East Asia’s Foreign Exchange Rate Policies

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), monetary authorities in East Asia (including Southeast Asia) have adopted a variety of foreign exchange rate policies, varying from Hong Kong’s currency board system which links the Hong Kong dollar to the U.S. dollar, to the “independently floating” exchange rates of Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea. Most Asian monetary authorities have adopted “managed floats” that allow their currency to fluctuate within a limited range over time as part of a larger economic policy. Regardless of their exchange rate policies, monetary authorities on occasion may intervene in foreign exchange (forex) markets in an effort to dampen destabilizing fluctuations in the value of their currencies.

Legislation has been introduced during past Congresses designed to pressure nations seen as “currency manipulators” to allow their currencies to appreciate against the U.S. dollar. The Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-125) requires the Secretary of the Treasury to provide Congress every 180 days with “enhanced analysis of macroeconomic and exchange rate policies” for each major trading partner that has a significant trade surplus with the United States, a current account surplus, and “engaged in persistent one-sided intervention in the foreign exchange market.” In its latest report, Treasury determined that “no major trading partner met all three criteria for the current reporting period.” Treasury did place six major trading partners—China, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, and Taiwan—on its “Monitoring List.” Four of those six major trading partners are in East Asia. In the 115th Congress, the Currency Reform for Fair Trade Act (H.R. 2039) would allow the imposition of countervailing duties on goods imported from a foreign country whose currency is determined to be “fundamentally undervalued” in accordance with the provisions of the act.

Most East Asian monetary authorities consider a “managed float” exchange rate policy conducive to their economic goals and objectives. A “managed float” can reduce exchange rate risks, which can stimulate international trade, foster domestic economic growth, and lower inflationary pressures. It can also lead to serious macroeconomic imbalances if the currency is, or becomes, severely overvalued or undervalued. A managed float usually means that the nation has to impose restrictions on the flow of financial capital or lose some autonomy in its monetary policy.

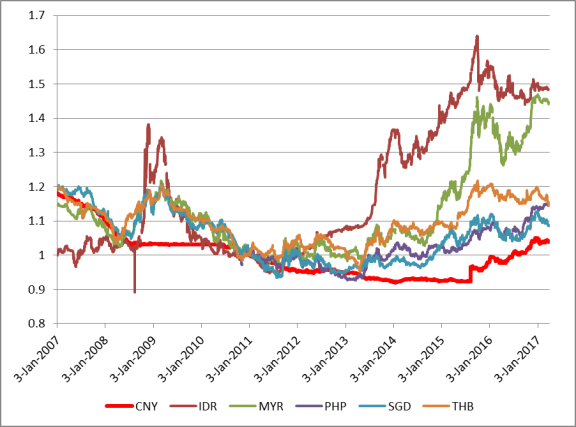

Over the last 10 years, the governments of East Asia have differed in their response to the fluctuations in the value of the U.S. dollar. China, for example, allowed its currency, the renminbi, gradually to appreciate against the U.S. dollar between 2007 and 2015, and has been actively intervening in foreign exchange (forex) markets since then to prevent the depreciation of its currency. Indonesia, however, has allowed its currency, the rupiah, to depreciate in value relative to the U.S. dollar over the last decade.

Between 2011 and 2013, some Southeast Asia nations—such as Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand—appeared to have adopted exchange rates regimes to keep their currencies relatively stable with respect to China’s renminbi. This supposed “renminbi bloc” may have emerged because those nations’ economic and trade ties were increasingly with China. In addition, China was actively promoting the use of its currency for trade settlements, particularly in Asia. Exchange rate patterns for the last four years, however, have led some analysts to suggest the “renminbi bloc” may have weakened.

This report will be updated as events warrant.

East Asia's Foreign Exchange Rate Policies

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Types of Exchange Rate Policies

- East Asia's Exchange Rate Policies

- Emerging Renminbi Bloc?

