Water Infrastructure Financing: History of EPA Appropriations

The principal federal program to aid municipal wastewater treatment plant construction is authorized in the Clean Water Act (CWA). Established as a grant program in 1972, it now capitalizes state loan programs through the clean water state revolving loan fund (CWSRF) program. Since FY1972, appropriations have totaled $98 billion.

In 1996, Congress amended the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA, P.L. 104-182) to authorize a similar state loan program for drinking water to help systems finance projects needed to comply with drinking water regulations and to protect public health. Since FY1997, appropriations for the drinking water state revolving loan fund (DWSRF) program have totaled $23 billion.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administers both SRF programs, which annually distribute funds to the states for implementation. Funding amounts are specified in the State and Tribal Assistance Grants (STAG) account of EPA annual appropriations acts. The combined appropriations for wastewater and drinking water infrastructure assistance have represented 25%-32% of total funds appropriated to EPA in recent years.

Prior to CWA amendments in 1987 (P.L. 100-4), Congress provided wastewater grant funding directly to municipalities. The federal share of project costs was generally 55%; state and local governments were responsible for the remaining 45%. The 1987 amendments replaced this grant program with the SRF program. Local communities are now often responsible for 100% of project costs, rather than 45%, as they are required to repay loans to states. The greater financial burden of the act’s loan program on some cities has caused some to seek continued grant funding.

Although the CWSRF and DWSRF have largely functioned as loan programs, both allow the implementing state agency to provide “additional subsidization” under certain conditions. Since its amendments in 1996, the SDWA has authorized states to use up to 30% of their DWSRF capitalization grants to provide additional assistance, such as forgiveness of loan principal or negative interest rate loans, to help disadvantaged communities. America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (AWIA; P.L. 115-270) increased this proportion to 35% while conditionally requiring states to use at least 6% of their capitalization grants for these purposes.

Congress amended the CWA in 2014, adding similar provisions to the CWSRF program. In addition, appropriations acts in recent years have required states to use minimum percentages of their allotted SRF grants to provide additional subsidization.

Final full-year appropriations were enacted as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, FY2019 (P.L. 116-6), on February 15, 2019. The act provided $1.694 billion for the CWSRF and $1.163 billion for the DWSRF program, nearly identical to the FY2018 appropriations. The FY0219 act provided $68 million for the WIFIA program, a $5 million increase from the FY2018 appropriation.

Compared to the FY2019 appropriation levels, the Trump Administration’s FY2020 budget request proposes to decrease the appropriations for the CWSRF, DWSRF, and WIFIA programs by 34%, 26%, and 63%, respectively.

Water Infrastructure Financing: History of EPA Appropriations

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Summary of Water Infrastructure Appropriations

- Historical Funding Developments

- Special Purpose Project Grants

- Local Cost Share on Special Purpose Grants

- Additional Subsidization

- Noninfrastructure Grants

- Appropriations Chronology

- FY1986, FY1987

- FY1988

- FY1989

- FY1990

- FY1991

- FY1992

- FY1993

- FY1994

- FY1995

- FY1996

- FY1997

- FY1998

- FY1999

- FY2000

- FY2001

- FY2002

- FY2003

- FY2004

- FY2005

- FY2006

- FY2007

- FY2008

- FY2009

- FY2009 Supplemental Appropriations, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

- FY2010

- FY2011

- FY2012

- FY2013

- FY2014

- FY2015

- FY2016

- FY2017

- FY2018

- FY2019

- FY2020

Summary

The principal federal program to aid municipal wastewater treatment plant construction is authorized in the Clean Water Act (CWA). Established as a grant program in 1972, it now capitalizes state loan programs through the clean water state revolving loan fund (CWSRF) program. Since FY1972, appropriations have totaled $98 billion.

In 1996, Congress amended the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA, P.L. 104-182) to authorize a similar state loan program for drinking water to help systems finance projects needed to comply with drinking water regulations and to protect public health. Since FY1997, appropriations for the drinking water state revolving loan fund (DWSRF) program have totaled $23 billion.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administers both SRF programs, which annually distribute funds to the states for implementation. Funding amounts are specified in the State and Tribal Assistance Grants (STAG) account of EPA annual appropriations acts. The combined appropriations for wastewater and drinking water infrastructure assistance have represented 25%-32% of total funds appropriated to EPA in recent years.

Prior to CWA amendments in 1987 (P.L. 100-4), Congress provided wastewater grant funding directly to municipalities. The federal share of project costs was generally 55%; state and local governments were responsible for the remaining 45%. The 1987 amendments replaced this grant program with the SRF program. Local communities are now often responsible for 100% of project costs, rather than 45%, as they are required to repay loans to states. The greater financial burden of the act's loan program on some cities has caused some to seek continued grant funding.

Although the CWSRF and DWSRF have largely functioned as loan programs, both allow the implementing state agency to provide "additional subsidization" under certain conditions. Since its amendments in 1996, the SDWA has authorized states to use up to 30% of their DWSRF capitalization grants to provide additional assistance, such as forgiveness of loan principal or negative interest rate loans, to help disadvantaged communities. America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (AWIA; P.L. 115-270) increased this proportion to 35% while conditionally requiring states to use at least 6% of their capitalization grants for these purposes.

Congress amended the CWA in 2014, adding similar provisions to the CWSRF program. In addition, appropriations acts in recent years have required states to use minimum percentages of their allotted SRF grants to provide additional subsidization.

Final full-year appropriations were enacted as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, FY2019 (P.L. 116-6), on February 15, 2019. The act provided $1.694 billion for the CWSRF and $1.163 billion for the DWSRF program, nearly identical to the FY2018 appropriations. The FY0219 act provided $68 million for the WIFIA program, a $5 million increase from the FY2018 appropriation.

Compared to the FY2019 appropriation levels, the Trump Administration's FY2020 budget request proposes to decrease the appropriations for the CWSRF, DWSRF, and WIFIA programs by 34%, 26%, and 63%, respectively.

Introduction

The Clean Water Act (CWA)1 authorizes the principal federal program to aid municipal wastewater treatment plant construction and related eligible activities. Congress established this program in the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972 (P.L. 92-500) (although prior versions of the act had authorized less ambitious grants assistance since 1956). Title II of P.L. 92-500 authorized grants to states for wastewater treatment plant construction under a program administered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Federal funds were provided through annual appropriations under a state-by-state allocation formula contained in the act itself. States used their allotments to make grants to cities to build or upgrade wastewater treatment plants, supporting the overall objectives of the act: restoring and maintaining the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters. The federal share of project costs, originally 75% under P.L. 92-500, was reduced to 55% in 1981.

By the mid-1980s, there was considerable policy debate between Congress and the Administration over the future of the act's construction grants program and, in particular, the appropriate federal role in funding municipal water infrastructure projects. Through FY1984, Congress had appropriated nearly $41 billion under this program, representing the largest nonmilitary public works programs since the Interstate Highway System. The grants program was a target of budget cuts in the Reagan Administration, which sought to redirect budgetary priorities in part to sort out the appropriate roles of federal, state, and local governments in a number of domestic policy areas, including water pollution control. The Administration's rationale included several points:

- The original intent of the program to address the backlog of sewage treatment needs had been virtually eliminated by the mid-1980s.

- Most remaining projects (such as small, rural systems) were believed to pose little environmental threat and were not appropriate federal responsibilities.

- State and local governments, in the Administration's view, were fully capable of running construction programs and have a clear responsibility to construct treatment capacity to meet environmental objectives that were primarily established by states.

Thus, the Reagan Administration sought a phaseout of the act's construction grants program by 1990. Many states and localities supported the idea of phasing out the grants program, since many were critical of what they viewed as burdensome rules and regulations that accompanied the federal grant money. However, they sought a longer transition and ample flexibility to set up long-term financing to promote state and local self-sufficiency.

