Debt-for-Nature Initiatives and the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (TFCA): Status and Implementation

In the late 1980s, extensive foreign debt and degraded natural resources in developing nations led to the creation of debt-for-nature initiatives that reduced debt obligations, allowed for debt repayments in local currency as opposed to hard currency, and generated funds for the environment. These initiatives, called debt-for-nature swaps typically involved restructuring, reducing, or buying a portion of a developing country’s outstanding debt, with a percentage of proceeds (in local currency) being used to support conservation programs within the debtor country. Most early transactions involved debt owed to commercial banks and were administered by nongovernmental conservation organizations and referred to as three-party transactions. Other debt-for-nature initiatives involved official (public) debt and were administered by creditor governments directly with debtor governments (termed bilateral transactions).

In the early 1990s, the United States initiated a program called the Enterprise for the Americas Initiative (EAI), which involved debt-for-nature transactions. The United States restructured, and in one case sold, debt equivalent to a face value of over $1 billion owed by Latin American countries; these transactions were authorized by Congress as part of the EAI, which broadened the scope of debt transactions to include a number of social goals. Nearly $177 million in local currency for environmental, natural resource, health protection, and child development projects within debtor countries was generated from these transactions.

The model for debt-for-nature transactions, outlined in the EAI, was used in the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (TFCA; P.L. 105-214; 22 U.S.C. 2431) to include countries around the world with tropical forests. Under this program, debt can be restructured in eligible countries and funds generated from the transactions are used to support programs to conserve tropical forests within the debtor country. TFCA authorizes the use of debt swaps, debt restructuring, and debt buybacks to generate conservation funds. Under these agreements, the existing debt agreement is canceled and a new one is created; a Tropical Forest Agreement is created and interest payments for the principal of the loan are deposited in local currency equivalents in a Tropical Forest Fund; and the money in the fund is given in the form of grants to local conservation groups or the debtor government to conduct conservation activities for tropical forests.

Eligible conservation projects include (1) the establishment, maintenance, and restoration of parks, protected reserves, and natural areas, and the plant and animal life within them; (2) training programs to increase the capacity of personnel to manage parks; (3) development and support for communities residing near or within tropical forests; (4) development of sustainable ecosystem and land management systems; and (5) research to identify the medicinal uses of tropical forest plants and their products. Since 1998, $233.4 million has been used under TFCA to restructure loan agreements in 14 countries (20 transactions), and over $339.4 million will be generated for tropical forest conservation at the conclusion of these agreements. TFCA was authorized to receive appropriations through FY2007, but no funds have been appropriated for the program since FY2014. TFCA is being considered for reauthorization in the 115th Congress in S. 1023. This bill would expand the purpose of TFCA to include coral reefs and authorize $20 million in appropriations annually from FY2018 to FY2021, among other things.

Debt-for-nature transactions generally are viewed as a success by conservation organizations and debtor governments because of the funds generated for conservation efforts. Debt-for-nature transactions under TFCA have stopped in recent years. Some observers suggest that this is due to lack of appropriations to support TFCA and competing debt-relief programs, such as the Highly Indebted Poor Countries Initiative.

Debt-for-Nature Initiatives and the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (TFCA): Status and Implementation

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background Information

- Authority for Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

- Debt-for-Nature Initiatives and Their Mechanisms

- Three-Party Transactions

- Bilateral and Multilateral Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

- U.S. Bilateral Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

- Tropical Forest Conservation Act

- Issues for Congress

- Rationale for and Criticism of Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

- Decline of Debt-for-Nature Transactions

- Effectiveness of Debt-for-Nature Transactions

- Appropriations

- Future Directions

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Selected Countries Participating in Three-Party Debt-for-Nature Transactions, 1987-Present (excluding TFCA transactions)

- Table 2. Countries Other than the United States Participating in Bilateral and Multilateral Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

- Table 3. U.S. Bilateral Debt-for-Nature Transactions Under EAI

- Table 4. U.S. Bilateral Debt-for-Nature Transactions Under TFCA

- Table 5. Appropriations for Debt-for-Nature Transactions Under TFCA

Summary

In the late 1980s, extensive foreign debt and degraded natural resources in developing nations led to the creation of debt-for-nature initiatives that reduced debt obligations, allowed for debt repayments in local currency as opposed to hard currency, and generated funds for the environment. These initiatives, called debt-for-nature swaps typically involved restructuring, reducing, or buying a portion of a developing country's outstanding debt, with a percentage of proceeds (in local currency) being used to support conservation programs within the debtor country. Most early transactions involved debt owed to commercial banks and were administered by nongovernmental conservation organizations and referred to as three-party transactions. Other debt-for-nature initiatives involved official (public) debt and were administered by creditor governments directly with debtor governments (termed bilateral transactions).

In the early 1990s, the United States initiated a program called the Enterprise for the Americas Initiative (EAI), which involved debt-for-nature transactions. The United States restructured, and in one case sold, debt equivalent to a face value of over $1 billion owed by Latin American countries; these transactions were authorized by Congress as part of the EAI, which broadened the scope of debt transactions to include a number of social goals. Nearly $177 million in local currency for environmental, natural resource, health protection, and child development projects within debtor countries was generated from these transactions.

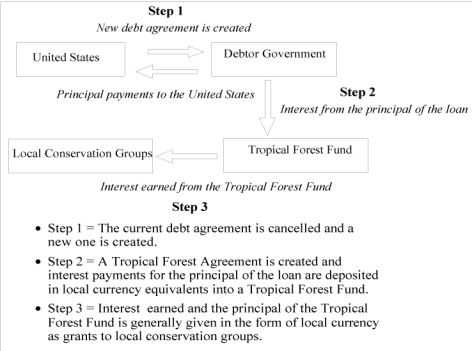

The model for debt-for-nature transactions, outlined in the EAI, was used in the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (TFCA; P.L. 105-214; 22 U.S.C. 2431) to include countries around the world with tropical forests. Under this program, debt can be restructured in eligible countries and funds generated from the transactions are used to support programs to conserve tropical forests within the debtor country. TFCA authorizes the use of debt swaps, debt restructuring, and debt buybacks to generate conservation funds. Under these agreements, the existing debt agreement is canceled and a new one is created; a Tropical Forest Agreement is created and interest payments for the principal of the loan are deposited in local currency equivalents in a Tropical Forest Fund; and the money in the fund is given in the form of grants to local conservation groups or the debtor government to conduct conservation activities for tropical forests.

Eligible conservation projects include (1) the establishment, maintenance, and restoration of parks, protected reserves, and natural areas, and the plant and animal life within them; (2) training programs to increase the capacity of personnel to manage parks; (3) development and support for communities residing near or within tropical forests; (4) development of sustainable ecosystem and land management systems; and (5) research to identify the medicinal uses of tropical forest plants and their products. Since 1998, $233.4 million has been used under TFCA to restructure loan agreements in 14 countries (20 transactions), and over $339.4 million will be generated for tropical forest conservation at the conclusion of these agreements. TFCA was authorized to receive appropriations through FY2007, but no funds have been appropriated for the program since FY2014. TFCA is being considered for reauthorization in the 115th Congress in S. 1023. This bill would expand the purpose of TFCA to include coral reefs and authorize $20 million in appropriations annually from FY2018 to FY2021, among other things.

