Defense Spending Under an Interim Continuing Resolution: In Brief

This report provides a basic overview of interim continuing resolutions (CRs) and highlights some specific issues pertaining to operations of the Department of Defense (DOD) under a CR.

DOD has started the fiscal year under a CR for 13 of the past 18 years (FY2002-FY2019) and every year since FY2010 excluding FY2019. The amount of time DOD has operated under CR authorities during the fiscal year has tended to increase in the past 10 years and equates to a total of more than 39 months since 2010.

As with regular appropriations bills, Congress can draft a CR to provide funding in many ways. Under current practice, a CR is an appropriation that provides either interim or full-year funding by referencing a set of established funding levels for the projects and activities that it funds (or covers). Such funding may be provided for a period of days, weeks, or months and may be extended through further continuing appropriations until regular appropriations are enacted, or until the fiscal year ends. In recent fiscal years, the referenced funding level on which interim or full-year continuing appropriations has been based was the amount of budget authority that was available under specified appropriations acts from the previous fiscal year.

CRs may also include provisions that enumerate exceptions to the duration, amount, or purposes for which those funds may be used for certain appropriations accounts or activities. Such provisions are commonly referred to as anomalies. The purpose of anomalies is to preserve Congress’s constitutional prerogative to provide appropriations in the manner it sees fit, even in instances when only interim funding is provided.

The lack of a full-year appropriation and the uncertainty associated with the temporary nature of a CR can create management challenges for federal agencies. DOD faces unique challenges operating under a CR while providing the military forces needed to deter war and defend the country. For example, an interim CR may prohibit an agency from initiating or resuming any project or activity for which funds were not available in the previous fiscal year (i.e., prohibit the use of procurement funds for “new starts,” that is, programs for which only R&D funds were appropriated in the previous year). Such limitations in recent CRs have affected a large number of DOD programs. Before the beginning of FY2018, DOD identified approximately 75 weapons programs that would be delayed by the FY2018 CR’s prohibition on new starts and nearly 40 programs that would be affected by a restriction on production quantity.

In addition, Congress may include provisions in interim CRs that place limits on the expenditure of appropriations for programs that spend a relatively high proportion of their funds in the early months of a fiscal year. Also, if a CR provides funds at the rate of the prior year’s appropriation, an agency may be provided additional (even unneeded) funds in one account, such as research and development, while leaving another account, such as procurement, underfunded.

By its very nature, an interim CR limits an agency’s ability to take advantage of efficiencies through bulk buys and multi-year contracts. It can foster inefficiencies by requiring short-term contracts that must be reissued once additional funding is provided, requiring additional or repetitive contracting actions. On the other hand, there is little evidence one way or the other as to whether the military effectiveness of U.S. forces has been fundamentally degraded by the limitations imposed by repeated CRs of months-long duration.

Defense Spending Under an Interim Continuing Resolution: In Brief

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background

- Funding Available Under a CR

- Full Text Versus Formulaic CRs

- Additional Limitations that CRs May Impose

- Anomalies

- How Agencies Implement a CR

- Unique Implementation Challenges Faced by DOD

- Prohibitions on Certain Contracting Actions

- Misalignments in CR-Provided Funding

- Assessing the Impact on DOD

- The Navy's $4 Billion Price Tag

- RAND Procurement Study

- Issues for Congress

Summary

This report provides a basic overview of interim continuing resolutions (CRs) and highlights some specific issues pertaining to operations of the Department of Defense (DOD) under a CR.

DOD has started the fiscal year under a CR for 13 of the past 18 years (FY2002-FY2019) and every year since FY2010 excluding FY2019. The amount of time DOD has operated under CR authorities during the fiscal year has tended to increase in the past 10 years and equates to a total of more than 39 months since 2010.

