What Does the Gig Economy Mean for Workers?

The gig economy is the collection of markets that match providers to consumers on a gig (or job) basis in support of on-demand commerce. In the basic model, gig workers enter into formal agreements with on-demand companies (e.g., Uber, TaskRabbit) to provide services to the company’s clients. Prospective clients request services through an Internet-based technological platform or smartphone application that allows them to search for providers or to specify jobs. Providers (i.e., gig workers) engaged by the on-demand company provide the requested service and are compensated for the jobs.

Recent trends in on-demand commerce suggest that gig workers may represent a growing segment of the U.S. labor market. In response, some Members of Congress have raised questions, for example, about the size of the gig workforce, how workers are using gig work, and the implications of the gig economy for labor standards and livelihoods more generally.

With some exceptions, on-demand companies view providers as independent contractors (i.e., not employees) using the companies’ platforms to obtain referrals and transact with clients. This designation is frequently made explicit in the formal agreement that establishes the terms of the provider-company relationship. In some ways, the gig economy can be viewed as an expansion of traditional freelance work (i.e., self-employed workers who generate income through a series of jobs and projects).

However, gig jobs may differ from traditional freelance jobs in a few ways. For example, coordination of jobs through an on-demand company reduces entry and operating costs for providers and allows workers’ participation to be more transitory in gig markets (i.e., they have greater flexibility around work hours). The terms placed around providers’ use of some tech platforms may further set gig work apart. For example, some on-demand companies discourage providers from accepting work outside the platform from certain clients. This is a potentially important difference between gig work and traditional freelance work because it may limit the provider’s ability to build a client base and operate outside the platform.

Characterizing the gig economy workforce (i.e., those providing services brokered through tech-based platforms) is challenging along several fronts. To date, no large-scale official data have been collected, and there remains considerable uncertainty about how to best measure this segment of the labor force. Existing large-scale labor force survey data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the U.S. Census Bureau may provide some insights, but are imperfect proxy measures of contemporary gig economy participants. A small literature examines data collected by individual companies operating in the gig economy or from pockets of gig-economy workers. As such, these analyses can be viewed as snapshots of certain gig workers, but they are not necessarily representative of the full market.

The apparent availability of gig jobs and the flexibility they seem to provide workers are frequently touted features of the gig economy. However, to the extent that gig-economy workers are viewed as independent contractors, gig jobs differ from traditional employment in notable ways. First, whether a worker in the gig economy may be considered an employee rather than an independent contractor is significant for purposes of various federal labor and employment laws. In general, employees enjoy the protections and benefits provided by such laws, whereas independent contractors are not covered. Two laws, in particular, the Fair Labor Standards Act and the National Labor Relations Act, have drawn recent attention.

In addition, certain other benefits (e.g., paid sick leave, health insurance, retirement benefits) that are often associated with traditional employment relationships may not be available in the same form to workers in the gig economy. Should Congress choose to consider ways of increasing access to such benefits for nontraditional employees, new mechanisms, such as portable benefits or risk-pooling, could serve to provide benefits to workers in the gig economy.

What Does the Gig Economy Mean for Workers?

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- An Overview of the Gig Economy

- Measuring Gig Workers

- Related Federal Labor and Business Statistics

- Bureau of Labor Statistics Data: Contingent Workers, Alternative Employment Arrangements, and Self-Employment

- U.S. Census Bureau Data: Nonemployer Statistics

- Other Data Sources: Company Data and Small-Scale Surveys

- Broad Sample Studies

- Company Analysis: Uber Drivers

- Analysis of Independent Workers

- Are Workers Within the Gig Economy Employees or Independent Contractors?

- Federal Courts' Consideration of Gig Workers' Classification

- State Wage-Related Claims

- Gig Workers' Rights to Organize and Bargain Collectively

- Protections and Benefits for Gig Workers

- Employee Protections

- Voluntary Employer-Provided Benefits

- Considerations: Independent Contractors in the Gig Economy

Figures

Summary

The gig economy is the collection of markets that match providers to consumers on a gig (or job) basis in support of on-demand commerce. In the basic model, gig workers enter into formal agreements with on-demand companies (e.g., Uber, TaskRabbit) to provide services to the company's clients. Prospective clients request services through an Internet-based technological platform or smartphone application that allows them to search for providers or to specify jobs. Providers (i.e., gig workers) engaged by the on-demand company provide the requested service and are compensated for the jobs.

Recent trends in on-demand commerce suggest that gig workers may represent a growing segment of the U.S. labor market. In response, some Members of Congress have raised questions, for example, about the size of the gig workforce, how workers are using gig work, and the implications of the gig economy for labor standards and livelihoods more generally.

With some exceptions, on-demand companies view providers as independent contractors (i.e., not employees) using the companies' platforms to obtain referrals and transact with clients. This designation is frequently made explicit in the formal agreement that establishes the terms of the provider-company relationship. In some ways, the gig economy can be viewed as an expansion of traditional freelance work (i.e., self-employed workers who generate income through a series of jobs and projects).

However, gig jobs may differ from traditional freelance jobs in a few ways. For example, coordination of jobs through an on-demand company reduces entry and operating costs for providers and allows workers' participation to be more transitory in gig markets (i.e., they have greater flexibility around work hours). The terms placed around providers' use of some tech platforms may further set gig work apart. For example, some on-demand companies discourage providers from accepting work outside the platform from certain clients. This is a potentially important difference between gig work and traditional freelance work because it may limit the provider's ability to build a client base and operate outside the platform.

Characterizing the gig economy workforce (i.e., those providing services brokered through tech-based platforms) is challenging along several fronts. To date, no large-scale official data have been collected, and there remains considerable uncertainty about how to best measure this segment of the labor force. Existing large-scale labor force survey data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the U.S. Census Bureau may provide some insights, but are imperfect proxy measures of contemporary gig economy participants. A small literature examines data collected by individual companies operating in the gig economy or from pockets of gig-economy workers. As such, these analyses can be viewed as snapshots of certain gig workers, but they are not necessarily representative of the full market.

The apparent availability of gig jobs and the flexibility they seem to provide workers are frequently touted features of the gig economy. However, to the extent that gig-economy workers are viewed as independent contractors, gig jobs differ from traditional employment in notable ways. First, whether a worker in the gig economy may be considered an employee rather than an independent contractor is significant for purposes of various federal labor and employment laws. In general, employees enjoy the protections and benefits provided by such laws, whereas independent contractors are not covered. Two laws, in particular, the Fair Labor Standards Act and the National Labor Relations Act, have drawn recent attention.

In addition, certain other benefits (e.g., paid sick leave, health insurance, retirement benefits) that are often associated with traditional employment relationships may not be available in the same form to workers in the gig economy. Should Congress choose to consider ways of increasing access to such benefits for nontraditional employees, new mechanisms, such as portable benefits or risk-pooling, could serve to provide benefits to workers in the gig economy.

Introduction

Technological advancement and the proliferation of the smartphone have reshaped the commercial landscape, providing consumers new ways to access the retail marketplace. On-demand companies1 are one such innovation, and underpinning on-demand commerce is the gig economy,2 the collection of markets that match service providers to consumers of on-demand services on a gig (or job) basis.

Flagship on-demand companies such as Uber (driver services) and Handy (home cleaners and household services) have garnered significant media attention both for their market success and recent legal challenges, particularly concerning the classification of gig workers.3 Broader questions about the pros and cons of the gig economy have emerged as on-demand markets grow and the gig economy expands into new sectors. By some accounts, workers' willingness to participate in the gig economy provides evidence that gig work is a beneficial arrangement. Indeed, gig jobs may yield benefits relative to traditional employment in terms of the ease of finding employment and greater flexibility to choose jobs and hours. The gig economy may facilitate bridge employment (e.g., temporary employment between career jobs or between full-time work and retirement) or provide opportunities to generate income when circumstances do not accommodate traditional full-time, full-year employment. At the same time, however, the potential lack of labor protections for gig workers and the precarious nature of gig work have been met with some concern.

