The Office of Technology Assessment: History, Authorities, Issues, and Options

Congress established the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) as a legislative branch agency by the Office of Technology Assessment Act of 1972 (P.L. 92-484). OTA was created to provide Congress with early indications of the probable beneficial and adverse impacts of technology applications. OTA’s work was to be used as a factor in Congress’ consideration of legislation, particularly with regard to activities for which the federal government might provide support for, or management or regulation of, technological applications.

The agency operated for more than two decades, producing approximately 750 full assessments, background papers, technical memoranda, case studies, and workshop proceedings spanning a wide range of topics. In 1995, amid broader efforts to reduce the size of government, Congress eliminated funding for the agency. Although the agency ceased operations, the statute authorizing OTA’s establishment, structure, functions, duties, powers, and relationships to other entities (2 U.S.C. §§471 et seq.) was not repealed. Since OTA’s defunding, there have been several attempts to reestablish OTA or to create an OTA-like function for Congress.

During its years of operations, OTA was both praised and criticized by some Members of Congress and outside observers. Many found OTA’s reports to be comprehensive, balanced, and authoritative; its assessments helped shaped public debate and laws in national security, energy, the environment, health care and other areas. Others identified a variety of shortcomings. Some critics asserted that the time it took for OTA to define a report, collect information, gather expert opinions, analyze the topic, and issue a report was not consistent with the fast pace of legislative decisionmaking. Others asserted that some of OTA’s reports exhibited bias and that the agency was responsive only to a narrow constituency in Congress, that reports were costly and not timely, that there were insufficient mechanisms for public input, and that the agency was inconsistent in its identification of ethical and social implications of developments in science and technology. In debate leading to OTA’s defunding, a central assertion of its critics was that the agency duplicated the work of other federal agencies and organizations. Those holding this position asserted that other entities could take on the technology assessment function if directed to do so by Congress. Among the entities identified for this role were the Government Accountability Office (then the General Accounting Office), the Congressional Research Service, the National Academies, and universities.

Congress has multiple options for addressing its technology assessment needs. Congress could opt to reestablish OTA by appropriating funds for the agency’s operation, potentially including guidance for its reestablishment in the form of report language. If it pursues this option, Congress would need to reestablish two related statutorily mandated organizations: the Technology Assessment Board (TAB), OTA’s bipartisan, bicameral oversight body; and the Technology Assessment Advisory Council (TAAC), OTA’s external advisory body. In 2019, the House included $6.0 million for OTA in the House-passed version of the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 2020 (H.R. 2779); no funding was provided in the final act. Congress might also opt to amend OTA’s authorizing statute to address perceived shortcomings; to revise its mission, organizational structure, or process for initiation of technology assessments; or to make other modifications or additions.

Alternatively, Congress could choose to create or develop an existing technology assessment capability in another legislative branch agency, such as the Government Accountability Office (GAO) or Congressional Research Service. Since FY2002, Congress has directed GAO to bolster its technology assessment capabilities. From 2002 to 2019, GAO produced 16 technology assessments. In 2019, GAO, at the direction of Congress, created a new office, Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics (STAA), and announced plans to increase the number of STAA analysts over time from 49 to 140.

In addition, Congress could increase its usage of the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine by funding an expanded number of congressionally mandated technology assessments. Alternatively, Congress could opt to take no action and instead rely on current sources of information—governmental and nongovernmental—to meet its needs.

In 2018, Congress directed CRS to contract with the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) for a study to “assess the potential need within the Legislative Branch to create a separate entity charged with the mission of providing nonpartisan advice on issues of science and technology. Furthermore, the study should also address if the creation of such entity duplicates services already available to Members of Congress.” The NAPA study recommended bolstering the science and technology policy efforts of CRS and GAO, as well as the establishment of an Office of the Congressional Science and Technology Advisor (OCSTA) and a coordinating council. NAPA stated that it did not evaluate the option of reestablishing OTA due to Congress’ efforts since 2002 to build a technology assessment capability within GAO.

The Office of Technology Assessment: History, Authorities, Issues, and Options

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Overview of Science and Technology Advice to Policymakers

- The Office of Technology Assessment

- Statutory Organization and Authorities

- Structure, Functions, and Duties

- Powers

- Technology Assessment Board

- Director, Deputy Director, and Other Staff

- Initiation of Technology Assessment Activities

- Technology Assessment Advisory Council

- Services and Assistance from CRS and GAO

- Coordination with the National Science Foundation

- Information Disclosure

- Other

- Funding

- Staffing

- Observations on OTA's Design and Operations

- Uniqueness and Duplication

- Timeliness

- Quality and Utility

- Objectivity

- Costs

- Public Input

- Other Criticisms

- Congressional Perspectives on Technology Assessment Expressed During OTA Defunding Debate

- Congress, GAO, and Technology Assessment

- National Academy for Public Administration Study on Congress's Need for Additional Science and Technology Advice and Technology Assessment

- Congress's Charge to NAPA

- Assessment of Congressional Need for Additional Science and Technology Advice and Resources Available

- Members of Congress

- Committee Staff

- Personal Staff

- Options Identified by NAPA

- NAPA Recommendations

- Technology Assessment and Horizon Scanning

- NAPA Evaluation of Whether to Reestablish OTA

- Other Perspectives and Recommendations on OTA and the Adequacy of S&T Advice to Congress

- Options for Congress

- Option: Reestablish OTA Without Changes to Its Statute

- Option: Reestablish OTA with Changes to Its Statute

- Option: Charge an Existing Agency or Agencies with New or Expanded Technology Assessment Authorities and Duties

- Expand the Government Accountability Office's Technology Assessment Function

- Create a Technology Assessment Function in the Congressional Research Service

- Option: Use the National Academies for Technology Assessment

- Option: Rely on a Broad Range of Existing Organizations for Scientific and Technical Analysis and Technology Assessment

- Science and Technology Advice to Congress: Identifying Needs and Avoiding Duplication in Meeting Them

Figures

- Figure 1. OTA Appropriations, FY1974-FY1996

- Figure 2. OTA Appropriations, FY1974-FY1996

- Figure 3. OTA Staffing Levels

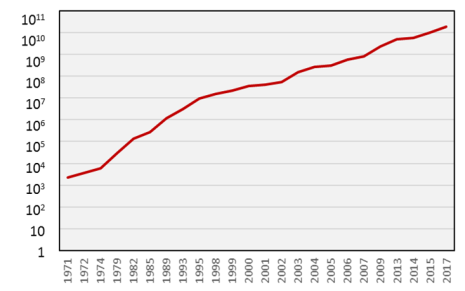

- Figure B-1. Number of Transistors on a Microchip

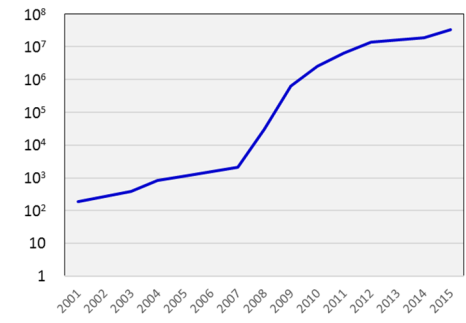

- Figure B-2. Number of Human Genome Base Pairs Sequenced per Dollar

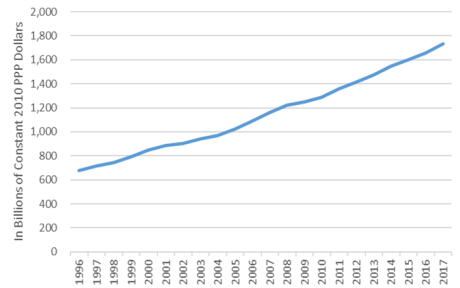

- Figure B-3. Total Global Gross Expenditures on Research and Development, 1996-2017

- Figure B-4. Annual Utility Patents Granted by U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

Appendixes

- Appendix A. An Historical Overview of the Definition of Technology Assessment

- Appendix B. Selected Trends and Factors That May Contribute to a Perceived Need for Technology Assessment

- Appendix C. OTA/Technology Assessment-Related Legislation in the 107th-116th Congresses

- Appendix D. GAO Technology Assessments

Summary

Congress established the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) as a legislative branch agency by the Office of Technology Assessment Act of 1972 (P.L. 92-484). OTA was created to provide Congress with early indications of the probable beneficial and adverse impacts of technology applications. OTA's work was to be used as a factor in Congress' consideration of legislation, particularly with regard to activities for which the federal government might provide support for, or management or regulation of, technological applications.

