H.R. 23, the Gaining Responsibility on Water Act of 2017 (GROW Act)

In recent years, parts of the American West (i.e., the 17 states west of the Mississippi River) have been subject to prolonged drought conditions, including a severe drought in California that lasted from 2012 to 2016. Dating to the 112th Congress, several bills were proposed to address these conditions. The 114th Congress saw significant drought-related legislation enacted in the form of Subtitle J of the Water Resources Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN Act; P.L. 114-322). The WIIN Act included a number of provisions generally related to the Bureau of Reclamation (or Reclamation, a bureau within the Department of the Interior), as well as several provisions specifically focusing on the operations of the Central Valley Project (CVP), a large federal water project in California. Some, but not all, of those provisions are scheduled to sunset after five years.

Although by most metrics the drought in California has ended, debate continues regarding the possible detrimental effects of certain federal water supply-related authorities and the federal role in water resources development more broadly. Although some argue that rollback of existing environmental protections should be only a temporary measure taken during times of drought (if at all), others contend that the drought in California magnified an issue that needs to be addressed, regardless of hydrological conditions.

In the 115th Congress, multiple proposals (including those that were previously proposed but were not enacted in the WIIN Act) have been consolidated in H.R. 23, the Gaining Responsibility on Water Act of 2017 (GROW Act).

The House Rules Committee version of H.R. 23 included seven titles. Titles I-IV of the bill are for the most part specific to California and include directives for the operation of the CVP and amendments to the Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA; Title XXIV of P.L. 102-575) and the San Joaquin River Restoration Act (Title X of P.L. 111-11, the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009), among other things. Titles V-VII would be West-wide in their application and would include changes related to water supply development on federal lands and Reclamation’s project-development process. These titles also would include restrictions on the federal government’s abilities to exercise reserved water rights. Supporters of the bill argue that these changes would provide more water to users from existing and new sources while safeguarding existing state water rights. Opponents believe that the bill goes too far in rolling back environmental protections, which, along with the effects of other parts of the legislation (e.g., potential new storage projects), could be detrimental to species and their habitat.

Several of the bill’s titles have been considered and/or passed by the House in the 115th or prior congresses. Other titles are new or altered compared to language that has been considered previously. Based on past congressional debates, some provisions (in particular those that would make major changes to CVP operations and the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement) may be controversial. In considering these provisions, Congress may consider the trade-offs involved in proposed changes.

This report focuses on the most prominent provisions of H.R. 23. It provides relevant context and background for individual titles and sections, as well as a broad discussion of potential issues for Congress in considering this legislation.

H.R. 23, the Gaining Responsibility on Water Act of 2017 (GROW Act)

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Summary and Analysis of H.R. 23

- Title I—Central Valley Project Water Reliability

- Sections 101-102: New CVPIA Purposes, Definitions

- Section 103: CVP Contracts

- Section 104: Facilitated/Expedited Water Transfers

- Section 105: Changes to CVPIA Fish, Wildlife, and Habitat Restoration

- Section 106: Central Valley Project Restoration Fund

- Section 107: Additional Authorities

- Section 108: Bay-Delta Accord as Operational Guide

- Section 109: Inclusion of Hatchery Fish in ESA Determinations

- Section 110: California Environmental Quality Act Compliance

- Section 111: Additional Emergency Consultation

- Section 112: Applicants

- Section 113: San Joaquin River Settlement

- Issues and Legislative Considerations

- Title II—CALFED Storage Feasibility Studies

- Issues and Legislative Considerations

- Title III—California Water Rights

- Issues and Legislative Considerations

- Title IV—Miscellaneous

- Title V—Water Supply Permitting Act

- Issues and Legislative Considerations

- Title VI—Bureau of Reclamation Project Streamlining

- Issue and Legislative Considerations

- Title VII–Water Rights Protection Act

- Issues and Legislative Considerations

Figures

Summary

In recent years, parts of the American West (i.e., the 17 states west of the Mississippi River) have been subject to prolonged drought conditions, including a severe drought in California that lasted from 2012 to 2016. Dating to the 112th Congress, several bills were proposed to address these conditions. The 114th Congress saw significant drought-related legislation enacted in the form of Subtitle J of the Water Resources Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN Act; P.L. 114-322). The WIIN Act included a number of provisions generally related to the Bureau of Reclamation (or Reclamation, a bureau within the Department of the Interior), as well as several provisions specifically focusing on the operations of the Central Valley Project (CVP), a large federal water project in California. Some, but not all, of those provisions are scheduled to sunset after five years.

Although by most metrics the drought in California has ended, debate continues regarding the possible detrimental effects of certain federal water supply-related authorities and the federal role in water resources development more broadly. Although some argue that rollback of existing environmental protections should be only a temporary measure taken during times of drought (if at all), others contend that the drought in California magnified an issue that needs to be addressed, regardless of hydrological conditions.

In the 115th Congress, multiple proposals (including those that were previously proposed but were not enacted in the WIIN Act) have been consolidated in H.R. 23, the Gaining Responsibility on Water Act of 2017 (GROW Act).

The House Rules Committee version of H.R. 23 included seven titles. Titles I-IV of the bill are for the most part specific to California and include directives for the operation of the CVP and amendments to the Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA; Title XXIV of P.L. 102-575) and the San Joaquin River Restoration Act (Title X of P.L. 111-11, the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009), among other things. Titles V-VII would be West-wide in their application and would include changes related to water supply development on federal lands and Reclamation's project-development process. These titles also would include restrictions on the federal government's abilities to exercise reserved water rights. Supporters of the bill argue that these changes would provide more water to users from existing and new sources while safeguarding existing state water rights. Opponents believe that the bill goes too far in rolling back environmental protections, which, along with the effects of other parts of the legislation (e.g., potential new storage projects), could be detrimental to species and their habitat.

Several of the bill's titles have been considered and/or passed by the House in the 115th or prior congresses. Other titles are new or altered compared to language that has been considered previously. Based on past congressional debates, some provisions (in particular those that would make major changes to CVP operations and the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement) may be controversial. In considering these provisions, Congress may consider the trade-offs involved in proposed changes.

This report focuses on the most prominent provisions of H.R. 23. It provides relevant context and background for individual titles and sections, as well as a broad discussion of potential issues for Congress in considering this legislation.

Introduction

The Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), part of the Department of the Interior (DOI), is responsible for the construction and maintenance of many of the large dams and water diversion structures in the 17 states west of the Mississippi River.1 Reclamation was founded in 1902 to aid in the settlement of the arid American West. Today, Reclamation manages hundreds of dams and diversion projects, including more than 300 storage reservoirs in the 17 western states. These projects provide water to approximately 10 million acres of farmland and 31 million people. Reclamation is the largest wholesale supplier of water in the West and the second-largest hydroelectric power producer in the nation. Reclamation facilities also provide substantial flood control, recreation, and fish and wildlife benefits. Operations of Reclamation facilities often are controversial, particularly for their effects on fish and wildlife species and because of conflicts among competing water users.