As with regular appropriations bills, Congress can draft a CR to provide funding in many ways. Under current practice, a CR is an appropriation that provides either interim or full-year funding by referencing a set of established funding levels for the projects and activities that it funds (or covers). Such funding may be provided for a period of days, weeks, or months and may be extended through further continuing appropriations until regular appropriations are enacted, or until the fiscal year ends. In recent fiscal years, the referenced funding level on which interim or full-year continuing appropriations has been based was the amount of budget authority that was available under specified appropriations acts from the previous fiscal year.

CRs may also include provisions that enumerate exceptions to the duration, amount, or purposes for which those funds may be used for certain appropriations accounts or activities. Such provisions are commonly referred to as anomalies. The purpose of anomalies is to preserve Congress's constitutional prerogative to provide appropriations in the manner it sees fit, even in instances when only interim funding is provided.

The lack of a full-year appropriation and the uncertainty associated with the temporary nature of a CR can create management challenges for federal agencies. DOD faces unique challenges operating under a CR while providing the military forces needed to deter war and defend the country. For example, an interim CR may prohibit an agency from initiating or resuming any project or activity for which funds were not available in the previous fiscal year (i.e., prohibit the use of procurement funds for "new starts," that is, programs for which only R&D funds were appropriated in the previous year). Such limitations in recent CRs have affected a large number of DOD programs. Before the beginning of FY2018, DOD identified approximately 75 weapons programs that would be delayed by the FY2018 CR's prohibition on new starts and nearly 40 programs that would be affected by a restriction on production quantity.

In addition, Congress may include provisions in interim CRs that place limits on the expenditure of appropriations for programs that spend a relatively high proportion of their funds in the early months of a fiscal year. Also, if a CR provides funds at the rate of the prior year's appropriation, an agency may be provided additional (even unneeded) funds in one account, such as research and development, while leaving another account, such as procurement, underfunded.

By its very nature, an interim CR limits an agency's ability to take advantage of efficiencies through bulk buys and multi-year contracts. It can foster inefficiencies by requiring short-term contracts that must be reissued once additional funding is provided, requiring additional or repetitive contracting actions. On the other hand, there is little evidence one way or the other as to whether the military effectiveness of U.S. forces has been fundamentally degraded by the limitations imposed by repeated CRs of months-long duration.

Background

Congress uses an annual appropriations process to fund the routine activities of most federal agencies. This process anticipates the enactment of 12 regular appropriations bills to fund these activities before the beginning of the fiscal year. When this process has not been completed before the start of the fiscal year, one or more continuing appropriations acts (commonly known as continuing resolutions or CRs) can be used to provide interim funding pending action on the regular appropriations.1

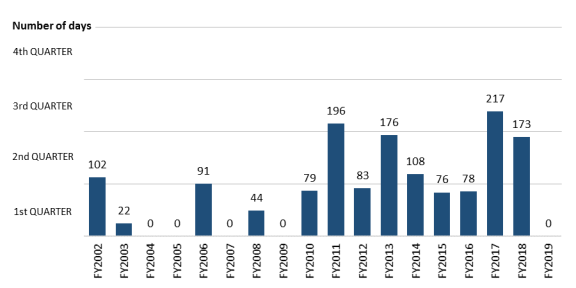

DOD has started the fiscal year under a CR for 13 of the past 18 years (FY2002-FY2019) and every year since FY2010 excluding FY2019.2 DOD has operated under a CR for an average of 119 days per year during the period FY2010-FY2019 compared to an average of 32 days per year during the period FY2002-FY2009 (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Days Under a Continuing Resolution: Department of Defense (FY2002-FY2019) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of dates of enactment of public law. See the CRS Appropriations Status Table at http://www.crs.gov/AppropriationsStatusTable/Index. |

All told, since 2010, DOD has spent 1,186 days—more than 39 months—operating under a CR, compared to 259 days—less than 9 months—during the 8 years preceding 2010.