The agency operated for more than two decades, producing approximately 750 full assessments, background papers, technical memoranda, case studies, and workshop proceedings spanning a wide range of topics. In 1995, amid broader efforts to reduce the size of government, Congress eliminated funding for the agency. Although the agency ceased operations, the statute authorizing OTA's establishment, structure, functions, duties, powers, and relationships to other entities (2 U.S.C. §§471 et seq.) was not repealed. Since OTA's defunding, there have been several attempts to reestablish OTA or to create an OTA-like function for Congress.

During its years of operations, OTA was both praised and criticized by some Members of Congress and outside observers. Many found OTA's reports to be comprehensive, balanced, and authoritative; its assessments helped shaped public debate and laws in national security, energy, the environment, health care and other areas. Others identified a variety of shortcomings. Some critics asserted that the time it took for OTA to define a report, collect information, gather expert opinions, analyze the topic, and issue a report was not consistent with the fast pace of legislative decisionmaking. Others asserted that some of OTA's reports exhibited bias and that the agency was responsive only to a narrow constituency in Congress, that reports were costly and not timely, that there were insufficient mechanisms for public input, and that the agency was inconsistent in its identification of ethical and social implications of developments in science and technology. In debate leading to OTA's defunding, a central assertion of its critics was that the agency duplicated the work of other federal agencies and organizations. Those holding this position asserted that other entities could take on the technology assessment function if directed to do so by Congress. Among the entities identified for this role were the Government Accountability Office (then the General Accounting Office), the Congressional Research Service, the National Academies, and universities.

Congress has multiple options for addressing its technology assessment needs. Congress could opt to reestablish OTA by appropriating funds for the agency's operation, potentially including guidance for its reestablishment in the form of report language. If it pursues this option, Congress would need to reestablish two related statutorily mandated organizations: the Technology Assessment Board (TAB), OTA's bipartisan, bicameral oversight body; and the Technology Assessment Advisory Council (TAAC), OTA's external advisory body. In 2019, the House included $6.0 million for OTA in the House-passed version of the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 2020 (H.R. 2779); no funding was provided in the final act. Congress might also opt to amend OTA's authorizing statute to address perceived shortcomings; to revise its mission, organizational structure, or process for initiation of technology assessments; or to make other modifications or additions.

Alternatively, Congress could choose to create or develop an existing technology assessment capability in another legislative branch agency, such as the Government Accountability Office (GAO) or Congressional Research Service. Since FY2002, Congress has directed GAO to bolster its technology assessment capabilities. From 2002 to 2019, GAO produced 16 technology assessments. In 2019, GAO, at the direction of Congress, created a new office, Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics (STAA), and announced plans to increase the number of STAA analysts over time from 49 to 140.

In addition, Congress could increase its usage of the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine by funding an expanded number of congressionally mandated technology assessments. Alternatively, Congress could opt to take no action and instead rely on current sources of information—governmental and nongovernmental—to meet its needs.

In 2018, Congress directed CRS to contract with the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) for a study to "assess the potential need within the Legislative Branch to create a separate entity charged with the mission of providing nonpartisan advice on issues of science and technology. Furthermore, the study should also address if the creation of such entity duplicates services already available to Members of Congress." The NAPA study recommended bolstering the science and technology policy efforts of CRS and GAO, as well as the establishment of an Office of the Congressional Science and Technology Advisor (OCSTA) and a coordinating council. NAPA stated that it did not evaluate the option of reestablishing OTA due to Congress' efforts since 2002 to build a technology assessment capability within GAO.

Introduction

Congress established the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) in October 1972 in the Technology Assessment Act of 1972 (P.L. 92-484) to provide

competent, unbiased information concerning the physical, biological, economic, social, and political effects of [technological] applications" [to be used as a] "factor in the legislative assessment of matters pending before the Congress, particularly in those instances where the Federal Government may be called upon to consider support for, or management or regulation of, technological applications.1

The agency operated for more than two decades, producing approximately 750 full assessments, background papers, technical memoranda, case studies, and workshop proceedings. In 1995, amid broader efforts to reduce the size of government, Congress eliminated funding for the operation of the agency. Congress appropriated funding for FY1996 "to carry out the orderly closure" of OTA. Although the agency ceased operations, the statute authorizing OTA's establishment, structure, functions, duties, powers, and relationships to other entities was not repealed.2

Since OTA's defunding, some Members of Congress, science and technology advocates, and others have sought to reestablish OTA or to establish similar analytical functions in another agency or nongovernmental organization. This report describes the OTA's historical mission, organizational structure, funding, staffing, operations, and perceived strengths and weakness. The report concludes with a discussion of issues and options surrounding reestablishing the agency or its functions. The report also includes three appendices. Appendix A provides a historical overview of discussions about the definition of "technology assessment," a topic fundamental to OTA's mission and to any organization that would seek to fulfill OTA's historic role. Appendix B describes selected trends and factors that may contribute to a perceived need for technology assessment. Appendix C provides a history of legislative efforts to reestablish OTA or its functions since the agency was defunded. Appendix D provides a list of technology assessment products produced from 2002 to 2019 by the Government Accountability Office (GAO). Congress's guidance to GAO on technology assessment during this period is provided in the section "Congress, GAO, and Technology Assessment."

Overview of Science and Technology Advice to Policymakers

Groundbreaking emerging technologies—in fields such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing, gene editing, hypersonics, autonomy, and nanotechnology—are widely anticipated to have substantial economic and social impacts, affecting the ways people work, travel, learn, live, and engage with others and the surrounding world. The impacts are likely to be felt by people of all ages, across most industries, and by government. Science, technology, and innovation have been of interest to government leaders throughout the nation's history. The federal government has looked to people and organizations with expertise in the development and application of new technologies to gain insights into their implications and potential public policy responses—both to accelerate and maximize their expected benefits and to reduce or eliminate expected adverse effects. Such policies may include, among other things

- the funding of research and development (R&D) to accelerate the arrival and deployment of technologies and to identify their uses and potential implications;

- infrastructure policies, such as "smart" highways and cities, focused on creating environments where new technologies can flourish;

- regulations to guide and govern the development and use of technologies to ensure human health and public safety and to protect the environment;

- tax policies and other incentives to encourage investment in technology development and adoption;

- trade policies to maximize the global economic and societal potential of new technologies by fostering market access and eliminating tariff and nontariff barriers;

- intellectual property policies to protect the interests of those investing in technology development and commercialization; and

- education and training programs to promote U.S. leadership in innovation and ensure the adequacy of the science and technology workforce, as well as to help those who are displaced by new technologies to attain the knowledge and skills needed for other jobs.

In some cases, a specific science or technology outcome may be the primary objective of a proposed policy, while in other cases science and technology may play a role in a broader policy effort to achieve other societal goals, such as environmental quality, public health and safety, economic competitiveness, or national security. Science and technology activities, programs, and sectors can be affected by tradeoffs resulting from multiple policy objectives. For example, U.S. trade policy for high technology goods and services may involve complementary and competing policy objectives related to intellectual property protection, expansion of markets, protection of U.S. national security, and advancement of geopolitical objectives.