Congress's response to this debate was contained in 1987 amendments to the act (P.L. 100-4, the Water Quality Act of 1987). It authorized $18 billion over nine years for sewage treatment plant construction, through a combination of the Title II grants program and a new State Water Pollution Control Revolving Funds program—hereinafter the clean water state revolving fund (CWSRF) program. Under the new program, in CWA Title VI, federal grants would be provided as seed money for state-administered loans to build sewage treatment plants and, eventually, other water quality projects. Cities, in turn, would repay loans to the state, enabling a phaseout of federal involvement while the state built up a source of capital for future investments. Under the amendments, the CWSRF program was phased in beginning in FY1989 (in FY1989 and FY1990, appropriations were split equally between Title II and Title VI grants) and entirely replaced the previous Title II program in FY1991. The intention was that states would have flexibility to set priorities and administer funding, while federal aid would end after FY1994.

The CWSRF authorizations for appropriations provided in the 1987 amendments expired in FY1994, but pressure to extend federal funding has continued, in part because, although Congress has appropriated $98 billion in CWA Title II and Title VI wastewater infrastructure assistance since 1972, funding needs remain high: According to the most recent formal estimate by EPA and states (prepared in 2016), an additional $271 billion nationwide is needed over the next 20 years for all types of projects eligible for funding under the act.2 Congress has continued to appropriate funds, and continued to assist states and localities in meeting wastewater infrastructure needs and complying with CWA requirements.

In 1996, Congress established a parallel program under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) to help communities finance projects needed to comply with federal drinking water regulations.3 Funding support for drinking water occurred for several reasons. First, until the 1980s, the number of drinking water regulations was fairly small, and public water systems often did not need to make large investments in treatment technologies to meet those regulations. Second, good quality drinking water traditionally has been available to many communities at relatively low cost. By comparison, essentially all communities have had to construct or upgrade sewage treatment facilities to meet the requirements of the CWA.

Over time, drinking water circumstances changed, as communities grew, and commercial, industrial, agricultural, and residential land-uses became more concentrated, thus resulting in more contaminants reaching drinking water sources. Moreover, as the number of federal drinking water standards has increased, many communities have found that their water may not be as good as once thought and that additional treatment technologies are required to meet the new standards and protect public health. Between 1986 and 1996, for example, the number of regulated drinking water contaminants grew from 23 to 83, and EPA and the states expressed concern that many of the nation's 52,000 small community water systems were likely to lack the financial capacity to meet the rising costs of SDWA compliance. According to the most recent EPA-state survey (issued in 2018), future funding needs for projects to treat and deliver public drinking water supplies in the United States are $473 billion over the next 20 years.4

Congress responded to these concerns by enacting the 1996 SDWA Amendments (P.L. 104-182), which authorized a drinking water state revolving loan fund (DWSRF) program to help systems finance projects needed to comply with SDWA regulations and to protect public health. This program, fashioned after the CWSRF program, authorizes EPA to make grants to states to capitalize DWSRFs which states then use to make loans to public water systems. Appropriations for the program were authorized at $599 million for FY1994 and $1 billion annually for FY1995 through FY2003.

Capitalization grants for DWSRF programs were provided for the first time in FY1997. Although the authorizations for appropriations expired in FY2003, Congress continued to provide funding for the program in annual appropriations, totaling $23 billion through FY2019. America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (AWIA; P.L. 115-270), enacted on October 23, 2018, reauthorized appropriations for the DWSRF at $1.17 billion in FY2019, $1.30 billion in FY2020, and $1.95 billion in FY2021.5

The first section of this report includes a table that summarizes the history of appropriations for both wastewater and drinking water infrastructure programs. The next section discusses several historical developments in water infrastructure funding. The last section contains a detailed chronology of congressional activity regarding wastewater and drinking water infrastructure funding for each fiscal year since the 1987 CWA amendments.

Summary of Water Infrastructure Appropriations

Table 1 summarizes funding for the wastewater and drinking infrastructure programs since enactment of the 1987 CWA amendments (P.L. 100-4). Funding for these EPA programs is contained in the appropriations act providing funds for the Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies.6 Within the portion of the bill that funds EPA, wastewater treatment assistance was first specified in an account called Construction Grants, which was subsequently renamed State Revolving Funds/Construction Grants, and then renamed Water Infrastructure. Since FY1996, this account has been titled State and Tribal Assistance Grants (STAG).

The STAG account now includes all water infrastructure funds and management grants provided to assist states in implementing air quality, water quality, and other media-specific environmental programs. The FY1996 appropriation was the first to include both water infrastructure and other state environmental grants; the latter previously were included in EPA's general program management account. Amounts shown in Table 1 include funds for CWA Title II grants, CWSRF grants, drinking water SRF grants, special project grants (discussed below), and the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) program.7 Congress first provided appropriations to cover the subsidy costs of this program in FY2017, as discussed in the detailed chronology section below.

Table 1 does not include funds for consolidated state environmental management grants. These grants include funding for a wide range of environmental programs, which have changed over time. In recent years, the categorical grants have included funding for water, air, and waste programs. The categorical grant programs most closely related to water infrastructure issues include grants for states' nonpoint source management programs (CWA Section 319) and states' pollution control programs (CWA Section 106). Funding levels for the environmental management state grants are discussed below in the appropriations chronology section.

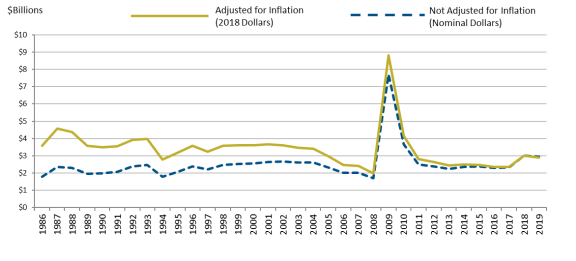

As an additional comparison, Figure 1 illustrates the total EPA water infrastructure appropriations (for clean water and drinking water assistance combined) between FY1986 and FY2019 in both nominal dollars (i.e., not adjusted for inflation) and constant (2018) dollars (i.e., adjusted for inflation).

