Social Media Adoption by Members of Congress: Trends and Congressional Considerations

Communication between Members of Congress and their constituents has changed with the development of online social networking services. Many Members now use email, official websites, blogs, YouTube channels, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms to communicate—technologies that were nonexistent or not widely available just a few decades ago.

Social networking services have arguably enhanced the ability of Members of Congress to fulfill their representational duties by providing them with greater opportunities to share information and potentially to gauge constituent preferences in a real-time manner. In addition, electronic communication has reduced the marginal cost of communications. Unlike with postal letters, social media can allow Members to reach large numbers of constituents for a fixed cost.

This report examines Member adoption of social media broadly. Because congressional adoption of long-standing social media platforms Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube is nearly ubiquitous, this report focuses on the adoption of other, newer social media platforms. These include Instagram, Flickr, and Google+, which have each been adopted by at least 2.5% of Representatives and Senators. Additionally, Members of Congress have adopted Snapchat, Medium, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Periscope, and Tumblr at lower levels. This report evaluates the adoption rates of various social media platforms and what the adoption of multiple platforms might mean for an office’s social media strategy. Data on congressional adoption of social media were collected by an academic institution in collaboration with the Congressional Research Service during the 2016-2017 academic year.

This report provides a snapshot of a dynamic process. As with any new technology, the number of Members using any single social media platform, and the patterns of use, may change rapidly in short periods of time. As a result, the conclusions drawn from these data cannot necessarily be generalized or used to predict future behavior.

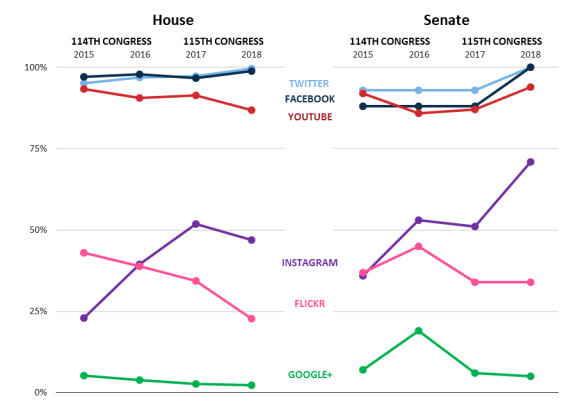

The data show that, on average, Members of Congress adopt six social media platforms for official communications. Between 87% and 100% of Representatives and 94% and 100% of Senators have adopted the established platforms—Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube—during the 114th Congress (2015-2016) and the 115th Congress (2017-2018). These adoption rates generally match the popularity of these services among the general public. Instagram, Flickr, and Google+ are the most popular of the newer social media platforms. Among Senators, Instagram has been the most adopted platform, with between 36% (2015) and 71% (2018) of Senators having adopted it. For Flickr, between 34% (2017 and 2018) and 45% (2016) of Senators have adopted the service, and for Google+ between 5% (2018) and 19% (2016). For Representatives, Instagram was also the most adopted of the newer platforms, with between 23% (2015) and 52% (2017) of Representatives adopting the service. For Flickr, between 23% (2018) and 43% (2015) of Representatives have accounts, and for Google+ between 2.3% (2018) and 5.2% (2015) have adopted the platform.

Additionally, this report discusses the possible implications of the adoption of social media, including managing multiple platforms, the type of content and posting location, the allocation of office resources to social media communications, and archiving social media content.

Social Media Adoption by Members of Congress: Trends and Congressional Considerations

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Research Overview and Methodology

- Adoption of Social Media

- Established Platforms

- Newer Platforms

- Congressional Considerations

- Managing Multiple Platforms

- Type of Content and Posting Location

- Allocation of Office Resources

- Archiving Communications

- Concluding Observations

- Social Media and Congressional History

- Future Studies on Member Social Media Usage

Figures

Appendixes

Summary

Communication between Members of Congress and their constituents has changed with the development of online social networking services. Many Members now use email, official websites, blogs, YouTube channels, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms to communicate—technologies that were nonexistent or not widely available just a few decades ago.

Social networking services have arguably enhanced the ability of Members of Congress to fulfill their representational duties by providing them with greater opportunities to share information and potentially to gauge constituent preferences in a real-time manner. In addition, electronic communication has reduced the marginal cost of communications. Unlike with postal letters, social media can allow Members to reach large numbers of constituents for a fixed cost.

This report examines Member adoption of social media broadly. Because congressional adoption of long-standing social media platforms Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube is nearly ubiquitous, this report focuses on the adoption of other, newer social media platforms. These include Instagram, Flickr, and Google+, which have each been adopted by at least 2.5% of Representatives and Senators. Additionally, Members of Congress have adopted Snapchat, Medium, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Periscope, and Tumblr at lower levels. This report evaluates the adoption rates of various social media platforms and what the adoption of multiple platforms might mean for an office's social media strategy. Data on congressional adoption of social media were collected by an academic institution in collaboration with the Congressional Research Service during the 2016-2017 academic year.

This report provides a snapshot of a dynamic process. As with any new technology, the number of Members using any single social media platform, and the patterns of use, may change rapidly in short periods of time. As a result, the conclusions drawn from these data cannot necessarily be generalized or used to predict future behavior.

The data show that, on average, Members of Congress adopt six social media platforms for official communications. Between 87% and 100% of Representatives and 94% and 100% of Senators have adopted the established platforms—Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube—during the 114th Congress (2015-2016) and the 115th Congress (2017-2018). These adoption rates generally match the popularity of these services among the general public. Instagram, Flickr, and Google+ are the most popular of the newer social media platforms. Among Senators, Instagram has been the most adopted platform, with between 36% (2015) and 71% (2018) of Senators having adopted it. For Flickr, between 34% (2017 and 2018) and 45% (2016) of Senators have adopted the service, and for Google+ between 5% (2018) and 19% (2016). For Representatives, Instagram was also the most adopted of the newer platforms, with between 23% (2015) and 52% (2017) of Representatives adopting the service. For Flickr, between 23% (2018) and 43% (2015) of Representatives have accounts, and for Google+ between 2.3% (2018) and 5.2% (2015) have adopted the platform.

Additionally, this report discusses the possible implications of the adoption of social media, including managing multiple platforms, the type of content and posting location, the allocation of office resources to social media communications, and archiving social media content.

