Federal Income Tax Treatment of the Family Under the 2017 Tax Revisions

The federal income tax treatment of the family is affected by several major structural elements applicable to all taxpayers: amounts deductible from taxable income through standard deductions, personal exemptions, and itemized deductions; the rate structure (which varies across taxpayer types); the earned income credit and the child credit; and the alternative minimum tax. Some of these provisions only affect high-income families and some only low-income families, but they are the tax code’s fundamental structural features. They lead to varying tax burdens on families depending on whether the family is headed by a married couple or a single individual, whether children are in the family, and the number of children if so. These provisions also affect the degree to which taxes change when a couple marries or divorces.

The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97, popularly known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act) changed many of these fundamental provisions, although those changes are scheduled to expire after 2025. This report examines these temporary changes and how they affect families. The prior provisions (which will return absent legislative changes) are discussed in CRS Report RL33755, Federal Income Tax Treatment of the Family, by Jane G. Gravelle, which also includes the historical development of family-related provisions and some of the justifications for differentiating across families, especially with respect to the number of children.

The 2017 tax revision effectively eliminated personal exemptions claimed for the taxpayer, their spouse (if married), and any dependent (often referred to as the dependent exemption). However, the increased standard deduction more than offset these losses for taxpayers (and their spouses, if married). In addition, for many taxpayers, the increased child credit more than offset the losses from the eliminated dependent exemption. The tax revision also lowered rates for all three types of tax returns (joint, single, and head of household), although the effects were more pronounced for joint returns.

In general, the changes retain significant aspects of prior law. The income tax code after the 2017 tax revision remains progressive across income levels for any given type of family, although effective tax rates are slightly lower. Among families with the same ability to pay (using a measure that estimates how much additional income families need to attain the same standard of living as their size increases), families with children are still favored at the lower end of the income scale, whereas families with children are still penalized at the higher end of the scale. This favorable treatment toward families with children is extended further up into the middle-income level under the 2017 revisions due to the changes in the child credit.

The tax system is largely characterized by marriage bonuses (lower taxes when a couple marries than their combined tax bill as singles) through most of the income distribution, although marriage penalties still exist at the bottom (due to the earned income credit) and top (due to the rate structure) of the income distribution. The penalties at the top appear to be somewhat smaller in the new law due to changes in the rate structure and lower tax rates.

Federal Income Tax Treatment of the Family Under the 2017 Tax Revisions

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Structural Changes Made in the TCJA

- Standard Deduction, Itemized Deductions, and Personal Exemption and Child Credits

- Earned Income Tax Credit

- Rate Structure and Alternative Minimum Tax

- Treatment of Families with Different Incomes: Equity Issues

- Effects on Burdens at the Lower End of the Income Distribution

- Effects on Burdens at the Higher End of the Income Distribution

- Treatment of Families with Different Incomes

- Marriage Penalties and Bonuses

- Conclusion

Tables

- Table 1. Changes in Basic Allowances and Credits Made by P.L. 115-97, for 2018

- Table 2. Changes in Marginal Tax Rates, Joint Returns, 2018

- Table 3. Changes in Marginal Tax Rates, Head of Household Returns, 2018

- Table 4. Changes in Marginal Tax Rates, Single Returns, 2018

- Table 5. Income Levels With Positive Tax Liability, 2018

- Table 6. Average Effective Income Tax Rates by Type of Return, Family Size, and Income: Lower and Middle Incomes, New Law, 2018

- Table 7. Average Effective Income Tax Rates by Type of Return, Family Size, and Income: Higher Incomes

- Table 8. Average Effective Income Tax Rates for Joint Returns and Unmarried Couples, by Size of Income and Degree of Split: Lower and Middle Incomes, New Law, 2018

- Table 9. Average Effective Income Tax Rates for Joint Returns and Unmarried Couples, by Size of Income and Degree of Split: Higher Incomes, New Law, 2018

Summary

The federal income tax treatment of the family is affected by several major structural elements applicable to all taxpayers: amounts deductible from taxable income through standard deductions, personal exemptions, and itemized deductions; the rate structure (which varies across taxpayer types); the earned income credit and the child credit; and the alternative minimum tax. Some of these provisions only affect high-income families and some only low-income families, but they are the tax code's fundamental structural features. They lead to varying tax burdens on families depending on whether the family is headed by a married couple or a single individual, whether children are in the family, and the number of children if so. These provisions also affect the degree to which taxes change when a couple marries or divorces.

The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97, popularly known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act) changed many of these fundamental provisions, although those changes are scheduled to expire after 2025. This report examines these temporary changes and how they affect families. The prior provisions (which will return absent legislative changes) are discussed in CRS Report RL33755, Federal Income Tax Treatment of the Family, by Jane G. Gravelle, which also includes the historical development of family-related provisions and some of the justifications for differentiating across families, especially with respect to the number of children.

The 2017 tax revision effectively eliminated personal exemptions claimed for the taxpayer, their spouse (if married), and any dependent (often referred to as the dependent exemption). However, the increased standard deduction more than offset these losses for taxpayers (and their spouses, if married). In addition, for many taxpayers, the increased child credit more than offset the losses from the eliminated dependent exemption. The tax revision also lowered rates for all three types of tax returns (joint, single, and head of household), although the effects were more pronounced for joint returns.

In general, the changes retain significant aspects of prior law. The income tax code after the 2017 tax revision remains progressive across income levels for any given type of family, although effective tax rates are slightly lower. Among families with the same ability to pay (using a measure that estimates how much additional income families need to attain the same standard of living as their size increases), families with children are still favored at the lower end of the income scale, whereas families with children are still penalized at the higher end of the scale. This favorable treatment toward families with children is extended further up into the middle-income level under the 2017 revisions due to the changes in the child credit.

The tax system is largely characterized by marriage bonuses (lower taxes when a couple marries than their combined tax bill as singles) through most of the income distribution, although marriage penalties still exist at the bottom (due to the earned income credit) and top (due to the rate structure) of the income distribution. The penalties at the top appear to be somewhat smaller in the new law due to changes in the rate structure and lower tax rates.

Introduction

The federal tax treatment of the family is affected by several major structural elements of the income tax code applicable to all taxpayers: deductions such as the standard deduction, personal exemptions, and itemized deductions; the marginal tax rate structure (which varies by filing status); the earned income credit and the child credit; and the alternative minimum tax. Some of these provisions affect only high-income families and some only low-income families, but they are the tax code's fundamental structural features. They lead to varying tax burdens on families depending on whether the family is headed by a married couple or a single individual, whether children are in the family, and the number of children if so.

