The Rohingya Crises in Bangladesh and Burma

A series of interrelated humanitarian crises, stemming from more than 600,000 ethnic Rohingya who have fled Burma into neighboring Bangladesh in less than 10 weeks, pose challenges for the Trump Administration and Congress on how best to respond.

The flight of refugees came following attacks on security outposts in Burma’s Rakhine State, reportedly by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), an armed organization claiming it is defending the rights of the region’s predominately Muslim Rohingya minority, and an allegedly excessive military response by Burma’s military. Some of the displaced Rohingya report that Burmese soldiers systematically killed civilians, sexually assaulted women and girls, and burned down their homes. The Burmese government and military have denied the veracity of these reports. An unknown number of Rohingya, Rakhine, and other ethnic minorities have been forced out of their villages into temporary camps within Rakhine State, while others remain isolated in their home villages under a government-imposed curfew.

In Bangladesh, an estimated 700,000-900,000 Rohingya—including people who fled Burma during earlier instances of violence—require urgent humanitarian assistance. In Burma, tens of thousands are in need of humanitarian assistance, but the Burmese government and military have restricted access to the affected areas. Efforts to facilitate the voluntary and safe return of the displaced Rohingya and other ethnic minorities to their original villages face several problems. Bangladesh and Burma have been unable to agree to terms for repatriation. Many of the villages have been destroyed, raising questions about when the people can return and where they will go. It is also uncertain how many of the displaced Rohingya are willing to return to Burma, given the nation’s history of discriminatory policies and practices, including a 1982 law that effectively stripped them of their citizenship.

The crises raise questions about U.S. policy toward Burma, following its transition to a civilian/military government after six decades of military rule. The day before the August 2017 attacks, a special commission established by Burma’s de facto leader, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, and headed by former U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan, made a series of recommendations on how to end ethnic tensions in Rakhine State, including calling for the repeal of the anti-Rohingya laws and regulations. While Aung San Suu Kyi accepted most of those recommendations, it is unclear how soon and to what extent they will be implemented.

The human rights allegations have led some observers to say the Burmese military is guilty of crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing, and genocide. The Burmese government and others assert that ARSA is a terrorist organization. The United Nations Human Rights Council has created a special, fact-finding mission to investigate human rights violations in Burma, but the Burmese government and military have dismissed the allegations of widespread human rights violations and have refused to allow the fact-finding mission into Burma.

The displaced Rohingya in Bangladesh may also pose a serious radicalization risk. Some Rohingya may be recruited by ARSA or Islamist extremist groups. Some Rakhine may choose to join the Arakan Army, a Rakhine-based ethnic armed organization involved in active resistance against the Burmese government.

The Trump Administration and the State Department have adopted a measured approach to the emerging challenges presented by the crises in Bangladesh and Burma. The initial response was to increase humanitarian assistance to both nations by a total of $32 million, raising the amount of assistance provided since October 2016 to $95 million. New restrictions on relations with senior Burmese military officers have been imposed using existing authority.

Two bills have been introduced in the 115th Congress since the August attacks and the Burmese military’s “clearance operations”—the Burma Unified through Rigorous Military Accountability Act of 2017 (BURMA Act; H.R. 4223) and the Burma Human Rights and Freedom Act of 2017 (S. 2060). Both bills would impose a visa ban on senior military officers responsible for human rights abuses in Burma, place new restrictions on security assistance and military cooperation, reinstate jadeite and ruby import bans, and require U.S opposition to international financial institution loans to Burma if the project involves an enterprise owned or directly or indirectly controlled by the military. S. 2060 also would provide an additional $104 million in humanitarian assistance, and would require the President to review Burma’s eligibility for the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) program.

This report will be updated as circumstances require.

The Rohingya Crises in Bangladesh and Burma

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Precipitating Events

- Background on Rakhine State and the Rohingya

- Scope of the Humanitarian Crises in Burma and Bangladesh

- The Humanitarian Situation in Rakhine State

- The Humanitarian Situation in Bangladesh

- Bangladesh's Response

- The International and U.S. Humanitarian Response

- U.N. and Other Appeals

- U.S. Humanitarian Assistance to Burma

- The Repatriation/Resettlement Crisis

- Burma's Discriminatory Laws and Policies

- Allegations of Human Rights Violations

- Burma's Response

- Addressing the Alleged Human Rights Abuses

- Risk of Radicalization in Rakhine State and Bangladesh

- Regional Dynamics

- Overview of U.S.-Burma Policy

- The Trump Administration's Response

- U.S. Sanctions Policy and Restrictions

- U.S. Relations with the Burmese Military

- Issues for Congress

Summary

A series of interrelated humanitarian crises, stemming from more than 600,000 ethnic Rohingya who have fled Burma into neighboring Bangladesh in less than 10 weeks, pose challenges for the Trump Administration and Congress on how best to respond.

The flight of refugees came following attacks on security outposts in Burma's Rakhine State, reportedly by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), an armed organization claiming it is defending the rights of the region's predominately Muslim Rohingya minority, and an allegedly excessive military response by Burma's military. Some of the displaced Rohingya report that Burmese soldiers systematically killed civilians, sexually assaulted women and girls, and burned down their homes. The Burmese government and military have denied the veracity of these reports. An unknown number of Rohingya, Rakhine, and other ethnic minorities have been forced out of their villages into temporary camps within Rakhine State, while others remain isolated in their home villages under a government-imposed curfew.

In Bangladesh, an estimated 700,000-900,000 Rohingya—including people who fled Burma during earlier instances of violence—require urgent humanitarian assistance. In Burma, tens of thousands are in need of humanitarian assistance, but the Burmese government and military have restricted access to the affected areas. Efforts to facilitate the voluntary and safe return of the displaced Rohingya and other ethnic minorities to their original villages face several problems. Bangladesh and Burma have been unable to agree to terms for repatriation. Many of the villages have been destroyed, raising questions about when the people can return and where they will go. It is also uncertain how many of the displaced Rohingya are willing to return to Burma, given the nation's history of discriminatory policies and practices, including a 1982 law that effectively stripped them of their citizenship.

The crises raise questions about U.S. policy toward Burma, following its transition to a civilian/military government after six decades of military rule. The day before the August 2017 attacks, a special commission established by Burma's de facto leader, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, and headed by former U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan, made a series of recommendations on how to end ethnic tensions in Rakhine State, including calling for the repeal of the anti-Rohingya laws and regulations. While Aung San Suu Kyi accepted most of those recommendations, it is unclear how soon and to what extent they will be implemented.

The human rights allegations have led some observers to say the Burmese military is guilty of crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing, and genocide. The Burmese government and others assert that ARSA is a terrorist organization. The United Nations Human Rights Council has created a special, fact-finding mission to investigate human rights violations in Burma, but the Burmese government and military have dismissed the allegations of widespread human rights violations and have refused to allow the fact-finding mission into Burma.

The displaced Rohingya in Bangladesh may also pose a serious radicalization risk. Some Rohingya may be recruited by ARSA or Islamist extremist groups. Some Rakhine may choose to join the Arakan Army, a Rakhine-based ethnic armed organization involved in active resistance against the Burmese government.

The Trump Administration and the State Department have adopted a measured approach to the emerging challenges presented by the crises in Bangladesh and Burma. The initial response was to increase humanitarian assistance to both nations by a total of $32 million, raising the amount of assistance provided since October 2016 to $95 million. New restrictions on relations with senior Burmese military officers have been imposed using existing authority.

Two bills have been introduced in the 115th Congress since the August attacks and the Burmese military's "clearance operations"—the Burma Unified through Rigorous Military Accountability Act of 2017 (BURMA Act; H.R. 4223) and the Burma Human Rights and Freedom Act of 2017 (S. 2060). Both bills would impose a visa ban on senior military officers responsible for human rights abuses in Burma, place new restrictions on security assistance and military cooperation, reinstate jadeite and ruby import bans, and require U.S opposition to international financial institution loans to Burma if the project involves an enterprise owned or directly or indirectly controlled by the military. S. 2060 also would provide an additional $104 million in humanitarian assistance, and would require the President to review Burma's eligibility for the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) program.

