The Civil Defense Acquisition Workforce: Enhancing Recruitment Through Hiring Flexibilities

Policymakers and defense acquisition experts have asserted that improved recruitment for the defense acquisition workforce is a necessary component for comprehensive acquisition reform. To help rebuild the workforce and enhance recruitment, DOD has used several hiring flexibilities authorized by Congress, the President, and OPM in recent years. Hiring flexibilities are a suite of tools that are intended to simplify, and sometimes accelerate, the hiring process.

The impact of hiring flexibilities on recruitment and workforce quality, however, remains unclear. Congress may consider three high-level questions regarding hiring flexibilities for the workforce:

Are flexibilities effectively improving the workforce?

Are the current number and type of flexibilities appropriate?

What factors may impact effective use of flexibilities to improve the workforce?

Congress could consider several oversight options to help gauge and improve the effectiveness of flexibilities in improving the civilian defense acquisition workforce. Such options might help Congress determine whether flexibilities should be expanded or newly created, consolidated or removed, or otherwise restructured. Congress could direct DOD to

provide data on the use of all available flexibilities to fill the full range of civilian defense acquisition positions, including any barriers to producing such data;

establish proxy measures for effectiveness related to employee quality (such as employee timeliness in earning required certifications and retention and career progression rates) and recruitment (such as time to hire from the perspective of the candidate and job acceptance rates);

conduct a study that evaluates the effectiveness of flexibilities; and

improve the quality, clarity, and use of implementing guidance for flexibilities.

At least 38 hiring flexibilities are currently available for the civilian defense acquisition workforce. According to DOD, the following six flexibilities were used most frequently to fill external civilian acquisition positions between FY2008 and FY2014:

Direct-hire authority (DHA)

Expedited hiring authority (EHA) for certain civilian acquisition positions

Pathways Recent Graduates program

Pathways Internship program

Federal Career Intern Program

Delegated examining authority

The six flexibilities accounted for roughly 66% of total external civilian acquisition hires between FY2008 and FY2014 (i.e., hires from outside the government). Some of the flexibilities were available throughout the six-year period, while others were discontinued or established during that period. Potential factors affecting the use of flexibilities include their structure, clarity of implementing guidance, establishment of new flexibilities, staff knowledge of appropriate use, budgetary constraints, and efforts to balance hiring speed with equity.

The Civil Defense Acquisition Workforce: Enhancing Recruitment Through Hiring Flexibilities

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background on the Defense Acquisition Workforce

- Size of the Defense Acquisition Workforce

- What Hiring Flexibilities Are Applicable to the Civilian Defense Acquisition Workforce?

- Background on Hiring Flexibilities

- Flexibility Use for the Civilian Defense Acquisition Workforce

- Direct-Hire Authority

- OPM Direct-Hire

- Direct-Hire Authorized by Statute

- Expedited Hiring Authority

- Pathways Programs and the Federal Career Intern Program

- Delegated Examining Authority

- How Have Selected Hiring Flexibilities Been Used for Civilian Defense Acquisition Positions?

- Number of External Civilian Defense Acquisition Hires Under Selected Flexibilities

- Trends in Flexibility Use for External Civilian Acquisition Hiring

- Aggregate Flexibility Use

- Individual Flexibility Use

- How Have Selected Hiring Flexibilities Affected Time to Hire?

- Factors Potentially Affecting Time to Hire

- Presence and Type of Hiring Exemptions

- Purpose of Flexibilities

- Varied Flexibility Implementation Across DOD Components

- Questions for Congress

- Are Flexibilities Effectively Improving the Civilian Acquisition Workforce?

- Does DOD Have the Appropriate Number and Type of Flexibilities?

- What Factors May Impact the Use of Available Flexibilities to Improve the Civilian Acquisition Workforce?

- Congressional Oversight Options

- Comprehensive and Accurate Data on Flexibility Use

- Proxy Measures for Determining the Effectiveness of Flexibilities

- Time to Hire From the Perspective of the Candidate

- Candidate Acceptance Rates

- Timeliness in Earning Required Certifications

- Candidate Retention and Career Progression Rates

- Study on the Effectiveness of Flexibilities

- Improved Implementing Guidance for Flexibilities

- Other Aspects of Acquisition Workforce Improvement

- Pay Flexibilities

- AcqDemo

Figures

Tables

Summary

Policymakers and defense acquisition experts have asserted that improved recruitment for the defense acquisition workforce is a necessary component for comprehensive acquisition reform. To help rebuild the workforce and enhance recruitment, DOD has used several hiring flexibilities authorized by Congress, the President, and OPM in recent years. Hiring flexibilities are a suite of tools that are intended to simplify, and sometimes accelerate, the hiring process.

The impact of hiring flexibilities on recruitment and workforce quality, however, remains unclear. Congress may consider three high-level questions regarding hiring flexibilities for the workforce:

- Are flexibilities effectively improving the workforce?

- Are the current number and type of flexibilities appropriate?

- What factors may impact effective use of flexibilities to improve the workforce?

Congress could consider several oversight options to help gauge and improve the effectiveness of flexibilities in improving the civilian defense acquisition workforce. Such options might help Congress determine whether flexibilities should be expanded or newly created, consolidated or removed, or otherwise restructured. Congress could direct DOD to

- provide data on the use of all available flexibilities to fill the full range of civilian defense acquisition positions, including any barriers to producing such data;

- establish proxy measures for effectiveness related to employee quality (such as employee timeliness in earning required certifications and retention and career progression rates) and recruitment (such as time to hire from the perspective of the candidate and job acceptance rates);

- conduct a study that evaluates the effectiveness of flexibilities; and

- improve the quality, clarity, and use of implementing guidance for flexibilities.

At least 38 hiring flexibilities are currently available for the civilian defense acquisition workforce. According to DOD, the following six flexibilities were used most frequently to fill external civilian acquisition positions between FY2008 and FY2014:

- 1. Direct-hire authority (DHA)

- 2. Expedited hiring authority (EHA) for certain civilian acquisition positions

- 3. Pathways Recent Graduates program

- 4. Pathways Internship program

- 5. Federal Career Intern Program

- 6. Delegated examining authority

The six flexibilities accounted for roughly 66% of total external civilian acquisition hires between FY2008 and FY2014 (i.e., hires from outside the government). Some of the flexibilities were available throughout the six-year period, while others were discontinued or established during that period. Potential factors affecting the use of flexibilities include their structure, clarity of implementing guidance, establishment of new flexibilities, staff knowledge of appropriate use, budgetary constraints, and efforts to balance hiring speed with equity.

Background on the Defense Acquisition Workforce1

The defense acquisition workforce consists of civilian and uniformed personnel at the Department of Defense (DOD) who manage

the planning, design, development, testing, contracting production, introduction, acquisition logistics support, and disposal of systems, equipment, facilities, supplies, or services that are intended for use in, or support of, military missions.2

The defense acquisition workforce plays a key role to ensure that DOD's contract dollars are properly spent on goods and services. As part of this role, the workforce is responsible for ensuring that acquisition programs—including major weapons and information technology (IT) systems—remain within their estimated cost and delivery schedules and produce the desired capabilities. In FY2015, DOD obligated roughly $438 billion on federal contracts, which comprised 62% of contract obligations government-wide.3

To fulfill its duties, the workforce must have an adequate number of acquisition professionals with an appropriate mix of technical skills (such as cost estimating, program management, and systems engineering). There are concerns, however, that the workforce may not be adequately sized or equipped with the skills necessary to support DOD's acquisition workload. According to a 2014 compilation of expert views published by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations), two-thirds of contributors felt that improved recruiting, training, and incentives4 for the acquisition workforce are necessary for comprehensive acquisition reform.5

Size of the Defense Acquisition Workforce

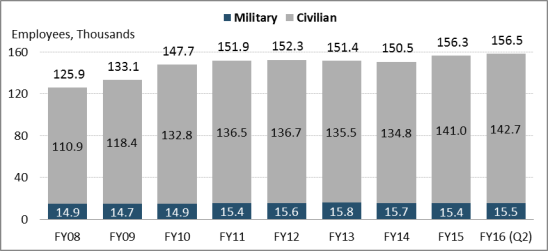

As of March 31, 2016, the defense acquisition workforce consisted of 158,212 employees, roughly 90% (142,728) employees) of which were civilians.6 Between FY2008 and FY2015, the workforce grew by 24.2%, or 30,343 employees (Figure 1). The workforce experienced the largest increase between FY2009 and FY2010, growing by 11%, or 14,602 employees. In April 2009, the Secretary of Defense launched an acquisition workforce growth initiative that aimed to add 20,000 uniformed and civilian employees to FY2008 workforce levels through 2015.7 The initiative was launched, in part, to address reported workforce size and skill imbalances resulting from past downsizing, particularly the congressionally mandated cuts to the acquisition workforce in the 1990s.8

What Hiring Flexibilities Are Applicable to the Civilian Defense Acquisition Workforce?