The nationwide reach of gig work and its potential to impact large groups of workers, and their livelihoods, have attracted the attention of some Members of Congress. These Members have raised questions about the size and composition of the gig workforce, the proper classification of gig workers (i.e., as employees or independent contractors), the potential for gig work to create work opportunities for unemployed or underemployed workers, and implications of gig work for worker protections and access to traditional employment-based benefits.

In support of these policy considerations, this report provides an overview of the gig economy and identifies legal and policy questions relevant to its workforce.

An Overview of the Gig Economy

The gig economy is the collection of markets that match providers to consumers on a gig (or job) basis in support of on-demand commerce. In the basic model, gig workers enter into formal agreements with on-demand companies to provide services to the company's clients. Prospective clients request services through an Internet-based technological platform or smartphone application that allows them to search for providers or to specify jobs. Providers (i.e., gig workers) engaged by the on-demand company provide the requested services and are compensated for the jobs.

Business models vary across companies that control tech platforms and their associated brands. Some companies allow providers to set prices or select the jobs that they take on (or both), whereas others maintain control over price-setting and assignment decisions.4 Some operate in local markets (e.g., select cities) while others serve a global client base. Although driver services (e.g., Lyft, Uber) and personal and household services (e.g., TaskRabbit, Handy) are perhaps best known, the gig economy operates in many sectors, including business services (e.g., Freelancer, Upwork), delivery services (e.g., Instacart, Postmates), and medical care (e.g., Heal, Pager).5

With some exceptions, on-demand companies view providers as independent contractors—not employees—using their platforms to obtain referrals and transact with clients.6 This designation is frequently made explicit in the formal agreement that establishes the terms of the provider-company relationship.7 In addition, many on-demand companies give providers some (or absolute) ability to select or refuse jobs, set their hours and level of participation, and control other aspects of their work. In some ways, then, the gig economy can be viewed as an expansion of traditional freelance work (i.e., self-employed workers who generate income through a series of jobs and projects).

However, gig jobs may differ from traditional freelance jobs in a few ways. The established storefront and brand built by the tech-platform company reduces entry costs for providers and may bring in groups of workers with different demographic, skill, and career characteristics.8 Because gig workers do not need to invest in establishing a company and marketing to a consumer base, operating costs may be lower and allow workers' participation to be more transitory in the gig market (i.e., they have greater flexibility around the number of hours worked and scheduling).

In addition, a few commonly held characteristics of the provider-company relationship, when taken together, set gig work apart from the traditional freelance worker model.

- On-Demand Companies Collect a Portion of Job Earnings. On-demand companies collect commissions from providers for jobs solicited through the company platform. Commissions often take the form of a flat percentage rate applied to job earnings, but some companies employ more sophisticated models. For example, in 2014, Lyft announced that it would return a portion of its 20% commission on rides as a bonus to certain high-activity drivers.9

- On-Demand Companies Control the Brand. On-demand companies rely on the jobs brokered through their platform to generate revenue, and therefore have a clear stake in attracting and retaining clients. Consequently, and to varying degrees, these companies are selective about who can operate under their brand. Some on-demand businesses condition provider participation on a background check and credentials (e.g., some require past work experience, licenses, or asset ownership),10 and some reserve the right to terminate the relationship if the work delivered does not meet company-defined standards of quality and professionalism.

- On-Demand Companies Control the Provider-Client Relationship. Some on-demand companies discourage or bar providers from accepting work outside the platform from clients who use the company's platform. The provider agreement for business-services company Upwork, for example, includes a noncircumvention clause that prohibits providers from working with any client that identified the provider through the Upwork site for 24 months.11 Likewise, "service professionals" working with the on-demand home-services company Handy must agree that they will "not affirmatively solicit [clients] originally referred through the Handy Platform to book jobs through any means other than the Handy Platform."12 This is a potentially important difference between gig work and traditional freelance work, because it curtails the provider's ability to build a client base or operate outside the platform.13

Measuring Gig Workers

Currently, the federal government does not publish statistics on the gig economy workforce. Instead, most of what is known about the number and characteristics of gig workers is drawn from related labor and tax entity statistics or comes from private-sector studies and academic research.

Measuring and characterizing the gig economy workforce are challenging tasks for several reasons. A first necessary step to measuring gig workers is establishing a precise and measurable statistical definition of the gig economy, a complicated task given the relative newness of the concept, and its broad and evolving application.14 A second and closely related challenge is designing a survey that identifies individuals—through self-reported information—who meet this definition. This challenge requires carefully formulated survey questions that account for how workers perceive their gig economy activity and a data collection strategy that aligns with the potential for seasonal or otherwise dynamic participation.15

In addition to survey design issues, the relative infrequency of gig work in the overall population may create additional challenges to obtaining reliable estimates of these workers' characteristics and work patterns.16 Finally, modifying existing labor force survey instruments to measure these new labor force areas may require significant time and funding.

Related Federal Labor and Business Statistics

While not measuring gig work specifically, federal statistics on self-employment, nonemployer establishments (i.e., business owners who are subject to federal income tax and have no paid employees), and nontraditional work arrangements may provide insight into the size and growth of the gig workforce.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Data: Contingent Workers, Alternative Employment Arrangements, and Self-Employment

Existing large-scale labor force survey data on nontraditional work arrangements and self-employment may provide some insights, but are imperfect proxy measures of contemporary gig economy participants. Notably, in 1995, 1997, 1999, 2001, and 2005, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) funded the collection of data on the number and characteristics of contingent workers (i.e., those who did not expect their jobs to last) and workers in alternative employment arrangements (i.e., independent contractors, on-call workers, temporary help agency workers, and workers employed by contract firms).17 These data—collected through the Contingent Worker Supplement (CWS) to the Current Population Survey—establish that temporary workers and independent contractors represented a nonnegligible share of the workforce in 2005 and are not new phenomena.18 However, they are likely to have limited value to analyses of the gig economy workforce today, because these data predate the launch of the Apple iPhone, and the creation of Uber, Lyft, and other gig economy tech-platform companies.

New CWS data collection is planned for 2017 and is expected to result in an important source of information on the size and characteristics of the gig workforce. In January 2016, then-Labor Secretary Tom Perez announced plans to rerun an expanded version of the CWS in May 2017 that specifically seeks to measure gig work.19 In particular, the BLS plans to include new questions in the 2017 CWS that "explore whether individuals obtain customers or online tasks through companies that electronically match them, often through mobile apps, and examine whether work obtained through electronic matching platforms is a source of secondary earnings."20

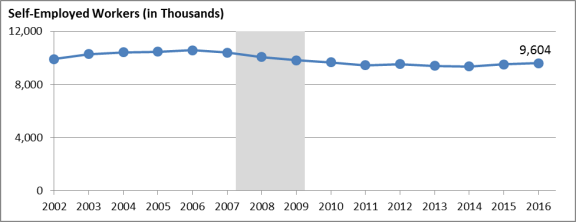

How workers participating in the gig economy should be classified—independent contractors or employees—is an open legal question (see section "Are Workers Within the Gig Economy Employees or Independent Contractors?"); nonetheless, self-employment data may provide some value to analyses of this workforce. The Current Population Survey (CPS), the instrument used by the BLS to produce its monthly unemployment rate estimates, routinely collects data on self-employment. Figure 1 shows the average number of unincorporated self-employed workers working each month in the United States from 2002 to 2016 and traces a gradual decline in self-employment from 2006 to 2011, after which growth has been relatively flat, with modest positive growth (approximately 1.3% annualized growth) between 2014 and 2016.

