Statements of Administration Policy

Presidents communicate their views on pending legislation in a variety of ways. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) formally communicates the Administration’s views by way of Statements of Administration Policy. Statements of Administration Policy, or SAPs, are designed to signal the Administration’s position on legislation scheduled on the House and Senate floor.

SAPs are often the first public document outlining the Administration’s views on pending legislation and allow for the Administration to assert varying levels of support for or opposition to a bill. While Administrations vary as to how frequently and how many SAPs are released, a SAP’s value comes in its ability to speak for the coordinated executive Administration as a whole.

SAPs grant the Administration the opportunity to go on record with its reasons for opposing and potentially vetoing legislation. SAPs also enable the Administration to identify key provisions of the legislation that it objects to or finds particularly favorable. SAPs may also provide Congress insights into the Administration’s position towards possible bill implementation.

When a SAP indicates that the Administration may veto a bill, it appears in one of two ways: (1) a statement indicating that the President intends to veto the bill, or (2) a statement that agencies or senior advisors would recommend that the President veto the bill. These two types indicate degrees of veto threat certainty.

Statements of Administration Policy have generally adhered to the same structure from Administration to Administration. SAPs are released concurrent with action in the House Rules Committee, or on the floor of the House or the Senate. A SAP is released at such a time in the legislative process so as to maximize the Administration’s influence in the policy outcome.

Statements of Administration Policy

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- What Are Statements of Administration Policy?

- SAP Structure and Key Components

- Example SAP Position Language

- Veto Threats

- SAP Timing Within the Legislative Process

- Statements of Administration Policy and OMB

- OMB's Mission

- Historical Development of SAPs

- Issuing Statements of Administration Policy

- Institutional Uses for SAPs

- Circular No. A-19

- Agency Involvement in the Development of Administration Views

- Timing and Possible Role of SAPs in the Legislative Process

- Receiving Statements of Administration Policy

- SAP Transmittal

- Presidential Persuasion and "Going Public"

- Statement of Administration Policy Audiences

- Congress

- The Public

- The Executive Branch

Appendixes

Summary

Presidents communicate their views on pending legislation in a variety of ways. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) formally communicates the Administration's views by way of Statements of Administration Policy. Statements of Administration Policy, or SAPs, are designed to signal the Administration's position on legislation scheduled on the House and Senate floor.

SAPs are often the first public document outlining the Administration's views on pending legislation and allow for the Administration to assert varying levels of support for or opposition to a bill. While Administrations vary as to how frequently and how many SAPs are released, a SAP's value comes in its ability to speak for the coordinated executive Administration as a whole.

SAPs grant the Administration the opportunity to go on record with its reasons for opposing and potentially vetoing legislation. SAPs also enable the Administration to identify key provisions of the legislation that it objects to or finds particularly favorable. SAPs may also provide Congress insights into the Administration's position towards possible bill implementation.

When a SAP indicates that the Administration may veto a bill, it appears in one of two ways: (1) a statement indicating that the President intends to veto the bill, or (2) a statement that agencies or senior advisors would recommend that the President veto the bill. These two types indicate degrees of veto threat certainty.

Statements of Administration Policy have generally adhered to the same structure from Administration to Administration. SAPs are released concurrent with action in the House Rules Committee, or on the floor of the House or the Senate. A SAP is released at such a time in the legislative process so as to maximize the Administration's influence in the policy outcome.

Statements of Administration Policy, or SAPs, are one of the President's communication tools designed to communicate the Administration's position on legislation coming up on the House and Senate floor. Issued by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) on behalf of the Executive Office of the President (EOP), SAPs provide the Administration's position on pending legislation. These statements can supply guideposts to Congress regarding the Administration's legislative approach to the passage and execution of a bill. A collection of all SAPs from the current presidential Administration is located at the White House OMB website.1

SAPs by design always include policy position language and are often the first formal written document indicating the President's intent to sign or veto a legislative measure. Beyond the intent to sign or veto a bill, SAPs also indicate varying levels of support or opposition to the bill in question. This report discusses the creation and use of SAPs, but does not discuss OMB's related interagency clearance procedures at length.

This report is divided into five sections. The report discusses structural components of SAPs, the development of SAPs from the Ronald Reagan Administration to the present, the coordination of executive branch actors involved in issuing SAPs, the receipt of SAPs and their impact on government institutions, and possible reactions to SAPs when they are released publicly.2

What Are Statements of Administration Policy?

