Holocaust-Era Insurance Claims: Background and Issues for Congress

In November 1998, U.S. insurance regulators, six European insurers, international Jewish organizations, and the State of Israel agreed to establish the International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims (ICHEIC). ICHEIC was tasked with identifying policyholders and administering payment of hundreds of thousands of Holocaust-era insurance policies that had never been honored by European insurance companies. It ended its claims process in March 2007, having offered payments totaling about $306 million to 48,263 claimants. An additional $169 million was allocated to a “humanitarian fund” for Holocaust survivors and Holocaust education and remembrance.

Throughout its existence, ICHEIC was criticized, including by some Members of Congress, for delays in its claims process, for conducting its activities with a lack of transparency, and for allegedly honoring an inadequate number of claims. Although they acknowledge initial delays in the claims process, ICHEIC supporters—among them successive U.S. Administrations and European governments—argue that the process was fair and comprehensive, especially given the unprecedented legal and historical complexities of the task.

Many Members of Congress have shown a long-standing interest in seeking to obtain compensation for Holocaust survivors and their heirs for unpaid insurance policies. Hearings before the House Committee on Government Reform between 2001 and 2003 exposed broad criticism of ICHEIC, and legislation proposed in the 107th-115th Congresses sought to provide survivors alternative legal mechanisms to pursue claims (including companion bills H.R. 762 and S. 258 in the 115th Congress). These proposals were never enacted and were opposed by U.S. Administrations, which considered ICHEIC the exclusive vehicle for resolving Holocaust-era insurance claims.

Proponents of congressional legislation have argued that both the ICHEIC process and previous agreements between the United States and European governments failed to compensate a significant number of Holocaust survivors and/or their heirs and beneficiaries. These proponents contend that following ICHEIC’s closure, the courts represent one of the few, if not the only, remaining avenues by which to pursue claims. Critics counter that by effectively reversing past commitments made by the U.S. government, the proposed legislation could damage future cooperation with European governments on other Holocaust compensation and restitution issues while enabling what they predict would amount to costly but fruitless litigation.

This report aims to inform congressional deliberation on Holocaust-era insurance issues by providing background on Holocaust-era compensation and restitution issues; an overview of ICHEIC, including criticism and support of its claims process and Administration policy on ICHEIC; and an overview of litigation on Holocaust-era insurance claims and past legislative proposals.

Holocaust-Era Insurance Claims: Background and Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- General Background on Post-War Compensation

- Background on Insurance Issues

- The International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims (ICHEIC)

- Administration Policy on ICHEIC

- Key Points of Contention

- The ICHEIC Claims Process: Management and Oversight Issues

- ICHEIC Research and Publication of Names

- Policy Valuation

- Litigation of Holocaust-Era Insurance Claims

- Congressional Concerns and Proposed Legislation

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

In November 1998, U.S. insurance regulators, six European insurers, international Jewish organizations, and the State of Israel agreed to establish the International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims (ICHEIC). ICHEIC was tasked with identifying policyholders and administering payment of hundreds of thousands of Holocaust-era insurance policies that had never been honored by European insurance companies. It ended its claims process in March 2007, having offered payments totaling about $306 million to 48,263 claimants. An additional $169 million was allocated to a "humanitarian fund" for Holocaust survivors and Holocaust education and remembrance.

Throughout its existence, ICHEIC was criticized, including by some Members of Congress, for delays in its claims process, for conducting its activities with a lack of transparency, and for allegedly honoring an inadequate number of claims. Although they acknowledge initial delays in the claims process, ICHEIC supporters—among them successive U.S. Administrations and European governments—argue that the process was fair and comprehensive, especially given the unprecedented legal and historical complexities of the task.

Many Members of Congress have shown a long-standing interest in seeking to obtain compensation for Holocaust survivors and their heirs for unpaid insurance policies. Hearings before the House Committee on Government Reform between 2001 and 2003 exposed broad criticism of ICHEIC, and legislation proposed in the 107th-115th Congresses sought to provide survivors alternative legal mechanisms to pursue claims (including companion bills H.R. 762 and S. 258 in the 115th Congress). These proposals were never enacted and were opposed by U.S. Administrations, which considered ICHEIC the exclusive vehicle for resolving Holocaust-era insurance claims.

Proponents of congressional legislation have argued that both the ICHEIC process and previous agreements between the United States and European governments failed to compensate a significant number of Holocaust survivors and/or their heirs and beneficiaries. These proponents contend that following ICHEIC's closure, the courts represent one of the few, if not the only, remaining avenues by which to pursue claims. Critics counter that by effectively reversing past commitments made by the U.S. government, the proposed legislation could damage future cooperation with European governments on other Holocaust compensation and restitution issues while enabling what they predict would amount to costly but fruitless litigation.

This report aims to inform congressional deliberation on Holocaust-era insurance issues by providing background on Holocaust-era compensation and restitution issues; an overview of ICHEIC, including criticism and support of its claims process and Administration policy on ICHEIC; and an overview of litigation on Holocaust-era insurance claims and past legislative proposals.

Introduction

General Background on Post-War Compensation

The 1952 Luxembourg Reparations Agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), Israel, and the Conference on Jewish Material Claims against Germany (Claims Conference) marked the first and most significant of a series of post-war West German initiatives that have resulted in total German government payments of an estimated $84 billion (about €76 billion) to Jewish and non-Jewish victims of Nazi crimes and their heirs.1 While most agree that Germany will never be able to adequately compensate for Nazi atrocities, many scholars and advocates for Holocaust victims have commended the compensation and restitution efforts of successive German governments.2

The governments of other Western European countries known to have collaborated with the Nazis also undertook compensation efforts in the years after the Second World War. However, with the possible exception of those in the Netherlands, these efforts are generally thought to have been less comprehensive than West Germany's. In the years following the war, these countries, whose economies had been devastated, tended to argue that Germany should assume responsibility to compensate for Nazi crimes. The communist governments of East Germany and Central and Eastern Europe offered minimal restitution and/or compensation, if any.3

The fall of the Berlin Wall (1989) and collapse of the Soviet Union (1991) led to renewed efforts by Jewish organizations, Holocaust survivors, and the U.S. and Israeli governments to obtain compensation for survivors who had lived or continued to live in Central and Eastern Europe.4 Initial efforts focused largely on property restitution and compensating victims of forced and slave labor. Simultaneously, a series of lawsuits against European companies were filed in American state and federal courts on behalf of Jewish Holocaust survivors; these shed light on the fact that up to billions of dollars worth of assets seized by the Nazis from individual citizens and deposited in private and national banks throughout Western Europe had never been returned. In March 1997, the first lawsuits focusing exclusively on the issue of unpaid Holocaust-era life insurance policies were filed in New York (the so-called "Cornell Class Action" against 16 European insurers).5

The mid-to-late 1990s' lawsuits against Swiss, German, Austrian, Italian, and French companies brought widespread international attention to the issue of looted Holocaust-era assets, unpaid insurance policies, and dormant bank accounts. Given the immense significance and sensitivity of the issues, and the unprecedented nature of the legal cases before American judges, the U.S. government sought to facilitate settlement of the lawsuits through a series of complex agreements involving national and state governments, class-action lawyers, private industry, and a variety of Jewish and other victims' groups.