This report will be updated as circumstances require.

Introduction

The Rohingya—a predominately Sunni Muslim minority of northern Rakhine State in Burma (Myanmar)—are facing several concurrent crises precipitated by the reported attack on August 25, 2017, on Burmese security facilities near the border with Bangladesh. The attacks, allegedly conducted by a relatively new and little known Rohingya nationalist group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), and an ensuing "clearance operation" conducted by Burma's security forces have resulted in the rapid displacement of more than 600,000 Rohingya into makeshift camps in eastern Bangladesh, and the internal displacement of an unknown number of people within Rakhine State. These events have created two immediate humanitarian crises in Bangladesh and in Rakhine State.

In addition, long-standing policies and attitudes in Burma regarding the Rohingya are creating major challenges to the possibility of their voluntary return. Starting in the 1960s under Burma's military juntas and continuing until today under a mixed civilian/military government, Burma's laws and policies have deprived most of the Rohingya of many of their human rights, including their citizenship. According to some observers, it is likely that many of the displaced Rohingya will not wish to return to Burma unless their safety can be secured, the discriminatory laws and policies are changed, and their human rights restored. If conditions in Burma are not suitable for repatriation, the international community may need to consider other assistance for the Rohingya, including longer-term accommodation in camps in Bangladesh and exploring local integration and resettlement options.

|

Role of the Burmese Military in Burma's Government Under Burma's 2008 constitution, which was largely written by members of Burma's military, also known as the Tatmadaw, Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing has ultimate authority over all security forces in the country, including the military, the Border Guard Force, and the Myanmar Police Force. The security forces are constitutionally responsible for the protection of Burma from all threats internal and external. The 2008 constitution also provides that the Commander-in-Chief has "final and conclusive" authority over the adjudication of military justice. In addition, the 2008 constitution grants the Commander-in-Chief the authority to appoint 25% of the members of both chambers of the Union Parliament, as well as the Ministers of Border Affairs, Defense, and Home Affairs. The Minister of Home Affairs has authority over the General Administration Department, which oversees the work of Burma's civil servants at all levels of government. Because of these powers, and others provided by the 2008 constitution, some experts maintain that the Commander-in-Chief is the most powerful political figure in Burma. In addition, the 2008 constitution limits the ability of the civilian side of the government to control or oversee the activities of Burma's security forces. |

Allegations of organized, systematic, and severe human rights abuses by Burmese security personnel, ARSA and its supporters, and local Rakhine "vigilantes" have given rise to claims of possible crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing, or genocide taking place in Rakhine State. Beyond ensuring that such violence stops, the allegations of human rights abuse present Burma and the rest of the world, including the United States, with the challenge of adequately investigating and documenting the possible human rights abuses, and if necessary, establishing suitable measures for accountability of those found responsible. The ongoing violence in Rakhine State reportedly is another factor contributing to the reluctance of many Rohingya to return to Burma.

The displacement of the Rohingya, combined with the alleged violence of the Burmese security force's clearance operation, has also created an environment that could give rise to the radicalization of portions of both the Rohingya and predominately Buddhist Rakhine population.1 Some Rohingya may join the ranks of ARSA or become supporters of other more militant extremist organizations. Islamist militant groups, in particular, may attempt to recruit Rohingya. In addition, some Rakhine may enlist with the extant Rakhine-based ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or form local militias to defend themselves from the perceived ARSA threat.

The Trump Administration has responded to the crises by making gradual and limited changes to U.S. policy. The initial response from the State Department was to denounce the alleged ARSA attacks, and call upon the Burmese government and military to exercise restraint in responding to the attacks. As the number of displaced persons increased, the Trump Administration provided additional funding for humanitarian assistance, but refrained from commenting on the allegations of serious human rights abuses. More recently, the State Department announced new restrictions on relations with the Burmese military, but indicated that its focus was on solving problems, not punishing people.

Congress may choose to consider what actions, if any, the United States should take in response to these various crises and challenges. Among the issues the Rohingya crises raise are the following:

- Humanitarian Policies and Issues: How much humanitarian assistance is needed in Bangladesh and in Rakhine State, and for how long? What role should the United States play in providing that assistance? How should international assistance be coordinated?

- Repatriation/Resettlement Issues: What are the prospects for safe and voluntary repatriation of the displaced Rohingya? What arrangements should be made for the resettlement of those who do not wish to return to Burma, and what role should the United States play in such a resettlement program?

- Issues of Discrimination in Burma: How important is rectifying Burma's discriminatory laws and policies for the voluntary repatriation of the Rohingya and reconciliation between the Rakhine and Rohingya? What measures should the United States take to encourage or pressure the Burmese government to repeal or amend discriminatory laws and policies?

- Human Rights Abuse Issues: What efforts should be made to investigate and document the alleged human rights abuses, and what role should the United States play in supporting or conducting such efforts? What are the options for securing accountability for those people or organizations determined to be responsible for human rights abuses?

- Issues Regarding the Risk of Radicalization: How serious is the risk of radicalization of Rakhine or Rohingya, or their recruitment by existing EAOs or Islamist militant groups? What measures, if any, should the United States take to assist the Bangladesh government and the Burmese government to counteract efforts to radicalize members of either ethnic community? Does the treatment of the Rohingya minority pose a radicalization risk for communities elsewhere in the region?

- Issues Related to Potential Destabilization of the Region: Will the displaced Rohingya in Bangladesh raise domestic political tensions related to Islamist agendas for Bangladesh? Will this have an impact on Bangladesh domestic politics and Bangladesh-Burma relations?

- Issues for U.S. Policy Toward Burma: Do the events in Rakhine State warrant a rethink or adjustment in current U.S. policy toward Burma? Should some of the previously waived U.S. sanctions on Burma be reinstated to encourage or promote changes in the policies and behavior of the Burmese government or the Burmese military? What forms of assistance should the United States provide to the Bangladesh government and the Burmese government to respond to the various crises coming out of the events in Rakhine State? How will the issue affect U.S. geopolitical interests, given China's substantial influence in Burma?

On November 2, 2017, companion bills were introduced in the House of Representatives and the Senate that offer an approach to addressing the Rohingya crises, as well as a reformulation of U.S. policy toward Burma. The Burma Unified through Rigorous Military Accountability Act of 2017 (BURMA Act; H.R. 4223) and the Burma Human Rights and Freedom Act of 2017 (S. 2060) would impose sanctions on selected Burmese military leaders, limit security and military assistance, and place conditions on multilateral assistance until the Burmese government and military meet certain criteria to address the various crises in Rakhine State. The Burma Human Rights and Freedom Act of 2017 would also appropriate $104 million for humanitarian assistance to "the victims of the Burmese military's ethnic cleansing campaign targeting Rohingya in Rakhine State."

Precipitating Events

On August 25, 2017, ARSA members and local Rohingya supporters reportedly attacked 30 security facilities, including border outposts and one military base, killing over a dozen Burmese security personnel. The Burmese military, or Tatmadaw, almost immediately began a "clearance operation," deploying more than 70 battalions, or an estimated 30,000-35,000 soldiers, into Rakhine State. According to State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, the clearance operation ended on September 5, 2017. The "clearance operation" in the townships of Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung in northern Rakhine State was a major factor leading to the displacement of more than 600,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh, as well as the internal displacement of an unknown number of Rakhine, Rohingya, Hindu, Magyi, Mro, and Thet in Rakhine State.2

The current crisis in Rakhine State can be traced further back to October 10, 2016, when ARSA allegedly attacked three border outposts, killing nine police officers. The Tatmadaw responded by initiating a similar "clearance operation" that resulted in approximately 87,000 Rohingya crossing into Bangladesh, and the internal displacement of an unknown number of Rohingya into temporary camps.