- The Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015

- Exchange Rate Policies and Issues for Congress

Figures

Summary

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), monetary authorities in East Asia (including Southeast Asia) have adopted a variety of foreign exchange rate policies, varying from Hong Kong's currency board system which links the Hong Kong dollar to the U.S. dollar, to the "independently floating" exchange rates of Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea. Most Asian monetary authorities have adopted "managed floats" that allow their currency to fluctuate within a limited range over time as part of a larger economic policy. Regardless of their exchange rate policies, monetary authorities on occasion may intervene in foreign exchange (forex) markets in an effort to dampen destabilizing fluctuations in the value of their currencies.

Legislation has been introduced during past Congresses designed to pressure nations seen as "currency manipulators" to allow their currencies to appreciate against the U.S. dollar. The Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-125) requires the Secretary of the Treasury to provide Congress every 180 days with "enhanced analysis of macroeconomic and exchange rate policies" for each major trading partner that has a significant trade surplus with the United States, a current account surplus, and "engaged in persistent one-sided intervention in the foreign exchange market." In its latest report, Treasury determined that "no major trading partner met all three criteria for the current reporting period." Treasury did place six major trading partners—China, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, and Taiwan—on its "Monitoring List." Four of those six major trading partners are in East Asia. In the 115th Congress, the Currency Reform for Fair Trade Act (H.R. 2039) would allow the imposition of countervailing duties on goods imported from a foreign country whose currency is determined to be "fundamentally undervalued" in accordance with the provisions of the act.

Most East Asian monetary authorities consider a "managed float" exchange rate policy conducive to their economic goals and objectives. A "managed float" can reduce exchange rate risks, which can stimulate international trade, foster domestic economic growth, and lower inflationary pressures. It can also lead to serious macroeconomic imbalances if the currency is, or becomes, severely overvalued or undervalued. A managed float usually means that the nation has to impose restrictions on the flow of financial capital or lose some autonomy in its monetary policy.

Over the last 10 years, the governments of East Asia have differed in their response to the fluctuations in the value of the U.S. dollar. China, for example, allowed its currency, the renminbi, gradually to appreciate against the U.S. dollar between 2007 and 2015, and has been actively intervening in foreign exchange (forex) markets since then to prevent the depreciation of its currency. Indonesia, however, has allowed its currency, the rupiah, to depreciate in value relative to the U.S. dollar over the last decade.

Between 2011 and 2013, some Southeast Asia nations—such as Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand—appeared to have adopted exchange rates regimes to keep their currencies relatively stable with respect to China's renminbi. This supposed "renminbi bloc" may have emerged because those nations' economic and trade ties were increasingly with China. In addition, China was actively promoting the use of its currency for trade settlements, particularly in Asia. Exchange rate patterns for the last four years, however, have led some analysts to suggest the "renminbi bloc" may have weakened.

This report will be updated as events warrant.

The exchange rate policies of some East Asian nations—in particular, China, Japan, and South Korea—have been sources of tension with the United States in the past and remain so in the present. Some analysts and Members of Congress maintain that some countries have intentionally kept their currencies undervalued for a period of time in order to keep their exports price competitive in global markets. Some argue that these exchange rate policies constitute "currency manipulation" and violate Article IV, Section 1(iii) of the Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund, which stipulates that "each member shall avoid manipulating exchange rates or the international monetary system in order to prevent effective balance of payments adjustment or to gain an unfair competitive advantage over other members."1

The Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-125) requires the Department of the Treasury to "undertake an enhanced analysis of exchange rates and externally‐oriented policies for each major trading partner that has (1) a significant bilateral trade surplus with the United States, (2) a material current account surplus, and (3) engaged in persistent one‐sided intervention in the foreign exchange market."2 In its semiannual report to Congress released in April 2017, "Treasury has found in this Report that no major trading partner met all three criteria."3 Treasury did, however, identify six major trading partners to include on its "Monitoring List": China, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, and Taiwan. Four of the six trading partners are East Asian economies.