The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97, popularly known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, or TCJA) changed many of these fundamental provisions, although those changes are scheduled to expire after 2025. This report examines these temporary changes and how they affect families. The prior provisions (and ones that will return absent legislative changes) are discussed in a previous CRS report,1 which also includes the historical development of family-related provisions and some of the justifications for differentiating across families, especially with respect to the number of children.

This report does not consider other, more narrowly focused tax code provisions, such as those that apply only to certain types of income (e.g., special treatment for certain types of capital income or self-employment income) or particular additional benefits (e.g., benefits for the blind and elderly or for child care expenses).2

The first section discusses the structural changes made in the TCJA, and the following sections discuss equity issues and the marriage penalty.

Structural Changes Made in the TCJA

Taxes are determined by first subtracting deductions (either the standard deduction or the sum of itemized deductions) and personal exemptions (for the taxpayer, their spouse [if married filing jointly], and any dependents) from income to arrive at taxable income. Then the marginal rate structure is applied to this measure of taxable income. Finally, tax credits are subtracted from this amount to determine tax liability. Two of the major credits claimed by families are the earned income tax credit (EITC) and the child tax credit.3

The new law expanded the child credit for many taxpayers, although it did not change the earned income tax credit.4 In addition to these provisions, the law changed the exemption levels for the alternative minimum tax (a tax aimed at broadening the overall tax base and applying flat rates with a large fixed exemption), which is imposed if it is larger than the regular tax.

All amounts in this discussion are for 2018, the year the tax changes were first implemented. Some amounts will change in the future as they are indexed for inflation. The revision also changed the measure used to index for inflation to the chained consumer price index (CPI) rather than the basic CPI. The chained CPI takes into account changes in the mix of spending, and because spending tends to increase for goods with smaller price increases, the chained CPI is smaller than the basic CPI. For 2018, it only affected the EITC (in a minor way), as the other provisions (such as standard deductions and the rate structure) were stated explicitly in the tax revision.

Standard Deduction, Itemized Deductions, and Personal Exemption and Child Credits

In calculating their taxable income, taxpayers may subtract either the standard deduction or the sum of their itemized deductions. The standard deduction varies by the taxpayer's filing status: single (an unmarried individual with no dependents), joint (a married couple), and head of household (a single parent). The standard deduction is beneficial—that is, it results in a lower tax liability—when itemized deductions (such as for state and local taxes, mortgage interest, and charitable contributions) are smaller than the standard deduction amount. The standard deduction is annually adjusted for inflation.

Under prior law, taxpayers could claim a personal exemption for themselves and each family member. In addition, a child credit was allowed for children under the age of 17.5 The child credit was (and still is) partially refundable, so that taxpayers with no tax liability can receive some or all of the child credit as a refund greater than taxes owed. The refundable portion of the credit was limited to 15% of earned income in excess of $3,000. (The refundable portion of the child credit is sometimes referred to as the additional child tax credit or ACTC. The lowest-income taxpayers generally receive all of the child credit in the form of the ACTC.) Personal exemptions and child credits were phased out under prior law. Personal exemptions were indexed for inflation, but the child credit was not.

As shown in Table 1, the 2017 tax revision substantially increased the standard deduction and the maximum amount of the child credit while eliminating the personal exemption. It also increased the refundable portion of the child credit, both by increasing the maximum amount of the ACTC and by reducing the earned income amount used to calculate the ACTC. It also substantially increased the level at which the child credit is phased out.

|

Provision |

Prior Law |

Provision Enacted in |

|

|

Standard Deduction |

|||

|

Joint Returns |

$13,000 |

$24,000 |

|

|

Head of Household Returns |

$9,550 |

$18,000 |

|

|

Single Returns |

$6,500 |

$12,000 |

|

|

Personal Exemption |

$4,150 |

$0 |

|

|

Phaseout |

Phased out between $320,000 and $442,500, joint returns; between $293,350 and $415,850, head of household returns; between $266,700 and $389,200, single returns |

||

|

Child Credit |

$1,000 per child |

$2,000 per child |

|

|

Refundability Rules |

Up to 15% of income in excess of $3,000. Limited to $1,000 per qualifying child |

Up to 15% of income in excess of $2,500. Limited to $1,400 per qualifying child |

|

|

Phaseout |

Phased out by $50 for each $1,000, above the phaseout threshold, which was $75,000 for heads of households and $110,000 for married joint filers |

Phased out by $50 for each $1,000 above the phaseout threshold, which is $200,000 for head of household and $400,000 for married joint filers |

|

Source: Values for prior law for the standard deduction and personal exemption reflect indexed values from Rev. Proc. 2017-58, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-17-58.pdf. Other provisions are from the Internal Revenue Code.

For many taxpayers, the amount of income exempt from tax (i.e., the amount subtracted before applying tax rates) has increased under the 2017 tax revision. For example, prior to P.L. 115-97, a married couple with no children that claimed the standard deduction would have $21,300 in tax-exempt income (the combination of a standard deduction of $13,000 and two personal exemptions for the taxpayers of $4,150). Under current law, their first $24,000 would not be subject to tax. In general, the loss of personal exemptions for children was more than offset by increases in the maximum child credit from $1,000 per child to $2,000 per child.6 The act also provided a $500 credit for dependents that did not qualify for the child credit.7

Higher-income families with children also benefited from the increase in the new child credit's phaseout level, which was higher than the previous personal exemption and significantly higher than the prior-law child credit's phaseout range (see Table 1).

As under prior law, the standard deduction will be annually adjusted for inflation and the child credit (or family credit) will not be adjusted for inflation (with the exception of the $1,400 limit on refundability, which is indexed). The prior-law personal exemption was indexed annually for inflation. Were these provisions to be continued over a long period, the child credit would continually decline in real value, whereas the prior-law personal exemption would not. Moreover, the new inflation index is less generous than the prior one.

The tax change also restricted itemized deductions. Although it retained the major itemized deductions for mortgage interest, state and local taxes, and charitable contributions, it limited the deduction for state and local taxes to $10,000, reduced the cap on mortgages with interest eligible for the deduction from $1 million to $750,000, and eliminated a number of other minor itemized deductions. These amounts are not indexed for inflation. As a result of increases in the standard deduction and restrictions on itemized deductions, about 13% of taxpayers are expected to itemize deductions, compared to 30% under prior law.8 Analysis suggests most of those who continue to itemize are higher income.