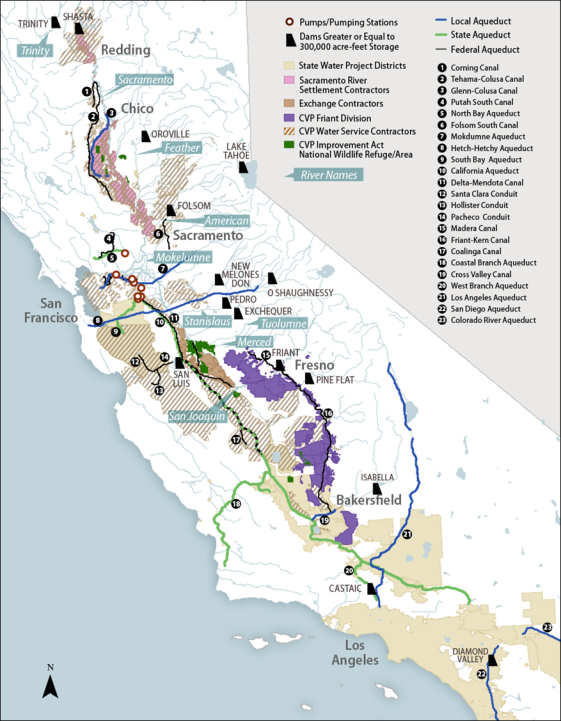

The multipurpose federal Central Valley Project (CVP) in California is one of Reclamation's largest water-conveyance systems (see Figure 1). The CVP extends from the Cascade Range in Northern California to the Kern River in Southern California. In an average year, it delivers approximately 5 million acre-feet of water to farms (including some of the nation's most valuable farmland); 600,000 acre-feet to municipal and industrial users; 410,000 acre-feet to wildlife refuges; and 800,000 acre-feet for other fish and wildlife needs, among other purposes. The project is made up of 20 dams and reservoirs, 11 power plants, and 500 miles of canals, as well as conduits, tunnels, and other storage and distribution facilities.2 A separate major project operated by the state of California, the State Water Project (SWP), delivers about 70% of its water to urban users (including water for approximately 25 million users in the South Bay [San Francisco Bay], Central Valley, and Southern California); the remaining 30% is used for irrigation. Two federal and state pumping facilities in the southern portion of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers' Delta (Delta) near Tracy, CA, are a hub for water deliveries from both systems. Further complicating water deliveries of the CVP and SWP is a complex system of state water rights, in which some water deliveries are prioritized based on prior agreements with water rights holders that predate the CVP (e.g., Sacramento River Settlement Contractors and San Joaquin River Exchange Contractors).

In recent years, parts of the West have been subject to prolonged drought conditions, including a severe drought in California that lasted from 2012 to 2016. Rain and snowstorms in Northern and Central California in the winter of 2016-2017 improved water supply conditions in the state in 2017.3 According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, as of July 2017, about 1% of the state was classified as suffering from severe drought conditions and more than 75% of the state was drought-free. This figure represents a drastic improvement from July 2016, when 59% of the state was in severe drought conditions, and July 2015, when 94% of the state fell under this designation.4

Although by most metrics the drought in California has ended,5 debate regarding the possible detrimental effects of certain federal water supply-related authorities, as well as the federal role in water resources development more broadly, continues. Although some argue that a rollback of existing environmental protections should be only a temporary measure taken during times of drought (if at all), others contend that the drought in California magnified an issue that needs to be addressed, regardless of hydrological conditions. They also note that the need for expedited construction of new surface water storage exists throughout the West.

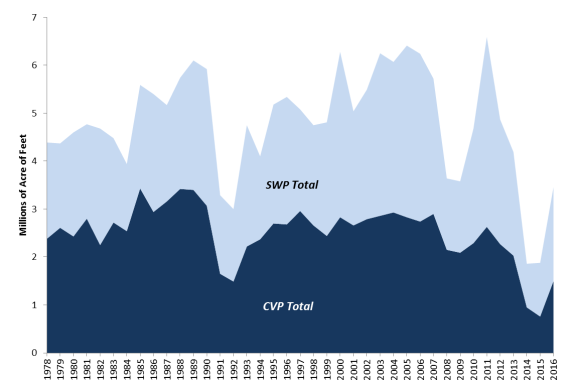

Central to addressing water shortages in California from the federal and state perspective is the coordinated operation of the CVP and the SWP. Whereas the CVP serves mostly agricultural water contractors, the SWP serves largely urban or municipal and industrial contractors; however, both projects serve some contractors of both varieties. The operation of the SWP has been of interest to Congress because there is a federal nexus with respect to the CVP. In considering CVP-related questions, a key point of debate has been the extent to which recent delivery cutbacks have been due to drought, compared to other factors (i.e., environmental restrictions related to state water quality criteria and endangered species, among other things). Recent deliveries to CVP and SWP contractors are shown below in Figure 2.

|

|

Source: CRS from data provided by the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation: Total Annual Pumping at Banks, Jones, and Contra Costa Pumping Plants 1976-2016 (MAF). Notes: CVP = Central Valley Project; SWP = State Water Project. The spike in 2001 correlates to the filling of Diamond Valley reservoir and the ability of the SWP to export high excess winter flows; albeit in an overall dry year. The troughs in 1977, 1991-1992, 2008-2009, and 2012-2016 reflect exports during previous California droughts. |

Dating to the 112th Congress, several bills were proposed to address drought in California (including operations of the CVP) and elsewhere. The 114th Congress saw significant drought-related legislation enacted in the form of Subtitle J of the Water Resources Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN Act; P.L. 114-322). The WIIN Act included a number of provisions generally related to Reclamation, as well as several provisions specifically focusing on the operations of the CVP. Some, but not all, of those provision are scheduled to sunset after five years.

In the 115th Congress, multiple proposals (including those that were previously proposed but were not enacted in the WIIN Act) have been consolidated in H.R. 23, the Gaining Responsibility on Water Act of 2017 (GROW Act). Although some of these provisions cover areas not addressed in the WIIN Act, others appear to overlap with that legislation.

The House Rules Committee version of H.R. 23 included seven titles. Titles I-IV are for the most part specific to California. They include directives for the operation of the CVP and amendments to the Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA; Title XXXIV of P.L. 102-575) and the San Joaquin River Restoration Act (Title X of P.L. 111-11, the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009), among other things. Titles V-VII would be West-wide in their application and would include changes related to water supply development on federal lands and Reclamation's project development process. These titles also would include restrictions on the federal government's abilities to exercise reserved water rights. Supporters of the bill argue that these changes would provide more water to users from existing and new sources while safeguarding existing state water rights. Opponents believe that the bill goes too far in rolling back environmental protections, which, along with the effects of other parts of the legislation (e.g., potential new storage projects), could be detrimental to species and their habitats.

Several of the bill's titles have been considered and/or passed by the House in the 115th or prior congresses. Other titles are new or altered compared to language that has been considered previously. Based on past congressional debates, some provisions (in particular those that would preempt state law and make major changes to CVP operations and the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement) may be controversial. In considering these provisions, Congress may consider the trade-offs involved in proposed changes.

The remainder of this report focuses on the most prominent provisions of H.R. 23. It is not an exhaustive summary of the bill, but it provides relevant context and background for individual titles and sections. The report also provides a broad discussion of potential issues for Congress in considering this legislation.

Summary and Analysis of H.R. 23

H.R. 23 was introduced on January 3, 2017. The bill includes a wide range of water-related provisions dealing with management and operations of the CVP, as well as Reclamation policy more broadly. Titles I-IV are for the most part specific to California, whereas Titles V-VII would be West-wide in their application.

The provisions included in H.R. 23 are largely a combination of different sections of bills that were considered in recent congresses. In particular, many of H.R. 23's provisions in Title I appear similar to H.R. 3964 from the 113th Congress, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Valley Emergency Water Delivery Act. Other parts of Title I and the remainder of the bill appear largely similar to parts of H.R. 2898 in the 114th Congress, the Western Water and American Food Security Act of 2015. For the most part, provisions in H.R. 23 appear to be those from prior legislation that were not enacted in the WIIN Act. However, some of the proposed language in H.R. 23 appears to overlap with provisions that were enacted in the WIIN Act. This overlap could raise questions as to how these two pieces of legislation would be reconciled if H.R. 23 were enacted. A summary of each title of the bill is provided below.