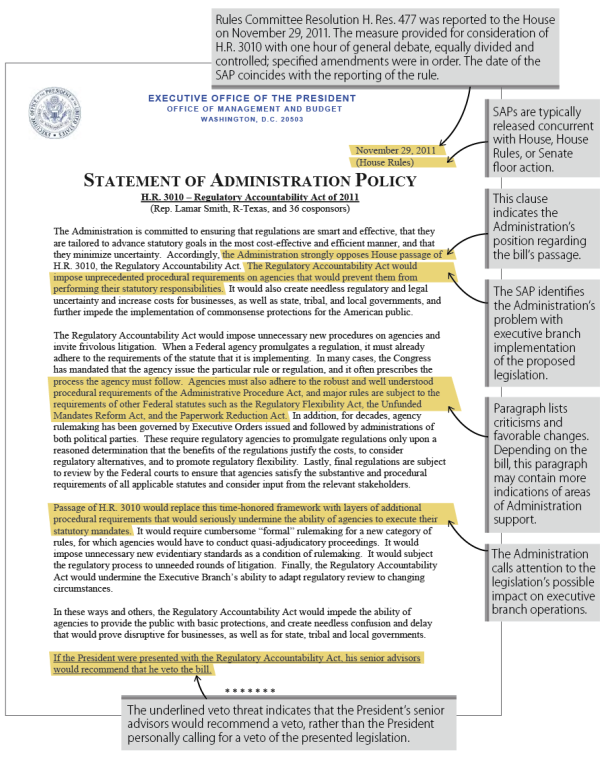

SAPs are written statements of the Administration's policy position towards a particular piece of legislation. While other avenues and forms of communication exist between Congress and the executive branch, SAPs serve as a contained summation of the Administration's positions regarding a specific bill. This section describes a SAP's structure, key components, position statements, and veto threats that may be found in SAPs.3 The report includes an example SAP in the Appendix.

SAP Structure and Key Components

In recent years, SAPs have generally adhered to the same structure from Administration to Administration. Underneath the bill title, sponsor, and number of cosponsors, the Administration will lay out its views on the bill. The George W. Bush and William J. Clinton Administrations typically addressed their position on the passage of the bill in the first paragraph of the SAP. In contrast, the Barack H. Obama Administration often has its bill position in the middle or at the very end of a SAP.

The key operative clause in all SAPs across presidencies is an expression of the Administration's opposition to or support for passage of the bill. For example, the Obama Administration writes in the included SAP in the Appendix, "Accordingly, the Administration strongly opposes House passage of H.R. 3010, the Regulatory Accountability Act."4

SAPs may also point to specific provisions within the bill text if they meet the Administration's threshold of significance.5 If such provisions are included, the Administration wants the items to be noticed by Members of Congress and likely also the public. SAPs will sometimes offer further revisions for these provisions or call for amendments, in addition to critiques of the existing bill text.

Example SAP Position Language

SAP position statements cover the spectrum from strong support of a bill, to strong opposition to bill passage, a threat to veto a bill, and all positions in between. SAPs may even include criticisms or praise of particular bill provisions. This section provides examples of the gradations of position statements contained in SAPs.

An Administration may choose to support the passage of a bill, as was the case in the Obama Administration's SAP on S. 1793, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Treatment Extension Act of 2009. The SAP reads, "The Administration strongly supports Senate passage" of S. 1793, and later identifies that the Obama Administration, in particular, "supports the provision in the legislation revising the threshold of unobligated balances that triggers penalties ... " and "strongly supports the inclusion of a provision to offset unobligated balances from subsequent grant awards rather than cancellation of unobligated amounts."6 For this particular bill, the SAP starts with a statement of strong support of bill passage and includes suggestions for bill provisions that the Obama Administration would strongly support.

Similarly, a SAP that voices opposition to a bill's passage contains a position statement and possible consequences if the bill is passed. The Obama Administration wrote, "The Administration strongly opposes House passage of H.R. 3463.... "7 Furthermore, the Obama Administration says, "H.R. 3463 would terminate the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), which was established after the 2000 Presidential election to improve the administration of elections. The EAC continues to perform crucial statutory responsibilities by serving as a national clearing house of information for election officials and the public."8 As in most SAPs, the initial position statement is supported in the body text by specific statements on the bill's projected effect.

Veto Threats

While SAPs allow for the Administration to assert varying levels of support for or opposition to a bill, perhaps the most noticeable statement in a SAP is whether the Administration intends to veto the bill. Some Members of Congress have characterized SAPs as forerunner indicators of a veto.9 Members may pay particular attention to a SAP when a veto threat is being made.10

Two types of veto threats appear in SAPs: a statement indicating that the President will veto the bill, or a statement that agencies or senior advisors would recommend that the President veto the bill. Beginning in the 108th Congress, SAPs containing veto threats have underlined the veto threat itself.11

For example, the Obama Administration issued a SAP on H.R. 2 – Repealing the Affordable Care Act. The Obama Administration wrote, "If the President were presented with H.R. 2, he would veto it."12 In contrast, the Obama Administration's SAP on H.R. 3010 – Regulatory Accountability Act of 2011 said, "If the President were presented with the Regulatory Accountability Act, his senior advisors would recommend that he veto the bill."13

A SAP indicating that the President will veto the bill, rather than indicating that the President's senior advisors will recommend a veto, may give the President less negotiation room after it is issued.14 For example, in the same Obama Administration SAP provided in the Appendix, the Administration makes its opposition to H.R. 3010 more specific by including a veto threat at the conclusion of the SAP; however, the Administration's negative position was previously indicated.

SAP Timing Within the Legislative Process

Generally, SAPs are released concurrent with action in the House Rules Committee, or on the floor of the House or Senate. Releasing a SAP at such a point in the legislative process may serve to maximize the Administration's influence. Frequently, one SAP is issued per bill. Some Administrations have preferred to issue multiple SAPs per bill throughout the legislative process as the bill text changes, while some issued the same SAP to both chambers. Some Administrations limited their use of SAPs only to bills they deemed of particular importance.

