Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering India, Burma, and the Bay of Bengal. It is the world’s eighth most populous country with nearly 160 million people living in a land area about the size of Iowa. It is an economically poor nation, and it suffers from high levels of corruption. In recent years, its democratic system has faced an array of challenges, including political violence, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental strains, and Islamist militancy. The United States has a long-standing and supportive relationship with Bangladesh, and it views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. In relations with Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, the U.S. government, along with Members of Congress, has focused on a range of issues, especially those relating to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism.

The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have at times sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades, as well as at the ballot box. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been in office since 2009, and her AL party was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament—in part because the BNP, led by Khaleda Zia, boycotted the vote. The BNP has called for new elections, and in recent years, it has organized a series of blockades and strikes. The AL also has moved forward with a war crimes tribunal to prosecute atrocities committed during Bangladesh’s war of independence from Pakistan in 1971. Many of the accused have been political opponents of the AL government.

There is little optimism among observers that the AL and the BNP will find a compromise over their political differences, and some analysts are concerned that the political crisis could increase the influence of Islamist extremists and further destabilize the country. Bangladeshi authorities have pursued Islamist militants—with some apparent success—but there have been reports of arbitrary detentions and extrajudicial killings. Several militant groups have re-formed after government operations against them, and some allegedly have developed links with international terrorist organizations, such as the Islamic State (IS) and Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS). Also, Islamist extremists increasingly have targeted religious and ethnic minorities—as well as foreigners—in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh likely will face a range of other challenges, particularly related to its population growth, population density, and environmental degradation—which many experts believe likely will be exacerbated by climate change. Some experts project that millions could be displaced by climate change in the future.

In recent years, Rohingya refugees from Burma have fled to Bangladesh to escape persecution. This movement escalated dramatically between August and September 2017 when violence in Burma’s Rakhine State led to a new surge of over half a million Rohingya refugees crossing the border into Bangladesh.

Much international attention has focused on working conditions in Bangladesh. The country plays a significant role in the global textile-industry supply chain. In 2016, Bangladesh’s garment sector accounted for over 80% (or about $25 billion) of the country’s exports. About $5.3 billion of those exports went to the United States. However, the industry has come under increased scrutiny, particularly following the 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed over 1,000 workers.

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview

- Recent Developments

- Rohingya

- Political Dynamics

- Security Situation

- International Crimes Tribunal

- Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

- U.S.-Bangladesh Bilateral Forums

- Security Cooperation

- Foreign Assistance

- U.S.-Bangladesh Trade

- U.S. Human Rights Concerns

- Political Setting

- International Crimes Tribunal

- Human Rights

- Rohingya

- Violence in Arakan (Rahkine) State

- Possible Militant Ties

- U.S. Government Response to the Rohingya Crisis

- Bangladesh Government Response to the Rohingya Crisis

- Labor Issues/Factory Safety

- Peacekeeping

- Economic Development and Trade

- Environmental, Climate, and Food Security

- Regional Issues

- Islamist Extremism

- Geopolitical Context

- India

- China

Summary

Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering India, Burma, and the Bay of Bengal. It is the world's eighth most populous country with nearly 160 million people living in a land area about the size of Iowa. It is an economically poor nation, and it suffers from high levels of corruption. In recent years, its democratic system has faced an array of challenges, including political violence, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental strains, and Islamist militancy. The United States has a long-standing and supportive relationship with Bangladesh, and it views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. In relations with Dhaka, Bangladesh's capital, the U.S. government, along with Members of Congress, has focused on a range of issues, especially those relating to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism.

The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have at times sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades, as well as at the ballot box. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been in office since 2009, and her AL party was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament—in part because the BNP, led by Khaleda Zia, boycotted the vote. The BNP has called for new elections, and in recent years, it has organized a series of blockades and strikes. The AL also has moved forward with a war crimes tribunal to prosecute atrocities committed during Bangladesh's war of independence from Pakistan in 1971. Many of the accused have been political opponents of the AL government.

There is little optimism among observers that the AL and the BNP will find a compromise over their political differences, and some analysts are concerned that the political crisis could increase the influence of Islamist extremists and further destabilize the country. Bangladeshi authorities have pursued Islamist militants—with some apparent success—but there have been reports of arbitrary detentions and extrajudicial killings. Several militant groups have re-formed after government operations against them, and some allegedly have developed links with international terrorist organizations, such as the Islamic State (IS) and Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS). Also, Islamist extremists increasingly have targeted religious and ethnic minorities—as well as foreigners—in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh likely will face a range of other challenges, particularly related to its population growth, population density, and environmental degradation—which many experts believe likely will be exacerbated by climate change. Some experts project that millions could be displaced by climate change in the future.