To preserve congressional prerogatives to shape federal spending in the regular appropriations bills, the eventual enactment of which is expected, CRs typically contain limitations intended to allow execution of funds in a manner that provides for continuation of projects and activities with relatively few departures from the way funds were allocated in the previous fiscal year.3

However, DOD funding needs typically change from year to year across the agency's dozens of appropriations accounts for a variety of reasons, including emerging, increasing, or decreasing threats to national security. If accounts—and activities within accounts—are funded by a CR at a lower level than was requested in the pending Administration budget, then DOD cannot obligate funds at the anticipated rate. This can restrict planned personnel actions, maintenance and training activities, and a variety of contracted support actions. Delaying or deferring such actions can also cause a ripple effect, generating personnel shortages, equipment maintenance backlogs, oversubscribed training courses, and a surge in end-of-year contract spending.4

Given the frequency of CRs in recent years, many DOD program managers and senior leaders work well in advance of the outcome of annual decisions on appropriations to minimize contracting actions planned for the first quarter of the coming fiscal year.5 The Defense Acquisition University, DOD's education service for acquisition program management, advises students that, "[m]embers of the [Office of the Secretary of Defense], the Services and the acquisition community must consider late enactment to be the norm [emphasis in original] rather than the exception and, therefore, plan their acquisition strategy and obligation plans accordingly."6

In anticipation of such a delay in the availability of full funding for programs, DOD managers can build program schedules in which planned contracting actions are pushed to later in the fiscal year when it is more likely that a full appropriation will have been enacted. Additionally, managers can take steps to defer hiring actions, restrict travel policies, or cancel nonessential education and training events for personnel to keep their spending within the confines of a CR.

On their face, CRs are disruptive to routine agency operations and many of the procedures used by agencies to deal with limitations imposed by a CR entail costs. However, even though these disruptions have been routine for more than a decade, there has been little systematic analysis of the extent to which theses disruptions have led to measurable and significantly adverse impacts on U.S. military preparedness over the long run.

Funding Available Under a CR

An interim continuing resolution typically provides that budget authority is available at a certain rate of operations or funding rate for the covered projects and activities and for a specified period of time. The funding rate for a project or activity is based on the total amount of budget authority that would be available annually at the referenced funding level and is prorated based on the fraction of a year for which the interim CR is in effect.

In recent fiscal years, the referenced funding level has been the amount of budget authority that was available under specified appropriations acts from the previous fiscal year, or that amount modified by some formula. For example, the first CR for FY2018 (H.R. 601\P.L. 115-56) provided, "... such amounts as may be necessary, at a rate of operations as provided in the applicable appropriations Acts for fiscal year 2017 ... minus 0.6791%" (Division D, Section 101).7

While recent CRs typically have provided that the funding rates for certain accounts are to be calculated with reference to the funding rates in the previous year, Congress could establish a CR funding rate on any basis (e.g., the President's pending budget request, the appropriations bill for the pending year as passed by the House or Senate, or the bill for the pending year as reported by a committee of either chamber).

Full Text Versus Formulaic CRs

CRs have sometimes provided budget authority for some or all covered activities by incorporating the text of one or more regular appropriations bills for the current fiscal year. When this form of funding is provided in a CR or other type of annual appropriations act, it is often referred to as full text appropriations.

When full text appropriations are provided, those covered activities are not funded by a rate for operations, but by the amounts specified in the incorporated text. This full text approach is functionally equivalent to enacting regular appropriations for those activities, regardless of whether that text is enacted as part of a CR. The "Department of Defense and Full-Year Continuing Appropriations Act, FY2011" (P.L. 112-10) is one recent example. For DOD, the text of a regular appropriations bill was included as Division A, thus funding those covered activities via full text appropriations. In contrast, Division B of the bill provided funding for the projects and activities that normally would have been funded in the remaining eleven FY2011 regular appropriations according to a formula based on the previous fiscal year's appropriations laws.

