Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

Changes from June 7, 2017 to August 25, 2023

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Overview of Recent Discretionary Spending

- The Budget Control Act of 2011

- Congress Has Modified BCA Caps to Mitigate Fiscal Stringency

- Federal Budget Data and Concepts

- OMB Budget Data

- Negative Budget Authority

- Federal Credit Programs

- Background on Functional Categories

- Historical Spending Trends

- Defense and International Affairs

- Cold War, Peace Dividend, and the Global War on Terror

- Defense Funding Outside of the Department of Defense

- International Affairs

- Domestic Social Programs

- Non-Defense Security and Non-Security Spending Diverge After 9/11

- The Recovery Act

- Education, Training, Employment, and Social Services

- Federal Health Programs

- Income Security

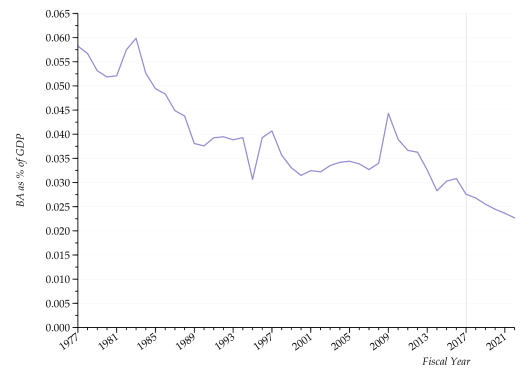

- Social Security

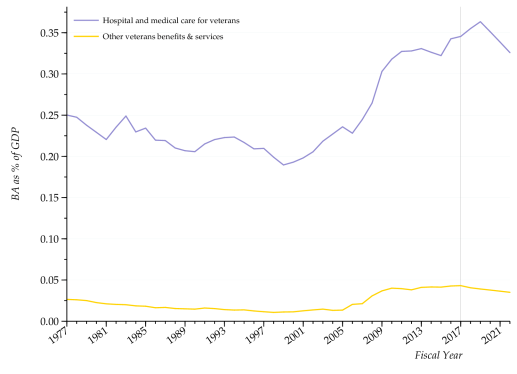

- Veterans' Benefits and Services

- Physical Resources

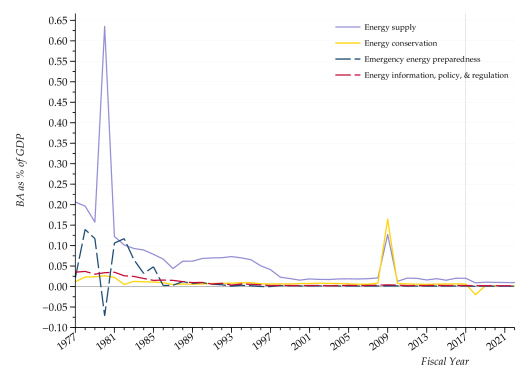

- Energy

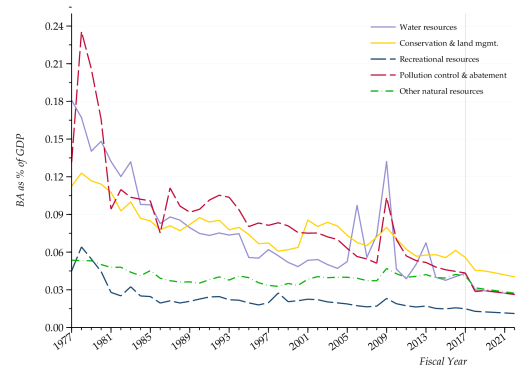

- Natural Resources and Environment

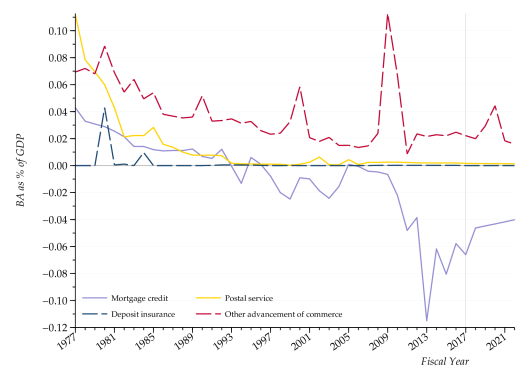

- Commerce and Housing Credit

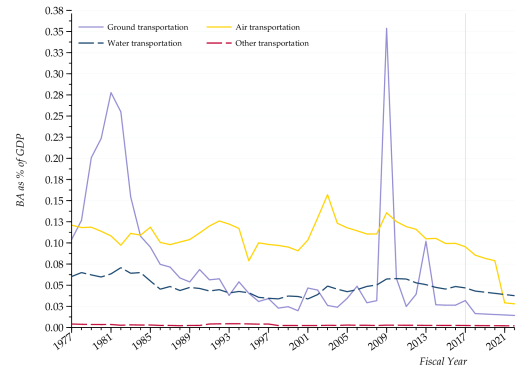

- Transportation

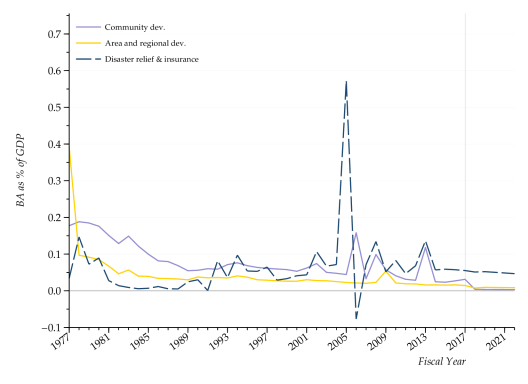

- Community and Regional Development

- Other Federal Functions

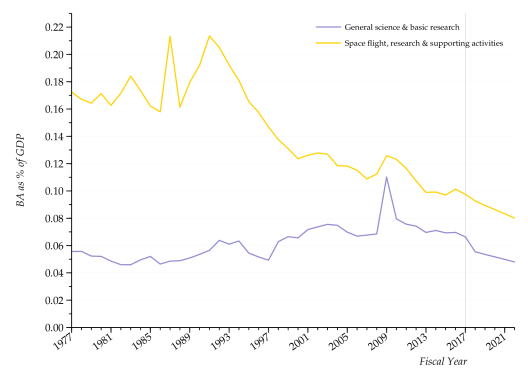

- General Science, Space, and Technology

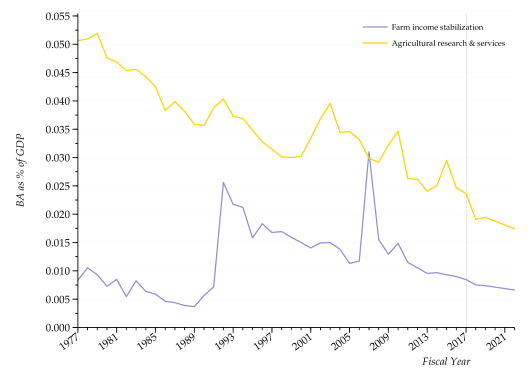

- Agriculture

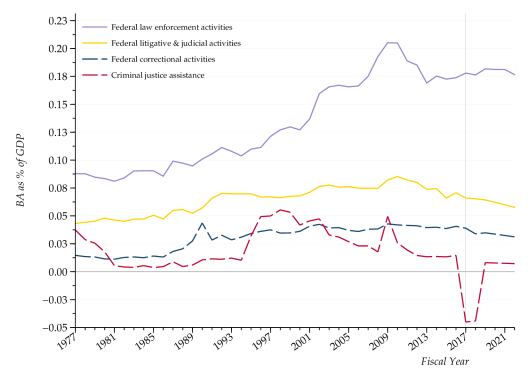

- Administration of Justice

- General Government

Figures

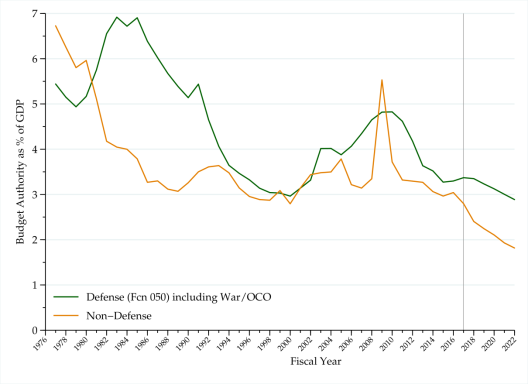

- Figure 1. Discretionary Defense and Non-Defense Spending

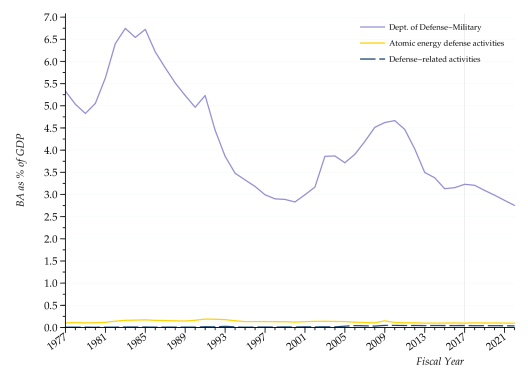

- Figure 2. National Defense (050) Subfunctions

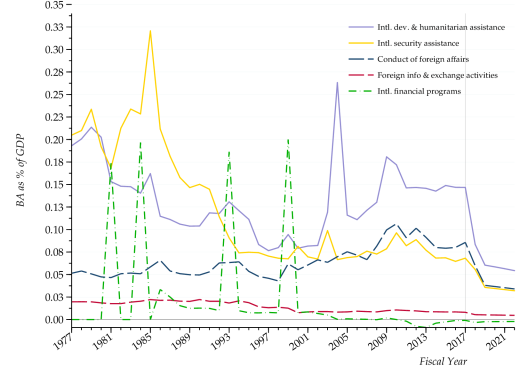

- Figure 3. International Affairs (150) Subfunctions

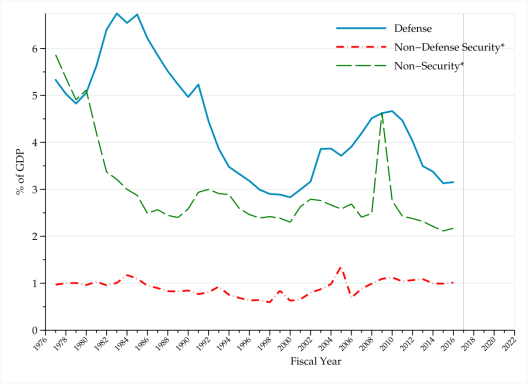

- Figure 4. Security and Non-Security Funding Trends

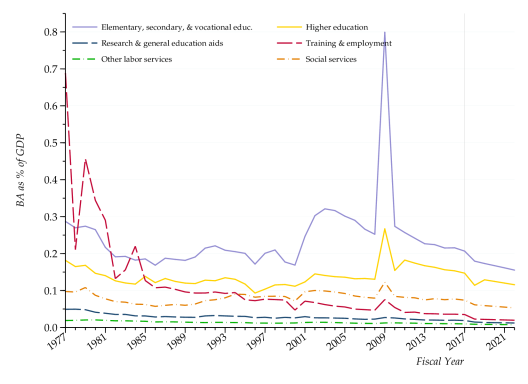

- Figure 5. Education, Training, Employment, and Social Services (500) Subfunctions

- Figure 6. Federal Health Care

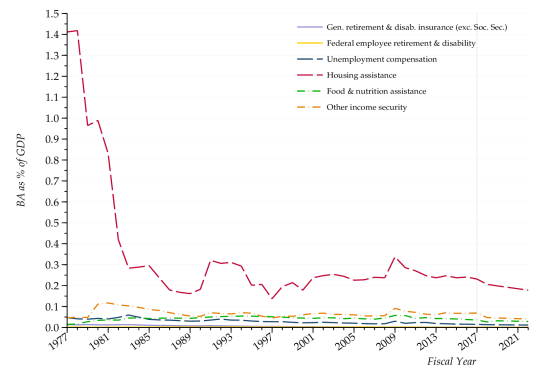

- Figure 7. Income Security (600) Subfunctions

- Figure 8. Social Security (650) Subfunction

- Figure 9. Veterans Benefits and Services (700) Subfunctions

- Figure 10. Energy (270) Subfunctions

- Figure 11. Natural Resources and Environment (300) Subfunctions

- Figure 12. Commerce and Housing Credit (370) Subfunctions

- Figure 13. Transportation (400) Subfunctions

- Figure 14. Community and Regional Development (450) Subfunctions

- Figure 15. General Science, Space, and Technology (250) Subfunctions

- Figure 16. Agriculture (350) Subfunctions

- Figure 17. Administration of Justice (750) Subfunctions

- Figure 18. General Government (800) Subfunctions

Summary

Discretionary Budget Authority by

August 25, 2023

Subfunction: An Overview

D. Andrew Austin

This report provides a graphical overview of historical trends in discretionary budget authority

Analyst in Economic Policy

(BA) from FY1977 through FY2016FY2022, preliminary estimates for FY2017FY2023 spending, and the levels

reflecting the President'’s proposals for FY2018FY2024 through FY2022FY2028 using data from the FY2018 FY2024 budget submission released on May 23, 2017in March 2023. This report, by illustrating trends in broad budgetary

categories, provides a starting point for discussions about fiscal priorities. Other CRS products analyze spending trends in specific functional areas. As the 118th Congress considers the FY2024 budget, past spending trends may help frame policy discussions. Other CRS products analyze funding for specific agencies, program areas, or appropriations bills.

Functional categories (e.g., national defense, agriculture, etc.) provide a means to compare federal funding for activities within broad policy areas that often cut across several federal agencies. Subfunction categories provide a finer division of funding levels within narrower policy areas. Budget function categories are used within the budget resolution and for other purposes, such as estimates of tax expenditures. Spending in this report is measured and illustrated in terms of discretionary budget authority as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Measuring spending as a percentage of GDP in effect controls for inflation and population increases. A flat line on such graphs indicates that spending has increased at the same rate as overall economic growth. In some cases, rescissions, offsetting receipts, or budgetary scorekeeping adjustments can result in negative budget authority.

