The Department of Defense’s JEDI Cloud Program

In September 2017, the Deputy Secretary of Defense issued a memorandum calling for the accelerated adoption of a Department of Defense (DOD) enterprise-wide cloud services solution as a fundamental component of ongoing DOD modernization efforts. As a component of this effort, DOD is seeking to acquire a cloud services solution accessible to the entirety of the Department that can support Unclassified, Secret, and Top Secret requirements, focusing on commercially available cloud service solutions, through the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI) Cloud acquisition program.

DOD intends to conduct a full and open competition that is expected to result in a single award Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity firm-fixed price contract for commercial items. DOD has indicated that the minimum guaranteed award is $1 million, and that the initial period of performance is two years. The contract is expected to have a maximum ceiling of $10 billion across a potential 10-year period of performance. DOD is in the final stages of evaluating proposals, with Amazon Web Services and Microsoft remaining in contention for the contract. The Department originally expected to award the contract in August 2019. However, Secretary of Defense Dr. Mark T. Esper is reportedly currently reviewing the JEDI Cloud program, which may delay the award.

Significant industry and congressional attention has been focused on DOD’s intent to award the JEDI Cloud contract to a single company. Oracle America filed multiple pre-award bid protests with the Government Accountability Office, which were denied. Oracle America then filed a bid protest lawsuit with the U.S. Court of Federal Claims; the court ruled against Oracle in a July 12, 2019, decision. In filings associated with its bid protests, Oracle America alleged in part that the JEDI Cloud acquisition process was unfairly skewed in favor of Amazon Web Services through potential organizational conflicts of interest associated with three former DOD employees, each of whom was involved to greater or lesser degrees in the early development of the program. DOD investigations determined that Amazon Web Services had no conflicts of interest and established that the actions of the individuals identified by Oracle America did not negatively impact the procurement or grant Amazon Web Services an unfair competitive advantage. However, the investigations did identify individual violations of ethical standards established by the Federal Acquisition Regulation.

Some industry observers contend that an initial single award appears to contradict broader federal cloud computing implementation guidance and industry best practices that stress the importance of multi-cloud solutions. Others point to the implementation approaches identified by DOD’s 2019 Cloud Strategy as evidence that the Department expects the JEDI Cloud to serve certain enterprise-wide functions, performing as one component of a broader multi-cloud, multi-vendor system. Opponents of DOD’s use of a single-award contract for the JEDI Cloud program have suggested that this tactic could restrict future competition for enterprise-wide DOD cloud services. Supporters of DOD’s approach argue that the JEDI Cloud program’s requirement for offerors to develop applications and data schema easily transferable to different platforms suggests that the Department may be equipped to migrate from any service environment developed under the JEDI Cloud contract to another such environment.

Several Members of Congress have engaged the Administration to express their views regarding the JEDI Cloud acquisition program and pending contract award. The 116th Congress is considering related authorization and appropriations legislation that could shape future implementation of the program (H.R. 2740, H.R. 2500, and S. 1790).

The Department of Defense's JEDI Cloud Program

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- What Is Cloud Computing?

- What Is the Current Status of DOD's Adoption of Cloud Services?

- What Is DOD's Current Cloud Strategy?

- What Acquisition Policies Apply to DOD Procurement of Cloud Services?

- The JEDI Cloud Program

- Why Does DOD Require the JEDI Cloud?

- Who Has Responsibility for the JEDI Cloud Program Within DOD?

- What Is the Current Status of the JEDI Cloud Contract?

- How Is the JEDI Cloud Contract Structured?

- What Is the Source Selection Process for the JEDI Cloud Contract?

- Reactions from Observers and Congress

- How Has Industry Reacted?

- GAO Bid Protests and U.S. Court of Federal Claims Case

- How Has DOD Responded to Industry Concerns?

- Potential for Restriction of Future Competition

- Use of a Single-Award Contract

- What Actions Has Congress Taken?

- Legislative Action in the 115th Congress

- Proposed Legislative Action in the 116th Congress

- Other Congressional Actions

- Considerations for Congress

Figures

Summary

In September 2017, the Deputy Secretary of Defense issued a memorandum calling for the accelerated adoption of a Department of Defense (DOD) enterprise-wide cloud services solution as a fundamental component of ongoing DOD modernization efforts. As a component of this effort, DOD is seeking to acquire a cloud services solution accessible to the entirety of the Department that can support Unclassified, Secret, and Top Secret requirements, focusing on commercially available cloud service solutions, through the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI) Cloud acquisition program.

DOD intends to conduct a full and open competition that is expected to result in a single award Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity firm-fixed price contract for commercial items. DOD has indicated that the minimum guaranteed award is $1 million, and that the initial period of performance is two years. The contract is expected to have a maximum ceiling of $10 billion across a potential 10-year period of performance. DOD is in the final stages of evaluating proposals, with Amazon Web Services and Microsoft remaining in contention for the contract. The Department originally expected to award the contract in August 2019. However, Secretary of Defense Dr. Mark T. Esper is reportedly currently reviewing the JEDI Cloud program, which may delay the award.

Significant industry and congressional attention has been focused on DOD's intent to award the JEDI Cloud contract to a single company. Oracle America filed multiple pre-award bid protests with the Government Accountability Office, which were denied. Oracle America then filed a bid protest lawsuit with the U.S. Court of Federal Claims; the court ruled against Oracle in a July 12, 2019, decision. In filings associated with its bid protests, Oracle America alleged in part that the JEDI Cloud acquisition process was unfairly skewed in favor of Amazon Web Services through potential organizational conflicts of interest associated with three former DOD employees, each of whom was involved to greater or lesser degrees in the early development of the program. DOD investigations determined that Amazon Web Services had no conflicts of interest and established that the actions of the individuals identified by Oracle America did not negatively impact the procurement or grant Amazon Web Services an unfair competitive advantage. However, the investigations did identify individual violations of ethical standards established by the Federal Acquisition Regulation.

Some industry observers contend that an initial single award appears to contradict broader federal cloud computing implementation guidance and industry best practices that stress the importance of multi-cloud solutions. Others point to the implementation approaches identified by DOD's 2019 Cloud Strategy as evidence that the Department expects the JEDI Cloud to serve certain enterprise-wide functions, performing as one component of a broader multi-cloud, multi-vendor system. Opponents of DOD's use of a single-award contract for the JEDI Cloud program have suggested that this tactic could restrict future competition for enterprise-wide DOD cloud services. Supporters of DOD's approach argue that the JEDI Cloud program's requirement for offerors to develop applications and data schema easily transferable to different platforms suggests that the Department may be equipped to migrate from any service environment developed under the JEDI Cloud contract to another such environment.

Several Members of Congress have engaged the Administration to express their views regarding the JEDI Cloud acquisition program and pending contract award. The 116th Congress is considering related authorization and appropriations legislation that could shape future implementation of the program (H.R. 2740, H.R. 2500, and S. 1790).

Introduction

This report provides analysis of relevant background information and considerations for Congress associated with ongoing Department of Defense (DOD) efforts to obtain enterprise-wide cloud computing services through the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI) Cloud acquisition program.

In September 2017, then-Deputy Secretary of Defense (DSD) Patrick Shanahan issued a memorandum calling for the accelerated adoption of a DOD enterprise-wide cloud services solution as a key component of ongoing DOD modernization efforts.1 DOD views this adoption process as a two part effort: in the first phase, DOD is seeking to acquire a cloud services solution accessible to the entirety of the Department that can support Unclassified, Secret, and Top Secret requirements, focusing on commercially available cloud service solutions, through the JEDI Cloud acquisition program.2 In the second phase, DOD seeks to transition selected existing data and applications maintained by the military departments and agencies to the cloud.

Background

What Is Cloud Computing?

Broadly speaking, cloud computing refers to the practice of remotely storing and accessing information and software programs on demand through the internet, instead of storing data on a computer's hard drive or accessing it through an organization's intranet.3 It relies on a cloud infrastructure, a collection of hardware and software that may include components such as servers and a network. This infrastructure can be deployed privately to a select user group, publicly through subscription-based commercial services available to the general public, or through hybrid deployments that combine aspects of both private and public cloud infrastructure.

