Potential Effect of FCC Rules on State and Local Video Franchising Authorities

Local and state governments have traditionally played an important role in regulating cable television operators, within limits established by federal law. In a series of rulings since 2007, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has further limited the ability of local governments (known as local franchise authorities) to regulate and collect fees from cable television companies and traditional telephone companies (known as telcos) offering video services.

In August 2019, in response to a ruling by a federal court of appeals, the FCC tightened restrictions on municipalities’ and—for the first time—on states’ ability to regulate video service providers. The Communications Act of 1934, as amended, still allows local governments to require video service operators to provide public, educational, and government (PEG) channels to their subscribers. The FCC’s August 2019 order, however, sets new limits on local governments’ ability to collect fees from operators to support the channels. In addition, the FCC ruled that local franchise authorities could not regulate nonvideo services offered by incumbent cable operators, such as broadband internet service, business data services, and Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services. In October 2019, also for the first time, the FCC concluded that a video streaming service was providing “effective competition” to certain local cable systems, thereby preempting the affected municipalities’ ability to regulate local rates for basic cable service.

These rulings have caused controversy. The FCC has asserted that they fulfill a statutory mandate to promote private-sector investment in advanced telecommunications and information services and to limit government regulation when competition exists. State and local governments, however, have objected that the regulatory changes deprive them of revenue and make it harder for them to ensure that video providers meet local needs.

Against this backdrop of federal government actions limiting cable service regulation at the local level, consumer behavior continues to change. Specifically, an increasing number of consumers are substituting streaming services for video services provided by cable companies and telcos. As a result, the amount of revenue state and local governments receive from cable and telco providers subject to franchise fees is declining, which also reduces the amount cable providers can be required to spend to support PEG channels. In response, some municipalities and states have attempted to impose fees on online video services, such as Netflix and Hulu. Courts have not yet ruled on the legality of such fees.

These regulatory developments and industry trends raise several potential issues for Congress. First, Congress could consider whether the FCC’s interpretation of the Communications Act with respect to local regulation of video service providers is consistent with Congress’s policy goals. Specifically, Congress could explore the extent, if any, to which, if any, it encourages or permits state and local regulations designed to promote the availability of PEG programming as well as subsidized voice, data, and video services for municipal institutions.

Second, Congress could evaluate whether to create regulatory parity with respect to local regulation of cable and telcos’ nonvideo services. While states and municipalities may regulate both video and voice services of telcos, they may only regulate video services of cable operators. Congress could address regulatory parity by either deregulating traditional telcos’ nonvideo services or regulating cable operators’ nonvideo services.

Third, as the FCC and local governments include online video streaming services in their definitions of video providers for the purposes of evaluating competition and/or imposing franchise fees, Congress could clarify whether these actions achieve its stated policy goals. Finally, given the FCC’s actions to reduce local government rate regulation of cable services and the State of Maine’s legislation to enable video subscribers to seek alternatives to bundled programming, Members of Congress could reconsider past proposed statutory changes to require video programming distributors to offer individual channels to consumers. Alternatively, Congress could clarify that states and local governments lack authority to enact such laws.

Potential Effect of FCC Rules on State and Local Video Franchising Authorities

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview

- Regulation of Video Services

- Developments Prior to 1984

- Franchise Agreement Terms and Conditions

- Federal Regulatory Actions

- 1984 Cable Act

- Redefining Effective Competition

- 1992 Cable Act

- 1996 Telecommunications Act

- State vs. Local Franchising of Video Services

- State-Level Franchising Authority

- FCC Actions Affecting State and Local Video Service Franchising Terms and Conditions

- 2007 Order Addressing Local Franchising of New Entrants

- Franchise Fee Cap

- Treatment of Nonvideo Services by LFAs

- Additional Findings Regarding "Unreasonable" LFA Actions

- Court Ruling

- 2007 and 2015 Orders Addressing Local Franchising of Incumbent Cable Operators

- City and County LFAs Only

- Franchise Fee Cap

- Treatment of Nonvideo Services by LFAs

- Findings Applicable to New Entrants, but Not Incumbents

- Court Ruling

- 2019 FCC Rulemaking

- Potential Impact of FCC Rules

- Trade-Offs Between In-Kind Cable-Related Contributions and General Funds

- Evaluation of Provider Revenues Subject to Franchise Fee Cap

- Video-Related Revenues

- Nonvideo Revenues

- Outlook for State and Municipal Franchise Fees

- Preemption of Rate Regulation

- Considerations for Congress

Figures

Summary

Local and state governments have traditionally played an important role in regulating cable television operators, within limits established by federal law. In a series of rulings since 2007, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has further limited the ability of local governments (known as local franchise authorities) to regulate and collect fees from cable television companies and traditional telephone companies (known as telcos) offering video services.

In August 2019, in response to a ruling by a federal court of appeals, the FCC tightened restrictions on municipalities' and—for the first time—on states' ability to regulate video service providers. The Communications Act of 1934, as amended, still allows local governments to require video service operators to provide public, educational, and government (PEG) channels to their subscribers. The FCC's August 2019 order, however, sets new limits on local governments' ability to collect fees from operators to support the channels. In addition, the FCC ruled that local franchise authorities could not regulate nonvideo services offered by incumbent cable operators, such as broadband internet service, business data services, and Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services. In October 2019, also for the first time, the FCC concluded that a video streaming service was providing "effective competition" to certain local cable systems, thereby preempting the affected municipalities' ability to regulate local rates for basic cable service.

These rulings have caused controversy. The FCC has asserted that they fulfill a statutory mandate to promote private-sector investment in advanced telecommunications and information services and to limit government regulation when competition exists. State and local governments, however, have objected that the regulatory changes deprive them of revenue and make it harder for them to ensure that video providers meet local needs.

Against this backdrop of federal government actions limiting cable service regulation at the local level, consumer behavior continues to change. Specifically, an increasing number of consumers are substituting streaming services for video services provided by cable companies and telcos. As a result, the amount of revenue state and local governments receive from cable and telco providers subject to franchise fees is declining, which also reduces the amount cable providers can be required to spend to support PEG channels. In response, some municipalities and states have attempted to impose fees on online video services, such as Netflix and Hulu. Courts have not yet ruled on the legality of such fees.

These regulatory developments and industry trends raise several potential issues for Congress. First, Congress could consider whether the FCC's interpretation of the Communications Act with respect to local regulation of video service providers is consistent with Congress's policy goals. Specifically, Congress could explore the extent, if any, to which, if any, it encourages or permits state and local regulations designed to promote the availability of PEG programming as well as subsidized voice, data, and video services for municipal institutions.

Second, Congress could evaluate whether to create regulatory parity with respect to local regulation of cable and telcos' nonvideo services. While states and municipalities may regulate both video and voice services of telcos, they may only regulate video services of cable operators. Congress could address regulatory parity by either deregulating traditional telcos' nonvideo services or regulating cable operators' nonvideo services.

Third, as the FCC and local governments include online video streaming services in their definitions of video providers for the purposes of evaluating competition and/or imposing franchise fees, Congress could clarify whether these actions achieve its stated policy goals. Finally, given the FCC's actions to reduce local government rate regulation of cable services and the State of Maine's legislation to enable video subscribers to seek alternatives to bundled programming, Members of Congress could reconsider past proposed statutory changes to require video programming distributors to offer individual channels to consumers. Alternatively, Congress could clarify that states and local governments lack authority to enact such laws.

Overview

Local governments have traditionally played an important role in regulating cable television systems. Operators required municipal permission to place their cables above or beneath streets and other publicly owned land and to mount the cables on telephone/and or utility poles.1 Cities negotiated with cable operators over the services their systems would provide, including channels dedicated to public, educational, or government programming (PEG), and the payment of franchise fees. In exchange, the cable operators often received de facto exclusive local franchises to offer video distribution services. That changed in 1984, when Congress required local governments to allow competition.2 In the mid-2000s, as telephone companies (known as "telcos") sought to obtain their own video services franchises, state governments got involved to streamline the franchising process, in several instances preempting municipalities' authority. The states applied these laws to incumbent cable operators as well as to new entrants, to ensure legal parity.

