DHS Budget Request Analysis: FY2021

On February 10, 2020, the Donald J. Trump Administration released their budget request for FY2021, including a $75.84 billion budget request for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

DHS is the third largest agency in the federal government in terms of personnel. The appropriations bill that funds it—providing $70 billion in FY2020—is the seventh largest of the twelve annual funding measures developed by the appropriations committees, and is the only appropriations bill that funds a single agency in its entirety and nothing else.

This report provides an overview of the FY2021 budget request for the Department of Homeland Security. It provides a component-level overview of the appropriations sought in the FY2021 budget request, putting the requested appropriations in the context of the FY2020 requested and enacted level of appropriations, and noting the primary drivers of changes from the FY2020 enacted level.

The FY2021 budget request represents the fourth detailed budget proposed by the Trump Administration. It is the earliest release of a budget request by the Trump Administration, and comes 52 days after the enactment of the FY2020 consolidated appropriations measures—the longest such gap since the release of the FY2017 request (53 days), and the first since then to include prior-year enacted funding levels as a comparative baseline.

Some of the major drivers of change in the FY2021 request include

A $3 billion reduction in border barrier funding through U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) compared to the FY2020 request;

A $2.4 billion reduction from the enacted level of funding due to the proposed move of the U.S. Secret Service to the Department of the Treasury;

A $709 million increase in requested Transportation Security Administration (TSA) fee revenues;

A $9 billion reduction in disaster relief funding through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) compared to the FY2020 request;

A $986 million increase from the FY2020 requested level for the U.S. Coast Guard—proposing funding $129 million above the enacted level;

A $1.1 billion increase from the FY2020 requested level for Immigration and Customs Enforcement—$2 billion (24%) more than enacted in FY2020; and

A $456 million increase for the Transportation Security Administration’s budget from the FY2020 requested level—proposing funding $59 million below the enacted level.

Six of the seven smallest components by gross budget authority saw their budget requests reduced by at least 5% from the enacted level, and four of those components saw reductions of more than 10%.

This report will not be updated.

DHS Budget Request Analysis: FY2021

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Data Sources and Caveats

- Structure of the DHS Budget

- FY2021 Context

- Appropriations Analysis

- Comparing the FY2021 Request to Prior-Year Levels

- Common DHS Appropriation Types

- Staffing

- Overview of Component-Level Changes

- Law Enforcement Operational Components (Title II)

- Customs and Border Protection (CBP)

- Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)

- Transportation Security Administration (TSA)

- U.S. Coast Guard (USCG)

- U.S. Secret Service (USSS)

- Incident Response and Recovery Operational Components (Title III)

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

- Support Components (Title IV)

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)

- Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers (FLETC)

- Science and Technology Directorate (S&T)

- Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office (CWMD)

- Headquarters Components (Title I)

- Office of the Secretary and Executive Management (OSEM)

- Departmental Management Directorate (MD)

- Analysis and Operations (A&O)

- Office of Inspector General (OIG)

- Administrative and General Provisions

- Administrative Provisions

- General Provisions

Figures

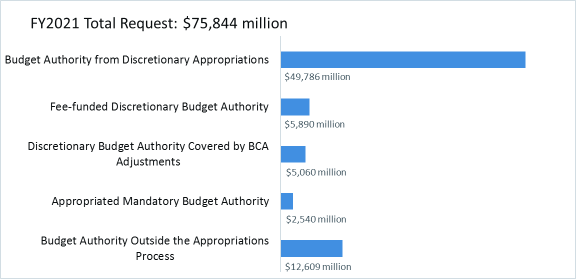

- Figure 1. FY2021 Budget Request Structure

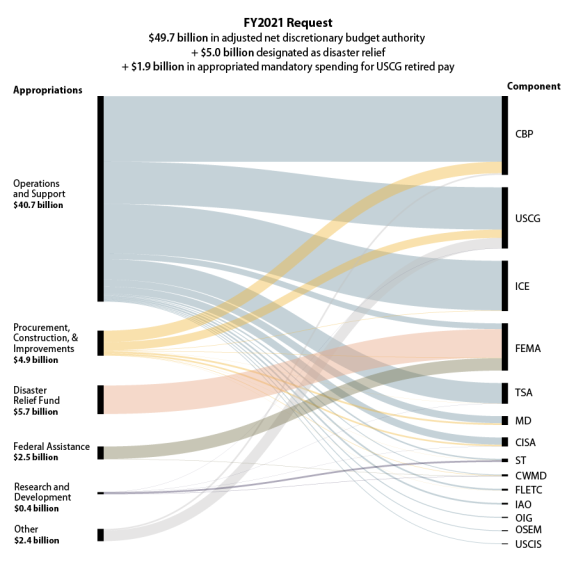

- Figure 2. Comparing Budget Structure: FY2021 Request, FY2020 Enacted, and FY2020 Request

- Figure 3. DHS FY2021 Appropriations Request, Showing Appropriation Categories by Component