Cloud computing capabilities are delivered to end users through three main service models:

- Software as a Service (SaaS), which provides end users with access to software applications hosted and managed by the cloud computing provider (such as Dropbox, Slack, or Google web-based applications);

- Platform as a Service (PaaS), which provides end users with the ability to construct and distribute web-based software applications through a common interface hosted and managed by the cloud computing provider (such as Google App Engine, Amazon Web Services Elastic Beanstalk, Microsoft Azure, and Oracle Cloud); and

- Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), which provides end users with remote access to infrastructure components—such as servers, virtual machines, and storage—maintained by the cloud computing provider (such as Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud, Google Compute Engine, and Microsoft Azure).

Many major cloud vendors, such as Microsoft and Amazon, are increasingly offering products and services that combine aspects of these service models.4

Cost, efficiency, accessibility, agility of improvements, security, and reliability are all considerations in public and private sector decisions about cloud service adoption. For a more in-depth discussion of these factors and cloud computing characteristics, deployment models, and service models, see CRS Report R42887, Overview and Issues for Implementation of the Federal Cloud Computing Initiative: Implications for Federal Information Technology Reform Management, by Patricia Moloney Figliola and Eric A. Fischer.

What Is the Current Status of DOD's Adoption of Cloud Services?

Since the establishment of the Federal Cloud Computing Initiative (FCCI) in 2009, the federal government—including DOD—has actively worked to shift portions of its information technology (IT) needs to cloud-based services through strategies such as "Cloud First," which required federal agencies to prioritize the use of cloud-based solutions whenever a secure, reliable, and cost-effective option existed.5 This move was intended in part to reduce the total investment by the federal government in physical information technology (IT) infrastructure—through actions such as reducing or eliminating data storage at agency-owned and operated data centers—as well as capitalizing on other advantages of cloud adoption.6

DOD efforts to acquire cloud services have been ongoing; however, DOD has described its current cloud services use as "decentralized" and "disparate," creating "additional layers of complexity" that impede shared access to common applications and data across the Department.7 As of mid-2018, DOD reported maintaining more than 500 public and private cloud infrastructures that support Unclassified and Secret requirements.8 DOD has also acknowledged that its prior lack of "clear guidance on cloud computing, adoption, and migration," as well as acquisition guidance that allowed DOD components to independently pursue the procurement of cloud-based services, has led to "disjointed implementations with limited capability, siloed data, and inefficient acquisitions that cannot take advantage of economies of scale."9

What Is DOD's Current Cloud Strategy?

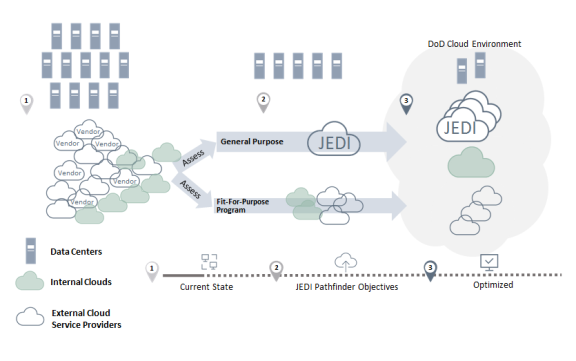

DOD publicly released its current "Cloud Strategy" in February 2019.10 As part of its cloud strategy, DOD identifies the need to adopt cloud computing services across the Department as a priority, and articulates its intent to develop a "multi-cloud, multi-vendor … ecosystem composed of a General Purpose and [multiple] Fit For Purpose" (see Figure 1) clouds.11

DOD anticipates that the JEDI Cloud acquisition program will ultimately lead to a foundational enterprise-wide "General Purpose" cloud suitable for the majority of DOD systems and applications, enabling DOD to offer IaaS and PaaS at all classification levels.12 "Fit For Purpose" clouds, on the other hand, are envisioned as task-specific "commercial solution[s]"—such as the ongoing Defense Enterprise Office Solutions (DEOS) SaaS acquisition program that will create a cloud-based replacement for certain DOD software-based applications such as email and instant messaging services—or "on-premises cloud solution[s]," such as DISA's milCloud 2.0, which provides IaaS, to be used in limited situations where the "General Purpose" cloud cannot adequately support mission needs."13

What Acquisition Policies Apply to DOD Procurement of Cloud Services?

While the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) does not explicitly provide acquisition guidance for cloud computing services, certain sections (e.g., FAR Part 39, Acquisition of Information Technology or FAR Part 12, Acquisition of Commercial Items) may apply depending on the specific acquisition strategy for a particular contract.14 Certain other government-wide acquisition policies for cloud services, such as the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) security assessment process, apply.15

DOD-specific policies for acquiring cloud services are prescribed in part by Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) Subpart 239.76, which states that DOD must generally acquire cloud services using commercial terms and conditions—such as license agreements, end user license agreements, terms of service, or other similar legal instruments—consistent with federal law and DOD's needs.16 A contract to acquire cloud services may generally only be awarded to a provider with provisional Defense Information Security Agency (DISA) authorization to provide such services, consistent with the current version of the DOD Cloud Computing Security Requirements Guide (SRG).17

To maintain legal jurisdiction over information and data accessed via a cloud services solution, all data stored and processed by or for DOD must reside in a facility under the exclusive legal jurisdiction of the United States—meaning that cloud computing service providers are generally required to store government data that is not physically located on DOD premises at locations within the United States or outlying areas of the United States.18

All cloud services must have an Authorization to Operate (ATO), an official decision made by a senior official that explicitly accepts any associated operational risks (i.e., risks to organizational operations or assets; individuals; other organizations; or the United States). An ATO is based on the implementation of an agreed-upon set of security controls.19 The 2014 DOD Memorandum Updated Guidance on the Acquisition and Use of Commercial Cloud Computing Services authorized the direct acquisition of cloud services by DOD components, and provided additional guidance for the acquisition of commercial cloud services.20

The JEDI Cloud Program

Why Does DOD Require the JEDI Cloud?

In the unclassified summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS), the Department articulates the need for significant DOD investment in key technology capabilities such as "cyber defense, resilience, and the continued integration of cyber capabilities into the full spectrum of military operations," as well as "military application of autonomy, artificial intelligence, and machine learning" in order to maintain military superiority against near-peer adversaries such as China and Russia.21 The Department views the cloud computing and data storage capabilities to be acquired through the JEDI Cloud procurement as providing "foundational technologies" for these investments.22 The Joint Chiefs of Staff has also stated that "efforts for accelerating [cloud adoption] are critical in creating a global, resilient, and secure information environment that enables warfighting and mission command."23 DOD Chief Information Officer (CIO) Dana Deasy has further contended that the Department requires an enterprise-wide cloud "that allows for data-driven decision making [and] enables DOD to take advantage of our applications and data resources," in part to provide worldwide support for DOD operations.24

In recent public statements DOD CIO Deasy, as well as Lt. Gen. Bradford J. Shwedo, Director for Command, Control, Communications and Computers/Cyber of the J6 Command, Control, Communications, and Computers (C4) and Cyber Directorate of the Joint Staff, have also emphasized that delays in pursuing the capabilities included in the JEDI Cloud procurement may adversely affect ongoing Department activities, such as the recently established Joint Artificial Intelligence Center, which seeks to accelerate the delivery of artificial intelligence-enabled capabilities to DOD.25

Who Has Responsibility for the JEDI Cloud Program Within DOD?

Initially, the Cloud Executive Steering Group (CESG) oversaw DOD's cloud adoption initiative. The CESG, established in September 2017, reported directly to the Deputy Secretary of Defense (DSD).26 The CESG was originally chaired by Ellen Lord, then the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (USD (AT&L)).27 At first, the CESG included the Director of the Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO), the Managing Partner of the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUx, now known as the Defense Innovation Unit, or DIU), the Director of the Defense Digital Service (DDS), and the Executive Director of the Defense Innovation Board (DIB) as voting members (see Table 1).28 The DDS Director was tasked with leading phase one of DOD's cloud adoption initiative: the JEDI Cloud program.