Discretionary spending is provided and controlled through appropriations acts, which provide budget authority to federal agencies to fund many of the activities commonly associated with such federal government functions such as running executive branch agencies, congressional offices and agencies, and international operations of the government. Essentially all spending on federal wages and salaries is discretionary. Administrative costs for entitlement programs such as Social Security are generally funded by discretionary spending, while mandatory spending—not shown in figures presented in this report—generally funds the benefits provided through those programs. For some federal programs, such as surface transportation, the division of funding into discretionary and mandatory categories can be complex.

Spending caps and budget enforcement mechanisms established in the this report’s figures—generally funds the program benefits. The division of funding into discretionary and mandatory categories for surface transportation, however, is complex.

Statutory caps on discretionary spending were originally set in the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 (BEA; P.L. 101-508), which also limited mandatory spending and revenue reductions. Those caps were extended through the 1990s, but expired shortly after the attacks of September 11, 2001. Both defense and nondefense discretionary spending grew more rapidly in the following decade compared to the 1990s. The Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25; BCA) strongly affected recent budgets. The BCA set discretionary spending caps on defense (budget function 050) and non-defense funding and created a formula to lower those caps to achieve a portion of spending cuts called for in the BCA. Congress modified BCA caps several times, first for FY2013 as part of the fiscal cliff deal at the start of January 2013 (American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012; P.L. 112-240), then through the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA2013; P.L. 113-67) and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74), thus avoiding decreases in levels of discretionary funding. The Trump Administration has proposed changes in BCA caps to allow higher defense spending and to constrain non-defense spending.

A first continuing resolution (P.L. 114-223) was enacted on September 29, 2016, which provides discretionary funding through December 9, 2016. A second continuing resolution (P.L. 114-254), enacted on December 10, 2016, extended funding through April 28, 2017. A stopgap funding measure (P.L. 115-30) was enacted on April 28, 2017. An omnibus appropriations measure (P.L. 115-31) enacted on May 5, 2017, provided funding for the remainder of FY2017.

As the 115th Congress begins consideration of the FY2018 budget, past spending trends may help frame policy discussions. For example, rapid growth in national defense and other security spending during the past decade, along with the fiscal consequences and responses to the 2007-2009 Great Recession, has played an important role in fiscal discussions. Since FY2010, base defense discretionary spending has essentially been held flat and non-defense discretionary spending has been reduced significantly. The base defense budget excludes war funding (Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terror). While war funding levels are well below those of the last decade, they still represent significant commitments of federal resources.

Introduction

This report presents figures showing trends in discretionary budget authority as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) by subfunction within each of 17 budget function categories, using data from President Trump's FY2018Joseph R. Biden’s FY2024 budget submission.11 This report provides a graphical overview of historical trends in discretionary budget authority from FY1977 through FY2016FY2022, estimates for FY2017FY2023 spending, and the levels consistent with the President'’s proposals for FY2024for FY2018 through FY2022.2FY2028.2 Spending in this report is shown as a percentage of GDP to control for the effects of inflation, population growth, and growth in per capita income.33 Past spending trends may prove useful in framing policy discussions as the 115th118th Congress prepares to confront a new set of challenges aswhile it considers a federal budget for FY2018.

Discretionary spending is provided and controlled through appropriations acts. These acts fundFY2024.

Budget Concepts and Discretionary Spending Appropriations acts provide and control discretionary spending,4 which funds many of the activities commonly associated with federal government functions, such as running executive branch agencies, congressional offices and agencies, and international operations of the government.5 Mandatory spending, which is provided by other kinds of acts, supportsgovernment.4 Thus, the figures showing trends in discretionary budget authority (BA) presented below do not reflect the much larger expenditures on various program benefits supported by mandatory spending. For some program areas, such as surface transportationhighway and mass transportation funding, the division of expendituresspending into discretionary and mandatory categories can be complex.

is more complex.