|

Fiscal Year |

CWA Authorization |

SDWA Authorization |

President's |

CWA Title II |

CWSRF |

DWSRF |

Special Projects |

WIFIA |

Total Appropriation |

|

1986 |

2,400 |

2,400 |

1,800 |

1,800 |

|||||

|

1987 |

2,400 |

2,000 |

2,361 |

2,361 |

|||||

|

1988 |

2,400 |

2,000 |

2,304 |

2,304 |

|||||

|

1989 |

2,400 |

1,500 |

941 |

941 |

68 |

1,950 |

|||

|

1990 |

2,400 |

1,200 |

960 |

967 |

53 |

1,980 |

|||

|

1991 |

2,400 |

1,600 |

2,048 |

36 |

2,084 |

||||

|

1992 |

1,800 |

1,883 |

1,949 |

435 |

2,384 |

||||

|

1993 |

1,200 |

2,467 |

1,928 |

556 |

2,484 |

||||

|

1994 |

600 |

599 |

2,047 |

1,218 |

558 |

1,776 |

|||

|

1995 |

— |

1,000 |

2,528 |

1,235 |

834 |

2,069 |

|||

|

1996 |

— |

1,000 |

2,365 |

2,074 |

307 |

2,380 |

|||

|

1997 |

— |

1,000 |

2,178 |

625 |

1,275 |

301 |

2,201 |

||

|

1998 |

— |

1,000 |

2,078 |

1,350 |

725 |

393 |

2,468 |

||

|

1999 |

— |

1,000 |

2,028 |

1,350 |

775 |

402 |

2,527 |

||

|

2000 |

— |

1,000 |

1,753 |

1,345 |

820 |

395 |

2,561 |

||

|

2001 |

— |

1,000 |

1,753 |

1,350 |

825 |

466 |

2,641 |

||

|

2002 |

— |

1,000 |

2,233 |

1,350 |

850 |

459 |

2,659 |

||

|

2003 |

— |

1,000 |

2,185 |

1,341 |

845 |

413 |

2,599 |

||

|

2004 |

— |

— |

1,798 |

1,342 |

845 |

425 |

2,612 |

||

|

2005 |

— |

— |

1,794 |

1,091 |

843 |

402 |

2,336 |

||

|

2006 |

— |

— |

1,649 |

887 |

838 |

281 |

2,005 |

||

|

2007 |

— |

— |

1,570 |

1,084 |

838 |

84 |

2,005 |

||

|

2008 |

— |

— |

1,553 |

689 |

829 |

177 |

1,695 |

||

|

2009a |

— |

— |

1,397 |

4,689 |

2,829 |

184 |

7,702 |

||

|

2010 |

— |

— |

3,920 |

2,100 |

1,387 |

187 |

3,674 |

||

|

2011 |

— |

— |

3,307 |

1,522 |

963 |

20 |

2,505 |

||

|

2012 |

— |

— |

2,560 |

1,467 |

918 |

15 |

2,399 |

||

|

2013b |

— |

— |

2,045 |

1,376 |

861 |

14 |

2,252 |

||

|

2014 |

— |

— |

1,927 |

1,449 |

907 |

15 |

2,371 |

||

|

2015 |

— |

— |

1,790 |

1,449 |

907 |

15 |

2,371 |

||

|

2016 |

— |

— |

2,317 |

1,394 |

863 |

30 |

2,287 |

||

|

2017 |

— |

— |

2,022 |

1,394 |

963 |

30 |

30 |

2,420 |

|

|

2018c |

— |

— |

2,257 |

1,694 |

1,163 |

30 |

63 |

2,950 |

|

|

2019 |

— |

1,174 |

2,280 |

1,694 |

1,164 |

40 |

68 |

2,966 |

|

|

2020 |

— |

1,300 |

2011(R) |

1,120(R) |

863(R) |

3(R) |

25(R) |

Source: Compiled by CRS from annual appropriations acts. Requested amounts from EPA's FY2020 Budget in Brief.

Notes: (R) = requested

a. The FY2009 total includes $6.0 billion in supplemental appropriations provided under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, P.L. 111-5, consisting of $4.0 billion for CWA SRF capitalization grants and $2.0 billion for SDWA SRF capitalization grants.

b. FY2013 total reflects post-sequester/post-rescission amounts. See text for detail.

c. The FY2018 appropriation provided new funding (in aggregate $50 million) for three SDWA grant programs authorized in the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (P.L. 114-322, Title II, the Water and Waste Act of 2016): $20 million for small and disadvantaged communities for investments needed to achieve SDWA compliance, $20 million for grants for lead testing in school and childcare program drinking water, and $10 million for lead reduction projects. Similarly, FY2019 appropriations included a total of $50 million for these programs. This funding is not included in the table.

|

Figure 1. EPA Water Infrastructure Annual Appropriations: FY1986-FY2019 Adjusted ($2018) and Not Adjusted for Inflation (Nominal) |

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS using information from annual appropriations acts, committee reports, and explanatory statements presented in the Congressional Record. Amounts reflect applicable rescissions and supplemental appropriations, including $6 billion in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). Constant dollars calculated from Office of Management of Budget, Table 10.1, "Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables: 1940-2024," https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals. |

Historical Funding Developments

This section discusses several historical developments of note regarding appropriations for EPA's water infrastructure programs.

Special Purpose Project Grants

The practice of earmarking a portion of the construction grants/SRF account for specific wastewater treatment and other water quality projects began with the FY1989 appropriations. The practice increased to the point of representing a significant portion of appropriated funds (31% of the total water infrastructure appropriation in FY1994, for example, but less in subsequent years: 2.5% in FY2009 and 5% in FY2010). The number of projects receiving these earmarked funds also increased: from 4 in FY1989 to 319 in FY2010. Beginning in FY2000, the larger total number of earmarked projects resulted in more communities receiving such grants, but at the same time receiving smaller amounts of funds. Thus, while a few communities received individual earmarked awards of $1 million or more, the average size of earmarked grants shrank: $18.1 million in FY1995, $4.9 million in FY1999, $1.08 million in FY2006, and $586,000 in FY2010. (Conference reports on the individual appropriations bills, noted in the later discussion in this report, provide some detail on projects funded in this manner.) The effective result of earmarking was to reduce the amount of funds provided to states to capitalize their SRF programs. Between FY1989 and FY2010, approximately 10% of the total water infrastructure appropriations ($7.4 billion) went to earmarked project grants.8

Interest groups representing state water quality program managers and administrators of infrastructure financing programs criticized the practice of earmarked appropriations. They contended that earmarking undermined the intended purpose of the state funds—promoting water quality improvements nationwide. Many state officials preferred funds to be allocated more equitably, not based on what they viewed largely as political considerations, and they preferred for state environmental and financing officials to retain responsibility to set actual spending priorities. Further, they argued that the special projects funding would diminish the level of seed funding to SRFs, delaying the time when SRFs would be financially self-sufficient.

The practice of earmarking was criticized because designated projects were arguably receiving more favorable treatment than other communities' projects: They were generally eligible for 55% federal grants (and were not required to repay 100% of the funded project cost, as is the case with a loan through an SRF), and the practice circumvented the standard process of states determining the priority by which projects will receive funding. It also meant that the projects were generally not reviewed by the CWA authorizing committees. This was especially true after FY1992, when special purpose grant funding was designated for types of projects not authorized in the Clean Water Act or the Safe Drinking Water Act.

Members of Congress intervened for a specific community for a number of reasons. In some cases, the communities may have been unsuccessful in seeking state approval to fund the project under an SRF loan or other program. For some, the cost of a project financed through a state loan was deemed unacceptably high, because repaying the loan would result in increased user fees that ratepayers felt would have been unduly burdensome.

In the early years of this congressional practice, special purpose grant funding originated in the House version of the EPA appropriations bill, while the Senate, for the most part, resisted earmarking by rejecting or reducing amounts and projects included in House-passed legislation. Therefore, special purpose grant funding on several occasions was an issue during the House-Senate conference on the appropriations bill. Beginning in FY1999, however, both the House and Senate proposed earmarked projects in their respective versions of the EPA appropriations bill, with the final total number of projects and dollar amounts determined by conferees.

The Clean Water Act Title II grants program effectively ended when authorizations for it expired after FY1990. One result of earmarking special purpose grants in appropriations bills was to continue grants as a method of funding wastewater treatment construction long after FY1990. This practice led Congress to provide EPA grants for drinking water system projects, which had not previously been available. However, as discussed in the next section, general opposition to congressional earmarking stopped the practice after FY2011.

Local Cost Share on Special Purpose Grants

The federal percentage share and local match required on special purpose grants varied depending on the project and the year of funding. For example, in the early projects (FY1989), the 1987 CWA amendments specified the federal cost shares, which ranged from 75% to 85%. In FY1992 and FY1993, the appropriations acts specified that funds were provided "as grants under title II," resulting in a requirement for local communities to provide a 45% share of project costs. After FY1993, the appropriations acts themselves were the authority for the special purpose projects grants. In the FY1995 appropriation bill, which also directed allocation of funds appropriated in FY1994 to several needy cities, Congress addressed the issue of federal and local cost shares in report language accompanying the bill, but not in the appropriation act itself.9

The conferees are in agreement that the agency should work with the grant recipients on appropriate cost-share arrangements. It is the conferees' expectation that the agency will apply the 45% local cost share requirement under Title II of the Clean Water Act in most cases.

In the FY1996 appropriations, both the act and accompanying reports were silent on federal/local cost share and applicability of Title II requirements. Because of that, EPA officials planned to require only a 5% local match for most of the special purpose grants in that bill, which is the standard matching requirement for other EPA noninfrastructure grants. Under the agency's rules, the local match could include in-kind services, as well as funding toward the project.