In January 2018, the DSD announced changes to the membership and leadership of the CESG; the Deputy Chief Management Officer (DCMO; Jay Gibson, who was serving as DCMO at the time, would later become DOD's first CMO) would chair the group, with the Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) and the DOD CIO added to the group's members.29

In June 2018, the DSD announced that the DOD CIO, as the principal staff assistant and senior advisor to the Secretary of Defense for information technology, would oversee all aspects of DOD's cloud adoption initiative, to include the JEDI Cloud acquisition program.30 The Cloud Computing Program Office (CCPO), which was established by DDS to serve as the program office for the JEDI Cloud program, was also transitioned to the Office of the CIO at that time.31

|

CESG Membership (September 2017) |

CESG Membership (January 2018) |

|

USD (AT&L), Chair |

DOD CMO, Chaira |

|

Director, SCO |

Director, SCO |

|

Managing Partner, DIUx |

Managing Partner, DIUx |

|

Director, DDS |

Director, DDS |

|

Executive Director, DIB |

Executive Director, DIB |

|

Director, CAPE |

|

|

DOD CIO |

Sources: Deputy Secretary of Defense, "Accelerating Enterprise Cloud Adoption," September 13, 2017, memorandum, and Deputy Secretary of Defense, "Accelerating Enterprise Cloud Adoption Update," January 4, 2018, memorandum.

a. In January 2018, the DSD named Jay Gibson, who was serving as Deputy Chief Management Officer for DOD, as the chair of the CESG. Gibson became DOD CMO in February 2018 and resigned in November 2018.

What Is the Current Status of the JEDI Cloud Contract?

A Request for Information (RFI) for the JEDI Cloud program was issued in October 2017; the Department held an industry day event and issued a draft Request for Proposal (RFP) in early March 2018, with a second draft RFP issued in April 2018.32 The final JEDI RFP was issued on July 26, 2018, and closed on October 9, 2018.33 In early April 2019, DOD announced that the Department had completed an initial downselect from four qualified proposals submitted by IBM, Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, and Oracle America.34 Amazon Web Services and Microsoft remain in contention for the contract. The Department is in the final stages of evaluating proposals, and originally anticipated announcing a contract award decision in August 2019.35 However, Secretary of Defense Dr. Mark T. Esper is reportedly currently reviewing the JEDI Cloud program, which may delay the award.36

DOD requested $61.9 million in funding for the JEDI Cloud acquisition program for Fiscal Year (FY) 2020.37

How Is the JEDI Cloud Contract Structured?

Through the JEDI Cloud contract, DOD intends to conduct a full and open competition that will result in a single award Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (ID/IQ) firm-fixed price contract for commercial items (i.e., IaaS and PaaS).38

|

What Is Full and Open Competition? References to competition in the context of federal procurement generally indicate a marketplace condition in which two or more entities, acting independently of each other and of the government, attempt to obtain business by submitting bids or proposals to provide the U.S. government with goods or services.39 Full and open competition, as required for most U.S. government procurement contracts by the Competition in Contracting Act (CICA) of 1984 (Title VII of P.L. 98-369), is achieved when all capable prospective contractors are permitted to submit bids or proposals in response to a proposed contract action.40 What Is an ID/IQ Contract? An indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (ID/IQ) contract allows the U.S. government to obtain an unspecified quantity of supplies or services over an unspecified period of time. An indefinite-quantity contract can also be referred to as a task-order contract. A task-order contract does not procure a firm quantity of services (other than a minimum or maximum quantity) and allows the issuance of orders for the performance of tasks (i.e., task orders) under the contract. What Is a Firm-Fixed Price Contract? A firm-fixed price contract generally establishes set prices for goods or services obtained through contract activities. These prices are not subject to adjustment, even if the contractor's actual cost experience in carrying out contract activities results in a net profit or loss. Firm-fixed price contracts are intended to incentivize contractor cost control and effective performance. |

DOD wants the JEDI Cloud to provide worldwide cloud computing services—including in austere environments—comparable to those made available through commercial cloud services. Accordingly, the Department has specified that an offeror does not need to maintain dedicated or exclusive infrastructure for unclassified services. However, offerors must comply with the JEDI Cloud Cyber Security Plan, and must provide dedicated, exclusive infrastructure for classified services.41

DOD is further requiring any successful offeror to provide rapid deployment of new commercially available cloud-related services to JEDI Cloud users, and expects ongoing parity with public commercial prices. DOD indicated that the minimum guaranteed award is $1 million. The contract is expected to have a maximum ceiling of $10 billion across a potential 10-year period of performance. Under an ID/IQ contract, the government is only required to purchase the minimum amount specified in the contract, and may ultimately choose not to reach the contract ceiling. The contract period of performance is structured as a two-year base ordering period, with three additional option periods (two three-year options and one two-year option), for a potential total of 10 years (see Table 1).

|

Period of Performance |

Timeframe |

|

Base ordering period (2 years, guaranteed) |

2019-2021 |

|

Option #1 (3 years, if exercised) |

2021-2024 |

|

Option #2 (3 years, if exercised) |

2024-2027 |

|

Option #3 (2 years, if exercised) |

2027-2029 |

Source: JEDI Cloud RFP, "Combined Synopsis/Solicitation for Commercial Items," as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ.

What Is the Source Selection Process for the JEDI Cloud Contract?

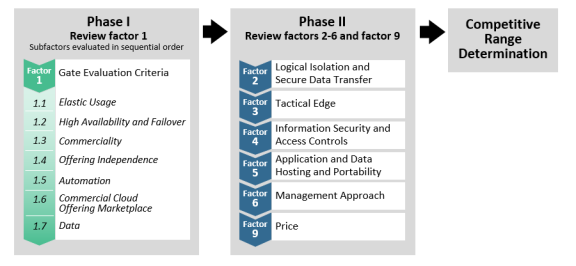

DOD indicated that it will award the JEDI Cloud contract to the offeror whose proposal meets specified requirements and represents the best value to the government, based on a two-step evaluation process.42 In the first step, offerors were evaluated against seven performance-based criteria (see Figure 2 for a full listing).343 Proposals were deemed acceptable or unacceptable for each individual sub-factor as considered sequentially: a judgement of unacceptable immediately disqualified a proposal from further consideration.44 For example, performance sub-factor 1.1, "Elastic Usage," requires offerors to provide summary data for the months of January and February 2018 in order to demonstrate that additional traffic generated by unclassified usage of the JEDI Cloud would not represent a majority of a proposed solution's commercially available network, computational, and storage capacity. Performance sub-factor 1.2, "High Availability and Failover," in part requires offerors to have no fewer than three existing physical data centers at least 150 miles apart within the United States or outlying areas of the United States.

If a proposal received a mark of "acceptable" for each sub-factor, it proceeded to the second phase of the source selection process, where it was then evaluated against five additional technical factors, together with submitted price proposals, to determine a "competitive range" of offerors.45 Qualifying offerors within the competitive range were next evaluated against two additional factors: the offeror's approach to meeting small business participation goals and a demonstration of the proposed solution's capabilities.

|

Figure 2. JEDI Cloud Competitive Range Determination Source Selection Process |

|

|

Sources: CRS adaptation of "Source Selection Process," as included in Department of Defense, "JEDI Cloud Industry Day," March 2018, slide 22, available at https://go.usa.gov/xyvYn, and updated by information contained in JEDI Cloud RFP, "Combined Synopsis/Solicitation for Commercial Items," pages 88-95, as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package updated on October 9, 2018, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ. |

Reactions from Observers and Congress

How Has Industry Reacted?