Background on Hiring Flexibilities

DOD has utilized several tools to help rebuild the size and capability of the acquisition workforce, one of which is hiring flexibilities. Hiring flexibilities are a suite of tools that are intended to simplify, and often accelerate, the federal hiring process. The way in which they do so, however, can vary by flexibility. Hiring flexibilities vary in structure and function in order to help agencies best meet their evolving recruitment needs. For example, some flexibilities provide hiring exemptions—waivers from competitive hiring requirements in Title 5 of the United States Code.9 Other flexibilities provide no hiring exemptions, but grant agencies more control in administering the hiring process. Flexibilities can also vary in terms of their

- Scope: Agency-specific or government-wide

- Coverage: One position or a group of positions

- Length: Temporary or permanent

- Authorization: Congress, the President, or the Office of Personnel Management (OPM)

- Service: Competitive or excepted service

Flexibility Use for the Civilian Defense Acquisition Workforce

At least 38 hiring flexibilities are currently applicable to the civilian defense acquisition workforce—24 government-wide, 11 DOD-specific, and 3 acquisition-specific. A description of each of these flexibilities can be found in Appendix A. The subsections below describe six hiring flexibilities that, according to DOD, were used most frequently for external hires to the civilian acquisition workforce between FY2008 and FY2014 (during the acquisition workforce growth initiative):

- Direct-hire authority (DHA)

- Expedited hiring authority for civilian defense acquisition workforce positions (EHA)

- Pathways Recent Graduates program (established in December 2010)

- Pathways Internship program (established in December 2010)

- Federal Career Intern Program (eliminated in March 2011)

- Delegated examining authority

Direct-Hire Authority

DHA and EHA—a type of DHA—allow agencies to appoint individuals directly to a position or group of positions without regard for certain competitive hiring requirements in Title 5 of the United States Code. The specific hiring exemptions granted and applicability vary depending on the type of DHA. There are two different types of DHAs: OPM direct-hire and direct-hire authorized by statute.10 Regardless of type, the authorities are intended to accelerate job offers, though the level of acceleration may vary depending on an agency's interpretation of the authority. Appendix A provides examples of DHAs that are applicable to defense acquisition positions.

OPM Direct-Hire

The OPM direct-hire authorizes agencies to, upon OPM approval, waive competitive hiring requirements in 5 U.S.C. §§3309-3318—veterans' preference, competitive rating and ranking, and the rule of three11—when filling positions for which OPM determines there is a severe shortage of candidates or a critical hiring need. DHAs can be established independently by OPM or upon request from an agency, though OPM ultimately determines the application and duration of the authority.12 Agencies must present evidence of a severe shortage of candidates or critical hiring need in order to receive the DHA.13

Direct-Hire Authorized by Statute

DHAs authorized by statute operate similarly to OPM direct-hire, but often differ in three primary ways:

- 1. Agencies generally do not need OPM approval to use DHAs authorized by statute and thus do not have to demonstrate the existence of a severe shortage of candidates or critical hiring need.

- 2. The authorities can exempt agencies from a broader set of competitive hiring requirements compared with the OPM direct-hire.

- 3. The authorities often apply to a specific department or agency and rarely apply government-wide.

For example, the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for FY2016 authorized a DHA that allows each military department to appoint a certain number of individuals with scientific and engineering degrees to scientific and engineering positions within the defense acquisition workforce without regard to competitive hiring requirements in 5 U.S.C. §§3301-3330.14

Expedited Hiring Authority

Expedited hiring authority (EHA) for certain defense acquisition workforce positions is a type of DHA that was first authorized by the NDAA for FY2009.15 The EHA authorizes DOD to use the OPM-direct hire to fill defense acquisition positions facing a severe shortage of candidates or critical hiring need, as identified by the Secretary of Defense rather than OPM. The EHA is the broadest of existing DHAs established exclusively for defense acquisition positions. Congress has expanded the scope and applicability of the EHA over time to include (1) all qualified individuals rather than those who are highly qualified, and (2) positions facing a critical hiring need in addition to those facing a severe shortage of candidates.16 Congress changed the EHA from a temporary to a permanent authority in 2015.17

Pathways Programs and the Federal Career Intern Program

The Pathways Recent Graduates and Pathways Internship programs are training and development programs designed to recruit high-performing individuals into the federal government and create a pipeline of talent for agencies. Under the programs, qualified individuals are temporarily appointed to agency positions and receive job-related training.18 The appointment length, eligibility requirements, and covered positions vary by program (Table 1). Upon program completion, participants can be noncompetitively converted to permanent federal positions in the competitive service.19 The two Pathways programs were based on the Federal Career Intern Program (FCIP)—a structurally distinct training and development program that was terminated on March 1, 2011, under Executive Order 13562.20 The Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) found that the FCIP violated veterans' preference and public notice laws in November 2010.21

|

Feature |

Pathways |

Pathways |

Federal Career |

|

Authorization |

EO 13562 |

EO 13162 |

|

|

Appointment length |

Up to one year. |

Up to one year, |

Up to two years. |

|

Eligibility |

Individuals who have obtained a degree from a qualifying educational institution within two years of applying. |

Current students in a qualifying education institution. |

Any qualified applicant (federal or non-federal). |

|

Job level |

Up to GS-12. Varies depending on position type and participant's level of education. |

Up to GS-11. Varies depending on position type and participant's level of education. |

GS-5, 7, and 9. |

|

Training requirementc |

Formal. |

|

Formal. |

Source: CRS analysis of OPM, "Hiring Information, Students and Recent Graduates," at https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/hiring-information/students-recent-graduates/#intern=&url=Overview; 5 C.F.R. Part 362; 5 C.F.R. 213.3402; MSPB, Building A High Quality Workforce, The Federal Career Intern Program, September 2005, and 5 C.F.R. 213.3202(o)(repealed), accessible at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2002-title5-vol1/pdf/CFR-2002-title5-vol1-sec213-3202.pdf.

a. Executive Order 13562, "Recruiting and Hiring Students and Recent Graduates," December 27, 2010, at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/DCPD-201001100/pdf/DCPD-201001100.pdf.

b. Executive Order 13162, "Federal Career Intern Program," July 6, 2000, at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/WCPD-2000-07-17/pdf/WCPD-2000-07-17-Pg1607.pdf.

c. Agencies determine the form of training provided, such as courses, job rotations, or interagency assignments, and attendance at conferences or seminars.

Positions under the Pathways programs are filled using an excepted service hiring authority, which places positions in the excepted service rather than the competitive service or Senior Executive Service.22 In so doing, the authority provides DOD with more flexibility and control over hiring for Pathways-covered acquisition positions. Namely, DOD can (1) restrict position eligibility to qualified students and recent graduates, (2) evaluate qualifications solely based on a candidate's education rather than work experience, and (3) use non-Title 5 recruitment, assessment and selection procedures, which may be more streamlined compared to procedures used for the competitive service. For example, DOD can post an abbreviated job announcement on USAJOBS for Pathways-covered acquisition positions.23

The table below provides a summary of different services within the federal civilian workforce.

|

The Federal Civil Service The federal civilian workforce includes the competitive service, excepted service, and Senior Executive Service.