U.S. government efforts to obtain guidance on scientific and technical issues and their policy implications extend back to the nation's founding. Some of these efforts were informal, with Presidents, Members of Congress, and executive branch officials seeking out insights of knowledgeable individuals on an ad hoc basis.

Presidents and congressional leaders also relied on more formal advice from scientific and technical societies, and business and professional organizations for insights and guidance on science, technology, and innovation-related issues. A number of organizations and their members helped fill this role in the early years of the country's development, including the American Philosophical Society, co-founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1743; the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, founded in 1780 in Boston, whose charter members included John Adams and Samuel Adams; the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, founded in 1812; the Smithsonian Institution, established by an act of Congress in 1846;3 and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, founded in 1848.

In 1863, Congress chartered the National Academy of Sciences and directed that "the academy shall, whenever called upon by any department of the Government, investigate, examine, experiment, and report upon any subject of science or art, the actual expense of such investigations, examinations, experiments, and reports to be paid from appropriations which may be made for the purpose, but the Academy shall receive no compensation whatever for any services to the Government of the United States."4 Three related entities were subsequently formed to complement the knowledge and capabilities of the National Academy of Sciences: the National Academy of Engineering,5 the National Academy of Medicine,6 and the National Research Council.7 These four organizations are collectively referred to as the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) or simply, the National Academies. They are nonprofit, nongovernmental entities.

In addition, throughout the 20th century, Congresses and Presidents, using statutory and executive authorities, respectively, established executive branch organizations to provide scientific insight and advice to the President, as well as informing Congress and federal departments and agencies. Advisory and coordinating organizations included the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA, est. 1915),8 the Science Advisory Committee (SAC, est. 1951),9 the President's Science Advisory Committee (PSAC, est. 1956),10 the Intergovernmental Science, Engineering, and Technology Panel (ISETAP, est. 1976),11 the President's Committee on Science and Technology (PCST, est. 1976),12 and the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST, est. 1990).13 Other organizations were established in statute. For example, the National Science Board (NSB, which oversees the National Science Foundation) was established by the National Science Foundation Act of 1950; a key statutory mandate of the NSB is to "render to the President and to the Congress reports on specific, individual policy matters related to science and engineering and education in science engineering, as Congress or the President determines the need for such reports."14 In addition, many science and technology agencies in the executive branch have deep expertise across a wide spectrum of technologies; several of these have policy-oriented offices or programs.

While Congress had its own science and technology advisory resources—including the Congressional Research Service (CRS) and the General Accounting Office (GAO, now the Government Accountability Office )—prior to the establishment of OTA, many federal science and technology advisory organizations and agencies were under the authority and direction of the President.15 Accordingly, during the decade preceding the establishment of OTA, a number of lawmakers expressed a need for Congress to have its own agency to conduct detailed science and engineering analyses and provide information tailored to legislative needs and the legislative process—to supplement the functions performed by GAO and CRS.16 For example, in a 1963 hearing, Representative George Miller, chairman of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, stated

We are concerned with whether or not hasty decisions are handed down to us, but one of our difficulties is how to evaluate these decisions. We have to take a great deal on faith. We are not scientists … [but] I want to say that in our system of government we have our responsibility. We are not the rubber stamps of the administrative branch of Government… [We] recognize our responsibility to the people and the necessity for making some independent judgments … [but] we do not particularly have the facilities nor the resources that the executive department of the government has.17

In August 1963, Senator Edward L. Bartlett, introduced a bill to establish in the legislative branch a congressional Office of Science and Technology:

The scientific revolution proceeds faster and faster … and the President, in requesting authority for these vast scientific programs undertaken by the Government,… has available to him the full advice and counsel of the scientific community…. The Congress has no such help. The Congress has no source of independent scientific wisdom and advice. Far too often congressional committees for expert advice rely upon the testimony of the very scientists who have conceived the program, the very scientists who will spend the money if the program is authorized and appropriated for.… Congress as a body must equip itself to legislate on technological matters with coherence and comprehension.18

In December 1963, Senator Bartlett testified at a hearing of the Committee on House Administration Subcommittee on Accounts on the establishment of a congressional science advisory staff:

Faceless technocrats in long, white coats are making decisions today which rightfully and by law should be made by the Congress. These decisions dealing with the allocation of our scientific and technical resources must be made…. I think the Congress should make these decisions. I think they should be made in a rational manner. I think they should be made by an informed legislature which understands the implications, the costs, and the priorities of its judgments.

Similarly, in a 1970 hearing of the House Subcommittee on Science, Research, and Development on H.R. 17046 (91st Congress), a bill to establish OTA, subcommittee chair Representative Emilio Daddario stated

This Subcommittee has recognized a need to pay more attention to the technological content of legislative issues. Since 1963, a large portion of the Subcommittee efforts have been to develop avenues of information and advice for the Congress with outside groups, We have recognized the important need for developing Independent means of obtaining necessary and relevant technological Information for the Congress, without having to depend almost solely on the Executive Branch. In my view, it is only with this capability that Congress can assure its role as an equal branch in our Federal structure.19

During the 1972 House debate on establishing OTA, Representative Chuck Mosher reiterated the need for Congress to have its own science and technology advisory responsive solely to Members of Congress and congressional committees:

Let us face it, Mr. Chairman, we in the Congress are constantly outmanned and outgunned by the expertise of the executive agencies. We desperately need a stronger source of professional advice and information, more immediately and entirely responsible to us and responsive to the demands of our own committees, in order to more nearly match those resources in the executive agencies.

Many, perhaps most, of the proposals for new or expanding technologies come to us from the executive branch; or at least it is the representatives of those agencies who present expert testimony to us concerning such proposals. We need to be much more sure of ourselves, from our own sources, to properly challenge the agency people, to probe deeply their advice, to more efficiently force them to justify their testimony—to ask sharper questions, demand more precise answers, to pose better alternatives.20

Peter Blair, author of Congress' Own Think Tank: Learning from the Legacy of the Office of Technology Assessment, asserts that this perspective contributed to the establishment of OTA and other congressional science and technology analytical functions:

[Many] viewed the creation of OTA, as well as the subsequent creation of CBO, and the expansion of [the Congressional Research Service] and [General Accounting Office]21 at around the same time, as part of a congressional reassertion of authority responding to Richard Nixon's presidency.22

While advocates for the creation of OTA asserted that its functions would be complementary to GAO and CRS, others expressed concerns about the costs of setting up another bureaucracy and suggested that the roles envisioned for OTA might be done by the existing agencies, perhaps at a lower cost. Some proposed, instead, that the functions intended for OTA be given to CRS or GAO.23

The Office of Technology Assessment

For several years in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Congress explored and deliberated on the need for, and value of, technology assessment as an aid in policymaking decisions. In 1972, Congress enacted the Technology Assessment Act of 1972 (P.L. 92-484, codified at 2 U.S.C. §§471 et seq.), establishing the Office of Technology Assessment as a legislative branch agency.

The meaning of the term "technology assessment" is fundamental to the types of research and analysis that OTA or a successor organization might perform. There is no single authoritative definition of the term. In practice, an implicit definition is provided in the Technology Assessment Act of 1972:

The basic function of the Office shall be to provide early indications of the probable beneficial and adverse impacts of the applications of technology and to develop other coordinate information which may assist the Congress.24

In the act, Congress found and declared that technological applications were "large and growing in scale; and increasingly extensive, pervasive, and critical in their impact, beneficial and adverse, on the natural and social environment." Accordingly, Congress deemed it "essential that, to the fullest extent possible, the consequences of technological applications be anticipated, understood, and considered in determination of public policy on existing and emerging national problems."25

Further, Congress found that existing legislative branch agencies were not designed to provide Congress with independently developed, adequate, and timely information related to the potential impact of technological applications.