Discretionary spending in this report is measured in terms of BA. Budget authority for an agency has been compared to having funds in a checking account. Funds are availablebudget authority (BA). An agency head with BA can obligate the federal government to make payments, subject to congressional restrictions, for contractors, employees, or grantees to carry out the goals set in legislation. restrictions, and can be used to enter into obligations such as contracts or hiring personnel. Outlays occur when the U.S. Treasury disburses funds to honor those obligations. Thus, outlays follow BA with a lag. ForOutlays for personnel costs, lags are generally short and outlays mostly occur in the same year that BA is provided. Forprovided, but for large and complex projects, outlays may be spread over several years. Nearly all budget authorityBA eventually results in outlays, although some. In some cases, BA expires without being used. For instance, an agency might have difficulty in hiring personnel with the right qualifications or in finding a contractor with appropriate capabilities or a contract might cost less than anticipated. In a few cases, major federal initiatives were later curtailed or cancelled, resulting in the rescission of BA. For instance, most funding for the Carter Administration'’s synthetic fuels program and the Obama Administration'Administration’s plans for high-speed rail did not result in outlays.

1 The President’s FY2024 budget (http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/) was released on March 9, 2023. Because the final FY2023 appropriations measure was enacted in December 2022, spending levels for that fiscal year reflect those in an earlier continuing resolution.

2 The start of the federal fiscal year was changed from July 1 to October 1 in 1976 to accommodate changes in the congressional budget process. The figures omit data for the transition quarter (July 1 to September 30, 1976).

3 The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released a major revision to national income accounts in July 2013, which showed somewhat higher levels of national income and thus slightly reduced government spending as a share of GDP. See Stephanie H. McCulla, Alyssa E. Holdren, and Shelly Smith, “Improved Estimates of the National Income and Product Accounts: Results of the 2013 Comprehensive Revision,” Survey of Current Business, September 2013, pp. 14-45, http://bea.gov/scb/pdf/2013/09%20September/0913_comprehensive_nipa_revision.pdf.

4 In some cases, Congress has specified that some funding provided in a nonappropriations act be classified as discretionary. Section 23008 of the CARES Act of 2020 (P.L. 116-136) specified that certain funding in Title B be designated as discretionary, although that measure was an authorizing act.

5 For a broader analysis of discretionary spending, see CRS Report RL34424, The Budget Control Act and Trends in Discretionary Spending, by D. Andrew Austin.

Congressional Research Service

1

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

In some cases, changes in funding levels recorded in historical budget data reflect changes in budgetary concepts or the budgetary treatment of some types of spending. For example, the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-508) changed the budgetary treatment of federal loan and other credit programs starting in FY1992.

Budget Policy and Discretionary Spending Discussions about the appropriate levels of spending for various policy objectives of the federal government have always played an important role in congressional deliberations over funding measures in the last several years. For example, rapid growth in national defense and other security spending in the past decade has played an important role in fiscal discussions. In particular, concerns about the trajectory of fiscal policymeasures. For example, concerns about the trajectory of fiscal policy after the financial crisis of 2007-2009 led to the reestablishment of enforceable statutory caps on discretionary funding in the 2011 Budget Control Act (P.L. 112-25).

Funding for FY2017 was first provided by a continuing resolution (P.L. 114-223) enacted on September 29, 2016, which provided discretionary funding through December 9, 2016, and included a 0.496% across-the-board reduction relative to the previous fiscal year's levels for most federal programs. A second). More recently, the scale of fiscal responses to the COVID-19 pandemic prompted renewed discussions over federal fiscal policy. Moreover, how the growth of social insurance and health program spending, mostly funded through mandatory spending, has shaped the federal budget and its future fiscal trajectory has also been an issue of concern.

Funding for FY2023 was first provided by a continuing resolution (P.L. 114-254) was enacted on December 10, 2016, that extended funding through April 28, 2017. A one-week stopgap funding measure (P.L. 115-30) was enacted on April 28, 2017. An omnibus appropriations measure (P.L. 115-31) enacted on May 5, 2017, provided funding for the remainder of FY2017.

Overview of Recent Discretionary Spending

Spending caps and associated budget enforcement mechanisms, along with modifications of BCA provisions, framed policy discussions during recent budget cycles. Fiscal policy became a central concern of Congress in the wake of the 2007-2009 Great Recession.P.L. 117-180) that included supplemental appropriations to support Ukraine’s defense against the Russian invasion. After two one-week continuing resolutions (P.L. 117-229 and P.L. 117-264) were enacted in December 2022, a final appropriations measure (P.L. 117-328) for FY2023 was enacted on December 29, 2022. According to Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates, the act provided $1,715 billion in discretionary BA.6

The enactment of final FY2023 appropriations at the end of December 2022, rather than before the start of the fiscal year on October 1, 2022, hinders OMB’s ability to estimate current budget year amounts in the Administration’s FY2024 budget submission.7

A 2023 act (Fiscal Responsibility Act; P.L. 118-5) that suspended the federal debt limit also set new statutory caps on discretionary spending for FY2024 and FY2025.

Overview of Recent Discretionary Spending Federal fiscal policy in the past two decades has been shaped by two severe shocks, as noted above and discussed in more detail below.

First, the 2007-2009 financial crisis and the ensuing Great Recession was the most serious economic downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s.8 Government deficits and debt typically rise after serious financial crises and economic downturns for two main reasons. First, tax revenues typically drop during economic downturns. Second, as recession reduces incomes for many households, spending increases due to the effect of "“automatic stabilizers"”—that is, programs that provide benefits linked to income levels or unemployment. In addition, Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA; P.L. 111-5), which combined a package of increased federal funding on), which

6 CBO, CBO Estimate for Divisions A through N of H.R. 2617 (as modified by S.A. 6552), the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, December 21, 2022, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58872. For estimates of mandatory (direct) spending, see CBO Estimate for Divisions O Through MM of H.R. 2617, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, Enacted as P.L. 117-328 on December 29, 2022, January 12, 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58872.

7 OMB, FY2024 Budget, Analytical Perspectives, ch. 4, Budget Process, p. 44, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/ap_4_process_fy2024.pdf.

8 National Bureau of Economic Research, Business Cycle Dating Committee, “June 2009 Business Cycle Trough/End of Last Recession,” September 20, 2010, https://www.nber.org/news/business-cycle-dating-committee-announcement-september-20-2010.

Congressional Research Service

2

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

combined a package of increased federal funding for education, energy, and other areas; greater support for state and local governments; and tax reductions.

The Budget Control Act of 2011

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25; BCA) was enacted in August 2011 in part due to concerns over rising deficits and debt levels.5 The BCA reinstated

Second, the COVID-19 pandemic, the most serious global health emergency in the past century, had profound effects on economic activity, health systems, and finances of households and governments.9

The direct and indirect effects of the 2007-2009 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic both resulted in large increases in federal deficit spending. While federal deficit spending supports economic activity and household incomes, the sharp increases in federal debt levels raised concerns about the sustainability of public finances.

The Budget Control Act of 2011 Fiscal policy became a central concern of Congress in the wake of the 2007-2009 Great Recession. In early 2011, prompted by those concerns, some in Congress sought to constrain discretionary spending in the final FY2011 appropriations measure.10 In August 2011, negotiations over fiscal policy and the debt limit led to the reimposition of spending caps and associated budget enforcement mechanisms that had lapsed after FY2001 through the enactment of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25).

The BCA set statutory caps on discretionary spending, similar to those that had lapsed in 2002, and set up budget enforcement mechanisms designed to achieve $2.1 trillion in savings over the period FY2012-FY2021. Imposition of an11 An initial set of discretionary caps was estimated to save about $900 billion over 10 years. A bipartisan Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, popularlyoften known as the "“Super Committee,"” was chargedtasked with developing a plan to reduce deficits by $1.2 trillion or more.

When that committee did not report areported no plan by a November 2011 deadline, backup budget enforcement measures were triggered, including a January 2013 sequester (a cancellation of budgetary resources by OMB), and a revised set of discretionary caps on funding for defense (defined as the national defense budget function 050) and non-defensenondefense programs (all other) for FY2013-FY2021.612 Those revised caps were to be lowered in each year by an amount calculated by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) according to a formula designed to achieve a pro-ratedprorated share of the $1.2 trillion deficit reduction that a Joint Select Committee plan did not achieve. An annual sequester of non-exemptnonexempt mandatory spending accounts also contributes to those savings.

9 The John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/region/united-states), when it stopped updating its data, estimated that 1.1 million people had died from COVID-19 in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that about 675,000 people died from the Spanish flu in 1918-1919. See CDC, “History of 1918 Flu Epidemic,” webpage, March 21, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-commemoration/1918-pandemic-history.htm.

10 See CRS Report R41771, FY2011 Appropriations in Budgetary Context, by D. Andrew Austin and Amy Belasco. 11 For more information on the BCA, see CRS Report R41965, The Budget Control Act of 2011, by Bill Heniff Jr., Elizabeth Rybicki, and Shannon M. Mahan.

