The Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) Program

The Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program, administered by the Department of Transportation’s Build America Bureau, provides long-term, low-interest loans and other types of credit assistance for the construction of surface transportation projects (23 U.S.C. §601 et seq.). The TIFIA program was reauthorized from FY2016 through FY2020 in the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act (P.L. 114-94). Direct funding for the TIFIA program is authorized at $300 million for each of FY2019 and FY2020. Additionally, state departments of transportation can use other federal-aid highway grant money, both formula and discretionary, to subsidize much larger loans. To date, states have not had to use other grant funding to subsidize credit assistance because the TIFIA program has a relatively large unexpended funding balance.

The primary goal of the TIFIA program, historically, has been to enable the construction of large-scale surface transportation projects by providing financing to complement state, local, and private investment. The TIFIA program has been one of the main ways in which the federal government has encouraged the development of public-private partnerships (P3s) and private financing in surface transportation often backed by new, but sometimes uncertain, revenue sources such as highway tolls, other types of user charges, and incremental real estate taxes. To be eligible for TIFIA assistance, a project sponsor must be deemed creditworthy, that is, a good risk for repaying its debts, and must have a dedicated source of revenue for repayment. Project sponsors, therefore, are required to develop a funding mechanism, whether this is a new user fee or tax or the repurposing of existing fees and taxes. Changes to the TIFIA program have sought to make TIFIA assistance more accessible to less costly projects, but so far every TIFIA-supported project has cost $175 million or more.

Financing projects instead of relying on pay-as-you go funding from taxes and other existing revenues can mean such projects can be constructed years earlier. TIFIA, therefore, is a means to accelerate project delivery and the benefits that flow from new infrastructure. The TIFIA program is also a relatively low-cost way for the federal government to support surface transportation projects because it relies on loans, not grants, and the TIFIA assistance is typically one-third or less of project costs. Another advantage from the federal point of view is that a relatively small amount of budget authority can be leveraged into a large amount of loan capacity. Because the government expects its loans to be repaid, an appropriation need only cover administrative costs and the subsidy cost of credit assistance. Program funding of $300 million can support approximately $4 billion in TIFIA loans.

Since its enactment in 1998, the TIFIA program has provided assistance of $32 billion to 74 projects with a total cost of about $117 billion (in FY2018 inflation-adjusted dollars). All but one TIFIA credit agreement has been a loan; the exception is a loan guarantee. The average TIFIA-supported project cost is $1.5 billion, and the average TIFIA loan is $430 million (both in FY2018 dollars). About two-thirds of TIFIA loans have gone to highway and highway bridge projects, and another quarter to public transportation. TIFIA has supported at least one project in 21 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, but the top 10 states account for about 80% of the 74 projects supported.

The TIFIA program is likely to be considered in the 116th Congress during the reauthorization of the surface transportation programs. Program funding is one issue that may be discussed, because some stakeholders would like more budget authority despite a relatively large unexpended balance and the existing authority of states to use grant funding to pay the subsidy cost of credit assistance. Criticisms of the program and its implementation include the often slow decisionmaking process, the program’s increasing risk aversion, and the limitation of the federal share of project costs to 33%, despite a statutory limit of 49%. Because of the relatively large unexpended balance, Congress might considered broadening the use of TIFIA assistance to nonsurface transportation and nontransportation infrastructure. Another option might be to create a national infrastructure bank, a federal infrastructure financing entity largely independent of other executive branch agencies, to take the place of TIFIA and other federal infrastructure credit assistance programs.

The Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) Program

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Program Overview

- Credit Assistance Process

- Subsidy Cost

- Program Funding

- Projects Financed

- Issues for Congress

- Funding

- Calculation of Subsidy Cost

- Federal Share

- Federal Share for Major Public Transportation Capital Projects

- Speed of Administrative Decisionmaking

- Broadening Eligible Uses of TIFIA Loans

Summary

The Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program, administered by the Department of Transportation's Build America Bureau, provides long-term, low-interest loans and other types of credit assistance for the construction of surface transportation projects (23 U.S.C. §601 et seq.). The TIFIA program was reauthorized from FY2016 through FY2020 in the Fixing America's Surface Transportation (FAST) Act (P.L. 114-94). Direct funding for the TIFIA program is authorized at $300 million for each of FY2019 and FY2020. Additionally, state departments of transportation can use other federal-aid highway grant money, both formula and discretionary, to subsidize much larger loans. To date, states have not had to use other grant funding to subsidize credit assistance because the TIFIA program has a relatively large unexpended funding balance.

The primary goal of the TIFIA program, historically, has been to enable the construction of large-scale surface transportation projects by providing financing to complement state, local, and private investment. The TIFIA program has been one of the main ways in which the federal government has encouraged the development of public-private partnerships (P3s) and private financing in surface transportation often backed by new, but sometimes uncertain, revenue sources such as highway tolls, other types of user charges, and incremental real estate taxes. To be eligible for TIFIA assistance, a project sponsor must be deemed creditworthy, that is, a good risk for repaying its debts, and must have a dedicated source of revenue for repayment. Project sponsors, therefore, are required to develop a funding mechanism, whether this is a new user fee or tax or the repurposing of existing fees and taxes. Changes to the TIFIA program have sought to make TIFIA assistance more accessible to less costly projects, but so far every TIFIA-supported project has cost $175 million or more.

