The Department of Defense Acquisition Workforce: Background, Analysis, and Questions for Congress

Congress and the executive branch have long been frustrated with waste, mismanagement, and fraud in defense acquisitions and have spent significant resources seeking to reform and improve the process. Efforts to address wasteful spending, cost overruns, schedule slips, and performance shortfalls have continued unabated, with more than 150 major studies on acquisition reform since the end of World War II. Many of the most influential of these reports have articulated improving the acquisition workforce as the key to acquisition reform. In recent years, Congress and the Department of Defense (DOD) have sought to increase the size and improve the capability of this workforce.

The acquisition workforce is generally defined as uniformed and civilian government personnel, who are responsible for identifying, developing, buying, and managing goods and services to support the military. According to DOD, as of December 31, 2015, the defense acquisition workforce consisted of 156,457 personnel, of which approximately 90% (141,089) were civilian and 10% (15,368) were uniformed.

Between FY1989 and FY1999, the acquisition workforce decreased nearly 50% to a low of 124,000 employees. This decline is attributable in large part to a series of congressionally mandated reductions between FY1996 and FY1999. These cuts reflected Congress’s then-view that the acquisition workforce size was not properly aligned with the acquisition budget and the size of the uniformed force. A number of analysts believe that these cuts led to shortages in the number of properly trained, sufficiently talented, and experienced personnel, which in turn has had a negative effect on acquisitions.

In an effort to rebuild the workforce, between FY2008 and the first quarter of FY2016, the acquisition workforce grew by 24% (30,434 employees). According to DOD, the Department accomplished its strategic objective to rebuild the workforce. Officials stated that certification and education levels have improved significantly: currently, over 96% of the workforce meet position certification requirements and 83% have a bachelor’s degree or higher. In addition, DOD officials stated that they have positioned the workforce for long-term success by strengthening early and mid-career workforce cohorts.

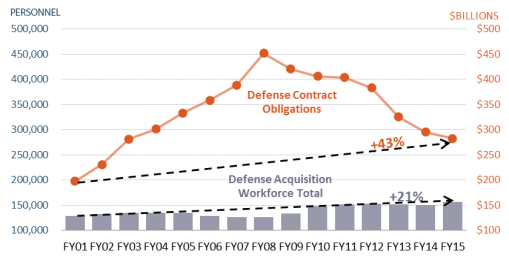

The increase in the size of the workforce has not kept pace with increased acquisition spending. According to DOD, from 2001 to 2015, the acquisition workforce increased by some 21%. Over the same period, contract obligations (adjusted for inflation) increased approximately 43%. While this increase in spending does not necessarily argue for increasing the size of the workforce, according to DOD officials, the increased spending has also corresponded to an increase in the workload and complexity of contracting. Four congressional efforts to improve the acquisition workforce are:

the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (P.L. 101-510),

hiring and pay flexibilities enshrined in numerous sections of law,

the Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund (P.L. 110-181), and

strategic planning for the acquisition workforce (P.L. 111-84).

These four efforts seek to enhance the training, recruitment, and retention of acquisition personnel by, respectively, establishing (1) professional development requirements, (2) monetary incentives and accelerated hiring, (3) dedicated funding for workforce improvement efforts, and (4) formal strategies to shape and improve the acquisition workforce.

The Department of Defense Acquisition Workforce: Background, Analysis, and Questions for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- How Is the Acquisition Workforce Defined?

- What Is the Size and Composition of the Acquisition Workforce?

- Trends in Acquisition Workforce Size

- Acquisition Workforce Size and Defense Contract Spending

- Congressional Efforts to Improve the Acquisition Workforce

- Potential Questions for Congress

Summary

Congress and the executive branch have long been frustrated with waste, mismanagement, and fraud in defense acquisitions and have spent significant resources seeking to reform and improve the process. Efforts to address wasteful spending, cost overruns, schedule slips, and performance shortfalls have continued unabated, with more than 150 major studies on acquisition reform since the end of World War II. Many of the most influential of these reports have articulated improving the acquisition workforce as the key to acquisition reform. In recent years, Congress and the Department of Defense (DOD) have sought to increase the size and improve the capability of this workforce.

The acquisition workforce is generally defined as uniformed and civilian government personnel, who are responsible for identifying, developing, buying, and managing goods and services to support the military. According to DOD, as of December 31, 2015, the defense acquisition workforce consisted of 156,457 personnel, of which approximately 90% (141,089) were civilian and 10% (15,368) were uniformed.