Background on Rakhine State and the Rohingya

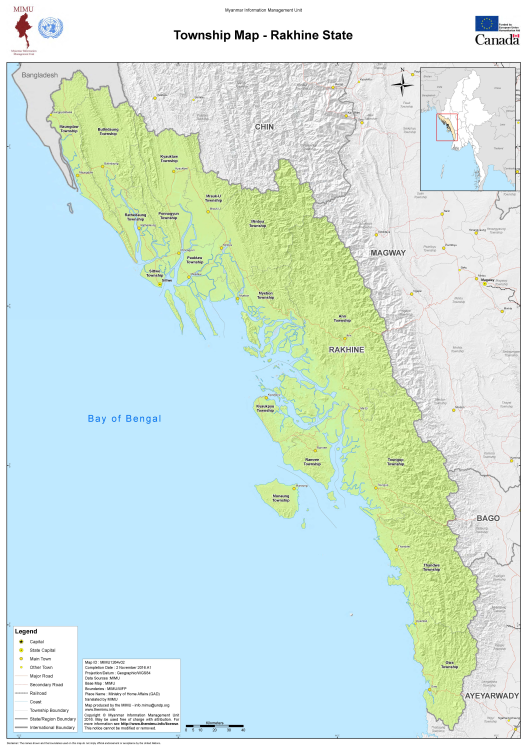

Rakhine State (also known as Arakan State) is located in western Burma, east of the Bay of Bengal and on the border with Bangladesh. The state is 14,200 square miles in size (slightly larger than the State of Maryland), with an estimated population (pre-crises) of 3.2 million.

|

|

Source: Myanmar Information Management Unit. |

The largest ethnic group in Rakhine State is the Rakhine (or Arakan), a predominately Theravada Buddhist community. The next largest ethnic group is the Rohingya, a predominately Sunni Muslim community. Other ethnic groups living in Rakhine State include Bamar, Chin, Daingnet, Hindu, Kamar (also Sunni Muslims), Magyi, Mro, and Thet. Various sources estimate the pre-crises Rohingya population of Rakhine State at 1.0 million-1.1 million; the ethnic Rakhine population is thought to be about 2 million. Most of the Rohingya live in the northern Rakhine townships of Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung; the Rakhine are the majority population in central and southern Rakhine State.

According to the Rohingya, their ancestors have lived in what is now northern Rakhine State since at least the 9th century. Prior to the military coup of 1962, the Rohingya were Burmese citizens, and were elected to Burma's parliament, served in the government, and were officers in the military. After the coup, Burma's military leaders began a systematic policy of discrimination against the Rohingya, and carried out military campaigns to drive the Rohingya out of Burma.3 For example, in 1978, under General Ne Win, the Burmese military swept across northern Rakhine State as part of Operation Dragon King, pushing an estimated 200,000-250,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh. In 1982, Burma's military junta promulgated the Citizenship Law that effectively stripped the Rohingya of their citizenship. The 1982 Citizenship Law remains in effect.

The Burmese military, the government led by Aung San Suu Kyi, as well as a majority of Burma's population—including the Rakhine—maintain that most of the Rohingya are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, and should therefore be identified as "Bengali." According to this narrative, the influx of "Bengalis" into Burma began during the period of British rule, when Burma was part of the British Raj, and continued after Burma's independence in 1948, as "Bengalis" freely moved across the porous border with then-East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.

Relations in Rakhine State between the Rakhine majority and the Rohingya minority have vacillated between periods of relatively peaceful coexistence and times of violent confrontation. Predominately Rakhine and Rohingya villages often exist in close proximity, with regular social and economic interaction. Interethnic violence typically arises, however, when members of one ethnic group allegedly mistreat members of the other ethnic group. Such an event precipitated the outbreak of interethnic violence in June to October 2012 that resulted in dozens of deaths, approximately 200,000 Rohingya fleeing to Bangladesh, and another 120,000 Rohingya becoming internally displaced persons (IDPs) living in camps in Rakhine State.

Scope of the Humanitarian Crises in Burma and Bangladesh

UNHCR and other humanitarian organizations report that 94% of the more than 600,000 displaced people in Bangladesh are Rohingya, with a smaller number of ethnic Hindu and Rakhine known to be among them. An estimated 54% of the displaced are children and 4% are elderly. The remaining 42% are adult refugees, roughly 52% of whom are women.4 Concerns have been raised about the status and whereabouts of "missing men" (mostly men of military age) who are reportedly not among those fleeing the country. As of early November 2017, the estimated range of the total number of displaced (mostly Rohingya) in Bangladesh (including from this crisis and from previous waves of displacement during the past five years) is estimated at between 700,000 to just over 900,000.5 U.N. Secretary General António Guterres stated, "The situation has spiraled into the world's fastest-developing refugee emergency and a humanitarian and human rights nightmare."6

|

Background: Humanitarian Situation in Burma Prior to August 25, 2017 Prior to the exodus that began on August 25, 2017, serious humanitarian issues existed in many parts of Burma as a result of decades of communal and ethnic divisions, structural inequalities, and protracted conflict. Millions of Burma's estimated 51.5 million people suffered from food insecurity, chronic poverty, and lack of adequate health and other services. In addition, an estimated 6.4 million people lived in conflict-affected areas. Emanating from this fragile situation were regional refugee, migration, and labor issues, including thousands of refugees in Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, and Thailand. Burma is also one of the Asian nations most vulnerable to natural disasters. In December 2016, the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) identified 525,000 people who were in need of critical humanitarian and protection assistance, mainly as a result of conflict. These included 218,000 people who were Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in camps and host communities in Kachin (87,000), Shan (11,000), and Rakhine (120,000); and 307,000 nondisplaced, vulnerable people with a lack of access to services. In addition, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that nearly 1 million people (mostly Rohingya in Rakhine) were stateless. With the October 2016 attacks, an increased number of Rohingya became IDPs or fled to Bangladesh. Humanitarian organizations faced severe constraints on access due to limitations imposed by the government in northern Rakhine and Kachin/northern Shan. Bangladesh already hosted 33,000 registered (mostly Rohingya) refugees in two camps as well as an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 others, the vast majority of whom were undocumented and not registered as refugees. Sources: UNOCHA, 2017 Myanmar Humanitarian Response Plan: January-December 2017, December 5, 2016. |

Precise figures on the overall number of people displaced—either within Burma's Rakhine State or across the border in Bangladesh—are not available because the situation remains fluid, and access to affected areas of northern Rakhine State is limited. While the pace at which newly displaced persons are entering Bangladesh varies, experts say that at one time up to 20,000 people attempted to cross the border each day.7 Their ability to enter Bangladesh is reportedly being hampered by Burmese security forces building fencing and allegedly placing landmines along the border.8 Lack of transport and cost also limit people's ability to cross the border. Bangladesh has so far kept its borders open. Neither Bangladesh nor Burma are States Parties to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees or its 1967 Protocol.

The Humanitarian Situation in Rakhine State

Little is known about the number of IDPs and the conditions under which they are living within Rakhine State, because Burmese security forces have restricted media access and most humanitarian assistance to that area. Tens of thousands are estimated to have been displaced internally. Many of those who have fled their homes and villages are reportedly being hosted by relatives and friends. Some are living in schools or monasteries, while others are thought to be on the border with Bangladesh or hiding in forests. According to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), an estimated 27,000 IDPs who are ethnic Daingnet, Hindus, Mro, and Rakhine have relocated from northern to southern Rakhine State since August 25, 2017. Some humanitarian organizations are concerned that those Rohingya who remain in Burma may eventually be forced to flee due to a lack of medical care, food, and other basic needs.

