Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Reauthorization Issues and Debate in the 115th Congress

On April 27, 2018, the House of Representatives passed the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 (H.R. 4), a six-year Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) reauthorization measure that does not include a controversial proposal to privatize air traffic control laid (ATC) out in an earlier bill, H.R. 2997. On May 9, 2018, the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation reported a four-year FAA reauthorization bill (S. 1405, S.Rept. 115-243) that does not address ATC privatization. The enactment of either bill would be the first long-term FAA reauthorization act since the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-95) expired at the end of FY2015.

Despite many similarities, there are a number of differences in the two bills, including the length of authorization, funding amounts, and other provisions. Key differences include the following:

S. 1405 would authorize funding to aviation programs from FY2018 through FY2021, while funding authorization in H.R. 4 would cover two additional years, through FY2023. H.R. 4 would provide higher annual funding.

H.R. 4 would establish a pilot program to provide air traffic services on a preferential basis to aircraft equipped with upgraded avionics compatible with FAA’s NextGen ATC system, while S. 1405 would require FAA to identify barriers to complying with the current 2020 equipage deadline.

H.R. 4 proposes a number of actions to address noise complaints attributed to NextGen procedures, while S. 1405 addresses noise concerns by clarifying the availability of certain airport grant funds for noise mitigation programs.

While both bills would establish a process for certifying drone package delivery operations, S. 1405 addresses the privacy policies of unmanned aircraft operators and would require FAA to establish a public database of unmanned aircraft to aid with compliance and enforcement of airspace restrictions and applicable regulations.

Whereas S. 1405 would allow FAA to revise airline pilot qualification standards to allow certain ground instruction to count toward the 1,500 flight-hour minimum, H.R. 4 does not propose any changes to the current requirements.

H.R. 4 would create a new supplemental funding authorization for Airport Improvement Program (AIP) discretionary funds from the general fund appropriations, exceeding $1 billion each year. Large hub airports would not be eligible for these funds.

H.R. 4 would make involuntary bumping of passengers after boarding an unfair and deceptive practice. It would also allow an air carrier to advertise base airfare rather than the final cost to the passenger, as long as it discloses additional taxes and fees via a link on its website. Such practice is currently deemed “unfair and deceptive” by a Department of Transportation (DOT) consumer protection rule.

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Reauthorization Issues and Debate in the 115th Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Status of Legislation

- Key Issues in Legislative Debate

- Aviation Funding

- FAA Funding Accounts

- Airport Financing

- Airport Improvement Program (AIP)

- Funding Distribution

- Distribution of AIP Grants by Airport Size

- The Federal Share of AIP Matching Funds

- Passenger Facility Charges

- Airport Privatization

- The Interests at Stake

- The Airport Privatization Pilot Program (APPP)

- Next Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen) Implementation

- Avionics Equipage

- NextGen and Community Noise

- Regulation of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS)

- Aviation Safety Issues

- Aircraft and Parts Certification

- Drug and Alcohol Testing and Substance Abuse Programs

- Airline Pilot Training and Qualifications

- Pilot and Flight Attendant Fatigue

- Age-Based Retirements for Certain Nonairline Pilots

- Global Aircraft Tracking and Flight Data Recorders

- Runway Safety

- Carriage of Lithium Batteries

- Helicopter Fuel System Safety

- FAA Organizational Issues

- Air Traffic Control (ATC) Reforms

- Controller Workforce Initiatives

- Facilities Consolidation

- Facilities Security, Cybersecurity, and Resiliency

- Oversight of Commercial Space Activities

- FAA Research and Development

- Essential Air Service (EAS)

- EAS Funding and Subsidies

- Policy Enforcement

- Airline Consumer Issues

- Passenger Rights Provisions

Summary

On April 27, 2018, the House of Representatives passed the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 (H.R. 4), a six-year Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) reauthorization measure that does not include a controversial proposal to privatize air traffic control laid (ATC) out in an earlier bill, H.R. 2997. On May 9, 2018, the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation reported a four-year FAA reauthorization bill (S. 1405, S.Rept. 115-243) that does not address ATC privatization. The enactment of either bill would be the first long-term FAA reauthorization act since the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-95) expired at the end of FY2015.

Despite many similarities, there are a number of differences in the two bills, including the length of authorization, funding amounts, and other provisions. Key differences include the following:

- S. 1405 would authorize funding to aviation programs from FY2018 through FY2021, while funding authorization in H.R. 4 would cover two additional years, through FY2023. H.R. 4 would provide higher annual funding.

- H.R. 4 would establish a pilot program to provide air traffic services on a preferential basis to aircraft equipped with upgraded avionics compatible with FAA's NextGen ATC system, while S. 1405 would require FAA to identify barriers to complying with the current 2020 equipage deadline.

- H.R. 4 proposes a number of actions to address noise complaints attributed to NextGen procedures, while S. 1405 addresses noise concerns by clarifying the availability of certain airport grant funds for noise mitigation programs.

- While both bills would establish a process for certifying drone package delivery operations, S. 1405 addresses the privacy policies of unmanned aircraft operators and would require FAA to establish a public database of unmanned aircraft to aid with compliance and enforcement of airspace restrictions and applicable regulations.

- Whereas S. 1405 would allow FAA to revise airline pilot qualification standards to allow certain ground instruction to count toward the 1,500 flight-hour minimum, H.R. 4 does not propose any changes to the current requirements.

- H.R. 4 would create a new supplemental funding authorization for Airport Improvement Program (AIP) discretionary funds from the general fund appropriations, exceeding $1 billion each year. Large hub airports would not be eligible for these funds.

- H.R. 4 would make involuntary bumping of passengers after boarding an unfair and deceptive practice. It would also allow an air carrier to advertise base airfare rather than the final cost to the passenger, as long as it discloses additional taxes and fees via a link on its website. Such practice is currently deemed "unfair and deceptive" by a Department of Transportation (DOT) consumer protection rule.

Status of Legislation

On April 27, 2018, the House of Representatives passed the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 (H.R. 4), a measure to reauthorize federal civil aviation programs, including the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), for a six-year period. H.R. 4 does not include a controversial proposal to privatize air traffic control (ATC) laid out in an earlier bill, H.R. 2997. On May 9, 2018, the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation reported a four-year FAA reauthorization bill (S. 1405, S.Rept. 115-243) that does not address ATC privatization. Despite many similarities, there are a number of differences in the two bills, including the length of authorization, funding amounts, and other provisions.

If either bill is enacted, it would be the first long-term FAA reauthorization act since the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-95) expired at the end of FY2015. Disagreement regarding ATC reforms has stalled action on a subsequent long-term FAA bill for almost three years, leading the 114th Congress to approve a series of extensions, including a one-year extension (P.L. 114-190) that expired at the end of FY2017. That act included a number of provisions addressing key aviation safety and security concerns. The 115th Congress passed a six-month extension (P.L. 115-63) of aviation funding and programs through the end of March 2018. Subsequently, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), further extended authorization for aviation programs and airport and airway trust fund revenue authority through the end of FY2018.

Key Issues in Legislative Debate

Proposals to reform ATC have been central to the legislative debate. FAA reauthorization measures considered in the House during the 114th Congress (H.R. 4441) and the 115th Congress (H.R. 2997) both included detailed provisions to establish a not-for-profit private corporation to provide the air traffic services currently delivered by FAA. In contrast, the Senate bills (S. 2658, 114th Congress, and S. 1405) have not included any ATC reforms. On January 27, 2018, Representative Bill Shuster, chairman of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, announced that he would no longer insist on restructuring of ATC operations,1 and on April 13, 2018, he introduced H.R. 4, which did not include ATC privatization language. An alternative plan to move ATC out of FAA but retain it under the Department of Transportation (DOT) was proposed as an amendment to H.R. 4, but the amendment was not adopted.