Introduction

Congressional communications continues to evolve. As Members of Congress adopt new online social networking services, more information is potentially available faster than ever before. Many Members now use email, official websites, YouTube channels, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flickr, Google+, Medium, and other networking platforms to share information with and collect information from their followers. Many of these technologies were either nonexistent or not widely available several years ago.

Around 2009, Members of Congress began adopting social media as an additional way to share information. At that time, Members who had adopted Twitter—the first platform widely adopted by Representatives and Senators—most often used it as a tool to send out information. Since that time, Members of Congress have primarily adopted three social media platforms—Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube—to share information and potentially to collect opinions on a range of policy issues.

In addition to Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, Members of Congress have adopted various other social media services. Some platforms appear to be gaining in popularity among Members of Congress (e.g., Instagram, which has grown from approximately 25% of Members with accounts in 2015 to more than 50% in 2017), whereas others were briefly popular but have now faded from public relevance (e.g., in June 2014, 26% of Members had a Vine account; today the service has been shut down and no Members of Congress have accounts).1 As various social media platforms expand and diminish in popularity, Members of Congress continue to explore new platforms to enhance their communications strategies.

Social media have arguably enhanced the ability of Members of Congress to fulfill their representational duties by providing greater opportunities for communications between Members and constituents, supporting the fundamental democratic role of sharing information about public policy and government operations.2 Despite this, some have raised concerns about electronic communications. These include managing social media content and interactions, allocating office resources, and archiving communications.

This report examines Member adoption of social media broadly. Today, the adoption of Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube by Members of Congress is nearly ubiquitous. Therefore, this report focuses not only on adoption of these platforms, but also on the adoption of other social media platforms—Instagram, Flickr, Google+, Snapchat, Medium, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Periscope, and Tumblr—to evaluate which platforms are being adopted, how adoption has changed over time, and what the use of multiple social media platforms might mean for Member communication (see Appendix for a brief description of the most popular social media platforms adopted by Members of Congress).

Research Overview and Methodology

Members of Congress have been using social media since at least 2009, when the first Representatives and Senators adopted Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. Today, nearly all Members of Congress have Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube accounts, and many have also registered official accounts with other social media services. The following examination of social media adoption by Members of Congress is divided into two parts:

- 1. the adoption of established platforms—Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube—over time; and

- 2. the adoption of newer platforms in the 114th and 115th Congresses.

Following the analysis of social media adoption, the report focuses on potential consequences of social media adoption, and the adoption of multiple platforms, on Member communications practices and office operations. These considerations include managing multiple platforms, the type of content and posting location, the allocation of office resources to social media communications, and archiving social media content.

During the 2016-2017 academic year (September 2016 to May 2017), CRS partnered with graduate students at the Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas to collect and analyze the adoption of social media by Members of Congress. Data on social media platform adoption were collected by visiting the official webpages of individual Representatives and Senators to determine which social media platforms were linked to each Member's webpage and by searching each platform and the internet for official accounts that were not linked to each Member's webpage. Additionally, using the same methodology—visiting Representatives' and Senators' webpages—data were collected by CRS for the first session of the 114th Congress (2015) and the 115th Congress (2017-2018). These data were used to analyze Member adoption of social media over a four-year period.

Several caveats accompany the results presented. First, the analysis treats all Member social media posts as structurally identical, because an individual tweet, snap, or post rarely reveals information about who physically typed the message. In some cases, Members might personally tweet, snap, or post, whereas other Members may delegate these responsibilities to staff. This analysis draws no distinctions between the two. Second, the analysis covers only a relatively short period of the congressional calendar. Therefore, it is inherently a snapshot in time of a dynamic process. As with any new technology, the number of Members signed up for any particular social media platform and the patterns of adoption may change in short periods of time. Thus, the conclusions drawn from these data cannot necessarily be generalized. Finally, these results cannot be used to predict future behavior.

Adoption of Social Media

Members of Congress have many choices when deciding which social media platforms to adopt. Social media can be roughly divided into two categories: established platforms and newer platforms. This section discusses Member adoption of both types of social media and the number of platforms that Representatives and Senators have adopted in the 114th Congress and the 115th Congress.

Established Platforms

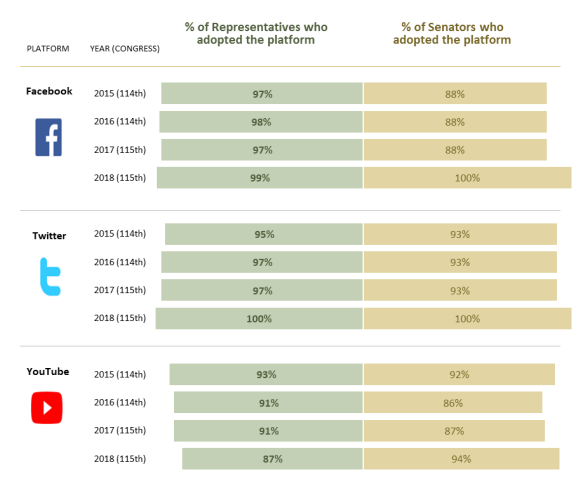

In 2009, the first studies of social media adoption by Members of Congress were published. In September 2009, 38% of Members—205, composed of 39 Senators and 166 Representatives—had a registered Twitter account.3 By January 2012, the number of Members with an official Twitter account had doubled, with a total of 78.7% of Members having an official Twitter account and 87.2% having an official congressional Facebook account.4 Today, nearly all Members of Congress have accounts on the three oldest platforms—Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Figure 1 shows the percentage of Representatives and Senators who have adopted Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube in the 114th Congress (2015-2016) and the 115th Congress (2017-2018).

As Figure 1 shows, the number of Representatives and Senators who have adopted Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube has remained relatively consistent between 2015 and 2018. For Facebook, between 97% and 99% of Representatives and 88% and 100% of Senators have accounts. For Twitter, between 95% and 100% of Representatives and 93% and 100% of Senators have accounts. YouTube has the biggest variation over this time period, with adoption between 87% and 93% for Representatives and between 86% and 94% for Senators.