On October 2, 2017, the Burmese government gave 20 diplomats, several U.N. officials, and local media a guided tour of parts of northern Rakhine State. U.N. Under-Secretary-General for Political Affairs Jeffrey Feltman visited Burma from October 13-17 at the invitation of the Burmese government. Most of the discussions reportedly focused on the situation in Rakhine State and the plight of those displaced since August 25, with an emphasis on unhindered humanitarian access to northern Rakhine State and voluntary and safe returns.9 Separately, the Burmese government has escorted international and local reporters into the three affected townships.

|

The Plight of the Rohingya Muslim Population Of the vulnerable populations identified by UNOCHA, in Rakhine State, the 120,000 long-term IDPs—mostly Rohingya displaced as a result of prior outbreaks of ethnic violence—live in 36 camp or camp-like settings. An additional 282,000 people in 11 townships were also in need of humanitarian support. At the end of 2016, 402,000 people in Rakhine State were considered in need of humanitarian and protection assistance. Rakhine State is less developed than most of Burma. It has the highest poverty rates and fares poorly on nutrition and other development indicators. For the Rohingya, restrictions on freedom of movement impact many areas of their lives and create dependence on humanitarian and protection assistance while being continually marginalized in their own country. In addition to limited freedom of movement, key protection concerns include physical insecurity, gender-based violence, a lack of personal identification documents (rendering many Rohingya Muslims as stateless), and human trafficking. |

The Burmese government has stated that the humanitarian response is being led by the government under the responsibility of the Minister for Social Welfare and will continue to draw on the support of the Red Cross Movement—which includes the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), and the Myanmar Red Cross Society (MRCS)—to provide humanitarian assistance in Rakhine State. Various national Red Cross societies from other countries are also providing support as the Red Cross Movement scales up its response. Access to northern Rakhine is blocked to all other agencies, and most humanitarian activities across central Rakhine remain suspended or severely interrupted. International aid groups continue to urge the Burmese government to provide unfettered access to Rakhine State. Efforts to move supplies from the capital city of Sittwe to the affected area reportedly have been hampered by Rakhine protesters who oppose the provision of assistance to Rohingya.

The Humanitarian Situation in Bangladesh

Bangladesh is a poor, majority-Muslim country with over 160 million people in a nation approximately the size of Iowa. As such, its capacity to accommodate the approximately 600,000 newly displaced Rohingya is limited. It is reported that Border Guard Bangladesh sources estimated in early November 2017 that a further 50,000 Rohingya had gathered on the border seeking entry into Bangladesh.10

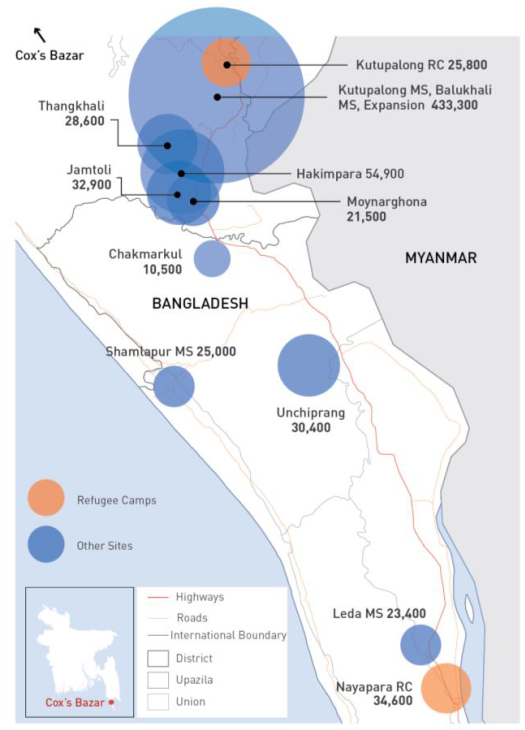

The situation has created enormous humanitarian needs in an area of Bangladesh already affected by earlier refugee influxes since the 1990s, recent floods, and a lack of capacity to cope with a large number of new arrivals. The two existing refugee camps near the city of Cox's Bazar are overflowing with more than double the previous population of 33,000, and well beyond capacity. With the assistance of UNHCR, Bangladesh has reportedly started biometric registration of Rohingya at camps near Cox's Bazar.

While new arrivals initially moved into established sites and host communities, due to limited space and severe overcrowding, they have been establishing new, spontaneous settlements. Many of the recently displaced Rohingya are living in the open. Humanitarian partners are continuing to deliver basic assistance, but there are significant gaps and a critical need to scale up health, water, and sanitation interventions due to the risk of disease outbreaks in densely populated areas in addition to basic food assistance, shelter, and protection. Respiratory infections, dysentery, and other ailments are reportedly spreading among the Rohingya in Bangladesh, and there is a great need for clean drinking water, food, and sanitation.11

Bangladesh is establishing a new 3,000-acre camp at Kutupalong that is to reportedly accommodate 800,000 people in a single, enormous camp.12 (This new camp is in addition to the two existing official camps near Cox's Bazar mentioned previously.) The Ministry of Disaster and Relief Management is to coordinate with humanitarian partners to install basic facilities. Besides the new "mega camp" at Kutupalong, Bangladesh has also considered a plan to relocate Rohingya to an island in the Bay of Bengal.13 The island, Thengar Char, which has been previously suggested by the Bangladesh government in this context, is located near Jaliyar Char (also known as Bhashan Char), where work has reportedly begun to accommodate Rohingya. It is reported that parts of the Thengar Char flood at high tide.14

Bangladesh's Response

An estimated 8-10 million Bangladeshis fled to India in 1971 in the wake of atrocities committed by the West Pakistan army and local sympathizers in East Pakistan during Bangladesh's struggle for independence from Pakistan. Hundreds of thousands of Bengalis died during this conflict. This experience informs many Bangladeshis' perspective on the plight of the Rohingya.

Bangladesh Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Mohammed Shahriar Alam has stated that the Rohingya issue is a security issue, as well as a humanitarian one, and that Bangladesh would take prompt action if ARSA tries to enter Bangladesh. It is Bangladesh's policy not to allow ARSA to establish a base in Bangladesh:

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina articulated a five point policy for the Rohingya in a speech to the United Nations in September 2017. Prime Minister Hasina proposed the following.... that Myanmar unconditionally, immediately and forever stop violence and ethnic cleansing in Rakhine State; that the Secretary-General immediately send a fact-finding mission to Myanmar; and that all civilians, irrespective of religion and ethnicity, be protected in Myanmar, including through the creation of United Nations-supervised safe zones. She also proposed the sustainable return of all forcibly displaced Rohingya in Bangladesh to their homes in Myanmar, and the immediate, unconditional and full implementation of the recommendations of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State.15

Foreign Secretary M. Shahidul Haque has stated that Bangladesh considers the Rohingya to be "forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals" and not migrants, illegals, or refugees. Bangladesh has called on Burma to repatriate the displaced Rohingya and on international organizations to assist Bangladesh in caring for the Rohingya until they can return to Burma.16

Foreign Minister A.H. Mahmood Ali stated that Bangladesh would not agree to Burma's proposal to use the 1992 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the two nations as the basis for returning Rohingya to Burma because the situation has changed. The 1992 MoU is based on the Rohingya's ability to "establish their bona fide residency in Myanmar."17 Bangladesh favors United Nations involvement to assist in discussions on Rohingya repatriation to Burma.18

While Bangladesh has received international praise for its support for the displaced Rohingya, there are some indications that it is nearing its limit, including the following:

- Bangladesh's Border Guard has indicated that Bangladesh is planning on fencing the border with Burma.19

- Bangladesh has reportedly barred three NGO organizations, Muslim Aid Bangladesh, Islamic Relief, and the Allama Fazlullah Foundation, from providing assistance to the Rohingya.20

- Bangladesh's Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) has reportedly set up a base camp at Teknaf to monitor the Rohingya to prevent them from becoming militants.21

- Prime Minister Hasina called on the 63rd Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference to pressure Burma to stop the persecution of its Rohingya people.22

The International and U.S. Humanitarian Response

In addition to national and local capacity in Bangladesh, U.N. entities and numerous international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) have been providing critical humanitarian protection and assistance to those fleeing Burma. Response efforts are having an impact through the provision of food assistance, water, sanitation and hygiene support, health care, and shelter kits. Vaccination campaigns are underway against measles and rubella, polio, and cholera. Overcrowding is a critical problem. Addressing protection concerns, including the risks of human trafficking, is part of the humanitarian response.

