War Legacy Issues in Southeast Asia: Unexploded Ordnance (UXO)

More than 40 years after the end of the Vietnam War, unexploded ordnance (UXO) from numerous conflicts, but primarily dropped by U.S. forces over Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam during the Vietnam War, continues to cause casualties in those countries. Over the past 25 years, the United States has provided a total of over $400 million in assistance for UXO clearance and related activities in those three countries through the Department of Defense (DOD), Department of State (DOS), and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), as well as funding for treatment of victims through USAID and the Leahy War Victims fund. Although casualty numbers have dropped in recent years, no systematic assessment of affected areas has been done, and many observers believe it may still take decades to clear the affected areas.

War legacy issues such as UXO clearance and victim assistance may raise important considerations for Congress as it addresses the impact of U.S. participation in conflicts around the world and how the United States should deal with the aftermath of such conflicts. The continued presence of UXO in Southeast Asia raises numerous issues, including appropriate levels of U.S. assistance for clearance activities and victim relief; coordination in efforts among DOD, DOS, and USAID; the implications of U.S. action on relations with affected countries; whether U.S. assistance in Southeast Asia carries lessons for similar activity in other parts of the world, including Iraq and Afghanistan; and, more generally, efforts to lessen the prevalence of UXO in future conflicts.

Many observers argue that U.S. efforts to address UXO issues in the region, along with joint efforts regarding other war legacy issues such as POW/MIA identification and Agent Orange/dioxin remediation, have been important steps in building relations with the affected countries in the post-war period. These efforts that have proceeded furthest in Vietnam, where the bilateral relationship has expanded across a wide range of economic and security initiatives. In Cambodia and Laos, where bilateral relations are less developed, UXO clearance is one of the few issues on which working-level officials from the United States and the affected countries have cooperated for years. Although some Cambodians and Laotians view U.S. demining assistance as a moral obligation and the U.S. government has viewed its support for UXO clearance as an important, positive aspect of its ties with the two countries, the issue of UXO has not been a major factor driving the relationships.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6) provides $196.5 million for “conventional weapons destruction” around the world, including $159.0 million for “humanitarian demining,” with $3.85 million appropriated for Cambodia, $30.0 million for Laos, and $15.0 million for Vietnam.

The Legacies of War Recognition and Unexploded Ordnance Removal Act (H.R. 2097) would authorize $50 million per year for fiscal years 2020 to 2024 for humanitarian assistance in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam to develop national UXO surveys, conduct UXO clearance, and finance capacity building, risk education, and support for UXO victims.

War Legacy Issues in Southeast Asia: Unexploded Ordnance (UXO)

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview

- Background on Unexploded Ordnance

- What Is Unexploded Ordnance (UXO)?

- Military Use

- Mines and Cluster Munitions

- U.S. Policy on Cluster Munitions

- UXO in Southeast Asia

- Overview

- The Situation in Cambodia

- Contamination and Casualties

- Cleanup Efforts

- The Situation in Laos

- Contamination and Casualties

- Cleanup Efforts

- The Situation in Vietnam

- Contamination and Casualties

- Cleanup Efforts

- U.S. UXO Assistance in Southeast Asia

- U.S. Department of State and USAID Activities

- U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) and UXO Remediation Activities

- U.S. Indo Pacific Command and UXO Remediation in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos

- Implications for Congress

Figures

Summary

More than 40 years after the end of the Vietnam War, unexploded ordnance (UXO) from numerous conflicts, but primarily dropped by U.S. forces over Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam during the Vietnam War, continues to cause casualties in those countries. Over the past 25 years, the United States has provided a total of over $400 million in assistance for UXO clearance and related activities in those three countries through the Department of Defense (DOD), Department of State (DOS), and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), as well as funding for treatment of victims through USAID and the Leahy War Victims fund. Although casualty numbers have dropped in recent years, no systematic assessment of affected areas has been done, and many observers believe it may still take decades to clear the affected areas.

War legacy issues such as UXO clearance and victim assistance may raise important considerations for Congress as it addresses the impact of U.S. participation in conflicts around the world and how the United States should deal with the aftermath of such conflicts. The continued presence of UXO in Southeast Asia raises numerous issues, including appropriate levels of U.S. assistance for clearance activities and victim relief; coordination in efforts among DOD, DOS, and USAID; the implications of U.S. action on relations with affected countries; whether U.S. assistance in Southeast Asia carries lessons for similar activity in other parts of the world, including Iraq and Afghanistan; and, more generally, efforts to lessen the prevalence of UXO in future conflicts.

Many observers argue that U.S. efforts to address UXO issues in the region, along with joint efforts regarding other war legacy issues such as POW/MIA identification and Agent Orange/dioxin remediation, have been important steps in building relations with the affected countries in the post-war period. These efforts that have proceeded furthest in Vietnam, where the bilateral relationship has expanded across a wide range of economic and security initiatives. In Cambodia and Laos, where bilateral relations are less developed, UXO clearance is one of the few issues on which working-level officials from the United States and the affected countries have cooperated for years. Although some Cambodians and Laotians view U.S. demining assistance as a moral obligation and the U.S. government has viewed its support for UXO clearance as an important, positive aspect of its ties with the two countries, the issue of UXO has not been a major factor driving the relationships.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6) provides $196.5 million for "conventional weapons destruction" around the world, including $159.0 million for "humanitarian demining," with $3.85 million appropriated for Cambodia, $30.0 million for Laos, and $15.0 million for Vietnam.

The Legacies of War Recognition and Unexploded Ordnance Removal Act (H.R. 2097) would authorize $50 million per year for fiscal years 2020 to 2024 for humanitarian assistance in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam to develop national UXO surveys, conduct UXO clearance, and finance capacity building, risk education, and support for UXO victims.

Overview

The remnants of the Vietnam War (1963-1975) and other regional conflicts have left mainland Southeast Asia as a region heavily contaminated with unexploded ordnance, or UXO.1 More than 45 years after the United States ceased its extensive bombing of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, hundreds of civilians are still injured or killed each year by UXO from those bombing missions or by landmines laid in conflicts between Cambodia and Vietnam (1975-1978), China and Vietnam (1979-1990) and during the Cambodian civil war (1978-1991). While comprehensive surveys are incomplete, it is estimated that more than 20% of the land in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam are contaminated by UXO.

Over more than 25 years, Congress has appropriated more than $400 million to assist Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam in clearing their land of UXO. More than 77% of the assistance has been provided via programs funded by the Department of State. In addition, the United States has provided treatment to those individuals maimed by UXO through U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) programs and the Leahy War Victims Fund.

Despite ongoing efforts by the three countries, the United States, and other international donors, it reportedly could take 100 years or more, at the current pace, to clear Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam of UXO.2 During that time period, more people will likely be killed or injured by UXO. In addition, extensive areas of the three nations will continue to be unavailable for agriculture, industry, or habitation, hindering the economic development of those three nations.