Debt-for-nature transactions generally are viewed as a success by conservation organizations and debtor governments because of the funds generated for conservation efforts. Debt-for-nature transactions under TFCA have stopped in recent years. Some observers suggest that this is due to lack of appropriations to support TFCA and competing debt-relief programs, such as the Highly Indebted Poor Countries Initiative.

Background Information

Debt-for-nature initiatives were conceived to address the rapid loss of resources and biodiversity in developing countries that were heavily indebted to foreign creditors. Conservationists had noted that the pressure to pay off foreign debts in hard currency was leading to increased levels of natural resource exports (i.e., timber, cattle, minerals, and agricultural products) at the expense of the environment. In many cases, indebted developing countries had difficulty meeting their hard currency debt obligations and defaulted. Reducing foreign debt and allowing for portions of it to be paid with local currency while increasing funds for the environment was thought to improve environmental conditions in developing countries and had the advantage of relieving the debtor country's difficulties in procuring sufficient hard currency to pay off its debts.1 Money generated from debt-for-nature transactions has been used to fund a variety of projects, ranging from national park protection in Costa Rica to supporting ecotourism in Ghana and conserving tropical forests in Bangladesh.

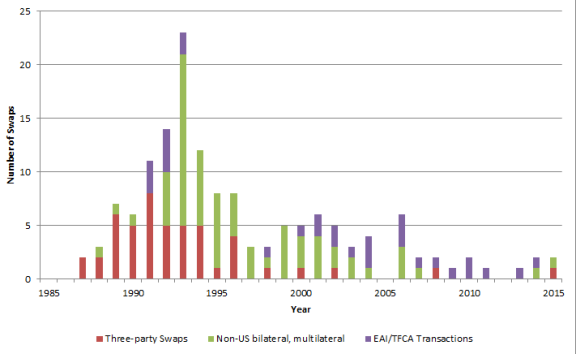

Since 1993, there has been a declining trend in the number of debt-for-nature transactions involving official (public) and private funds. Accounting changes requiring new appropriations to support official (public) debt transactions in creditor countries such as the United States, and a higher price of commercial debt on secondary markets, are two reasons suggested for the decline of debt-for-nature transactions. While Congress has periodically authorized U.S. participation in three-party debt-for-nature transactions and has supported two bilateral debt-for-nature initiatives, appropriations to support these types of efforts have generally diminished over the years.

Authority for Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

Early debt-for-nature legislation concentrated on understanding and promoting third-party debt-for-nature transactions (see Appendix for legislation summaries and United States Code citations). Congress in 1989 directed the Secretary of the Treasury to ask the U.S. Executive Director of the World Bank to develop a pilot debt-for-nature program and other ways of reducing debt owed by foreign countries while generating funds for the environment. A subsequent law, the International Development and Finance Act of 1989, authorized the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to make grants to nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to purchase debt in three-party transactions. Official (public) P.L. 480 debt owed to the United States by eligible Latin American countries was authorized to be reduced by the 1990 farm bill (P.L. 101-624; 7 U.S.C. 1738b). The 102nd Congress authorized debt reduction for foreign assistance loans made by USAID (P.L. 102-549; 22 U.S.C. 2430 and 2421), the Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im Bank; P.L. 102-429; 12 U.S.C. 635i-6), and the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC; P.L. 102-549; 22 U.S.C. 2430 and 2421). Together, the P.L. 480, USAID, Ex-Im, and CCC debt-reduction authorizations were undertaken as part of President George H. W. Bush's Enterprise for the Americas Initiative. In 1996, USAID was further authorized by Congress to conduct swaps, buybacks, and cancellations of debt owed to the United States by eligible Latin American and Caribbean countries (P.L. 104-107). In 1998, the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (TFCA; P.L. 105-214; 22 U.S.C. 2431) was passed, allowing debt swaps, buybacks, and restructuring to generate funds for tropical forest conservation worldwide. Funding for the TFCA was reauthorized by Congress in 2004 (P.L. 108-323). In the 115th Congress, S. 1023 would authorize appropriations for the TFCA of $20.0 million annually from FY2018 to FY2021. The bill also would expand the TFCA to include coral reefs and coral reef ecosystems.2 Further, the bill would allow concessional debt incurred before the date of enactment of the bill to be eligible for debt-for-nature transactions. Under current law, eligible concessional debt must be incurred before 1998.

Debt-for-Nature Initiatives and Their Mechanisms

Three-Party Transactions

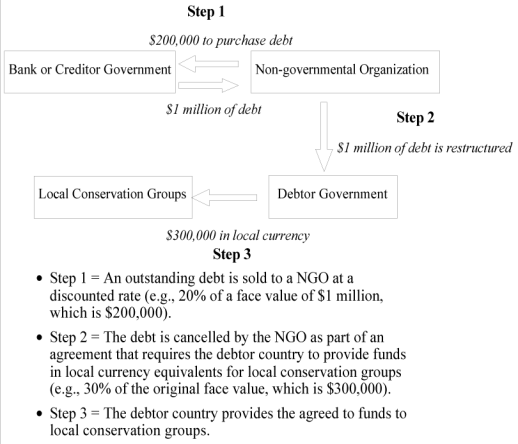

Three-party debt-for-nature transactions, involving nongovernmental organizations such as The Nature Conservancy and Conservation International, were the first debt-for-nature agreements to be formed. In a three-party swap, a conservation group purchases a hard currency debt owed to commercial banks on the secondary market or in some cases a public (official) debt owed to a creditor government at a discounted rate compared to the face value of the debt, and then renegotiates the debt obligation with the debtor country.3 The debt is generally sold back to the debtor country for more than it was purchased for by the NGO, yet less than what it was on the secondary market. The proceeds generated from the renegotiated debt, to be repaid in local currency, are typically put into a fund that often allocates grants to local environmental organizations for conservation projects (see Figure 1). In these cases, the fund is administered by the conservation organization, representatives from local environmental groups, and the debtor government. Money to buy the debt initially may come from the nongovernmental organization, governments, banks, or other private organizations.

|

Figure 1. An Illustrative Example of a Three-Party Debt-for-Nature Swap Agreement |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

In 1989, Congress authorized the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to provide assistance to nongovernmental organizations to purchase the commercial debt of foreign countries as part of debt-for-nature agreements (P.L. 101-240; 22 U.S.C. 2282-2286). Several nongovernmental organizations participated in debt-for-nature transactions with financial assistance from USAID; however, specific information on funds given by USAID to support three-party debt-for-nature transactions was not available.

While debt initiatives conducted with three-party transactions are numerous, they have resulted in less reduction in total debt than the debts swapped under bilateral agreements (government-to-government), and slightly less in conservation funds generated. In total, approximately $200 million in debt (face value) has been reduced, restructured, or swapped using this mechanism, generating approximately $167 million in local currency for conservation purposes (see Table 1).