This report examines the de facto foreign exchange rate policies adopted by the monetary authorities of East Asian governments.4 At one extreme, Hong Kong has maintained a "linked" exchange rate with the U.S. dollar since 1983, under which the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) is required to intervene to keep the exchange rate between 7.75 and 7.85 Hong Kong dollars (HKD) to the U.S. dollar (USD).5 Such an arrangement is often referred to as a "fixed" or "pegged" exchange rate. At the other extreme, Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea have reportedly allowed their currencies to float freely in foreign exchange (forex) markets over the last few years—an exchange rate arrangement often referred to as a "free float." However, all three nations—like the United States—have intervened in international currency markets to influence fluctuations in the exchange rate.6 Most of East Asia's governments, however, have chosen exchange rate policies between these two extremes in the form of a "managed float."

Types of Exchange Rate Policies

There are a number of different types of exchange rate policies that a nation may adopt, depending on what it perceives to be in its best interest economically and/or politically.7 At one extreme, a country may decide to allow the value of its currency to fluctuate relative to other major currencies in international foreign exchange (forex) markets—a policy commonly referred to as a "free float." One advantage of a "free float" policy over other exchange rate policies is that it permits the nation more autonomy with its domestic monetary policy. However, disadvantages of a "free float" policy include greater exchange-rate risk for international transactions, potentially destabilizing balance sheet effects, and possible rapid shifts in capital flows.

At the other extreme, a nation may decide to fix the value of its currency relative to another currency or a bundle of currencies—usually referred to as a "pegged" exchange rate policy. Pegged exchange rate policies can take several forms. The pegged exchange rate may be set by law, without special provisions to defend the value of the currency. Alternatively, a nation may create a "currency board"—a monetary authority that holds sufficient reserves to convert the domestic currency into the designated reserve currency at a predetermined exchange rate. The currency board utilizes those reserves to intervene in international forex markets to maintain the fixed exchange rate. For example, Hong Kong's three designated currency-issuing banks—The Bank of China, HSBC, and Standard Chartered Bank—must deposit with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority sufficient U.S.-dollar-denominated reserves to cover their issuance of Hong Kong dollars at the designated exchange rate of HKD 7.80 = USD 1.00. Some economies that are heavily dependent on trade—such as Hong Kong and Singapore—perceive extensive currency volatility as a burden to trading enterprises, and manage their currencies to avoid it. An advantage of a pegged exchange rate is that it virtually eliminates exchange-rate risk. Disadvantages are the loss of autonomy in domestic monetary policy, potentially rapid changes in domestic prices (including fixed asset values), and exposure to speculative attacks on the pegged exchange rate.

A third common exchange rate policy is a "managed float." A nation that adopts a "managed float" allows the value of its domestic currency to fluctuate in international forex markets until certain designated economic indicators reach critical levels. In some cases, the country may designate a band around a determined exchange rate, and intervene in international forex markets if its currency hits the upper or lower value limits.8

One special form of a managed float is a "crawling peg," in which the nation allows its currency gradually to appreciate or depreciate in value against one or more other currencies over time. China initiated a "crawling peg" policy on July 21, 2005, which it maintained until the summer of 2008, a period in which the renminbi appreciated 21% against the U.S. dollar.9 Other forms of managed float policies do not rely on the exchange rate but on other economic factors such as the trade balance, current account balance, inflation, and overall economic growth.

Source: International Monetary Fund, "Table 2: De Facto Classification of Exchange Rate Regimes and Monetary Policy Framework, April 30, 2016," as published in Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions, October 2016. Note: IMF report does not include Macau, North Korea, or Taiwan. |

Contemporary economic theory asserts that a nation cannot simultaneously maintain a fixed exchange rate, free capital movement, and an independent monetary policy. If a nation wishes to peg its currency and allow free capital movement (for example, Hong Kong) it must tie its monetary policy to that of the reserve currency nation (for Hong Kong, the United States). Many nations with pegged exchange rates choose to restrict the movement of capital to allow them greater autonomy in their monetary policies (such as anti-inflation measures, interest rate adjustments, or regulating the money supply).