Financing projects instead of relying on pay-as-you go funding from taxes and other existing revenues can mean such projects can be constructed years earlier. TIFIA, therefore, is a means to accelerate project delivery and the benefits that flow from new infrastructure. The TIFIA program is also a relatively low-cost way for the federal government to support surface transportation projects because it relies on loans, not grants, and the TIFIA assistance is typically one-third or less of project costs. Another advantage from the federal point of view is that a relatively small amount of budget authority can be leveraged into a large amount of loan capacity. Because the government expects its loans to be repaid, an appropriation need only cover administrative costs and the subsidy cost of credit assistance. Program funding of $300 million can support approximately $4 billion in TIFIA loans.

Since its enactment in 1998, the TIFIA program has provided assistance of $32 billion to 74 projects with a total cost of about $117 billion (in FY2018 inflation-adjusted dollars). All but one TIFIA credit agreement has been a loan; the exception is a loan guarantee. The average TIFIA-supported project cost is $1.5 billion, and the average TIFIA loan is $430 million (both in FY2018 dollars). About two-thirds of TIFIA loans have gone to highway and highway bridge projects, and another quarter to public transportation. TIFIA has supported at least one project in 21 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, but the top 10 states account for about 80% of the 74 projects supported.

The TIFIA program is likely to be considered in the 116th Congress during the reauthorization of the surface transportation programs. Program funding is one issue that may be discussed, because some stakeholders would like more budget authority despite a relatively large unexpended balance and the existing authority of states to use grant funding to pay the subsidy cost of credit assistance. Criticisms of the program and its implementation include the often slow decisionmaking process, the program's increasing risk aversion, and the limitation of the federal share of project costs to 33%, despite a statutory limit of 49%. Because of the relatively large unexpended balance, Congress might considered broadening the use of TIFIA assistance to nonsurface transportation and nontransportation infrastructure. Another option might be to create a national infrastructure bank, a federal infrastructure financing entity largely independent of other executive branch agencies, to take the place of TIFIA and other federal infrastructure credit assistance programs.

Introduction

The Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program provides long-term, low-interest loans and other types of credit assistance for the construction of surface transportation projects.1 The TIFIA program, administered by the Build America Bureau of the Department of Transportation (DOT), was reauthorized most recently in the Fixing America's Surface Transportation (FAST) Act (P.L. 114-94) from FY2016 through FY2020. Direct funding for the TIFIA program to make loans is authorized at $300 million for each of FY2019 and FY2020, but state departments of transportation can also use federal-aid highway grant money, both formula and discretionary, to subsidize much larger loans.

The primary goal of the TIFIA program, historically, has been to enable the construction of large-scale surface transportation projects by providing low-interest, long-term financing to complement state, local, and private investment. The TIFIA program has been one of the main ways in which the federal government has encouraged the development of public-private partnerships (P3s) and private financing in surface transportation often backed by new, but sometimes uncertain, revenue sources such as highway tolls, other types of user charges, and incremental real estate taxes.2 Since its enactment in 1998 as part of the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21; P.L. 105-178) through FY2018, the TIFIA program has provided assistance of $32 billion to 74 projects with a total cost of about $117 billion (in FY2018 inflation-adjusted dollars).3

Congress has used the TIFIA program as a model for other initiatives, notably the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) program, administered by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers.4 Several recent proposals would expand TIFIA assistance. For example, the Trump Administration's $200 billion infrastructure plan, based on leveraging state, local, and private resources, proposed adding several billion dollars of budget authority for TIFIA and expanding eligibility to ports and airports.5 The experience of TIFIA over the past decade shows, however, that there are limits to financing projects in this way. These limits include the number of projects that can take advantage of credit assistance, the difficulties of developing revenue mechanisms to service loans, the typical need for grant funding to make up a portion of the capital, and the difficulties of attracting private investment to risky projects, particularly those for which demand is uncertain or hard to predict.

Program Overview

Credit assistance provided by the TIFIA program can be in the form of loans, loan guarantees, and lines of credit. To date, all TIFIA assistance except one loan guarantee has been in the form of loans. Loans and loan guarantees can be provided up to a maximum of 49% of project costs; lines of credit can be for an amount up to a maximum of 33% of project costs. Despite the higher limit established in law, DOT has generally limited loans and loan guarantees to no more than 33% of project costs, so as "to ensure that the DOT shares the credit risk with other participants."6

Projects eligible for TIFIA assistance include highways and bridges, public transportation, transit-oriented development, intercity passenger bus and rail, intermodal connectors, intermodal freight facilities, and the capitalization of a rural projects fund.7 Eligible applicants for TIFIA assistance include state and local governments, railroad companies (including Amtrak), transit agencies, and private entities.

Surface transportation projects are not evaluated for TIFIA assistance based on their projected benefits and costs. Instead, projects are assessed on creditworthiness, the ability of borrowers to repay their loans, and a number of other eligibility criteria. To be judged creditworthy, a project's senior debt obligations and the borrower's ability to repay the federal credit instrument must receive investment-grade ratings from at least one, but typically two, nationally recognized credit rating agencies. Generally, a project must cost $50 million or more to be eligible for assistance, but the threshold is $15 million for intelligent transportation system projects and $10 million for transit-oriented development projects, rural projects, and local projects.8 Another requirement is that loans must be repaid with a dedicated revenue stream, typically a project-related user fee, such as a toll, but sometimes dedicated tax revenue.9

