Background and Federal Efforts on Summer Youth Employment

Labor force activity for youth ages 16 to 24 has been in decline since the late 1990s. This trend has been consistent even during the summer months, when youth are most likely to be engaged in work. Labor force data from the month of July highlight changes in summer employment over time. For example, the employment rate—known as the employment to population (E/P) ratio—for youth was 64.1% in July 1996 and 53.2% in July 2016. Congress has long been concerned about ensuring that young people have productive pathways to adulthood, particularly for those youth who are low-income and have barriers to employment. One possible policy lever for improving youth employment prospects is providing jobs and supportive activities during the summer months.

Generally, cities and other local jurisdictions carry out summer employment programs in which youth are placed in jobs or are otherwise participating in activities to facilitate their eventual entry into the workforce. Summer employment may serve multiple policy goals, including supporting low-income youth and their families, encouraging youth to develop “soft skills” that can help them navigate their environments and work well with others, and deterring youth from activities that could lead to them getting in trouble or being harmed. Data are limited on the number of youth engaged in summer employment. A survey of 40 cities reported that nearly 116,000 youth had summer jobs in 2015. This represents a small portion of the approximately 20 million youth ages 16 to 24 in the U.S. labor force during the summer.

Localities fund summer employment activities with public and private dollars. Federal workforce laws since 1964 have authorized funding to local governments for their summer employment activities, primarily for low-income youth with barriers to employment; however, the laws’ provisions about summer employment have shifted over time. The existing federal workforce law, the Workforce Innovation and Opportunities Act (WIOA, P.L. 113-128), was enacted in 2014 and made summer employment an optional activity under the Youth Activities program. This program provides the major federal support for youth employment and job training activities throughout the United States. The Workforce Investment Act (WIA, P.L. 105-220) and other prior laws required localities to use Youth Activities funding for summer youth employment.

Other recent federal efforts have sought to bolster the summer employment prospects for young people. Under the Summer Jobs and Beyond grant, the Department of Labor provided $21 million in FY2016 for 11 communities to expand work opportunities for youth during the summer. The executive branch has also encouraged other federal programs, including the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, to provide employment to eligible youth during the summer. Separately, the Obama Administration forged partnerships with the private and nonprofit sectors to expand summer jobs. For example, the My Brother’s Keeper initiative has engaged the private sector in providing job and other opportunities for young men of color.

Summer youth employment is short in duration and can range in intensity for youth participants. Therefore, it may not necessarily lead to changes in behavior or employment outcomes. In considering whether to further support localities in expanding summer employment, Congress may want to examine the efficacy of existing summer employment programs and promising approaches to serving young people in these programs. A small number of rigorously evaluated summer job programs show promise on selected youth outcomes, including programs in Chicago and New York City. A recent study has identified features of high-quality summer employment programs. Such features include a focus on recruiting and supporting youth and employers, a well-trained staff that coordinates with employers and other partners, and technologies to administer the program and facilitate communication with stakeholders.

Background and Federal Efforts on Summer Youth Employment

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Youth in the Labor Force

- Overview of Summer Employment Programs

- Recent Federal Efforts

- Summer Opportunity Project

- Summer Jobs and Beyond: Career Pathways for Youth

- Coordinating Federal Programs

- Engaging Multiple Sectors

- Considerations for Congress

Figures

- Figure 1. Monthly Labor Force Trends for Youth Ages 16-24, July 1996-July 2016

- Figure 2. Common Features of Summer Employment Programs for Youth

- Figure A-1. Monthly Labor Force Trends for Youth Ages 16-19, July 1996-July 2016

- Figure A-2. Monthly Labor Force Trends for Youth Ages 20-24, July 1996-July 2016

Tables

Summary

Labor force activity for youth ages 16 to 24 has been in decline since the late 1990s. This trend has been consistent even during the summer months, when youth are most likely to be engaged in work. Labor force data from the month of July highlight changes in summer employment over time. For example, the employment rate—known as the employment to population (E/P) ratio—for youth was 64.1% in July 1996 and 53.2% in July 2016. Congress has long been concerned about ensuring that young people have productive pathways to adulthood, particularly for those youth who are low-income and have barriers to employment. One possible policy lever for improving youth employment prospects is providing jobs and supportive activities during the summer months.

Generally, cities and other local jurisdictions carry out summer employment programs in which youth are placed in jobs or are otherwise participating in activities to facilitate their eventual entry into the workforce. Summer employment may serve multiple policy goals, including supporting low-income youth and their families, encouraging youth to develop "soft skills" that can help them navigate their environments and work well with others, and deterring youth from activities that could lead to them getting in trouble or being harmed. Data are limited on the number of youth engaged in summer employment. A survey of 40 cities reported that nearly 116,000 youth had summer jobs in 2015. This represents a small portion of the approximately 20 million youth ages 16 to 24 in the U.S. labor force during the summer.

Localities fund summer employment activities with public and private dollars. Federal workforce laws since 1964 have authorized funding to local governments for their summer employment activities, primarily for low-income youth with barriers to employment; however, the laws' provisions about summer employment have shifted over time. The existing federal workforce law, the Workforce Innovation and Opportunities Act (WIOA, P.L. 113-128), was enacted in 2014 and made summer employment an optional activity under the Youth Activities program. This program provides the major federal support for youth employment and job training activities throughout the United States. The Workforce Investment Act (WIA, P.L. 105-220) and other prior laws required localities to use Youth Activities funding for summer youth employment.

Other recent federal efforts have sought to bolster the summer employment prospects for young people. Under the Summer Jobs and Beyond grant, the Department of Labor provided $21 million in FY2016 for 11 communities to expand work opportunities for youth during the summer. The executive branch has also encouraged other federal programs, including the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, to provide employment to eligible youth during the summer. Separately, the Obama Administration forged partnerships with the private and nonprofit sectors to expand summer jobs. For example, the My Brother's Keeper initiative has engaged the private sector in providing job and other opportunities for young men of color.