As technological developments and changes in business strategies and consumer behavior have reshaped the telecommunications industry, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has taken several steps to limit local regulatory authority over cable and telco video service providers. Many of these regulatory changes have caused controversy. Some local governments assert that, among other things, the FCC's actions will limit their ability to protect the public interest and deprive them of revenue.3

This report examines the evolving relationship between federal, state, and local regulators and identifies related policy issues that may be of interest to Congress.

Regulation of Video Services

Cable television began operating in the 1940s as a means to receive broadcast signals in areas with trees or mountains that interfered with over-the-air signal transmission.4 Initially, municipalities, rather than states, made most decisions related to awarding cable franchises.5 As cable television developed, some states began to regulate the terms included in a cable franchise, or required state review or approval of a franchise agreement.6 The term local franchising authorities (LFAs) refers to municipal and/or state government entities that offer and negotiate video franchises. Today, agreements between LFAs and video service providers typically include provisions concerning the availability of channels for PEG programming;7 the amount of money due to the LFA in franchise fees, including in-kind contributions; and the rates charged to subscribers.

Developments Prior to 1984

The Communications Act of 1934 (referred to in this report as the Communications Act) created the FCC, but did not specifically set forth the FCC's authority to regulate cable.8 However, the U.S. Supreme Court found in 1968 that the agency's authority was sufficiently broad to do so.9 The FCC issued comprehensive regulations governing cable systems and cable franchising authorities in 1972.10 The FCC's rules directed cable operators to offer PEG services and LFAs to cap franchise fees.

Franchise Agreement Terms and Conditions

In the early days of cable television, a municipal government seeking to bring cable to its residents would, through a request for proposals, spell out the requirements that a cable operator would have to meet to win the franchise. Cable companies would bid against one another for the chance to wire the municipality. Renewal of an existing franchise might entail additional requirements.

PEGs

In 1972, the FCC directed cable operators to dedicate one channel for public access, one channel for educational use, and one channel for local government use by a certain date, and to add channel capacity if necessary to meet the requirement.11 Two years later, however, the commission reconsidered its stance, stating,

Demands are being made not only for excessive amounts of free equipment but also free programming and engineering personnel to man the equipment. Cable subscribers are being asked to subsidize the local school system, government, and access groups. This was not our intent and may, in fact, hamper our efforts at fostering cable technology on a nationwide scale. Too often these extra equipment and personnel demands become franchise bargaining chips rather than serious community access efforts. We are very hopeful that our access experiment will work.... We do not think, however, that simply putting more demands on the cable operator will make public access a success. Access will only work, we suspect, when the rest of the community assumes its responsibility to use the opportunity it has been provided.12

Although the U.S. Supreme Court later struck down the FCC's rules requiring cable operators to set aside channels for PEGs,13 PEG access requirements became commonplace in local franchise agreements by the early 1980s.14 Congress encouraged this development. According to a 1984 report from the House Committee on Energy and Commerce

Public access channels are often the video equivalent of the speaker's soapbox or the electronic parallel to the printed leaflet. They provide groups and individuals who generally have not had access to the electronic media with the opportunity to become sources of information in the electronic marketplace of ideas. PEG channels also contribute to an informed citizenry by bringing local schools into the home, and by showing the public local government at work.15

Franchise Fees

In addition to requiring cable system owners to obtain a franchise before operating, municipalities also required cable system owners to pay a franchise fee. In its 1972 Cable Order, the FCC stated,

[M]any local authorities appear to have extracted high franchise fees more for revenue-raising than for regulatory purposes. Most fees are about five or six percent, but some have been known to run as high as 36 percent. The ultimate effect of any revenue-raising fee is to levy an indirect and regressive tax on cable subscribers. Second, and of great importance to the Commission, high local franchise fees may burden cable television to the extent that it will be unable to carry out its part in our national communications policy.... We are seeking to strike a balance that permits the achievement of federal goals and at the same time allows adequate revenues to defray the costs of local regulation.16

To accomplish this balance, the FCC capped the franchise fees at 3%-5% of a cable operator's revenues from subscribers. For fees greater than 3% of an operator's subscriber revenues, the FCC required a franchising authority to submit a showing that the specified fee was "appropriate in light of the planned local regulatory program."17

Rates Charged to Subscribers

When cable television first developed as essentially an antenna service to improve over-the-air broadcast television signal reception in rural and suburban areas, many municipalities regulated the rates charged to subscribers.18 The municipalities viewed rate regulation, tied to the systems' use of public streets, as a means of preventing cable operators from charging unreasonably high rates for what they viewed as an essential service.

In the 1972 Cable Order, the FCC required franchising authorities to specify or approve initial rates for cable television services regularly furnished to all subscribers and to institute a program for the review and, as necessary, adjustment of rates.19 In 1976, the FCC repealed those rules and instead made LFA regulation of rates for cable television services optional.20 In 1974, the FCC preempted LFAs from regulating rates for other so-called "specialized services," including "advertising, pay services, digital services, [and] alarm systems."21

Federal Regulatory Actions

1984 Cable Act

In the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 (P.L. 98-549, referred to in this report as the 1984 Cable Act), Congress added Title VI to the Communications Act to give the FCC explicit authority to regulate cable television. The 1984 Cable Act established the local franchising process as the primary means of cable television regulation.22 The act did not diminish state and local authority to regulate matters of public health, safety, and welfare; system construction; and consumer protection for cable subscribers.23

Congress enacted the 1984 Cable Act the same year that American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T), which had an effective monopoly over most telecommunications services, spun off its regional operating companies as part of the settlement of a federal antitrust suit.24 The 1984 Cable Act generally prohibited telcos from providing video services in the same regions where they provided voice services.25 This prohibition prevented the former AT&T companies from competing with cable operators in communities where they controlled the local telephone system.

Franchise Fees and PEGs

The 1984 Cable Act confirmed the power of state and municipal governments to include requirements for PEGs, facilities and equipment, and certain aspects of program content within franchise agreements. It delineated federal limits on franchise fees, and restricted the FCC's power to regulate the amount of franchise fees or the use of funds derived from those fees.

The law permits franchising authorities to charge franchise fees, but limits such fees to no more than 5% of the cable operators' gross revenues from "cable services."26 For the purposes of calculating gross revenues, the FCC included revenues from advertising and home shopping commissions, in addition to revenues from video service subscriptions.27 Subsequently, as described in "FCC Actions Affecting State and Local Video Service Franchising Terms and Conditions," defining the costs that are subject to the 5% statutory limit on franchise fees became a point of repeated controversy.

The 1984 Cable Act allows local franchising authorities to enforce any PEG access requirements in a franchise agreement.28 Such terms and conditions can include providing video production facilities and equipment, paying capital costs related to PEG facilities beyond the 5% franchise fee cap, and paying costs associated with support of PEG channel use.29 In addition, the 1984 Cable Act permitted LFAs to require cable operators to designate channels for PEGs on institutional networks (I-Nets) provided for public buildings and other nonresidential subscribers.30

Rate Regulation

Section 623 of the 1984 Cable Act (47 U.S.C. §543) prohibits federal, state, or local franchising authorities from regulating the rates of cable operators that are "subject to effective competition," as defined by the FCC. The 1984 Cable Act directs the FCC to review its standards for determining effective competition periodically, taking into account developments in technology.

Redefining Effective Competition

In 1985, the FCC determined that cable systems generally were subject to "effective competition" if they operated in an areas where three or more broadcast television signals were either "significantly viewed" by residents or transmitted with acceptable signal quality (as defined by the FCC) to the cable systems' franchise areas.31 In accordance with the timetable set by the 1984 Cable Act, the "effective competition" rule became effective on December 29, 1986. This rule effectively deregulated cable prices in most communities.