The attractiveness of TIFIA financing is its low cost, its flexibility, and its long duration, features that are hard to match in the private capital market. Federal credit assistance provides funds at a low fixed rate, the Treasury rate for a similar maturity; for rural infrastructure projects, federal assistance is provided at half the Treasury rate. Loans are available for up to 35 years from the date of substantial completion of a project. Repayments can be deferred for up to five years after substantial completion, and amortization can be flexible. In some circumstances, TIFIA can reduce the transaction costs of borrowing, which for tax-exempt bonds typically include underwriter fees, bond counsel expenses, and the cost of borrowing funds before they are needed (known as "negative carry").10 The Riverside County Transportation Commission in California is using TIFIA financing to build the I-15 Tolled Express Lanes Project, and has estimated that using traditional bond financing in lieu of a $150 million TIFIA loan would have cost an additional $25 million for the $471 million project.11

The characteristics of TIFIA financing can make it easier for project sponsors to attract the less patient and less flexible capital that is typically offered in the private market. This is especially important for projects like new toll roads, for which usage and revenue may take several years to grow to cover debt repayment. TIFIA financing is available with a senior or subordinate lien, but is typically used as subordinate debt, meaning it is in line to be repaid after the project's operational expenses and senior debt obligations. However, the TIFIA statute includes a provision which requires that in the event of a project bankruptcy, the federal government will be made equal with senior debt holders. This is referred to as the "springing lien," and has led some to ask whether TIFIA financing is truly subordinate. The springing lien issue notwithstanding, TIFIA financing is generally thought to reduce project risk, thereby helping to secure private financing at rates lower than would otherwise be available.

Financing projects instead of relying on pay-as-you go funding can mean such projects can be constructed years earlier than otherwise. TIFIA, therefore, is a means to accelerate project delivery and the benefits that flow from new infrastructure. Because of its advantages in terms of cost and flexibility, TIFIA may increase the number of projects that can be financed and thus provided on an accelerated schedule. In its 2016 report to Congress, DOT cited the example of managed lanes on U.S. 36 connecting Boulder and Denver, CO, a project it says was delivered 20 years earlier than anticipated because of TIFIA assistance.12

Credit Assistance Process

Applications for credit assistance to DOT are accepted at any time. Formal acceptance into the program for evaluation follows a letter of interest from the project sponsor in a format prescribed by DOT.13 However, DOT recommends that project sponsors contact DOT much earlier for technical assistance to discuss and develop an application. This can involve an emerging project agreement between DOT and the project sponsor.

Acceptance into the TIFIA program requires a fee of $250,000 that is used to cover the costs of DOT's outside financial and legal advice. Additional amounts may be necessary if DOT's costs exceed $250,000. DOT notes that fees for a single project are typically between $400,000 and $700,000.14 For projects with estimated costs of less than $75 million, DOT is permitted to draw on federal funds to cover its costs, up to a total of $2 million annually, rather than charging fees to prospective borrowers.15

Prior to submitting a formal application for credit assistance, DOT will review the letter of interest, the independent financial analysis, and any other supporting material. A key element of this review is an analysis of the creditworthiness of the project sponsor and the quality of the revenue pledged to repay the federal government. DOT also requires an oral presentation by the project sponsor. If these are satisfactory, DOT will invite the project sponsor to submit a formal application. The statute requires DOT to determine within 30 days whether the application is complete or whether additional material needs to be submitted.16 Within 60 days of that determination, DOT must inform the applicant whether the application has been approved or not. DOT staff make a recommendation to the DOT Council on Credit and Finance, with the Secretary of Transportation making the final decision.17

In addition to the regular credit assistance process, the FAST Act required DOT to create an expedited application process for low-risk projects. These are defined as projects requesting $100 million or less in credit assistance, with a dedicated revenue stream unrelated to project performance (e.g., a dedicated sales tax) and standard loan terms.

Like highway and public transportation projects that receive federal grants, projects financed under TIFIA are subject to laws and regulations concerning planning requirements; review and mitigation of environmental effects; the use of domestic iron, steel, and manufactured goods; and payment of prevailing wages.18 For example, projects must comply with the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) regarding the effects of the project on the human and natural environment. Typically, the NEPA analysis must be well advanced before a letter of interest is submitted. A TIFIA loan or other credit assistance will not be made until a final NEPA decision has been issued.

The process for securing assistance has been praised for being predictable, but it has also been criticized for being slow and bureaucratic. For example, an official of Transurban, an Australia-based operator of toll roads, told Congress that the company did not pursue a TIFIA loan for the I-395 high occupancy toll (HOT) lanes in Virginia, in part because of the slowness of the approval process.19 There has also been criticism that the TIFIA program office has become more risk-averse, favoring low-risk projects that might be able to obtain financing from conventional sources.20

Subsidy Cost

Credit programs like TIFIA are governed by the Federal Credit Reform Act (FCRA) of 1990.21 Under FCRA, the cost to the federal government of a credit program is the administrative cost plus the subsidy cost of the credit assistance. According to FCRA, the subsidy cost is "the estimated long-term cost to the government of a direct loan or a loan guarantee ... calculated on a net present value basis."22 The subsidy cost estimate takes into account potential losses to the government resulting from loan defaults. Budget authority is typically provided to cover subsidy and administrative costs of a credit program. Costs of the TIFIA program are met by funding from the Highway Trust Fund (HTF) authorized by the FAST Act.

