Veto Threats and Vetoes in the George W. Bush and Obama Administrations

The Framers checked congressional legislative power by providing the President the power to veto legislation and, in turn, checked the President’s veto power by providing Congress a means to override that veto. Over time, it has become clear that the presidential veto power, even if not formally exercised, provides the President some degree of influence over the legislative process. Most Presidents have exercised their veto power as a means to influence legislative outcomes. Of 45 Presidents, 37 have exercised their veto power.

This report begins with a brief discussion of the ways Presidents communicate their intention to veto, oppose, or support a bill. It then examines the veto power and Congress’s role in the veto process. The report then provides analysis of the use of veto threats and vetoes and the passage of legislation during the George W. Bush Administration (2001-2009) and the Obama Administration (2009-2017) with some observations of the potential influence of such actions on legislation.

As specified by the U.S. Constitution (Article I, Section 7), the President has 10 days, Sundays excepted, to act once he has been presented with legislation that has passed both houses of Congress and either reject or accept the bill into law. The President has three general courses of action during the 10-day presentment period: The President may sign the legislation into law, take no action, or reject the legislation by exercising the office’s veto authority. A President’s return veto may be overridden, or invalidated, by a process also provided for in Article 1, Section 7, of the U.S. Constitution.

Because Congress faces a two-thirds majority threshold to override a President’s veto, veto threats may deter Congress from passing legislation that the President opposes. By going public with a veto threat, the President may leverage public pressure upon Congress to support his agenda. For purposes of this report, which focuses on the use of veto threats, the unit of analysis throughout is a veto (or a threatened veto), and the report does not distinguish between regular and pocket vetoes.

Formal, written Statements of Administration Policy (SAPs, pronounced “saps”) are frequently used to express the President’s support for or opposition to particular pieces of legislation and may include statements threatening to use the veto power. Among the Bush and Obama Administrations’ SAPs examined later in this report, for example, 24% and 48%, respectively, contained a veto threat.

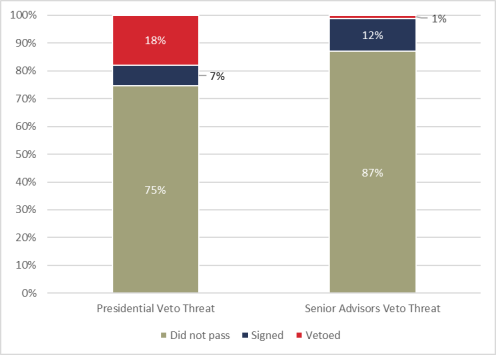

Although the relationship between Congress and a President may change every two years with each new Congress, the relationship between an Administration and its President may also change by presidential term. For example, while the number of veto threats in SAPs slowly increased during the first three Congresses of the Bush Administration, the number of veto threats grew sharply in the 110th Congress. In comparison to the Bush Administration, the Obama Administration steadily increased its use of veto threats issued in SAPs in every subsequent Congress.

President George W. Bush exercised the veto power 12 times during his presidency. Congress attempted to override six of President Bush’s 12 vetoes and succeeded four times. President Barack Obama similarly exercised the veto power 12 times during his presidency. Congress also attempted to override six of President Obama’s 12 vetoes and succeeded once. During the Bush and Obama Administrations, enrolled bills that passed both chambers and were met with a statement indicating that the President intended to veto the bill (a presidential veto threat SAP) were vetoed more often than were those that were met with a statement that agencies or senior advisors would recommend that the President veto the bill (a senior advisors threat SAP).

Veto Threats and Vetoes in the George W. Bush and Obama Administrations

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- The President's Veto Power

- Congress's Response

- Veto Threats in the Legislative Process

- Signaling Policy Intentions Before a Veto

- Verbal Veto Threats

- Written Veto Threats

- Veto Threats Within Different SAP Types

- Veto Threats During the George W. Bush and Obama Administrations

- George W. Bush Administration Veto Threats

- Obama Administration Veto Threats

- Congressional Responses to Veto Threats

- Legislative Action Following a Veto Threat

- Veto Threats and Veto Patterns

- George W. Bush Administration Vetoes and Ensuing Congressional Action

- Obama Administration Vetoes and Ensuing Congressional Action

Figures

- Figure 1. Percentage of SAPs with Veto Threats of Non-Appropriations Bills by Type of Veto Threat and Congress

- Figure 2. Number of George W. Bush Administration Veto Threats of Non-Appropriations Bills by Congress

- Figure 3. Percentage of George W. Bush Administration Veto Threats of Non-Appropriations Bills by Presidential Term

- Figure 4. Number of Obama Administration Veto Threats of Non-Appropriations Bills by Congress

- Figure 5. Percentage of Obama Administration Veto Threats of Non-Appropriations Bills by Presidential Term

- Figure 6. End Results of Non-Appropriations Bills That Received a Veto Threat

- Figure 7. End Results of Enrolled Non-Appropriations Bills That Received a Veto Threat

Summary

The Framers checked congressional legislative power by providing the President the power to veto legislation and, in turn, checked the President's veto power by providing Congress a means to override that veto. Over time, it has become clear that the presidential veto power, even if not formally exercised, provides the President some degree of influence over the legislative process. Most Presidents have exercised their veto power as a means to influence legislative outcomes. Of 45 Presidents, 37 have exercised their veto power.