The primary difference between the three services in terms of hiring is a competitive versus noncompetitive process. A competitive process requires individuals to be appointed to a federal position by competing with the general public and according to the hiring requirements in Title 5 of the United States Code. A noncompetitive process allows an individuals to be appointed to a federal position without competing with the general public and generally without regard to hiring requirements in Title 5 U.S.C (except for veterans' preference). Source: OPM, "Hiring Authorities, Overview," at https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/hiring-information/hiring-authorities/; OPM, "Veterans Employment Initiative, Vet Guide," at https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/veterans-employment-initiative/vet-guide/. |

Delegated Examining Authority

Delegated examining authority is arguably the standard for modern-day competitive federal hiring and can be considered the baseline for non-flexibility hiring. Delegated examining authority does not provide any hiring exemptions—agencies must comply with all competitive hiring requirements in Title 5 of the United States Code when filling positions under the authority. Delegated examining authority is considered a flexibility because it allows agencies, rather than OPM, to administer the federal hiring process for all competitive service positions (except Administrative Law Judge positions).24 Prior to delegated examining, federal hiring was centrally managed by OPM.25 Delegated examining is available to any agency that enters into an agreement with OPM. OPM can terminate, suspend, or revoke the agreement at any time.26

How Have Selected Hiring Flexibilities Been Used for Civilian Defense Acquisition Positions?

This section analyzes DOD's use of the six hiring flexibilities described above for some, but not all, civilian acquisition hires between FY2008 and FY2014 (Table 2). According to DOD, the data in Table 2 include external civilian acquisition hires (i.e., applicants from outside the federal government), but do not include internal civilian acquisition hires (i.e., current or former federal employees). Internal hires may represent a sizeable portion of total civilian acquisition hires each year. Two of six flexibilities were available throughout the six-year period, while one was discontinued and three were established during that period. Regardless, the flexibilities were identified by DOD as the top six used to fill civilian defense acquisition positions between FY2008 and FY2014.

Number of External Civilian Defense Acquisition Hires Under Selected Flexibilities

Approximately 66% of total external civilian defense acquisition hires were made under the six flexibilities described above between FY2008 and FY2014 (Table 2). The remaining 34% of external civilian hires were made through a mix of other hiring mechanisms that use competitive and noncompetitive procedures.

The EHA flexibility was used most frequently, accounting for 17,699 external civilian acquisition hires over the six-year period. In FY2010, the EHA accounted for the largest amount of external civilian hires in a single year among the six flexibilities—5,393 hires. A 2016 GAO report found that the EHA was one of the top 20 hiring flexibilities used for all new hires government-wide in FY2014.27 The FCIP was the second most frequently used flexibility, accounting for 13,574 of total external acquisition hires over the six-year period. The FCIP was the only flexibility used more than the EHA in a single year, in raw numbers, accounting for 3,266 more external civilian acquisition hires than the EHA in FY2009. The FCIP was the second most frequently used flexibility over the six-year period despite being eliminated on March 1, 2011, and replaced by the Pathways Recent Graduate and Internship programs.28

DHAs and the two Pathways programs were among the least used flexibilities during the six-year period. DHAs accounted for the fewest external civilian hires across the entire six-year period—1,429 hires. The two Pathways programs accounted for the fewest external civilian hires during the time they were in effect—878 external civilian hires between FY2012 and FY2014. The Pathways programs were first implemented by DOD in FY2012, which may partially explain their relatively low use.29 Delegated examining authority, which features no hiring exemptions, accounted for a larger number of external civilian acquisition hires (3,040 hires) than DHAs and the Pathways programs combined (1,761 hires) between FY2012 and FY2014—the time period in which all four flexibilities were simultaneously in effect.

Table 2. External Civilian Defense Acquisition Hires by Selected Hiring Flexibilities

FY2008 – FY2014

|

Flexibility |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

Total |

|

Expedited Hiring Authority |

N/A |

1,814 |

5,939 |

3,736 |

2,388 |

2,150 |

1,672 |

17,699 |

|

Federal Career Intern Programa |

3,326 |

5,080 |

3,875 |

1,104 |

189 |

N/A |

N/A |

13,574 |

|

Delegated Examining Authority |

1,236 |

1,461 |

934 |

920 |

1,135 |

752 |

1,153 |

7,591 |

|

Direct-Hire Authorityb |

45 |

110 |

180 |

211 |

244 |

233 |

406 |

1,429 |

|

Pathways Recent Graduates |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

0 |

186 |

577 |

763 |

|

Pathways Internship |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

5 |

70 |

40 |

115 |

|

Subtotal (flexibilities) |

4,607 |

8,465 |

10,928 |

5,971 |

3,961 |

3,391 |

3,848 |

41,171 |

|

Other external hires |

3,346 |

4,520 |

3,762 |

3,008 |

2,700 |

1,924 |

1,755 |

21,015 |

|

Total (external hires) |

7,953 |

12,985 |

14,690 |

8,979 |

6,661 |

5,315 |

5,603 |

62,186 |

Source: CRS analysis of data provided by DOD staff for the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (USD(AT&L)) dated April 6, 2015. Data validity confirmed by Director of DOD Human Capital Initiatives for USD(AT&L) on October 6, 2016.

Notes: The table includes data on the total number of external civilian acquisition hires, or individuals hired from outside the federal government. The table does not include data on internal hires, such as transfers between agencies, reassignments, details, and conversion appointments. "N/A" denotes flexibilities that were not in effect during that year.

a. Includes Student Career Experience Program participants. The Federal Career Intern Program was revoked by Executive Order 13562. The revocation went into effect March 1, 2011.

b. Includes a mix of OPM direct-hire authorities and direct-hire authorities authorized by statute.

Trends in Flexibility Use for External Civilian Acquisition Hiring

Aggregate Flexibility Use

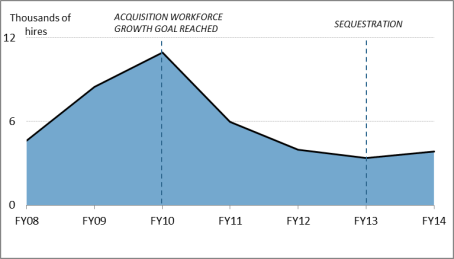

Figure 2, below, depicts trends in the aggregate use of the six most frequently used flexibilities for civilian external acquisition hiring from FY2008 to FY2014. Data from DOD show a rise in external civilian hires under the six flexibilities between FY2008 and FY2010, from 4,607 hires to 10,928 hires. External civilian hires then declined to 3,391 hires in FY2013, but experienced a slight uptick to 3,848 hires in FY2014.

The following external events may have contributed to trends in aggregate flexibility use over the six-year period:

- The acquisition workforce growth initiative: As mentioned previously, in April 2009, DOD established a goal to add 20,000 personnel to FY2008 acquisition workforce levels through 2015. DOD exceeded this goal in FY2010, adding 21,826 employees to the workforce (Figure 1). Thus, flexibility use—and overall external civilian acquisition hiring—may have surged through FY2010 to meet the growth initiative goal and declined through FY2013 after reaching it.

- Sequestration: The across-the-board budget cuts in FY2013, known as sequestration, might explain the slight uptick in flexibility use from FY2013 to FY2014. Flexibility hiring may have dipped in FY2013 due to civilian hiring freezes instituted by DOD30 in response to sequestration and then increased in FY2014, at which point sequestration was no longer in effect and certain hiring freezes were lifted.31

- Civilian acquisition workforce losses: The flexibility hiring uptick from FY2013 to FY2014 might also reflect DOD efforts to combat overall workforce losses and preserve growth achieved in previous years. The size of the overall civilian defense acquisition workforce decreased by 1,906 employees between FY2012 and FY2014, from 136,714 to 134,808 employees (Figure 1). Workforce losses outpaced growth in FY2013 and FY2014.32

- Shortfalls in certain acquisition career fields: The flexibility hiring uptick from FY2013 to FY2014 might also reflect DOD efforts to address staffing shortfalls in certain acquisition career fields. While DOD accomplished its overall acquisition workforce growth goal, a 2015 GAO report found that DOD did not meet growth targets for six acquisition career fields. The report further asserted that three of these fields that are considered as critical to reshaping the acquisition workforce—contracting, business, and engineering—experienced high attrition rates and difficulty recruiting qualified personnel.33

Individual Flexibility Use

Data from DOD also show notable patterns in individual flexibility use during the six-year period, which might have resulted from a mix of structural changes and external events. Some notable patterns include the following:

- EHA: EHA use surged between FY2009 and FY2010, from 1,184 to 5,080 external civilian acquisition hires. In contrast, use of two of the remaining three most frequently used flexibilities in place during that time decreased. The EHA was expanded to cover a broader range of acquisition positions at the beginning of FY2009, which may have reduced the use of other flexibilities.