Prior to August 25, 2017, the Burmese government and military reportedly limited many national and international humanitarian efforts to provide assistance and protection to IDPs and others affected by conflict, including those in Rakhine State. Most international representatives did not have access to affected areas beyond the main towns. Where access was granted, Burmese staff have often been restricted. Since August 25, 2017, as previously mentioned, access in northern Rakhine State has been suspended for most humanitarian organizations, except the Red Cross Movement.

U.N. and Other Appeals

In December 2016, the United Nations, along with humanitarian partners, launched Myanmar's 2017 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) for $150 million, in response to the displacements caused by the October 2016 attacks and the subsequent "clearance operation" conducted by the Burmese military. In addition, the U.N. Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), which provides rapid, initial funding in protracted crises, provided Burma with a total of $104 million between 2006 and 2016. The Myanmar Humanitarian Fund, a multidonor fund that enables organizations to access flexible funding to address gaps in the humanitarian response, also provided funds.

These funding appeals have now changed. In September 2017, UNOCHA and its partners released a preliminary response plan requesting $77 million in funding for the situation unfolding in Burma and Bangladesh. The Joint Response Plan has since been revised upwards to $434 million and aims to assist 1.2 million people, including Rohingya refugees and host communities, between September 2017 and February 2018. As of October 16, 2017, $106 million (24%) had been committed or disbursed in support of the appeal. A further $19 million has been allocated from CERF. Individual U.N. agencies and other international organizations are also launching separate appeals. A pledging conference organized by UNOCHA, UNHCR, and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and cohosted by the European Union and Kuwait took place on October 23, 2017, and raised $360 million as part of an effort to share in the cost of the response.

U.S. Humanitarian Assistance to Burma

In recent years, U.S. humanitarian policy in Burma has been guided by concerns about access and protection within Burma, as well as with Burmese refugees and asylum seekers in the region and more broadly in Southeast Asia. On November 15, 2016, U.S. Ambassador Scot Marciel reissued a disaster declaration for Burma after the October attacks on security posts and the subsequent "clearance operation." In FY2016, the United States allocated more than $50 million to help meet humanitarian needs in Burma using global humanitarian accounts to fund implementing partners.

On September 20, 2017, the State Department announced that it would provide an additional $32 million in humanitarian assistance for the displaced people in Bangladesh and northern Rakhine State, with approximately $28 million allocated to assistance in Bangladesh and $4 million for Rakhine State. According to the State Department, this is in addition to $63 million in humanitarian assistance provided since October 2016 "for vulnerable communities displaced in and from Burma throughout the region."23 Trump Administration policy on humanitarian assistance to Burma is not known and the amount of humanitarian assistance to be provided in FY2018 has not been determined.

The key U.S. agencies and offices providing humanitarian assistance to Burma include the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) and Food for Peace (FFP) and the State Department's Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM).

The Repatriation/Resettlement Crisis

Although accurate figures are not available, it is estimated that between 700,000 to just over 900,000 displaced (mostly Rohingya) are currently in camps in Bangladesh. Thousands of Rohingya are displaced in other nations in South and Southeast Asia, including India, Malaysia, and Thailand. Potentially more than 1 million Rohingya may wish to return to northern Rakhine State, depending on the conditions set for their return, as well as the likely situation they would face once they do so. If conditions are not acceptable and/or inadequate measures are taken for the security of the returnees, then it is possible that many of the displaced Rohingya would not voluntarily return to Burma, and other provisions would need to be made.

Aung San Suu Kyi has indicated that her government would like the repatriation to be managed in accordance with a 1992 agreement between Bangladesh and Burma negotiated following a previous case of mass displacement. As previously stated, Bangladesh does not accept this proposal, and has called for the United Nations to be involved in resolving the conditions of return to Burma.

The 1992 agreement stipulated that Burma would accept the return of anyone who could provide evidence of their prior residence in Burma. One Burmese official has stated that this may mean proof of eligibility for Burmese citizenship, which would significantly reduce the number of Rohingya who would be permitted to return to Burma.24 It is unlikely that many of the displaced Rohingya possess documents to establish their prior residence in Burma given the circumstances under which they fled to Bangladesh.

Burma's Discriminatory Laws and Policies

The Burmese government—whether under past military rule or under the current mixed civilian-military government—enforces a number of discriminatory policies specifically toward the Rohingya. Among these policies are the following:

- Denial of Citizenship—The 1982 Citizenship Law effectively revoked the citizenship of most of the Rohingya in Burma. Prior to August 2017, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that nearly 1 million people (mostly Rohingya in Rakhine) were stateless.

- Denial of Suffrage and Representation—In 2015, then-President Thein Sein invalidated the temporary identification cards ("white cards") possessed by many Rohingya that had permitted them to vote in past elections. As a result, the Union Election Commission did not allow the Rohingya to vote in the 2015 parliamentary elections, and prohibited Rohingya political parties and candidates from participating in the elections.

- Denial of Education and Employment—Because they are not citizens, most Rohingyas cannot attend public universities, work for the government, or join the military or the Myanmar Police Force.

- Restrictions on Movement—Rohingya in rural areas are prohibited from moving out of their home villages without the permission of local authorities.

- Restrictions on Marriage, Religious Conversion, and Procreation—In 2015, Burma's Union Parliament passed four "Race and Religion Protection Laws" that seemingly targeted Burma's Muslim population and, in particular, the Rohingya. The laws banned cohabitation with someone who is not one's spouse (to ban de facto polygamy), prohibited interfaith marriages and conversion to Islam within a marriage without government approval, and required that women living in certain regions—regions with a high percentage of Muslim households—space pregnancies at least 36 months apart.

Aung San Suu Kyi responded to the October 2016 attacks and the ensuing unrest by forming an international commission, the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, headed by former U.N. General Secretary Kofi Annan, to "identify the factors that have resulted in violence, displacement, and underdevelopment" in Rakhine State.25 On August 24, 2017, the commission released its final report, cautioning that "a highly militarized response is unlikely to bring peace to the area."26 Among the commission's recommendations are to promote greater economic development in Rakhine State, to align Burma's 1982 Citizenship Law with international standards and enable the Rohingya to obtain citizenship, and to make arrangements for the resettlement of IDPs.

Aung San Suu Kyi has said that the Burmese government is willing to abide by most of the commission's recommendations, and on October 9, 2017, appointed a committee tasked to implement the recommendations of the Advisory Commission, as well as those of the Maungdaw Regional Investigation Commission.27 The new implementation committee consists entirely of government officials, and while it includes at least one Rakhine member, it has no Rohingya representative.

Allegations of Human Rights Violations

The United Nations, the local and international media, human rights organizations, and international humanitarian organizations have accused Burma's security forces of serious human rights abuses that may constitute ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity, or possibly genocide during both "clearance operations" conducted following the October 2016 and August 2017 attacks on security installations. U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein told the U.N. Human Rights Council the following on September 11, 2017:

We have received multiple reports and satellite imagery of security forces and local militia burning Rohingya villages, and consistent accounts of extrajudicial killings, including shooting fleeing civilians.

Last year I warned that the pattern of gross violations of the human rights of the Rohingya suggested a widespread or systematic attack against the community, possibly amounting to crimes against humanity, if so established by a court of law. Because Myanmar has refused access to human rights investigators the current situation cannot yet be fully assessed, but the situation seems a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.28

The Tatmadaw has denied the allegations; the Burmese government and the Tatmadaw assert that ARSA is responsible for any human rights violations that may have occurred in Rakhine State.