While privatization of ATC is no longer moving forward in either house, many in Congress continue to be interested in encouraging privatization of airports by expanding an existing pilot program. Changes to grant allocations for airport improvements remain in both H.R. 4 and S. 1405, but proposals to raise long-standing caps on passenger facility charges collected by airports have not been included in either the House bill or the Senate committee bill.

Other key issues in the debate have included concerns related to implementation of NextGen, FAA's plan for modernizing ATC, including options for encouraging aircraft owners to install needed avionics and addressing community noise impacts associated with flight path changes implemented to improve air traffic efficiency and capacity. Both bills include language to promote adoption of unmanned aircraft for commercial uses, such as inspection of critical infrastructure and package delivery, that involve flight beyond the aircraft operator's line of sight. The legislation also seeks to address aircraft parts certification processes, air carrier and repair station safety oversight, consolidation of ATC facilities, and FAA's oversight of the rapidly growing commercial space industry.

In addition to FAA, the reauthorization bills would extend the Essential Air Service (EAS) program, which subsidizes commercial flights to small communities, and would address various airline consumer issues including the manner in which airfares are advertised and the size and spacing of aircraft seats.

Aviation Funding

Most FAA programs are financed through the Airport and Airway Trust Fund (AATF),2 sometimes referred to as the Aviation Trust Fund. The AATF was established in 1970 under the Airport and Airway Development Act of 1970 (P.L. 91-258) to provide for expansion of the nation's airports and air traffic system. Between FY2014 and FY2018, the AATF has provided between 80% and 95% of FAA's total annual funding, with the remainder coming from general fund appropriations.3 Revenue sources for the trust fund include passenger ticket taxes, segment fees, air cargo fees, and fuel taxes paid by both commercial and general aviation aircraft (see Table 1).

|

Tax or Fee |

Rate |

|

Passenger ticket tax (on domestic ticket purchases and frequent flyer awards) |

7.5% |

|

Flight segment tax (domestic, indexed annually to Consumer Price Index) |

$4.20 |

|

Cargo waybill tax |

6.25% |

|

Frequent flyer tax |

7.5% |

|

General aviation gasolinea |

19.3 cents/gallon |

|

General aviation jet fuela (kerosene) |

21.8 cents/gallon |

|

Commercial jet fuela (kerosene) |

4.3 cents/gallon |

|

International departure/arrivals tax (indexed annually to Consumer Price Index) |

$18.30 |

|

Fractional ownership surtax on general aviation jet fuel |

14.1 cents/gallon |

In addition to excise taxes deposited into the trust fund, FAA imposes air traffic service fees on flights that transit U.S.-controlled airspace but do not take off from or land in the United States. These overflight fees partially fund the EAS program.4

In 2017, the AATF had revenues of over $15 billion and maintained a cash balance of nearly $15 billion. The uncommitted balance was estimated to be approximately $5.9 billion at the end of FY2018, reversing several years of decline following the onset of the global economic crisis in 2008.5 The trust fund balance is projected to grow in the near term, as AATF revenue continues to rise and airport capital needs are projected to decline over the next five years.

Changes in airline business practices may pose a risk to the AATF revenue structure. Trust fund revenue is largely dependent on airlines' ticket sales, and the spread of low-cost air carrier models has held down ticket prices and therefore AATF receipts. In addition, airlines increasingly impose fees for a variety of options and amenities, such as checked bags and onboard meals, rather than including them in the base ticket price. Generally, fees not included in the base ticket price are not subject to federal excise taxes. Air carriers generated over $4.57 billion in baggage fees alone in 2017, which would have brought more than $343 million into the trust fund had they been subject to the 7.5% ticket tax.6 This subject is not addressed in either H.R. 4 or S. 1405.

FAA Funding Accounts

In recent years, FAA funding has totaled between $15 billion and $18 billion annually. Most recently, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), provided funding through the end of FY2018.

FAA funding is divided among four main accounts. The largest account, Operations and Maintenance (O&M), principally funds air traffic operations and aviation safety programs. The Airport Improvement Program (AIP) provides federal grants-in-aid for projects such as new runways and taxiways; runway lengthening, rehabilitation, and repair; and noise mitigation near airports. The Facilities and Equipment (F&E) account provides funding for the acquisition and maintenance of air traffic facilities and equipment, and for engineering, development, testing, and evaluation of technologies related to the federal air traffic system. The Research, Engineering, and Development account finances research on improving aviation safety and operational efficiency and on reducing environmental impacts of aviation operations.

Proposed authorizations and appropriations for these accounts are shown in Table 2.

|

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

FY2021 |

FY2022 |

FY2023 |

|

|

Operations |

||||||

|

10,247 |

10,486 |

10,732 |

11,000 |

11,269 |

11,537 |

|

|

10,123 |

10,233 |

10,341 |

10,453 |

|||

|

P.L. 115-141 authorization |

10,026 |

|||||

|

P.L. 115-141 appropriations |

10,212 |

|||||

|

Airport Improvement Program |

||||||

|

3,350 |

3,350 |

3,350 |

3,350 |

3,350 |

3,350 |

|

|

Additional General Fund Authorization |

1,020 |

1,041 |

1,064 |

1,087 |

1,110 |

|

|

3,350 |

3,750 |

3,750 |

3,750 |

|||

|

P.L. 115-141 authorization |

3,350 |

|||||

|

P.L. 115-141 appropriations |

4,350 |

|||||

|

Facilities and Equipment |

||||||

|

3,330 |

3,398 |

3,469 |

3,547 |

3,624 |

3,701 |

|

|

2,877 |

2,899 |

2,906 |

2,921 |

|||

|

P.L. 115-141 authorization |

2,855 |

|||||

|

P.L. 115-141 appropriations |

3,250 |

|||||

|

Research, Engineering, and Development |

||||||

|

181 |

186 |

190 |

195 |

200 |

204 |

|

|

175 |

175 |

175 |

175 |

|||

|

P.L. 115-141 authorization |

176 |

|||||

|

P.L. 115-141 appropriations |

189 |

|||||

|

TOTALS |

||||||

|

17,108 |

18,440 |

18,782 |

19,156 |

19,530 |

19,902 |

|

|

16,525 |

17,057 |

17,172 |

17,299 |

|||

|

P.L. 115-141 authorization |

16,407 |

|||||

|

P.L. 115-141 appropriations |

18,001 |

|||||

Sources: CRS analysis of P.L. 115-141, H.R. 4, and S. 1405.

Note: The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), appropriated $4.35 billion to the Airport Improvement Program in FY2018. This amount included a $1 billion general fund appropriation to discretionary grants for small airports.

Airport Financing7

The federal government supports the development of airport infrastructure in three different ways: (1) AIP grants to airports, mainly for capital projects related to aircraft operations; (2) authorization for individual airports to assess a local passenger facility charge (PFC) on each boarding passenger; and (3) preferential income tax treatment on interest income from bonds issued by state and local governments for airport improvements (subject to compliance with federal rules). Airports may also draw on state and local funds and on operating revenues such as lease payments and landing fees.

Different airports use different combinations of AIP funding, PFCs, tax-exempt bonds, state and local grants, and airport revenues to finance particular projects. Small airports are more likely to be dependent on AIP grants than large or medium-sized airports. Larger airports are much more likely to issue tax-exempt bonds or finance capital projects with the proceeds of PFCs. Each of these funding sources places various legislative, regulatory, or contractual constraints on airports that use it. The availability and conditions of one source of funding may also influence the availability and terms of other funding sources.