Most agree that U.S. Administration efforts to facilitate resolution of these claims by involving a range of interested parties, including national governments, victims, and private industry, played an important role both in securing support for, and impeding subsequent legal challenges to the government-negotiated settlements. The Clinton Administration took the lead in facilitating broad compensation agreements—each with insurance-related components—with German, Austrian, and French companies and their governments. The Clinton Administration was also involved in negotiating a settlement with Swiss banks, although some U.S. officials contended that a lack of Swiss government involvement weakened that agreement, and led to heightened international criticism of Switzerland. According to Stuart Eizenstat, the Clinton Administration's lead official in the negotiations, the damaging effects of a wave of international criticism of Switzerland arising from its perceived poor handling of the "Swiss bank affair" led the German, Austrian, and French governments to proactively seek to resolve pending lawsuits against companies in their countries and stem the possibility of future lawsuits.6 Each of these governments established broad settlement funds to compensate victims of forced and slave labor, looted assets, and insurance policy theft, among other crimes; each also reportedly viewed U.S. government approval of their compensation programs as a top priority. Official U.S. endorsement, it was believed, could ensure that future lawsuits or challenges to the settlements would have difficulty proceeding in American courts.7

Background on Insurance Issues

Insurance markets in pre-World War II Europe were well developed with many policies going further than simply compensating for property damage or providing benefits to a family in the case of the policyholders' death. In addition to providing death benefits, these policies often acted as savings vehicles, similar in some ways to what are known as whole life insurance policies in the United States today. For example, life insurance policies were often purchased intending to provide for a son's education, or to provide for a dowry upon the marriage of a daughter. Such a policy might have run for 20 years, with the policyholder committing to make periodic payments and the insurance company committing to pay a certain sum, known generally as the "face value" of the policy, at the end of the 20 years, or in the case of the death of the policyholder. Such a policy generally would have cancellation provisions, which would allow a policyholder to obtain a "surrender value" prior to the policy's intended end, or, if a policyholder wished to keep the contract but not pay further premiums, it could be converted to "paid up" status which would result in a smaller face value at the end of the policy.

In the run-up to, and during the conduct of, World War II, the Nazi government made a concerted effort to confiscate assets belonging to Jews in Germany and in various occupied countries.8 At first, these efforts were largely indirect, such as placing high taxes or fees on those emigrating, which necessitated the liquidation of many insurance policies. Later, the confiscation was more direct, with, for example, insurance companies being required to pay insurance proceeds from claims9 or the cash values directly to the government.

Initial post-war efforts in Western Europe to honor unpaid insurance policies—primarily life insurance—belonging to Holocaust victims are widely considered to have been far less comprehensive than other compensation and restitution programs. Several of the countries home to companies known to have sold such policies, including Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, passed laws in the 1950s and 1960s attempting at least partially to honor these policies. However, a variety of factors led these efforts to fall short. These included uncertainty regarding the present value of the policies; difficulties with verification of policy ownership; disagreement over how to compensate the many Jews who were forced to either cash in their policies, or simply surrender them to the Nazis; and an insurance industry in dire economic straits.

As has generally been the case with post-war settlement issues, German and Dutch companies are thought to have done more than others in addressing unpaid insurance policies after the war. In the late 1990s, German insurance giant Allianz went so far as to claim it had honored approximately 70% of its wartime policies sold in Germany—either before the war ended, or through its participation in other post-war compensation programs.10 Critics dispute Allianz's claim, arguing that policyholders were often grossly undercompensated, both during the war and with a greatly devalued currency in the war's aftermath. Other countries home to companies known to have sold insurance policies throughout the Nazi Reich, such as France and Belgium, did not administer any insurance-related compensation programs until the 1990s; and the Italian government appears to have involved itself in the matter minimally, if at all.

Historians agree that of all Holocaust victims, Jews were most likely to have owned substantial life and other insurance policies. Efforts to honor unpaid insurance policies have focused almost exclusively on Jewish victims. The fact that many such Jews lived and purchased policies in Central and Eastern European countries that later became part of the Soviet Bloc—primarily Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia—proved to be a significant complicating factor in post-war efforts to have the policies honored. Many of the companies that sold insurance in these countries no longer exist; however, several Western European companies that accounted for a significant portion of the Central and Eastern European markets continue to operate today. Specifically, the Italian company Generali is known to have been active in Central and Eastern Europe. Generali and others have in the past argued that responsibility to honor these policies was transferred to state-run insurance entities by way of the state takeover and nationalization of the industry under communist rule.11

The International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims (ICHEIC)

In 1997, in response to increasing claims against European insurance companies operating in the United States, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) formed a Working Group on Holocaust Insurance Claims to reach out to Holocaust victims and their heirs to better determine the scope of the problem, and to initiate a dialogue with European insurers about how to resolve the issue of unpaid claims. A series of often emotional and contentious meetings between Holocaust survivors and their heirs, insurance regulators, and insurance companies over the course of the next year resulted in a joint decision to form an independent international commission to resolve unpaid claims.

In August 1998, the NAIC, six European insurers (Allianz, AXA, Basler,12 Generali, Winterhur, and Zurich), the Claims Conference, the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO), and the State of Israel signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) establishing an international commission tasked both with identifying Holocaust victims who had purchased insurance policies from 1920-1945, and administering the repayment of these policies. Members of the International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims (ICHEIC)—chaired by former U.S. Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger—agreed that ICHEIC's claims process would adhere to the following principles:

- The claims process would be free of charge to the claimant;

- ICHEIC would evaluate claims based on relaxed standards of proof—given that a significant number of potential claimants did not possess policy documentation, claimants would not be required to name a specific insurance company or provide documentation of an insurance policy; and

- ICHEIC and participating insurance companies would conduct archival research in order to establish a database of potential policyholders against which to match submitted claims.13

Although the U.S. government did not have a voting representative on ICHEIC's board, state insurance regulators were officially represented through the NAIC, and a State Department representative was granted observer status. In all, the board consisted of Chairman Eagleburger and 12 members: three NAIC representatives; two representatives of Jewish organizations (the Claims Conference and WJRO); a representative of the state of Israel; and six representatives of European insurers and insurance regulators.

