DHS Appropriations FY2017: Research and Development, Training, and Services

This report is part of a suite of reports that discuss appropriations for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for FY2017. It specifically discusses appropriations for the components of DHS included in the fourth title of the homeland security appropriations bill—in past years, this has comprised U.S. Citizenship and Naturalization Services, the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, the Science and Technology Directorate, and the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO). In FY2017, the Administration proposed moving the Domestic Nuclear Detection office into a new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office, along with several other parts of DHS. Congress has labeled this title of the bill in recent years as “Research and Development, Training, and Services.”

The report provides an overview of the Administration’s FY2017 request for these components, and the appropriations proposed by the Senate and House appropriations committees in response. Rather than limiting the scope of its review to the fourth title of the bills, the report includes information on provisions throughout the bills and report that directly affect these components.

Research and Development, Training, and Services is the second smallest of the four titles that carry the bulk of the funding in the bill. The Administration requested $1.63 billion for these components in FY2017, $133 million (8.9%) more than was provided for FY2016. The amount requested for these components is 3.4% of the Administration’s $47.7 billion request for net discretionary budget authority and disaster relief funding for DHS.

Contributing to the increase in the request was its proposal to consolidate several parts of DHS funded in other titles with DNDO into a new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office, funded in Title IV.

Senate Appropriations Committee-reported S. 3001 would have provided the components included in this title $1.50 billion in net discretionary budget authority. This would have been $132 million (8.1%) less than requested, and less than $1 million (<0.1%) more than was provided in FY2016.

House Appropriations Committee-reported H.R. 5634 would have provided the components included in this title $1.63 billion in net discretionary budget authority. This would have been $1 million (0.1%) more than requested, and $134 million (9.0%) more than was provided in FY2016.

On September 29, 2016, the President signed into law P.L. 114-223, which contained a continuing resolution that funds the government at the same rate of operations as FY2016, minus 0.496% through December 9, 2017. A second continuing resolution was signed into law on December 10, 2016 (P.L. 114-254), funding the government at the same rate of operations as FY2016, minus 0.1901%, through April 28, 2017. For details on the continuing resolution and its impact on DHS, see CRS Report R44621, Department of Homeland Security Appropriations: FY2017, which also includes additional information on the broader subject of FY2017 funding for DHS as well as links to analytical overviews and details regarding components in other titles.

This report will be updated once the annual appropriations process for DHS for FY2017 is concluded.

DHS Appropriations FY2017: Research and Development, Training, and Services

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Note on Data and Citations

- The "Common Appropriations Structure"

- Summary of DHS Appropriations

- Research and Development, Training, and Services

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

- Summary of Appropriations

- Issues in USCIS Appropriations

- E-Verify

- Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC)

- Summary of Appropriations

- Issues in FLETC Appropriations

- Workforce Issues

- Active Shooter Response Training

- Directorate of Science and Technology (S&T)

- Summary of Appropriations

- Issues in S&T Appropriations

- National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility (NBAF)

- Identifying and Coordinating DHS R&D

- Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office (CBRNE)

- Summary of Appropriations

- Issues in CBRNE Office Appropriations

- Create a New Organizational Structure?

- BioWatch

Summary

This report is part of a suite of reports that discuss appropriations for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for FY2017. It specifically discusses appropriations for the components of DHS included in the fourth title of the homeland security appropriations bill—in past years, this has comprised U.S. Citizenship and Naturalization Services, the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, the Science and Technology Directorate, and the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO). In FY2017, the Administration proposed moving the Domestic Nuclear Detection office into a new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office, along with several other parts of DHS. Congress has labeled this title of the bill in recent years as "Research and Development, Training, and Services."

The report provides an overview of the Administration's FY2017 request for these components, and the appropriations proposed by the Senate and House appropriations committees in response. Rather than limiting the scope of its review to the fourth title of the bills, the report includes information on provisions throughout the bills and report that directly affect these components.

Research and Development, Training, and Services is the second smallest of the four titles that carry the bulk of the funding in the bill. The Administration requested $1.63 billion for these components in FY2017, $133 million (8.9%) more than was provided for FY2016. The amount requested for these components is 3.4% of the Administration's $47.7 billion request for net discretionary budget authority and disaster relief funding for DHS.

Contributing to the increase in the request was its proposal to consolidate several parts of DHS funded in other titles with DNDO into a new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office, funded in Title IV.

Senate Appropriations Committee-reported S. 3001 would have provided the components included in this title $1.50 billion in net discretionary budget authority. This would have been $132 million (8.1%) less than requested, and less than $1 million (<0.1%) more than was provided in FY2016.