|

Figure 1. Workers in Unincorporated Self-Employment, 2002-2016 (annual average of monthly estimates) |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Current Population Survey (CPS), Table A-9 (Historical Data), at http://www.bls.gov/webapps/legacy/cpsatab9.htm. Notes: The December 2007-June 2009 recession is shaded in gray. Recession data are from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), http://www.nber.org/cycles.html. |

Recent trends in self-employment—as illustrated in Figure 1—do not appear to support a rapidly growing segment of independent contractors operating in the gig economy. However, due to methodological challenges associated with measuring self-employed workers21 and with capturing gig workers in survey data, it is possible that official self-employment numbers are missing groups of gig workers. CPS asks workers whether they are self-employed and the industry and occupation of their work, but it does not ask if the worker—self-employed or otherwise—uses a tech-based intermediary to find and transact with clients. This could complicate interpretation of self-employment trends because it is not possible to decompose the data into self-employed work in the gig economy and more traditional work that does not include a tech-based intermediary. Another complicating factor to using self-employment data to infer trends in the gig economy workforce is that CPS data are self-reported. This means that how workers are classified in the data is heavily influenced by how workers see themselves (e.g., as an employee or as a self-employed person). Lastly, some gig economy workers are bona fide employees (e.g., Hello Alfred, Managed by Q), and these individuals will not be captured by self-employment statistics.22

U.S. Census Bureau Data: Nonemployer Statistics

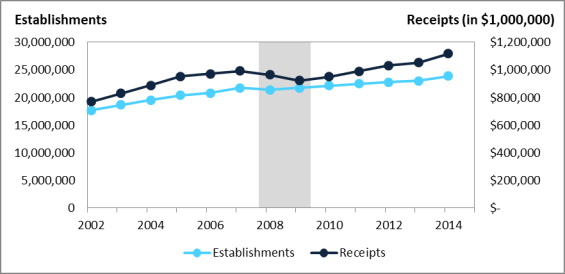

Trends in gig work may be reflected in Census Bureau statistics on nonemployers, business owners who are subject to federal income tax and have no paid employees.23 Figure 2 plots annual estimates of the number of nonemployer establishments and their receipts from 2002 to 2014. Both the number of establishments and their receipts rose steadily over this period, with temporary declines seen only during the 2007-2009 recession.

|

Figure 2. Nonemployer Establishments and Receipts, 2002-2014 (annual estimates) |

|

|

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Nonemployer Statistics, at https://www.census.gov/econ/nonemployer/index.html. Notes: A nonemployer business is "one that has no paid employees, has annual business receipts of $1,000 or more ($1 or more in the construction industries), and is subject to federal income taxes." Receipts include "gross receipts, sales, commissions, and income from trades and businesses, as reported on annual business income tax returns"; see U.S. Census Bureau, Nonemployer Definitions, at http://www.census.gov/econ/nonemployer/definitions.htm. Receipts are in current dollar values, i.e., not adjusted for inflation. The December 2007-June 2009 recession is shaded in gray. Recession data are from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), http://www.nber.org/cycles.html. |

Figure 1 and Figure 2 tell somewhat different stories about the size and trends in self-employment. Where Census data show a steady rise in nonemployer businesses—most of which are "self-employed individuals operating very small unincorporated businesses" by Census's description—BLS data show that self-employment has declined or experienced modest growth over a similar period.

What explains these differences is a matter for further investigation, but some have suggested that they may be related to how survey respondents view their activity. Although individuals recognize (and report to the Internal Revenue Service) that they earn income, they may not view the activities that generate the income as "work," and hence they are not captured in labor force data BLS uses to produce its self-employment estimates.24 Another possibility is that IRS data reveal self-employed individuals with multiple nonemployer businesses (i.e., IRS data count individual self-employed workers multiple times).

Other Data Sources: Company Data and Small-Scale Surveys

A small but growing literature examines data collected from individual companies operating in the gig economy or pockets of gig economy workers.25 These analyses provide information about worker characteristics, their attitudes toward work in a given company or work arrangement, and earnings. However, with few exceptions, they do not profile the gig economy as a whole; instead, they can be viewed as snapshots of certain groups of gig workers.

Together, this body of research suggests that gig workers make up a small share of total workers at a given point in time. Estimates vary, but gig workers constitute less than 1% of total employment in major studies. There is some evidence that workers' participation in the gig economy is transitory (i.e., high rates of worker entry and exit) and that many workers use gig work as a strategy for supplementing income.

Broad Sample Studies

In 2015, economists Lawrence Katz and Alan Krueger collaborated with the RAND Corporation to administer an augmented version of the BLS Contingent Worker Supplement (CWS) to the RAND American Life Panel; notably, the modified CWS survey instrument used by Katz and Krueger included new questions aimed at identifying work in the gig economy.26 A primary goal of the project was to obtain current estimates of the number of workers engaged in alternative work arrangements (a worker group that encompasses but is broader than gig work), and the survey revealed that this number increased markedly from 10.7% in 2005 to 15.8% in 2015. Regarding gig work specifically, they estimate that approximately 0.5% of workers operated through an online intermediary in 2015.27

JPMorgan Chase (JPMC) Institute researchers used data on JPMC primary checking account holders between 2012 and 2016 to estimate the number of adults participating in the gig economy over that time period.28 They identified gig workers (called "labor platform participants" in the JPMC Institute studies) by observing checking deposits (income) from a selection of on-demand platforms.29 While there are some issues with the representativeness of the underlying data, the study produces some interesting findings that are consistent with other work in this area.30 Namely, they found that the share of adult checking account holders who received a checking deposit from a labor platform provider (i.e., received income from such a company) increased between October 2012 and June 2016, with a slowdown in the pace of growth since December 2015. In June 2016, 0.5% of adults with a JPMC checking account received income from a labor platform. A month-to-month analysis of participation (i.e., receipt of income) indicates significant movement into and out of gig work. JPMC Institute researchers estimate that in June 2016, 16% of gig workers were new entrants. Further, among workers who earned income through the gig economy between October 2012 and August 2014, 52% ended their gig careers (i.e., did not receive gig economy income in their JPMC checking accounts) within 12 months. The study also provides some evidence that workers use gig work to supplement income from other sources.31

Other organizations have used a variety of methods to arrive at nationwide estimates of the gig economy workforce.32 These vary considerably in magnitude and appear to be sensitive to the estimation methodology (e.g., how the data are collected, assumptions about how trends move together, and who is included in the definition of gig workers). For example, Harris and Krueger calculate a rough estimate of 600,000 gig workers in 2015 (i.e., approximately 0.4% of U.S. employment) using administrative data on Uber drivers from 2014 and "Google Trends" data that record the number of times Uber and other on-demand companies' names were searched for using the Google search engine.33 McKinsey Global Institute estimates that "less than 1%" of the U.S. working-age population are contingent workers operating through "digital marketplaces for services."34

Company Analysis: Uber Drivers

Uber Technologies partnered with economist Alan Krueger to analyze data collected from a sample of 601 Uber drivers in December 2014 and 632 drivers in November 2015, and aggregate administrative data collected by the company from 2012 to 2015.35 Administrative data reveal that 464,681 drivers were actively partnered with Uber in December 2015, a significant increase over the 162,037 active Uber drivers in December 2014.36 This growth in the number of Uber drivers is remarkable, but may not be indicative of long-term trends; Uber and other driver-service companies are exploring the feasibility of driverless car technology, which may eventually curtail the companies' demand for drivers.37 Survey data indicate that the majority of Uber drivers were male, more than half were between the ages of 30 and 49, and 47.7% had at least a college degree (in December 2014). Many drivers did not use Uber as their sole source of earned income; in both years studied, more than 60% of drivers held another job.38 The authors interpret these survey data to show that the flexibility in work hours provided by Uber is a primary draw for drivers.