12 Section 302 of the BCA set out procedures for lowering those revised caps by adding § 251A to the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (BBEDCA; P.L. 99-177). In FY2013, the lowering of the BCA caps was implemented through sequestration. See CBO, Sequestration Update Report, August 2012, p. 3, available at http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/08-09-12_SequestrationUpdate.pdf; and OMB, Sequestration Update Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2013, August 20, 2012, p. 13, available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/sequestration/sequestration_update_august2012.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

3

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

The spending trajectory implied by those backup enforcement measures implied discretionary base defense spending would reverthave reverted to a level slightly above its FY2007 level in real dollar terms (i.e., adjusting for inflation but not for growth in population or the economy), while non-defensenondefense discretionary spending would reverthave reverted to a level near its 2003FY2003 level.7 13 Discretionary spending as a share of GDP, ifhad unmodified BCA caps remainremained in place, would declinehave declined to levels well below those seen in recent decades. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) current-lawCBO baseline projections suggestsuggested that discretionary spending would accounthave accounted for 5.3% of GDP in FY2026, two percentage points below its level in FY2007 (7.3%), just before the start of the Great Recession.8

Congress Has14

BCA caps were adjusted to accommodate certain types of spending, such as war spending (designated as “overseas contingency operations”), emergency appropriations, disaster relief, and program integrity initiatives.15 In particular, war-designated funding has been seen as a “relief valve” that has taken budgetary pressure off priority military and international programs.16 Some Members of Congress have argued that war spending cap adjustments weakened fiscal discipline.17

Congress Modified BCA Caps to Mitigate Fiscal Stringency Modified BCA Caps to Mitigate Fiscal Stringency

The stringency of BCA discretionary spending caps and backup enforcement measures prompted Congress and the President to adjust those limits several times to avoid dislocations of federal operations. The Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA; H.J.Res. 59; P.L. 113-67), enacted in December 2013, modified BCA limits for FY2014 and FY2015. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA2015; P.L. 114-74) raised FY2016 and FY2017 cap levels on both categories by $25 billion and FY2017 cap levels by $15 billion. BCA caps for FY2018 through FY2021, however, have not been changed.9 Absent new legislative modifications, those caps will constrain budgetary decisions for FY2018.

BCA caps are adjusted to accommodate certain types of spending, such as war spending, emergency appropriations, disaster relief, and program integrity initiatives.10 In particular, war-designated funding has been seen as a "relief valve" that has taken budgetary pressure off priority military and international programs.11 Some Members of Congress have argued that war spending cap adjustments have weakened fiscal discipline.12

In its budget submission for FY2017, the Obama Administration had proposed raising BCA caps to allow more spending for non-defense and defense priorities.13 For FY2018, the Trump Administration proposed raising the BCA cap on defense (budget function 050) spending by $54 billion and lowering the BCA cap on non-defense by an equal amount. The Administration also proposed slightly smaller increases in the BCA cap on defense and increasingly large reductions in the non-defense cap for future years.14

18 Some journalists and others have referred to sequestration as a reversion to tighter caps on spending after a lapse of a Bipartisan Budget Act provision allowing higher levels of discretionary spending—something unrelated to the formal definition of sequestration.

The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240) delayed the slated FY2013 sequester and reduced its size from $109 billion to $85 billion. ATRA, which also extended certain tax reductions, addressed concerns that the expiration of certain tax cuts and imposition of spending cuts could hinder economic recovery from the Great Recession, avoiding what had been called a “fiscal cliff.”19

13 For details, see CRS congressional distribution memorandum, “The Budget Control Act and Alternate Defense and Nondefense Spending Paths, FY2012-FY2021,” by Amy Belasco and Andrew Austin, November 16, 2012, available to congressional clients upon request. This comparison is made in terms of budget authority. Before passage of ATRA, BCA provisions were slated to bring discretionary base defense spending to its FY2007 level and nondefense spending to near its level in FY2003 or FY2004. Inflation adjustments made using GDP price index.

14 CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, January 24, 2017, Table 1-1, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/52370. CBO baseline projections assume current laws remain in effect and that discretionary spending levels remain constant in inflation-adjusted terms.

15 For BCA caps to be adjusted, emergency funding and war funding (Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism) must be designated on an account-by-account basis by Congress and the President. Cap adjustments for disaster funding are subject to a limit set at a 10-year average of previous disaster funding. The BCA established separate caps for certain program integrity initiatives.

16 See CRS Report R44519, Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status, by Brendan W. McGarry and Emily M. McCabe. Also see Marcus Weisgerber, “‘Magic Money’: DoD’s Overseas Contingency Budget Might Dry Up,” Defense News, June 29, 2014, http://archive.defensenews.com/article/20140629/DEFREG02/306290011/-Magic-Money-DoD-s-Overseas-Contingency-Budget-Might-Dry-Up. Also see archived CRS Report RL33110, The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11, by Amy Belasco.

17 Joe Gould, “Trump Selects OCO-Opponent Mulvaney for OMB,” Defense News, December 19, 2016, http://www.defensenews.com/articles/trump-selects-oco-opponent-mulvaney-for-omb.

18 A CRS congressional distribution memorandum “The Evolution of Budget Control Act of 2011 Caps on Discretionary Spending” is available upon request to congressional clients.

19 ATRA was enacted on January 1, 2013. Budgetary adjustments that affected the FY2013 sequester are described in (continued...)

Congressional Research Service

4

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; H.J.Res. 59; P.L. 113-67), enacted in December 2013 and popularly known as the Murray-Ryan budget agreement, set a pattern for adjusting BCA caps. The BBA 2013 raised BCA FY2014 limits for defense and nondefense by $22.4 billion each and raised FY2015 limits by $9.3 billion each. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74) raised the FY2016 cap levels on both categories by $25 billion and the FY2017 cap levels by $15 billion.

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; H.R. 1892, P.L. 115-123), enacted February 9, 2018, raised the defense cap by about $80 billion for FY2018 and $85 billion for FY2019 and the nondefense cap by about $63 billion for FY2018 and $67 billion for FY2019.20 BBA 2018 also contained several changes in federal social programs and again suspended the debt limit.21

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; H.R. 3877, P.L. 116-37), enacted on August 2, 2019, set discretionary cap levels for FY2020 and FY2021, allowing for higher spending in both the defense and nondefense categories. At the end of FY2021, BCA caps on discretionary spending (BA) expired, although BCA sequestration of nonexempt mandatory spending has been extended.22 Discretionary caps, as noted above, were reinstated for FY2024 and FY2025 by the Fiscal Responsibility Act (P.L. 118-5).

Coronavirus Pandemic and Federal Responses in 2020 and 2021 The COVID-19 pandemic confronted the federal government, like governments around the world, with extraordinary fiscal challenges.23 In part, deficits were pushed upward through “automatic stabilizers,” such as expanded income support payments and diminished tax receipts as household incomes and business profits fell.24 The designation of COVID-19 as a pandemic in mid-March 2020 prompted fiscal policy responses in 2020 and 2021 that increased federal spending and deficits, as percentage of GDP, to levels not seen since World War II.25 Most of the

the CRS congressional distribution memorandum “The Evolution of Budget Control Act of 2011 Caps on Discretionary Spending.”

20 CBO, Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, February 8, 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/bipartisanbudgetactof2018.pdf.

21 See CRS Report R45126, Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123): Brief Summary of Division E—The Advancing Chronic Care, Extenders, and Social Services (ACCESS) Act, coordinated by Paulette C. Morgan. Also see CRS Report R45136, Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123): CHIP, Public Health, Home Visiting, and Medicaid Provisions in Division E, coordinated by Alison Mitchell and Elayne J. Heisler.

22 The sequestration of mandatory spending was extended through the first half of FY2032 for Medicare patient care outlays and through FY2031 for other nonexempt programs. See OMB, FY2024 Budget, Analytical Perspectives, p. 37, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/ap_4_process_fy2024.pdf.

23 World Health Organization (WHO), “WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19,” March 11, 2020, https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020.

24 CBO, “Automatic Stabilizers in the Federal Budget: 2022 to 2032,” October 2022, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58593. Estimated effect of automatic stabilizers in FY2020 was 1.6% of GDP.

25 For 2020, see CBO, “The Budgetary Effects of Laws Enacted in Response to the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic, March and April 2020,” June 2020, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-06/56403-CBO-covid-legislation.pdf (hereinafter CBO, “The Budgetary Effects of Laws Enacted in Response to the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic, March and April 2020”). The total estimated effect on federal deficits from those acts (P.L. 116-123, P.L. 116-127, P.L. 116-136, and P.L. 116-139) was $2.4 trillion, or 11.5% of GDP. For 2021, see CBO, “The Budgetary Effects of Major Laws Enacted in Response to the 2020-2021 Coronavirus Pandemic, December 2020 and March 2021,” September 2021, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-09/57343-Pandemic.pdf (hereinafter CBO, “The Budgetary Effects of Major Laws Enacted in Response to the 2020-2021 Coronavirus Pandemic, December 2020 and March 2021”). The total estimated effect on deficits from those acts (P.L. 116-260, P.L. 117-2) was $2.7 trillion, or 12.2% of GDP.

