Energy and Water Development: FY2018 Appropriations

The Energy and Water Development appropriations bill provides funding for civil works projects of the Army Corps of Engineers (Corps); the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) and Central Utah Project (CUP); the Department of Energy (DOE); the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC); and several other independent agencies. DOE typically accounts for about 80% of the bill’s total funding.

President Trump submitted his FY2018 budget proposal to Congress on May 23, 2017. The budget requests for agencies included in the Energy and Water Development appropriations bill totaled $34.189 billion (including offsets)—$4.261 billion (11.1%) below the FY2017 level. DOE nuclear weapons activities were proposed for a $994 million increase (10.7%). Final FY2018 funding for energy and water development programs was generally increased by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), which was signed by the President on March 23, 2018.

Major Energy and Water Development funding issues for FY2018 include

Water Agency Funding Reductions. The Trump Administration requested reductions of 17.2% for the Corps and 14.3% for Reclamation for FY2018. Those cuts were largely rejected by the House, the Senate Appropriations Committee, and the FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act.

Termination of Energy Efficiency Grants. DOE’s Weatherization Assistance Program and State Energy Program would have been terminated under the FY2018 budget request. The cuts were not included in the Consolidated Appropriation, and were also not approved by the House or by the Senate committee.

Reductions in Energy Research and Development. Under the FY2018 budget request, DOE research and development appropriations would have been reduced for energy efficiency and renewable energy (EERE) by 69.6%, nuclear energy by 30.8%, and fossil energy by 58.1%. The House approved most of the reductions in EERE research and development (48.1% cut from FY2017 enacted levels) but largely did not follow the proposed nuclear and fossil energy reductions (4.7% and no cut, respectively). The Senate committee largely did not follow the proposed reductions in EERE, nuclear energy, and fossil energy and instead included reductions of 7.3%, 10.9%, and 16.6%, respectively. Energy R&D funding was increased 12.9% by the FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act.

Nuclear Waste Repository. The Administration’s budget request would have provided new funding for the first time since FY2010 for a proposed nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain, NV. DOE would have received $110 million to seek an NRC license for the repository, and NRC would have received $30 million to consider DOE’s application. DOE would also have received $10 million to develop interim nuclear waste storage facilities. The requested funding for Yucca Mountain and interim storage was not included in the FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act. The House had approved the request but the Senate panel had not.

Elimination of Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy (ARPA-E). The Trump Administration proposed to eliminate funds for new research projects by ARPA-E, and called for terminating the program after currently funded projects were completed. The ARPA-E termination was approved by the House. The Senate committee recommended against the termination, providing $330 million—$24 million above the FY2017 level. The FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act increased funding for ARPA-E by 15.5%—to $353.3 million.

Plutonium Disposition Plant Termination. Construction of the Mixed-Oxide Fuel Fabrication Facility (MFFF), which would make fuel for nuclear reactors out of surplus weapons plutonium, was proposed for termination under the Trump Administration request. The Obama Administration had recommended termination since FY2015, but Congress had provided funds to continue construction. For FY2018, the House bill would have continued construction, but the Senate panel accepted the Administration request to terminate the project. The FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act conforms to provisions in the National Defense Authorization Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-91) that allow DOE to pursue an alternative plutonium disposal program if sufficient cost savings are projected.

Energy and Water Development: FY2018 Appropriations

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction and Overview

- Budgetary Limits

- Funding Issues and Initiatives

- Proposed Reductions to Corps and Reclamation Budgets

- Termination of Energy Efficiency Grants

- Proposed Cuts in Energy R&D

- Nuclear Waste Management

- Elimination of Energy Loans and Loan Guarantees

- International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor

- Elimination of Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy

- Upgrading Nuclear Weapons Infrastructure

- Surplus Plutonium Disposition

- Cleanup of Former Nuclear Sites

- Divest Transmission Infrastructure and Repeal Borrowing Authority for Power Marketing Administrations

- Bill Status and Recent Funding History

- Description of Major Energy and Water Programs

- Agency Budget Justifications

- Army Corps of Engineers

- Bureau of Reclamation

- Department of Energy

- Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy

- Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability

- Nuclear Energy

- Fossil Energy Research and Development

- Strategic Petroleum Reserve

- Science and ARPA-E

- Loan Guarantees and Direct Loans

- Nuclear Weapons Activities

- Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation

- Cleanup of Former Nuclear Weapons Production and Research Sites

- Power Marketing Administrations

- Title IV: Independent Agencies

- Nuclear Regulatory Commission

- Congressional Hearings

- House

- Senate

Tables

- Table 1. Status of Energy and Water Development Appropriations, FY2018

- Table 2. Energy and Water Development Appropriations, FY2010 to FY2018

- Table 3. Energy and Water Development Appropriations Summary

- Table 4. Army Corps of Engineers

- Table 5. Bureau of Reclamation and CUP

- Table 6. Department of Energy

- Table 7. Independent Agencies Funded by Energy and Water Development Appropriations

Summary

The Energy and Water Development appropriations bill provides funding for civil works projects of the Army Corps of Engineers (Corps); the Department of the Interior's Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) and Central Utah Project (CUP); the Department of Energy (DOE); the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC); and several other independent agencies. DOE typically accounts for about 80% of the bill's total funding.

President Trump submitted his FY2018 budget proposal to Congress on May 23, 2017. The budget requests for agencies included in the Energy and Water Development appropriations bill totaled $34.189 billion (including offsets)—$4.261 billion (11.1%) below the FY2017 level. DOE nuclear weapons activities were proposed for a $994 million increase (10.7%). Final FY2018 funding for energy and water development programs was generally increased by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), which was signed by the President on March 23, 2018.

Major Energy and Water Development funding issues for FY2018 include

- Water Agency Funding Reductions. The Trump Administration requested reductions of 17.2% for the Corps and 14.3% for Reclamation for FY2018. Those cuts were largely rejected by the House, the Senate Appropriations Committee, and the FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act.

- Termination of Energy Efficiency Grants. DOE's Weatherization Assistance Program and State Energy Program would have been terminated under the FY2018 budget request. The cuts were not included in the Consolidated Appropriation, and were also not approved by the House or by the Senate committee.

- Reductions in Energy Research and Development. Under the FY2018 budget request, DOE research and development appropriations would have been reduced for energy efficiency and renewable energy (EERE) by 69.6%, nuclear energy by 30.8%, and fossil energy by 58.1%. The House approved most of the reductions in EERE research and development (48.1% cut from FY2017 enacted levels) but largely did not follow the proposed nuclear and fossil energy reductions (4.7% and no cut, respectively). The Senate committee largely did not follow the proposed reductions in EERE, nuclear energy, and fossil energy and instead included reductions of 7.3%, 10.9%, and 16.6%, respectively. Energy R&D funding was increased 12.9% by the FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act.

- Nuclear Waste Repository. The Administration's budget request would have provided new funding for the first time since FY2010 for a proposed nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain, NV. DOE would have received $110 million to seek an NRC license for the repository, and NRC would have received $30 million to consider DOE's application. DOE would also have received $10 million to develop interim nuclear waste storage facilities. The requested funding for Yucca Mountain and interim storage was not included in the FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act. The House had approved the request but the Senate panel had not.

- Elimination of Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy (ARPA-E). The Trump Administration proposed to eliminate funds for new research projects by ARPA-E, and called for terminating the program after currently funded projects were completed. The ARPA-E termination was approved by the House. The Senate committee recommended against the termination, providing $330 million—$24 million above the FY2017 level. The FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act increased funding for ARPA-E by 15.5%—to $353.3 million.

- Plutonium Disposition Plant Termination. Construction of the Mixed-Oxide Fuel Fabrication Facility (MFFF), which would make fuel for nuclear reactors out of surplus weapons plutonium, was proposed for termination under the Trump Administration request. The Obama Administration had recommended termination since FY2015, but Congress had provided funds to continue construction. For FY2018, the House bill would have continued construction, but the Senate panel accepted the Administration request to terminate the project. The FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act conforms to provisions in the National Defense Authorization Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-91) that allow DOE to pursue an alternative plutonium disposal program if sufficient cost savings are projected.