DOD received more than 1,500 comments in response to its draft RFPs. Companies including Amazon Web Services, Google, IBM, and Microsoft initially expressed interest in competing for the JEDI Cloud contract.46 However, DOD's acquisition strategy also sparked resistance from those who opposed DOD's intent to award the contract to a single company. This concern led some industry associations to publicly contest a single award, arguing that it would be inconsistent with broader federal cloud computing implementation guidance, and could unfairly restrict future competition for DOD cloud services.47

For example, the trade group ITAPS (IT Alliance for Public Sector) sent a letter to the House and Senate Armed Services committees stating in part that the

deployment of a single cloud conflicts with established best practices and industry trends in the commercial marketplace, as well as current law and regulation, which calls for the award of multiple task or delivery order contracts.... Further, the speed of adoption of innovative commercial solutions, like cloud, is facilitated by the use of these best practices.48

In October 2018, Google announced that it would not be submitting a bid for the contract, citing possible conflict with its corporate principles, along with DOD's plans to award the contract to a single vendor, among its reasons for withdrawing.49

GAO Bid Protests and U.S. Court of Federal Claims Case

Oracle America and IBM both filed pre-award bid protests with the Government Accountability Office (GAO) against the JEDI Cloud solicitation; GAO denied Oracle America's protests on November 14, 2018, and dismissed IBM's protests on December 11, 2018.50 Subsequently, Oracle America filed a bid protest lawsuit with the U.S. Court of Federal Claims.51

In filings associated with its bid protest lawsuit, Oracle America in part alleged that (1) the performance-based criteria include in the first step of the contract source selection process were "unduly restrictive and arbitrary" and (2) the JEDI Cloud acquisition process was unfairly skewed in favor of Amazon Web Services through potential organizational conflicts of interest associated with three former DOD employees, each of whom was involved to greater or lesser degrees in the early development of the program.52 Two of these former DOD employees were subsequently employed by Amazon Web Services.53 These claims attracted significant media and congressional attention.54

DOD investigations determined that Amazon Web Services had no unmitigated organizational conflicts of interest, and established that the actions of the individuals identified by Oracle America did not negatively impact the procurement or grant Amazon Web Services an unfair competitive advantage.55 However, the investigations did identify individual violations of ethical standards established by FAR Part 3.101-1, which directs government procurement activities to be "conducted in a manner above reproach," and for government employees to strictly "avoid … any conflict of interest or even the appearance of a conflict of interest in Government-contractor relationships."56 These findings were reportedly referred to the DOD Inspector General for further review.57

The U.S. Court of Federal Claims ruled against Oracle America in a July 12, 2019, decision, finding in part that sub-factor 1.2 of the sequentially considered performance-based criteria included in the Department's source selection process was "enforceable," and noting that as Oracle America admitted that its services did not "meet that criteria at the time of proposal submission, [the Court] conclude[s] that it cannot demonstrate prejudice as a result of other possible errors in the procurement process ."58

How Has DOD Responded to Industry Concerns?

Potential for Restriction of Future Competition

DOD officials have repeatedly described JEDI Cloud as a test model for DOD's future transition of legacy information technology systems to the cloud and have stressed that it is not intended to be a final solution.59 DOD CIO Dana Deasy has also highlighted the Department's lack of experience in deploying an enterprise-wide cloud solution, arguing that "starting with a number of firms while at the same time trying to build out an enterprise capability" would "double or triple" the technical complexity of the program.60 In the Department's May 2018 report to Congress, DOD indicated that the JEDI Cloud contract would include

multiple mechanisms to … maximize DOD's flexibilities going forward … the initial base ordering period is limited to 2 years, which will allow for sufficient time to validate the operational capabilities of JEDI Cloud and the DOD enterprise-wide approach. Option periods ... will only be exercised if doing so is the most advantageous method for fulfilling the DOD's requirements when considering the market conditions at the time of option exercise.61

As detailed in the JEDI Cloud RFP, offerors submitting a proposal to DOD were required to provide detailed transition and data portability plans, to include the complete set of processes and procedures necessary to extract all relevant data (such as system and network configurations, activity logs, source code, etc.) from the JEDI Cloud environment and systematically migrate to another cloud environment.62

Use of a Single-Award Contract

Section 2304a of Title 10, U.S. Code establishes a preference for making multiple awards for task or delivery order contracts, and separately prohibits DOD from awarding task or delivery order contracts exceeding $112 million (including all option periods) to a single source unless the head of the agency determines in writing that one or more of four specified circumstances apply.63

DOD detailed the rationale for using a single-award ID/IQ contract for the JEDI Cloud procurement, pursuant to 10 U.S.C.2304a(d)(4) and the provision's implementing FAR requirements, noting that while the FAR establishes a general preference for multiple award ID/IQ contracts, the FAR also establishes that a contracting officer must not use a multiple award approach if one or more of six conditions apply.64 Accordingly, the JEDI Cloud contracting officer determined that

- more favorable terms and conditions, including pricing, would be provided through a single award;

- the expected higher cost of administering multiple contracts "outweigh[ed] the expected benefits of making multiple awards" with a DOD-estimated additional cost of $500 million associated with administering multiple contracts; and

- multiple awards would not be in the best interests of DOD in this particular instance, as a multi-cloud environment could potentially "create seams between clouds that increase security risks … frustrate DOD's attempts to consolidate and pool data … [and could] exponentially increase the technical complexity require to realize the benefit of cloud technology."65

Together with the JEDI Cloud RFP, the Department also released its determination pursuant to 10 U.S.C. 2304a(d)(3), which prohibits DOD from awarding large task or delivery order contracts to a single source unless a senior official determines if at least one of four exceptions to the prohibition is present, that the JEDI Cloud contract provides only for firm-fixed price task orders or delivery orders for services for which prices are established in the contract for the specified tasks to be performed.66 However, the JEDI Cloud contract will also contain pricing related clauses intended to allow the Department to benefit from future marketplace competition driving commercial sector cloud services pricing downward, and to provide DOD with access to new cloud services as they become available to the commercial market

the contract automatically lower DOD's prices when the contractor's public commercial prices are lowered. The lower unit price is fixed. … [T]o achieve commercial parity over time, the contract contemplates adding new or improved cloud services to the contract. The new services clause requires … approval for the addition of new services and includes mechanisms to ensure that the fixed unit price for the new service cannot be higher than the price that is publicly available in the commercial marketplace in the continental United States. This same clause requires that, if a service … is eliminated from the Contractor's publicly available commercial catalog, the Contractor shall offer replacement service(s) … at a price no higher than, the service being eliminated. As with any other cloud offering, once the new service is added to the catalog, the unit price is fixed and cannot be changed without contracting officer approval.

The U.S. Court of Federal Claims questioned DOD's use of the 10 U.S.C. 2304a(d)(3) exception for firm fixed-price task or delivery orders in its determination in tandem with the JEDI Cloud contract's price adjustment clauses, noting that "prices for new, additional services to be identified and priced in the future, even if they may be capped in some cases, are not, by definition, fixed or established at the time of contracting."67

What Actions Has Congress Taken?

Legislative Action in the 115th Congress

Authorizations

Section 1064 of P.L. 115-232, the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for FY2019, required the DOD CIO to conduct activities supporting DOD's cloud adoption initiative:

- developing an approach to rapidly acquire advanced network capabilities, including software-defined networking, on-demand bandwidth, and aggregated cloud access gateways, through commercial service providers; and

- conducting an analysis of existing systems and applications that would be migrated to the JEDI Cloud environment.68

Section 1064 required the DOD CIO to submit a report on the current status and anticipated implementation of DOD's cloud adoption initiative, and limited the use of authorized FY2019 funds for DOD's cloud adoption until the required report's submission. The Department submitted the required report in January 2019.69

Section 1064 further required DOD to complete an assessment to determine whether an information system or application is already, or can and would be cloud-hosted, prior to approving any new system or application for development or modernization. Finally, and pointedly, Section 1064 requires the Deputy Secretary of Defense to "ensure that the acquisition approach of the Department [for the JEDI Cloud procurement] continues to follow the [FAR] with respect to competition." In the conference report accompanying the FY2019 NDAA (H.Rept. 115-874), the conferees

emphasize the importance of modernizing networks by adopting advancing [sic] commercial capabilities to achieve DOD's cloud transition and enterprise efficiency goals. … The conferees encourage the Department to continue to ensure that cloud technologies are technically suitable, appropriately tested for security and reliability, and integrated with other DOD information technology efforts so as to optimize effective and efficient procurement of such technologies and services and their performance in support of DOD missions. Finally, the conferees note that although transparency and information sharing by the Department on the Cloud Initiative has slightly improved, it continues to be insufficient for conducting congressional oversight. The conferees expect the Department to improve communication with Congress on this issue and will consider additional legislation if an improvement is not seen.70

Appropriations

Section 8137 of P.L. 115-245, which provided FY2019 DOD appropriations, prevented the obligation or expenditure of FY2019 funds to "migrate data and applications to the proposed [JEDI] ... cloud computing services" until 90 days after the Secretary of Defense submitted (1) a plan to establish a DOD-wide budget accounting system for funds requested and expended for cloud services, as well as funds requested and expended to migrate to a cloud environment; and (2) a detailed description of DOD's strategy to implement enterprise-wide cloud computing to the congressional defense committees.71