SAPs can be an important vehicle for the Administration to support or oppose particular provisions of a bill as it makes its way through the legislative process in the House and Senate. OMB wrote in a document from 2000 that, "As a general rule, only items of significant funding or policy importance are included in OMB letters and SAPs. From one perspective, complaining about a large number of minor items would tend to dilute the arguments put forward for major items of importance to the Administration."15

Statements of Administration Policy and OMB

As described in the U.S. Constitution under Article II, Section 3, the President shall recommend for Congress's consideration "such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.... "16 The Recommendations Clause, as this is known, has been viewed as the President's basis to make or respond to legislative proposals, and as the President's basis to refuse to do so even when Congress asks for such proposals.17 When Congress considers legislation, the executive branch conducts a parallel process to consider the legislation, make recommendations, and state the Administration's views.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB), in addition to assisting with the formulation of the President's budget, assists the President in creating the Administration's recommendations and comments on Congress's legislative proposals.18 Since its inception, OMB has been a source of institutional memory for executive branch operations, attempting to unify the branch both in directing its policy agenda and its program execution.

By virtue of being comprised of over 90% career civil servants that may stay beyond an individual Administration, OMB is situated to remember processes and procedures extending across many Administrations.19 Accordingly, some of OMB's processes have been developed for internal management, rather than individual Administration needs, over time. This section briefly discusses OMB's role in supervising the creation of legislative recommendations and the historical creation of SAPs.

OMB's Mission

OMB writes that its core mission is "to serve the President of the United States in implementing his vision across the Executive Branch. ... It reports directly to the President and helps a wide range of executive departments and agencies across the Federal Government to implement the commitments and priorities of the President."20 OMB provides a means for interagency consultation with the objective of forming an Administration position rather than having Congress faced with multiple agency views.21

Importantly, implementing the President's priorities includes tracking bill progress through the congressional chambers and drafting Administration proposals or criticisms in response to legislative action. This process occurs within individual executive branch agencies, however the central legislative clearance process described by Circular A-19 situates OMB in a supervisory position for the Administration.22 Bill tracking informs the central legislative clearance process,23 while SAPs and any other activity where an executive branch actor takes a position on proposed legislation are the product of the central legislative clearance process.24

Historical Development of SAPs

SAPs were an outgrowth of OMB's efforts to monitor appropriations legislation and develop the President's budget. As part of its responsibilities described in Circular A-11,25 the Budget Review Division (BRD) within OMB analyzes appropriations bills "for changes from previous configurations of the President's original budget proposals in their respective account areas and determine[s] how these squared with presidential policy."26 This analysis promotes consistency in an Administration's policy agenda.

BRD is responsible for tracking the legislative progress of appropriations bills. Bill tracking expanded during the Reagan Administration to include the formulation of statements on the Administration's position regarding individual appropriations bills.27 The bill tracking process served as the template for the SAP development process.

During the Reagan Administration, demand from the OMB Director for more sophisticated bill statements grew, resulting in statements that were prepared by various divisions within OMB at every stage of the appropriations process.28 These documents, produced by OMB's program examiners in conjunction with the OMB Director, eventually became Statements of Administration Policy.

These early iterations of SAPs were "sent to the chairs and ranking members of the full appropriations committees and subcommittees, and sometimes to the Senate leadership."29 During this period, SAPs were intended for a select audience.30 In contrast, modern SAPs are made available online to the public and all Members of Congress upon their release.31

Issuing Statements of Administration Policy

SAPs are a formal vehicle through which the President and the President's Administration comment on legislation pending before Congress. The process of solicitation and coordination of the executive branch's legislative position is governed by OMB Circular A-19. This section details the Administration's institutional uses for SAPs, discusses key provisions in Circular A-19, and describes the OMB and agency actors involved. The section concludes with strategic considerations regarding the timing of a SAP's public release.

Institutional Uses for SAPs

The process for creating SAPs is not established in statute. Consequently, implementation practices may evolve over time and may differ from one Administration to another. As mentioned previously, the earliest iterations of SAPs were internal documents released only to a select audience of those involved with the passage of specific legislation. Samuel Kernell writes that, "SAPs are, after all, fashioned for a sophisticated audience interested in discerning the gradations of objection to various provisions cover[ed] in a threat. Even slight variations in the wording of these SAPs may influence legislators' responses.... "32 In recent Administrations, SAPs are released to both legislators and the public. SAPs are created through consultation among the executive agencies, the White House Office of Legislative Affairs (WHLA), and divisions within OMB.33

The decision whether or not to issue a SAP ultimately rests with the White House. Although SAPs address administrative aspects of how legislation would be implemented if enacted, the Administration takes political considerations into account during the creation of SAPs. SAPs are drafted by career civil servants in conjunction with political appointees. The issuing of SAPs, therefore, is best understood as a collaborative process between political goals and administrative execution of policy and not as either a strictly political or an exclusively administrative process.

SAPs may offer the Administration certain advantages. SAPs allow the Administration to provide language that the President's party and the President's allies in Congress can use when negotiating policies. SAPs allow the Administration to go on record with its reasons for opposing and potentially vetoing legislation. SAPs also enable the Administration to identify key provisions of the legislation that it objects to or finds particularly favorable.34

SAP language can identify specific provisions of the legislation that the Administration finds problematic. In contrast to the President's oral statements which are often intended for audiences outside of the executive branch, SAPs also allow the Administration to describe its views on bill implementation in finer detail for an executive branch audience. These details can include whether or not provisions of legislation have been identified as areas that would be difficult to execute, either for political or managerial reasons.35 These details may also prove useful in Congress's efforts to understand possible obstacles involved in implementing the law.