Introduction and Overview

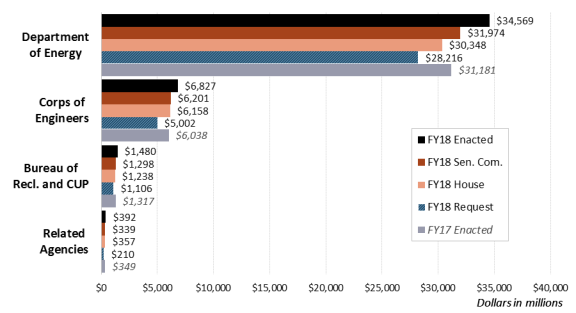

The Energy and Water Development appropriations bill includes funding for civil works projects of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps), the Department of the Interior's Central Utah Project (CUP) and Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), the Department of Energy (DOE), and a number of independent agencies, including the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). Figure 1 compares the major components of the FY2018 Energy and Water Development bill at each stage of consideration, along with the FY2017 enacted levels.

|

Figure 1. Major Components of Energy and Water Development Appropriations Bill |

|

|

Sources: S.Rept. 115-132, H.Rept. 115-230, and explanatory statement for Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (H.R. 1625) Includes some adjustments; see tables 4-7 for details. |

President Trump submitted his FY2018 budget proposal to Congress on May 23, 2017. The budget requests for agencies included in the Energy and Water Development appropriations bill totaled $34.189 billion (including offsets)—$4.261 billion (11.1%) below the FY2017 appropriation. The largest proposed increase was for DOE nuclear weapons activities, up by $994 million (10.7%). For the first time since FY2010, under the request, DOE would have received new funding to pursue an NRC license for a proposed nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain, NV, totaling $120 million (including funding for interim nuclear waste storage).

The FY2018 budget request proposed substantial reductions from the FY2017 level for DOE energy research and development (R&D) programs, including a cut of $1.454 billion (69.6%) in energy efficiency and renewable energy, $388 million (58.1%) in fossil fuels, and $314 million (30.8%) in nuclear. DOE science programs would have been cut by $920 million (17.1%). Programs targeted by the budget for elimination or phaseout included the Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy (ARPA-E), loan guarantee programs, and the ARC. Funding would have been cut for the Army Corps by $1.035 billion (17.0%), and the Bureau of Reclamation and CUP by $211 million (16.0%).

After passing a series of continuing resolutions, Congress largely rejected the Administration's proposed FY2018 budget cuts in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), which was signed into law March 23, 2018. Funding tables and other details are provided in an accompanying Explanatory Statement.1 Appropriations for energy and water development programs, provided by Division D of the act, rose by a total of $4.768 billion over the FY2017 level (12.4%), to $43.219 billion. That total is $9.030 billion (26.4%) above the Administration's FY2018 request. DOE programs receiving major funding increases for FY2018 include energy efficiency and renewable energy programs (totaling $2.322 billion, up 11.1%), nuclear energy R&D ($1.205 billion, up 18.5%), science programs ($6.260 billion, up 16.1%), ARPA-E ($353 million, up 15.5%) and atomic energy defense activities ($21.605 billion, up 9.2%). The Administration's request for the Yucca Mountain Repository and interim nuclear waste storage was not approved. Funding for the Corps totaled $6.827 billion (up 13.1%), and for Reclamation and CUP $1.480 billion (up 12.4%).

Leading up to the enactment of the omnibus funding measure, the House Appropriations Committee approved its version of the FY2018 Energy and Water Development Appropriations bill with a manager's amendment by voice vote on July 12, 2017. The committee-approved bill had total funding of $37.641 billion without scorekeeping adjustments—$809 million below FY2017 and $3.45 billion above the Administration request (H.R. 3266, H.Rept. 115-230). H.R. 3266 was combined with three other appropriations bill into H.R. 3219, the Make America Secure Appropriations Act, 2018, which was passed with amendments by the House on July 27, 1017. The text of H.R. 3219 was then included without further amendment in an FY2018 omnibus appropriations measure (H.R. 3354) that was passed by the House on September 14, 2017. The House-passed omnibus bill includes the Administration's proposed funding increase for DOE weapons activities, funding for Yucca Mountain, a decrease in funding for energy efficiency and renewable energy (EERE) R&D, and the elimination of ARPA-E and the loan programs. Most of the Administration's proposed reductions in nuclear and fossil energy R&D were not agreed to by the House, nor was the proposed elimination of the ARC.

The Senate Appropriations Committee approved its version of the Energy and Water Development appropriations bill (S. 1609, S.Rept. 115-132) on July 20, 2017, with total funding of $39.27 billion, including $545.4 million in rescissions. The committee recommended funding increases to DOE's weapons activities, funding for support of nuclear waste storage at private facilities, a decrease in funding for EERE R&D, and elimination of the Title 17 Loan Guarantee program.2 The committee recommended against the elimination of ARPA-E, instead approving an increase from the FY2017 enacted level.3

For FY2017, funding for energy and water development programs was provided by Division D of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), an omnibus funding measure passed by Congress May 4, 2017, and signed into law the following day. Total funding for Division D was $38.89 billion, offset by $436 million in rescissions. That total was $1.27 billion above the Obama Administration request and $1.54 billion over the FY2016 level, excluding rescissions. The Obama Administration also had proposed $2.26 billion in new mandatory funding for DOE, which was not approved. Proposed reductions for the Corps, Reclamation, and CUP were also rejected.4 For more information, see CRS Report R44465, Energy and Water Development: FY2017 Appropriations, by Mark Holt.

Budgetary Limits

Congressional consideration of the annual Energy and Water Development appropriations bill is affected by certain procedural and statutory budget enforcement measures. The procedural budget enforcement is primarily through limits associated with the budget resolution on total discretionary spending and subdivisions of this amount that apply to spending under the jurisdiction of each appropriations subcommittee. Statutory budget enforcement is derived from the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25).

The BCA established separate limits on defense and nondefense discretionary spending. These limits are in effect for each of the fiscal years from FY2012 through FY2021, and are primarily enforced by an automatic spending reduction process called sequestration, in which a breach of a spending limit would trigger across-the-board cuts of spending within that spending category.

The BCA's statutory discretionary spending limits were increased for FY2018 and FY2019 by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123), enacted February 9, 2018. For FY2018 BBA 2018 increased the defense limit by $80 billion (to $629 billion) and increased the nondefense limit by $63 billion (to $579 billion); for FY2019 it increased the defense limit by $85 billion (to $647 billion) and increased the nondefense limit by $68 billion (to $597 billion). (For more information, see CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch.)

Funding Issues and Initiatives

Several issues generated controversy during congressional consideration of Energy and Water Development appropriations for FY2018. The issues described in this section—listed approximately in the order they appear in the Energy and Water Development bill—were selected based on the total funding involved and the percentage of increases or decreases, the amount of congressional attention received, and their impact on broader public policy considerations.

Proposed Reductions to Corps and Reclamation Budgets

For the Army Corps of Engineers, the Trump Administration requested $5.002 billion for FY2018, which is $1.026 billion (17.2%) below the FY2017 appropriation. The deepest proposed cuts in the Corps budget were for Construction (45.6%), Mississippi River and Tributaries (30.1%), and Investigations (28.9%). The FY2018 request for the Bureau of Reclamation was $1.097 billion, a reduction of $209 million (14.3%) below FY2017. The Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2018 provided $6.827 billion for the Corps (13.1% above FY2017) and $1.470 billion for Reclamation (an increase of 12.5%). The House would have provided a 2% total increase for the Corps and a 5.9% decrease for Reclamation from the FY2017 appropriation. The Senate Appropriations Committee would have provided a 2.1% increase for the Corps and a 1.4% boost for Reclamation from their FY2017 levels. For more details, see CRS In Focus IF10671, Army Corps of Engineers: FY2018 Appropriations, by Nicole T. Carter, and CRS In Focus IF10692, Bureau of Reclamation: FY2018 Appropriations, by Charles V. Stern.