ICHEIC's claims process opened in 2000 and closed in March 2007. ICHEIC reports that it offered payments totaling approximately $306 million to 48,263 of about 91,500 eligible claimants. Of the roughly 48,000 claimants who received ICHEIC payment offers, close to 31,300 were offered one-time "humanitarian" payments of $1,000 (see Table 1 for detailed breakdown). Observers and others involved in the process report that rejected claims were often determined to have been honored under previous compensation agreements or were determined to fall short of the relaxed standards established by the commission. Some critics contend that ICHEIC applied these standards inconsistently, rejecting what were often valid claims.14

In addition to the funds paid to individual claimants, ICHEIC allocated $169 million to a "humanitarian fund" overseen by the Claims Conference. Following Claims Conference guidelines, 80% of this fund was designated to be spent on assistance to Holocaust survivors, and 20% on Holocaust education and remembrance.15

Despite ICHEIC's closure, some European insurers, including members of the German Insurance Association (Gesamtverband der Deutschen Versicherungswirtschaft, or GDV) and the Italian company Generali, say they are continuing to accept and honor legitimate claims based on ICHEIC's relaxed standards of proof. According to the GDV, between March 2007 and July 2019, the association received 520 inquiries that resulted in the identification of 317 insurance policies. Of these policies, 130 were determined to be eligible for compensation, while 187 were determined to have been previously paid or compensated for. In total, GDV companies say they have paid $3.2 million for claims brought since March 20, 2007.16

|

# of Claims Received |

# of Offers Made |

Amount Offered |

|

|

Named company |

14,351 |

5,611 |

$124.1 million |

|

No named company, |

16,243 |

7,789 |

$99.0 million |

|

No named company, |

60,111 |

34,158 |

$61.82 million |

|

TOTAL |

90,705 |

48,263 |

$306 million |

Sources: International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims (ICHEIC), Final Statistical Report, at https://icheic.ushmm.org/, ICHEIC, Finding Claimants and Paying Them: The Creation and Workings of the International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims, 2007; interview of ICHEIC representatives, March 2008.

Note: The reported totals encompass some offers not captured in the table made via the following processes: offers made directly by insurance companies to claimants using ICHEIC standards, but outside the ICHEIC process; awards offered through the ICHEIC appeals process; and offers made by ICHEIC partner entities.

Ultimately, ICHEIC received a total of about $550 million from participating insurers (see Table 2). Of this, $350 million was secured from German companies through a watershed 2000 executive agreement between the United States and Germany, in which German government and industry committed $5 billion to compensate former forced and slave laborers and other victims of Nazi crimes.17 $100 million came from Italian insurer Generali, and the remaining $100 million from a U.S.-Austrian executive agreement, and bilateral agreements between ICHEIC and Swiss insurers, and the Dutch, and Belgian insurance associations. In addition to the five insurers on ICHEIC's board, ICHEIC secured the participation of 75 other companies through bilateral agreements with the German, Dutch, and Belgian insurance associations.

|

German Insurance Association |

$350 million |

|

Generali |

$100 million |

|

Swiss Insurers |

$25 million |

|

Austrian General Settlement Fund |

$25 million |

|

Others |

$50 million |

|

Total |

$550 million |

Source: ICHEIC, Finding Claimants and Paying Them: The Creation and Workings of the International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims, 2007.

Note: ICHEIC representatives report that Generali contributed an additional $30 million in claims payments outside the ICHEIC process.

Administration Policy on ICHEIC

U.S. Administrations have consistently endorsed ICHEIC as an important and unprecedented mechanism to provide support and compensation to individuals whose insurance claims were believed unlikely to have been satisfactorily resolved through existing legal channels. The Clinton Administration sought to secure funding for ICHEIC and its claims process as part of the broader compensation agreements it negotiated with the German, Austrian, and French governments in the late 1990's. In exchange for financial commitments made to ICHEIC by German and Austrian companies by way of these agreements, the Clinton Administration agreed to endorse ICHEIC as the exclusive mechanism for resolving unpaid Holocaust-era insurance claims.

The Administration also sought to grant participating German companies so-called legal peace from further action against them in American courts by committing to file statements of interest encouraging dismissal of any future legal action against German companies in the United States.18 As discussed in greater detail below, multiple U.S. state and federal courts have concluded that the federal government's policy position on this issue precludes litigants from pursuing Holocaust-era insurance claims through the judicial process.19

Key Points of Contention

Despite receiving the support of U.S. Administrations, ICHEIC was broadly criticized, including by some Members of Congress.20 Critics put forward the following charges: that ICHEIC's administrative and claims processes suffered from a lack of transparency and oversight; that ICHEIC often failed to live up to its commitment to apply relaxed standards of proof in assessing claims; and that ICHEIC and participating insurance companies failed to make comprehensive policyholder lists available to the public.21 Since ICHEIC's closure, critics have emphasized that the roughly $306 million made available to Holocaust survivors and their heirs falls far short of their estimates of the total value of unpaid Holocaust-era insurance policies, which range anywhere from $17 billion to $200 billion.22 ICHEIC proponents respond that ICHEIC administered a claims-based process, giving all claims fair consideration. They argue, for example, that the fact that the total amount paid by ICHEIC falls short of some estimates of the value of unpaid policies suggests a lack of claimants rather than a flawed claims process.

The ICHEIC Claims Process: Management and Oversight Issues

Critics contend that ICHEIC's claims process suffered from unnecessary and prolonged delays, and that thousands of eligible claimants were ultimately excluded from the process due to poor management and a lack of transparency and legitimate oversight. Contention over ICHEIC management and oversight centered largely on European insurance companies' obligations under ICHEIC, and the extent to which the companies were held accountable to these obligations. Under the terms of the ICHEIC MOU, ultimate responsibility for verifying, accepting, or rejecting submitted claims rested with the insurance companies.

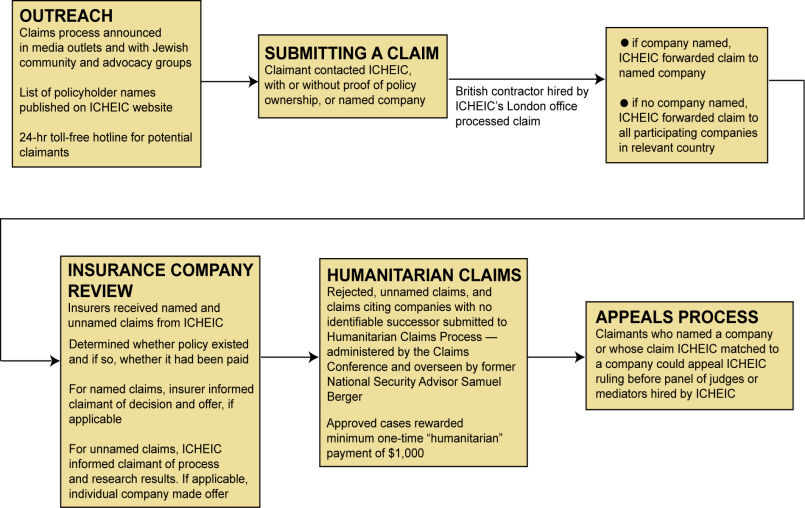

As outlined in Figure 1, ICHEIC staff submitted claims it deemed legitimate to insurance companies, which would, in turn, consult their records to verify whether a policy existed, and whether it had been previously paid. Although participating insurers were required to commission and publicize independent audits of this process, ICHEIC critics contend that audits were often delayed, and that lack of an independent review process allowed room for unfair insurer influence.