In 2016, President Obama pledged $90 million over a three-year period for UXO decontamination programs in Laos—an amount nearly equal to the total of U.S. UXO assistance to that nation over the previous 20 years.3 The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6) provides $196.5 million globally for "conventional weapons destruction," including $159.0 million for "humanitarian demining," under the Department of State's International Security Assistance programs.4 Of the humanitarian demining funds, $3.85 million is appropriated for Cambodia, $30.0 million for Laos,5 and $15.0 million for Vietnam. The act also provides $13.5 million for global health and rehabilitation programs under the Leahy War Victims Fund.

Moving forward, the 116th Congress will have an opportunity to consider what additional efforts, if any, the U.S. government should undertake to address the war legacy issue of UXO in mainland Southeast Asia in terms of the decontamination of the region and the provision of medical support or assistance to UXO victims. Beyond the immediate assistance such UXO-related programs would provide to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, U.S. aid on this war legacy issue may also foster better bilateral ties to those nations. For example, some observers view U.S. assistance to Vietnam for the war legacy issue of Agent Orange/dioxin contamination as playing an important role in improving bilateral relations.6

Background on Unexploded Ordnance

What Is Unexploded Ordnance (UXO)?

Unexploded ordnance (UXO) is defined as military ammunition or explosive ordnance which has failed to function as intended. UXO is also sometimes referred to as Explosive Remnants of War (ERW) or "duds" because of their failure to explode or function properly. UXO includes mines, artillery shells, mortar rounds, hand or rocket-propelled grenades, and rocket or missile warheads employed by ground forces (see Figure 1). Aerial delivered bombs, rockets, missiles, and scatterable mines that fail to function as intended are also classified as UXO. While many of these weapons employ unitary warheads, some weapons—primarily certain artillery shells, rocket and missile warheads and aerial bombs—employ cluster munitions, which disperse a number of smaller munitions as part of their explosive effect. Often times, these submunitions fail to function as intended. In addition, abandoned or lost munitions that have not detonated are also classified as UXO.

The probability of UXO detonating is highly unpredictable; it depends on whether or not the munition has been fired, the level of corrosion or degradation, and the specific arming and fusing mechanisms of the device. "Similar items may respond very differently to the same action—one may be moved without effect, while another may detonate. Some items may be moved repeatedly before detonating and others may not detonate at all." In all cases, UXO poses a danger to both combatants and unaware and unprotected civilians.7

Military Use

Military munitions are used in a variety of ways. Some are used in direct force-on-force combat against troops, combat vehicles, and structures. Others, such as emplaced anti-personnel and anti-vehicle mines or scatterable mines, can be used to attack targets, deny enemy use of key terrain, or establish barriers to impede or influence enemy movement. Cluster munitions can either explode on contact once dispensed or can remain dormant on the ground until triggered by human or vehicular contact. The military utility of cluster weapons is that they can create large areas of destruction, meaning fewer weapons systems and munitions are needed to attack targets.

|

|

Source: George Black, "The Vietnam War Is Still Killing People," The New Yorker, May 20, 2016. |

Mines and Cluster Munitions

Two particular classes of ordnance—mines and cluster munitions—have received a great deal of attention. Emplaced mines by their very nature pose a particular threat because they are often either buried or hidden and, unless their locations are recorded or some type of warning signs are posted, they can become easily forgotten or abandoned as the battlefield shifts over time. Cluster munitions are dispersed over an area and are generally smaller than unitary warheads, which can make them difficult to readily identify (see Figure 2). Since the conclusion of the Vietnam War, many of the newer mines and cluster munitions have a self-destruct or disarming capability. However, as long as their explosive charge remains viable, they pose a hazard to people.8

Both mines and cluster munitions have been subject to international protocols to limit or ban their development, transfer, and use. The 1999 Ottawa Convention "prohibits the use, stockpiling, production, and transfer of anti-personnel landmines (APLs). It requires states to destroy their stockpiled APLs within four years and eliminate all APL holdings, including mines currently planted in the soil, within 10 years."9 The 2010 Convention on Cluster Munitions prohibits all use, stockpiling, production and transfer of cluster munitions. The United States has refused to sign either convention, citing the military necessity of these munitions.10 The United States has, however, been a States Party to the Convention on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) since 1995, which "aims to protect military troops from inhumane injuries and prevent noncombatants from accidentally being wounded or killed by certain types of arms."11 In 2009, the United States ratified Protocol V of the CCW, Explosive Remnants of War.12 Protocol V "covers munitions, such as artillery shells, grenades, and gravity bombs, that fail to explode as intended, and any unused explosives left behind and uncontrolled by armed forces."13 Under Protocol V "the government controlling an area with explosive remnants of war is responsible for clearing such munitions. However, that government may ask for technical or financial assistance from others, including any party responsible for putting the munitions in place originally, to complete the task. No state-party is obligated to render assistance."14

The United States has undertaken a variety of initiatives—including mandating changes to munitions design and adopting federal safeguards and policy regulating their usage—to help limit the potential hazards posed to noncombatants by these UXO.15

|

|

Source: Tom Fawthrop, "The Curse of Cluster Bombs," Institute for Policy Studies, September 30, 2011. |

U.S. Policy on Cluster Munitions

On June 19, 2008, then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates issued a new policy on the use of cluster munitions.16 The policy stated that "[c]luster munitions are legitimate weapons with clear military utility," but it also recognized "the need to minimize the unintended harm to civilians and civilian infrastructure associated with unexploded ordnance from cluster munitions." To that end, the policy mandated that after 2018, "the Military Departments and Combatant Commands will only employ cluster munitions containing submunitions that, after arming, do not result in more than 1% unexploded ordnance (UXO) across the range of intended operational environments."

On November 30, 2017, then-Deputy Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan issued a revised policy on cluster munitions.17 The revised policy reverses the 2008 policy that established an unwaiverable requirement that cluster munitions used after 2018 must leave less than 1% of unexploded submunitions on the battlefield. Under the new policy, combatant commanders can use cluster munitions that do not meet the 1% or less unexploded submunitions standard in extreme situations to meet immediate warfighting demands. Furthermore, the new policy does not establish a deadline to replace cluster munitions exceeding the 1% rate, and these munitions are to be removed only after new munitions that meet the 1% or less unexploded submunitions standard are fielded in sufficient quantities to meet combatant commander requirements. However, the new DOD policy stipulates that the Department "will only procure cluster munitions containing submunitions or submunition warheads" meeting the 2008 UXO requirement or possessing "advanced features to minimize the risks posed by unexploded submunitions."