House Appropriations Committee-reported H.R. 5634 would have provided the components included in this title $1.63 billion in net discretionary budget authority. This would have been $1 million (0.1%) more than requested, and $134 million (9.0%) more than was provided in FY2016.

On September 29, 2016, the President signed into law P.L. 114-223, which contained a continuing resolution that funds the government at the same rate of operations as FY2016, minus 0.496% through December 9, 2017. A second continuing resolution was signed into law on December 10, 2016 (P.L. 114-254), funding the government at the same rate of operations as FY2016, minus 0.1901%, through April 28, 2017. For details on the continuing resolution and its impact on DHS, see CRS Report R44621, Department of Homeland Security Appropriations: FY2017, which also includes additional information on the broader subject of FY2017 funding for DHS as well as links to analytical overviews and details regarding components in other titles.

This report will be updated once the annual appropriations process for DHS for FY2017 is concluded.

Introduction

This report is part of a suite of reports that discuss appropriations for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for FY2017. It specifically discusses appropriations for the components of DHS included in the fourth title of the homeland security appropriations bill—in past years, this has been U.S. Citizenship and Naturalization Services (USCIS), the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC), the Science and Technology Directorate (S&T), and the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO). In FY2017, the Administration proposed moving the Domestic Nuclear Detection office into a new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office (CBRNEO), along with several other parts of DHS. Congress has labeled this title of the bill in recent years as "Research and Development, Training, and Services."

The report provides an overview of the Administration's FY2017 request for Research and Development, Training, and Services, and the appropriations proposed by the Senate and House appropriations committees in response. Rather than limiting the scope of its review to the fourth title of the bills, the report includes information on provisions throughout the bills and report that directly affect these components.

The suite of CRS reports on homeland security appropriations tracks legislative action and congressional issues related to DHS appropriations, with particular attention paid to discretionary funding amounts. The reports do not provide in-depth analysis of specific issues related to mandatory funding—such as retirement pay—nor do they systematically follow other legislation related to the authorization or amending of DHS programs, activities, or fee revenues.

Discussion of appropriations legislation involves a variety of specialized budgetary concepts. The Appendix to CRS Report R44621, Department of Homeland Security Appropriations: FY2017 explains several of these concepts, including budget authority, obligations, outlays, discretionary and mandatory spending, offsetting collections, allocations, and adjustments to the discretionary spending caps under the Budget Control Act (P.L. 112-25). A more complete discussion of those terms and the appropriations process in general can be found in CRS Report R42388, The Congressional Appropriations Process: An Introduction, by Jessica Tollestrup and James V. Saturno, and the Government Accountability Office's A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process.1

Note on Data and Citations

Except in summary discussions and when discussing total amounts for the bill as a whole, all amounts contained in the suite of CRS reports on homeland security appropriations represent budget authority and are rounded to the nearest million. However, for precision in percentages and totals, all calculations were performed using unrounded data.

Data used in this report for FY2016 amounts are derived from two sources. Normally, this report would rely on P.L. 114-113, the Omnibus Appropriations Act, 2016—Division F of which is the Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2016—and the accompanying explanatory statement published in Books II and III of the Congressional Record for December 17, 2015. However, due to the implementation of the Common Appropriations Structure for DHS (see below), additional information is drawn from H.Rept. 114-668, which presents the FY2016 enacted funding in the new structure. H.Rept. 114-668 also serves as the primary source for the FY2016 enacted funding levels, the FY2017 requested funding levels, and the House Appropriations Committee recommendation in the new structure. S.Rept. 114-264 serves as the primary source for the FY2016 enacted funding levels, the FY2017 requested funding levels, and Senate Appropriations Committee recommendation in the "legacy structure"—the overall structure of appropriations enacted for FY2016.

The two appropriations committees took different approaches not only with the Common Appropriations Structure, but also with the Administration's proposed establishment of the new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office—the Senate Appropriations Committee rejected the reorganization, while the House did not. Readers should bear that in mind while making comparisons of funding levels for DNDO or CBRNEO, or funding comparisons by title of the bill.

The "Common Appropriations Structure"2

Section 563 of Division F of P.L. 114-113 (the FY2016 Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act) provided authority for DHS to submit its FY2017 appropriations request under the new common appropriations structure (CAS), and implement it in FY2017. Under the act, the new structure was to have four categories of appropriations:

- Operations and Support;

- Procurement, Construction, and Improvement;

- Research and Development; and

- Federal Assistance.3

Most of the FY2017 DHS appropriations request categorized its appropriations in this fashion. The exception was the Coast Guard, which was in the process of migrating its financial information to a new system. DHS has also proposed realigning its Programs, Projects, and Activities (PPA) structure—the next level of funding detail below the appropriation level—possibly trying to align PPAs into a mission-based hierarchy.