Termination of Energy Efficiency Grants

The FY2018 budget request proposed to terminate both the DOE Weatherization Assistance Program and the State Energy Program (SEP). The Weatherization Assistance Program provides formula grants to states to fund energy efficiency improvements for low-income households to reduce their energy bills and save energy. The SEP provides grants and technical assistance to states for planning and implementation of energy programs. Both programs are under DOE's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE). The weatherization program received $228 million and SEP $50 million for FY2017. According to the DOE budget justification, "These programs are not aligned with EERE's focus in FY2018 on early stage applied research and development for energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies."5 However, the Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2018 increased the grants by 10.1% from their FY2017 levels. For further background, see CRS Report R44980, DOE's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE): Appropriations Status, by Corrie E. Clark.

Proposed Cuts in Energy R&D

Appropriations for DOE research and development on energy efficiency, renewable energy, nuclear energy, and fossil energy would have been cut from $3.497 billion in FY2017 to $1.619 billion (53.7%) under the Administration's FY2018 budget request. This includes all funding except grants within EERE. "The FY2018 Budget Request for the Department of Energy is guided by the reassertion of the proper federal role as a supporter of early-stage R&D—in which the private sector has less incentive to invest—and an increased reliance on the private sector to fund later-stage R&D including demonstration and commercial deployment," according to the budget justification.6 Major proposed reductions included carbon capture and storage (-84%), nuclear fuel cycle R&D (-57%), sustainable transportation (-70%), renewable energy (-70%), advanced manufacturing (-68%), and building technologies (-66%).7 The proposed reductions within building technologies would also have eliminated the Home Performance with ENERGY STAR Program and all test procedure development and performance verification for ENERGY STAR.

The proposed energy R&D reductions were not included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, which instead increased R&D funding for energy efficiency and renewable energy by 11.2% over the FY2017 level, nuclear energy by 18.5%, and fossil energy by 8.8%. The explanatory statement directs DOE to work with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to review its 2009 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) related to the ENERGY STAR program and to provide a report to Congress within 90 days of enactment on whether the expected efficiencies for home appliance products have been achieved.8 The House had approved most of the Administration's proposed cuts in energy efficiency and renewable energy R&D but reduced nuclear and fossil energy R&D by only 4.7% and 0.0%, respectively, from their FY2017 levels. The Senate Appropriations Committee had denied most of the Administration's proposed reductions in EERE R&D and recommended a review of the 2009 MOU between DOE and EPA, and a report to Congress on the whether shifting responsibilities as described under the MOU achieved expected efficiencies for home appliance products. The panel also called for reducing R&D on nuclear energy by 9.8% and fossil energy by 14.3% from their FY2017 levels.

Nuclear Waste Management

The Administration's budget request would have provided new funding for the first time since FY2010 for a proposed nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain, NV, but it was not included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2018. Under the Administration request, DOE was to receive $110 million to seek an NRC license for the repository, and NRC would have received $30 million to consider DOE's application. DOE would also have received $10 million to develop interim nuclear waste storage facilities. DOE's total of $120 million in nuclear waste funding was to come from two appropriations accounts: $90 million from Nuclear Waste Disposal and $30 million from Defense Nuclear Waste Disposal (to pay for defense-related nuclear waste that would be disposed of in Yucca Mountain). DOE submitted a license application for the Yucca Mountain repository in 2008, but NRC suspended consideration in 2011 for lack of funding. The Obama Administration had declared the Yucca Mountain site "unworkable" because of opposition from the State of Nevada. The House voted to provide the proposed Yucca Mountain funding for FY2018, but the Senate Appropriations Committee did not, as has been the pattern in recent years. Also as in recent years, the Senate panel included an authorization for a pilot program to develop an interim nuclear waste storage facility at a volunteer site (§307). For more background, see CRS Report RL33461, Civilian Nuclear Waste Disposal, by Mark Holt.

Elimination of Energy Loans and Loan Guarantees

The FY2018 budget request would have halted further loans and loan guarantees under DOE's Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan Program and the Title 17 Innovative Technology Loan Guarantee Program. However, the Administration's proposal to terminate the two programs was not included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2018. The proposed elimination of the loan programs "reflects an increased reliance on the private sector to fund later-stage research, development, and commercialization of energy technologies and focuses resources toward early-stage research and development," according to the DOE budget justification.9 Under the budget proposal, DOE would have continued to administer its existing portfolio of loans and loan guarantees. According to the request, those administrative costs were to be covered by prior-year appropriations, except for $2 million in new appropriations for the innovative loan guarantee program, which would have been entirely offset by fees from existing loan guarantee recipients. Unobligated prior-year appropriations to cover potential government losses from the DOE loan programs (called "subsidy costs") would have been permanently cancelled. Unused prior-year authority, or ceiling levels, for loan guarantee commitments would have been rescinded. The Administration's proposal to terminate further Title 17 loan guarantees was included in both the House and the Senate Appropriations Committee bills. Both would have rescinded $160.6 million in remaining appropriations for paying subsidy costs for renewable energy and efficiency projects, and both would have rescinded the remaining authority to issue Title 17 loan guarantees.

International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor

The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), under construction in France, continues to draw congressional concerns about management, schedule, and cost. The United States is to pay 9.09% of the project's construction costs, including contributions of components, cash, and personnel. Other collaborators in the project include the European Union, Russia, Japan, India, South Korea, and China. The total U.S. share of the cost was estimated in 2015 at between $4.0 billion and $6.5 billion, up from $1.45 billion to $2.2 billion in 2008. As directed by P.L. 114-113, DOE issued a report in May 2016 on whether the United States should continue as an ITER partner or terminate its participation. DOE recommended that U.S. participation continue at least two more years but be reevaluated before FY2019.10 Congress appropriated $50 million for FY2017. DOE's request for FY2018 is $63 million. The House Appropriations Committee approved the request, saying in its report, "The Committee continues to believe the ITER project represents an important step forward for energy sciences and has the potential to revolutionize the current understanding of fusion energy."11 The Senate Appropriations Committee disapproved the request, recommending no further funding for ITER. The Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2018 provided $122 million for the project.

Elimination of Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy

The Trump Administration FY2018 budget would have eliminated the Advanced Research Projects Agency—Energy (ARPA-E), which funds research on technologies that are determined to have potential to transform energy production, storage, and use.12 However, funding for ARPA-E was increased by 15.5% by the Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2018—to $353.3 million. The Administration had proposed to end the program because "the private sector is better positioned to finance disruptive energy research and development and to commercialize innovative technologies."13 Because ARPA-E provides advance funding for projects for up to three years, oversight and management of the program would have been required through FY2021 even if funding for new projects were halted after FY2017, as proposed by the Administration. The FY2018 budget justification called for $20 million in new appropriations to be supplemented by $45 million in previous funding provided for research projects, which would have been reallocated for closing out the program. The ARPA-E office would have closed in FY2019, "at which point remaining monitoring and contract closeout activities would be transferred elsewhere within DOE."14 The House approved the Administration's proposal to terminate ARPA-E, but the Senate Appropriations Committee recommended that ARPA-E receive a $24 million increase over FY2017, to $330 million.

Upgrading Nuclear Weapons Infrastructure

The Weapons Activities account in DOE's National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) supports programs that maintain U.S. nuclear missile warheads and gravity bombs and the infrastructure programs that support that mission. In hearings on the FY2017 budget, NNSA Administrator Frank G. Klotz testified, "The age and condition of NNSA's infrastructure will, if not addressed, put the mission, the safety of our workers, the public, and the environment at risk. More than half of NNSA's facilities are over 40 years old while 30% of them date back to the Manhattan Project era."15 For FY2018, the Administration requested a 10.7% increase in Weapons Activities over the FY2017 level, to $10.239 billion. Infrastructure and Operations would get nearly flat funding (-0.2%), but the request showed some shifting of funds to bolster maintenance and recapitalization. The House approved the Administration's funding request. However, the Senate Appropriations Committee recommended $239.3 million less than the request, $10.0 billion, still an 8.2% increase over the FY2017 level. The Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2018 provided $10.642 billion for Weapons Activities, up 15.1% from FY2017. For more information, see CRS Report R44442, Energy and Water Development Appropriations: Nuclear Weapons Activities, by Amy F. Woolf.