In the FY1997 appropriations, Congress included report language as it had in FY1995 concerning federal and local cost share requirements.10

The conferees are in agreement that the Agency should work with the grant recipients on appropriate cost-share agreements and to that end the conferees direct the Agency to develop a standard cost-share consistent with fiscal year 1995.

The FY1998 and FY1999 appropriations included neither bill nor report language on this point. However, language in the House and Senate Appropriations Committees' reports on the FY1998 and FY1999 bills directed EPA to work with grant recipients on appropriate cost-share arrangements.11

For FY2000, Congress included explicit report language concerning the local match.12

The conferees agree that the $331,650,000 provided to communities or other entities for construction of water and wastewater treatment facilities and for groundwater protection infrastructure shall be accompanied by a cost-share requirement whereby 45 percent of a project's cost is to be the responsibility of the community or entity consistent with long-standing guidelines for the Agency. These guidelines also offer flexibility in the application of the cost-share requirement for those few circumstances when meeting the 45 percent requirement is not possible.

Similar report language concerning local cost-share requirements accompanied the conference reports on the appropriations bills from FY2001 through FY2005. Beginning with FY2004, Congress specified in the appropriations legislation that the local share of project costs shall be not less than 45%. Similarly, beginning with the FY2003 appropriations legislation, Congress also specified that, except for those limited instances in which an applicant meets the criteria for a waiver of the cost-share requirement, the earmarked grant shall provide no more than 55% of an individual project's cost, regardless of the amount appropriated.

The practice of earmarking special project water infrastructure grants continued to change. First, in FY2007, Congress applied a one-year moratorium on earmarks in all appropriations bills. For the next three years, special project grants were allowed in appropriations bills—including EPA's—but again in FY2011, no special project funding was provided for congressional projects. Following the 2010 midterm election and during subsequent months while FY2011 appropriations were under consideration (discussed below), the general issue of congressional earmarks of specific projects had become highly controversial because of the overall growing number of them, concern over the influence of special interests on spending decisions, and lack of congressional oversight. In response, President Obama said he would veto any legislation containing earmarks, the House extended the ban on earmarks under the Republican Conferences rules, and the chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee announced a moratorium on earmarks for FY2011 and FY2012. Thus, the FY2011 full-year appropriations measure contained no congressionally directed special project funds for water infrastructure projects in the EPA STAG account. However, it did include funds requested by the President: $10 million for Alaska Native Villages and $10 million for U.S.-Mexico border projects.13

The FY2012 full-year appropriations measure also contained no special project funding in the EPA STAG account. The FY2012 bill did include funds for Alaska Native and Rural Villages ($10 million) and for U.S.-Mexico border projects ($5 million).

The moratorium on congressional earmarks has continued. The FY2013 full-year appropriations measure (P.L. 113-6) contained no special project funding in the STAG account. As with other recent bills, however, it did include funds for Alaska Native and Rural Villages ($9.5 million) and for U.S.-Mexico border projects ($4.7 million). Similarly, the moratorium on earmarks continued in FY2014 and FY2015; P.L. 113-76 contained no special project funding in the STAG account for FY2014, but did include funds for Alaska Native and Rural Villages ($10 million) and for U.S.-Mexico border projects ($5 million). The FY2015 funding bill, P.L. 113-235, was the same as FY2014. The FY2016, FY2017, and FY2018 appropriations acts (P.L. 114-113, P.L. 115-31, and P.L. 115-141, respectively) included $20 million for Alaska Native and Rural Villages and $10 million for U.S.-Mexico border projects. The FY2019 appropriations act provided $25 million for Alaska Native and Rural Villages and $15 million for U.S.-Mexico border projects. President Trump's FY2020 budget request proposes to eliminate funding for the U.S.-Mexico border program and decrease funding for the Alaska Native and Rural Villages to $3 million.

Additional Subsidization

Although the CWSRF and DWSRF have largely functioned as loan programs, both allow the implementing state agency to provide "additional subsidization" under certain conditions. Since its amendments in 1996, the SDWA has authorized states to use up to 30% of their DWSRF capitalization grants to provide additional assistance, such as forgiveness of loan principal or negative interest rate loans, to help disadvantaged communities (as determined by the state).14 In 2018, AWIA increased that percentage to 35% and conditionally required states to provide at least 6% of their annual grants as additional subsidization.

Congress amended the CWA in 2014, adding similar provisions to the CWSRF program.15

In addition, appropriations acts in recent years have required states to use minimum percentages of their allotted funds to provide additional subsidization. This trend began with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5), which required states to use at least 50% of their funds to "provide additional subsidization to eligible recipients in the form of forgiveness of principal, negative interest loans or grants or any combination of these." Subsequent appropriation acts have included similar conditions, with varying percentages of subsidization. The FY2016, FY2017, FY2018, and FY2019 appropriations acts included an identical condition, requiring 10% of the CWSRF grants and 20% of the DWSRF grants to be used "to provide additional subsidy to eligible recipients in the form of forgiveness of principal, negative interest loans, or grants (or any combination of these)."

Noninfrastructure Grants

The 1987 CWA amendments authorized federal grants to assist states in implementing programs to manage water pollution from nonpoint sources such as farm and urban areas, construction, forestry, and mining sites. Because of competing demands for funding, it was difficult for Congress to fund this grant program and other water quality initiatives in the 1987 act. Appropriators did fund Section 319 grants in EPA's general program management account (abatement, control, and compliance) in FY1990, FY1991, and FY1992 but well below authorized levels. In the FY1993 act, appropriators moved funding into the SRF/construction grants account, thereby providing a degree of protection from competing priorities. In FY1996, Congress included all state grants for management of environmental programs in a single consolidated grants appropriation. In doing so, Congress endorsed a Clinton Administration proposal for a more flexible approach to state grants, a key element of EPA's efforts to improve the federal-state partnership in environmental programs. In more recent years, Congress has provided specific funding amounts for certain programs within the categorical grants appropriation.

Appropriations Chronology

This section summarizes, in chronological order, congressional activity to fund items in the STAG account since the 1987 CWA amendments.

FY1986, FY1987

The authorization period covered by P.L. 100-4 was FY1986-FY1994. By the time the amendments were enacted, FY1986 was over, as was a portion of FY1987. Thus, appropriations for those two years only indirectly reflected the policy and program changes for later years that were contained in P.L. 100-4. For FY1986, Congress appropriated a total of $1.8 billion, consisting of $600 million approved in December 1985 (while Congress was beginning to debate reauthorization legislation that eventually was enacted as P.L. 100-4 in January 1987) and $1.2 billion more in July 1986.

For FY1987, while debate on CWA reauthorization continued, President Reagan requested $2.0 billion, consistent with his legislative proposal to terminate the grants program by FY1990. In October 1986, Congress appropriated $2.4 billion (P.L. 99-500/P.L. 99-591). However, only $1.2 billion of that amount was released immediately, pending enactment of a reauthorization bill, which was then in conference. Following enactment of the Water Quality Act of 1987, remaining FY1987 funds were released as part of a supplemental appropriations bill (P.L. 100-71). Conferees on that measure agreed, however, to shift $39 million of the remaining unreleased grant funds to other priority water quality activities authorized in P.L. 100-4. The final total of construction grant monies was $2.361 billion.

FY1988

For FY1988 the President again requested $2.0 billion. In December 1987, Congress approved legislation providing FY1988 appropriations (P.L. 100-202, the omnibus continuing resolution to fund EPA and other federal agencies). In it, Congress appropriated $2.304 billion for construction grants. Final action on the EPA budget and other funding bills had been delayed by budget-cutting talks between Congress and the White House. Reduced construction grants funding was one of many spending cuts required to implement a congressional-White House "summit agreement" on the budget. The final construction grants appropriation was less than funding levels that had been included in separate versions of a bill passed by the House and Senate before the budget summit, $2.4 billion.