If formulaic interim or full-year continuing appropriations were to be enacted for DOD, the funding levels for both base defense appropriations and Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) spending could be determined in a variety of ways. A separate formula could be established for defense spending, or the defense and nondefense spending activities could be funded under the same formula. Likewise, the level of OCO spending under a CR could be established by the general formula that applies to covered activities (as discussed above), or by providing an alternative rate or amount for such spending. For example, the first CR for FY2013 (P.L. 112-175) provided the following with regard to OCO funding:

Whenever an amount designated for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism pursuant to Section 251(b)(2)(A) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (in this section referred to as an "OCO/GWOT amount") in an Act described in paragraph (3) or (10) of subsection (a) that would be made available for a project or activity is different from the amount requested in the President's fiscal year 2013 budget request, the project or activity shall be continued at a rate for operations that would be permitted by ... the amount in the President's fiscal year 2013 budget request.

Additional Limitations that CRs May Impose

CRs may contain limitations that are generally written to allow execution of funds in a manner that provides for minimal continuation of projects and activities in order to preserve congressional prerogatives prior to the time a full appropriation is enacted.8 As an example, an interim CR may prohibit an agency from initiating or resuming any project or activity for which funds were not available in the previous fiscal year. Congress has, in practice, included a specific section (usually Section 102) in the CR to expressly prohibit DOD from starting production on a program that was not funded in prior years (i.e., a new start), and from increasing production rates above levels provided in the prior year.9 Congress may also limit certain contractual actions such as multiyear procurement contracts.10

Figure 2. Air Force Appropriations for Combat Rescue Helicopter

|

|

FY2019 enacted |

FY2020 request |

|

|

amounts in millions |

||

|

R&D |

$445.7 |

$247.0 |

|

Procurement |

$660.4 |

$884.2 |

|

Total |

$1,106.1 |

$1,131.3 |

An interim CR that uses the same formula to specify a funding rate for different appropriations accounts may cause problems for programs funded by more than one account, if the ratio of funding between the accounts changes from one year to the next. For example, as the Air Force program to procure a new combat rescue helicopter transitions from development to production between FY2019 and FY2020, the amount requested for R&D dropped by about $200 million while the amount requested for procurement rose by a 12-percent larger amount. Although the total amount requested for the program in FY2020 is thus $25 million higher than the total appropriated in FY2019, a CR that continued the earlier year's funding for the program would problematic: The nearly $200 million in excess R&D money could not be used to offset the more than $200 million shortfall in procurement funding, absent specific legislative relief. This kind of mismatch at the account level between the request and the CR is sometimes referred to as an issue with the color of money.11

Anomalies

Even though CRs typically provide funds at a particular rate, CRs may also include provisions that enumerate exceptions to the duration, amount, or purposes for which those funds may be used for certain appropriations accounts or activities. Such provisions are commonly referred to as anomalies. The purpose of anomalies is to insulate some operations from potential adverse effects of a CR while providing time for Congress and the President to agree on full-year appropriations and avoiding a government shutdown.12

A number of factors could influence the extent to which Congress decides to include such additional authority or flexibility for DOD under a CR. Consideration may be given to the degree to which funding allocations in full-year appropriations differ from what would be provided by the CR. Prior actions concerning flexibility delegated by Congress to DOD may also influence the future decisions of Congress for providing additional authority to DOD under a longer-term CR. In many cases, the degree of a CR's impact can be directly related to the length of time that DOD operates under a CR. While some mitigation measures (anomalies) might not be needed under a short-term CR, longer-term CRs may increase management challenges and risks for DOD.

An anomaly might be included to stipulate a set rate of operations for a specific activity, or to extend an expiring authority for the period of the CR. For example, the second CR for FY2017 (H.R. 2028\P.L. 114-254) granted three anomalies for DOD:

- Section 155 funded the Columbia Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program (Ohio Replacement) at a specific rate for operations of $773,138,000.

- Section 156 allowed funding to be made available for multi-year procurement contracts, including advance procurement, for the AH–64E Attack Helicopter and the UH–60M Black Hawk Helicopter.