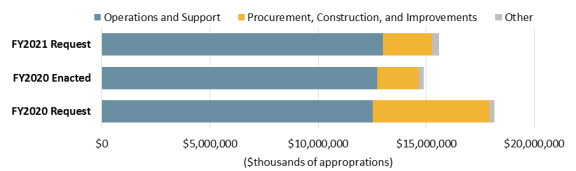

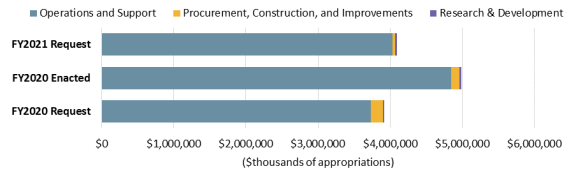

- Figure 4. CBP Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

- Figure 5. ICE Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

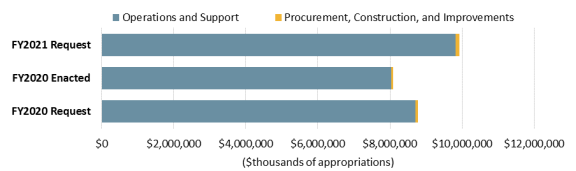

- Figure 6. TSA Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

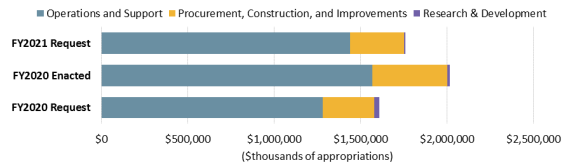

- Figure 7. USCG Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

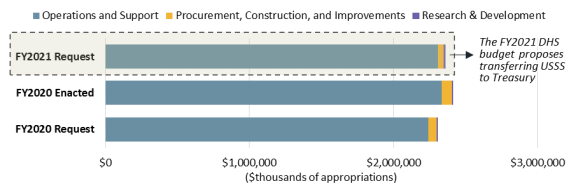

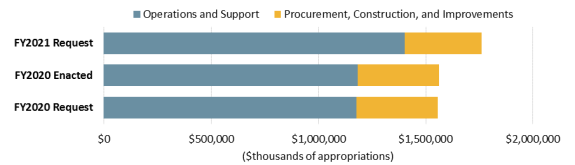

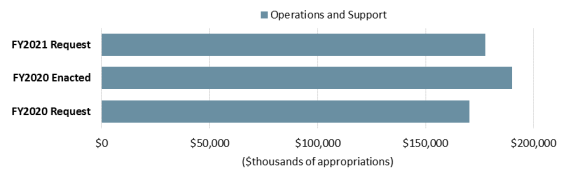

- Figure 8. USSS Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

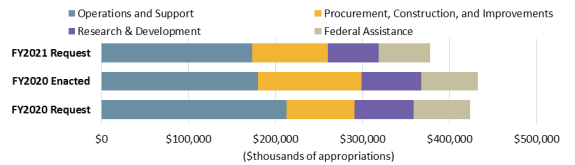

- Figure 9. CISA Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

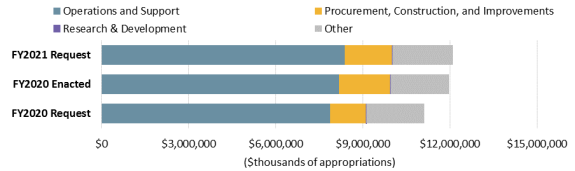

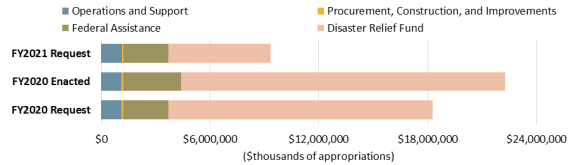

- Figure 10. FEMA Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

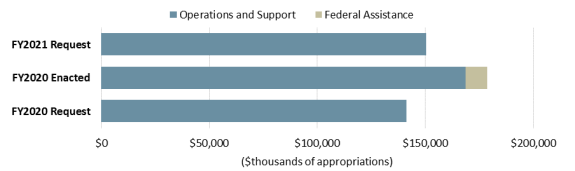

- Figure 11. USCIS Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

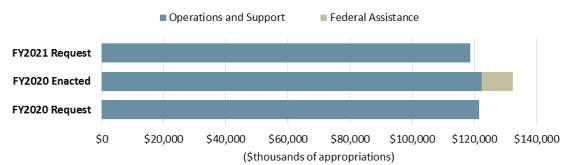

- Figure 12. FLETC Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

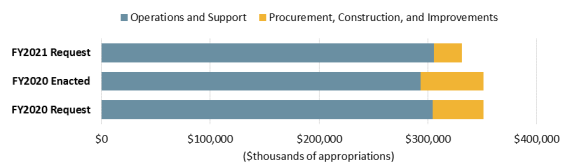

- Figure 13. S&T Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

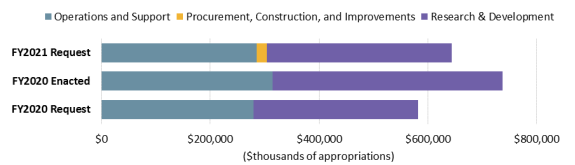

- Figure 14. CWMD Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

- Figure 15. OSEM Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

- Figure 16. MD Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

- Figure 17. A&O Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

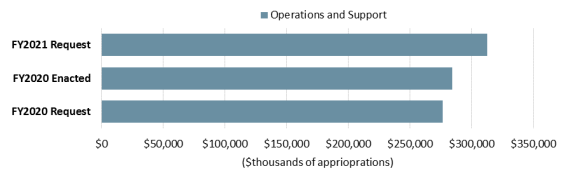

- Figure 18. OIG Requested and Enacted Appropriations by Type, FY2020-FY2021

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

On February 10, 2020, the Donald J. Trump Administration released their budget request for FY2021, including a $75.84 billion budget request for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

DHS is the third largest agency in the federal government in terms of personnel. The appropriations bill that funds it—providing $70 billion in FY2020—is the seventh largest of the twelve annual funding measures developed by the appropriations committees, and is the only appropriations bill that funds a single agency in its entirety and nothing else.

This report provides an overview of the FY2021 budget request for the Department of Homeland Security. It provides a component-level overview of the appropriations sought in the FY2021 budget request, putting the requested appropriations in the context of the FY2020 requested and enacted level of appropriations, and noting the primary drivers of changes from the FY2020 enacted level.

The FY2021 budget request represents the fourth detailed budget proposed by the Trump Administration. It is the earliest release of a budget request by the Trump Administration, and comes 52 days after the enactment of the FY2020 consolidated appropriations measures—the longest such gap since the release of the FY2017 request (53 days), and the first since then to include prior-year enacted funding levels as a comparative baseline.

Some of the major drivers of change in the FY2021 request include

- A $3 billion reduction in border barrier funding through U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) compared to the FY2020 request;

- A $2.4 billion reduction from the enacted level of funding due to the proposed move of the U.S. Secret Service to the Department of the Treasury;

- A $709 million increase in requested Transportation Security Administration (TSA) fee revenues;

- A $9 billion reduction in disaster relief funding through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) compared to the FY2020 request;

- A $986 million increase from the FY2020 requested level for the U.S. Coast Guard—proposing funding $129 million above the enacted level;

- A $1.1 billion increase from the FY2020 requested level for Immigration and Customs Enforcement—$2 billion (24%) more than enacted in FY2020; and

- A $456 million increase for the Transportation Security Administration's budget from the FY2020 requested level—proposing funding $59 million below the enacted level.

Six of the seven smallest components by gross budget authority saw their budget requests reduced by at least 5% from the enacted level, and four of those components saw reductions of more than 10%.

This report will not be updated.

Introduction

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is the third largest agency in the federal government in terms of personnel. The appropriations bill that funds it—providing $70 billion in FY2020—is the seventh largest of the 12 annual funding measures developed by the appropriations committees, and is the only appropriations bill that funds a single agency in its entirety and nothing else.