In 1991, the FCC adopted a new definition of "effective competition." The FCC deemed effective competition to exist if either:

- 1. six unduplicated broadcast signals were available to the cable operator's franchise area via over-the-air reception, or

- 2. another multichannel video service, such as a satellite service, was available to at least 50% of homes to which cable services were available (homes passed), and was subscribed to by 10% of the cable operator's homes passed.32

Under this more restrictive definition, most systems were still subject to effective competition and therefore not subject to rate regulation.33

1992 Cable Act

In the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-385, referred to here as the 1992 Cable Act), Congress stated the policy goal of relying on market forces, to the maximum extent feasible, to promote the availability of a diversity of views and information through cable television and other video distribution media. Congress emphasized the importance of protecting consumer interests where cable systems are not subject to effective competition, and of ensuring that cable operators do not have undue market power vis-à-vis video programmers and consumers.34

New Entrants in Video Programming Distribution Markets

The 1992 Cable Act revised Section 621(a)(1)35 of the Communications Act36 to codify restraints on local franchise authorities' licensing activities. While local authorities retained the power to grant cable franchises, the law provided that "a franchising authority may not grant an exclusive franchise and may not unreasonably refuse to award an additional competitive franchise."37 Congress gave potential entrants a judicial remedy by enabling them to commence an action in a federal or state court within 120 days after a local authority refused to grant them a franchise.38

Rate Regulation

In addition, Congress made it easier for local authorities to regulate cable rates by adopting a more restrictive definition of "effective competition" than the FCC's.39 Pursuant to these changes, local authorities may not regulate cable rates if at least one of the following four conditions is met:

- 1. fewer than 30% of the households in the franchise area subscribe to a particular cable service;

- 2. within the franchise area,

a. at least two unaffiliated multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs)40 each offer comparable video programming to at least 50% of the households in the franchise area, and

b. at least 15% of households subscribe to an MVPD other than the largest one; - 3. an MVPD owned by the franchising authority offers video programming to at least 50% of the households in the franchise area; or

- 4. a telephone company offering local voice services (known as a "local exchange carrier" [LEC])41 or its affiliate, "(or any multichannel video programming distributor using the facility of such carrier or its affiliate)" carries comparable video programming services directly to subscribers by any means (other than direct-to-home satellite services) in the franchise area of an unaffiliated cable operator that is providing video service in that franchise area.42

Congress directed the FCC to publish a survey of cable rates annually.43

1996 Telecommunications Act

Even as the 1992 Cable Act took effect, a combination of technological, economic, and legal factors was enabling the convergence of the previously separate telephone, cable, and satellite broadcasting industries. Digital technology, particularly the ability to compress digital signals, enabled both direct broadcast satellite (DBS) services and cable operators to offer dozens of channels.44 In 1993, the telephone company Bell Atlantic successfully challenged, on First Amendment grounds, the 1984 ban on cross-ownership of telephone and cable companies in the same local market.45 In the meantime, several cable operators sought to gain economies of scale by consolidating local systems into regional systems.46

In the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-104), Congress permitted LECs to offer video services and cable operators to offer voice services.47 Because laws and regulations pertaining to cable systems were quite different from those pertaining to LECs, the prospect of greater competition between those two types of providers led Congress to revisit video market regulation. Moreover, Section 601 rescinded the 1982 consent decree that required the breakup of AT&T, thereby allowing LECs to consolidate further by subsequently merging with long-distance service providers and each other.48

The act stipulated that cable operators do not need to obtain approval of local authorities that regulate their video services in order to offer "telecommunications services," such as voice services.49 The Senate Commerce Committee noted that these changes did not affect existing federal or state authority with respect to telecommunications services.50 It stated that the committee intended that local governments, when exercising their authority to manage their public rights of way, regulate telecommunications services provided by cable companies in a nondiscriminatory and competitively neutral manner.51

Congress used the term "open video systems" (OVS) in the 1996 Telecommunications Act (§653) to describe LECs that soughtto compete with cable operators.52 The act explicitly exempted OVS service from franchise fees and other 1992 Cable Act requirements, including the requirement to obtain a local franchise. In 1999, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit interpreted the provision to mean that, while the federal government could no longer require OVS operators to obtain a local franchise, state and local authorities could nevertheless do so.53

State vs. Local Franchising of Video Services

In 2003, several telephone companies, most notably Southwestern Bell Company (now AT&T) and Verizon, began constructing fiber networks designed to bring consumers advanced digital services, including video.54 AT&T and Verizon branded these services as "U-Verse" and "FiOS," respectively. Neither company launched video services under the OVS rules, claiming that federal requirements and potential local franchise requirements were too costly.55

In 2006, a federal district court in California dismissed AT&T's claims that municipalities were violating federal law by attempting to exercise franchise authority over the company's video services.56 The court declined, however, to rule on whether video delivered over internet protocol, the technology used by LECs, met the federal definition of a cable service.57 Two bills introduced that year in the 109th Congress, H.R. 5252 and S. 2686, would have declared that video service enabled via internet protocol is subject only to federal regulation. Congress did not vote on either bill.

State-Level Franchising Authority

As the LECs sought to enter the video distribution market, they pursued statewide reforms to speed their entry, rather than seeking franchises in individual municipalities.58 The LECs' competitors, the incumbent cable operators, contended that state-level franchising would present new entrants with fewer obligations than cable companies had faced when they entered the market, specifically the obligation to build networks serving all parts of a community.59

In 2005, Texas became the first of several states to replace local franchising with a state-level regime for video service providers, with the express purpose of facilitating entry by new competitors.60 As Table 1 illustrates, many other states have since either replaced municipal franchising with state-level franchising or offered providers a choice.

|

Full State Control |

Operator Option for State Franchise |

Limited State Franchising |

State Oversight of Municipal Franchises |

State Support of Municipal Franchises |

State Specifies Terms and Conditions; No Agency to Enforce |

Municipal Franchising Only; No State Oversight |

||

|

Alaska |

Arizona |

Delaware |

Massachusetts |

Maine |

Alabama |

Colorado |

||

|

California |

Arkansas |

Louisiana |

Michigan |

New Hampshire |

Kentucky |

Maryland |

||

|

Connecticut |

Georgia |

Nevada |

New York |

Minnesota |

Mississippi |

|||

|

Florida |

Idaho |

West Virginia |

Oklahoma |

Montana |

||||

|

Hawaii |

Illinois |

Pennsylvania |

Nebraska |

|||||

|

Indiana |

Iowa |

Virginia |

New Mexico |

|||||

|

Kansas |

New Jersey |

North Dakota |

||||||

|

Missouri |

Tennessee |

Oregon |

||||||

|

North Carolina |

South Dakota |

|||||||

|

Ohio |

Utah |

|||||||

|

Rhode Island |

Washington |

|||||||

|

South Carolina |

Wyoming |

|||||||

|

Texas |

||||||||

|

Vermont |

||||||||

|

Wisconsin |

||||||||

Source: CRS analysis of state statutes. See also, Telecommunications and Cable Regulation, v. 1,"13.05(2): State Franchising Structures; State Regulatory Schemes" (updated through 2011); National Conference of State Legislatures, "Statewide Video Franchising Statutes," May 31, 2019, http://www.ncsl.org/research/telecommunications-and-information-technology/statewide-video-franchising-statutes.aspx, and Federal Communications Commission, "EDOCS: Commission Documents, 'Enforcing Laws Governing Cable Franchising,'" July 11, 2019, n. 426.

Notes: The District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands have designated agencies to issue video franchises. Statutes from the Northern Mariana Islands were not available in Lexis.

FCC Actions Affecting State and Local Video Service Franchising Terms and Conditions

Since 2007, the FCC has repeatedly revisited the authority of states and LFAs to franchise and regulate video service providers.61 This process culminated in two orders issued in 2019. One (the "2019 LFA 3rd R&O") sharply limits state and local authority over products offered by video service providers other than video programming. The other order (the "2019 Effective Competition Order") determined that AT&T's streaming service, AT&T TV NOW, meets the LEC test component of Congress's effective local competition definition and therefore provides effective competition to a local cable operator.