Summer youth employment is short in duration and can range in intensity for youth participants. Therefore, it may not necessarily lead to changes in behavior or employment outcomes. In considering whether to further support localities in expanding summer employment, Congress may want to examine the efficacy of existing summer employment programs and promising approaches to serving young people in these programs. A small number of rigorously evaluated summer job programs show promise on selected youth outcomes, including programs in Chicago and New York City. A recent study has identified features of high-quality summer employment programs. Such features include a focus on recruiting and supporting youth and employers, a well-trained staff that coordinates with employers and other partners, and technologies to administer the program and facilitate communication with stakeholders.

Introduction

Over the past several years youth have experienced a dramatic decline in employment. This includes during the summer months, when youth labor force activity tends to be higher than other times of the year.1 One potential policy option for addressing youth employment is providing support for summer job programs, which are generally administered by cities with funding from both the public and private sectors. Though information on these programs is limited, they appear to serve a very small number of youth who are in the labor force. The intent of summer employment is to provide income to youth and potentially meet broader goals, such as developing the professional and social skills youth need to succeed in the workplace. The current federal workforce law, the Workforce Innovation and Opportunities Act (WIOA, P.L. 113-128), was enacted in 2014 and shifted summer employment from being an optional to a mandatory activity under the Youth Activities program. This program provides funding to localities across the United States for youth job training and employment activities. Other recent federal programs and initiatives have sought to expand employment opportunities for youth during the summer months.

This report provides information about summer youth employment, including for those youth who are low-income and face challenges with securing employment. It starts by examining trends in employment among young people. It then describes how cities and other localities operate summer job programs, as well as recent federal programs and initiatives to fund these local efforts.2 The report concludes with considerations for Congress about the federal role in supporting summer employment.

For purposes of this report, youth refers to individuals ages 14 through 24 except in reference to workforce data (which is collected on individuals ages 16 or older who are in the labor force). Individuals as young as 14 are included because the Youth Activities program begins serving youth at this age. Older youth, up to age 24, are included because they are often still in school and/or living with their parents. The Youth Activities program also serves youth up to this age.

Youth in the Labor Force3

Federal data on employment are collected in a survey each month by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and include individuals ages 16 or older in the civilian, noninstitutionalized population. These data can be used to assess the extent to which youth are participating in labor market activity (i.e., employed or looking for work). The youth labor force participation rate (LFPR) is the share of the youth population (16 to 24 year old individuals) that is either employed or actively looking for work (i.e., unemployed).4 The youth employment-to-population (E/P) ratio is the proportion of the youth population that is employed. The youth unemployment rate is the share of youth in the labor force (i.e., the sum of employed and unemployed youth) who are unemployed. Together, these indicators help to gauge labor market conditions for young workers. Data for July are used in this report to represent labor force trends during the summer.

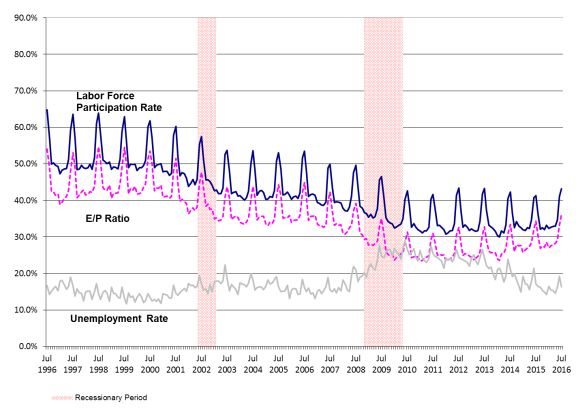

In July 2016, approximately 38 million individuals in the civilian, noninstitutionalized U.S. population were ages 16 to 24. Of these youth, slightly more than half (approximately 20 million) were in the labor force.5 Figure 1 includes monthly labor force participation rates, E/P ratios, and unemployment rates for youth ages 16 to 24 from July 1996 through July 2016. The figure shows the following:

- Youth labor force activity increased during the summer months within each year, with the LFPR and E/P ratio peaking in July of most years.

- Youth labor force participation and the youth E/P ratio have declined since the late 1990s.6 For example, the LFPR was 73.3% in July 1996 and 53.2% in July 2016. The E/P ratio was 64.1% in July 1996 and 53.2% in July 2016.

- The youth LFPR and E/P ratio declined markedly following the recessions of 2001 and December 2007 to June 2009. The LFPR and E/P ratio did not fully recover following the 2007-to-2009 recession, but the E/P ratio showed some improvement. Neither indicator recovered to pre-2000 rates.

- Rates of unemployment were similar in July 1996 (12.6%) and July 2016 (11.5%). The intervening years show a slight upward trend, most notably following the recession of 2011 and during and following the recession of 2007 to 2009. The unemployment rate remained elevated following the most recent recession until approximately 2013.7