The House Appropriations Committee made its funding recommendation using the CAS (although it chose to implement it slightly differently than the Administration had envisioned in Title I), but the Senate Appropriations Committee did not, instead drafting its annual DHS appropriations bill and report using the same structure as was used in FY2016. It remains to be seen how differences between the House and Senate structures will be worked out in the legislation which finalizes FY2017 appropriations levels for DHS. Some individual programmatic comparisons are possible between the two bills, and the Coast Guard's appropriations are comparable as its FY2017 funding was not proposed in the CAS structure. However, no authoritative crosswalk between the House Appropriations Committee proposal in the CAS structure and Senate Appropriations Committee proposal in the legacy structure is publicly available.

Summary of DHS Appropriations

Generally, the homeland security appropriations bill includes all annual appropriations provided for DHS, allocating resources to every departmental component. Discretionary appropriations4 provide roughly two-thirds to three-fourths of the annual funding for DHS operations, depending how one accounts for disaster relief spending and funding for overseas contingency operations. The remainder of the budget is a mix of fee revenues, trust funds, and mandatory spending.5

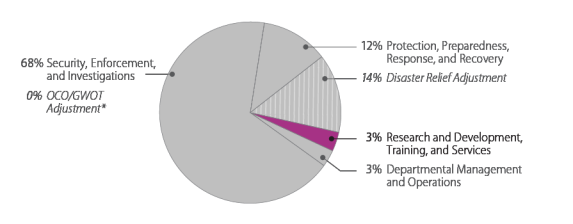

Appropriations measures for DHS typically have been organized into five titles.6 The first four are thematic groupings of components: Departmental Management and Operations; Security, Enforcement, and Investigations; Protection, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery; and Research and Development, Training, and Services. A fifth title contains general provisions, the impact of which may reach across the entire department, impact multiple components, or focus on a single activity.

The following pie chart presents a visual comparison of the share of annual appropriations requested for the components funded in each of the first four titles, highlighting the components discussed in this report.

Research and Development, Training, and Services

The Research and Development, Training, and Services (Title IV) of the DHS appropriations bill is the second smallest of the four titles that carry the bulk of the funding in the bill. In FY2016, Title IV included USCIS, FLETC, DNDO, and S&T. The Administration requested $1.63 billion in FY2017 net discretionary budget authority for components included in this title, as part of a total budget for these components of $5.52 billion for FY2017. The appropriations request was $133 million (8.9%) more than was provided for FY2016.

Part of the reason for the requested growth in Title IV was the inclusion of the Administration's newly proposed CBRNEO in this title, which incorporated DNDO, as well as the Office of Health Affairs and part of the National Protection and Programs Directorate from Title III, and part of the Office of Policy from Title I. Together, this represented a transfer of components funded at over $140 million in FY2016 in other titles of the bill into Title IV.

Senate Appropriations Committee-reported S. 3001 would have provided the components included in this title $1.50 billion in net discretionary budget authority. This would have been $132 million (8.1%) less than requested, and less than $1 million (<0.1%) more than was provided in FY2016. It did not include the reorganization to form CBRNEO, or funding for the new office.

House Appropriations Committee-reported H.R. 5634 would have provided the components included in this title $1.63 billion in net discretionary budget authority. This would have been $1 million (0.1%) more than requested, and $134 million (9.0%) more than was provided in FY2016. The House bill included funding for the new CBRNEO.

These bills were not voted on in either body, and no annual appropriations bill for DHS was enacted prior to the end of FY2016. On September 29, 2016, the President signed into law P.L. 114-223, which contained a continuing resolution that funds the government at the same rate of operations as FY2016, minus 0.496%, through December 9, 2017. A second continuing resolution was signed into law on December 10, 2016 (P.L. 114-254), funding the government at the same rate of operations as FY2016, minus 0.1901%, through April 28, 2017. For details on the continuing resolution and its impact on DHS, see CRS Report R44621, Department of Homeland Security Appropriations: FY2017.

Table 1 lists the enacted funding level for the individual components funded under the Research and Development, Training, and Services title for FY2016, as well as the amounts requested for these accounts for FY2017 by the Administration, and proposed by the Senate and House appropriations committees. The table includes information on funding under Title IV as well as other provisions in the bill.