Table 1. Selected Countries Participating in Three-Party Debt-for-Nature Transactions, 1987-Present (excluding TFCA transactions)

(in thousands of dollars)

|

Country |

Year |

Purchaser |

Cost |

Face Value of Debt |

Conservation Funds Generated |

|

Bolivia |

1993 |

TNC/WWF |

$0 |

$11,500 |

$2,860 |

|

1987 |

CI |

100 |

650 |

250 |

|

|

Total Bolivia |

100 |

12,150 |

3,110 |

||

|

Brazil |

1992 |

TNC |

748 |

2,200 |

2,200 |

|

Costa Rica |

1991 |

RA/MCL/ |

360 |

600 |

540 |

|

1990 |

SW/WWF/ |

1,953 |

10,574 |

9,603 |

|

|

1989 |

TNC |

784 |

5,600 |

1,680 |

|

|

1989 |

Sweden |

3,500 |

24,500 |

17,100 |

|

|

1988 |

Holland |

5,000 |

33,000 |

9,900 |

|

|

1988 |

NPF |

918 |

5,400 |

4,050 |

|

|

Total Costa Rica |

12,515 |

79,674 |

42,873 |

||

|

Dominican Republic |

1990 |

PRCT/TNC |

116 |

582 |

582 |

|

Ecuador |

1992 |

Japan |

NA |

NA |

1,000 |

|

1989 |

WWF/FN |

640 |

5,400 |

5,400 |

|

|

1987 |

WWF |

354 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

|

|

Total Ecuador |

994 |

6,400 |

7,400 |

||

|

Ghana |

2000 |

CI |

80 |

100 |

90 |

|

1991 |

CI/SI |

250 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

|

|

Total Ghana |

330 |

1,100 |

1,090 |

||

|

Guatemala |

1992 |

CI/USAID |

1,200 |

1,334 |

1,334 |

|

1991 |

TNC |

75 |

100 |

90 |

|

|

Total Guatemala |

1,275 |

1,434 |

1,424 |

||

|

Jamaica |

1991 |

TNC/USAID/ |

300 |

437 |

437 |

|

Madagascar |

2008 |

WWF/France |

n/a |

n/a |

20,000 |

|

1996 |

WWF/Netherlands Development Corporation |

n/a |

2,000 |

1,500 |

|

|

1994 |

WWF/JPM |

0 |

1,341 |

1,072 |

|

|

1994 |

CI |

50 |

200 |

160 |

|

|

1993 |

WWF |

909 |

1,868 |

1,868 |

|

|

1993 |

CI |

1,500 |

3,200 |

3,200 |

|

|

1991 |

CI/UNDP |

59 |

118 |

119 |

|

|

1990 |

WWF |

446 |

919 |

919 |

|

|

1989 |

WWF/USAID |

950 |

2,111 |

2,111 |

|

|

Total Madagascar |

3,914 |

11,757 |

30,949 |

||

|

Mexico |

1998 |

CI |

256 |

550 |

318 |

|

1996 |

CI |

192 |

391 |

254 |

|

|

1996 |

CI |

327 |

496 |

443 |

|

|

1996 |

CI |

440 |

671 |

561 |

|

|

1995 |

CI/USAID |

246 |

488 |

337 |

|

|

1994 |

CI |

399 |

480 |

480 |

|

|

1994 |

CI |

236 |

280 |

280 |

|

|

1994 |

CI |

248 |

290 |

290 |

|

|

1993 |

CI |

208 |

252 |

252 |

|

|

1992 |

CI/USAID |

355 |

441 |

441 |

|

|

1991 |

CI |

0 |

250 |

250 |

|

|

1991 |

CI |

183 |

250 |

250 |

|

|

Total Mexico |

3,092 |

4,838 |

4,155 |

||

|

Nigeria |

1991 |

NCF |

65 |

150 |

93 |

|

Peru |

1993 |

WWF |

n/a |

2,860 |

1,573 |

|

2002 |

WWF, CI, TNC, U.S. |

5,500 |

14,000 |

10,600 |

|

|

Total Peru |

5,500 |

16,860 |

12,173 |

||

|

Philippines |

1993 |

WWF |

13,000 |

19,000 |

17,100 |

|

1992 |

WWF/USAID |

5,000 |

10,000 |

9,000 |

|

|

1990 |

WWF/USAID |

439 |

900 |

900 |

|

|

1989 |

WWF |

200 |

390 |

390 |

|

|

Total Philippines |

18,639 |

30,290 |

29,090 |

||

|

Poland |

1990 |

WWF |

11 |

50 |

50 |

|

Seychelles |

2015 |

TNC/PC |

n/a |

30,000 |

28,500 |

|

Zambia |

1989 |

WWF |

454 |

2,270 |

2,500 |

Sources: Several sources, including M. Moye, Commercial Debt-for-Nature Swaps: Summary Table (Washington, DC: World Wildlife Fund, 2003); M. Guerin-McManaus, Ten Years of Debt for Nature Swaps 1987-1997 (Washington, DC: Conservation International, 2000); World Bank, World Debt Tables, 1996 (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 1996); and press releases describing various debt-for-nature transactions.

Notes: A cost of $0 indicates that funds were written off by the bank to restructure the debt.

Funds generated may be cash or bonds. Figures given do not include interest earned over the life of the bonds. Full titles of abbreviations are given below. Grand total given is an estimate since some figures were not available. n/a = not available.

CABEI = Central American Bank for Economic Integration

CI = Conservation International

FN = Fundacion Natura

JPM = J. P. Morgan Chase and Co.

MBG = Missouri Botanical Garden

MCL = Monteverde Conservation League

NCF = Nigerian Conservation Foundation

NPF = National Parks Fdn. of Costa Rica

PC = Paris Club

PRCT = Puerto Rican Conservation Trust

RA = Rainforest Alliance

SI = Smithsonian Institution

TNC = The Nature Conservancy

UNDP = United Nations Development Prog.

U.S. = U.S. federal government

USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development

WWF = World Wildlife Fund

Bilateral and Multilateral Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

Bilateral debt transactions are conducted with official (public) funds directly between the creditor and debtor governments. The creditor government determines the criteria for eligibility, which usually involve the existence of certain financial and political conditions in the debtor country. Debt agreements are usually cancelled and then restructured to extend payback periods, or in some cases, debt is bought back by the debtor country for a discounted price. Money for the environment can be generated through interest payments from the debtor country if the debt is restructured, or from a percentage of the buyback price. Multilateral debt-for-nature agreements have also been conducted between more than one creditor country and a debtor country (see Table 2).