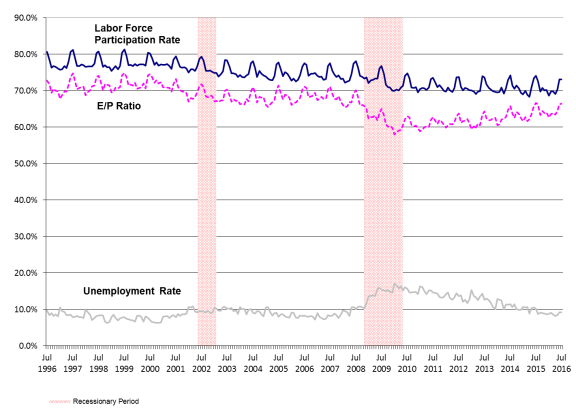

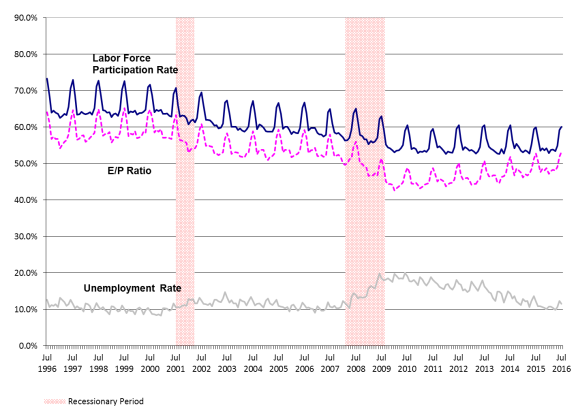

Figure A-1 and Figure A-2 in Appendix A break out monthly labor trend data for teenagers ages 16 to 19 and young adults ages 20 to 24, respectively, from July 1996 through July 2016. They show that teens experienced striking declines in their labor force participation (a decline of 33.3%, from 64.8% to 43.2%) and E/P ratio (a decline of 33.1%, from 54.0% to 36.1%) over this time period. Labor force indicators for young adults experienced downward, but less precipitous, trends. The labor force participation rate for young adults decreased from 80.6% to 73.1% (a decline of about 9%) and their E/P ratio declined from 72.8% to 66.4% (a decline of about 9%). Unemployment rates for the two groups were roughly the same in both July 1996 and July 2016: about 16% for teens and 9% for young adults.8

|

Figure 1. Monthly Labor Force Trends for Youth Ages 16-24, July 1996-July 2016 Not seasonally adjusted |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), based on data from U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics (Current Population Survey – CPS), at http://www.bls.gov/cps/. Recession data are from the National Bureau of Economic Analysis, at http://www.nber.org/cycles.html. Notes: The labor force participation rate is the percentage of individuals in the population who are employed or unemployed and looking for work (those who are not employed and not looking for work are excluded from the labor force). Employment-to-population ratios represent the percentage of the population that is employed. The unemployment rate is the percentage of individuals in the labor force who are jobless, actively looking for jobs, and available for work. All indicators shown describe individuals in the civilian, noninstitutionalized population who are 16 to 24 years old. |

The research literature has not fully explored the labor force participation of low-income youth during the summer. One analysis found that the summer employment rate of teens ages 16 through 19 increases with household income. In the summer months of 2013 and 2014, about one out of every five teens with family incomes below $20,000 were employed. This is compared to about 28% of teens with household incomes of $20,000 to $39,000; and 32% to 41% of teens in households with higher incomes.9

Overview of Summer Employment Programs

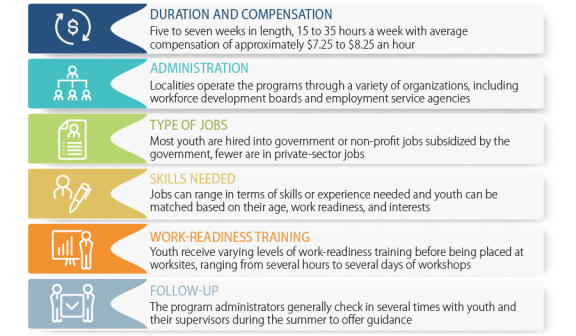

Summer job programs are generally run at the city or county levels with public and private funding. These programs offer employment experiences and other activities for young people who are usually between the ages of 14 and 24. Activities can include exploring career options, project-based learning whereby youth learn about work through in-depth study, simulated work environments, training in employment skills, mentoring and assistance in finding unsubsidized positions, and internships.10 There is not a census of youth who are employed in summer jobs. A survey of 40 cities found that nearly 116,000 youth were placed in such jobs in 2015.11 Figure 2 shows common characteristics of youth summer employment programs. Generally, these programs are targeted to young people in high school and some older youth who have little job experience and may lack strong family or community connections.

Given concerns about youth employment rates, mayors and other municipal leaders have recently taken steps to expand summer employment programs.12 There is scant information about how localities fund their summer employment programs. They likely use a combination of funding from public (federal, state, and local) and private (foundations and businesses) sources. Private sector support encompasses both funding to cities to expand summer youth initiatives and providing job placements for youth. For example, the Boston Private Industry Council, the city's workforce development board, secured more than 2,600 unsubsidized jobs from local employers in the summer of 2015.13 Businesses like JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Citi have provided financial support to multiple cities for summer jobs and created work placement programs for low-income youth across their various business locations.14 Further, there is little information about the cost of operating these programs, though cities report that the largest share of the programs' budgets are for subsidized wages.15 The typical cost per participant is approximately $1,400 to $2,000.

Summer employment programs are generally intended to serve young people and their families, and potentially meet broader objectives. The rationale for these programs may include the following:

- providing income to youth and their families;16

- encouraging youth to develop "soft skills" and professional skills that can help them navigate their environments and work well with others;17

- improving the academic outcomes and prospects for employment of youth in the future;

- deterring youth from activities that could lead to them getting in trouble or being harmed; and

- providing greater economic opportunities to youth in areas with few employment prospects.

Recent Federal Efforts

Federal workforce laws since 1964 have included summer job training and employment activities. These laws have targeted such activities to low-income and other vulnerable youth. Over time, summer employment has gone from a stand-alone program under the Job Training Partnership Act (JTPA, P.L. 97-300), enacted from 1982 to 1998; to a required activity under the Workforce Investment Act (WIA, P.L. 105-220), enacted from 1998 to 2014; and then to an optional activity under WIOA, enacted in 2014 and effective as of July 1, 2015.18 WIOA authorizes the Youth Activities program, the major federal workforce program for youth. The program received FY2016 appropriations of $873 million. Funding under the program is allocated to states based on relative income and employment factors. States then allocate funds to localities, through what are known as local workforce development boards (governmental entities that administer local workforce development funds), based on similar factors. Localities are to provide education and employment activities to youth who have barriers to employment, and at least three-quarters of participants must be out of school. As noted, summer employment is an allowable, but not required, activity under the program.19 Data are not yet available on the number of youth who have participated in summer employment under WIOA.