Congressional Research Service

5

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

federal fiscal response was provided through mandatory spending, and to a lesser extent in revenue reductions.

The CARES Act (P.L. 116-136), enacted in late March 2020, provided an estimated $326 billion in discretionary funding, while providing $988 billion in mandatory spending and $408 billion in revenue reductions. The Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act (P.L. 116-139) provided an additional $162 billion in discretionary funding as well as $321 billion in mandatory spending.26

The final appropriations package for FY2021, enacted in late December 2020, included an estimated $185 billion in discretionary spending, $677 billion in mandatory spending, and $5 billion in revenue decreases. The American Rescue Plan Act (P.L. 117-2) provided $1,803 billion in mandatory funding and $53 billion in revenue reductions, but no discretionary funding.27

Caps on Discretionary Spending Reinstated for FY2024 and FY2025 In June 2023, the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA; P.L. 118-5) suspended the federal debt limit and reestablished statutory caps on discretionary spending for FY2024 and FY2025. Separate caps apply to the defense and nondefense categories.

Federal Budget Data and Concepts Federal Budget Data and Concepts

Figures in this report are based on the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Public Budget Database accompanying the FY2018FY2024 budget release.1528 Table 5.1 in the Historical Tables volume of the FY2018FY2024 budget reports budget authority by function and subfunction, but does not provide a breakdown bybreak down spending into discretionary and mandatory subcomponents.16

29 OMB Budget Data

OMB'’s public budget data generally do not reflect budgetary categories used in the congressional budget process such as emergency-designated funding, the appropriations subcommittee responsible for an account, or distinctions between war and base funding. OMB maintains more detailed budget data for its internal work.

OMB is the official source for historical budget data. CBO estimates, however, are generally more relevant for congressional budget enforcement. Budget data in OMB documents may differ from other budget data for various reasons, although differences in historical data are typically small. For example, appropriations budget documents often reflect scorekeeping adjustments. Budget data issued at a later date may include revisions. In some cases, detailed appropriations data may differ from OMB data, which sometimes do not reflect certain relatively small zero-balance transfers among funds. Differences may also reflect technical differences or different interpretations of federal budget concepts.

Negative Budget Authority

26 CBO, “The Budgetary Effects of Laws Enacted in Response to the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic, March and April 2020.” 27 CBO, “The Budgetary Effects of Major Laws Enacted in Response to the 2020-2021 Coronavirus Pandemic, December 2020 and March 2021.” 28 Data in the OMB Public Budget Database (https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/supplemental-materials/) reconcile to information presented in the Historical Tables (https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historical-tables/) of the FY2024 budget. For a further description and important caveats, see the Public Budget Database User Guide, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/db_guide_fy2024.pdf.

29 OMB, Historical Tables, Table 5.1, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/hist05z1_fy2024.xlsx.

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 27 Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

Negative Budget Authority Within the federal budget concepts, certain inflows, such as offsetting receipts, offsetting collections, some user fees, and "profits"“profits” from federal loan programs, are treated as negative budget authority.17

30

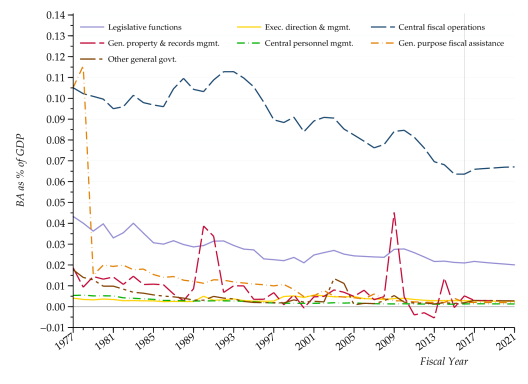

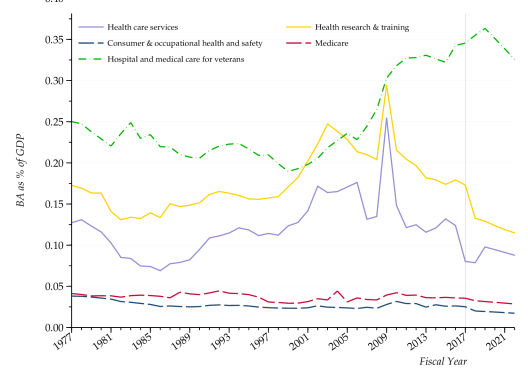

Provisions in appropriations acts that affect mandatory spending programs, known as CHIMPs (changes in mandatory programs) can be counted as negative discretionary spending according to federal budgetary scorekeeping guidelines. For example, a sharp downward spike in proposed spending for subfunction 754 (criminal justice assistance), shown in Figure 17, reflects a CHIMP affecting the Crime Victims Fund. That CHIMP, however, has had little effect on programmatic spending levels. Similarly, a CHIMP affecting the State Children's CHIMP affecting the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) explains a dip in subfunction 551 (health care services) shown in Figure 6.

in Figure 9 for FY2024.31

Scorekeeping adjustments, such as CHIMPs, lead to differences between actual discretionary budget authority totals and limits set by budget enforcement mechanisms, such as §302 allocations or BCA discretionary caps.1832 Scored totals of budget authority—that is, totals that include scorekeeping adjustments and which are used to check conformity to BCA spending limits and other budget enforcement measures—typically diverge from totals that do not include those adjustments.

Federal Credit Programs

Disbursements for federal loan and loan guarantee programs do not appear directly in federal spending data. The federal government has used a form of accrual accounting for loan and loan guarantee programs since passage of the Federal Credit Reform Act (FCRA; Title V of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990; P.L. 101-508) as well as for certain federal retirement programs.1933 OMB calculates net subsidy rates according to FCRA rules for loan and loan guarantee programs. The net subsidy cost is then reflected in federal spending data. In general, FCRA adjustments affect mandatory spending more than discretionary spending because the largest sources of federal credit are mandatory programs.20

34 Comparisons of estimates of federal credit program costs before and after FY1991 should be treated with caution because FCRA changed the budgetary treatment of federal credit programs. For instance, the budgetary costs of loan guarantee programs before FCRA rules came into effect were typically understated because they required no upfront federal disbursements, unlike loan programs. Conversely, the budgetary costs of federal loan programs, which required upfront federal disbursements, did not reflect future repayments. FCRA changes in budgetary treatment of credit programs made loan and loan guarantee programs more comparable. Loan or loan guarantee program cost estimates calculated before FCRA implementation are unlikely to be comparable to estimates calculated afterward.

30 See OMB, FY2024 Budget, Analytic Perspectives, ch. 18, “Offsetting Collections and Offsetting Receipts,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/ap_18_offsetting_fy2024.pdf.

31 OMB, FY2024 Budget, Budget Appendix, CHIP program and financing table, p. 441. 32 Section 302 of the 1974 Congressional Budget Act (P.L. 93-344, as amended) defines spending limits for appropriations subcommittees consistent with levels recommended in a budget resolution. See CRS Report R47388, Enforceable Spending Allocations in the Congressional Budget Process: 302(a)s and 302(b)s, by Drew C. Aherne. More precisely, BCA caps were adjusted upward to reflect those spending categories.

33 See CRS Report RL30346, Federal Credit Reform: Implementation of the Changed Budgetary Treatment of Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees, by James M. Bickley, available to congressional clients upon request.

34 See OMB, FY2024 Budget, Analytic Perspectives, ch. 7, “Credit and Insurance,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/ap_7_credit_fy2024.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 14 Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

FCRA calculations sometimes yield negative net subsidy levels, implying that the federal government appears to make a profit on those loans.2135 FCRA subsidy calculations, however, omit risk adjustments.2236 The true economic cost of federal credit guarantees can be substantially underestimated when risk adjustments are omitted.23

37 Background on Functional Categories

Functional categories provide a means to compare federal funding for activities within broad policy areas that often cut across several federal agencies.2438 Various federal agencies may have closely related or overlapping responsibilities and many agencies have responsibilities in diverse policy areas. Budget data divided along functional categories therefore provide a useful view of federal activities supporting specific national purposes. Superfunction categories, which provide a higher higher-level division of federal activities, are

- National Defense,

- Human Resources,

- Physical Resources, and

- Other Functions.

• National Defense, • Human Resources, • Physical Resources, and • Other Functions.

Figure 1 shows trends in discretionary funding for those superfunctions since FY1977. Budget function categories, grouped by superfunctions, are shown inin Table 1. Net Interest, Allowances, and Undistributed Offsetting Receipts could also be considered as separate categories. Superfunction categories for National Defense, Net Interest, Allowances, and Undistributed Offsetting Receipts coincide with function categories. Trends in net interest are excluded, as federal interest expenditures have been automatically appropriated since 1847.

Allowances, which contain items reflecting technical budget adjustments, and undistributed offsetting receipts are also excluded. Allowances in FY2018 include adjustments to BCA caps, and reflect proposals for spectrum relocation, disability insurance reform, a reduction in improper payments, infrastructure incentives, and war funding (Overseas Contingency Operations/OCO; Global War on Terror/GWOT) for years after FY2018.25

for FY2024 include pandemic fraud prevention and enforcement, allowances for discretionary programs (nondefense), and proposals for spectrum relocation. In this report, the International Affairs function, which OMB includes in the Other Functions superfunction, is listed after National Defense because similar influences can affect both.