2007 Order Addressing Local Franchising of New Entrants

In 2007, the FCC found that the local franchising process constituted an unreasonable barrier to new entrants in the marketplace for video services and to their deployment of high-speed internet service.62 The FCC adopted rules and guidance covering cities and counties that grant cable franchises. However, the agency stated that it lacked sufficient information regarding whether to apply the rules and guidance to state governments that either issued franchises at the statewide level or had enacted laws governing specific aspects of the franchising process.63 Consequently, the FCC stated that while it would preempt local laws, it would not preempt state laws covering video franchises.64

Franchise Fee Cap

In-Kind Contributions Unrelated to Cable Services Included in Cap

The FCC determined that unless certain specified costs, fees, and other compensation required by LFAs are counted toward the statutory 5% cap on franchise fees, an LFA's demand for such fees represents an unreasonable refusal to award a competitive franchise to a new entrant. In addition, the FCC found that some LFAs had required new entrants to make "in-kind" payments or contributions that are unrelated to the provision of cable services.65 The FCC stated that any requests by LFAs for in-kind contributions that are unrelated to the provision of cable services by a new competitive entrant are subject to the statutory 5% franchise fee cap.

Payments Made to Support PEG Operations Included in Cap

The FCC contended that disputes between LFAs and new entrants over LFA-mandated contributions in support of PEG services and equipment could lead to unreasonable refusals by LFAs to award competitive franchises.66 It determined that costs related to supporting the use of PEG access facilities, including but not limited to salaries and training, are subject to the 5% cap,67 but that capital costs "incurred in or associated with the construction of PEG access facilities" are excluded from the cap.68

Treatment of Nonvideo Services by LFAs

The FCC stated that the LFAs' jurisdiction over LECs and other new entrants applies only to the provision of video services.69 Specifically, it stated that an LFA cannot use its video franchising authority to attempt to regulate a LEC's entire network beyond the provision of video services.70

Additional Findings Regarding "Unreasonable" LFA Actions

In addition, the FCC found that the following LFA actions constitute an unreasonable refusal to award video franchises to new entrants:

- 1. failure to issue a decision on a competitive application within the time frames specified in the FCC's order;71

- 2. refusal to grant a competitive franchise because of an applicant's unwillingness to agree to "unreasonable" build-out requirements;72 and

- 3. denying an application based upon a new entrant's refusal to undertake certain obligations relating to PEGs and I-Nets.73

Court Ruling

In 2008, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit upheld the FCC's rules.74

2007 and 2015 Orders Addressing Local Franchising of Incumbent Cable Operators

In November 2007, the FCC issued a Second Report and Order that extended the application of several of these rules to local procedures to renew incumbent cable operators' franchises.75 Specifically, the FCC determined that the rules addressing LFAs' franchise fees, PEG and institutional network obligations, and non-cable-related services and facilities should apply to incumbent operators. It concluded, however, that FCC rules setting time limits on LFAs' franchising decisions and limiting LFA build-out requirements should not apply to incumbent cable operators.

Several LFAs petitioned the FCC to reconsider and clarify its Second Report and Order. In 2015, the FCC issued an Order on Reconsideration in which it set forth additional details about its rules76 with the stated purposes of promoting competition in video services and accelerating broadband deployment. Following the 2015 Order on Reconsideration, the following policies were in place.

City and County LFAs Only

The FCC clarified that its rules and regulations on franchising applied to city and county LFAs only, not to state-level laws or decisions.77 The FCC stated that it lacked sufficient information about the state-level franchising process, and suggested that if parties wished the agency to revisit this issue in the future, they should provide evidence that doing so would achieve Congress's policy goals.

Franchise Fee Cap

In-Kind Contributions Unrelated to Cable Services Included in Cap

The FCC included in-kind contributions from incumbent cable operators that were unrelated to the provision of video services within the statutory 5% franchise fee cap.78 Likewise, the FCC found that payments made by cable operators to support PEG access facilities are subject to the 5% cap, unless they fall under the FCC's definition of "capital costs" associated with the construction of PEG facilities.79 The FCC made in-kind contributions related to cable services subject to the cap on franchise fees for new entrants as well as for cable incumbents.80

Treatment of Nonvideo Services by LFAs

The FCC determined that LFAs' jurisdiction to regulate incumbent cable operators' services is limited to video services, and does not include voice or data services.81

Findings Applicable to New Entrants, but Not Incumbents

In addition, the FCC found the following LFA actions do not per se constitute an unreasonable refusal to award video franchises to cable incumbents, although they did for new entrants:

- 1. denying an application based upon an incumbent's refusal to undertake certain obligations relating to PEGs and institutional networks;82

- 2. failure to issue a decision on a competitive application within the time frames specified in the FCC's order;83 and

- 3. refusal to grant a competitive franchise because of an applicant's unwillingness to agree to unreasonable build-out requirements.84

Court Ruling

In 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit addressed challenges by LFAs to the 2007 Second Report and Order and the 2015 Order on Reconsideration.85 The court found that the FCC had made sufficiently clear that its rules only apply to city and county LFAs and did not bind state franchising authorities.86

It determined that the FCC had correctly concluded that noncash contributions could be included in its interpretation of "franchise fee" subject to the 5% limit.87 However, the court held that the FCC had neither explained why the statutory text allowed inclusion of in-kind cable-related contributions within the 5% cap nor defined what "in-kind" meant.88 It found that the FCC offered no basis for barring local franchising authorities from regulating the provision of "non-telecommunications" services by incumbent cable providers.89 It directed the FCC to set forth a valid statutory basis, "if there is one," for applying its rule to the franchising of cable incumbents. The court used the term "non-telecommunications" service rather than "non-video" or "non-cable" service, differing from the distinctions the FCC made with respect to LFAs' authority.90

2019 FCC Rulemaking

The FCC responded to the court's directives in 2018, and once again proposed rules governing the franchising of cable incumbents.91 On August 1, 2019, the FCC adopted its Third Report and Order (R&O).92 The FCC stated that its rules would ensure a more level playing field between new entrants and incumbent cable operators93 and accelerate deployment of "advanced telecommunications capability" by preempting local regulations that "impose an undue economic burden" on video service providers.94

The FCC stated that the franchise fees rulings are prospective. That is, video operators may count only ongoing and future in-kind contributions toward the 5% franchise fee cap after September 26, 2019, the effective date of its rules.95 To the extent franchise agreements conflict with the FCC's rules, the agency encourages the parties to negotiate franchise modifications within a "reasonable timeframe," which it states should be120 days in most cases.96 Under the new regulations:

- The FCC oversees state franchising authorities for the first time.97

- Cable-related in-kind contributions from both new entrants and incumbent cable operators are "franchise fees" subject to the 5% cap, with limited exceptions.98 Such contributions include any nonmonetary contributions related to the provision of video services by incumbent cable operators and LECs as a condition or requirement of a local franchise agreement. Examples include free and discounted cable video service to public buildings; costs in support of PEG access facilities other than capital costs; and costs associated with the construction, maintenance, and service of an I-Net.99 For purposes of calculating contributions toward the 5% franchise fee cap, video providers and LFAs must attach a fair market value to cable-related in-kind contributions,100 but the FCC declined to provide guidance on how to calculate fair market value.101

- The definition of PEG "capital costs" subject to the 5% cap includes equipment purchases and construction costs,102 but does not include the cost of installing the facilities that LFAs use to deliver PEG services from locations where the programming is produced to the cable headend.103

- Requirements that cable operators build out their systems within the franchise area and the cost of providing channel capacity for PEG channels may not be included under the 5% cap.