The adoption of established platforms by Members of Congress appears to generally follow the popular use of these services among the general public. For example, a recent Pew Research Center study found that 73% of adults report that they use YouTube and 68% use Facebook. Twitter is third, with 24% of adults reporting regular usage.5 Although all three established platforms are more popular within Congress than among the general public, congressional adoption might be a reaction to the overall popularity of these services among the public.

Newer Platforms

In addition to Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, Members of Congress are adopting a variety of additional social media services. The evaluation of congressional social media adoption by CRS and the LBJ School of Public Affairs found a total of nine additional services that have been adopted by Representatives and Senators. They are Instagram, Flickr, Google+, Snapchat, Medium, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Periscope, and Tumblr. Figure 2 shows the percentage of Representatives and Senators who have created accounts on the six most-adopted social media platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

Among all Members of Congress, Instagram, Flickr, and Google+ are the most popular of the new social media platforms. As Figure 2 shows, by far the most popular of these platforms is Instagram, with nearly a majority of House Members and almost 75% of Senators having adopted the platform in 2018. In combination with the adoption of Flickr over the last several years, Members of Congress have shown an interest in adopting platforms that allow them to share pictures. The adoption of Google+, although generally on the decline, might show that Members of Congress were looking to reach as wide an audience as possible, including individuals who might be loyal to Google or reluctant to adopt Facebook or Twitter.6

Whereas Figure 2 shows the most commonly adopted social media platforms, Table 1 shows the percentage of Representatives and Senators who have adopted these and other social media platforms. These others include LinkedIn, Tumblr, Pinterest, Snapchat, Medium, and Vine. Data for LinkedIn, Tumblr, and Pinterest were not collected in 2017. Vine was shut down by Twitter in 2017.7 Member adoption of Vine peaked in 2015 and was not included as a link on Member webpages beginning in 2016.8 Additionally, there are several platforms or services that have been adopted by less than 1% of Representatives and Senators, including Periscope, Storify, SoundCloud, and Picasa. These platforms are not included in Table 1.

|

House |

Senate |

Overall |

||||||||

|

Congress |

114th |

115th |

114th |

115th |

114th |

115th |

||||

|

Year |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2015 |

2018 |

|

|

97.0% |

97.9% |

96.8% |

98.8% |

88.0% |

88.0% |

88.0% |

100.0% |

95.4% |

98.9% |

|

|

95.2% |

97.0% |

97.2% |

99.8% |

93.0% |

93.0% |

93.0% |

100.0% |

94.8% |

99.6% |

|

YouTube |

93.4% |

90.6% |

91.5% |

86.9% |

92.0% |

86.0% |

87.0% |

94.0% |

93.1% |

81.1% |

|

|

23.0% |

39.4% |

51.8% |

47.0% |

36.0% |

53.0% |

51.0% |

71.0% |

25.4% |

51.4% |

|

Flickr |

43.0% |

38.9% |

34.3% |

22.8% |

37.0% |

45.0% |

34.0% |

34.0% |

41.9% |

24.9% |

|

Google+ |

5.2% |

3.9% |

2.8% |

2.3% |

7.0% |

19.0% |

6.0% |

5.0% |

5.6% |

2.8% |

|

|

1.1% |

7.6% |

— |

0.5% |

— |

1.0% |

— |

1.0% |

0.9% |

0.6% |

|

Tumblr |

2.3% |

1.6% |

— |

0.7% |

1.0% |

3.0% |

— |

— |

2.0% |

0.6% |

|

|

2.7% |

1.8% |

— |

0.7% |

1.0% |

9.0% |

— |

1.0% |

2.4% |

0.7% |

|

Snapchat |

— |

0.9% |

0.9% |

1.6% |

— |

— |

2.0% |

1.0% |

— |

1.5% |

|

Medium |

— |

1.2% |

2.1% |

2.8% |

— |

13.0% |

5.0% |

10.0% |

— |

4.1% |

|

Vine |

0.9% |

— |

— |

— |

1.0% |

— |

— |

— |

0.9% |

— |

Source: CRS analysis of Member adoption data.

Notes: Cells marked with "—" indicate that those social media services were not found in the analysis of social media adoption conducted during that time period. Percentages represent a snapshot of platform adoption at the time of collection during the Congress mentioned.

Outside of the top three new platforms, only Medium (used by 13% of Senators in 2016 and 10% in 2018), Pinterest (9% of Senators in 2016), and LinkedIn (7.6% of Representatives in 2016) had more than 5% of Representatives or Senators adopt their services over the 114th and 115th Congresses. The relatively low percentages of Members of Congress who have adopted these services suggest that new social media platforms may not appeal broadly to Representatives and Senators in the same way as the more established environments. In at least some instances, these newer services had features similar to other, more widely adopted social media platforms, and some appear to be newer platforms that Members of Congress have not adopted in large numbers, but are being evaluated by some offices.

For example, Periscope allows users to share live video, something that Facebook also provides through Facebook Live. Periscope adoption has never been widespread among Members of Congress, perhaps because of the similarities with Facebook Live. Snapchat—which provides the ability to share brief content with other users (in a way similar to Twitter)—shows a different pattern, as it appears to be growing both among the general population9 and among congressional users. Data suggest that the number of Snapchat users among Members of Congress might be growing slowly.

Congressional Considerations

The decision to adopt and use social media is not without potential costs, as Members likely have to devote some finite resources to managing their social media presence. Those decisions might include managing multiple platforms, creating policies on the type of content shared and where it is posted, allocating resources, and archiving communications.

Managing Multiple Platforms

As discussed above, social media platforms can be divided into established platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube that generally provide users with the ability to post multiple types of content (e.g., video, pictures, and text), or newer platforms that generally, though not universally, specialize in a single type of media.10 In order to provide followers with a variety of information, Member offices generally adopt a variety of platforms and use them to share information in potentially different ways. Past studies have found that Members use the internet more for the dissemination of information than interactivity.11 Initial assessments of social media have come to a similar conclusion; the potential for interactivity exists, but most Members use the services to share information rather than to more actively engage constituents.12

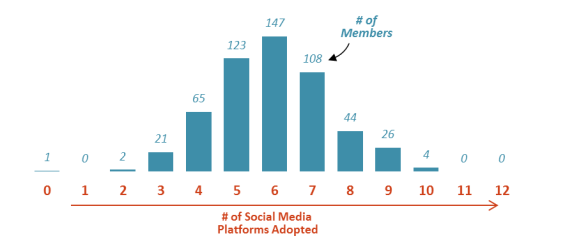

Members of Congress generally adopt more than one social media platform. As of December 2016, all but one Member of Congress had adopted at least one social media platform, with a median and a mode of six platforms adopted. Additionally, in the 114th Congress, four Members had adopted 10 platforms for official business. Figure 3 shows the number of social media platforms adopted by Members of Congress.