Analysis of Independent Workers

For several years, the consulting firm MBO Partners has conducted an annual profiling survey of independent workers.39 It collects information on demographic characteristics, income earned, and recently whether workers use an "on-demand economy platform or marketplace as a source of work or income." MBO is careful to flag an important caveat: their sample comprises 1,100 individuals who report that they "regularly work as independents in an average work week. Those who work as independents in the on-demand economy occasionally or sporadically—for example drive for Uber once a month, do web design as a side gig a few times a quarter, or rent out a room on Airbnb 3 times a year—are not included."40 MBO Partners estimate that in 2014 approximately 900,000 individuals who self-identified as independent contractors used "online talent marketplaces such as Freelancer.com" (i.e., labor only), and 500,000 workers used tech platforms that involve the use of a provider-owned asset (e.g., Uber, Lyft, Airbnb).

Are Workers Within the Gig Economy Employees or Independent Contractors?

Whether a worker in the gig economy may be considered an employee rather than an independent contractor is significant for purposes of various federal labor and employment laws. In general, employees enjoy the protections and benefits provided by such laws, whereas independent contractors are not covered. Two laws, in particular, have drawn recent attention. The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) generally requires the payment of a minimum wage and overtime compensation for hours worked in excess of a 40-hour workweek.41 The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) recognizes a right to engage in collective bargaining for most employees in the private sector.42

Federal Courts' Consideration of Gig Workers' Classification

The FLSA applies only to employees and does not regulate the use of independent contractors. Whether an individual is an employee is often a threshold question that must be answered to determine whether the FLSA's requirements apply.43 Courts have generally concluded that the economic reality of a working relationship will determine whether an individual is actually employed by an employer.44 To evaluate the economic reality of such a relationship, courts will examine all of the circumstances of the work activity and not just an isolated factor. Among the factors a reviewing court will consider to determine employee status are

- the nature and degree of the alleged employer's control over the individual;

- the individual's opportunity for profit or loss;

- the individual's investment in equipment or materials required for his task;

- whether the service rendered requires a special skill;

- the degree of permanency and the duration of the working relationship; and

- the extent to which the service rendered is an integral part of the alleged employer's business.45

In July 2015, a Lyft driver in Florida filed a complaint with a federal district court in Tampa alleging a violation of the FLSA.46 The driver maintained that Lyft controls the manner and means by which all drivers accomplish their work, controls all rates of pay for its drivers, retains the right to discipline drivers at its sole discretion, and restricts drivers' ability to work by permitting them to work only certain hours each day.47 In December 2015, however, Lyft and the driver entered an agreement to dismiss the case.48

Several Uber drivers have also alleged violations of the FLSA. In Suarez v. Uber Technologies, Inc., for example, a group of drivers alleged that they had not been paid (1) for all of the hours they actually worked, (2) the federal minimum wage for each hour worked, and (3) overtime compensation for hours worked in excess of 40 hours in one week.49 Uber sought to compel arbitration for the drivers' claims based on its services agreement, which includes a provision that requires arbitration for all disputes related to the agreement and the employment relationship between the company and its drivers.50 Concluding that the arbitration provision was not unconscionable, the court in Suarez ordered the drivers to submit their claims to arbitration.51 The enforcement of the arbitration provision in Uber's services agreement has resulted in little case law on the FLSA's application to the company's drivers.

State Wage-Related Claims

Uber drivers have also alleged violations of state worker protection laws.52 Resolution of these claims would also appear to require a determination about whether the individuals at issue are employees and not independent contractors. In June 2015, California's labor commissioner concluded that a former Uber driver was an employee for purposes of the state's worker protection laws based on the company's control over its drivers. In Berwick v. Uber Technologies, the former driver sought unpaid wages, reimbursement related to the use of her own vehicle, liquidated damages, and penalties associated with the failure to pay prompt wages.53 After considering various factors, similar to those used to determine employee status under the FLSA, the commissioner maintained, "Defendants hold themselves out as nothing more than a neutral technological platform, designed simply to enable drivers and passengers to transact the business of transportation. The reality, however, is that Defendants are involved in every aspect of the operation."54

The commissioner awarded the former driver amounts reflecting mileage for the use of her car and interest on her unpaid balance of expenses, but dismissed her claims for wages, liquidated damages, and penalties. The commissioner noted that the former driver had, in fact, been paid, and that she lacked sufficient evidence to support her claim for additional wages. The former driver's claims for liquidated damages and penalties appear to have been tied to her claim for unpaid wages.

Although Uber initially appealed the commissioner's order, the case now appears to be part of a larger settlement effort by the company.55 In August 2016, a federal district court denied preliminary approval for a proposed settlement that would have included an $84 million payment to Uber drivers in California and Massachusetts.56 The court maintained that the settlement, which also provided for nonmonetary relief, was "as a whole ... not fair, adequate, and reasonable."57 The court's rejection of the proposed settlement was based largely on the settlement of the drivers' claim under California's Private Attorneys General Act, which creates a cause of action for private plaintiffs to recover civil penalties that are otherwise only recoverable by the state.58 Under the proposed settlement, the drivers would have received just $1 million from the company when the potential verdict value of the claim was over $1 billion.59

In March 2017, a California court rejected a proposed settlement in a separate case involving Uber's alleged failure to comply with the state's minimum wage and overtime requirements.60 The settlement was reportedly opposed by the court because it would provide little relief to drivers, with the majority of the settlement being given to the state and paying administrative costs and attorneys' fees.61

Gig Workers' Rights to Organize and Bargain Collectively

Section 7 of the NLRA states, "Employees shall have the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.... "62 The NLRA requires an employer to negotiate in good faith with a labor organization that becomes the exclusive representative for a bargaining unit of employees. Independent contractors are specifically excluded from the NLRA's definition for the term employee.63 Thus, the NLRA does not require an employer to negotiate with independent contractors over the terms and conditions of their employment.

In light of the exclusion of independent contractors from coverage under the NLRA and a desire to provide collective bargaining rights to at least some gig workers, the city of Seattle has considered legislation that would allow "for-hire vehicle drivers" to be represented by an "exclusive driver representative."64 Under legislation passed recently by the Seattle City Council, the exclusive driver representative would negotiate with the driver coordinator over various subjects, including minimum hours of work, vehicle equipment standards, and conditions of work.65 Some, however, have questioned the legitimacy of the measure.66 At least one commentator has interpreted the NLRA's explicit exclusion of independent contractors as preempting state or local legislation that would restore collective bargaining rights to such individuals.67

Protections and Benefits for Gig Workers

Individuals working in the gig economy may gain potential benefits in the form of easier entry into and exit from work and greater flexibility to choose jobs and hours. In contrast, as discussed above, many of the typical labor protections provided by federal legislation, such as those in the FLSA, center on the concepts of employee and employer. In the case of the FLSA, approximately 128.5 million, or 89%, of the nation's 144.2 million wage and salary workers are covered by its provisions.68 As discussed, the FLSA protections, including minimum wage and overtime provisions, are generally not extended to independent contractors.

Employee Protections

In a traditional employment relationship, an individual is economically dependent on an employer, and thus not in control of various aspects of work life (e.g., working hours, choice of work tasks). That economic dependency, however, often comes in exchange for some measure of economic security through benefits and protections. Below is a partial list of labor standards and related provisions that are likely affected by the absence of a traditional employment relationship:69

- Minimum Wage. Most workers covered by the FLSA are entitled to a minimum hourly wage, which is currently $7.25 per hour.70 In addition, more than half of the states currently have minimum wage rates for FLSA-covered workers that are above the federal rate.71 In contrast, for workers not covered by the FLSA, a category mainly consisting of independent contractors, there is no guaranteed minimum wage rate.