Table 1. Budgetary Resources for Research and Development, Training, and Services Components

(budget authority in millions of dollars)

|

Component |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

||||||

|

Enacted |

Request |

Senate Committee Reported S. 3001 |

House Committee Reported H.R. 5634 |

|||||

|

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services |

||||||||

|

Title IV Appropriation |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Appropriation (includes the impact of any General Provisions) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Fees, Mandatory Spending, and Trust Funds |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Budgetary Resources |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Federal Law Enforcement Training Center |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Title IV Appropriation |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Appropriation (includes the impact of any General Provisions) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Fees, Mandatory Spending, and Trust Funds |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Budgetary Resources |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Science & Technology Directorate |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Title IV Appropriation |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Appropriation (includes the impact of any General Provisions) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Fees, Mandatory Spending, and Trust Funds |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Budgetary Resources |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Domestic Nuclear Detection Office |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Title IV Appropriation |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Appropriation (includes the impact of any General Provisions) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Fees, Mandatory Spending, and Trust Funds |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Budgetary Resources |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Title IV Appropriation |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Appropriation (includes the impact of any General Provisions) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Fees, Mandatory Spending, and Trust Funds |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Budgetary Resources |

|

|

|

|

||||

Source: CRS analysis of Division F of P.L. 114-113 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of December 17, 2015, pp. H10161-H10210; S. 3001 and S.Rept. 114-264; and H.R. 5634 and H.Rept. 114-668.

Notes: Table displays rounded numbers, but all operations were performed with unrounded data. Amounts, therefore, may not sum to totals. Fee revenues included in the "Fees, Mandatory Spending, and Trust Funds" lines are projections, and do not include budget authority provided through general provisions.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services7

Three activities dominate the work of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS): (1) processing and adjudication of all immigration applications and petitions, including family-based petitions, employment-based petitions, nonimmigrant change of status petitions, work authorizations, and travel documents; (2) adjudication of naturalization petitions for legal permanent residents to become citizens; and (3) consideration of refugee and asylum claims, and related humanitarian and international concerns.

USCIS funds the processing and adjudication of immigrant, nonimmigrant, refugee, asylum, and citizenship benefits largely through its fee revenues deposited into the Immigration Examinations Fee Account.8 In the last decade, the agency has received annual appropriations from the Treasury that have been directed largely towards specific projects such as reducing petition processing backlogs and operating the E-Verify program.9 The agency receives most of its revenue from adjudication fees of immigration benefit applications and petitions.10

Summary of Appropriations

The Administration requested $129 million in appropriations for USCIS for FY2017, including $119 million for the E-Verify program and $10 million for the Immigrant Integration Initiative. Together with $3,889 million in projected fee collections, the request projected $4,018 million in new gross budget authority for USCIS. Of this FY2017 amount, $3,234 million was to fund adjudication services, which included $274 million for asylum, refugee, and international operations and $226 million for digital conversion of immigrant records ("Business Transformation"). Apart from adjudication services, $139 million was to fund information and customer services, $419 million was to fund administration expenses, and $37 million was to fund the Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) program.11

Senate Appropriations Committee-reported S. 3001 recommended that USCIS receive a gross budget authority for FY2016 of $3,625 million, $393 million below the $4,018 million requested. The bill included $119 million in appropriations for USCIS's E-Verify Program, and as in previous years, provided that USCIS could expend up to $10 million of fee revenue for immigrant integration grants, rather than providing an appropriation for the program. Within the total fees collected, the committee directed USCIS to provide at least $29 million to continue converting paper immigration records to a digital format.

The Senate Appropriations Committee-reported bill directed that USCIS appropriations not be used by the agency to grant immigration benefits to an individual unless USCIS had received the results of a criminal background check and that the results did not preclude the granting of the benefit. The bill also directed that none of the funds made available to USCIS for immigrant integration grants be used to provide services to aliens who had not been lawfully admitted for permanent residence.

The bill prohibited appropriations from funding either the process or approval of a competition for privately-provided services under Office and Management and Budget Circular A-7612 for the following employee occupation titles: Immigration Information Officers, Immigration Service Analysts, Contact Representatives, Investigative Assistants, or Immigration Services Officers.

House-reported H.R. 5634 also recommended that USCIS receive a gross budget authority for FY2017 at $3,625 million, $393 million below the amount requested. The bill included $119 million in appropriations for USCIS. Like the Senate-reported bill, it only provided appropriations for the E-Verify Program, and provided that USCIS could expend up to $10 million of fee revenue for immigrant integration grants, rather than providing an appropriation for the program. The bill also permitted USCIS to solicit, accept, administer, and utilize gifts and property donations for the purpose of providing grants to promote citizenship and immigrant integration, provided that such funds are deposited into a separate "Citizenship Gift and Bequest Account."