Surplus Plutonium Disposition

The Mixed-Oxide (MOX) Fuel Fabrication Facility (MFFF), which would make fuel for nuclear reactors out of surplus weapons plutonium, has faced sharply escalating construction and operation cost estimates. Because of the rising costs and schedule delays, the Obama Administration proposed terminating MFFF in FY2015, FY2016, and FY2017 and pursuing alternative ways to dispose of surplus plutonium. However, Congress continued to appropriate construction funds for MFFF, including $335 million for FY2017. For FY2018, the Trump Administration also proposed to end the MFFF project, requesting $279 million to begin the termination process. The Trump Administration requested $9 million to begin a new Surplus Plutonium Disposition Project that would dilute surplus plutonium for disposal in a deep repository.16 The Obama Administration had also recommended the dilute-and-dispose option. The National Defense Authorization Act for FY2018 (P.L. 115-91, section 3121) authorized DOE to pursue an alternative plutonium disposal option if its total costs were determined to be "less than approximately half of the estimated remaining lifecycle cost of the mixed-oxide fuel program." The Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2018 (section 309) continues MFFF funding at $335 million but allows DOE to pursue an alternative disposal method using the procedure in the defense authorization act. The House had approved $340 million to continue MFFF construction in FY2018 and prohibited "the use of MOX funding to terminate the project while the Congress is considering an alternative approach for disposing of these materials." The Senate Appropriations Committee accepted the Administration's request for $270 million to terminate MFFF construction and $9 million for the Administration's alternative plutonium disposal project. Supporters of MFFF contend that the project is needed to satisfy an agreement with Russia on disposition of surplus weapons plutonium and promises to the State of South Carolina, where MFFF is located (at DOE's Savannah River Site). For more information, see CRS Report R43125, Mixed-Oxide Fuel Fabrication Plant and Plutonium Disposition: Management and Policy Issues, by Mark Holt and Mary Beth D. Nikitin.

Cleanup of Former Nuclear Sites

DOE's Office of Environmental Management (EM) is responsible for environmental cleanup and waste management at the department's nuclear facilities. The total FY2018 appropriations request for EM activities was $6.508 billion, an increase of $88 million (1.4%) from the FY2017 enacted appropriation. The three EM appropriations accounts are Defense Environmental Cleanup, which the Administration proposed to increase $132 million (2.4%) over FY2017; Non-Defense Environmental Cleanup, down $28.6 million (11.6%); and the Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning (D&D) Fund, down $15.3 million (2.0%). The Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2018 provided $7.126 billion for EM, up 11.0% from FY2017. The House had voted to provide flat funding for Defense Environmental Cleanup and Uranium Enrichment D&D, and a 10.0% reduction in Non-Defense Environmental Cleanup from the FY2017 appropriation. The Senate Appropriations Committee would have provided an increase for a total of $6.6 billion for EM activities. Although the Administration's request generally called for continued funding for ongoing cleanup and waste management projects across the complex of sites (with some decreases for specific projects), DOE noted that it may seek to negotiate with federal and state regulators to modify the "milestones" for certain projects. Milestones establish schedules for the completion of specific work under enforceable compliance agreements. Previous Administrations have taken a similar approach to modifying milestones that later may become infeasible to attain due to resource constraints or technical challenges.

Divest Transmission Infrastructure and Repeal Borrowing Authority for Power Marketing Administrations

DOE's FY2018 budget request included two mandatory proposals related to the Power Marketing Administrations (PMAs)—Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), Southeastern Power Administration (SEPA), Southwestern Power Administration (SWPA), and Western Area Power Administration (WAPA). PMAs sell the power generated by the dams operated by the Bureau of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers. The Administration proposed to divest the assets of the three PMAs that own transmission infrastructure: BPA, SWPA, and WAPA.17 These assets consist of thousands of miles of high voltage transmission lines and hundreds of power substations. The budget request projected that mandatory savings would total approximately $5.5 billion over a 10-year horizon associated with the sale of these assets, which could not be carried out without authorizing legislation. The proposal has been opposed by the American Public Power Association and the National Rural Electrical Cooperative Association, and was the subject of opposition letters to the Administration from bipartisan groups of 21 western Senators and 12 Pacific Northwest Members of Congress.

The Administration's budget also called for repealing $3.25 billion in borrowing authority provided to WAPA for transmission projects enacted under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). The proposal is estimated to save $4.4 billion over a 10-year horizon. Similar to the divestiture proposal, it also would need to be enacted in authorizing legislation. No congressional action was taken on those proposals.

Bill Status and Recent Funding History

Table 1 indicates the steps taken during consideration of FY2018 Energy and Water Development appropriations. (For more details, see the CRS Appropriations Status Table at http://www.crs.gov/AppropriationsStatusTable/Index.)

|

Subcommittee Markup |

Final Approval |

||||||||

|

House |

Senate |

House Committee |

House Passed |

Senate Committee |

Senate Passed |

Conf. Report |

House |

Senate |

Public Law |

|

6/28/17 |

7/18/17 |

7/12/17 |

7/27/17 |

7/20/17 |

none |

none |

3/22/18 |

3/23/18 |

3/23/18 |

Note: The text of the House Appropriations Committee-reported bill, H.R. 3266, was combined with three other appropriations bills into H.R. 3219, which passed the House July 27, 2017. The text of H.R. 3219 was then included without further amendment in an FY2018 omnibus appropriations measure (H.R. 3354) that was passed by the House on September 14, 2017. A compromise omnibus bill (H.R. 1625) was subsequently passed by the House and Senate and signed into law (P.L. 115-141).

Table 2 includes budget totals for energy and water development appropriations enacted for FY2010 through FY2017, plus the Trump Administration's FY2018 request.

Table 2. Energy and Water Development Appropriations,

FY2010 to FY2018

(budget authority in billions of current dollars)

|

FY2010 |

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

|

33.4 |

31.7 |

34.4a |

36.0b |

34.1 |

34.8 |

37.3 |

38.5 |

43.2 |

Source: Compiled by CRS from totals provided by congressional budget documents.

Notes: Figures exclude permanent budget authorities and reflect rescissions. Figures for FY2017 and previous years are enacted levels.

a. Includes $1.7 billion in emergency funding for the Corps of Engineers.

b. Includes $5.4 billion in emergency funding for the Corps of Engineers.

Description of Major Energy and Water Programs

The annual Energy and Water Development Appropriations bill includes four titles: Title I—Corps of Engineers—Civil; Title II—Department of the Interior (Central Utah Project and Bureau of Reclamation); Title III—Department of Energy; and Title IV—Independent Agencies, as shown in Table 3. Major programs in the bill are described in this section in the approximate order they appear in the bill. Previous appropriations and recommendations for FY2018 are shown in the accompanying tables, and additional details about many of these programs are provided in separate CRS reports as indicated. For a discussion of current funding issues related to these programs, see "Funding Issues and Initiatives," above.

Table 3. Energy and Water Development Appropriations Summary

(budget authority in millions of current dollars)

|

Title |

FY2016 Approp. |

FY2017 Request |

FY2017 Approp. |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 House |

FY2018 S. Comm. |

FY2018 Approp. |

|||||||

|

Title I: Corps of Engineers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Title II: CUP and Reclamation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Title III: Department of Energy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Title IV: Independent Agencies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Subtotal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Rescissions and Scorekeeping Adjustmentsa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

E&W Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: S.Rept. 115-132, H.Rept. 115-230, P.L. 115-31 and explanatory statement, S.Rept. 114-236, H.Rept. 114-532, Administration budget requests, H.Rept. 113-486, S.Rept. 114-54, Congressional Budget Office, H.R. 2029 explanatory statement, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2015/12/17/CREC-2015-12-17-bk2.pdf, H.R. 1625 explanatory statement, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/03/22/CREC-2018-03-22-bk2.pdf. Subtotals may include other adjustments.

a. Budget "scorekeeping" refers to official determinations of spending amounts for congressional budget enforcement purposes. These scorekeeping adjustments may include offsetting revenues from various sources and rescissions.

b. The grand total in the Explanatory Statement includes $26.9 million in rescissions but excludes $111.1 million in additional scorekeeping adjustments that would reduce the grand total to $37.185 billion, the subcommittee allocation shown in S.Rept. 114-197. See Senate Committee on Appropriations, Comparative Statement of New Budget Authority FY2016, January 12, 2016, p. 11.

c. The grand total on p. 4 of H.Rept. 115-230 is $37.562 billion, which includes an additional $79.376 million in scorekeeping adjustments not reflected here.