Title I—Central Valley Project Water Reliability

Title I would make numerous changes to the management and operation of the federal CVP, including amendments to CVPIA.6 Among other things, it would alter CVPIA to broaden the purposes for which water previously dedicated to fish and wildlife can be used (by removing the directive to modify CVP operations to protect fish and wildlife with dedicated fish flows and making this action optional); add to the purposes a provision "to ensure" water dedicated to fish and wildlife purposes is replaced and provided to CVP contactors by the end of 2018 at the lowest "reasonably achievable" cost; change the definitions of fish covered by the act; broaden purposes for which Central Valley Project Restoration Fund (CVPRF) monies can be used;7 reduce revenues to the CVPRF; mandate that the CVP and SWP be operated under a 1994 interim agreement, the Bay-Delta Accord; and mandate development and implementation of a plan to increase CVP water yield by October 1, 2018.

Many of Title I's provisions appear similar to those introduced in previous legislation;8 in their previous consideration, some of these provisions were controversial. A brief summary of each section of Title I is provided below.

Sections 101-102: New CVPIA Purposes, Definitions

Sections 101 and 102 of H.R. 23 would amend the purposes and definitions of CVPIA. Section 101 would make changes to CVPIA's purposes, including an amendment to include replacement water for CVP contractors and expedited water transfers among said purposes of that act. Section 102 would amend the act's definition of anadromous fish to limit coverage to those fish found in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers as of October 30, 1992.9 The latter amendment would effectively change the baseline for fish protection and restoration and potentially set restoration goals at population levels after some species were already listed as endangered.

Section 103: CVP Contracts

Section 103 of the bill would amend Section 3404 of CVPIA, which includes certain limitations on contracts for water supply. Among other things, the bill would alter CVPIA's requirement that most water service and repayment contracts be renewed for periods of 25 years and would mandate a renewal period of 40 years.

Section 103(2) would direct that existing long-term repayment of water service contracts be administered under the Act of July 2, 1956.10 The 1956 act provides for contracts to have a provision allowing conversion of water service contracts (9(e) contracts) to repayment contracts (9(d) contracts). It also provides that contractors who have repaid obligations shall have a "first right" to a stated share of project water for irrigation "(to which the rights of the holders of any other type of irrigation water contract shall be subordinate) ... and a permanent right to such share or quantity," subject to state water rights laws and provided "that the right to the use of water acquired under the provisions of this Act shall be appurtenant to the land irrigated and beneficial use shall be the basis, the measure, and the limit of the right."11 Such a change would appear to give water service contractors long-term certainty over water supplies from the CVP. Finally, this section also would repeal certain authorities for fish and wildlife restoration charges that were authorized under Section 3404 of CVPIA and would direct that parties be charged only for water actually delivered. Currently, some contractors pay for water based on acreage irrigated under contracts with Reclamation, and they must pay for contracted water regardless of whether water is delivered to the entire area (in drought years, this provision can be particularly onerous).

Section 104: Facilitated/Expedited Water Transfers

Several provisions of Section 104 deal with water transfers. Section 104(1) would amend Section 3405 of CVPIA to direct the Secretary to "take all necessary actions" to facilitate and expedite water transfers in the CVP and would add a provision requiring a determination by reviewing parties as to whether the proposal is "complete" within 45 days.12 Further, it would add a new section that would prohibit environmental mitigation requirements as a condition to any transfer.13 Section 104 also would add a new subsection to Section 3405 of CVPIA, which would clarify that water transfers that could have been made before enactment of CVPIA may go forward without being subject to that act's requirements for water transfers. In addition, Section 104 would add language to specify that water use related to the CVP must be measured by contracting district facilities only up to the point where surface water is commingled with other water supplies. It also would eliminate the tiered pricing requirement and other revenue streams that fund fish and wildlife enhancement, restoration, and mitigation under the CVPRF, thus reducing CVPRF revenue collections.

Section 105: Changes to CVPIA Fish, Wildlife, and Habitat Restoration

A number of provisions in Section 105 address fish, wildlife, and habitat restoration under CVPIA. First, Section 105 would remove the existing mandate that the Secretary of the Interior modify CVP operations to provide flows to protect fish, making this action optional rather than required and stipulating the new term "reasonable water flows" to provide further guidance for this authority.14 Section 105 would direct that any such flows provided on an optional basis be derived from the 800,000 acre-feet of water for fish and wildlife purposes under Section 3406(b)(2) of the CVPIA (also known as (b)(2) water).15 Thus, flows in excess of this amount for fish and wildlife purposes would appear not to be authorized under this legislation. The 800,000 acre-feet for fish and wildlife purposes would be a ceiling rather than a floor under this provision. Section 105 also would remove the requirement that the Secretary of the Interior consult with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife regarding modification of CVP operations for fish and wildlife and instead would require consultation with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Section 105 of H.R. 23 also would allow (b)(2) flows to be used for purposes other than fish protection. Under this section, fish and wildlife purposes would no longer be the "primary" purpose of such flows. It also would adjust accounting for (b)(2) water by directing that all water used under that section be credited based on a methodology described in the legislation. It appears that state water quality requirements, the Endangered Species Act (ESA; P.L. 93-205), and all other contractual requirements could be met via use of the (b)(2) water if the bill is enacted; however, this is not entirely clear in the language. This section also would direct that (b)(2) water be reused.16

In addition, Section 105 would alter the provisions of CVPIA related to reductions in deliveries for (b)(2) water. It would mandate an automatic 25% reduction of (b)(2) water when Delta Division water supplies are forecast to be reduced by 25% or more from the contracted amounts.17 Currently under CVPIA, the Secretary is allowed to reduce (b)(2) deliveries by up to 25% when agricultural deliveries of CVP water are reduced. Thus, whereas under CVPIA the reduction was optional and could be up to 25%, under the amended section there would be a mandatory trigger for 25% reductions.

Finally, Section 105 would deem pursuit (as opposed to accomplishment) of fish and wildlife programs and activities authorized by the amended Section 3406 as meeting the mitigation, protection, restoration, and enhancement purposes of Section 3402 of CVPIA. This change would not bind managers to meeting goals; rather, it would appear to direct managers to implement conservation activities that aim to meet goals.

Section 106: Central Valley Project Restoration Fund

Section 106(a) would strike the CVPIA directive that not less than 67% of funds made available to the CVPRF be set aside to carry out habitat restoration and related activities. The funds in the CVPRF presumably would be made available for any purposes under the act (i.e., not just habitat restoration). This section also would prohibit the requirement of donations or other payments or any other environmental restoration or mitigation fees to the CVPRF as a condition to providing for the storage or conveyance of non-CVP water, delivery of surplus water, or for any water that is delivered for groundwater recharge. Finally, it would amend Section 3407(c) of CVPIA by not requiring the collection of payments to recover mitigation costs. The Secretary would retain general authority to collect and spend payments as provided for other activities under CVPIA.

Section 106(d) of H.R. 23 would set a maximum limit of $4 per megawatt hour for payments made to the CVPRF by CVP power contractors. Historically, these payments have fluctuated. Section 106(d) also would require completion of fish, wildlife, and habitat mitigation and restoration actions by 2020, thus shortening the likely time such payments would be in place and thereby reducing water and power contractor payments into the CVPRF. Currently, the CVPRF payments continue until restoration actions are complete; then, payments are to be cut substantially.18 Section 106(d) would establish an advisory board responsible for reviewing and recommending CVPRF expenditures. The board would be made up primarily of water and power contractors (10 of 12 members), with the other two members designated at the Secretary's discretion.

Section 107: Additional Authorities

Section 107 would make a number of changes that address the authority for rates, additional storage, construction, and reporting requirements. These changes include amending the CVPIA to provide the Secretary with authority to use CVP facilities to transfer, impound, or otherwise deliver non-project water for "beneficial purposes." The section also would direct that amounts charged for this water not be provided to the CVPRF.