Because presidents use SAPs to signal opposition to parts of a bill or to an entire bill, or to comment on implementation challenges, Congress may find these statements informative when considering the likelihood of a bill obtaining the President's signature. 36

Circular No. A-19

Last revised in 1979, Circular No. A-19 describes the procedures for legislative coordination and clearance through OMB. Circular No. A-19 describes the process behind agency recommendations on proposed, pending, and enrolled legislation.37 As a result, this circular is integral to understanding the executive branch coordination efforts required to issue SAPs.

Circular No. A-19 states, "OMB performs legislative coordination and clearance functions to (a) assist the President in developing a position on legislation, (b) make known the Administration's position on legislation for the guidance of the agencies and information of Congress, (c) assure appropriate consideration of the views of all affected agencies, and (d) assist the President with respect to action on enrolled bills."38 This extends to not only SAPs, but also draft legislation, agency testimony, and agency reports.

OMB collects views in advance of clearing proposed legislation, reports, or testimony on behalf of the Administration. Agency views indicate support, opposition, or no objections to the materials proposed for legislative clearance. 39 Positions expressed by agencies may be later used in the creation of SAPs for the President.

Agency Involvement in the Development of Administration Views

The Resource Management Offices (RMOs) of OMB consult with relevant agencies that would be affected by pending legislation, if enacted. Within OMB, RMOs are divided by policy area and department.40 Agency views are consulted throughout the SAP creation process, mainly by RMO proxy, but agency legislative affairs offices are also directly involved in SAP creation.

As an internal OMB document from 2000 explains, "In executing its responsibilities for appropriations bill tracking, BRB41 works closely with the RMOs of OMB. The RMOs, in turn, work closely with the agencies represented in a given bill to obtain their views and, as appropriate, incorporate agency views into letters and SAPs."42 Though the extent to which agency views are incorporated into executive documents can vary, the SAP creation process structurally allows for agency input.

The decision of which agencies' views to include in a SAP is made by OMB and not by the agencies. In making this decision, OMB determines whether an agency's views are critical to the creation of the Administration's position. As discussed in Circular A-19, OMB sifts through agency legislative programs43 to recommend provisions for inclusion in the President's program. Circular A-19 states that submitting agency legislative programs helps,

(1) to assist planning for legislative objectives; (2) to help agencies coordinate their legislative program with the preparation of their annual budget submissions to OMB; (3) to give agencies an opportunity to recommend specific proposals for Presidential endorsement; and (4) to aid OMB and other staff of the Executive Office of the President in developing the President's legislative program, budget, and annual and special messages.44

Here, OMB emphasizes that agencies have the opportunity for their concerns and suggestions to be expressed in the Executive Office of the President (EOP) via this coordinating function. This coordination process also holds true for the creation of SAPs. As a practical matter not all agency positions will be included in official messaging outside of the executive branch. In an internal guidance document, OMB explained,

Given the number of Executive Branch organizations and interests represented in a particular appropriations bill, it is frequently difficult to satisfy everyone's views concerning what items should be discussed in an Administration letter or SAP as well as the priority given to write-ups that are included. Ultimately, this is a judgment call made by OMB policy officials and the White House.45

For agencies, OMB emphasizes the relationship between agencies and their assigned RMOs as the proper means for agencies to voice their opinions on pending legislation. This is a function of OMB's institutional desire to preserve the executive branch's ability to speak with one voice; however in practice, agencies may reach out to Members of Congress or committee staff.46 The extent to which agencies engage in this practice highlights another difficulty the President faces in unifying the executive Administration's position.

It may be argued that multiple opinions in the Administration allows for the voicing of policy alternatives that may lead to better governance. Others argue that the Administration is most effective when executive agency opinions are coordinated into one Administration position.47 SAPs acknowledge these two views by processing disparate agency opinions on policy and eventually presenting a unified policy document intended to speak for the entire executive branch.48

Timing and Possible Role of SAPs in the Legislative Process

In order to have influence during the legislative process, OMB's internal guidance from 2000 said that SAPs must be strategically released at a time where such statements could have a maximum impact in the legislative negotiation process.49 This may impart an implicit value to SAPs, OMB noted, "in the sense of the desirability of making the Administration's position on a given issue known as early on as possible in House and Senate consideration, i.e., before the bill reaches the floor."50 By conveying the Administration's opinion early on in the process, the President may stand to gain a more favorable bill before the legislative process concludes.

While the exact timing of SAP release varies by Administration, in practice, SAPs are generally released as a bill is set for House Rules, House, or Senate floor action.51 Since the release of particular SAPs varies, OMB appears to adjust its guidance based on Administration preferences or in response to the anticipated movement of particular bills once introduced.

From an Administration's perspective, SAPs are intended to influence congressional behavior and public opinion. As a result, the Administration views the timing of SAP release to be a critical component of presidential strategy. In the interest of balancing Administrative unity and the Administration's congressional relevance, OMB stated in 2000 that SAP creation "cannot be delayed for receipt of comments from an agency. It is better that a letter or SAP be sent with available comments on time than that a comprehensive letter or SAP be sent too late to influence congressional action."52 Acknowledging that not all opinions can be included in SAPs either due to delays in receiving agency comments or shifting legislative priorities, OMB stated that such agency comments can be included in future SAPs or letters as the legislative situation develops.