East Asia's Exchange Rate Policies

Table 1 lists the current de facto exchange rate policies of East Asia according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as of April 30, 2016.10 According to the IMF, only Japan allows its currency, the yen, to float freely on international foreign exchange (forex) markets. Five nations allow their currencies to float, but they reserve the right to intervene in forex markets to maintain stability. Seven countries manage their exchange rates according to certain economic objectives, such as domestic price stability or moderate swings in the forex rate relative to one or more currencies. Brunei and Hong Kong operate a currency board system that effectively pegs their exchange rates. The Hong Kong dollar is pegged to the U.S. dollar; the Brunei dollar is pegged to the Singaporean dollar.

Categorizing a government's exchange rate policy can be complicated, particularly during periods of financial turbulence, as was seen, for example, during the global financial crisis of 2008. For example, according to South Korea's central bank, the Bank of Korea, the nation's official exchange rate policy has been a free floating system since December 1997.11 However, it was reported that the South Korean government sold about $1 billion for won on March 18, 2008, to stop a "disorderly decline" in the value of Korea's currency (see Figure 1).12 There were also reports that Korea sold more dollars for won in early April 2008.13 At the time, some forex analysts claimed that the new South Korean government had adopted a de facto pegged exchange rate policy of holding the exchange rate between the won and the U.S. dollar at 975-1,000 to 1.14 The value of the won declined further to nearly 1,500 won to the U.S. dollar in the spring of 2009, before gradually recovering over the next four years to about 1,100 won to the U.S dollar.15

Allegations of South Korea's intervention into forex markets reappeared in 2015 and 2016, when the won experienced another period of sustained depreciation against the U.S. dollar.16 The U.S. Treasury's Report to Congress on International Economic and Exchange Rate Policies, released on October 19, 2015, indicated that South Korea appeared to have attempted to resist the appreciation of the won in early 2015, only to switch to efforts to prevent the won's depreciation in July and August.17 In February 2016, the Bank of Korea stated that the recent declines in the value of the won were "excessive" and that it was concerned about possible "herd behavior" in forex markets, contributing to speculation that Bank of Korea would intervene in forex markets to support the won.18 Claims that South Korea was intervening in forex markets resurfaced in early 2017; the South Korean government sent a letter to the Financial Times, denying claims that it was managing exchange rates to prevent the won's appreciation.19 One South Korean think tank conjectured (incorrectly) that the Department of the Treasury might identify South Korea as a currency manipulator in its April 2017 report, given President Trump's statements about currency manipulation and its alleged negative effects on the U.S. economy.20

Another source of complication arises when there is a seeming discrepancy between the official exchange rate policy and observed forex market trends. For example, China officially maintained a "crawling peg" policy prior to the global financial crisis that allowed its currency—the renminbi—to adjust in value with respect to an undisclosed bundle of currencies within a specified range each day. In theory, this allowed the renminbi to appreciate or depreciate in value gradually over time, depending on market forces.

After the global financial crisis began in late 2007, however, the renminbi was comparatively stable in value relative to the U.S. dollar from July 2008 to May 2010 (see Figure 1). Initially, this led some analysts to assert that China had abandoned the crawling peg in favor of a pegged exchange rate. Other analysts maintained that the stability of the renminbi with respect to the U.S. dollar was an artifact of the basket of currencies being used by China. Because some major currencies strengthened against the U.S. dollar while others weakened, the weighted average used by China in determining the band for the crawling peg has resulted in a relatively unchanged value when compared to the U.S. dollar. On June 19, 2010, China's central bank, the People's Bank of China, announced it would "proceed further with reform of the RMB exchange rate regime and to enhance the RMB exchange rate flexibility," implying that it had been intentionally maintaining a stable exchange rate during the global economic downturn.21 Starting from the summer of 2010, the RMB once again gradually strengthened against the U.S. dollar to around 6.13 yuan to the U.S. dollar as of February 2015. Since then, the renminbi has weakened against the dollar. As of March 31, 2017, the exchange rate was 6.89 yuan = 1.0 U.S. dollar.