UXO in Southeast Asia

Overview

Although UXO in Southeast Asia can date back to World War II, the majority of the hazard is attributed to the Vietnam War. While an undetermined amount of UXO associated with the Vietnam War was from ground combat and emplaced mines, an appreciable portion of UXO is attributed to the air war waged by the United States from 1962 to 1973, considered by some to be one of the most intense in the history of warfare.18 One study notes the United States

dropped a million tons of bombs on North Vietnam. Three million more tons fell on Laos and Cambodia—supposedly "neutral" countries in the conflict. Four million tons fell on South Vietnam—America's ally in the war against communist aggression. When the last raid by B-52s over Cambodia on August 15, 1973, culminated American bombing in Southeast Asia, the United States had dropped more than 8 million tons of bombs in 9 years. Less than 2 years later, Cambodia, Laos, and South Vietnam were communist countries.19

The U.S. State Department in 2014 characterized the problem by country.20

- Cambodia: Nearly three decades of armed conflict left Cambodia severely contaminated with landmines and unexploded ordnance (UXO). The Khmer Rouge, the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF), the Vietnamese military, and, to a lesser extent, the Thai army, laid extensive minefields during the Indochina wars. These minefields are concentrated in western Cambodia, especially in the dense "K-5 mine belt" along the border with Thailand, laid by Vietnamese forces during the 1980s. UXO—mostly from U.S. air and artillery strikes during the Vietnam War and land battles fought along the border with Vietnam—contaminates areas in eastern and northeastern Cambodia. While the full extent of contamination is unknown, the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor reports that a baseline survey completed in 2012 of Cambodia's 124 mine-affected districts found a total of 1,915 square kilometers (739 square miles) of contaminated land.

- Laos: Laos is the most heavily bombed country per capita in the world as a result of the Indochina wars of the 1960s and 1970s. While landmines were laid in Laos during this period, UXO, including cluster munitions remnants (called "bombies" in Laos), represents a far greater threat to the population and account for the bulk of contamination. UXO, mostly of U.S. origin, remains in the majority of the country's 18 provinces.

- Vietnam: UXO contaminates virtually all of Vietnam as a result of 30 years of conflict extending from World War II through the Vietnam War. The most heavily contaminated provinces are in the central region and along the former demilitarized zone (DMZ) that divided North Vietnam and South Vietnam. Parts of southern Vietnam and areas around the border with China also remain contaminated with UXO.

The Situation in Cambodia

The Kingdom of Cambodia is among the world's most UXO-afflicted countries, contaminated with cluster munitions, landmines, and other undetonated weapons. U.S. bombing of northeastern Cambodia during the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese invasion in 1979, and civil wars during 1970s and 1980s all contributed to the problem of unexploded ordnance. In 1969, the United States launched a four-year carpet-bombing campaign on Cambodia, dropping 2.7 million tons of ordnance, including 80,000 cluster bombs containing 26 million submunitions or bomblets.21 Up to one-quarter of the cluster bomblets failed to explode, according to some estimates.22 In addition, the Vietnamese army mined the Cambodia-Thai border as it invaded the country and took control from the Khmer Rouge in 1979. The Vietnamese military, Vietnam-backed Cambodian forces, the Khmer Rouge, and Royalist forces reportedly all deployed landmines during the 1979-1989 civil war period.23 Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen occasionally has referred to the U.S. bombing of Cambodia, which occurred between 1969 and 1973, when criticizing the United States;24 however, the historical event has not been a major issue in recent U.S.-Cambodian relations.

Contamination and Casualties

There have been over 64,700 UXO casualties in Cambodia since 1979, including over 19,700 deaths.25 The Cambodia Mine/ERW Victim Information System (CMVIS) has recorded an overall trend of significant decreases in the number of annual casualties: 58 in 2017 compared to 111 in 2015, 186 in 2012 and 286 in 2010.26 Despite progress, the migration of poor Cambodians to the northwestern provinces bordering Thailand, one of the most heavily mined areas in the world, has contributed to continued casualties.27 Cambodia, with 25,000 UXO-related amputees, has the highest number of amputees per capita in the world.28 The economic costs of UXO include obstacles to infrastructure development, land unsuitable for agricultural purposes, and disruptions to irrigation and drinking water supplies.

Open Development Cambodia, a website devoted to development-related data, reports that since the early 1990s, about 580 square miles (1,500 square kilometers) of land has been cleared of UXO.29 Estimates of the amount of land still containing UXO vary. According to some reports, about 50% of contaminated land has been cleared, and an estimated 630 square miles (1,640 square kilometers) of land still contain UXO.30 Many of the remaining areas are the most densely contaminated, including 21 northwestern districts along the border with Thailand that contain anti-personnel mines laid by the Vietnamese military and that account for the majority of mine casualties.31

Cleanup Efforts

Between 1993 and 2017, the U.S. government contributed over $133.6 million for UXO removal and disposal, related educational efforts, and survivor assistance programs in Cambodia. These activities are carried out largely by U.S. and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), in collaboration with the Cambodian Mine Action Center, a Cambodian NGO, and the Cambodian government. USAID's Leahy War Victims Fund has supported programs to help provide medical and rehabilitation services and prosthetics to Cambodian victims of UXO.32 Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining and Related Programs (NADR) funding for demining activities was $5.5 million in both 2015 and 2016, $4.2 in 2017, and $2.9 million in 2018.33 Global donors contributed over $132 million between 2013 and 2017, mostly for clearance efforts. In 2017, the largest contributors of demining and related assistance were the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, and Germany, providing approximately $10.6 million in total.34

In 2018, the Cambodian government and Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA), a government agency, launched the National Mine Action Strategy (NMAS) for 2018-2025. The goal of removing UXO from all contaminated areas by 2025 would require the clearance of 110 square kilometers per year at a cost of about $400 million.35 The NMAS estimated that at the current rate of progress, however, Cambodia would need a little over 10 years to complete clearance of all known mined areas. Some experts are concerned that declining international assistance could jeopardize clearance goals.36 In 2017, total international demining support to Cambodia decreased by 61%, largely due to lower contributions from Australia and Japan.37

The Situation in Laos

From 1964 through 1973, the United States military reportedly flew 580,000 bombing runs and dropped over 2 million tons of cluster munitions, including over 270 million cluster bombs, on the small land-locked country.38 The total was more than the amount dropped on Germany and Japan combined in World War II. An estimated one-third of these munitions failed to explode.39 The Lao government claims that up to 75-80 million submunitions or bomblets released from the cluster bombs remain in over one-third of the country's area.40 Military conflicts during the French colonial period and the Laotian Civil War during the 1960s and 1970s have also contributed to the problem of UXO/ERW.

The U.S. bombing campaign in Laos was designed to interdict North Vietnamese supply lines that ran through Laos. The bombing campaign also supported Lao government forces fighting against communist rebels (Pathet Lao) and their North Vietnamese allies. Cluster munitions were considered the "weapon of choice" in Laos because they could penetrate the jungle canopy, cover large areas, and successfully attack convoys and troop concentrations hidden by the trees. The most heavily bombed areas in Laos were the northeastern and southern provinces, although UXO can be found in 14 of the country's 17 provinces. The bombings in the northeast were intended to deny territory, particularly the Plain of Jars, to Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese forces and, in the south, to sever the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which crossed the border into eastern Laos. The northeastern part of Laos was also used as a "free drop zone" where planes that had taken off from bases in Thailand and had been unable to deliver their bombs, could dispose of them before returning to Thailand.