Between FY1989 and FY1999, the acquisition workforce decreased nearly 50% to a low of 124,000 employees. This decline is attributable in large part to a series of congressionally mandated reductions between FY1996 and FY1999. These cuts reflected Congress's then-view that the acquisition workforce size was not properly aligned with the acquisition budget and the size of the uniformed force. A number of analysts believe that these cuts led to shortages in the number of properly trained, sufficiently talented, and experienced personnel, which in turn has had a negative effect on acquisitions.

In an effort to rebuild the workforce, between FY2008 and the first quarter of FY2016, the acquisition workforce grew by 24% (30,434 employees). According to DOD, the Department accomplished its strategic objective to rebuild the workforce. Officials stated that certification and education levels have improved significantly: currently, over 96% of the workforce meet position certification requirements and 83% have a bachelor's degree or higher. In addition, DOD officials stated that they have positioned the workforce for long-term success by strengthening early and mid-career workforce cohorts.

The increase in the size of the workforce has not kept pace with increased acquisition spending. According to DOD, from 2001 to 2015, the acquisition workforce increased by some 21%. Over the same period, contract obligations (adjusted for inflation) increased approximately 43%. While this increase in spending does not necessarily argue for increasing the size of the workforce, according to DOD officials, the increased spending has also corresponded to an increase in the workload and complexity of contracting. Four congressional efforts to improve the acquisition workforce are:

- the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (P.L. 101-510),

- hiring and pay flexibilities enshrined in numerous sections of law,

- the Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund (P.L. 110-181), and

- strategic planning for the acquisition workforce (P.L. 111-84).

These four efforts seek to enhance the training, recruitment, and retention of acquisition personnel by, respectively, establishing (1) professional development requirements, (2) monetary incentives and accelerated hiring, (3) dedicated funding for workforce improvement efforts, and (4) formal strategies to shape and improve the acquisition workforce.

Introduction

This report provides background on the Department of Defense (DOD) acquisition workforce. Specifically, the report addresses the following questions:

- 1. What is the acquisition workforce?

- 2. What is the current size of the acquisition workforce?

- 3. How has Congress sought to improve the acquisition workforce in the past?

- 4. What are some potential questions for Congress to explore in the area of acquisition workforce management to improve acquisitions?

Background

Congress and the executive branch have long been frustrated with perceived waste, mismanagement, and fraud in defense acquisitions and have spent significant resources attempting to reform and improve the process. These frustrations have led to numerous efforts to improve defense acquisitions. Despite these efforts, cost overruns, schedule delays, and performance shortfalls in acquisition programs persist.1 A number of analysts have argued that the successive waves of acquisition reform have generally yielded limited results, due in large part to poor management by the acquisition workforce.2

In recent years, a renewed consensus seems to have emerged around the importance of improving the acquisition workforce as a critical part of any comprehensive acquisition reform effort. A 2014 compilation of expert views on acquisition reform published by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations) identified four themes, two of which deal exclusively with the acquisition workforce:

While the experts who participated in this project offered a variety of views, a few common themes emerged ... the Subcommittee notes the following

1. Nearly half of the experts feel that cultural change is required while over two-thirds believe improving incentives for the acquisition workforce is necessary for reform.

2. Two-thirds of the contributors feel that training and recruiting of the acquisition workforce must be improved.

3. Nearly half believe that DOD needs to attain realistic requirements at the start of a major acquisition program that includes budget-informed decisions.

4. More than half of the submissions noted the need for strong accountability and leadership throughout the life-cycle of a weapon system.... 3

Recent legislation has also emphasized the importance of a robust and effective acquisition workforce. The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2016 included more than 10 provisions specifically geared to the acquisition workforce.4 Given the current focus on acquisition reform and the role of the workforce in the success of the acquisition system, it is useful to explore exactly who is in (and who is not in) this workforce, and recent efforts by Congress to improve its performance.

How Is the Acquisition Workforce Defined?

Broadly speaking, the acquisition workforce are those uniformed and civilian government personnel, working across the Department of Defense and in more than a dozen functional communities (including technology, logistics, and contracting), who are responsible for identifying, developing, buying, and managing goods and services to support the military.5 Generally, the acquisition workforce consists of uniformed and civilian personnel who are either

- in positions designated as part of the acquisition workforce under the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (10 U.S.C. §1721);

- in positions designated as part of the acquisition workforce by the heads of the relevant military component, pursuant to DOD Instruction 5000.66; or

- temporary members of the acquisition workforce or personnel who contribute significantly to the process, as defined in the Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund (10 U.S.C. §1705).

The Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (10 U.S.C. §1721)

10 U.S.C. §1721 required the Secretary of Defense to promulgate regulations designating "those positions that are acquisition positions," and required that acquisition-related positions in the following fields be included in the definition of the acquisition workforce:

|

1. Program management 2. Systems planning, research, development, engineering, and testing 3. Procurement, including contracting 4. Industrial property management 5. Logistics 6. Quality control and assurance 7. Manufacturing and production |

8. Business, cost estimating, financial management, and auditing 9. Education, training, and career development 10. Construction 11. Joint development and production with other government agencies and foreign countries 12. Acquisition-related positions in management headquarters activities and support activities |

DOD Guidance on Acquisition Workforce (DOD Instruction 5000.66)

DOD instruction 5000.66, entitled Operation of the Defense Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics Workforce Education, Training, and Career Development Program, implements 10 USC §1721 and governs the establishment and management of the acquisition workforce.6 Pursuant to the law, the instruction directs the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (AT&L) to identify "appropriate career paths for civilian and military personnel in the AT&L workforce in terms of education, training, experience, and assignments necessary for career progression." It also requires the heads of DOD components (i.e., Component Acquisition Executives) to designate the positions that make up the acquisition workforce.7

Defense Acquisition University publishes the AT&L position category descriptions on their website.8 All acquisition workforce billets designated by Component Acquisition Executives must fall within one of these categories.9 Within each military service, the Director, Acquisition Career Management (DACM) is responsible for tracking the acquisition workforce personnel data. This data is consolidated in the central AT&L database DataMart.

Temporary Members of the Acquisition Workforce

The authorities in 10 U.S.C. §1705, the Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund (DAWDF), states that, only for the purposes of the section, the term acquisition workforce includes personnel who are not serving in a designated position, but

(A) contribute significantly to the acquisition process by virtue of their assigned duties; and

(B) are designated as temporary members of the acquisition workforce by the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, or by the senior acquisition executive of a military department, for the limited purpose of receiving training for the performance of acquisition-related functions and duties. (Italics added.)

While considered part of the workforce for the purposes of DAWDF, personnel falling into these two categories are not included in the total count of the acquisition workforce.10

Beyond the Acquisition Workforce

As 10 USC §1705 acknowledges, a number of activities critical to successful acquisitions—such as requirements development and budgeting—are performed by personnel who are not part of the formal acquisition workforce. As DOD Instruction 5000.02 states,

Stable capability requirements and funding are important to successful program execution. Those responsible for the three processes at the DoD level and within the DoD Components must work closely together to adapt to changing circumstances as needed, and to identify and resolve issues as early as possible.11

The text box below describes selected personnel who are not included in the official acquisition workforce, but perform important acquisition-related functions. In addition to these personnel, contractors, a number of whom support program offices and acquisition processes, are not considered part of the acquisition workforce.

|

The Acquisition Workforce vs. the Workforce Responsible for Successful Acquisitions A number of different disciplines are involved in defense acquisitions. Defense Acquisitions consists of more than just executing a contract or managing an acquisition program. It includes strategic planning, identifying a requirement, estimating costs, budgeting, program management, resource management, oversight, testing, payment, and contract closeout (as depicted below).

Personnel who are outside of the traditional "acquisition workforce" are responsible for critical elements of the defense acquisition process depicted above, including (but not limited to)

|

The recent report by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (discussed above) reinforces the importance of non-acquisition personnel who are critical to successful acquisitions. As mentioned above, the first two themes focus on the general culture and management of the acquisition workforce. The other two themes highlight specific perceived shortcomings of the acquisition system that are beyond the control of the acquisition workforce: the need to develop realistic and stable requirements, and the need for strong leadership and accountability throughout the life-cycle of a weapon system. To the extent some of the most widely recognized problems affecting the acquisition system are controlled by individuals who are outside of the acquisition workforce (such as requirements development, requirements stability, and budgeting), reform efforts focusing primarily on the acquisition workforce might have only limited effects. In considering approaches to acquisition reform, the acquisition workforce could be thought of more broadly, to encompass those personnel who exercise influence and play critical roles in the acquisition process.

What Is the Size and Composition of the Acquisition Workforce?

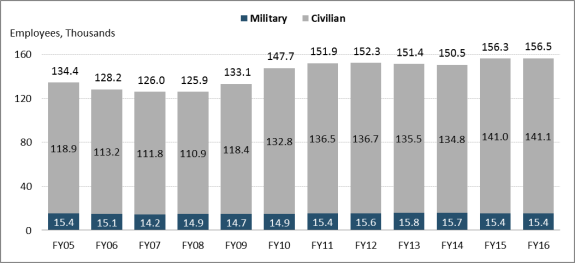

According to DOD, as of December 31, 2015, the defense acquisition workforce consisted of 156,457 personnel, of which approximately 90% (141,089) were civilian and 10% (15,368) were uniformed (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Defense Acquisition Workforce Size, FY2005 - FY2016 As of December 31, 2015 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Defense, "Defense Acquisition Workforce Key Information, As of FY16Q1," at http://www.hci.mil/data/2016Q1/Overall_Key_Information_FY16Q1.pdf. Notes: The data in the FY16 column are as of the end of the first quarter. The data in the other years are as of the end of that fiscal year. Data do not include personnel who are not included in the total count of the acquisition workforce, but perform acquisition-related activities, including contractors. Reliable data were not available prior to FY2005 due to varied methods for categorizing and counting the number of defense acquisition personnel. |

