Kashmir: Background, Recent Developments, and U.S. Policy

In early August 2019, the Indian government announced that it would make major changes to the legal status of its Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) state, specifically by repealing Article 370 of the Indian Constitution and Section 35A of its Annex, which provided the state “special” autonomous status, and by bifurcating the state into two successor “Union Territories” with more limited indigenous administrative powers. The changes were implemented on November 1, 2019. The former princely region’s sovereignty has been unsettled since 1947 and its territory is divided by a military “Line of Control,” with Pakistan controlling about one-third and disputing India’s claim over most of the remainder as J&K (China also claims some of the region’s land). The United Nations considers J&K to be disputed territory, but New Delhi, the status quo party, calls the recent legal changes an internal matter, and it generally opposes third-party involvement in the Kashmir issue. U.S. policy seeks to prevent conflict between India and Pakistan from escalating, and the U.S. Congress supports a U.S.-India strategic partnership that has been underway since 2005, while also maintaining attention on issues of human rights and religious freedom.

India’s August actions sparked international controversy as “unilateral” changes of J&K’s status that could harm regional stability, eliciting U.S. and international concerns about further escalation between South Asia’s two nuclear-armed powers, which nearly came to war after a February 2019 Kashmir crisis. Increased separatist militancy in Kashmir may also undermine ongoing Afghan peace negotiations, which the Pakistani government facilitates. New Delhi’s process also raised serious constitutional questions and—given heavy-handed security measures in J&K—elicited more intense criticisms of India on human rights grounds. The United Nations and independent watchdog groups fault New Delhi for excessive use of force and other abuses in J&K (Islamabad also comes under criticism for alleged human rights abuses in Pakistan-held Kashmir). India’s secular traditions may suffer as India’s Hindu nationalist government—which returned to power in May with a strong mandate—appears to pursue Hindu majoritarian policies at some cost to the country’s religious minorities.

The long-standing U.S. position on Kashmir is that the territory’s status should be settled through negotiations between India and Pakistan while taking into consideration the wishes of the Kashmiri people. The Trump Administration has called for peace and respect for human rights in the region, but its criticisms have been relatively muted. With key U.S. diplomatic posts vacant, some observers worry that U.S. government capacity to address South Asian instability is thin, and the U.S. President’s July offer to “mediate” on Kashmir may have contributed to the timing of New Delhi’s moves. The United States seeks to balance pursuit of a broad U.S.-India partnership while upholding human rights protections, as well as maintaining cooperative relations with Pakistan.

Following India’s August 2019 actions, numerous Members of the U.S. Congress went on record in support of Kashmiri human rights. H.Res. 745, introduced in December and currently with 40 cosponsors, urges the Indian government to end the restrictions on communications and mass detentions in J&K that continue to date. An October hearing on human rights in South Asia held by the House Subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific, and Nonproliferation included extensive discussion of developments in J&K. In November, the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission held an event entitled “Jammu and Kashmir in Context.”

This report provides background on the Kashmir issue, reviews several key developments in 2019, and closes with a summary of U.S. policy and possible questions for Congress.

Kashmir: Background, Recent Developments, and U.S. Policy

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview

- Recent Developments

- Status and Impact of India's Crackdown

- The U.S.-India "2+2" Summit and Other Recent Developments

- Background

- Setting

- J&K's Status, Article 370, and India-Pakistan Conflict

- Accession to India

- Article 370 and Article 35A of the Indian Constitution, and J&K Integration

- Further India-Pakistan Wars

- Third-Party Involvement

- Separatist Conflict and President's Rule From 2018

- Three Decades of Separatist Conflict

- 2018 J&K Assembly Dissolution and President's Rule

- Developments in 2019

- The February Pulwama Crisis

- President Trump's July "Mediation" Offer

- August Abrogation of Article 370 and J&K Reorganization

- Responses and Concerns

- International Reaction

- The Trump Administration

- The U.S. Congress, Hearings, and Relevant Legislation

- Pakistan

- China

- The United Nations

- Other Responses

- Human Rights and India's International Reputation

- Democracy and Other Human Rights Concerns

- Potential Damage to India's International Image

- U.S. Policy and Issues for Congress

Summary

In early August 2019, the Indian government announced that it would make major changes to the legal status of its Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) state, specifically by repealing Article 370 of the Indian Constitution and Section 35A of its Annex, which provided the state "special" autonomous status, and by bifurcating the state into two successor "Union Territories" with more limited indigenous administrative powers. The changes were implemented on November 1, 2019. The former princely region's sovereignty has been unsettled since 1947 and its territory is divided by a military "Line of Control," with Pakistan controlling about one-third and disputing India's claim over most of the remainder as J&K (China also claims some of the region's land). The United Nations considers J&K to be disputed territory, but New Delhi, the status quo party, calls the recent legal changes an internal matter, and it generally opposes third-party involvement in the Kashmir issue. U.S. policy seeks to prevent conflict between India and Pakistan from escalating, and the U.S. Congress supports a U.S.-India strategic partnership that has been underway since 2005, while also maintaining attention on issues of human rights and religious freedom.

India's August actions sparked international controversy as "unilateral" changes of J&K's status that could harm regional stability, eliciting U.S. and international concerns about further escalation between South Asia's two nuclear-armed powers, which nearly came to war after a February 2019 Kashmir crisis. Increased separatist militancy in Kashmir may also undermine ongoing Afghan peace negotiations, which the Pakistani government facilitates. New Delhi's process also raised serious constitutional questions and—given heavy-handed security measures in J&K—elicited more intense criticisms of India on human rights grounds. The United Nations and independent watchdog groups fault New Delhi for excessive use of force and other abuses in J&K (Islamabad also comes under criticism for alleged human rights abuses in Pakistan-held Kashmir). India's secular traditions may suffer as India's Hindu nationalist government—which returned to power in May with a strong mandate—appears to pursue Hindu majoritarian policies at some cost to the country's religious minorities.

The long-standing U.S. position on Kashmir is that the territory's status should be settled through negotiations between India and Pakistan while taking into consideration the wishes of the Kashmiri people. The Trump Administration has called for peace and respect for human rights in the region, but its criticisms have been relatively muted. With key U.S. diplomatic posts vacant, some observers worry that U.S. government capacity to address South Asian instability is thin, and the U.S. President's July offer to "mediate" on Kashmir may have contributed to the timing of New Delhi's moves. The United States seeks to balance pursuit of a broad U.S.-India partnership while upholding human rights protections, as well as maintaining cooperative relations with Pakistan.

Following India's August 2019 actions, numerous Members of the U.S. Congress went on record in support of Kashmiri human rights. H.Res. 745, introduced in December and currently with 40 cosponsors, urges the Indian government to end the restrictions on communications and mass detentions in J&K that continue to date. An October hearing on human rights in South Asia held by the House Subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific, and Nonproliferation included extensive discussion of developments in J&K. In November, the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission held an event entitled "Jammu and Kashmir in Context."

This report provides background on the Kashmir issue, reviews several key developments in 2019, and closes with a summary of U.S. policy and possible questions for Congress.

Overview

The final status of the former princedom of Kashmir has remained unsettled since 1947. On August 5, 2019, the Indian government announced that it was formally ending the "special status" of its Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) state, the two-thirds of Kashmir under New Delhi's control, specifically by abrogating certain provisions of the Indian Constitution that granted the state autonomy with regard to most internal administrative issues. The legal changes went into effect on November 1, 2019, when New Delhi also bifurcated the state into two "union territories," each with lesser indigenous administrative powers than Indian states. Indian officials explain the moves as matters of internal domestic politics, taken for the purpose of properly integrating J&K and facilitating its economic development.

The process by which India's government has undertaken the effort has come under strident criticism for its alleged reliance on repressive force in J&K and for questionable legal and constitutional arguments that are likely to come before India's Supreme Court. Internationally, the move sparked controversy as a "unilateral" Indian effort to alter the status of a territory that is considered disputed by neighboring Pakistan and China, as well as by the United Nations. New Delhi's heavy-handed security crackdown in the remote state also raised ongoing human rights concerns. To date, but for a brief January visit by the U.S. Ambassador to India, U.S. government officials and foreign journalists have not been permitted to visit the Kashmir Valley.