The Department submitted the required report in January 2019.72

Proposed Legislative Action in the 116th Congress

Authorizations

The House Armed Services Committee report (H.Rept. 116-120) accompanying the House-passed FY2020 NDAA (H.R. 2500), includes the committee's commendation for DOD's cloud strategy

Cloud infrastructure, such as [JEDI], allows users to access information from anywhere at any time, effectively removing the need for the user to be in the same physical location as the hardware that stores the data. … The ability of cloud infrastructure to scale ensures that the Department efficiently manages and modernizes its information technology needs and demands. The committee endorses the Department's strategy and concept for a flexible enterprise cloud architecture that enshrines the need and value for both general purpose and fit-for-purpose cloud solutions through a multi-cloud, multi-vendor approach.73

Section 1035 of S. 1790, the Senate-passed FY2020 NDAA, would specify that the DOD CIO and the DOD Chief Data Officer, in consultation with the J6 Command, Control, Communications, and Computers (C4) and Cyber Directorate of the Joint Staff and the DOD CMO, must develop and issue DOD-wide policy and implementing instructions regarding the transition of data and applications to the cloud. Such a policy would be required to "dramatically improve support to operational missions and management processes, including by the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies."

In its "Items of Special Interest" for Title XVI ("Strategic Programs, Cyber, and Intelligence Matters"), the Senate Armed Services Committee report (S.Rept. 116-48) for the FY2020 NDAA notes the committee's understanding for the "potential of commercial clouds to provide cost-effective, state-of-the-art capabilities," but highlights the committee's view that tDOD must be able to "conduct cybersecurity testing" for commercial cloud products and services, "including threat-realistic cyberattacks, to assess the cybersecurity of the Department's data and the cyber defense response to the attacks."74 The report directs the Secretary of Defense to provide a related briefing to the House and Senate Armed Services Committees, and recommends the inclusion of information regarding independent cyber assessments for commercially provided infrastructure in Director of Operational Test and Evaluation annual reports.75

Appropriations

The House Appropriations Committee report (H.Rept. 116-84) accompanying H.R. 2968, the House-passed FY2020 Department of Defense appropriations act, highlights the committee's skepticism of DOD's pursuit of a "single vendor contract strategy" for the JEDI Cloud procurement

The Committee continues to be concerned with this approach given the rapid pace of innovation in the industry and that this approach may lock the [DOD] into a single provider for potentially as long as ten years. Since the [DOD] adopted its single vendor strategy in 2017, other federal agencies … have decided to pursue a multiple vendor cloud strategy as recommended by the [OMB] "Cloud Smart" strategy … the Committee believes the [DOD] is deviating from established OMB policy and industry best practices, and may be failing to implement a strategy that lowers costs and fully supports data innovation for the warfighter.76

Accordingly, the House Appropriations Committee report would direct that no funds may be obligated or expended to migrate data and applications to the JEDI Cloud until the DOD CIO provides a report to the congressional defense committees expanding on the Department's plans to transition to a "multi-cloud, multi-vendor" environment.77 The DOD CIO would be directed to provide a listing of anticipated contracting opportunities for the acquisition of commercial cloud services by the Department over the next two years, to include specified elements such as planned contract type and structure; whether the procurement is anticipated to be conducted as a full and open competition or as a sole source award; the estimated timeframe for the release of related solicitations; and the estimated maximum contract value and period of performance, including option periods. The DOD CIO would also be directed to submit quarterly reports on the implementation of its cloud adoption and implementation strategy to the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, beginning 30 days after the enactment of a FY2020 defense appropriations act.

Other Congressional Actions

Various Members of Congress have also individually and collectively advocated for the Department to take certain actions relating to the JEDI Cloud procurement. For example, some Members have urged DOD to delay or postpone awarding the JEDI Cloud contract to accommodate an alternate acquisition strategy, or the conclusion of the DOD Inspector General's investigation into the potential violations of ethical standards by former DOD employees.78 Other Members have supported DOD's acquisition strategy, advocating for the Department to award the JEDI Cloud contract as soon as possible.79

Considerations for Congress

Significant attention has focused on DOD's intent to award the JEDI Cloud contract to a single company. Some observers contend that an initial single award appears to contradict broader federal cloud computing implementation guidance and industry best practices that stress the importance of multi-cloud solutions.80 Other experts point to the implementation approaches identified by DOD's Cloud Strategy as an indication that the Department expects the JEDI Cloud to serve certain enterprise-wide functions, performing as one component of a broader multi-cloud, multi-vendor system.81 Some observers, however, have concluded that the JEDI Cloud requirements are misaligned with DOD's Cloud Strategy, and have urged the Department to rescind and revise the JEDI Cloud RFP.82

Those opposed to DOD's use of a single-award contract for the JEDI Cloud program have suggested that a single-award contract could potentially restrict future competition for enterprise-wide DOD IaaS and PaaS cloud services.83 Supporters of DOD's approach argue that the JEDI Cloud program's requirement for offerors to develop platform-agnostic applications and data schema suggests that the Department will be well equipped to migrate from any service environment developed under the JEDI Cloud contract to another such environment.84 Potential considerations for Congress concerning the ongoing JEDI Cloud acquisition process, as well as any follow-on efforts, include the following issues.

Oversight of Option Exercise for the JEDI Cloud Contract

As DOD has indicated that it believes the initial two-year base ordering period is sufficient time to validate the JEDI Cloud test model, Congress may consider directing DOD to provide detailed rationale and justification for any extension of the JEDI Cloud contract prior to the exercise of contract options.85 At the time of option exercise, Congress may also consider directing the Department to report on any notable lessons learned or challenges experienced in the execution of the JEDI Cloud contract. As emphasized in the conference report accompanying the FY2019 NDAA (H.Rept. 115-874), Congress may also wish to monitor the extent to which the Department has "improved communication with Congress" to enable sufficient congressional oversight of the JEDI Cloud program and DOD's cloud adoption initiative.86

Procurement Integrity

The U.S. Court of Federal Claims decision agreed with the Department's finding that the actions of the individuals identified by Oracle America in its bid protest lawsuit did not negatively impact the procurement or grant Amazon Web Services an unfair competitive advantage. However, the individual violations of ethical standards for federal employees involved in the acquisition of goods and services for the U.S. government—which generated the appearance of unresolved conflicts of interest—identified by DOD in the course of its investigations delayed the JEDI Cloud procurement process.87

The FAR directs government procurement activities to be "conducted in a manner above reproach," and for government employees to strictly "avoid … even the appearance of a conflict of interest."88 Congress may accordingly consider directing DOD to examine the current emphasis on ethical conduct and the Procurement Integrity Act in education, training, and qualification requirements for designated acquisition positions—as well as considering the need to include equivalent training for DOD servicemembers and civilian employees outside of the defense acquisition workforce who may provide technical expertise or other support for procurement programs—and determine what, if any, changes should be made to associated curriculum and certification requirements.89

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Deputy Secretary of Defense, "Accelerating Enterprise Cloud Adoption," September 13, 2017, memorandum, as distributed with Washington Headquarters Service, "DOD Cloud: Request for Information," solicitation number DOD_Cloud_RFI, updated October 31, 2017, available at https://go.usa.gov/xydjT. |

| 2. |

Department of Defense Press Operations, "Accelerating Enterprise Cloud Adoption," news release no. NR-049-18, February 15, 2018, available at https://go.usa.gov/xymbk. |

| 3. |

Cloud computing, as formally defined by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), refers to a model for the provision of "ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications, and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service provider interaction." NIST defines five essential characteristics of a cloud: on-demand self-service, broad network access, resource pooling, rapid extensibility, and measured service. See NIST Special Publication 800-145, "The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing," September 2011, available at https://go.usa.gov/xydj9. |

| 4. |

See discussion of "Redefining Cloud Computing" in Office of the Federal Chief Information Officer, "Federal Cloud Computing Strategy: From Cloud First to Cloud Smart," 2019 final strategy, available at https://cloud.cio.gov/strategy/. |

| 5. |

See for example U.S. Chief Information Officer, "Federal Cloud Computing Strategy," February 8, 2011, available at https://go.usa.gov/xyMFy and CRS Report R42604, Department of Defense Implementation of the Federal Data Center Consolidation Initiative: Implications for Federal Information Technology Reform Management, by Patricia Moloney Figliola and Eric A. Fischer. |