Many of the Rohingya and others who have arrived in Bangladesh following the two "clearance operations" claim that Tatmadaw soldiers entered their villages, and proceeded to kill civilians, rape women and girls, and then burn down the entire village. International medical teams treating the Rohingya in these camps report that some people bear gunshot wounds consistent with being shot from behind, and some women and girls have injuries consistent with sexual assault. One BBC reporter who obtained access to the area witnessed the looting and destruction of a Rohingya village by what appeared to be a group of Rakhine men. The Tatmadaw soldiers escorting the reporter reportedly made no effort to interrogate or detain those involved.29

Utilizing satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch and other organizations have documented the destruction of nearly 300 villages and thousands of houses and businesses in northern Rakhine State. According to its assessment of satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch claims that at least 288 villages in northern Rakhine State have been partially or totally destroyed by fire since August 25, 2017. Some of the images show that Rohingya structures have been burned, but neighboring Rakhine buildings are unharmed. In addition, reports say at least 66 villages have been damaged after September 5, 2017, the day the second "clearance operation" supposedly stopped.30

Burma's Response

Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing has denied these allegations. In a meeting with U.S. Ambassador to Burma Scot Marciel on October 12, 2017, he said that "unlawful acts [by Burmese security forces] are not allowed," and that "no action goes beyond the legal framework."31 He also reportedly told Ambassador Marciel that the international media was intentionally exaggerating the number of Rohingya who have fled to Bangladesh. Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, however, has agreed to establish a military investigatory team to examine the allegations of human rights abuses by security personnel. A similar Burmese military investigation conducted after the "clearance operation" following the October 2016 attacks reportedly found no evidence of systemic human rights abuses by Burmese security forces.

Senior Burmese government officials have also denied the human rights abuse allegations. Vice President Henry Van Thio stated the following before the U.N. General Assembly on September 20, 2017:

The security forces have been instructed to adhere strictly to the Code of Conduct in carrying out security operations, to exercise all due restraint, and to take full measures to avoid collateral damage and the harming of innocent civilians. Human rights violations and all other acts that impair stability and harmony and undermine the rule of law will be addressed in accordance with strict norms of justice.32

Addressing the U.N. Security Council on September 28, 2017, Burma's National Security Advisor Thaung Tun said, "There is no ethnic cleansing and no genocide in Myanmar."33 Thaung Tun continued, stating, "I can assure you that the leaders of Myanmar, who have been struggling so long for freedom and human rights, will never espouse policy of genocide or ethnic cleansing and that the government will do everything to prevent it."

The Tatmadaw and the Burmese government claim that ARSA and its supporters have committed serious human rights violations. During his meeting with Ambassador Marciel, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing implied that ARSA and its supporters may have been responsible for alleged human rights violations, stating, "Local Bengalis were involved in the attacks under the leadership of ARSA. That is why they might have fled as they feel insecure."34 The Burmese government also says that ARSA killed over 50 civilians in Rakhine State prior to the attacks on August 25, 2017, because ARSA claimed they were informants for the Tatmadaw. According to Aung San Suu Kyi, it was principally because of these alleged killing of civilians that her government declared ARSA a terrorist organization on August 28, 2017.

Official Burmese government and military descriptions have been selective in providing information about the Tatmadaw's "clearance operation" or allegations of human rights abuse. For example, the government-run newspaper, Global New Light of Myanmar, has run several detailed articles about the alleged mass killings of Hindus in one village by ARSA, but has provided little coverage of the reported destruction of Rohingya villages. Evidence has surfaced that questions the accuracy of the Global New Light of Myanmar account of the alleged Hindu mass killings, as some of the women quoted in the article had previously stated the Burmese military, not ARSA, had killed the Hindu villagers.35

Addressing the Alleged Human Rights Abuses

Various military operations in northern Rakhine State over the last 40 years have consistently been followed by the displacement of thousands of Rohingyas, and usually have involved allegations of serious human rights violations of Rohingya by Tatmadaw soldiers. In general, the Tatmadaw speak of and seemingly consider the Rohingya as inferior to the Bamar majority, and by extension, seem to tolerate discrimination and maltreatment of Rohingya. Some Tatmadaw officers have defended their soldiers accused of raping Rohingya women by stating that Rohingya women are too "dirty" and "ugly" for their soldiers to even consider rape.36

One lingering question is the goal or objective of the Tatmadaw's recent treatment of the Rohingya. As previously stated, U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein has concluded the Tatmadaw's activities constitute "ethnic cleansing" of Rohingya. Others maintain the objective is to reduce the percentage of Rohingya in northern Rakhine State by forced displacement plus the immigration of Bamar, Rakhine, and other ethnic minorities into the region. There is some past evidence of the Burmese government's desire to see the removal of all Rohingya from Burma. In July 2012, then-President Thein Sein said that the Burmese government was prepared to hand over the Rohingyas to the UNHCR so they could be resettled in any countries "that are willing to take them."37 The United Nations rejected President Thein Sein's offer.

|

The Tatmadaw's Alleged Pattern of Human Rights Abuse: "Four Cuts" Strategy The situation in Rakhine States is neither the first time nor the only place that credible allegations have been made that the Burmese security forces have committed organized, systematic, and severe human rights abuses. Allegations of the Tatmadaw committing human rights abuses against the Rohingya date back to Operation Dragon King in 1978. Various Burmese NGOs have released reports documenting cases of Burmese security personnel killing civilians, raping women and girls, and burning down villages in the States of Kachin, Karen, Mon, and Shan.38 This reoccurring pattern of human rights abuse is frequently viewed as being part of the Tatmadaw's "four cuts" strategy to undermine support for the ethnic armed organizations. The "four cuts" are cutting off food, funds, intelligence, and popular support. By targeting civilians, the Tatmadaw allegedly believes it will reduce local support for the EAOs. However, in some cases, the abuse has reportedly led to greater support for the EAOs. It is reported that in Rakhine State, the displacement of the Rohingya is aimed at depriving ARSA of recruits, supporters, food, and funding. |

In March 2017, the U.N. Human Rights Council approved a fact-finding mission to investigate alleged human rights violations in Rakhine State, but Aung San Suu Kyi has so far refused to permit the mission entry into Burma, stating that their presence "would have created greater hostility between the different communities." On August 31, 2017, U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights Situation in Myanmar Yanghee Lee stated, in reference to the situation in Rakhine State, "The humanitarian situation is deteriorating rapidly and I am concerned that many thousands of people are increasingly at risk of grave violations of their human rights."39 On September 19, 2017, the United Nations reiterated its request for its fact-finding mission to be granted access to Rakhine State. Under the auspices of the U.N. Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR), on September 26, 2017, seven U.N. experts, or Special Rapporteurs, together called on the Government of Myanmar to stop all violence against the minority Muslim Rohingya community and halt the ongoing persecution and serious human rights violations.40

Other international actors have taken steps to address the human rights issues. The U.N. Security Council released a presidential statement on November 6, 2017, that, among other things, expressed

grave concern over reports of human rights violations and abuses in Rakhine State, including by the Myanmar security forces, in particular against persons belonging to the Rohingya community, including those involving the systematic use of force and intimidation, killing men, women, and children, sexual violence, and including the destruction and burning of homes and property.41

The statement also called on the Burmese government to "swiftly and in full" implement the recommendations of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, and "cooperate with all relevant United Nations bodies," including the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

The World Bank has postponed a $200 million loan to Burma, stating that it was "deeply concerned about the violence, destruction and forced displacement of the Rohingya," and would withhold the loan until conditions in Rakhine State had improved.42 The United Kingdom has suspended all its defense cooperation and training programs with Burma's security forces until the violence against the Rohingya has ceased.43 On October 12, 2017, the European Union said it would halt all ties to Burma's senior military leaders, and is considering additional measures if the situation in Rakhine State does not improve.44