ICHEIC proponents argue that publicly available audits and ICHEIC's final results demonstrate that the companies did indeed follow the agreed principles in honoring tens of thousands of unpaid Holocaust-era insurance policies. Clinton and Bush Administration officials and others involved in the process also argue that the ICHEIC claims process, with its relaxed standards of proof and historical research, gave potential claimants a far better opportunity to resolve claims than would have been granted in a U.S. court of law. In response to criticism of insurers' lack of accountability, they emphasize that insurers would not have participated in ICHEIC or any other restitution process without retaining full control over claims decisions. Furthermore, the fact that ICHEIC was incorporated in Switzerland and headquartered in the United Kingdom insulated the organization's decisions from scrutiny under U.S. law.

Initial congressional concerns regarding problems with ICHEIC administration, oversight, and its claims process were brought to light during a November 2001 hearing before the House Committee on Government Reform. During the hearing, critics expressed dismay that ICHEIC had not launched its claims process until early 2000—1½ years after the MOU was signed—and that a year-long "pilot" claims process resulted in what some considered remarkably high rejection rates.23 ICHEIC also was confronted with complaints of high administrative costs and board secrecy. ICHEIC supporters generally acknowledge that the claims process got off to a slow and problematic start, but argue that initial missteps were addressed and that the claims process was ultimately fair and comprehensive.

In the year following the 2001 congressional hearing, an "Executive Monitoring Group" appointed by Chairman Eagleburger to investigate claims handling found widespread mismanagement in insurance company handling of documented claims. As a result, ICHEIC implemented a verification system to "verify" company claims decisions, and compelled participating insurance companies to undergo audits of their claims decisions after 2002.24

|

|

Source: Information taken from ICHEIC, Finding Claimants and Paying Them: The Creation and Workings of the International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims, 2007. |

ICHEIC Research and Publication of Names

One of ICHEIC's most contentious and challenging tasks was to determine and disclose lists of Jewish Holocaust victims who had purchased insurance policies from 1920-1945. Although estimates vary, some studies indicate that between 800,000 to 900,000 polices were sold to eventual Jewish victims of the Holocaust.25 By 2003, ICHEIC's published policyholder lists comprised approximately 520,000 Jewish individuals who purchased insurance policies in Nazi occupied Europe.26 The German insurance industry provided 363,232 policyholder names, over half of the total names published. As well as including records from non-German companies, ICHEIC reports that it carried out extensive archival research in 15 countries that resulted in the discovery of 55,079 Jewish policyholder names representing about 78,000 policies.

The German Insurance Association (GDV) and the German government express confidence that the GDV's published list of just over 360,000 Jewish policyholders is comprehensive, representing all life insurance policies owned by Jewish residents of Germany from 1933-1945.27 To generate the list, the GDV crossed a list of all insurance policyholders in Germany from 1920-1945 (about 8.5 million policies), with a list of Jews residing in Germany between 1933 and 1945 (an estimated 550,000 - 600,000 people). According to the GDV, the list of total policies represented records of 70 insurance companies active in Germany during the time period. The list of Jewish residents was the result of unprecedented archival research in cooperation with The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority, Yad Vashem, in Israel, and over 100 German archives and sources.

While most observers praise the German industry's disclosure of policyholder names, some contend that Generali and other European insurers avoided disclosing their records, often citing privacy concerns. For its part, Generali argues that its contribution of about 45,000 names to the ICHEIC list was the product of comprehensive research involving a match between records of all potentially unpaid policies sold during the Nazi era and Jewish victims of the Holocaust available at Yad Vashem.

European insurers uniformly oppose calls for companies to publicly disclose lists of all policies in force during the era of the Nazi Reich. In addition to citing privacy concerns, they argue that compiling and publishing such lists would be costly and would provide little clarity regarding potential Jewish policyholders. They contend that company policy lists contain no information as to a person's religion, and numerous variations in spellings could cause greater confusion and may unnecessarily raise expectations.

Policy Valuation

Another central critique of the ICHEIC process is that it paid out a relatively low proportion of the value of the insurance assets in question. One past House bill on the issue (H.R. 1746, 110th Congress) included a finding that "(12) Experts estimate that the value in 2006 of unpaid life, annuity, endowment, and dowry insurance theft from European Jewry from the Holocaust and its aftermath ranges between $17,000,000,000 and $200,000,000,000."

The estimates referenced, $17 billion to $200 billion, generally came from critics of the ICHEIC process and advocates for Jewish survivors and their heirs.28 The insurance companies involved have produced estimates that are significantly less, in the range of $2 billion to $3 billion. ICHEIC itself commissioned a task force led by Glenn Pomeroy (then Insurance Commissioner of North Dakota) and Philippe Ferras (then Executive Vice-President of AXA Insurance) to assess the value of Holocaust-era insurance markets.29 The Pomeroy-Ferras Report as it is usually known, lays out in great detail various facts and assumptions around the issue of valuation including ranges of estimates for each country in the home currency. It does not itself give a current day number for the value of all unpaid claims although it would be possible to calculate such a value using the ICHEIC valuation calculations applied to individual claims (these guidelines are discussed below).

Despite the seemingly wide range of estimates, between $2 billion and $200 billion, the basic method for the competing calculations is largely the same—estimate the total amount of insurance held by Jews in the relevant parts of Europe prior to World War II, subtract the amounts that have been previously paid on these policies, and adjust this amount for the intervening decades. While the figures for total insurance amounts and the approximate Jewish population are generally accepted, the figures used in most other steps of the calculation are often disputed. These include the specific propensity for the Jewish population to purchase insurance, and the method used to value assets denominated in historical foreign currencies from the 1930s in current U.S. dollars. Unfortunately, there is often little objective evidence upon which to base the choice of what figure to use.

Perhaps the single factor that can have the widest impact on the range of estimates is the method used to translate the values of insurance policies from the 1930s denominated in European currencies to current day U.S. dollars. The first part of this question is, what index does one use to adjust for the intervening decades? The answer to this can change the final value dramatically. At the current day, using the U.S. Consumer Price Index, $1 in 1938 would be worth approximately $18.33; if that $1 from 1938 had been invested in 10-year U.S. Government bonds, it would be worth approximately $70.09; if it had been invested in the S&P 500, $1 in 1938 would be worth approximately $5,096. The corresponding figures for Germany, for example, would be much lower, largely due to the post-war currency reform. One unit of German currency adjusted from 1938 to the current day using German inflation would be multiplied by approximately 8.3; adjusted using German bond returns, the figure would be 15.2; and, using German stock returns, it would be 357.5.30 In general, the ICHEIC process used multipliers based on long-term bond rates, although there were times when the multipliers were apparently arrived at through negotiation between the parties involved.