- FCIP: FCIP use consistently decreased between FY2009 and FY2014, with the largest decreases occurring between FY2010 and FY2011—from 3,875 to 1,104 external civilian acquisition hires. These decreases were likely in response to the November 2010 ruling that the FCIP violated certain hiring laws and the December 2010 announcement that the program would be terminated on March 1, 2011.

- DHAs: Although among the least-used identified flexibilities, use of DHAs generally increased between FY2008 and FY2014. The largest increase in DHA use occurred between FY2013 and FY2014, from 233 to 406 external civilian acquisition hires. These increases may reflect a rising number of DHAs available for the civilian defense acquisition workforce. For example, Congress authorized two new DHAs for DOD Science and Technology Reinvention Laboratories (STRLs) in 2013 that are applicable to certain scientific and engineering acquisition positions.34

How Have Selected Hiring Flexibilities Affected Time to Hire?

While the previous section discussed the use of flexibilities over time to fill civilian defense acquisition positions, this section discusses time to hire under the flexibilities. Table 3 presents data from DOD on average time to hire between FY2008 and FY2014 for five of the six hiring flexibilities described above—the flexibilities that are still currently available. Time to hire is presented for the years that flexibilities were available during the six-year period. DOD defines time to hire as the number of days from the date of the Request for Personnel Action (SF-52)35 to the appointment date.

As shown in Table 3, there are no discernible time to hire trends across all five flexibilities—time to hire fluctuates within and between flexibilities from year to year. However, some flexibility-specific trends exist in relation to OPM's 80-day hiring model.36 Specifically:

- Delegated examining authority—the only flexibility in Table 3 that provides no hiring exemptions and can be used as a baseline for standard competitive hiring—did not meet the 80-day hiring timeline in any year between FY2008 and FY2014.

- The EHA met the 80-day timeline in FY2009 (65 days). Average hiring speed under the EHA then slowed between FY2009-FY2013. The number of civilian external hires made under the EHA also declined each year between FY2009 and FY2013.

- The Pathways Internship program consistently met the 80-day hiring timeline between FY2012 – FY2014. In contrast, the Pathways Recent Graduates program consistently missed the 80-day timeline between FY2013-FY2014. As mentioned previously, DOD began implementing these programs in 2012, but only made hires under the Internship program in FY2012.37

- DHAs did not meet the 80-day timeline, but was the only flexibility to be within five days of the timeline for three consecutive years—FY2009 to FY2011.

|

Flexibility |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

|

Delegated examining authority |

130 |

125 |

144 |

117 |

90 |

111 |

85 |

|

Expedited hiring authority |

N/A |

65 |

85 |

97 |

104 |

134 |

98 |

|

Direct-hire authority |

101 |

81 |

82 |

85 |

102 |

96 |

93 |

|

Pathways – Recent Graduates |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

83 |

92 |

|

Pathways – Internship |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

56 |

38 |

62 |

Source: Data provided to CRS by USD(AT&L) staff dated April 6, 2015, and March 21, 2016.

Notes: Time to hire is defined as the number of days from the date of the Request for Personnel Action (SF-52) to the appointment date. The "Average" column may not reflect averages calculated from data in the table. The "other external hiring" row includes hires made with a mix of competitive and noncompetitive procedures. "N/A" denotes flexibilities that were not in effect during that year.

Factors Potentially Affecting Time to Hire

Several factors may contribute to fluctuations in time to hire within and between the flexibilities listed in Table 3. Some of these factors are discussed in the sections below.38

Presence and Type of Hiring Exemptions

The presence of hiring exemptions may contribute to faster hiring. For instance, DOD data in Table 3 show that hiring under DHAs and EHA was faster than delegated examining authority for certain fiscal years. Certain Title 5 hiring requirements—such as competitive rating and ranking and veterans' preference—do not apply under the EHA and DHAs, while they do under delegated examining. According to a 2001 MSPB report, agency supervisors estimated that rating and ranking took an average of 21 days to complete under merit promotion—the second most time consuming hiring procedure identified in the report.39

The type of hiring exemptions may also affect time to hire. For example, hiring was faster under the Pathways Internship program compared to the EHA and DHA between FY2012 and FY2014. The Pathways Internship program does not waive veterans' preference or competitive rating and ranking like the EHA and DHAs.40 However, Pathways Internship allows for simplified job announcements that do not have to be posted on USAJOBS.gov and the use of agency-developed, rather than OPM-developed, qualification standards.41 These exemptions may have contributed to faster hiring under the Pathways Internship program. As mentioned previously, the two Pathways programs were first implemented in FY2012, which may affect their time to hire.

Purpose of Flexibilities

Some hiring flexibilities are not designed to accelerate hiring. For example, delegated examining authority is designed to ensure that all candidates are given a fair and equal chance to obtain a position, specifically by having them compete with one another based on their knowledge, skills, and abilities.42 These flexibilities, however, may still accelerate the hiring process. According to a 1999 MSPB report, agencies believed that delegated examining resulted in faster and more effective hiring compared to OPM's centralized hiring system.43

Varied Flexibility Implementation Across DOD Components

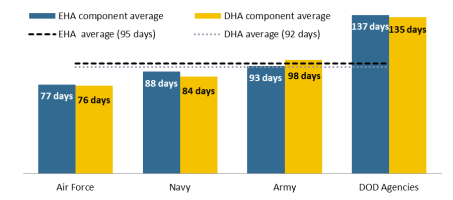

Time to hire for individual flexibilities can vary by DOD component based on their interpretation of the flexibilities' governing laws. The laws provide broad discretion for implementation procedures and application of hiring exemptions. For example, DOD officials stated that the Departments of the Navy and Air Force have a broad interpretation of laws governing the DHA and EHA, while the Department of the Army "takes a very risk adverse [sic] approach."44 This might partially explain component-level time to hire differences for the two flexibilities (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. EHA and DHA Time to Hire by DOD Component, FY2008-FY2014 |

|

|

Source: Data provided to CRS by DOD staff by electronic mail on August 28, 2015. Notes: The Department of the Navy includes the U.S. Marine Corps. "DOD Agencies" includes all organizational entities within DOD that are not in military departments or combatant commands, including agencies and DOD field activities under the Office of the Secretary of Defense. For more information, see http://dcmo.defense.gov/Portals/47/Documents/PDSD/201509_DoD_Organizational_Structure.pdf. |

More broadly, DOD components may have different internal hiring procedures that affect time to hire. While the components must abide by the applicable Title 5 hiring requirements, they have wide discretion to develop unique internal hiring policies and procedures within those requirements. For example, some components may hold a series of interviews for each best qualified candidate, whereas others may only hold one interview per candidate. In addition, components may have different approval and vetting processes for selecting final candidates.

Questions for Congress

As Congress continues to consider reforms to the defense acquisition system, the following policy questions regarding hiring flexibilities for the civilian defense acquisition workforce may be of interest:

- Are flexibilities improving the civilian defense acquisition workforce?

- Does DOD have the appropriate number and type of flexibilities?

- What factors may impact effective use of available flexibilities to improve the civilian defense acquisition workforce?

Are Flexibilities Effectively Improving the Civilian Acquisition Workforce?