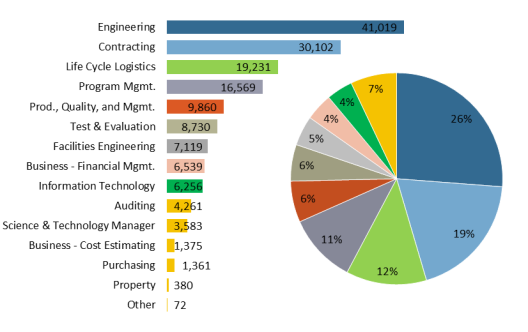

The acquisition workforce currently consists of 14 distinct career fields. As of December 31, 2015, almost half of the acquisition workforce (45%) fell into two career fields: engineering or contracting (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2. Acquisition Workforce by Career Field As of December 31, 2015 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Defense, "Defense Acquisition Workforce Key Information, As of FY16Q1," at http://www.hci.mil/data/2016Q1/Overall_Key_Information_FY16Q1.pdf. Notes: DOD listed career categories exceed the number of, and do not correspond precisely to, the categories set forth in 10 USC §1721. The category "other" consolidates the six smallest career categories, representing less than one tenth of 1 percent of the total workforce. |

Trends in Acquisition Workforce Size

Between FY1989 and FY1999, the acquisition workforce decreased nearly 50% to a low of 124,000 employees.16 The declines are attributable in large part to a series of congressionally mandated reductions between FY1996 and FY1999, which ranged in reductions from 15,000 to 25,000 employees each fiscal year.17 These cuts reflected Congress's then-view that the acquisition workforce size was not properly aligned with the acquisition budget and the size of the uniformed force.18

A number of DOD officials and researchers have asserted that the workforce downsizing in the 1990s led to shortages in the number of properly trained, sufficiently talented, and experienced personnel, which in turn has had a long-term negative effect on defense acquisitions.19 These concerns have persisted despite subsequent increases in the size of the workforce over time. For example, in 2014, DOD officials asserted that workforce size has not kept pace with the increasing amount and complexity of the acquisition workload.20

Between FY2008 and the first quarter of FY2016, the acquisition workforce grew by 24% (30,434 employees) (see Figure 1). These gains are partially attributable to an initiative launched by then Secretary of Defense Robert Gates in April 2009, which sought to significantly increase the size of the acquisition workforce by FY2015.21

According to DOD, the Department accomplished its strategic objective to rebuild the acquisition workforce (from 126,000 in 2011 to over 150,000) despite major barriers such as sequestration, furloughs, and hiring freezes. Officials also stated that DOD certification and education levels have improved significantly: currently, over 96 percent of the workforce meet position certification requirements and 83 percent of the workforce have a bachelor's degree or higher. In addition, DOD "has reshaped and positioned the workforce for future success by strengthening early and mid-career workforce year groups."22

Acquisition Workforce Size and Defense Contract Spending

According to DOD, from 2001 to 2015, the size of the acquisition workforce increased by approximately 21%. Over the same period, DOD contract obligations (adjusted for inflation) increased at approximately 43% (see Figure 3).

The definition of the acquisition workforce, and the methodology for counting the workforce, has evolved over the years. As such, historical data on the size of the acquisition workforce prior to FY2005 may contain inconsistent measures from year to year. For a discussion on the reliability of data drawn from the Federal Procurement Data System, see CRS Report R41820, Department of Defense Trends in Overseas Contract Obligations, by Moshe Schwartz and Wendy Ginsberg.

A closer look at these trends indicates that as spending increased (FY2001-FY2008), the acquisition workforce shrunk; as spending declined (FY2008-FY2015), the acquisition workforce grew. As the dollars spent on contracting increased (as have the complexity and workload of contracting), from a long-term workforce planning perspective, it could be preferable for the size of the workforce to expand along with—and not in negative correlation to—spending increases.

Congressional Efforts to Improve the Acquisition Workforce

Congress has pursued numerous efforts to improve the capability and performance of the acquisition workforce, including (but not limited to) the following:

- 1. the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (P.L. 101-510),

- 2. hiring and pay flexibilities (e.g., P.L. 110-417),

- 3. the Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund (P.L. 110-181), and

- 4. strategic planning for the acquisition workforce (P.L. 111-84).