This report provides an overview of the FY2021 budget request for the Department of Homeland Security. It provides a component-level overview of the appropriations sought in the FY2021 budget request, putting the requested appropriations in the context of the FY2020 requested and enacted level of appropriations, and noting some of the larger changes in this proposal from those baselines.

Data Sources and Caveats

To ensure consistency of methodology, the analysis in this report is based on Office of Management and Budget (OMB) data as presented in the FY2020 and FY2021 Budget in Brief for DHS, with supporting information from the DHS congressional budget justifications for FY2021, except where noted.1 Most other CRS reports rely on Congressional Budget Office (CBO) data, which was not available at the time of publication at a similar level of granularity. Numbers expressed in billions are rounded to the nearest hundredth ($10 million), while numbers expressed in millions are rounded to the nearest million.

None of the FY2020 requested or enacted levels in this bill include supplemental appropriations requested and provided in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as the intent is to analyze the FY2021 annual appropriations request in comparison to the preceding request and ensuing annual appropriation.

Structure of the DHS Budget

FY2021 Context

The FY2021 budget request represents the fourth detailed budget proposed by the administration of President Donald J. Trump. It is the earliest release of a budget request by the Trump Administration, and comes 52 days after the enactment of the FY2020 consolidated appropriations measures—the longest such gap since the release of the FY2017 request (53 days), and the first since then to include prior-year enacted funding levels as a comparative baseline. This allows for easier analysis of the request compared to current funding.

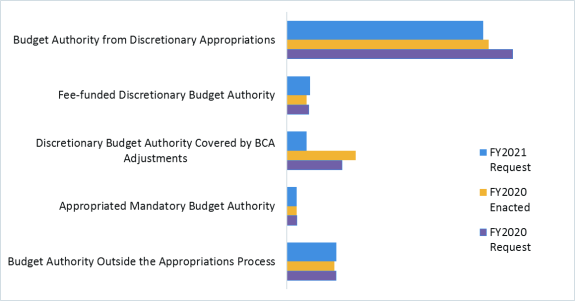

The budget for DHS includes a variety of discretionary and mandatory budget authority. Aside from standard discretionary spending, some of the discretionary spending in the bill is offset by collections of fees, reducing the net effect on the general fund of the Treasury. Some discretionary budget authority is specially designated under the Budget Control Act (BCA),2 adjusting the statutory limits on discretionary spending to accommodate it. DHS also draws resources from fee revenues and other collections included in the mandatory budget, which are not usually referenced in annual appropriations legislation. However, some mandatory spending items still require an appropriation because there is no dedicated source of funding to meet the government's obligations established in law—e.g., U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) retirement accounts.3 Figure 1 shows a breakdown of these different categories from the FY2021 budget request.

Congress and the Administration may differ on how funding for the department is structured; frequently, administrations of both parties have suggested paying for certain activities with fee increases that would require legislative approval. If fees are not increased, additional discretionary appropriations must be provided to fund the planned activities.

Figure 2 compares the structure of the FY2021 budget request to its enacted FY2020 equivalent, as well as the FY2020 request. Significant differences include

- In budget authority from discretionary appropriations,

- a $3 billion reduction in border barrier funding through U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) compared to the FY2020 request; and

- a $2.4 billion reduction from the enacted level of funding due to the proposed move of the U.S. Secret Service to the Department of the Treasury.

- In fee-funded discretionary budget authority, a $709 million increase in requested Transportation Security Administration (TSA) fee revenues; and

- In discretionary budget authority covered by adjustments under the BCA, a $9 billion reduction in disaster relief funding through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) compared to the FY2020 request.

|

Figure 2. Comparing Budget Structure: FY2021 Request, FY2020 Enacted, and FY2020 Request |

|

|

Source: Developed by CRS, based on the resource tables from the DHS Budget in Brief, FY2021 and FY2020. Notes: Figure 2's "Discretionary Budget Authority Covered by BCA Adjustments" reflects a downward revision of the Administration's FY2020 budget request for the costs of major disasters from $19.423 billion to $14.100 billion. Enacted levels do not include supplemental appropriations provided in P.L. 116-136. |

Appropriations Analysis

Comparing the FY2021 Request to Prior-Year Levels

Table 1 presents for comparison the requested gross budget authority controlled in appropriations legislation for FY2021 for each DHS component, as well as the level requested and enacted for FY2020. This is essentially composed of the first four elements in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

- Four analytical columns on the right side of the table provide comparisons of the FY2021 requested funding levels with the FY2020 requested and enacted levels, indicating dollar and percentage change.

- Components are listed in order of their total FY2020 enacted gross budget authority.

- Indented and italicized lines beneath the Coast Guard and Federal Emergency Management Agency entries show the portion of the above amount covered by adjustments for disaster relief and overseas contingency operations, provided for under the BCA.

- The funding levels in Table 1 include the effects of all elements of the budget tracked in the detail tables accompanying annual appropriations for DHS, except rescissions of prior-year appropriations.4

- While this table compares data developed with the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) scoring methodology and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) scoring methodology, most of the data compared is identical.5

- Most of the $40 million in scoring differences identified by OMB is the result of $34 million differences in the treatment of fees, transfers and rounding within the CBP budget, with the remainder being the result of differences in rounding across the DHS funding structure.6

Table 1 illuminates several shifts within the FY2021 DHS budget request that are not apparent in top-line analysis:

- a $986 million increase from the FY2020 requested level for the U.S. Coast Guard;

- a $1.1 billion increase from the FY2020 requested level for Immigration and Customs Enforcement—$2 billion (24%) more than enacted in FY2020;

- a $456 million increase for the Transportation Security Administration's budget from the FY2020 requested level; and

- a proposed transfer of the Federal Protective Service from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency to the Management Directorate during the FY2020 process, shifting almost $1.6 billion between the components.

Table 1 also illuminates budgetary pressure on DHS's smaller headquarters and support components. With one exception—Analysis and Operations—the seven smallest components by gross budget authority saw their budget requests reduced by at least 5% from the enacted level, and four of those components saw reductions of more than 10%.