Subfunction categories provide a finer division of funding levels within narrower policy areas.26 39 Budget functions do notgenerally play ano role in budget enforcement, although budget legislation mandates that budget resolutions list preferred spending levels by budget function, thus highlighting broad fiscal priorities.27

Historical Spending Trends

Federal spending trends in functional areas are affected by changing assessments of national priorities, evolving international challenges, and economic conditions, as well as changing social characteristics and demographics of the U.S. population. Some of the trends and events that have had dramatic effects on federal spending are outlined below. Other CRS products provide background on more specific policy areas. The discussion of budgetary trends is broken up into three broad categories: defense and international affairs, domestic social programs, and other federal programs.

Spending in the following figures, as noted above, is shown as a percentage of GDP, which controls for the effects of inflation, population growth, and real income growth. A flat line on such graphs indicates that spending in that category is increasing at the same rate as overall economic growth.

|

Superfunction |

Code |

Function / Subfunction |

|

National Defense |

||

|

50 |

National defense |

|

|

51 |

Dept. of Defense-Military |

|

|

53 |

Atomic energy defense activities |

|

|

54 |

Defense-related activities |

|

|

International Affairs |

150 |

International affairs |

|

151 |

Intl. dev. and humanitarian assistance |

|

|

152 |

Intl. security assistance |

|

|

153 |

Conduct of foreign affairs |

|

|

154 |

Foreign information & exchange activities |

|

|

155 |

Intl. financial programs |

|

|

Human Resources |

||

|

500 |

Education, training, employment, and social services |

|

|

501 |

Elementary, secondary, and vocational education |

|

|

502 |

Higher education |

|

|

503 |

Research and general education aids |

|

|

504 |

Training and employment |

|

|

505 |

Other labor services |

|

|

506 |

Social services |

|

|

550 |

Health |

|

|

551 |

Health care services |

|

|

552 |

Health research and training |

|

|

554 |

Consumer and occupational health and safety |

|

|

570 |

Medicare |

|

|

571 |

Medicare |

|

|

600 |

Income security |

|

|

601 |

Gen. retirement & disability insurance (exc. Soc. Sec.) |

|

|

602 |

Federal employee retirement and disability |

|

|

603 |

Unemployment compensation |

|

|

604 |

Housing assistance |

|

|

605 |

Food and nutrition assistance |

|

|

609 |

Other income security |

|

|

650 |

Social security |

|

|

651 |

Social security |

|

|

700 |

Veterans benefits and services |

|

|

701 |

Income security for veterans |

|

|

702 |

Veterans education, training, & rehabilitation |

|

|

703 |

Hospital and medical care for veterans |

|

|

704 |

Veterans housing |

|

|

705 |

Other veterans benefits and services |

|

|

Physical Resources |

||

|

270 |

Energy |

|

|

271 |

Energy supply |

|

|

272 |

Energy conservation |

|

|

274 |

Emergency energy preparedness |

|

|

276 |

Energy information, policy, and regulation |

|

|

300 |

Natural resources and environment |

|

|

301 |

Water resources |

|

|

302 |

Conservation and land management |

|

|

303 |

Recreational resources |

|

|

304 |

Pollution control and abatement |

|

|

306 |

Other natural resources |

|

|

370 |

Commerce and housing credit |

|

|

371 |

Mortgage credit |

|

|

372 |

Postal service |

|

|

373 |

Deposit insurance |

|

|

376 |

Other advancement of commerce |

|

|

400 |

Transportation |

|

|

401 |

Ground transportation |

|

|

402 |

Air transportation |

|

|

403 |

Water transportation |

|

|

407 |

Other transportation |

|

|

450 |

Community and regional development |

|

|

451 |

Community development |

|

|

452 |

Area and regional development |

|

|

453 |

Disaster relief and insurance |

|

|

Other Functions |

||

|

250 |

General science, space, and technology |

|

|

251 |

General science and basic research |

|

|

252 |

Space flight, research & supporting activities |

|

|

350 |

Agriculture |

|

|

351 |

Farm income stabilization |

|

|

352 |

Agricultural research and services |

|

|

750 |

Administration of justice |

|

|

751 |

Federal law enforcement activities |

|

|

752 |

Federal litigative and judicial activities |

|

|

753 |

Federal correctional activities |

|

|

754 |

Criminal justice assistance |

|

|

800 |

General government |

|

|

801 |

Legislative functions |

|

|

802 |

Executive direction and mgmt. |

|

|

803 |

Central fiscal operations |

|

|

804 |

General property and records mgmt. |

|

|

805 |

Central personnel mgmt. |

|

|

806 |

General purpose fiscal assistance |

|

|

808 |

Other general government |

|

|

809 |

Deductions for offsetting receipts |

|

|

Net Interest |

||

|

900 |

Net interest |

|

|

901 |

Interest on Treasury debt securities (gross) |

|

|

902 |

Interest received by on-budget trust funds |

|

|

903 |

Interest received by off-budget trust funds |

|

|

908 |

Other interest |

|

|

909 |

Other Investment and income |

|

|

Allowances |

||

|

920 |

Allowances |

|

|

922 |

| |

|

923 |

Infrastructure Initiative |

|

|

924 |

Adjustment for BCA Cap on Non-Security Spending |

|

|

925 |

Additional FY2017 Request |

|

|

926 |

Spectrum Relocation |

|

|

927 |

Disability Insurance Reforms |

|

|

928 |

Reductions in Improper Payments Government-wide |

|

|

929 |

Plug for Outyear War Costs |

|

|

Undistributed Offsetting Receipts |

||

|

950 |

Undistributed offsetting receipts |

|

|

951 |

Employer share, employee retirement (on-budget) |

|

|

952 |

Employer share, employee retirement (off-budget) |

|

|

953 |

Rents & royalties on the Outer Continental Shelf |

|

|

954 |

Sale of major assets |

|

|

959 |

Other undistributed offsetting receipts |

Source: CRS, based on OMB data.

Notes: Allowances subfunctions can change from one year to the next.

a.

Backup budget enforcement measures established by the BCA came into force after the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction did not report a plan in November 2011.

35 For example, some Federal Housing Administration mortgage programs and some federal student loan programs have been estimated in some years to yield negative net subsidies.

36 While the FCRA calculations include estimates of default costs, they do not discount more volatile income flows, as a private firm would. See CRS Report R44193, Federal Credit Programs: Comparing Fair Value and the Federal Credit Reform Act (FCRA), by Raj Gnanarajah.

37 U.S. Congressional Budget Office, Estimating the Value of Subsidies for Federal Loans and Loan Guarantees, August 2004, available at http://cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=5751.

38 See CRS Report 98-280, Functional Categories of the Federal Budget, by Bill Heniff Jr. 39 Table 1 largely follows the ordering of functions in the OMB Historical Tables volume. See OMB, FY2024 Budget, Historical Tables, Table 3.1, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/hist03z1_fy2024.xlsx. The ordering of some items was changed to organize the discussion in a thematically consistent manner. As noted in the text, the international affairs function was grouped with the national defense function, as those categories are affected by common influences.

Congressional Research Service

8

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

highlighting broad fiscal priorities.40 Caps on discretionary spending set by BCA and FRA, as noted above, do define the “revised security category” as “discretionary appropriations in budget function 050.”41

Figure 1. Discretionary Funding by Budget Superfunction, FY1977-FY2028

Source: CRS, based on OMB data from the FY2024 budget submission. Notes: FY2023 levels are estimated. FY2024-FY2028 levels reflect Administration proposals and projections. See OMB budget documents for further caveats.

40 2 U.S.C. 632(a)(4). 41 2 U.S.C. 900(c)(4)(D).

Congressional Research Service

9

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

Table 1. Budget Function Categories by Superfunction

Superfunction

Code

Function / Subfunction

National Defense

50

National defense

51

Dept. of Defense-Military

53

Atomic Energy Defense Activities

54

Defense-Related Activities

International Affairs

150

International affairs

151

Intl. Dev. and Humanitarian Assistance

152

Intl. Security Assistance

153

Conduct of Foreign Affairs

154

Foreign Information & Exchange Activities

155

International Financial Programs

Human Resources

500

Education, training, employment, and social services

501

Elementary, Secondary, and Vocational Education

502

Higher Education

503

Research and General Education Aids

504

Training and Employment

505

Other Labor Services

506

Social services

550

Health

551

Health Care Services

552

Health Research and Training

554

Consumer and Occupational Health and Safety

570

Medicare

571

Medicare

600

Income security

601

Gen. retirement & disability insurance (exc. Soc. Sec.)