As Figure 3 shows, in the 114th Congress, a majority of Members had adopted six or more social media platforms. Since the median and mode are six platforms, those who have adopted more might be considered heavy social media users, whereas those who have adopted fewer might be considered light users. Using the quartile distribution of adopted platforms, a pattern of adoption can be observed: a light social media user has adopted between zero and four platforms, an average user has adopted between five and seven platforms, and a heavy adopter has signed up with eight or more services.

Even though the average Member adopted and used six platforms in the 114th Congress, an examination of data collected by the LBJ School suggests that the more platforms a Member adopts, the less of an active presence might be maintained across all social media accounts.13 Additionally, the data indicate that among the most heavily adopted platforms, there appears to be a divergence between adoption and usage. With the exception of the established platforms, older social media sites (e.g., Google+, Flickr, and LinkedIn) have a higher rate of "zombie" accounts, where a user had maintained a profile but has not recently posted content. This potentially suggests that Representatives and Senators use non-Facebook and non-Twitter accounts to evaluate the type of content that might be posted to various services, but as Twitter and Facebook continue to add new features, Members return to those platforms for much of their social media communications.14

Managing multiple platforms can be complicated and time consuming. This may be reflected in the choice of Members to continue Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube use over other social media sites. If Members of Congress want to reach geographic constituents, they are also more likely to find larger numbers of them on Facebook and Twitter than on other social media sites, since more Americans have adopted Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube than other social media services.15 The consumer focus on Facebook and Twitter in lieu of other platforms partially reflects the perceived usefulness of various social media technologies for sharing and consuming information. Marketing research suggests that age, gender, and education play a role in the perceived usefulness of social media platforms.16 Members may want to be on platforms that users find useful as a way to connect with followers across multiple demographics.

By focusing on legacy platforms, Representatives and Senators might be able to maximize their reach and provide information to (or interact with) a greater number of users. Concentrating on using a few platforms, however, could result in missed opportunities to engage users of other forums. Individuals who do not use Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube might be unlikely to see official information from their Members of Congress17 if those messages are not posted on the platforms they are actively using. This may result in a failure by users "to fully exploit the capabilities of social media platforms."18

Type of Content and Posting Location

The choice to adopt multiple social media platforms introduces questions about usage. Specifically, Members must decide what content to post on which platform and how to coordinate messaging across multiple services. Generally, users want to maximize their reach and choices, but not all social media sites are necessarily ideal for certain content.19

The balance among how many platforms to adopt, how often to post content, and the type of content is a decision that may be made based on a Member's representational style and expectations. Some Members might want to post content across multiple social media sites in an effort to have a broad reach.20 Although posting across multiple social media sites might reach a broader audience, without planning, the type of content cross-posted might not match a site's strengths. For example, as one social media observer commented,

sharing images on Twitter via Instagram used to be a simple affair—allowing seamless photo sharing from Instaland to the Twittersphere. Times were simple, life was good. That is until Instagram went and dumped Twitter (and broke all our hearts in the process). Technically, auto-posting is still possible, but it ain't pretty. Where once there were lovely images featured, auto-posted tweets now convert those images into links (that often appear cut off).That's right, a timeline filled with imageless tweets and unsightly links.21

Instead, research suggests that users may consider the best type of content to be posted to each social media platform.22 For example, if a Representative were hosting a town hall event, his or her staff might want to post a live feed to Facebook for those who cannot be present using Facebook Live, still photographs of the event to Instagram, brief summaries to Twitter, a full video of the event to YouTube, and a postevent summary to Medium. Holistically, these posts would have the potential to reach a variety of different users; provide them with a variety of content; and potentially allow their users to visit other social media sites for more, or different, information about the event.

Generating content to post on multiple social media sites, however, is not without potential costs of time, effort, and other resources. If a Member's staff is managing multiple social media outlets, they may need to consciously think about what type of material might send a single message across multiple outlets. For example, certain types of material might be better suited for a specific platform, such as

- Facebook: videos and curated content;

- Instagram: high-resolution photos, quotations, and stories;23

- Twitter: news, blog posts, and GIFs;

- LinkedIn: jobs and professional content;

- Pinterest: infographics; and

- Google+: blog posts that you want to rank on Google.24

Ultimately, using a manageable mix of platform types might allow Members of Congress to reach a broader audience. Reaching those individuals, however, likely requires that Representatives and Senators have a strategy for the type of content they post, whether or not they will respond to other users, and which platforms they choose to utilize. A recent study of social media usage among Fortune 500 companies found that "social [media] was an add-on to existing plans" rather than a tool unto itself.25 Subsequently, many companies have "found themselves working backwards to connect their social media strategies to business strategy."26

Members of Congress do not necessarily face the same types of considerations that a business faces, but they do have representational duties to keep constituents informed about their activities both in Washington, DC, and in their home district or state. In fact, past research has found that direct mail communication from a Member to constituents boosts a Member's saliency within his or her district.27 Although that study focused on the use of franked mail, the results are potentially translatable to social media. The more often a Member can put content in front of constituents, the more likely the constituents will be aware of the Member's activity and potentially have a positive impression of the Representative's or Senator's actions.

Allocation of Office Resources

Allocation of resources is a fundamental building block of the practices of congressional office operation. The decision on how to allocate staff and other resources reflects the priorities of the Member. Constituent service and communications is an important aspect of Members' personal office activity, but it is far from the only important endeavor. Members must choose how to balance communications resources against other legislative and oversight responsibilities. Consequently, Representatives and Senators choose to allocate resources, including staff, in different ways.28

The increased use of electronic communications has put increased pressure on these allocation decisions. To the degree that more staff time needs to be allocated to collecting, processing, and responding to social media, less time might be available for other work. The number of staffers working in personal offices has increased modestly in the last generation (about a 4% increase in House Members' offices since 1982).29 Therefore, there may not be resources to hire additional communication staff without reducing staffing in other areas.