When a loan is made, the subsidy cost amount is taken from the available budget authority and added to money borrowed from the Treasury to make the loan. When the principal and interest are repaid by the borrower, money is transferred back to the Treasury. Budgeting for credit programs is done for a cohort of loans, which is a group of loans funded by one fiscal year's appropriation. If the subsidy cost estimate proves correct, the cost to the government, outside of the budget authority already provided, will be zero.23

The amount of credit assistance available to borrowers from an amount of budget authority is determined by the subsidy rate after administrative costs are subtracted. The subsidy rate is the subsidy cost as a percentage of the dollars disbursed.24 As an example, if administrative costs are ignored, for every $100 of budget authority at a subsidy rate of 10%, the federal government can loan out $1,000 because it expects to eventually receive back $900 calculated in today's dollars. The budget authority covers the subsidy cost, which in this case is $100. As the subsidy rate declines, the government can provide more credit assistance because it expects a greater amount to be repaid by borrowers. With a subsidy rate of 5%, the TIFIA program could lend $2,000 for every $100 of budget authority ($100/5% = $2,000).

Forecasts of the cost of credit assistance necessarily rely on estimates of the interest rate (a Treasury bond with the same maturity as the loan), the repayment of loans, and the rate of defaults. Because conditions can change, agencies must reestimate the subsidy rate periodically, generally annually, for outstanding loans and loan guarantees. These reestimates appear in the Federal Credit Supplement published in the President's annual budget submission. 25 Estimates and reestimates of the TIFIA subsidy rate are done by DOT in cooperation with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The subsidy rate and its reestimation provide information about the level of risk being undertaken by DOT and the subsequent performance of TIFIA-assisted projects. A single subsidy rate is calculated for all loans originated in a given fiscal year.

The original subsidy rate for TIFIA loans originated in fiscal years with loans still outstanding ranges from 15.16% to 3.36%. The subsidy rate for FY2019 is estimated to be 6.3%. Current reestimates of these original subsidy rates range from -8.06% to 46.12%. The subsidy rate is negative when the government expects to receive repayments greater than the amount of loans, on a net present value basis. The increased (+) or decreased (-) cost to the government of these reestimates is reflected in the net lifetime reestimate amount (Table 1).

Based on the subsidy rate, the cost to the government has been approximately 7 cents for every dollar financed, according to DOT. However, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) notes that this does not take into account the market value of the financial risk to which taxpayers are exposed by federal credit programs such as TIFIA. CBO estimates that including this financial risk the TIFIA program costs 33 cents for every dollar financed.26

|

Fiscal Year |

Original Subsidy Rate |

Current Reestimated Subsidy Rate |

Net Lifetime Reestimate Amount |

|

1999 |

3.36 |

-4.39 |

-8,234 |

|

2003 |

7.10 |

8.08 |

-6,406 |

|

2006 |

8.50 |

-8.06 |

-6,513 |

|

2007 |

3.37 |

9.08 |

+35,120 |

|

2008 |

15.16 |

46.12 |

+392,954 |

|

2009 |

8.69 |

-0.19 |

-87,349 |

|

2010 |

7.74 |

-6.06 |

-287,363 |

|

2012 |

5.50 |

7.05 |

+137 |

|

2013 |

8.87 |

2.17 |

-170,106 |

|

2014 |

6.05 |

-0.51 |

-293,355 |

|

2015 |

7.48 |

3.91 |

-54,834 |

|

2016 |

4.98 |

3.43 |

+5,761 |

|

2017 |

5.28 |

5.64 |

+13,687 |

|

2018 |

6.64 |

NA |

NA |

|

2019 |

6.30 |

NA |

NA |

Source: Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government, FY2019, Federal Credit Supplement, Tables 1 and 7, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/cr_supp-fy2019.pdf.

Notes: NA=Not available. Excludes BUILD (formerly TIGER) Program-funded TIFIA assistance. A negative subsidy rate implies that the government expects to receive repayments greater than the amount of loans, on a net present value basis.

Program Funding

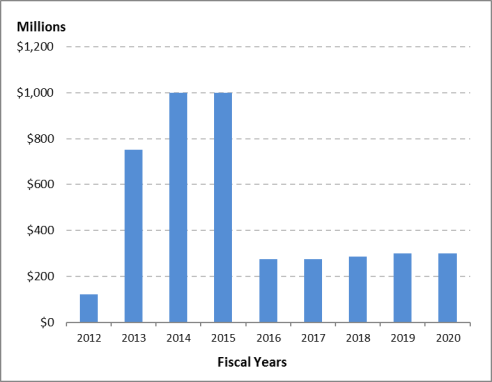

The FAST Act authorized $275 million for the TIFIA program in each of FY2016 and FY2017, $285 million in FY2018, and $300 million in each of FY2019 and FY2020. These amounts are much lower than those authorized in the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21; P.L. 112-141), which greatly enlarged the TIFIA program (Figure 1). Seen in isolation, this reduced DOT's capacity to issue loans by approximately $7.25 billion in FY2016, assuming a 10% subsidy rate and excluding administrative costs.