Section 107(c) would require a least-cost plan by the end of FY2017 to increase CVP water supplies by the amount of water dedicated and managed for fish and wildlife purposes under CVPIA, as well as to meet all purposes of the CVP, including contractual obligations.19 This section also would require implementation of the water plan (including any construction of new water storage facilities that might be included in the plan), beginning on October 1, 2017, in coordination with the state of California. Under the bill, if the plan fails to increase the water supply by 800,000 acre-feet by October 1, 2018, implementation of any nonmandatory action under Section 3406(b)(2) (including the actions made optional under Section 105) would be suspended until the increase is achieved.

Section 107(e) would authorize the Secretary to partner with local joint power authorities and others in pursuing storage projects (e.g., Sites Reservoir, Upper San Joaquin Storage, Shasta Dam and Los Vaqueros Dam raises) originally authorized for study under P.L. 108-361 (also known as CALFED) but would prohibit federal funds from being used for financing and constructing the projects. The section would authorize construction of these facilities with no further action, so long as no federal funds are used. Other parts of the bill (e.g., Section 204) appear to address construction of some of these facilities in a different manner (see "Title II—CALFED Storage Feasibility Studies," below). It is not clear how the two sections are intended to interact. Similarly, it is not clear how these provisions would affect these projects going forward under the WIIN Act.20

Section 108: Bay-Delta Accord as Operational Guide

Section 108(a) would direct that the CVP and the SWP be operated "in strict conformance" with a 1994 agreement commonly known as the Bay-Delta Accord.21 Among other things, the accord set maximum restrictions on water exports from the Delta, which were, in some cases, less restrictive than those in place today. Section 108(a) also states that the Bay-Delta Accord should be implemented "without regard to the [ESA] or any other law pertaining to operation of the [CVP] and [SWP]."22 Thus, some note that the bill preempts any federal or state laws that conflict with the accord. It is not clear how implementation of the accord would affect implementation of the WIIN Act, which also provided directives for CVP operations. Although the bill does not explicitly repeal portions of WIIN, there does appear to be overlap between the two pieces of legislation. For instance, if the CVP were to be operated "in strict conformance" with the Bay Delta Accord and without regard to ESA, as required under this section, it would appear to negate the changes under the WIIN Act that authorized certain operational parameters based on the current biological opinion (BiOp) for CVP operations.

Section 108(b) would prohibit federal or state adherence to any condition restricting the exercise of valid water rights in order to conserve, enhance, recover, or otherwise protect any species that is affected by operations of the CVP or SWP. It also would prohibit the state of California, including any agency or board of the state, from restricting water rights to protect any "public trust value" pursuant to the state's Public Trust Doctrine." Section 108(c) would provide that no costs associated with this section may be imposed on CVP contractors, other than on a voluntary basis. Finally, Section 108(d) would explicitly preempt state law regarding catch limits for non-native fish that prey on native fish species (e.g., striped bass) in the Bay-Delta.

Section 109: Inclusion of Hatchery Fish in ESA Determinations

Section 109 would mandate that hatchery fish be included in making determinations regarding anadromous fish covered by H.R. 23 under the ESA. Currently, hatchery fish are not included in population estimates of protected species, due largely to their different genetic makeup from wild fish. The inclusion of these fish eventually could lessen some ESA restrictions on water conveyance compared to current levels.

Section 110: California Environmental Quality Act Compliance

Section 110 would deem compliance under the California Environmental Quality Act to suffice for compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA, 42 U.S.C. §§4321-4347) for any project related to the CVP or related deliveries, including permits under state law. This provision would allow CVP projects and deliveries that conform to state law to circumvent traditional NEPA requirements. A potential benefit of this approach might be to speed up project-approval processes. A potential downside might be a less thorough—or at least different—assessment of the environmental impacts of the proposed project or action.

Section 111: Additional Emergency Consultation

Under Section 111, if adjustments to operating criteria other than those granted under Section 108 (adherence to the Bay-Delta Accord) are recommended by DOI and the Sacramento Valley Index is 6.5 or lower or the state requests it,23 no mitigation requirements would be associated with those changes until either the final index is 7.8 or greater, or two years from the date of the state's request. Furthermore, during any years in which mitigation is required, Section 111 also would provide that any mitigation measures that are provided for must be associated with quantitative data that demonstrate harm to species. These provisions would appear to reduce ESA-related mitigation requirements for emergency operational adjustments, both in drought years and in other years.

Section 112: Applicants

Section 112 would extend to SWP and CVP contractors the rights of applicants for consultation under ESA, in the event that consultation or reconsultation over the operation of the CVP is initiated in the future. Such a change potentially would afford these entities a stronger role in the consideration of project requests by resource agencies and the formulation of related mitigation plans and activities. Related changes were enacted in Section 4004 of the WIIN Act. Although that bill did not formally direct that contractors be designated as applicants under ESA, it afforded them many of the same rights as applicants. Thus, the magnitude of this change, were it to be enacted, is unclear.

Section 113: San Joaquin River Settlement

Section 113 would make multiple changes to the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement Act (SJRRS; Title X of P.L. 111-11), enacted in 2009, and to a related settlement agreement that is currently being implemented by Reclamation (see below text box for additional background). In the past, a number of proposals have been put forward to effectively repeal the SJRRS. Section 113 would not explicitly repeal the settlement, but it would make changes to the settlement's contents by altering the current plan of implementation pursuant to the bill's requirements, among other things. Some argue that the processes set up under this section would result in either repeal or a significant restructuring of the settlement.

|

The San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement Historically, Central California's San Joaquin River supported large Chinook salmon populations. Since the Bureau of Reclamation's Friant Dam on the San Joaquin River became fully operational in the late 1940s, much of the river's water has been diverted for agricultural uses. As a result, approximately 60 miles of the river became dry in most years, making it impossible to support Chinook salmon populations upstream of the Merced River confluence. In 1988, a coalition of environmental, conservation, and fishing groups advocating for river restoration to support Chinook salmon recovery sued the Bureau of Reclamation. A U.S. District Court judge subsequently ruled that operation of Friant Dam was violating state law because of its destruction of downstream fisheries. Faced with mounting legal fees, considerable uncertainty, and the possibility of dramatic cuts to water diversions, parties agreed to negotiate a settlement instead of proceeding to trial on a remedy regarding the court's ruling. A settlement agreement was reached in the fall of 2006. Implementing legislation was debated in the 110th and 111th Congresses (H.R. 4074, H.R. 24, and S. 27) and a law was passed in 2010 (Title X of P.L. 111-11). The San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement Agreement and its implementing legislation call for new releases of water from Friant Dam to restore fisheries (including salmon) in the San Joaquin River and for efforts to mitigate water supply losses due to the new releases, among other things. Because increased water flows for restoring fisheries (known as restoration flows) would reduce diversions of water for off-stream purposes, such as irrigation, hydropower, and municipal and industrial uses, the settlement and its implementation have been controversial. The quantity of water used for restoration flows and the quantity by which water deliveries would be reduced are related, but the relationship is not necessarily one-for-one, due to flood flows in some years and other factors.24 Under the settlement agreement, no water would be released for restoration purposes in the driest of years; thus, the agreement would not reduce deliveries to Friant contractors in those years. Additionally, in some years, the restoration flows released in late winter and early spring may free up space for additional runoff in Millerton Lake, potentially minimizing reductions in deliveries later in the year—assuming Millerton Lake storage is replenished. Consequently, how deliveries to Friant water contractors might be reduced in any given year depends on many factors. |

Section 113 of the bill would amend the SJRRS in a number of ways. Among the changes, key provisions under this section would

- require that the Secretary of the Interior and the governor of California make a determination, based on a number of factors, as to whether to continue with implementation of the settlement within one year of the bill's enactment. If it is determined that the SJRRS should not be implemented, then the officials are to develop a plan for creating a warm-water fishery downstream of Friant Dam but upstream of Gravelly Ford. If it is determined that the settlement should be implemented, H.R. 23 would establish a new framework for implementation, including priority listing of restoration projects and other conditions and requirements;

- allow for the release of flows under the SJRRS only if mitigation actions, including actions to mitigate the effects of the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement on landowners, have been implemented;

- direct that the settlement may not result in material adverse impacts to third parties, including groundwater seepage or groundwater rising above a threshold of 10 feet below the surface;

- require that costs for any fish barriers that need to be installed pursuant to ESA will be paid by DOI;

- forbid the acquisition of land to implement the SJRRS through eminent domain;

- declare that Sections 5930-5948 of the California Fish and Game Code and other applicable federal laws and the settlement agreement are met through compliance with the bill's provisions; and

- declare that under conditions in which flows beyond Exhibit B of the SJRRS are recommended, then the authority to implement the settlement would terminate.