Agency Budget Justifications

FY2018 budget justifications for the largest agencies funded by the annual Energy and Water Development Appropriations bill can be found on the following web sites:

- Title I, Army Corps of Engineers, Civil Works, http://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/CivilWorks/Budget.aspx

- Title II

- Bureau of Reclamation, https://www.usbr.gov/budget/

- Central Utah Project, https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/fy2018_cupca_budget_justification.pdf

- Title III, Department of Energy, https://www.energy.gov/cfo/downloads/fy-2018-budget-justification

- Title IV, Independent Agencies

- Nuclear Regulatory Commission, http://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/nuregs/staff/sr1100/

- Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board, https://www.dnfsb.gov/content/fy-2018-congressional-budget-justification

- Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board, http://www.nwtrb.gov/plans/2018-CBJ.pdf

Army Corps of Engineers

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is an agency in the Department of Defense with both military and civilian responsibilities. Under its civil works program, which is funded by the Energy and Water Appropriations bill, the Corps plans, builds, operates, and in some cases maintains water resources facilities for coastal and inland navigation, riverine and coastal flood risk reduction, and aquatic ecosystem restoration. In recent decades, Corps studies, construction projects, and other activities have been generally authorized in Water Resources Development Acts before they were considered eligible for Corps appropriations. Congress enacted water resources development acts in June 2014, the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA, P.L. 113-121), and in December 2016, the Water Resources Development Act of 2016 (Title I of P.L. 114-322). These bills authorized new Corps projects and altered numerous Corps policies and procedures.18

Unlike highways and municipal water infrastructure programs, federal funds for the Corps are not distributed to states or projects based on a formula or delivered via competitive grants. Instead, the Corps generally is directly involved in the planning, design, and construction of projects that are cost-shared with nonfederal project sponsors.

In addition to the President's annual budget request for the Corps identifying funding for site-specific projects, Congress identified during the discretionary appropriations process many additional Corps projects to receive funding or adjusted the funding levels for the projects identified in the President's request.19 In the 112th Congress, site-specific project line items added by Congress (i.e., earmarks) became subject to House and Senate earmark moratorium policies. As a result, Congress generally has not added funding at the project level since FY2010. In lieu of the traditional project-based increases, Congress has included "additional funding" for select categories of Corps projects and provided direction and limitations on the use of these funds. For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10671, Army Corps of Engineers: FY2018 Appropriations, by Nicole T. Carter; CRS In Focus IF10361, Army Corps of Engineers: FY2017 Appropriations, by Charles V. Stern; and CRS In Focus IF10176, Army Corps of Engineers: FY2016 Appropriations, by Charles V. Stern. Previous appropriations and recommendations for FY2018 are shown in Table 4.

|

Program |

FY2015 Approp. |

FY2016 Approp. |

FY2017 Approp. |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 House |

FY2018 Sen. Com. |

FY2018 Approp. |

|

Investigations and Planning |

122.0 |

121.0 |

121.0 |

86.0 |

106.0 |

113.5 |

123.0 |

|

Construction |

1,639.5 |

1,862.3 |

1,876.0 |

1,020.0 |

1,697.5 |

1,703.2 |

2,085.0 |

|

Mississippi River and Tributaries (MR&T) |

302.0 |

345.0 |

362.0 |

253.0 |

301.0 |

375.0 |

425.0 |

|

Operation and Maintenance (O&M) |

2,908.5 |

3,137.0 |

3,149.0 |

3,100.0 |

3,519.3 |

3,481.5 |

3,630.0 |

|

Regulatory |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

|

General Expenses |

178.0 |

179.0 |

181.0 |

185.0 |

179.2 |

185.0 |

185.0 |

|

FUSRAPa |

101.5 |

112.0 |

112.0 |

118.0 |

118.0 |

117.0 |

139.0 |

|

Flood Control and Coastal Emergencies (FCCE) |

28.0 |

28.0 |

32.0 |

35.0 |

32.0 |

21.9 |

35.0 |

|

Office of the Asst. Secretary of the Army |

3.0 |

4.8 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

4.8 |

4.4 |

5.0 |

|

Total appropriations |

5,426.5 |

6,201.4 |

|||||

|

Rescission |

-28.0 |

-35.0 |

|||||

|

Total Title I |

5,454.5 |

5,989 |

6,037.8 |

5,002.0 |

6,157.8 |

6,166.4 |

6,827.0 |

Sources: S.Rept. 115-132, H.Rept. 115-230, P.L. 115-31 and explanatory statement, S.Rept. 114-236, H.Rept. 114-532, FY2016 budget request and Work Plans for FY2013, FY2014, and FY2015; S.Rept. 114-54; P.L. 113-2; H.R. 2029 explanatory statement; H.R. 1625 explanatory statement, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/03/22/CREC-2018-03-22-bk2.pdf. FY2017 request numbers can be found at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2017/assets/budget.pdf.

Bureau of Reclamation

Most of the large dams and water diversion structures in the West were built by, or with the assistance of, the Bureau of Reclamation. While the Army Corps of Engineers built hundreds of flood control and navigation projects, Reclamation's original mission was to develop water supplies, primarily for irrigation to reclaim arid lands in the West for farming and ranching. Reclamation has evolved into an agency that assists in meeting the water demands in the West while protecting the environment and the public's investment in Reclamation infrastructure. The agency's municipal and industrial water deliveries have more than doubled since 1970.

Today, Reclamation manages hundreds of dams and diversion projects, including more than 300 storage reservoirs, in 17 western states. These projects provide water to approximately 10 million acres of farmland and a population of 31 million. Reclamation is the largest wholesale supplier of water in the 17 western states and the second-largest hydroelectric power producer in the nation. Reclamation facilities also provide substantial flood control, recreation, and fish and wildlife benefits. Operations of Reclamation facilities are often controversial, particularly for their effect on fish and wildlife species and conflicts among competing water users during drought conditions.

As with the Corps of Engineers, the Reclamation budget is made up largely of individual project funding lines and relatively few "programs." Also as with the Corps, these Reclamation projects have often been subject to earmark disclosure rules. The current moratorium on earmarks restricts congressional steering of money directly toward specific Reclamation projects.

Reclamation's single largest account, Water and Related Resources, encompasses the agency's traditional programs and projects, including construction, operations and maintenance, dam safety, and ecosystem restoration, among others.20 Reclamation also typically requests funds in a number of smaller accounts, and has proposed additional accounts in recent years.