Earned Income Tax Credit

The other major tax credit for families under current law is the earned income tax credit (EITC).9 This credit is aimed at helping lower-income workers and is fully refundable, meaning that those with little to no income tax liability can receive the credit's full amount. While the credit is generally available to all low-income workers, the credit formula is much more generous for families with children, and the majority of benefits go to families with children.10

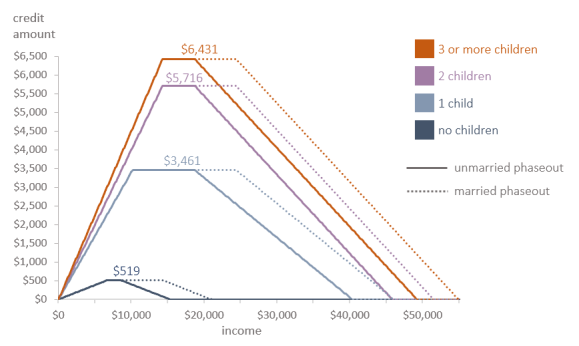

The EITC varies based on a recipient's earnings: the credit equals a fixed percentage (the credit rate) of earned income until it reaches its maximum level. The EITC then remains at its maximum level over a subsequent range of earned income, between the earned income amount and the phaseout amount threshold. Finally, the credit gradually phases out to zero at a fixed rate (the phaseout rate) for each additional dollar of adjusted gross income (AGI) (or earned income, whichever is greater) above the phaseout amount threshold. The credit rate, earned income amount, maximum credit, and phaseout amount threshold all vary by number of children, and are more generous for families with more children, as illustrated in Figure 1.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS) calculations based on information in Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Revenue Procedure 2018-18 and Internal Revenue Code Section 32. In this simplified example, adjusted gross income (AGI) is assumed to equal earned income. |

In 2018, the maximum credit amounts were $519, $3,461, $5,716, and $6,431 for families with zero, one, two, or three or more children, respectively. In addition, the phaseout amount threshold is higher for married couples than for unmarried recipients. Hence, the income level at which the credit begins to phase out is slightly more than $5,000 greater for married joint filers than it is for unmarried filers (heads of households and singles).

The 2017 revision made no explicit changes to the EITC, but the change in the inflation indexing formula slightly lowered the credit's value. For example, the credit's maximum value for a family with three or more children under prior law would have been $6,444, rather than $6,431 for a family with three or more children under the revision.11

A taxpayer with no qualifying children must be between 25 and 64 years of age to be eligible for the EITC.

Rate Structure and Alternative Minimum Tax

The 2017 tax revision also altered the statutory marginal tax rates that apply to taxable income.12 There are currently seven marginal tax rates, and the income ranges over which they apply (tax brackets) differ based on the taxpayer's filing status, with brackets at the lower rates half the width for singles as those of married couples (who file jointly) and heads of household in between. The width of the bracket determines how much income is taxed at a given rate and the wider the brackets the more income is taxed at lower rates. That means singles (and to a lesser extent heads of households) are subject to higher tax rates at lower levels of income than married couples. Under prior law, most taxpayers were subject to tax rates of 10% and 15%. The 10% rate applied for the first $19,050 of taxable income for joint returns, the first $13,600 for head of household returns, and the first $9,525 for single returns. The 15% bracket ended at $77,400 of taxable income for joint returns, $51,850 for heads of households, and $38,700 for singles. The tax revision retained the 10% rate, but reduced the 15% rate to 12%.

Above those income levels, rates of 25%, 28%, 33%, 35%, and 39.6% applied, and single bracket widths were less than half as wide as the equivalent married brackets. The 2017 revisions reduced those rates by amounts ranging from 3 to 9 percentage points, with new rates of 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%.13 Under prior law, the top rate of 39.6% applied to taxable income over $480,050 for joint returns. The new law reduced the top rate to 37% and applied it to taxable income over $600,000; the remaining taxable income that had been subject to a 39.6% rate is taxed at 35%. Under prior law, the 39.6% top rate was reached at $426,700 for singles; under the revision, the new top rate of 37% applies to taxable income over $500,000 for singles.

The law also revised the alternative minimum tax. Under prior law, the alternative minimum tax imposed a 26% tax rate on alternative minimum taxable income above $86,000 for married couples and $55,400 for unmarried tax filers. The exemption began to phase out at $164,100 for married couples and $123,100 for singles. A higher rate of 28% applied to AMT taxable income above $191,500 for joint returns and $95,750 for single returns. AMT income begins with ordinary taxable income and adds back the standard deduction, personal exemptions, and state and local tax deductions for itemizers, as well as some other tax preferences (such as tax-exempt interest from private activity bonds and accelerated depreciation).

The tax revision left the AMT's basic structure unchanged, but increased the exemption amounts to $109,400 for married couples and $70,300 for single returns. It also increased the phaseout point for the exemption to $1,000,000 for joint returns and $500,000 for singles.

Other elements of the 2017 tax revision affected whether a taxpayer would be subject to the AMT. Whether the AMT applies depends on deductions from the regular tax compared to the AMT exemption, as well as the tax rates. Lower regular tax rates and a higher standard deduction increase the chance a taxpayer is subject to the AMT, whereas higher AMT exemptions, elimination of personal exemptions, and the limit on the deduction for state and local taxes decrease the chance a taxpayer is subject to the AMT. The rate brackets and AMT amounts are indexed annually for inflation.