This report begins with a brief discussion of the ways Presidents communicate their intention to veto, oppose, or support a bill. It then examines the veto power and Congress's role in the veto process. The report then provides analysis of the use of veto threats and vetoes and the passage of legislation during the George W. Bush Administration (2001-2009) and the Obama Administration (2009-2017) with some observations of the potential influence of such actions on legislation.

As specified by the U.S. Constitution (Article I, Section 7), the President has 10 days, Sundays excepted, to act once he has been presented with legislation that has passed both houses of Congress and either reject or accept the bill into law. The President has three general courses of action during the 10-day presentment period: The President may sign the legislation into law, take no action, or reject the legislation by exercising the office's veto authority. A President's return veto may be overridden, or invalidated, by a process also provided for in Article 1, Section 7, of the U.S. Constitution.

Because Congress faces a two-thirds majority threshold to override a President's veto, veto threats may deter Congress from passing legislation that the President opposes. By going public with a veto threat, the President may leverage public pressure upon Congress to support his agenda. For purposes of this report, which focuses on the use of veto threats, the unit of analysis throughout is a veto (or a threatened veto), and the report does not distinguish between regular and pocket vetoes.

Formal, written Statements of Administration Policy (SAPs, pronounced "saps") are frequently used to express the President's support for or opposition to particular pieces of legislation and may include statements threatening to use the veto power. Among the Bush and Obama Administrations' SAPs examined later in this report, for example, 24% and 48%, respectively, contained a veto threat.

Although the relationship between Congress and a President may change every two years with each new Congress, the relationship between an Administration and its President may also change by presidential term. For example, while the number of veto threats in SAPs slowly increased during the first three Congresses of the Bush Administration, the number of veto threats grew sharply in the 110th Congress. In comparison to the Bush Administration, the Obama Administration steadily increased its use of veto threats issued in SAPs in every subsequent Congress.

President George W. Bush exercised the veto power 12 times during his presidency. Congress attempted to override six of President Bush's 12 vetoes and succeeded four times. President Barack Obama similarly exercised the veto power 12 times during his presidency. Congress also attempted to override six of President Obama's 12 vetoes and succeeded once. During the Bush and Obama Administrations, enrolled bills that passed both chambers and were met with a statement indicating that the President intended to veto the bill (a presidential veto threat SAP) were vetoed more often than were those that were met with a statement that agencies or senior advisors would recommend that the President veto the bill (a senior advisors threat SAP).

The constitutional system of checks and balances and the separation of powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches is a cornerstone of the American system of government. By separating and checking powers in this way, the Framers hoped to prevent any person or group from seizing control over the nation's government. For example, the Framers checked congressional legislative power by providing the President the power to veto legislation and, in turn, checked the President's veto power by providing Congress a means to override that veto. Over time, it has become clear that the presidential veto power, even when not formally exercised, provides the President with an important tool to engage in the legislative process.

Most Presidents have exercised their veto power in an effort to block legislation. Of 45 Presidents, 37 have exercised their veto power. As of the end of 2019, Presidents have issued 2,580 vetoes, and Congress has overridden 111.1 President George W. Bush vetoed 12 bills during his presidency. Congress attempted to override six of them and succeeded four times. President Barack Obama also vetoed 12 bills during his presidency.2 Congress attempted to override six of them and succeeded once.

Presidents have also attempted to influence the shape of legislation through the use of veto threats. Since the 1980s, formal, written Statements of Administration Policy (SAPs, pronounced "saps") have frequently been used to express the President's support for or opposition to particular pieces of legislation.3 SAPs sometimes threaten to use the veto power if the legislation reviewed reaches the President's desk in its current form. Among the George W. Bush Administration (2001-2009) and the Obama Administration (2009-2017) SAPs examined later in this report, for example, 24% and 48%, respectively, contained a veto threat.

This report begins with a brief discussion of the veto power and Congress's role in the veto process. It then examines the ways Presidents communicate their intention to veto, oppose, or support a bill. The report then provides and discusses summary data on veto threats and vetoes during the Bush and Obama Administrations.

The President's Veto Power

As specified by the U.S. Constitution (Article I, Section 7),4 the President has 10 days, Sundays excepted, to act once he has been presented with legislation that has passed both houses of Congress and either reject or accept the bill into law.5 Within those 10 days, Administration officials consider various points of view from affected agencies (as is the case throughout the legislative process) and recommend a course of action to the President regarding whether or not to veto the presented bill.6

The President has three general courses of action during the 10-day presentment period: The President may sign the legislation into law, take no action and allow the bill to become law without signature after the 10 days, or reject the legislation by exercising the office's veto authority.7

The President may reject legislation in two ways. The President may veto the bill and "return it, with his Objections to that House in which it shall have originated."8 This action is called a "regular" or "return" veto (hereinafter return veto). Congress typically receives the objections to the bill in a written veto message.

If Congress has adjourned during the 10-day period, the President might also reject the legislation through a "pocket veto." This occurs when the President retains, but does not sign, presented legislation during the 10-day period, with the understanding that the President cannot return the bill to a Congress that has adjourned.9 Under these circumstances, the bill will not become law.10 A pocket veto is typically marked by a type of written veto message known as a "Memorandum of Disapproval."11 As discussed in greater detail below, this practice has sometimes been controversial, because arguably it prevents Congress from attempting to override the President's veto.