Implementation and oversight of the Central Utah Project (CUP), also funded by Title II, is conducted by a separate office within the Department of the Interior.21

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10692, Bureau of Reclamation: FY2018 Appropriations, by Charles V. Stern. Previous appropriations and recommendations for FY2018 are shown in Table 5.

|

Program |

FY2015 Approp. |

FY2016 Approp. |

FY2017 Approp. |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 House |

FY2018 Sen. Com. |

FY2018 Approp. |

|

Water and Related Resources |

978.1 |

1,119,0 |

1,155,9 |

960.0 |

1,091.8 |

1,150.3 |

1,332.1 |

|

Policy and Administration |

58.5 |

59.5 |

59.0 |

59.0 |

59.0 |

59.0 |

59.0 |

|

CVP Restoration Fund (CVPRF) |

57.0 |

49.5 |

55.6 |

41.4 |

41.4 |

41.4 |

41.4 |

|

Calif. Bay-Delta (CALFED) |

37.0 |

37.0 |

36.0 |

37.0 |

37.0 |

37.0 |

37.0 |

|

Rescission |

-0.5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Gross Current Reclamation Authority |

1,130.1 |

1,265.0 |

1,306.5 |

1,097.4 |

1,229.2 |

1,287.7 |

1,469.5 |

|

Central Utah Project (CUP) Completion |

9.9 |

10.0 |

10.5 |

9.0 |

9.0 |

10.5 |

10.5 |

|

Total, Title II Current Authority (CUP and Reclamation) |

1,140.0 |

1,275.0 |

1,317.0 |

1,106.4 |

1,238.1 |

1,298.2 |

1,480.0 |

Sources: S.Rept. 115-132, H.Rept. 115-230, P.L. 115-31 and explanatory statement, S.Rept. 114-236, H.Rept. 114-532, FY2018 and FY2017 budget requests, H.R. 83 Explanatory Statement, S.Rept. 114-54, H.R. 2029 explanatory statement, H.R. 1625 explanatory statement, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/03/22/CREC-2018-03-22-bk2.pdf. Excludes offsets and permanent appropriations.

Notes: Totals may not add due to rounding. CVP = Central Valley Project.

Department of Energy

The Energy and Water Development bill has funded all DOE programs since FY2005. Major DOE activities include research and development (R&D) on renewable energy, energy efficiency, nuclear power, and fossil energy; the Strategic Petroleum Reserve; energy statistics; general science; environmental cleanup; and nuclear weapons and nonproliferation programs. Table 6 provides the recent funding history for DOE programs, which are briefly described further below.

|

FY2015 Approp. |

FY2016 Approp. |

FY2017 Approp. |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 House |

FY2018 S. Com. |

FY2018 Approp. |

|

|

ENERGY PROGRAMS |

|||||||

|

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy |

1,914.2 |

2,069.2 |

2,090.2 |

636.1 |

1,085.5 |

1,937.0 |

2,321.8 |

|

Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability |

147.0 |

206.0 |

230.0 |

120.0 |

228.5 |

213.1 |

248.3 |

|

Nuclear Energy |

833.4 |

986.2 |

1,016.6 |

703.0 |

969.0 |

917.0 |

1,205.1 |

|

Fossil Energy R&D |

571.0 |

632.0 |

668.0 |

280.0 |

668.0 |

572.7 |

726.8 |

|

Naval Petroleum and Oil Shale Reserves |

20.0 |

17.5 |

15.0 |

4.9 |

4.9 |

4.9 |

4.9 |

|

Elk Hills School Lands Fund |

15.6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Strategic Petroleum Reserve |

200.0 |

212.0 |

223.0 |

188.4 |

252.0 |

180.0 |

260.4 |

|

Northeast Home Heating Oil Reserve |

1.6 |

7.6 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

|

Energy Information Administration |

117.0 |

122.0 |

122.0 |

118.0 |

118.0 |

122.0 |

125.0 |

|

Non-Defense Environmental Cleanup |

246.0 |

255.0 |

247.0 |

218.4 |

222.4 |

266.0 |

298.4 |

|

Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning Fund |

625.0 |

673.7 |

768.0 |

752.7 |

768.0 |

788.0 |

840.0 |

|

Science |

5,067.7 |

5,350.2 |

5,392.0 |

4,472.5 |

5,393.2 |

5,550.0 |

6,259.9 |

|

Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) |

280.0 |

291.0 |

306.0 |

-26.4 |

0 |

330.0 |

353.3 |

|

Nuclear Waste Disposal |

0 |

0 |

0 |

90.0 |

90.0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Departmental Admin. (net) |

126.0 |

131.0 |

143.0 |

145.7 |

159.5 |

142.7 |

189.7 |

|

Office of Inspector General |

40.5 |

46.4 |

44.4 |

49.0 |

49.0 |

49.0 |

49.0 |

|

Office of Indian Energy |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

16.0 |

0 |

|

Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loans |

4.0 |

6.0 |

5.0 |

2.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

|

Title 17 Loan Guarantee |

17.0 |

17,0 |

7.0 |

0 |

-411 |

0 |

23.0 |

|

Tribal Indian Energy Loan Guarantee |

0 |

0 |

0a |

0 |

0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Rescission (Clean Coal Technology) |

-6.6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

TOTAL, ENERGY PROGRAMS |

10,232,7 |

11,026.6 |

11,283.7 |

7,510.9 |

9,609.0 |

11,101.0 |

12,918.1 |

|

DEFENSE ACTIVITIES |

|||||||

|

National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) |

|||||||

|

Weapons Activities |

8,186.7b |

8,846.9 |

9,245.6 |

10,239.3 |

10,239.3 |

10,000.0 |

10,642.2 |

|

Nuclear Nonproliferation |

1,616.6 |

1,940.3 |

1,882.9 |

1,793.3 |

1,776.5 |

1,852.3 |

1,999.2 |

|

Naval Reactors |

1.234.0 |

1,375.5 |

1,419.8 |

1,479.8 |

1,486.0 |

1,436.7 |

1,620.0 |

|

Office of Admin./Salaries and Expenses |

369.6 |

363.8 |

390.0 |

418.6 |

412.6 |

396.0 |

407.6 |

|

Total, NNSA |

11,407.3 |

12,526.5 |

12,938.3 |

13,931.0 |

13,914.4 |

13,685.0 |

14,699.0 |

|

Defense Environmental Cleanup |

5,000.0 |

5,289.7 |

5,405.0 |

5,537.2 |

5,405.0 |

5,580.0 |

5,988.0 |

|

Defense Uranium Enrichment D&Dc |

463.0 |

0 |

563.0 |

0 |

0 |

788.0 |

0 |

|

Other Defense Activities |

754.0 |

776.4 |

784.0 |

815.5 |

825.0 |

784.0 |

840.0 |

|

Defense Nuclear Waste Disposal |

- |

- |

- |

30.0 |

30.0 |

0 |

0 |

|

TOTAL, DEFENSE ACTIVITIES |

17,624.3 |

18,592.7 |

19,690.3 |

20,313.7 |

20,174.4 |

20,837.0 |

21,497.0 |

|

POWER MARKETING ADMINISTRATION (PMAs) |

|||||||

|

Southeastern |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Southwestern |

11.4 |

11.4 |

11.1 |

11.4 |

11.4 |

11.4 |

11.4 |

|

Western |

93.4 |

93.4 |

95.6 |

93.4 |

93.4 |

93.4 |

93.4 |

|

Falcon and Amistad O&M |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

TOTAL, PMAs |

105.0 |

105.0 |

106.9 |

105.0 |

105.0 |

105 |

105.0 |

|

DOE total appropriations |

28,152.9 |

29,744.2 |

31,181.8 |

28,216.0 |

30,348.4 |

31,974.0 |

34,569.1 |

|

Offsets |

-236.1 |

-26.9 |

-435.8 |

-345.4 |

-460.0 |

-510.4 |

-49.0 |

|

Total, DOE |

27,916.8 |

29,717.3 |

30.746.0 |

27,870.6 |

29,888.4 |

31,463.6 |

34,520.1 |

Sources: S.Rept. 115-132, H.Rept. 115-230, P.L. 115-31 and explanatory statement, S.Rept. 114-236, H.Rept. 114-532, FY2018 and FY2017 budget requests, H.R. 83 Explanatory Statement, FY2015 budget request, H.Rept. 113-486, S.Rept. 114-54, Congressional Budget Office, H.R. 2029 explanatory statement, H.R. 1625 explanatory statement, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/03/22/CREC-2018-03-22-bk2.pdf.