Airport Improvement Program (AIP)

The AIP provides federal grants to airports for airport development and planning. Participants range from very large publicly owned commercial airports to small general aviation airports that may be privately owned but are available for public use.8 AIP funding is usually limited to construction of improvements related to airside operations, such as runways and taxiways. Commercial revenue-producing facilities are generally not eligible for AIP funding, nor are operating costs.9 The structure of AIP funds distribution reflects congressional priorities and the objectives of assuring airport safety and security, increasing capacity, reducing congestion, helping fund noise and environmental mitigation, and financing small state and community airports.

The main financial advantage of the AIP to airports is that as a grant program, it can provide funds for capital projects without the financial burden of debt financing, although airports are required to provide a relatively modest local match to the federal funds. Limitations on the use of AIP grants include the range of projects that the AIP can fund and the requirement that recipients adhere to all program regulations and grant assurances.

Federal law requires the Secretary of Transportation to publish a national plan for the development of public-use airports in the United States. This appears as a biannual FAA publication called the National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS).10 For an airport to receive AIP funds, it must be listed in the NPIAS.

Funding Distribution

The distribution system for AIP grants is complex. It is based on a combination of formula grants (also referred to as apportionments or entitlements) and discretionary funds.11 Each year, the entitlements are first apportioned by formula to specific airports or types of airports. Once the entitlements are satisfied, the remaining funds are defined as discretionary funds. Airports apply for discretionary funds for projects in their airport master plans. Formula grants and discretionary funds are not mutually exclusive, in the sense that airports receiving formula funds may also apply for and receive discretionary funds. Grants are generally awarded directly to airports.

Distribution of AIP Grants by Airport Size

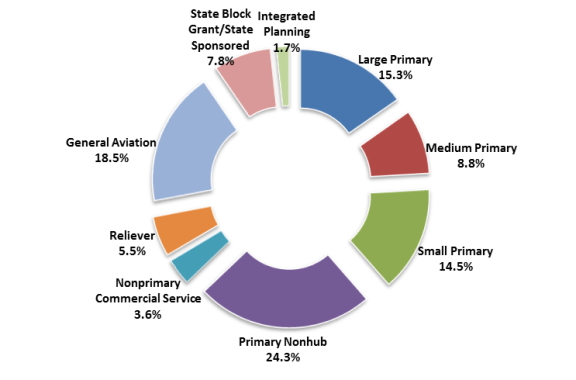

Although smaller airports' individual grants are of much smaller dollar amounts than the grants going to large and medium hub airports, the smaller airports are much more dependent on the AIP to meet their capital needs. This is particularly the case for noncommercial airports, which received about 24% of AIP grants distributed in FY2017. Figure 1 shows the share of AIP grants awarded in FY2017, by value, broken out by airport type.

|

|

Source: Data from FAA Airports Branch. |

The Federal Share of AIP Matching Funds

For AIP projects, the federal government share differs depending on the type of airport.12 The federal share is generally 75% for large and medium airports and 90% for other airports, with some exceptions. Certain economically distressed communities receiving subsidized air service may be eligible for up to a 95% federal share of project costs. This cost-share structure means that smaller airports pay a lower share of AIP-funded project costs than larger airports.13

The current AIP structure and funding mechanism generally tend to benefit airports smaller than medium hub size. H.R. 4 would strengthen this effect. It would create a new supplemental funding authorization for AIP discretionary funds from the general fund appropriations, starting in FY2019 with $1.02 billion and rising to $1.11 billion in FY2023. Large hub airports would not be eligible for these funds.

Passenger Facility Charges

The Aviation Safety and Capacity Expansion Act of 199014 allowed the Secretary of Transportation to authorize public agencies that control commercial airports to impose a passenger facility charge (PFC) on each paying passenger boarding an aircraft at their airports to supplement their AIP grants. The PFC is a state, local, or port authority fee and is not deposited into the Treasury.15

To impose a PFC above $3, an airport has to show that the funded projects will make significant improvements in air safety, increase competition, or reduce congestion or noise impacts on communities, and that these projects could not be fully funded by AIP funds. Unlike AIP grants that fund airside projects, PFC funds may be used to pay for a broader range of "capacity enhancing" projects, including for landside projects such as terminals and transit systems on airport property and for interest payments servicing debt incurred to carry out projects.16

Large and medium hub airports imposing PFCs above the $3 level forgo 75% of their AIP formula funds. Because of the complementary relationship between the AIP and PFCs, PFC provisions are generally folded into FAA reauthorization legislation dealing with the AIP. Initially, there was a $3 cap on each airport's PFC and a $12 limit on the total PFCs that a passenger could be charged per round trip. Legislation in 2000 raised the PFC ceiling to $4.50, with an $18 limit on the total PFCs that a passenger can be charged per round trip.

The central legislative issue related to PFCs is whether to raise or eliminate the $4.50 per enplaned passenger ceiling. In general, airports argue for increasing or eliminating the ceiling, whereas most air carriers and some passenger advocates oppose higher limits on PFCs. Neither the House-passed H.R. 4 nor the corresponding Senate bill, S. 1405, would change the current PFC ceiling.

The permissible uses of revenues are another ongoing point of contention. Airport operators, in particular, would like more freedom to use PFC funds for off-airport projects, such as transportation access projects, and want the process of obtaining FAA approval to be streamlined. Carriers, on the other hand, often complain that airports use PFC funds to finance proposals of dubious value, especially outside airport boundaries, instead of high-priority projects that offer meaningful safety or capacity enhancements. The major air carriers are also unhappy with their limited influence over project decisions, as airports are required only to consult with resident air carriers instead of having to get their agreement on PFC-funded projects. A provision in H.R. 4 would expand permissible uses of PFC revenues to include projects to prevent airport power outages. There is no similar provision in S. 1405.

Airport Privatization17

Almost all commercial service airports in the United States are owned by local and state governments, or by public entities such as airport authorities or multipurpose port authorities.18 In 1996, Congress established the Airport Privatization Pilot Program (APPP)19 to explore the prospect of privatizing publicly owned airports and using private capital to improve and develop them. In addition to reducing demand for government funds, privatization has been promoted as a way to make airports more efficient and financially viable.

Privatization refers to the shifting of governmental functions, responsibilities, and sometimes ownership, in whole or in part, to the private sector. With respect to airports, "privatization" can take many forms, up to and including the transfer of an entire airport to private operation and/or ownership. In the United States, most cases of airport privatization fall into the category of "partial privatization"; full privatization, either under or outside the APPP, has been rare.

The Interests at Stake

Airport privatization, especially in the case of long-term lease or sale, involves stakeholders with divergent interests. For example, airport owners, who are usually local governments, often are concerned about surrendering control of an economically important facility that may lead to the loss of public-sector jobs. Air carriers, on the other hand, would like to keep their costs low. They also want to have some control over how airport revenues are used, especially to ensure that the fees paid by themselves and their customers are used for airport-related purposes. Their interest in low landing fees and low rents for ticket counters and other facilities may be contrary to the interest of potential private operators in increasing revenue.

Private investors and operators expect a financial return on their investments. But if they attempt to increase profitability by raising landing fees or rents, that may bring them into conflict with air carriers using the airport.

The federal government, represented by FAA, has been directed by Congress to engage private capital in aviation infrastructure development and reduce reliance on federal grants and subsidies. However, FAA also has statutory mandates to maintain the safety and integrity of the national air transportation system and to enforce compliance with commitments, known as "grant assurances," that airports have made to obtain AIP grants. Thus FAA is likely to carefully examine privatization proposals that might risk closures of runways or airports or otherwise reduce aviation system capacity, or that appear to favor certain airport users over others.