Congress's Response

A President's return veto may be overridden, or invalidated, by a process provided for in Article 1, Section 7, of the U.S. Constitution. To override a return veto, Congress may choose to "proceed to reconsider" the bill.12 Passage by two-thirds of Members in each chamber is required to override a veto before the end of the Congress in which the veto is received.13 Neither chamber is under any constitutional, legal, or procedural obligation to conduct an override vote. It is not unusual for either chamber of Congress to make no effort to override the veto if congressional leaders do not believe they have sufficient votes to do so.

If a two-thirds vote is successful in both chambers, the President's return veto is overridden, and the bill becomes law. If a two-thirds vote is unsuccessful in one or both chambers, the veto is sustained, and the bill does not become law.

In contrast, Congress cannot override the President's pocket veto. By definition, a pocket veto may occur only when a congressional adjournment prevents the return of the vetoed bill. If a bill is pocket vetoed while Congress is adjourned, the only way for Congress to pass a version of the policy contained in the vetoed bill is to reintroduce the legislation as a new bill, pass it through both chambers, and present it to the President again for signature. Recent Presidents and Congresses have disagreed about what constitutes an adjournment that prevents the return of a bill such that a pocket veto may be used.14

For purposes of the sections below concerning the use of veto threats, the unit of analysis is a veto. The analysis does not distinguish between regular and pocket vetoes.

Veto Threats in the Legislative Process

Because Congress faces a two-thirds majority threshold to override a President's veto, veto threats may deter Congress from passing legislation that the President opposes.15 The veto override threshold may also prompt Congress to change a bill in response to a veto threat. The Framers of the U.S. Constitution viewed the veto power as a way of reminding Congress that the President also plays an important legislative role and that threatening to use the veto power can influence legislators into creating more amenable bills.16 Political scientist Richard A. Watson writes that "the veto is available to a President as a general weapon in his conflicts with Congress: Franklin Roosevelt sometimes asked his aides for 'something I can veto' as a lesson and reminder to congressmen that they had to deal with a President."17

Veto threats are, therefore, an important component in understanding the use of the President's veto power. In recent presidencies, these threats have generally been expressed either through SAPs or verbally.18 President Trump has also used social media to communicate his intention to veto, oppose, or support a bill.

Signaling Policy Intentions Before a Veto

Presidents may signal their intention to support, oppose, or veto a bill early in the legislative process using both verbal and written means. For example, Presidents can mention in a speech that they intend to veto legislation, or they can authorize others (such as a press secretary) to verbally indicate the Administration's position on specific legislation. Presidents can also issue, through the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), formal, written SAPs to communicate their intention to veto, oppose, or support a bill.

Verbal Veto Threats

Verbal veto threats may include commentary related to the President's strategy for working with Congress along with a threat to veto legislation if the President's policy agenda is not heeded. For example, at a press conference President George W. Bush explained, "I want the Members of Congress to hear that once we set a budget we're going to stick by it. And if not, I'm going to use the veto pen of the President of the United States to keep fiscal sanity in Washington, D.C."19 In another instance, President Obama said that the House "is trying to pass the most extreme and unworkable versions of a bill that they already know is going nowhere, that can't pass the Senate and that if it were to pass the Senate I would veto. They know it."20 In these remarks, both President Bush and President Obama used their words to attempt to deter Congress from passing bills that did not match the President's policy agenda and unambiguously remind the public of their veto power.

Written Veto Threats

Formal, written SAPs are frequently used to express the President's support for or opposition to particular pieces of legislation. The decision to issue a SAP is a means for the President to insert the Administration's views into the legislative debate. While SAPs provide Presidents an opportunity to assert varying levels of support for or against a bill, perhaps the most notable statement in a SAP is whether the Administration intends to veto the bill. Members of Congress may pay particular attention to a SAP when a veto threat is being made.21 At least one congressional leader has characterized SAPs as forerunner indicators of a veto.22

SAPs are often the first public document outlining the Administration's views on pending legislation and allow for the Administration to assert varying levels of support for or opposition to a bill. Because written threats are typically required to be scrutinized by the Administration through the central legislative clearance process in advance of their release, written SAP veto threats are often considered more formal than verbal veto threats.23

When a SAP indicates that the Administration may veto a bill, it appears in one of two ways:

- 1. A statement indicating that the President intends to veto the bill (hereinafter a presidential veto threat) or

- 2. A statement that agencies or senior advisors would recommend that the President veto the bill (hereinafter a senior advisors veto threat).

These two types of SAPs indicate degrees of veto threat certainty. Generally speaking, a presidential veto threat signals the President's strong opposition to the bill. A senior advisors veto threat, on the other hand, may signal that the President may be more likely to enter into negotiations in order to reach a compromise with Congress on the bill.24

By publicly issuing a veto threat, the President may leverage public pressure upon Congress to support the President's agenda. Furthermore, many SAPs propose a compromise to Congress wherein the President would not exercise a veto.25 In addition, a President or an Administration's senior advisors may not always issue a veto threat prior to a decision to veto passed legislation. As discussed below, both Presidents Bush and Obama vetoed legislation for which they never issued a written veto threat.

Veto Threats Within Different SAP Types

During both the Obama and Bush Administrations, roughly three-quarters of SAPs issued were on non-appropriations bills, and roughly one-quarter concerned appropriations bills. Each SAP signaled the Administration's intent to veto, oppose, or support a bill. There are fundamental differences between non-appropriations bill SAPs and appropriations bill SAPs.26

Non-appropriations bill SAPs typically involve specific policy objections, such as how a program operates or what constituency the program is designed to serve. Appropriations bill SAPs, in contrast, often involve more general budgetary policy objections, such as the perceived need to balance the budget or to reallocate resources for other purposes. Therefore, the President may generally support a particular provision in an appropriations bill on programmatic policy grounds but oppose it for budgetary reasons. Or the President may oppose a particular provision in an appropriations bill for both programmatic and budgetary reasons.