However, the FAST Act also allows states to use funds from three other highway programs to pay for the subsidy and administrative costs of credit assistance: the discretionary Nationally Significant Freight and Highway Projects Program, known as INFRA grants; the formula National Highway Performance Program; and the formula Surface Transportation Block Grant Program. This use of grant funds has the potential to increase TIFIA financing much above the direct authorization, but at the discretion of state departments of transportation. Payment of the TIFIA subsidy cost has also been allowed as part of the Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development (BUILD) Transportation Discretionary Grants program (formerly TIGER program).

|

Figure 1. TIFIA Program Authorized Funding FY2012-FY2020 |

|

|

Source: Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (P.L. 109-59) and extension acts; Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (P.L. 112-141) and extension acts; Fixing America's Surface Transportation (FAST) Act (P.L. 114-94). Notes: These data show the funding authorized for the TIFIA program directly. Other programs where TIFIA costs are an eligible expense are not included. |

Although direct funding for the TIFIA program was reduced in the FAST Act, DOT has not been limited in providing credit assistance. Funding for the TIFIA program is available until expended, and thus unused money accumulates from year to year. Unobligated budget authority in the TIFIA program was $1.65 billion at the end of FY2018, according to DOT. This amount has accumulated despite a clawback provision in MAP-21 that reduced TIFIA's budget authority by $640 million. The clawback provision was subsequently abolished in the FAST Act, presumably because of the reduction in the TIFIA program's authorization.

Projects Financed

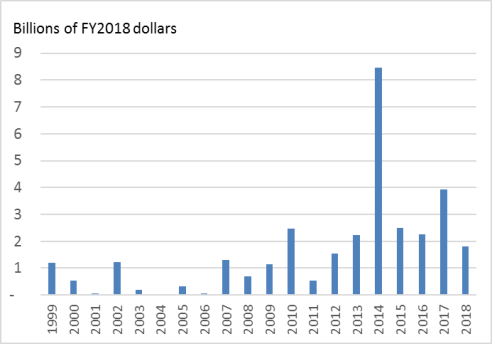

Except for one loan guarantee, every credit agreement under the TIFIA program to date has been a loan. Through FY2018, TIFIA had provided loans worth about $32 billion (in FY2018 inflation-adjusted dollars). The overall cost of the 74 projects supported by TIFIA loans is estimated to be $117 billion (FY2018 dollars).27 The average project cost is about $1.5 billion and the average loan amount $430 million (both in FY2018 dollars). Consequently, the average TIFIA share of project costs has been about 28%. Over the 20-year history of the program, the average number of loans has been about four per year, worth about $1.6 billion (FY2018 dollars). The enlargement of the TIFIA program in FY2013 led to an increase in lending, but much of that occurred in a single year, FY2014 (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2. Value of TIFIA Loans by Year Closed FY1999-FY2018 (inflation-adjusted FY2018 dollars) |

|

|

Source: Department of Transportation, Build America Bureau, "Projects Financed by TIFIA," https://www.transportation.gov/tifia/projects-financed. |

About two-thirds of TIFIA loans have gone to highway and highway bridge projects and another quarter to public transportation. Two loans (3%) have gone to railroad projects and another five (7%) to other surface transportation projects, including a combined parking and public transportation facility at O'Hare International Airport in Chicago.

TIFIA assistance has been geographically limited, with projects in 21 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico receiving financing. Ten states account for about 80% of the 74 projects supported. These are California, Texas, Virginia, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Washington, New York, North Carolina, and Maryland.

User charges, including highway tolls, are the revenue pledge most often made by borrowers, accounting for half of the projects. Various taxes, particularly sales taxes, and general revenues make up most of the other half of project revenue pledges.

At the time of DOT's most recent report to Congress on TIFIA, issued in August 2016, 86% of TIFIA loans were performing as expected, 8% were exceeding expectations, and 6% were performing below expectations.28 Through FY2018, two TIFIA-assisted projects have gone into bankruptcy, the South Bay Expressway toll road project in San Diego, CA, and the SH-130 toll road project (segments 5 and 6) near Austin, TX. The San Diego Association of Governments bought the South Bay Expressway project after it went bankrupt, and, according to DOT, "repaid all outstanding TIFIA indebtedness."29 According to the DOT, the SH-130 TIFIA loan was converted to 34% ownership of the new company that will operate the toll road until 2062, a payment to the government of $15 million, and remaining debt of $87 million. It is uncertain whether the federal government will eventually receive payment equal to the amount of principal and interest that were originally payable on the $430 million TIFIA loan.30

The TIFIA program is the federal government's main tool for encouraging the establishment of public-private partnerships (P3s) and the investment of private capital in surface transportation. The low cost of borrowing, term length, and repayment flexibility can lower financial risk for private investors. P3s offer several advantages over traditional procurement methods, including additional capital, private management expertise, and risk transfer.31 By encouraging private finance and insisting on creditworthiness standards, the program relies, in part, on market discipline to stimulate projects with favorable benefits versus costs.

Although the TIFIA program has supported the creation of P3s and leveraged private capital for transportation projects, government involvement remains more important in TIFIA-supported projects. According to one analysis of the TIFIA program through 2016, about one-third of TIFIA-supported projects (23 projects) were developed as P3s and the other two-thirds were governmentally procured. The 23 P3 projects had total project costs of $33 billion, of which 29% came from government grants, 28% TIFIA loans, 28% other debt, 13% private equity, and 1% other capital.32

TIFIA was initially designed to support large and very costly projects for which grant funding was unlikely to be enough. Despite this, there have been complaints that relatively few projects can take advantage of the program. Most typical highway and public transportation projects cost much less than the TIFIA thresholds for eligibility and have no obvious revenue stream to generate a repayment mechanism. Modifications to the TIFIA program, such as lower cost thresholds, lower interest rates for rural projects, and waived fees for smaller projects, have sought to make financing more accessible. However, to date, the size of TIFIA-supported projects does not appear to have declined. The smallest project since the passage of MAP-21 in July 2012, for example, is the U.S. 36 Managed Lane/Bus Rapid Transit Project between Boulder and Denver, CO, which had a total cost of $175 million. But this is phase 2 of a project that totaled almost $500 million. Moreover, there have been no TIFIA loans to rural project funds.