The Airport Privatization Pilot Program (APPP)

Section 149 of the Federal Aviation Reauthorization Act of 1996 (49 U.S.C. §47134; P.L. 104-264) authorizes the FAA Administrator to exempt airports participating in the APPP from some or all of the requirements to use airport revenue for airport-related purposes, to repay federal grants, or to return airport property acquired with federal assistance upon the lease or sale of the airport deeded by the federal government.20 The law originally limited participation in the APPP to no more than five airports. The FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-95) increased the number of airports that may participate from five to 10. Only one large hub commercial airport may participate in the program, and that airport may only be leased, not sold. Only general aviation airports can be sold under the APPP.

Airport operators have generally not found privatization an attractive option. Since its inception, 11 airports have applied to enter the APPP; two airports, Stewart International Airport in upstate New York and Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in Puerto Rico, have completed the entire privatization process. However, Stewart International Airport later reverted to public ownership. There are three active applicants21 in the program. The others applied to privatize, but eventually chose not to proceed.

Language in H.R. 4 would allow more airports to enter the pilot program. Such a change, by itself, would not address the factors that have discouraged airports from entering the program. These include the requirement under the APPP that 65% of air carriers serving the airport22 approve a lease or sale of the airport; restrictions on increases in airport rates and charges that exceed the rate of increase of the Consumer Price Index (CPI); and a requirement that a private operator comply with grant assurances made by the previous public-sector operator to obtain AIP grants.23

An airport privatized under the APPP may use AIP formula grants to cover only 70% of the cost of improvements, versus the normal 75%-90% federal share at publicly owned airports. This serves as a disincentive to privatize an airport. In addition, publicly owned airports can make use of tax-exempt bonds, often secured by airport revenue. Such bonds offer less costly financing than is generally available to private entities.24

Privatization outside the framework of the APPP is generally unattractive to both airport owners and potential investors. Streamlining the APPP application and review process might make privatization somewhat more attractive by reducing the risks arising from a long application period, such as changes in economic and capital market conditions. However, significantly increasing interest in airport privatization is likely to require structural change to the existing airport financing system. Options might include offering the same tax treatment to private and public airport infrastructure bonds; changing AIP requirements; relaxing AIP grant assurances; liberalizing rules governing fees; and easing limits on the use of privatization revenue.

Next Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen) Implementation

NextGen refers to the Next Generation Air Transportation System, a large-scale modernization of air traffic technologies and procedures intended to expand national airspace system capacity to meet future demand. NextGen is a multiyear initiative to modernize and improve the efficiency of the national airspace system, primarily by migrating to technologies and procedures using satellite-based navigation and aircraft tracking. Initiated in legislation in 2003 (see P.L. 108-176), the NextGen system targets full-scale implementation by 2025.

Core components of the NextGen system include the following:

- Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B). A system for broadcasting and receiving aircraft identification, position, altitude, heading, and speed data derived from onboard navigation systems such as a GPS receiver. "ADS-B Out" functionality refers to a basic level of aircraft equipage that transmits position data. "ADS-B In" incorporates aircraft reception of ADS-B signals from other air traffic and/or uplinks of traffic, weather, and flight information from ground stations. FAA funds support the installation, operation, and maintenance of the ground network and associated infrastructure to receive ADS-B transmissions and relay them to air traffic facilities and other aircraft. Most aircraft will be required to have ADS-B Out capability by 2020.

- System Wide Information Management (SWIM). A system for aviation system data sharing, consisting of a seamless infrastructure for data exchange, similar to the internet. As envisioned, SWIM will consist of an extensive, scalable data network to share real-time operational information such as flight plans, flight trajectories, weather, airport conditions, and temporary airspace restrictions across the entire airspace system.

- Data Communications (DataComm). A digital voice and data network, similar to current wireless telephone capabilities, to transmit instructions, advisories, and other routine communications between aircraft and air traffic service providers.

- Collaborative Air Traffic Management Technologies (CATMT). A suite of technologies, including various automation and decision support tools, designed to enhance existing aircraft flow management functions by exploiting other NextGen technologies and capabilities such as SWIM.

- National Airspace System Voice System (NVS). Upgraded digital voice communications infrastructure that will replace existing analog equipment.

- NextGen Weather. An integrated platform for providing a common weather picture to air traffic controllers, air traffic managers, and system users.

Avionics Equipage

The network of ADS-B ground receiver stations in the contiguous 48 states has been deployed, and FAA has implemented performance-based navigation (PBN) procedures including departures, arrivals, and instrument approaches that improve airport access and operational efficiency. A large majority (more than 90%) of the air carrier fleet is equipped with PBN navigation equipment allowing utilization of NextGen procedures such as area navigation (RNAV). In contrast, only a small percentage of airliners and general aviation aircraft are equipped with ADS-B Out capability, a critical step to upgrading aircraft tracking capabilities.

In May 2010, FAA published a notice informing aircraft operators that most aircraft operating in controlled airspace would be required to equip with approved ADS-B Out equipment by 2020.25 As of May 2018, however, less than 20% of the airline and air taxi fleet is ADS-B equipped, even though most airlines have upgraded their aircraft with precision navigation capabilities. Moreover, only a small percentage of the general aviation fleet is equipped for either precision navigation or ADS-B tracking in the NextGen environment. FAA estimates that about 40,000 fixed-wing general aviation aircraft have installed compliant ADS-B units as of May 2018,26 but this also represents less than 25% of the total general aviation fleet.

H.R. 4 seeks to establish a pilot program to provide air traffic services on a preferential basis to aircraft equipped with upgraded NextGen avionics. S. 1405, on the other hand, would require FAA to identify any barriers to complying with the 2020 ADS-B mandate and develop a plan to address them. The Senate bill would also require FAA to develop a more effective international strategy to harmonize NextGen with comparable systems and achieve interoperability.

NextGen and Community Noise

Historically, Congress has addressed airport noise concerns by setting aside 35% of discretionary funding under AIP for noise mitigation and abatement. Generally, these funds may be used only within the Day Night Average Sound Level (DNL)27 65 decibel (dB) noise impact area around an airport. While new aircraft are significantly quieter than their predecessors, the increasing volume of air traffic around major airports and recent changes in flight patterns intended to exploit NextGen capabilities have, in some cases, increased noise in residential communities, triggering complaints.

A provision in P.L. 112-95 directed FAA to expedite the rollout of NextGen procedures and authorized FAA to streamline its environmental reviews of these changes. Around some airports, outcry from communities that had not previously experienced extensive overflights prompted Congress to revisit this approach, requiring FAA to more thoroughly examine potential community impacts of some of these actions and better engage local authorities and neighborhoods before implementing procedural changes to flight patterns (see P.L. 114-328, §341). H.R. 4 would direct FAA to consider additional actions, including fanning and dispersing flights to avoid high concentrations of noise over particular neighborhoods; using alternative noise metrics and criteria other than DNL to assess noise impacts; examine community involvement in NextGen planning at airports; and sponsoring research to assess the potential health impacts of aircraft noise. The bill would also direct FAA to implement a pilot program allowing older, noisier Stage 2 airplanes, which had been phased out of operations at all U.S. airports, to conduct limited operations to maintain or improve vital industries in small rural communities.

S. 1405 does not address community noise in the context of NextGen procedures, but does include language clarifying the use of AIP funds for certain noise mitigation programs and requirements for updating airport noise exposure maps. It would also require FAA to establish a federal noise standard for overland sonic booms from civil supersonic aircraft. H.R. 4 does not require FAA to develop a sonic boom standard, but broadly directs FAA to lead in the development of international policies, regulations, and standards for civil supersonic aircraft. Current FAA regulations generally do not permit civil supersonic flight, and there has not been a supersonic civil aircraft in operation since the Concorde was retired in 2003. However, there is growing interest in developing and marketing a civil supersonic aircraft for business jet fleets and high-end air charter operations.