This report focuses on the impact of the President's veto threat in non-appropriations bill SAPs given their more targeted nature.27

Veto Threats During the George W. Bush and Obama Administrations

Data in this report were compiled from SAPs located on the archived White House websites of the Bush and Obama Administrations. Using the classification of SAPs on each website, analysis was conducted with only non-appropriations SAPs for reasons described above. The analysis examined each SAP and individually assessed whether the SAP contained a veto threat, the type of threat (presidential or senior advisor), and whether the veto threat concerned a part of the bill or the whole bill. The analysis considers each SAP to be an individual veto threat. In instances where one bill received veto threats in multiple SAPs, veto threats were counted individually and not combined. To assess the final outcome of bills, the analysis used information on bill statuses located at Congress.gov and does not track whether bills that received a SAP were later combined into other legislative vehicles. The inherent limitations in this methodology make it difficult to determine direct effects of any veto threat on the final outcome of a bill. However, in the aggregate, general trends may be observed.

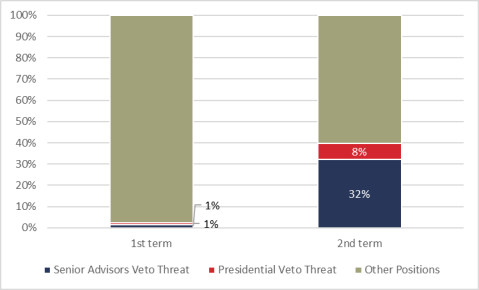

The proportion of non-appropriation bill SAPs with veto threats steadily increased over the course of each of the two presidencies reviewed. SAPs containing veto threats as a proportion of all SAPs was at its highest at the conclusion of both President Bush's and President Obama's second terms. Figure 1 illustrates this trend by showing SAP veto threats as a percentage of issued SAPs.

|

Figure 1. Percentage of SAPs with Veto Threats of Non-Appropriations Bills by Type of Veto Threat and Congress |

|

|

Source: OMB, "Statements of Administration Policy on Non-Appropriations and Appropriations Bills," https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/omb/legislative/sap/index.html; American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/app-categories/written-statements/presidential/statements-administration-policy; Internet Archive, https://archive.org/. Note: SAPs concerning appropriations bills, as categorized by the Bush and Obama Administrations, were excluded from the data used for this graph. |

George W. Bush Administration Veto Threats

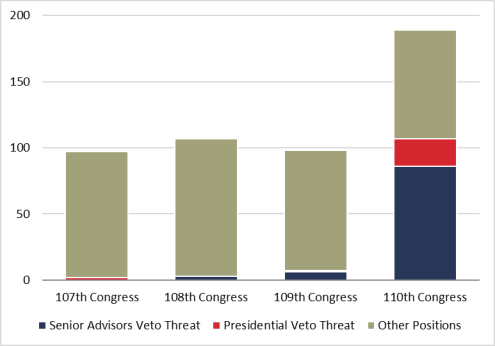

While the Bush Administration remained relatively consistent in the number of veto threats issued in SAPs during its first six years, the number of threats increased during the final two years of the Administration. The Bush Administration issued a total of 491 SAPs on non-appropriations bills.28 Just under one-quarter (24%) of the non-appropriations bill SAPs contained a veto threat: 24 presidential veto threats and 94 senior advisors veto threats. Of bills that received a presidential veto threat, one was signed by the President, seven were vetoed, and the remaining 16 did not make it to the President's desk. Of bills that received a senior advisors veto threat, 16 were signed, one was vetoed, and the remaining 77 were not passed by both chambers. Seven of the 12 Bush Administration vetoes were preceded by a SAP containing a veto threat.

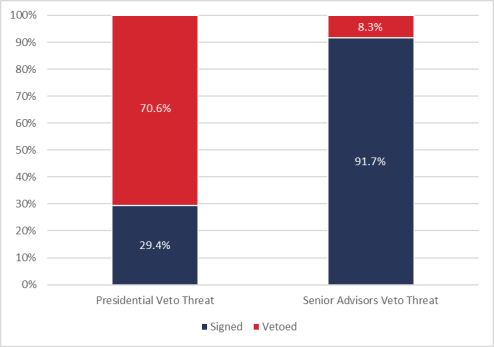

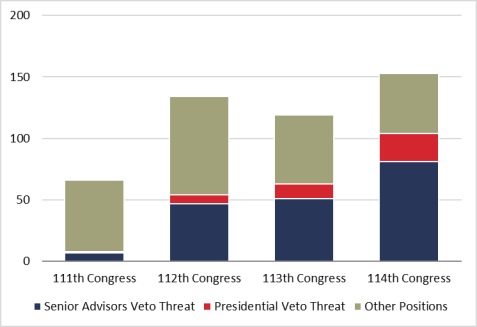

While the number of veto threats in SAPs slowly increased during the first three Congresses of the Bush Administration (two in the 107th Congress, three in the 108th Congress, and seven in the 109th Congress), the number of veto threats grew sharply in the 110th Congress—to 107 veto threats—coinciding with Democrats gaining control of both chambers of Congress during the Republican President's final two years in office. This might suggest (and is supported by Obama Administration data) that the partisan constitution of Congress, as well as whether the Administration is in its first or second term, may impact the number of veto threats issued.29 Below, Figure 2 illustrates this change in the number of veto threats over time across the four Congresses associated with President Bush's two terms in office.