Issues for Congress

Funding

In addition to the use of direct program funding, TIFIA assistance can be obtained by using other federal-aid highway funds, both discretionary and formula, and discretionary BUILD program (formerly TIGER program) funds. There have been a few BUILD program-funded TIFIA loans, but to date no states have traded formula grant funding for a larger loan. At the moment, states do not have to make that trade because the TIFIA program is not in danger of running out of budget authority. DOT calculated that unobligated budget authority in the TIFIA program at the end of FY2018 was $1.65 billion. This amount of end of fiscal year unobligated budget authority is much higher now than it was in FY2012, but the level has stabilized over the past few years (Table 2).

|

End of Fiscal Year |

Unobligated Budget Authority |

|

2012 |

0.25 |

|

2013 |

0.82 |

|

2014 |

1.32 |

|

2015 |

1.38 |

|

2016 |

1.53 |

|

2017 |

1.57 |

|

2018 |

1.65 |

Source: Department of Transportation, communication with CRS, February 11, 2019.

If the TIFIA program does exhaust its direct funding in the future, an unanswered question is whether states will choose to use grant funding to pay the subsidy and administrative costs of a loan. A similar option, the capitalization of a state infrastructure bank with grant funds, has largely gone unused, partly because states have planned to commit these funds to traditional projects years in advance.

Congress could increase the lending capacity of the TIFIA program by authorizing and appropriating additional funding.33 However, there may not be enough suitable projects to make use of significantly greater budget authority, even if eligibility is expanded beyond surface transportation to include port, aviation, and economic development projects. To date, the greatest value of loans issued in any year has been about $8 billion. The average since the expansion of the program in FY2013 has been about $3.5 billion (in FY2018 dollars).

More applications for credit assistance might result from lowering the fees and other costs associated with federal support. One option is to reduce the fees for projects of $75 million or more. All else equal, however, this would increase the administrative costs of the program and reduce its lending capacity. Another option is to increase the threshold below which one credit agency rating is needed rather than two on the senior debt and the federal credit instrument. Currently, the threshold is $75 million, but S. 3631 (115th Congress) proposed to increase it to $150 million.

Calculation of Subsidy Cost

The calculation of the TIFIA program's subsidy cost has generally been conservative. To date, two TIFIA-financed projects have gone bankrupt, and, according to DOT, 6% of loans were underperforming in 2016. A less conservative calculation by DOT and OMB could allow DOT to lend a greater amount with the same amount of budget authority.34

It does appear that the federal government has adjusted its subsidy cost estimates downward over the past few years in recognition of DOT's loss experience under the TIFIA program. However, the lack of defaults may be due to the types of projects being assisted and the generally favorable economic conditions. An enlarged TIFIA program might mean assisting more risky projects, leading to a higher subsidy rate, all else being equal. The 20-year experience of the TIFIA program, furthermore, is possibly less informative than it appears. The share of loans that have been fully repaid is about 15%. Many of the projects that have received assistance are permitted to defer interest and principal payments and have very long amortization schedules, so there is still a great deal of uncertainty as to how they will perform over the long term. For example, the I-495 high occupancy toll (HOT) lanes project in Northern Virginia received credit assistance in 2007 and the lanes opened in 2012, but interest payments did not begin until 2017. Principal repayments are not scheduled to begin until 2032, and are to continue until loan maturity in 2047.

Ultimately, decisions about the level of risk that the TIFIA program is willing to take are made by DOT's Credit Council and the Secretary of Transportation within the limits of the program's statutory requirements. However, a critic of TIFIA's decisions on risk has suggested developing "an underlying risk framework and underwriting standards within which loans can be negotiated," and "creating a federal advisory committee to evaluate industry trends and periodically assess the effectiveness of TIFIA's risk framework in meeting its policy objectives."35

Federal Share

MAP-21 greatly enlarged the TIFIA program and at the same time raised the maximum federal share from 33% to 49% of eligible project costs. However, DOT announced after the statutory change that it would typically provide up to 33% and would provide amounts between 33% and 49% only in exceptional circumstances. To date, no project has received more than 33%. TIFIA appears to be maximizing its leveraging of nonfederal resources, but it may be limiting the projects that could use a larger share of TIFIA assistance. For example, the American Public Transportation Association has argued that an increased federal share "would enable TIFIA credit assistance to meaningfully support certain projects with large public benefits that may be difficult to finance conventionally without federal credit support, while still ensuring other investors share in project costs and risks."36

Federal Share for Major Public Transportation Capital Projects

By statute, the Secretary of Transportation may consider a TIFIA loan as part of the nonfederal share for federally funded highway and public transportation projects if the loan is repaid from nonfederal funds.37 For major public transportation capital projects seeking funding from the federal Capital Investment Grant (CIG) program (also known as "New Starts"), the Trump Administration has decided that it "considers U.S. Department of Transportation loans in the context of all Federal funding sources requested by the project sponsor when completing the CIG evaluation process, and not separate from the Federal funding sources."38 In the CIG program, the maximum federal share of a project is 80%, although the share of funding permissible from the CIG program alone is lower.39 If projects seeking CIG grant funding receive unfavorable ratings because they are also proposing to use large TIFIA loans, then CIG project sponsors are more likely to request smaller TIFIA loans or perhaps to seek alternatives to TIFIA program financing. Low ratings on transit projects drawing on TIFIA loans could also stop them from moving forward. An option for Congress, such as H.R. 731 (116th Congress), is to require TIFIA loans to be considered part of the nonfederal share of surface transportation projects.