These four tools aim to enhance the training, recruitment, and retention of acquisition personnel by, respectively, establishing (1) professional development requirements, (2) monetary incentives and accelerated hiring, (3) dedicated funding for workforce improvement efforts, and (4) formal strategies to shape and improve the acquisition workforce.

Defense Acquisition Workforce Investment Act (DAWIA)

DAWIA, enacted in 1990, was intended to address identified knowledge and skill deficiencies in the acquisition workforce.23 The act mandated the development of education, training, and qualification requirements for designated acquisition positions.24 For example, DAWIA directed the Secretary of Defense to develop formal career paths for acquisition positions that include education and training that facilitate progression along those paths.25 Part of the logic behind DAWIA was the recognition that it is not enough to have an appropriately sized acquisition workforce; the skills and abilities of the workforce are critical to acquisition success.

A key tool for implementing DAWIA is the Defense Acquisition University (DAU), which was established by DAWIA in 1990.26 DAU provides standardized training and coursework necessary to receive required certifications for positions in each acquisition career field.27 For example, a GS-11 Contract Administrator position at the Defense Contract Management Agency requires candidates to receive level II contracting certification from DAU within 24 months of entrance on duty.28 To be eligible for certification, the employee must successfully complete nine contract-related DAU courses, have two years of contract experience, and possess the listed education requirements.29 DAU certifications are only available to DOD employees in DAWIA-coded positions.

Hiring and Pay Flexibilities

Congress and the Office of Personnel Management have authorized hiring and pay flexibilities to enhance recruitment and retention of qualified personnel, including those in the acquisition workforce. Hiring flexibilities are intended to enhance employee recruitment by simplifying and accelerating the hiring process, often by waiving some or all competitive hiring requirements in Title 5 of the United States Code (such as veterans' preference). Pay flexibilities are intended to enhance employee retention by providing employees with higher or additional compensation that is not typically provided or available to all federal employees.30 Hiring and pay flexibilities can be government-wide or agency-specific. Some hiring and pay flexibilities have been authorized exclusively for the acquisition workforce.

Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund (DAWDF)

DAWDF, enacted in 2008, provides annual dedicated funding to education, training, recruitment, and retention initiatives for the acquisition workforce.31 For example, according to DOD, roughly 54% of FY2015 DAWDF obligations were used for recruitment (such as job fairs) and were used to hire 799 new acquisition personnel.32 Further, 39% of FY2015 DAWDF obligations financed training and development activities, such as adding or modernizing DAU courses.33

The law requires DOD to credit specified amounts to the fund each year, which can be reduced to a specified lower amount if determined as sufficient by the Secretary of Defense.34 For instance, DOD credited $560 million to the fund rather than the required $700 million in FY2015.35 The NDAA for FY2016 required DOD to credit $500,000 to the fund, which can be reduced to $400,000 if the Secretary of Defense determines that the lower amount is sufficient.36 The House version of the NDAA for FY2017, however, includes language that would allow the Secretary to credit $0 to the fund in FY2017.37 The accompanying report states that this provision "addresses an overfunding of the fund that has resulted from carryovers from prior years."38

Strategic Workforce Plan for the Acquisition Workforce

In section 1108 of the FY2010 NDAA (as amended),39 Congress required DOD to submit to Congress a biennial strategic workforce plan aimed at shaping and improving the civilian workforce, including a separate chapter discussing the acquisition workforce.40 By statute, this chapter is to address specifically shaping and improving the acquisition workforce (including military and civilian personnel).

DOD's Fiscal Years 2013-2018 Strategic Workforce Plan Report (submitted July 2012) incorporated acquisition workforce issues into the report. However, Appendix 1 of the report, reserved for a stand-alone discussion on the "Acquisition Functional Community," was blank, with the page reading "This report has not been submitted."41 The most recent strategic workforce plan posted on the Defense Acquisition University website is dated April 2010.42 Similarly, acquisition workforce strategic plans for the military services date to 2010 or earlier.43 According to DOD officials, the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for AT&L expects to release its updated FY2016-FY2021 Acquisition Workforce Strategic Plan before the end of fiscal year 2016.44

Potential Questions for Congress

Despite recent efforts, many observers believe that DOD still faces significant challenges in improving the performance of the workforce responsible for defense acquisitions. The extent to which DOD is successful in improving the workforce may depend, in part, on congressional action.45 Answering the following questions could help Congress determine what, if any, further actions it deems necessary to try to improve the performance of the workforce responsible for acquisitions.