|

Figure 2. Number of George W. Bush Administration Veto Threats of Non-Appropriations Bills by Congress 107th-110th Congresses |

|

|

Source: OMB, "Statements of Administration Policy on Non-Appropriations and Appropriations Bills," https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/omb/legislative/sap/index.html. SAPs were also viewed by using the archives at the American Presidency Project, located at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/app-categories/written-statements/presidential/statements-administration-policy, and the Internet Archive, located at https://archive.org/. Note: The SAPs analyzed exclude those concerning appropriations bills as categorized by the Bush Administration. |

Nevertheless, presidential veto threats in the Bush Administration remained a fraction of overall veto threats and often resulted in an actual veto.30 The rarity with which the Bush Administration issued presidential veto threats suggests that the Administration viewed them as a message to be used sparingly.

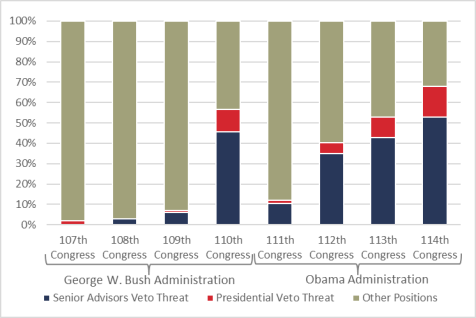

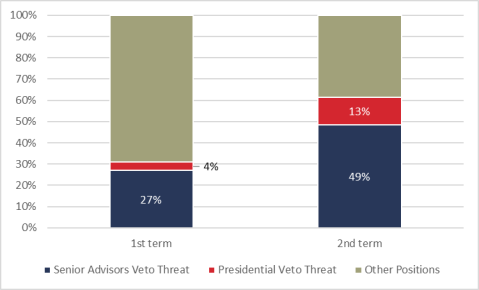

Although the relationship between Congress and a President may change every two years with each new Congress, the relationship between an Administration and its President may also change by presidential term. Compared to a President's first term, in a second term Administration, executive branch officials may become more adept in coordinating the veto power.31 Additionally, a second-term President cannot be re-elected, which may allow the Administration to take a stronger position on unfavorable legislation. Alternatively, it could be that the President lacks the political influence necessary to advance his legislative agenda and instead relies on veto power to block legislative vehicles more often as his presidency concludes. Figure 3 presents veto threat percentages by presidential term for the Bush Administration, showing an increase in the President's second term.

|

Figure 3. Percentage of George W. Bush Administration Veto Threats of Non-Appropriations Bills by Presidential Term |

|

|

Source: OMB, "Statements of Administration Policy on Non-Appropriations and Appropriations Bills," https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/omb/legislative/sap/index.html. SAPs were also viewed by using the archives at the American Presidency Project, located at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/app-categories/written-statements/presidential/statements-administration-policy, and the Internet Archive, located at https://archive.org/. Note: The SAPs analyzed exclude those concerning appropriations bills as categorized by the Bush Administration. |

During President Bush's first term (2001-2005), 98% of SAPs did not contain a veto threat, 1% contained a senior advisors veto threat, and 1% contained a presidential veto threat.32 During President Bush's second term (2005-2009), 60% did not contain a veto threat, 32% contained a senior advisors veto threat, and 8% contained a presidential veto threat.

Obama Administration Veto Threats

In comparison to the Bush Administration, the Obama Administration steadily increased its use of veto threats issued in SAPs in every subsequent Congress. The Obama Administration issued 472 SAPs on non-appropriations bills.33 Just under half (48%) of these contained a veto threat: 43 presidential veto threats and 186 senior advisors veto threats. Of bills that received a presidential veto threat, four were ultimately signed by the President, five were vetoed, and 34 did not make it to the President's desk. Of bills that received a senior advisors veto threat, 17 were signed, two were vetoed, and 167 were not passed by the two chambers. Six of the 12 Obama Administration vetoes were preceded by a SAP containing a veto threat.

President Obama (a Democrat) issued more veto threats in his SAPs with each passing Congress. (Democrats controlled both chambers during the 111th Congress and the Senate during the 112th Congress, and Republicans controlled the House during the 113th Congress and both chambers during the 114th Congress.34) Below, Figure 4 illustrates this change in the number of veto threats over time by Congress.

|

Figure 4. Number of Obama Administration Veto Threats of Non-Appropriations Bills by Congress 111th-114th Congresses |

|

|

Source: OMB, "Statements of Administration Policy on Non-Appropriations and Appropriations Bills," https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/legislative_sap_default. Note: The SAPs analyzed exclude those concerning appropriations bills as categorized by the Obama Administration. |

Although the number of veto threats increased over the course of the Obama presidency (eight in the 111th Congress, 54 in the 112th Congress, 63 in the 113th Congress, and 104 in the 114th Congress), the number of presidential veto threats remained small when compared to the total number of veto threats, varying from a low of 14.3% in the 111th Congress to a high of 28.3% in the 114th Congress. The increase over time in total number of veto threats may indicate that President Obama was presented with more legislation he was likely to oppose. However, the increase is mostly composed of senior advisors veto threats. This suggests that the Administration nonetheless treated presidential veto threats, compared to senior advisors veto threats, as a tool to be used more rarely.