Japan's yen has undergone major shifts in value relative to the U.S. dollar over the past 10 years, ranging from a low of 125.35 yen to the U.S. dollar in June 2015 to a high of 76.14 yen to the U.S. dollar in February 2012 (see Figure 1). The fluctuations in the value of the yen have also shown some major shifts, such as its strong appreciations in late 2008 and early 2016, or its major depreciations in the winter of 2012-2013, the autumn of 2014, and the end of 2016.

Analysts differ on the causes for the shifting value of the Japanese yen. Financial news reports during that time generally maintained that the fluctuations in the value of the yen reflected market confidence (or lack thereof) in Japan's economy and the Bank of Japan's monetary policy.22 According to these accounts, the weakening of the yen is the result of expansionary fiscal and monetary policies, part of the government's program to stimulate economic growth in Japan ("Abenomics"). However, some U.S. business leaders assert that the decline in the value of the yen in 2015 was the result of Japanese government intervention in foreign exchange markets.23 The Abe government and the Bank of Japan repeatedly denied claims that they were actively attempting to lower the value of the yen relative to the U.S. dollar, asserting their economic policies are designed to stimulate growth and end price deflation.24 The last confirmed time Japan intervened in foreign exchange markets was in 2011.

Emerging Renminbi Bloc?

There are indications that some East Asian monetary authorities monitor the region's exchange rates and attempt to keep the relative value of their currencies in line with the value of selected currencies in the region. These "competitive" adjustments in exchange rates are allegedly made to maintain the competitiveness of a nation's exports on global markets.

Some observers have speculated that competitive adjustments are particularly an issue in Southeast Asia, especially countries with closer economic ties to China.25 For example, one scholar noted in 2007 that, "Countries that trade with China and compete with China in exports to the third market are keen not to allow too much appreciation of their own currencies vis-à-vis the Chinese RMB [renminbi]."26 The scholar, Taketoshi Ito, also speculated, "China most likely is more willing to accept RMB appreciation if neighboring countries, in addition [South] Korea and Thailand, allow faster appreciation."27

Trends in selected Southeast Asian exchange rates over the last 10 years have led some analysts to surmise that a "renminbi bloc" emerged in 2007 and early 2008, and reemerged between 2011 and 2013 (see Figure 2). In 2007 and until March 2008, the currencies of Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand generally followed the appreciation of China's RMB against the U.S. dollar. As the 2008 global financial crisis spread in 2008, first the Thai bhat, then the Malaysian ringgit, and finally the Singaporean dollar began to weaken relative to the U.S. dollar, while China's RMB remained relatively fixed in value. Starting in late 2010 and continuing until the spring of 2013, the currencies of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand seemingly once again followed the gradual strengthening of China's RMB against the U.S. dollar. Since then, the Southeast Asian currencies have all weakened relative to the U.S. dollar, while the renminbi continued to strengthen until August 2015. The more recent divergence in exchange rates could be interpreted as a weakening of what some analysts previously had suggested were signs of an emerging "renminbi bloc."

In addition to the apparent similar movements in the value of their currencies relative to China's renminbi, there is other anecdotal evidence consistent with the existence of a "renminbi bloc" in Southeast Asia, at least for a period of time. According to International Monetary Fund trade data, China has emerged as the largest trading partner for many Asian nations, including Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. China has also been actively promoting the use of the renminbi to settle trade payments, as well as to arrange currency swap agreements.28

While the apparent weakening in 2008 of what some analysts had suggested was an emerging "renminbi bloc" may have been attributable to the global financial crisis, the more pronounced divergence of exchange rates in 2013 and thereafter is not as readily explained. More recently, some observers speculate that slower economic growth in China and tightening monetary policy in the United States led to slower growth for the Southeast Asian economies and applied downward pressure on their currencies.29 Meanwhile, China's RMB continued its gradual appreciation relative to the U.S. dollar until August 2015.

The Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015

For nearly 30 years, the Department of the Treasury has been required to provide biannual reports to Congress on the exchange rate policies of foreign countries. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-418) required the Secretary of the Treasury to

analyze on an annual basis the exchange rate policies of foreign countries, in consultation with the International Monetary Fund, and consider whether countries manipulate the rate of exchange between their currency and the United States dollar for purposes of preventing effective balance of payments adjustments or gaining unfair competitive advantage in international trade.

The act also stipulated that the Secretary of the Treasury

shall submit to the Committee on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs of the Senate, on or before October 15 of each year, a written report on international economic policy, including exchange rate policy. The Secretary shall provide a written update of developments six months after the initial report.

The first report was provided to Congress in October 1988. Since the act was enacted, the Department of the Treasury has identified South Korea and Taiwan in 1988 and China in 1992 for manipulating their currencies under the Trade Act's terms.

In February 2016, Congress passed the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (TFTEA; P.L. 114-125), which, in addition to other provisions,30 requires the Secretary of the Treasury to "submit to the appropriate committees of Congress a report on the macroeconomic and currency exchange rate policies of each country that is a major trading partner of the United States." These reports are due every 180 days; the "appropriate committees" are the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs and the Committee on Finance of the Senate; and the Committee on Financial Services and the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives. The TFTEA also requires the report contain

an enhanced analysis of macroeconomic and exchange rate policies for each country that is a major trading partner of the United States that has—

(I) a significant bilateral trade surplus with the United States;

(II) a material current account surplus; and

(III) engaged in persistent one-sided intervention in the foreign exchange market.

The latest report was released on April 14, 2017.31 According to its analysis, "Treasury has found in this Report that no major trading partner met all three criteria for the current reporting period [August-December 2016]." The report did, however, place six major trading partners—China, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, and Taiwan—on a "Monitoring List" of "major trading partners that merit close attention to their currency practices." Four of the six major trading partners are in East Asia. Among the report's observations on these four major trading partners were the following:

- China—"China has a long track record of engaging in persistent, large-scale, one-way foreign exchange intervention, doing so for roughly a decade to resist renminbi (RMB) appreciation even as its trade and current surpluses soared." The report, however, also noted that China has allowed the renminbi to appreciate in recent years, and "China's recent intervention in foreign exchange markets has sought to prevent a rapid RMB depreciation [emphasis in original text] that would have negative consequences for the United States, China, and the global economy."

- Japan—"Japan has a significant bilateral trade surplus with the United States, with a goods surplus of $69 billion [in 2016]. Japan has not intervened in the foreign exchange market, however, in five years."

- South Korea—"Korea has a track record of asymmetric foreign exchange interventions, highlighting the urgency of authorities durably limiting foreign exchange intervention only to circumstances of disorderly exchange market conditions and making foreign exchange operations more transparent. In its last analysis of the won, the IMF maintained its assessment that the won is undervalued."

- Taiwan—"Taiwan has a track record of asymmetric foreign exchange interventions.… Treasury urges Taiwan's authorities to demonstrate a durable shift to a policy of limiting foreign exchange interventions to only exceptional circumstances of disorderly market conditions, and to increase the transparency of foreign exchange market intervention and reserve holdings."

Exchange Rate Policies and Issues for Congress

While U.S. policy has generally supported the adoption of "free float" exchange rate policies, many East Asian governments consider a "managed float" exchange rate policy more conducive to their overall economic goals and objectives. In part, East Asian governments may be resistant to a "free float" policy because of the commonly held view in Asia that the economies with more liberal exchange rate policies suffered more during the 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis than the economies that moved more forcefully to maintain pegged or managed exchange rates.32 As a result, there may be skepticism about U.S. recommendations for adoption of "free float" exchange rate policies.