Risk of Radicalization in Rakhine State and Bangladesh

The displacement of more than 600,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh, the internal displacement of presumably thousands of Rakhine and other ethnic groups within Rakhine State, and the alleged violence associated with those displacements has created a potentially fertile environment for the radicalization of previously apolitical populations. There is speculation that some of the disgruntled and abused Rohingya may choose to support ARSA or more militant Islamic or nationalist organizations.45 Displaced Rakhine may look to groups such as the Arakan Army, a Rakhine-based ethnic armed organization reportedly active in southern Chin State and northern Rakhine State, to defend them from ARSA. This could open a new front in Burma's long-standing low-grade civil war, and have an impact on the ongoing efforts to negotiate an end to the conflict.46

There is much uncertainty related to ARSA and the extent to which it has outside support. ARSA has denied its alleged ties to international terrorist groups and portrays itself as an ethno-nationalist group seeking to defend its own people. Despite this, some observers view ARSA as a militant group with ties to international terrorists. Others emphasize that the recent attacks against the Rohingya have created a situation that may present opportunities for recruitment of Rohingya by international terrorist organizations even if ARSA itself has no ties to such groups.

|

Arakan Army and the Arakan Liberation Army: Rakhine EAOs While most observers have focused on the newly arisen Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), Rakhine State has given birth to two other ethnic-based armed organizations, the Arakan Army (AA) and the Arakan Liberation Army (ALA). Both EAOs are ethnically Rakhine. The Arakan Army was founded in 2009 and has past ties with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Ta'ang National Liberation Army (TNLA). In 2015, AA soldiers fought with Border Guards Bangladesh and Tatmadaw forces. Some observers claim that Tatmadaw soldiers were moved into northern Rakhine State in August 2017 to combat AA forces, accidentally provoking ARSA's alleged attacks. The Arakan Liberation Army is the armed wing of the Arakan Liberation Party (ALP). Founded in 1968, the ALA signed a bilateral cease-fire agreement with the Burmese government in April 2012. The ALP is one of the eight EAOs to sign a multiparty cease-fire agreement with the Thein Sein government in October 2015. |

An International Crisis Group (ICG) report of December 2016 described the emergence of a Muslim insurgency, the Harakah al-Yaqin (HaY), in Burma.47 HaY is now known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA). ICG described HaY as led by a committee of emigres in Saudi Arabia. ICG described the group as not having a terrorist agenda. The ICG report warned that a disproportionate response by Burma "could create conditions for further radicalizing sections of the Rohingya population." Unconfirmed Indian media reports point to ties between elements within the Rohingya community and Pakistan's ISI and Pakistan- and Bangladesh-based terrorist groups. Some analysts believe that the IS or AQIS may use the Rohingya issue to boost recruitment to their ranks.48 Even if ARSA has no links with terrorist groups, the presence of so many dispossessed and abused Rohingya in Bangladesh would appear to make it a fertile ground for recruitment by terrorist groups.

Recent analysis is highlighting the potential that the Rohingya issue could become a new focus of international jihadism both as a cause to fight for and as a motivating issue for recruitment and support. One February 2017 think tank report said: "Leaders of global terrorist organizations, including al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, have sought to rally their supporters behind a much wider campaign against the Myanmar government and military.... These terrorist groups have defined Myanmar ... as the next great battleground for Islamists worldwide, following the wars in Syria and Iraq."49 It has also been observed that "marginalized refugees and angry sympathizers are vulnerable to recruitment by extremists who can exploit their causes."50

The Rohingya issue also has the potential to have an impact on Bangladesh's domestic political landscape and its international relations. The Bangladesh National Party has reportedly criticized the Awami League government for failing to describe the human rights crisis as genocide against the Rohingya and for failing to bring India and China in to resolve the crisis. The Bangladesh Islamist movement Hefazat-e-Islam, which reportedly runs 25,000 madrassas in Bangladesh and is based in Chittagong, has called for the liberation of Rakhine and threatened to wage jihad on Burma if it does not stop torturing Rohingya Muslims.51 An estimated 20,000 Hefazat supporters and other hardliners marched against the violence against the Rohingya in September 2017. This demonstration followed an earlier rally that gathered in support of the Rohingya in September 2017. Some of the demonstrators have urged the Bangladesh government to go to war with Burma and liberate Rakhine for the Rohingya.52 Some in the Bangladesh media have also gone as far as contemplating the arming of the Rohingya.53

Regional Dynamics

Beyond the risk of rising radicalization in the region, the Rohingya crises are creating pressure on regional relations. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Southeast Asia's primary regional forum, was unable to agree upon the text of a joint statement issued in September 2017 regarding the situation in Rakhine State, as Malaysia withheld its support, calling the text, "a misrepresentation of the reality of the situation."54 Malaysia, a predominately Muslim nation that has a moderate-sized Rohingya community, has been pushing ASEAN and the international community for a more active response to the crises, particularly regarding the alleged human rights violations. Indonesia, ASEAN's other predominately Muslim nation, has backed a more measured response, but its government also has to contend with pro-Rohingya political protests advocating a stronger stance on the issue. Other ASEAN members, such as Singapore, have maintained ASEAN's tradition of noninterference in the internal affairs of other nations, while supporting greater humanitarian assistance, condemning ARSA's attacks of October 2016 and August 2017, and calling for an end of violence in Rakhine State. ASEAN's internal disagreement on addressing the Rohingya crisis may preclude it playing a significant role in addressing the short-term and long-term challenges in responding to the crisis.

Evolving geopolitical dynamics between China and India may influence those governments' responses to the Rohingya humanitarian crisis. China's approach to the issue may be influenced by its investment in oil and gas pipelines that link Kunming in southern China with the Rakhine coast in Burma as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In addition to this energy link, China is seeking to build a deep water port and develop a special economic zone at Kyaukphyu in Rakhine state in order to lessen China's dependence on the Strait of Malacca. The importance of these trade and energy routes may mean that humanitarian or human rights concerns are secondary considerations relative to China's strategic and economic interests in its relationship with Burma. India's response to the Rohingya crisis will also likely be influenced by geopolitical concerns relative to countering rising Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean littoral. Prime Minister Modi has described Burma as a key pillar in India's "Act East" policy. As a result, India may also determine that its economic and security priorities may influence its approach to humanitarian or human rights issues in its relations with Burma.55

Overview of U.S.-Burma Policy

Congress and past Administrations have generally agreed that the overall objective for U.S. policy in Burma is to see the establishment of a democratically elected civilian government that respects the human rights and civil liberties of all of Burma's citizens or residents, regardless of ethnicity or religion. During the period of military rule (1962-2011), Congress passed progressively stricter sanctions on Burma to press Burma's military junta to stop the repression of the Burmese people and possibly transfer power back to a civilian government. From 2009 to 2016, the Obama Administration adopted a strategy of enhanced engagement under which greater contact was made with Burma's military leaders, while the sanctions were to remain in place until sufficient changes had taken place in Burma to warrant the removal of the sanctions. During President Obama's second term, that strategy shifted to removing sanctions to encourage further political and economic reforms in Burma.

The Trump Administration's Response

The Trump Administration's response to the Rohingya crisis has evolved over time. The initial statements from the State Department denounced the alleged ARSA attacks on the border outposts and expressed concern about "serious allegations of human rights abuses, including mass burnings of Rohingya villages and violence conducted by security forces and also armed civilians."56 As the scope of the crisis expanded, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson expressed his appreciation of the "difficult and complex situation" facing Aung San Suu Kyi, but called for the violence and persecution which "has been characterized by many as ethnic cleansing" to stop.57 Secretary Tillerson also said, "We need to support Aung San Suu Kyi and her leadership but also be very clear to the military that are power-sharing in that government that this [the violence] is unacceptable." On October 18, 2017, Secretary Tillerson responded to a question about the Rohingya crises by saying the following:

What's most important to us is that the world can't just stand idly by and be witness to the atrocities that are being reported in the area. What we've encouraged the military to do is, first, we understand you have serious rebel/terrorist elements within that part of your country as well that you have to deal with, but you must be disciplined about how you deal with those, and you must be restrained in how you deal with those. And you must allow access in this region again so that we can get a full accounting of the circumstances.58

During the U.N. Security Council meeting held on September 28, 2017, U.S. Ambassador Nikki Haley accused the Burmese government and the Tatmadaw of conducting "a brutal, sustained campaign to cleanse the country of an ethnic minority."59 She also said it was time for the United Nations to "consider action against Burmese security forces who are implicated in abuses and stoking hatred among their fellow citizens," and called for a global ban on arms sales to Burma's military.