Regulation of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS)

P.L. 112-95 required FAA to develop a plan for integrating unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), commonly referred to as drones, into the national airspace. It also established a test site program to study integration issues under operational conditions in airspace shared with manned flights. The 2012 act also required FAA to issue final rules covering civilian drones. Those rules allow commercial operations of small UAS weighing less than 55 pounds, provided they are operated within visual line of sight, remain below 400 feet, do not fly over people not involved in the operation, and maintain speeds under 100 miles per hour.28 Drone flights are allowed in the vicinity of airports and in other controlled areas only with prior permission of ATC. Operators must pass a written test to obtain an FAA remote pilot certification and must pass a security threat assessment conducted by the Transportation Security Administration. FAA does not certify the airworthiness of small commercial drones, but does require the remote pilot in command to conduct preflight checks to ensure that the vehicle is safe to fly.

While FAA may waive most of these regulatory restrictions on a case-by-case basis, routine drone operations beyond visual line-of-sight, over crowds, and in congested airspace are not yet permitted. This limits some potential applications, including drone delivery services, newsgathering in large urban areas, inspections of farm fields, and inspections of power lines, pipelines, and other linear infrastructure.

These limitations have been imposed largely in recognition that reliable technologies for remote identification, collision avoidance, and UAS traffic management in low-altitude airspace are still being developed and tested. S. 1405 would extend the existing UAS integration test site program for six years. It also seeks to facilitate testing of government-operated drones at the test sites, and to require study of beyond-visual-line-of-sight operations, sense-and-avoid technologies, and UAS traffic management concepts. H.R. 4 would extend the test site program for six years and would encourage the study of beyond-visual-line-of-sight operations and facilitate the testing of government-operated drones at the test sites.

Both bills would direct FAA to issue regulations within one year of enactment establishing a certification process for drone package delivery operations, including commercial fleet operations with highly automated UAS. The bills would also establish a collegiate training initiative program with a curriculum for UAS and would incorporate FAA positions related to UAS into its veterans employment programs.

The Senate bill would also direct FAA to use available remote detection and identification capabilities for safety oversight and enforcement and establish civil and criminal penalties for airspace violations and drone attacks against federal buildings. It would require FAA to establish a searchable public database of commercial and governmental UAS operators, including details regarding aircraft identification; the locations, times, and purposes of flights; and aircraft capabilities, including capabilities to collect personally identifiable information, including facial recognition. News organizations protected under the First Amendment would generally be exempted and excluded from the database. The Senate bill also contains language establishing an expectation that commercial drone operators establish written privacy policies consistent with an overarching U.S. policy that operations be conducted in a manner that respects and protects personal privacy afforded under the Constitution and applicable federal, state, and local laws. It also states that violations of privacy by commercial drones may be construed as unfair and deceptive trade practices enforceable by the Federal Trade Commission.

Aviation Safety Issues

FAA has responsibility for overseeing compliance with safety regulations at airlines, charter aircraft operators, repair stations, aircraft and aircraft parts design organizations and manufacturers, and other regulated entities. It maintains a safety workforce of more than 7,000 aviation safety workers including more than 4,000 field inspectors. Both H.R. 4 and S. 1405 would require FAA to review and revise its safety workforce training strategy to ensure that it aligns with FAA's risk-based approaches to safety oversight, seeks knowledge-sharing opportunities with industry, and includes appropriate milestones and metrics for meeting these objectives. H.R. 4 would additionally require the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to carry out an independent review and assessment of training needs at FAA's Office of Aviation Safety.

Maintenance of U.S. air carrier aircraft at both foreign and domestic locations is subject to regulation and oversight by FAA. Repair stations are regulated under 14 C.F.R. Part 145, and thus FAA-certificated repair stations are sometimes referred to as Part 145 repair stations. To be certified under Part 145, a repair station must develop FAA-approved documentation and processes including quality control procedures and training programs. FAA may also approve foreign repair stations based on a foreign certification issued by a country that has a bilateral aviation safety agreement with the United States.

FAA has adopted a compliance philosophy rooted in risk-based targeting of oversight activity that is informed by information voluntarily shared by regulated entities.29 The compliance philosophy, which guides FAA oversight of equipment design and manufacture, airline operations and maintenance, aircraft repair stations, general aviation, and other aspects of civil aviation, is in line with FAA's broad approach of encouraging workers in safety-sensitive jobs to freely report errors without fear of reprisal.30 With regard to airlines and airline maintenance repair stations, however, concerns have been raised that FAA has been too lenient in carrying out enforcement actions, particularly with respect to repair stations located outside the United States.31

H.R. 4 would require a GAO study of the effectiveness of FAA's new compliance philosophy, assessing whether it has resulted in greater reporting of safety incidents, whether reducing enforcement penalties has increased safety incidents, and whether FAA safety staff have complained that reduced enforcement has impacted regulatory compliance.

Additional concerns have been raised that FAA field offices do not consistently interpret regulations in carrying out their duties and providing oversight to regulated entities. FAA has sought to establish quality management systems to standardize processes across offices to minimize variations in the interpretation and application of regulations, including the establishment of a regulatory consistency committee. That committee identified three root causes of inconsistencies at FAA: unclear requirements, inadequate and nonstandard training, and a culture content with the status quo and reluctant to resolve inconsistencies. To date, there has been no independent assessment of the progress made or the effectiveness of revised certification practices. S. 1405 would require FAA to establish a centralized, publicly accessible database for all issued safety guidance and interpretations with appropriate links to specific regulations. The bill would also mandate that FAA establish a task force on reforming flight standards and maintain a regulatory consistency communication board to recommend processes for handling regulatory interpretation matters.

Aircraft and Parts Certification

FAA regulations and processes to oversee the safety certification of the design and manufacturing of aircraft and aircraft component parts are highly complex. P.L. 112-95 required FAA to streamline certification processes and address regional inconsistencies in the interpretation and application of certification regulations and processes. GAO found in 2014 that the FAA certification processes generally work well, but that FAA lacks performance measures to assess its progress on certification-related initiatives. GAO also found that interpretation of regulations is inconsistent at the regional level, potentially leading to inequitable treatment of industry competitors.32

H.R. 4 includes comprehensive reforms to FAA certification processes. It would direct FAA to create an industry advisory committee to provide policy advice regarding FAA safety certification, including certification processes, safety management systems and risk-based oversight, use of delegation and designation authorities, and regulatory interpretation standardization efforts. The bill would establish requirements for FAA to conduct routine oversight and inspections of organization designation authorization (ODA)33 holders, and maintain formal procedures for delegating them authority to monitor their own compliance. The bill proposes that FAA form an expert review panel to assess the ODA program and the timeliness and efficiency of the certification process. It also includes language to streamline the certification of safety-enhancing equipment and systems designed for small general aviation aircraft. It would also direct FAA to expand its practice of accepting airworthiness determinations made by regulator counterparts in foreign countries so long as bilateral safety agreements are in place and the foreign authority has an open and transparent process for issuing airworthiness directives.

S. 1405 would establish a specific ODA office within FAA to provide oversight and ensure consistency of FAA audit functions across the agency. The office would handle all requests from ODA holders regarding the review and removal of limitations and reviews of corrective actions taken. It would also require an expert panel review of FAA's ODA program.