In addition, it is uncertain if the adoption of "free float" exchange rate policies by more monetary authorities in East Asia would significantly reduce the U.S. trade deficits with countries in the region.33 The United States generally runs trade deficits with East Asia. Among economists, there is no consensus that the resulting appreciation of East Asian currencies against the U.S. dollar would either significantly increase overall U.S. exports or reduce U.S. imports. However, for some price-sensitive industries where U.S. companies are competitive, the appreciation of a competing nation's currency may stimulate U.S. export growth and/or a decline in U.S. imports.

The debate over foreign exchange rate policies of other nations and its impact on the U.S. economy continues in the 115th Congress. The Currency Reform for Fair Trade Act (H.R. 2039) would amend the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. chapter 4) to permit the imposition of countervailing duties on the imports of countries whose currency is determined to be "fundamentally undervalued." The act also stipulates that a currency is to be determined undervalued if

- 1. The government of the country "engages in protracted, large-scale intervention in one or more foreign exchange markets";

- 2. The real effective exchange rate34 of the currency is undervalued by at least 5%;

- 3. The country has experienced "significant and persistent global current account surpluses"; and

- 4. The foreign asset reserves held by the government of the country exceed

- the amount necessary to repay the government's debt obligations for the next 12 months;

- 20% of the country's money supply; and

- the value of the country's imports for the previous four months.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

The IMF Articles of Agreement are available at https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/aa/. For more background on currency manipulation and exchange rates, see CRS Report R43242, Current Debates over Exchange Rates: Overview and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed], and CRS In Focus IF10049, Debates over "Currency Manipulation", by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 2. |

Department of the Treasury, Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners of the United States, April 14, 2017. |

| 3. |

Ibid. |

| 4. |

In some cases, there is a perceived discrepancy between the official (de jure) exchange rate policy and the observed de facto exchange rate policy. This report will focus primarily on the de facto exchange rate policies. |

| 5. |

For more information about Hong Kong's exchange rate policy, see the HKMA's web page: http://www.info.gov.hk/hkma/eng/currency/link_ex/index.htm. |

| 6. |

According to the Federal Reserve Bank in New York, the United States intervened in foreign exchange markets twice between August 1995 and December 2006. For more information see http://www.newyorkfed.org/aboutthefed/fedpoint/fed44.html. |

| 7. |

For more background on exchange rates, see CRS Report R43242, Current Debates over Exchange Rates: Overview and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed] CRS In Focus IF10049, Debates over "Currency Manipulation", by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 8. |

This is frequently done by using a "trade-weighted basket" of currencies, in which the relative importance of each currency is based on the volume of bilateral trade with the nation. The rise of Asia's bilateral trade flows with China is likely a contributing factor to the emergence of a "renminbi bloc." |

| 9. |

For more information on China's exchange rate policies, see CRS In Focus IF10139, China's Currency Policy, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 10. |

The IMF reports differentiates between the exchange rate policy in practice (de facto) from that described in laws or official policy statements (de jure). |

| 11. |

See the Bank of Korea's webpage for a description of its exchange rate policy: http://www.bok.or.kr/broadcast.action?menuNaviId=678. |

| 12. |

Yoo Choonsik and Cheon Jong-woo, "S. Korea Sold Dollars to Calm Markets-Dealers," Reuters, March 18, 2008. |

| 13. |

"Intervention Detected as S. Korea Won Pares Gains," Reuters, April 4, 2008. |

| 14. |

Yoo Choonsik, "S. Korea Won Hit by New Policy, Consumption at Risk," Reuters, April 7, 2008. |

| 15. |

In 2014, financial analysts speculated that the Bank of Korea intervened to slow the appreciation of the won, but the reports are unconfirmed. See, for example, Neil Dennis, "Korean Won Falls on Suspected Intervention," Financial Times, July 14, 2014. |

| 16. |

See Kentaro Ogura, "Won Keeps Rising Despite Market Intervention," Nikkei Asian Review, April 20, 2015; and Christine Kim and Yena Park, "South Korea in Suspected $2 Billion Intervention after Stern Warning," Reuters, February 19, 2016. |

| 17. |

Department of the Treasury, Report to Congress on International Economic and Exchange Rate Policies, October 19, 2015. |