Following the October 2, 2017, escorted tour of northern Rakhine State, the U.S. embassy joined 19 other embassies in a joint statement reiterating "our condemnation of the ARSA attacks of 25 August and our deep concern about violence and mass displacement since."60 The statement also welcomed Aung San Suu Kyi's commitment to investigate and address the allegations of human rights violations, and urged the Burmese government to permit the investigation team established by the U.N. Human Rights Commission to visit Rakhine State.

On October 23, 2017, the State Department announced that it would no longer grant visa ban waivers to Burmese military officers and was cutting off assistance to military units and officers involved in operations in Rakhine State (pursuant to the Leahy Law).61 The State Department also indicated that it was assessing authorities under the Tom Lantos Block Burmese JADE (Junta's Anti-democratic Efforts) Act of 2007 (JADE Act; P.L. 110-286) and the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act (P.L. 114-328, Subtitle F) to impose sanctions on those responsible for human rights violations. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Southeast Asia W. Patrick Murphy indicated that the State Department was still assessing "how best to describe the appalling treatment of the Rohingya," and that it was "not shying away from the use of any appropriate terminology."62 In testimony to both the House Committee on Foreign Affairs and the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Murphy would not refer to the situation in Rakhine State as ethnic cleansing, as the State Department had not made such a determination. The State Department's assessment is still pending.

A U.S. delegation headed by Acting Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration Simon Henshaw travelled to Bangladesh and Burma from October 29 to November 4, 2017, to discuss humanitarian and human rights issues. During the trip, Henshaw reportedly said the following:

During our meetings with Myanmar government officials, we told them that is their responsibility to return a secure and stable situation in Rakhine State. It is also their responsibility to investigate the reports of atrocities.63

While in Dhaka, Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Thomas Shannon stated, "We have a variety of sanctions available to us should we decide to use them. But right now ... our purpose is to solve the problem, not to punish." Following the trip, Henshaw said about humanitarian assistance, "the situation requires a lot more work ... our commitment has been followed by generous contributions from other donors. However, more is needed."64

U.S. Sanctions Policy and Restrictions

The United States started imposing sanctions on Burma in 1990 as the result of a general, but uneven decline in U.S. relations with Burma and the Tatmadaw since World War II. For the most part, the decline was due to what the U.S. government saw as a general disregard by Burma's ruling military junta for the human rights and civil liberties of the people of Burma.65

Despite the cooling of relations, U.S. policy toward Burma remained relatively normal until 1990. The United States accepted Burma as one of the original beneficiaries of its Generalized System of Preference (GSP) program in 1976. It also granted Burma Most Favored Nation (MFN, now referred to as Normal Trade Relations, or NTR) status, and supported the provision of developmental assistance by international financial institutions. There were also close military-to-military relations (including a major International Military Education and Training [IMET] program) until 1988.

The implementing of sanctions on Burma did not begin until after the Tatmadaw brutally suppressed a peaceful, popular protest that has become known as the 8888 Uprising. Starting in fall 1987, popular protests against the military government sprang up throughout Burma, reaching a peak in August 1988. On August 8, 1988, the military squashed the protest, killing and injuring an unknown number of protesters. In aftermath of the event, the military junta regrouped and the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) assumed power.

Between 1990 and 2008, Congress passed several laws, such as the Burmese Freedom and Democracy Act of 2003 and the Tom Lantos Block Burmese JADE (Junta's Anti-Democratic Efforts) Act of 2008 (JADE Act), imposing various types of political and economic sanctions on Burma. In addition, U.S. Presidents have imposed sanctions on Burma, such as the imposing of an arms embargo and the withdrawal of GSP benefits. The types of sanction imposed in the past included

- a prohibition on issuing visas to certain Burmese nationals;

- a general ban on the import of goods of Burmese origin;

- a ban on the import of goods produced by certain Burmese companies or containing materials originating in Burma;

- a prohibition of new U.S. investments in Burma;

- the suspension of Burma's trade benefits under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) program;

- the freezing of assets owned by certain Burmese nationals and held by U.S. financial institutions;

- a prohibition of providing financial services to certain Burmese nationals;

- a prohibition on the sales of arms to Burma;

- restrictions on the types of bilateral and multilateral aid that can be given to Burma; and

- limitations on interaction with the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw.

The sanction laws typically permitted the President to suspend or waive the imposition of the specified sanctions, if the President determined it was in the national interest or national security interest of the United States to grant such a suspension or waiver. Former President Obama used his authority to waive most of the sanctions on Burma. On October 7, 2016, President Obama issued E.O. 13472, waiving the economic sanctions described in Section 5(b) of the JADE Act.66 On December 2, 2016, President Obama released Presidential Determination 2017-04, ending restrictions on U.S. assistance to Burma as provided by Section 570(a) of the Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 1997.

Several non-economic restrictions, however, remain in effect, including

a prohibition on issuing visas to enter the United States to certain categories of Burmese officials, as provided by Section 5(a) of the JADE Act;

restrictions limiting the types of U.S. assistance to Burma; and

an embargo on arms sales to Burma.67

In addition, Congress has set limits on bilateral relations in appropriations legislation, including limitations on relations with the Tatmadaw (see section below). Section 7043(b) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), for example, places a number of restrictions on bilateral, international security, and multilateral assistance to Burma. Those restrictions remain in effect under the provisions of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 and Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-56).

U.S. Relations with the Burmese Military

The United States has limited engagement with the Burmese military in part due to existing legal restrictions. On June 9, 1993, the State Department's Bureau of Political-Military Affairs issued Public Notice 1820 suspending "all export licenses and other approvals to export or otherwise transfer defense articles or defense services to Burma."68 Section 5(a)(1)(A) of the JADE Act states that former and present leaders of the Burmese military "shall be ineligible for a visa to travel to the United States." Section 5(a)(1)(B) of the same act also makes officials of the Burmese military "involved in the repression of peaceful political activity or in other gross violations of human rights in Burma or in the commission of other human rights abuses" ineligible for a visa. The JADE Act provides for a presidential waiver of the visa restriction, which has been utilized with some regularity.

Section 7043(b) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31) contains the following restriction on relations with the Burmese military: "Funds appropriated by this Act under the heading 'Economic Support Fund' [ESF] for assistance for Burma ... may not be made available to any organization or entity controlled by the military of Burma." In addition, the section stipulates, "None of the funds appropriated by this Act under the headings 'International Military Education and Training' and 'Foreign Military Financing Program' may be made available for assistance for Burma." The same section also states that ESF funds "may not be made available to any individual or organization if the Secretary of State has credible information that such individual or organization has committed a gross violation of human rights, including against Rohingya and other minority groups, or that advocates violence against ethnic or religious groups and individuals in Burma." Finally, the section states, "the Department of State may continue consultations with the armed forces of Burma only on human rights and disaster response in a manner consistent with the prior fiscal year, and following consultation with the appropriate congressional committees." As previously stated, these restrictions remain in effect under the provisions of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 and Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-56).

Despite these restrictions, the Department of Defense and the Department of State have had limited interaction with the Burmese military. The Department of Defense has utilized unrestricted funding to support some Burmese officers to attend training courses at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies (APCSS) in Honolulu, HI. The training courses have included Advanced Security Cooperation, Comprehensive Security Responses to Terrorism, and Transnational Security Cooperation. Burmese military personnel have also participated in workshops hosted by the APSCC. Burmese military officers, as observers, have also attended regional military exercises with U.S. assistance, including "Cobra Gold," the largest annual multinational exercise in Asia.

Issues for Congress