A fundamental question is whether available hiring flexibilities are improving the acquisition workforce, or effectively recruiting high-quality acquisition professionals with the right skills to the workforce and placing them in appropriate positions in a timely manner. Accurate and comprehensive data on the use of flexibilities is an integral first step in determining their effectiveness. Such data could identify, among other things, which flexibilities are used most frequently and the specific features that are most useful in recruiting high-quality acquisition personnel.

As mentioned previously, however, the flexibility usage data provided by DOD is limited—it only reflects a subset of civilian acquisition hires (external hires) and may contain some counting discrepancies. These limitations might be partially attributable to the lack of hiring codes for individual flexibilities. According to a 2016 GAO report, OPM's hiring codes do not always link to individual hiring flexibilities and sometimes "represent an unknown number" of flexibilities.45

Does DOD Have the Appropriate Number and Type of Flexibilities?

Some analysts may argue that the current number and structure of flexibilities is sufficient, based on several arguments:

- DOD exceeded its acquisition workforce growth goal and should focus on retention of acquisition talent through other tools.

- Flexibilities have been expanded over time to cover a broad range of acquisition positions. For example, the EHA has been made permanent and expanded to cover an increasing number of positions in the majority of acquisition career fields.

- Some flexibilities are not used effectively, and if used more effectively, would preclude the need for more flexibilities. DOD officials have acknowledged that two flexibilities currently available to fill certain acquisition positions—the Intergovernmental Personnel Act (IPA) and Highly Qualified Expert (HQE) authority—are underutilized.46 More broadly, a 2016 GAO report found that a "relatively small number" of hiring flexibilities (20) accounted for 91% of new hires government-wide in FY2014.47

In contrast, other analysts may argue that continued recruitment problems indicate the need for expanded or additional flexibilities, such as

- reported staffing shortfalls in six acquisition career fields, three of which are considered as critical to reshaping the acquisition workforce and whose shortfalls were partly driven by difficulty in hiring qualified personnel—contracting, engineering, and business;48 and

- reported difficulty recruiting acquisition talent from certain populations in the labor market, such as students and recent graduates. For example, although the Pathways programs allow for targeted recruitment of students and recent graduates, DOD acquisition officials asserted that the lack of a direct hire authority for those populations creates hiring challenges at campus recruiting events.49 Section 1106 of the NDAA for FY2017 (S. 2943), as passed by the Senate, would create a DHA for post-secondary students and recent college graduates.50 The provision was not included in the subsequently House-passed version of S. 2943.51

What Factors May Impact the Use of Available Flexibilities to Improve the Civilian Acquisition Workforce?

Several factors may impact the use of flexibilities for the defense acquisition workforce, and by extension, their effectiveness in improving the workforce. These factors include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Flexibility structure: As mentioned previously, 35 of 38 identified flexibilities are applicable to, but not explicitly targeted at, defense acquisition positions. In addition, some of these flexibilities have arguably narrow eligibility criteria, which may affect their use for acquisition positions. For example, DHAs for scientific and engineering positions at DOD STRLs include degree requirements and usage caps.52 The NDAA for FY2016 authorized acquisition-specific DHAs nearly identical to those for STRLs.53

- Budgetary constraints: Flexibility use may be affected by cost-cutting initiatives—such as workforce reductions and hiring freezes—instituted by DOD in response to congressional mandates to reduce the size and cost of its civilian workforce54 and discretionary spending limits in place through 2021 by the Budget Control Act of 2011.55 For example, in March 2011, the Secretary of Defense announced the elimination of 33 HQEs as part of a department-wide initiative to reduce overhead costs.56

- Recruitment needs: Use of individual flexibilities may have fluctuated over time to meet DOD's evolving acquisition workforce needs and goals. For instance, as mentioned previously, increased use of the EHA in FY2010 may have occurred to help reach the acquisition workforce growth goal established in FY2009.

- Establishment of new flexibilities: Some hiring flexibilities may be used less or no longer needed due to the establishment of new flexibilities. For example, DOD officials reported that some flexibilities available under the Civilian Defense Acquisition Personnel Demonstration Project (AcqDemo)—such as modified rating and ranking and scholastic achievement appointment57—have been largely superseded by the EHA and Pathways programs.58 Some Interviewees for a 2011 RAND report also asserted that some of AcqDemo's flexibilities have been superseded by the EHA.59

- Limited knowledge of flexibilities: Given the amount and complex structure of flexibilities, some DOD staff might be unfamiliar with (1) the full range of flexibilities that are available for the defense acquisition workforce, (2) the positions they cover, or (3) how to implement their individual requirements.60 For example, DOD officials noted that hiring managers have the "impression" that using the HQE authority is too difficult and recommended identifying strategies to address this "misconception."61

- Unclear/inconsistent implementation guidance: Unclear or inconsistent implementing guidance on flexibilities—at the department or component-level—may lead to improper or inefficient use. Some DOD acquisition officials reported difficulty using certain flexibilities due to unclear guidance on the application of veterans' preference.62 For example, some DOD components appear to apply veterans' preference under the EHA, though the flexibility appears to waive it.63 This may stem from confusion over applicable department-level EHA guidance, which directed components to "make offers to qualified candidates with veterans' preference whenever practicable"64 (italics added).

- Balancing hiring speed and equity: As recommended by OPM and MSPB, DOD may be balancing the use of hiring flexibilities with traditional competitive hiring to achieve efficient, high-quality hiring.65 During a congressional hearing, one DOD official noted the efficiency of the EHA, but also acknowledged the importance of traditional competitive hiring to ensure fair and equal consideration of all qualified candidates.66

Congressional Oversight Options

The oversight options presented in this section may help Congress gauge whether the current number and type of hiring flexibilities are appropriate and are improving the civilian acquisition workforce. Doing so may enable Congress to consider (1) expanding or authorizing new flexibilities, (2) consolidating or removing flexibilities, (3) otherwise restructuring flexibilities, and/or (4) using other tools to achieve workforce reforms.

Comprehensive and Accurate Data on Flexibility Use

As stated above, comprehensive and accurate data on the use of flexibilities is integral to determining their effectiveness in improving the civilian acquisition workforce. However, such data is not publicly available and may be difficult to produce. As such, Congress might consider directing DOD to

- report, to the extent possible, the total number of all civilian acquisition hires—internal and external—made under all available hiring flexibilities. If such data cannot be reported, DOD could be further directed to identify barriers to providing such data, including any issues with assigning hiring codes to individual flexibilities.

- develop an internal system to identify and track the use of all individual hiring flexibilities for civilian acquisition positions. The system could take many forms, such as an internal coding structure that is cross-walked with OPM's existing hiring codes.

Proxy Measures for Determining the Effectiveness of Flexibilities

In addition to gathering usage data, Congress might also consider requiring DOD to report on four additional metrics to help determine the effectiveness of flexibilities in improving the acquisition workforce. The metrics could serve as proxy measures for flexibilities' recruitment power and the quality of acquisition personnel hired under flexibilities. Four examples of additional metrics are discussed below.

Time to Hire From the Perspective of the Candidate

This measure might help determine whether flexibilities accelerate the hiring process from the view of the candidate rather than the agency. Specifically, measuring the days from closing a vacancy announcement to a conditional offer would isolate the impact of a flexibility on hiring procedures that directly affect a candidate's waiting time in the hiring process (such as rating and ranking, interviews, and selection). DOD currently measures time to hire from the perspective of the agency—from the request for personnel action to the candidate's appointment date67—thus capturing days dedicated to procedures that do not affect a candidate's waiting time (such as reviewing a position description and conducting a job analysis).68 As such, it is difficult to determine how effective flexibilities are in expediting job offers from the candidate's view.