- Franchise authorities may not regulate nonvideo services offered over cable systems by incumbent cable operators. The services covered by this prohibition include broadband internet service, business data services, and Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services.104

- "[S]tates, localities, and cable franchising authorities are preempted from charging franchised cable operators more than five percent of their gross revenue from cable [video] services."105 Thus, LFAs may not include nonvideo service revenues when calculating the 5% cap.

The communities of Los Angeles, CA, Portland, OR, and Eugene, OR, have filed a petition with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit challenging the FCC's rules.106 The Ninth Circuit has consolidated the various appellate court challenges, and in November 2019, granted an FCC motion to transfer the now-consolidated petition to the U.S. Court of Appeals, Sixth Circuit.107

Potential Impact of FCC Rules

Table 1, as well as the following two tables, illustrate how the FCC's rules could potentially affect the franchising process in several states. The FCC's decision to extend its franchising rule to state governments for the first time will subject each of the states listed in the first three columns of Table 1 (i.e., those that issue franchises at the state-level in all or some circumstances) to the FCC's rules. Moreover, the FCC's rules will cover states that oversee municipal franchises via either statute or state-level agencies. Thus, the FCC's franchising rules will affect more video service providers, viewers, and municipal governments than ever before.

Trade-Offs Between In-Kind Cable-Related Contributions and General Funds

Because the FCC is including cable-related in-kind contributions in its definition of franchise fees subject to the 5% cap, some states and municipalities may need to make a trade-off.

Specifically, as Table 2 illustrates, several states require or allow LFAs to require video service providers to offer free and/or discounted video service to public buildings, support of PEG services (other than capital costs), and support of I-Nets. Affected states and municipalities may need to reevaluate the trade-off between in-kind cable-related contributions and general fund revenues. Note that Ohio and Wisconsin prohibit both PEG and I-Net contribution requirements, while Idaho prohibits I-Net contribution requirements.

Table 2. Cable-Related In-Kind Contribution Requirements/Prohibitions

Terms and Conditions of Franchising Agreements (Where States Regulate by Statute)

|

Free/ Discounted Video Services to Public Buildings Required |

Support of PEG Facilities (Other Than Capital Costs) Required |

Support of PEG Facilities if Existing Municipal Franchise Agreement Requires |

Prohibition of Required PEG Support |

I-Net Support Required |

I-Net Support Required in Limited Cases |

Prohibition of I-Net Support Require-ments |

|

Connecticut |

Arizona |

Indiana |

Ohio |

New Jersey |

Rhode Island |

Idaho |

|

Delaware |

California |

Iowa |

Wisconsin |

Tennessee |

Iowa |

Ohio |

|

Florida |

Rhode Island |

Michigan |

Texas |

Wisconsin |

||

|

Illinois |

Tennessee |

District of Columbia |

||||

|

New Jersey |

||||||

|

North Carolina |

||||||

|

Texas |

||||||

|

District of Columbia |

Source: CRS analysis of state statutes.

Notes: In Nevada, incumbent cable operators may cease to provide free or discounted cable services (or other services) 12 months after obtaining a franchise from the secretary of state. The term "PEG" stands for "public, educational, and government channels." The term "I-Net" stands for "Institutional Network."

Evaluation of Provider Revenues Subject to Franchise Fee Cap

Video-Related Revenues

As Table 3 illustrates, some states define "gross revenues" more narrowly than the FCC, excluding, for example, revenues from advertising and home shopping commissions. In those states, as well as others in which municipal LFAs define gross revenues more narrowly than the FCC, PEGs may be able to continue to receive cable-related, in-kind contributions without reducing the monetary contributions they receive, while remaining within the 5% cap. As described in "Franchise Fees and PEGs," the FCC has included revenues from advertising and home shopping commissions, in addition to revenues from video service subscriptions, in its definition of "gross revenues." LFAs that use similar definitions of "gross revenues," including those subject to state regulation, may already charge the maximum amount of franchise fees permitted by the FCC. Others, however, exclude these sources, and may therefore have more flexibility when evaluating whether or not to continue their cable-related in-kind contributions.

|

Video Revenues, Excluding Advertising and Home Shopping Commissions |

Video Revenues, Including Advertising and Home Shopping Commissions |

Video Revenues, Including Advertising, but Not Home Shopping |

Excludes Revenues from Non-Video Services |

Excludes Other Revenues |

Includes Other Revenues |

|

Arizona |

Arkansas |

Iowa |

Arkansas |

California |

New York |

|

Delaware |

District of Columbia |

Ohio |

California |

Indiana |

Tennessee |

|

Idaho |

Georgia |

Delaware |

Missouri |

Texas |

|

|

Indiana |

Illinois |

Illinois |

New Jersey |

||

|

Nevada |

Kansas |

Indiana |

New York |

||

|

New Jersey |

Louisiana |

Iowa |

Ohio |

||

|

Pennsylvania |

Michigan |

Kansas |

Pennsylvania |

||

|

Missouri |

Missouri |

South Carolina |

|||

|

New York |

Nebraska |

Tennessee |

|||

|

South Carolina |

New Jersey |

Texas |

|||

|

Tennessee |

Ohio |

Virginia |

|||

|

Texas |

Pennsylvania |

Wisconsin |

|||

|

Virginia |

South Carolina |

||||

|

Wisconsin |

Tennessee |

||||

|

Texas |

|||||

|

Wisconsin |

Source: State statutes.

Notes: Some states may define "gross revenues" in agencies' administrative codes. Table excludes states without statutes covering video service providers. Some states exclude some types of nonvideo revenues while including others. New York, for example, excludes taxes on services furnished by provider imposed directly on any subscriber or user by any municipality, state, or other governmental unit and collected by the company for such governmental unit, in its calculation of gross revenues subject to franchise fees. Tennessee, in contrast excludes revenues from voice and data services but permits municipalities to include franchise fees in gross revenue calculations under limited circumstances.

Moreover, some states specifically exclude other items when calculating providers' revenue bases that are subject to the franchise fees. Several exclude government fees and/or taxes passed on to subscribers, while Missouri excludes fees and contributions for I-Nets and PEG support from its calculation. The FCC has not specifically addressed whether franchise authorities may include these items in their revenue base calculation. Thus, these states may also have more flexibility when evaluating whether to change video franchises' terms and conditions.

Nonvideo Revenues

Many states already exclude nonvideo revenues from the calculation of provider revenues subject to the franchise fee cap. New York, however, describes the gross revenues of a video provider subject to the franchising fees as including, among other things, "carrier service revenue."108 This section of the New York statute does not define "carrier service revenue." A current dispute between New York City and Charter Communications (d/b/a Spectrum) for service within Brooklyn concerns whether "carrier service revenue" received from "additional provided services" may be subject to franchise fees.109 The FCC's new rules may affect the outcome of this dispute.

Moreover, in July 2019, the New York State Public Service Commission approved a settlement of a complaint that Charter has failed to comply with a requirement in its franchise agreement to expand high-speed service. Under the settlement, Charter may continue operating within the state, if it expands its high-speed internet service infrastructure to 145,000 residents in Upstate New York and invests $12 million in providing high-speed internet services to other areas of the state.110 If Charter contends that the FCC's rules preempt these provisions, it could seek to renegotiate the settlement.

The FCC cited a decision by the Supreme Court of Oregon in City of Eugene v. Comcast as an example of states and localities asserting authority to impose fees and requirements beyond their authority.111 In the decision, the court upheld a local government's 7% license fee on revenue from broadband services provided over a franchised cable system. Thus, while states and municipalities may regulate both video and voice services of telcos, they may only regulate video services of cable operators.