At higher income levels (up to slightly over $300,000 of taxable income for joint returns and about half that amount for other returns), several factors contribute to lower tax liabilities under the 2017 tax revision, primarily the relatively large reduction in marginal tax rates, as shown in the tax rates in Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4. As indicated in those tables, as a result of P.L. 115-97, marginal rates increase somewhat over narrow bands of higher income levels, particularly for heads of households and to a lesser extent single returns, before declining again.

|

Taxable Income ($) |

Prior Law |

New Law |

Difference |

|

$0-$19,050 |

10% |

10% |

0% |

|

19,050-77,400 |

15 |

12 |

-3 |

|

77,400-156,150 |

25 |

22 |

-3 |

|

156,150-165,000 165,000-237,950 |

28 28 |

22 24 |

-6 -4 |

|

237,950-315,000 |

33 |

24 |

-9 |

|

315,000-400,000 |

33 |

32 |

-1 |

|

400,000-424,950 |

33 |

35 |

2 |

|

424,950-480,050 |

35 |

35 |

0 |

|

480,050-600,000 |

39.6 |

35 |

-4.6 |

|

Over 600,000 |

39.6 |

37 |

-2.6 |

Source: Values for prior law reflect indexed values from Rev. Proc. 2017-58, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-17-58.pdf. Other provisions are from the Internal Revenue Code.

|

Taxable Income ($) |

Prior Law |

New Law |

Difference |

|

$0-$13,600 |

10% |

10% |

0% |

|

13,600-51,800 |

15 |

12 |

-3 |

|

51,8000-82,500 |

25 |

22 |

-3 |

|

82,500-133,850 133,850-157,500 |

25 28 |

24 24 |

-1 -4 |

|

157,500-200,000 |

28 |

32 |

4 |

|

200,000-216,700 |

28 |

35 |

7 |

|

216,700-424,950 |

33 |

35 |

2 |

|

424,950-453,350 |

35 |

35 |

0 |

|

453,350-500,000 |

39.6 |

35 |

-4.6 |

|

Over 500,00 |

39.6 |

37 |

-2.6 |

Source: Values for prior law reflect indexed values from Rev. Proc. 2017-58, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-17-58.pdf. Other provisions are from the Internal Revenue Code.

|

Taxable Income ($) |

Prior Law |

New Law |

Difference |

|

$0-$9525 |

10% |

10% |

0% |

|

9,525-38,700 |

15 |

12 |

-3 |

|

38,700-82,500 |

25 |

22 |

-3 |

|

82,500-93,700 93,700-157,500 |

25 28 |

24 24 |

-1 -4 |

|

157,500-195,450 |

28 |

32 |

4 |

|

195,450-200,000 |

33 |

32 |

-1 |

|

200,000-424,950 |

33 |

35 |

2 |

|

424,950-426,700 |

35 |

35 |

0 |

|

426,700-500,000 |

39.6 |

35 |

-4.6 |

|

Over 500,000 |

39.6 |

37 |

-2.6 |

Source: Values for prior law reflect indexed values from Rev. Proc. 2017-58, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-17-58.pdf. Other provisions are from the Internal Revenue Code.

The changes in tax rates are only one factor determining tax liabilities, as other tax code features—including broadly applicable features discussed in this report and others that apply to a narrower range of taxpayers—can affect tax liability.

Treatment of Families with Different Incomes: Equity Issues

The new income tax code (as well as the income tax under prior law) is progressive: as income increases and taxpayers have an increased ability to pay, tax rates rise. Studies generally suggest, however, that after taking all of the 2017 tax revision's provisions into account, higher-income groups tend to have the largest percentage increase in after-tax income.14 Hence, while still progressive, the new income tax is less progressive in comparison to the prior-law income tax. In addition, as time goes on, the relative tax burden on low-income families is expected to increase. This increase at the lower end of the income distribution is partially due to the new inflation indexing provision, which will reduce the earned income credit's value for low-income working families. The increased tax burden also reflects the loss of health care subsidies due to the elimination of the penalty for not purchasing health insurance. The decreased tax burdens (relative to prior law) for high-income individuals also reflect, in this distributional estimate, lower taxes' effects on capital income (including lower corporate tax rates and the pass-through deduction for business income), which affect higher-income individuals, who own most of the capital.

Effects on Burdens at the Lower End of the Income Distribution

The tax change had no effect on after-tax income in 2018 for low-income families that already had effectively no or negative tax liability and did not have enough income to be eligible for the maximum child credit. In future years, the inflation indexing could eventually reduce the earned income credit's value. As incomes rise, families with children will tend to benefit more than families without children, primarily due to the expanded child credit. These effects can be illustrated by comparing the prior- and current-law breakeven levels. The breakeven level is the amount of income at which a taxpayer begins to owe income taxes (i.e., the level at which tax liability turns from negative or zero to positive). Table 5 shows these levels for married and single-headed families with zero to three children.15

|

Family Type |

Number of Children |

Family Size |

Prior-Law Income ($) |

New-Law Income ($) |

Difference in Income ($) |

||||

|

Single |

0 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Married |

0 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Head of Household |

1 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

Source: CRS calculations.

The smallest increase in the income level at which taxes begin to be owed is for singles with no children. These taxpayers began to owe taxes when income was $12,669 under prior law, but begin to owe at $13,419 under current law, an increase of $750. Under prior law, this income level was in part a result of the standard deduction and personal exemption (a combined $10,650 that was exempt from tax) and in part a result of a reduced EITC (the taxpayer's income resulted in a partially phased out credit). Under current law, a greater amount of income is exempt from tax—$12,000 compared to $10,650—and the EITC is slightly reduced as a result of the new inflation adjustment. A married couple without children begins to pay taxes when their income is $24,000 under current law, compared with $21,300 under prior law, a $2,700 increase entirely driven by the changes in the personal exemptions and the standard deduction. For these taxpayers, under prior law their first $21,300 was exempt from tax as a result of the standard deduction and personal exemptions, and they were ineligible for the EITC at this income level because the credit was entirely phased out. Under current law, their first $24,000 is exempt from tax as a result of the increased standard deduction (and they remain ineligible for the EITC).

The breakeven point for families with children is greater than the standard deduction (or under prior law, the standard deduction and personal exemptions) as a result of the EITC (although it is phased out from its maximum level) and the child credit. Although the increased standard deduction increases exempt levels and the additional $1,000 of the child credit is the equivalent of a $8,333 deduction for each child at the new tax bracket these income levels fall into ($1,000/.12), these income levels are mostly still in the earned income credit's phaseout range. Thus, although taxpayers gain from the increased deductions and child credits as income rises, they lose earned income tax credits, making the increase in the exemption level smaller. The benefit increases when the increased income levels tend to be largely out of the EITC's phaseout range (which is largely the case for families with three children).

Lower-income families either receive a negligible benefit (for those without children) or a significant benefit (for those with children) because the new child credit is more generous than the prior personal exemption in terms of tax savings. As income rises, the child credit continues to contribute to lower taxes. It is not until marginal tax rates reach 24% (which occurs at $165,000 of taxable income for a joint return) that the increased child credit has the same value as the prior personal exemption in terms of tax savings. The moderate income levels also benefit from lower tax rates, as the 15% rate that applies to taxable income from $19,050 to $77,000 is reduced to 12%.

