If formal bilateral employment agreements or informal de facto reciprocal arrangements exist and DOS provides a favorable recommendation |

1,049 |

||||||||

|

B-1 |

Visitor for business |

Up to one year |

Six-month increments |

Yes |

No |

40,105 |

|||||||

|

B-2 |

Visitor for pleasure |

Six months to one year |

Six-month increments |

Yes |

No |

43,564 |

|||||||

|

B-1/B-2 |

Visitor for business and pleasure |

Six months to one year |

Six-month increments |

Yes |

No |

6,881,797 |

|||||||

|

B-1/B-2/ |

Border crossing cards for Mexicans |

Up to 30 days (or more if coupled with B-1 or B-2) |

Yes |

No |

1,060,390 |

||||||||

|

B-1/B-2/ |

Mexican Lincoln Border Crossing Visa |

Up to 30 days (or more if coupled with B-1 or B-2) |

Yes |

No |

46,333 |

||||||||

|

C-1 |

Alien in transit |

Up to 29 days |

No |

11,992 |

|||||||||

|

C-1/D |

Transit/crew member |

Up to 29 days |

No |

295,140 |

|||||||||

|

C-2 |

Person in transit to United Nations Headquarters |

Up to 29 days |

No |

15 |

|||||||||

|

C-3 |

Foreign government official, immediate family, attendant, or personal employee in transit |

Up to 29 days |

No |

9,073 |

|||||||||

|

CW-1 |

CNMI transitional worker |

Up to one year |

Up to one year |

Yes |

12,998 for FY2017 |

8,093 |

|||||||

|

CW-2 |

Spouse or child of CW-1 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

879 |

|||||||||

|

D |

Crew member |

Up to 29 days |

No |

Only as employee of carrier; exception for longshore work in certain cases |

Only for longshore work exception |

6, |

|||||||

|

E-1 |

Treaty trader, spouse and child, and employee |

Up to two years |

Extensions may be granted in increments of not more than two years for principal, spouse, and child. With limited exceptions, employees are not eligible for extensions of stay |

Treaty trader and employee: within the scope of treaty conditions; spouse: no restrictions |

8,085 |

||||||||

|

E-2 |

Treaty investor, spouse and child, and employee |

Up to two years |

Extensions may be granted in increments of not more than two years for principal, spouse, and child. With limited exceptions, employees are not eligible for extensions of stay |

Treaty trader and employee: within the scope of treaty conditions; spouse: no restrictions |

44,243 |

||||||||

|

E-2C |

CNMI treaty investor, spouse, and child, |

Up to two years |

Extensions may be granted in increments of not more than two years, until the end of the transition period (12/31/2019) |

Treaty investor: within the scope of treaty conditions and only in CNMI; spouse: only in CNMI |

67 |

||||||||

|

E-3 |

Australian specialty occupation professional |

Up to two years |

Renewable indefinitely based on validity of LCA |

Within the scope of treaty conditions |

Yes |

10,500 |

5, |

||||||

|

E-3D |

Spouse or child of E-3 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

Spouse only |

4, |

||||||||

|

E-3R |

Returning E-3 |

Up to two years |

Renewable indefinitely based on validity of LCA |

Within the scope of treaty conditions |

2, |

||||||||

|

F-1 |

Foreign student (academic or language training program) |

Period of study (limited to 12 months for secondary students) |

Extensions granted for extenuating circumstances |

Yes |

Off campus work is restricted, with limited exceptions |

471,728 |

|||||||

|

F-2 |

Spouse or child of F-1 |

Same as principal |

No |

30,486 |

|||||||||

|

F-3 |

Border commuter academic or language student |

Period of study |

Yes |

Only practical training related to degree |

0 |

||||||||

|

G-1 |

Principal resident representative of recognized foreign member government to international organization, staff, and immediate family |

Duration of assignment |

For principal: within scope of official duties; for dependents: pursuant to bilateral agreements or reciprocal arrangements |

5, |

|||||||||

|

G-2 |

Other representative of recognized foreign member government to international organization, staff, and immediate family |