In recent years, Rohingya refugees from Burma have fled to Bangladesh to escape persecution. This movement escalated dramatically between August and September 2017 when violence in Burma's Rakhine State led to a new surge of over half a million Rohingya refugees crossing the border into Bangladesh.

Much international attention has focused on working conditions in Bangladesh. The country plays a significant role in the global textile-industry supply chain. In 2016, Bangladesh's garment sector accounted for over 80% (or about $25 billion) of the country's exports. About $5.3 billion of those exports went to the United States. However, the industry has come under increased scrutiny, particularly following the 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed over 1,000 workers.

Overview

|

Bangladesh in Brief Land area: 130,170 sq. kilometers, slightly smaller than Iowa Climate: tropical Capital: Dhaka Geography: most of the country is low-lying delta Resources: natural gas, arable land, timber, coal Natural hazards: droughts, cyclones, extensive flooding Ethnicity: 98% Bengali (2011 est.) Religion: 89.1% Muslim, 10% Hindu, 0.9% other (includes Buddhists and Christians) Population: 156.19 million (2016 est.) Life expectancy: 73.2 years (2016 est.) GDP per capita: $3,900 (2016 est.) GDP growth: 6.9% (2016 est.) GDP by sector: agriculture 15.1%, industry 28.6%, services 56.3% (2016 est.) Exports: garments, knitwear, agricultural products, frozen food, jute, leather Export partners: U.S. 13.9%, Germany 12.9%, United Kingdom 8.9%, France 5.0%, Spain 4.7% (2015) Population below the poverty line: 18.5% living on less than $1.90 per day (PPP) (2014) Sources: CIA, World Factbook; Economist intelligence Unit; U.N.; Asian Development Bank |

The United States and Bangladesh have generally enjoyed a positive working relationship. The United States has sought to help Bangladesh with its development goals, including in the areas of sustainable development, health, education, poverty reduction, disaster preparedness, and food security. In recent years, the rise of Islamist militancy has been a cause of concern to the United States and to Bangladesh's Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina, and her government. The two nations hold an annual Partnership Dialogue and a Security Dialogue and have developed a cooperative relationship over the years to meet shared concerns.

Bangladesh faces—and will continue to face—major challenges in the coming years. Bangladesh is undergoing a political struggle between those that would emphasize Islamic religious identity over a relatively more secular identity based on Bengali nationalism. This tension manifests itself through demonstrations, political gridlock, and at times violent street protests. Rising conservative Islamist sentiment may also increasingly become linked to militant organizations and international Islamist movements. A growing population, when combined with environmental stress brought on by natural disasters and climate change, may pose further challenges for Bangladesh, particularly given its already high population density. While the geopolitical rivalry between China and India may present opportunities for Bangladesh, it may also create new tensions or place new demands on the country in the years ahead. The recent arrival of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya from Burma is a potential source of instability and will likely have humanitarian, diplomatic, security, and geopolitical implications for Bangladesh.

Recent Developments

Rohingya

To date in 2017, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees have crossed the border from Burma into Bangladesh. The predominantly Muslim Rohingya have faced persecution in Buddhist-majority Burma for years—especially in Burma's Rakhine State—and an estimated 582,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh since August 2017.1 Bangladeshi authorities have struggled to accommodate the new arrivals, and Sheikh Hasina has called on Burma to take back the displaced Rohingya.2

Political Dynamics

Political instability likely will remain a problem in Bangladesh and could further erode democracy in the country, according to some observers. Some view the risk of social unrest as rising as the 2019 parliamentary election draws nearer.3 A major source of instability is the rivalry between Prime Minister Hasina, of the governing Awami League (AL), and Khaleda Zia, the leader of the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). That rivalry, observers suggest, shows little sign of abating.4 Some observers see few paths to get beyond the current political stalemate, and the BNP likely will resort to further protests to pressure the AL government to hold the 2019 election under a caretaker government.5 In July 2017, some observers pointed to disputes over wages for garment workers as a potential flashpoint of social unrest.6 Others noted the potential that rising food prices, the result of floods in April and August 2017 which destroyed 1.2 million tons of rice in Bangladesh, could be a cause of political instability.7

Security Situation

A report issued by the U.S. State Department's Bureau of Diplomatic Security noted that the "Department … assessed Dhaka as being a high-threat location for political violence directed at or affecting official U.S. government interests." Political demonstrations, the report continued, have led to violent clashes—some of which have resulted in fatalities.8 A Bangladeshi human rights group, Odhikar, reported that, in 2016, 215 people were killed and 9,050 were injured because of inter- or intraparty violence.9

There also are signs of ongoing Islamist militancy, and the continuing political turmoil could create opportunities for Islamists.10 In March 2017, there were several terrorist attacks across the country, making it the deadliest month since July 2016, when an attack on a bakery killed over 20 people, including one U.S. citizen.11 Observers believe the threat of small-scale, religiously motivated attacks continues.