Candidate Acceptance Rates

Formally tracking the number of first choice candidates who accept a job offer for an acquisition position may help determine whether and which flexibilities minimize the loss of top talent to other entities. For example, suppose that 20% of first choice candidates decline job offers for contracting positions filled under the EHA, compared to 50% under traditional competitive hiring. This, in tandem with the aforementioned time to hire data, might indicate that the EHA's hiring exemptions affected candidates' decisions to accept job offers. In contrast, similar or lower acceptance rates under the EHA might indicate little to no impact of the flexibility on recruiting first choice candidates. DOD components are generally not required, statutorily or by internal guidance, to routinely report on job acceptances or declinations under flexibilities.69

Timeliness in Earning Required Certifications

Pursuant to the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (DAWIA), DOD established certifications for defense acquisition workforce positions that include education, training, and experience requirements.70 Acquisition personnel must earn the DAWIA certifications associated with their respective positions within two years of their appointment.71 The following metrics related to DAWIA certifications might shed light on which flexibilities are most effective in recruiting high-quality acquisition personnel:

- the number of employees hired under flexibilities who are eligible to earn the appropriate DAWIA certification at the time of appointment,

- the number of employees hired under flexibilities who earn the appropriate DAWIA certification within the required 24-month timeframe, and

- the amount of time taken to earn the DAWIA certification.

Candidate Retention and Career Progression Rates

Tracking retention rates and career progression rates under flexibilities might help determine whether flexibilities attract acquisition professionals who stay longer and gain position-specific expertise faster relative to professionals recruited through standard competitive hiring.

Study on the Effectiveness of Flexibilities

Consistent with GAO's recommendations on hiring authorities,72 Congress might consider directing the DOD inspector general or a special task force—such as the Advisory Panel on Streamlining and Codifying Acquisition Regulations73—to conduct a study on the overall effectiveness of flexibilities in improving the civilian acquisition workforce. Results from the study could help determine whether flexibilities should be expanded or created, consolidated or removed, or otherwise restructured. The study could, among other things,

- evaluate the use of all available flexibilities to fill civilian acquisition positions (as described above), including the extent to which flexibilities are targeted at critical or understaffed acquisition career fields. As mentioned previously, a 2015 GAO report found that six of 13 acquisition career fields fell below their planned growth levels, three of which are deemed as critical to reshaping the acquisition workforce—contracting, business, and engineering.74

- implement the proxy measures described above for determining flexibilities' recruitment power and quality of acquisition personnel hired under flexibilities;

- identify the factors that affect the effective use of flexibilities for the workforce, including those previously described; and

- determine whether personnel hired under flexibilities have improved defense acquisition outcomes, such as delivering acquisition programs with the desired capabilities within the projected costs and timeline.

Improved Implementing Guidance for Flexibilities

Congress could direct DOD to undertake specific activities, such as the ones listed below, to clarify and align department- and component-level implementing guidance for hiring flexibilities. Such clarification might improve their use and effectiveness in improving the workforce:

- Mandatory training: DOD staff for the Office of the Undersecretary for Personnel and Readiness (USD(P&R)), in coordination with USD(AT&L) staff, could provide training to DOD component and sub-component human resources staff on proper interpretation of department-level implementing guidance for flexibilities. Training could occur whenever revised guidance is issued, or on a more frequent cycle.

- Periodic reviews: USD(P&R) staff, in coordination with USD(AT&L) staff, could periodically review component and sub-component level implementing guidance to ensure alignment with department-level guidance. As part of this requirement, DOD components and sub-components could be directed to notify P&R staff when revised guidance is issued and submit a copy of the guidance.

- Technical assistance: Prior to issuing final implementing guidance, DOD components and sub-components could involve USD(P&R) and USD(AT&L) staff, in an advisory capacity, during the drafting phase to help mitigate any potential discrepancies with department-level guidance.

DOD has taken steps to encourage better use of hiring flexibilities department-wide. The USD(AT&L) and USD(P&R) offices began holding joint summits on acquisition workforce recruitment and retention issues in 2015, which have resulted in several recommendations to use flexibilities more effectively. As a result of one summit, DOD updated its department-level EHA guidance in December 2015, which aimed to clarify the application of certain hiring exemptions, such as veterans' preference and competitive rating and ranking.75

Other Aspects of Acquisition Workforce Improvement

While this report has focused on enhancing recruitment through hiring flexibilities for the civilian defense acquisition workforce, Congress may also want to consider other workforce improvement efforts, such as retaining acquisition personnel that have been hired. As mentioned previously, a 2016 GAO report found that high attrition rates contributed to shortfalls in certain acquisition career fields. While hiring flexibilities aim to enhance the recruitment of qualified individuals, they are not necessarily structured to retain them. The subsections below describe two efforts undertaken by Congress and DOD in recent years to increase the retention of acquisition personnel: pay flexibilities and AcqDemo.

Pay Flexibilities

Pay flexibilities aim to increase retention by providing additional or higher compensation that is not typically available to federal employees. DOD officials asserted that the department is exploring ways to better use OPM-issued retention incentives, such as targeting incentives to acquisition career fields experiencing high attrition. DOD officials further noted that use of retention incentives is restricted to employees who are likely to leave federal service and "needs to" be expanded to those likely to leave the current organization.76 Congress has also authorized pay flexibilities for the defense acquisition workforce. For instance, the FY2016 NDAA authorized DOD to pay certain acquisition personnel up to 150% above the basic pay rate for level I of the Executive Schedule,77 which exceeds GS-15, step 10 pay rates.78

AcqDemo

AcqDemo is an alternative personnel system that operates outside the GS and waives certain personnel laws and regulations. AcqDemo features, among other things, consolidated pay bands and a contribution-based performance management system. These structures are intended to provide a stronger link between pay and performance, particularly by basing pay increases on contribution to the agency.79 A 2014 RAND report found higher retention rates among AcqDemo employees compared to those covered by the GS and other alternative personnel systems.80 Congress and DOD have taken steps to expand the scope and use of AcqDemo,81 including (1) expanding the participation cap to 120,000 employees,82 (2) extending operation to December 31, 2020,83 and (3) streamlining the application process to join the project.84 Section 1104 of the NDAA for FY2017 (S. 2943), as passed by the Senate, would establish a new personnel system for defense acquisition personnel and support staff.85 According to the Senate Committee on Armed Services report accompanying S. 2943, the provision would, among other things, change AcqDemo from a temporary, OPM/DOD-controlled system to a permanent, DOD-controlled system.86 The provision was not included in the subsequently House-passed version of S. 2943.87

Appendix A. Hiring Flexibilities Available for the Civilian Defense Acquisition Workforce

|

Hiring Flexibility |

Authorities |

Summary |

|

DOD acquisition-specific |

||

|

1. Expedited hiring authority for certain civilian defense acquisition workforce positions |

10 U.S.C. §1705(g) |

Authorizes DOD to use the authorities in 5 U.S.C. §3304(a) to appoint individuals to certain civilian defense acquisition positions facing a severe shortage of candidates or critical hiring need, as determined by the Secretary of Defense. Authority may be used to make permanent, temporary, and time-limited appointments. |

|

2. Direct-hire authority (DHA) for technical acquisition experts* |

10 U.S.C. §1701 note |

Authorizes individuals with scientific and engineering degrees to be appointed to scientific and engineering positions within the defense acquisition workforce at military departments without regard to competitive hiring requirements in 5 U.S.C. §3301-3330. In any calendar year, the number of appointments made under the authority cannot exceed 5% of the total number of covered positions filled in each military department in the previous fiscal year. Authority is currently set to expire on December 31, 2020. |

|

3. DHA for veteran technical acquisition experts* |

10 U.S.C. §1701 note |

Authorizes the Secretary of Defense to implement a pilot program to assess the feasibility and advisability of appointing qualified veterans to scientific, engineering, technical, and mathematics positions within the defense acquisition workforce in military departments without regard to competitive hiring requirements in 5 U.S.C. §3301-3330. In any calendar year, the number of appointments made under the authority cannot exceed 1% of the total number of acquisition workforce positions filled in each military department in the previous fiscal year. Authority is currently set to expire on November 25, 2020. |