Effects on Burdens at the Higher End of the Income Distribution

At higher income levels, lower tax rates (which are quite large for taxable incomes of slightly more than $300,000 for joint returns and about half that amount for other returns) account for lower taxes, as shown in the tax rates in Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4. As indicated in those tables, rates increase at somewhat higher levels—particularly for head of household and, to a lesser extent, single returns—before declining again.

For joint returns, the larger rate reductions occur between $156,150 and $316,000 of taxable income, as well at incomes of $480,050 to $600,000, while these reductions appear at lower income levels for head of household and single returns. Taxpayers are also less likely to pay the alternative minimum tax. Although regular tax rates are lowered, two factors reduce the AMT's scope. One is the significant increase in the AMT exemption. In addition, taxpayers at the upper end of the distribution have smaller itemized deductions for state and local taxes, which are a preference item for the AMT. Larger families also have a reduction in the difference between the regular and AMT base, as personal exemptions and standard deductions were part of that base under prior law, but child credits were not. Replacing personal exemptions for children with the child credit reduces the difference between the AMT and the regular base.

At higher income levels, losing the full state and local tax deduction can increase tax burdens. The average state and local tax deduction is about 5% of income; evaluated at a 35% or 37% tax rate, the loss is equivalent to a two percentage point change in marginal tax rates.

For high-income families with children, the increase in the phaseout levels lowers burdens, particularly as compared to the phaseout for the preexisting tax credit, although the benefit relative to income diminishes as income rises because of the fixed dollar amount.

Overall data on distributional effects show significantly larger effects at high income levels, but some of the estimated relatively larger benefit to high-income taxpayers is due to reductions in the tax burden on capital income, including the pass-through deduction (which allows a 20% reduction in capital income for some earnings from unincorporated business) and the lower corporate tax rate, which benefits higher-income individuals, who receive most of the capital income. The effect of structural features at high income levels is ambiguous because the tax change raised tax rates for certain portions of taxable income and lowered them for others, and also capped the state and local tax deduction.

Treatment of Families with Different Incomes

This section examines the patterns of both vertical equity (how tax rates change as incomes rise) and horizontal equity (how tax rates change across different types of families with the same ability to pay using effective tax rate calculations [taxes as a percentage of income]). These rates can also be compared to those calculated for prior law in a previous CRS report.16

With respect to horizontal equity, this report uses an equivalency scale similar to the one used to calculate variations in poverty lines by family size. An equivalency scale estimates how much income families of different sizes and compositions need to achieve the same standard of living.17 In defining families that have the same ability to pay, CRS used an adjustment based on a research study that reviewed a broad range of equivalency studies and is similar to that used for adjusting official poverty levels for different family sizes. The scale has a smaller adjustment for children than for adults. The equivalency scale also accounts for the common use of resources (such as a kitchen or bathroom) in a family, which means increases in required income are not proportional to family size. Under this standard, a single person requires about 62% of the income of a married couple; a couple with four children requires about three times the income. Thus, compared to a married couple with no children with $20,000 of income, an equivalent single person would need slightly over $12,000, and a married couple with four children would need $60,000 to have the same standard of living.

Provisions included in the calculations are the rate structure, the larger of the standard deduction or itemized deductions (the latter are assumed to be 12.7% of income, with 5.3% of income reflecting the state and local tax deduction included in the alternative minimum tax base, based on the latest tax data),18 personal exemptions, the earned income credit, the child credit, and the alternative minimum tax.

Table 6 reports the 2018 effective tax rates for low- and middle-income taxpayers at different levels of income, for family sizes of up to seven individuals, and for the three basic types of returns—single, joint, and head of household. Table 7 reports the tax rates for higher-income families. The column heading indicates the income level for married couples. Effective tax rates in each column reflect the effective tax rates of families with the same standard of living. The rates for different families should be compared by looking down the columns. For example, in Table 6, a married couple with no children (the reference family) and $25,000 in income pays 0.4% of their income in taxes, but a married couple with one child with the same ability to pay (i.e., same standard of living at about $30,844 of income) receives a subsidy (i.e., on net they get a refund greater than taxes owed) of 12.1% of their income, whereas a single with an equivalent before-tax standard of living pays 2.2% of income in taxes. Overall, these effective tax rates indicate that low-income families with children receive significant benefits from the income tax, compared to those with similar abilities to pay but without children.

These numbers assume that taxpayers (and their children) are eligible for both the child credit and the EITC. These are illustrative calculations that do not account for any other tax preferences and are designed to show how the tax law's basic structural, family-related features affect burdens.

Table 6. Average Effective Income Tax Rates by Type of Return, Family Size, and Income: Lower and Middle Incomes, New Law, 2018

|

Type-Size |

Income Level for Reference Family: Married Couple Without Children (Joint-2) |

|||||||||||

|

$10,000 |

$15,000 |

$25,000 |

$50,000 |

|||||||||

|

Single-1 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-2 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-3 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-4 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-5 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-6 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-7 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-2 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-3 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-4 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-5 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-6 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-7 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

Source: CRS calculations.

Note: The dollar amounts refer to the income for a married couple with no children; larger families in each column would need more income to maintain the same standard of living, and singles and heads of household with two family members (one child) would need less income to maintain the same standard of living.

Table 7. Average Effective Income Tax Rates by Type of Return, Family Size, and Income: Higher Incomes

|

Type–Size |

Income Level for Reference Family Married Couple Without Children (Joint-2) |

|||||||||||

|

$75,000 |

$100,000 |

$250,000 |

$500,000 |

|||||||||

|

Single-1 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-2 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-3 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-4 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-5 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-6 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Joint-7 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-2 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-3 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-4 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-5 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-6 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

H/H-7 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

Source: CRS calculations.

Note: The dollar amounts refer to the income for a married couple with no children; larger families in each column would have more income, and singles and heads of household with two family members (one child) would have less income.