Developing the Acquisition Workforce

Just as the total force of the Department of Defense consists of active and reserve military, civilian personnel, and contractor support, so too the acquisition workforce relies on active and reserve military, civilian, and contractor personnel to manage acquisitions.46 DOD Instruction 1100.22, Policy and Procedures for determining Workforce Mix, lays out the policies and procedures for determining the appropriate mix of military, civilian, and contractor personnel (including inherently governmental activities). Guidance generally requires the use of cost as a deciding factor in determining the workforce mix and mandates the default use of DOD civilian personnel, when consistent with statute and DOD regulations.

Developing an appropriate workforce mix can be difficult due to budgetary, statutory, and regulatory constraints. Potential oversight questions for Congress may include the following:

- 1. What is the appropriate size of the acquisition workforce?

- 2. Does the acquisition workforce have the right mix of military, civilian, and contractor personnel?

- 3. What is the proper role of contractors in supporting program management offices?

- 4. What is the proper role and use of hiring and pay flexibilities to recruit and retain qualified acquisition professionals? Are the flexibilities achieving the desired results?

- 5. In what ways is DAU fulfilling, or not fulfilling, the mission and functions that Congress established with its creation?

- 6. What, if any, gaps in DAU's ability to keep its staff and curriculum current with, and adaptive to, ever changing subject specialties could be remedied by amendments to the university's authorizing statute?

- 7. Are DAWIA certifications creating a well-qualified, appropriately balanced, and professional workforce?47

Beyond the "Acquisition" Workforce

A number of the activities critical to successful acquisitions—such as requirements development and budgeting—are beyond the authority or control of the acquisition workforce. Potential oversight questions for Congress may include the following:

- 1. To what extent should efforts to improve acquisitions focus on the training and development of non-acquisition personnel who play critical roles in the acquisition process?

- 2. To what extent are the incentives of the acquisition workforce and the broader workforce responsible for successful acquisitions sufficiently aligned?

- 3. To what extent are the acquisition-related duties of the non-acquisition workforce sufficiently prioritized as core responsibilities?

DOD's Strategic Human Capital Plan for the Acquisition Workforce

A 2015 GAO report on strategic planning for the acquisition workforce found that, in the absence of an updated workforce strategy, DOD may "not be positioned to meet future workforce needs."48 Potential oversight questions for Congress may include the following:

- 1. To what extent is DOD taking a strategic approach to developing and managing the acquisition workforce?

- 2. To what extent are the military departments taking a strategic approach to developing and managing the acquisition workforce?

- 3. For which acquisition career fields is DOD having the most difficulty in recruiting and/or retaining federal employees?

- 4. Are there any gaps in the appropriate skills, competencies, and experiences of senior acquisition professionals to direct, and exercise oversight of, the work of both defense acquisition personnel and contract acquisition workers, and what activities are underway within DOD to remedy any such deficiencies?

- 5. To what extent, if any, should the Under Secretary for AT&L have authority over the acquisition workforce?

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

This CRS Report was originally co-authored by former CRS Specialist in Defense Acquisition Moshe Schwartz.

Footnotes

| 1. |

For a more in-depth discussion on acquisition reform and the role of the acquisition workforce, see CRS Report R43566, Defense Acquisition Reform: Background, Analysis, and Issues for Congress, by Moshe Schwartz. |

| 2. |

As a Blue Ribbon Panel observed in 1970, Regardless of how effective the overall system of Department procurement regulations may be judged to be, the key determinants of the ultimate effectiveness and efficiency of the Defense Procurement process are the procurement personnel.... The importance of this truism has not been appropriately reflected in the recruitment, career development, training, and management of the procurement workforce. See Department of Defense, Report to the President and the Secretary of Defense on the Department of Defense by the Blue Ribbon Panel, July 1, 1970, p. 94. |

| 3. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Defense Acquisition Reform: Where Do We Go From Here?, A Compendium of Views by Leading Experts, prepared by Staff Report, 113th Cong., 2nd sess., October 2, 2014. |

| 4. |

P.L. 114-92. See sections 826, 827, 841-846, and 1111-1113. See also CRS Report R44096, Acquisition Reform in House- and Senate-Passed Versions of the FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 1735), by Moshe Schwartz for an analysis of the extent to which the two bills focused on workforce in their respective acquisition reform efforts. |

| 5. |

Susan M. Gates, Edward G. Keating, and Adria D. Jewell, et al., The Defense Acquisition Workforce, RAND, An Analysis of Personnel Trends Relevant to Policy, 1993-2006, Santa Monica, CA, 2008, p. 2. |

| 6. |

U.S. Department of Defense, Operation of the Defense Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics Workforce Education, Training, and Career Development Program, Instruction 5000.66, December 21, 2005. |