Table 2. Countries Other than the United States Participating in Bilateral and Multilateral Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

(in thousands of dollars, except where noted)

|

Creditor |

Debtor Country |

Year |

Face Value of Debt Treated |

Conservation Funds Generated |

|

Canada |

Columbia |

1993 |

$12,000 |

$12,000 |

|

El Salvador |

1993 |

7,500 |

6,000 |

|

|

Honduras |

1993 |

24,900 |

12,450 |

|

|

Nicaragua |

1993 |

13,600 |

2,700 |

|

|

Peru |

1994 |

11,250 |

3,800 |

|

|

Belgium |

Bolivia |

1992 |

13,000 |

n/a |

|

Finland |

Poland |

1990 |

17,000 |

17,000 |

|

Peru |

1995 |

18,900 |

8,100 |

|

|

France |

Egypt |

1992 |

n/a |

11,600 |

|

Philippines |

1992 |

n/a |

4,000 |

|

|

Poland |

1993 |

66,000 |

66,000 |

|

|

Cameroon |

2006 |

n/a |

25,000 |

|

|

Mozambique |

2015 |

17,500 (in euros) |

2,000 (in euros) |

|

|

Germany |

Peru |

1994 |

16,079 |

6,100 |

|

Jordan |

1995 |

13,400 |

6,700 |

|

|

Jordan |

1995 |

22,700 |

11,300 |

|

|

Philippines |

1996 |

5,800 |

1,800 |

|

|

Vietnam |

1996 |

18,200 |

5,400 |

|

|

Bolivia |

1997 |

3,700 |

1,150 |

|

|

Honduras |

1999 |

1.068 |

534 |

|

|

Peru |

1999 |

5,140 |

2,060 |

|

|

Vietnam |

1999 |

16,400 |

5,000 |

|

|

Jordan |

2000 |

43,600 |

21,800 |

|

|

Bolivia |

2000 |

15,800 |

3,200 |

|

|

Jordan |

2001 |

11,300 |

5,700 |

|

|

Vietnam |

2001 |

7,000 |

n/a |

|

|

Syria |

2001 |

31,700 |

15,900 |

|

|

Ecuador |

2002 |

9,500 |

3,081 |

|

|

Ecuador |

2002 |

10,200 |

3,235 |

|

|

Madagascar |

2003 |

25,092 |

14,843 |

|

|

Indonesia |

2003 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

Indonesia |

2004 |

29,250 |

n/a |

|

|

Indonesia |

2006 |

13.7 (in euros) |

6.3 (in euros) |

|

|

Indonesia |

2006 |

13.7 (in euros) |

6.3 (in euros) |

|

|

Indonesia |

2007 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

Mozambique |

2014 |

n/a |

10,000 (in euros) |

|

|

Holland |

Peru |

1996 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Costa Rica |

1996 |

14,100 |

14,100 |

|

|

Costa Rica |

1988 |

33,000 |

9,900 |

|

|

Italy |

Poland |

1998 |

32,000 |

32,000 |

|

Egypt |

2001 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

Norway |

Egypt |

1993 |

17,300 |

n/a |

|

Egypt |

1993 |

6,200 |

n/a |

|

|

Nigeria |

1993 |

10,200 |

n/a |

|

|

Poland |

2000 |

27,000 |

27,000 |

|

|

Spain |

Costa Rica |

1999 |

5,222 |

2,180 |

|

Sweden |

Costa Rica |

1989 |

24,500 |

17,100 |

|

Tunisia |

1992 |

1,100 |

1,100 |

|

|

Tunisia |

1993 |

520 |

520 |

|

|

Bolivia |

1993 |

35,400 |

3,900 |

|

|

Poland |

1997 & 1999 |

13,000 |

13,000 |

|

|

Switzerland |

Peru |

1992 |

130,800 |

32,600 |

|

Tanzania |

1993 |

22,200 |

3,300 |

|

|

Bolivia |

1993 |

35,400 |

1,365 |

|

|

Poland |

1993 |

48,000 |

48,000 |

|

|

Honduras |

1993 &1997 |

42,030 |

8,430 |

|

|

Ecuador |

1994 |

46,300 |

4,524 |

|

|

Bulgaria |

1995 |

16,700 |

16,200 |

|

|

Egypt |

1995 |

23,000 |

18,000 |

|

|

Guinea Bissau |

1995 |

8,400 |

400 |

|

|

Philippines |

1995 |

16,100 |

16,100 |

|

|

U.K. |

Nigeria |

1993 |

7,300 |

n/a |

|

Tanzania |

1993 |

15,400 |

15,400 |

Sources: Various sources including R. Curtis, "Bilateral Debt Conversions for the Environment, Peru: An Evolving Case Study," IUCN World Conservation Congress, Montreal (1996), and press releases describing various debt-for-nature transactions.

Note: n/a = information not available.

U.S. Bilateral Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

The model for bilateral debt-for-nature agreements conducted by the United States was first defined in 1990 by the Enterprise for the Americas Initiative (EAI; Title 15, Section 1512 of the Food, Agriculture Conservation and Trade Act of 1990, "1990 farm bill," P.L. 101-624; 7 U.S.C. 1738) and has since been expanded numerous times (see Appendix). It was last amended by the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (TFCA) in 1998 (P.L. 105-214; 22 U.S.C. 2431).

|

Figure 2. An Example of a Bilateral Debt-for-Nature Transaction Modeled After the TFCA |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

The EAI legislation authorizes the sale, reduction, cancellation, and country buyback of eligible debt of Latin American and Caribbean countries that meet certain criteria. The debt authorized to be treated include the following types:

- P.L. 480 debt4 (P.L. 101-624; 7 U.S.C. 1738m, p-r, etc.)

- AID debt5 (P.L. 102-549; 22 U.S.C. 2430 and 2421)

- CCC debt6 (P.L. 102-549; 22 U.S.C. 2430 and 2421)

- Exim debt7 (P.L. 102-429; 12 U.S.C. 635i-6)8

Debtor countries must meet certain political and macroeconomic criteria in order to be eligible. Eligible countries are required to (1) have a democratically elected government, (2) not support terrorism, (3) not fail to cooperate with the United States on drug control, and (4) not engage in gross violations of human rights. From an economic perspective, eligible countries are required to have (1) an International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) or International Development Association (IDA) structural or sectoral adjustment loan or its equivalent, (2) a macroeconomic agreement with the International Monetary Fund or equivalent, and (3) instituted investment reforms, as evidenced by a bilateral investment treaty with the United States, an investment sector loan, or progress towards implementing an open investment regime. Each country that participates in the EAI must enter into an Americas Framework Agreement with the United States to establish an Americas Trust Fund and create enforcement mechanisms to insure payments into the fund and prompt disbursements out of the fund.9 Funds can be used to support environmental, natural resource, health protection, and child development programs within the debtor country.

Debt swaps, buybacks, and restructuring are three mechanisms authorized to conduct debt-for-nature transactions under the EAI. Seven of the eight countries that have participated in debt-for-nature transactions under the EAI used the debt-restructuring mechanism to generate environmental funds (see Table 3); only Peru took advantage of the debt buyback option. In a debt-restructuring agreement, the original debt agreement is cancelled (e.g., a percentage of the face value of the debt could be reduced) and a new debt agreement is created with a provision for an annual amount of money (in local currency) to be deposited into an environmental fund. In 1992, for example, the United States reduced a $310 million (face value) debt owed by Colombia by 10% in return for a total deposit of $41.6 million in local currency into an environmental fund managed by the Colombian government over 10 years.10 In a debt buyback, the debtor country purchases its debt at a reduced price. The lesser of either 40% of the repurchase price or the difference between the face value of the debt and the repurchase price is deposited in local currency into an environmental trust to support environmental and child support programs in the debtor country (P.L. 104-107, Title V, Sec. 574). For example, in 1998 Peru took advantage of this program and bought back $177 million in debt for $57 million, generating nearly $23 million (40% of the repurchase price) in local currency funds for conservation and child development programs. For all eight debtor countries, more than $1 billion (face value) of debt was reduced from a total debt of $1.9 billion, and almost $180 million of conservation funds were generated under the guidelines of the EAI (see Table 3).