- Section 157 provided funding for the Air Force's KC-46A Tanker, up to the rate for operations necessary to support the production rate specified in the President's FY2017 budget request (allowing procurement of 15 aircraft, rather the FY2016 rate of 12 aircraft).13

In anticipation of an FY2018 CR, DOD submitted a list of programs that would be affected under a CR to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). This "consolidated anomalies list" included approximately 75 programs that would be delayed by a prohibition on new starts and nearly 40 programs that would be negatively affected by a limitation on production quantity increases.14

OMB may or may not forward such a list to Congress as a formal request for consideration. Arguably, to the extent that anomalies make a CR more tolerable to an agency, they may reduce the incentive for Congress to reach a budget agreement. According to Mark Cancian, a defense budget analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, "a CR with too many anomalies starts looking like an appropriations bill and takes the pressure off."15

H.R. 601 (P.L. 115-56), the initial FY2018 CR, did not include any anomalies to address the programmatic issues included on the DOD list. H.R. 601 was extended through March 23, 2018, by four measures.16 The fourth measure (P.L. 115-123) included an anomaly to address concerns raised by the Air Force regarding the effects of the CR on certain FY2018 construction requirements.17

How Agencies Implement a CR

After enactment of a CR, OMB provides detailed directions to executive agencies on the availability of funds and how to proceed with budget execution. OMB will typically issue a bulletin that includes an announcement of an automatic apportionment of funds that will be made available for obligation, as a percentage of the annualized amount provided by the CR.

Funds usually are apportioned either in proportion to the time period of the fiscal year covered by the CR, or according to the historical, seasonal rate of obligations for the period of the year covered by the CR, whichever is lower. A 30-day CR might, therefore, provide 30 days' worth of funding, derived either from a certain annualized amount that is set by formula or from a historical spending pattern. In an interim CR, Congress also may provide authority for OMB to mitigate furloughs of federal employees by apportioning funds for personnel compensation and benefits at a higher rate for operations, albeit with some restrictions.18

In 2017 testimony before the Senate Subcommittee on Federal Spending Oversight and Emergency Management, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, a senior Government Accountability Office (GAO) analyst remarked that CRs can create budget uncertainty and disruptions, complicating agency operations and causing inefficiencies.19 Director of Strategic Issues Heather Krause asserted that "this presents challenges for federal agencies continuing to carry out their missions and plan for the future. Moreover, during a CR, agencies are often required to take the most limited funding actions."20 Krause testified that agency officials report taking a variety of actions to manage inefficiencies resulting from CRs, including shifting contract and grant cycles to later in the fiscal year to avoid repetitive work, and providing guidance on spending rather than allotting specific dollar amounts during CRs, to provide more flexibility and reduce the workload associated with changes in funding levels.

When operating under a CR, agencies encounter consequences that can be difficult to quantify, including additional obligatory paperwork, need for additional short-term contracting actions, and other managerial complications as the affected agencies work to implement funding restrictions and other limitations that the CR imposes. For example, the government can normally save money by buying in bulk under annual appropriations lasting a full fiscal year or enter into new contracts (or extend their options on existing agreements) to lock in discounts and exploit the government's purchasing power. These advantages may be lost when operating under a CR.

Unique Implementation Challenges Faced by DOD

All federal agencies face management challenges under a CR, but DOD faces unique challenges in providing the military forces needed to deter war and defend the country. In a letter to the leaders of the armed services committees dated September 8, 2017, then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis asserted that "longer term CRs impact the readiness of our forces and their equipment at a time when security threats are extraordinarily high. The longer the CR, the greater the consequences for our force."21 DOD officials argue that the department depends heavily on stable but flexible funding patterns and new start activities to maintain a modernized force ready to meet future threats. Former Defense Secretary Ashton Carter posited that CRs put commanders in a "straitjacket" that limits their ability to adapt, or keep pace with complex national security challenges around the world while responding to rapidly evolving threats like the Islamic State.22

Prohibitions on Certain Contracting Actions

As discussed, a CR typically includes a provision prohibiting DOD from initiating new programs or increasing production quantities beyond the prior year's rate. This can result in delayed development, production, testing, and fielding of DOD weapon systems. An inability to execute funding as planned can induce costly delays and repercussions in the complex schedules of weapons system development programs. Under a CR, DOD's ability to enter into planned long-term contracts is also typically restricted, thus forfeiting the program stability and efficiencies that can be gained by such contracts. Additionally, DOD has testified to Congress that CRs impact trust and confidence with suppliers, which may increase costs, time, and potential risk.23