| 6. |

See CRS Report R42887, Overview and Issues for Implementation of the Federal Cloud Computing Initiative: Implications for Federal Information Technology Reform Management, by Patricia Moloney Figliola and Eric A. Fischer. The 2011 "Cloud First" strategy was supplemented in 2018 by the "Cloud Smart" strategy, which provides implementation guidance for agencies looking to adopt cloud-based services. |

| 7. |

Department of Defense, "Combined Congressional Report: 45-Day Report to Congress on JEDI Cloud Computing Services Request for Proposal and 60-Day Report to Congress on a Framework for all Department Entities to Acquire Cloud Computing Services," pages 7-8, as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package (Washington Headquarters Service, "JEDI Cloud RFP," solicitation number HQ003418R0077 JEDI_CLOUD_RFP, updated October 9, 2018, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ). |

| 8. |

Deputy Secretary of Defense, "DoD Cloud Update," June 22, 2018, memorandum, available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/062218_shanahan_deasy_memo.pdf. |

| 9. |

Department of Defense, "DOD Cloud Strategy," December 2018, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uP. |

| 10. |

Department of Defense, "DOD Cloud Strategy," December 2018. Prior to the issuance of this document, DOD had last issued a substantive cloud strategy document in 2012—the 2012 DOD cloud strategy document broadly paralleled the 2011 OMB "Cloud First" strategy. See Department of Defense Chief Information Officer, "Cloud Computing Strategy," July 2012. |

| 11. |

Department of Defense, "DOD Cloud Strategy," December 2018, p. i. |

| 12. |

Department of Defense, "DOD Cloud Strategy," December 2018, p. A-1. |

| 13. |

Department of Defense, "DOD Cloud Strategy," December 2018, p. A-2; see also General Services Administration, "Defense Enterprise Office Solution (DEOS)," solicitation number 47QTCA-19-Q-0001, updated February 11, 2019, available at https://go.usa.gov/xyXya and DISA, "milCloud 2.0," available at https://go.usa.gov/xyXyC. |

| 14. |

FAR Part 39 and FAR Part 12, both available at https://go.usa.gov/xydkj. |

| 15. |

Federal Chief Information Officer, Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President, "Security Authorization of Information Systems in Cloud Computing Environments," memorandum, December 8, 2011, available at https://go.usa.gov/xyXyc. See also Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program, available at https://www.fedramp.gov/. |

| 16. |

Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement Subpart 239.76, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy5ae. |

| 17. |

Department of Defense, "Cloud Computing Security Requirements Guide," version 1, release 3, March 6, 2017, currently publicly available at https://iasecontent.disa.mil/cloud/SRG/index.html. DOD cloud computing security guidance is being transitioned to a new "DOD Cyber Exchange" website maintained by DISA; some associated guidance was not publicly accessible as of June 12, 2019. See DISA, "DOD Cyber Exchange – Public," available at https://public.cyber.mil/. |

| 18. |

See FAR Part 2.101. The authorizing official, as described in DOD Instruction 8510.01 ("Risk Management Framework (RMF) for DoD Information Technology (IT)," incorporating change 2, July 28, 2017), may grant exceptions to this requirement. If a contractor has requested authorization to store government data outside of the U.S. or outlying areas of the U.S., the contracting officer must provide written notification of such authorization to the contractor. See also 5.2.1, "Jurisdiction/ Location Requirements," DOD Cloud Computing Security Requirements Guide, version 1, release 3, March 6, 2017. |

| 19. |

Department of Defense Instruction 5000.74, "Defense Acquisition of Services," incorporating change 2, August 31, 2018, enclosure 7, pages 33-34, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uT. See also Jo Anna Bennerson, "Navigating the U.S. Federal Government Agency ATO Process for IT Security Professionals," ISACA Journal, volume 2, 2017, available at https://www.isaca.org/Journal/archives/2017/Volume-2/Pages/navigating-the-us-federal-government-agency-ato-process-for-it-security-professionals.aspx and Department of Defense Instruction 8510.01, "Risk Management Framework (RMF) for DOD Information Technology (IT)," incorporating change 2, July 28, 2017, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uD. |

| 20. |

Department of Defense Chief Information Officer, "Updated Guidance on the Acquisition and Use of Commercial Cloud Computing Services," memorandum, December 15, 2014, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2u5. |

| 21. |

See CRS Report R45349, The 2018 National Defense Strategy: Fact Sheet, by Kathleen J. McInnis and CRS Insight IN10842, The 2017 National Security Strategy: Issues for Congress, by Kathleen J. McInnis. |

| 22. |

Department of Defense, "Combined Congressional Report: 45-Day Report to Congress on JEDI Cloud Computing Services Request for Proposal and 60-Day Report to Congress on a Framework for all Department Entities to Acquire Cloud Computing Services," page 3. |

| 23. |

Joint Requirements Oversight Council, "Joint Characteristics and Considerations for Accelerating to Cloud Architectures and Services," memorandum JROCM 135-17, December 22, 2017. |

| 24. |

Department of Defense Chief Information Officer, "JEDI Cloud Request for Proposals," July 26, 2018, memorandum, as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ); see also Department of Defense Press Operations, "Contract Milestone Brings Enterprise Cloud Solution One Step Closer to Warfighter," news release no. NR-225-18, July 26, 2018, available at https://go.usa.gov/xyXmS. |

| 25. |

Declaration of Lieutenant General Bradford J. Shwedo, June 19, 2019, in Oracle America, Inc. v. the United States, U.S. Court of Federal Claims (No. 18-1880C). See also Lauren C. Williams, "JEDI Award Expected in August," FCW, June 25, 2019, available at https://fcw.com/articles/2019/06/25/jedi-award-august-williams.aspx and Deputy Secretary of Defense, "Establishment of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center," memorandum dated June 27, 2018, and CRS Report R45178, Artificial Intelligence and National Security, by Kelley M. Sayler. |

| 26. |

Deputy Secretary of Defense, "Accelerating Enterprise Cloud Adoption," September 13, 2017, memorandum, as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFI package (Washington Headquarters Service, "DOD Cloud: Request for Information," solicitation number DOD_Cloud_RFI, updated October 31, 2017, available at https://go.usa.gov/xydjT). |

| 27. |

Section 901 of the FY2017 NDAA split the office of the USD(AT&L) into two separate offices: the office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (USD A&S) and the office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USD R&E). |

| 28. |

DIUx became DIU in August 2018. See also Deputy Secretary of Defense, "Accelerating Enterprise Cloud Adoption," September 13, 2017, memorandum. |

| 29. |

Deputy Secretary of Defense, "Accelerating Enterpise Cloud Adoption Update," January 4, 2018, memorandum, available at http://federalnewsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/010418_shanahan_cloud_memo.pdf. |

| 30. |

Deputy Secretary of Defense, "DOD Cloud Update," June 22, 2018, memorandum, available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/062218_shanahan_deasy_memo.pdf. |

| 31. |

Deputy Secretary of Defense, "DOD Cloud Update," June 22, 2018, memorandum; see also Washington Headquarters Service, "Cloud Computing Program Office Support Services for DOD Chief Information Office," solicitation number HQ0034-19-R-0146, updated April 18, 2019, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy5YG. |

| 32. |

Washington Headquarters Service, "DOD Cloud: Request for Information," solicitation number DOD_Cloud_RFI, updated October 31, 2017, available at https://go.usa.gov/xydjT; Washington Headquarters Service, "DRAFT DOD JEDI CLOUD RFP," solicitation number HQ003418R0077-JEDI_Cloud_DRAFT_RFP, updated July 26, 2018, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uv. |

| 33. |

Department of Defense Press Operations, "Contract Milestone Brings Enterprise Cloud Solution One Step Closer to Warfighter," news release no. NR-225-18, July 26, 2018, available at https://go.usa.gov/xyXp7; see also Washington Headquarters Service, "JEDI Cloud RFP," solicitation number HQ003418R0077 JEDI_CLOUD_RFP, updated October 9, 2018, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ) |