As with the Bush Administration, President Obama's use of veto threats in the first and second terms differ. Figure 5 presents veto threat percentages by presidential term as opposed to by Congress.

|

Figure 5. Percentage of Obama Administration Veto Threats of Non-Appropriations Bills by Presidential Term |

|

|

Source: OMB, "Statements of Administration Policy on Non-Appropriations and Appropriations Bills," https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/legislative_sap_default. Note: The SAPs analyzed exclude those concerning appropriations bills as categorized by the Obama Administration. |

During President Obama's first term (2009-2013), 69% of SAPs did not contain a veto threat, 27% contained a senior advisors veto threat, and 4% contained a presidential veto threat.35 During President Obama's second term (2013-2017), 39% of SAPs did not contain a veto threat, 49% contained a senior advisors veto threat, and 13% contained a presidential veto threat.

Congressional Responses to Veto Threats

CRS analyzed all veto threats contained in SAPs on non-appropriations legislation across these two Administrations and determined whether the veto threat was isolated to a provision of the bill (a partial bill veto threat) or if the veto threat was not particularized (a whole bill veto threat).

President Bush issued partial bill veto threats and whole bill veto threats an equal amount of the time. However, the type of threat he used in each category varied. Of partial bill veto threats, 7% were presidential veto threats and the remaining 93% were senior advisors veto threats. Of whole bill veto threats, 34% were presidential veto threats and the remaining 66% were senior advisors veto threats.

In contrast, President Obama issued partial bill veto threats more sparingly (8% versus 92% for whole bill veto threats). Similar to President Bush, however, of partial bill veto threats, 6% were presidential veto threats and the remaining 94% were senior advisors veto threats. Of whole bill veto threats, 20% were presidential veto threats and the remaining 80% were senior advisors veto threats.

The difference in frequency of partial and whole bill veto threats across the Administrations may suggest that the two Presidents viewed the use of veto threats differently: One President may have used partial threats to negotiate more with Congress, whereas another President preferred to threaten a veto only when he viewed an entire bill as unfavorable. Likewise, the increased frequency of partial bill senior advisors veto threats suggests that both Presidents preferred to use presidential veto threats in rejecting an entire bill and leaving senior advisors veto threats for negotiations where only part of a bill is unfavorable.36

Legislative Action Following a Veto Threat

A presidential veto threat in a SAP may be more likely than a senior advisors veto threat to deter passage of a bill because of the President's direct association with the threat. However, an analysis of these two Administrations does not necessarily support this argument. Figure 6 shows that bills appeared less likely to pass when the bill received a senior advisors veto threat versus a presidential veto threat. This may be due to a number of factors, including that senior advisors threats are more frequently issued than presidential veto threats (279 senior advisors threats and 67 presidential veto threats were issued across these two presidencies) or that Congress may perceive it to be beneficial to pass presidentially threatened legislation anyway based on certain political calculations and circumstances.37

Veto Threats and Veto Patterns

During the Bush and Obama Administrations, enrolled bills that passed both chambers and were met with a presidential veto threat SAP were vetoed more often than were those that were met with a senior advisors threat. Figure 7 shows the outcomes of bills receiving veto threats that were passed by Congress and sent to the President. Across both the Bush and Obama Administrations, a bill that received a presidential veto threat and was passed was followed by a veto 70.6% of the time, whereas a bill that received a senior advisors veto threat was later vetoed 8.3% of the time.

When a President vetoes a bill, it marks the end of the President's ability to procedurally affect whether or not a bill becomes law. Whether or not that specific bill becomes law is no longer in the President's hands. Congress may or may not elect to attempt an override.38

George W. Bush Administration Vetoes and Ensuing Congressional Action

President Bush exercised the veto power 12 times.39 Four of these vetoes were overridden. Six vetoed bills were forewarned with a written veto threat. (Four received a presidential threat, and two received senior advisors threats.) Three additional bills received statements noting the Administration's opposition to the bill but did not include a veto threat. None of the bills that Congress later overrode were preceded by a presidential veto threat.

Three-quarters of President Bush's vetoes (9 of 12) were preceded by a written statement of opposition to the bill. President Bush also issued multiple written veto threats on four bills that would later receive a veto: Three bills received two threats each, and one bill received two statements of opposition.

Obama Administration Vetoes and Ensuing Congressional Action

President Obama vetoed 12 bills, and Congress overrode his veto once. As was true for President Bush, six of President Obama's vetoes were preceded by a written veto threat (four presidential and two senior advisors threats). Unlike the patterns observed for the Bush presidency, however, all of President Obama's veto threats were whole bill veto threats.

