U.S.-China Tariff Actions by the Numbers

Since early 2018, the United States and China have imposed a series of tariffs against one another’s products. These tariffs now affect the majority of trade between the two countries. U.S. tariffs imposed under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 (which followed an investigation on China’s intellectual property rights practices) and China’s retaliatory tariffs affect the largest share of U.S.-China trade. Earlier U.S. tariffs (and Chinese retaliation) on steel and aluminum (Section 232) and solar panels and washing machines (Section 201) also affect U.S.-China trade. The Trump Administration argues that by reducing U.S. demand for Chinese exports, the tariffs are an effective tool to pressure China to change its policies. The tariffs, however, also impose costs on U.S. stakeholders—U.S. tariffs increase the price U.S. firms and consumers pay on imports from China, while China’s retaliatory tariffs disadvantage U.S. exporters by making U.S. products relatively more expensive in the Chinese market.

U.S.-China Tariff Actions by the Numbers

Contents

- Overview

- Timeline of Key Actions, Affected Trade, and Tariff Increases

- U.S. Goods Imports Covered by Tariff Actions

- Chinese Goods Imports Covered by Tariff Actions

- Conclusion

Figures

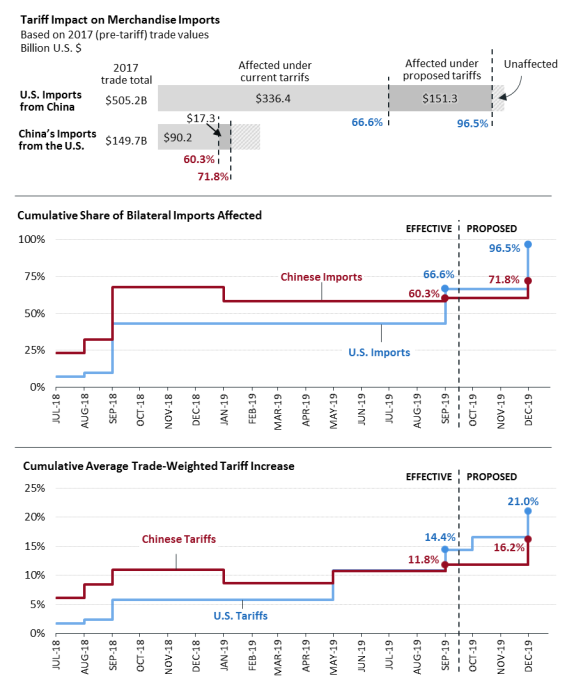

- Figure 1. Bilateral Trade Affected by Tariff Actions and Average Tariff Increases