Outlook for State and Municipal Franchise Fees

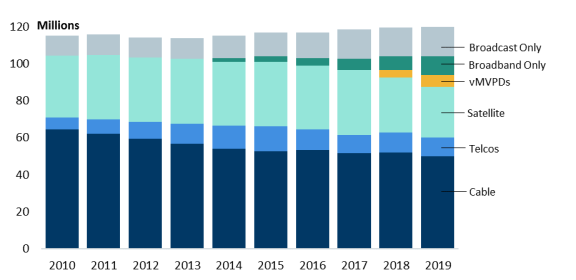

If a state or municipality may charge franchise fees to cable operators and telcos only with respect to video services, the total amount of fees received is likely to decrease over time. As Figure 1 indicates, the total number of U.S. households subscribing to cable and telco video services has declined over the past 10 years. In 2010, about 70.8 million households subscribed to either a cable operator or a telco, compared with about 60.1 million households in 2019. In place of cable, more households have elected to rely on video provided over broadband connections or broadcast transmission.

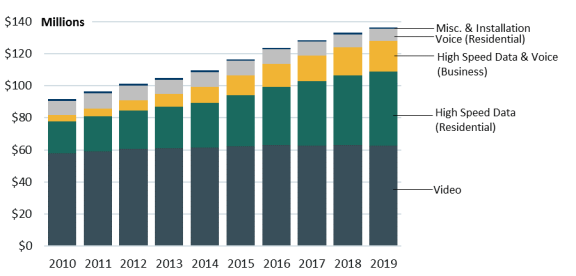

For cable operators in particular, this substitution of alternative sources of programming has led to the pursuit of revenue from nonvideo services, such as voice and high-speed data. In 2010, video services represented about 63% of total cable industry revenue, whereas in 2019 video represented 46% of total industry revenue (Figure 2). Pursuant to the FCC's proposed rules, these other sources of revenue are not subject to LFAs' jurisdiction. In addition, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit held that a cable operator's voice services are not a telecommunications service, and therefore not subject to state regulation.112 In October 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court denied the Minnesota Public Utility Commission's petition hear the case.113

In Missouri, the City of Creve Coeur and other municipalities filed a class action lawsuit against satellite operators DIRECTV, DISH Network, as well as online streaming services Netflix Inc., and Hulu LLC, claiming that the companies must pay a percentage of gross receipts from video services to the municipalities where they do business, pursuant to Missouri's Video Services Providers Act.114 The state law allows Missouri's political subdivisions to collect up to 5% of gross receipts from providers of video programming and requires providers to register before providing service in the state, according to court documents. The municipalities claim the defendants have not paid the required amounts.

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from S&P Global. |

Other localities may follow suit. A bill before the Illinois General Assembly would impose a 5% tax (rather than a "franchise fee") on the video service revenues of direct broadcast satellite operators and online video services for the right to provide services to Illinois residents.115 Similarly, a bill before the Massachusetts House of Representatives116 would impose a 5% fee on revenues earned by streaming video services. Massachusetts would split the money collected from the fees between the state's general fund (20%), municipalities (40%), and PEG programmers (40%).117 If receipts from cable franchise fees continue to erode, more states and municipalities may respond by seeking alternative revenue sources.

Preemption of Rate Regulation

In 2014, Congress enacted the Satellite Television Extension and Localism Act Reauthorization Act (STELA Reauthorization Act; P.L. 113-200). Section 111 of the act directed the FCC to develop a streamlined process for the filing of "effective competition" petitions by small cable operators within 180 days of the law's enactment.118 A cable company filing such a petition bears the burden of proof to demonstrate that it faces effective competition for its video services.

The FCC responded in 2015 by adopting a rebuttable presumption that cable operators are subject to effective competition.119 As a result, the FCC prohibited franchising authorities from regulating basic cable rates unless they can demonstrate that the cable system is not subject to effective competition. The FCC stated that the change in its effective competition definition was justified by the fact that direct broadcast satellite service was available as an alternative video services provider throughout the United States.120

Later in 2015, the FCC found that LFAs in two states, Massachusetts and Hawaii, demonstrated that cable systems in their geographic areas were not subject to effective competition, and permitted them to continue to regulate the rates of the basic tiers of cable services.121 However, in September 2018, Charter Communications (Charter), a cable provider, asked the FCC to find that AT&T's DIRECTV NOW, a streaming service that AT&T has since rebranded as AT&T TV NOW, provides effective competition to cable systems in Kauai, HI, and 32 Massachusetts communities.122 In October 2019, the FCC agreed and issued an order granting Charter's petition, finding for the first time that an online streaming service affiliated with a LEC meets the LEC test in Congress's definition of effective competition.123

The FCC found that

[AT&T TV NOW] need not itself be a LEC and AT&T need not offer telephone exchange service in the franchise areas.... There is no requirement ... that a LEC provide telephone exchange service in the same communities as the competing video programming service.124

Thus, if even AT&T TV NOW's subscribers rely on internet service from Charter to receive AT&T TV NOW's programming, the FCC considers AT&T TV NOW to be a competitor to Charter with respect to the distribution of video programming. According to the FCC,

Congress adopted the LEC test because LECs and their affiliates "are uniquely well-funded and well-established entities that would provide durable competition to cable," and not because [Congress was] focused on facilities-based competition.125

Meanwhile, some localities have enacted legislation with the goal of reducing prices consumers pay for video services. A 2019 Maine law would require video service providers to offer networks and programs on an a la carte basis instead of offering subscribers only bundles of channels.126 Several cable operators, broadcasters, and content providers have sued to overturn the law. In January 2020, a federal judge blocked the implementation of the law as the parties prepare for trial.127

Considerations for Congress

These regulatory developments and industry trends raise several potential issues for Congress to consider.

First, Congress could consider whether the FCC's interpretation of the Communications Act is consistent with the policy goals set forth in Section 601 of the Communications Act (47 U.S.C. §521) and Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act. Specifically, Congress could explore the extent, if any, to which state and local regulations designed to promote the availability of PEG programming and I-Nets.

Second, Congress could evaluate whether to create regulatory parity with respect to local regulation of nonvideo services of cable and telcos. While states and municipalities may regulate both video and voice services of telcos, they may only regulate video services of cable operators. Congress could address regulatory parity by either deregulating traditional telcos' nonvideo services or regulating cable operators' nonvideo services.

Third, as the FCC and local governments include online video providers in their definitions of video providers for the purposes of evaluating competition and/or imposing franchise fees, Congress could clarify whether these actions achieve its stated policy goals. For example, if, in contrast to the FCC's interpretation of the LEC test for effective competition, Congress intends to include only facilities-based video services in its definition of video service competition, it could delineate the definition in communications laws. Likewise, as online video services become more prevalent and states and municipalities target them for franchise fees, Congress could specify the authority, if any, to regulate them.

Finally, while the FCC has determined that competition among video programming distribution services has eliminated the need for rate regulation of the basic tier of cable services, Maine enacted a law to enable consumers to pay only for video programming they choose, in lieu of bundles of channels. In the past, some Members of Congress have proposed statutory changes to require video programming distributors to offer individual channels to consumers in addition to bundles of channels, and Congress could consider revisiting this issue, or alternatively clarifying that states and local governments lack authority to enact such laws.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Patrick Parsons, Blue Skies: A History of Cable Television (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008), p. 289 (Parsons). |

| 2. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, Cable Television Consumer Protection Act of 1991, report on S. 12, 102nd Cong., 1st sess., June 28, 2008, S. Rept. 102-92 (Washington: GPO, 2008), p. 24. |

| 3. |

National League of Cities; United States Conference of Mayors; National Association of Regional Councils; National Association of Towns and Townships; National Association of Telecommunications Officers and Advisors, "Motion for Stay, in the Matter of Implementation of Section 621(a) of the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 as Amended By the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992, MB 05-311, before the Federal Communications Commission, October 7, 2017, https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/filings?proceedings_name=05-311&sort=date_disseminated,DESC. |

| 4. |

Michael O'Connor, "Mediated," in Ted Turner: a Biography (Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 2010), p. 49. |

| 5. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Cable Franchise Policy and Communications Act of 1984, report to accompany H.R. 4103, 98th Cong., 2nd sess., August 1, 1984, H. Rept. 98-934 (Washington: GPO, 1984), p. 23 (1984 House Energy and Commerce Committee Report). |