Notes: Totals may not add due to rounding.

a. Appropriation of $9.0 million entirely offset by rescission.

b. This is the level as enacted in the FY2015 appropriations bill. The NNSA budget structure changed for FY2016, including transferring Nuclear Counterterrorism Incident Response from Weapons Activities to Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation. The FY2015 Weapons Activities figure comparable to the FY2016 figure is $8,007.7 million.

c. The amounts appropriated for Defense Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning (D&D) are transferred to the Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning Fund, and are treated as receipts that increase the balance of that fund available for appropriation in subsequent annual appropriations acts. Until appropriated from the fund, the amounts for Defense Uranium Enrichment D&D are not available to DOE for obligation to support D&D of federal uranium enrichment facilities.

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy

DOE's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) conducts research and development on transportation energy technology, energy efficiency in buildings and manufacturing processes, and the production of solar, wind, geothermal, and other renewable energy. EERE also administers formula grants to states for making energy efficiency improvements to low-income households and for state energy planning.

The Sustainable Transportation program area includes electric vehicles, vehicle efficiency, and alternative fuels. DOE's electric vehicle program aims to cut costs in half for battery and electric drivetrains for plug-in electric vehicles (EVs) by 2022.22 A key supporting technology goal is to cut the cost of battery capacity from $264/kilowatt-hour (kwh) in 2015 to $125/kwh by 2022.23 The fuel cell program targets a cost of $40 per kilowatt (kw) and a durability of 5,000 hours (equivalent to 150,000 miles) by 2020.24 For hydrogen produced from renewable resources, the target is to bring the cost below $4.00 per gasoline gallon-equivalent (gge) by 2020.25 Bioenergy goals include the development of "drop-in" fuels that would be largely compatible with existing energy infrastructure.

Renewable power programs focus on electricity generation from solar, wind, water, and geothermal sources. DOE's SunShot Initiative is aimed at making solar energy a low cost electricity source, with a goal of achieving costs of 3 cents per kwh for unsubsidized, utility-scale photovoltaics (PV) by 2030.26 For land-based windfarms, there is a cost target of 5.2 cents/kwh by 2020.27 For offshore wind settings, the target is 14.9 cents/kwh by 2020.28 The geothermal program aims to lower the risk of resource exploration and cut power production costs to 6 cents/kwh for newly developed technologies by 2030.29

In the energy efficiency program area, the advanced manufacturing program is intended to "catalyze research, development and adoption of energy-related advanced manufacturing technologies and practices."30 The building technologies program has a goal of reducing building energy use intensity 30% by 2030.31 According to EERE, the program is "paving the way for high performing buildings that could use 50-70% less energy than typical buildings."32

For more details, see CRS Report R44980, DOE's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE): Appropriations Status, by Corrie E. Clark.

Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability

The DOE Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability (OE) has the mission of supporting more economically competitive, environmentally responsible, secure, and resilient U.S. energy infrastructure. To achieve that mission, OE supports electric grid modernization and resiliency through research and development, demonstration projects, partnerships, facilitation, modeling and analytics, and emergency preparedness and response. It is the federal government's lead entity for energy sector-specific responses to energy security emergencies—whether caused by physical infrastructure problems or by cybersecurity issues.

DOE's 2015 Grid Modernization Multi-Year Program Plan describes the department's vision for "a future electric grid that provides a critical platform for U.S. prosperity, competitiveness, and innovation by delivering reliable, affordable, and clean electricity to consumers where they want it, when they want it, how they want it." To help achieve this vision, DOE has established three key national goals:

- 10% reduction in the economic costs of power outages by 2025;

- 33% decrease in the cost of reserve margins while maintaining reliability by 2025; and

- 50% decrease in the net integration costs of distributed energy resources by 2025.33

For more details, see CRS In Focus IF10874, DOE Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability: Organization and FY2019 Budget Request, by Corrie E. Clark, and CRS Report R44357, DOE's Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability (OE): A Primer, with Appropriations for FY2017, by Corrie E. Clark.

Nuclear Energy

DOE's FY2018 budget request for the Office of Nuclear Energy (NE) provides this mission statement: "To ensure that nuclear energy remains a viable energy option for the Nation, NE supports research and development activities designed to resolve the technical, cost, safety, waste management, proliferation resistance, and security challenges of nuclear energy."

The Reactor Concepts program area includes research on advanced reactors, including advanced small modular reactors, and research to enhance the "sustainability" of existing commercial light water reactors. Advanced reactor research focuses on "Generation IV" reactors, as opposed to the existing fleet of commercial light water reactors, which are generally classified as generations II and III. R&D under this program focuses on advanced coolants, fuels, materials, and other technology areas that could apply to a variety of advanced reactors. The program also is supporting NRC efforts to develop a new, "technology neutral" licensing framework for advanced reactors. Cost-shared research with the nuclear industry is also conducted on extending the life of existing commercial light water reactors beyond 60 years, the maximum operating period currently licensed by NRC. This subprogram is also conducting research to understand the Fukushima disaster and to develop accident prevention and mitigation measures.34

NE completed a program in FY2017 that provided design and licensing funding for small modular reactors (SMRs), which range from about 40 to 300 megawatts of electrical capacity. Support under this subprogram was provided to the NuScale Power SMR, which has a generating capacity of 50 megawatts, and for licensing two potential SMR sites. Under the company's current concept, up to 12 reactors would be housed in a single pool of water, which would provide emergency cooling. A design certification application for the NuScale SMR was fully submitted to NRC on January 25, 2017. Funding for first-of-a-kind (FOAK) engineering and other support for next-generation reactors, including SMRs, has continued under the Advanced Reactor Technologies subprogram. DOE awarded NuScale a $40 million FOAK matching grant on April 27, 2018.35

The Fuel Cycle Research and Development program conducts generic research on nuclear waste management and disposal. In general, the program is investigating ways to separate radioactive constituents of spent fuel for reuse or to be bonded into stable waste forms. Other major research areas in the Fuel Cycle R&D program include the development of accident-tolerant fuels for existing commercial reactors, evaluation of fuel cycle options, and development of improved technologies to prevent diversion of nuclear materials for weapons.

Fossil Energy Research and Development

Much of DOE's Fossil Energy R&D Program focuses on carbon capture and storage for power plants fueled by coal and natural gas. Major activities include the following:

- Carbon Capture subprogram for separating CO2 in both precombustion and postcombustion systems;

- Carbon Storage subprogram on long-term geologic storage of CO2, including storage site characterization, brine extraction storage tests, and postinjection monitoring technologies;

- Advanced Energy Systems subprogram on advanced fossil energy systems integrated with CO2 capture and sequestration; and

- Cross-Cutting Research and Analysis on innovative systems.

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10589, FY2019 Funding for CCS and Other DOE Fossil Energy R&D, by Peter Folger, CRS In Focus IF10589, FY2019 Funding for CCS and Other DOE Fossil Energy R&D, by Peter Folger, and CRS Report R44472, Funding for Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) at DOE: In Brief, by Peter Folger.

Strategic Petroleum Reserve

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR), authorized by the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (P.L. 94-163) in 1975, consists of caverns built within naturally occurring salt domes in Louisiana and Texas. The SPR provides strategic and economic security against foreign and domestic disruptions in U.S. oil supplies via an emergency stockpile of crude oil. The program fulfills U.S. obligations under the International Energy Program, which avails the United States of International Energy Agency (IEA) assistance through its coordinated energy emergency response plans, and provides a deterrent against energy supply disruptions.

By early 2010, the SPR's capacity reached 727 million barrels.36 The federal government has not purchased oil for the SPR since 1994. Beginning in 2000, additions to the SPR were made with royalty-in-kind (RIK) oil acquired by DOE in lieu of cash royalties paid on production from federal offshore leases. In September 2009, the Secretary of the Interior announced a transitional phasing out of the RIK Program. DOE has been conducting a major maintenance program to address aging infrastructure and a deferred maintenance backlog at SPR facilities.

In the summer of 2011, President Obama ordered an SPR sale in coordination with an International Energy Administration sale under treaty obligation because of Libya's supply curtailment. The U.S. sale of 30.6 million barrels reduced the SPR inventory to 695.9 million barrels.

In March 2014, DOE's Office of Petroleum Reserves conducted a test sale that delivered 5.0 million barrels of crude oil over a 47-day period that netted $468.6 million in cash receipts to the U.S. government (SPR Petroleum Account).