The second part of the question addresses when one chooses to exchange the policy value from the original currency into U.S. dollars. This is particularly important for German policies since, following World War II, West Germany reformed its currency from Reichsmarks (RM) to Deutsche Marks (DM). This was done at a rate of 10 RM to 1 DM for most currency and 5 RM to 1 DM for long-term financial assets. Thus, if one chooses to change a RM policy into dollars prior to the currency reform, the current day dollar value of that policy would be five or ten times larger than if one chooses to change that policy into dollars after the currency reform. In general, for Germany and Western Europe, values were kept in original currencies until the current day. For Eastern Europe, currencies were converted to dollars in the past.

ICHEIC's method of determining the present day value of individual policies differed according to the country of origin and whether or not the policy specified a particular currency. German policies were paid according to a formula in a general German post-war restitution law that was then adjusted using German long-term bond rates. Offers were made in euros or converted to dollars in the current day. Other Western European policies were generally left in the original currencies, brought forward in time using long-term bond rates in the country of origin. Offers were made in the original currencies. Eastern European policies were first converted into dollars, using 1938 exchange rates that were discounted 30%, and then multiplied by 11.286 to bring the value to the year 2000.31 After 2000, the values were brought forward to the current day using a rate based on long-term bond rates. Policies that specified a currency, such as British pounds or Swiss francs, were generally left in those currencies and then brought to the current day using long-term bond rates. ICHEIC also used minimum valuation thresholds for each individual policy claimant. If the ICHEIC valuation standards resulted in a present-day value that was below a certain minimum value, the actual offer given to the claimant was raised. The minimum values ranged from $500 to $4,000 depending on the country involved, and whether the policy was held by someone who survived the Holocaust or not.32

Litigation of Holocaust-Era Insurance Claims

As mentioned above, a substantial number of litigants filed lawsuits in American courts seeking benefits allegedly owed under Holocaust-era insurance policies,33 leading past Administrations to support ICHEIC as an alternative to resolving Holocaust-era insurance claims through litigation in U.S. state and federal courts.34 As this litigation developed, several states also enacted legislation intended to pressure Holocaust-era insurers to pay unpaid claims.35 California, for instance, enacted the Holocaust Victim Insurance Relief Act of 1999 (HVIRA), which required insurers that sold insurance policies in Europe prior to 1945 to disclose information about those policies to the California Insurance Commissioner.36 As described below, however, the U.S. Supreme Court's 2003 decision in American Insurance Ass'n v. Garamendi,37 along with subsequent state and federal court decisions interpreting Garamendi,38 concluded that the federal government's policy with respect to the resolution of Holocaust-era insurance claims foreclosed this litigation and invalidated these state statutes.

The petitioners in Garamendi—with the support of the United States, which appeared as an amicus curiae39—sought to invalidate HVIRA on the ground that it interfered with the federal government's conduct of foreign relations.40 The Supreme Court, ruling in the petitioners' favor,41 emphasized that the federal executive branch enjoys a primary role in the development of United States foreign policy with respect to the resolution of American nationals' claims against foreign entities.42 The Court observed that whereas the President's policy had been to encourage insurers to volunteer settlement funds rather than subject them to litigation or other coercive sanctions,43 HVIRA embodied a competing policy of compelling insurers to disclose information and pay insureds.44 The Court determined that these two conflicting policies were irreconcilable.45 Because California's disclosure requirement implicated foreign affairs—a field "in which national, not state, interests are overriding"46—the Court concluded that federal foreign policy preempted HVIRA and thereby rendered the reporting requirements unenforceable.47

Notably, however, Garamendi left several significant legal questions unresolved. First, the Justices expressly did not decide whether they would have reached a different result if Congress had enacted a statute authorizing states to enact legislation like HVIRA.48 Nevertheless, the Court's opinion did deem it significant that Congress had never formally disapproved of the President's policy regarding Holocaust insurance claims.49

Secondly, because Garamendi only involved a challenge to HVIRA's informational disclosure requirement, the Supreme Court did not expressly address whether the federal government's foreign policy position also foreclosed litigants from suing insurers directly.50 In its 2010 opinion in In re Assicurazioni Generali, S.P.A., however, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (Second Circuit) concluded that federal policy of encouraging the settlement of claims through ICHEIC likewise precluded litigants from suing insurers to enforce their putative rights under Holocaust-era policies.51 Thus, applying the Supreme Court's decision in Garamendi,52 the Second Circuit affirmed the dismissal of a substantial number of lawsuits seeking compensation under Holocaust-era insurance policies.53

Other courts similarly applied Garamendi to foreclose lawsuits against ICHEIC itself. In Steinberg v. International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims, the plaintiffs, invoking a provision of California's Code of Civil Procedure purporting to authorize California courts to adjudicate Holocaust insurance claims,54 attempted to challenge ICHEIC's claim resolution guidelines in state court.55 The California Court of Appeal ruled that the federal government's policy with respect to Holocaust insurance claims preempted this statutory provision just as it preempted HVIRA.56 The court, citing Garamendi,57 ruled that "[t]he foreign policy of the United States is to favor settlement" of Holocaust-era insurance claims "under ICHEIC's processes. It would undermine this policy if California courts were to subject ICHEIC's established guidelines to regulation under" California law.58 The Steinberg court consequently concluded that the plaintiffs' claims against ICHEIC could not proceed.59

Taken together, Garamendi and the lower court cases applying it appear to have foreclosed many Holocaust survivors and their heirs from obtaining relief through American state and federal courts on the grounds that such litigation interferes with the federal government's conduct of foreign affairs.60 These cases do not necessarily resolve, however, whether Congress could override these judicial opinions by enacting legislation empowering plaintiffs to pursue Holocaust insurance litigation in American courts.61

Congressional Concerns and Proposed Legislation

Since the late 1990s, many Members of Congress have taken a variety of steps seeking to ensure that Holocaust survivors and their heirs receive fair compensation for unpaid insurance policies. A series of hearings before the House Committee on Government Reform between 2001 and 2003 focused specifically on ICHEIC and on proposed legislation intended to create alternative and more effective means for Holocaust survivors and their heirs to resolve unpaid insurance claims. As highlighted above, the House Committee's initial exposure of perceived problems with ICHEIC appears to have played a significant role in spurring subsequent reforms to ICHEIC's claims process. However, the Supreme Court's 2003 Garamendi ruling effectively halted initiatives in several U.S. states that were also supported by some Members of Congress. These initiatives would have required European insurers to disclose policyholder records, and provided Holocaust survivors and their heirs a cause of action to pursue claims substantiated by these records.

ICHEIC's closure, and concern about the well-being of aging Holocaust survivors, spurred congressional interest in resolving outstanding Holocaust-era insurance claims. A number of bills introduced in Congress between 2003 and 2010 would have altered U.S. policy by requiring European insurers to disclose policyholder lists from the Holocaust era and by strengthening survivors' ability to bring cases against European insurers in American courts.62 Several bills introduced in the House and Senate between 2012 and 2017 (including H.R. 762 and S. 258 in the 115th Congress) would have provided a congressionally sanctioned vehicle for the pursuit of claims by individuals who would otherwise have been prevented from doing so by virtue of the Supreme Court's 2003 Garamendi decision. None of these bills was enacted, however, and each was opposed by the Administration, which continued to consider ICHEIC the exclusive vehicle for resolving Holocaust-era insurance claims.