| 7. |

Ibid., Enclosure 2, E2.1.1.3., which states in full The CAEs shall designate the AT&L positions in their respective DOD Components according to references (a) [DOD Directive 5000.02] and (i) [chapter 87 of title 10, United States Code] and the uniform AT&L position category descriptions. AT&L positions shall be identified wherever they exist in the Department of Defense, disregarding the DOD Component or mission of an organization element. Wage Grade, Foreign National, and Executive Level positions shall not be designated as AT&L positions. |

| 8. |

Defense Acquisition University, "Acquisition, Technology, & Logistics Workforce Position Category Descriptions (PCDs) last updated April 7, 2015, at http://icatalog.dau.mil/pcds.asp. |

| 9. |

For a discussion on the specific categories, see infra, "What Is the Size and Composition of the Acquisition Workforce?" |

| 10. |

Email exchange with DAU officials, January 5, 2014. |

| 11. |

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (AT&L), Operation of the Defense Acquisition System, DOD Instruction 5000.02, January 7, 2015, p. 4. |

| 12. |

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System, CJCSI Instruction 3170.01I, January 23, 2015, pp. A-1, A-3; Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Manual for the Operation of the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System (JCIDS), February 12, 2015, including errata as of December 18, 2015, Enclosure C. |

| 13. |

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (AT&L), Operation of the Defense Acquisition System, DOD Instruction 5000.02, January 7, 2015, p. 5. |

| 14. |

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), Department of Defense Financial Management Policy and Procedures, DOD Instruction 7000.14-R, at http://comptroller.defense.gov/fmr.aspx. |

| 15. |

U.S. Department of the Army, "Army Budget," at http://www.asafm.army.mil/offices/office.aspx?officecode=1200. |

| 16. |

Government Accountability Office, Acquisition Workforce, Department of Defense's Plans to Address Workforce Size and Structure Challenges, GAO-02-630, April 2002, pp. 2-3, at http://www.gao.gov/assets/240/234364.pdf. |

| 17. |

P.L. 104-106, §906(d); P.L. 104-201, §902; P.L. 105-85, §912; P.L. 105-261, §931; CRS Report 98-938, Defense Acquisition Workforce: Issues for Congress, by Valerie Bailey Grasso; GAO, Defense Acquisition Organizations, Status of Workforce Reductions, NSIAD-98-161, June 28, 1998, pp. 1-2, at http://gao.gov/assets/230/225955.pdf. The listed author is formerly of the Congressional Research Service. Questions from congressional clients about the report can be directed to Kathryn Francis or Moshe Schwartz. |

| 18. |

See, for example, U.S. Congress, House Committee on National Security, Military Procurement Subcommittee, Department of Defense Acquisition Workforce, 105th Cong., 1st sess., April 8, 1997, pp. 403-405 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1997); U.S. Congress, House Committee on National Security, report to accompany H.R. 1530, 104th Cong., 1st sess., H.Rept. 104-131 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1995), p. 11. |

| 19. |

DOD, Office of the Inspector General, DOD Acquisition Workforce Reduction Trends and Impacts, D-2000-088, February 29, 2000, at http://www.dodig.mil/Audit/reports/fy00/00-088.pdf; Mark Nackman, "The Aftermath of the Decision to Reduce the Defense Acquisition Workforce: Impacts, Difficulties Ahead, and Fixes," Journal of Contract Management, Summer 2010, pp. 80-83. |

| 20. |

Testimony of former Acting DOD Assistant Secretary of Defense for Readiness and Force Management Stephanie Barna, in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Armed Services, Defense Reform: Empowering Success in Acquisition, hearings, 113th Cong., 2nd sess., July 10, 2014, H.A.S.C. No. 113-115 (Washington, DC: GPO, 2015); The Acquisition 2005 Task Force, Shaping The Civilian Workforce of the Future, October 2000, p. 3, at http://www.acq.osd.mil/dpap/Docs/report1000.pdf. |

| 21. |

In April 2009, the Secretary of Defense announced a goal to rebalance and rebuild the acquisition workforce. See DOD, "Defense Budget Recommendation Statement," press release, April 6, 2009, at http://archive.defense.gov/Speeches/Speech.aspx?SpeechID=1341. In April 2010, DOD released a strategic plan that included a goal to insource 10,000 contractors and hire an additional 10,000 individuals. See DOD, Strategic Human Capital Plan Update, The Defense Acquisition Workforce, April 2010, PDF p. 8, at https://dap.dau.mil/policy/Documents/Policy/DAW%20Report%20To%20Congress%202010.pdf. |