All deposits into EAI funds have stopped, and some countries continue to award grants from their funds. Three transactions under the EAI continued to operate in 2015 (Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia, Argentina, and Peru have been concluded). These programs support small projects with grants and monitor existing projects that have been funded. Some examples of EAI projects include coastal zone marine management and hurricane relief projects in Jamaica, environmentally based development projects in the Peruvian Andes, and community conservation grants in Bolivia.11

|

Country |

Year |

Debt Reduction |

Original Value of Debt |

Conservation Funds Generated |

Duration (years) |

|

Bolivia |

1991 |

$30,700 |

$38,400 |

$21,800 |

15 |

|

El Salvador |

1992 |

469,900 |

614,000 |

41,200 |

20 |

|

Uruguay |

1992 |

3,700 |

34,400 |

6,190 |

12 |

|

Columbia |

1992 |

31,000 |

310,000 |

41,600 |

10 |

|

Chile |

1991 & 1992 |

30,600 |

186,000 |

18,700 |

10 |

|

Jamaica |

1991 & 1993 |

310,800 |

405,400 |

21,500 |

19 |

|

Argentina |

1993 |

3,800 |

38,100 |

3,100 |

14 |

|

Peru |

1998 |

177,000 |

350,000 |

22,840 |

n/a |

|

TOTAL |

1,057,500 |

1,976,300 |

176,930 |

Source: USAID, Enterprise for the Americas Initiative and the Tropical Forest Conservation Act: 2014 Financials Report, March 2015.

Note: EAI = Enterprise for the Americas Initiative (Title 15, Section 1512 of the Food, Agriculture Conservation and Trade Act of 1990, "1990 Farm Bill," P.L. 101-624; 7 U.S.C. 1738.)

Tropical Forest Conservation Act

Acknowledging that tropical rainforests were valuable for preserving biodiversity, reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide, and regulating hydrological cycles, Congress sought to expand the EAI authorization to countries throughout the world with tropical forests. The result was the 1998 Tropical Forest Conservation Act (TFCA, P.L. 105-214; 22 U.S.C. 2431), which was established to generate funds to conserve tropical forests by reducing external debt in countries with such forests. TFCA is an extension of the Enterprise for the Americas Act, in that it allows debt swaps, debt restructuring, and debt buybacks to generate conservation funds. These funds, however, are specifically designated for the conservation of tropical forests and are not confined to Latin America. To date, 14 countries have participated in this program, establishing 20 agreements (several countries have two agreements) that will reduce a total of at least $90.0 million from the face value of their debts to the United States and generate $339.4 million in local currency for tropical forest conservation projects (see Table 4). To date, the Republic of the Philippines completed the largest ever debt-for-nature transaction under the TFCA in 2013.

|

Subsidized Debt Swap In 2001, a different form of a debt-for-nature transaction emerged under the TFCA. The Nature Conservancy and the United States agreed to share costs to buy down a portion of debt that Belize owed to the United States. This partnership in debt-for-nature transactions is referred to as a subsidized debt swap. In a subsidized debt swap, an NGO generally matches a portion of the U.S. government contribution toward a debt-for-nature transaction. For example, in a transaction with Panama in 2003, the U.S. government provided $5.6 million and the Nature Conservancy provided $1.2 million to reduce Panama's debt by $10 million and generate $10 million in conservation funds. The transaction is completed when three agreements are signed: (1) the U.S. government and the beneficiary country sign a debt-restructuring agreement; (2) the U.S. government and the NGO sign an agreement to transfer NGO funds; and (3) the NGO and the beneficiary country sign a Forest Conservation Agreement.12 In a subsidized swap, the U.S. government is not a signatory to the Forest Conservation Agreement, yet it generally has representatives on the oversight committee.13 |

|

Countrya |

Year |

Budget Costb |

Private Funds Leveragedc |

Face Value Reduction of Debt |

Conservation Funds Generated |

Duration (years) |

|

Bangladesh |

2000 |

$6,000 |

$0.0 |

$600 |

$8,500 |

18 |

|

Belize |

2001 |

5,500 |

1,300 |

1,400 |

9,000 |

26 |

|

El Salvador |

2001 |

7,700 |

0.0 |

3,000 |

14,000 |

26 |

|

Peru I |

2002 |

5,500 |

1,100 |

3,700 |

10,600 |

12 |

|

Philippines I |

2002 |

5,500 |

0.0 |

100 |

8,300 |

14 |

|

Panama I |

2003 |

5,600 |

1,200 |

10,000 |

10,000 |

14 |

|

Columbia |

2004 |

7,000 |

1,400 |

n/a |

10,000 |

12 |

|

Panama II |

2004 |

6,500 |

1,300 |

n/a |

10,900 |

12 |

|

Jamaica |

2004 |

6,500 |

1,300 |

n/a |

16,000 |

20 |

|

Paraguay |

2006 |

4,800 |

0.0 |

n/a |

7,400 |

12 |

|

Guatemala |

2006 |

15,000 |

2,000 |

n/a |

24,400 |

15 |

|

Botswana |

2006 |

7,000 |

0.0 |

n/a |

8,300 |

10 |

|

Costa Rica I |

2007 |

12,600 |

2,500 |

n/a |

26,000 |

16 |

|

Peru II |

2008 |

19,600 |

0.0 |

n/a |

25,000 |

7 |

|

Indonesia I |

2009 |

20,000 |

2,000 |

n/a |

30,000 |

8 |

|

Brazil |

2010 |

19,500 |

0.0 |

20,800 |

21,000 |

5 |

|

Costa Rica II |

2010 |

19,600 |

3,900 |

21,000 |

27,000 |

15 |

|

Indonesia II |

2011 |

19,800 |

3,960 |

28,500 |

28,500 |

7 |

|

Philippines II |

2013 |

28,200 |

0 |

n/a |

31,800 |

10 |

|

Indonesia III |

2014 |

11,200 |

560 |

n/a |

12,700 |

7 |

|

TOTAL |

233,400 |

22,520 |

n/a |

339,400 |

n/a |

Sources: Email communications with Office of the Tropical Forest Conservation Act Secretariat, USAID 2004-2009, and the USAID, Operation of the Enterprise of the Americas Facility and Tropical Forest Conservation Act, Annual Report to Congress (Washington, DC, March 2004-2009). USAID, Enterprise for the Americas Initiative and the Tropical Forest Conservation Act: 2014 Financials Report, March 2015.

Notes: In the transaction with Peru in 2002, a total of $1.1 million was given by the Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife Fund, and Conservation International, and $5.5 million was given by the U.S. government.

n/a = not available.

a. The Kingdom of Thailand signed a debt-reduction agreement in September 2001. The signing of the second required agreement, the Tropical Forest Agreement, never took place. The Thai government annulled the agreement on January 30, 2003, amidst false media reports that warned that the U.S. government would retain control over forests involved in the agreement.

b. The budget cost of the debt is the funding provided by the U.S. government to reduce the face value of the original debt.

c. In some debt-for-nature transactions, a third party is involved (generally a nongovernmental organization) in the process and subsidizes a portion of the debt-reduction done by the United States. For example, NGOs such as the World Wildlife Fund, the Nature Conservancy, and Conservation International have subsidized these transactions.