| 34. |

Frank Konkel, "Pentagon Says No JEDI Conflict, Narrows Field to AWS and Microsoft," Nextgov, April 10, 2019, available at https://www.nextgov.com/it-modernization/2019/04/pentagon-says-no-jedi-conflict-narrows-field-aws-and-microsoft/156216/. |

| 35. |

Jason Miller and Jared Serbu, "DOD's JEDI Saga Continues with Government, AWS Returning Fire in Latest Protest Filing," Federal News Network, June 21, 2019, available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/contractsawards/2019/06/dods-jedi-saga-continues-with-government-aws-returning-fire-in-latest-protest-filing/. See also Frank R. Konkel, "Pentagon Aims to Award JEDI Cloud Contract in August," DefenseOne, June 26, 2019, available at https://www.defenseone.com/technology/2019/06/pentagon-targets-august-jedi-award/157995/. |

| 36. |

Aaron Gregg and Josh Dawsey, "After Trump Cites Amazon Concerns, Pentagon Reexamines $10 Billion JEDI Cloud Contract Process," The Washington Post, August 1, 2019, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/08/01/after-trump-cites-amazon-concerns-pentagon-re-examines-billion-jedi-cloud-contract-process/. See also Ryan Tracy, "Defense Secretary Mark Esper to Review JEDI Cloud Contract," The Wall Street Journal, August 1, 2019, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/defense-secretary-esper-to-review-jedi-cloud-contract-11564694211. |

| 37. |

Department of Defense Press Operations, "Department of Defense News Briefing on the President's Fiscal Year 2020 Defense Budget," transcript, March 12, 2019, available at https://go.usa.gov/xyXdw. |

| 38. |

JEDI Cloud RFP, "Combined Synopsis/Solicitation for Commercial Items, "as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package updated on October 9, 2018, available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ. |

| 39. |

U.S. Congress, Deficit Reduction Act of 1984, conference report to accompany H.R. 4170, 98th Cong., 2nd sess., June 23, 1984, H.Rept. 98-861, p. 1422. |

| 40. |

Full and open competition is required by 10 U.S.C. 2304 and 41 U.S.C. 3301; both provisions require, with certain limited exceptions, that contracting officers promote and provide for full and open competition in soliciting offers and awarding government contracts. 41 U.S.C. 113 defines a capable prospective contractor as an individual or entity that (1) has or can obtain adequate financial resources to perform the contract; (2) is able to comply with the required or proposed delivery or performance schedule; (3) has a satisfactory performance record; (4) has a satisfactory record of integrity and business ethics; (5) has or can obtain the necessary organization, experience, accounting and operational controls, and technical skills to provide the goods or services to be delivered under contract; (6) has or can obtain any necessary production, construction, and technical equipment and facilities; and (7) is otherwise qualified and eligible to receive an award under applicable laws and regulations. |

| 41. |

JEDI Cloud RFP, "Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI) Cloud Statement of Objectives (SOO)," page 2, as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package updated on October 9, 2018, and available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ. See also Cloud Computing Program Office, "Department of Defense Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI) Cloud Program Cyber Security Plan," version 1.0, June 11, 2018, as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package. |

| 42. |

JEDI Cloud RFP, "Combined Synopsis/Solicitation for Commercial Items," page 88, as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package updated on October 9, 2018, and available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ. |

| 43. |

JEDI Cloud RFP, "Combined Synopsis/Solicitation for Commercial Items," p. 89. |

| 44. |

JEDI Cloud RFP, "Combined Synopsis/Solicitation for Commercial Items," pp 74-77. |

| 45. |

JEDI Cloud RFP, "Combined Synopsis/Solicitation for Commercial Items," pp. 78-82. |

| 46. |

Department of Defense, "Program Manager RFP Release Letter," as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ. |

| 47. |

In 2018, a draft of the Federal Cloud Computing Strategy stated that "[t]his plan will be technology-neutral, and will consider vendor-based solutions, agency-hosted solutions, inter- and intra-agency shared services, multi-cloud, and hybrid solutions as appropriate." Office of the Federal Chief Information Officer, "Federal Cloud Computing Strategy: From Cloud First to Cloud Smart," 2018 draft strategy proposal released for comment, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20181213073907/https://cloud.cio.gov/strategy/. This language is not included in the final draft of the Cloud Smart strategy, released in 2019, which instead notes that "industries that are leading in technology innovation have also demonstrated that hybrid and multi-cloud environments can be effective and efficient for managing workloads," and stresses that "agencies should be equipped to evaluate their options based on their service and mission needs, technical requirements, and existing policy limitations." See Office of the Federal Chief Information Officer, "Federal Cloud Computing Strategy: From Cloud First to Cloud Smart," 2019 final strategy, available at https://cloud.cio.gov/strategy/; White House Office of Management and Budget, "OMB Announces Cloud Smart Proposal," statement issued September 24, 2018, available at https://go.usa.gov/xyME6; and Derek B. Johnson, "OMB Finalizes 'Cloud Smart,'" FCW, June 25, 2019, available at https://fcw.com/articles/2019/06/25/cloud-smart-johnson.aspx. |

| 48. |

IT Alliance for Public Sector, letter to the House and Senate Armed Services Committees Chairmen and Ranking Members, April 30, 2018, available at https://www.nextgov.com/media/gbc/docs/pdfs_edit/043018fk2ng.pdf. |

| 49. |

Naomi Nix, "Google Drops Out of Pentagon's $10 Billion Cloud Competition," Bloomberg, October 8, 2018, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-08/google-drops-out-of-pentagon-s-10-billion-cloud-competition. |

| 50. |

See CRS Report R45080, Government Contract Bid Protests: Analysis of Legal Processes and Recent Developments, by David H. Carpenter and Moshe Schwartz; see also GAO Bid Protest Docket, Solicitation Number HQ0034-18-R-0077, available at https://www.gao.gov/legal/bid-protests/ and statement of Sam Gordy, "JEDI: Why We're Protesting," blog post, IBM Government and Regulatory Affairs, available at https://www.ibm.com/blogs/policy/jedi-protest/. |

| 51. |

Aaron Gregg, "GAO Axes IBM's Bid Protest, Teeing Up a Court Battle Over Pentagon's $10 Billion Cloud Effort," The Washington Post, December 11, 2018, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2018/12/12/gao-axes-ibms-bid-protest-teeing-up-court-battle-over-pentagons-billion-cloud-effort/. |

| 52. |

Supplemental Bid Protest Complaint, May 7, 2019, in Oracle America, Inc. v. the United States, U.S. Court of Federal Claims (No. 18-1880C), available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/JEDI-Oracle-filing-050819.pdf. |

| 53. |

See for example Aaron Gregg and Christian Davenport, "Pentagon to Review Amazon Employee's Influence Over $10 Billion Government Contract," The Washington Post, January 24, 2019, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/01/24/pentagon-review-amazon-employees-influence-over-billion-government-contract/, Karen Weise and Thomas Kaplan, "Giant Military Contract Has a Hitch: A Little-Known Entrepreneur," The New York Times, March 20, 2019, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/20/technology/military-contract-deap-ubhi.html, and Jason Miller, "New Details from Oracle Point to Former Navy Official as Third Executive Caught Up in JEDI Controversy," Federal News Network, May 13, 2019, available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/reporters-notebook-jason-miller/2019/05/new-details-from-oracle-point-to-former-navy-official-as-third-executive-caught-up-in-jedi-controversy/. |

| 54. |

See for example Kevin Baron et al., "Someone Is Waging a Secret War to Undermine the Pentagon's Huge Cloud Contract," DefenseOne, August 20, 2018, available at https://www.defenseone.com/technology/2018/08/someone-waging-secret-war-undermine-pentagons-huge-cloud-contract/150685/; Frank Konkel, "Congressmen Call for IG Investigation into JEDI Cloud Contract," Nextgov, October 23, 2018, available at https://www.nextgov.com/it-modernization/2018/10/congressmen-call-ig-investigation-jedi-cloud-contract/152235/; and Jason Miller, "Oracle Sends 8 Letters to Lawmakers Asking for Stronger Oversight of DOD's JEDI Program," Federal News Network, May 6, 2019, available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/reporters-notebook-jason-miller/2019/05/oracle-sends-8-letters-to-lawmakers-asking-for-stronger-oversight-of-dods-jedi-program/. See also Senator Chuck Grassley, "Grassley Presses Defense Department on Potential Conflicts in Massive Cloud Computing Procurement," news release, April 11, 2019, available at https://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/grassley-presses-defense-department-potential-conflicts-massive-cloud-computing and Senator Elizabeth Warren, Twitter post, June 4, 2019, available at https://twitter.com/SenWarren/status/1135997831020470273. |