Table 1. Component-Level Analysis of the DHS Budget Request (FY2020-FY2021)

(thousands of dollars of gross budget authority)

|

Component |

FY2021 Request |

vs. FY2020 Request |

% |

vs. FY2020 Enacted |

% |

|

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) |

18,209,969 |

(2,598,945) |

(12.5%) |

837,671 |

4.8% |

|

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) |

9,561,028a |

(8,652,703) |

(47.5%) |

(12,963,042) |

(57.6%) |

|

Disaster Relief Adjustment |

5,059,949 |

(9,015,051) |

(64.1%) |

(12,292,163) |

(70.8%) |

|

U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) |

12,105,598a |

986,182 |

8.9% |

139,474 |

1.2% |

|

OCO/GWOT Adjustment |

— |

— |

n/a |

(190,000) |

(100.0%) |

|

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) |

10,416,160 |

1,107,565 |

11.9% |

2,016,289 |

24.0% |

|

Transportation Security Administration (TSA) |

8,241,792 |

456,158 |

5.9% |

(58,689) |

(0.7%) |

|

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) |

5,050,549 |

210,139 |

4.3% |

199,330 |

4.1% |

|

Management Directorate (MD) |

3,350,394 |

1,793,106 |

115.1% |

227,024 |

7.3% |

|

U.S. Secret Service (USSS) |

— |

(2,308,977) |

(100.0%) |

(2,415,845) |

(100.0%) |

|

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection Agency (CISA) |

1,757,798 |

(1,418,352) |

(44.7%) |

(257,824) |

(12.8%) |

|

Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) |

643,729 |

61,612 |

10.6% |

(93,546) |

(12.7%) |

|

Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction (CWMD) |

377,160 |

(45,998) |

(10.9%) |

(55,139) |

(12.8%) |

|

Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers (FLETC) |

331,479 |

(19,456) |

(5.5%) |

(19,691) |

(5.6%) |

|

Analysis and Operations (A&O) |

312,638 |

35,997 |

13.0% |

28,497 |

10.0% |

|

Office of the Inspector General (OIG) |

177,779 |

7,593 |

4.5% |

(12,407) |

(6.5%) |

|

Office of the Secretary and Executive Management (OSEM) |

150,359 |

9,049 |

6.4% |

(18,449) |

(10.9%) |

Source: CRS analysis of the detail table from annual FY2020 DHS Appropriations, drawn from Congressional Record, December 17, 2019, pp. H11024-H11060, and the "DHS Resource Table" from the FY2021 DHS Budget In Brief.

Notes: Numbers in parentheses are negative. The FY2021 budget request proposes moving the U.S. Secret Service to the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

a. These totals do not include roughly $5 billion in mandatory budget authority for FEMA through the National Flood Insurance Fund.

b. These totals do not include roughly $225 million in mandatory budget authority for the USCG for Boat Safety, the Maritime Oil Spill Program, and the General Gift Fund.

Common DHS Appropriation Types

Under the Common Appropriations Structure (CAS) first implemented with the FY2017 DHS annual appropriation, most DHS discretionary appropriations were rearranged into four uniform categories:

- Operations and Support—generally personnel and operational costs (all components have this);

- Procurement, Construction, and Improvements—generally acquisition and construction (many components have this);

- Research and Development (TSA, USCG, USSS, CISA, S&T, and CWMD have this in the FY2021 budget request); and

- Federal Assistance (only FEMA and CWMD have this in the FY2021 budget request).

FEMA's Disaster Relief Fund is a unique discretionary appropriation which was preserved separately, in part due to the history of the high level of public and congressional interest in that particular structure.7

The use of the CAS structure allows a quick survey of the level of departmental investment in these broad categories of spending through the appropriations process. A visual representation of this new structure follows in Figure 3. On the left are the five appropriations categories of the CAS with a black bar representing the requested FY2021 funding levels requested for DHS for each. A sixth catch-all category is included for budget authority associated with the legislation that does not fit the CAS categories. Colored lines flow to the DHS components listed on the right, showing the amount of funding provided through each category to each component.

Staffing

The Operations and Support appropriation for each component pays for most DHS staffing.8 Table 2 analyzes changes to DHS staffing, as illuminated by the request's information on positions and full-time equivalents (FTEs)9 for each component. Appropriations legislation does not explicitly set these levels, so the information is drawn from budget request documents alone.

The first data column indicates the number of positions requested for each component in the FY2021 budget request. The next four columns show the difference between the FY2021 request and the Administration's previous request—expressed numerically, then as a percentage—and then shows the same comparison with the FY2020 enacted number of positions as interpreted by the Administration. Another data column shows the number of FTEs, followed by four more analytical columns showing the same comparisons as were run for positions.

|

Component |

FY2021 Request (Positions) |

Change from FY2020 Request (Positions) |

% |

Change from FY2020 Enacted (Positions) |

% |

FY2021 Request (FTE) |

Change from FY2020 Request (FTE) |

% |

Change from FY2020 Enacted (FTE) |

% |

|

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

65,285 |

(1,112) |

(1.7%) |

786 |

1.2% |

62,697 |

1,298 |

2.1% |

1,053 |

1.7% |

|

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

5,398 |

47 |

0.9% |

24 |

0.4% |

12,297 |

945 |

8.3% |

964 |

8.5% |

|

U.S. Coast Guard |

51,170 |

321 |

0.6% |

417 |

0.8% |

49,856 |

640 |

1.3% |

444 |

0.9% |

|

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

25,963 |

(130) |

(0.5%) |

4,636 |

21.7% |

22,176 |

(2,285) |

(9.3%) |

1,264 |

6.0% |

|

Transportation Security Administration |

58,192 |

1,254 |

2.2% |

(1,311) |

(2.2%) |

55,314 |

1,021 |

1.9% |

(1,111) |

(2.0%) |

|

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services |

21,055 |

657 |

3.2% |

657 |

3.2% |

20,003 |

623 |

3.2% |

623 |

3.2% |

|

Management Directorate |

3,962 |

1,634 |

70.2% |

32 |

0.8% |

3,738 |

1,623 |

76.7% |

116 |

3.2% |

|

U.S. Secret Service |

— |

(7,777) |

(100.0%) |

(7,777) |

(100.0%) |

— |

(7,647) |

(100.0%) |

(7,647) |

(100.0%) |

|

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection Agency |

2,698 |

(1,411) |

(34.3%) |

23 |

0.9% |

2,235 |

(1,344) |

(37.6%) |

77 |

3.6% |

|

Science and Technology Directorate |

456 |

19 |

4.3% |

(51) |

(10.1%) |

456 |

19 |

4.3% |

(43) |

(8.6%) |

|

Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction |

286 |

38 |

15.3% |

38 |

15.3% |

266 |

34 |

14.7% |

34 |

14.7% |

|

Federal Law Enforcement Training Center |

1,084 |

(123) |

(10.2%) |

(24) |

(2.2%) |

1,053 |

(127) |

(10.8%) |

(28) |

(2.6%) |

|

Analysis and Operations |

897 |

— |

0.0% |

— |

0.0% |

853 |

1 |

0.1% |

1 |

0.1% |

|

Office of the Inspector General |

725 |

(48) |

(6.2%) |

(48) |

(6.2%) |

747 |

2 |

0.3% |

(9) |

(1.2%) |

|

Office of the Secretary and Executive Management |

693 |

50 |

7.8% |

35 |

5.3% |

635 |

45 |

7.6% |

30 |

5.0% |

Source: CRS analysis of the DHS Resource Table from the FY2020 and FY2021 DHS Budget in Brief.