There are indications that social media is adding to this pressure about how best to allocate resources. One study found that in the 113th Congress (2013-2014), 16% of Senators had staff members with "social media" or "new media" in their job titles.30 By the 115th Congress (2017-2018), the share of Senators with social media staff had doubled to 32%.31 The growth of social media staff reflects the continued importance of electronic media in staff resource allocation.32 If an office chooses to use social media only to share information—much like a press release—it is possible that existing staff levels could be sufficient to manage social media accounts. If, however, Members want social media to be interactive, existing resource allocations may or may not be sufficient to handle the need to respond in a timely manner.

Offices might also consider the potential time commitments when deciding whether the Member, staff, or both are posting to social media, especially across multiple platforms. If staff is posting for a Member, office policies likely need to be established to ensure that all social media posts meet the Member's legislative and representational priorities.

Archiving Communications

All records generated by a Member of Congress in the course of his or her service in the House or Senate are the personal property of the Member.33 This includes records such as email, websites, draft legislation, correspondence, databases, and, potentially, social media postings. Unlike other materials, however, social media posts are not housed on a government server. Instead, they are hosted by a private entity whose terms of service the Representative or Senator agreed to. Both the House and the Senate have developed policies to govern Member use of social media with official resources,34 but no specific congressional guidance has been issued on the archiving of individual Member social media posts.35 All congressional guidance regarding potential disposition, however, is designed to be format neutral, and record management decisions are to be on the content of the material, rather than the format in which it was created. In general, the Senate Archivist and the House Office of Art and Archives provide guidance to Members and committees in their respective chambers on archiving matters, including social media postings.

For Congress, since each Representative and Senator owns his or her own personal records, the decision about how and what to archive is up to each individual office. Members who actively use social media may want to establish archiving policies similar to those of their other official papers. The method by which the Representative or Senator might choose to archive posts would likely depend on the type of content posted, the frequency of the posts, and the best technological practices available when archiving material.36

Some Representatives or Senators might choose not to formally archive their social media posts, since they are already in the public domain. Others, however, might choose to establish a policy for the preservation of these materials and include them with their other personal records.

Concluding Observations

The nature of the communication between Members of Congress and constituents continues to evolve. In light of the adoption of multiple social media platforms, several potential implications exist for the continued use of social media as a communications tool. These include the potential value of archiving for understanding congressional history, and future studies on Member use of social media.

Social Media and Congressional History

Traditionally, official House or Senate records have been used to study policy development, understand past congressional action, and provide the courts with congressional intent.37 In some cases, the personal papers of Members of Congress might be used to understand how a particular public policy issue developed. Accessing these papers, however, is often difficult because they are scattered around the country, with some in public or university libraries and others located out of public view in attics, basements, or other family collections. The advent of social media provides a new opportunity to potentially include the online correspondence of individual Members as part of the public policy record. Since Member tweets, Facebook posts, and other social media items are in the public domain on the social media services' platforms, interested parties might be able to use those to help understand public policy development.38

Future Studies on Member Social Media Usage

This report focused on social media adoption by Members of Congress. Although the adoption of new technology provides an important insight into the communication and potential interaction with constituents, it does not provide insight into how Members of Congress use social media to communicate their message and potentially receive feedback from their state or district. Future studies of social media might utilize machine learning or other similar technology to reveal patterns of social media use across Congress.39 Such a study could provide better insight into how Members share information, the type of information they post on various platforms, and whether or not they are using social media to solicit constituent opinions to help them formulate positions on policy issues.

Appendix. Social Media Platform Descriptions

Members of Congress have more choices and options available to communicate with constituents than ever before. These include legacy platforms (Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube) and new platforms (Instagram, Flickr, Google+, Snapchat, Medium, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Periscope, and Tumblr). A description of legacy platforms and new platforms is provided below.

Members of Congress have been widely using three social media platforms since at least 2009: Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Analysis of adoption and use of these platforms by Members of Congress has found that nearly all Members have signed up and use these platforms to share text, video, and pictures with constituents.40

Founded in 2006, Twitter is a social networking service that allows users to send and read short messages.41 Also considered a microblogging site, Twitter users send "tweets" of up to 280 characters.42 These tweets often contain short videos, photos, and other visual media and give the user the ability to direct a message to another user, resend another user's message (i.e., retweet), or provide labels (i.e., hashtags) to make searching for a particular topic easier. Recently, Twitter also incorporated a live-video function, in cooperation with its subsidiary Periscope, to allow users to broadcast events.43

Launched in February 2004, Facebook is the world's largest social networking service and website.44 Facebook users create "profiles"45 and "pages"46 to share pictures, videos, and messages, upon which other users ("followers") may post comments. Users can limit the visibility of their profile posts to other users whom they have personally approved ("friends"). A Facebook user can become a fan of a page, however, simply by clicking "like" on the Facebook page of interest; owner approval is often not required.

YouTube was founded in 2005 and has become one of the most popular video platforms on the internet. Currently, YouTube is owned by Google. YouTube describes its mission as an opportunity to "give everyone a voice and show them the world," based on four essential freedoms: freedom of expression, freedom of information, freedom of opportunity, and freedom to belong.47 YouTube allows users to both watch and upload videos. A YouTube account is not required to watch videos, but a user must sign up to post video content.

Social media are constantly evolving. Consequently, the number and types of platforms that Members of Congress adopt and use is varied. Following a survey of Representative and Senator webpages (see "Research Overview and Methodology" above for a description of that search), nine platforms in addition to Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube had at least 1% of Members signed up for their services in an official (noncampaign) capacity. These are Instagram, Flickr, Google+, Snapchat, Medium, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Periscope, and Tumblr.

Launched in 2010, and acquired by Facebook in 2012, Instagram is a photo-based social media service that allows users to post pictures along with text captions.48 Instagram also allows photographs to be edited with various tools to enhance images and create stories.49 More than 800 million registered users post more than 250 million daily stories.50

Founded in 2004, Flickr is a photo library owned by Yahoo!. One of the original photo curation websites, Flickr's stated goal is to "help people make their photos available to people who matter to them," and to "enable new ways of organizing photos and video."51 Flickr provides users with 1,000 GB of free storage.52

Founded in 2011, Google+ is Google's social network. Originally perceived by the media to be a competitor to Facebook,53 Google+ accounts are given to anyone who has a regular Google account.54 Google+ allows users to post photos and status updates to their personal stream or to interest-based communities.