FY1989

For FY1989, President Reagan requested $1.5 billion, or 35% below FY1988 appropriations and 37.5% less than the authorized level of $2.4 billion for FY1989. In separate versions of an EPA appropriations bill, the House and Senate voted to provide $1.95 billion and $2.1 billion respectively. The final figure, in P.L. 100-404, was $1.95 billion, which included $68 million for special projects in four states. Thus, the actual amount provided for grants was $1.882 billion. That total was divided equally between the previous Title II grants program and new Title VI SRF program, as provided in the authorizing language of P.L. 100-4.

The FY1989 legislation was the first to include earmarking of funds for specified projects or grants in EPA's construction grants account, an action that continued in subsequent years, as discussed above. All of the projects funded in the 1989 legislation were ones that had been authorized in provisions of the Water Quality Act of 1987 (WQA, P.L. 100-4). The designated projects were in Boston (authorized in Section 513 of the WQA, to fund the Boston Harbor wastewater treatment project), San Diego/Tijuana (Section 510, to fund an international sewage treatment project needed because of the flow of raw sewage from Tijuana, Mexico, across the border), Des Moines, IA (Section 515, for sewage treatment plant construction), and Oakwood Beach/Redhook, NY (Section 512 of the WQA, to relocate natural gas distribution facilities that were near wastewater treatment works in New York City).

FY1990

For FY1990, President Reagan's budget requested $1.2 billion in wastewater treatment assistance, or 50% less than the authorized level and 38.5% less than the FY1989 enacted amount of $1.95 billion. Further, the Reagan budget proposed that the $1.2 billion consist of $800 million in Title VI monies and $400 million in Title II grants, contrary to provisions of the CWA directing that appropriations be equally divided between the two grant programs, as in FY1989. President Bush's revised FY1990 budget, presented in March 1989, made no changes from the Reagan budget in this area.

In acting on this request, Congress agreed to provide $2.05 billion, including $46 million for three special projects (Boston, San Diego/Tijuana, and Des Moines), leaving a total of $1.002 billion each for Titles II and VI (P.L. 101-144). Title II funds were reduced by $6.8 million, however, due to funds earmarked for a specific project in South Carolina. Although these amounts were appropriated, all funds in the bill were reduced by 1.55% (or, a $31.8 million reduction from the construction grants account) to provide funds for the federal government's antidrug program.

Final FY1990 appropriations were altered again by passage of the FY1990 Budget Reconciliation measure and implementation of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act (the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act), which established procedures to reduce budget deficits annually, resulting in a zero deficit by 1993. For each fiscal year that the deficit was estimated to exceed maximum targets established in law, an automatic spending reduction procedure was triggered to eliminate deficits in excess of the targets through "sequestration," or permanent cancellation of budgetary resources.

Thus, to meet budget reduction mandates and, in particular, deficit reduction targets under the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act (the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act), additional funding cuts were included in P.L. 101-239, the Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989, affecting construction grants funding and all other accounts not exempted from Gramm-Rudman procedures. P.L. 101-239 provided that the "sequestration" procedures under the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act would be allowed to apply for a portion of FY1990 (for 130 days, or 35.6% of the year), providing an additional automatic spending reduction in EPA and other agencies' programs subject to the act.

As a result of these reductions, funding for wastewater treatment aid in FY1990 totaled $1.98 billion, or $30 million more than in FY1989. The total included $53 million for special projects in San Diego, Boston, Des Moines, and Honea Path/Ware Shoals, SC, $960 million for Title II grants, and $967 million for Title VI grants. The combined reductions amounted to 3.4% less than the amount agreed to by conferees on P.L. 101-144 (i.e., $2.05 billion), before subtracting funds for antidrug programs and accounting for effects of the Gramm-Rudman partial-year sequester.

FY1991

For FY1991, President Bush requested $1.6 billion in funding for wastewater treatment assistance. This total included $15.4 million for the San Diego project authorized in Section 510 of the Water Quality Act of 1987, to fund construction of an international sewage treatment project. The remainder, $1.584 billion, would be only for capitalization grants under Title VI of the act, as the 1987 legislation provides for no new Title II grants after FY1990.

In acting on EPA's appropriations for FY1991 (P.L. 101-507), Congress agreed to provide $2.1 billion in wastewater treatment assistance. Beginning in FY1991, all appropriated funds are utilized for capitalization grants under Title VI of the act (as provided in the Water Quality Act of 1987); funding for the traditional Title II grants program was no longer available.

The enacted level included several earmarkings: $15.7 million for San Diego (Section 510 of the WQA), $20 million for Boston Harbor (Section 513 of the WQA), and $16.5 million for a new Water Quality Cooperative Agreement Program under Section 104(b)(3) of the act.16 The President's budget had requested $16.5 million to support state permitting, enforcement, and water quality management activities, especially to offset the reductions in aid to states due to elimination of state management setasides from the previous Title II construction grants program. Congress agreed to the level requested, but provided it as a portion of the wastewater treatment appropriation, rather than as part of EPA's general program management appropriation, as in the President's request. As a result of these earmarkings, $2.048 billion was provided for Title VI grants.

FY1992

For FY1992, President Bush requested $1.9 billion in wastewater treatment funds, or $100 million more than authorized under the Water Quality Act of 1987 for Title VI grants in FY1992. However, out of the $1.9 billion total, the President's request sought $1.5 billion for Title VI SRF grants and $400 million as grants under the expired Title II construction grants program for the following coastal cities: Boston, San Diego, New York, Los Angeles, and Seattle. Two of the five designated projects had been authorized in the 1987 CWA amendments; the other three did not have explicit statutory authorization. Also, $16.5 million was requested for Water Quality Cooperative Agreement grants to the states.

In acting on the request in November 1991, Congress provided total wastewater funds of $2.4 billion (P.L. 102-139). The total was allocated as follows:

- $1,948.5 million for SRF capitalization grants,

- $16.5 million for Section 104(b)(3) grants,

- $49 million for the special project in San Diego-Tijuana (Section 510 of the Water Quality Act),

- $46 million to the Rouge River (MI) National Wet Weather Demonstration Project, and

- $340 million as construction grants under title II of the Clean Water Act for several other special projects—the Back River Wastewater Treatment Plant (Baltimore), Maryland, the Boston Harbor project, New York City, Los Angeles, San Diego (a wastewater reclamation project), and Seattle.

This appropriation bill was the first to include special purpose grant funding for several projects not specifically authorized in the Clean Water Act or amendments to that law.

FY1993

For FY1993, President Bush requested $2.484 billion for state revolving funds/construction grants (now called the water infrastructure account). The requested total included $340 million to be targeted for 55% construction grants to six communities: Boston, New York, Los Angeles, San Diego, Seattle, and Baltimore. In addition, the President requested that $130 million be directed toward a Mexican Border Initiative, consisting of $65 million for construction of the international treatment plant at San Diego (to address the Tijuana sewage problem), $15 million for projects at Nogales, AZ, and New River, CA, and $50 million as 50% grants for colonias in Texas.17 The President also requested $16.5 million for Section 104(b)(3) grants. Along with these special project and grant amounts, the request sought $2.014 billion for SRF assistance.

Final action on FY1993 funding occurred on September 25, 1992 (P.L. 102-389). It provided an appropriation of $2.55 billion, but $622.5 million of this amount was reserved for special projects and other grants. The bill provided $50 million in CWA Section 319 grants and $16.5 million in Section 104(b)(3) grants out of the SRF amount. It included $556 million for the following special purpose grants: the international treatment plant at San Diego (Tijuana—Section 510 of the WQA, with bill language capping funding for that project at $239.4 million), plus projects in Boston; New York; Los Angeles; San Diego; Seattle; Rouge River, MI; Baltimore; Ocean County, NJ; Atlanta; and for colonias in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. The final SRF grant amount under the bill was $1.928 billion.