Notes: Numbers in parentheses are negative. The FY2021 budget request proposes moving the U.S. Secret Service to the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Overview of Component-Level Changes

The following summaries of the budget requests for DHS components are drawn from a survey of the DHS FY2021 Budget in Brief and the budget justifications for each component. Each begins with a graphic outlining the appropriations requested and enacted for the components in FY2020 and FY2021, followed by some observations on the factors that contribute to the illustrated structure. The appropriations request includes all funding provided through the appropriations measure, regardless of how it is scored: it does not include most mandatory spending, such as programs paid for directly by collected fees that have appropriations in permanent law.

Each component has an Operations and Support appropriation, which includes discretionary funding for pay. A 3.1% civilian pay increase was adopted for 2020, and a 1.0% civilian pay increase has been proposed by the Administration for 2021. Descriptions of each Operations and Support appropriation note the impact of these pay increases and associated increases to component retirement contributions to better illuminate the changes in the level of other operational funding.

Law Enforcement Operational Components (Title II)

Customs and Border Protection (CBP)

The Administration's $15.60 billion appropriations request for CBP was $724 million (4.9%) above the FY2020 enacted level, and $2.55 billion (14.1%) below the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The request includes

- $252 million more than enacted for Operations and Support, largely driven by $414 million for pay and retirement cost increases.10

- $161 million was requested for 750 additional border patrol agents and 126 support staff. No additional appropriations were requested for new CBP Officers, who staff ports of entry.

- $21 million was requested for 300 Border Patrol Processing Coordinators, who are intended to take over non-law enforcement duties currently performed by Border Patrol Agents.

- The request for Operations and Support includes a new $7 million item for the Southwest Border Wall System Program, intended to maintain newly constructed barriers.11

- $377 million more than enacted for Procurement, Construction, and Improvements.

- The $2.06 billion request for Border Security Assets and Infrastructure is $552 million more than enacted in annual appropriations for FY2020, and $3.12 billion less than requested in FY2020.12

- The primary driver of this change from the FY2020 request is a reduction of $3.04 billion in construction funding for the border wall system.13

- While the FY2020 Budget-in-Brief cites $182 million for facilities improvements and various investments for technology, aircraft, and vehicles,14 appropriations not for border barriers were reduced from the FY2020 enacted level of $529 million to $281 million in the request.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)

The Administration's $9.93 billion appropriations request for ICE was $1.85 billion (22.9%) above the FY2020 enacted level, and $1.15 billion (13.0%) above the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The request includes

- $1.79 billion more than enacted for Operations and Support, largely driven by a 4,636 position (22%) increase requested in personnel funded through appropriations.

- This increase would include 2,844 law enforcement officers and 1,792 support staff. While all of the primary programs under ICE would receive additional staff, Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) would receive 2,792 positions, a 34% increase above the current enacted level (8,201). Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) would receive 1,053 additional personnel, a 12% increase above the current enacted level (8,784).15

- $220 million (12.3%) of the requested increase in Operations and Support appropriations is for pay and retirement increases.16

- $58 million more than enacted for Procurement, Construction, and Improvements.

- This is $26 million more than the request for FY2020, growth largely driven by a nearly $14 million increase above the FY2020 requested level for Operational Communications and Information Technology.

- Also included in the Administration's request was $112 million in fee funding from the Immigration Examinations Fee Account—similar to a proposal not approved by Congress for FY2020—which would fund 936 current personnel.17

Transportation Security Administration (TSA)

The Administration's $4.09 billion net appropriations request for TSA was $890 million (17.9%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $175 million (4.5%) above the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. With the resources from offsetting fees included, the gross discretionary total is for a request of $7.63 billion, $181 million (2.3%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $334 million (4.6%) above the FY2020 requested level. The request includes

- $820 million (16.9%) less than enacted in FY2020 for Operations and Support appropriations, compensated for in large part by $709 million in proposed increases to offsetting collections.

- Operations and Support cost increases within this amount include $251 million for paying increased pay and retirement costs.18

- $77 million (69.7%) less in discretionary appropriations than enacted in FY2020 for Procurement, Construction, and Improvements; $129 million less in discretionary appropriations than was requested for FY2020. $250 million continues to be provided in mandatory appropriations from the Aviation Security Capital Fund as it has since FY2004.

- $7 million (28.9%) more than enacted in FY2020 for Research and Development appropriations, on the basis of $8 million for two new projects to improve threat detection at TSA checkpoints.19

U.S. Coast Guard (USCG)

The Administration's $12.11 billion appropriations request for USCG was $139 million (1.2%) above the FY2020 enacted level, and $986 million (8.9%) above the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The request included

- $196 million (2.4%) more than enacted in FY2020 for Operations and Support, $164 million of which is for pay and retirement increases, and increases to allowances for military personnel.20

- For the first time in many years, the costs of Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) were proposed for inclusion in the base discretionary appropriation for Operations and Support, without designation to adjust the discretionary budget limits to accommodate it. The OCO proposal was for $215 million in FY2021, up $25 million from the FY2020 enacted level.

- The budget request also included more than $30 million in increases for cyber operations.21

- $135 million (7.6%) less than enacted for Procurement, Construction, and Improvements.

- Reductions of $130 million (80.7%) for the National Security Cutter program and $240 million (92.3%) for the Fast Response Cutter program were offset by increases of $234 million (75%) for the Offshore Patrol Cutter program and $420 million (311%) for the Polar Security Cutter program, as part of a net increase of $286 million (28.8%) for USCG vessels procurement.

- $351 million (69.6%) less than enacted was requested for USCG aircraft procurement.

- $13 million (18.6%) less than enacted was requested for other acquisition programs, and $58 million (28.3%) less than enacted for Shore Facilities and Aids to Navigation.

- Less than $1 million (6.6%) more than enacted was requested for Research and Development.

U.S. Secret Service (USSS)

The Administration's budget request envisions moving the USSS to the Department of the Treasury. However, the budget is still structured as it would be in DHS, and the numbers are provided here for analytical purposes.22

The $2.36 billion appropriations request for USSS was $55 million (2.3%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $52 million (2.2%) above the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The request included

- $26 million (1.1%) less than enacted for Operations and Support, despite $71 million being added for the costs of pay and retirement increases.23

- The primary driver of the decrease was the anticipated reduction of $86 million in costs from the conclusion of the 2020 presidential election cycle.