| 6. |

Ibid., pp. 19, 30. See also Stephen R. Barnett, "State, Federal, and Local Regulation of Cable Television," Notre Dame Law Review, vol. 47, no. 4 (April 1, 1972), pp. 680, 690. |

| 7. |

Public access channels are available for use by the general public. They are usually administered either by the cable operator or by a third party designated by the franchising authority. Educational access channels are used by educational institutions for educational programming. Time on these channels is typically allocated among local schools, colleges, and universities by either the franchising authority or the cable operator. Governmental access channels are used for programming by local governments. Federal Communications Commission, "Public, Educational, and Governmental Access Channels ('PEG Channels')," https://www.fcc.gov/media/public-educational-and-governmental-access-channels-peg-channels. |

| 8. |

P.L. No. 73-416, 48 Stat. 1064. |

| 9. |

In 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the FCC's authority to regulate cable was "reasonably ancillary to the effective performance of the Commission's various responsibilities for the regulation of television broadcasting." U.S. v. Southwestern Cable Co., 392 U.S. 157 (1968). |

| 10. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Cable Television Report and Order, FCC 72-108," 36 FCC Reports, 2nd Series 143, 166-167, February 3, 1972 (1972 Cable Order). |

| 11. |

1972 Cable Order, pp. 190-192. The new rules required cable operators to file Certificates of Compliance with the FCC before commencing operations or adding new channels. The operators had to certify that their franchising authorities complied with franchising rules set forth by the FCC. In 1978, the FCC—having found the certification process unwieldy—instead directed cable operators to register their systems with the agency. Federal Communications Commission, "Amendment of Part 76 – CATV Certificate of Compliance Report and Order, FCC 78-690," 69 FCC Reports, 2nd Series 697, October 13, 1978. |

| 12. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Clarification of the Cable Television Rules and Notice of Proposed Rulemaking and Inquiry, FCC 74-384," 46 FCC Reports, 2nd Series 181, April 15, 1974. |

| 13. |

FCC v. Midwest Video Corp., 440 U.S. 689 (1979). The court found that the FCC's rules exceeded the agency's authority under the 1934 Communications Act, as amended at that time. |

| 14. |

Parsons, pp. 374-375. |

| 15. |

1984 House Energy and Commerce Committee Report, p. 34. |

| 16. |

1972 Cable Order, p. 209. The FCC subsequently named the examples. For instance, it stated that prior to 1972, the cable franchise for Colorado Springs, CO, provided for a fee of up to 35%, and the franchises in at least eight other cities (including St. Petersburg, FL; Elkhart, IN; Brunswick, ME; and Sedalia, MO) provided for fees of 10%. |

| 17. |

Ibid., p. 210. |

| 18. |

1984 House Energy and Commerce Committee Report, p. 24. |

| 19. |

1972 Cable Order, pp. 276-277. |

| 20. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Amendment of Subpart C of Part 76 of the Commission's Rules and Regulations Regarding the Regulation of Cable Television System Regular Subscriber Fees, Report and Order, FCC 76-747," 46 FCC Reports, 2nd Series 672, 684-686, August 13, 1976. |

| 21. |

1974 Cable Rules Clarification, pp. 199-200. |

| 22. |

1984 Cable Act, §621. [47 U.S.C. §541.] See also, 1984 House Energy and Commerce Committee Report, p. 19. |

| 23. |

1984 Cable Act, §636(a). [47 U.S.C. §556(a).] |

| 24. |

In January 1982, the largest U.S. telephone company, AT&T, and the DOJ reached a settlement whereby AT&T agreed to divest its regional telephone subsidiaries, known as local exchange carriers (LECs), and keep its long distance operations. The reorganization became effective on January 1, 1984. The settlement, known as the modified final judgment, also prohibited the LECs from offering video services. U.S. v. AT&T, 552 F. Supp. 131 (D.D.C. 1982), aff'd, 103 S.Ct. 1240 (1983). The 22 subsidiaries that AT&T spun off subsequently reorganized into seven regional operating companies. Parsons, pp. 433-434. The divestiture became effective on January 1, 1984. |

| 25. |

1984 Cable Act, §613(b) ("Ownership Restrictions"). |

| 26. |

1984 Cable Act, §622 (h)(2), ("Franchise Fees") [47 U.S.C. §542(h)(2)]. |

| 27. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Implementation of Section 621(a)(1) of the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 as Amended by the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, FCC 08-180," 22 FCC Record 5101, 5146, n. 328, March 5, 2007. |

| 28. |

1984 Cable Act, §611 ("Channels for Public, Educational, or Governmental Use"), (47 U.S.C. §531). |

| 29. |

1984 Cable Act, §622 (47 U.S.C. §542). For franchise agreements granted after 1984, the costs of supporting PEGs may not exceed the overall 5% franchise fee cap when added to any other payments deemed part of franchise fees. |

| 30. |

Ibid., §611(f) (47 U.S.C. §531(f)). |

| 31. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Implementations of the Provisions of the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984," 50 Federal Register 18636, 18649-18551, May 2, 1985. |

| 32. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Reexamination of the Effective Competition Standard for the Regulation of Cable Television Basic Service Rates, Report and Order and Second Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking," 6 FCC Record 4545, July 12, 1991. |

| 33. |

U.S. General Accounting Office, Telecommunications: 1991 Survey of Cable Television Rates and Services, RCED-91-195, July 18, 1991, p. 4, https://www.gao.gov/products/144611. |

| 34. |

1992 Cable Act, § 2(b). |

| 35. |

Anita Wallgren et al., Video Program Distribution and Cable Television: Current Policy Issues and Recommendations, U.S. Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications and Information Administration, NTIA Report 88-233, June 1988, p. 20, https://www.ntia.doc.gov/legacy/reports/NTIA_88233_VideoDialtoneReportJune88.pdf. |

| 36. |

47 U.S.C. §541(a)(1). |

| 37. |

1992 Cable Act, §7. |

| 38. |

47 U.S.C. §555(a). |

| 39. |

47 U.S.C. §543(l). |

| 40. |

Section 602(13) of the Communications Act defines a "multichannel video programming distributor" as "a person such as, but not limited to, a cable operator, a multichannel multipoint distribution service, a direct broadcast satellite service, or a television receive-only satellite program distributor, who makes available for purchase, by subscribers or customers, multiple channels of video programming." [47 USC §522(13).] |

| 41. |

As defined by the Telecommunications Act of 1996 §3(2), a "local exchange carrier" means "any person that is engaged in the provision of telephone exchange service or exchange access. Such term does not include a person insofar as a person is engaged in the provision of commercial mobile service under section 332(c), except to the extent that the [FCC] finds that such service should be included in the definition of such term." [47 U.S.C. §153(32).] |

| 42. |

The FCC has called this fourth category the "LEC test." Federal Communications Commission, "Petition for Determination of Effective Competition, Report and Order, FCC 19-110," October 25, 2019, p. 1, https://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-grants-charter-communications-effective-competition-petition-0 (2019 Effective Competition Order). |

| 43. |

47 U.S.C. §543(l). |

| 44. |

Parsons, pp. 609, 613. |

| 45. |

Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company of Virginia v. U.S., 830 F. Supp. 909 (E.D. Va. 1993), aff'd, 42 F.3d 181 (4th Cir. 1994). |

| 46. |

Parsons, p. 620. |

| 47. |

1996 Telecommunications Act, §302(b) [Repealing 47 U.S.C. §533(b)]. See also 1995 Senate Commerce Committee Report, p. 6. |

| 48. |

47 U.S.C. §152 note. |

| 49. |

P.L. 104-104 Sec. 303(a) [47 U.S.C. §541(b)(3)]. |

| 50. |

1995 Senate Commerce Committee Report, p. 36. |

| 51. |

Ibid. For historical perspective about the relationship between the FCC and local government authorities with respect to the regulation of telecommunications services, see Jonathan Jacob Nadler, "Give Peace a Chance: FCC-State Relations After California III," Federal Communications Law Journal, vol. 47, no. 3 (1995), p. 457. |