The long-standing U.S. position on Kashmir is that the territory's status should be settled through negotiations between India and Pakistan while taking into consideration the wishes of the Kashmiri people.1 Since 1972, India's government has generally shunned third-party involvement on Kashmir, while Pakistan's government has continued efforts to internationalize it, especially through U.N. Security Council (UNSC) actions. China, a close ally of Pakistan, is also a minor party to the dispute. There are international concerns about potential for increased civil unrest and violence in the Kashmir Valley, and the cascade effect this could have on regional stability. To date, the Trump Administration has limited its public statements to calls for maintaining peace and stability, and respecting human rights. The UNSC likewise calls for restraint by all parties; an "informal" August 16 UNSC meeting resulted in no ensuing official U.N. statement. Numerous Members of the U.S. Congress have expressed concern about reported human rights abuses in Kashmir and about the potential for further international conflict between India and Pakistan.

New Delhi's August moves enraged Pakistan's leaders, who openly warned of further escalation between South Asia's two nuclear-armed powers, which nearly came to war after a February 2019 suicide bombing in the Kashmir Valley and retaliatory Indian airstrikes. The actions may also have implications for democracy and human rights in India; many analysts argue these have been undermined both in recent years and through Article 370's repeal. Moreover, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—empowered by a strong electoral mandate in May and increasingly pursuing Hindu majoritarian policies—may be undermining the country's secular, pluralist traditions. The United States seeks to balance pursuit of broader U.S.-India partnership while upholding human rights protections and maintaining cooperative relations with Pakistan.2

Recent Developments

Status and Impact of India's Crackdown

As of early January 2020, five months after the crackdown in J&K began, most internet service and roughly half of mobile phone users in the densely-populated Kashmir Valley remain blocked; and hundreds of Kashmiris remain in detention, including key political figures. According to India's Home Ministry, as of December 3, more than 5,100 people had been taken into "preventive custody" in J&K after August 4, of whom 609 remained in "preventive detention," including 218 alleged "stone-pelters" who assaulted police in street protests.3 New Delhi justifies ongoing restrictions as necessary in a fraught security environment.4 The U.S. government has long acknowledged a general threat; as stated by the lead U.S. diplomat for the region, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia Alice Wells, in October, "There are terrorist groups who operate in Kashmir and who try to take advantage of political and social disaffection."5

In early December, the Indian Home Ministry informed Parliament that incidents of "terrorist violence" in J&K during the 115 days following August 5 were down 17% from the 115 days preceding that date, from 106 to 88. However, the Ministry stated that attempts by militants to infiltrate into the Valley across the Line of Control from Pakistan have increased, from 53 attempts in the 88 days preceding August 5 to 84 in the 88 days following (in contrast, in October 2019, Wells stated before a House panel that, "I think we've observed a decline in infiltrations across the Line of Control").6

Senior Indian officials say their key goal is to avoid violence and bloodshed, arguing that "lots of the reports about shortages are fictitious" and that, "Some of our detractors are spreading false rumors, including through the U.S. media and it is malicious in nature."7 Indian authorities continue to insist that, with regard to street protests, "There has been no incident of major violence. Not even a single live bullet has been fired. There has been no loss of life in police action" (however, at least one teenaged protester's death reportedly was caused by shotgun pellets and a tear gas canister8). They add, however, that "terrorists and their proxies are trying to create an atmosphere of fear and intimidation in Kashmir." Because of this, "Some remaining restrictions on the communications and preventive detentions remain with a view to maintain public law and order."9

A September New York Times report described a "punishing blockade" ongoing in the Kashmir Valley, with sporadic protests breaking out, and dozens of demonstrators suffering serious injuries from shotgun pellets and tear gas canisters, leaving Kashmiris "feeling unsettled, demoralized, and furious."10 An October Press Trust of India report found some signs of normalcy returning, but said government efforts to reopen schools had failed, with parents and students choosing to stay away, main markets remaining shuttered, and mobile phone service remaining suspended in most of the Valley, where there continued to be extremely limited internet service.11

Since mid-October, the New Delhi and J&K governments have claimed that availability of "essential supplies," including medicines and cooking gas, is being ensured; that all hospitals, medical facilities, schools, banks, and ATMs are functioning normally; that there are no restrictions on movement by auto, rail, or air; and that there are no restrictions on the Indian media or journalists (foreign officials and foreign journalists continue to be denied access). On October 9, curtailment of tourism in the region was withdrawn. On October 14, the government lifted restrictions on post-paid mobile telephone service, while pre-paid service, aka via "burner phones," along with internet and messaging services, remains widely blocked.12 Public schools have reopened, but parents generally have not wanted their children out in a still-unstable setting.13 According to Indian authorities, "terrorists are also preventing the normal functioning of schools."14

On November 1, citizens of the former J&K state awoke to a new status as residents of either the Jammu and Kashmir Union Territory (UT) or the Union Territory of Ladakh (the latter populated by less than 300,000 residents; see Figure 1). While the J&K UT will be able to elect its own legislature, all administrative districts are now controlled by India's federal government, and J&K no longer has its own constitution or flag. The chief executives of each new UT are lieutenant governors who report directly to India's Home Ministry. More than 100 federal laws are now applicable to J&K, including the Indian Penal Code, and more than 150 laws made by the former state legislature are being repealed, including long-standing prohibitions on leasing land to non-residents. The new J&K assembly will be unable to make any laws on policing or public order, thus ceding all security issues to New Delhi's purview.15

The U.S.-India "2+2" Summit and Other Recent Developments

On December 18, India's external affairs and defense ministers were in Washington, DC, for the second "2+2" summit meeting with their American counterparts, where "The two sides reaffirmed the growing strategic partnership between the United States and India, which is grounded in democratic values, shared strategic objectives, strong people-to-people ties, and a common commitment to the prosperity of their citizens."16 In the midst of the session, an unnamed senior State Department official met the press and was asked about the situation in J&K. She responded that the key U.S. government concern is "a return to economic and political normalcy there," saying, "[W]hat has concerned us about the actions in Kashmir are the prolonged detentions of political leaders as well as other residents of the valley, in addition to the restrictions that continue to exist on cell phone coverage and internet."17

While visiting Capitol Hill at the time of the summit, Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar "abruptly" withdrew from a scheduled meeting with senior House Members, reportedly because the House delegation was to include Representative Pramila Jayapal, the original sponsor of H.Res. 745, which urges the Indian government to "end the restrictions on communications and mass detentions in Jammu and Kashmir as swiftly as possible and preserve religious freedom for all residents" (see "The U.S. Congress, Hearings, and Relevant Legislation" section below). Some observers saw in Jaishankar's action a shortsighted expression of India's considerable sensitivity about the Kashmir issue and a missed opportunity to engage concerned U.S. officials.18

Two months earlier, in October, two notable developments took place in India. Local Block Development Council elections were held in J&K that month. With all major regional parties and the national opposition Congress Party boycotting the polls, Independents overwhelmed the BJP, winning 71% of the total 317 blocks to the BJP's 26%, including 85% in the Kashmir division. The results suggested widespread disenchantment with New Delhi's ruling party in J&K.19 Also in October, India allowed a delegation of European parliamentarians to visit the Kashmir Valley, the first such travel by foreign officials since July. The composition of the delegation and questions surrounding its funding and official or private status added to international critiques of India's recent Kashmir policies.20

On January 9, New Delhi allowed a U.S. official to visit J&K for the first time since August, when 15 ambassadors, including U.S. Ambassador Ken Juster, were given a two-day "guided tour" of the Srinagar area. EU envoys declined to participate, apparently because the visit did not include meetings with detained Kashmiri political leaders. An External Affairs Ministry spokesman said the objective of the visit was for the envoys to view government efforts to "normalize the situation" firsthand, but the orchestrated visit attracted criticism from opposition parties and it is unclear if international opprobrium will be reduced as a result.21

On January 10, India's Supreme Court issued a ruling that an open-ended internet shutdown (as exists in parts of J&K) was a violation of free speech and expression granted by the country's constitution, calling indefinite restrictions "impermissible." The court gave J&K authorities a one-week deadline to provide a detailed review all orders related to internet restrictions.22