The Workforce Investment Act (WIA, P.L. 105-220) preceded WIOA, and directed local areas to offer summer employment activities to low-income youth via the Youth Activities program.20 Approximately 18,000 to 20,000 eligible youth annually participated in summer employment activities under the WIA Youth Activities program in recent years.21 The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5, ARRA, or Recovery Act), which was enacted to bolster the economy during the 2007-2009 recession, had a focus on summer employment. In the accompanying conference report for the law, Congress specified that the $1.2 billion in ARRA funds for the WIA Youth Activities program should be used for both summer youth employment and year-round employment opportunities, particularly for youth up to age 24.22 Approximately 40% of ARRA dollars for the Youth Activities program was used for employment during the summer months, and a total of 374,489 youth participated in summer employment opportunities.23

In light of changes to workforce law with regard to summer employment opportunities, recent federal initiatives have sought to bolster the summer employment prospects for young people, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Recent Federal Efforts to Expand Summer Employment Opportunities

Funding information provided where applicable

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS).

Summer Opportunity Project

The Obama Administration's Summer Opportunity Project, launched in February 2016, worked with states, localities, and other stakeholders in providing youth with employment, academic opportunities, and supportive services during the summer months. The Administration and its partners developed the Summer Opportunity Resource Guide to help communities navigate federal resources and supports in each of these three areas.24 Further, the Administration provided on-the-ground support to 16 communities under the "summer impact hubs" initiative to help disadvantaged youth connect to school and work and receive supportive services. In each of these communities, a federal representative helped to coordinate partnerships and leverage federal funds.25 The Summer Opportunity Project also included assistance from the private sector. For example, the online professional networking service LinkedIn worked to connect businesses with local and state organizations to help young people, including disadvantaged youth, in accessing summer jobs in 72 cities.26

Summer Jobs and Beyond: Career Pathways for Youth

As part of the Summer Opportunity Project, DOL provided $21 million in FY2016 appropriations for the Summer Jobs and Beyond initiative. The initiative supports 11 communities in developing and expanding work opportunities for youth during the summer.27 The initiative is authorized under the FY2016 appropriations law (P.L. 114-113, Division H), which specified that appropriations for Section 168(b) and Section 169(c) of WIOA can be used to provide technical assistance and demonstration projects, respectively, for new entrants in the workforce and incumbent workers (i.e., workers already employed). DOL interprets "new entrants" to include youth ages 16 to 24 who are in or out of school and have never participated in the workforce or have limited work experience.28 According to DOL, the Summer Jobs and Beyond grants are intended to support local workforce development boards (WDBs, which administer workforce programs in communities) in expanding existing summer employment programs and year-round work experience and implementing innovative practices. The grants require WDBs to partner with local summer employment programs (including those already operated by the WDB); employers; local education agencies; and re-engagement centers, where they exist.29 DOL intends for the grants to help inform how

- best to serve in-school youth given the limited funding for this population under WIOA;30

- grant partners can more effectively reach out-of-school youth and assist them in transitioning to positions that extend beyond the summer months; and

- to leverage multiple funding streams (e.g., TANF) in serving youth and improve performance outcomes in high-crime, high-poverty communities that offer limited economic mobility for youth.

The 11 communities that received Summer Jobs and Beyond funding are pursuing projects that include providing in-school youth who are refugees with summer jobs and academic support; providing courses and summer jobs in health care, information technology (IT), and manufacturing and infrastructure; and providing employment-related services to eligible Native American youth with limited work experience, among other activities. Grantees will be evaluated based on the share of program participants who, during the course of the program year, are in an education or training program that leads to a recognized postsecondary credential or employment and who are achieving measurable skill gains toward such a credential or employment.31

Summer Jobs and Beyond builds upon DOL's Urban Youth Employment Demonstration Grants, which provided $22.5 million from FY2014 appropriations for seven communities facing high poverty and high unemployment to connect youth and young adults (ages 16 to 29) with job opportunities both during the summer and year-round.32 These grants involve partnerships between cities and community and faith-based organizations, educational institutions, foundations, and employers.33 They are designed to help prepare young people for work in health care and other growing industries. They also support services, including financial literacy, apprenticeship training, leadership development, and mental health/substance abuse counseling.

Coordinating Federal Programs

In recent years, the executive branch has sought to expand summer employment opportunities by coordinating DOL youth workforce programs with other federal programs. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) administers TANF, which funds a wide range of benefits and services for low-income families with children. Beginning with the enactment of ARRA in February 2009, HHS has encouraged states to use TANF funding to expand summer employment opportunities for eligible low-income youth. ARRA created a $5 billion Emergency Contingency Fund (ECF) within TANF to provide states, territories, and tribes with additional financial aid during the economic downturn under selected categories of TANF spending.34 HHS and DOL issued a joint letter in January 2010 to encourage states to use the ECF for subsidized youth employment.35 Over the two-year period that ECF funds were available, 24 states and the District of Columbia used these funds to operate summer employment programs targeted to over 138,000 youth.36 A study of 10 local sites that expanded summer employment programs via the ECF found that state and local workforce and TANF agencies built new partnerships or expanded existing ones to serve youth. The programs were primarily operated by local workforce boards (now known as workforce development boards), with support from the local TANF offices.37

HHS and DOL have since encouraged states, territories, and tribes to use TANF funds to support their summer efforts through other joint letters, technical assistance, and webinars.38 In a 2013 joint letter, HHS and DOL noted that "it is critically important for state and local TANF agencies to work with WIBs to explore ways to combine resources in developing or expanding subsidized employment programs and related supportive services [for low-income youth]."39

The executive branch has further encouraged coordination of summer employment efforts through two programs administered by HHS (the Community Services Block Grants [CSBG] and the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program [CFCIP]) and public housing dollars administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).40 CSBG provide federal funds to states, territories, and tribes for distribution to local agencies to support a wide range of community-based activities to reduce poverty.41 HHS has encouraged local and state CSBG offices to engage local CSBG-funded entities in securing government-sponsored and private sector summer jobs for low-income youth. Further, HHS has noted that CSBG entities may support employment opportunities directly or offer additional supports (e.g., mentoring, financial education) for youth in TANF and applicable federal workforce programs.