To be eligible for this program, a developing country must contain at least one tropical forest with unique biodiversity, or a tropical forest tract that is representative of a larger tropical forest on a global, continental, or regional scale.14 Political and macroeconomic criteria for eligibility are almost identical to those used for participation under the EAI.15 Conservation funds (in local currency) from these transactions are deposited in a tropical forest fund for each country. The fund is overseen by an administrating body composed of one or more appointees chosen by the U.S. government and the government of the beneficiary country, and individuals who represent a broad range of environmental, academic, and scientific organizations in the beneficiary country (the majority of the board is represented by these individuals). This fund operates in the same manner as the Americas Fund: Local currency payments of interest accrued on restructured loans are deposited into a tropical forest fund and serve as the principal. Interest earned from this principal balance and the principal itself is usually given in the form of grants to fund tropical forest conservation projects. Eligible conservation projects include (1) the establishment, maintenance, and restoration of parks, protected reserves, and natural areas, and the plant and animal life within them; (2) training programs to increase the capacity of personnel to manage parks; (3) development and support for communities residing near or within tropical forests; (4) development of sustainable ecosystem and land management systems; and (5) research to identify the medicinal uses of tropical forest plants and their products.

The TFCA was reauthorized for appropriations in 2004, including $20 million for FY2005, $25 million for FY2006, and $30 million for FY2007. This law also authorizes funds to conduct audits and evaluations of debt-for-nature programs. A "TFCA Evaluation Sheet" has been created to evaluate the performance of TFCA country programs. The evaluation sheet establishes criteria for TFCA program categories and functions and is completed each year by the U.S. government representative on the local TFCA board or oversight committee. This law also authorizes the use of the principal of restructured loans for debt-for-nature transactions.

Issues for Congress

Rationale for and Criticism of Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

Advocates of debt-for-nature initiatives argue that reducing debt in developing countries will help create free-market systems (as part of the reforms required for eligibility), stimulate economic growth and trade liberalization, provide incentives for foreign investment, and help protect the environment. Converting hard currency debts to local currency debts, advocates argue, will lower debt burdens on developing countries and in the long run may reduce resource extraction at the expense of the environment. Critics of debt-for-nature initiatives argue that only a small percentage of debt is reduced, thereby minimizing the positive benefits of debt reduction in developing countries. For example, in some transactions under the TFCA, the interest paid for the debt is used for conservation projects, while the principle of the debt remains. Supporters point out that although the percentage of debt reduced by debt-for-nature transactions is small, the establishment of laws, programs, and funds dedicated to conservation that follows debt-for-nature initiatives in debtor countries is generally significant relative to what the country originally would have spent on conservation.16 The relationship between debt reduction and lower resource extraction rates is controversial. Some analysts suggest that debt reduction has no direct relationship to lower extraction rates of minerals or timber in developing countries with foreign debt.17

Advocates of debt-for-nature initiatives note that the United States has a history of supporting debt reduction initiatives in developing countries and appropriating funds for environmental causes. For example, the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative (22 U.S.C. §262p-6) aims to reduce debt in developing countries.18 HIPC was created by international creditors, the World Bank, and IMF to reduce debt of poor countries that have demonstrated social and economic policy reforms that enable fluid export revenues and capital inflows. Funds generated for the environment in developing countries arguably improve local environmental conditions, promote sustainable resource use, and help to preserve global biodiversity and ecosystem services. Critics argue that such benefits are limited in scope because conservation spending is unbalanced. The majority of conservation funds are often directed toward a few areas and specific projects that already feature work by organizations and researchers and do not address other areas that are equally rich in biodiversity.19

Advocates also suggest that debt-for-nature transactions that generate funds to support tropical forest conservation are especially appropriate to address climate change. Deforestation20 is responsible for the largest share of carbon dioxide (CO2) released to the atmosphere due to land use changes, approximately 20% of total anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions annually.21 Much of the deforestation responsible for CO2 releases occurs in tropical regions, specifically in developing countries such as Brazil, Peru, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Some of these tropical countries with high levels of total debt owed to the United States also have some of the largest areas of tropical forest cover. For example, Indonesia and has concessional debts to the United States totaling over $140 million, and has one of the largest areas of tropical forest cover in the world.22 Other countries, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan, also fit this pattern; however, these countries may be ineligible for debt-for-nature transactions under the TFCA due to political and economic eligibility requirements.23

Those who oppose debt-for-nature transactions often argue that they are not adequately enforced by debtor countries, generate insufficient funds to improve environmental problems, and may infringe on national sovereignty.24 Three-party debt transactions have historically had weak enforcement mechanisms; however, bilateral debt transactions such as those conducted under the EAI generally include safeguards and default provisions to protect the U.S. government from losing funds. National sovereignty became an issue with the first debt-for-nature swap in Bolivia when a conservation organization was reported to have obtained title to forested lands. There was a public outcry and ensuing political crisis when the Bolivian people thought a large part of their country had been given to a foreign organization. Consequently, conservation organizations involved in recent three-party transactions have generally refrained from directly buying land in debtor countries with conservation funds earned from debt-for-nature transactions.

Decline of Debt-for-Nature Transactions

The number of debt-for-nature transactions has declined in recent years, perhaps due to accounting changes that require greater appropriations to fund debt-for-nature transactions with official (public) debt and a higher price of commercial debt on the secondary market (see Figure 3). Before 1991, no appropriations were required for debt cancellations, and the United States cancelled between $11 billion and $12 billion in debt between 1988 and 1991. This changed with the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (2 U.S.C. 661a et seq.). This law requires that the net present value (NPV) of debts owed to the United States by foreign countries be used to calculate the cost of debt restructuring, buybacks, swaps, and cancellations to the U.S. government. The NPV of the loan is calculated often giving consideration to projected default losses, fees, and interest subsidies. Funds appropriated by Congress for conducting debt-for-nature transactions cover the cost of loan modifications, which could include a face-value reduction in the amount of eligible debt owed to the United States. TFCA has not received appropriations since FY2014.

A decline in three-party commercial debt-for-nature transactions may also be due to the conclusion of Brady Plan operations by Latin American countries. The Brady Plan allowed for partial debt forgiveness with a restructuring of the remaining debt into bonds that could be traded on the securities markets. When this program was concluded, the price of debt on the secondary market increased and financing leverage decreased, making it difficult and less attractive for environmental organizations to acquire debt for resale.25 Further, debt relief for developing countries is available through other programs that allow for relatively greater amounts of debt to be cancelled (e.g., HIPC). These programs may be more desirable to developing countries with debt than debt-for-nature initiatives under the EAI or TFCA. Under the TFCA, there was an 18-month period from 2004 to 2006 when no transactions were made, largely due to the length of time needed to negotiate and create debt-restructuring agreements. Lastly, the political and economic requirements needed to be eligible for debt-for-nature transactions make it difficult, according to some, for some countries with eligible debt to participate in EAI or TFCA programs.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. Note: Some debt transactions during this time period may not be represented in this figure due to limited data available from international sources and organizations. |