Founded in 2011, Snapchat is a social media service available only through a smart device (i.e., smart phone or tablet) application. Snapchat's premise is to allow users to send and receive pictures and messages that are short-lived.55 Snapchat's emphasis is on allowing users to share their point of view, and the application features a camera when it is opened to encourage the user to share what he or she is seeing at that moment.56

Launched in 2012 by Twitter cofounder Evan Williams as a supplement to Twitter's then-140-character limit, Medium combines an open publishing blogging platform with social media features to create a product that has led to what has been referred to as social journalism.57 Medium bills itself as a platform that allows users to interact with other users' articles and to create their own content.

Founded in 2003, LinkedIn is a professional networking platform that allows users to connect with other individuals and potential employers.58 LinkedIn users can create a professional network, exchange ideas, and potentially find new employment opportunities that match their interests and network connections.

Started in 2010, Pinterest states that it "began as a tool to help people collect things they were passionate about online."59 Currently, more than 200 million people use Pinterest every month.60 Each user can share visual information by posting "pins" on "boards" that are used as filters for the user. Other users can then browse the boards to find others who share similar interests and inspirations.

Founded in 2014, Periscope is a live video streaming platform used on mobile devices that enables users to broadcast their activities as a live video.61 Currently owned by Twitter, Periscope's live video features have largely been incorporated into Twitter's platform.

Founded in 2007, Tumblr is a blogging platform specializing in social network microblogging.62 Users can create their own blogs, post their own material, and reshare content written by other Tumblr users. In addition to providing a microblogging platform, Tumblr also has a feature that allows users to ask posters anonymous questions about the written subject material.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Former CRS analyst Matthew E. Glassman also contributed to this research. Amber Wilhelm, CRS graphics specialist, created all figures in this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

"Vine Update," December 16, 2016, at https://medium.com/@vine/vine-update-59426a5adfab. For more information on the congressional use of Vine, see CRS Report R43691, Social Networking and Constituent Communications: Members' Use of Vine in Congress, by Jacob R. Straus, Matthew E. Glassman, and Raymond T. Williams. |

| 2. |

Alfred A. Porro and Stuart A. Ascher, "The Case for the Congressional Franking Privilege," University of Toledo Law Review, vol. 5 (Winter 1974), pp. 280-281. |

| 3. |

For information on the early adoption of Twitter by Members of Congress, see CRS Report R41066, Social Networking and Constituent Communications: Member Use of Twitter During a Two-Month Period in the 111th Congress, by Matthew E. Glassman, Jacob R. Straus, and Colleen J. Shogan. |

| 4. |

For information on Member adoption of Twitter and Facebook, see CRS Report R44081, Social Networking and Committee Communications: Use of Twitter and Facebook in the 113th Congress, by Jacob R. Straus and Matthew E. Glassman. |

| 5. |

Aaron Smith and Monica Anderson, Social Media Use in 2018, Pew Research Center, March 1, 2018, at http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/. See also M. Hisham M. Sharif, Indrit Troshani, and Robyn Davidson, "Public Sector Adoption of Social Media," Journal of Computer Information Systems, vol. 55, no. 4 (Summer 2015), pp. 53-61. |

| 6. |

Karissa Bell, "A Lot of People Still Use Google+; They're Just Not Who You Think," Mashable, January 18, 2017, at https://mashable.com/2017/01/18/who-is-using-google-plus-anyway/#ycMFZr4WJiqZ. |

| 7. |

Tom Hunddleston Jr., "Twitter is Officially Shutting Down Vine Today," Fortune, January 17, 2017, at http://fortune.com/2017/01/17/twitter-shut-down-vine-tuesday/. |

| 8. |

For more information on Member adoption of Vine, see CRS In Focus IF10458, Congressional Adoption of Vine, by Jacob R. Straus and Matthew E. Glassman; and CRS Report R43691, Social Networking and Constituent Communications: Members' Use of Vine in Congress, by Jacob R. Straus, Matthew E. Glassman, and Raymond T. Williams. |

| 9. |

Aaron Smith and Monica Anderson, Social Media Use in 2018, Pew Research Center, March 1, 2018, at http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/. |

| 10. |

YouTube is an exception to this classification. It is a widely adopted legacy platform that specializes in a single type of media—sharing videos. |

| 11. |

Maureen Taylor and Michael L. Kent, "Congressional Web Sites and Their Potential for Public Dialogue," Atlantic Journal of Communication, vol. 12, no. 2 (2004), pp. 59-76. |

| 12. |

For example, see Jacob R. Straus, Raymond, T. Williams, Colleen J. Shogan, and Matthew E. Glassman, "Congressional Social Media Communications: Evaluating Senate Twitter Usage," Online Information Review, vol. 40, no. 5 (2016), pp. 648, 652. |

| 13. |

Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, Congress & Social Media: Beyond Facebook and Twitter, Report No. 195, May 12, 2017, at https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/61941/prp_195-beyond_facebook_and_twitter-2017.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y. Similar patterns of multiple platform adoption and challenges with maintaining a single message have been found in corporate use of social media. See Robert E. Montalvo, "Social Media Management," International Journal of Management & Information Systems, vol. 20, issue 2 (2016). |

| 14. |

For example, see Aatif Sulleyman, "Facebook Trials New Feature Linking Accounts to Instagram, LinkedIn and Snapchat Profiles," The Independent, February 20, 2017, at https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/news/facebook-latest-news-feature-user-profiles-social-media-linkedin-snapchat-youtube-twitter-pinterest-a7589376.html; and Sarah Perez, "Twitter Officially Launches 'Threads,' A New Feature for Easily Posting Tweetstorms," Tech Crunch, December 12, 2017, at https://techcrunch.com/2017/12/12/twitter-officially-launches-threads-a-new-feature-for-easily-writing-tweetstorms. |

| 15. |

Michael A. Stelzner, "2017 Social Media Marketing Industry Report: How Marketers are Using Social Media to Grow their Businesses," Social Media Examiner, May 2017, at http://www.socialmediaexaminer.com/report2017/. |