Misalignments in CR-Provided Funding

Because CRs constrain funding by appropriations account rather than by program, DOD may encounter significant issues with programs that draw funds from several accounts. Already mentioned, above,24 is the color of money issue that can arise when a weapons program transitions from development into production. In such cases, the program could have excess R&D funding (based on the prior year's appropriation) and a shortfall in procurement funds needed to ramp up production.

A CR also can result in problems specific to the apportionment of funding in the Navy's shipbuilding account, known formally as the Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN) appropriation account. SCN appropriations are specifically annotated at the line-item level in the DOD annual appropriations bill. As a consequence, under a CR, SCN funding is managed not at the appropriations account level, but at the line-item level. For the SCN account—uniquely among DOD acquisition accounts—this can lead to misalignments (i.e., excesses and shortfalls) in funding under a CR for SCN-funded programs, compared to the amounts those programs received in the prior year. The shortfalls in particular can lead to program execution challenges under an extended or full-year CR.

Assessing the Impact on DOD

Published reports on the effect of CRs on agency operations typically provide anecdotal assertions that such funding measures increase costs and reduce efficiencies. However, these accounts typically do not provide data that would permit a systematic analysis of CR effects. Nor do they address the impact of CR-caused near-term bureaucratic disruption on the combat capability and readiness of U.S. forces over the longer-term.

One exception to this general rule—discussed below—is a 2019 study by the RAND Corporation of the effect of CRs on a limited number of DOD procurement programs. That analysis, "did not find strong evidence … indicating that CRs are generally associated with delays in procurement awards or increased costs," although the authors of the study emphasized that, because of its limited scope, the study, "does not imply that the widely expressed concerns regarding CR effects are invalid."25

The Navy's $4 Billion Price Tag

One widely publicized estimate of the cost of recent CRs stands apart in the level of detail available on how the figure was calculated. In a December 4, 2017, speech at a defense symposium, Secretary of the Navy Richard Spencer said that CRs had cost the Navy, "about $4 billion since 2011."26 CRS asked the Navy for the source of the $4 billion figure and for details on how it was calculated. In response, the Navy provided CRS with an information paper that stated the following in part:

CRs have averaged 106 days per year in the last decade, or 29% of each year. This means over one quarter of every year is lost or has to be renegotiated for over 100,000 DON [Department of the Navy] contracts (conservative estimate) and billions of dollars. Contractors translate this CR uncertainty into the prices they charge the government.

– The cost factors at work here are: price uncertainty caused by the CR and reflected in higher rates charged to the government; government time to perform multiple incremental payments or renegotiate; and contractor time to renegotiate or perform unnecessary rework caused by the CR. These efforts are estimated at approximately 1/7th of a man-year for all stakeholders or $26K [$26,000] per average contract.

– $26K x 100,000 contracts = $2.6B [$2.6 billion] per year. While the estimate for each contract would be different, it can readily be seen that this is a low but reasonable estimate.27

The Navy paper did not provide any justification for the assumptions underpinning that calculation.

RAND Procurement Study

The literature on CR effects includes one relatively rigorous effort to determine whether multi-month CRs are associated with delays and cost increases in DOD procurement programs.

The study, conducted in 2017 by the RAND Corporation, was sponsored by the office of DOD's senior acquisition official (the then-Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics). Summarizing its review of the literature on CR effects, the RAND team said

Because of a lack of quantitative data, many of the [asserted] consequences … would be very difficult to estimate quantitatively or to conclusively demonstrate. All of the research that we reviewed on the consequences of operating under a CR employed qualitative approaches that focused on case studies, assertions, and anecdotal information.28

To see whether CRs systematically are associated with cost increases and delays in DOD procurements, RAND examined 151 procurement awards for relatively high-profile programs during FY2013-FY2015. In each of those years, DOD operated under CRs for several months.