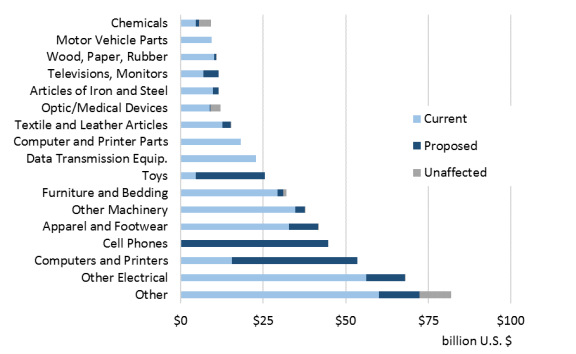

- Figure 2. U.S. Imports from China Affected by Tariff Actions, by Category

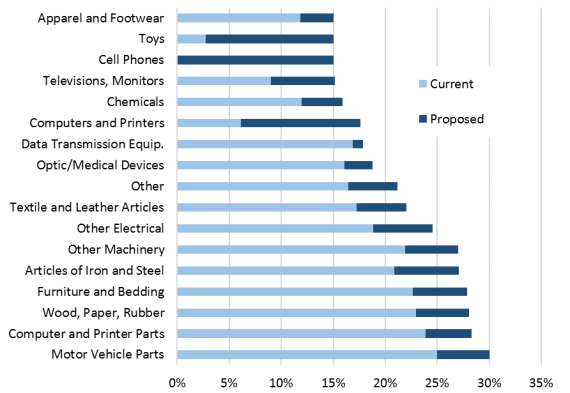

- Figure 3. Average Tariff Increases on U.S. Imports from China, by Category

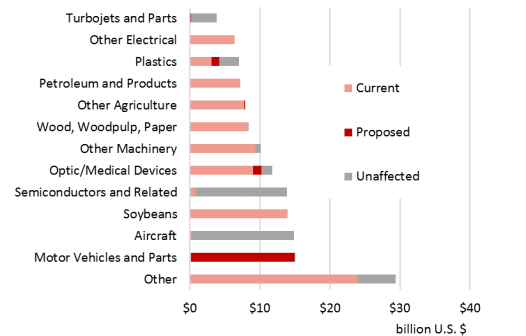

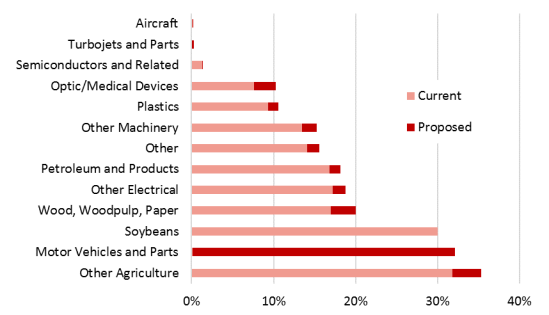

- Figure 4. Chinese Imports from the United States Affected by Retaliatory Tariffs, by Category

- Figure 5. Average Tariff Increases on Chinese Imports from the United States, by Category

Overview

Since early 2018, the United States and China have imposed a series of tariffs against one another's products, and these tariffs now affect a majority of trade between the two countries. U.S. tariffs imposed under Section 3011 of the Trade Act of 1974 (which followed an investigation on China's intellectual property rights [IPR] practices) and China's retaliatory tariffs affect the largest share of U.S.-China trade. Earlier U.S. tariffs (and Chinese retaliation) on steel and aluminum (Section 232)2 and solar panels and washing machines (Section 201)3 also affect U.S.-China trade.4 The Trump Administration argues that because they reduce U.S. demand for Chinese exports, the tariffs are an effective tool to pressure China to change its policies. The tariffs, however, also impose costs on U.S. stakeholders—U.S. tariffs increase the price U.S. firms and consumers pay on imports from China, while China's retaliatory tariffs disadvantage U.S. exporters by making U.S. products relatively more expensive in the Chinese market.5

In May 2019, citing a lack of progress in bilateral talks to address U.S. concerns, President Trump announced his intent to increase existing Section 301 tariffs and expand the range of products covered, leading to a series of escalations by both sides through the summer.6 In the midst of these tariff escalations, China allowed its currency to depreciate to an 11-year low, prompting the Trump Administration to declare China a "currency manipulator" under U.S. law.7 As of September 1, approximately 67% of U.S. imports from China are subject to increased tariffs, most in the range of 15%-25%, while approximately 60% of China's imports from the United States face additional tariffs, most in the range of 5%-25%.8 These totals are an upper-bound estimate of total affected trade, as both countries have excluded a limited number of products from implemented tariff increases (see text box below).

Both sides are set to increase tariffs further by the end of the year. On October 15, 2019, the United States is to increase many existing tariffs from 25% to 30%. On December 15, 2019, the United States is to impose an additional 15% tariff on most remaining imports from China and China is to both expand the coverage of its tariffs and increase certain existing tariffs (Figure 1).

The Administration launched its Section 301 investigation on China due to concerns over China's policies on IPR, subsidies, technology, and innovation and those policies' impact on U.S. stakeholders.9 The investigation concluded that four broad policies or practices justified U.S. action: (1) China's forced technology transfer requirements, (2) cyber-enabled theft of U.S. IP and trade secrets, (3) discriminatory and nonmarket licensing practices, and (4) state-funded strategic acquisition of U.S. assets.10 The Administration determined that increased tariffs on U.S. imports from China were an appropriate action to encourage China to alter its policies and practices.11