Background

Setting

India's former J&K state was about the size of Utah and encompassed three culturally distinct regions: Kashmir, Jammu, and Ladakh (see Figure 1). More than half of the mostly mountainous area's nearly 13 million residents live in the fertile Kashmir Valley, a region slightly larger than Connecticut (7% of the former state's land area was home to 55% of its population). Srinagar, in the Valley, was the state's (and current UT's) summer capital and by far its largest city with some 1.3 million residents. Jammu city, the winter capital, has roughly half that population, and the Jammu district is home to more than 40% of the former state's residents. About a quarter-million people live in remote Ladakh, abutting China. Just under 1% of India's total population lives in the former state of J&K.

|

Figure 1. Late 2019 Map of the New J&K and Ladakh Union Territories |

|

|

Source: Adapted by CRS. Note: Limits shown do not reflect U.S. government policy on boundary representation or sovereignty. |

Roughly 80% of Indians are Hindu and about 14% are Muslim. At the time of India's 2011 national census, J&K's population was about 68% Muslim, 28% Hindu, 2% Sikh, and 1% Buddhist. At least 97% of the Kashmir Valley's residents are Muslim; the vast majority of the district's Hindus fled the region after 1989 (see "Human Rights and India's International Reputation" below). The Jammu district is about two-thirds Hindu, with the remainder mostly Muslim. Ladakh's population is about evenly split between Buddhists and Muslims.23 Upon the 1947 partition of British India based on religion, the princely state of J&K's population had unique status: a Muslim majority ruled by a Hindu king. Many historians find pluralist values in pre-1947 Kashmir, with a general tolerance of multiple religions.24 The state's economy had been agriculture-based; horticulture and floriculture account for the bulk of income. Historically, the region's natural beauty made tourism a major aspect of commerce—this sector was devastated by decades of conflict, but had seemed to be making a comeback in recent years. Kashmir's remoteness has been a major impediment to transportation and communication networks, and thus to overall development. In mid-2019, India's Ambassador to the United States claimed that India's central government has provided about $40 billion to the former J&K state since 2004.25

J&K's Status, Article 370, and India-Pakistan Conflict

Accession to India

Since Britain's 1947 withdrawal and the partition and independence of India and Pakistan, the final status of the princely state of J&K has remained unsettled, especially because Pakistan rejected the process through which J&K's then-ruler had acceded to India. A dyadic war over Kashmiri sovereignty ended in 1949 with a U.N.-brokered cease-fire that left the two countries separated by a 460-mile-long military "Line of Control" (LOC). The Indian-administered side became the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The Pakistani-administered side became Azad ["Free"] Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) and the "Northern Areas," later called Gilgit-Baltistan.26

Article 370 and Article 35A of the Indian Constitution, and J&K Integration

In 1949, J&K's interim government and India's Constituent Assembly negotiated "special status" for the new state, leading to Article 370 of the Indian Constitution in 1950, the same year the document went into effect. The Article formalized the terms of Jammu and Kashmir's accession to the Indian Union, generally requiring the concurrence of the state government before the central government could make administrative changes beyond the areas of defense, foreign affairs, and communications. A 1954 Presidential Order empowered the state government to regulate the rights of permanent residents, and these became defined in Article 35A of the Constitution's Appendix, which prohibited nonresidents from working, attending college, or owning property in the state, among other provisions.27

Within a decade of India's independence, however, most national constitutional provisions were extended to the J&K state via Presidential Order with the concurrence of the J&K assembly (and with the Indian Supreme Court's assent). The state assembly arguably had over decades become pliant to New Delhi's influence, and critical observers contend that J&K's special status has long been hollowed out: while Article 370 provided special status constitutionally, the state suffered from inferior status politically through what amounted to "constitutional abuse."28 Repeal of Article 370 became among the leading policy goals of the BJP and its Hindu nationalist antecedents on the principle of national unity.29

Further India-Pakistan Wars

The J&K state's legal integration into India progressed and prospects for a U.N.-recommended plebiscite on its final status correspondingly faded in the 1950s and 1960s. Three more India-Pakistan wars—in 1965, 1971, and 1999; two of which were fought over Kashmir itself—left territorial control largely unchanged, although a brief 1962 India-China war ended with the high-altitude and sparsely populated desert region of Ladakh's Aksai Chin under Chinese control, making China a third, if lesser, party to the Kashmir dispute.30

In 1965, Pakistan infiltrated troops into Indian-held Kashmir in an apparent effort to incite a local separatist uprising; India responded with a full-scale military operation against Pakistan. A furious, 17-day war caused more than 6,000 battle deaths and ended with Pakistan failing to alter the regional status quo. The 1971 war saw Pakistan lose more than half of its population and much territory when East Pakistan became independent Bangladesh, the mere existence of which undermined Pakistan's professed status as a homeland for the Muslims of Asia's Subcontinent. In summer 1999, one year after India and Pakistan tested nuclear weapons, Pakistani troops again infiltrated J&K state, this time to seize strategic high ground near Kargil. Indian ground and air forces ejected the Pakistanis after three months of combat and 1,000 or more battle deaths.

Third-Party Involvement

In 1947, Pakistan had immediately and formally disputed the accession process by which J&K had joined India at the United Nations. New Delhi also initially welcomed U.N. mediation. Over ensuing decades, the U.N. Security Council issued a total of 18 Resolutions (UNSCRs) relevant to the Kashmir dispute. The third and central one, UNSCR 47 of April 1948, recommended a three-step process for restoring peace and order, and "to create proper conditions for a free and impartial plebiscite" in the state, but the conditions were never met and no referendum was held.31

Sporadic attempts by the United States to intercede in Kashmir have been unsuccessful. A short-lived mediation effort by the United States and Britain included six rounds of talks in 1961 and 1962, but ended when India indicated that it would not relinquish control of the Kashmir Valley.32 Although President Bill Clinton's personal diplomatic engagement was credited with averting a wider war and potential nuclear exchange in 1999, Kashmir's disputed status went unchanged.33 After 2001, some analysts argued that resolution of the Kashmir issue would improve the prospects for U.S. success in Afghanistan—a perspective championed by the Pakistani government—yet U.S. Presidents ultimately were dissuaded from making this argument an overt aspect of U.S. policy.34

In more recent decades, India generally has demurred from mediation in Kashmir out of (1) a combination of suspicion about the motives of foreign powers and the international organizations they influence; (2) India's self-image as a regional leader in no need of assistance; and (3) an underlying assumption that mediation tends to empower the weaker and revisionist party (in this case, Pakistan). According to New Delhi, prospects for third-party mediation were fully precluded by the 1972 Shimla Agreement, in which India and Pakistan "resolved to settle their differences by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations or by any other peaceful means mutually agreed upon between them." The 1999 Lahore Declaration reaffirmed the bilateral nature of the issue.35

Separatist Conflict and President's Rule From 2018

Three Decades of Separatist Conflict

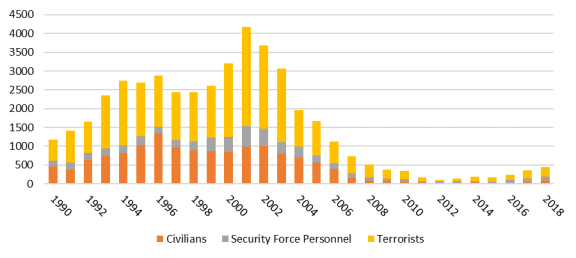

A widespread perception that J&K's 1987 state elections were illicitly manipulated to favor the central government led to pervasive disaffection among residents of the Kashmir Valley and the outbreak of an Islamist-based separatist insurgency in 1989. The decades-long conflict has pitted the Indian government against Kashmiri militants who seek independence or Kashmir's merger with neighboring Pakistan, a country widely believed to have provided arms, training, and safe haven to militants over the decades. Violence peaked in the 1990s and early 2000s, mainly affecting the Valley and the LOC (see Figure 2). Lethal exchanges of small arms and mortar fire at the LOC remain common, killing soldiers and civilians alike, despite a formal cease-fire agreement in place since 2003. The Indian government says the conflict has killed at least 42,000 civilians, militants, and security personnel since 1989; independent analyses count 70,000 or more related deaths. India maintains a security presence of at least 500,000 army and paramilitary soldiers in the former J&K state.36