Unlike other parts of Title I, there has been limited consideration of Section 113's provisions to date.25 Taken as a whole, it is not clear how such actions would affect the stipulated San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement Agreement or how parties to the settlement agreement or other stakeholders might react to these changes if they were enacted.

Issues and Legislative Considerations

Many of the provisions in Title I entail trade-offs. For example, Section 102 would limit the scope and definition of fish stocks receiving protection under CVPIA. This change may benefit some stakeholders who might stand to gain from fewer protections (i.e., more water), but it is strongly opposed by others who oppose any drop-off in protections. In addition, other changes to CVPIA, such as broadening the use of water flows and expanding the use of funds for fish and wildlife restoration under Section 105 may provide more water to irrigators or other water users under certain circumstances but may lower conservation efforts for salmon and other fish populations. Similar trade-offs characterize other sections of Title I, such as directing the renewal of existing contracts for 40 year periods under Section 103. Some might contend that this provision attempts to circumvent future NEPA review, but others might suggest that it could streamline the regulatory process to provide more water (and certainty of water supplies) to users.

Section 108 of H.R. 23, which directs the Secretary to operate the CVP and SWP according to principles outlined in the 1994 Bay-Delta Accord (a document no longer in effect), is likely to be among the controversial provisions of the bill. Some oppose this provision due to its potential to preempt state law and prohibit operational restrictions to protect species. They note that such an approach has the potential to alter the distribution of water deliveries associated with the CVP and SWP and could set a negative precedent for other areas. Supporters note that such a change is warranted due to its potential to make more water available to some users than under current law and regulatory restrictions, which they argue are overly stringent and ineffective.

Section 113 may be similarly controversial for its changes to the SJRRS. This section would alter ongoing implementation of the SJRRS and declare that the legislation satisfies certain requirements of California state law. Opponents argue that the changes would preempt state law, effectively repeal the implementing legislation, and amount to a significant setback for restoring the San Joaquin river fishery. Proponents of these changes argue that the settlement has fallen short of its goals and has had negative impacts on water users, thus the new strategy is justified.

Overall, provisions under this title could be interpreted as weakening environmental protections and restrictions imposed under the CVPIA, ESA, and SJRRS. Whether some or all of these authorities have achieved their goals, and the extent to which they have resulted in unforeseen and/or unjustified effects on CVP and SWP water users, may be key to their consideration. Another outstanding question is how some of the provisions in Title I (e.g., using the Bay-Delta Accord as an operational guide) might be reconciled with what was previously enacted under the WIIN Act, as well as other plans that might eventually impact CVP operations (e.g., the California WaterFix).26

The provisions under Title I of the bill raise questions regarding CVP water supplies for users and the environment. Selected questions relevant to this title might include the following:

- Exactly how much more water would be expected to be available to CVP water users under H.R. 23, under various scenarios?

- How much more water would be available for export from the Delta, and how would the bill affect reservoir releases?

- Would more water also be available at desirable times for CVP and SWP contractors in the Sacramento watershed (and if so, how much)?

- How might the bill affect the viability of listed species, and how much less water would be available for listed species?

- What effects would the bill have on water quality, recreation, and commercial and sport fishing?

Title II—CALFED Storage Feasibility Studies

H.R. 23 would attempt to expedite work on certain ongoing California surface water storage studies that originally were authorized under the Calfed Bay-Delta Authorization Act (CALFED; Title I of P.L. 108-361). To date, only one of the authorized studies (the Shasta Lake Water Resources Investigation) has been completed; the others are in various stages of the study process (see Table 1). Similar to bills introduced in previous Congresses, H.R. 23 proposes to establish deadlines to complete the CALFED studies and includes processes to facilitate their construction.

|

Study |

H.R. 23 Proposed Deadline |

|

Shasta Reservoir Water Resources Investigation |

Dec. 31, 2017 |

|

Upper San Joaquin/Temperance Flat Reservoir |

Dec. 31, 2017 |

|

Los Vaqueros Phase 2 Expansion |

Nov. 30, 2018 |

|

Sites Reservoir/NODOS |

Nov. 30, 2019 |

|

San Luis Dam Lowpoint Improvement Project |

Dec. 31, 2019 |

Source: CRS.

Notes: NODOS = North of Delta Offstream Storage; CALFED = Calfed Bay-Delta Authorization Act (Title I of P.L. 108-361).

Section 201 of H.R. 23 would direct Reclamation to complete ongoing feasibility studies for the new and augmented surface water storage studies in California that were authorized under CALFED. It also would authorize construction of one of these projects, the Temperance Flat Reservoir study, pending a positive feasibility report finding. However, pursuant to Section 204 of the bill, no federal funding could be used to construct this project. Thus, the construction authority would be contingent on 100% nonfederal funding.27 H.R. 23 also includes a directive in Section 202 for Reclamation to complete the study for Temperance Flat Reservoir; the bill would direct that the Secretary manage any land on the San Joaquin River recommended for designation or designated under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (16 U.S.C 1271 et seq.) in a manner that would not impede project activities, including environmental reviews and construction.

Issues and Legislative Considerations

With consideration to federal involvement in the CALFED surface water storage studies, Congress may evaluate whether to proceed with these projects and may gauge the potential for provisions in H.R. 23 to facilitate the studies' completion. Notably, the ability of the studies themselves to eventually further the goal of new water storage in California is unclear and may depend on a recommendation by the Administration to proceed with construction. Although many support proposed requirements for expedited completion of the studies as an important step toward construction of the projects, the previous Administration noted concerns with these provisions. In October 2015 testimony before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Obama Administration Deputy Secretary of the Interior Michael Connor noted that two of these projects (NODOS/Sites Reservoir and Los Vaqueros Reservoir) were dependent on participation and funding by nonfederal partners.28 The Obama Administration also argued that requiring completion of the remaining ongoing studies (Upper San Joaquin/Temperance Flat and San Luis Low Point Improvement Project) by a specific date could compromise Reclamation's ability to make an informed decision on construction and solicit adequate input from partners.29 It is unclear whether the Trump Administration shares any of these sentiments and whether the studies would be more or less likely to be completed if deadlines were in place. Notably, the WIIN Act authorized federal funding for these projects (either at the 50% or 25% cost-share level, depending on the project type) and authorized the construction of any projects that met certain thresholds set in that act. It is unclear whether the authority in this Section 204, which authorizes construction of the Temperance Flat Reservoir but only with 100% nonfederal financing, would negate the use of that funding. Additionally, it is not clear whether this authority (which authorizes nonfederal construction of the project, pending a positive feasibility study) or Section 107 of the bill (which authorizes nonfederal construction of all CALFED water storage studies, with or without feasibility studies) would guide implementation of the project.