Duration of assignment |

Within scope of official duties; not authorized for dependents |

15,906 |

|||||||||

|

G-3 |

Representative of |

Duration of assignment |

For principal: within scope of official duties; for dependents: pursuant to bilateral agreements or reciprocal arrangements |

386 |

|||||||||

|

G-4 |

International organization officer or employee, and immediate family |

Duration of assignment |

For principal: within scope of official duties; for dependents: pursuant to bilateral agreements or reciprocal arrangements |

22,756 |

|||||||||

|

G-5 |

Attendant or personal employee of G-1 through G-4, and immediate family |

Up to three years |

Up to two-year increments |

For principal: within scope of official duties; not authorized for dependents |

598 |

||||||||

|

H-1B |

Temporary worker—professional specialty occupation |

Specialty occupation: up to three years (but may not exceed the validity period of the LCA); DOD research & development: up to five years; Fashion model: up to three years |

Specialty occupation or fashion model: up to three years (six-year max total period of stay); DOD research & development: up to five years (10-year max total period of stay) |

Yes |

Yes |

Specialty occupation or fashion model: 65,000, plus 20,000 for workers with U.S. advanced degrees; ; DOD research & development: 100 at any time |

180,057 |

||||||

|

H-1 B-1 |

Free trade agreement professional from Chile or Singapore |

One year |

In one-year increments |

Yes |

No |

1,400 for Chile; 5,400 for Singapore |

1,294 Singapore: 808 |

||||||

|

H-2A |

Temporary worker—agricultural workers |

Up to one year |

In one-year increments; three years max |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

134,368 |

||||||

|

H-2B |

Temporary worker— |

Up to one year (up to three years in the case of a one-time event) |

Up to one year; three years max |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

66,000 (an additional 15,000 visas were approved for the second half of |

84,627 |

|||||

|

H-3 |

Temporary worker—trainee |

Alien trainee: up to two years Special education exchange visitor program: up to 18 months |

Alien trainee: stay may be extended for length of training program, but no more than two years; Special education exchange visitor program: stay may be extended up to 18 months |

Yes |

Yes, as part of the training program |

Special education exchange visitor program: 50 |

1, |

||||||

|

H-4 |

Spouse or child of H-1B, H-1B-1, H-2A, H-2B, or H-3 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

Yes |

Only if H-1B spouse has an approved petition for employment-based LPR status |

134,368 |

|||||||

|

I |

Representative of foreign information media, spouse and child |

Duration of employment |

Only as employee of foreign media |

14,536 |

|||||||||

|

J-1 |

Cultural exchange visitor |

Period of program |

Yes |

Yes, if program has work component |

339,712 |

||||||||

|

J-2 |

Spouse or child of J-1 |

Same as principal |

Only as approved by DHS |

40,408 |

|||||||||

|

K-1 |

Fiancé(e) of U.S. citizen |

Valid for four months; must marry within 90 days of entry to adjust status |

Yes |

38,403 |

|||||||||

|

K-2 |

Child of K-1 |

Same as principal |

Yes |

5,727 |

|||||||||

|

K-3 |

Spouse of U.S. citizen awaiting LPR visa |

Two years |

Two-year increments |

Yes |

102 |

||||||||

|

K-4 |

Child of K-3 |

Two years or until 21st birthday |

Two-year increments |

Yes |

20 |

||||||||

|

L-1 |

Intracompany transferee (executive, managerial, and specialized knowledge personnel continuing employment with international firm or corporation) |

Up to three years except only up to one year when beneficiary is coming to open or be employed in a new office |

Increments of up to two years (total period of stay may not exceed five years for aliens employed in a specialized knowledge capacity; or seven years for aliens employed in a managerial or executive capacity) |

Yes |

79,306 |

||||||||

|

L-2 |

Spouse or child of L-1 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

Only as approved by USCIS |

85,872 |

||||||||

|

M-1 |

Vocational student |

Duration of study |

Up to three years from original start date |

Yes |

Only practical training related to degree |

10,305 |

|||||||

|

M-2 |

Spouse or child of M-1 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

Yes |

No |

389 |

|||||||

|

M-3 |

Border commuter vocational or nonacademic student |

Period of study |

Yes |

Only practical training related to degree |

0 |

||||||||

|

NATO-1 |

Principal permanent representative of member nations to NATO, high ranking NATO officials, and immediate family members |