|

4. Civilian Defense Acquisition Workforce Personnel Demonstration Project (AcqDemo) – Simplified accelerated hiring |

10 U.S.C. §1762 |

Modifies the numerical rating method by assigning candidate one of three scores rather than any score on a scale of 100: 70, 80, and 90. Candidates are then placed into one of three quality groups for further evaluation—basically qualified (70 or above), highly qualified (80 or above), or superior (90 or above). Veterans' preference applies. |

|

5. AcqDemo – Voluntary Emeritus Program |

Allows DOD components to temporarily retain AcqDemo employees in the Business Management and Technical Management career path who have retired or accepted a buy-out to continue working on a project for a specified period of time. Participants may also mentor and train less experienced employees. Participants receive no salary or other compensation except reimbursement for official travel. |

|

|

DOD-specific |

||

|

6. DHA for veterans in scientific, engineering, mathematical, and technical positions |

10 U.S.C. §2358 note |

Authorizes the appointment of qualified veterans to scientific, engineering, mathematical, and technical positions in a Science and Technology Reinvention Laboratory (STRL) or other DOD research and engineering entity designated by the Secretary of Defense without regard to competitive hiring requirements in 5 U.S.C. §3301-3330. In any calendar year, the number of appointments made under the authority cannot exceed 3% of the total number of scientific, engineering, mathematical, or technical positions in each STRL. Authority is currently set to expire on December 31, 2019. |

|

7. DHA for individuals with bachelor's degrees in STRL scientific and engineering positions |

10 U.S.C. §2358 note |

Authorizes the director of any STRL to appoint qualified individuals with bachelor's degrees in a scientific or engineering field to temporary, term, or permanent STRL scientific or engineering positions without regard for competitive hiring requirements in 5 U.S.C. §3301-3330 (other than sections 3303 and 3328). In any calendar year, the number of appointments under the authority cannot exceed 6% of the total number of scientific and engineering positions within each STRL. Authority is currently set to expire on December 31, 2019. |

|

8. DHA for individuals with advanced degrees in STRL scientific and engineering positionsb |

10 U.S.C. Ch. 81 |

Authorizes the director of any STRL to appoint qualified individuals with advanced degrees to temporary, term, or permanent STRL scientific or engineering positions without regard for competitive hiring requirements in 5 U.S.C. §3301-3330 (other than sections 3303 and 3328). In any calendar year, the number of appointments under the authority cannot exceed 5% of the total number of scientific and engineering positions within each STRL in the previous fiscal year. |

|

9. DHA for students enrolled in scientific and engineering programs in STRL scientific and engineering positions* |

10 U.S.C. §2358 note |

Authorizes the director of any STRL to appoint qualified individuals pursuing a bachelor's or advanced degree in a scientific, technical, engineering, or mathematical field to temporary or term STRL scientific and engineering positions without regard to competitive hiring requirements in 5 U.S.C. §3301-3330 (other than sections 3303 and 3328). In any calendar year, the number of appointments under the authority cannot exceed 3% of the total number of scientific and engineering positions filled within each STRL in the previous fiscal year. Authority is currently set to expire on December 31, 2019. |

|

10. Experimental Personnel Program for Scientists and Technical Personnel |

5 U.S.C. §3104 note |

A DOD personnel program that is intended to facilitate the recruitment of science and engineering experts for research and development project at certain DOD facilities. Program is currently set to expire on September 30, 2019. Hiring: Under the program, the Secretary of Defense may noncompetitively (see "Notes" for a definition) appoint scientists and engineers to scientific and engineering positions that do not exceed: (1) 100 positions at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, (2) 40 positions at designated laboratories in each of the military services, and (3) 10 positions in the Office of the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation. Appointments can last up to 4 years, with the opportunity to extend for an additional 2 years. Pay: Employees in covered positions to earn: (1) basic pay rates up to level II or III on the Executive Schedule (a special non-GS pay scale), which exceed GS-15, Step 10 pay rates, and (2) additional monetary incentives that may not be available to all federal employees. Additional payments cannot exceed the amounts specified in the governing statute. |

|

11. Highly Qualified Experts (HQE)* |

5 U.S.C. §9903 |

Hiring and pay flexibility intended to "bring enlightened thinking and innovation to advance the DOD national security mission." Hiring: Authorizes DOD to appoint individuals with an "uncommon level of expertise and recognition" to various positions without regard for competitive hiring and pay requirements in 5 U.S.C. 9902, 5304, and 5376. HQEs can be appointed for up to five years to work on short-term projects and may not exceed 2,500 at any given time. Pay: HQEs can earn up to level IV on the Executive Schedule without locality pay adjustments and up to level III with locality pay adjustments. Level IV salaries are equivalent to, and level III salaries exceed, GS-15, Step 10 pay rates. HQEs are also eligible for special bonuses that are not typically available to other federal employees. |

|

12. Information Assurance Scholarship Program (IASP) |

10 U.S.C. §2200a |

A scholarship program that provides financial assistance to students who are pursuing undergraduate or advanced degrees or certifications in information assurance disciplines. Hiring: Upon completion of their degree program, program participants can be noncompetitively appointed to DOD IT positions in the excepted service. Upon completion of two years in the excepted service, an IASP participant may be noncompetitively converted to a permanent competitive service position. |

|

13. Science, Mathematics, and Research for Transformation (SMART) Scholarship Program |

10 U.S.C. §2192a |

A scholarship program that provides financial assistance to students who are pursuing undergraduate or graduate degrees in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) disciplines. Hiring: Upon completion of their degree program, scholarship recipients may be noncompetitively appointed to an excepted service position at a sponsoring DOD facility. Upon completion of two years in the excepted service, the employee may be noncompetitively converted to a permanent competitive service position. |

|

14. Defense Civilian Intelligence Personnel System (DCIPS) excepted service hiring authority |

10 U.S.C. §1601 |

A non-GS personnel system for DOD intelligence employees. Individuals covered under DCIPS are noncompetitively appointed to positions in the excepted service and may receive monetary incentives that are not typically available to GS employees. |

|

Government-wide |

||

|

15. DHA for Information Technology Management |

5 U.S.C. §3304(a) |

Authorizes individuals to be appointed to positions in the GS-2210 Information Technology Management-Information Security series facing a severe shortage of candidates or critical hiring need without regard to competitive hiring requirements in 5 U.S.C. §3309-3318. Applies to covered positions at GS-9 and above at all agencies and locations. |

|

16. DHA for positions involved in Iraqi Reconstruction efforts |

5 U.S.C. §3304(a) 5 C.F.R. Part 337 |

Authorizes individuals to be appointed to positions involved in Iraqi Reconstruction efforts that require fluency in Arabic or other related Middle Eastern languages facing a severe shortage of candidates or critical hiring need without regard to competitive hiring requirements in 5 U.S.C. §3309-3318. Applies to covered positions at all WG level, single-grade interval occupations on the GS, and two-grade interval GS occupations at GS-9 and above at all agencies and locations. |

|

17. Delegated Examining Authority |

5 U.S.C. §1104(a) |

Authorizes agencies, rather than OPM, to directly administer the federal hiring process and manage all associated recruitment, assessment, and selection procedures. Applies to all federal positions, except Administrative Law Judge positions. |

|

18. Pathways – Internship program |

E.O. 13562 5 C.F.R. Part 362 |

A training and development program intended to expose students at qualified education institutions to federal agency work. Participants may, but are not required to, receive formal training during the program. Replaces the Student Career Experience (SCEP) and Student Temporary Employment (STEP) programs. Hiring: Participants are noncompetitively appointed to various positions in participating agencies for up to one year, or indefinitely until the participant's education requirement is met. Upon completion, participants may be noncompetitively converted to a permanent competitive service position. |

|

19. Pathways – Recent Graduate program |

A training and development program intended to attract and retain recent graduates to federal careers. Participants must receive at least 40 hours of formal, interactive training per year. Hiring: Participants can be noncompetitively appointed to various federal positions up to GS-12 across participating agencies for up to two years. Upon completion of the program, participants may be noncompetitively converted to a permanent position at the agency. |