- Overtime Compensation. The FLSA does not limit work hours; rather, it requires additional payment for hours worked in excess of 40 per workweek. Most workers covered by the FLSA must be compensated at one-and-a-half times their regular rate of pay for each hour worked over 40 hours in a workweek.72 Workers not covered by the FLSA are not entitled to additional compensation for hours worked in excess of 40 per workweek.

- Unemployment Compensation. The cornerstone of the income support for unemployed workers is the federal-state Unemployment Compensation (UC) program, which is generally financed by employer taxes.73 Whereas the specifics of UC benefits are determined by each state, generally eligibility is based on attaining qualifying wages and employment in covered work and typically does not include independent contractors.

- Family and Medical Leave. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) entitles eligible employees to unpaid, job-protected leave for qualifying family and medical reasons. Because eligibility for FMLA benefits is tied to an individual's work history with an employer and uses the FLSA concept of employment, independent contractors are not entitled to FMLA provisions.74

- Employer Payroll Taxes. In a traditional employment relationship, an employer is responsible for paying the employer's share of Social Security and Medicare taxes (payroll or FICA taxes) and for withholding the employee's share of these same taxes. Independent contractors, however, are responsible for paying self-employment taxes (i.e., the employer and employee shares of FICA taxes).

Voluntary Employer-Provided Benefits

Beyond federally mandated labor standards, certain other benefits often associated with traditional employment relationships may not be available in the same form to workers in the gig economy. In many cases, employers may offer a combination of benefit access and subsidies to employees. The information in Table 1 includes rates of access, participation, and take-up that civilian employees have to various benefits.75 These data are intended to show the relatively high prevalence of certain employer-based benefits that independent contractors, by definition, do not have access to through employers. For each benefit type below, the percentage of workers with access by work status is provided to demonstrate the higher proportion of access for full-time workers.

|

Benefit Type |

Access |

Participation |

Take-Up Rate |

|

|

Health Benefitsa |

71% |

58% |

81% |

|

|

Full Time |

88% |

73% |

83% |

|

|

Part Time |

20% |

14% |

67% |

|

|

Retirement Benefitsb |

69% |

54% |

78% |

|

|

Full Time |

80% |

65% |

81% |

|

|

Part Time |

37% |

22% |

59% |

|

|

Life Insurancec |

59% |

57% |

98% |

|

|

Full Time |

74% |

73% |

98% |

|

|

Part Time |

12% |

11% |

89% |

|

|

Short-Term Disabilityd |

38% |

37% |

97% |

|

|

Full Time |

46% |

45% |

98% |

|

|

Part Time |

14% |

13% |

90% |

|

|

Paid Sick Leavee |

68% |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

Full Time |

80% |

|||

|

Part Time |

31% |

|||

|

Paid Vacationsf |

73% |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

Full Time |

87% |

|||

|

Part Time |

35% |

|||

|

Paid Family Leaveg |

14% |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

Full Time |

16% |

|||

|

Part Time |

5% |

|||

|

Child Careh |

11% |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

Full Time |

13% |

|||

|

Part Time |

5% |

|||

|

Subsidized Commutingi |

7% |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

Full Time |

8% |

|||

|

Part Time |

3% |

|||

|

Wellness Programsj |

41% |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

Full Time |

47% |

|||

|

Part Time |

25% |

|||

Source: CRS analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Bulletin 2785, Washington, DC, September 2016, https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2016/ebbl0059.pdf.

Notes: In the National Compensation Survey (NCS), an employee is considered to have "access" to a benefit plan if it is available for their use, regardless of whether the employee chooses to participate in the given benefit plan. In addition, access does not indicate the relative share of a given benefit that an employer provides compared with the employee share of the benefit. Access rates in this section refer to the "civilian" workforce, which includes private industry and state and local government establishments. An employee is a "participant" in a contributory plan if that individual has paid required contributions and fulfilled applicable service requirements. The "take-up rate" is an estimate of the percentage of workers with access to a given benefit plan who participate in the plan. The notion "n/a" indicates that data are not available.

a. In the NCS, health care is a collective term for medical, dental, vision, and outpatient prescription drug benefits. If a worker has access to at least one of these benefits, that individual is considered to have access to health care. NCS: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Table 9.

b. Includes defined benefit pension plans and defined contribution retirement plans. If a worker has access to at least one of these plan types, that individual is considered to have access to retirement benefits. NCS: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Table 2.

c. NCS: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Table 16.

d. These plans provide benefits for non-work-related illnesses or accidents on a per-disability basis, typically for a 6-month to 12-month period. NCS: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Table 16.

e. Sick leave is paid absence from work if an employee is unable to work because of a non-work-related illness or injury. The employer usually provides all or part of an employee's earnings. Employees commonly receive their regular pay for a specified number of days off per year. Sick leave is provided on a per-year basis, usually expressed in days, and is never insured. NCS: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Table 32.

f. Vacations are leave from work (or pay in lieu of time off) provided on an annual basis and normally taken in blocks of days or weeks. Paid vacations commonly are granted to employees only after they meet specified service requirements. The amount of vacation leave received each year usually varies with the length of service. Vacation time off normally is paid at full pay or partial pay, or it may be a percentage of employee earnings. NCS: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Table 32.

g. Family leave is granted to an employee to care for a family member and includes paid maternity and paternity leave. The leave may be available to care for a newborn child, an adopted child, a sick child, or a sick adult relative. Paid family leave is given in addition to any sick leave, vacation, personal leave, or short-term disability leave that is available to the employee. NCS: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Table 32.

h. This benefit provides either full or partial reimbursement for the cost of child care in a nursery, daycare center, or babysitter. Care can be provided in facilities either on or off the employer's premises. NCS: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Table 40.

i. NCS: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Table 40.

j. These programs provide a structured plan, independent from health insurance that offers employees two or more of the following benefits: smoking cessation programs, exercise or physical fitness programs, weight control programs, nutrition education, hypertension tests, periodic physical examinations, stress management programs, back-care courses, and lifestyle assessment tests. NCS: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Table 40.

Table 1 data indicate that for some of the major benefit categories, such as health, retirement, and life insurance, a majority of employees have access to these benefits through their employers, with correspondingly high take-up rates for these benefits. The difference between access rates for full-time and part-time workers likewise shows an increasing likelihood of having access to benefits through traditional, full-time employment compared with other work arrangements. To the extent that gig employment more closely resembles part-time employment, it is likely that workers in this segment of the economy might also have relatively lower access to the traditional employment-related benefits.

These sorts of benefits have traditionally been provided by employers due to cost (e.g., economies of scale) and administrative efficiency, and are voluntary.76 This list of possible employer-assisted benefits above does not mean that independent contractors have no access to such benefits. Rather, these benefits, which are more common for traditional, full-time employees, would have to be accessible through another means, such as a spouse's employer or a market mechanism (e.g., health insurance exchange).

Considerations: Independent Contractors in the Gig Economy

As shown in previous sections of this report, the gig economy, and the labor and regulatory issues associated with it, is not well understood. There is considerable uncertainty, for example, about the number of workers in the gig economy and whether gig work is a primary or secondary source of income for the workers involved. In addition, some are concerned that gig workers lack access to benefits and protections associated with traditional employment relationships, such as those discussed in "Employee Protections" and listed in Table 1. Although it is unclear how access to benefits for independent contractors in the gig economy or in general may differ from traditional employment, it is clear that these benefits would likely have to be provided through a nonemployer mechanism, because by definition independent contractors are not employees.