A bilateral India-Pakistan peace plan for Kashmir was nearly finalized in 2007, when Indian and Pakistani negotiators had agreed to make the LOC a "soft border" with free movement and trade across it; prospects faded due largely to unrelated Pakistani domestic issues.37

|

|

Sources: Indian Home Ministry and South Asia Terrorism Portal (New Delhi) data. |

India has blamed conventionally weaker Pakistan for perpetuating the conflict as part of an effort to "bleed India with a thousand cuts."38 Pakistan denies materially supporting Kashmiri militants and has sought to highlight Indian human rights abuses in the Kashmir Valley. Separatist militants have commonly targeted civilians, leading India and most Indians (as well as independent analysts) to label them as terrorists and thus decry Pakistan as a "terrorist-supporting state." The U.S. government issues ongoing criticisms of Islamabad for taking insufficient action to neutralize anti-India terrorists groups operating on and from Pakistani soil.39

Still, many analysts argue that blanket characterizations of the Kashmir conflict as an externally-fomented terrorist effort obscure the legitimate grievances of the indigenous Muslim-majority populace, while (often implicitly) endorsing a "harsh counterinsurgency strategy" that, they contend, has only further alienated successive generations in the Valley.40 For these observers, Kashmir's turmoil is, at its roots, a clash between the Indian government and the Kashmiri people, leading some to decry New Delhi's claims that Pakistan perpetuates the conflict.41 Today, pro-independence political parties on both sides of the LOC are given little room to operate, and many Kashmiris have become deeply alienated. Critics of the Modi government's Hindu nationalist agenda argue that its policies entail bringing the patriotism of Indian Muslims into question and portraying Pakistan as a relentless threat that manipulates willing Kashmiri separatists, and so is responsible for violence in Kashmir.42

Arguments locating the conflict's cause in the interplay between Kashmir and New Delhi are firmly rejected by Indian officials and many Indian analysts who contend that there is no "freedom struggle" in Kashmir, rather a war "foisted" on India by a neighbor (Pakistan) that will maintain perpetual animosity toward India.43 In this view, talking to Pakistan cannot resolve the situation, nor can negotiations with Kashmiri separatist groups and parties, which are seen to represent Pakistan's interests rather than those of the Kashmiri people.44

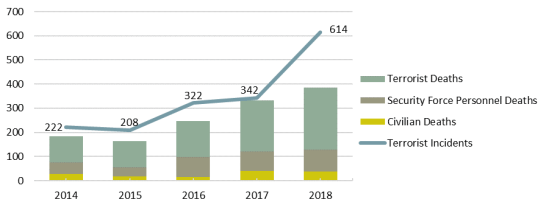

Even before 2019 indications were mounting that Kashmiri militancy was on the rise for the first time in nearly two decades. Figure 3 shows that, in the first five years after Modi took office, the number of "terrorist incidents" and conflict-related deaths was on the rise. Mass street protests in the valley were sparked by the 2016 killing of a young militant commander in a shootout with security forces.45 Existing data on rates of separatist violence indicate that levels in 2019 decreased over the previous year, perhaps in large part due to the post-July security crackdown.46

|

Figure 3. Terrorist Incidents and Deaths from Separatist Conflict in J&K, 2014-2018 |

|

|

Sources: Indian Home Ministry and South Asia Terrorism Portal (New Delhi) data. |

2018 J&K Assembly Dissolution and President's Rule

J&K's lack of a state assembly in early 2019 appears to have facilitated New Delhi's constitutional changes. In June 2018, the J&K state government formed in 2015—a coalition of the BJP and the Kashmir-based Peoples Democratic Party—collapsed after the BJP withdrew its support, triggering direct federal control through the center-appointed governor. BJP officials called the coalition untenable due to differences over the use of force to address a deteriorating security situation (the BJP sought greater use of force).47 In December 2018, J&K came under "President's Rule" for the first time since 1996, with the state legislature's power under Parliament's authority.48

Developments in 2019

The February Pulwama Crisis

On February 14, 2019, an explosives-laden SUV rammed into a convoy carrying paramilitary police in the Kashmir Valley city of Pulwama. At least 40 personnel were killed in the explosion. The suicide attacker was said to be a member of Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), a Pakistan-based, U.S.-designated terrorist group that claimed responsibility for the bombing. On February 26, Indian jets reportedly bombed a JeM facility in Balakot, Pakistan, the first such Indian attack on Pakistan proper since 1971 (see Figure 4). Pakistan launched its own air strike in response, and aerial combat led to the downing of an Indian jet. When Pakistan repatriated the captured Indian pilot on March 1, 2019, the crisis subsided, but tensions have remained high. The episode fueled new fears of war between South Asia's two nuclear-armed powers and put a damper on prospects for renewed dialogue between New Delhi and Islamabad, or between New Delhi and J&K.

A White House statement on the day of the Pulwama bombing called on Pakistan to "end immediately the support and safe haven provided to all terrorist groups operating on its soil" and indicated that the incident "only strengthens our resolve" to bolster U.S.-India counterterrorism cooperation. Numerous Members of Congress expressed condemnation and condolences on social media.49 However, during the crisis, the Trump Administration was seen by some as unhelpfully absent diplomatically, described by one former senior U.S. official as "mostly a bystander" to the most serious South Asia crisis in decades, demonstrating "a lack of focus" and diminished capacity due to vacancies in key State Department positions.50

|

|

Source: Adapted by CRS. Note: Limits shown do not reflect U.S. government policy on boundary representation or sovereignty. |

President Trump's July "Mediation" Offer

In July 2019, while taking questions from the press alongside visiting Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan, President Trump claimed that Indian Prime Minister Modi had earlier in the month asked the United States to play a mediator role in the Kashmir dispute.51 As noted above, such a request would represent a dramatic policy reversal for India. The U.S. President's statement provoked an uproar in India's Parliament, with opposition members staging a walkout and demanding explanation. Quickly following Trump's claim, Indian External Affairs Minister Jaishankar assured parliamentarians that no such request had been made, and he reiterated India's position that "all outstanding issues with Pakistan are discussed only bilaterally" and that future engagement with Islamabad "would require an end to cross border terrorism."52

In an apparent effort to reduce confusion, a same-day social media post from the State Department clarified the U.S. position that "Kashmir is a bilateral issue for both parties to discuss" and the Trump Administration "stands ready to assist."53 A release from the Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Representative Engel, reiterated support for "the long-standing U.S. position" on Kashmir, affirmed that the pace and scope of India-Pakistan dialogue is a bilateral determination, and called on Pakistan to facilitate such dialogue by taking "concrete and irreversible steps to dismantle the terrorist infrastructure on Pakistan's soil."54 An August 2 meeting of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Jaishankar in Thailand saw the Indian official directly convey to his American counterpart that any discussion on Kashmir, "if at all warranted," would be strictly between India and Pakistan.55

President Trump's seemingly warm reception of Pakistan's leader, his desire that Pakistan help the United States "extricate itself" from Afghanistan, and recent U.S. support for an International Monetary Fund bailout of Pakistan elicited disquiet among many Indian analysts. They said Washington was again conceptually linking India and Pakistan, "wooing" the latter in ways that harm the former's interests. Trump's Kashmir mediation claims were especially jarring for many Indian observers, some of whom began questioning the wisdom of Modi's confidence in the United States as a partner. The episode may have contributed to India's August moves.56

August Abrogation of Article 370 and J&K Reorganization

In late July and during the first days of August, India moved an additional 45,000 troops into the Kashmir region in apparent preparation for announcing Article 370's repeal. On August 2, the J&K government of New Delhi-appointed governor Satya Pal Malik issued an unprecedented order cancelling a major annual religious pilgrimage in the state and requiring tourists to leave the region, purportedly due to intelligence inputs of terror threats. The developments reportedly elicited panic among those Kashmiris fearful that their state's constitutional protections would be removed. Two days later, the state's senior political leaders—including former chief ministers Omar Abdullah (2009-2015) and Mehbooba Mufti (2016-2018)—were placed under house arrest, schools were closed, and all telecommunications, including internet and landline telephone service, were curtailed. Internet shutdowns are common in Kashmir—one press report said there had been 52 earlier in 2019 alone—but this appears to have been the first-ever shutdown of landline phones there.57 Pakistan's government denounced these actions as "destabilizing."58