In general, supporters of the aforementioned legislation have argued that both the ICHEIC process and previous agreements between the United States and European governments failed to compensate a significant number of Holocaust survivors and/or their heirs and beneficiaries. Some of those critical of ICHEIC and supportive of the proposed legislation acknowledge that the standards of proof placed on a claimant in an American court of law would likely be far more stringent than those exercised by ICHEIC. However, they argue that in light of ICHEIC's closure, the courts represent one of the few, if not the only, remaining avenues by which to pursue claims. Furthermore, a strong sense of distrust regarding ICHEIC's application of its relaxed standards of proof, and of insurers' thoroughness in searching their records, appears to have increased hope that public disclosure of Holocaust-era records could lead to substantive claims.

Opponents of the such legislation often argued that by effectively reversing past commitments made by the U.S. government—specifically, the granting of legal peace to German companies—the bills could damage future cooperation with European governments on other Holocaust compensation and restitution issues. They add that the legal and historical complexities of substantiating the existence and value of Holocaust-era insurance policies also make it unlikely that claims would be satisfactorily settled in American courts. Critics maintain that it was precisely this fact that drove U.S. insurance regulators, the Claims Conference, and others to back ICHEIC. In addition, given the likelihood of legal challenges from European insurers, some question whether claims could ever be resolved within a reasonable period of time.

Many of those involved in past efforts to resolve claims—including representatives of past U.S. Administrations, the NAIC, European governments, the Claims Conference, and the State of Israel—maintain that ICHEIC, in spite of its faults, offered individuals a better vehicle than any previously available mechanisms. Given that European insurers' participation in ICHEIC was based on the condition that ICHEIC would be an exclusive mechanism to resolve claims, many argue that it could be difficult to obtain additional financial commitments from these companies. Furthermore, some argue that significant obstacles could prevent successful litigation against European insurers. These include difficulties in establishing both the existence and present-day value of policies.

Appendix. ICHEIC Timeline

|

Aug. 199863 |

ICHEIC MOU signed: |

|

Oct. 1999 |

California institutes Holocaust Victims Insurance Act (HVIA) |

|

Feb. 2000 |

ICHEIC launches claims process with initial "pilot" of "fast-track" claims previously gathered by U.S. insurance commissioners. Expects to end claims process by Feb. 2002. |

|

Apr. 2000 |

1st policy-holder list published (18,833 names from archives and ICHEIC research). |

|

June 2000 |

$5 billion German Foundation Agreement includes $350 million German Insurance Industry commitment to ICHEIC. |

|

Nov. 2000 |

Generali commits $100 million to ICHEIC. |

|

Feb. 2001 |

Austrian General Settlement Fund (GSF) includes $25 million commitment to ICHEIC. |

|

Mar.-Apr. 2001 |

About 24,000 additional policyholder names published (none from company lists). |

|

May 2001 |

Press reports 80% of fast-track claims remain unprocessed; 95% of those processed rejected. |

|

Nov. 2001 |

Members criticize ICHEIC during House Committee on Government Reform hearing. Eagleburger testifies and agrees to "policing commission" to oversee company claims handling. |

|

Early 2002 |

Eagleburger appoints "Executive Monitoring Group" (EMG) to investigate ICHEIC claims handling. |

|

May 2002 |

EMG allegedly finds widespread mismanagement in rejection of documented claims. Eagleburger/ICHEIC hire Chief Operating Officer and set-up process to "verify" company claims decisions. In June 2007, ICHEIC reports having verified about 30,000 claims in total. |

|

Sept. 2002 |

House Government Reform Subcommittee on Government Efficiency conducts Hearing on proposed Holocaust Victims Insurance Relief Act (Waxman). |

|

Oct. 2002 |

German Insurance Industry gives previously committed $350 million. |

|

Nov. 2002 |

ICHEIC finalizes valuation guidelines. |

|

Apr. 2003 |

Swiss Insurers agree to $17.5 million to ICHEIC. |

|

Apr. 2003 |

ICHEIC publishes 363,232 policy-holder names from German Insurance Industry. |

|

June 2003 |

Supreme Court rules against California's HVIA (Garamendi). Primary argument that state law interferes with foreign policy decisions of the Executive branch. |

|

Sept. 2003 |

House Committee on Government Reform holds hearing on future of insurance-related bills in light of Garamendi decision. Eagelburger testifies. |

|

Mar. 2004 |

Claims filing deadline. |

|

June 2006 |

Claims decisions finalized. |

|

Mar. 2007 |

ICHEIC closes. |

|

June 2007 |

ICHEIC final report released. |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

This figure represents the present-day value of all payments through the year 2018, as reported by the German Ministry of Finance. German Ministry of Finance, Compensation for National Socialist Injustice, January 27, 2018. https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/EN/Standardartikel/Press_Room/Publications/Brochures/2018-08-15-entschaedigung-ns-unrecht-engl.html |

| 2. |

For more information see CRS Report RL33808, Germany's Relations with Israel: Background and Implications for German Middle East Policy, by Paul Belkin. |

| 3. |

See, for example, Stuart Eizenstat (former U.S. Undersecretary of State and Deputy Treasury Secretary, and lead Clinton Administration negotiator on Holocaust compensation matters), "Imperfect Justice: Looted Assets, Slave Labor, and the Unfinished Business of World War II." New York: Public Affairs. 2003. |

| 4. |

For additional background information on these efforts see Ibid.; John Authers and Richard Wolffe, "The Victim's Fortune: Inside the Epic Battle over the Debts of the Holocaust," New York: Harper Collins. 2002; Michael Bazyler, "Holocaust Justice: The Battle for Restitution in America's Courts." New York: NYU Press. 2003; and documents related to the 1998 Washington Conference on Holocaust-era Assets available at https://fcit.usf.edu/holocaust/resource/assets/index.HTM. |

| 5. |

See Complaint, Cornell v. Assicurazioni Generali, No. 1:97-CV-02262 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 1997). |

| 6. |

With regard to the importance of national government involvement, Eizenstat says, "My bitter experience with the Swiss negotiations, in which the Swiss government refused to be a negotiating partner, taught me a lesson that I never forgot in joining the German, Austrian, and French talks. I would never again risk the prestige of the U.S. government in trying to settle class-action lawsuits against foreign companies, unless their governments were willing to become directly engaged ... Fortunately, Germany, Austria, and France ... recognized that the reputation of their private companies reflected on their nations' reputations." Eizenstat, op. cit., p. 341. |