Early in 1993, President Clinton requested that Congress approve "economic stimulus and investment" spending, in the form of supplemental FY1993 appropriations. Both his original proposal and a subsequent modified proposal included additional SRF grant funds, but neither of the bills enacted by Congress in response to these requests (P.L. 103-24, P.L. 103-50) provided additional SRF funds.

FY1994

For FY1994, the Clinton Administration requested $2.047 billion for water infrastructure. The funds in this request were $1.198 billion to capitalize State Revolving Funds, $150 million for Mexican border project grants, and $100 million for a single hardship community (Boston). The request also included $599 million to capitalize new state drinking water revolving funds.

The final version of the FY1994 legislation (P.L. 103-124) provided $2.477 billion for water infrastructure/state revolving funds. Of this total amount, $599 million was to be reserved for drinking water SRFs, if authorization legislation were enacted; $80 million was for Section 319 grants; $22 million was for Section 104(b)(3) grants; and $58 million was for Tijuana/San Diego—Section 510 of the WQA. This resulted in an appropriation of $1.718 billion for clean water SRFs.

In addition, the final bill provided that $500 million be used to support water infrastructure financing in economically distressed/hardship communities. Under the bill, these funds were not available for spending until May 31, 1994, and were set aside until projects were authorized in the CWA for this purpose.

Thus, the bill as enacted provided $1.218 billion immediately for clean water SRFs, with the expectation that $500 million more would be available for financing hardship community projects after May 31, 1994.

FY1995

For FY1995, President Clinton requested $2.65 billion for water infrastructure consisting of $1.6 billion for CWA SRFs, $100 million for Section 319 nonpoint source management grants to states, $52.5 million for a grant to San Diego for a wastewater project pursuant to Section 510 of the WQA, $47.5 million for other Mexican border projects, $50 million to the state of Texas for colonias projects, and $100 million for grants under Title II for needy cities (intended for Boston). The request included $700 million for drinking water SRFs, pending enactment of authorizing legislation. The President's budget also requested $21.5 million for Section 104(b)(3) grants/cooperative agreements.

Final agreement on FY1995 funding was contained in P.L. 103-327, enacted in September 1994, which provided a total of $2.962 billion for water infrastructure financing. Of the total, $22.5 million was for grants under Section 104(b), $100 million for Section 319 grants, $70 million for Public Water System Supervision program grants (grants to states under the Safe Drinking Water Act to support state implementation of delegated drinking water programs), $52.5 million for the Section 510 project in San Diego, and $700 million for drinking water SRFs (contingent upon enactment of authorization legislation).

The remaining $2.017 billion was for CWA projects. Of this amount, $1.235 billion was for clean water SRF grants to states under Title VI of the CWA. The remaining $781.8 million (39% of this amount, 26% of the total appropriation) was designated for 45 specific, named projects in 22 states. The earmarked amounts ranged in size from $200,000 for Southern Fulton County, PA, to $100 million for the city of Boston.

Finally, the conferees included bill language concerning release of the $500 million in FY1994 needy cities money (because the authorizing committees of Congress had not acted on legislation to authorize specific projects, as had been intended in P.L. 103-124) as follows:

- $150 million to Boston, $50 million for colonias in Texas, $10 million for colonias in New Mexico, $70 million for a New York City wastewater reclamation facility, $85 million for the Rouge River project, $50 million for the city of Los Angeles, $50 million for the county of Los Angeles, and $35 million for Seattle, WA.

FY1996

In February 1995, President Clinton submitted the Administration's budget request for FY1996. It requested $2.365 billion for water infrastructure funding consisting of $1.6 billion for clean water state revolving funds, $500 million for drinking water state revolving funds, $150 million to support Mexico border projects under the U.S.-Mexican Border Environmental Initiative and NAFTA, and $100 million for special need/economically distressed communities (not specified in the request, but presumed to be intended for Boston), plus $15 million for water infrastructure needs in Alaska Native Villages.

In February 1995, congressional appropriations committees began considering legislation to rescind previously appropriated FY1995 funds, as part of overall efforts by the 104th Congress to shape the budget and federal spending. These efforts resulted in passage in July 1995 of P.L. 104-19, which rescinded $16.5 billion in total funds from a number of departments, agencies, and programs. In the water infrastructure area, it rescinded $1,077,200,000 from prior year appropriations including the $3.2 million for a project in New Jersey (it had mistakenly been funded twice in P.L. 103-327) and $1,074,000,000 in other water infrastructure appropriations. Although not contained in bill language, it was understood that the larger rescinded amount consisted solely of drinking water SRF funds (leaving $1.235 billion for FY1995 clean water SRF funds, $778.6 million for earmarked wastewater projects—both amounts as originally appropriated—and $225 million in FY1994-FY1995 drinking water SRF funds that had not yet been authorized).

It took until April 1996 for Congress and the Administration to reach agreement on FY1996 appropriations for EPA as part of omnibus legislation (P.L. 104-134) that consolidated five appropriations bills not yet enacted due to disagreements over funding levels and policy. Agreement came as the fiscal year was more than one-half over.

Before that, however, congressional conferees reached agreement in November 1995 on FY1996 legislation for EPA (H.R. 2099, H.Rept. 104-353). Conferees agreed to provide $2.323 billion for a new account titled State and Tribal Assistance Grants (STAG), consisting of infrastructure assistance and state environmental management grants for 16 categorical programs that had previously been funded in a separate appropriations account. The total included $1.125 billion for clean water SRF grants, $275 million in new appropriations for drinking water SRF grants, and $265 million for special purpose project grants. Report language provided that the drinking water SRF money also included $225 million from FY1995 appropriations rescinded in P.L. 104-19. The drinking water SRF money would be available upon enactment of SDWA reauthorization legislation that would authorize a drinking water SRF program; otherwise, it would revert to clean water SRF grants if the SDWA were not reauthorized by June 30, 1996. This made the total potentially available for drinking water SRF grants $500 million.

The November 1995 agreement on H.R. 2099 included $658 million for consolidated state environmental grants. In doing so, Congress endorsed an Administration proposal for a more flexible approach to state grants, a key element of EPA's efforts to improve the federal-state partnership in environmental programs. In lieu of traditional grants provided separately to support state air, water, hazardous waste, and other programs, consolidated grants are intended to reduce administrative burdens and improve environmental performance by allowing states and tribes to target funds to meet their specific needs and integrate their environmental programs, as appropriate. Congress's support was described in accompanying report language.18

The conferees agree that Performance Partnership Grants are an important step to reducing the burden and increasing the flexibility that state and tribal governments need to manage and implement their environmental protection programs. This is an opportunity to use limited resources in the most effective manner, yet at the same time, produce the results-oriented environmental performance necessary to address the most pressing concerns while still achieving a clean environment.

Including state environmental grants in the same account with water infrastructure assistance reflected Congress's support for enhancing the ability of states and localities to implement environmental programs flexibly and support for EPA's ability to provide block grants to states and Indian tribes.

The H.R. 2099 conference agreement also included legislative riders intended to limit or prohibit EPA from spending money to implement several environmental programs. The Administration opposed the riders. The House and Senate approved this bill in December, but President Clinton vetoed it, because of objections to spending and policy aspects of the legislation.

With no full-year funding in place from October 1995 to April 1996, EPA and the programs it administers (along with agencies and departments covered by four other appropriations bills not yet enacted) were subject to a series of short-term continuing resolutions, some lasting only a day, some lasting several weeks. In March 1996, the House and Senate began consideration of an omnibus appropriations bill to fund EPA and other agencies for the remainder of FY1996, finally reaching agreement in April on a bill (H.R. 3019) enacted as P.L. 104-134.19 Congress agreed to provide $2.813 billion for a new account titled STAG, consisting of state grants and infrastructure assistance, as in H.R. 2099, the vetoed measure. The total was divided as follows:

- $1.3485 billion for clean water SRF grants (including $50 million for impoverished communities),

- $500 million in new appropriations for drinking water SRF grants,

- $150 million for Mexico-border project grants and Texas colonias, as requested,

- $15 million for Alaska Native Villages, as requested,

- $141.5 million for 17 special purpose project grants, and

- $658 million for consolidated state environmental grants, which states could use to administer a range of delegated environmental programs.