|

|

20. Pathways - Presidential Management Fellows(PMF) program |

A training and development program intended to attract and retain qualified individuals with graduate or professional degrees who are interested in the "leadership and management of public policies and programs." PMFs must receive at least 80 hours of formal, interactive training per year. PMFs must also receive at least one 4 to 6 month rotational developmental assignment with full-time management or technical responsibilities, which can occur at the PMF's agency or another agency. Hiring: Participants re noncompetitively appointed to various positions from GS-9 to GS-12 at participating agencies for two years. Upon completion of the program, PMFs may be noncompetitively converted to a permanent position at the agency. |

|

|

21. Intergovernmental Personnel Act (IPA) |

5 U.S.C. §3371-3375 |

A personnel exchange program that is intended to strengthen management capabilities of federal agencies and enhance employee performance. IPA authorizes the temporary exchange of employees between the federal government and state and local governments, institutions of higher education, and other private sector or nonprofit organizations for up to two years. IPA participants must be federal employees or members of certified organizations under the law. Agencies may choose to pay all, some, or none of the costs associated with the assignment. |

|

22. Promotion and Internal Placement |

5 C.F.R. Part 335 |

Authorizes an agency to promote, demote, or reassign a current career or career-conditional employee without competing with the general public. Competitive hiring procedures under merit promotion may or may not apply depending on the type of position being filled. Veterans' preference does not apply. |

|

23. Transfers Within Government |

5 C.F.R. §315.501 5 C.F.R. Part 335 |

Authorizes a current federal employee at one agency to be appointed to a position at another agency without competing with the general public. Employees transferring to a higher-graded position must be appointed using competitive hiring procedures, whereas employees transferring to an equal or lower-graded position may or may not depending on the agency. Veterans' preference does not apply. |

|

24. Details |

5 U.S.C. §3341 5 C.F.R. Part 300, Subpart C |

Authorizes a current federal employee in one position to be temporarily assigned to a different position—either at the same agency or a different agency. Details can last no longer than 120 days, except when they are made for DOD employees: (1) in relation to a closure or realignment of a military installation or an organizational restructuring of the department as part of a reduction to the size of the uniformed or civilian DOD workforce, and (2) the position is eliminated on or before the date of the closure, realignment, or restructuring. Employees can generally be noncompetitively appointed to details. However, individuals pursuing details to higher graded positions or to those that last over 120 days must go through the competitive hiring process. |

|

25. Experts and Consultants |

5 U.S.C. §3109 5 C.F.R. Part 304 |

Authorizes agencies to noncompetitively appoint a qualified expert or consultant to a position that requires intermittent and/or temporary employment. Experts and consultants may be employed on a full-time basis for a maximum of two years—one year for an initial appointment, with the opportunity to be reappointed for one additional year. |

|

26. Scientific and Professional (ST) Positions |

5 U.S.C. §3104 5 U.S.C. §3325 5 C.F.R. Part 319 |

A subset of competitive service positions that are classified above GS-15 and involve high-level research and development in physical, biological, medical, or engineering sciences (or a related field). ST positions do not involve executive or management responsibilities. The Director of OPM sets the maximum number of ST positions available and their allocation at executive branch agencies. Hiring: Qualified individuals are noncompetitively appointed to ST positions in the competitive service. Pay: Individuals in ST positions can earn basic pay rates up to level II or III on the Executive Schedule, which exceed GS-15, Step 10 pay rates. Employees in ST positions can also be nominated for Presidential Rank Awards—Distinguished Rank recipients are awarded a bonus of 35% of their basic pay, and Meritorious Rank recipients are awarded a bonus of 20% of their basic pay. |

|

27. Senior Executive Service |

5 U.S.C. §3131-3136 |

Includes positions that are not in the competitive or excepted services. The SES is a cadre of executive managers that direct the work of an organizational unit, monitor progress toward organizational goals, and exercises other policy-making or other executive functions, among other things. Hiring: Individuals are appointed to SES positions according to SES-specific selection and hiring procedures established in the governing statutes. Pay: Employees in SES positions can earn basic pay rates up to level II or III on the Executive Schedule, which exceed GS-15, Step 10 pay rates. Employees in SES positions can also be nominated for Presidential Rank Awards—Distinguished Rank recipients are awarded a bonus of 35% of their basic pay, and Meritorious Rank recipients are awarded a bonus of 20% of their basic pay. |

|

28. Senior Level (SL) Positions |

5 U.S.C. §5108 5 U.S.C. §3324 5 C.F.R. Part 319 |

Includes competitive service positions that are classified above GS-15 and do not fall within the ST or SES categories. The Director of OPM sets the maximum number of SL positions available and their allocation at executive branch agencies (except for certain intelligence agencies and the SES). Hiring: No hiring exemptions. Competitive hiring requirements apply. Pay: Employees in SL positions can earn basic pay rates up to level II or III on the Executive Schedule, which exceed GS-15, Step 10 pay rates. Employees in SL positions can also be nominated for Presidential Rank Awards—Distinguished Rank recipients are awarded a bonus of 35% of their basic pay, and Meritorious Rank recipients are awarded a bonus of 20% of their basic pay. |

|

29. Temporary Appointments |

5 C.F.R. Part 316, Subpart D |

Authorizes agencies to appoint individuals to positions for up to one year to fulfill a short-term need, such as reorganization and completion of a specific project or peak workload. Appointments may be extended up to a maximum of one additional year (2 years of total service). Hiring: Individuals are generally appointed using competitive hiring procedures unless they qualify for a noncompetitive appointment, as listed in 5 C.F.R. §316.402. |

|

30. Term Appointments |

5 C.F.R. Part 316, Subpart C |

Authorizes agencies to appoint individuals for more than 1 year, but not more than 4 years, to positions where the employee's services are not permanent. Examples of non-permanent needs include project work, extraordinary workload, and reorganization. Hiring: Individuals are generally appointed using competitive hiring procedures when making term appointments. Individuals are appointed using competitive hiring procedures unless they qualify for a noncompetitive appointment, as listed in 5 C.F.R. §316.302. |

|

31. Veterans' Recruitment Appointment (VRA) |

38 U.S.C. §4214 |

Authorizes agencies to noncompetitively appoint eligible veterans to positions in the excepted service up to GS-11. Veterans who are eligible for veterans' preference are not necessarily eligible for VRA. |

|

32. Veterans Employment Opportunities Act (VEOA) of 1998 |

5 U.S.C. §3304 5 C.F.R. §335.106 |

Authorizes veterans to apply for positions in the competitive service that are not open to the general public. Thus, veterans compete with current or former federal employees and may be competitively or noncompetitively appointed depending on the agency and position. The authority does not provide veterans with any selection priority over other qualified applicants. All veterans who are eligible for veterans' preference are eligible for VEOA. |

|

33. 30% or More Disabled Veterans |

5 U.S.C. §3112 5 C.F.R. §315.707 |

Authorizes agencies to noncompetitively appoint to a position in the competitive service a veteran with a compensable service-connected disability of 30% or more at any grade level for up to 60 days. An agency may convert the veteran to a career or career-conditional employee during the appointment. |

|

34. Noncompetitive Appointment of Certain Military Spouses |

September 30, 2008 E.O. 13473 5 U.S.C. §3330d 5 C.F.R. §315.612 |

Authorizes agencies to noncompetitively appoint a military spouse to a position in the competitive service who is: (1) relocating with an armed forces member on active duty to a new duty station via a permanent change of station, (2) married to a 100% disabled service member injured while on active duty, or (3) a widow or widower of a service member who was killed on active duty. The authority does not provide military spouses with any selection priority over other qualified applicants. |

|

35. Schedule A authority for Family Members of Active Duty Military and Civilians Stationed in Foreign Areas |

5 C.F.R. §315.608 |

Authorizes executive branch agencies to noncompetitively appoint to positions in the excepted service a spouse or family member who held a federal position overseas and accompanied a sponsor officially assigned to an overseas area. The individual must have received a fully successful or better performance rating and must apply within three years of returning from overseas. |

|

36. Schedule A hiring authority for Fellowship and Similar Appointments in the Excepted Service |

5 CFR §213.3102(r) |