Title III—California Water Rights

Title III of H.R. 23 includes provisions aimed at protecting certain California water rights priorities under existing law, confirming the obligations of the United States to honor state water rights laws, and operating the CVP in conformance with state law. These sections appear to be identical to legislation considered in previous Congresses (e.g., H.R. 2898 in the 114th Congress) and have a number of elements in common with (although not identical to) comparable provisions enacted under the WIIN Act.

Title III of H.R. 23 includes provisions that aim to protect California water rights priorities under state law, termed area of origin protections.30 Specifically, Section 301 would stipulate that any changes required under the bill that reduce water supplies to the SWP and increase supplies to the CVP must be offset and that reduced water supplies must be made available to the state. H.R. 23 would require the Secretary of the Interior to notify the state of California if implementation of the salmon and smelt BiOps under the act reduces environmental protections. Section 302 would direct the Secretary of the Interior to "adhere to California's water rights laws governing water rights priorities and to honor water rights senior to those held by the United States for operation of the Central Valley Project, regardless of the source of priority."31 Title III goes on to list several specific California Water Code sections. Section 303 includes language providing that "involuntary reductions" to contractor water supplies would not be allowed to result from the bill. H.R. 23 would apply only to CVP and SWP contractors.

Section 304 would set specific requirements that Reclamation provide "not less than 100 percent of ... contract water quantities" to agriculture water service contractors in the Sacramento River Watershed during wet, above-normal, and below-normal water years and "not less than 50 percent of their contract quantities" in dry years. This section also includes instructions for making allocations in all other types of years. Finally, Section 305 of H.R. 23 states that nothing in Title III shall preempt or modify existing obligations of the United States under Reclamation law to operate the CVP in conformity with state law, including water rights priorities.

Issues and Legislative Considerations

A potential issue is how the bill might affect water allocations under state and federal law, including CVP water allocation priorities. The bill contains specific directives to operate the CVP; some parties want assurances that maximizing water supplies to CVP and SWP water users south of the Delta—some of which are junior in priority under state law and CVP allocation priorities—will not result in any unintended shortages and would not affect other, more senior water users (or other water users in general). Overall, these protections raise questions including, among other things, how they would be reconciled with operational directives under other sections of the bill, as well as with other existing water rights that are not explicitly protected.

Some provisions in Sections 301-304 are similar to those enacted in Section 4005 of the WIIN Act. Given the partial overlap between the provisions in the proposed and enacted bills, it is unclear how these provisions would be reconciled if H.R. 23 were enacted. Additionally, previous Obama Administration officials raised concerns that these provisions, when combined with the operational requirements of H.R. 23, would make it difficult to meet the multiple authorized purposes of the CVP.32 It is unclear whether the current Administration shares this position.

Title IV—Miscellaneous

Title IV includes a number of disparate provisions that are collectively categorized as miscellaneous. A brief description of each section is included below:

- Section 401 would alter water supply accounting under CVPIA so that any restrictions on CVP water (except for certain releases to the Trinity River) to benefit fisheries since enactment of CVPIA would count toward the quantity of water that the Secretary of the Interior is to dedicate to environmental purposes (known as b(2) water) under CVPIA. Current law requires that only water for salmon "doubling" is counted toward these purposes.

- Section 402 would limit releases from Lewiston Dam during operation of the Trinity River Division of the CVP to amounts specified in a December 2000 environmental impact statement for the Trinity River Restoration Program. This limit would effectively bar additional releases for Trinity River fisheries. Such additional releases have been allowed in recent years to prevent fish kills, among other things.

- Section 403 would require an annual report on the purpose, authority, and environmental benefit of instream flow releases from the CVP and the SWP.

- Section 404 would stipulate that if there is consultation or reconsultation under Section 7 of the ESA for operations of the Klamath Project (Oregon), Klamath Project contractors would be accorded the rights of applicants in the consultation process.

- Section 405 states that in carrying out the act, the Secretaries of the Interior and Commerce should note congressional opposition to certain California State Water Resource Control Board proposals having to do with unimpaired flows in the San Joaquin River.

Title V—Water Supply Permitting Act

Title V, the Water Supply Permitting Act, would establish new procedures and requirements applicable to water storage projects undertaken by nonfederal entities (e.g., state agencies or private parties) in the Reclamation states on lands administered by DOI or the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).33 A similar bill, H.R. 1654, the Water Supply Permitting Coordination Act, was passed by the House on June 22, 2017. This title of H.R. 23 would establish Reclamation as the lead agency responsible for coordinating all reviews, analyses, opinions, statements, permits, licenses, or other federal approvals required for new surface water storage projects on lands administered by DOI and USDA. Provisions under Title V would not change existing NEPA requirements associated with permit issuance but would require Reclamation to establish and implement procedures that would be largely similar to those implemented by DOI and USDA as part of those agencies' respective permitting processes. Without explicitly referring to NEPA, provisions in Sections 503, 504, and 505 would establish certain responsibilities and requirements for lead and cooperating agencies that would be largely similar to those established by the White House Council on Environmental Quality in its regulations implementing NEPA. That is, Title V of H.R. 23 would appear to establish a new process that Reclamation would coordinate, but the bill would not eliminate any existing process. Each agency's interpretation and implementation of the directives in this title likely would determine whether, or the extent to which, the agency integrates the Reclamation-led process and the existing process the agency is required to complete to comply with NEPA.

Additionally, provisions in Section 504 would require Reclamation to implement a coordination process that involves

- instituting a new pre-application coordination process;

- preparing a unified environmental document that would serve as the record on which all cooperating agencies shall base any project-approval decisions;

- ensuring cooperating agencies make decisions on a given project within deadlines specified in Section 504; and

- appointing a project manager to facilitate the issuance of the relevant final approvals and to ensure fulfillment of any Reclamation responsibilities.

Section 506 would allow DOI to accept funds from a nonfederal project applicant to expedite the evaluation of permits related to the project.

Issues and Legislative Considerations

No provision in Title V would explicitly waive existing NEPA requirements associated with the issuance of permits or grants of right-of-way for federal land. That is, the title would establish procedures that Reclamation must implement to complete the environmental review process, but it would not explicitly direct DOI or USDA to change its own procedures for implementing NEPA or processing permit applications. Reclamation's interpretation of the directives in Title V would determine how the agency might integrate them with existing DOI and other federal agency procedures and how any new project coordination procedures would differ from the existing NEPA and permitting processes, should the bill be enacted. However, Title V does appear to include some requirements that would add steps to the project-approval process (e.g., the requirements related to the pre-application process, preparation of a unified environmental document, and data monitoring and record keeping).

Title VI—Bureau of Reclamation Project Streamlining

Under Title VI of H.R. 23, new storage projects potentially would be expedited and authorized for construction by Congress under a reporting process and a number of other changes proposed in Sections 601-606 of the bill. For instance, Section 603 of H.R. 23 would provide that any new studies initiated by the Administration after the date of enactment must be completed within three years, at a cost of no more than $3 million per project study. Section 605 would allow for the Secretary to enter into agreements with the nonfederal sponsor to support the planning, design, and permitting of projects. Section 606 would attempt to expedite construction authorizations of all projects by directing an annual report in which the Administration proposes Reclamation studies and construction projects for congressional authorization, including new projects, enhancements to existing projects, and federal projects proposed by nonfederal entities.34 This report would be similar to the process authorized for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) under the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA 2014; P.L. 113-121) and referred to in the WIIN Act.35 Congress would have discretion over whether to authorize some or all of the projects proposed by the Administration. These projects also would be authorized to receive an undetermined amount of financial support.