| 7. |

Ibid. |

| 8. |

An historian at the University of California, Berkeley, Professor Gerald D. Feldman, conducted extensive research into the Nazi seizure of insurance assets. See, for one account, Chapter 6 of his work Allianz and the German Insurance Business, 1933-1945, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001). |

| 9. |

This was the case, for example, with regard to property damage claims from the anti-Jewish riots on Kristallnacht, November 9, 1938 as well as with life insurance policies. |

| 10. |

Statement of Mr. Herbert Hansmeyer, member of the Board of Management of Allianz AG. Washington Conference on Holocaust-era Assets (1998), op. cit., p. 594. |

| 11. |

For a detailed account of Generali's stance on the nationalization issue, see "The Nationalization, Confiscation and Liquidation of Insurance Policies Issued by Generali's Former Offices in Eastern Europe," May 24, 1999. Available from Generali offices, Trieste, Italy. |

| 12. |

Basler subsequently withdrew from ICHEIC. According to German Insurance Association (GDV) representatives, claims against Basler were covered through the Association's participation in ICHEIC. |

| 13. |

For additional background information on ICHEIC, see the ICHEIC, Finding Claimants and Paying Them: The Creation and Workings of the International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims, 2007, at http://www.icheic.org/. |

| 14. |

Such criticism was, for example, expressed by former New York Superintendent of Insurance and ICHEIC appeals arbitrator, Albert Lewis. See Stewart Ain, "Probe 'Phantom Rule,' Says Congressman," The New York Jewish Week, July 6, 2007. |

| 15. |

Some survivor organizations in the United States were reportedly dismayed that the bulk of this humanitarian funding went to assist Holocaust survivors in the former Soviet Union. |

| 16. |

See GDV, Post-ICHEIC Statistics (AVHO), available on GDV website at https://www.en.gdv.de/en/issues/our-news/compensation-of-insurance-policies-of-holocaust-victims-16160. |

| 17. |

United States-Germany: Agreement Concerning The Foundation "Remembrance, Responsibility And The Future," Berlin, July 17, 2000. |

| 18. |

President Clinton's National Security Advisor Samuel Berger summarized the U.S. commitment to give German companies "enduring and all-embracing legal peace" in a June 2000 letter to his German counterpart. See June 16, 2000 letter from U.S. National Security Advisor Samuel Berger to German Foreign Policy and Security Advisor Michael Steiner; and "U.S.-Germany Agreement on the German Foundation." Both available via the State Department digital archive, https://www.state.gov/u-s-department-of-state-archive-websites/. See also Am. Ins. Ass'n v. Garamendi, 539 U.S. 396, 406 (2003) ("Though unwilling to guarantee that its foreign policy interests would 'in themselves provide an independent legal basis for dismissal,' that being an issue for the courts, the Government agreed to tell courts 'that U.S. policy interests favor dismissal on any valid legal ground.'"). |

| 19. |

See infra "Litigation of Holocaust-Era Insurance Claims." |

| 20. |

Between 2001 and 2003, the House Committee on Government Reform held three hearings on ICHEIC and Holocaust insurance issues. For information on the hearings held and related legislative proposals see https://www.congress.gov/. |

| 21. |

Eizenstat captures much of the criticism surrounding ICHEIC in his characterization of ICHEIC Chairman Eagleburger's own complaints about the ICHEIC process as follows: "there was incessant internal bickering over every issue—how to value policies from prewar days, which lists of policyholders should be opened, the costs to be borne in processing claims, the ICHEIC claims process itself. Eagleburger had difficulty getting the companies, particularly Allianz, to fulfill the terms of the MOU ... And ICHEIC's administrative failings led to few claims paid and large costs." Eizenstat, op. cit., p. 267. |

| 22. |

See, for example, Sidney Zabludoff, "The International Commission of Holocaust-Era Insurance Claims: Excellent Concept but Inept Implementation," Jewish Political Studies Review, Spring 2005. |

| 23. |

"The Status of Insurance Restitution for Holocaust Victims and their Heirs," Hearing before the Committee on Government Reform, November 8, 2001. |

| 24. |

In June 2007, ICHEIC reported having "verified" 30,000 total claims. ICHEIC Final Report, op. cit. |

| 25. |

See Association of Jewish Refugees website https://ajr.org.uk/, and Zabludoff, op. cit. |

| 26. |

ICHEIC's list of potential policyholders is no longer available on the ICHEIC website, but can be accessed through Yad Vashem's website at http://www1.yadvashem.org/pheip/. |

| 27. |

Interviews of German government and GDV officials, November 2007-January 2008. |

| 28. |

The $17 billion figures appears to come from the previously cited work of Mr. Sydney Zabludoff. The $200 billion appears to come from the work of Professor Joseph Belth in The Insurance Forum, "Life Insurance and the Holocaust," Vol. 25, No 9, p. 81, September 1998. |

| 29. |

"Report to Lawrence Eagleburger, Chairman, by the Task Force Co-Chaired by Glenn Pomeroy and Philippe Ferras On The Estimation of Unpaid Holocaust Era Insurance Claims in Germany, Western and Eastern Europe," available at http://www.icheic.org/pdf/Pomeroy-Ferras%20Report.pdf. |

| 30. |

The stock and bond yield calculations assume reinvestment of interest and dividends and do not include the effect of taxes. Calculations by CRS using data series from http://www.globalfinancialdata.com and https://finance.yahoo.com/. For inflation and bond yields, the series used for the entire time periods were "United States BLS Consumer Price Index," "Germany Consumer Price Index," "USA 10 year Government Bond Total Return Index ," "Germany 10 year Government Bond Return Index," from For stock returns, the series used were "S&P 500® Total Return Index" (1938-2008), and "Germany CDAX Total Return Index" (1938-2008) and S&P Total Return Index and DAX Performance Index (2008-2019). |

| 31. |

The 30% discount on the exchange rates and the multiplier value of 11.286 were the result of negotiations by the ICHEIC participants and apparently included because of the post-war nationalization of Eastern European insurance companies. |

| 32. |

See "Guide to Valuation Procedures: Edition Dated 22-10-02," available at http://www.icheic.org/pdf/ICHEIC_VG.pdf. |

| 33. |

See, e.g., In re Assicurazioni Generali S.P.A. Holocaust Ins. Litig., 340 F. Supp. 2d 494, 496-97 n.1 (S.D.N.Y. 2004) (describing twenty such lawsuits). |

| 34. |

See supra "Administration Policy on ICHEIC." |

| 35. |

See, e.g., Cal. Ins. Code §§13800-13807 (West 1999) (California Holocaust Victim Insurance Relief Act of 1999); Cal. Civ. Proc. Code §354.5 (West 1999); Fla. Stat. §626.9543 (1999) (Florida Holocaust Victims Insurance Act); N.Y. Ins. Law §§2701-2711 (1998) (New York Holocaust Victims Insurance Act of 1998). See also, e.g., Am. Ins. Ass'n v. Garamendi, 539 U.S. 396, 408 (2003) (explaining that the State of California conducted an "enquiry into the issue of unpaid claims under Nazi-era insurance policies" and ultimately enacted "state legislation designed to force payment by defaulting insurers"). |