On August 5, with J&K state in "lockdown," Indian Home Minister Amit Shah introduced in Parliament legislation to abrogate Article 370 and reorganize the J&K state by bifurcating it into two Union Territories, Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh, with only the former having a legislative assembly. In a floor speech, Shah called Article 370 "discriminatory on the basis of gender, class, caste, and place or origin," and contended that its repeal would spark investment and job creation in J&K.59 On August 6, after the key legislation had passed both of Parliament's chambers by large majorities and with limited debate, Prime Minister Modi lauded the legislation, declaring, "J&K is now free from their shackles," and predicting that the changes "will ensure integration and empowerment."60 All of his party's National Democratic Alliance coalition partners supported the legislation, as did many opposition parties (the main opposition Congress Party was opposed).61 The move also appears to have been popular among the Indian public, possibly in part due to a post-Pulwama, post-election wave of nationalism that has been amplified by the country's mainstream media.62 Proponents view the move as a long-overdue, "master stroke" righting of a historic wrong that left J&K underdeveloped and contributed to conflict there.63

Notwithstanding Indian authorities' claims that J&K's special status hobbled its economic and social development, numerous indicators show that the former state was far from the poorest rankings in this regard. For example, in FY2014-FY2015, J&K's per capita income was about Rs63,000 (roughly $882 in current U.S. dollars), higher than seven other states, and more than double that of Bihar and 50% above Uttar Pradesh.64 While the state's economy typically grew at the slowest annual rates among all Indian states in the current decade, its FY2017-FY2018 expansion of 6.8% was greater than that of eight states and only moderately lagged the national expansion of 7.2% that year.65 According to 2011 census data, J&K's literacy rate of nearly 69% ranked it higher than five Indian states, including Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan.66 At 73.5 years, J&K ranked 3rd of 22 states in life expectancy, nearly five years longer than the national average of 68.7. The state also ranked 8th in poverty rate and 10th in infant mortality.67

The year 2019 saw negative economic news for India and increasing criticism of the government on these grounds, leading some analysts to suspect that Modi and his lieutenants were eager to play to the BJP's Hindu nationalist base and shift the national conversation.68 In addition, some analysts allege that President Trump's relevant July comments may have convinced Indian officials that a window of opportunity in Kashmir might soon close, and that they could deprive Pakistan of the "negotiating ploy" of seeking U.S. pressure on India as a price for Pakistan's cooperation with Afghanistan.69

Responses and Concerns

International Reaction

The Trump Administration

Indian press reports claimed that External Affairs Minister Jaishankar had "sensitized" Secretary of State Pompeo to the coming Kashmir moves at an in-person meeting on August 2 so that Washington would not be taken by surprise. However, a social media post from the State Department's relevant bureau asserted that New Delhi "did not consult or inform the U.S. government" before moving to revoke J&K's special status.70

On August 5, a State Department spokeswoman said about developments in Kashmir, "We are concerned about reports of detentions and urge respect for individual rights and discussion with those in affected communities. We call on all parties to maintain peace and stability along the Line of Control."71 Three days later, she addressed the issue more substantively, saying,

We want to maintain peace and stability, and we, of course, support direct dialogue between India and Pakistan on Kashmir and other issues of concern.... [W]henever it comes to any region in the world where there are tensions, we ask for people to observe the rule of law, respect for human rights, respect for international norms. We ask people to maintain peace and security and direct dialogue.

The spokeswoman also flatly denied any change in U.S. policy.72 The Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee and Ranking Member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee also responded in a joint August 7 statement expressing hope that New Delhi would abide by democratic and human rights principles and calling on Islamabad to refrain from retaliating while taking action against terrorism.73

The government's heavy-handed security measures in J&K elicited newly intense criticisms of India on human rights grounds.74 In late September, Ambassador Wells said,

The United States is concerned by widespread detentions, including those of politicians and business leaders, and the restrictions on the residents of Jammu and Kashmir. We look forward to the Indian Government's resumption of political engagement with local leaders and the scheduling of the promised elections at the earliest opportunity.75

During an October 22 House Foreign Affairs subcommittee hearing on human rights in South Asia, Ambassador Wells testified that, "the Department [of State] has closely monitored the situation" in Kashmir and, "We deeply appreciate the concerns expressed by many Members about the situation" there. She reviewed ongoing concerns about a lack of normalcy in the Valley, especially, citing continued detentions and "security restrictions," including those on communication, and calling on Indian authorities to restore everyday services "as swiftly as possible." Wells also welcomed Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan's recent statements abjuring external support for Kashmiri militancy:

We believe the foundation for any successful dialogue between India and Pakistan is based on Pakistan taking sustained and irreversible steps against militants and terrorists on its territory.… We believe that direct dialogue between India and Pakistan, as outlined in the 1972 Shimla Agreement, holds the most potential for reducing tensions.76

Some Indian observers saw the hearing as a public relations loss for India, with one opining that "India got a drubbing and Pakistan got away scot-free."77 However, for some analysts, the Trump Administration's broad embrace of Modi and its relatively mild criticisms on Kashmir embolden illiberal forces in India.78

The U.S. Congress, Hearings, and Relevant Legislation

In August and September, numerous of Members of Congress went on record in support of Kashmiri human rights.79 During October travel to India, Senator Chris Van Hollen was denied permission to visit J&K. Days later, Senator Mark Warner, a cochair of the Senate India Caucus, tweeted, "While I understand India has legitimate security concerns, I am disturbed by its restrictions on communications and movement in Jammu and Kashmir."80

In October, the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific, and Nonproliferation held a hearing on human rights in South Asia, where discussion was dominated by the Kashmir issue. In attendance was full committee Chairman Representative Engel, who opined that, "The Trump administration is giving a free pass when countries violate human rights or democratic norms. We saw this sentiment reflected in the State Department's public statements in response to India's revocation of Article 370 of its constitution." Then-Subcommittee Chairman Representative Brad Sherman said, "I regard [Kashmir] as the most dangerous geopolitical flash-point in the world. It is, after all, the only geopolitical flash-point that has involved wars between two nuclear powers." Also during the hearing, one Administration witness, Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor Robert Destro, affirmed that the situation in Kashmir was "a humanitarian crisis."81

Congress's Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission held a mid-November hearing entitled "Jammu and Kashmir in Context," during which numerous House Members reiterated concerns about reports of ongoing human rights violations in the Kashmir Valley. Among the seven witnesses was U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) Commissioner Anurima Bhargava, who discussed restrictions of religious freedom in India, and noted that USCIRF researchers have been barred from visiting India since 2004.82

In S.Rept. 116-126 of September 26, 2019, accompanying the then-pending State and Foreign Operations Appropriations bill for FY2020 (S. 2583), the Senate Appropriations Committee noted with concern the current humanitarian crisis in Kashmir and called on the government of India to (1) fully restore telecommunications and Internet services; (2) lift its lockdown and curfew; and (3) release individuals detained pursuant to the Indian government's revocation of Article 370 of the Indian constitution.

H.Res. 724, introduced on November 21, 2019, would condemn "the human rights violations taking place in Jammu and Kashmir" and support "Kashmiri self-determination."

H.Res. 745, introduced on December 6, 2019, and currently with 40 cosponsors, would recognize the security challenges faced by Indian authorities in Jammu and Kashmir, including from cross-border terrorism; reject arbitrary detention, use of excessive force against civilians, and suppression of peaceful expression of dissent as proportional responses to security challenges; urge the Indian government to ensure that any actions taken in pursuit of legitimate security priorities respect the human rights of all people and adhere to international human rights law; and urge that government to lift remaining restrictions on telecommunications and internet, release all persons "arbitrarily detained," and allow international human rights observers and journalists to access Jammu and Kashmir, among other provisions.