| 18. |

Jiyuen Lee and Cynthia Kim, "Won's Slump Sparks Verbal Intervention from South Korea," Bloomberg, February 16, 2016. |

| 19. |

Letter from Lee Young-joo, Ministry of Strategy and Finance, and Lee Seungheon, Bank of Korea, to Financial Times, February 16, 2017. |

| 20. |

Jiyuen Lee, "South Korea May Be Named Currency Manipulator, Think Tank Warns," Bloomberg, January 4, 2017. |

| 21. |

The text of the People's Bank of China statement is available online at http://www.pbc.gov.cn/english/detail.asp?col=6400&id=1488. |

| 22. |

For example, see Neil Dennis, "Yen Weakens on Japan Growth Concerns," Financial Times, November 14, 2013; and Daniel Bases, "Yen Slammed by BoJ Easing, Falls to Near-seven Year Low," Reuters, October 31, 2014. |

| 23. |

For example, see Keith Naughton, "Ford CFO Says Toyota Gains $10 Billion Advantage on Weak Yen," Japan Times, February 2, 2015. |

| 24. |

For example, "Japan Denies Currency Manipulation Claims Ahead of G20," Reuters, January 25, 2013; and Gerard Baker and Jacob M. Schlesinger, "Bank of Japan's Kuroda Signals Impatience With Abe Government," Wall Street Journal, May 23, 2014. |

| 25. |

See, for example, Takatoshi Ito, A New Financial Order in Asia: Will a RMB Bloc Emerge?, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 22755, Cambridge, MA, October 2016, http://www.nber.org/papers/w22755. |

| 26. |

Takatoshi Ito, "The Influence of the RMB on Exchange Rate Policy of Other Economies," paper presented at Peterson Institute for International Economics Conference, October 19, 2007. |

| 27. |

Ibid. |

| 28. |

For more about the growing use of the renminbi in the region, see Il Houng Lee and Yung Chui Park, Use of National Currencies for Trade Settlement in East Asia: A Proposal, Asian Development Bank Institute, ADBI Working Paper Series, Tokyo, Japan, April 2014, http://www.adbi.org/files/2014.04.11.wp474.currencies.trade.east.asia.pdf. |

| 29. |

For example, see Landon Thomas, Jr., "Currency Devaluations by Asian Tigers Could Hinder Global Growth," New York Times, January 8, 2016. |

| 30. |

For more about the TFTEA, see CRS Report R43242, Current Debates over Exchange Rates: Overview and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 31. |

Department of the Treasury, Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners of the United States, Washington, DC, April 14, 2017. |

| 32. |

For more about Asian views of the causes of Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, see Pradumna B. Rana, "The East Asian Financial Crisis—Implications for Exchange Rate Management," Asian Development Bank, EDRC Briefing Notes, Number 5, October 1998; and Ramkishen S. Rajan, "Asian Exchange Rate Regimes since the 1997-98 Crisis," Singapore Centre for Applied and Policy Economics, September 2006. Some analysts, however, have argued that pegged exchange rates and capital controls in some countries were contributing factors to the Asian financial crisis. |

| 33. |

In his abstract of his 2006 study, "The Effect of Exchange Rate Changes on Trade in East Asia," Willem Thorbecke concluded, "The results indicate that exchange rate elasticities for trade between Asia and the U.S. are not large enough to lend confidence that a depreciation of the dollar would improve the U.S. trade balance with Asia." Complete text of paper available at http://www.rieti.go.jp/en/publications/summary/06030003.html. However, in a 2010 examination of China's trade with the United States, William Cline of the Peterson Institute for International Economics maintains that a stronger renminbi will significantly reduce the U.S. trade deficit with China (a copy of his policy brief is available at http://www.iie.com/publications/interstitial.cfm?ResearchID=1636). |

| 34. |

The real effective exchange rate is a weighted average of the country's currency relative to a basket of other currencies, after an adjustment has been made for inflation. |