Contamination and Casualties

According to the Geneva-based Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, since 1964, there have been over 50,000 mine and ERW casualties in Laos, including over 29,000 people killed.41 An estimated 40% of victims are children.42 In 2012, the Lao government's Safe Path Forward Strategic Plan II set a target to reduce UXO-related casualties to 75 per year by 2020, from levels between 100-200 victims annually during the 2000s. The country has already met these goals: in 2017, the number of reported casualties was 41, including four killed.

Cluster munitions have hampered economic development in the agricultural country. UXO contamination affects one-quarter of all Lao villages, and 22% of detonations occur through farming activities.43 Unexploded ordnance adversely affects not only agricultural production, but also mining, forestry, the development of hydropower projects, and the building of roads, schools, and clinics. Expenditures on demining efforts and medical treatment divert investment and resources from other areas and uses. Many injured UXO survivors lose the ability to be fully productive. According to the Lao government, there appears to be a significant correlation between the presence of UXO and the prevalence of poverty.44

Cleanup Efforts

Lao PDR officials state that the country needs $50 million annually for ongoing UXO/ERW clearance, assistance to victims, and education, of which the Lao government contributes $15 million.45 International assistance comes from numerous sources, including Japan, the United States, and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). The United States has contributed a total of $169 million for UXO clearance and related activities since 1995, with funding directed to international NGOs and contractors.46 That makes Laos the third largest recipient of conventional weapons destruction funding over that period, after Afghanistan and Iraq.47 In 2016, the United States announced a three-year, $90 million increase in assistance covering FY2016-FY2018. Half the amount, or $45 million, is aimed at conducting the first nationwide cluster munitions remnant survey, while the other half is aimed at clearance activities.

Since the early 1990s, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) has been involved in training Lao personnel in demining techniques. U.S. UXO clearance and related humanitarian aid efforts, administered by the State Department (DOS), began in 1996. U.S. support also helped to establish the Lao National Demining Office, the UXO Lao National Training Center, and the Lao National Regulatory Authority.

The United States finances the bulk of its mine clearance operations through the NADR foreign aid account. NADR demining programs constitute the largest U.S. assistance activity in Laos, which receives little U.S. development aid compared to other countries in the region. It has been channeled primarily to international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), the UNDP's trust fund for UXO clearance, and the Lao National Unexploded Ordnance Program (UXO Lao). Laos also has received humanitarian assistance through the USAID Leahy War Victims Fund for prosthetics, orthotics, and rehabilitation ($1.4 million in 2011-2013).

For many years in the 1990s and 2000s, UXO-related clearance programs were one of the primary areas of substantive cooperation between the United States and Laos. Some argue that such activity has helped foster bilateral ties with a country whose authoritarian government is deeply inward looking. When President Obama became the first U.S. President to visit Laos in 2016, announcing the $90 million UXO aid package, he said: "Given our history here, I believe that the United States has a moral obligation to help Laos heal. And even as we continue to deal with the past, our new partnership is focused on the future."48

The Situation in Vietnam

War Legacy issues—Agent Orange/dioxin contamination, MIAs, and UXO—played an important role in the reestablishment of diplomatic relations between the United States and Vietnam, and it led to the development of a comprehensive partnership between the two nations. Vietnam's voluntary effort to locate and return the remains of U.S. MIAs was a significant factor in the restoration of diplomatic relations.49 U.S. assistance to decontaminate Da Nang airport of Agent Orange/dioxin likely contributed to the two nations' move to a comprehensive partnership.50 While not as prominent, U.S. UXO assistance to Vietnam most likely has been a factor in establishing trust between the two governments.

The UXO in Vietnam are remnants from conflicts spanning more than a century, potentially as far back as the Sino-French War (or Tonkin War) of 1884-1885 and as recent as the Cambodian-Vietnamese War (1975-1978) and the border conflicts between China and Vietnam from 1979 to 1991.51 According to one account, during Vietnam's conflicts with France and the United States (1945-1975), more than 15 million tons of explosives were deployed—four times the amount used in World War II.52 It is generally presumed, however, that the majority of the UXO in Vietnam are from the Vietnam War, also known in Vietnam as "the Resistance War Against America" (1955-1975).

Contamination and Casualties

Estimates of the amount of UXO in Vietnam vary. According to one source, "at least 350,000 tons of live bombs and mines remain in Vietnam."53 Another source claims "around 800,000 tons of unexploded ordnance remains scattered across the country."54

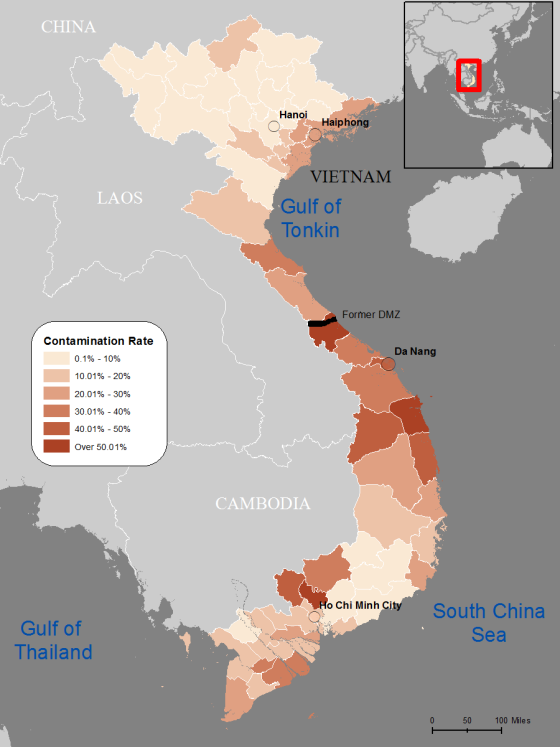

Viewed in terms of land area, the Vietnamese government estimates that between 6.1 and 6.6 million hectares (23,500-25,500 square miles) of land in Vietnam—or 19% to 21% of the nation—is contaminated by UXO.55 An official Vietnamese survey started in 2004 and completed in 2014 estimated that 61,308 square kilometers (23,671 square miles) was contaminated with UXO.56 According to the survey, UXO is scattered across virtually all of the nation, but the province of Quang Tri, along the previous "demilitarized zone" (DMZ) between North and South Vietnam, is the most heavily contaminated (see Figure 3).

Figures on the number of UXO casualties in Vietnam also vary. One source says, "No one really knows how many people have been injured or killed by UXO since the war ended, but the best estimates are at least 105,000, including 40,000 deaths."57 In its report on UXO casualties in Vietnam, however, the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor listed the casualty figures for 1975-2017 as 38,978 killed and 66,093 injured.58 For 2017 only, the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor reported eight deaths and six injured.