602

Federal employee retirement and disability

603

Unemployment compensation

604

Housing assistance

605

Food and nutrition assistance

609

Other income security

650

Social security

651

Social security

700

Veterans benefits and services

701

Income security for veterans

702

Veterans education, training, & rehabilitation

703

Hospital and medical care for veterans

704

Veterans housing

705

Other veterans benefits and services

Physical Resources

270

Energy

271

Energy supply

272

Energy conservation

274

Emergency energy preparedness

276

Energy information, policy, and regulation

Congressional Research Service

10

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

Superfunction

Code

Function / Subfunction

300

Natural resources and environment

301

Water resources

302

Conservation and land management

303

Recreational resources

304

Pol ution control and abatement

306

Other natural resources

370

Commerce and housing credit

371

Mortgage credit

372

Postal service

373

Deposit insurance

376

Other advancement of commerce

400

Transportation

401

Ground transportation

402

Air transportation

403

Water transportation

407

Other transportation

450

Community and regional development

451

Community development

452

Area and regional development

453

Disaster relief and insurance

Other Functions

250

General science, space, and technology

251

General science and basic research

252

Space flight, research & supporting activities

350

Agriculture

351

Farm income stabilization

352

Agricultural research and services

750

Administration of justice

751

Federal law enforcement activities

752

Federal litigative and judicial activities

753

Federal correctional activities

754

Criminal justice assistance

800

General government

801

Legislative functions

802

Executive direction and mgmt.

803

Central fiscal operations

804

General property and records mgmt.

805

Central personnel mgmt.

806

General purpose fiscal assistance

808

Other general government

809

Deductions for offsetting receipts

Net Interest

900

Net interest

901

Interest on Treasury debt securities (gross)

902

Interest received by on-budget trust funds

903

Interest received by off-budget trust funds

908

Other interest

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 17 link to page 18 Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

Superfunction

Code

Function / Subfunction

909

Other Investment and income

Allowances

920

Allowances

922

Reductions for Joint Committee Enforcement (Nondefense)

923

Pandemic Fraud Prevention and Enforcement

924

Allowance for Discretionary Programs (Nondefense)

926

Spectrum Relocation

Undistributed Offsetting

Receipts

950

Undistributed offsetting receipts

951

Employer share, employee retirement (on-budget)

952

Employer share, employee retirement (off-budget)

953

Rents & royalties on the Outer Continental Shelf

954

Sale of major assets

959

Other undistributed offsetting receipts

Source: CRS, based on OMB data (OMB, FY2024 Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Table 24-1, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/24-1_fy2024.xlsx). Notes: Allowances subfunctions can change from one year to the next.

Historical Spending Trends Federal spending trends in functional areas are affected by changing assessments of national priorities, evolving international challenges, and economic conditions, as well as changing social characteristics and demographics of the U.S. population. Some of the trends and events that have had dramatic effects on federal spending are outlined below. Other CRS products provide background on more specific policy areas. The discussion of budgetary trends is broken up into three broad categories: defense and international affairs, domestic social programs, and other federal programs.

Spending in the following figures, as noted above, is shown as a percentage of GDP, which controls for the effects of inflation, population growth, and real income growth. A flat line on such graphs indicates that spending in that category is increasing at the same rate as overall economic growth.

Defense and International Affairs Defense and International Affairs

The National Defense (050) and International Affairs (150) budget functions have been the categories most affected by larger changes in the geopolitical role of the United States.

Cold War, Peace Dividend, and the Global War on Terror

The allocation of discretionary spending between defense and non-defensenondefense programs is one reflection of changing federal priorities over timetime. Figure 1 2 shows defense and non-defense nondefense discretionary funding as a percentage of GDP. Figure 3 shows defense spending by major title, including Military Personnel (Mil Pers), Procurement, Operations and Maintenance (O&M), and Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RTD&E).42

42 Defense appropriations acts typically also contain titles for Revolving and Management Funds, Other DOD (continued...)

Congressional Research Service

12

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

Figure 2.

discussed elsewhere.

Relations between the United States and its allies on one hand, and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and its allies on the other were the dominant security concern in the half century following the Second World War. In the early 1970s, U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War wound down, while the United States and the USSR moved toward detente, permitting a thaw in Cold War relations between the two superpowers and a reduction in defense spending relative to the size of the economy.28

Following intervention by the USSR in Afghanistan in 1979, military spending increased sharply.29 Defense spending continued to increase until 1986, as concern shifted to domestic priorities and the desire to reduce large budget deficits. The 43

Programs, and Related Agencies. Military Construction/Veterans Administration appropriations acts typically contain titles for Military Construction and Family Housing.

43 For a history of deficit finance and American wars, see Robert D. Hormats, The Price of Liberty, (New York: Times Books, 2007); or Steven A. Bank, Kirk J. Stark, and Joseph J. Thorndike, War and Taxes, (Washington, D. C.: Urban Institute, 2008). Also see Rosella Cappella Zielinski, How States Pay for Wars (New York: Cornell University Press, 2016); and Sarah Kreps, Taxing Wars: The American Way of War Finance and the Decline of Democracy (Oxford, 2018).

Congressional Research Service

13

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

Figure 3. Defense Discretionary BA by Major Title, FY1977-FY2028

Source: CRS, based on OMB data from the FY2024 budget submission. Notes: The four titles with the highest funding levels are shown.

In 1979, during the Jimmy Carter Administration, military spending increased sharply following intervention by the USSR in Afghanistan and the Iranian hostage crisis.44 The Ronald W. Reagan Administration increased defense spending further, with procurement costs rising more sharply than other categories.45

Defense spending continued to increase until 1986, as concern shifted to domestic priorities, the desire to reduce large budget deficits, and concerns about inflated procurement costs.46 The collapse in 1989 of most of the Warsaw Pact governments in Central and Eastern Europe and the 1990-1991 disintegration of the Soviet Union was followed by a reduction in federal defense spending, allowing a "“peace dividend"” that relaxed fiscal pressures.30

47 O&M costs, however, fell

44 For one view of budgetary politics in the early 1980s, see David Stockman, The Triumph of Politics (New York: Harper & Row, 1986). Also see James M. Poterba, David Stockman, and Charles Schultze, “Budget Policy,” in American Economic Policy in the 1980s, NBER, pp. 235-292.

45 Stockman (1986), pp. 105-109. 46 Airon A. Mothershed, “The $435 Hammer and $600 Toilet Seat Scandals: Does Media Coverage of Procurement Scandals Lead to Procurement Reform?” Public Contract Law Journal, vol. 41, no. 4 (2012), pp. 855-880, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41635361.

47 The Warsaw Treaty Organization established in 1955, included Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, the German Democratic Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and the Soviet Union.

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 18 Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

more slowly after the mid-1980s than other costs (as seen in Figure 3) and rose more quickly after 2000.

The attacks of September 11, 2001, were followed by sharp increases in homeland security spending. Defense spending also increased significantly with the start of the Afghanistan war in October 2001 and the Iraq war in March 2003.31 U.S. combat troops were withdrawn from Iraq in December 2011, and President Obama had announced48 Rising levels of violence and instability in Iraq in 2006 led President George W. Bush to send an additional “surge” of troops.49 In 2008, the U.S. and Afghan governments negotiated a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) that set a December 2011 deadline for the withdrawal of most U.S. combat troops.50 A smaller number of U.S. troops returned in 2014 to combat the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).51

President Barack H. Obama announced that additional troops would be sent to Afghanistan to prevent a collapse of its government. In 2013 and 2014, President Obama stated that most U.S. troops would be withdrawn from Afghanistan by the end of 2014.3252 In November 2014, however, President Obama announced an extension of operations in Afghanistan.33 The Obama Administration also noted challenges posed by Russia, which annexed the Crimean peninsula and sponsored military operations in eastern Ukraine; by the so-called Islamic State (IS; also known as ISIL, ISIS, or Da'esh); and by cyberattacks—hostile incursions of computer networks.34

President Trump, in his FY2018 budget submission, called for a $54 billion increase in defense programs to be offset by reductions in non-defense discretionary spending.

53 In February 2020, the Trump Administration signed an agreement with the Taliban that set a May 2021 deadline for the withdrawal of U.S. military forces.54 The collapse of Afghan forces in August 2021 forced the withdrawal of remaining U.S. personnel.55

The invasion of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula and eastern portions of Ukraine in March 2014 marked a turning point in U.S.-Russian relations, although those events had no material effect on defense spending.56 The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, however, prompted a more robust response. As of July 2023, the United States had provided $43 billion in security aid since the 2022 Russian invasion began.57

48 See archived CRS Report RL33110, The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11, by Amy Belasco, available to congressional clients upon request. The Afghan and Iraq wars, along with other related activities, were often called the Global War on Terror (GWOT) and later Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO). The OCO category was created in 1997 to fund activities in Kosovo and Southwest Asia. See DOD Comptroller, “Overseas Contingency Operations Transfer Fund,” in the FY2000 DOD Budget Justification, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2000/budget_justification/pdfs/01_Operation_and_Maintenance/fy00pb_ocotf.pdf. Also see CRS In Focus IF10143, Foreign Affairs Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) Funding: Background and Current Status, by Emily M. McCabe.