Drug and Alcohol Testing and Substance Abuse Programs

The FAA extension act (P.L. 114-190) required FAA to establish a risk-based oversight system focusing on repair stations located outside the United States that perform heavy maintenance work on air carrier aircraft, and to target its oversight activities based on the frequency and severity of instances in which air carriers must take corrective actions following servicing at foreign facilities. The act also required FAA to issue a proposed rule regarding drug and alcohol testing at foreign repair stations within 90 days and to issue a final rule one year thereafter. FAA has not yet published the proposed rule, and DOT has indicated the rule may be further delayed in response to Executive Order 13771, which seeks to reduce federal regulations.34

Separately, H.R. 4 would put into statute a requirement that FAA implement a human intervention motivation study (HIMS) program for airline pilots. FAA has implemented HIMS, an occupational substance abuse treatment program, as a means for commercial pilots that have undergone successful rehabilitation for substance abuse to be granted special issuance medical certification allowing them to return to the cockpit with appropriate observation and monitoring by HIMS-trained aviation medical examiners. So far, HIMS has been developed for commercial pilots and has not been expanded to include mechanics or other FAA certificate holders.

Airline Pilot Training and Qualifications

The Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-216) required that FAA amend regulations to require that pilots attain the airline transportation pilot rating prior to being hired as airline first officers. Section 217 of the act required FAA to "conduct a rulemaking … to modify requirements for the issuance of an airline transport pilot certificate," and specified that "the total flight hours required by the Administrator … shall be at least 1,500 flight hours." Previously, pilots could be hired as airline first officers with a commercial pilot certification that required a minimum of 250 hours total flight time. On July 15, 2013, FAA required, effective August 1, 2013, that all pilots and first officers operating under 14 C.F.R. Part 121 (air carrier revenue operations) hold an airline transportation pilot certificate. It also required those serving as an air carrier pilot-in-command (captain) to have at least 1,000 flight hours in air carrier operations.35

S. 1405 includes a provision that would allow nonacademic structured and disciplined ground training courses to count toward the 1,500-hour requirement. Currently, only classroom hours at approved higher education institutions offering accredited aviation-related degree programs are allowed to be credited toward the requirements to obtain a restricted airline transportation pilot certificate, allowing them to be hired as first officers with fewer than 1,500 flight hours.

Pilot and Flight Attendant Fatigue

The Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-216) mandated changes to airline pilot flight time and rest requirements and the development of fatigue risk management plans. In response, FAA published a final rule on Flightcrew Member Duty and Rest Requirements on January 4, 2012.36 This added 14 C.F.R. Part 117, which prescribes passenger airline flight crew flight time, duty time, and rest requirements based on crew size, time of day, time and distance away from home base, and other factors. The regulation also requires airlines to implement a fatigue risk management system. The rules went into effect on January 14, 2014.

While these regulations are mandatory for passenger airlines, compliance is optional for all-cargo carriers that operate under 14 C.F.R. Part 121. Pilot labor organizations have long argued for uniform fatigue regulations under an umbrella "single level of safety" approach, although FAA and the airline industry maintain that air cargo operations are sufficiently different that separate regulatory requirements are appropriate. Efforts to include all-cargo pilots under the same set of duty and rest rules as passenger airline pilots did not pass in the 114th Congress (e.g., S. 1612), and similar efforts in the 115th Congress (e.g., S. 1423) have not been incorporated into either H.R. 4 or S. 1405.

Both H.R. 2997 and S. 1405, however, include language that would require FAA to revise existing flight attendant duty periods and rest requirements to ensure that flight attendants are provided a postduty rest period of at least 10 consecutive hours. While H.R. 2997 would not allow a rest period to be reduced under any circumstances, S. 1405 would permit a single rest period to be reduced to nine consecutive hours if it is followed by a rest period of 11 consecutive hours following the next duty period. Both bills would require airlines to develop FAA-approved fatigue risk management plans for flight attendants.

Age-Based Retirements for Certain Nonairline Pilots

In 2009, the United States raised the retirement age for airline pilots from 60 to 65 (See 14 C.F.R. 121.383(e) and 14 C.F.R. 61.3(j)). International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) standards also specify a maximum age of 64. For single-pilot international operations, the age limit remains at 60 years. Prior to 2014, international standards and FAA regulations required that pilots 60 years of age or older be paired with a pilot younger than 65. That restriction was lifted by both ICAO and FAA in November 2014.

For other operations, including charter flights and business aviation, there are no upper age restrictions for serving as a pilot so long as the individual can pass the applicable medical exam. However, a provision in H.R. 4 would set an upper age limit of 69 for pilots flying commuter and air taxi flights under 14 C.F.R. Part 135 and pilots of certain fractional-ownership jet fleets.

Global Aircraft Tracking and Flight Data Recorders

Two 2014 incidents renewed concern about the capabilities of tracking technologies and data recorders aboard passenger aircraft. The whereabouts of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, which disappeared in March 2014, remained uncertain as of May 2018, and the crash site of Indonesia AirAsia Flight 8501, which went down in the Java Sea on December 28, 2014, took several days to locate, despite the widespread availability of tracking technologies using GPS. While most transoceanic airliners are equipped with GPS, ATC continues to rely predominantly on ground-based radar to track aircraft. Tracking of aircraft based on GPS position is envisioned under FAA's NextGen initiative, but this system is to rely on a network of ground-based receivers within the United States, and, like the existing radar infrastructure, would be incapable of tracking aircraft beyond the coverage area of the network. Transoceanic flights, flights along polar routes, and flights passing over other remote areas journey beyond the range of ground-based radars and tracking stations. Enhanced satellite-based systems to track aircraft globally are being developed and deployed, and some U.S. military aircraft are equipped with deployable flight recorders that eject from the aircraft prior to impact, potentially facilitating the work of accident investigators. These options could aid in locating civilian aircraft in distress or involved in accidents in remote locations.

Both the House and Senate bills would instruct FAA to carry out an assessment and, as needed, implement new performance standards to improve aircraft tracking and flight data recovery through technologies such as automatic deployable flight recorders, triggered transmissions of flight data, distress-mode tracking, satellite-based solutions, and protections against disabling flight recorder systems.

Runway Safety

FAA has addressed surface movement safety though investments in airport lighting and signage improvements, modifications to procedures and communications, and investments in such technologies as surface radar, runway status lights, final approach runway occupancy signals, and tablet devices for pilots (known as electronic flight bags) with moving map capabilities. Additionally, FAA has supported targeted installation of special pavement materials, known as Engineered Materials Arresting Systems (EMAS), at airports where aircraft that overrun a runway could collide with structures or enter bodies of water.

P.L. 112-95 required FAA to develop a strategic runway safety plan that includes specific national goals and proposed actions to enhance runway safety, particularly at commercial service airports. The act also required FAA to develop a process for tracking and investigating runway incidents and deploy systems to alert air traffic controllers and pilots of potential runway incursions into the NextGen implementation. The plan, published in November 2012, indicated that FAA is using a number of data collection and analysis tools to identify and mitigate safety risks in airport surface movements and terminal area operations.37 FAA also committed to specific actions including the installation of runway status lights at 23 large airports and the installation of EMAS at additional airports that do not have standard runway safety areas to mitigate risks of runway overruns.

S. 1405 would require FAA to develop a plan assessing the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of direct warning technologies to alert flight crews and air traffic controllers of potential runway incursions. It would direct FAA to expedite its efforts to develop metrics for examining trends in runway incursions and assess the effectiveness of runway safety initiatives. The bill would also require FAA to prepare progress reports detailing projects using airports grants to make runway safety improvements.