The House-reported bill prohibited any funds, resources, or fees made available to DHS or to any other federal agency, including deposits to the Immigration Examination Fee Account from being used to expand the existing Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) or the proposed Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) as were outlined in memoranda that formed part of the President's Immigration Accountability Executive Action of November 20, 2014, while the current district court injunction on the expansion of DACA and creation of DAPA remains in effect.13

Like the Senate-reported bill, the House-reported bill specified that USCIS appropriations could not be used by the agency to grant immigration benefits to an individual unless USCIS had received the results of a criminal background check and the results did not preclude the granting of the benefit. The bill also specified that none of the funds made available to USCIS for immigrant integration grants could be used to provide services to aliens who had not been lawfully admitted for permanent residence.

The House-reported bill also included the same prohibition as the Senate-reported bill on funding the process or approval of a competition for privately-provided services for certain USCIS employee occupations.

Issues in USCIS Appropriations

E-Verify

One potential issue for Congress was ongoing concerns about the accuracy of the E-Verify system. E-Verify helps employers ascertain whether their employees have the requisite legal status and work authorization to work lawfully in the United States.14 E-Verify use by employers has increased substantially from under 25,000 employers in FY2007 to over 650,000 in FY2016. The Senate committee report expressed support for DHS efforts to improve E-Verify effectiveness and accuracy across intended uses and also acknowledged increases in the number of employers utilizing E-Verify, and directed USCIS to include national-level E-Verify utilization statistics on its website, including the number and percentage of employers using E-Verify by state, adoption rates by industry, and the number of cases processed each year. The House committee report expressed support for the agency's efforts to have the accuracy of E-Verify independently reviewed.

Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC)15

The Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) provides basic and advanced law enforcement instruction to 91 federal entities with law enforcement responsibilities. FLETC also provides specialized training to state and local law enforcement entities, campus police forces, law enforcement organizations of Native American tribes, and international law enforcement agencies. By training officers in a multi-agency environment, FLETC intends to promote consistency and collaboration across its partner organizations. FLETC administers four training sites throughout the United States, but also uses online training and provides training at other locations when its specialized facilities are not needed. FLETC employs approximately 1,100 personnel.

Summary of Appropriations

For FY2017, the Administration requested $243 million in discretionary budget authority for FLETC. This was $3 million (1.0%) less than was provided in FY2016.

Both Senate Appropriations Committee-reported S. 3001 and House Appropriations Committee-reported H.R. 5634 included the requested funding level for FLETC.

Issues in FLETC Appropriations

Workforce Issues

The Senate Appropriations Committee report noted that there have been retirements from FLETC's senior leadership, and turnover among its instructional staff. The report endorsed direct hire authority for FLETC, as well as recommending that they "continue to pursuing timely hiring campaigns."16 The House Appropriations Committee report encouraged FLETC to conduct a review of the pay and benefits of its workforce, and recommend to Congress any authorities they may need to provide the compensation needed to recruit and retain a workforce with the requisite skills and experience needed to support FLETC's mission.17

Active Shooter Response Training

Both House and Senate Committee reports expressed support for ongoing efforts at FLETC to address the threat posed by active shooters. The reports noted that FLETC is evaluating active shooter response technology and directs them to coordinate with the Science and Technology Directorate's Counter Terrorism Technology Evaluation Center to assess the technologies and how they might be integrated into training programs.18

Directorate of Science and Technology (S&T)19

The S&T Directorate is the primary DHS organization for research and development (R&D). Led by a Senate-confirmed Under Secretary for Science and Technology, it performs R&D in several laboratories of its own and funds R&D performed by the Department of Energy national laboratories, industry, universities, and others. It also conducts testing and other technology-related activities in support of other DHS components.

Summary of Appropriations

For FY2017, the Administration requested $759 million in discretionary budget authority for the S&T Directorate. This was $28 million (4%) less than was provided in FY2016. Within the S&T total, funding for Research, Development, and Innovation would have decreased by $18 million (4%) from the comparable FY2016 amount. Funding for some individual R&D topics would have increased or decreased by substantially larger percentages. For example, R&D on border security technologies would have increased by 71%, while R&D on detection of explosives and bioagents would have decreased by 31% and 28% respectively. Funding for University Programs, which primarily funds the S&T Directorate's university centers of excellence, would have decreased by almost $9 million (21%).