Pakistan

Islamabad issued a "strong demarche" in response to New Delhi's moves, deeming them "illegal actions ... in breach of international law and several UN Security Council resolutions." Pakistan downgraded diplomatic ties, halted trade with India, and suspended cross-border transport services.83 Pakistan's prime minister warned that, "With an approach of this nature, incidents like Pulwama are bound to happen again" and he later penned an op-ed in which he warned, "If the world does nothing to stop the Indian assault on Kashmir and its people, there will be consequences for the whole world as two nuclear-armed states get ever closer to a direct military confrontation."84 Pakistan appeared diplomatically isolated in August, with Turkey being the only country to offer solid and explicit support for Islamabad's position.85 Pakistan called for a UNSC session and, with China's support, the Council met on August 16 to discuss Kashmir for the first time in more than five decades, albeit in a closed-door session that produced no formal statement. Pakistani officials also suggested that Afghanistan's peace process could be negatively affected.86

Many analysts view Islamabad as having little credibility on Kashmir, given its long history of covertly supporting militant groups there. Pakistan's leadership has limited options to respond to India's actions, and renewed Pakistani support for Kashmiri militancy likely would be costly internationally. Pakistan's ability to alter the status quo through military action has been reduced in recent years, meaning that Islamabad likely must rely primarily on diplomacy.87 Given also that Pakistan and its primary ally, China, enjoy limited international credibility on human rights issues, Islamabad may stand by and hope that self-inflicted damage caused by New Delhi's own policies in Kashmir and, more recently, on citizenship laws, will harm India's reputation and perhaps undercut its recent diplomatic gains with Arab states such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE.88 In late 2019, Pakistan accused India of taking escalatory steps in the LOC region, including by deploying medium-range Brahmos cruise missiles there.89

China

Pakistan and China have enjoyed an "all-weather" friendship for decades. On August 6, China's foreign ministry expressed "serious concern" about India's actions in Kashmir, focusing especially on the "unacceptable" changed status for Ladakh, parts of which Beijing claims as Chinese territory (Aksai Chin). A Foreign Ministry spokesman called on India to "stop unilaterally changing the status quo" and urged India and Pakistan to exercise restraint. China's foreign minister reportedly vowed to "uphold justice for Pakistan on the international arena," and Beijing has supported Pakistan's efforts to bring the Kashmir issue before the U.N. Security Council. One editorial published in China's state-run media warned that India "will incur risks" for its "reckless and arrogant" actions.90

The United Nations

On August 8, the U.N. Secretary-General called for "maximum restraint" and expressed concern that restrictions in place on the Indian side of Kashmir "could exacerbate the human rights situation in the region." He reaffirmed that, "The position of the United Nations on this region is governed by the Charter ... and applicable Security Council resolutions."91 Beijing's support of Pakistan's request for U.N. involvement led to "informal and closed-door consultations" among UNSC members on August 16, a session that included the Russian government.92 No ensuing statement was issued, but Pakistan's U.N. Ambassador declared that the fact of the meeting itself demonstrated Kashmir's disputed status, while India's Ambassador held to New Delhi's view that Article 370's abrogation was a strictly internal matter. No UNSC member other than China spoke publicly about the August meeting, leading some to conclude the issue was not gaining traction.93 In mid-December, Beijing reportedly echoed Islamabad's request that the U.N. Security Council hold another closed-door meeting on Kashmir, but no such meeting has taken place.94

In a September speech to the U.N. Human Rights Council, High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet expressed being "deeply concerned" about the human rights situation in Kashmir.95 In October, a spokesman for the Council said, "We are extremely concerned that the population of Indian-administered Kashmir continues to be deprived of a wide range of human rights and we urge the Indian authorities to unlock the situation and fully restore the rights that are currently being denied."96

Other Responses

Numerous Members of the European Parliament have expressed human rights concerns and called on New Delhi to "restore the basic freedoms" of Kashmiris.97 During her early November visit to New Delhi, German Chancellor Angela Merkel opined, "The situation for the people there is currently not sustainable and must improve." Later that month, Sweden's foreign minister said, "We emphasize the importance of human rights" in Kashmir.98 The Saudi government agreed in late December to host an Organization of Islamic Cooperation "special foreign ministers meeting" on Kashmir sometime in early 2020.99

Human Rights and India's International Reputation

Democracy and Other Human Rights Concerns100

New Delhi's August 5 actions appear to have been broadly popular with the Indian public and, as noted above, were supported by most major Indian political parties. Yet the government's process came under criticism from many quarters for a lack of prior consultation and/or debate, and many legal scholars opined that the government had overstepped its constitutional authority, predicting that the Indian Supreme Court would become involved.101 New Delhi's perceived circumvention of the J&K state administration (by taking action with only the assent of the centrally appointed governor) is at the heart of questions about the constitutionality of the government's moves, which, in the words of one former government interlocutor to the state, represent "the total undermining of our democracy" that was "done by stealth."102 The Modi government's argument appears to be that, since the J&K assembly was dissolved and the state had been under central rule since 2018, the national parliament could exercise the prerogative of the assembly, a position rejected as specious by observers who see the government's actions as a "constitutional coup."103

Many Indian (and international) critics of the government's moves see them not only as undemocratic in process, but also as direct attacks on India's secular identity. From this perspective, the BJP's motive is about advancing the party's "deeply rooted ideals of Hindu majoritarianism" and Modi's assumed project "to reinvent India as an India that is Hindu."104 One month before the government's August 5 bill submission, a senior BJP official said his party is committed to bringing back the estimated 200,000-300,000 Hindus who fled the Kashmir Valley after 1989 (known as Pandits). This reportedly could include reviving a plan for construction of "segregated enclaves" with their own schools, shopping malls, and hospitals, an approach with little or no support from local figures or groups representing the Pandits. Beyond the Pandit-return issue, New Delhi's revocation of the state's restrictions on residency and rhetorical emphasis on bringing investment and economic development to the Kashmir Valley lead some analysts to see "colonialist" parallels with Israel's activities in the West Bank.105

Perceived human rights abuses on both sides of the Kashmir LOC, some of them serious, have long been of concern to international governments and organizations. A major and unprecedented 2018 Report on the Situation on Human Rights in Kashmir from the U.N. Human Rights Commission harshly criticized the New Delhi government for alleged excessive use of force and other human rights abuses in the J&K state.106 With New Delhi's sweeping security crackdown in Kashmir continuing to date, the Modi government faces renewed criticisms for widely alleged abuses.107 Indian officials have also come under fire for the use of torture in Kashmir and for acting under broad and vaguely worded laws that facilitate abuses.108 The Indian government reportedly is in contravention of several of its U.N. commitments, including a 2011 agreement to allow all special rapporteurs to visit India. In spring 2019, after a U.N. Human Right Council's letter to New Delhi asking about steps taken to address abuses alleged in the 2018 report, Indian officials announced they would no longer engage U.N. "mandate holders."109

India appears to be the world leader in internet shutdowns by far, having blocked the network 134 times in 2018, compared to 12 shutdowns by Pakistan, the number two country in this category.110 Internet blockages are common in Kashmir, but rarely last more than a few days; at more than five months to date, the outage in the Valley is the longest ever.111 A group of U.N. Special Rapporteurs called the blackout "a form of collective punishment" that is "inconsistent with the fundamental norms of necessity and proportionality."112 Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International both contend that the communications blackout violates international law.113 As noted above, in early January 2020, India's Supreme Court seemed to agree, ruling that an indefinite suspension is "impermissible."114 Kashmiris have begun automatically losing their accounts on the popular WhatsApp platform due to 120 days of inactivity and, by mid-December, the internet shutdown had become the longest ever imposed in a democracy, according to Access Now, an advocacy group.115 Businesses have been especially hard hit: the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce estimated more than Rs178 billion (about $2.5 billion) in losses over four months.116

Potential Damage to India's International Image

Late 2019 saw a spate of commentary in both the Indian and American press about the likelihood that New Delhi's moves on Kashmir, when combined with the national government's broader pursuit of sometimes controversial Hindu nationalist policies, would contribute to a tarnishing of India's reputation as a secular, pluralist democratic society. In December, Parliament passed a Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) that adds a religious criterion to the country's naturalization process and triggered widespread and sometimes violent public protests.117 The Modi/BJP expenditure of political capital on social issues is seen by many analysts as likely to both intensify domestic instability and decrease the space in which to reform the economy, a combination that could be harmful to India's international reputation.118