A survey of UXO casualties determined that the three main circumstances under which people were killed or injured by UXO were (in order): scrap metal collection (31.2%); playing/tampering (27.6%); and cultivating or herding (20.3%). In some of Vietnam's poorer provinces, people proactively seek out and collect UXO in order to obtain scrap metal to sell to augment their income, despite the inherent danger.59

Cleanup Efforts

On March 8, 2018, Vietnam's Ministry of National Defence (MND) established the Office of the Standing Agency of the National Steering Committee of the Settlement of Post-war Unexploded Ordnance and Toxic Chemical Consequences, or Office 701, to address the nation's UXO issue.60 Office 701 is responsible for working with individuals and organizations to decontaminate Vietnam of UXO to ensure public safety, clean the environment, and promote socio-economic development. Under a 2013 directive by the Prime Minister, the Vietnam National Mine Action Center (VNMAC) was established within the MND with responsibility for proposing policy, developing plans, and coordinating international cooperation for UXO clearance.61 The MND's Center for Bomb and Mine Disposal Technology (BOMICEN) is the central coordinating body for Vietnam's UXO clearance operations. In addition, Vietnam created a Mine Action Partnership Group (MAPG) to improve coordination of domestic and international UXO clearance operations.

BOMICEN typically sets up project management teams (PMTs) that work with provincial or local officials to identify, survey, and decontaminate UXO.62 The PMTs usually interview local informants about possible UXO sites and then conduct field evaluations to determine if UXO is present and suitable for removal by Vietnam's Army Engineering Corps. The PMTs also collect information about the decontamination site and report back to BOMICON about the location and type of UXO removed.

Besides the clearance operations directly conducted by Vietnam, several nations and international organizations conduct UXO removal projects in Vietnam, including the Danish Demining Group (DDG), the Mines Advisory Group (MAG), Norwegian People's Aid (NPA), and PeaceTrees Vietnam. In 2016, the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), in cooperation with VNMAC and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), initiated a $32 million, multi-year UXO project in the provinces of Binh Dinh and Quang Binh.63 The joint project began operations in March 2018 and is scheduled to end in December 2020.64

NGOs working in Vietnam report some issues in their collaboration with the MND, which has declared portions of contaminated provinces off limits for UXO surveying and decontamination. Many of these areas contain villages and towns inhabited by civilians. In addition, the MND has not been providing information about any UXO clearance efforts being conducted in these areas. The lack of information sharing has hindered efforts to establish a nationwide UXO database that is being used to refine UXO location and clearance techniques.65

U.S. UXO Assistance in Southeast Asia

Since 1993, the United States has provided UXO and related assistance to Southeast Asia via several different channels, including the Center for Disease Control (CDC), the Department of Defense (DOD), the Department of State (DOS), and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)(see Table 1). For all three countries covered by this report, most of the assistance has been provided by DOS through its Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining and Related Programs/Conventional Weapons Destruction (NADR-CWD) account. USAID assistance to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam has consisted primarily of Leahy War Victims Fund programs for prostheses, physical rehabilitation, training, and employment. Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam have been the largest recipients of U.S. conventional weapons destruction (CWD) funding in East Asia.

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

FY1993-FY2017a |

2018 |

2019 est. |

2020 req. |

|

|

Cambodia |

|||||||

|

* CDC |

0 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

— |

— |

— |

|

* DOD |

2,379 |

1,717 |

1,969 |

24,063 |

— |

— |

— |

|

* DOS |

8,307 |

8,522 |

4,300 |

94,388 |

2,000 |

3,850 |

7,000 |

|

* USAID |

500 |

303 |

0 |

15,084 |

— |

||

|

Subtotal |

133,635 |

||||||

|

Laos |

|||||||

|

* CDC |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

— |

— |

— |

|

* DOD |

111 |

10 |

7,021 |

— |

|||

|

* DOS |

26,880 |

20500 |

30000 |

145,114 |

30,000 |

30,000 |

10,000 |

|

* USAID |

2,000 |

2,166 |

3,005 |

16,971 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Subtotal |

169,106 |

||||||

|

Vietnam |

|||||||

|

* CDC |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1,848 |

— |

— |

— |

|

* DOD |

340 |

722 |

1,168 |

4,295 |

— |

— |

— |

|

* DOS |

12,548 |

10,709 |

12,500 |

86,359 |

12,500 |

15,000 |

8,000 |

|

* USAID |

0 |

0 |

0 |

26,799 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Subtotal |

119,301 |

||||||

|

Total |

422,042 |

Source: FY2015-FY2017 numbers and FY1993-FY2017 totals: U.S. Department of State, To Walk the Earth in Safety, 17th Edition, December 18, 2018. FY2018 and FY2020 (requested) numbers: Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations, FY2020. FY2019 numbers (estimated): S.Rept. 115-282 to accompany S. 3108, the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Act, FY2020 and Joint Explanatory Statement to accompany P.L. 116-6, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019.

Notes:

In December 2013, the United States and Vietnam signed a Memorandum of Understanding on cooperation to overcome the effects of "wartime bomb, mine, and unexploded ordnance" in Vietnam.66 In their November 2017 joint statement, President Trump and President Tran Dai Quang "committed to cooperation in the removal of remnants of explosives from the war."67

U.S. Department of State and USAID Activities

Department of State and USAID demining and related assistance support the work of international NGOs in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. International NGOs work primarily with local NGOs in Cambodia and, to a greater extent, collaborate with government entities in Laos and Vietnam. The main areas of assistance are clearance, surveys, and medical assistance. In Cambodia, the Department of State and USAID support programs that collaborate with and train Cambodian organizations in clearance activities, conduct geographical surveys, help process explosive material retrieved from ERW, and provide mine risk education. In Laos, U.S. assistance includes clearance and survey efforts, medical and rehabilitation services, education and training assistance to victims and families, and mine risk education. In Vietnam, the United States provides mine clearance and survey support, capacity building programs, and medical assistance and vocational training for victims.68

U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) and UXO Remediation Activities

DOD's role in remediating UXO in Southeast Asia falls under the category of "Support to Humanitarian Mine Action (HMA)." Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) Instruction "Department of Defense Support to Humanitarian Mine Action, CJCSI 3207.0IC" dated September 28, 2018, covers DOD's responsibilities in this regard. DOD's stated policy is

to relieve human suffering and the adverse effects of land mines and other explosive remnants of war (ERW)69 on noncombatants while advancing the Combatant Commanders' (CCDRs') theater campaign plan and U.S. national security objectives. The DOD HMA program assists nations plagued by land mines and ERW by executing "train-the-trainer" programs of instruction designed to develop indigenous capabilities for a wide range of HMA activities.70

It is important to note that U.S. Code restricts the extent to which U.S. military personnel and DOD civilian employees can actively participate in UXO activities as described in the following section:

Exposure of USG Personnel to Explosive Hazards.