Report language provided that the drinking water SRF money also included $225 million from FY1995 appropriations that remained available after the rescissions in P.L. 104-19, for a total of $725 million. The drinking water SRF money was contingent upon enactment of legislation authorizing an SRF program under the Safe Drinking Water Act by August 1, 1996; otherwise, it would revert to clean water SRF grants.

The final agreement (P.L. 104-134) included several of the legislative riders from previous versions of the legislation, including riders related to drinking water and clean air, but dropped others strongly opposed by the Administration.

Funds within the STAG account were redistributed after Congress passed Safe Drinking Water Act amendments in August 1996. Enactment of the amendments (P.L. 104-182) occurred on August 6—after the August 1 deadline in P.L. 104-134 that would have made $725 million available for drinking water SRF grants in FY1996. Thus, the previously appropriated $725 million reverted to clean water SRF grants, making the FY1996 total for those grants $2.0735 billion.

FY1997

While debate over the FY1996 appropriations was continuing, in March 1996, President Clinton submitted the details of a FY1997 budget. For water infrastructure and state and tribal assistance, the request totaled $2.852 billion consisting of

- $1.35 billion for clean water SRF grants (the request included language that would authorize states the discretion to use this SRF money either for clean water or drinking water projects),

- $165 million for U.S.-Mexico border projects, Texas colonias, and Alaska Native Village projects,

- $113 million for needy cities projects,

- $550 million for drinking water infrastructure SRF funding, contingent upon enactment of authorizing legislation, and

- $674 million for state performance partnership consolidated management grants, which could address a range of environmental programs.

In response to the Administration's request, in June 1996 the House approved legislation (H.R. 3666) providing FY1997 funding for EPA. In the STAG account, the House approved $2.768 billion, $84 million less than requested but on the whole endorsing the budget request. The total provided the following: $1.35 billion for clean water SRF grants, as requested; $165 million, as requested, for U.S.-Mexico Border projects, Texas colonias, and Alaska Native Village projects; $450 million for drinking water SRF funding, contingent upon authorization; $674 million for state performance partnership consolidated management grants; and $129 million for seven special purpose grants.

In July, the Senate Appropriations Committee reported its version of H.R. 3666. The committee approved $2.815 billion for this account, consisting of $1.426 billion for clean water SRF grants; $550 million for drinking water SRF grants, contingent upon authorization; $165 million, as requested, for U.S.-Mexico border projects, Texas colonias, and Alaska Native Village projects; and $674 million for consolidated state grants. The committee rejected the provision of the House-passed bill providing $129 million for special purpose grants, including funds for Boston and New Orleans requested by the Administration, saying in report language that earmarking is provided at the expense of state revolving funds and does not represent an equitable distribution of grant funds (S.Rept. 104-318).

During debate on H.R. 3666 in September, the Senate adopted an amendment to reduce the FY1997 appropriation for clean water SRF grants by $725 million in order to fund the new drinking water SRF program. This action was intended to restore funds to the drinking water program which had been lost when Safe Drinking Water Act amendments were not enacted by August 1, 1996. Thus, the Senate-passed bill provided $701 million for clean water SRF grants and $1.275 billion for drinking water SRF grants for FY1997. Other amounts in the account were unchanged.

The conference report on H.R. 3666 (H.Rept. 104-812) was approved by the House and Senate on September 24, 1996. President Clinton signed the bill September 26 (P.L. 104-204). It reflected compromise of the House- and Senate-passed bills, providing the following amounts within the STAG account ($2.875 billion total):

- $625 million for clean water SRF grants,

- $1.275 billion for drinking water SRF grants,

- $165 million, as requested, for U.S.-Mexico border projects, Texas colonias, and Alaska Native Village projects,

- $136 million for 18 specific wastewater, water, and groundwater project grants (the 7 specified in House-passed H.R. 3666, plus 11 more; the bill provided funds for each of the needy cities projects requested by the Administration, but in lesser amounts), and

- $674 million for consolidated state grants, which could support implementation of a range of environmental programs.

The allocation of clean water and drinking water SRF grants was consistent with the Senate's action to restore funds to the drinking water program after enactment of the Safe Drinking Water Act amendments in early August.20

Subsequently, Congress passed a FY1997 Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations bill to cover agencies and departments for which full-year funding had not been enacted by October 1, 1996 (P.L. 104-208). It included additional funding for several EPA programs, as well as $35 million (on top of $40 million provided in P.L. 104-204) for the Boston Harbor cleanup project.

FY1998

President Clinton presented the Administration's budget request for FY1998 in February 1997. For water infrastructure and state and tribal assistance, the request totaled $2.793 billion, consisting of $1.075 billion for clean water SRF grants, $725 million for drinking water SRF grants, $715 million for consolidated state environmental grants, and $278 million for special project grants.

House and Senate committees began activities on FY1998 funding bills somewhat late in 1997, due to prolonged negotiations between Congress and the President over a five-year budget plan to achieve a balanced budget by 2002. After appropriators took up the FY1998 funding bills in June, the House passed EPA's appropriation in H.R. 2158 (H.Rept. 105-175) on July 15. In the STAG account, the House approved $3.019 billion, consisting of $1.25 billion for clean water SRF grants ($600 million more than FY1997 levels and $175 million more than requested by the President), $750 million for drinking water SRF grants ($425 million less than FY1997 levels, but $25 million more than the request), $750 million for state environmental assistance grants, and $269 million for special projects. The latter included funds for the special projects requested by the Administration but at reduced levels ($149 million total for these projects), plus $120 million in special project grants for 21 other communities.

The Senate passed a separate version of an FY1998 appropriations bill on July 22, 1997 (S. 1034, S.Rept. 105-53). It provided $3.047 billion for the STAG account, consisting of $1.35 billion for clean water SRF grants, $725 million for drinking water SRF grants, $725 million for state environmental assistance grants, and $247 million for special project grants. The Senate bill provided the amounts requested by the Administration for U.S.-Mexico border projects, Texas colonias, and Alaska Native Village projects (but no special funds for others requested by the President), plus $82 million for 18 special project grants for other communities identified in report language.

Conferees reached agreement on FY1998 funding in early October 1997 (H.R. 2158, H.Rept. 105-297). The final version passed the House on October 8 and passed the Senate on October 9. President Clinton signed the bill October 27 (P.L. 105-65). As enacted, it provided $3.213 billion for the STAG account, consisting of $1.35 billion for clean water SRF grants, $725 million for drinking water SRF grants, $745 million for consolidated state environmental assistance grants (which could address a range of environmental programs), and $393 million for 42 special purpose project and special community need grants for construction of wastewater, water treatment and drinking water facilities, and groundwater protection infrastructure. It included the following amounts for grants requested by the Administration:

- $75 million for U.S.-Mexico border projects,

- $50 million for Texas colonias,

- $50 million for Boston Harbor wastewater needs,

- $10 million for New Orleans,

- $3 million for Bristol County, MA, and

- $15 million for Alaska Native Village projects.

The final bill also provided funds for all of the special purpose projects included in the separate House and Senate versions of the legislation, plus three projects not included in either earlier version.