Across each family type, effective tax rates are progressive, increasing as income increases. Compared to prior law, tax rates change relatively little at the lowest income level due to the lack of change in the earned income credit and because the child credit increases by a limited amount (about $75) for many of the poorest families. As incomes rise into the lower-middle, middle-, and upper-middle-income levels, rates fall slightly for families without children, whereas families with children have significant reductions in effective tax rates due to the increase in the maximum child credit and the increases in the child credit phaseout levels. At the highest income levels, effects range from small rate cuts to small rate increases, which reflect the trade-off between the changes in rates and the reductions in itemized deductions. In contrast with prior law, none of the examples in these tables are subject to the AMT.19

These tables suggest that the pattern of tax burden by family size varies across the income scale, and reflects the interactions of the earned income credit, the child credit, and graduated rates, including phaseout effects. Moreover, the variation across families that have the same ability to pay is substantial. At low incomes, families with children, whether headed by a married couple or a single parent, are favored (i.e., receive significant subsidies from the tax code) because of the EITC and the child credit.20 The largest negative tax rates tend to accrue to returns with around two or three children, because the largest EITCs are available for three or more children and the child credits increase with the number of children. The rate increases (or rather, negative rates decline in absolute value) because larger families need more income, which may begin to phase them out of the EITC.

As incomes rise, families with children are still favored, but the largest families have the largest subsidies or the smallest tax rates, because the child credit lowers taxes more for these families. Eventually, large families begin to be penalized because the value of the child credit and personal exemptions relative to income declines and larger families that require more income are pushed up through the rate brackets. As incomes reach very high levels, however, the rates converge as the tax approaches a flat tax. Note that itemized deductions are assumed to be a constant fraction of income, and thus a proportional exclusion, except when the $10,000 limit on state and local tax deductions is binding.

Compared to prior law, the new system retains and expands the favorable treatment of families with children through most of the income spectrum. This effect occurs partly because the EITC rate is much lower for single taxpayers or two-member joint returns with no qualifying children than it is for families with children. Also, if one accepts the ability-to-pay standard, the EITC has an inappropriate adjustment for family size. To achieve equal tax rates based on the ability-to-pay standard, the amount on which the EITC applies and the income at which the phaseout begins should be tied to family size but the EITC credit rate should be the same for all families. Changing the rate, as was done in 1990 and retained when the EITC was expanded in 1993, does not accomplish equal treatment across families of different sizes, providing too much adjustment for some families and not enough for others.

The child credit also contributes to the favorable treatment of families with children, including in the middle- and upper-middle-income levels, where it is not phased out. The greater refundability level, the increased size of the credit beyond that needed to replace the personal exemption at most income levels, and the significantly increased phaseout levels all make the child credit a significant factor in increasing the favorable treatment for families with children.

Tax rates also differ for families without children (singles and married couples). At most income levels, childless singles have higher effective tax rates than childless married couples. This effect reflects efforts to eliminate marriage penalties, which in turn result in a tax penalty for single individuals.

Other aspects of the tax system should also be considered, such as the child care credit and the treatment of married couples where only one individual works outside the home. These families are better off because the spouse not employed outside the home can perform services at home that result in cost savings, perform household tasks that increase leisure time for the rest of the family, or enjoy leisure. The value of this time, which is not counted in the measured transactions of the economy, is referred to as imputed income. This imputed income is not taxed, and it would probably be impractical to tax it. Nevertheless, the tax burden as a percentage of cash plus imputed income is lower for such a family.

Marriage Penalties and Bonuses

Because of the progressive rate structure, taxes can be affected by marriage, introducing either a penalty or a bonus when two individuals get married. Concerns about the marriage penalty reflect a reluctance to penalize marriage in a society that upholds such traditions. As the tax law shifted in the past to reduce the marriage penalty, it also expanded marriage bonuses. Studies of this issue indicate that the tax system favors marriage, conferring significant bonuses on married couples (or penalties on singles).21

The new law retains many of the elements that affect marriage penalties and bonuses, including wider tax brackets for joint returns (which eliminate marriage penalties and produce bonuses for those without children in the middle-income brackets), the more generous rate structure for head of household (which affects penalties and bonuses for families with children), and marriage penalties embedded in the alternative minimum tax. Under the new rate structure, the income levels at which marriage penalties are precluded because of the doubling of the brackets are higher. At the same time, the law also introduces a new potential source of a marriage penalty at high income levels by retaining the same dollar cap on state and local tax deductions for both joint and single returns.

These choices have consequences not only for incentives but for equitable treatment of singles and married couples. As shown above in Table 6 and Table 7, in the middle-income brackets, where the marriage penalty was largely eliminated, singles with the same ability to pay are subject to higher taxes than married couples. Singles benefit at lower income levels because their lower required incomes do not phase them out of the earned income credit. In contrast, lower-income married taxpayers are more likely to be subject to marriage penalties because of the EITC's structure. Under prior law, at very high incomes, married couples may have paid a larger share of their income because of marriage penalties that remained in the AMT and the upper brackets of the rate structure, but these effects do not appear in any of the current-law examples, in part because the AMT does not apply.

This section explores the treatment of married couples and singles in an additional dimension by assuming that singles live together and share the same economies of scale that married couples do. These individuals could be roommates, but they could also be partners who differ from married couples only in that they are not legally married.22 Single individuals who live together in the same fashion as married couples have the same ability to pay with the same income. However, remaining single can alter their tax liability, causing it to either rise or fall, depending on the split of income between the two individuals. If one individual earns most of the income, tax burdens will be higher for two individuals who are not married than for a married couple with the same total income, because the standard deductions are smaller and the rate brackets narrower (up to the 35% tax rate, tax brackets for singles are half those of joint returns). If income is evenly split between the two individuals, there can be a benefit from remaining single. Married individuals have to combine their income, and the rate brackets for joint returns in the higher-income brackets, although wider than those for single individuals, are not twice as wide. At all levels they are not twice as wide as for heads of household. In addition, the earned income credit contains marriage penalties and bonuses.

The marriage penalty or bonus might, in the context of the measures of household ability to pay, also be described as a singles bonus or penalty. In any case, in considering this issue's incentive and equity dimensions, these families' tax rates should be compared across family marital status at each income level.

Table 8 and Table 9 show the average effective tax rates for married couples and for unmarried couples with the same combined income, both where income is evenly split and where all income is received by one person. In one case there is no child and in the other one child. These income splits represent the extremes of the marriage penalty and the marriage bonus. The same reference income classes and equivalency scales as in Table 6 and Table 7 are used.

Note that uneven income splits in the case of a family with a child can yield different results depending on whether the individual with the income can claim the child and therefore receive the benefits of the head-of-household rate structure, the higher earned income credit, the dependency exemption, and the child credit. If not, that individual files as a single.