Effectiveness of Debt-for-Nature Transactions

Few studies have analyzed the effectiveness of debt-for-nature transactions. Because most of the transactions address several aspects of forest conservation, it would be difficult to comprehensively analyze their effectiveness in conserving tropical forests. A 2011 study on deforestation in poor countries found that poor nations that have implemented debt-for-nature transactions and have high levels of conservation funds tend to have lower rates of deforestation than countries that do not.26 Nevertheless, many conservation organizations support the framework of the TFCA and suggest that the TFCA should serve as a model for conserving other ecosystems, such as coral reefs and grasslands.27

Appropriations

Appropriations for debt reduction activities authorized by the EAI totaled $90 million; $40 million was appropriated for P.L. 480 debt reduction for FY1993 (P.L. 102-341) and $50 million was appropriated for other debt restructuring under EAI in FY1993 (P.L. 102-391). For debt reduction activities under TFCA, appropriations have totaled approximately $233.4 million from FY2000 to FY2013 (see Table 5). Authorization for appropriations under TFCA expired in FY2008, and Congress has not appropriated funding for the program since FY2013.

|

Fiscal Year |

Appropriated Amount |

Annual Obligation |

|

2000 |

$13.0 |

$7.0 |

|

2001 |

13.0 |

13.2 |

|

2002 |

Up to 25.0 (11.0 was given for the TFCA)a |

11.0 |

|

2003 |

Up to 40.0 (20.0 was given for the TFCA) |

5.6 |

|

2004 |

19.8 |

20.0 |

|

2005 |

20.0 |

0.0 |

|

2006 |

20.0 |

20.0 |

|

2007 |

20.0 |

19.6 |

|

2008 |

20.0 |

19.6 |

|

2009 |

20.0 |

20.0 |

|

2010 |

20.0 |

39.1 |

|

2011 |

16.4 |

19.8 |

|

2012 |

12.0 |

0.0 |

|

2013 |

11.4 |

28.3 |

|

2014 |

0.0 |

11.2 |

|

2015-2018 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Sources: Tropical Forest Conservation Act Secretariat, Enterprise for the Americas Initiative and Tropical Forest Conservation Act, 2014 Report, USAID, 2015, and federal appropriations laws.

a. This figure consists of $5 million in direct funds and $6 million in funds transferred from unobligated balances.

Future Directions

Bilateral debt-for-nature initiatives implemented by the U.S. government were supported through appropriations under programs such as the EAI and TFCA. Recently, appropriations for conducting debt-for-nature transactions under these programs have stopped. Additionally, there generally has been less interest in conducting debt-for-nature transactions. Some possible reasons for the decreased interests could include the following:

- Eligible debt to conduct these transactions has decreased, making these transactions either insignificant or not allowed for some debtor countries.

- The amount involved in the transactions is too small for some eligible countries to show interest in participating.

- There is a lack of appropriations to support debt-for-nature transactions.

- The focus on tropical forests (i.e., through TFCA) might be too narrow for many eligible countries.

Some Members of Congress contend that transactions under TFCA should continue because the program is included in strategies to address global climate change.28 Tropical forests make up the largest proportion of carbon stored in terrestrial land masses and are thought to be a carbon sink.29 Despite uncertainties on the part of some, it is generally thought that maintaining existing tropical forests will store carbon and that preventing deforestation will reduce the release of stored carbon into the atmosphere.30 The most recent debt-for-nature swap with Indonesia under the TFCA in 2014, for example, has been billed as a cooperative effort to deal with climate change.31 However, no quantitative analyses have examined the amount of stored-carbon emissions reduced by TFCA efforts. Others have supported expanding TFCA to include coral reefs. The addition of coral reefs to the program could expand the number of eligible countries for debt-for-nature transactions, pending economic and political criteria.32

Appendix. List of Related Laws and Appropriations That Support Debt-for-Nature Initiatives

- Continuing Appropriations Act for 1988 (P.L. 100-202; Section 537(C)(1-3)). Directs Secretary of the Treasury to analyze initiatives that would enable developing countries to repay portions of their debt obligations through investments in conservation activities.

- International Development and Finance Act of 1989 (P.L. 101-240; Title VII, Part A, Section 711) (22 U.S.C. 2282 - 2286). Authorizes USAID to provide assistance to nongovernmental organizations to purchase debt of foreign countries as part of a debt-for-nature agreement (i.e., three-party swap). Authorizes USAID to conduct a pilot program for debt-for-nature swaps with eligible sub-Saharan African countries.

- Support for East European Democracy (SEED) Act of 1989 (P.L. 101-179; Title I, Section 104) (22 U.S.C. 5414). Authorizes the President to undertake the discounted sale, to private purchasers, of U.S. government debt obligations from eligible Eastern European countries.

- FY1990 Foreign Operations Appropriations Act (P.L. 101-167; Title V, Section 533(e)) (22 U.S.C. 262p-4i - 262p-4j). Directs the Secretary of the Treasury to (1) support sustainable development and conservation projects when negotiating reduction of commercial debt and assisting with reduction of official (public) debt obligations, (2) encourage the World Bank to assist countries in reducing or restructuring private debt through environmental project and policy-based loans, and (3) encourage multilateral development banks to support lending portfolios that will allow debtor countries to restructure debt that may offer financial resources for conservation.

- Enterprise for the Americas Initiative (Title XV, Section 1512 of the Food, Agriculture Conservation and Trade Act of 1990) (P.L. 101-624; 104 Stat. 3658) (7 U.S.C. 1738b). Amends the Agriculture Development and Trade Act of 1954 to allow the President to reduce the amount of P.L. 480 sales credit debt owed to the United States by Latin American and Caribbean countries.

- Export Enhancement Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-429; Title I, Section 108) (12 U.S.C. 635i-6). Authorizes the sale, reduction, cancellation, and buyback of outstanding Export-Import Bank (Exim) loans for EAI purposes.

- Jobs Through Exports Act of 1992 (debt forgiveness authority under EAI) (P.L. 102-549; Title VI, Section 704) (22 U.S.C. 2430 and 22 U.S.C. 2421). Authorizes the sale, reduction, cancellation, and country buyback (through right of first refusal) of eligible Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) debt. Also authorizes the reduction of foreign assistance (USAID) debt.

- Enterprise for the Americas Initiative Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-532) (7 U.S.C. 1738m, p-r, etc.). Establishes guidelines for debt-for-nature swaps for Latin American and Caribbean countries.

- Agriculture Appropriations for FY1993 (P.L. 102-341). Provided $40 million for P.L. 480 debt reduction under EAI.

- Foreign Operations Appropriations for FY1993 (P.L. 102-391). Provided $50 million for debt restructuring under EAI.

- Foreign Operations Appropriations for FY1995 (P.L. 103-306; Title II, Section 534). Authorizes nongovernmental organizations associated with the Agency for International Development to place funds from economic assistance provided by USAID in interest-bearing accounts. Earned interest may be used for the purpose of the grants given.

- Foreign Operations Appropriations for FY1996 (P.L. 104-107; Title V, Section 571). Provides authority to perform debt buybacks/swaps with eligible loans made before January 1, 1995. For buybacks, the lesser of either 40% of the price paid or the difference between price paid and face value must be used to support conservation, child development and survival, or community development programs (Title V, Section 574).