Receiving Statements of Administration Policy

SAPs are strategically distributed to legislators in Congress, to executive branch agency officials whose duties may be affected by the pending legislation, and others who may assist in bringing about the President's legislative program. This section describes the evolution of SAP transmittals, the managerial implications of SAPs on the executive branch, and theoretical frameworks for understanding SAPs as one of the President's persuasion tools.

SAP Transmittal

In their earliest iterations, SAPs were shared with ranking Members, relevant committee and subcommittee members, and other allies of the Reagan Administration on the legislation in question.53 Designed to bring about legislative change, the Reagan Administration saw value in giving SAPs to those it deemed best positioned to make alterations favorable to the Administration.

Before SAPs were disseminated widely, Reagan Administration SAPs were prepared "for transmission to the appropriations committees and for [OMB Director] Stockman ... to use as ammunition in congressional negotiation sessions."54 SAPs served then as now as a quick, shorthand statement for the EOP to rely on in trying to bring about the President's agenda.

In the Internet age, SAPs are primarily transmitted to the public via the White House website under the OMB page for "Legislative Affairs" information.55 Like other presidential documents, SAPs on this page are only those issued by the current Administration.56 SAPs are divided on the site by session, by appropriation or policy bills, and appropriations by subcommittee. It is unknown if involved Members receive SAPs directly, however previously, select Members and staffers were allowed to view SAPs before their official transmittal.57

Starting in 2012, the White House has used its @OMBPress Twitter account to broadcast the transmittal of SAPs, with hyperlinks redirecting users to the main White House SAP website. These tweets include a further condensation of the Administration's position so that it satisfies Twitter's 140-character limit, providing an additional opportunity for the Administration to express its views to the public in a concise and shareable format. 58 For example, the @OMBPress Twitter account wrote: "#SAP44: Sr Adv Wld Rec Veto of H.R. 5 to Repeal IPAB; Admin Opposes Leg. That Attempts to Erode Key #ACA Provisions Http://t.co/LlW442gA," conveying the veto threat in the hyperlinked SAP for H.R. 5.59

Beyond these Internet forms of transmittal and possible physical distribution to a select audience, a Member of Congress may choose to reference part of a SAP or an entire SAP, thus making it part of the Congressional Record.

Presidential Persuasion and "Going Public"

Two of many theories describing executive branch operations can be applied to SAPs in this context of administrative tools. These two theories illustrate many moving parts within the executive branch and the challenges involved in creating SAPs.

The Richard Neustadt model of presidential persuasion suggests that the President's effectiveness rests solely within his or her ability to generate buy-in from other government actors—be they executive agencies, Congress, members of the public, etc.60 SAPs as viewed through the persuasion model can be understood as a written attempt to generate support for the President's policy agenda by making the President's position known. In this sense, too, SAPs can assuage uncertainties regarding the Administration's intent in executing the presented legislation, should it later become law. The persuasion model incorporates the idea of bargaining on legislation and highlights a SAP's capacity to serve as a starting point for legislative negotiations.

In the "going public" model of the institutional presidency, as postulated by Samuel Kernell, the President can gain support for the presidential program by appealing to the American public at large. In this model, public statements by the President regarding the Administration's legislative program may help to generate pressure on Congress by informing and involving the public in the Administration's policy agenda. SAPs in this model, due to their nature as public statements, may inform the citizenry of the Administration's policy intentions and allow the American public to adopt the Administration's views when communicating with their congressional representatives.61 In 2012, the Obama Administration began tweeting SAPs via its @OMBPress account, indicating that the Administration perceived value in publicizing the information broadly to the public via social media.

Statement of Administration Policy Audiences

SAPs summarize the Administration's position towards legislation at a fixed point in time. SAPs can supply guideposts to Congress regarding the Administration's legislative approach to the passage and execution of a bill. SAPs give the Administration the ability to point to particular amendments or clauses within the bill text if they meet a threshold of significance. The combination of these bill execution guideposts and areas highlighted as significant to the Administration may be useful to Congress in crafting their own legislative strategies.

As SAPs are released publicly via the White House website, SAPs may be analyzed in relation to three general audiences. This section details the possible implications that a SAP's release may have on congressional, public, and executive branch action.

Congress

The intended audience of SAPs is primarily Congress. SAPs are released concurrent with floor action by the congressional chambers or the House Rules Committee and are designed to inform Congress of the Administration's position towards pending legislation. However, SAPs are not released in a vacuum; the confluence of public reaction and congressional reaction to the Administration's position may create new effects and pressures on the legislative and executive relationship in their negotiation efforts.62

Because SAPs are the primary written vehicle for veto threats, Congress may find these statements particularly useful for the record they provide of Presidential positions towards legislation over time. SAPs, like veto threats, can constrain the President's and the Administration's future ability to negotiate. SAPs by design highlight specific provisions that are objectionable or viewed favorably by the Administration. By making a public statement in favor or in opposition to legislation, the President risks limiting the Administration's options later on in the negotiation process.63

Conversely, SAPs may confer an advantage to Congress by giving Members a simple method to assess Presidential attitudes towards legislation. In 1954, Richard Neustadt recognized the need for a concise method to convey the President's position:

On the bulk of this business, overburdened legislators, in committee and out, need a handy criterion for choice of measures to take up, especially when faced with technical alternatives in which they have but little vested interest. They need, as well, an inkling of Administration attitude toward the outcome: how much, if at all, does the President care?64

This criterion may come in the form of first, whether or not a SAP has been issued on a particular bill, and second, what the statement contained in the SAP indicates about the level of importance the President has given to pending legislation.