Table 8. Average Effective Income Tax Rates for Joint Returns and Unmarried Couples, by Size of Income and Degree of Split: Lower and Middle Incomes, New Law, 2018

|

Type–Size |

Income Level for Married Couple |

|||||||||||

|

$10,000 |

$15,000 |

$25,000 |

$50,000 |

|||||||||

|

No Child |

||||||||||||

|

Joint |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Single 50/50 Split |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Single 100/0 Split |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

One Child |

||||||||||||

|

Joint |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

50/50 Split, One Single, One Head of Household |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

100/0 Split, Single Return |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

100/0 Split, Head-of-Household Return |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

Source: CRS calculations.

Table 9. Average Effective Income Tax Rates for Joint Returns and Unmarried Couples, by Size of Income and Degree of Split: Higher Incomes, New Law, 2018

|

Type–Size |

Income Level for Married Couple |

|||||||||||

|

$75,000 |

$100,000 |

$250,000 |

$500,000 |

|||||||||

|

No Child |

||||||||||||

|

Joint |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Single 50/50 Split |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Single 100/0 Split |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

One Child |

||||||||||||

|

Joint |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

50/50 Split, One Single, One Head of Household |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

100/0 Split, Single Return |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

100/0 Split, Head-of-Household Return |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

Source: CRS calculations.

The tables indicate that both marriage penalties and bonuses persist. In the case of families without children, however, penalties do not exist in the middle-income ranges, only bonuses. In this case, singles who live together and have uneven incomes would see their tax rates fall if they got married. Both bonuses and penalties exist at the lower income levels because of the earned income tax credit. If income is evenly split, the phaseout ranges are not reached as quickly for singles because each of the partners has only half the income. If all of the income is earned by one of the singles in the single partnership, phaseout of the credit still occurs and the individual also has a smaller standard deduction, and thus pays a higher tax. The smaller deductions and narrower rate brackets also cause the higher tax rates through the middle-income brackets. At very high income levels, marriage penalties can also occur. The penalty is due to not doubling the rate brackets after the 12% bracket. In addition, the dollar limit on the deduction of state and local taxes is the same for married couples and individual taxpayers, so that if two singles with high incomes and high state and local taxes marry, they can lose $10,000 in deductions. At the same time, taxpayers tend not to be subject to the AMT, which retains marriage penalties (by having an exemption for joint returns that is less than twice that for single returns).

As compared to prior law, marriage penalties at higher income levels are mixed. In some cases penalties are lower, presumably due to the extension of the reach of the double width of rate brackets for singles versus joint returns, as well as lower tax rates in general and the AMT's more limited reach. In some cases penalties are higher due to the state and local tax deduction limit.23

Matters are more complex for families with children. Table 8 and Table 9 illustrate this effect for a family with one child. At the lowest income level, and a 50/50 split, one of the singles files a single return with a very small negative rate because of the small earned income credit for those without children, whereas the other claims a child and has a much higher negative tax rate than a married couple because there is no phaseout of benefits. The combination also involves a smaller child credit because it is not completely refundable. The combined result is a lower benefit than that of a married couple, and thus there is a marriage bonus. This income split eventually leads to a marriage penalty because of the favorable head-of-household standard deduction and rate structure, as well as the state and local tax deduction cap.

With one of the pair earning all of the income, the results depend on whether the partner with the income can claim the child. If that person cannot, the tax burden is higher throughout the income scale, reflecting the loss of benefits from the child via credits and the rate structure. If the person with the income can claim the child (thus using the more favorable head-of-household schedule and receiving a child credit), joint returns are still favored (except at the lowest income levels), but not by nearly as much.

Which of these last two assumptions seems more likely depends on the circumstances. When couples divorce, they typically move to different residences, and the most usual outcome is that the mother, who typically has lower earnings, has the child. According to the Census Bureau, 83% of children who live with one parent live with their mother.24 In that case, there would likely be a marriage bonus. If the couple divorce but live together, presumably the higher-income spouse would claim the child. However, if a couple never married and the child is only related to one parent, that person, more likely the mother and more likely to have low income, would claim the child. If such a couple married and had low incomes, they could obtain the earned income credit, and a study of low-income families indicates that this latter effect, the bonus, is the EITC's most common effect.25

Which circumstances are more characteristic of the economy? Note first that, although people refer to the marriage penalty for a particular family situation or the aggregate size of the marriage penalty, it is really not possible, in many cases, to determine the size of the penalty or bonus. The effect of the assignment of a child is demonstrated in Table 8 and Table 9, but other features matter. Only when a married couple has only earned income, no dependent children, and no itemized deductions or other special characteristics, and only if it is assumed that their behavior would not have been different if their marital status had been different, can one actually measure the size of the marriage penalty or bonus. There is no way to know which of the partners would have custody of the children and therefore be eligible for head-of-household status and the accompanying personal exemptions and child credits.

If the marriage bonus is viewed instead as a singles penalty on cohabitating partners, the share of the population affected is limited to less than 10% of households.26 About a third of those have children. Cohabitating partners are more likely than roommates to fully enjoy the consumption of joint goods that would equate them to married couples.

Conclusion

The 2017 tax revision continued, and in some cases expanded, the favorable treatment of families with children in the lower and middle income levels on an ability-to-pay basis. At the lowest incomes, this treatment was maintained largely due to the EITC's preexisting effects, although increasing the refundable child tax credit added to this favorable treatment. More favorable treatment was increased and extended up through the income classes because of the increase in the child tax credit amount and the increase in the income level at which the credit is phased out. At the highest income levels, rate changes tended to favor joint returns over singles and heads of household, largely due to the rate structure.