By law, DOD personnel are restricted in the extent to which they may actively participate in ERW clearance and physical security and stockpile management (PSSM) operations during humanitarian and civic assistance. Under 10 U.S.C. 401(a)(1), Military Departments may carry out certain "humanitarian and civic assistance activities" in conjunction with authorized military operations of the armed forces in a foreign nation. 10 U.S.C. 407(e)(1) defines the term "humanitarian demining assistance" (as part of humanitarian and civic assistance activities) as "detection and clearance of land mines and other ERW, and includes the activities related to the furnishing of education, training, and technical assistance with respect to explosive safety, the detection and clearance of land mines and other ERW, and the disposal, demilitarization, physical security, and stockpile management of potentially dangerous stockpiles of explosive ordnance." However, under 10 U.S.C. 407(a)(3), members of the U.S. Armed Forces while providing humanitarian demining assistance shall not "engage in the physical detection, lifting, or destroying of land mines or other explosive remnants of war, or stockpiled conventional munitions (unless the member does so for the concurrent purpose of supporting a United States military operation)." Additionally, members of the U.S. Armed Forces shall not provide such humanitarian demining and civic assistance "as part of a military operation that does not involve the armed forces." Under DOD policy, the restrictions in 10 U.S.C. 407 also apply to DOD civilian personnel.71

In general terms, U.S. law restricts DOD to "train-the-trainer" type UXO remediation activities unless it is required as part of a U.S. military operation involving U.S. armed forces.

U.S. Indo Pacific Command and UXO Remediation in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos72

U.S. Indo Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM)73 is responsible for U.S. military activities in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. As part of USINDOPACOM's Theater Campaign Plan,74 selected UXO remediation activities for Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos are briefly described in the following sections:

Vietnam: USINDOPACOM has tasked U.S. Army Pacific (USARPAC) as the primary component responsible for land-based UXO operations and the Pacific Fleet (PACFLT) as the primary component responsible for underwater UXO operations in Vietnam. FY2018 accomplishments and FY2019 and FY2020 plans are said to include:

FY2018:

Trained individuals on International Mine Action Standards (IMAS)75 Level I and II;

Trained individuals on Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) instructor development;

Familiarized individuals on EOD equipment;

Conducted medical first responder training;

Trained individuals on medical instructor development;

Trained individuals on underwater remote vehicle operations; and

Trained individuals on ordnance identification.

FY2019:

Continue training on International Mine Action Standards Level I;

Train individuals on how to develop training lanes for demining;

Exercise IMAS Level I concepts;

Increase Vietnamese medical first responder force structure; and

Continue EOD instructor development.

FY2020:

Plan to train on IMAS Level II with qualified IMAS Level I students;

Plan to enhance advanced medical-related technique training;

Plan to train in demolition procedures;

Plan to train in maritime UXO techniques;

Plan to conduct mission planning and to conduct a full training exercise; and

Plan to conduct instructor development.

Cambodia: USINDOPACOM has tasked Marine Forces Pacific (MARFORPAC) to be responsible for land-based UXO operations in Cambodia. Plans for FY2019 through FY2021 include:

FY2019:

Train in IMAS EOD Level I;

Train on EOD instructor development;

Familiarize students on EOD Level I equipment;

Review medical first responder training;

Train on medical instructor development;

Train in ordnance identification; and

Train in IMAS Demining Non-Technical Survey/Technical Survey (NTS/TS) techniques.

FY2020:

Plan to continue to develop capacity with IMAS EOD Level I and II training;

Plan to continue to build capacity with IMAS Demining Non-Technical Survey/Technical Survey techniques;

If EOD Level I and II training successful, plan to initiate EOD Level III training in late FY2020;

Plan to increase student knowledge of lane training development;

Plan to exercise IMAS Level II concepts;

Plan to increase Cambodian medical first responder force structure; and

Plan to continue EOD instructor development.

FY2021:

Plan to train on IMAS EOD Level II and EOD Level III with the qualified Level I and Level II students to increase their numbers;

Plan to train on IMAS Demining NTS/TS with the qualified students to increase their numbers;

Plan to enhance advanced medical-related techniques;

Plan to train in demolition procedures;

Plan to conduct mission planning and a full training exercise; and

Plan to conduct instructor development events.

Laos: USINDOPACOM has tasked Marine Forces Pacific (MARFORPAC) to be responsible for land-based UXO operations in Laos. Plans for FY2019 through FY2021 include:

FY2019:

Conduct training on IMAS EOD Level I;

Conduct training on EOD instructor development;

Conduct familiarization on EOD Level I equipment;

Conduct a review of medical first responder training;

Conduct medical instructor development training; and

Conduct training on ordnance identification.

FY2020:

Plan to continue to build capacity with training in IMAS EOD Level I and II;

Plan to increase knowledge on lane training development;

Plan to exercise IMAS Level II concepts;

Plan to increase medical first responder force structure and knowledge; and

Plan to continue EOD instructor development.

FY2021:

Plan to train on IMAS EOD Level II with the qualified Level I and Level II students to increase their numbers;

Plan to enhance advance medical-related techniques;

Plan to train in demolition procedures;

Plan to conduct mission planning and conduct a full training exercise; and

Continue to conduct instructor development.

Implications for Congress

The U.S. government has been providing UXO-related assistance to Southeast Asia for over 25 years, with contributions amounting to over $400 million. Despite this sustained level of support, as well as the efforts of the governments of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, it may take decades to clear these three nations of the known UXO contamination. These estimates, however, are based on incomplete information, as systematic nationwide UXO surveys have not been completed in either Cambodia or Laos.

The Legacies of War Recognition and Unexploded Ordnance Removal Act (H.R. 2097) would authorize $50 million each year for fiscal years 2020 to 2024 for address the UXO issue in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. The legislation also would authorize the President to provide humanitarian assistance for developing national UXO surveys, UXO clearance, and support for capacity building, risk education and UXO victims assistance in each nation. It would require the President to provide an annual briefing on related activities to the House Committee on Appropriations, the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, the Senate Committee on Appropriations, and the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

Southeast Asia's ongoing UXO challenge may present a number of issues for Congress to consider and evaluate. Among those issues are

- Funding levels—It is uncertain how much money it would take to decontaminate all three nations or provide adequate assistance to their UXO victims. Given this uncertainty, is the level of U.S. assistance being provided to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam to conduct humanitarian demining projects adequate to significantly reduce the UXO casualty risk in a reasonable time period? In addition, is the recent distribution of funding across the three nations equitable given their relative degrees of UXO contamination and their internal ability to finance demining projects?

- Coordination across agencies—Is there appropriate coordination across the U.S. agencies—the Department of Defense, the Department of State, and USAID—in providing demining assistance in Southeast Asia? Are these agencies utilizing the appropriated funds efficiently and effectively?

- Focus on clearance—Most of the appropriated funds have been for humanitarian demining projects and technical support, with less funding for assistance to UXO victims. The focus on clearance, rather than assistance on UXO victims, may in part be due to a concern about possible post-conflict liability issues. In light of past practices, should the U.S. government increase its support for UXO victims in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam beyond those being currently provided via the Leahy War Victims Fund?