The CFCIP delivers funding to child welfare agencies to provide services and supports for older youth in foster care and those who have recently emancipated from foster care.42 The Administration has encouraged partnerships between workforce programs and child welfare agencies as a possible way to mitigate poor employment and education outcomes for foster youth. In this same vein, the Administration has encouraged local housing authorities, which receive federal funding for public housing assistance, to work alongside youth service and workforce programs to develop summer job opportunities for low-income youth.

Engaging Multiple Sectors

Beyond using federal programs to expand summer employment opportunities, the executive branch has created partnerships with the private, nonprofit, and other sectors for this purpose. In 2012 and 2013, the Summer Jobs+ and Youth Jobs+ initiatives engaged partners—elected officials, local businesses, nonprofit organizations, and faith institutions—to help provide employment opportunities for young people. As part of the Summer Jobs+ initiative in summer 2012, the Obama Administration encouraged public and private sector entities across the country to provide a total of more than 300,000 summer job opportunities, including more than 100,000 paid positions.43 The initiative included the Summer Jobs+ bank, an online search tool for youth to access postings from participating employees.44 The Youth Jobs + initiative followed in 2013, with the Administration reaching out to engage these same stakeholders to provide paid positions, life-skills training, and work skills for youth.45

In February 2014, President Obama established the My Brother's Keeper Task Force (MBK Task Force) to assess the public and private efforts that are needed to enhance positive outcomes for boys and young men of color. The MBK Task Force was formed with representatives from various federal agencies that have programs and activities to support vulnerable youth. In a June 2014 report, the MBK Task Force developed a set of recommendations that identify roles for government, business, nonprofit, philanthropic, and other partners. The recommendations focused on ensuring that young men of color are ready for school, achieve in school, complete post-secondary education or training, and successfully enter the workforce. One of the recommendations was to strengthen evidence on summer employment as an intervention for young men of color and other vulnerable youth. In its April 2016 follow-up report, the MBK Task Force described selected federal and other initiatives aimed at improving the educational and employment outcomes for young men of color under the auspices of the MBK initiative.46 For example, MBK efforts in Detroit seek to provide 15,000 new summer jobs over the next 10 years.

Considerations for Congress

In considering whether to further support localities in their efforts to expand summer employment, Congress may want to examine the efficacy of summer employment programs and promising approaches to serving young people in these programs. As shown in Figure 2, summer employment programs are short-term interventions that vary in their intensity and support for youth. Thus, summer jobs may not necessarily lead to changes in behavior or may have unintended consequences. For example, youth may stay out of trouble during working hours but engage in criminal behavior in the evenings or on weekends.47

The research literature on the effectiveness of summer employment programs is limited. Some studies have examined the experiences of youth in the programs and whether youth showed improvements over the summer and beyond.48 DOL conducted studies on how youth engaged in summer employment funded under ARRA in summer 2009.49 Approximately three-quarters (76%) of youth demonstrated work readiness skills after participating, but the study did not determine impacts on youth. Further, few studies have been conducted that involve youth randomly assigned to summer employment programs.50 Rigorous evaluations of federally funded summer employment programs that operated in communities from the 1960s through the 1980s found that some had short-term impacts for selected outcomes; however, they did not have impacts on most outcomes over the long term, or failed to overcome methodological challenges.51 More recent research shows that selected summer employment programs are showing promising results.52 Evaluations of the One Summer Plus (OSP) program in Chicago and the Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP) in New York City indicate that summer jobs can reduce violent crime committed by youth participants, reduce the probability of incarceration or death, or improve academic outcomes. The results of the evaluations are summarized in Table B-1.53

According to a 2016 study by the Brookings Institution, there are multiple challenges to developing and expanding summer employment programs for youth.54 A major obstacle is funding, both the level of funding needed to operate a program and the uncertainty of when and how much local and state funding will be available. Municipal and other program leaders often do not have a budget until the spring, when a program is well underway. In addition, program staff must take on many tasks simultaneously, including recruiting participants and employers, matching youth with worksites, and monitoring implementation of the program. Some summer programs do not have adequate levels of employees to take on tasks such as matching youth to appropriate worksites and preparing supervisors for their roles. In addition, some summer programs are not able to reach or assist the most vulnerable youth who have additional barriers to work such as unstable housing.

Nonetheless, the 2016 study identifies promising features for achieving successful summer employment programs: program design, and capacity and infrastructure. Program design encompasses many elements, including (1) recruiting employers and worksites to provide the maximum number of job opportunities; (2) matching young people with opportunities that are well aligned with their abilities and skills; (3) preparing young people to succeed with professional training and financial literacy skills; (4) supporting youth and supervisors, such as having staff that provide coaching at the worksite; and (5) ensuring that youth connect to other opportunities in the community, such as year-round employment and programs to prepare youth for employment the following summer. Capacity and infrastructure includes ensuring a level of staff sufficient to carry out high-quality programming, and technology systems that can facilitate better program file and records management, communication with young people, and payroll automation. Promising programs have also developed tools, like guidebooks, that consolidate information about the program for program staff, youth, and workplace supervisors.