Samuel Kernell writes, "A closer inspection of the details of the threats finds that the great majority involves the President couching his threat in a proposed compromise. Typically, the threat identifies those provisions that the President objects to and suggests that their removal or alteration along specified lines would lead to his signature."65 SAPs may help Congress find areas of disagreement and possible suggestions for improvement on the bill that would garner the Administration's support of the bill.

The Public

By issuing a SAP, the Administration publicly announces its expectations for the bill. Specificity and definitiveness may serve to instill credibility in the Administration's position, while at the same time limiting the Administration's options. Should the Administration deviate from the stated position, the Administration could damage its credibility with the public and its leverage with Congress.66

Samuel Kernell notes, "For some legislation, Presidents sense they can score points in public opinion by vowing publicly to veto some unpopular bill in Congress."67 On the other hand, Presidents can lose public or congressional support should they later choose to sign legislation they previously said they would oppose or veto, or vice versa.

Furthermore, "Legislators observe the President's action and conclude that he can ill afford politically to sign a bill that fails to give him what he has demanded, or at least something pretty close."68 A President's reputation is at stake if the Administration fails to make the legislation conform to the Administration's requirements laid out in a SAP. Lending this predictability to the process early on allows for all actors involved to set expectations for legislative outcomes and possible areas of compromise throughout the process.

The Executive Branch

As previously discussed, many parts of the Administration are involved in the SAP creation process via Circular A-19. In an effort to coordinate the executive branch on behalf of the President, OMB consults with executive branch agencies regarding agency priorities and the President's priorities. From the OMB and EOP perspective, this is done to ensure consistency and continuity throughout the Administration. From an agency's perspective, this allows the agency an opportunity to advocate for measures on the agency's behalf.69

Remarking on the structure of the executive branch in 1951, observer David B. Truman wrote that the executive branch is " ... a protean agglomeration of feudalities that overlap and crisscross in an almost continual succession of changes. Some of the lines of control ... terminate in the Presidency, some in ... the legislature and some ... 'outside' the government.... "70 In an attempt to maintain consistent views throughout the Administration and the executive agencies, SAPs offer the President a process and policy documents to coordinate views as soon as legislation becomes pending.71

SAPs represent OMB's role in putting forth a unified Administration position on pending bills. This is because of the coordination process involved in SAP creation and in OMB's attempts to unify disparate agency opinions into one Administration position. Although their value to Congress regarding pending legislation is apparent in SAP statements regarding bill passage, SAP insights may also prove useful in Congress's efforts to understand executive branch operations and possible implementation of the law.

Appendix. Example SAP

|

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "Statements of Administration Policy on Non-Appropriations and Appropriations Bills," at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/legislative_sap_default. |

| 2. |

For more information about OMB, see CRS Report RS21665, Office of Management and Budget (OMB): A Brief Overview, by Clinton T. Brass and CRS Report R42633, The Executive Budget Process: An Overview, by Michelle D. Christensen. |

| 3. |

For more information on regular vetoes and pocket vetoes, see CRS Report RS22188, Regular Vetoes and Pocket Vetoes: In Brief, by Meghan M. Stuessy. |

| 4. |

Executive Office of the President, Statement of Administration Policy: H.R. 3010 – Regulatory Accountability Act of 2011, November 29, 2011 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/legislative/sap/112/saphr3010r_20111129.pdf. |

| 5. |

This report is concerned with the publically visible text in Statements of Administration Policy. However, SAPs include text that is strictly for distribution within the EOP, including resource management offices (RMOs) within OMB. This text is called "below the stars" text, as it refers to the content below the asterisks at the conclusion of SAPs. OMB explained in 2000, "Unlike certain SAPs on substantive legislation—prepared by OMB's Legislative Reference Division following procedures contained in OMB Circular No. A-1—letters and SAPs on appropriations bills do not contain so-called "below the line" information.... " Again, this refers to the slight difference in the creation of appropriations and policy SAPs within the Budget Review Division and the Legislative Reference Division OMB divisions. Below the stars information includes "explanatory comments, alternative viewpoints, statements of minor issues, and the like" and serves to inform the RMOs of potential discord within their respective agencies and policy areas, allowing for OMB to be more holistically informed of the EOP's position beyond quick political and Administrative opinions. U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Appropriations Bill Tracking: Development of Letters and Statements of Administration Policy, May 8, 2000, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 6. |