For these reasons, Congress authorized the establishment of OTA to "equip itself with new and effective means for securing competent, unbiased information concerning the physical, biological, economic, social, and political effects of such applications." The information provided by OTA would serve "whenever appropriate, as one factor in the legislative assessment of matters pending before the Congress, particularly in those instances where the Federal Government may be called upon to consider support for, or management or regulation of, technological applications."26

In assigning functions, duties, and powers to OTA, Congress further refined its concept of technology assessment; these are described later in this report. For a discussion of the history and varying perspectives on the meaning of the term, see Appendix A.

Statutory Organization and Authorities

As previously noted, the authorization for OTA's existence, structure, and functions remains in effect. This section provides an overview of OTA's structure, function and duties, powers, components and related organizations, and other information, as articulated in the agency's organic statute and codified at 2 U.S.C. §§471-481. Because these authorities remain in effect, despite the fact that OTA itself no longer exists, this section describes the authorities using the present tense.

Structure, Functions, and Duties

The Technology Assessment Act of 1972 authorizes the establishment of an Office of Technology Assessment, composed of a Director and a Technology Assessment Board (TAB). The TAB is to "formulate and promulgate the policies" for OTA to be carried out by the Director.27

OTA's functions and duties include

- identifying existing or probable impacts of technology or technological programs;

- ascertaining cause-and-effect relationships, where possible;

- identifying alternative technological methods of implementing specific programs;

- identifying alternative programs for achieving requisite goals;

- making estimates and comparisons of the impacts of alternative methods and programs;

- presenting findings of completed analyses to the appropriate legislative authorities;

- identifying areas where additional research or data collection is required to provide adequate support for its assessments and estimates; and

- undertaking such additional associated activities as directed by those authorized to initiate assessments (see below).28

Powers

The statute authorizes OTA "to do all things necessary" to carry out its functions and duties including, but not limited to

- making full use of competent personnel and organizations outside of OTA, public or private, and forming special ad hoc task forces or making other arrangements when appropriate;

- entering into contracts or other arrangements for the conduct of the work of OTA with any agency of the United States, with any state, territory, or possession, or with any person, firm, association, corporation, or educational institution;

- making advance, progress, and other payments which relate to technology assessment;

- accepting and utilizing the services of voluntary and uncompensated personnel necessary for the conduct of the work of OTA and providing transportation and subsistence for persons serving without compensation;

- acquiring by purchase, lease, loan, or gift, and holding and disposing of by sale, lease, or loan, real and personal property necessary for exercising the OTA's authority; and

- prescribing such rules and regulations as it deems necessary governing the operation and organization of OTA.29

The act also authorizes OTA "to secure directly from any executive department or agency information, suggestions, estimates, statistics, and technical assistance for the purpose of carrying out its functions." It also requires executive departments and agencies to furnish such information, suggestions, estimates, statistics, and technical assistance to OTA upon its request.30

Other provisions prohibit OTA from operating any laboratories, pilot plants, or test facilities,31 and authorize the head of any executive department or agency to detail personnel, with or without reimbursement, to assist OTA in carrying out its functions.32

Technology Assessment Board

Under the act, the Technology Assessment Board (TAB) is to consist of 13 members: six Senators (three from the majority party and three from the minority party), six Members of the House of Representatives (three from the majority party and three from the minority party), and the OTA Director. The Director is to be a nonvoting member. The Senate members are to be appointed by the President pro tempore of the Senate; House members are to be appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives.

The act authorizes the TAB to "formulate and promulgate the policies" of OTA. It also authorizes the TAB, upon majority vote, to "require by subpoena or otherwise the attendance of such witnesses and the production of such books, papers, and documents, to administer such oaths and affirmations, to take such testimony, to procure such printing and binding, and to make such expenditures, as it deems advisable." It authorizes the TAB to make rules for its organization and procedures and authorizes any voting member of the TAB to administer oaths or affirmations to witnesses.

The chair and vice chair of the TAB are to alternate between the House and Senate each Congress. During each even-numbered Congress, the chair is to be chosen from the House members of the TAB, and the vice chair is to be chosen from the Senate members. In each odd-numbered Congress, the chair is to be chosen from the Senate members of the TAB, and the vice chair is to be chosen from among the House members.

No TAB was established after the 104th Congress. The House did not formally appoint members in the 104th Congress, but Senate membership in the TAB was continuous and therefore the Senate members served as OTA's board until the agency ceased operations in 1995.33

Director, Deputy Director, and Other Staff

Under the act, the TAB is to appoint the OTA Director for a term of up to six years. The act authorizes the Director to exercise the powers and duties provided for in the act, as well as such powers and duties as may be delegated to the Director by the TAB. The TAB has the authority to remove the Director prior to the end of the six-year term.

The act authorizes the Director to appoint a Deputy Director. The Director and the Deputy Director are prohibited from engaging in any other business, vocation, or employment; nor is either allowed to hold any office in, or act in any capacity for, any organization, agency, or institution with which OTA contracts or otherwise engages.34

The Director is to be paid at level III of the Executive Schedule and the Deputy Director is to be paid at level IV.35 The act authorizes the Director to appoint and determine the compensation of additional personnel to carry out the duties of OTA, in accordance with policies established by the TAB.36

Initiation of Technology Assessment Activities

Under the act, OTA may conduct technology assessments only at the request of

- the chair of any standing, special, or select committee of either chamber of Congress, or of any joint committee of the Congress, acting on his or her own behalf or at the request of either the ranking minority member or a majority of the committee members;

- the TAB; or

- the Director, in consultation with the TAB.37

Technology Assessment Advisory Council

Under the act, OTA is to establish a Technology Assessment Advisory Council (TAAC). The TAAC shall, upon request by the TAB, review and make recommendations to the TAB on activities undertaken by OTA; review and make recommendations to the TAB on the findings of any assessment made by or for OTA; and undertake such additional related tasks as the TAB may direct.38

Under the act, the TAAC is to be composed of 12 members:

- 10 members from the public, to be appointed by the TAB, who are to be persons "eminent in one or more fields of the physical, biological, or social sciences or engineering or experienced in the administration of technological activities, or who may be judged qualified on the basis of contributions made to educational or public activities";

- the Comptroller General, who heads GAO; and

- the Director of the Congressional Research Service.39

The public members of the TAAC are to be appointed to four-year terms. They are to receive compensation for each day engaged in the actual performance of TAAC duties at the highest rate of basic pay in the General Schedule. The law authorizes reimbursement of travel, subsistence, and other necessary expenses for all TAAC members.40

Under the act, a TAAC member appointed from the public may be reappointed for a second term, but may not be appointed more than twice. The TAAC is to select its chair and vice chair from among its appointed members.41 The terms of TAAC members are to be staggered, according to a method devised by the TAB.42

Services and Assistance from CRS and GAO

The act authorizes the Librarian of Congress to make available to OTA such services and assistance of the Congressional Research Service as are appropriate and feasible, including, but not limited to, all of the services and assistance which CRS is otherwise authorized to provide to Congress. The Librarian is authorized to establish within CRS such additional divisions, groups, or other organizational entities as necessary for this purpose. Services and assistance made available to OTA by CRS may be provided with or without reimbursement from OTA, as agreed upon by the TAB and the Librarian.43