| 55. |

Defendant's Cross-Motion for Judgement, June 11, 2019, in Oracle America, Inc. v. the United States, U.S. Court of Federal Claims (No. 18-1880C), available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/061819_jedi_government_motion_for_judgment.pdf |

| 56. |

Defendant's Cross-Motion for Judgement, June 11, 2019, in Oracle America, Inc. v. the United States, U.S. Court of Federal Claims (No. 18-1880C). See also FAR Part 3.101-1, "Standards of Conduct: General," available at https://www.acquisition.gov/content/3101-1-general. |

| 57. |

Frank Konkel, "Pentagon Says No JEDI Conflict, Narrows Field to AWS and Microsoft," Nextgov, April 10, 2019, available at https://www.nextgov.com/it-modernization/2019/04/pentagon-says-no-jedi-conflict-narrows-field-aws-and-microsoft/156216/. |

| 58. |

Jared Serbu, "Pentagon Prevails in Legal Challenge to its JEDI Cloud Contract," Federal News Network, July 12, 2019, available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/contracting/2019/07/pentagon-prevails-in-legal-challenge-to-its-jedi-cloud-contract/. See also Court Order, July 12, 2019, in Oracle America Inc. v. the United States, U.S. Court of Federal Claims (No. 18-1880C), available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/071219_JEDI_ruling.pdf. |

| 59. |

Scott Maucione, "Shanahan: DOD's JEDI is a 'Pathfinder' for Future DOD Cloud Computing Contracts," Federal News Network, April 24, 2018, available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/contracting/2018/04/dod-cloud-contract-a-pathfinder-and-only-accounts-for-16-percent-of-services-needed/. |

| 60. |

Aaron Gregg and Christian Davenport, "Meet the Man at the Center of the High-Stakes, Winner-Take-All $10 Billion Pentagon cloud Contract Called JEDI," The Washington Post, October 2, 2018, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2018/10/02/meet-man-center-high-stakes-winner-take-all-billion-pentagon-cloud-contract-called-jedi/. |

| 61. |

Department of Defense, "Combined Congressional Report: 45-Day Report to Congress on JEDI Cloud Computing Services Request for Proposal and 60-Day Report to Congress on a Framework for all Department Entities to Acquire Cloud Computing Services," page 11. |

| 62. |

Department of Defense, "Contract Data Requirements List: Portability Plan (A007)," as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ. |

| 63. |

DOD adjusted the $100 million threshold specified in 10 U.S.C. 2304a(d)(3) to $112 million in accordance with 41 U.S.C. 1908, which allows periodic adjustment of statutory acquisition-related dollar thresholds to accommodate inflation. The four circumstances in which DOD may award a task or delivery order contract exceeding $112 million to a single source are situations where (1) the task or delivery orders expected under the contract are so integrally related that only a single source can efficiently perform the work; (2) the contract provides only for firm fixed-price task or delivery orders for products for which unit prices are established in the contract or services for which prices are established in the contract for the specific tasks to be performed; (3) only one source is qualified and capable of performing the work at a reasonable price to the government; or (4) because of exceptional circumstances it is necessary in the public interest to award the contract to a single source. |

| 64. |

Defendant's Cross-Motion for Judgement, June 11, 2019, in Oracle America, Inc. v. the United States, U.S. Court of Federal Claims (No. 18-1880C); see also FAR Part 16.504(c)(1)(ii)(B), which specifies that a contracting officer must not use the multiple award approach if (1) only one contractor is capable of proving performance at the level of quality required because the supplies or services are unique or highly specialized; (2) based on the contracting officer's knowledge of the market, more favorable terms and conditions, including pricing, will be provided if a single award is made; (3) the expected cost of administration of multiple contracts outweighs the expected benefits of making multiple awards; (4) the projected task orders are so integrally related that only a single contractor can reasonably perform the work; (5) the total estimated value of the contract is less than the simplified acquisition threshold (generally $250,000); or (6) multiple awards would not be in the best interest of the government. |

| 65. |

Defendant's Cross-Motion for Judgement, June 11, 2019, in Oracle America, Inc. v. the United States, U.S. Court of Federal Claims (No. 18-1880C). |

| 66. |

Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, "Determination and Findings for Authority to Award a Task Order Contract to a Single Source," pages 2-3, as distributed with the JEDI Cloud RFP package available at https://go.usa.gov/xy2uQ. |

| 67. |

Opinion, July 26, 2019, in Oracle America, Inc. v. the United States, U.S. Court of Federal Claims (No. 18-1880C). The U.S. Court of Federal Claims upheld the contracting officer's decision that multiple awards were not allowed under 10 U.S.C 2304a(d)(4)and FAR Part 16.504. In doing so, the U.S. Court of Federal Claims highlighted the "tension" between both findings, noting that this "peculiar state of affairs is an artifact of a code section which is a mixture, rather than an alloy, of various pieces of legislation." |

| 68. |

10 U.S.C. 2223a note. |

| 69. |

Department of Defense, "DOD Cloud Initiative Report," January 2019, as provided to the Congressional Research Service. |

| 70. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Armed Services, John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, conference report to accompany H.R. 5515, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., July 25, 2018, H.Rept. 115-874 (Washington: GPO, 2018), pp. 948-949. |

| 71. |

In H.Rept. 115-952, the conferees noted that "cloud computing, if implemented properly, will have far reaching benefits for improving the efficiency of day-to-day operations of the Department of Defense, as well as enabling new military capabilities critical to maintaining a tactical advantage over adversaries." See U.S. Congress, House Committee on Appropriations, Department of Defense for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2019 and for Other Purposes, conference report to accompany H.R. 6157, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., September 13, 2018, H.Rept. 115-952 (Washington: GPO, 2018), pp. 154-155. |

| 72. |

Department of Defense, "DOD Cloud Initiative Report," January 2019, as provided to the Congressional Research Service. |

| 73. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Armed Services, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, committee report to accompany H.R. 2500, 116th Cong., 1st sess., June 19, 2019, H.Rept. 116-120 (Washington: GPO, 2019), p. 279. |

| 74. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Armed Services, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, committee report to accompany S. 1790, 116th Cong., 1st sess., June 11, 2019, S.Rept. 116-48 (Washington: GPO, 2019), p. 325. |

| 75. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Armed Services, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, committee report to accompany S. 1790, 116th Cong., 1st sess., June 11, 2019, S.Rept. 116-48 (Washington: GPO, 2019), p. 325. |

| 76. |

The House passed H.R. 2968 as reported as Division C of H.R. 2740 on June 19, 2019. See also U.S. Congress, House Committee on Appropriations, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2020, committee report to accompany H.R. 2968, 116th Cong., 1st sess., May 23, 2019, H.Rept. 116-84 (Washington: GPO, 2019), pp. 11-12. |

| 77. |

As referenced in Department of Defense, "DOD Cloud Strategy," December 2018, p. i. See also Department of Defense Chief Information Officer, "DOD Cloud Initiative Report," January 2019 report to the congressional defense committees, page 5. |

| 78. |

See for example Senator Marco Rubio, "Rubio Urges Bolton to Delay DOD JEDI Cloud Award," press release, July 11, 2019, available at https://go.usa.gov/xyeEZ; activity by Representative Steve Womack as reported by Ben Brody and Naomi Nix, "Lawmakers Press Trump, Pentagon Over $10 Billion JEDI Cloud Deal," Bloomberg, July 8, 2019, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-07-08/lawmakers-press-trump-pentagon-over-10-billion-jedi-cloud-deal; Senator Ron Johnson, letter to the Honorable Dr. Mark T. Esper dated June 24, 2019, available at https://go.usa.gov/xywmr; and Alayna Treene, "GOP Congressmen Pressure Trump to Delay $10 Billion Defense Contract," Axios, July 25, 2019, available at https://www.axios.com/republican-congressmen-trump-delay-amazon-defense-contract-801872bc-b30b-41a7-81c6-d9ad7eddc94b.html. |

| 79. |