As was the case with prior law, marriage bonuses occur through most income brackets, but penalties can exist at the lower end of the income distribution, particularly for families with children in which the lower income earner has custody of children, due to the earned income credit and the child credit. The rate structure continues to lead to a potential marriage penalty at high income levels. The 2017 revisions also introduced a new provision that could contribute to the marriage penalty at high incomes: the $10,000 limit on itemized deductions for state and local taxes, which is the same amount for married and single individuals.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

CRS Report RL33755, Federal Income Tax Treatment of the Family, by Jane G. Gravelle. |

| 2. |

A review of all of the legislation's provisions can be found in CRS Report R45092, The 2017 Tax Revision (P.L. 115-97): Comparison to 2017 Tax Law, coordinated by Molly F. Sherlock and Donald J. Marples. |

| 3. |

See CRS Report R45145, Overview of the Federal Tax System in 2019, by Molly F. Sherlock and Donald J. Marples. |

| 4. |

The earned income tax credit was altered slightly by the shift to using the chained consumer price index to adjust phase-in and phaseout levels. |

| 5. |

See CRS Report R41873, The Child Tax Credit: Current Law, by Margot L. Crandall-Hollick for a further discussion of the child tax credit. |

| 6. |

A $1,000 increase in the credit is more beneficial than the personal exemption at tax rates of 24% and below. For married couples this level is not exceeded until taxable income reaches $315,000 in 2018. In addition, the requirement that taxpayers provide the Social Security Number (SSN) for a child for whom they claim the credit may make some previously eligible taxpayers ineligible for the credit (although they may still be eligible for the $500 credit for other dependents). The personal exemption did not include an SSN requirement. |

| 7. |

A $500 credit is the equivalent of a personal exemption at a 12% tax rate. For married couples that level is not exceeded until taxable income reaches $77,400. |

| 8. |

See Robert McClelland, "Anybody Can Itemize their Deductions. But Most Don't Want To," Tax Policy Center, September 5, 2019, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/anybody-can-itemize-their-deductions-most-dont-want. |

| 9. |

See CRS Report R43805, The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): An Overview, by Gene Falk and Margot L. Crandall-Hollick for further discussion. |

| 10. |

The EITC for taxpayers with no qualifying children is sometimes referred to as the childless EITC. Whereas some workers eligible for this credit may indeed have no children, others may have children that do not reside with them for more than half the year, and others may live with children that for various reasons they cannot claim for the EITC (e.g., an individual living with but not married to a mother with children from another relationship). |

| 11. |

See Rev. Proc. 2017-58, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-17-58.pdf for values under the prior indexing method. |

| 12. |

See CRS Report R45092, The 2017 Tax Revision (P.L. 115-97): Comparison to 2017 Tax Law, coordinated by Molly F. Sherlock and Donald J. Marples for rate schedules before and after the tax change. |

| 13. |

One small range of taxable income had a rate increase from 33% to 35%. For more details, see CRS Insight IN11039, The Federal Income Tax: How Did P.L. 115-97 Change Marginal Income Tax Rates?, by Margot L. Crandall-Hollick. |

| 14. |

See CRS Report R45092, The 2017 Tax Revision (P.L. 115-97): Comparison to 2017 Tax Law, coordinated by Molly F. Sherlock and Donald J. Marples. For a study that provides distributional effects adjusting for family size in ranking by income, see Arparna Mathur and Cody Kallen, "Estimating the Distributional Consequences of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act," presented at the fall meetings of the National Tax Association, 2018, https://ntanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Session1111_Paper1411_FullPaper_1.pdf. This adjustment causes more favorable treatment at the lower part of the distribution because families with children will be moved down in the distribution and these families benefitted from the child credit. Several equivalency indexes are used. |

| 15. |

These examples assume that all income is earned income and the taxpayer claims the standard deduction, applicable personal exemptions, the child credit and EITC (if eligible), and no other tax benefits. |

| 16. |

See CRS Report RL33755, Federal Income Tax Treatment of the Family, by Jane G. Gravelle. The calculations in this report are for 2016 and would change slightly due to inflation indexing for 2018. |

| 17. |

The equivalency formula used is (A+0.7K)0.7 based on Constance F. Citro and Robert T. Michael, Measuring Poverty: A New Approach (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1995). Using this formula, a single person would need 62% of the income of a married couple without children to achieve the same standard of income. A married couple with one child would need 23% more, and a married couple with two children would need 45% more. These numbers are similar to an alternative equivalency index measured as the square root of income. |

| 18. |

See Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income, Table 2.1, 2017, https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-individual-statistical-tables-by-size-of-adjusted-gross-income. |

| 19. |

See CRS Report RL33755, Federal Income Tax Treatment of the Family, by Jane G. Gravelle for rates under prior law. |

| 20. |

This is also reflected in estimates of the impact of the federal income tax code on poor families. Among families with workers and children, the income tax lifts many out of poverty, even after the 2017 tax revision. For more information, see CRS Report R45971, The Impact of the Federal Income Tax on Poverty: Before and After the 2017 Tax Revision ("TCJA"; P.L. 115-97), by Margot L. Crandall-Hollick, Gene Falk, and Jameson A. Carter. |

| 21. |

See James Alm and J. Sebastian Leguizamon, "Whither the Marriage Tax," National Tax Journal, vol.68, no. 2 (June 2015). For a review of earlier studies, see CRS Report RL33755, Federal Income Tax Treatment of the Family, by Jane G. Gravelle. |

| 22. |

For other discussions of this issue, see Alm and Leguizamon, "Whither the Marriage Tax"; Dennis Lassila, Murphy Smith, and Daqun Zhang, "Negative Social and Economic Effects of the Marriage Penalty Tax on Women and Society," Journal of Accounting and Finance, vol. 18, no. 5 (September 1, 2018), pp. 86-104; Emily Y. Lin and Patricia K. Tong, "Marriage and Taxes: What Can We Learn From Tax Returns Filed by Cohabitating Couples," National Tax Journal, vol. 65, no. 4 (December 2012), pp. 807-826. Earlier studies are referenced in CRS Report RL33755, Federal Income Tax Treatment of the Family, by Jane G. Gravelle. |

| 23. |

At $250,000 a small penalty appears where a small bonus previously existed, whereas the penalty at $500,000 is smaller than in prior law. Compare with data in CRS Report RL33755, Federal Income Tax Treatment of the Family, by Jane G. Gravelle. |

| 24. |

See U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Living Arrangements of Children, Table CH-1, November 2019, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/children.html. |

| 25. |

See Stacy Dickert-Conlin and Scott Houser, "Taxes and Transfers: A New Look at the Marriage Penalty," National Tax Journal, vol. 51, no. 2 (June 1998), pp. 175-217. |

| 26. |

See U.S. Census Bureau, Changes in Couples Living Together, November 19, 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2019/comm/changes-couples-living-together.html. See also Number of Unmarried Couples (opposite-sex), Figure UC-1, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/visualizations/time-series/demo/families-and-households/uc-1.pdf. |