The Trump Administration may have attempted to shield U.S. consumers from early tariff actions by targeting intermediate goods, but consumers may increasingly feel the effects of the tariffs, as the most recent and next round of tariff increases include major consumer goods such as cell phones, computers, apparel, and toys. There is also increasing concern that the tariffs may have negative effects on the U.S. economy. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the tariff increases in effect as of July 25 will reduce the level of real U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) by 0.3% by 2020.12 Uncertainty stemming from the fluctuating tariffs may also be dampening U.S. and Chinese business activity, including new investments. Analysis of earnings calls show that tariffs are a significant concern for many U.S. executives,13 and preliminary research suggests uncertainty from the tariffs may have reduced aggregate U.S. investment by 1% or more in 2018.14 Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell cited concerns over weakening investment and exports, which he tied to trade policy uncertainty, as a main driver of the decision to lower interest rates in September.15 The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that global trade conflicts will lead to a $700 billion loss to global GDP by 2020.16

While overall bilateral trade increased in 2018, exports of products facing the most severe tariff increases, particularly U.S. agriculture exports, declined.17 As the tariffs increased during 2019, U.S.-China bilateral trade flows decreased significantly. Preliminary official U.S. data for 2019 indicate that—compared to the first eight months of 2018—U.S. merchandise exports to China dropped by 16% (down $13.4 billion), while U.S. imports from China fell by 13% (down $43.2 billion).18 In order to provide a snapshot of the scale and scope of the escalating trade conflict, this report examines 2017 trade flows of affected products, before they were affected by the tariffs and trade-weighted average tariff increases.19 The trade values have not been adjusted to account for specific product exclusions implemented by both countries (see text box below).

|

Limited U.S. and Chinese Product Exclusions from Tariff Increases The United States and China have both excluded a limited number of products from implemented tariff increases, reducing the value of products affected by the tariffs. The scale of exclusions is relatively small for both countries. On September 11, 2019, China's Ministry of Finance announced that 15 tariff lines would be excluded from the retaliatory tariff actions (more than 5,500 tariff lines are currently affected by retaliatory tariffs). The United States has established a formal domestic process for requesting tariff exclusions, administered by the United States Trade Representative (USTR). USTR has issued tariff exclusions on a rolling basis, covering roughly 350 tariff lines to date (more than 8,000 tariff lines are currently affected by additional U.S. tariffs). For both countries, the exclusions only apply to specific products within each tariff line, making it difficult to determine the precise amount of trade covered by the exclusions. While the product exclusions provide tariff relief for certain importers and lower the total value of U.S. trade affected by the tariffs, the application process also involves administrative costs for applicants. Sources: Ministry of Finance of the People's Republic of China, "Taxation Committee Announcement 6," September 11, 2019, http://gss.mof.gov.cn/zhengwuxinxi/zhengcefabu/201909/t20190911_3384638.html. USTR, "China Section 301-Tariff Actions and Exclusion Process," https://ustr.gov/issue-areas/enforcement/section-301-investigations/tariff-actions. |

Timeline of Key Actions, Affected Trade, and Tariff Increases

Since July 2018, six major tariff actions have occurred in the U.S.-China Section 301 trade dispute, with two additional actions proposed to occur on October 15 and December 15, 2019. The tariffs affect a significant share of each country's imports. U.S. tariffs currently affect 66.6% of U.S. imports from China, which is to set to grow to 96.5% once all proposed tariff increases take effect. Meanwhile, China has imposed additional tariffs on 60.3% of its imports from the United States, which is set to rise to 71.8% by the end of the year. (See Figure 1, which shows the share of U.S-China bilateral trade affected by each successive tariff action and the average trade-weighted tariff increase applied to each country's overall bilateral imports.)

The scale of the tariff increases—applied on top of the most-favored nation (MFN) tariff rates each country applies to other members of the World Trade Organization (WTO)—is significant. Currently, the United States has effectively increased it average trade-weighted tariffs on goods from China by 14.4%, more than four times the U.S. average MFN rate of 3.4%.20 By the end of the year, the average tariff is scheduled to increase to 21.0% (Figure 1). On average, China has imposed an additional 11.8% tariff on its imports from the United States, which is to rise to 16.2% if all proposed tariff increases take effect. China's average MFN tariffs were 9.8% in 2018,21 and fell throughout the year as it reduced its global tariffs while increasing tariffs on imports from the United States.22

U.S. Goods Imports Covered by Tariff Actions

U.S. tariff increases on imports from China now encompass most trade in major import categories, with the exception of toys, cell phones, and computers. These categories are scheduled to be subject to an additional 15% tariff on December 15, 2019 (Figure 2). Major import categories (by share of annual imports) with some portion of trade unaffected by the Administration's implemented or proposed tariff increases include chemicals and medical devices. An examination of average U.S. tariff increases by product category shows that intermediate goods (including motor vehicle parts) face the largest tariff increases (nearly 30% if all proposed tariffs take effect), while consumer goods sectors (including apparel and footwear, toys, cell phones, and televisions) face the lowest tariff increases (roughly 15% once all proposed tariffs take effect) (Figure 3).