Appendix A. Monthly Labor Force Trends for Youth

Appendix B. Recent Evaluations of Summer Job Programs for Youth

Table B-1. Evaluations of One Summer Plus (OSP) in Chicago and Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP) in New York City

|

One Summer Plus (OSP) |

Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP) in New York City |

|

|

Program |

Youth ages 14 to 24 work 25 hours a week for 8 weeks during the summer and earn $8.25/hour. Local community organizations place youth in nonprofit and government jobs (e.g., summer camp counselors, workers in a community garden). Youth are assigned job mentors, adults who help them learn to be successful employees and to navigate barriers to employment. Ten youth are assigned to each adult mentor. |

Youth ages 14 to 24 work up to 25 hours a week for 6 to 7 weeks during the summer and earn $8.75/hour. In addition, 10% of participant hours are dedicated to education and training on topics related to time management, financial literacy, workplace readiness and etiquette, and career planning and finding employment. The most common placements are summer camps and day care, followed by social or community service agencies and retail establishments. |

|

Evaluations |

Approximately 1,600 youth applicants in grades 8 to 12 who were enrolled in 13 high-violence Chicago schools were randomly assigned to the OSP or to a control group in summer 2012. Some of the youth assigned to the program were offered 25 hours a week of paid employment. The other youth in the program were assigned to 15 hours of paid work and 10 hours of social-emotional learning (SEL) aimed at teaching youth to understand and manage aspects of their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that might interfere with employment. |

Three studies examined outcomes for youth who applied to SYEP in 2005-2008 or 2007 alone. For each study, the number of participants ranged from approximately 36,500 to 195,000 youth. For one of the two 2005-2008 studies and the 2007 study, the focus was on youth in high school. SYEP receives more applications than the number of SYEP jobs available, and uses a lottery system to assign youth to the program. Youth selected to the program were in the treatment group and those not selected were in the control group. |

|

Outcomes |

The study examined arrest and education records in the 16 months during and following the summer of 2012. Arrest records were examined for violent, property, drug, and other crimes. Arrests for violent crime decreased by 43% relative to the control group. Participation in OSP most significantly reduced the probability for violent crimes in the latter 13 months. There were no significant changes in other types of arrests, or on the days present at school or other academic outcomes during the following school year. There were also no significant differences in arrest rates between youth who received jobs only and those who received jobs plus the SEL training. |

The 2007 study found that youth selected for the SYEP increased school attendance by 1% to 2% in the following two semesters (this was higher for students age 16 or older with previous low attendance), and were more likely to attempt and pass the statewide examinations. One of the 2005-2008 studies found that SYEP increased the number of statewide exams students attempted and passed, and the average scores achieved. These outcomes improved for students who were selected to participate in the SYEP in two or three summers. The other 2005-2008 study found that earnings increased by nearly $900 and raised the probability of having any job in the year of the program, and the probability of incarceration or death was reduced (both mostly driven by a decrease among males). Youth employment did not have a positive effect on subsequent earnings or college enrollment. |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), based on Sara B. Heller, "Summer Jobs Reduce Violence Among Disadvantaged Youth," Science, vol. 346, no. 6214 (December 5, 2014); Jacob Leos-Urbel, "What is a Summer Job Worth? The Impact of Summer Youth Employment on Academic Outcomes," Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, vol. 33, no. 4 (2014); Alexander Gelber, Adam Isen, and Judd B. Kessler, The Effects of Youth Employment: Evidence From New York City Summer Youth Employment Program Lotteries, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 20810, 2015; and Amy Ellen Schwartz, Jacob Leos-Urbel, and Matthew Wiswall, Making Summer Matter: The Impact of Youth Employment on Academic Performance, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 21470, August 2015.

Notes: The Department of Labor (DOL) has contracted with MDRC, a social policy research organization, to provide further analysis of the SYEP. Results are forthcoming.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Department of Labor (DOL), Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Employment and Unemployment Among Youth – Summer 2016, news release, August 17, 2016. |

| 2. |

This report follows up on archived CRS Report R40830, Vulnerable Youth: Federal Policies on Summer Job Training and Employment, which describes efforts to provide summer employment to youth during the December 2007 through June 2009 recession, related issues, and the research literature on summer employment from the 1970s to 2011. |

| 3. |

For further background on annual youth employment data and trend data, see CRS Report R42519, Youth and the Labor Force: Background and Trends; and Martha Ross and Nicole Prchal Svajlenka, Worrying Declines in Teen and Young Adult Employment, Brookings Institution, December 16, 2015. |

| 4. |

BLS counts individuals as employed if they work at all for pay or profit during the week that they are surveyed. This encompasses all part-time and temporary work, as well as regular full-time, year-round employment. It does not include unpaid internships. Individuals are considered unemployed if they are jobless, actively looking for jobs, and available for work. Job search activities include sending out resumes or filling out applications, among certain other activities. |

| 5. |

DOL, BLS, Labor Force Statistics (Current Population Survey – CPS), at http://www.bls.gov/cps/. |

| 6. |

The decrease in the LFPR and E/P ratio is likely due to overall economic conditions and a greater share of youth attending school, particularly among those ages 16 to 19. Maria E. Canon, Marianna Kudlyak, and Yang Liu, Youth Labor Force Participation Continues to Fall, but It Might Be for a Good Reason, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, The Regional Economist, January 2015. School attendance for youth ages 16 to 24 without a high school diploma increased from 38.0% in 1998 to 60.0% in 2014. |

| 7. |

These trends do not indicate the quality of jobs held by youth, such as whether they are full-time or part-time or the sector in which youth tend to work. |

| 8. |

Though not shown in this report, minority youth ages 16 to 24 generally were less likely than their white counterparts to be in the labor force over the period from July 1996 to July 2016, had a lower E/P ratio, and had a higher rate of unemployment. For further information about these trends generally, see CRS Report R42519, Youth and the Labor Force: Background and Trends. |

| 9. |

Neeta Fogg, Paul Harrington, and Ishwar Khatiwada, The Summer Jobs Outlook for Teens in the U.S., Drexel University, Center for Labor Markets and Policy, May 8, 2015, pp. 8-10. A similar analysis found that family income (along with other factors) had a statistically significant effect on the probability of youth employment. See Andrew Sum et al., The Plummeting Labor Market Fortunes of Teens and Young Adults, Brookings Institution, March 2014. |

| 10. |

Martha Ross and Richard Kazis, Youth Summer Job Programs: Aligning Ends and Means, Brookings Institution, Metropolitan Policy Program, July 2016. (Hereinafter, Martha Ross and Richard Kazis, Youth Summer Job Programs: Aligning Ends and Means.) |