Tour of duty |

Within scope of official duties |

10 |

|||||||||

|

NATO-2 |

Other representatives of member states to NATO (including any of its subsidiary bodies), and immediate family members; dependents of member of a force entering in accordance with provisions of NATO agreements; members of such force if issued visas |

Tour of duty |

Within scope of official duties |

5,588 |

|||||||||

|

NATO-3 |

Official clerical staff accompanying a representative of a member state to NATO, and immediate family |

Tour of duty |

Within scope of official duties |

2 |

|||||||||

|

NATO-4 |

Officials of NATO (other than those classifiable as NATO-1), and immediate family |

Tour of duty |

Within scope of official duties |

168 |

|||||||||

|

NATO-5 |

Experts, other than NATO-4 officials, employed in missions on behalf of NATO, and their dependents |

Tour of duty |

Within scope of official duties |

42 |

|||||||||

|

NATO-6 |

Civilian employees of a force entering in accordance with the provisions of NATO agreements or attached to NATO headquarters, and immediate family |

Tour of duty |

Within scope of official duties |

525 |

|||||||||

|

NATO-7 |

Attendant or personal employee of NATO-1 through NATO-6, and immediate family |

Up to three years |

Increments of up to two years |

Within scope of official duties |

1 |

||||||||

|

N-8 |

Parent of certain special immigrants (pertaining to international organizations) |

Up to three years, as long as special immigrant remains a child |

Up to three-year intervals, as long as special immigrant remains a child |

Yes |

0 |

||||||||

|

N-9 |

Child of N-8 or of certain special immigrants (pertaining to international organizations) |

Up to three years, until no longer a child |

Up to three-year intervals, until no longer a child |

Yes |

0 |

||||||||

|

O-1 |

Person with extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics |

Up to three years |

Up to one year |

Yes |

15,918 |

||||||||

|

O-2 |

Person accompanying and assisting in the artistic or athletic performance by O-1 |

Up to three years |

Up to one year |

Yes |

Yes |

7,417 |

|||||||

|

O-3 |

Spouse or child of O-1 or O-2 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

Only as approved by USCIS |

4, |

||||||||

|

P-1 |

Internationally recognized athlete or member of an internationally recognized entertainment group and essential support |

Up to five years for individual; up to one year for group or team |

Up to five years for individual; up to one year for group or team |

Yes |

Yes |

24, |

|||||||

|

P-2 |

Artist or entertainer in a reciprocal exchange program and essential support |

Up to one year |

Up to one year |

Yes |

Yes |

72 |

|||||||

|

P-3 |

Artist or entertainer in a culturally unique program and essential support |

Up to one year |

Up to one year |

Yes |

Yes |

9,580 |

|||||||

|

P-4 |

Spouse or child of P-1, P-2, or P-3 |

Same as principal |

One-year increments |

Yes |

Only as approved by USCIS |

1, |

|||||||

|

Q-1 |

International cultural exchange program participant |

Duration of program; up to 15 months |

One-year increments |

Yes |

Yes, with employer approved by program |

2,025 |

|||||||

|

R-1 |

Religious worker |

Up to 30 months |

Up to 30 months, not to exceed 5 years total stay |

Yes |

4, |

||||||||

|

R-2 |

Spouse or child of R-1 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

No |

1, |

||||||||

|

S-5 |

Criminal informant |

Up to three years |

No extension; may adjust to LPR status if contribution was substantial |

Yes |

200 |

0 |

|||||||

|

S-6 |

Terrorist informant |

Up to three years |

No extension; may adjust to LPR status if contribution was substantial |

Yes |

50 |

0 |

|||||||

|

S-7 |

Spouse or child of S-5 and S-6 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