Carriage of Lithium Batteries

Lithium batteries pose a risk of fire aboard aircraft, whether transported separately or installed in portable electronic devices. P.L. 112-95 prohibited DOT from imposing regulations regarding the carriage of lithium batteries in a manner more restrictive than those allowed under ICAO technical instructions.

Language in the House bill would give DOT more leeway regarding lithium battery carriage regulations. Specifically, H.R. 4 would require DOT to carry out cooperative efforts to ensure that lithium battery shipments comply with U.S. hazardous materials regulations and ICAO technical instructions. It would also direct DOT to establish a lithium battery air safety advisory committee that would provide advice and recommendations regarding lithium battery safety and mechanisms for increasing awareness of relevant requirements among shippers and air passengers. The committee would also be charged with advising DOT in preparation for ICAO meetings regarding the safety of lithium batteries.

Helicopter Fuel System Safety

Helicopter crashes involving air ambulances in Texas, Missouri, and Colorado in 2015 and a February 2018 air tour helicopter crash in Arizona stand out among aviation accidents that have raised safety concerns about the design of helicopter fuel systems. The accidents have prompted the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) to issue recommendations to FAA that it update regulations and guidelines regarding helicopter fuel system crashworthiness.38

H.R. 4 would require all newly built helicopters to conform to fuel system crashworthiness standards specified in FAA regulations. Currently, newly built helicopters that are constructed to meet type design specifications that were approved before an October 1994 regulatory change do not need to conform to the updated fuel system crash resistance standards.

FAA Organizational Issues

Air Traffic Control (ATC) Reforms

The organization of air traffic services has been a major focus of FAA reauthorization debate over the past three years. FAA reauthorization measures considered favorably by the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee during the 114th Congress (H.R. 4441) and the 115th Congress (H.R. 2997) both included detailed provisions to establish a not-for profit private corporation to provide the air traffic services currently delivered by FAA. In contrast, bills introduced in the Senate (S. 2658, 114th Congress, and S. 1405) have not included any ATC reforms.

On January 27, 2018, Representative Bill Shuster, chairman of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, announced that he would no longer insist on restructuring of FAA ATC operations,39 and on April 13, 2018, introduced H.R. 4, which did not include ATC privatization language. An alternative plan to move ATC out of FAA but retain it under DOT was briefly considered in an amendment to H.R. 4, but that idea was scrapped, and the House-passed version of the bill did not include any ATC reforms.

The privatization proposals stumbled on two main obstacles. One was funding. The proposals envisioned that the ATC entity would be a self-sustaining organization that would cover its costs with fees charged on aircraft using the system. User fees have been strongly opposed by general aviation interests, and Congress has repeatedly refused to permit them. The other obstacle has been the proposed organization's borrowing costs. Although the ability to borrow in the financial markets to modernize the air traffic system is often cited as an advantage of an independent entity, such an entity would face higher borrowing costs than the federal government, unless the federal government's full faith and credit were to back the entity's debt obligations. However, as proposed, the air traffic entity and its debts would have been completely separate from the federal government.

Despite the lack of support for separating ATC from FAA, FAA has taken modest steps over the years toward privatizing certain functions. ATC operations at 253 airports without radar control are provided by private operators under the Federal Contract Tower program. Since 2006, FAA has contracted out the work performed at automated flight service station facilities that provide preflight and in-flight weather briefings and flight planning services, mostly to general aviation operators. FAA also has made increased use of design-build-maintain contracts that make contractors, rather than FAA personnel, responsible for installing and maintaining ATC equipment.40

Controller Workforce Initiatives

Historically, FAA has advertised job openings for air traffic controllers to specific categories of applicants, using separate evaluation processes for each category. In February 2014, it switched to a single, nationwide vacancy announcement with a uniform evaluation process that was open to all qualified U.S. citizens between the ages of 18 and 30. FAA also changed its process for selecting among eligible candidates in response to recommendations from two reports undertaken to examine barriers to workplace diversity in the ATC hiring process.

These changes were substantial. Under the process used for hiring pursuant to the February 2014 vacancy announcement, a biographical assessment was utilized as a first step to assess applicants' experience and aptitude for ATC. FAA asserted that the biographical assessment effectively addressed workforce diversity concerns while identifying those applicants most likely to succeed in training and as fully certified air traffic controllers. Moreover, FAA claimed that the revised selection process reduced costs by more than $7 million. However, the new hiring and selection process raised concerns among the 36 colleges and universities that have developed curricula tailored to careers in ATC under an FAA program known as the Air Traffic Collegiate Training Initiative (AT-CTI).

P.L. 114-190 limited FAA's ability to continue the hiring process used for the February 2014 vacancy announcement. It mandated that FAA give preferential consideration to air traffic controller applicants with prior experience at an FAA, FAA-contracted, or military air traffic facility and further stipulated that, after giving preference to experienced controllers, FAA select in roughly equal numbers from two separate applicant pools of (1) AT-CTI graduates, and (2) all U.S. citizens applying in response to a general recruitment announcement. The act also banned FAA from using biographical assessments to evaluate applicants who are experienced controllers or AT-CTI graduates. It also required FAA to reevaluate any experienced controllers or AT-CTI graduates who were disqualified based on the results of a biographical assessment after applying in response to the February 2014 announcement, even if they were older than the maximum age of 30 years. For applicants with one or more years of prior ATC experience, the law increases the maximum entry age to 35 years.

Facilities Consolidation

Consolidation of FAA air traffic facilities and functions is viewed as a means to control operational costs, replace outdated facilities, and improve air traffic services. Consolidation efforts to date have primarily focused on terminal radar approach control (TRACON) facilities. TRACON consolidation has been ongoing for many years, but in the past has been limited to nearby or overlapping terminal areas in major metropolitan areas such as New York/Northern New Jersey, Washington/Baltimore, and Los Angeles/San Diego. More recently, FAA has sought to decouple combined airport tower/approach control facilities and merge approach control functions across larger geographical areas.

FAA plans are politically sensitive, as consolidation initiatives could result in job losses in specific congressional districts even if they do not result in an overall decrease in jobs for air traffic controllers, systems specialists, and other supporting personnel. Rather, realignment and consolidation coupled with airspace modernization under the NextGen system are anticipated to change the nature of these job functions and consolidate them in fewer physical facilities.

Provisions in the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-95) required FAA to provide a comprehensive list of its proposed recommendations for realignment and consolidation of services and facilities for public comment and congressional review. FAA convened a collaborative working group, which has issued three reports describing various recommendations for realignment and consolidation of specific ATC facilities. The reports describe consolidation options in parts of New England, Texas, and Oklahoma, portions of western Pennsylvania and New York, in northern Ohio and southern and central Michigan, and in Illinois and Missouri and eastern Washington state.41 FAA's future course of action regarding these recommendations as well as future facility consolidation plans remains uncertain. In 2017, GAO reported42 that FAA initiatives envisioning a reduced number of air traffic facilities and reaping additional benefits from NextGen have been deferred until after 2020 due to fiscal constraints, noting that FAA has refocused efforts in this area on replacing the aging New York TRACON with a new facility.

H.R. 4 would amend the existing statutory language regarding FAA facilities realignment consolidation to emphasize that the purpose of the recommendations is to reduce the overall number of ATC facilities and to incorporate input from industry stakeholders and labor organizations into the recommendations process. The bill would also prohibit FAA from realigning or consolidating any facilities where military operations comprised 40% or more of the total annual TRACON activity in calendar year 2015.