- Implications for bilateral relations—Has the amount and types of U.S. UXO assistance to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam been a significant factor in bilateral relations with each of those nations? In Vietnam, work on war legacy issues formed an early part of building normalized relations in the post-War period—ties that have broadened into closer strategic and economic linkages. In Cambodia and Laos, UXO-related assistance has been one of the broadest areas for substantive cooperation between the United States and two countries with which the United States has had relatively cool relations. Would a change in the amount or type of assistance provided be beneficial to U.S. relations with Cambodia, Laos, or Vietnam? Should the U.S. government use UXO assistance to pressure other entities, such as Vietnam's MND, to be more cooperative in the UXO decontamination effort?

- UXO prevention—The Department of Defense has implemented a policy that is to eventually replace all cluster munitions with ones whose failure rate is below 1%. Should the U.S. government undertake additional efforts to reduce the amount of post-conflict UXO from U.S. munitions, including prohibiting the use of U.S. funding for certain types of submunitions that may leave UXO? Given DOD's current views and policies on cluster munitions and landmines, does this preclude the United States from joining the 2010 Convention on Cluster Munitions or 1999 Ottawa Convention on Landmines?

- Precedents and lessons for other parts of the world—Are there lessons that can be drawn from U.S. assistance for UXO clearance and victim relief in Southeast Asia that may be applicable to programs elsewhere in the world, including Afghanistan and Iraq? Have the levels of assistance the United States has offered in Southeast Asia signaled a precedent for other parts of the world?

During the 115th Congress, legislation was introduced that would have addressed some of these general issues associated with UXO, though none directly addressed the current situation in Southeast Asia. The Unexploded Ordnance Removal Act (H.R. 5883) would have required the Secretary of Defense, in concurrence with the Secretary of State, to develop and implement a strategy for removing UXO from Iraq and Syria. The Cluster Munitions Civilian Protection Act of 2017 (H.R. 1975 and S. 897) would have prohibited the obligation or expenditure of U.S. funds for cluster munitions if, after arming, the unexploded ordnance rate for the submunitions was more than 1%.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

The Department of Defense (DOD) defines UXO as "Explosive ordnance that has been primed, fuzed, armed, or otherwise prepared for action, and which has been fired, dropped, launched, projected, or placed in such a manner as to constitute a hazard to operations, installations, personnel, or material and remains unexploded either by malfunction or design or for any other cause." See Joint Publication (JP) 3-15, "Barriers, Obstacles, and Mine Warfare for Joint Operations," March 5, 2018. |

| 2. |

See Padriac Convery, "200 Years to Go Before Laos Is Cleared of Unexploded US Bombs from Vietnam War Era," South China Monring Post, November 16, 2018; Vu Minh, "Decades After War, Vietnam Threatened by 800,000 Tons of Explosives," VN Express, April 2, 2018. |

| 3. |

Amy Sawitta Lefevre and Roberta Rampton, "U.S. Gives Laos Extra $90 Million to Help Clear Unexploded Ordnance," Reuters, September 6, 2016. |

| 4. |

The specific allocations are contained in H.Rept. 116-9, which accompanies the act. |

| 5. |

S.Rept. 115-282 to accompany S. 3108, the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Act, FY2020, and Joint Explanatory Statement to accompany P.L. 116-6, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019. |

| 6. |

For more about U.S. Agent Orange/dioxin assistance to Vietnam, see CRS Report R44268, U.S. Agent Orange/Dioxin Assistance to Vietnam, by Michael F. Martin. |

| 7. |

Landmine Action: The Campaign against Landmines, "Explosive Remnants of War: Unexploded Ordnance and Post-Conflict Communities," 2002, http://www.cpeo.org/pubs/UXOreport_3_26.pdf. |

| 8. |

For more about cluster munitions, see CRS Report RS22907, Cluster Munitions: Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert and Paul K. Kerr. |

| 9. |

The Arms Control Association, The Ottawa Convention Fact Sheet," https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/ottawasigs, updated January 2018. |

| 10. |

Cambodia is a signatory to, and Laos and Vietnam have signed but not ratified, the Ottawa Convention. Laos is a signatory to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, while Cambodia and Vietnam are not. |

| 11. |

Arms Control Association Fact Sheet, "Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) at a Glance," https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/CCW, updated September 2017. |

| 12. |

International Committee on the Red Cross, "Treaties, States Parties, and Commentaries," https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/applic/ihl/ihl.nsf/States.xsp?xp_viewStates=XPages_NORMStatesParties&xp_treatySelected=610, accessed May 17, 2019. |

| 13. |

Arms Control Association Fact Sheet, "Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) at a Glance," https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/CCW, updated September 2017. |

| 14. |

Ibid. |

| 15. |

For additional information on U.S. cluster munitions policy see CRS Report RS22907, Cluster Munitions: Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert and Paul K. Kerr. |

| 16. |

Department of Defense, DoD Policy on Cluster Munitions and Unintended Harm to Civilians, June 19, 2008. |

| 17. |

Deputy Secretary of Defense, "DoD Policy on Cluster Munitions," memorandum, November 30, 2017. |

| 18. |

Holy High, James R. Curran, and Gareth Robinson, "Electronic Records of the Air War over South East Asia: A Database Analysis," Journal of Vietnamese Studies, vol. 8, 2014, p. 89. |

| 19. |

Mark Clodfelter, "The Limits of Airpower or the Limits of Strategy: The Air Wars in Vietnam and Their Legacies," Joint Forces Quarterly, National Defense University, 3rd Quarter 2015, pp. 111-112. |

| 20. |

U.S. Department of State, To Walk the Earth Safely: East Asia and Pacific, 13th Edition, September 30, 2014. |

| 21. |

The amount of U.S. ordnance dropped on Cambodia was more than the amount that the Allies dropped on Germany and Japan combined during World War II. See Henry Grabar, "What the U.S. Bombing of Cambodia Tells Us About Obama's Drone Campaign," The Atlantic, February 14, 2013; and Christopher Shay, "Cluster Munitions in the Spotlight as Groups Seek Ban on Bombs," Phnom Penh Post, October 30, 2008. |

| 22. |

Christopher Shay, "Cluster Munitions in the Spotlight as Groups Seek Ban on Bombs," Phnom Penh Post, October 30, 2008; Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, Cambodia, Mine Action, http://www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2018/cambodia/mine-action.aspx. |

| 23. |

The Halo Trust, Cambodia, https://www.halotrust.org/where-we-work/south-asia/cambodia/. |

| 24. |

Kimkong Heng, "Is Cambodia's Foreign Policy Heading in the Right Direction?" The Diplomat, February 8, 2019. |

| 25. |

Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, Cambodia, Casualties, http://the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2018/cambodia/casualties.aspx. |

| 26. |

Ibid. |

| 27. |

Department of State, To Walk the Earth in Safety, 16th Edition, December 13, 2017; Peter Zsombor, "Cambodia Sees Its First Month Without Mine, UXO Victims," The Cambodia Daily, July 28, 2017. |

| 28. |

The Halo Trust, op. cit. |

| 29. |

Open Development Cambodia, Landmines and Unexploded Ordnance in Cambodia, https://opendevelopmentcambodia.net/topics/landmines-uxo-and-demining/#return-note-73803-21. |