1 |

|||||||||

|

T-1 |

Victim of human trafficking |

Up to four years; may adjust to LPR status if conditions are met |

Only for law enforcement need, adjustment to LPR status, or exceptional circumstances |

Yes |

5,000 |

0 |

|||||||

|

T-2 |

Spouse of T-1 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

Yes |

89 |

||||||||

|

T-3 |

Child of T-1 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

310 |

|||||||||

|

T-4 |

Parent of T-1 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

26 |

|||||||||

|

T-5 |

Unmarried sibling under 18 years of age on date T-1 applied |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

40 |

|||||||||

|

T-6 |

Adult or minor child of T-1 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

7 |

|||||||||

|

TN |

NAFTA professional |

Up to three years |

Renewable indefinitely, in up to three-year intervals |

Yes |

14,768 |

||||||||

|

TD |

Spouse or child of TN |

Three years |

Same as principal |

9,762 |

|||||||||

|

U-1 |

Victim or informant of criminal activity |

Up to four years; may lead to adjustment to LPR status if specified conditions are met. |

Only if necessary for law enforcement purposes |

Yes |

10,000 |

146 |

|||||||

|

U-2 |

Spouse of U-1 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

Yes |

113 |

||||||||

|

U-3 |

Child of U-1 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

1204 |

|||||||||

|

U-4 |

Parent of U-1 under the age of 21 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

40 |

|||||||||

|

U-5 |

Unmarried sibling under age 18 |

Same as principal |

Same as principal |

60 |

|||||||||

|

V-1 |

Spouse of LPR who has petition pending for three years or longer; transitional visa that leads to LPR status when visa becomes available |

Up to two years |

Up to two years |

Yes |

0 |

||||||||

|

V-2 |

Child of LPR who has petition pending for three years or longer |

Up to two years, or until 21st birthday |

Up to two years, or until 21st birthday |

Yes, assuming they meet age requirements |

0 |

||||||||

|

V-3 |

Child of V-1 or V-2 |

Up to two years, or until 21st birthday |

Up to two years, or until 21st birthday |

Yes, assuming they meet age requirements |

0 |

||||||||

|

Grand Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10,381,491 |

Source: §101(a)(15), §212, and §214 of the Immigration and Nationality Act; and §214 of 8 C.F.R., and Department of State, Report of the Visa Office 20162018.

Notes: When a cell in the table is blank, it means the law and regulations are silent on the subject. CNMI = Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; LCA = labor condition application; NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization; and NAFTA = North American Free Trade Agreement.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Senior Research Librarians, Sarah Caldwell, [author name scrubbed]Karma Ester, and LaVonne Mangan, assisted with the update to Table A-1.

Footnotes

| 1. |

The Immigration Act of 1924 (P.L. 68-139) recognized immigrants as those coming to settle in the United States and provided for the following classes of temporary migrants: accredited officials of foreign governments, their families, and employees; tourists and business visitors; aliens in transit; crewmen; treaty traders; students; and representatives of international organizations. |

||||||

| 2. |

For an overview of the permanent immigration system see CRS Report R42866, Permanent Legal Immigration to the United States: Policy Overview. |

||||||

| 3. |

Robert Warren, "US Undocumented Population Continued to Fall from 2016 to 2017, and Visa Overstays Significantly Exceeded Illegal Crossings for the Seventh Consecutive Year," Center for Migration Studies, January 16, 2019. "Alien" is the term used in law and is defined as anyone who is not a citizen or national of the United States. (A U.S. "national" is a person owing permanent allegiance to the United States and includes citizens. Noncitizen nationals are individuals who were born either in American Samoa or on Swains Island to parents who are not citizens of the United States.) In this report, the terms "migrant," "alien," and "foreign national" are used interchangeably. |

||||||

| 4. |

Nonimmigrant visa categories are commonly referred to by the letter (and sometimes also the numeral) that denote their subsection in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). |

||||||

| 5. |

U.S. Department of State, "Reciprocity and Civil Documents by Country," at https://travel.state.gov/content/visas/en/fees/reciprocity-by-country.html. |

||||||