| 22. |

Based on email exchange with DOD officials, June 28, 2016. |

| 23. |

A 1986 report by the Blue Ribbon Panel identified education and training deficiencies in the defense acquisition workforce. See President's Blue Ribbon Commission on Defense Management, A Quest for Excellence: Final Report to the President, June 1986, pp. 39-71, at http://www.ndia.org/Advocacy/AcquisitionReformInitiative/Documents/Packard-Commission-Report.pdf. |

| 24. |

P.L. 101-510, Title XII, codified in 10 U.S.C. Chapter 87. |

| 25. |

P.L. 101-510, §1722. Codified at 10 U.S.C. §1722. |

| 26. |

10 U.S.C. §1746; DOD Directive Number 5000.57, "Defense Acquisition University," December 18, 2013, at http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/500057p.pdf. |

| 27. |

For more information on DAU, see Defense Acquisition University, http://icatalog.dau.mil/onlinecatalog/faq_catalog.asp. |

| 28. |

The job announcement was located at https://www.usajobs.gov/GetJob/ViewDetails/439264600/. |

| 29. |

Defense Acquisition University, "Certification Standards & Core Plus Development Guide, Contracting Level II," at http://icatalog.dau.mil/onlinecatalog/CareerLvl.aspx?lvl=2&cfld=3. |

| 30. |

For a list of selected hiring and pay flexibilities available to federal agencies, see U.S. Office of Personnel Management, Human Resources Flexibilities and Authorities in the Federal Government, August 2013, at https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/reference-materials/handbooks/humanresourcesflexibilitiesauthorities.pdf. |

| 31. |

10 U.S.C. §1705. |

| 32. |

DOD, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (AT&L), Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund (DAWDF) FY 2015 Report to Congress, April 2016, p. 8, at http://www.hci.mil/policy/FY15_DAWDF_Annual_Report_to_Congress.pdf. |

| 33. |

Ibid., p. 16. |

| 34. |

10 U.S.C. §1705(d)(2). |

| 35. |

DOD, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (AT&L), Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund (DAWDF) FY 2015 Report to Congress, April 2016, p. 2. |

| 36. |

P.L. 114-92, §841(a)(1)(A). Prior to FY2016, the law required DOD to credit amounts equal to specified percentages of total expenditures on contract services each fiscal year. |

| 37. |

H.R. 4909, sec. 839 (114th Congress). |

| 38. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Armed Services, report to accompany H.R. 4909 114th Cong., 2nd sess., H.Rept. 114-537 (Washington, DC: GPO, 2016), p. 198. |

| 39. |

P.L. 111-84, §1108. Codified at 10 U.S.C. §115b. |

| 40. |

The original statutory requirement for DOD to submit a report annually was amended by P.L. 112-81 §935(a)(1)(A) to require a biennial submission. |

| 41. |

See U.S. Department of Defense, Strategic Workforce Plan, Fiscal Years 2013-2018, Appendix 1, at http://dcips.dtic.mil/documents/SWPWholeReportCDv2.pdf. |

| 42. |

U.S. Department of Defense, Strategic Human Capital Plan Update, The Defense Acquisition Workforce, April 2010. |

| 43. |

Based on briefings from the military services, as of May 2014. Recent searches of DOD websites by CRS did not reveal updated workforce plans. |

| 44. |

Based on CRS conversation with senior DOD officials, June 8, 2016. |

| 45. |

As GAO stated as far back as 1992, "ultimately, change will occur only through the collective action of acquisition participants, particularly within the Department of Defense and the Congress, for it is their actions that dictate the incentives that drive the process." See U.S. General Accounting Office, Weapons Acquisition: A Rare Opportunity for Lasting Change, NSIAD 93-15, December 1992, p. 3. See also CRS Report R43566, Defense Acquisition Reform: Background, Analysis, and Issues for Congress, by Moshe Schwartz. |

| 46. |

U.S. Department of Defense, Quadrennial Defense Review, 2014, p. 47, at http://archive.defense.gov/pubs/2014_Quadrennial_Defense_Review.pdf. |

| 47. |

According to 2010 RAND reports on the acquisition workforce, the extent to which DAU certification standards and associated training align with actual acquisition workforce skill requirements. See RAND, Shining A Spotlight on the Defense Acquisition Workforce—Again, 2009, p. 26, at http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/occasional_papers/2010/RAND_OP266.pdf; RAND, The Acquisition Cost-Estimating Workforce, 2009, pp. 23-27, at http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2009/RAND_TR708.pdf. |

| 48. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Defense Acquisition Workforce, Actions Needed to Guide Planning Efforts and Improve Workforce Capability, GAO-16-80, December 2015, p. 27, at http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/674152.pdf. |