Chinese Goods Imports Covered by Tariff Actions

While the United States has implemented or proposed tariff increases on all major product categories, China has repeatedly targeted some product groups, particularly agriculture, while entirely excluding others. For example, China has largely excluded turbojets and parts, semiconductors and related devices, certain plastics, and aircraft from its retaliatory tariffs (Figure 4). If all the proposed tariffs take effect, roughly one-third of China's imports from the United States will remain unaffected by the tariff increases. In part, this reflects the fact that China's most recent announcements largely increased existing retaliatory tariffs instead of targeting new products. Motor vehicles and parts, which accounted for $15 billion of imports from the United States in 2017, is the only category to face new tariffs in coming months.23 If these auto tariffs take effect, this sector will face an average retaliatory tariff rate of just above 30% (Figure 5). Agriculture products have been hit the hardest by China's retaliation. Soybeans, which face retaliation to both the U.S. Section 232 and Section 301 actions, are currently subject to an increased tariff of 30%. Other agricultural products are currently subject to an average 32% tariff increase, which will grow to 35% once China implements all proposed tariffs.

Conclusion

The United States and China have imposed a series of tariffs on one another's imports, and these tariffs now affect the majority of trade between the two countries. If all scheduled tariff increases take effect, by the end of 2019 nearly all U.S. imports from China will be subject to new or increased tariffs, most in the range of 15%-30%, while approximately two-thirds of China's imports from the United States will be subject to new or increased tariffs, most in the range of 5%-30%. The United States initially imposed tariffs primarily on intermediate goods, but consumer goods including cell phones, computers, and toys are scheduled to face new tariffs on December 15, 2019. China's retaliatory tariffs have largely targeted agricultural products, particularly soybeans, while aircraft and semiconductors have mostly been excluded from Chinese tariff increases. New Chinese tariffs on U.S. motor vehicle and parts exports are likely to be the most economically significant from China's next proposed retaliation. Both countries have excluded a limited number of specific products from implemented tariff increases. The trade values in this product have not been adjusted to account for these limited exclusions (see text box above).

Congress has constitutional authority over U.S. tariff policy. The Administration has increased tariffs on imports from China using authorities delegated by Congress in legislation. Many U.S. stakeholders have been or will soon be affected by the President's tariff actions, given the scale of implemented and proposed tariff increases. Congress may wish to evaluate the Administration's ultimate objectives from the tariff increases, whether potential benefits justify potential costs, and whether the President's tariff actions align with Congress's intended use of its delegated authority.

|

Related CRS Products CRS Insight IN10943, Escalating U.S. Tariffs: Timeline, coordinated by Brock R. Williams. CRS Insight IN10971, Escalating U.S. Tariffs: Affected Trade, coordinated by Brock R. Williams. CRS Report R45529, Trump Administration Tariff Actions (Sections 201, 232, and 301): Frequently Asked Questions, coordinated by Brock R. Williams. CRS In Focus IF10708, Enforcing U.S. Trade Laws: Section 301 and China, by Wayne M. Morrison. CRS Report R45903, Retaliatory Tariffs and U.S. Agriculture, by Anita Regmi. |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