Similarly, the act directs the Government Accountability Office to provide to OTA financial and administrative services (including those related to budgeting, accounting, financial reporting, personnel, and procurement) and such other services. Such services and assistance to OTA include, but are not limited to, all of the services and assistance that GAO is otherwise authorized to provide to Congress. Services and assistance made available to OTA by GAO may be provided with or without reimbursement from OTA, as agreed upon by the TAB and the Comptroller General.44

Coordination with the National Science Foundation

Under the act, OTA is to maintain a continuing liaison with the National Science Foundation with respect to grants and contracts for purposes of technology assessment, promotion of coordination in areas of technology assessment, and avoidance of unnecessary duplication or overlapping of research activities in the development of technology assessment techniques and programs.45

Information Disclosure

The act requires that OTA assessments—including information, surveys, studies, reports, and related findings—shall be made available to the initiating committee or other appropriate committees of Congress. In addition, the act authorizes the public release of any information, surveys, studies, reports, and findings produced by OTA, except when doing so would violate national security statutes or when the TAB deems it necessary or advisable to withhold such information under the exemptions provided by the Freedom of Information Act.46

Other

The act requires OTA's contractors and certain other parties to maintain books and related records needed to facilitate an effective audit in such detail and in such manner as shall be prescribed by OTA. These books and records (and related documents and papers) are to be available to OTA and the Comptroller General, or their authorized representatives, for audits and examinations.47

Funding

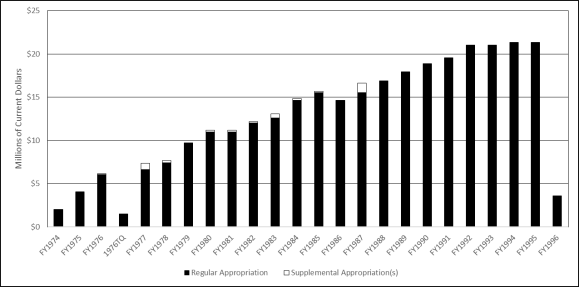

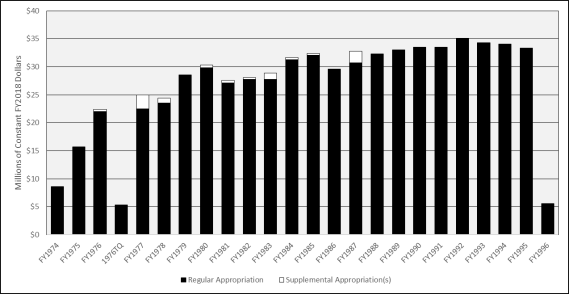

Congress appropriated funds for OTA from FY1974 to FY1996 in annual legislative branch appropriations acts. Funding was provided mainly through regular appropriations acts, but additional funding was provided in some years through supplemental appropriations acts. In some fiscal years, Congress reappropriated unused OTA funds from earlier appropriations, essentially carrying the funds over to the next year. In some years, appropriations were reduced through sequestration or rescission.48

OTA's funding grew steadily throughout its existence, from an initial appropriation of $2 million in FY1974 ($8.6 million in constant FY2019 dollars) to a current dollar peak of $21.3 million in FY1995 ($33.4 million in constant FY2019 dollars).49 See Figure 1 (current dollars) and Figure 2 (constant FY2019 dollars).

OTA's budget peaked in constant dollars in FY1992 at $35.1 million in constant FY2019 dollars.50 OTA received $3.6 million ($5.6 million in constant FY2019 dollars) in FY1996 to close out its operations. According to the Office of Management and Budget, OTA was not funded beyond February 1996.51

Staffing

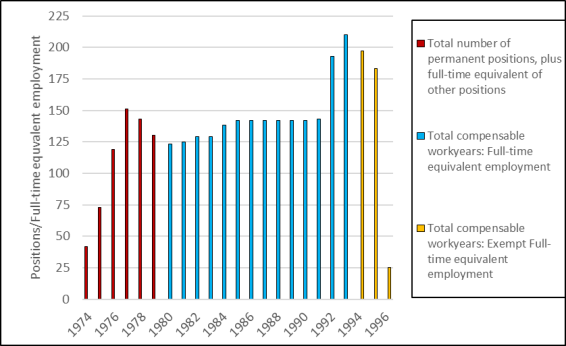

CRS was unable to identify a consistent measurement of OTA staffing that spans the period during which Congress appropriated funds for the agency. Figure 3 includes OTA staffing levels using three different characterizations that were consistent during parts of this time period. The data are from the Budget of the United States Government for fiscal years 1976-1998.52 Using these measures, staffing was first reported for FY1974 at 42, and rose to 151 in FY1977. Staffing then fell through 1980 before rising again, but remained between 123 and 143 from FY1978 to FY1991. In FY1992, reported staffing jumped to 193, and rose to a reported 210 in FY1993. In FY1994, staffing fell to a reported 197 and continued to drop through the end of the agency's funding in FY1996.

During most years of OTA's operations, Congress included an annual cap on the agency's total number of "staff employees" in annual appropriations laws, beginning with a cap of 130 in the FY1978 Legislative Branch Appropriations Act (P.L. 95-94). This cap was included in subsequent appropriations bills through FY1983.53 Congress increased the cap to 139 staff employees for FY1984,54 then increased it again to 143 for FY198555 and maintained this level through FY1995. The cap established a maximum limit on the number of OTA staff employees.

In addition to full-time and temporary staff employees, OTA made extensive use of contractors. As shown in Figure 3, OTA reported the statutory maximum of 143 employees from FY1985 to FY1991. In FY1992, a change in practice may have led to the reporting of contractors in its staffing level, resulting in the reported number of total compensable workyears exceeding total authorized (143) positions. Contractors supplemented the knowledge base of staff employees and were seen by OTA management as critical to the agency's ability to deliver authoritative products on emerging scientific and technological fields, especially with respect to OTA's technology scanning products that sought to characterize possible future science and technology paths and their potential implications.

Observations on OTA's Design and Operations

Peter Blair, in Congress's Own Think Tank, noted that OTA was designed with the intention of serving the unique needs of Congress:

The agency's architects intended the reports and associated information OTA produced to be tuned carefully to the language and context of Congress. OTA's principal products—technology assessments—were designed to inform congressional deliberations and debate about issues that involved science and technology dimensions but without recommending specific policy actions.56

Supporters, critics, and analysts have offered a variety of views on the strengths and weaknesses of OTA. Some have found OTA's work to be professional, authoritative, and helpful to Congress. For example, in a 1979 hearing of the Senate Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Legislative Branch Appropriations, Representative Morris Udall, serving as chairman of the OTA Technology Assessment Board, testified that

The usefulness of the OTA is clear. The office has a place in the legislative process…. During my tenure on the Board, I have enjoyed watching OTA develop and building this record to the point where it is now on a decisive and effective course.57

Others offered a variety of criticisms, including issues related to uniqueness/duplication, timeliness, objectivity, and other factors, which likely helped to lay a foundation for its defunding. These are discussed below.

Uniqueness and Duplication

Some supporters of OTA asserted that the agency served a unique mission, complementary to those of its sister congressional agencies. A 1978 report of the House Committee on Science and Technology Subcommittee on Science, Research, and Technology reporting on its 1977-1978 oversight hearings on OTA stated

OTA has been set up to do a job for the Congress which is: (a) essential, (b) not capable of being duplicated by other legislative entities, and (c) proving useful and relied upon. OTA should retain its basic operating method of depending to a large extent on out-of-house professional assistance in performing its assessments. Continued congressional support for OTA is warranted.58

Subcommittee chairman Representative Ray Thornton subsequently stated that this report "doesn't leave much doubt that the office is a valuable asset to the Congress."59

However, some critics asserted that the OTA mission and the work it did were already performed, or could be performed, by other organizations—such as GAO (then the General Accounting Office),60 CRS, or the National Academies.