Speed of Administrative Decisionmaking

Some project sponsors have stated that the process for obtaining TIFIA assistance led them not to seek TIFIA loans. A number of proposals have been suggested to speed up approvals, such as regular and more frequent DOT credit council meetings, increased administrative spending to more quickly assess applications, regular publication of information on the time it takes to reach application milestones, and changes to the Letter of Interest process to provide greater schedule certainty.40 The FAST Act required DOT to expedite projects thought to be lower-risk—those requesting $100 million or less in credit assistance with a dedicated revenue stream unrelated to project performance and standard loan terms—but it is not clear what effect this could have, as only two projects have received TIFIA loans of less than $100 million since the passage of the FAST Act. S. 3631 (115th Congress) proposed additional criteria for expedited loans for public agency borrowers. Other options, though possibly more controversial, would be to expedite reviews with experienced sponsors or to prioritize the evaluation of certain projects, such as those with national benefits or that involve significant private capital, over others.41

Broadening Eligible Uses of TIFIA Loans

The Trump Administration has proposed broadening the eligibility of TIFIA assistance from highways and public transportation to ports and airports. S. 3647 (115th Congress) would have allowed $10 million in TIFIA program funds to pay the subsidy costs of credit assistance to airport-related projects. One reason TIFIA eligibility has been limited to surface transportation projects is that funding for the program comes from the Highway Trust Fund (HTF), which traditionally has been supported by revenues from highway users. Now that the HTF has relied heavily on general Treasury funds for a decade, Congress may want to revisit this limitation.42 If TIFIA were to begin making loans to a broader set of projects, DOT likely would need to bring in expertise to provide analysis and advice on these new sectors.

Another option for broadening eligibility is to create a new entity such as a national infrastructure bank. Such proposals in the 115th Congress include the National Infrastructure Development Bank Act of 2017 (H.R. 547), the Partnership to Build America Act of 2017 (H.R. 1669), and the Building and Renewing Infrastructure for Development and Growth in Employment (BRIDGE) Act (S. 1168). Most proposals include a wide range of infrastructure projects, including transportation, water, energy, and telecommunications infrastructure. One purported advantage of a national infrastructure bank over other loan programs, such as TIFIA, is that it would have more independence in its operation, such as in project selection, and have greater expertise at its disposal.

Most infrastructure bank proposals assume the bank would improve the allocation of public resources by funding projects with the highest economic returns regardless of infrastructure system or type. Selection of the projects with the highest returns, however, might conflict with the traditional desire of Congress to ensure funding for various types of projects. In the extreme case, major transportation projects might not be funded if the bank were to exhaust its lending authority on water or energy projects offering higher returns.

The limitations of a national infrastructure bank include its duplication of existing programs like TIFIA. Most legislative proposals for infrastructure banks do not address this duplication, leading to questions about how each would run in parallel. Would a national infrastructure bank avoid current TIFIA-type projects or would it "compete" with the TIFIA program to finance these projects? The addition of a national infrastructure bank seems unlikely to increase the number of surface transportation projects involving major credit assistance without other substantial changes in the way such projects are typically funded and financed.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

23 U.S.C. §601 et seq. |

| 2. |

CRS Report R45010, Public-Private Partnerships (P3s) in Transportation, by William J. Mallett. |

| 3. |

In this report, amounts given in FY2018 inflation-adjusted dollars have been calculated by CRS using the gross domestic product deflator. |

| 4. |

CRS Report R43315, Water Infrastructure Financing: The Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) Program, by Jonathan L. Ramseur and Mary Tiemann. |

| 5. |

White House, Legislative Outline for Rebuilding Infrastructure in America, February 12, 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/INFRASTRUCTURE-211.pdf. |

| 6. |

Department of Transportation, Build America Bureau, Credit Programs Guide, March 2017, p. 2-2, https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/policy-initiatives/programs-and-services/tifia/Bureau%20Credit%20Programs%20Guide_March_2017.pdf. |

| 7. |

A rural projects fund is a state infrastructure bank account that is designed to provide credit assistance to relatively less costly projects (23 U.S.C. §601(a)(16)). |

| 8. |

Credit assistance is also permissible if a project's costs are greater than one-third of a state's federal highway formula funds. |

| 9. |

Other eligibility requirements are fostering a public-private partnership, if appropriate; enabling the project to proceed more quickly; reducing the contribution of federal grant funding; satisfying planning and environmental review requirements; and being ready to contract out construction within 90 days after the obligation of assistance. |

| 10. |

Department of Transportation, Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act: 2016 Report to Congress, p. 11. |

| 11. |

Testimony of Anne Mayer, Executive Director, Riverside County Transportation Commission, U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, The Use of TIFIA and Innovative Financing in Improving Infrastructure to Enhance Safety, Mobility, and Economic Opportunity, 115th Cong., July 12, 2017, p. 7, https://www.epw.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/2/7/27b383e6-3fae-4279-9e99-822dc4906bd9/9871398AB56D5AA163C4E63C353B8E58.anne-mayer-testimony-07.12.17.pdf. |

| 12. |

Department of Transportation, Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act: 2016 Report to Congress, pp. 12-13. |

| 13. |

23 U.S.C. §601(a)(6). |

| 14. |

Department of Transportation, Build America Bureau, Credit Programs Guide, March 2017, pp. 4-11. |