Comparing procurement awards originally scheduled to occur while the agency was under a CR with those made after a regular appropriations bill had been enacted, the study found no statistically significant difference between the two groups in

- whether an award was delayed;

- if it was delayed, the length of the delay; or

- whether the unit cost increased compared with the projected cost.

RAND also compared the 151 procurement awards made during FY2013-FY2015—years when there were prolonged CRs—with 48 awards made during FY1999, when DOD operated under a CR for only the first 3 weeks of the fiscal year. A comparison of the awards made during the period of "long-CRs" (2013-15) with awards made during a period in which there was one relatively short CR (FY1999) showed

- no statistically significant difference in the percentage of awards that were delayed;

- for cases in which a delay occurred, longer delays in FY2013-FY2015 than in the earlier period; and

- larger unit-cost increases (relative to original projections) for cases during the FY1999 (i.e., the "short-CR" period).

In sum, RAND concluded, "we did not find strong evidence … that CRs are generally associated with delays in procurement awards or increased costs. On the other hand, given the limitations inherent in our statistical analysis, we cannot use its results to rule out the occurrence of these kinds of negative effects."29

Issues for Congress

Inasmuch as CRs have become relatively routine, Congress may wish to mandate a broader and more systematic assessment of DOD's use of what the RAND study calls "levers of management discretion" to ameliorate their potential adverse impacts. In addition to cataloguing the techniques used and estimating their near-term costs, if any, Congress also may sponsor assessments of the impact of CRs over the longer term.

After nearly a decade of managerial improvisation to cope with relatively long-term CRs' disruption of normal procedures, Congress may wish to look for evidence that the DOD has suffered adverse systemic impacts—problems that go beyond marginal increases in cost or time to impair DOD's ability to protect the national security.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Legislation that continues appropriations in the absence of a regular appropriations act is commonly referred to as a continuing resolution because it usually provides continuing appropriations in the form of a joint resolution rather than a bill. However, continuing appropriations are also occasionally provided through a bill. |

| 2. |

In all but three of the past 40 years, Congress has passed CRs to enable at least some federal agencies to continue operating when their annual appropriation bills have not been enacted before the start of the fiscal year. See CRS Report R42647, Continuing Resolutions: Overview of Components and Practices; and U.S. Government Accountability Office, Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Federal Spending Oversight and Emergency Management, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate, Budget Uncertainty and Disruptions Affect Timing of Agency Spending, GAO-17-807T, September 20, 2017, available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687264.pdf. |

| 3. |

CRS Report RL34700, Interim Continuing Resolutions (CRs): Potential Impacts on Agency Operations. |

| 4. |

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10365, End-Year DOD Contract Spending. |

| 5. |

Ibid. |

| 6. |

Gregory Martin, "President's Budget Submission and the Congressional Enactment Process," Teaching Note, National Defense University, VA, April 2013, https://acc.dau.mil/adl/en-US/44269/file/76896/Congressional%20Enactmanet%20Process%20April%202013.pdf. |

| 7. |

The application of the FY2017 amounts is provided by subsection (a). The 0.6791% reduction to those amounts is required by subsection (b). |

| 8. |

CRS Report RL34700, Interim Continuing Resolutions (CRs): Potential Impacts on Agency Operations. |

| 9. |

Section 102(a) of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 (H.R. 601) states "No appropriation or funds made available or authority granted pursuant to section 101 for the Department of Defense shall be used for: (1) the new production of items not funded for production in fiscal year 2017 or prior years; (2) the increase in production rates above those sustained with fiscal year 2017 funds; or (3) the initiation, resumption, or continuation of any project, activity, operation, or organization ... for which appropriations, funds, or other authority were not available during fiscal year 2017." |

| 10. |

Section 102(b) of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 (H.R. 601) states "No appropriation or funds made available or authority granted pursuant to section 101 for the Department of Defense shall be used to initiate multiyear procurements utilizing advance procurement funding for economic order quantity procurement unless specifically appropriated later." |