CRS In Focus IF10708, Enforcing U.S. Trade Laws: Section 301 and China, by Wayne M. Morrison. |

| 2. |

CRS In Focus IF10786, Safeguards: Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974, by Vivian C. Jones. |

| 3. |

CRS In Focus IF10667, Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, by Rachel F. Fefer and Vivian C. Jones. |

| 4. |

Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 allows the President to impose temporary duties and other trade measures if the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) determines a surge in imports is a substantial cause or threat of serious injury to a U.S. industry. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 allows the President to adjust imports if the Department of Commerce finds certain products are imported in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair U.S. national security. Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 allows the United States Trade Representative (USTR) to suspend trade agreement concessions or impose import restrictions if it determines a U.S. trading partner is violating trade agreement commitments or engaging in discriminatory or unreasonable practices that burden or restrict U.S. commerce. |

| 5. |

Mary Amiti, Stephen J. Redding, and David Weinstein, The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 25672, March 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w25672.pdf. |

| 6. |

For more detail on the U.S. and Chinese tariff actions, see CRS Insight IN10971, Escalating U.S. Tariffs: Affected Trade, coordinated by Brock R. Williams and CRS Insight IN10943, Escalating U.S. Tariffs: Timeline, coordinated by Brock R. Williams. |

| 7. |

CRS Insight IN11154, The Administration's Designation of China as a Currency Manipulator, by Rebecca M. Nelson. |

| 8. |

Based on 2017 trade values. Data for U.S. imports come from the U.S. Census Bureau and data for China's imports come from China Customs, both via Global Trade Atlas IHS Markit. This product provides analysis of China's retaliatory tariffs using China's import data rather than U.S. export data, because product classifications differ between countries, making it difficult to match U.S. trade values with the specific products subject to the tariff measures. |

| 9. |

USTR, "Initiation of Section 301 Investigation: China's Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation," 82 Federal Register 40213-40215, August 24, 2017. |

| 10. |

White House, "Presidential Memorandum on the Actions by the United States Related to the Section 301 Investigation," March 22, 2018. USTR has estimated that these policies cost the U.S. economy at least $50 billion annually (Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, "Section 301 Fact Sheet," March 22, 2018). |

| 11. |

USTR, "Notice of Determination of Action Pursuant to Section 301: China's Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation," 83 Federal Register 14906-14954, April 6, 2018. |

| 12. |

Daniel Fried, "The Effects of Tariffs and Trade Barriers in CBO's Projections," Congressional Budget Office, August 22, 2019, at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/55576. |

| 13. |

Thaddeus Swanek, "Survey Finds Growing Concern about Tariffs Among Fortune 500 Executives," U.S. Chamber of Commerce, September 6, 2019, https://www.uschamber.com/series/above-the-fold/survey-finds-growing-concern-about-tariffs-among-fortune-500-executives. |

| 14. |

Dario Caldara, Matteo Iacoviello, and Patrick Molligo, et al., The Economic Effects of Trade Policy Uncertainty, International Finance Discussion Papers 1256, September 2019, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/ifdp/files/ifdp1256.pdf. |

| 15. |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, "Transcript of Chair Powell's Press Conference," September 18, 2019, https://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20190918.pdf. |

| 16. |

Kristina Georgieva, IMF Managing Director, "Decelerating Growth Calls for Accelerating Action," October 8, 2019, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/10/03/sp100819-AMs2019-Curtain-Raiser. |

| 17. |

CRS Report R45903, Retaliatory Tariffs and U.S. Agriculture, by Anita Regmi. |

| 18. |

Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services August 2019, October 4, 2019, https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2019-10/trad0819.pdf#page=29. |

| 19. |

The effects of the tariff increases appear less severe using 2018 data, because of the decline in trade of products like soybeans that face the highest tariff increases. |

| 20. |

WTO, World Tariff Profiles 2019, pg. 12, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/tariff_profiles19_e.pdf. |

| 21. |

WTO, World Tariff Profiles 2019, pg. 8, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/tariff_profiles19_e.pdf. |

| 22. |

Chad P. Bown, Euijin Jung, and Eva Zhang, Trump Has Gotten China to Lower Its Tariffs. Just Toward Everyone Else., Peterson Institute for International Economics, June 11, 2019, https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/trump-has-gotten-china-lower-its-tariffs-just-toward. |

| 23. |

Motor vehicles and parts were previously covered by China's retaliatory tariff actions, but these tariffs were removed in January 2019 after the two countries agreed to a temporary de-escalation of tariff actions. Over the summer of 2019 as the trade conflict escalated, China announced its intent to re-impose tariffs on U.S. motor vehicle and parts imports, effective December 15, 2019. For more information, see Ministry of Finance of the People's Republic of China, "Taxation Committee Announcement 5," http://gss.mof.gov.cn/zhengwuxinxi/zhengcefabu/201908/t20190823_3372941.html. |