| 36. |

Cal. Ins. Code §13804 (West 1999). |

| 37. |

539 U.S. at 401. |

| 38. |

See, e.g., In re Assicurazioni Generali, S.P.A., 592 F.3d 113, 115 (2d Cir. 2010); Steinberg v. Int'l Comm'n on Holocaust Era Ins. Claims, 34 Cal. Rptr. 3d 944, 945 (Cal. Ct. App. 2005). |

| 39. |

539 U.S. at 413. An amicus curiae is an entity that is not a formal party to a particular lawsuit, yet nonetheless files a brief in the case in support of a particular legal position. See Amicus Curiae, Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). |

| 40. |

539 U.S. at 401. |

| 41. |

See id. |

| 42. |

See id. at 415 ("[O]ur cases have recognized that the President has authority to make 'executive agreements' with other countries, requiring no ratification by the Senate or approval by Congress, this power having been exercised since the early years of the Republic ... Making executive agreements to settle claims of American nationals against foreign governments is a particularly longstanding practice ... [that] has received congressional acquiescence throughout its history.... The executive agreements at issue here [are] against corporations, not the foreign governments. But the distinction does not matter."). |

| 43. |

Id. at 421 ("[T]he consistent Presidential foreign policy has been to encourage European governments and companies to volunteer settlement funds in preference to litigation or coercive sanctions."). |

| 44. |

Id. at 423 ("California has taken a different tack of providing regulatory sanctions to compel disclosure and payment, supplemented by a new cause of action for Holocaust survivors if the other sanctions should fail."). |

| 45. |

See id. at 425 ("The express federal policy and the clear conflict raised by the state statute are alone enough to require state law to yield."). |

| 46. |

Id. at 421. |

| 47. |

Id. at 401. For further analysis of the federal preemption of state law, see CRS Report R45825, Federal Preemption: A Legal Primer, by Jay B. Sykes and Nicole Vanatko. Notably, prior to Garamendi, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit had also struck down a similar statute enacted by the State of Florida, albeit on slightly different legal grounds. See Gerling Glob. Reinsurance Corp. of Am. v. Gallagher, 267 F.3d 1228, 1229 (11th Cir. 2001). |

| 48. |

See 539 U.S. at 427 ("The State's remaining submission is that even if HVIRA does interfere with Executive Branch foreign policy, Congress authorized state law of this sort [when enacting certain federal statutes]. There is, however, no need to consider the possible significance for preemption doctrine of tension between an Act of Congress and Presidential foreign policy, ... for neither statute does the job the commissioner ascribes to it.") (internal citations omitted). |

| 49. |

See id. at 429 ("[I]t is worth noting that Congress has done nothing to express disapproval of the President's policy. Legislation along the lines of HVIRA has been introduced in Congress repeatedly, but none of the bills has come close to making it into law."). See also id. at 427 ("[D]issatisfaction should be addressed to the President or, perhaps, Congress."). |

| 50. |

In re Assicurazioni Generali, S.P.A., 592 F.3d 113, 118 (2d Cir. 2010) ("Garamendi involved only disclosure requirements."). |

| 51. |

Id. ("[S]uch law suits are directly in conflict with the Government's policy that claims should be resolved exclusively through the ICHEIC.") (emphasis omitted). |

| 52. |

See id. at 115 ("Garamendi controls this case.... "). |

| 53. |

See id. Notably, however, some of the other plaintiffs settled with the insurer before the Second Circuit rendered its decision. See id. at 117. See also Rubin v. Assicurazioni Generali S.P.A., 290 F. App'x 376, 376-78 (2d Cir. 2008) (affirming order approving settlement agreement with Holocaust-era insurer). Notwithstanding the foregoing, the Second Circuit did afford a single plaintiff an opportunity to file a new complaint in a federal district court to avoid dismissal. See 592 F.3d at 121 ("We instruct the district court to permit David to replead if ... he is able to plead a claim that falls outside the scope of the ICHEIC."). As far as the district court's docket reveals, however, that plaintiff ultimately did not do so. See Docket, David v. Assicurazioni, No. 1:00-CV-09416 (S.D.N.Y.). |

| 54. |

Cal. Civ. Proc. Code §354.5 (West 1999). See also Steinberg v. Int'l Comm'n on Holocaust Era Ins. Claims, 34 Cal. Rptr. 3d 944, 949 (Cal. Ct. App. 2005) (explaining that Cal. Civ. Proc. Code §354.5 purported to "provide[] California superior courts with jurisdiction over lawsuits for unpaid Holocaust era insurance claims"). |

| 55. |

34 Cal. Rptr. 3d at 945. |

| 56. |

Id. ("We conclude that section 354.5, which provides that California residents may bring claims arising out of Holocaust era insurance policies in California courts, is preempted by the foreign policy of the United States."). |

| 57. |

See id. at 948 ("[T]he Garamendi opinion dictates the resolution of this appeal ... "). |

| 58. |

Id. at 945. |

| 59. |

Id. at 953 ("We therefore conclude section 354.5 is preempted, and the plaintiffs' action cannot proceed."). |

| 60. |

See, e.g., In re Assicurazioni Generali S.P.A. Holocaust Ins. Litig., 340 F. Supp. 2d 494, 496-97 n.1 (S.D.N.Y. 2004) (listing cases dismissed as a result of the Second Circuit's opinion affirming the district court's dismissal order). |

| 61. |

See Am. Ins. Ass'n v. Garamendi, 539 U.S. 396, 427 (2003) (declining to "consider the possible significance for preemption doctrine of tension between an Act of Congress and Presidential foreign policy"). |

| 62. |

See, for example: H.R. 1210, the Holocaust Victims Insurance Relief Act of 2003, introduced by Rep. Henry Waxman on March 11, 2003; H.R. 1905, the Comprehensive Holocaust Accountability in Insurance Measure, introduced by Rep. Mark Foley on May 1, 2003; S. 972, the Comprehensive Holocaust Accountability in Insurance Act, introduced by Sen. Norm Coleman on May 1, 2003; H.R. 3129, the Holocaust Victims Insurance Act, introduced by Rep. Adam Schiff on September 17, 2003; H.R. 1746, the Holocaust Insurance Accountability Act of 2008, introduced by Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen on March 28, 2007; H.R. 4596, the Holocaust Insurance Accountability Act of 2010, introduced by Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen on February 4, 2010; and S. 4033, the Restoration of Legal Rights for Claimants under Holocaust-Era Insurance Policies Act of 2010, introduced by Sen. Arlen Specter on December 15, 2010. |

| 63. |

Information from following sources: ICHEIC, Finding Claimants and Paying Them: The Creation and Workings of the International Commission on Holocaust Era Insurance Claims, 2007; ICHEIC Timeline from ICHEIC website (no longer online); Michael J. Bazyler, "Holocaust Justice," New York: New York University Press, 2003. |