Former Indian National Security Adviser and Foreign Secretary Shivshankar Menon told a public forum in New Delhi that the BJP's 2019 actions in Kashmir and changes to citizenship laws have caused self-inflicted damage to the country's international image. In the words of one scholar who agrees, "India's moral standing has taken a hit," and, "Even India's partners are questioning its credentials as a multicultural, pluralist society."119 One op-ed published in a major Indian daily warned that "the sense of creeping Hindu majoritarianism has begun to generate concern among a range of groups from the liberal international media, the U.S. Congress, to the Islamic world." The article contended that "India will need some course-correction in the new year to prevent the crystallization of serious external challenges."120 Another long-time observer argued that New Delhi's claims that "domestic" issues should be of no concern to an external audience are not credible: "It's hard to deny that 2019 was the year when Modi's domestic adventures robbed the bank of goodwill accumulated over time.… India's image took a beating this year."121

Support for India's rise as a major regional player and U.S. partner has been among the few subjects of bipartisan consensus in Washington, DC, in the 21st century, and some analysts contend that the New Delhi government may be putting that consensus to the test by "sliding into majoritarianism and repression."122 These analysts express concern that an existing consensus in favor of robust and largely uncritical support for India may be eroding, with signs that some Democratic lawmakers, in particular, have been angered by India's domestic policies.123 According to one Indian pundit, "[E]ven the mere introduction by House Democrats of two House resolutions on Kashmir bears the ominous signs of India increasingly becoming a partisan issue in the American foreign policy consensus."124

U.S. Policy and Issues for Congress

A key goal of U.S. policy in South Asia has been to prevent India-Pakistan conflict from escalating to interstate war. This means the United States has sought to avoid actions that overtly favored either party. Over the past decade, however, Washington appears to have grown closer to India while relations with Pakistan appear to continue to be viewed as clouded by mistrust. The Trump Administration "suspended" security assistance to Pakistan in 2018 and has significantly reduced nonmilitary aid while simultaneously deepening ties with New Delhi. The Administration views India as a key "anchor" of its "free and open Indo-Pacific" strategy, which some argue is aimed at China.125 Yet any U.S. impulse to "tilt" toward India is to some extent offset by Islamabad's current, and by most accounts vital, role in facilitating Afghan reconciliation negotiations. President Trump's apparent bonhomie with Pakistan's prime minister and offer to mediate on Kashmir in July was taken by some as a new and potentially unwise strategic shift.126

The U.S. government has maintained a focus on the potential for conflict over Kashmir to destabilize South Asia.127 At present, the United States has no congressionally-confirmed Assistant Secretary of State leading the Bureau of South and Central Asia and no Ambassador in Pakistan, leading some experts to worry that the Trump Administration's preparedness for India-Pakistan crises remains thin.128 Developments in August 2019 and after also renewed concerns among some analysts that the Trump Administration's "hands-off" posture toward this and other international crises erodes American power and increases the risk of regional turbulence.129 Some commentary, however, was more approving of U.S. posturing.

Developments in Kashmir in 2019 raise possible questions for Congress:

- Have India's actions changing the status of its J&K state negatively affect regional stability? If so, what leverage does the United States have and what U.S. policies might best address potential instability?

- Is there any diplomatic or other role for the U.S. government to play in managing India-Pakistan conflict or facilitating a renewal of their bilateral dialogue?

- To what extent does increased instability in Kashmir influence dynamics in Afghanistan? Will Islamabad's cooperation with Washington on Afghan reconciliation be reduced?

- To what extent, if any, are India's democratic/constitutional norms and pluralist traditions at risk in the country's current political climate? Are human rights abuses and threats to religious freedom increasing there? If so, should the U.S. government take any further actions to address such concerns?

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

See a July 22, 2019, State Department tweet at https://twitter.com/state_sca/status/1153444051368239104?lang=en. |

| 2. |

See also CRS Report R45807, India's 2019 National Election and Implications for U.S. Interests, by K. Alan Kronstadt, and CRS In Focus IF10298, India's Domestic Political Setting, by K. Alan Kronstadt.

|

| 3. |

See the December 3, 2019, Home Ministry release at https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1594853. |

| 4. |

Junior Home Minister G. Kishan Reddy in early December: "In view of the aggressive anti-India social media posts being pushed from across the border aiming at instigating youth of the Valley and glamorizing terrorists and terrorism, certain restrictions on Internet have been resorted to" (quoted in "19 Civilians Killed in Valley Since Aug. 5, Says Minister," Hindu (Chennai), December 4, 2019). |

| 5. |

Quoted in "House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific and Nonproliferation Holds Hearing on Human Rights in South Asia," CQ Transcripts, October 22, 2019. |

| 6. |

"Terrorist Incidents in J&K Drop 17% Since Abrogation of Article 370," Times of India (Delhi), December 4, 2019; Wells quoted in "House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific and Nonproliferation Holds Hearing on Human Rights in South Asia," CQ Transcripts, October 22, 2019. The Home Ministry reports that, from August 5 through November 27, 17 civilians and 3 security force personnel were killed in "terror-related incidents," and 129 people injured. It also claims 950 cease-fire violations by Pakistani forces from August to October, an average of more than ten per day (see the November 27, 2019, Home Ministry release at https://tinyurl.com/tlshm2n, and the November 19, 2019, release at https://tinyurl.com/szqdrwu). |

| 7. |

External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar quoted in "Q and A: India's Foreign Minister on Kashmir" (interview), Politico, September 2, 2019; Indian Ambassador to the United States Harsh Vardhan Shringla quoted in "'False Rumors': Indian Ambassador Blasts Pakistan's 'Disinformation' on Kashmir Moves" (interview), Washington Times, September 5, 2019. |

| 8. |

"In Teenager's Death, a Battle Over the Truth in Kashmir," Washington Post, September 6, 2019. |

| 9. |

"Steps Taken by Jammu & Kashmir Administration Since 06 August to Normalize the Situation," and other Indian government documents provided to CRS by the Embassy of India, September-December 2019. |

| 10. |

"In Kashmir, Growing Anger and Misery," New York Times, September 30, 2019. |

| 11. |

"Massive Traffic Jams in Srinagar, Some Shops Open in Morning Hours," Press Trust India, October 3, 2019. |

| 12. |

According to one report, more than 60% of the Valley's more than 6 million mobile subscribers rely on prepaid phones ("Cell Service Returns to Kashmir, Allowing First Calls in Months," New York Times, October 14, 2019). |

| 13. |

The New York Times reported on October 31 that some 1.5 million Kashmiri children remained out of school ("Anxious and Cooped Up, 1.5 Million Kashmiri Children Are Still Out of School," New York Times, October 31, 2019). |

| 14. |

"Latest Updates from Jammu & Kashmir," undated fact sheet provided to CRS by the Embassy of India, December 31, 2019. |

| 15. |

"Indian-Administered Kashmir Broken Up: All You Need to Know," Al Jazeera (Doha), October 30, 2019; "India Downgrades Kashmir's Status and Takes Greater Control Over Contested Region," CNN.com, October 31, 2019. |

| 16. |

See the December 18, 2019, State Department release at https://go.usa.gov/xd3Gw, and the resulting December 19, 2019, Joint Statement at https://go.usa.gov/xd3GF. |

| 17. |

Se the December 18, 2019, State Department transcript at https://go.usa.gov/xd3Gd. |

| 18. |

"Top Indian Official Abruptly Cancels Meeting with Congressional Leaders Over Kashmir Issue," Washington Post, December 19, 2019; Manoj Joshi, "Was Jaishankar 'Myopic' in Not Meeting Jayapal?" (op-ed), Quint (Noida, online), December 19, 2019. |

| 19. |

"Independents Sweep J&K BDC Polls, BJP Comes Distant Second," Times of India (Delhi), October 25, 2019. |

| 20. |

According to press reports, 22 of the 27 European delegates were members of "far-right" and "anti-immigration" parties with "histories of anti-Muslim rhetoric" ("India Finally Lets Lawmakers into Kashmir: Far-Right Europeans," New York Times, October 29, 2019). |

| 21. |

See the Ministry's January 9, 2020, transcript at https://tinyurl.com/uoc6gyl; "India Takes Diplomats to Visit Indian Kashmir," VOA News, January 9, 2020. |

| 22. |

"India Top Court Orders Review of Longest Internet Shutdown," BBC News, January 10, 2020. |