If the availability of benefits and protections for independent contractors in the gig economy continues to draw congressional attention, and to the extent that gig workers seek access to benefits traditionally associated with employed workers, several relevant policy-related considerations may arise as to the best approach to resolve these issues. These include the following considerations:

- Which, if any, protections and benefits should be available to workers in the gig economy? Many of the federal labor protections listed in "Employee Protections" apply to employees but often exclude bona fide independent contractors. This exclusion is often undergirded by assumptions that independent contractors have either sufficient market power or a preference for independence from any employer, such that these workers do not need or prefer the level of protection afforded to traditional employees. If these assumptions do not hold for workers in the gig economy, consideration may be given to which benefits are essential or fundamental for these workers. One recent proposal in this area would provide for the establishment of a third employment category for workers—called independent workers—who are not traditional employees, but who should not be considered independent contractors. Per this proposal, workers in the gig economy who are deemed independent workers would qualify for benefits associated with a more traditional employment relationship (e.g., insurance, tax withholding) but not labor protections that are based on the number of hours worked (e.g., minimum wage and overtime), given the inherent difficulty of tracking hours in gig employment.77

- If protections and benefits are extended to more workers in the gig economy, who is responsible for enforcing protections or providing benefits? A possible consideration regarding benefits and protections for workers in the gig economy is that individuals may work for multiple businesses. To the extent this occurs and benefits are provided through and protections are enforced by an employer, consideration may be given to determining which of the multiple employers is responsible for providing access or enforcement of labor standards. This could result in determining a primary employer for an individual or determining some shared responsibility across employers.

- If benefits are accessible outside of a traditional employment relationship, how might access be structured? Rather than employers providing these benefits, intermediaries (e.g., nonprofits) might facilitate the administration and purchasing of various benefits.78 A recent letter from interested parties in the on-demand economy, for example, urged policymakers to consider creating models that would allow on-demand workers to pay into a common fund that provides health, retirement, unemployment, and other benefits that are not tied to a single employer.79 New mechanisms, such as portable benefits or risk-pooling,80 may serve to provide benefits to workers in the on-demand or gig economy.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

On-demand companies such as Uber (which provides driver services) or TaskRabbit (whose providers perform household errands and tasks) use Internet- or application-based technological platforms to match consumers to a select pool of potential service providers. The on-demand aspect of these companies refers to their use of technology to respond to a customer's immediate need (e.g., for a driver or delivery) or specific need (e.g., for a particular rental or service provider skillset). |

| 2. |

Although this report uses the term gig economy, similar terms include peer-to-peer markets or the peer economy, the sharing economy, collaborative economy, matching economy, talent marketplaces, and others. |

| 3. |

Gig workers staff jobs arranged through on-demand companies. For example, gig workers are the Uber drivers delivering riders to destinations and the Handy "home service professionals" performing various household services booked through the Handy platform. |

| 4. |

Einav, Farronato, and Levin (2015) discuss these pricing and matching mechanisms and other aspects of peer-to-peer markets in greater detail. Liran Einav, Chiara Farronato, and Jonathan Levin, "Peer-to-Peer Markets," National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper no. 21496, August 2015, at http://www.nber.org/papers/w21496 (hereinafter "NBER Working Paper"). |

| 5. |

In their 2015 examination of the gig economy, Harris and Krueger provide descriptions of "several prominent online intermediary companies." See Seth D. Harris and Alan B. Krueger, A Proposal for Modernizing Labor Laws for Twenty-First-Century Work: The "Independent Worker", The Hamilton Project, Discussion Paper no. 2015-10, December 2015, chap. 8, http://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/modernizing_labor_laws_for_twenty_first_century_work_independent_worker (hereinafter "Harris and Krueger 2015"). |

| 6. |

Some on-demand companies use a hybrid staffing model in which providers (gig workers) are classified as independent contractors, but workers responsible for company operations are hired as bona fide employees. For example, home-cleaning company Handy engages its "home service professionals" (the company term for individuals who provide cleaning services) as independent contractors, but hires workers in management, engineering, finance, marketing, and other positions as employees; see https://www.handy.com/careers. Other on-demand companies hire providers as employees (not independent contractors). These companies include the butler-service company Hello Alfred and the office-services company Managed by Q. See Hello Alfred, "Frequently Asked Questions: Who are Alfreds?" at http://help.helloalfred.com/7704-How-Alfred-Works/110749-who-are-alfreds; and Katie Benner, "Profile: Managed by Q (Happiness Can Be an On-Demand App)," Bloomberg, Bloomberg Brief: Gig Economy, June 15, 2015, http://newsletters.briefs.bloomberg.com/document/4vz1acbgfrxz8uwan9/front. Finally, some providers who are engaged as independent contractors have disputed this designation (see section "Are Workers Within the Gig Economy Employees or Independent Contractors?" of this report). |

| 7. |

See, for example, Handy's Service Professional Agreement, which states, "Handy's role is limited to offering the technology platform as a referral tool for Service Requesters and Service Professionals and facilitating payments from Service Requesters to Service Professionals," at https://www.handy.com/pro_terms (hereinafter "Handy's Service Professional Agreement"). |

| 8. |

Notably, many popular gig economy activities—such as delivery and personal-errand services—are considered to be low-skill, low-pay activities. |

| 9. |

Douglass Macmillan, "Lyft Reintroduces Commissions on Rides, With a Twist," Wall Street Journal, Digits Blog, August 11, 2014, http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2014/08/11/lyft-reintroduces-commissions-on-rides-with-a-twist/. |

| 10. |

For example, home-services company Handy requires that providers have paid experience in home cleaning and be legally permitted to work in their location; see "Requirements" at https://www.handy.com/apply. The delivery-services company Postmates requires its operators to own a mode of propelled transport (e.g., car, bicycle, scooter) and have a valid driver's license; see "Requirements" at https://postmates.com/apply. Among other requirements, Uber drivers must generally pass a knowledge test for their city of operation and use vehicles that meet certain standards (e.g., age of car). |

| 11. |

Upwork providers may opt out of the noncircumvention clause by paying a fee ($2,500 minimum). See the Upwork User Agreement (section 7) at https://www.upwork.com/info/terms/. |

| 12. |

Handy's Service Professional Agreement, section 10 Other Business activities, at https://www.handy.com/pro_terms. |

| 13. |

Relatedly, it is unclear whether the provider's professional reputation can be separated from the on-demand platform used to transact with clients. That is, the client may view the provider's performance as being the result of company policy or culture, or otherwise perceive some value-added from engaging the provider through the on-demand platform. If so, the client may be less willing to hire the same provider off-platform. |

| 14. |

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) notes the lack of an official definition of the gig economy; see Elka Torpey and Andrew Hogan, Career Outlook: Working in a Gig Economy, BLS, May 2016, http://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2016/article/what-is-the-gig-economy.htm. The complexity of crafting an objective definition of gig work is illustrated by the Commerce Department's related efforts to define digital matching firms, which Commerce identifies as a subsector within the sharing economy space. Commerce identifies four defining characteristics of firms in this subsector, but further notes that whether some firms (e.g., for certain peer-to-peer lending firms) meet these criteria depends on interpretation. Rudy Telles Jr., Digital Matching Firms: A New Definition in the "Sharing Economy" Space, Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration Issue Brief 01-16, June 2016, https://www.esa.gov/sites/default/files/digital-matching-firms-new-definition-sharing-economy-space.pdf. |

| 15. |

While recent studies have probed how gig workers use gig work, questions remain about which workers combine gig work with more traditional forms of employment (e.g., school teacher during the week and Uber driver during the weekends) and the dynamics of gig work (i.e., how and when workers move in and out of gig work). The frequency of gig work, whether it is a primary or secondary job, and seasonal aspects (if any) will matter importantly to survey design. For example, whether there is a seasonality to gig work (e.g., greater participation in the summer months or during the winter holidays) will matter to the frequency and time(s) of year that such a survey is administered. |