49 White House, “President’s Address to the Nation,” January 10, 2007, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2007/01/20070110-7.html. Also see Timothy A. Sayle et al., The Last Card: Inside George W. Bush’s Decision to Surge in Iraq, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press, 2019), https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctvfc522t.

50 See archived CRS Report R40011, U.S.-Iraq Withdrawal/Status of Forces Agreement: Issues for Congressional Oversight, by R. Chuck Mason.

51 Stacie L. Pettyjohn, “Can Iraq Evict U.S. Forces?” January 6, 2020, https://www.rand.org/blog/2020/01/can-iraq-evict-us-forces.html.

52 See CRS Report RL30588, Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, by Kenneth Katzman. Also see Kevin Marsh, “Obama’s Surge: A Bureaucratic Politics Analysis of the Decision to Order a Troop Surge in the Afghanistan War,” Foreign Policy Analysis, vol. 10, no. 3 (July 2014), pp. 265-288.

53 Mark Mazzetti and Eric Schmitt, “In a Shift, Obama Extends U.S. Role in Afghan Combat,” New York Times, November 21, 2014.

54 U.S. Department of State, After Action Review on Afghanistan: January 2020-August 2021, June 30, 2023, p. 11, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/State-AAR-AFG.pdf.

55 Ibid., p. 85. 56 Katya Gorchinskaya, “A Brief History of Corruption in Ukraine: the Yanukovych Era,” Eurasianet, June 3, 2020, https://eurasianet.org/a-brief-history-of-corruption-in-ukraine-the-yanukovych-era. Also see Serhiy Kudelia, “The House that Yanukovych Built: the Maidan and Beyond,” Journal of Democracy, vol. 25 (2014). 57 U.S. DOD, “Fact Sheet on U.S. Security Assistance to Ukraine,” July 18, 2023, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Jul/19/2003263170/-1/-1/1/UKRAINE-FACT-SHEET.PDF. Also see CRS In Focus IF12040, U.S. Security Assistance to Ukraine, by Christina L. Arabia, Andrew S. Bowen, and Cory Welt.

Congressional Research Service

15

link to page 20

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

Potential security and diplomatic challenges posed by the Peoples’ Republic of China (PRC) have emerged as a leading strategic concern.58 Other strategic priorities include broader challenges such as climate change and terrorism, as well as shaping international rules that address potential policy disputes over trade and technology.59

Defense Funding Outside of the Department of Defense

Figure 4 Defense Funding Outside of the Department of Defense

Figure 2 shows subfunctions within the National Defense (050) budget function. The Department of Defense (DOD)-Military (051) subfunction accounts for over 95% of that funding. Almost all of the Atomic Energy Defense Activitiesof the atomic energy defense activities (053) subfunction supports operations within the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). About two-thirds of that funding supports the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and the remainder funds environmental clean-up of weapons production and research sites, along with other related activities. Much smaller amounts support the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board and site remediation activities of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The defense-related activities (54) subfunction comprises a variety of activities outside of DOD. In recent years, funding for counterterrorism activities within the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has accounted for almost two-thirds of all funding within this subfunction and about half of the FBI's total discretionary funding.

The Defense-Related Activities (54) subfunction comprises a variety of activities outside of DOD. In recent years, funding for counterterrorism activities within the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has accounted for almost two-thirds of all funding within this subfunction and about half of the FBI’s total discretionary funding.

International Affairs

Figure 5 International Affairs

Figure 3 shows levels of budget authority allocated to international affairs (budget function 150) as a share of GDP. Spending for activities within the international affairs budget function has fluctuated in response to changes in U.S. foreign relations and federal priorities. International security assistancepolicy and national security and economic priorities.

Figure 5. International Affairs (150) Subfunctions

Discretionary budget authority as a percentage of GDP, FY1977-FY2028

Source: CRS, based on OMB data from FY2024 budget submission. Notes: FY2023 levels are estimated. FY2024-FY2028 levels reflect Administration proposals and projections. See OMB budget documents for further caveats.

International Security Assistance rose sharply in the late 1970s and early 1980s, in large part due to foreign military financing support provided to Israel and Egypt following the 1979 Camp

Congressional Research Service

17

link to page 23 Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

David Accords.60David Accords.35 The Economic Support Fund (ESF), which provides financial support to promote political and socioeconomic stability within a range of countries of strategic importance to the United States, also grew rapidly in the same time period.3661 Funding for security assistance fell after the collapse of the Warsaw Pact governments in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The level of funding for International Development and Humanitarian AssistanceUnion in 1991.

The level of funding for international development and humanitarian assistance fell from about 0.2% of GDP in the late 1970s to less than 0.1% of GDP in the 1990s. The George W. Bush Administration increased funding for international development and humanitarian assistance in International Development and Humanitarian Assistance in the early 2000s through initiatives such as the President'’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which has supported programs to stem the spread of AIDS and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and southSouth Asia, and creation of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), which sought to use financial incentives to spur economic development and reform.37 While funding for the MCC was curtailed during the Barack seeks to spur economic growth in relatively well-governed developing countries.62 During the Obama Administration, funding for international development and humanitarian assistance International Development and Humanitarian Assistance hovered around 0.15% of GDP, about midway between levels seen in the 1970s and in the 1990s. More recently, largely as a result of U.S. responses to the COVID-19 pandemic starting in 2020 and Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine in 2022, International Development and Humanitarian Assistance has risen. In 2022, International Development and Humanitarian Assistance as a share of GDP peaked at more than 0.18%, a level last seen around 2009.

Costs of conducting foreign affairs, relative to GDP, rose during the first decade of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, but largely declined between FY2012 and FY2019. Following the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, and Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Function 150 relative to GDP has increased. hovered around 0.15% of GDP, about midway between levels seen in the 1970s and in the 1990s.

Fluctuations in the level of funding for international financial programs have been dominated by occasional quota payments by the United States in the International Monetary Fund (IMF).38 The U.S. government receives special drawing rights (SDRs), which contribute to the capital base of the IMF, in exchange for those quota payments. The budgetary treatment of IMF quota payments has not been consistent. Since 2009, the budgetary costs of IMF quota payments have been calculated by an evaluation of the risks that non-payment of loans made by the IMF could reduce the value of U.S. investments in the IMF.39 Thus, the spikes in funding for international financial programs seen in Figure 3 reflect changes in budgetary concepts rather than changes in policy or funding levels.

Costs of conducting foreign affairs, relative to GDP, rose during the first decade of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, but have been declining since FY2012. Heightened concerns over security of diplomatic facilities and personnel have also contributed to Heightened concerns over security of diplomatic facilities and personnel have also contributed to overall higher funding levels since 2001.

Domestic Social Programs

This section discusses budgetary trends among domestic social programs. In the past two decades, federal responses to the attacks of September 11, 2001, the 2007-2009 financial crisis and ensuingand the Great Recession, and the COVID-19 pandemic have had the most prominent effects of spending trends for most categories of federal domestic spending.

Non-Defense Security and Non-Securityspending. Figure 6 shows discretionary funding trends for budget functions within the Human Resources superfunction.

60 U.S. General Accounting Office (now Government Accountability Office; GAO), Military Sales to Israel and Egypt: DOD Needs Stronger Controls Over U.S.-Financed Procurements, GAO/NSIAD-93-184, July 1993, http://www.gao.gov/assets/160/153579.pdf.

61 For more on U.S. foreign assistance history and trends, see CRS Report R40213, Foreign Assistance: An Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy, by Emily M. McCabe and Nick M. Brown.

62 See CRS Report RL32427, Millennium Challenge Corporation: Overview and Issues, by Nick M. Brown.

Congressional Research Service

18

link to page 24

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

Figure 6. Discretionary Funding for Human Resources Functions

Discretionary budget authority as a percentage of GDP, FY1977-FY2028

Source: CRS, based on OMB data from FY2024 budget submission. Notes: FY2023 levels are estimated. FY2024-FY2028 levels reflect Administration proposals and projections. See OMB budget documents for further caveats.

Nondefense Security and Nonsecurity Spending Diverge After 9/11

Spending Diverge After 9/11

Domestic spending (i.e., non-defensenondefense spending excluding international affairs) increased after the attacks of September 11, 2001, after having fallen for much of the 1990s. Most of that increase in domestic spending occurred in areas related to non-defensenondefense security spending, as the federal government overhauled airport security procedures, and then established the Department of Homeland Security. Since 2001, several definitions of "“security spending"” have been used, most recently in the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA).4063 Figure 4 7 shows funding trends divided by BCA security and non-security categories.

nonsecurity categories.

63 The Obama Administration defined security spending in its FY2012 budget as funding for Department of Defense-Military (subfunction 051); the Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration; International Affairs (function 150, which includes State Department and related agencies); the Department of Homeland Security; and the Department of Veterans Affairs. The BCA defined security similarly, except that it included all military activities within the Department of Defense excluding war funding (i.e., defined by department rather than by subfunction), and also included the Intelligence Community Management Account.

Congressional Research Service

19

Discretionary Budget Authority by Subfunction: An Overview

Figure 7. Security and Nonsecurity Funding Trends

Budget Authority as a Percentage of GDP, FY1977-FY2028