| 30. |

Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, Cambodia, Mine Action, op. cit.; Michael Hart, "Can Cambodia Meet Its Target to Remove Landmines by 2025?" Asian Correspondent, December 4, 2017. |

| 31. |

Ibid. |

| 32. |

Department of State, To Walk the Earth in Safety, 17th Edition, December 18, 2018. |

| 33. |

Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs-Conventional Weapons Destruction (NADR-CWD). Data from Department of State. |

| 34. |

Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, Cambodia, Support for Mine Action, http://www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2018/cambodia/support-for-mine-action.aspx. |

| 35. |

Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, Cambodia, Support for Mine Action, ibid.; Pech Sotheary, "China Grants Millions for Mine Clearance," Khmer Times, May 28, 2018. |

| 36. |

Department of State, To Walk the Earth in Safety, 17th Edition, December 18, 2018. |

| 37. |

Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, Cambodia, Support for Mine Action, op. cit. |

| 38. |

National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action Sector for Lao PDR, Annual Report 2015, and Legacies of War, "Secret War in Laos," http://legaciesofwar.org/about-laos/secret-war-laos/. |

| 39. |

White House, "Remarks by President Obama to the People of Laos," September 6, 2016. |

| 40. |

Legacies of War, "Leftover Unexploded Ordnance (UXO)," http://legaciesofwar.org/about-laos/leftover-unexploded-ordnances-uxo/. |

| 41. |

Landmine and Cluster Munitions Monitor, "Lao PDR: Casualties and Victim Assistance," updated June 5, 2015. |

| 42. |

CNN, "'My Friends Were Afraid of Me': What 80 Million Unexploded US Bombs Did to Laos," September 6, 2016. |

| 43. |

Ibid. |

| 44. |

National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action Sector for Lao PDR, op. cit. |

| 45. |

Khonesavanh Latsaphao, "Laos Is Not Meeting UXO Clearance Targets," Vientiane Times, May 3, 2013. |

| 46. |

Department of State, "Special Report: U.S. Conventional Weapons Destruction in Laos," July 17, 2018. |

| 47. |

Department of State, To Walk the Earth in Safety, 17th Edition, December 18, 2018. |

| 48. |

White House, "Remarks by President Obama to the People of Laos," September 6, 2016. |

| 49. |

See CRS Report RL33316, U.S.-Vietnam Relations in 2008: Background and Issues for Congress, by Mark E. Manyin. |

| 50. |

For more about U.S. Agent Orange/dioxin assistance to Vietnam, see CRS Report R44268, U.S. Agent Orange/Dioxin Assistance to Vietnam, by Michael F. Martin. |

| 51. |

The Sino-French War occurred between August 1884 and April 1885 over control of what is now northern Vietnam, but known as Tonkin at the time. Although the combined Vietnamese and Chinese forces were ultimately victorious in the land conflict in Vietnam, France was able to secure control over Annam (central Vietnam) and Tonkin in the Treaty of Tientsin. In the Cambodian-Vietnamese war, although the Communist Party of Kampuchea (also known as the "Khmer Rouge") and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (i.e., North Vietnam) were allies during the Vietnam War, fighting broke out between the newly-formed Democratic Kampuchea and Vietnam in 1975, ending with Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia in December 1978. China and Vietnam engaged in a series of border conflicts between 1979 and 1991, largely over disputed territory. |

| 52. |

Vu Minh, "Decades After War, Vietnam Threatened by 800,000 Tons of Explosives," VN Express, April 2, 2018. |

| 53. |

Ariel Garfinkel, "The Vietnam War Is Over. The Bombs Remain," New York Times, March 20, 2018. |

| 54. |

Vu Minh, "Decades After War, Vietnam Threatened by 800,000 Tons of Explosives," VN Express, April 2, 2018. |

| 55. |

Le Ha, "Vietnam to Issue Unexploded Ordnance Map," VietNamNet, June 16, 2016; and Vu Minh, "Decades After War, Vietnam Threatened by 800,000 Tons of Explosives," VN Express, April 2, 2018. |

| 56. |

Vietnam National Mine Action Center, Report on Explosive Remnants of War Contamination in Vietnam, April 3, 2018. |

| 57. |

Vuong Duc Anh and Xavier Bourgois, "Vietnam's Never-Ending War: Into the Trenches with the Bomb Disposal Squad," VN Express, October 17, 2016. |

| 58. |

Landmine and Cluster Munitions Monitor, Vietnam: Casualties, October 10, 2018. |

| 59. |

Hoang Tao, "Scrap Collectors' Dance with Death in Central Vietnam's Former Battlefields," VN Express, December 11, 2018. |

| 60. |

"New Office on Post-War Bomb, Mine Recovery Set Up," VN Express, March 9, 2018. |

| 61. |

Mine Action, Vietnam, November 16, 2018. |

| 62. |

Vietnam National Mine Action Center, Report on Explosive Remnants of War Contamination in Vietnam, 2018. |

| 63. |

"Korea Offer $20 Mln to Help Vietnam Remove Unexploded Ordnance," VN Express, June 14, 2016. |

| 64. |

"Vietnam-S Korea Mine Cleanup Launched," Viet Nam News, March 10, 2018. |

| 65. |

Based on CRS research trip to Vietnam, April 12-23, 2019. |

| 66. |

"Vietnam, US Sign First MOU on Bomb, Mine Clearance," Vietnam News Brief Service, December 17, 2013. |

| 67. |

White House, "Joint Statement: Between the United States of America and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam," press release, November 13, 2017. |

| 68. |

Department of State, To Walk the Earth in Safety, 17th Edition, December 18, 2018; Department of State, Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations (multiple years); Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor; USAID, Foreign Aid Explorer. |

| 69. |

DOD defines Explosive Remnants of War (ERW) as land mines, unexploded ordnance (UXO) (mortar rounds, artillery shells, bomblets, rockets, submunitions, rocket motors and fuel, grenades, small-arms ammunition, etc.), and abandoned ammunition storage and cache sites. |

| 70. |

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction "Department of Defense Support to Humanitarian Mine Action, CJCSI 3207.0IC," dated September 28, 2018, p. 1. |

| 71. |

Ibid., p. 2. |

| 72. |

Information in this section was provided to CRS by USINDOPACOM on January 28, 2019. |

| 73. |

U.S. Pacific Command (USPASCOM) was renamed U.S. Indo Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM) in 2018 to reflect the growing role of India in U.S. national security. |

| 74. |

The Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) defines a theater campaign plan as: "Plans developed by geographic combatant commands that focus on the command's steady-state activities, which include operations, security cooperation, and other activities designed to achieve theater strategic end states." |

| 75. |

According to the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining, International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) provide guidance, establish principles and, in some cases, define international requirements and specifications. They are designed to improve safety, efficiency and quality in mine action, and to promote a common and consistent approach to the conduct of mine action operations. The IMAS are intended to be the main guide for the development of National Mine Action Standards (NMAS), Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), and training material in mine action. https://www.gichd.org/topics/standards/international-standards/#.XFBciVxKiUk, accessed January 29, 2019. |