- $20 million for 119 additional personnel and $20 million in transition costs for the proposed transition of the USSS back to Treasury also are included in the request.24

- $29 million (42.8%) less than enacted in FY2020 for Procurement, Construction, and Improvements, and less than $1 million (4.2%) less than enacted for Research and Development.

Incident Response and Recovery Operational Components (Title III)

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

The Administration's $1.76 billion appropriations request for CISA was $258 million (12.8%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $150 million (9.3%) above the level of net appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The request included

- $128 million (8.2%) less than enacted in FY2020 for Operations and Support, despite $28 million being added for the costs of pay and retirement increases.25

- The reduction is largely driven by the proposal to convert the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism and Safety program to a voluntary initiative, reducing program costs by $68 million, and a $34 million reduction in Threat Analysis and Response.26

- $121 million (27.9%) less than enacted in FY2020 for Procurement, Construction, and Improvements, largely driven by a $114 million reduction in Cybersecurity Assets and Infrastructure, $75 million of which is to the National Cybersecurity Protection System.27

- $8 million (55.4%) less than enacted in FY2020 for Research and Development, due to reductions in funding for the Technology Development and Deployment Program and National Infrastructure Simulation and Analysis Center.28

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

The Administration's $9.36 billion appropriations request for FEMA was $12.92 billion (58.0%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $8.65 billion (48.0%) below the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The primary driver of this change is a $12.29 billion reduction from the enacted level for the costs of major disasters (a large portion of the resources in the Disaster Relief Fund). If this reduction is set aside, the request is a $628 million reduction from the FY2020 enacted level, and a $364 million increase from the FY2020 request. The request includes

- $32 million (2.9%) more than enacted for Operations and Support, $32 million of which is for pay and retirement increases (the combination of other increases and decreases in the account has a net zero effect);29

- $47 million (35.1%) less than enacted for Procurement, Construction, and Improvements, largely due to lower requests for grants management modernization, Mount Weather facilities, and the Center for Domestic Preparedness;30

- $696 million (21.9%) less than enacted for Federal Assistance, largely due to reduction in preparedness grants, the Flood Hazard Mapping and Risk Analysis Program, and elimination of the Emergency Food and Shelter Program;31 and

- $12.21 billion (68.4%) less than enacted for the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF).

- The request for the portion of the DRF that covers major disasters dropped from an enacted level of $17.35 billion to $5.06 billion, a request that is based on the average of the last 10 years obligations for major disasters costing less than $500 million (termed "non-catastrophic disasters"), and spending plans for past disasters costing FEMA more than $500 million (termed "catastrophic disasters").32

- The portion of the DRF that covers emergencies and other activities increased $82 million (16.1%) to $521 million, largely on the basis of an increase in the 10-year average of those costs, and $15 million for real estate needs associated with FEMA's Recovery Service Centers.33

Support Components (Title IV)

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)

The Administration's $119 million appropriations request for USCIS was $14 million (10.4%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $3 million (2.4%) below the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The request includes

- $4 million (3.0%) less for Operations and Support than enacted in FY2020, and $3 million (2.4%) less than requested—$2 million in increased pay raise and retirement costs were offset by reduced costs for rent and efficiencies through modernization efforts.34

- The request does not include an appropriations request for Federal Assistance, which received $10 million in the FY2020 enacted DHS appropriations bill for Citizenship and Integration Grants, which the Administration proposes funding through Immigration Examinations Fee revenues.35

- Less than 3% of the USCIS budget is appropriated. The budget request projects more than $4.9 billion in mandatory spending for USCIS—97% of its total budget—will be supported by fees in FY2021, up $213 million (4.5%) from FY2020 levels. This overall structure is similar to last year's request.

Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers (FLETC)

The Administration's $331 million appropriations request for FLETC was $20 million (5.6%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $19 million (5.5%) below the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. FLETC also anticipates receiving $211 million (up $25 million, or 13.4%) in reimbursements for training and facilities use from those it serves. The request includes

- $12 million (4.3%) more than was enacted in FY2020 for Operations and Support, $7 million of which is for increased pay and retirement costs;36

- $32 million (55.3%) less than was enacted in FY2020 for Procurement, Construction, and Improvements, due to completion of funding for projects in the FY2020 enacted appropriation. The FY2021 budget includes $26 million for the purchase of two dorms it currently leases.37

Science and Technology Directorate (S&T)

The Administration's $644 million appropriations request for the S&T Directorate was $94 million (12.7%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $62 million (10.6%) above the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The request includes

- $30 million (9.6%) less than the enacted level for the Operations and Support appropriation, largely due to a $35 million (24.6%) reduction in mission support activities;

- Only $3 million of the Operations and Support request is for pay and retirement cost increases.38

- $19 million in the Procurement, Construction, and Improvements appropriation (which had no funding requested or provided in FY2020) for costs associated with the closure and sale of the Plum Island Animal Disease Center;39 and

- $82 million (19.5%) less than enacted for the Research and Development appropriation, due to a $64 million (16.6%) reduction in in-house research activities and a $19 million (46.3%) reduction in university-based research.40

Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office (CWMD)

The Administration's $377 million appropriations request for CWMD was $55 million (12.8%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $46 million (10.9%) below the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The request includes

- $7 million (3.7%) less than the enacted level for the Operations and Support appropriation, $40 million (18.7%) less than was requested for FY2020;

- This reduction is driven by a $5 million (40.7%) reduction in funding for the National Biosurveillance Integration Center's biosurveillance and early warning support on biological attacks and emerging pandemics,41 and an almost $3 million reduction in technical forensics operational readiness, which the request says is being funded by the National Nuclear Security Administration.42

- $1 million (0.4%) was requested for covering the increased pay and retirement costs.43

- $32 million (26.5%) less than the enacted level for the Procurement, Construction, and Improvements appropriation, largely driven by reductions to the Radiation Portal Monitor Replacement Program ($46 million, 68.1%) and Common Viewer program ($8 million, zeroed out);44

- $11 million (15.9%) less than the enacted level for the Research and Development appropriation, largely driven by a $7 million reduction in Technical Forensics and a $9 million (27.3%) reduction in detection capability activity;45 and

- $6 million (9.3%) less than the enacted level for the Federal Assistance appropriation, largely due to an $11 million (44.6%) reduction in funding for the Securing the Cities program.46

Headquarters Components (Title I)

Office of the Secretary and Executive Management (OSEM)

The Administration's $150 million appropriations request for OSEM was $28 million (15.9%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $9 million (6.4%) above the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The request includes

- $18 million (10.9%) less than enacted level for the Operations and Support appropriation, largely driven by a $15 million (25.9%) reduction in operations and engagement activities.