Executive Office of the President, Statement of Administration Policy: S. 1793 – Ryan White HIV/AIDS Treatment Extension Act of 2009, October 19, 2009 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/legislative/sap/111/saps1793s_20091019.pdf. |

| 7. |

Executive Office of the President, Statement of Administration Policy: H.R. 3463 – Termination of Taxpayer Financing of Presidential Election Campaigns and Termination of the Election Assistance Commission, December 1, 2011 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/legislative/sap/112/saphr3463h_20111201.pdf. |

| 8. |

Ibid. |

| 9. |

Rep. Harry Reid, Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 161, part 63 (April 29, 2015), p. S2492. |

| 10. |

When Statements of Administration Policy are referenced in the Congressional Record, Members of Congress more frequently call attention to SAPs that contain veto threats, rather than SAPs that contain statements of support for a bill. Provided are examples from the 114th Congress's first session illustrating this point. Rep. Michael Burgess, Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 161, part 173 (December 1, 2015), pp. H8658-H8660. Rep. Alcee Hastings, Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 161, part 170 (November 18, 2015), pp. H8295-H8296. Rep. Alcee Hastings, Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 161, part 63 (April 29, 2015), pp. H2512-H2513. |

| 11. |

The actual formatting change may have occurred in the 108th Congress, first session; however, this was a time of unified party rule with both chambers being Republican-controlled during the Republican Bush Administration. As a result, veto threats were infrequent. |

| 12. |

Executive Office of the President, Statement of Administration Policy: H.R. 2 – Repealing the Affordable Care Act, January 6, 2011 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/legislative/sap/112/saphr2r_20110106.pdf. |

| 13. |

Executive Office of the President, Statement of Administration Policy: H.R. 3010 – Regulatory Accountability Act of 2011, November 29, 2011 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/legislative/sap/112/saphr3010r_20111129.pdf. |

| 14. |

Richard Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents: The Politics of Leadership from Roosevelt to Reagan (New York: The Free Press, 1991), pp. 71, 76-77. Samuel Kernell, Going Public, 4th ed. (Washington: CQ Press, 2007), pp. 61-62. |

| 15. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Appropriations Bill Tracking: Development of Letters and Statements of Administration Policy, May 8, 2000, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 16. |

U.S. Constitution, Article II, Section 3. |

| 17. |

Clinton T. Brass, "Working in, and Working with, the Executive Branch," in Legislative Drafter's Deskbook: A Practical Guide, ed. Tobias A. Dorsey (Alexandria, VA: TheCapitol.Net, Inc., 2006), p. 274. |

| 18. |

For more information about the President's budget, see CRS Report R42633, The Executive Budget Process: An Overview, by Michelle D. Christensen. |

| 19. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, The Staff of the Office of Management and Budget at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/OMBstaff. |

| 20. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, The Mission and Structure of the Office of Management and Budget at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/organization_mission/. |

| 21. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, Office of Management and Budget: Evolving Roles and Future Issues, committee print, prepared by the Congressional Research Service, 99th Cong., 2nd sess., February 1986, S.Prt 99-134 (Washington: GPO, 1986), p. 170. This interagency consultation process via OMB is known as central legislative clearance and is discussed at length in pages 169-184 of this committee print. |

| 22. |

Circular A-19 is discussed at length later in this report. U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Circular No. A-19 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a019/. |

| 23. |

For more information about the central legislative clearance process, please see U.S. Congress, Senate Governmental Affairs, Office of Management and Budget: Evolving Roles and Future Issues, Central Legislative Clearance, committee print, prepared by Ronald C. Moe, the Congressional Research Service, 99th Cong., 2nd sess., February 1986, S.Prt. 99-134 (Washington: GPO, 1986), pp. 169-184. |

| 24. |

Clinton T. Brass, "Working in, and Working with, the Executive Branch," in Legislative Drafter's Deskbook: A Practical Guide, ed. Tobias A. Dorsey (Alexandria, VA: TheCapitol.Net, Inc., 2006), p. 276. |

| 25. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, In Circular No. A-11 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a11_current_year_a11_toc. |

| 26. |

Shelley Lynne Tomkin, Inside OMB: Politics and Process in the President's Budget Office (New York: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 1998), p. 153. Subsequent references to Tomkin in this report refer to this book. |

| 27. |

Tomkin, p. 152. |

| 28. |

Ibid. Within the Office of Management and Budget, the division of labor in the creation of SAPs is segmented. In addition to receiving the input of White House Office of Legislative Affairs (WHLA) and OMB Legislative Affairs, OMB's Legislative Reference Division (LRD) and Budget Review Division (BRD) take the lead on SAP creation depending on the substance of the SAP in question. Though SAPs evolved from the preliminary statements made by BRD on pending legislation, SAPs in their modern incarnation are drafted by BRD if they primarily concern appropriations legislation and by LRD if they otherwise constitute substantive legislation. It is unclear when exactly this division of labor occurred; however in practice, BRD's SAPs concerning appropriations are generally lengthier than LRD's policy SAPs. This may be due to the relative length and breadth of scope of appropriations bills. The division between LRD and BRD SAPs is reflected on the White House website containing the Administration's SAPs, where appropriations SAPs are listed on their own page. Although collaboration between LRD and BRD does occur on some SAPs, SAPs for substantive and appropriations legislation are typically created separately. |

| 29. |

Ibid. |

| 30. |

According to Tomkin, SAPs would be sent to ranking Members of the full appropriations committees and subcommittees, and sometimes to the Senate leadership during OMB Director David Stockman's tenure. Ibid. |

| 31. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "Statements of Administration Policy on Non-Appropriations and Appropriations Bills," at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/legislative_sap_default. The content of SAPs may have changed over time as a result of the changes in distribution of SAPs from a select congressional audience to the general public, however, SAPs created prior to the creation of the White House website during the Clinton Administration are difficult to locate. |

| 32. |

Samuel Kernell, "Introduction to SAPs," 2005, http://pages.ucsd.edu/~skernell/resources/Introduction-to-SAPs.pdf. p. 8. |

| 33. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Appropriations Bill Tracking: Development of Letters and Statements of Administration Policy, May 8, 2000, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 34. |