As reported by the Senate Appropriations Committee, S. 3001 included $790 million in discretionary budget authority for S&T. This was $31 million (4%) more than was requested by the Administration and $2.8 million (less than 1%) more than was provided in FY2016. The committee's recommendation for Research, Development, and Innovation was $22 million more than the request and $4 million more than the FY2016 amount. Its recommendation for University Programs was $9 million more than the request and almost $1 million more than the FY2016 amount.

As reported by the House Appropriations Committee, H.R. 5634 included $767 million in discretionary budget authority for S&T. This was $9 million (1%) more than was requested by the Administration, $20 million (2%) less than was provided in FY2016, and $22 million (3%) less than was proposed in the Senate committee-reported bill. The House committee's recommendation for Research, Development, and Innovation was the same as the Administration's request. Its recommendation for University Programs was almost $9 million more than the request and nearly the same as the FY2016 amount.

Issues in S&T Appropriations

National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility (NBAF)

The Administration's request for S&T included no further funding for the ongoing construction of the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility (NBAF). An appropriation of $300 million for this project in FY2015 completed its planned construction budget. The request did include funds in S&T's proposed Operations and Support account for NBAF operational stand-up activities. The House and Senate committee recommendations both included the requested NBAF operational stand-up funding and expressed interest in how the facility will be managed. The Senate report directed DHS and the Department of Agriculture to work together on a plan for future NBAF operations, "including consideration of the appropriate agency to manage the facility." The House report directed S&T to keep the committee informed on whether NBAF will be operated by the government or a contractor.

Identifying and Coordinating DHS R&D

When Congress established DHS in the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-296), it established the S&T Directorate to be the new department's primary organization for R&D.20 At the same time, it explicitly allowed other DHS components to carry out R&D themselves, "as long as such activities are coordinated through the Under Secretary for Science and Technology."21 Identifying and coordinating the R&D activities of other DHS components has been challenging, both for Congress and for DHS itself.

In September 2012, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that although the S&T Directorate, DNDO, and the Coast Guard were the only DHS components that reported R&D activities to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), several other DHS components also funded R&D and activities related to R&D.22 The GAO report found that DHS lacked department-wide policies to define R&D and guide reporting of R&D activities, and as a result, DHS did not know the total amount its components invest in R&D. The report recommended that DHS develop policies and guidance for defining, reporting, and coordinating R&D activities across the department, and that DHS establish a mechanism to track R&D projects.

DHS has made some progress on this issue. In the FY2013 and FY2014 appropriations cycles, Congress responded to GAO's findings by directing DHS to develop new policies and procedures. In September 2014, GAO testified that DHS had updated its guidance to include a definition of R&D, and that efforts to develop a process for coordinating R&D across the department were ongoing though not yet complete.23 In April 2015, GAO's annual report on fragmented, overlapping, or duplicative federal programs stated that its concerns about DHS R&D had been "partially addressed."24 In December 2015, however, the explanatory statement for the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) stated that:

The Department lacks a mechanism for capturing and understanding research and development (R&D) activities conducted across DHS, as well as coordinating R&D to reflect departmental priorities.25

The proposed Common Appropriations Structure includes Research and Development as one of its standardized account titles. Although this change might contribute to identifying R&D activities in each DHS component, it seems unlikely to resolve ongoing concerns about coordination and prioritization.

The House and Senate committee reports for FY2017 did not explicitly address this issue.

Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office (CBRNE)26

The President's budget request proposed consolidating several offices and activities into a new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office. This new office would contain the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO); the Office of Health Affairs (OHA); the CBRNE threat awareness and risk assessment activities of the Science and Technology Directorate; the CBRNE functions of the Office of Policy and the Office of Operations Coordination; and the Office of Bombing Prevention from the National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD).

On December 10, 2015, the House passed H.R. 3875, The Department of Homeland Security CBRNE Defense Act of 2015. This act would restructure the DHS CBRNE activities consistent with the structure in the budget proposal. The Senate has not passed a similar bill. Under H.R. 3875, the new office would be headed by an Assistant Secretary and have the mission "to coordinate, strengthen, and provide chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosives (CBRNE) capabilities in support of homeland security."27

The House appropriation bill followed the structure of the President's request and H.R. 3875, whereas the Senate bill was consistent with the current DHS structure.