| 16. |

Brad Sago, "Factors Influencing Social Media Adoption and Frequency of Use: An Examination of Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+," International Journal of Business and Commerce, vol. 3, no. 1 (September 2013), pp. 1-14. |

| 17. |

Aaron Smith and Monica Anderson, "Social Media Use in 2018: A Majority of Americans Use Facebook and Twitter, but Young Adults are Especially Heavy Users of Snapchat and Instagram," Pew Research Center, March 1, 2018, at http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/. |

| 18. |

Mary J. Culnan, Patrick J. McHugh, and Jesus I. Zubillaga, "How Large U.S. Companies Can use Twitter and Other Social Media to Gain Business Value," MIS Quarterly Executive, vol. 9, no. 4 (December 2010), p. 243. |

| 19. |

W. Glynn Mangold and David J. Faulds, "Social Media: The New Hybrid Element of the Promotion Mix," Business Horizons, vol. 52, no 4 (July-August 2009), p. 358. |

| 20. |

David Meerman Scott, The New Rules of Marketing & PR : How to Use Social Media, Online Video, Mobile Applications, Blogs, New Releases, and Viral Marketing to Reach Buyers Directly, 5th ed. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2015), pp. 68-71; Richard Hanna, Andrew Rohm, and Victoria L. Crittenden, "We're All Connected: The Power of Social Media Ecosystem," Business Horizons, vol. 54, no 3 (May-June 2011), pp. 265-273; and Wen-ying Sylvia Chou, Yvonne M. Hunt, Ellen Burke Beckjord, Richard P. Moser, and Bradford W. Hesse, "Social Media Use in the United States: Implications for Health Communication," Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 11, no. 4 (October-December 2009), at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2802563/. |

| 21. |

Jylian Russell, "Why It's Time to Ditch Cross-Posting on Social Media for Cross-Promoting," Hootsuite Blog, May 3, 2017, at https://blog.hootsuite.com/cross-promote-social-media/. |

| 22. |

Russell, "Ditch Cross-Posting." |

| 23. |

See Appendix for a discussion of Instagram stories. |

| 24. |

Alfred Lua, "What to Post on Each Social Media Platform: The Complete Guide to Optimizing Your Social Content," Entrepreneur, November 30, 2017, at https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/305168. |

| 25. |

Keith A. Quesenberry, "The Basic Social Media Mistakes Companies Still Make," Harvard Business Review, January 2, 2018, at https://hbr.org/2018/01/the-basic-social-media-mistakes-companies-still-make. |

| 26. |

Quesenberry, "Basic Social Media Mistakes." |

| 27. |

Albert D. Cover and Bruce S. Brumberg, "Baby Books and Ballots: The Impact of Congressional Mail on Constituent Opinion," American Political Science Review, vol. 76, no. 2 (June 1982), pp. 347-359. |

| 28. |

For more information on the allocation of financial resources in Member offices, see CRS Report R40962, Members' Representational Allowance: History and Usage, by Ida A. Brudnick. |

| 29. |

CRS Report R43947, House of Representatives Staff Levels in Member, Committee, Leadership, and Other Offices, 1977-2016, by R. Eric Petersen and Amber Hope Wilhelm. |

| 30. |

Straus, Williams, Shogan, and Glassman, "Congressional Social Media Communications," p. 653. |

| 31. |

Jacob R. Straus, "Fake Followers in the Senate," presented at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association, New Orleans, LA, January 4-7, 2018, p. 12. |

| 32. |

Although having "social media" or "new media" in a job title likely indicates that that staffer is spending a significant portion of his or her job on these tools, it does not guarantee that others in the office are not also managing online communications or social media without those specific words in their job titles. The opposite is also true—just because a staffer's job title includes "social media" or "new media" does not guarantee that he or she is not also engaged in other activities. The move to label jobs with "social media" or "new media" in their titles, however, does indicate that those Senators see the potential of having staff that primarily focuses on these new forms of communications. |

| 33. |

U.S. Congress, House, "Rule VII: Records of the House," Constitution, Jefferson's Manual, and Rules of the House of Representatives of the United States, One Hundred Fifteenth Congress, 114th Cong., 2nd sess., H.Doc. 114-192 (Washington: GPO, 2017), §§695-696, at https://rules.house.gov/HouseRulesManual115/rule7.xml; U.S. Congress, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Office of Art and Archives, Records Management Manual for Members, February 2014, at https://housenet.house.gov/sites/housenet.house.gov/files/documents/Records-Management-Manual-for-Members_0.pdf; U.S. Congress, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Office of Art and Archives, Records Management Manual for Committees, November 2013, at https://housenet.house.gov/sites/housenet.house.gov/files/documents/archives-manual-WEB-03.pdf; and U.S. Congress, Secretary of the Senate, Senate Historical Office, Records Management Handbook for United States Senate Committees, 109th Cong., 1st sess., S.Pub. 109-111 (Washington: GPO, 2005). Note: Housenet is available only within the House of Representatives. |

| 34. |

U.S. Congress, House, Committee on House Administration, Members' Congressional Handbook, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., February 27, 2018, at https://cha.house.gov/handbooks/members-congressional-handbook; and U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Rules and Administration, Internet Services and Technology Resources Usage Rules, 114th Cong., 1st sess., November 9, 2015, at https://www.senate.gov/usage/internetpolicy.htm. |

| 35. |

Both the House and Senate have specific guidance for the archiving of committee social media posts. In the House, committee and committee related social media records may be subject to House Rule XI, clause 2(e), which requires that committees keep a complete record of all committee actions. See U.S. Congress, House, Committee on House Administration, Committees' Congressional Handbook, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., February 27, 2018, at https://cha.house.gov/handbooks/committee-handbook/. Also see U.S. Congress, House, "Rules XI, clause 2(e)—Committee Records," Constitution, Jefferson's Manual, and Rules of the House of Representatives of the United States One Hundred Fifteenth Congress, 114th Cong., 2nd sess., H.Doc. 114-192 (Washington: GPO, 2017), at https://rules.house.gov/HouseRulesManual115/rule11.xml. In the Senate, committee records are property of the Senate pursuant to Rule XXVI, clause 10. See U.S. Congress, Senate, "Rule XXVI—Committee Procedure," Standing Rules of the Senate, 113th Cong., 1st sess., S.Doc. 113-18, January 24, 2013 (Washington: GPO, 2013), p. 36, at https://www.rules.senate.gov/rules-of-the-senate. |