Whereas President Bush also communicated in SAPs his opposition to three bills short of threatening a veto, President Obama either did not issue a SAP at all or issued one that contained a veto threat. One of President Obama's vetoed bills received two veto threats. President Obama's approach of issuing either no statement at all on a bill or a statement containing a veto threat marks a different approach from the one used by President Bush.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Sarah B. Solomon, former CRS Research Associate, contributed to this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

U.S. Congress, Senate, Secretary of the Senate, "Summary of Bills Vetoed, 1789-present," https://www.senate.gov/reference/Legislation/Vetoes/vetoCounts.htm. President Donald Trump has issued six vetoes. |

| 2. |

President Bush issued 204 non-appropriations Statements of Administration Policy (SAPs) in his first term and 287 in his second term. Similarly, President Obama issued 200 non-appropriations SAPs in his first term and 272 in his second term. The number of SAPs issued may be impacted by internal Administration practice and the number of bills introduced in Congress. For purposes explained later in the report in "Veto Threats Within Different SAP Types," this report focuses on veto threats of non-appropriations legislation. |

| 3. |

For more information on SAPs, see CRS Report R44539, Statements of Administration Policy, by Meghan M. Stuessy. |

| 4. |

Article I, Section 7, of the U.S. Constitution reads in part, "Every Bill which shall have passed the House of Representatives and the Senate, shall, before it become a Law, be presented to the President of the United States; If he approve he shall sign it, but if not he shall return it, with his Objections to that House in which it shall have originated, who shall enter the Objections at large on their Journal, and proceed to reconsider it. If after such Reconsideration two thirds of that House shall agree to pass the Bill, it shall be sent, together with the Objections, to the other House, by which it shall likewise be reconsidered, and if approved by two thirds of that House, it shall become a Law." |

| 5. |

For more information, see CRS Report RS22188, Regular Vetoes and Pocket Vetoes: In Brief, by Meghan M. Stuessy. |

| 6. |

This process derives from OMB Circular A-19 and is known as "central legislative clearance." For more information about Circular A-19, see CRS Report R44539, Statements of Administration Policy, by Meghan M. Stuessy. |

| 7. |

For a visual representation of these courses of action, including information on what may happen when a President chooses not to act on presented legislation, see CRS Report IG10007, Presentation of Legislation and the Veto Process, by Meghan M. Stuessy. |

| 8. |

U.S. Const., art. I, §7. |

| 9. |

Charles W. Johnson, John V. Sullivan, and Thomas J. Wickham Jr., House Practice: A Guide to the Rules, Precedents, and Procedures of the House (Washington: GPO, 2017), ch. 57, pp. 933-935. |

| 10. |

For more information about this debate on the limits of the pocket veto power, a copy of the congressional distribution memo "Asserted Use of the Pocket Veto During the George W. Bush and Barack Obama Administrations," by Alissa M. Dolan and Meghan M. Stuessy, is available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 11. |

House Practice, ch. 57, p. 930. In both cases, the U.S. Constitution under Article II, Section 7, requires that a veto message accompany the President's veto. What the President titles the message, however, provides insight into how the President classifies the veto into one of these two types. The type of message sent is an indicator of the interbranch disagreement over the use of the veto power. |

| 12. |

For more detailed information, see CRS Report RS22654, Veto Override Procedure in the House and Senate, by Elizabeth Rybicki. |

| 13. |

Congressional procedure interprets this requirement to mean two-thirds of those Members voting, provided there is a quorum present. House Practice, ch. 57, p. 933. See also Floyd M. Riddick and Alan S. Frumin, Riddick's Senate Procedure: Precedents and Practices, S.Doc. 101-28, 101st Cong., 2nd sess. (Washington: GPO, 1992), p. 1388. |

| 14. |

President George W. Bush and the 110th Congress had one such disagreement, and President Obama and Congress had five (in the 111th and 114th Congresses). For more information about this debate on the limits of the pocket veto power, including information on each of these disagreements, see "Asserted Use of the Pocket Veto During the George W. Bush and Barack Obama Administrations." |

| 15. |

Political scientist Richard Neustadt suggests that presidential power includes "the power to persuade." He discusses the President's veto authority and appointment authority, among other formal powers, but notes, "The President's advantages are checked by the advantages of others. Continuing relationships will pull in both directions. These are relationships of mutual dependence. A President depends upon the persons whom he would persuade; he has to reckon with his need or fear of them…. Their vantage points confront his own; their power tempers his. Persuasion is a two-way street." Richard Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents: The Politics of Leadership from Roosevelt to Reagan (New York: The Free Press, 1991), pp. 11, 31. |

| 16. |

Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 73 speaks of the threat of using a veto: "A power of this nature, in the executive, will often have a silent and unperceived though forcible operation. When men engaged in unjustifiable pursuits are aware, that obstructions may come from a quarter which they cannot control, they will often be restrained, by the bare apprehension of opposition, from doing what they would with eagerness rush into, if no such external impediments were to be feared." |

| 17. |

Richard A. Watson, "Origins and Early Development of the Veto Power," Presidential Studies Quarterly (Spring 1987), p. 410. |

| 18. |

Standardized practices have evolved for determining and communicating the Administration's perspective on active legislation. The process derives from Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-19 and is known as "central legislative clearance." For more information about Circular A-19, see CRS Report R44539, Statements of Administration Policy, by Meghan M. Stuessy. |

| 19. |

U.S. President (George W. Bush), "Remarks at a Dinner Honoring Senator Pete V. Domenici in Albuquerque," 37 Federal Register 1176-1181, August 15, 2001. |

| 20. |

The White House: Office of the Press Secretary, Press Conference by the President, August 1, 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/08/01/press-conference-president. |

| 21. |

Some Members of Congress call particular attention to SAPs that contain veto threats in remarks on the floor. For examples of such references from the 114th Congress, see Rep. Michael Burgess, Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 161, part 173 (December 1, 2015), pp. H8658-H8660; Rep. Alcee Hastings, Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 161, part 170 (November 18, 2015), pp. H8295-H8296; and Rep. Alcee Hastings, Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 161, part 63 (April 29, 2015), pp. H2512-H2513. |