Summary of Appropriations

For FY2017, the Administration requested $501 million in discretionary budget authority for the new CBRNE Office. According to the DHS budget justification, this is $29 million (6.1%) more than was provided in FY2016 for comparable activities in DNDO, OHA, and other components in the department.28

S. 3001, as reported by the Senate Appropriations Committee, did not fund the proposed CBRNE Office. Rather, it recommended funding levels for components as organized in the current DHS structure. It included $348 million in discretionary budget authority for DNDO. This is $1 million (0.3%) more than was provided in FY2016 and according to the Senate Committee Report, it is $6.2 million (1.8%) less than the Administration's request for comparable activities.29 S. 3001 also included $108 million in discretionary budget authority for OHA. This is $17 million (13.6%) less than was provided in FY2016 and according to the Senate Committee Report, it is $12 million (10.0%) less than the Administration's request for comparable activities.30

H.R. 5634, as reported by the House Appropriations Committee, included $504 million in discretionary budget authority for the CBRNE Office. This is $3 million (0.6%) more than was requested by the Administration, and $31 million (6.6%) more than was provided for comparable activities in FY2016.31

Issues in CBRNE Office Appropriations

Create a New Organizational Structure?

In 2013, Congress directed DHS to review its programs relating to chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats and to evaluate "potential improvements in performance and possible savings in costs that might be gained by consolidation of current organizations and missions, including the option of merging functions of the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO) and the Office of Health Affairs (OHA)."32 The report of this review was completed in June 2015. In July 2015, DHS officials testified that DHS plans to consolidate DNDO, OHA, and smaller elements of several other DHS programs into a new office, led by a new Assistant Secretary, with responsibility for DHS-wide coordination of chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosives "strategy, policy, situational awareness, threat and risk assessments, contingency planning, operational requirements, acquisition formulation and oversight, and preparedness."33 The President's FY2017 budget request reflected this reorganization. The House passed H.R. 3875, the Department of Homeland Security CBRNE Defense Act of 2015, which would restructure the DHS CBRNE activities consistent with the structure in the budget request. The Senate has not passed a similar bill.

Proponents of such a reorganization suggest that consolidating CBRNE activities would create a stronger focus within the department and improve interagency and interdepartmental coordination for these activities. However, skeptics of reorganization have questioned whether the benefits would outweigh the cost of disrupting current efforts, how well the differing agency cultures and missions would mesh, and why the new office would conduct research and development for nuclear defense but not biodefense.34

BioWatch

The BioWatch program deploys sensors in more than 30 U.S. cities to detect the possible aerosol release of a bioterrorism pathogen, in order that medications could be distributed before exposed individuals became ill. Operation of BioWatch accounts for most of OHA's budget. The program had sought for several years to deploy more sophisticated autonomous sensors that could detect airborne pathogens in a few hours, rather than the day or more that is currently required. However, after several years of unsuccessful efforts to procure a replacement for the existing system, DHS announced the termination of further procurement activities in April 2014.35

The Administration requested $82 million for BioWatch, approximately the same amount as was provided in FY2016. The Senate committee recommended $12 million (14.6%) less than the requested amount for BioWatch for FY2017. It recommended redirecting this $12 million to the S&T Directorate to "speed the development of a new bio-detection technology" rather than funding the "recapitalization, training, and other support activities of the current system."36

The House committee recommended providing the requested amounts for BioWatch for FY2017, including $1 million to support the replacement and recapitalization of current generation BioWatch equipment. However, the committee expressed concern about the effectiveness of the current system and DHS progress towards improving this system. The committee directed DHS to "more clearly articulate future technology requirements for the program to the private sector and innovators who are being called upon to help address those needs."37

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process, GAO-05-734SP, September 1, 2005, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-05-734SP. |

| 2. |

A more complete analysis of the history and impact of the Common Appropriations Structure proposal is available in CRS Report R44621, Department of Homeland Security Appropriations: FY2017. |

| 3. |

Sec. 563, Division F, P.L. 114-113. |

| 4. |

Generally speaking, those provided through annual appropriations legislation. |

| 5. |

A detailed analysis of this breakdown between discretionary appropriations and other funding is available in CRS Report R44052, DHS Budget v. DHS Appropriations: Fact Sheet, by William L. Painter. |

| 6. |

Although the House and Senate generally produce symmetrically structured bills, this is not always the case. Additional titles are sometimes added by one of the chambers to address special issues. For example, the FY2012 House full committee markup added a sixth title to carry a $1 billion emergency appropriation for the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF). The Senate version carried no additional titles beyond the five described above. For FY2016, the House- and Senate-reported versions of the DHS appropriations bill were generally symmetrical. |

| 7. |

This section was prepared by William Kandel, Analyst in Immigration Policy, Domestic Social Policy Division. |