In 2015, DOE purchased 4.2 million barrels of crude oil for the SPR using proceeds from the 2014 test sale. According to the DOE budget justification, the SPR's drawdown capacity in FY2017 will be 4.25 million barrels per day. Currently, the SPR contains about 685 million barrels.37

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74) authorizes the sale of 58 million barrels of oil from the SPR. The authorized sales total 5 million barrels per fiscal year for 2018-2021, 8 million barrels in FY2022, and 10 million barrels per year in FY2023-FY2025. In addition, the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (P.L. 114-94) authorizes the sale of 66 million barrels of oil from the SPR. The authorized sales would total 16 million barrels in FY2023 and 25 million barrels in each of fiscal years 2024 and 2025.

For more information, see CRS Report R42460, The Strategic Petroleum Reserve: Authorization, Operation, and Drawdown Policy, by Robert Pirog.

Science and ARPA-E

The DOE Office of Science conducts basic research in six program areas: advanced scientific computing research, basic energy sciences, biological and environmental research, fusion energy sciences, high-energy physics, and nuclear physics. According to DOE's FY2018 budget justification, the Office of Science "is the Nation's largest Federal sponsor of basic research in the physical sciences and the lead Federal agency supporting fundamental scientific research for our Nation's energy future."38

DOE's Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) program focuses on developing and maintaining computing and networking capabilities for science and research in applied mathematics, computer science, and advanced networking. The program plays a key role in the DOE-wide effort to advance the development of exascale computing, which seeks to build a computer that can solve scientific problems 1,000 times faster than today's best machines. DOE has asserted that the department is on a path to have a capable exascale machine by the early 2020s.

Basic Energy Sciences (BES), the largest program area in the Office of Science, focuses on understanding, predicting, and ultimately controlling matter and energy at the electronic, atomic, and molecular level. The program supports research in disciplines such as condensed matter and materials physics, chemistry, and geosciences. BES also provides funding for scientific user facilities (e.g., the National Synchrotron Light Source II, and the Linac Coherent Light Source-II), and certain DOE research centers and hubs (e.g., Energy Frontier Research Centers, as well as the Batteries and Energy Storage and Fuels from Sunlight Innovation Hubs).

Biological and Environmental Research (BER) seeks a predictive understanding of complex biological, climate, and environmental systems across a continuum from the small scale (e.g., genomic research) to the large (e.g., Earth systems and climate). Within BER, Biological Systems Science focuses on plant and microbial systems, while Biological and Environmental Research supports climate-relevant atmospheric and ecosystem modeling and research. BER facilities and centers include three Bioenergy Research Centers and the Environmental Molecular Science Laboratory at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) seeks to increase understanding of the behavior of matter at very high temperatures and to establish the science needed to develop a fusion energy source. FES provides funding for the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project, a multinational effort to design and build an experimental fusion reactor. According to DOE, ITER "aims to generate fusion power 30 times the levels produced to date and to exceed the external power applied ... by at least a factor of ten." However, many U.S. analysts have expressed concern about ITER's cost, schedule, and management, as well as the budgetary impact on domestic fusion research.

The High Energy Physics (HEP) program conducts research on the fundamental constituents of matter and energy, including studies of dark energy and the search for dark matter. Nuclear Physics supports research on the nature of matter, including its basic constituents and their interactions. A major project in the Nuclear Physics program is the construction of the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams at Michigan State University.

A separate DOE office, the Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy (ARPA-E), was authorized by the America COMPETES Act (P.L. 110-69) to support transformational energy technology research projects. DOE budget documents describe ARPA-E's mission as overcoming long-term, high-risk technological barriers to the development of energy technologies.

For more details, see CRS Report R44888, Federal Research and Development Funding: FY2018, coordinated by John F. Sargent Jr.

Loan Guarantees and Direct Loans

DOE's Loan Programs Office provides loan guarantees for projects that deploy specified energy technologies, as authorized by Title 17 of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPACT05, P.L. 109-58), and direct loans for advanced vehicle manufacturing technologies. Section 1703 of the act authorizes loan guarantees for advanced energy technologies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and Section 1705 established a temporary program for renewable energy and energy efficiency projects.

Title 17 allows DOE to provide loan guarantees for up to 80% of construction costs for eligible energy projects. Successful applicants must pay an up-front fee, or "subsidy cost," to cover potential losses under the loan guarantee program. Under the loan guarantee agreements, the federal government would repay all covered loans if the borrower defaulted. This would reduce the risk to lenders and allow them to provide financing at below-market interest rates. The following is a summary of loan guarantee amounts that have been authorized (loan guarantee ceilings) for various technologies:

- $8.3 billion for non-nuclear technologies under Section 1703;

- $2 billion for unspecified projects from FY2007 under Section 1703;

- $18.5 billion ceiling for nuclear power plants ($8.3 billion committed);

- $4 billion allocated for loan guarantees for uranium enrichment plants;

- $1.183 billion ceiling for renewable energy and energy efficiency projects under Section 1703, in addition to other ceiling amounts, which can include applications that were pending under Section 1705 before it expired; and

- an appropriation of $161 million for subsidy costs for renewable energy and energy efficiency loan guarantees under Section 1703. If the subsidy costs averaged 10% of the loan guarantees, this funding could leverage loan guarantees totaling about $1.6 billion.

The only loan guarantees under Section 1703 were $8.3 billion in guarantees provided to the consortium building two new reactors at the Vogtle plant in Georgia. DOE conditionally committed an additional $3.7 billion in loan guarantees for the Vogtle project on September 29, 2017.39 Another nuclear loan guarantee is being sought by NuScale Power to build a small modular reactor in Idaho.40

Nuclear Weapons Activities

In the absence of explosive nuclear weapons testing, the United States has adopted a science-based program to maintain and sustain confidence in the reliability of the U.S. nuclear stockpile. Congress established the science-based Stockpile Stewardship Program in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1994 (P.L. 103-160). The goal of the program, as amended by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 (P.L. 111-84, §3111), is to ensure "that the nuclear weapons stockpile is safe, secure, and reliable without the use of underground nuclear weapons testing." The program is operated by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), a semiautonomous agency within DOE that Congress established in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000 (P.L. 106-65, Title XXXII). NNSA implements the Stockpile Stewardship Program through the activities funded by Weapons Activities account in the NNSA budget.

Most of NNSA's weapons activities take place at the nuclear weapons complex (the "complex"), which consists of three laboratories (Los Alamos National Laboratory, NM; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, CA; and Sandia National Laboratories, NM and CA); four production sites (Kansas City National Security Campus, MO; Pantex Plant, TX; Savannah River Site, SC; and Y-12 National Security Complex, TN); and the Nevada National Security Site (formerly Nevada Test Site). NNSA manages and sets policy for the complex; contractors to NNSA operate the eight sites.

The President's budget requested $10.239 billion for the Weapons Activities account in FY2018. The House, in H.R. 3219, the Make America Secure Appropriations Act, 2018, would have provided this amount. The Senate Appropriations Committee, in its version of the Energy and Water Development appropriations bill (S. 1609, S.Rept. 115-132), recommended $10 billion for Weapons Activities, a decrease of $239 million from the budget request. The Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2018 provided $10.642 billion for Weapons Activities.

There are three major program areas in the Weapons Activities account.

Directed Stockpile Work involves work directly on nuclear weapons in the stockpile, such as monitoring their condition; maintaining them through repairs, refurbishment, life extension, and modifications; conducting R&D in support of specific warheads; and dismantlement. The number of warheads has fallen sharply since the end of the Cold War, and continues to decline. As a result, a major activity of Directed Stockpile Work is interim storage of warheads to be dismantled; dismantlement; and disposition (i.e., storing or eliminating warhead components and materials).

Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) includes five programs that focus on "efforts to develop and maintain critical capabilities, tools, and processes needed to support science based stockpile stewardship, refurbishment, and continued certification of the stockpile over the long-term in the absence of underground nuclear testing." This area includes operation of some large experimental facilities, such as the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.