| 22. |

Hon. Harry Reid, Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 161, part 63 (April 29, 2015), p. S2492. |

| 23. |

For more information about veto threats as a policy tool of the President, see Rebecca E. Deen and Laura W. Arnold, "Veto Threats as a Policy Tool: When to Threaten?," Presidential Studies Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 1 (March 2002), pp. 30-45. For more information about the central legislative clearance process prescribed by OMB Circular A-19, see CRS Report R44539, Statements of Administration Policy, by Meghan M. Stuessy. |

| 24. |

Samuel Kernell writes, "The more visible and categorical the rhetoric, the less wiggle room presidents would leave themselves to sign a bill that does not satisfy the conditions listed in the threat." The ability of the President to disagree with his senior advisors may provide this additional "wiggle room" in a way a presidential veto threat does not. See Samuel Kernell, Going Public, 4th ed. (Washington: CQ Press, 2007), pp. 61-62, 65. |

| 25. |

Kernell, Going Public, pp. 60, 63. For example, in the Obama Administration's SAP on H.R. 2647, the Administration suggested that a particular provision of the bill would warrant President Obama's veto, and its exclusion would make the bill more likely to receive the President's signature. The SAP states that the Administration supports House passage of the bill. However, "If the final bill presented to the President contains this provision, the President's senior advisors would recommend a veto." Executive Office of the President, Statement of Administration Policy: H.R. 2647—National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010, June 24, 2009, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/legislative/sap/111/saphr2647h_20090624.pdf. |

| 26. |

Using OMB's central legislative clearance process, SAPs are drafted by the Budget Review Division if they primarily concern appropriations legislation and by the Legislative Reference Division if they otherwise constitute substantive legislation. This process is governed by OMB Circular A-19. For more information on SAPs, see CRS Report R44539, Statements of Administration Policy, by Meghan M. Stuessy. |

| 27. |

This report focuses on written veto threats in SAPs. However, if a verbal threat were followed by a written threat in a non-appropriations SAP, it too may be captured in the discussion below. |

| 28. |

The Bush Administration issued 660 SAPs total: 491 on non-appropriations bills and 169 on appropriations bills. The number of SAPs issued may be impacted by internal Administration practice and the number of bills introduced in Congress. |

| 29. |

Political science literature continues to catalog potential causes of veto threats. However, the focus of this report is to provide context on the quantity and timing of veto threats. For more information on ways to catalog veto threats, see Deen and Arnold, "Veto Threats as a Policy Tool," pp. 30-45. This paper describes veto threats in terms of environmental factors, presidential resources, and policy- and threat-related factors. Office of the Historian: U.S. House of Representatives, Party Divisions of the House of Representatives: 1789-Present, http://history.house.gov/Institution/Party-Divisions/Party-Divisions/; and Senate Historical Office: U.S. Senate, Party Division, https://www.senate.gov/history/partydiv.htm. |

| 30. |

The relationship between a presidential veto threat and an actual veto will be further discussed in "Veto Threats and Veto Patterns" below. |

| 31. |

Andrew W. Barrett and Matthew Eshbaugh-Soha, "Presidential Success on the Substance of Legislation," Political Research Quarterly, vol. 60, no. 1 (March 2007), p. 108. |

| 32. |

President Bush issued 204 non-appropriations SAPs in his first term and 287 in his second term. The number of SAPs issued may be impacted by internal Administration practice and the number of bills introduced in Congress. |

| 33. |

The Obama Administration issued 572 SAPs total: 472 on non-appropriations bills and 100 on appropriations bills. The number of SAPs issued may be impacted by internal Administration practice and the number of bills introduced in Congress. |

| 34. |

Office of the Historian: U.S. House of Representatives, Party Divisions of the House of Representatives: 1789-Present, http://history.house.gov/Institution/Party-Divisions/Party-Divisions/; and Senate Historical Office: U.S. Senate, Party Division, https://www.senate.gov/history/partydiv.htm. |

| 35. |

President Obama issued 200 non-appropriations SAPs in his first term and 272 in his second term. |

| 36. |

Few studies of veto threats within SAPs have been conducted as of the date of this report. However, some studies have noted the difference between senior advisors and presidential veto threats, and this may warrant additional research. With regard to particularized veto threats, Samuel Kernell's 2015 work concludes, "Timely, credible veto threats prompt legislators to reassess which legislative bundles stand the best chance of achieving their policy goals. With veto threats, presidents send strong signals identifying for both the public and copartisans in Congress those policies on which the parties disagree." |

| 37. |

Kernell notes, "For some legislation, Presidents sense they can score points in public opinion by vowing publicly to veto some unpopular bill in Congress." Kernell, Going Public, p. 60. |

| 38. |

For a depiction of the veto override process, see CRS Infographic IG10007, Presentation of Legislation and the Veto Process, by Meghan M. Stuessy. For more on the veto override procedure, see CRS Report RS22654, Veto Override Procedure in the House and Senate, by Elizabeth Rybicki. |

| 39. |

U.S. Congress, House, "Presidential Vetoes," http://history.house.gov/Institution/Presidential-Vetoes/Presidential-Vetoes/; U.S. Congress, Senate, "President Veto Counts: Summary of Bills Vetoed, 1789-present," https://www.senate.gov/reference/Legislation/Vetoes/vetoCounts.htm. |