Bill language was included in P.L. 105-65 to allow states to cross-collateralize clean water and drinking water SRF funds, that is, to use the combined assets of amounts appropriated to State Revolving Funds as common security for both SRFs, which conferees said is intended to ensure maximum opportunity for states to leverage these funds. Senate committee report language also said that the conference report on the 1996 Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments had stated that bond pooling and similar arrangements were not precluded under that legislation. The appropriations bill language was intended to ensure that EPA does not take an unduly narrow interpretation of this point which would restrict the states' use of SRF funds.21

On November 1, 1997, President Clinton used his authority under the Line Item Veto Act (P.L. 104-130) to cancel six items of discretionary budget authority provided in P.L. 105-65. The President's authority under this act took effect in the 105th Congress; thus, this was the first EPA appropriations bill affected by it. The cancelled items included funding for one of the special purpose grants in the bill, $500,000 for new water and sewer lines in an industrial park in McConnellsburg, PA. Reasons for the cancellation, according to the President, were that the project had not been requested by the Administration; it would primarily benefit a private entity and is outside the scope of EPA's usual mission; it is a low priority use of environmental funds; and it would provide funding outside the normal process of allocating funds according to state environmental priorities.22

However, in June 1998, the Supreme Court struck down the Line Item Veto Act as unconstitutional, and in July the Office of Management and Budget announced that funding would be released for 40-plus cancellations made in 1997 under that act (including those cancelled in P.L. 105-65) that Congress had not previously overturned. (For additional information, see CRS Report RL33635, Item Veto and Expanded Impoundment Proposals: History and Current Status, by Virginia A. McMurtry.)

FY1999

President Clinton's budget request for FY1999, presented to Congress in February 1998, requested $2.9 billion for the STAG account, representing 37% of the $7.9 billion total requested for EPA programs. The total included $1.075 billion for clean water SRF grants, $775 million for drinking water SRF grants, $115 million for water infrastructure projects along the U.S.-Mexico border projects and in Alaska Native Villages, $78 million for needy cities projects, and $875 million for consolidated state environmental grants (which could address a range of environmental programs).

Legislative action on the budget request occurred in mid-1998. Both houses of Congress increased amounts for water infrastructure financing, finding the Administration's request for clean water and drinking water SRF grants, as well as special project funding, not adequate. First, the Senate Appropriations Committee reported its version of an EPA spending bill in June 1998 (S. 2168, S.Rept. 105-216). This bill, passed by the Senate July 17, provided $3.2 billion for the STAG account, consisting of $1.4 billion for clean water SRF grants, $800 million for drinking water SRF grants, $105 million for U.S.-Mexico and Alaska Native Village projects, $100 million for 39 other special needs infrastructure grants, and $850 million for state performance partnership/categorical grants. As in FY1998, the committee included bill language allowing states to cross-collateralize their clean water and drinking water state revolving funds, making the language explicit for FY1999 and thereafter.

Second, the House passed its version of EPA's funding bill (H.R. 4194, H.Rept. 105-610) on July 29. This bill provided $3.2 billion for the STAG account, consisting of $1.25 billion for clean water SRF grants, $775 million for drinking water SRF grants, $70 million for U.S.-Mexico and Alaska Native Village projects, $253.5 million for 49 other special needs infrastructure grants (including nine projects also funded in the Senate bill), and $885 million for state environmental management grants (a 20% increase above FY1998 amounts for these state grants).

Conferees resolved differences between the two versions in October 1998 (H.R. 4194, H.Rept. 105-769). The conference agreement provided $3.4 billion for the STAG account, consisting of $1.35 billion for clean water SRF grants, $775 million for drinking water SRF grants, $80 million for U.S.-Mexico and Alaska Native and Rural Village projects, $301.8 million for 80 other special needs project grants, and $880 million for state and tribal environmental program grants (which could address a range of environmental programs). The House and Senate approved the agreement on October 7 and 8, respectively, and President Clinton signed the bill into law on October 21 (P.L. 105-276).

Additional funding was provided in the Omnibus Consolidated and Supplemental Appropriations Act, FY1999 (P.L. 105-277). This bill, which provided full-year funding for agencies and departments covered by seven separate appropriations measures, directed $20 million more in special needs grants for the Boston Harbor wastewater infrastructure project, on top of $30 million that was included in P.L. 105-276.

FY2000

For FY2000, beginning on October 1, 1999, the Administration requested $2.638 billion for water infrastructure assistance and state environmental grants. The total, $370 million less than the FY1999 appropriation for this account, consisted of $800 million for clean water SRF grants, $825 million for drinking water SRF grants, $128 million for Mexican border and special project grants, and $885 million for consolidated state environmental grants (which could address a range of environmental programs).

The request included one SRF policy issue. The Administration asked the appropriators to grant states the permission to set aside up to 20% of FY2000 clean water SRF monies in the form of grants for local communities to implement nonpoint source pollution and estuary management projects. Under the Clean Water Act, SRFs may only be used to provide loans. Some have argued that some types of water pollution projects which are eligible for SRF funding may not be suitable for loans, as they may not generate revenues which can be used to repay the loan to a state. This new authority, the Administration said, would allow states greater flexibility to address nonpoint pollution problems. Critics of the proposal said that making grants from an SRF would reduce the long-term integrity of a state's fund, since grants would not be repaid.

Some Members of Congress and stakeholder groups were particularly critical of the budget request for clean water SRF grants, $550 million (40%) less than the FY1999 level. Critics said the request was insufficient to meet the needs of states and localities for clean water infrastructure. In response, EPA acknowledged that several years prior the Clinton Administration had made a commitment to states that the clean water SRF would revolve at $2 billion annually in the year 2005. Because of loan repayments and other factors, EPA said, the overall fund will be revolve at $2 billion per year in the year 2002, even with the 20% grant setaside included in the FY2000 request. According to EPA, the $550 million decrease from 1999 would have only a limited impact on SRFs and would still allow the agency to meet its long-term capitalization goal of providing an average amount of $2 billion in annual assistance.

The House and Senate passed their respective versions of an EPA appropriations bill (H.R. 2684) in September 1999. The conference committee report resolving differences between the two versions (H.Rept. 106-379) was passed by the House on October 14 and the Senate on October 15 and was signed by the President on October 20 (P.L. 106-74). The final bill provided $7.6 billion overall for EPA programs, including $3.47 billion for the STAG account. Within that account, the bill included $1.35 billion for clean water SRF grants, $820 million for drinking water SRF grants, $885 million for categorical state grants (which generally support state and tribal implementation and could address a range of environmental programs), $80 million for U.S.-Mexico border and Alaska Rural and Native Village projects, and $331.6 million for 141 other special needs water and wastewater grants specified in report language. The final bill did not approve the Administration's request to allow states to use up to 20% of clean water SRF monies as grants for nonpoint pollution and estuary management projects.

Subsequent to enactment of the EPA funding bill, Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2000 with funding for five other agencies (P.L. 106-113), which included provisions requiring a government-wide cut of 0.38% in discretionary appropriations. The bill gave the President some flexibility in applying this across-the-board reduction. Details of the reduction were announced at the time of the release of the FY2001 budget. EPA's distribution of the rescission resulted in a total reduction of $16.3 million for 139 of the special needs water and wastewater projects identified in P.L. 106-74. These projects were reduced 4.9% below enacted levels. The agency did not reduce funds for the two projects that had been included in the President's FY2000 budget request (Bristol County, MA, and New Orleans, LA) or for the United States-Mexico border and the Alaska Rural and Native Villages programs. EPA also reduced funds for the clean water SRF (enacted at $1.35 billion) by 0.3%, for a final funding level of $1.345 billion. The appropriation level was not reduced for the drinking water SRF or consolidated state grants.

FY2001

The President's budget for FY2001 requested a total of $2.9 billion for water infrastructure assistance and state environmental grants. For the second year in a row, President Clinton requested $800 million for the clean water SRF program, a $545 million reduction from the FY2000 level. The request included $825 million for the drinking water SRF program, $100 million for U.S.-Mexico border project grants, $15 million for Alaska Native Villages projects, two needy cities grants totaling $13 million (Bristol County, MA, and New Orleans, LA), plus $1.069 billion for consolidated state environmental grants (which could address a range of environmental programs).