| 11. |

The United States Conference of Mayors and Bank of America, Financial Education & Summer Youth Programs, 2016. These cities have populations of 30,000 or more. Given that there are approximately 1,300 cities of this size and smaller jurisdictions were not included in the survey, this is an undercount of the number of youth in summer jobs. According to BLS data, there were approximately 23 million youth ages 16 to 24 in the labor force and approximately 20 million youth employed in July 2016. |

| 12. |

Martha Ross and Richard Kazis, Youth Summer Job Programs: Aligning Ends and Means, pp. 20-21. |

| 13. |

Ibid. |

| 14. |

JP Morgan Chase & Co., Building Skills through Summer Jobs: Lessons From the Field, January 2015; Bank of America, "Bank of America Announces $40 Million Commitment to Support Youth Success," February 2016, http://newsroom.bankofamerica.com/press-releases/corporate-philanthropy/bank-america-announces-40-million-commitment-support-youth-suc; and Citi Foundation, "Pathways to Progress," http://www.citigroup.com/citi/foundation/programs/pathways-to-progress.htm. |

| 15. |

Martha Ross and Richard Kazis, Youth Summer Job Programs: Aligning Ends and Means, p. 7. Subsidized employment refers to payments to employers or third parties to help cover the costs of employee wages. |

| 16. |

A child's earnings are never included in the earnings of their parents when they file their taxes. Wages from summer jobs may help to offset some of the costs of caring for youth, such as clothing and incidentals. |

| 17. |

According to the research literature, soft skills are competencies, behaviors, attitudes, and personal qualities that enable youth to navigate their environment, work with others, perform well, and achieve their goals. Laura H. Lippman et al., Key "Soft Skills" that Foster Youth Workforce Success: Toward a Consensus Across Fields, Child Trends, June 2014, p. 5. |

| 18. |

CRS Report R40929, Vulnerable Youth: Employment and Job Training Programs. |

| 19. |

The law includes 14 activities that are to be provided under the Youth Activities program, including paid and unpaid work experiences that have academic and occupational education as a component. Summer employment (and other employment opportunities throughout the school year) is one of four optional types of paid and unpaid work experience. The other three optional types are pre-apprenticeship programs, internships and job shadowing, and on-the job-skills training. |

| 20. |

The WIA Youth Activities program required communities to provide "summer employment opportunities that are directly linked to academic and occupational learning." |

| 21. |

Social Policy Research Associates, PY 2014 WIASRD Data Book, Table IV-14, revised January 19, 2016. Data are based on youth who exited the program within a specified period of time (e.g., July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015). |

| 22. |

U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Making Supplemental Appropriations for Job Preservation and Creation, Infrastructure Investment, Energy Efficiency and Science, Assistance to the Unemployed, and State and Local Fiscal Stabilization, for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2009, and For Other Purposes, 111th Cong., 1st sess., H.Rept. 111-16, February 12, 2009. |

| 23. |

For further information, see CRS Report R40830, Vulnerable Youth: Federal Policies on Summer Job Training and Employment. |

| 24. |

National Summer Learning Association et al., Summer Opportunities: Expanding Access to Summer Learning, Jobs and Meals for America's Young People, 2016. |

| 25. |

The White House (Obama Administration), "Fact Sheet: White House and Department of Labor Announce $21 Million for Summer and Year-Round Jobs for Young Americans and Launch of 16 Summer Impact Hubs" press release, May 16, 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/05/16/fact-sheet-white-house-and-department-labor-announce-21-million-summer. The 16 summer impact hubs included Jonesboro and Pine Bluff; AR; Los Angeles, CA; Washington, DC, Gary and Indianapolis, IN; New Orleans, LA; Baltimore, MD; Detroit and Flint, MI; St. Louis, MO; Clarksdale, MS; Newark, NJ; Pine Ridge, SD; Memphis, TN; and Houston, TX. |

| 26. |

The White House (Obama Administration), "Fact Sheet: White House Announces New Summer Opportunity Project," press release, February 25, 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/25/fact-sheet-white-house-announces-new-summer-opportunity-project-0. |

| 27. |

The communities include Santa Maria, CA; Hartford, CT; Chicago, IL; Detroit, MI; Utica, NY; Portland, OR; Philadelphia, PA; Milwaukee, WI; the Franklin Hampshire region of MA; and tribal communities in California, Illinois, and Iowa. |

| 28. |

U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Notice of Availability of Funds and Funding Opportunity Announcement for Summer Jobs and Beyond: Career Pathways for Youth, FOA-ETA-16-08. Section 168(b) permits DOL to use up to 5% of funds available under the Dislocated Worker program for technical assistance to states (and local areas and other entities involved in assisting dislocated workers) that do not meet the state performance accountability measures for dislocated workers. Section 169(c) permits DOL to use up to 10% of funds available under the Dislocated Worker program for demonstration and pilot projects (and multiservice and multistate projects) relating to the employment and training needs of dislocated workers. An individual is eligible for the services under the Dislocated Worker program if the person has been terminated or laid off, or has been notified of a termination or layoff; is sufficiently attached to the workforce but is not eligible for unemployment compensation; or is unlikely to return to the previous industry or occupation. Beginning at least with FY2001, appropriation laws have included provisions that allow dislocated worker funds (then from the Workforce Investment Act) to be used for demonstration projects related to new entrants. |

| 29. |

Local education agencies are local school districts, and re-engagement centers are operated by school districts (and other entities) to assist youth who have dropped out of school in reconnecting to educational pathways. |

| 30. |

As mentioned, WIOA requires local areas (and states) to use no less than 75% of funds for serving out-of-school youth. This is compared to no less than 30% of funds for this population under WIA. |

| 31. |

This is one of the performance measures required for the WIOA Youth program, Job Corps program, and YouthBuild program. A program year extends from July 1 of one year through June 30 of the next year. |

| 32. |

The communities include Long Beach, CA; Baltimore, MD; Detroit, MI; Camden, NJ; North Charleston, SC; Houston, TX; and the state of Missouri. |