Facilities Security, Cybersecurity, and Resiliency

On September 26, 2014, an act of arson at FAA's Chicago ATC center temporarily shut down air traffic into Chicago's two commercial airports and disrupted flights across much of the country. The incident highlighted the potential physical security risks posed by contractors and employees with access to facilities. It also illustrated the importance of redundancy, as controllers working at other locations, not in the Chicago area, were able to return the system to normal operation within a couple of days. In 2015, GAO raised specific concerns over how well FAA is addressing security and cybersecurity as it transitions to the NextGen system and as modern aircraft become increasingly connected to the internet.43 It recommended that FAA assess developing a cybersecurity threat model and take steps to develop a coordinated, holistic, agency-wide approach to cybersecurity. In 2017 the DOT Office of Inspector General found FAA's response to and preparedness for major system disruptions, including the fire at the Chicago center, to be inadequate due to a lack of training, redundancy, resiliency, and flexibility.44 It recommended that FAA take steps to improve contingency planning and testing of emergency safeguards, and to assess the role of NextGen capabilities in enhancing resiliency and continuity of operations and mitigating future ATC disruptions.

P.L. 114-190 requires FAA to oversee the development of a framework of principles and policies to address aviation cybersecurity. The framework is to address airspace modernization, aircraft automation, and aircraft systems, including inflight entertainment systems. The act also requires FAA to address recommendations from the 2015 GAO report and develop and maintain an agency-wide cybersecurity threat model, and establish a cybersecurity standards plan for FAA information systems, and an aviation cybersecurity research and development plan.

H.R. 4 would require FAA to initiate a review of the framework developed in response to the P.L. 114-190 mandate. The House bill would also require FAA to identify safety risks associated with power outages at airports and recommend actions to improve the resilience of communication, navigation, and air traffic surveillance systems in the event of such an outage. FAA would also be required to review existing mechanisms to alert pilots and air traffic controllers in the event of a failure or problem with runway lighting and provide recommendations to enhance situational awareness of such events.

S. 1405 would require FAA to update its ATC operational contingency plans every five years to address potential air traffic facility outages that could have major impacts on the operation of the national airspace system and to incorporate resiliency, continuity of operations, and mitigation of ATC disruptions into planned NextGen capabilities. S. 1405 would also direct FAA to consider revising aircraft certification requirements to address the cybersecurity and accessibility of avionics.

Oversight of Commercial Space Activities

Significant global competition exists in the rapidly growing commercial space industry, with Russia, France, and increasingly China vying for commercial space launch business. FAA's regulates and licenses commercial space launch providers and is also charged with promoting private-sector space launches. This parallels FAA's former dual role as a safety regulator and an industry promoter of the commercial aviation industry; concern about the potential conflicts this created led to a provision in the FAA Reauthorization Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-264) that directed FAA to focus on safety and transferred its promotional role to DOT. GAO has noted that FAA's dual mandate with regard to commercial space activity may pose a potential conflict of interest.45

FAA's authority encompasses launch and reentry of space vehicles, but does not extend to orbital activities and operations. Currently, there are 10 licensed launch sites in the United States. Since 1989, FAA has licensed 286 commercial space launches and issued permits for 44 launches, including 18 licensed launches and 1 permitted launch in FY2017 and 19 licensed launches so far in FY2018. FAA has also licensed 16 reentries since 2010, including 3 in FY2017 and 2 so far in FY2018.

H.R. 4 would establish a designated Office of Spaceports within FAA's Office of Commercial Space Transportation to provide technical assistance, promote infrastructure improvements, and support licensing activities for launch sites. It would also require a GAO study of spaceport activities, detailing funding options including user funding options and matching infrastructure grants. S. 1405 did not include similar language, but includes language that would require aeronautical studies to evaluate any proposed construction of structures that might interfere with launch or reentry sites as is currently required for areas around airports.

FAA Research and Development

FAA Research and Development focuses on aviation system safety, efficiency, and the reduction of environmental impacts. Historically, about half of FAA research funding has addressed efficiency and economic competitiveness, largely supporting modernization efforts like NextGen. About 37% of funding has gone toward research addressing safety issues, and the remainder has funded projects addressing energy and environmental impacts.

FAA receives advice and recommendations regarding its research program from industry through the Research, Engineering, and Development Advisory Committee (REDAC), which assesses research needs in five major areas: operations, airport technology, aviation safety, human factors, and environment and energy. Pursuant to 49 U.S.C. §44501(c), FAA is required to develop an annual national aviation research plan that is to be submitted to congressional oversight committees prior to the submission of the President's budget to Congress. The plan lays out the five-year research and development goals and anticipated funding requirements.

A 2017 GAO review of FAA strategic planning for research and development recommended that FAA improve its processes for identifying long-term research priorities, improve transparency regarding how projects are selected and funded, and ensure that annual reviews and plans meet applicable statutory requirements regarding content.46 FAA indicated that it is revising its approach to research planning but has not issued an updated national Aviation Research Plan since 2016.

In addition to specific Research, Engineering, and Development amounts, FAA research activities are funded by FAA's other major accounts. About 47% of FAA research is funded through the Facilities and Equipment (F&E) account, including that related to advanced technology development and prototyping and NextGen system development, and another 11% is derived from AIP funds. H.R. 4 calls for direct funding of $186 million in FY2019, increasing to $204 million in FY2023, and S. 1405 specifies $175 million annually through FY2021 for FAA research, engineering, and development. However, the FY2019 budget request proposes to reduce direct FAA research, engineering, and development funding by roughly $100 million to $74 million. While some additional research funding may come from other FAA accounts beyond what has been provided in years past, this may have a considerable impact on FAA grants and research partnerships with industry and academia as well as FAA staffing in research positions.

Essential Air Service (EAS)47

The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-504) gave airlines almost total freedom to determine which domestic markets to serve and what airfares to charge. This raised the concern that communities with relatively low passenger levels would lose service as carriers shifted their operations to serve larger and often more profitable markets. Congress established the EAS program to help ensure a continuation of service to those small communities that were served by certificated air carriers before deregulation, with subsidies if necessary. The EAS program is administered by the Office of the Secretary of Transportation, which determines the minimum level of service required at each eligible community by specifying

- a hub through which the community is linked to the national network;

- a minimum number of round trips and available seats that must be provided to that hub;

- certain characteristics of the aircraft to be used; and

- the maximum permissible number of intermediate stops to the hub.

Over the years, Congress has limited the scope of the program, mostly by eliminating subsidy support for communities within a reasonable driving distance of a major hub airport. The FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 adopted additional EAS reform measures, including Section 421, which amended the definition of an "EAS eligible place"48 to require a minimum number of daily enplanements. The FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016 and the subsequent extensions did not make significant changes to the EAS program.

Under the 2012 act, for locations to remain EAS-eligible, they must have participated in the EAS program at any time between September 30, 2010, and September 30, 2011. An EAS-eligible place is now defined as a community that, during this period, either received EAS for which compensation was paid under the EAS program or received from the incumbent carrier a 90-day notice of intent to terminate EAS following which DOT required it to continue providing service to the community (known as "holding in" the carrier). Since October 1, 2012, no new communities may enter the program should they lose their unsubsidized service, except for locations in Alaska or Hawaii.

Communities eligible for EAS in FY2011 remain eligible for EAS subsidies if49

- they are located more than 70 miles from the nearest large or medium hub airport;

- they require a rate of subsidy per passenger of $200 or less, unless the community is more than 210 miles from the nearest hub airport;

- the average rate of subsidy per passenger is less than $1,000 during the most recent fiscal year at the end of each EAS contract, regardless of the distance from hub airport; and

- they have an average of 10 or more enplanements per service day during the most recent fiscal year beginning after September 30, 2012, unless these locations are more than 175 driving miles from the nearest medium or large hub airport, or unless DOT is satisfied that any decline below 10 enplanements is temporary.