| 15. |

23 U.S.C. §605(f). |

| 16. |

23 U.S.C. §602(d). |

| 17. |

The DOT Council on Credit and Finance is composed of five representatives from the Office of the Secretary of Transportation—the Deputy Secretary of Transportation (Chair), the Assistant Secretary for Budget and Programs (Vice-Chair), the Under Secretary of Transportation for Policy, the General Counsel, and the Assistant Secretary for Transportation Policy—and the administrators of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), and the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA). The Secretary may also designate up to three DOT officials to serve as at-large members of the council. |

| 18. |

23 U.S.C. §602(c). |

| 19. |

Testimony of Jennifer Aument, Group General Manager, North America Transurban, U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, The Use of TIFIA and Innovative Financing in Improving Infrastructure to Enhance Safety, Mobility, and Economic Opportunity, 115th Cong., 1st sess., July 12, 2017, p. 10, https://www.epw.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/b1847bbb-683a-481a-9134-25d8b0ef4eaf/jennifer-aument-testimony-07.12.17.pdf. |

| 20. |

Testimony of Jennifer Aument; Testimony of Anne Mayer. |

| 21. |

2 U.S.C. §661(a). |

| 22. |

Net present value is the estimated value today of a series of future cash flows. A more detailed discussion of net present value can be found in Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-94, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/circulars/A94/a094.pdf. |

| 23. |

Douglas J. Elliott, Budgeting for Credit Programs: A Primer, Center on Federal Financial Institutions, April 7, 2004. |

| 24. |

Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government, FY2019, Federal Credit Supplement, p. v, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/cr_supp-fy2019.pdf. |

| 25. |

Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government, FY2019, Federal Credit Supplement, p. v, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/cr_supp-fy2019.pdf. |

| 26. |

Congressional Budget Office, Federal Support for Financing State and Local Transportation and Water Infrastructure, October 2018, p. 4, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2018-10/54549-InfrastructureFinancing.pdf. |

| 27. |

Department of Transportation, Build America Bureau, "Projects Financed by TIFIA," https://www.transportation.gov/tifia/projects-financed. |

| 28. |

Department of Transportation, Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act: 2016 Report to Congress, https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/TIFIA%20Report%20to%20Congress%202016.pdf. |

| 29. |

Department of Transportation, TIFIA Projects Financed: South Bay Expressway, https://www.transportation.gov/tifia/financed-projects/south-bay-expressway. |

| 30. |

CRS In Focus IF10735, Risks and Rewards of Transportation Public-Private Partnerships (P3s), with Lessons from Texas and Indiana, by William J. Mallett. |

| 31. |

CRS Report R45010, Public-Private Partnerships (P3s) in Transportation, by William J. Mallett. |

| 32. |

Bryan Grote, "TIFIA Reality Check," Public Works Financing, January 2017, pp. 5-7. |

| 33. |

A funding increase of $10 billion per year, which could be enough to support an additional $100 billion of loans annually, was recommended by Roger C. Altman, Aaron Klein, and Alan B. Krueger, "Financing U.S. Transportation Infrastructure in the 21st Century," Brookings Institution, Hamilton Project, Discussion Paper 2015-04, May 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/financing_us_infrastructure_altman_klein_krueger.pdf. |

| 34. |

Ibid., p. 12. |

| 35. |

Testimony of Jennifer Aument, Group General Manager, North America Transurban, U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, The Use of TIFIA and Innovative Financing in Improving Infrastructure to Enhance Safety, Mobility, and Economic Opportunity, 115th Cong., 1st sess., July 12, 2017. |

| 36. |

American Public Transportation Association, Invest in Public Transportation for a Stronger America Appendix: Finance Recommendations, 2017, p. 5, https://www.apta.com/members/memberprogramsandservices/advocacyandoutreachtools/august-extension-toolkit/Documents/2018%200108%20APTA%20Infrastructure%20Initiative%20Financing%20Appendix.pdf. |

| 37. |

"The proceeds of a secured loan under the TIFIA program may be used for any non-Federal share of project costs required under this title or chapter 53 of title 49, if the loan is repayable from non-Federal funds" (23 U.S.C. 603(b)(8)). |

| 38. |

Federal Transit Administration, "Dear Colleague Letter - Capital Investment Grants Program," June 29, 2018, https://www.transit.dot.gov/sites/fta.dot.gov/files/docs/regulations-and-guidance/policy-letters/117056/fta-dear-colleague-letter-capital-investment-grants-june2018_0.pdf. |

| 39. |

49 U.S.C. §5309(l). Provisions in appropriations acts also have often lowered this share. For example, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), requires that "none of the funds made available in this Act shall be used to enter into a full funding grant agreement for a project with a New Starts share greater than 51 percent." |

| 40. |

Testimony of Anne Mayer, Executive Director, Riverside County Transportation Commission, U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, The Use of TIFIA and Innovative Financing in Improving Infrastructure to Enhance Safety, Mobility, and Economic Opportunity, 115th Cong., 1st sess., July 12, 2017. |

| 41. |

Testimony of Jennifer Aument, Group General Manager, North America Transurban, U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, The Use of TIFIA and Innovative Financing in Improving Infrastructure to Enhance Safety, Mobility, and Economic Opportunity, 115th Cong., 1st sess., July 12, 2017. |

| 42. |

CRS Report R45350, Funding and Financing Highways and Public Transportation, by Robert S. Kirk and William J. Mallett. |