| 11. |

The colloquialism color of money is often used in defense circles to refer to accounts (e.g., Military Personnel, Operation and Maintenance, Procurement, and Research, Development, Test and Evaluation) used in appropriations acts. A color of money problem would imply that funding was provided in one account, when it was actually needed in another. See "Misalignments in CR-provided Funding," section below. |

| 12. |

CRS Report RL34680, Shutdown of the Federal Government: Causes, Processes, and Effects. |

| 13. |

For further discussion on included anomalies in recent CRs, see the "Agency, Account, and Program-Specific Provisions" sections in CRS Report R44978, Overview of Continuing Appropriations for FY2018 (P.L. 115-56), CRS Report R44723, Overview of Further Continuing Appropriations for FY2017 (H.R. 2028), and CRS Report R44653, Overview of Continuing Appropriations for FY2017 (H.R. 5325). |

| 14. |

Tony Bertuca, "Pentagon sends White House detailed list of budget priorities threatened by Capitol Hill stalemate," September 11, 2017, Inside Defense, available at https://insidedefense.com/share/189868. |

| 15. |

Ibid. |

| 16. |

The FY2018 CR (H.R. 601) was extended by Division A of H.J.Res. 123 (P.L. 115-90), Division A of H.R. 1370 (P.L. 115-96), Division B of H.R. 195 (P.L. 115-120), and Division B of H.R. 1892 (P.L. 115-123). Division C of P.L. 115-123, also referred to as the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, included increases to the discretionary spending limitations for FY2018 and FY2019 set by the Budget Control Act of 2011. The BCA limits for defense were increased by $80 billion in FY2018 and $85 billion in FY2019. |

| 17. |

January 29, 2018, letter sent to the Committees on Appropriations of both Houses of Congress. |

| 18. |

CRS Report RL34700, Interim Continuing Resolutions (CRs): Potential Impacts on Agency Operations. |

| 19. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Federal Spending Oversight and Emergency Management, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate, Budget Uncertainty and Disruptions Affect Timing of Agency Spending, GAO-17-807T, September 20, 2017, available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687264.pdf. |

| 20. |

Ibid. |

| 21. |

Letter from Secretary of Defense James Mattis to Sen. John McCain on the potential effects of a continuing resolution on the U.S. military, September 8, 2017, available at https://news.usni.org/2017/09/13/document-secdef-mattis-letter-mccain-effects-new-continuing-resolution-pentagon. |

| 22. |

U.S. Department of Defense, "Statement from Secretary of Defense Ash Carter on Omnibus Bill Negotiations," press release, December 8, 2015, available at http://www.defense.gov/News/News-Releases/News-Release-View/Article/633403/statement-from-secretary-of-defense-ash-carter-on-omnibus-bill-negotiations. |

| 23. |

Testimony before the Armed Services Committee, U.S. Senate, Long-Term Budgetary Challenges Facing the Military Services and Innovative Solutions for Maintaining our Military Superiority, 114th Cong., 2nd sess. (S.Hrg.114-765), September 15, 2016, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114shrg29881/pdf/CHRG-114shrg29881.pdf. |

| 24. |

See p. 4, supra. |

| 25. |

Stephanie Young and J. Michael Gilmore. Operating Under a Continuing Resolution: A Limited Assessment of Effects on Defense Procurement Contract Awards, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, 2019, p. 39. |

| 26. |

Secretary of the Navy Richard V. Spencer, [address to] USNI [U.S. Naval Institute]—Defense Forum Washington, Washington, DC, December 4, 2017, remarks as prepared, p. 6. |

| 27. |

Navy information paper entitled "Characterizing Costs of the Budget Control Act & Continuing Resolution," undated, received by CRS from Navy Office of Legislative Affairs, December 15, 2017. |

| 28. |

Young and Gilmore, p. 16. |

| 29. |

Ibid., p. 10. |