| 36. |

John Carlo Bertot, Paul T. Jaeger, and Derek Hansen, "The Impact of Policies on Government Social Media Usage: Issues, Challenges, and Recommendations," Government Information Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 1 (2012), pp. 30-40. |

| 37. |

For some examples of the use of legislative history and congressional records in the legal community, see Stephen Breyer, "The 1991 Justice Lester W. Roth Lecture: On the Uses of Legislative History in Interpreting Statutes," Southern California Law Review, vol. 65, no. 2 (January 1992), pp. 844-874; Kenneth W. Starr, "Observations about the Use of Legislative History," Duke Law Journal, vol. 1987, no. 3 (June 1987), pp. 271-379; and Patricia M. Wald, "Some Observations on the Use of Legislative History in the 1981 Supreme Court Term," Iowa Law Review, vol. 68, no. 2 (January 1983), pp. 195-216. |

| 38. |

For example, see Jennifer Golbeck, Justin Grimes, and Anthony Rogers, "Twitter Use by the U.S. Congress," Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, vol. 61, no. 8 (August 2010), pp. 1612-1621; CRS Report R40823, Social Networking and Constituent Communication: Member Use of Twitter During a Two-Week Period in the 111th Congress, by Matthew E. Glassman, Jacob R. Straus, and Colleen J. Shogan; CRS Report R41066, Social Networking and Constituent Communications: Member Use of Twitter During a Two-Month Period in the 111th Congress, by Matthew E. Glassman, Jacob R. Straus, and Colleen J. Shogan; and CRS Report R43018, Social Networking and Constituent Communications: Members' Use of Twitter and Facebook During a Two-Month Period in the 112th Congress, by Matthew E. Glassman, Jacob R. Straus, and Colleen J. Shogan. |

| 39. |

For example, see Muhammad Imran, Carlos Castillo, Fernando Diaz, and Sarah Vieweg, "Processing Social Media Messages in Mass Emergencies: A Survey," ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 47, no. 4 (July 2015), article no. 67, at https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2771588; and Kyumin Lee, James Caverlee, Zhiyuan Cheng, and Daniel Z. Sui, "Campaign Extraction from Social Media," ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, vol. 5, issue 1 (December 2013), article no. 9, at https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2542191. |

| 40. |

Jacob R. Straus, Raymond, T. Williams, Colleen J. Shogan, and Matthew E. Glassman, "Congressional Social Media Communications: Evaluating Senate Twitter Usage," Online Information Review, vol. 40, no. 5 (2016), pp. 643-659. |

| 41. |

Twitter, "Twitter Company," at https://about.twitter.com/. For more information about social networking, see Danah M. Boyd and Nicole B. Ellison, "Social Networking Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship," Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 13, no. 1 (October 2007), pp. 210-230; and Lee Humphreys, "Mobile Social Networks and Social Practice: A Case Study of Dodgeball," Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 13, no. 1 (October 2007), pp. 341-360. |

| 42. |

In November 2017, Twitter increased its character limit per tweet from 140 to 280. Twitter, "Tweeting Made Easier," November 7, 2017, at https://blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/topics/product/2017/tweetingmadeeasier.html. |

| 43. |

Twitter, "How to Create Live Videos on Twitter," https://help.twitter.com/en/using-twitter/twitter-live; and Periscope on Twitter, "You can now link Periscope to your Twitter web profile, making it easier for followers to discover and watch your live videos!" October 4, 2016, at https://twitter.com/periscopeco/status/783336320114450432?lang=en. |

| 44. |

Ashlee Vance, "Facebook: The Making of 1 Billion Users," Bloomberg Businessweek, October 4, 2012, at http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2012-10-04/facebook-the-making-of-1-billion-users. |

| 45. |

A profile or timeline is each user's "collection of the photos, stories, and experiences that tell [their] story." For more information, see "profile" on Facebook, "Facebook Glossary," at http://www.facebook.com/help/glossary; and Facebook, "Timeline," at http://www.facebook.com/help/timeline. |

| 46. |

A Facebook page "allow[s] businesses, brands, and celebrities to connect with people on Facebook. Admins can post information and News Feed updates to people who like their pages." For more information, see "Page," on Facebook, "Facebook Glossary," at http://www.facebook.com/help/glossary. |

| 47. |

YouTube, "About," at https://www.youtube.com/intl/en/yt/about/. |

| 48. |

Instagram, "Our Story," at https://instagram-press.com/our-story/. |

| 49. |

Instagram, "Our Story." |

| 50. |

Instagram, "Our Story." |

| 51. |

Flickr, "About Flickr," at https://www.flickr.com/about. |

| 52. |

Yahoo!, "Get Started with Flickr," at https://help.yahoo.com/kb/flickr-for-desktop/started-flickr-sln24639.html?impressions=true. |

| 53. |

Steven Winkelman, "5 Social Media Networks That are Still Alive and Kicking, But We Don't Know Why," Digital Trends, December 26, 2017, at https://www.digitaltrends.com/social-media/unpopular-social-media-sites-that-are-still-around/. |

| 54. |

Google, "About Google+," at https://plus.google.com/about. |

| 55. |

Snapchat, "How Snaps Are Stored and Deleted," May 9, 2013, at https://www.snap.com/en-US/news/page/7/. |

| 56. |

Snapchat, "Introducing Our Story," June 17, 2014, https://www.snap.com/en-US/news/page/5/. |

| 57. |

Medium, "Welcome to Medium, Where Words Matter," at https://medium.com/about. |

| 58. |

LinkedIn, "About LinkedIn," at https://about.linkedin.com/. |

| 59. |

Pinterest, "A Brief History," at https://newsroom.pinterest.com/en/company. |

| 60. |

Pinterest, "A Brief History." |

| 61. |

Periscope, "About Us," at https://www.periscope.tv/about. |

| 62. |

Microblogging services allow users to post short-form blogs. Whereas blogs "are webpages authored by an individual or group in which entries are published in reverse chronological order, microblogs are largely similar, but [are] limited in the total number of characters that may be published per entry." For more information, see Stephen A. Rains, "Blogging, Microblogging, and Exposure to Health and Risk Messages," Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, 2017, at http://communication.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-327. |