This perspective was expressed by Senator Jim Sasser, chairman of the Senate Committee on Appropriations Subcommittee on the Legislative Branch, in a 1979 hearing:

I am, frankly, troubled by the Office of Technology Assessment. This letter from Chairman Magnuson is just one more example of the type and tenor of questioning I receive from my colleagues and others about the Office of Technology Assessment. Frankly…this recurring questioning raises doubts in my mind about the need for the Office of Technology Assessment. From time to time I hear that OTA very often duplicates studies conducted by the three other congressional analytical agencies, that is, the General Accounting Office, the Congressional Research Service and the Congressional Budget Office, or [by] executive branch agencies, such as the National Science Foundation.61

Concerns about duplication continued. During House floor debate on the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 1995, that eliminated funding for OTA, Representative Ron Packard, chairman of the Legislative Branch Subcommittee, stated

In our efforts in this bill we have genuinely tried to find where there is duplication in the legislative branch of Government. This is one area where we found duplication, serious duplication. We have several agencies that are doing very much the same thing in terms of studies and reports.

I am aware of the invaluable service of OTA, but there are other agencies that do the same thing. The CRS has a science division of their agency. GAO has a science capability in their agency. They can do the same thing as OTA….

We ought to eliminate those agencies where duplication exists. This is one of those areas.62

In 2006, Carnegie Mellon University professor Jon M. Peha asserted that, while nonfederal organizations produce high-quality work similar to that performed by OTA, their work is not necessarily duplicative of the type of work OTA was established to perform as the characteristics of their analyses (e.g., directive recommendations, timeliness, format) are qualitatively different and their motivations may be subject to question:

There still are more sources of information outside of government. These tend to be inappropriate for different reasons. The National Academies sometimes are an excellent resource for Congress, but for a different purpose. The National Academies generally attempt to bring diverse experts together to produce a consensus recommendation about what Congress should do. In many cases, Members of Congress do not want to be told what to do. Instead, they want a trustworthy assessment of their options, with the pros and cons of each, so they can make up their own minds. Universities and research institutes also produce valuable work on some important issues, but it rarely is generated at a time when Congress most needs it, or in a format that the overworked generalists of Congress can readily understand and apply. Moreover, Members of Congress must be suspicious that the authors of any externally produced report have an undisclosed agenda.63

Timeliness

Congress established OTA to help it anticipate, understand, and consider "to the fullest extent possible, the consequences of technological applications … in determination of public policy on existing and emerging national problems."64 To do this effectively, Congress needs information, analysis, and options on a timetable with the development and consideration of legislation.

OTA supporters have noted that in recognizing the need for timeliness, the agency sought to inform congressional decisionmaking through a number of other mechanisms beyond its formal assessments. In addition to its formal assessments and summaries, OTA used the following additional mechanisms to inform Congress: technical and other memoranda, testimony, briefings, presentations, workshops, background papers, working papers, and informal discussions.65

Representative Rush Holt commented in 2006 that OTA's reports "were so timely and relevant that many are still useful today."66

While OTA reports were often lauded for being authoritative and comprehensive, some critics asserted that the time it took for OTA to define a report, collect information, gather expert opinions, analyze the topic, and issue a report67 was not consistent with the faster pace of legislative decisionmaking:

Probably the most frequent criticism of OTA from supporters and detractors alike is that it was too slow; some studies took so long that important decisions already were made when the relevant reports were released.68

In its early years, some criticized OTA for producing too many short analyses; later others criticized the agency for concentrating on long-range studies and neglecting committee needs.69

In 2001, the former chairman of the House Committee on Science Robert Walker noted

Too often the OTA process resulted in reports that came well after the decisions had been made. Although it can be argued that even late reports had some intellectual value, they did not help Congress, which funded the agency, do its job.70

Georgetown Law's Institute for Technology Law and Policy published a report on a June 2018 workshop on strategies for improving science and technology policy resources for Congress. Several participants asserted that "OTA's model often failed to deliver timely information to Congress, as the comprehensiveness of the studies and the rigor of the peer review process meant that reports could take 18 months or more to publish."71

Quality and Utility

Some criticisms related to the quality and utility of OTA reports to the legislative process. This concern, and others, were reflected in a 1979 statement by Senator Jim Sasser, chairman of the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on the Legislative Branch:

The accusations are leveled that OTA studies are mediocre, and they are not used in the legislative process, but rather, most of them end up in the warehouse gathering dust, as so many government studies do…. I am not being personally critical of you at all, but it falls to me to respond to these criticisms which I hear from my colleagues and others.72

In 1984 the Heritage Foundation, a think tank, published a paper, Reassessing the Office of Technology Assessment, lauding the agency's independence and quality:

OTA performs an important function for Congress. In an increasingly complex age, Congress needs the means to conduct analyses independent of those produced by industry, lobbies, and the executive branch. The quality control procedures of OTA, as a whole, seem as careful and complete as those of its sister agencies, the General Accounting Office and the Congressional Budget Office.73

Objectivity

There was and is a consensus that objectivity is essential to technology assessment if it is to serve as a foundation (among others) for congressional decision making. However, not all agree that objectivity is necessary to technology assessment, or even possible.

Some assert OTA's work to have been objective. This perspective is reflected in comments by Representative Mark Takano who has stated, "The foundation for good policy is accurate and objective analysis, and for more than two decades the OTA set that foundation by providing relevant, unbiased technical and scientific assessments for Members of Congress and staff."74 Similarly, Representative Sean Casten has stated, "OTA gave us an objective set of truths. We may have creative ideas about how to deal with that truth, but let's not start by arguing about the laws of thermodynamics."75

A report for the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars by Richard Sclove asserted that OTA's work implied a misleading presentation of objectivity:

The OTA sometimes contributed to the misleading impression that public policy analysis can be objective, obscuring the value judgments that go into framing and conducting any [technology assessment] study…. In this regard an authoritative European review of [technology assessment] methods published in 2004 observes that [OTA] … represents the 'classical' [technology assessment] approach.... The shortcomings of the classical approach can be summarized in the fact that the whole [technology assessment] process … needs relevance decisions, evaluations, and the development of criteria, which is at least partially normative and value loaded.76

Another scholar framed concerns about objectivity as a structural issue arising, in part, from single-party control of Congress during OTA's existence. The author noted the need for careful bipartisan and bicameral oversight to overcome perceptions and accusations of bias:

Some Members of Congress raised noteworthy concerns. The most serious allegation was bias. It is not surprising that the party in the minority (before 1995) would raise concerns about bias, given that the other party had dominated Congress throughout OTA's existence…. Bias or the appearance of bias can be devastating. An organization designed to serve Congress must be both responsive and useful to the minority, as well as the majority. Representatives of both parties and both houses must provide careful oversight, so that credit or blame for the organization's professionalism is shared by all.77

Some critics have asserted that OTA was responsive principally to the TAB, "limiting its impact to a very narrow constituency." While the TAB membership was bipartisan and bicameral, this criticism implied that OTA's objectivity was affected to some degree by the perspectives of those serving on the TAB, adding to the notion of structural challenges faced by OTA in achieving objectivity or the appearance of objectivity.78

In the 1980 book, Fat City: How Washington Wastes Your Taxes, author Donald Lambro, a Washington Times reporter, criticized OTA's work as partisan:

Many of OTA's studies and reports … concentrated on issues that were of special concern to [Senator Ted Kennedy]. The views expressed in them were always, of course, right in line with Kennedy's views (or any liberal's, for that matter)…. The agency's studies have proven to be duplicative, frequently shoddy, not altogether objective, and often ignored.79

The 1984 Heritage Foundation paper Reassessing the Office of Technology Assessment asserted that despite OTA's quality control procedures, balance and objectivity concerns remained:

Enough questions have been raised about OTA's procedures and possible biases, therefore, to warrant a thorough congressional review of OTA.80

This was particularly the case, according to the Heritage paper, for products not requested or reviewed by OTA's congressional oversight board, the TAB. The paper singled out for criticism OTA's assessment of the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), President Reagan's plan for a weapon system that would serve as a shield from ballistic missiles. The Heritage Foundation paper asserted that the OTA report on SDI was marred by intentional political bias:

In the [SDI] study, for example, at least one OTA program division placed the political goal of discrediting SDI ahead of balanced and objective analysis.81

Further, the Heritage paper asserted

It is also difficult to believe that the flaws in Carter's study and its disclosure of highly sensitive information are the result of naivete and misunderstanding on the part of the OTA. The evidence that some OTA staffers oppose the Administration's Strategic Defense Initiative seems clear and compelling."82

The Heritage report notes that experts from the SDI office and from Los Alamos National Laboratory questioned the technical accuracy of the report. The report then notes that three analysts selected by OTA Director Jack Gibbons to review the report (described in the report as having been "unsympathetic to strategic defense") commended Carter's study and told Gibbons that he should not withdraw the report.83

In 1988, citing the controversy over the OTA SDI report, Senator Jesse Helms asserted that OTA's work was not objective:

OTA has been obsessed with proving that President Reagan's strategic defense initiative is both wrongheaded and dangerous almost since the very moment Mr. Reagan announced it in 1983. OTA has long ago lost its pretense that it is an objective scientific analysis group. By and large its reports are useless or irrelevant, but it has demonstrated over and over again that its work on SDI is both pernicious and distorted.84

In 2016, Representative Rush Holt disagreed with the assertion of bias in OTA's SDI report asserting, "When it came to missile defense, it was pretty clear to [OTA] that [the technology] wouldn't work as claimed, so they said so."85

A 2004 article in the journal The New Atlantis, "Science and Congress," stated that "the most significant reason for Republican opposition [to reestablishing OTA] is the belief that OTA was a biased organization, and that its whole approach was misguided: a way of giving a supposedly scientific rationale for liberal policy ideas and prejudices." The author offered several examples which, if viewed "through Republican eyes" support this belief.86

According to a report published by Georgetown Law's Institute for Technology Law and Policy, participants in a June 2018 workshop identified "the perception of partisanship" as one of two OTA weaknesses.87

Costs

The issue of the costs of OTA studies was a factor in early oversight of OTA by Congress. On behalf of the chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, the chairman of the Legislative Branch subcommittee raised concerns about "allegations that OTA had either cost or time overruns on a large number of their contracts" in a 1979 appropriations hearing.88 OTA responded that contract overruns had stemmed primarily from modification of the scope of contracts. The agency asserted that its operation was based on the extensive use of outside talent, and that contractors were engaged early in an assessment to help OTA staff and supporting panels to define in more detail the nature of the assessment. This could lead to additional contractor work assignments, requiring modifications to contracts or additional contracts to enable completion of assessments.89

Public Input

When OTA was established, analysts argued that public input into the technology assessment process was important. The efficacy of the OTA process for gaining such input has been a topic of debate. Some have asserted in retrospect that OTA did not have an effective mechanism for taking in public comments.90 Some former OTA staff have disputed this perception. One characterized the charge that OTA lacked citizen participation as "outrageous…. The OTA process was nothing if not participatory."91 Another former OTA staffer, Fred Wood, recognized OTA's efforts in seeking public participation, but lamented that these efforts fell short at times:

Public participation [by representatives of organized stakeholder groups] was one of the bedrock principles of the OTA assessment process.... Yet this aspect of OTA's methodology could be time consuming and still fall short of attaining fully balanced participation, while leaving some interested persons or organizations unsatisfied.92

The TAAC served as one vehicle for nongovernmental input into OTA's work. However, in a 1977 hearing, former Representative Emilio Daddario, who introduced the legislation93 first proposing the creation of an Office of Technology Assessment, testified that the TAAC had been invented in "a hurried effort to provide for some new method of public input into OTA activities, even though unfortunately its role was ill-defined."94

Other Criticisms

Some have offered other criticisms of OTA. For example, a Wilson Center report identified the following additional criticisms of OTA:

- inconsistency in fully identifying and articulating technologies' ethical and social implications;

- failure to identify social repercussions that could arise from interactions among complexities of seemingly unrelated technologies;

- a lack of elucidation of circumstances in which a technology can induce a cascade of follow-on socio-technological developments; and

- failure to develop a "capacity to cultivate, integrate or communicate the informed views of laypeople." 95

Congressional Perspectives on Technology Assessment Expressed During OTA Defunding Debate

At the time of OTA's defunding, some Members of Congress expressed views on which other agencies and organizations might serve the functions performed by OTA—or however much of those functions was still deemed necessary.

The following excerpts from the House and Senate reports accompanying the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 1996 (H.R. 1854, 104th Congress) and from floor debate on the bill provide insight into these post-OTA perspectives:96

The report of the House Committee on Appropriations on H.R. 1854 directed that following the defunding of OTA, any of its necessary functions would be performed by other agencies, such as CRS and GAO, and that supplemental information would be provided by nongovernment organizations:

If any functions of OTA must be retained, they shall be assumed by other agencies such as Congressional Research Service or the General Accounting Office. Alternatively, the National Academy of Sciences, university research programs, and a variety of private sector institutions will be available to supplement the needs of Congress for objective, unbiased technology assessments.97

In its report on the bill, the Senate Committee on Appropriations report stated its disagreement with the House's intent to transfer OTA functions to CRS. The report asserted a variety of differences between OTA and CRS and stated that assigning OTA functions to CRS would harm CRS:

During consideration of the bill by the House of Representatives, an amendment was adopted transferring the functions of the Office of Technology Assessment to the Congressional Research Service. The Committee disagrees with this proposal. The purposes, procedures, methodologies, management, and governance of the CRS and the OTA are quite different, and the Committee believes the merger of the two would substantially harm the Congressional Research Service.98

In debate on the Senate version of the bill, Senator Daniel Inouye asserted that OTA filled a unique and important role for which other legislative branch agencies were not suited:

Some of my colleagues have suggested that we don't need an OTA.... How many of us are able to fully grasp and synthesize highly scientific information and identify the relevant questions that need to be addressed? The OTA was created to provide the Congress with its own source of information on highly technical matters. Who else but a scientifically oriented agency, composed of technical experts, governed by a bipartisan board of congressional overseers, and seeking information directly under congressional auspices, [can give] the Congress and the country accurate and essential information on new technologies?

Can other congressional support agencies and staff provide the information we need? I am second to none in my high regard for these agencies, but each has its own distinct role. The U.S. General Accounting Office is an effective organization of auditors and accountants, not scientists. The Congressional Research Service is busy responding to the requests of members for information and research. The Congressional Budget Office provides the Congress with budget data and with analyses of alternative fiscal and budgetary impacts of legislation. Furthermore, each of these agencies is likely to have its budget reduced, or to be asked to take on more responsibilities, or both, and would find it extremely difficult to take on the kinds of specialized work that OTA has contributed.99

Representative Ron Packard, chair of the House Appropriations Committee's Legislative Branch subcommittee, described the elimination of OTA as "legislative rightsizing" and asserted the availability of other congressional agencies to fill OTA's role:

In our efforts in this bill we have genuinely tried to find where there is duplication in the legislative branch of Government. This is one area where we found duplication, serious duplication. We have several agencies that are doing very much the same thing in terms of studies and reports…. I am aware of the invaluable service of OTA, but there are other agencies that do the same thing. The CRS has a science division of their agency. GAO has a science capability in their agency. They can do the same thing as OTA.