| 33. |

The White House (Obama Administration), My Brother's Keeper 2016 Progress Report, Two Years of Expanding Opportunity and Creating Pathways to Success, April 2016. The grant is authorized under the Dislocated Worker program demonstration and pilot projects, Section 169(c) of WIOA. |

| 34. |

The ECF paid for an 80% reimbursement of increased costs under the categories of basic assistance, short-term aid, or subsidized employment. States were able to use funding reallocated from other activities funded from the basic TANF block grant or maintenance of effort (MOE) monies to cover the remaining 20% of their costs. They could also count the value of in-kind, third party payments toward the 20%. For further information, see CRS Report R41078, The TANF Emergency Contingency Fund. |

| 35. |

Subsidized employment payments could help cover the costs of employee wages, benefits, supervision, and training in the private or public sector. Joint Letter on Subsidized Youth Employment from Carmen R. Nazario, Assistant Secretary, Administration for Children and Families (ACF), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; and Jane Oates, Assistant Secretary, Employment and Training Administration (ETA), U.S. Department of Labor; January 10, 2010. In general, youth were eligible under the ECF if they were children in needy families or parents of children in needy families. Although a needy family must include a "minor child," states could use a broader definition of child (e.g., youth up to the age of 24) for purposes of providing unsubsidized employment (or other services that did not count as cash assistance) under the ECF. HHS also indicated that a low-income youth could include those who do not live with a parent or caregiver and are not parents; however, states could not claim spending for such youth as part of their maintenance of effort (MOE). HHS, ACF, Office of Family Assistance, Q&A: The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (Recovery Act). |

| 36. |

LaDonna Pavetti, Liz Schott, and Elizabeth Lower-Basch, Creating Subsidized Employment Opportunities for Low-Income Parents: The Legacy of the TANF Emergency Fund, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Center on Law and Social Policy (CLASP), February 16, 2011. |

| 37. |

Linda Rosenberg et al., Using TANF Funds to Support Subsidized Youth Employment: The 2010 Summer Youth Employment Initiative, Mathematica Policy Research Inc., Final Report, July 29, 2011. |

| 38. |

HHS, "Supporting Summer Youth Work," June 8, 2016. |

| 39. |

Joint Letter on Subsidized Youth Employment from George H. Sheldon, Acting Assistant Secretary, ACF, HHS, and Jane Oates, Assistant Secretary, ETA, DOL, May 9, 2013. |

| 40. |

Joint Letter Encouraging Summer Youth Employment Efforts from Mark H. Greenberg, Acting Assistant Secretary, ACF, HHS; Mark Johnston, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Special Needs, HUD; and Eric M. Seleznow, Acting Assistant Secretary, ETA, DOL, April 3, 2014. (Hereinafter, Joint Letter Encouraging Summer Youth Employment Efforts.) |

| 41. |

For further information, see CRS Report RL32872, Community Services Block Grants (CSBG): Background and Funding. |

| 42. |

For further information, see CRS Report RL34499, Youth Transitioning from Foster Care: Background and Federal Programs. |

| 43. |

DOL, Secretary Hilda Solis, "Youth Employment Turning the Corner in 2012," press release, August 23, 2012; and White House conference call on the Summer Jobs+ Initiative, January 5, 2012. |

| 44. |

DOL, "Summer Jobs+ Bank BETA," https://webapps.dol.gov/summerjobs. |

| 45. |

The White House (Obama Administration), "Jobs & The Economy: Putting America Back to Work – Summer Opportunities," https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/economy/jobs/youthjobs; and Joint Letter Encouraging Summer Youth Employment Efforts. |

| 46. |

The White House (Obama Administration), My Brother's Keeper Task Force, Fact Sheet & Report: Opportunity for All: My Brother's Keeper Blueprint for Action, May 30, 2014, and My Brother's Keeper 2016 Progress Report. |

| 47. |

Sara B. Heller, "Summer Jobs Reduce Violence Among Disadvantaged Youth," Science, vol. 346, no. 6214 (December 5, 2014). |

| 48. |

See Richard W. Moore et al., Hire LA: Summer Youth Employment Program Evaluation Report 2014, Executive Summary, California State University, Northridge The College of Business and Economics, 2015. |

| 49. |

Jeanne Bellotti et al., Reinvesting in America's Youth: Lessons from the 2009 Recovery Act Summer Employment Initiative, Mathematica Policy Research, February 26, 2010. |

| 50. |

Random design evaluations assign individuals to two groups—an intervention group and a control group—using a random process (e.g., a lottery) to compare outcomes across these groups. Under ideal conditions, this can help to explain whether an intervention is effective. |

| 51. |

For further information about these earlier studies, see CRS Report R40830, Vulnerable Youth: Federal Policies on Summer Job Training and Employment. CRS identified a small number of other summer youth employment programs that followed the evaluations of the 1980s and preceded the more recent evaluations. See, for example, Wendy S. McClanahan, Cynthia L. Sipe, and Thomas J. Smith, Enriching Summer Work: An Evaluation of the Summer Career Exploration Program, Public/Private Ventures, August 2004. |

| 52. |

Emerging research on the summer employment program in Boston includes random assignment of participants. See Alicia Sasser Modestino and Trinh Nguyen, The Potential for Summer Youth Employment Programs to Reduce Inequality, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Community Development Issue Brief 3, June 2016. |

| 53. |

Notably, these studies did not examine outcomes related to employment. Further, the study findings may not be generalizable to other summer employment programs. DOL has contracted with MDRC, a research organization, to conduct further analysis of the SYEP, and results are forthcoming; DOL, Chief Evaluation Office, "Academic and Labor Market Impact Analysis of New York City's Summer Youth Employment Program." |

| 54. |

Martha Ross and Richard Kazis, Youth Summer Job Programs: Aligning Ends and Means. The findings are based on interviews with municipal and other leaders and a scan of relevant research. |