| 16. |

Labor force statistics are, with very few exceptions, based on survey data collected from a sample (i.e., a subset) of the broader population. For example, BLS estimates the unemployment rate based on data collected from individuals in approximately 60,000 households through the Current Population Survey. In general, these estimates are more precise (i.e., reliable) when based on information collected from a larger group of people. Statistical agencies like the BLS have policies of publishing only statistics that meet a certain level of statistical precision. Statistics that are not published tend to be those describing relatively scarce groups of people; for example, the BLS does not publish unemployment rates of female veterans of World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam Era (collectively). Studies that attempt to quantify the number of gig workers at a point in time generally conclude that they represent less than 1% of overall employment; see "Other Data Sources: Company Data and Small-Scale Surveys." While national labor force surveys are likely to produce statistically significant estimates of the overall number of gig workers, they may not produce publishable statistics that describe the demographic and economic characteristics of gig workers in great detail. |

| 17. |

Contingent work has many definitions, and estimates of the contingent workforce size, composition, and trends can vary substantially by the definition used. BLS considers contingent workers to be those who do not expect their jobs to last beyond an additional year, and produced three sets of estimates that vary by the sets of workers considered (e.g., wage and salary workers, self-employed workers and independent contractors, and both groups). BLS, "Contingent and Alternative Employment Arrangements, February 2005," July 27, 2005, at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/conemp.nr0.htm. |

| 18. |

In 2005—the last year the Contingent Worker Supplement data were collected—between 1.8% and 4.1% of employed workers were in temporary work arrangements (or contingent workers) depending on the definition used to measure these workers. In that same year, independent contractors made up 7.4% of employment, and on-call workers made up 1.8% of employment. Princeton University funded the collection of data on alternative work arrangements using a version of the CWS that included questions aimed at identifying individuals participating in the gig economy. The survey was conducted by RAND Corporation, which administered it as part of its American Life Panel. Analysis of these data is summarized in section "Other Data Sources: Company Data and Small-Scale Surveys" of this report. |

| 19. |

Secretary Tom Perez, Innovation and the Contingent Workforce, U.S. Department of Labor, January 25, 2016, https://www.doleta.gov/usworkforce/whatsnew/eta_default.cfm?id=6437. Princeton University funded the collection of data on alternative work arrangements using a version of the CWS that included questions aimed at identifying individuals participating in the gig economy. The survey was conducted by RAND Corporation in 2015, which administered it as part of its American Life Panel. Analysis of these data is summarized in section "Other Data Sources: Company Data and Small-Scale Surveys" of this report. |

| 20. |

Bureau of Labor Statistics, "Proposed Collection, Comment Request," 81 Federal Register 67394, September 30, 2016; available from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/30/2016-23639/proposed-collection-comment-request. |

| 21. |

Identification of self-employed workers (working within and outside of the gig economy) can be challenging and subject to error. For example, preliminary research findings by Abraham et al. reveal that, on average (across data from 1996 to 2012), 51.1% of individuals identified as self-employed in the Current Population Survey data (the data source for Figure 1) are not identified as self-employed in the Detailed Earnings Records (DER), an extract from the Social Security Administration's Master Earnings File. Likewise, on average, 65.4% of self-employed individuals in DER are not identified as self-employed in CPS data. Katharine Abraham, John Haltiwanger, Kristin Sandusky, and James Spletzer, "Measuring the Gig Economy," presentation to the Society of Labor Economists, May 6, 2016, http://www.sole-jole.org/16375.pdf. |

| 22. |

See footnote 6 for additional discussion. |

| 23. |

Census defines nonemployers this way: "A nonemployer business is one that has no paid employees, has annual business receipts of $1,000 or more ($1 or more in the construction industries), and is subject to federal income taxes. Most nonemployers are self-employed individuals operating very small unincorporated businesses, which may or may not be the owner's principal source of income." See U.S. Census Bureau, Nonemployer Definitions, at https://www.census.gov/epcd/nonemployer/view/define.html. Census estimates are based on IRS tax return information. For more information on methods, see Census Bureau, Nonemployer Statistics, How the Data are Collected (Coverage and Methodology), at http://www.census.gov/econ/nonemployer/methodology.htm. |

| 24. |

When asked about the preliminary findings of his work measuring gig workers, economist Lawrence Katz remarked to Fusion magazine that "[individuals interviewed by the research team] do answer about their share, gig, and freelance economy activities when specifically asked about other specific ways they made income ... but many of them do not seem to consider such activities as 'regular jobs.'" Rob Wile, "There Are Probably Way More People in the 'Gig Economy' than We Realize," Fusion, July 27, 2015, http://fusion.net/story/173244/there-are-probably-way-more-people-in-the-gig-economy-than-we-realize/. |

| 25. |

Aggregating company data may appear to be a straightforward way of estimating the number of workers engaged in the gig economy. However, these data may be challenging to obtain, given their proprietary nature. In addition, some adjustments would be required to account for workers operating on multiple platforms (i.e., to avoid double-counting workers) and to identify active providers (i.e., those actually using a platform) among the larger pool of registered providers. |

| 26. |

Lawrence F. Katz and Alan B. Krueger, The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States, 1995-2015, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 22667, September 2016, http://www.nber.org/papers/w22667. The results of the Katz and Krueger study may not predict the findings of the forthcoming BLS CWS precisely (see section "Bureau of Labor Statistics Data: Contingent Workers, Alternative Employment Arrangements, and Self-Employment"), because of differences in sample composition, survey construction, and the phrasing of questions on gig economy participation. |

| 27. |

Gig workers were identified in the RAND-CWS survey using the following series of questions: (1) "On either your main job or a secondary job, do you do direct selling to customers?" (2) "Do you work with an intermediary, such as Avon or Uber, in your direct selling activity?" and (3) "Do you work with an online intermediary to find customers, such as Uber or Task Rabbit?" The RAND-CWS survey questionnaire is at https://alpdata.rand.org/index.php?page=data&p=showsurvey&syid=441. |

| 28. |

The results discussed in this paragraph are from Diana Farrell and Fiona Greig, Paychecks, Paydays, and the Online Platform Economy: Big Data on Income Volatility, JPMorgan Chase & Co. Institute, February 2016, https://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/institute/document/jpmc-institute-volatility-2-report.pdf. The authors published a similar study earlier in the same year, which used a somewhat less reliable estimation strategy. For information on how the methods differ and how they affect estimates of gig economy participation, see endnote 2 of Diana Farrell and Fiona Greig, The Online Platform Economy: Has Growth Peaked?, JPMorgan Chase & Co. Institute, November 2016, https://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/institute/document/jpmc-institute-online-platform-econ-brief.pdf. |

| 29. |

The JPMorgan Chase studies distinguish between "labor platforms" through which individuals (gig workers) identify customers for discrete tasks or projects and "capital platforms" through which individuals sell goods or rent assets. |

| 30. |

Compared to national estimates based on Census data, JPMC account holders are more likely to be male, higher-income, and reside in the western parts of the United States. |

| 31. |

This finding is consistent with Jonathan Hall and Alan Krueger's finding that significant shares of Uber drivers held other jobs. See section "Company Analysis" of this report. |