- The request included $5 million to pay for increased salary and retirement costs.47

- $10 million less than the enacted level for the Federal Assistance program, as the targeted violence grants funded in this component in FY2020 are funded in the FEMA request for FY2021.

Departmental Management Directorate (MD)

The Administration's $1.76 billion appropriations request for MD was $198 million (12.7%) above the FY2020 enacted level, and $204 million (13.1%) above the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. The request includes

- $220 million (18.6%) more than was enacted in FY2020 for the Operations and Support appropriation, $186 million of which is net transfers as a result of DHS transitioning away from using a working capital fund;

- Also included in this appropriations request is a $13 million increase to cover increased pay and retirement costs.48

- Of the remaining changes, most of the net increase is due to investments in information technology and cybersecurity.

- $22 million (5.7%) less than was enacted in FY2020 for the Procurement, Construction, and Improvement appropriation.

- Of the $359 million requested, over $200 million was for investments in DHS headquarters facilities, including St. Elizabeths; Mount Weather; and consolidation of headquarters leases.49

Analysis and Operations (A&O)

The Administration's $313 million appropriations request for A&O was $28 million (10.0%) above the FY2020 enacted level, and $36 million (13.0%) above the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020. Most of the details of the A&O budget request are classified. However, the request included a $6 million increase to cover increases in pay and retirement costs.50

Office of Inspector General (OIG)

The Administration's $178 million appropriations request for the OIG was $12 million (6.5%) below the FY2020 enacted level, and $8 million (4.5%) above the level of appropriations originally requested for FY2020.

- $5 million in additional funding is requested to cover increased pay and retirement costs.51

- The budget request includes a reduction of more than $15 million (16.5%) in OIG audits and investigations.52

- The budget justification notes that the OIG submitted a funding request of $196 million, which the OIG states "is essential to sustain FY 2020 operations into FY 2021 at the FY 2020 appropriated level and maintain oversight capacity commensurate with the Department's growth in several high-risk areas, including frontline security and infrastructure along the southern border, cybersecurity defenses, major acquisitions and investments, and accelerated hiring of law enforcement personnel."53

Administrative and General Provisions

Administrative Provisions

Administrative provisions are included at the end of each title of the DHS appropriations bill and generally provide direction to a single component within that title. In the FY2021 budget request, the Administration proposed a number of changes from the FY2020 enacted DHS appropriations measure, including

Deleting §106, which established the Ombudsman for Immigration Detention.

Adding a new section related to the proposed transfer of the Secret Service to the Department of the Treasury, which would allow for funds from the DHS OIG to be transferred to the Treasury OIG.54

Deleting §207-§212, which

- barred any new land border crossing fees;

- required an expenditure plan be submitted to Congress for the CBP Procurement, Construction, and Improvements appropriation before any of that appropriation could be obligated;

- constrained the use of the CBP Procurement, Construction, and Improvements appropriation, including limiting the types and locations of border barriers that could be constructed and requiring reporting to the appropriations committees on (1) the plans for barrier construction, (2) changes in barrier construction priorities, and (3) consultation with affected local communities, as well as an annual update to risk-based plan for improving border security;

- barred construction of barriers in certain locations;

- required statutory authorization for reducing vetting operations at the CBP's National Targeting Center; and

- directed certain CBP Operations and Support appropriations to humanitarian needs at the border and addressing health, life, and safety issues at Border Patrol facilities.55

- Deleting §216, which barred DHS from detaining or removing a sponsor, potential sponsor or the family member of sponsor or potential sponsor of an unaccompanied alien child on the basis of information from the Department of Health and Human Services, unless a background check reveals certain felony convictions or association with prostitution or child labor violators;56

- Deleting §227, which provided flexibility in allocating Coast Guard Overseas Contingency Operations funding;57

- Deleting §229, which bars the use of funds to conduct or implement an A-76 competition for privatizing activities at the National Vessel Documentation Center;58

- Deleting §231-§232, which were changes to permanent law (and thus no longer required inclusion in the bill) that

- allowed for continued death gratuity payments for the USCG if appropriated funding was unavailable for obligation; and

- categorized amounts credited to the Coast Guard Housing Fund as offsetting receipts.59

- Deleting §233-§236, which

- allowed the Secret Service to obligate funds in advance of reimbursement by other federal agencies for training expenses;

- barred the Secret Service from protecting agency heads other than the secretary of DHS, unless an agreement is reached with DHS to do so on a reimbursable basis;

- allowed the Secret Service to reprogram up to $15 million in its Operation and Support appropriation; and

- allowed flexibility for Secret Service employees on protective missions to pay for travel without regard to limitations on costs, with prior notification to the appropriations committees.60

- Adding §308, which requires a 25% nonfederal contribution for projects funded under the State Homeland Security Grant Program, Urban Area Security Initiative, Public Transportation Security Assistance, Railroad Security Assistance, and Over-the-Road Bus Security Assistance programs—currently there is no such cost share;61 and

- Adding §309, which would allow a transfer 1% of funding provided for the State Homeland Security Grant Program and Urban Area Security Initiative to FEMA Operations and Support for evaluations of the effectiveness of those programs.62

General Provisions

General provisions are included in the last title of the DHS appropriations bill and generally provide direction to the entire department. They include rescissions or additional budget authority in some cases. In the FY2021 budget request, the Administration proposed relatively few substantive changes to the general provisions enacted in the FY2020 bill. They sought to:

- Remove §530, which provided $41 million for reimbursement of extraordinary law enforcement costs for protecting the residence of the President;63

- Remove §532, which required that DHS allow Members of Congress and their designated staff access to DHS facilities housing aliens for oversight purposes;64 and

- Remove §537-§540, which rescinded prior year appropriations from various accounts.65

Appendix.