| 52. |

47 U.S.C. §573. |

| 53. |

City of Dallas, TX v. FCC, 165 F. 3d 341 (5th Cir. 1999). |

| 54. |

Telecommunications and Cable Regulation, v. 1, "13.03(d)(ii): Federal Substantive Franchise Related Requirements/Restrictions; Telephone Companies as Video Providers." |

| 55. |

Ted Hearn, "'Open Video Systems' a Turn Off," Multichannel News, February 24, 2006, https://www.multichannel.com/news/open-video-systems-turn-269072. While AT&T does not classify its U-Verse service as a "cable operator" for the purpose of the Communications Act, it abides by sections of the Communications Act governing the retransmission broadcast television programming for its U-Verse service. AT&T has stated that it considers U-Verse to be a "video service" under the Communications Act, rather than a "cable service." AT&T Inc., SEC Form 10-K for the Fiscal Year ended December 31, 2014, p. 3. In contrast, Verizon has stated that its video service "is regulated like a traditional cable service. The FCC has a body of rules that apply to cable operators, and these rules also generally apply to Verizon." Verizon Communications Inc., SEC Form 10-K for the Fiscal Year ended December 31, 2018, p. 14. |

| 56. |

Pacific Bell Telephone Company (d/b/a AT&T California) v. City of Walnut Creek and the City Council of Walnut Creek, 428 F. Supp.2d 1037 (N.D. Ca 2006). AT&T also claimed that the cities violated state law, but the judge declined to exercise jurisdiction over this claim. |

| 57. |

Linda Haugsted, "AT&T Loses California Challenge; U.S. Court Won't Rule Walnut Creek Buildout Isn't Cable," Multichannel News, April 24, 2006. The FCC has likewise not made such a ruling. In the meantime, Verizon has registered its FiOS service with the FCC as a cable system, whereas AT&T service has not done so for its U-Verse service. Federal Communications Commission, "Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition in the Market for Video Programming, 15th Report, FCC 13-99," 28 Federal Register 10496, 10507, July 22, 2013. |

| 58. |

Christian Lewis, "Breaking Into the Big Apple; Verizon Push Could Change the Rules in New York City," Multichannel News, August 28, 2006. |

| 59. |

"Cities to Fight Moves for National Cable Franchising Systems," Communications Daily, June 10, 2005. |

| 60. |

S.B. 5, an Act Furthering Competition in the Communications Industry, S 5, 79th Leg., 2d Sess. (Tex. 2005), (codified in Tex. Public Utilities Code Ann. §66.001 et seq). The Texas Public Utility Commission grants state-issued certificates of franchise authority. This franchising authority expires on September 1, 2025. |

| 61. |

For additional information about the FCC's rulemakings and related court challenges, see CRS Report R46147, The Cable Franchising Authority of State and Local Governments and the Communications Act, by Chris D. Linebaugh and Eric N. Holmes. |

| 62. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Implementation of Section 621(a)(1) of the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 as Amended by the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking," 22 FCC Record 5101, March 5, 2007 (March 2007 LFA Order). |

| 63. |

March 2007 LFA Order, n. 2. |

| 64. |

Ibid., p. 5156. |

| 65. |

The FCC referred to examples described in a 2005 article from the Wall Street Journal. Ibid., p. 5105. Dionne Searcey, "Spotty Reception—as Verizon Enters Cable Business, It Faces Local Static—Telecom Giant Gets Demands as it Negotiates TV Deals," Wall Street Journal, October 25, 2005. For example, the article stated that in the State of New York, Verizon faced requests for seed money for wildflowers and a video hookup for Christmas celebrations. The FCC stated that parties commenting in its proceeding indicated that they were unwilling to specify instances of unreasonable noncable in-kind requests from LFAs, since they were still trying to negotiate with the LFAs at issue. March 2007 LFA Order, n. 352. |

| 66. |

March 2007 LFA Order, p. 5150. |

| 67. |

This statement applied to franchises granted after 1984. |

| 68. |

Ibid., pp. 5150-5151. |

| 69. |

In its order, the FCC used the term "video programming" and "video services" to refer to the "cable services" described in the 1934 Communications Act. March 2007 LFA Order, n. 3. |

| 70. |

47 U.S.C. §522(7)(C). |

| 71. |

The FCC delineated two applicable time frames: 90 days for applicants, such as LECs, with already existing authorizations for access to rights-of-way, and six months for all other competitive franchise applicants. |

| 72. |

Build-out requirements necessitate that a franchisee deploy cable services to all households in a given franchise area within a specified time frame. The principal statutory limitation on the right of LFAs to impose build-out requirements is that they allow the applicant a reasonable amount of time to do so. The build-out provisions are intended to meet one of the goals of the Communications Act, that is, that "cable service is not denied to any group of potential residential cable subscribers because of the income of the residents of the local area in which such group resides." Alliance for Community Media. v. FCC, 529 F. 3d 763, 771 n. 6 (6th Cir. 2008). |

| 73. |

As an example of such an unreasonable demand, the FCC stated that it would be "unreasonable for an LFA to impose on a new entrant more burdensome PEG carriage obligations than it has imposed upon the incumbent cable operator." |

| 74. |

Alliance for Community Media v. FCC, 529 F. 3d 763 (6th Cir. 2008). |

| 75. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Implementation of Section 621(a)(1) of the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 as Amended by the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992, Second Report and Order," 22 FCC Record 19633, November 6, 2007 (November 2007 LFA 2nd Report and Order). |

| 76. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Implementation of Section 621(a)(1) of the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 as Amended by the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992, Order on Reconsideration," 30 FCC Record 810, January 21, 2015 (January 2015 LFA Reconsideration Order). |

| 77. |

January 2015 LFA Reconsideration Order, pp. 812-813. |

| 78. |

Ibid., pp. 814-815. |

| 79. |

November 2007 LFA 2nd Report and Order, p. 19638. |

| 80. |

January 2015 LFA Reconsideration Order, pp. 815-816. |

| 81. |

November 2007 LFA 2nd Report and Order, pp. 19640-19641; January 2015 LFA Reconsideration Order, pp. 816-817. |

| 82. |

The FCC stated an LFA's imposition of more burdensome PEG carriage obligations on an incumbent than on a new entrant would not be unreasonable. November 2007 LFA 2nd Report and Order, p. 19639. In addition, the FCC noted that it had previously found that an LFA's requirements that a new entrant construct an I-Net that duplicated the I-Net of the incumbent cable operator, or have the same PEG channel commitments as the incumbent cable operator, were unreasonable. The FCC stated this standard of unreasonableness did not apply to incumbent cable operators. Ibid., pp. 19639-19640. |

| 83. |

November 2007 LFA 2nd Report and Order, p. 19636. |

| 84. |

Ibid., pp. 19636-19637. |

| 85. |

Montgomery County, Maryland v. FCC, 863 F.3d 485 (6th Cir. 2017) (Montgomery County). |

| 86. |

Montgomery County, pp. 494-495. |

| 87. |

Ibid., p. 491 |

| 88. |

Ibid., p. 492. |

| 89. |

Ibid., p. 493. |

| 90. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Implementation of Section 621(a)(1) of the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 as Amended by the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992, Second Further Notice and Proposed Rulemaking," 33 FCC Record 8952, 8964-8965, September 25, 2018 (2018 LFA 2nd FNPRM). |

| 91. |

2018 LFA 2nd FNPRM. |

| 92. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Matter of Interpretation of Section 621(a)(1) of the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 as Amended by the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992, FCC 19-80, Third Report and Order," August 2, 2019, 34 FCC Record 6844 (2019 LFA 3rd R&O). |

| 93. |

Ibid., p. 6858. |

| 94. |

Ibid., p. 6899. |

| 95. |