| 8. |

Section 286 of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. §1356. There are two other fee accounts at USCIS, known as the H-1B Nonimmigrant Petitioner Account and the Fraud Prevention and Detection Account. The revenues in these accounts are drawn from separate fees that are statutorily determined (P.L. 106-311 and P.L. 109-13, respectively). USCIS receives 5% of the H-1B Nonimmigrant Petitioner Account revenues and 33% of the Fraud Detection and Prevention Account revenues. Department of Homeland Security, Congressional Budget Justification FY2017: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, H-1B Nonimmigrant Petitioner Account and Fraud Prevention and Detection Account (Washington, DC, 2016). |

| 9. |

E-verify allows employers to electronically confirm that prospective and current employees possess legal authorization to work in the United States. See CRS Report R40446, Electronic Employment Eligibility Verification, by Andorra Bruno. |

| 10. |

For more on USCIS fees, see CRS Report R44038, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Functions and Funding, by William A. Kandel. |

| 11. |

For more information on the SAVE program, see archived CRS Report R40889, Noncitizen Eligibility and Verification Issues in the Health Care Reform Legislation, by Ruth Ellen Wasem. |

| 12. |

The A-76 circular establishes federal policy for the competition of commercial activities. |

| 13. |

For more information on DACA, DAPA, and the content and status of the President's executive action, see CRS Report R43852, The President's Immigration Accountability Executive Action of November 20, 2014: Overview and Issues, coordinated by William A. Kandel. |

| 14. |

See CRS Report R40446, Electronic Employment Eligibility Verification, by Andorra Bruno. |

| 15. |

Prepared by William L. Painter, Specialist in Emergency Management and Homeland Security Policy, Government and Finance Division. |

| 16. |

S.Rept. 114-264, p. 126. |

| 17. |

H.Rept. 114-668, p. 82. |

| 18. |

S.Rept. 114-264, pp. 126-127; H.Rept. 114-668, p. 82. |

| 19. |

Prepared by Daniel Morgan, Specialist in Science and Technology Policy, Resources, Science, and Industry Division. |

| 20. |

P.L. 107-296, Sec. 302, item (11). |

| 21. |

P.L. 107-296, Sec. 306(b). |

| 22. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Department of Homeland Security: Oversight and Coordination of Research and Development Should Be Strengthened, GAO-12-837, September 12, 2012. |

| 23. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Department of Homeland Security: Actions Needed to Strengthen Management of Research and Development, GAO-14-865T, September 9, 2014. |

| 24. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2015 Annual Report: Additional Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve Other Financial Benefits, GAO-15-404SP, April 2015. |

| 25. |

Congressional Record, December 17, 2015, p. H10162. |

| 26. |

Prepared by Frank Gottron, Specialist in Science and Technology Policy, Resources, Science, and Industry Division. |

| 27. | |

| 28. |

DHS, CBRNE Office Budget Overview Congressional Justification FY2017, p. CBRNE-2. |

| 29. |

S.Rept. 114-264, p. 132. |

| 30. |

S.Rept. 114-264, p. 104. |

| 31. |

DHS, CBRNE Office Budget Overview Congressional Justification FY2017, p. CBRNE-2. |

| 32. |

Explanatory statement on the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2013 (P.L. 113-6), Congressional Record, March 11, 2013, p. S1547. |

| 33. |

Joint prepared testimony of Reginald Brothers, Under Secretary for Science and Technology, Kathryn H. Brinsfield, Assistant Secretary for Health Affairs and Chief Medical Officer, and Huban A. Gowadia, Director of the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office, Department of Homeland Security, before the House Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittees on Emergency Preparedness, Response, and Communications and Cybersecurity, Infrastructure Protection, and Security Technologies, July 14, 2015, http://homeland.house.gov/hearing/joint-subcommittee-hearing-weapons-mass-destruction-bolstering-dhs-combat-persistent-threats. |

| 34. |

Biodefense research and development would remain in the Science and Technology Directorate. See House Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittees on Emergency Preparedness, Response, and Communications and Cybersecurity, Infrastructure Protection, and Security Technologies, July 14, 2015, http://homeland.house.gov/hearing/joint-subcommittee-hearing-weapons-mass-destruction-bolstering-dhs-combat-persistent-threats. |

| 35. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Biosurveillance: Observations on the Cancellation of BioWatch Gen-3 and Future Considerations for the Program, GAO-14-267T, June 10, 2014, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-267T. |

| 36. |

S.Rept. 114-264, p. 104. |

| 37. |

H.Rept. 114-668, p. 88. |