| 23. |

See Indian census data at https://www.census2011.co.in/data/religion/state/1-jammu-and-kashmir.html and the J&K state portal at https://jk.gov.in/jammukashmir/?q=demographics. |

| 24. |

Aarti Tikoo Singh, "View: 'I Am No More an Outsider in Kashmir'" (op-ed), Economic Times (Mumbai), August 11, 2019; Toru Tak, "The Term 'Kashmiriyat': Kashmiri Nationalism of the 1970s," Economic & Political Weekly (New Delhi), April 20, 2013). |

| 25. |

See the J&K state portal at https://jk.gov.in/jammukashmir/?q=economy; "Bret Baier Talks Brewing Kashmir Conflict with Indian, Pakistani Ambassadors to US," Fox News, August 13, 2019. |

| 26. |

The Hindu leader of the Muslim-majority princely state, Maharaja Hari Singh, initially opted to remain independent. Within months, however, armed militants from Pakistan were threatening his capital city of Srinagar, and Singh sought military assistance from India. Such assistance was offered only with the signing of an "Instrument of Accession"—a legal document that made J&K part of the Indian Union. This was accomplished in October 1947, and airlifted Indian troops quickly came to the Maharaja's aid, eventually securing Srinagar in the fertile Kashmir Valley, along with about two-thirds of the territory that was his former domain. Under the Instrument, J&K's integration into India was not meant to be total; as a sovereign signatory, the Maharaja ensured provisions that would allow for his continued and partially autonomous rule (see http://jklaw.nic.in/instrument_of_accession_of_jammu_and_kashmir_state.pdf). |

| 27. |

Article 370 exempted J&K from most of the Indian Constitution and permitted the state to draft its own constitution and fly its own flag in lieu of the Indian "tri-color." Article 370 and Article 35A formed the basis of J&K's special, semiautonomous status within India (A.G. Noorani, Article 370: A Constitutional History of Jammu and Kashmir (Oxford University Press, 2011)). |

| 28. |

A.G. Noorani, "Article 370: Law and Politics," Frontline (Chennai) September 16, 2000. See also Faizan Mustafa, "Understanding Articles 370, 35A," Indian Express (Noida), March 5, 2019; Srinath Raghavan, "With Special Status Hollowed Out, J&K Consider Article 35A Last Vestige of Real Autonomy," Print (Delhi), July 30, 2019. |

| 29. |

The BJP's 2014 election manifesto reiterated the party's long-standing commitment to abrogation of Article 370 and annulment of Article 35A, along with an intention to "discuss this with all stakeholders." The 2019 version of the manifesto omitted this latter clause. The Congress Party's 2019 manifesto included a vow to allow no changes to J&K's constitutional status and promised to reduce the presence of security forces in the Kashmir Valley (see https://www.bjp.org/en/manifesto2019 and https://manifesto.inc.in/en/jammu_and_kashmir.html). |

| 30. |

Aksai Chin is a key portion of the "Western Sector" of much larger India-China border disputes. The region is larger than the state of Maryland but has about 10,000 residents. |

| 31. |

UNSCR 47 recommended that (1) Pakistan should withdraw all of its nationals and tribesmen who entered the state for the purpose of fighting; (2) India, after satisfactory indication that the Pakistani tribesmen were withdrawing and establishment of an effective cease-fire, should reduce its forces from the region to the minimum required to maintain law and order there; and (3) India should allow a U.N.-appointed Administrator to oversee a plebiscite "to decide whether the state of Jammu and Kashmir is to accede to India or Pakistan." Step one was never accomplished. A U.N. Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) was established in 1949 to oversee a cease-fire and it remains in place to date. UNSCR 80 of 1950 called for simultaneous force withdrawals, but this was rejected by India. Five UNSCRs during 1965 went largely unheeded by the warring parties (see http://unscr.com/en/resolutions). |

| 32. |

Sumit Ganguly, "The United States Can't Solve the Kashmir Dispute," Foreign Affairs (online), July 30, 2019; Suhasini Haider, "Why Does India Say No to Kashmir Mediation?," Hindu (Chennai), July 28, 2019. |

| 33. |

See Strobe Talbott, "The Day a Nuclear War Was Averted," Yale Global, September 13, 2004. |

| 34. |

"Obama Unlikely to Wade Into Kashmir 'Tar Pit' on His Trip," McClatchy Newspapers, November 4, 2010. |

| 35. |

See the Shimla Agreement at https://mea.gov.in/in-focus-article.htm?19005/Simla+Agreement+July+2+1972, and the Lahore Declaration at https://mea.gov.in/in-focus-article.htm?18997/Lahore+Declaration+February+1999. |

| 36. |

"Kashmir: The World's Most Dangerous Conflict," Deutsche Welt (Berlin), August 7, 2019. |

| 37. |

Indian and Pakistani negotiators had also agreed to provide greater autonomy to Kashmir's subregions, to draw down security forces over time, and to establish a "joint mechanism" for overseeing the rights of Kashmiris on both sides of the LOC. Yet the process was derailed by then-Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf's increasingly severe domestic political travails, which culminated in his ouster from office in August 2008. Three months later, the Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba's major terrorist attack on Mumbai, India, ended hopes of renewed talks (see "A Peace Plan for India and Pakistan Already Exists," New York Times, March 7, 2019). |

| 38. |

"Pakistan Has Decided to Bleed India With a Thousand Cuts: Army Chief," Times of India (Delhi), September 23, 2018. |

| 39. |

Acting Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs Alice Wells: We stand back and we look at the broader issue of Kashmir. Obviously, it occurs in a context of a long history of terrorism and terrorism that's been encouraged and fanned also by organizations that are present in Pakistan. And so, as part of our diplomacy in the region, we've urged Pakistan to implement what Prime Minister Khan has said needs to occur which is the elimination of these non-state actors and militant proxies and to ensure that they can't reach out across border, undertake terrorist acts inside … the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir or India proper. ("House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific and Nonproliferation Holds Hearing on Human Rights in South Asia," CQ Transcripts, October 22, 2019.) |

| 40. |

Sumit Ganguly, "Narendra Modi Should Calm Tensions in Kashmir Rather Than Inflame Them," Foreign Policy (online), February 19, 2019. |

| 41. |

In the words of one scholar, "The trope of Islamic radicalization fails to account for the structural violence that is embedded in the day-to-day lives of Kashmiris living under a military occupation" (Hafsa Kanjwal, "As India Beasts Its War Drums Over Pulwama, Its Occupation of Kashmir is Being Ignored" (op-ed), Washington Post, February 22, 2019). See also "Nadir in the Valley: India's Government Is Intensifying a Failed Strategy in Kashmir," Economist (London), March 9, 2019, and International Crisis Group, "Deadly Kashmir Suicide Bombing Ratchets Up India-Pakistan Tensions," February 22, 2019. |

| 42. |

See, for example, Ajai Shukla, "Kashmir Is in a Perilous State Because of India's Pivot to Nationalism" (op-ed), Guardian (London), March 3, 2019. |

| 43. |

In October 2019, a senior Indian journalist told a House panel that, "In the last 30 years, the majority in Kashmir has been silenced by the barrel of a gun that Pakistan has aimed at Kashmir.… Kashmiri society has been under siege for the last three decades because of Pakistan's proxy war in Kashmir" (see Aari Tikoo Singh's written statement and other hearing materials at https://go.usa.gov/xpS3D2). |

| 44. |

Vikram Sood, "Kashmir, Stop Being Delusional," Observer Research Foundation (New Delhi), May 6, 2017. |

| 45. |

The death of Hizbul Mujahideen militant Burhan Wani appeared to mark an inflection point in the insurgency, with militant recruitment numbers and the Indian government's reliance on coercive measures both rising since ("What Happened to Kashmir in the Last Five Years?," Scroll.in (online), January 26, 2019; "In Indian-Controlled Kashmir, Unprecedented Attack Puts Focus on 'Homegrown' Militants," Washington Post, February 17, 2019). |

| 46. |

See the South Asia Terrorism Portal data at https://tinyurl.com/yxcjjpag. |

| 47. |

"Mehbooba Mufti Resigns After BJP Withdraws Support," Al Jazeera (Doha), June 18, 2018. |

| 48. |