| 32. |

This report summarizes the results of studies that publish their findings in a research paper that contains a detailed discussion of the research methodologies employed. Analyses that did not meet this criterion, but may nonetheless be informative and interesting, include the Workforce of the Future survey conducted jointly by the Aspen Institute, Burson-Marsteller, Markle, and TIME released in June 2016 (see http://www.burson-marsteller.com/what-we-do/the-future-workforce-survey/) and Dispatches From The New Economy: The On-Demand Economy And The Future Of Work, a joint effort by Intuit Inc. and Emergent Research released in January 2016 (see https://www.slideshare.net/IntuitInc/dispatches-from-the-new-economy-the-ondemand-workforce-57613212); preview of a follow-up study by Intuit and Emergent Research is available at https://www.slideshare.net/IntuitInc/dispatches-from-the-new-economy. |

| 33. |

Harris and Krueger 2015. |

| 34. |

McKinsey Global Institute, A Labor Market that Works: Connecting Talent with Opportunity in the Digital Age, McKinsey & Company, June 2015, http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/employment_and_growth/connecting_talent_with_opportunity_in_the_digital_age. |

| 35. |

The driver survey was designed and the data collected by the Benenson Strategy Group (BSG). The response rate—the percentage of drivers who responded to the invitation to participate in the survey—was approximately 10%, which is relatively low. The most current analysis of survey data is Jonathan V. Hall and Alan B. Krueger, An Analysis of the Labor Market for Uber's Driver-Partners in the United States, NBER working paper 22843, November 2016, http://www.nber.org/papers/w22843. Earlier analysis is at Jonathan V. Hall and Alan B. Krueger, "An Analysis of the Labor Market for Uber's Driver-Partners in the United States," Uber Technologies, January 22, 2015, at http://newsroom.uber.com/2015/01/in-the-drivers-seat-understanding-the-uber-partner-experience. |

| 36. |

Active drivers are those who completed at least four trips in the month of December. |

| 37. |

Max Chafkin, "Uber's First Self-Driving Fleet Arrives in Pittsburgh This Month," Bloomberg Business, August 18, 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2016-08-18/uber-s-first-self-driving-fleet-arrives-in-pittsburgh-this-month-is06r7on. |

| 38. |

In 2014, 31% held a separate full-time job and 30% held a separate part-time job. In 2015, 52% held a separate full-time job and 14% held a separate part-time job. |

| 39. |

MBO Partners, "Independent Workers and the On-Demand Economy," April 21, 2015, at https://www.mbopartners.com/state-of-independence/past-reports. |

| 40. |

Ibid., p. 5. |

| 41. |

29 U.S.C. §§201-219. |

| 42. |

29 U.S.C. §§151-169. |

| 43. |

See, e.g., Secretary of Labor v. Lauritzen, 835 F.2d 1529 (7th Cir. 1987), cert. denied, 488 U.S. 898 (1988) (determining whether migrant workers are employees for purposes of the Fair Labor Standards Act or "independent contractors not subject to the requirements of the Act."). |

| 44. |

Ibid. |

| 45. |

Ibid. See also Administrator David Weil, The Application of the Fair Labor Standards Act's "Suffer or Permit" Standard in the Identification of Employees Who Are Misclassified as Independent Contractors, U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), Wage and Hour Division, Administrator's Interpretation no. 2015-1, July 15, 2015, http://www.dol.gov/whd/workers/Misclassification/AI-2015_1.htm. |

| 46. |

Frederic v. Lyft, Inc., No. 8:15-cv-01608 (M.D. Fla. filed July 8, 2015). |

| 47. |

Ibid. |

| 48. |

Nathan Hale, Florida Driver Agrees to Drop FLSA Suit Against Lyft, Law360 (December 11, 2015), available at http://www.law360.com/articles/737009/florida-driver-agrees-to-drop-flsa-suit-against-lyft. |

| 49. |

No. 8:16-cv-166-T-30MAP, 2016 WL 2348706 (M.D. Fla. May 4, 2016). See also Richemond v. Uber Technologies, Inc., No. 16-cv-23267, 2017 WL 416123 (S.D. Fla. January 27, 2017) (granting employer's motion to compel arbitration for FLSA claims); Carey v. Uber Technologies, Inc., No. 1:16-cv-1058, 2017 WL 1133936 (N.D. Ohio Mar. 27, 2017) (same). |

| 50. |

Ibid., at *2. |

| 51. |

Ibid., at *5. |

| 52. |

See, e.g., O'Connor v. Uber Technologies, Inc., No. CV-13-03826-EMC (N.D. Cal. filed August 8, 2015). |

| 53. |

No. 11-46739 EK (Cal. Lab. Comm. June 3, 2015). |

| 54. |

Ibid., at 9. |

| 55. |

See O'Connor v. Uber Technologies, 201 F.Supp.3d 1110, 1119 (N.D. Cal. 2016) (discussing settlement agreement as covering "at least fifteen other lawsuits currently pending in federal and California state courts," including Berwick v. Uber Technologies). |

| 56. |

Ibid. |

| 57. |

Ibid., at 1113. |

| 58. |

Ibid., at 1135. |

| 59. |

Ibid., at 1133-35. |

| 60. |

See Joel Rosenblatt & Edvard Pettersson, Uber Deal Giving Drivers $1 Each Fails to Win Over Judge, 46 Daily Lab. Rep. (BNA) A-5 (March 10, 2017). |

| 61. |

Ibid. |

| 62. |

29 U.S.C. §157. |

| 63. |

See 29 U.S.C. §152(3) ("The term 'employee' ... shall not include any individual employed as an agricultural laborer, or in the domestic service of any family or person at his home, or any individual employed by his parent or spouse, or any individual having the status of an independent contractor ..."). |

| 64. |

See Seattle City Council, Giving Drivers a Voice, http://www.seattle.gov/council/issues/giving-drivers-a-voice. See also Lydia DePillis, "Seattle Might Try Something Crazy to Let Uber Drivers Unionize, Washington Post, August 31, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/08/31/seattle-might-try-something-crazy-to-let-uber-drivers-unionize/. |

| 65. |

CB118499, §3 (2015), available at http://www.seattle.gov/council/issues/giving-drivers-a-voice. The term driver coordinator is defined to mean "an entity that hires, contracts with, or partners with for-hire drivers for the purpose of assisting them with, or facilitating them in, providing for-hire services to the public." |

| 66. |

See DePillis, supra note 64. |

| 67. |

Ibid. |

| 68. |

DOL, "Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees; Proposed Rule," 80 Federal Register 38552, July 6, 2015. |

| 69. |

The Wage and Hour Division (WHD) provides a summary of major laws administered by DOL, at http://www.dol.gov/opa/aboutdol/lawsprog.htm. Some of the laws on the WHD list, such as the Employee Polygraph Protection Act, may be narrower in scope than broader laws such as the FLSA. |

| 70. |

The FLSA allows the payment of subminimum wages in some cases, such as for individuals with disabilities and youth workers. See CRS Report R43089, The Federal Minimum Wage: In Brief, by [author name scrubbed], for details. |

| 71. |

See CRS Report R43792, State Minimum Wages: An Overview, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 72. |

As with the minimum wage, there are limited exemptions to the requirement for overtime compensation. See CRS Report R44138, Overtime Provisions in the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA): Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed], for more details. |

| 73. |

For information on the Unemployment Compensation (UC) program, see CRS Report RL33362, Unemployment Insurance: Programs and Benefits, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 74. |

For details on the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), see CRS Report R44274, The Family and Medical Leave Act: An Overview of Title I, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 75. |

In the National Compensation Survey (NCS), an employee is considered to have "access" to a benefit plan if it is available for their use; an employee is a "participant" in a contributory plan if that individual has paid required contributions and fulfilled applicable service requirements; and the "take-up rate" is an estimate of the percentage of workers with access to a given benefit plan who participate in the plan. For example, if health insurance is available to 89% of employees and 73% of those employees pay required contributions into that plan, then the access rate is 89%, the participation rate is 73%, and the take up rate is 82% (73% participation / 89% access). |

| 76. |