- Tropical Forest Conservation Act of 1998 (P.L. 105-214) (22 U.S.C. 2431). Amends the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 to facilitate the protection of tropical forests through debt restructuring, buybacks, and swaps in eligible developing countries with tropical forests.

- Reauthorization of the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (P.L. 107-26). Authorizes the appropriation of $50 million, $75 million, and $100 million for FY2002, FY2003, and FY2004. Reduces the magnitude of investment reforms that must be in place for eligible countries.

- Reauthorization of Appropriations under the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (P.L. 108-323). Authorizes the appropriation of $20 million, $25 million, and $30 million for FY2005, FY2006, and FY2007, respectively. Includes authorization for evaluating programs and allows for the principal on debt agreements to be treated by the debt-for-nature transaction.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Thomas E. Lovejoy III, "Aid Debtor Nations' Ecology," New York Times, October 4, 1984, Sec. A, p. 31. |

| 2. |

S. 1023 defines a coral reef ecosystem as "any coral reef and coastal marine ecosystem surrounding, or directly related to, a coral reef and important to maintaining the ecological integrity of that coral reef, such as seagrasses, mangroves, sandy seabed communities, and immediately adjacent coastal areas." |

| 3. |

Sometimes debt is donated to the nongovernmental organization (NGO) in the three-party swap. |

| 4. |

P.L. 480 "Food for Peace" loans were low-interest loans given to developing countries to purchase U.S. agricultural products. |

| 5. |

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) foreign assistance loans. |

| 6. |

Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) loans are given to developing countries to enable them to import U.S. agricultural products. |

| 7. |

Export-Import (Ex-Im) Bank loans are made to foreign importers of U.S. goods and services. |

| 8. |

Although debt under the P.L. 480 program was the first to be authorized for debt-for-nature transactions, authorization quickly followed for reduction of debt owed to the United States under three other programs: (1) CCC programs, (2) Export-Import Bank loans, and (3) foreign aid loans administered by USAID. |

| 9. |

The Americas Trust Fund can be either an endowed fund or a sinking fund depending on the agreement reached by the United States and the debtor country. Interest payments made by debtor countries on their new restructured loans are deposited into the fund. These payments form the principal of the fund, and interest earned on this principal and the principal itself can be used to fund environmental, community development, and child survival and development programs. |

| 10. |

R. Curtis, "Bilateral Debt Conversions for the Environment, Peru: An Evolving Case Study," IUCN World Conservation Congress, Montreal (1996). |

| 11. |

USAID, Enterprise for the Americas Initiative and the Tropical Forest Conservation Act: 2014 Financials Report, March 2015. |

| 12. |

In comparison, the U.S. government is a signatory on a Tropical Forest Agreement, which is used with debt-for-nature transactions that are not subsidized by an NGO. |

| 13. |

This agreement generally addresses the structure of the conservation fund, its administrative council, and the use of monies from the fund, among other things. |

| 14. |

Developing country is defined as a "low-" or "middle-" income country as determined by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development in its World Development Report. According to 2013 data from the World Bank, the cutoff for low-income countries was a per capita annual income of $1,045 or less. For middle-income countries, the range for per capita annual income is more than $1,045 but less than $12,746. |

| 15. |

Instead of having in place major investment reforms in conjunction with an Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) loan or making progress toward implementing an open investment regime, the country must have in place a bilateral investment treaty with the United States, investment sector loans with the IADB, World Bank-supported reforms, or other measures as appropriate (22 U.S.C. 2431c). |

| 16. |

For example, Ecuador reduced its external debt of $8.3 billion by only $1 million from a debt-for-nature swap, yet doubled its budget for parks and reserves with money received from the resulting conservation fund. |

| 17. |

Dal Didia, "Debt-for-Nature Swaps, Market Imperfections, and Policy Failures as Determinants of Sustainable Development and Environmental Quality," Journal of Economic Issues (2001), pp. 477-486; and Esben Brandi-Hanson and Kaspar Svarrer, "Debt-for-Nature Swaps: One or the Other, or Both?" Royal Veterinarian and Agricultural University of Denmark, Department of Economics, 1998, p. 17. |

| 18. |

Eligibility requirements for participating in the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) program include that a country must receive only concessional financing from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) (i.e., borrowing only from the World Bank's International Development Association [IDA] and from the IMF's Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility [ESAF]), establish a track record of economic reforms under IMF- and World Bank-sponsored programs, and hold a debt burden that is unsustainable under existing (Naples terms) relief arrangements. |

| 19. |

John M. Shandra et al., "Do Commercial Debt-for-Nature Swaps Matter for Forests? A Cross National Test of World Polity Theory," Sociological Forum, vol. 26, no. 2 (June 2011), p. 387. |

| 20. |

Deforestation is the conversion of forests to pasture, cropland, urban areas, or other landscapes that have few or no trees. Afforestation is planting trees on lands that have not grown trees in recent years, such as abandoned cropland. |

| 21. |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, "Working Group I Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change," Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis (2007), at http://ipcc-wg1.ucar.edu/wg1/wg1-report.html. (Hereinafter referred to as 2007 IPCC WG I Report.) |

| 22. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury and Office of Management and Budget, "United States Government Foreign Credit Exposure as of 2018; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, "Global Forest Resources Assessment," 2015. |

| 23. |

Participation in three-party debt-for-nature swaps through USAID is not subject to the same economic and political criteria required for participation in TFCA and EAI debt-for-nature transactions. An eligible country must be committed to, plan for, and have a government or local NGO responsible for the long-term viability of the programs under the swap agreement. |

| 24. |

R. T. Deacon and P. Murphy, "The Structure of an Environmental Transaction: The Debt-for-Nature Swap," Land Economics (1997), pp. 1-24. |

| 25. |

The World Bank, "World Debt Tables, 1996," 1996. |

| 26. |

John M. Shandra et al., "Do Commercial Debt-for-Nature Swaps Matter for Forests? A Cross National Test of World Polity Theory," Sociological Forum, vol. 26, no. 2 (June 2011), pp. 401-402. |

| 27. |

Wildlife Conservation Society, "Say Yes to Tropical Forest Conservation," press release, 2018, at https://secure.wcs.org/campaign/tell-your-senators-say-yes-tropical-forest-conservation. |

| 28. |

Senator Rob Portman, "Portman Renews Efforts to Promote Conservation and Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions," press release, February 26, 2015, at http://www.portman.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ID=4E89FFE6-B315-460E-B3A3-6E5844619F9E. |

| 29. |

For more information, see CRS Report R41144, Deforestation and Climate Change, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 30. |

T. K. Rudel, Sequestering Carbon in Tropical Forests: Experiments, Policy Implications, and Climate Change, Society and Natural Resources, vol. 14 (2001), pp. 525-531. |

| 31. |

U.S. Embassy in Indonesia, "U.S. and Indonesia Award Grants to Promote Forest Conservation and Combat Climate Change," press release, April 29, 2014, at https://id.usembassy.gov/u-s-and-indonesia-award-grants-to-promote-forest-conservation-and-combat-climate-change-2/. |

| 32. |

Senator Rob Portman, "Portman, Bipartisan Senate Colleagues Introduce Legislation to Promote Conservation and Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions," press release, May 3, 2017, at https://www.portman.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ID=8E80A0C4-F03C-4420-BB19-44D7A7919875. |