Title VI, which is similar to other legislation proposed in the 115th Congress,36 would apply to surface water projects undertaken, funded, or operated by Reclamation. According to previous congressional documents explaining the rationale for similar provisions considered in the 114th Congress,37 these provisions are modeled after a similar process established for Corps projects under WRRDA 2014.38 The provisions are intended to expedite project completion by accelerating the completion of (1) feasibility studies and reports (pursuant to Sections 603 and 604) and (2) environmental reviews for projects that require a feasibility study or an environmental impact statement (EIS; pursuant to Section 605).39 Currently, Reclamation integrates its feasibility report process with the preparation of the required NEPA analysis (EIS or environmental assessment).

With respect to project acceleration, a number of provisions in Section 605 would codify existing regulations that implement NEPA. However, some provisions could add to or change preexisting agency practices or requirements used to demonstrate compliance with NEPA or could change outside agencies' procedures for completing their respective decisionmaking processes. Some examples under the bill include

- deadlines for comment on a draft EIS that would be shorter than current comment periods;

- deadlines for outside agencies to make decisions under other federal laws that, if missed, must be reported to Congress;

- reporting requirements to allow a project's status to be tracked;

- financial penalty provisions applicable to federal agencies with some jurisdiction over a project if the agencies fail to make a decision within certain deadlines; and

- a three-year statute of limitations on claims related to a completed project study.

Section 607 of Title VI also clarifies that the two sections of the WIIN Act that authorized federal investment in new surface storage and other water supply projects shall not apply to projects under this title of the bill.

Issue and Legislative Considerations

Title VI creates a new reporting process that attempts to facilitate the proposal and authorization of new projects by Congress (and potentially would allow for a means to authorize these projects). A similar process is used for authorization of Corps studies and construction projects despite congressional moratoria on earmarks. Provisions under Title VI of H.R. 23 also have the potential to provide for a stronger nonfederal role in project implementation, in particular by allowing nonfederal entities to propose and provide financial support for new studies and requiring expedited completion of studies in general.

H.R. 23 would provide funding support only for new federal and nonfederal storage based on existing Reclamation law (i.e., up-front costs to be funded through federal appropriations and paid back over time, without interest for irrigation purposes). Previously, the Obama Administration argued against new storage that "perpetuates the historical federal subsidies available for financing water storage projects" and in some cases appeared to prefer projects that were state and locally led.40 Decisions between new projects using the traditional federal financing model and those adopting new, alternative arrangements could create questions in the discussion of H.R. 23. The need for and likelihood of authorization for new federal projects, as well as the appropriate split of responsibilities between federal and nonfederal stakeholders for new investments, also may be debated.

The WIIN Act included new authorities and authorized new funding to pursue both federally led projects and projects led by nonfederal interests (Section 4007), as well as new water reuse and recycling projects and desalination projects (Section 4009) that built on existing federal authorities. The language in Section 607 of H.R. 23 appears to exclude these projects from the broader processes outlined in Title VI. Thus, the bill appears to propose parallel authorization processes for WIIN Act projects and those carried out under this title.

Title VII–Water Rights Protection Act

H.R. 23 includes provisions under Title VII, Water Rights Protection, that are largely similar to H.R. 2939, the Water Rights Protection Act of 2017, a bill introduced in the 115th Congress that was ordered to be reported by the House Natural Resources Committee on June 27, 2017.41 Both bills were introduced in part due to concerns related to Forest Service efforts in recent years to require that permittees operating on Forest Service lands transfer their water rights to the federal government as a condition for permit renewal. The provisions under Title VII of H.R. 23 would attempt to prevent this requirement by, among other things, prohibiting the Forest Service and DOI from implementing permit conditions that require the transfer of private water rights to the federal government, as well as by prohibiting any requirements for permittees to apply for a water right in the name of the United States as a condition for their permit approval. It also would prohibit the conditioning or withholding of a permit on surface or groundwater withdrawals on any limitations that are not in accordance with state law. Finally, Title VII would require that federal agency policies recognize state water law and federal agencies coordinate with states to ensure consistency.

|

Federal Reserved Water Rights Federal reserved water rights often arise in questions of water allocation and uses related to federal lands. These rights coexist with water rights administered under state law. Federal reserved water rights were first recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court in Winters v. United States in 1908. Under the Winters doctrine, when the federal government reserves land from the public domain for a federal purpose, it also reserves water resources sufficient to fulfill the purpose of the reservation.42 Although the Winters doctrine originally was interpreted as applying to Indian reservations, it has since been applied to other federal land reservations, including water uses in national forests, national parks, national monuments, and other areas. As a result, federal agencies have in some cases asserted or negotiated reserved water rights in accordance with federally authorized purposes. For example, the National Park Service has a reserved water right for flows in the Gunnison River in Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park. In some cases, assertion of the reserved water rights by federal agencies has been controversial and has been denied by courts. Generally, the critical factor in determining reserved water rights has been the intent of Congress (either expressed or implied) that such rights be created. Among the many questions associated with federal lands and water rights are how limitations on these rights are applied under various circumstances and how federal management objectives are affected when water rights are held by federal agencies and others. Notes: For more information on the Winters doctrine, see CRS Report RL32198, Indian Reserved Water Rights Under the Winters Doctrine: An Overview, by [author name scrubbed]. |

Issues and Legislative Considerations

Some stakeholders previously have argued that language similar to that proposed under Title VII is necessary to protect private property rights from encroachment by the federal government.43 Others have raised concerns that the prohibitions contained in H.R. 23 are overly broad, internally inconsistent, and would introduce confusion into the current system of water rights and lead to litigation.44 In particular, some have noted that the directions under Sections 703 and 704 of the bill appear to be inconsistent with the definitions of water rights under Section 702 and the savings clauses under Section 705 of the bill. They question how these parts of the bill would be reconciled by federal agencies in practice and assert that the legislation, if enacted, could result in litigation and, perhaps, could affect established practices and approaches.

It is unclear how Title VII would affect federal reserved water rights if the bill were enacted in its current form. The bill contains multiple directives that appear in some cases to conflict with one another. For example, Section 705(d) of the bill states, "Nothing in this Act limits or expands any existing reserved water rights of the Federal Government on land administered by the Secretary." This statement could cause some to argue that major changes to the existing system of federal reserved water rights are not envisioned by the bill. Supporters of similar provisions have noted that they are not against the assertion of federal reserved water rights when those rights are specifically set out in statute or identified by courts. However, in previous testimony before Congress, Reclamation argued that the requirements of H.R. 23 have the potential to impact the ability of DOI agencies, such as the National Park Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service, to exercise water rights associated with their land reservations,45 including the agencies' ability to protect groundwater-dependent resources located on federal lands. Other witnesses have pointed out that under certain interpretations, the bill has the potential to render less likely the settlement of future Indian Water Rights claims, which in some cases necessitate the federal limitation of state-based rights for tribal water rights that are judged to be senior in status.46 It appears as though most new federal policies or actions related to reserved water rights would be subject to the bill's requirements, including its requirements for coordination with state laws and authorities. This requirement could lead to some future federal actions and policies attempting to assert reserved water rights being less likely to be implemented and potentially altered as a result of the legislation.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

The 17 Reclamation states designated in the Reclamation Act of 1902, as amended, are Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. 43 U.S.C. §391. |

| 2. |

Bureau of Reclamation, "About the Central Valley Project," at http://www.usbr.gov/mp/cvp/about-cvp.html. |

| 3. |

The previous four years have been classified by the Sacramento and San Joaquin River indexes as below normal (2012), dry (2013), and critically dry (2014 and 2015). In 2016, the Sacramento River Index was classified as below normal, whereas the San Joaquin Index was classified as dry. |

| 4. |

U.S. Drought Monitor, http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/MapsAndData/DataTables.aspx?state,CA. |

| 5. |

For a brief discussion of different aspects of post-drought conditions in California, see CRS Insight IN10684, California Drought: Busted?, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 6. |

The Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA, Title XXXIV of P.L. 102-575) was enacted in 1992 and mandated changes in the operation of the Central Valley Project (CVP) related to the protection, restoration, and enhancement of wildlife. For additional background, see Bureau of Reclamation, "Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA)," at https://www.usbr.gov/mp/cvpia/. |

| 7. |

The Central Valley Project Restoration Fund (CVPRF) is a fund established by the CVPIA that is financed by water and power users; fund balances are used for habitat restoration and enhancement and for water and land acquisitions. |

| 8. |

The exception is §113, related to the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement, which appears to be largely new provisions that have not previously been considered. |

| 9. |

Some stocks were already absent or in severe decline by 1992, including winter run Chinook salmon, which were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA; P.L. 93-205) in 1990. Some (such as San Joaquin River salmon runs) had become extinct by the 1950s. |

| 10. |

70 Stat 483. |

| 11. |

43 U.S.C. §485h-1. |

| 12. |

Pursuant to §3405(a)(2)(A) of CVPIA, decisions on water transfers must be approved within 90 days and must meet other requirements. |

| 13. |

These mitigation requirements are sometimes employed for transfers that have been determined to affect third parties. |

| 14. |

As discussed above, "reasonable water flows" is a new term added to the CVPRF under this legislation and is defined in §102(n) of H.R. 23 to mean "capable of being maintained taking into account competing consumptive uses of water and economic, environmental, and social factors." |

| 15. |

The 800,000 acre-feet of water under §3406(b)(2) of CVPIA that is dedicated and managed primarily for fish and wildlife purposes is often referred to as (b)(2) water. |

| 16. |

This water typically is reused—that is, once it is used (or even during use) for temperature control, habitat support, or other fish and wildlife purposes, the water can be "reused" by agricultural and municipal and industrial contractors—but reuse currently is not mandated under CVPIA. |

| 17. |

The Delta Division is a unit of the CVP that serves some water districts that often receive less water than under their full contract amount. |

| 18. |

As noted above, §105 of H.R. 23 also would deem "pursuit" of such actions as meeting the obligations to do so, which may trigger reduced payments. |

| 19. |

Contractual obligations are currently approximately 9.3 million acre-feet (maf) per year. Actual deliveries ranged from 4.9 maf in 2009 (a drought year) to 6.2 maf in 2011 over the last five years and are closer to 7 maf in normal hydrologic years. Thus, a gap exists between CVP contractual obligations and average or normal deliveries. |

| 20. |

The WIIN Act authorized federal funding for certain new water storage projects (at either a 50% or a 25% cost-share level, depending on the project type). It is unclear whether this authority would negate the use of any of that funding. |

| 21. |

The Bay-Delta Accord, previously in effect from 1994 to 1997, set varying maximum restrictions on water exports from the Delta depending on the time of year, guaranteed a reliable supply of water for the three main groups of stakeholders, ensured real-time monitoring of water levels, and promised to comply with all environmental regulations through restoration efforts. It has subsequently lapsed and has been replaced with other efforts. See Principles for Agreement on Bay-Delta Standards Between the State of California and the Federal Government, Washington, DC, December 15, 1994, at http://www.calwater.ca.gov/content/Documents/library/SFBayDeltaAgreement.pdf. |

| 22. |

It is unclear whether the language waiving the ESA also would waive the ESA provisions of the Bay-Delta Accord itself. |

| 23. |

The Sacramento Valley Index is a calculation of current-year unimpaired runoff and the previous year's index used to determine the type of water year for actions under the State Water Resources Control Board Water Rights Decision 1641. A classification of 6.5 or lower is considered a dry year, and 5.4 or lower is considered a critically dry year. |

| 24. |

Available estimates for total annual Friant Dam water supplies (including both contract and temporary water) are, on average, 15% to 16% less under the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement than under current operations; but such estimates do not account for improvements in water management that might reduce the impact on water users. For 75% of water contractors, the reduction would represent a reduction in one of their available sources of water. The impacts of such reductions vary by contractor, depending on the firmness of existing surface water supplies and the reliability of groundwater supplies. |

| 25. |

There has, however, been extensive discussion of the settlement itself, in the context of previous efforts to repeal it. |

| 26. |

The California WaterFix is the state of California's plan to upgrade its infrastructure in the Delta and increase water supply reliability and flows for species, while also improving natural hazard resiliency. For more information, see https://www.californiawaterfix.com/. |

| 27. |

This direction appears to conflict with that in §107(e), which also authorizes all of the Calfed Bay-Delta Authorization Act (P.L. 108-361) projects for construction with nonfederal funds but does so regardless of a positive feasibility study finding by the federal government. |

| 28. |

Statement of Michael L. Connor, Deputy Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior, Before the Energy and Natural Resources Committee U.S. Senate, S 1894, California Emergency Drought Relief Act of 2015, hearings, October 8, 2015, at https://www.energy.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/files/serve?File_id=fb299e7d-7de8-41c8-b8a2-365d544c8911. Hereinafter, "Connor, October 2015 Testimony." |

| 29. |

Connor, October 2015 Testimony. |

| 30. |

For a more detailed analysis of the language addressing area of origin, no redirected impacts, effects on allocations for Sacramento River watershed contractors, and effects on existing legal obligations, see CRS Report R43820, Analysis of H.R. 5781, California Emergency Drought Relief Act of 2014, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 31. |

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that §8 of the Reclamation Act of 1902 (43 U.S.C. §383) requires the Bureau of Reclamation to comply with state law in the "control, appropriation, use or distribution of water" by a federal project. See California v. United States, 438 U.S. 645, 674-75 (1978). This requirement to comply with state law applies so long as the conditions imposed by state law are "not inconsistent with clear congressional directives respecting the project." See Ibid. at 670-73. Under §8, the agency also is required to acquire water rights for its projects, such as for the CVP. In California, Reclamation found it necessary to enter into settlement or exchange contracts with senior water users who had rights predating the CVP and thus were senior water rights holders. Sacramento River Settlement Contractors are one such class; the San Joaquin Exchange Contractors are another. |

| 32. |

Connor, October 2015 Testimony. |

| 33. |

Provisions in Title V are largely similar to the Water Supply Permitting Coordination Act (H.R. 1654). Similar legislation has been the subject of hearings in prior congresses. |

| 34. |

The Secretary of the Interior also would be required to publish annually in the Federal Register a request for proposed new studies by nonfederal interests. |

| 35. |

For more information on this process, seeCRS Report R41243, Army Corps of Engineers: Water Resource Authorizations, Appropriations, and Activities, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 36. |

The provisions in Title VI are largely similar to those in H.R. 875, the Bureau of Reclamation Surface Water Storage Streamlining Act (H.R. 5412). Similar stand-alone legislation has been introduced in previous congresses. |

| 37. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Natural Resources, Western Water and American Food Security Act of 2015, committee print, 114th Cong., 1st sess., July 13, 2015. |

| 38. |

For a more detailed discussion of these provisions, see CRS Report R43298, Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014: Comparison of Select Provisions, by [author name scrubbed] et al. |

| 39. |

A discussion of each provision in Title VI is beyond the scope of this report. However, analysis of the comparable provisions in the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA 2014; P.L. 113-121) is provided in the "Expediting Studies, Environmental Reviews, and Permits" section of CRS Report R43298, Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014: Comparison of Select Provisions, by [author name scrubbed] et al. |

| 40. |

Letter from Michael L. Connor, Deputy Secretary of the Interior, to Honorable Rob Bishop, Chairman, House Committee on Natural Resources, July 7, 2015. |

| 41. |

Similar provisions also were proposed in legislation in the 114th Congress, including in Title XI of H.R. 2898, the Western Water and American Food Security Act of 2015. |

| 42. |