Laurie Rice, "Statements of Power: Presidential Use of Statements of Administration Policy and Signing Statements in the Legislative Process," Presidential Studies Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 4 (2010), p. 692. |

| 35. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Appropriations Bill Tracking: Development of Letters and Statements of Administration Policy, May 8, 2000, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 36. |

Ibid. |

| 37. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "1. Purpose," In Circular No. A-19 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a019/#purpose. |

| 38. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "3. Background," In Circular No. A-19 at U.S. https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a019/#background. |

| 39. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "7g. Views letters," In Circular No. A-19 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a019/#submission. |

| 40. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "OMB Organization Chart," at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/about_omb/omb_org_chart.pdf. |

| 41. |

BRB, or the Budget Review Branch, is a precursor to the Budget Review Division (BRD). |

| 42. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Appropriations Bill Tracking: Development of Letters and Statements of Administration Policy, May 8, 2000, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 43. |

An agency's legislative program may include all items of legislation that the agency wishes to propose to Congress, a list of active proposals under agency consideration, and a list of all laws or provisions of law set to expire within a set time period from submission of the agency's legislative program. Circular A-19 enumerates an agency's program content at U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "6: Agency legislative programs" In Circular No. A-19 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a019/#agency. |

| 44. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "6b: Agency legislative programs" In Circular No. A-19 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a019/#agency. |

| 45. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Appropriations Bill Tracking: Development of Letters and Statements of Administration Policy, May 8, 2000, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 46. |

Ibid., pp. 2-5. |

| 47. |

During the constitutional convention, extended debates were had concerning whether the executive power of the government should be vested in a singular executive or an executive council. Speaking to the disadvantages of multiple views in the executive in Federalist 70, Alexander Hamilton argued: " ... the mere diversity of views and opinions would alone be sufficient to tincture the exercise of the executive authority with a spirit of habitual feebleness and dilatoriness." The process of coordinating executive communications, including SAPs, is a current way that presidents attempt to mitigate the diversity of views within their Administration. Alexander Hamilton, "Federalist No. 70," in The Federalist, by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay (Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co., 2005), p. 377. |

| 48. |

The process for coordinating agency views on policies is governed by Circular A-19. U.S. Office of Management and Budget, In Circular No. A-19, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a019. |

| 49. |

Ibid., p. 5. |

| 50. |

Ibid., p. 1. |

| 51. |

Ibid. |

| 52. |

Ibid., p. 5. |

| 53. |

Tomkin, p. 152. |

| 54. |

Ibid., p. 156. |

| 55. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "Statements of Administration Policy on Non-Appropriations and Appropriations Bills," at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/legislative_sap_default. |

| 56. |

Historical SAPs can be found on archived versions of the White House website. The Presidency Project from University of California: Santa Barbara also maintains an archive of SAPs at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/saps.php. |

| 57. |

Tomkin, p. 152. |

| 58. |

This is especially reflected in the use of Twitter hashtags to associate SAPs with the Presidency, as seen in "#SAP44" and attempts to condense the phrase "Senior Advisors would recommend a veto" to "Sr Adv Wld Rec Veto." U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "@OMBPress, #SAP44: Sr Adv Wld Rec Veto of H.R. 5 to Repeal IPAB; Admin Opposes Leg. That Attempts to Erode Key #ACA Provisions Http://t.co/LlW442gA," Twitter.com, March 20, 2012, at https://twitter.com/OMBPress/status/182191205789089793. |

| 59. |

While SAPs may be read by Members of Congress, their acknowledgement of a SAP can only be proven when a Member references a SAP thus making it part of the Congressional Record. For example, Sen. Harry Reid, "The Budget," remarks in the Senate, Congressional Record, daily edition, April 29, 2015, p. S2493. |

| 60. |

Richard Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents: The Politics of Leadership from Roosevelt to Reagan (New York: The Free Press, 1991), p. 11. |

| 61. |

Samuel Kernell, Going Public, 4th ed. (Washington: CQ Press, 2007), p. 50. |

| 62. |

Samuel Kernell, Going Public, 4th ed. (Washington: CQ Press, 2007), pp. 61-62. |

| 63. |

Ibid., p. 65. |

| 64. |

Richard Neustadt, "Presidency and Legislation: The Growth of Central Clearance," American Political Science Review Vol. 48, No. 3 (1954), p. 670. |

| 65. |

Ibid., p. 63. |

| 66. |

Ibid., p. 65. |

| 67. |

Samuel Kernell, Going Public, 4th ed. (Washington: CQ Press, 2007), p. 60. |

| 68. |

Ibid. |

| 69. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Appropriations Bill Tracking: Development of Letters and Statements of Administration Policy, May 8, 2000, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 70. |

Richard Neustadt, "Presidency and Legislation: The Growth of Central Clearance," American Political Science Review Vol. 48, No. 3 (1954), p. 669. |

| 71. |

Samuel Kernell, Going Public, 4th ed. (Washington: CQ Press, 2007), pp. 62-64. |