We evaluated how to best consolidate, and it was our conclusion as a committee that to eliminate OTA and absorb the essential functions into some of these other agencies that are going to continue was the best way to go….

I admit OTA has done a good job. They have good, solid professionals, but those professionals can work with other agencies that will do those same functions, if they are essential. We also have the CRS, GAO, and other agencies, such as the National Academy of Sciences. There are many alternatives, or this work can even be privatized and contracted out for the services. But we do not need this agency that has now outgrown its usefulness … has now increased its mission to other areas beyond science.100

In the House, Representative Henry Hyde stated his support for an amendment submitted by Representative Amo Houghton that would have transferred most of the funds and analysts to CRS:

[The amendment] cuts 50 of 190 jobs. It cuts the budget by 32 percent, from $22 million down to $15 million. And it folds its functions into the Congressional Research Service. So we cut down on the money, we cut down on the personnel, we downsize to the bone, but we do not lose the function. It just seems to me in this era of fiber optics and lasers and space stations, we need access to an objective, scholarly source of information that can save us millions and billions.101

The amendment to transfer funds and personnel to CRS was not passed.

Congress, GAO, and Technology Assessment

Following the defunding of OTA, Congress sought help from other organizations to fill a gap for scientific and technical information that previously would have been performed by OTA. According to one analysis, Congress initially increased its use of the National Academies for obtaining such information, though shortly thereafter its usage of the National Academies returned to pre-OTA defunding levels.102

Another option employed by Congress for technology assessment capabilities has been reliance on the GAO. Beginning in the early 2000s, GAO undertook efforts to develop and improve its technology assessment capabilities. Some of these efforts were initiated by GAO itself, other efforts were initiated at Congress's direction.

Congress has not given GAO statutory authority to conduct technology assessments. Rather, Congress provided GAO guidance with respect to its technology assessments and related activities in the form of reports accompanying annual Legislative Branch Appropriations bills since at least 2001.

In 2000, five years after Congress defunded OTA, GAO established the Center for Technology and Engineering in its Applied Research and Methods team. This center, led by GAO's Chief Technologist, later became GAO's Center for Science, Technology, and Engineering.

Shortly thereafter, Congress began to task GAO with technology assessment activities. In 2001, conferees on the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 2002 directed in report language that up to $500,000 of GAO's appropriation be obligated to conduct a technology assessment pilot project and that the results be reported to the Senate by June 15, 2002.103

The conference report did not authorize an assessment topic, but three Senators requested GAO to assess technologies for U.S. border control together with a review of the technology assessment process. At the same time, six House Members wrote to GAO supporting the pilot technology assessment project. After consulting congressional staff, GAO agreed to assess biometric technologies. It used its regular audit processes and also its standing contract with The National Academies to convene two meetings that resulted in advice from 35 external experts on the use of biometric technologies and their implications on privacy and civil liberties. The resulting report was issued in November 2002 as Technology Assessment: Using Biometrics for Border Security (GAO-03-174).104

The FY2003 Senate legislative branch appropriations report noted the utility of GAO's work and said that it was providing $1 million for three GAO studies in order to maintain an assessment capability in the legislative branch and to evaluate the GAO pilot process. However, this language was not included in the Senate bill (S. 2720, 107th Congress); the House bill (H.R. 5121, 107th Congress) or the accompanying report; or in P.L. 108-7, which included as Title H, the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 2003. Although funds were not provided for a study, GAO conducted a technology assessment that was published in May 2004 as Cybersecurity for Critical Infrastructure Protection.105

For FY2004, the Senate Committee on Appropriations recommended $1 million for two or three technology assessments by GAO, but directed the agency only to conduct this technology assessment work if it was consistent with GAO's mission.106 The conference report for the Legislative Appropriations Branch, 2004 (P.L. 108-83) noted that

For the past two years the General Accounting Office (GAO) has been conducting an evaluation of the need for a technology assessment capability in the Legislative Branch. The results of that evaluation have generally concluded that such a capability would enhance the ability of key congressional committees to address complex technical issues in a more timely and effective manner.107

Further, the conferees directed GAO to report by December 15, 2003, to the House and Senate Committees on Appropriations "the impact that assuming a technology assessment role would have on [GAO's] current mission and resources."108

In 2004, a bill was introduced in the Senate (S. 2556, 108th Congress) to establish a technology assessment capability within GAO. The bill would have authorized the Comptroller General to initiate technology assessment studies or to do so at the request of the House, Senate, or any committee; to establish procedures to govern the conduct of assessments; to have studies peer reviewed; to avoid duplication of effort with other entities; to establish a five-member technology assessment advisory panel; and to have contracting authority to conduct assessments. In addition, the bill would have authorized $2 million annually to GAO to conduct assessments. The bill was referred to the Committee on Governmental Affairs and no further action was taken. A similar bill was introduced in the House (H.R. 4670, 108th Congress) and referred to the House Committee on Science; no further action was taken.

For FY2005, GAO requested $545,000 in appropriations for four new full-time equivalent (FTE) positions and contract support to establish a baseline technology assessment capability that would allow the agency to conduct one assessment per year. In its report, the House Appropriations Committee did not address funding for GAO for technology assessment, but encouraged GAO to "... retain its core competency to undertake additional technology assessment studies as might be directed by Congress."109 An amendment to add $30 million to GAO's FY2005 appropriations for the purpose of establishing a Center for Science and Technology Assessment was rejected by the House.

The Senate Committee on Appropriations report on the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 2005 (S. 2666, 108th Congress) provided additional guidance to GAO with respect to its technology assessment activities, limiting future technology assessments to those having the support of leadership of both houses of Congress and to technology assessments that "are intended to address significant issues of national scope and concern." In addition, the report directed the GAO Comptroller General to consult with the committee "concerning the development of definitions and procedures to be used for technology assessments by GAO." 110

In 2007, the House Committee on Appropriations recommended $2.5 million for GAO for technology assessments in FY2008, stating that

as technology continues to change and expand rapidly it is essential that the consequences of technological applications be anticipated, understood, and considered in determination of public policy on existing and emerging national problems. The Committee believes it is necessary for the Congress to equip itself with effective means for securing competent, timely and unbiased information concerning the effects of scientific and technical developments and use the information in the legislative assessment of matters pending before the Congress.111

That same year, the Senate committee report on the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 2008 (S. 1686, 110th Congress) recommended $750,000 and four FTE employees to establish a permanent technology assessment function in the GAO. The report also stated that the committee had "decided not to establish a separate entity to provide independent technology assessment for the legislative branch owing to budget constraints." Further, it asserted that GAO's focus on "producing quality reports that are professional, objective, fact-based, fair, balanced, and nonpartisan is consistent with the needs of an independent legislative branch technology assessment function." In addition, the committee directed GAO "to define an operational concept for this line of work, adapted from current tested processes and protocols," and to report to Congress on the concept.112

Conferees on the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008 (H.R. 2764, 110th Congress; P.L. 110-161) agreed to provide $2.5 million for GAO for technology assessments in FY2008, asserted the importance of technology assessment to Congress's public policy deliberations, and directed the Comptroller General to ensure that "GAO is able to provide effective means for securing competent, timely and unbiased information to Congress regarding the effects of scientific and technical developments."113

For FY2009, conferees continued funding for GAO's technology assessment and reminded the agency that "for the assessments to be of benefit to the Congress, GAO must reach out and work with both bodies of Congress regarding these studies."114

For FY2010, the House Committee on Appropriations recommended continuing GAO technology assessment funding at the FY2009 level.115 The conference report on Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 2010, endorsed the chamber reports.

No direction was given by Congress to GAO in House, Senate, or conference appropriations reports regarding technology assessment for FY2011, FY2012, FY2013, or FY2014.