Glossary of Abbreviations

|

A&O |

Analysis and Operations |

|

BCA |

Budget Control Act (P.L. 112-25) |

|

CAS |

Common Appropriations Structure |

|

CBO |

Congressional Budget Office |

|

CBP |

United States Customs and Border Protection |

|

CISA |

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency |

|

CRS |

Congressional Research Service |

|

CWMD |

Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

FLETC |

Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers |

|

FTE |

full-time equivalents |

|

FY |

fiscal year |

|

ICE |

United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

|

MD |

(Departmental) Management Directorate |

|

OCO/GWOT |

Overseas Contingency Operations / Global War on Terror |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OSEM |

Office of the Secretary and Executive Management |

|

S&T |

Science and Technology Directorate |

|

TSA |

Transportation Security Administration |

|

USCG |

United States Coast Guard |

|

USCIS |

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services |

|

USSS |

United States Secret Service |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

These documents are available at https://www.dhs.gov/dhs-budget. |

| 2. | |

| 3. |

For a further discussion of these terms and concepts, see CRS Report R46240, Introduction to the Federal Budget Process. |

| 4. |

This leaves aside certain mandatory spending and trust fund resources not frequently addressed by Congress. |

| 5. |

Differences in scoring methodologies can be identified through analyses by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) required by Section 251(a)(7) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit and Control Act of 1985. These reports (known as "Seven-Day-After" reports) compare OMB and Congressional Budget Office (CBO) scoring for discretionary appropriations measures, and can be found at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/legislative/budget-enforcement-act-7-day-reports/. |

| 6. |

Scoring is generally done at the million-dollar level of granularity, while the appropriations committees track funding at the level of thousands of dollars. The CBO score includes adjustments to account for this difference, while the OMB does not. In addition, according to OMB: "CBO rounds each appropriation individually and adds the total ... while OMB rounds each level following a convention of rounding evenly split appropriations at the thousands level to the nearest whole even number in millions.... " Office of Management and Budget, Seven-Day-After Report for P.L. 116-93, Division D, Washington, DC, January 15, 2020, p. 11, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/7_Day_After_Report_Consolidated_1-14-20_Speaker.pdf. |

| 7. |

FY2019 was the first year that all components conformed to the new structure. The Coast Guard was the last to adopt it, and its Retired Pay appropriated mandatory spending is another appropriation that does not conform to the four categories. |

| 8. |

Two significant exceptions within DHS are USCIS, which uses fee collections to pay for most of its personnel, and the Federal Protective Service—now part of the Management Directorate—which is funded wholly through offsetting collections for services provided. |

| 9. |

The term "full-time equivalents" or "FTEs" is a measure of work equal to 2,080 hours per year. This is distinct from positions, which is a measure of the number of employees on board or to be hired. |

| 10. |

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, CBP-OS-14. Available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 11. |

Ibid., CBP-OS-55. |

| 12. |

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Procurement, Construction, and Improvements, Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, CBP-PC&I-4. |

| 13. |

Ibid., CBP-PC&I-8. |

| 14. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, FY2021 Budget in Brief, p. 27. |

| 15. |

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, ICE-OS-3. Available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 16. |

Ibid., ICE-OS-7. |

| 17. |

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Immigration Examinations Fee Account Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, ICE-IEFA-8. |

| 18. |

Department of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, TSA-O&S-8. Available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 19. |

Department of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration, Research and Development Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, TSA-R&D-8-13. |

| 20. |

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Coast Guard, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, USCG-O&S-8. Available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 21. |

Ibid., USCG-O&S-9. |

| 22. |

However, due to the proposed transfer, the requested USSS funding for FY2021 is generally not included in this report's totals. |

| 23. |

Department of the Treasury, United States Secret Service, Congressional Budget Justification and Annual Performance Plan and Report, FY 2021, February 10, 2020, USSS-23. |

| 24. |

Ibid. |

| 25. |

Department of Homeland Security, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, CISA-O&S-14-15. Available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 26. |

Ibid., CISA-O&S-46, 64. |

| 27. |

Department of Homeland Security, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, Procurement, Construction, and Improvements Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, CISA-PC&I-4, 9. |

| 28. |

Department of Homeland Security, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, Research and Development Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, CISA-R&D-8. |

| 29. |

Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, FEMA-O&S-6. Available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 30. |

Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Procurement, Construction, and Improvements Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, FEMA-PCI-5. |

| 31. |

Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Federal Assistance Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, FEMA-FA-7. |

| 32. |

Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Disaster Relief Fund Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, FEMA-DRF-9. |

| 33. |

Ibid. |

| 34. |

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, USCIS-O&S-5. USCIS justification available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 35. |

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Federal Assistance Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, CIS-FA-6. |

| 36. |

Department of Homeland Security, Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, FLETC-O&S-6. FLETC justification available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 37. |

Department of Homeland Security, Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, Procurement, Construction, and Improvements Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, FLETC-PCI-9-16. |

| 38. |

Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology Directorate, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, S&T-O&S-7. S&T justification available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 39. |

Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology Directorate, Procurement, Construction, and Improvements Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, S&T-PC&I-8. |

| 40. |

Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology Directorate, Research and Development Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, S&T-R&D-3-4. |

| 41. |

Department of Homeland Security, Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, CWMD-O&S-15. CWMD justification available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 42. |

Ibid., CWMD-O&S-17. |

| 43. |

Ibid., CWMD-O&S-6. |

| 44. |

Department of Homeland Security, Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction, Procurement, Construction, and Improvements Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, CWMD-PC&I-7. |

| 45. |

Department of Homeland Security, Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction, Research and Development Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, CWMD-R&D-3. |

| 46. |

Department of Homeland Security, Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction, Federal Assistance Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, CWMD-FA-5. |

| 47. |

Department of Homeland Security, Office of the Secretary and Executive Management, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, OSEM-O&S-7-8. OSEM justification available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 48. |

Department of Homeland Security, Management Directorate, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, MGMT-O&S-11. MD justification available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 49. |

Department of Homeland Security, Management Directorate, Procurement, Construction, and Improvements Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, MGMT-PC&I-5. |

| 50. |

Department of Homeland Security, Analysis and Operations, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, A&O-O&S-5. A&O justification available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 51. |

Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General, Operations and Support Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification, February 10, 2020, OIG-O&S-7. OIG justification available at https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2021. |

| 52. |

Ibid., OIG-O&S-10. |

| 53. |

Ibid., OIG-O&S-5. |

| 54. |

Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2021, Appendix, Washington, DC, February 10, 2020, p. 512, https://whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/. |

| 55. |

Ibid., pp. 539-540. |

| 56. |

Ibid., p. 540. |

| 57. |

Ibid., p. 541. |

| 58. |

Ibid. |

| 59. |

Ibid. |

| 60. |

Ibid. |

| 61. |

Ibid., p. 554. |

| 62. |

Ibid. |

| 63. |

Ibid., p. 567. |

| 64. |

Ibid. |

| 65. |

Ibid., pp. 567-568. |