International Crimes Tribunal

The International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) has, according to some, contributed to the country's political instability. The ICT was constituted on March 25, 2010, and it has tried individuals accused of committing human rights abuses during Bangladesh's war of independence against Pakistan in 1971. As of October 2017, 33 cases were under trial at the tribunal.12 Some analysts point out that the trials seem to be aimed at undermining the AL's political opponents, especially Islamists, including members of Jamaat-i-Islami (JI)—the largest Islamist political party in the country and a traditional BNP ally.13 In April 2017, the ICT handed down death sentences to two people who were convicted of committing war crimes during the 1971 war.14 In July 2017, the head of the ICT's investigation arm confirmed that there was an ongoing investigation into Osman Faruque, a top BNP leader.15

Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

The United States has long-standing supportive relations with Bangladesh. Bangladeshis tend to have a positive view of the United States: According to a 2014 Pew opinion survey, 76% of Bangladeshis had a favorable opinion of the United States, compared to 66% of respondents from the United Kingdom.16 The United States and Bangladesh work together on several issues, including development, governance, trade, and security.17 In August 2017, U.S. Acting Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs Alice Wells met with Prime Minister Hasina to discuss U.S.-Bangladeshi relations, including the two countries' efforts to cooperate on security and energy issues.18

U.S.-Bangladesh Bilateral Forums

The United States engages Bangladesh through several fora, including the U.S.-Bangladesh Partnership Dialogue and the U.S.-Bangladesh Dialogue on Security Issues.19 The former seeks to improve ties between the two nations. In June 2016, the Partnership Dialogue—held in Washington, DC—addressed a broad spectrum of issues, including "security cooperation, development and governance cooperation, and trade and investment cooperation."20 Also, following the Dialogue, the United States and Bangladesh issued a joint statement announcing that Bangladesh would be joining the U.S. Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund, which aims to provide security-assistance funding to states fighting extremists.21

Security Cooperation

The United States and Bangladesh see a common interest in working to counter extremist Islamists and their ideology—as well as in promoting regional and global security. Historically, the two countries have shared an interest in supporting U.N. peacekeeping operations. In July 2017, Admiral Harry Harris, Commander of the U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM), met with Prime Minister Hasina and participated in the dedication ceremony for the Bangladesh Institute of Peace Support Operations Training—a $3.6 million facility to train peacekeepers deploying with the United Nations.22 Bangladesh is one of the largest contributors of military personnel to U.N. missions. (See section "Peacekeeping" below for further details.)

The United States has worked to strengthen Bangladesh's maritime security capabilities. The United States transferred a U.S. Coast Guard cutter, the USS Jarvis, to Bangladesh in 2013. A second U.S. cutter, the USS Rush, was transferred in 2015.23 PACOM conducts naval exercises with Bangladesh, including the Southeast Asia Cooperation and Training (SEACAT) exercise, which promotes multilateral cooperation and information sharing with naval forces from Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Singapore, and Thailand.24 PACOM also carries out humanitarian operations, such as Operation Pacific Angel, which provides humanitarian assistance, such as general health and dentistry services, to people in the Asia-Pacific region.25

Additionally, Bangladesh's security forces conduct counterterrorism training with U.S. forces.26 As mentioned above, Bangladesh participates in the State Department's Antiterrorism Assistance program—which provides participating states with counterterrorism training and equipment—and the country has received U.S. funding for law-enforcement training.27 The United States and Bangladesh also signed the Counterterrorism Cooperation Initiative in 2013.28

Foreign Assistance

The United States has been a foreign assistance partner of Bangladesh since its creation in 1971, and many observers contend that the country greatly needs foreign aid. For FY2018, the Trump Administration requested about $138 million in foreign-assistance funding for Bangladesh (Table 1). Previously, for FY2017, the Obama Administration requested about $208 million.29 In 2015, the Asian Development Bank reported that 31.5% of Bangladeshis lived below the national poverty line, and in 2014, 18.5% of Bangladeshis were living on less than $1.90 (PPP) per day.30 Also, about one-quarter of the population—or about 40 million people—faced food-insecurity issues in 2014.31

The United States has partnered with Bangladesh on three major development initiatives: Feed the Future, the Global Climate Change Initiative, and the Global Health Initiative.32 As part of Feed the Future, USAID has implemented programs to improve the food-security situation in Bangladesh—for instance, by working to increase crop yields.33 USAID has provided assistance to Bangladesh across a number of areas, including supporting democratic institutions, promoting health and education, empowering women, and disaster preparedness and response.34

|

FY2016 Actual |

FY2017 Estimate |

FY2018 Request |

||||

|

Development Assistance |

|

|

|

|||

|

Economic Support and Development Fund |

|

|

|

|||

|

Foreign Military Financing |

|

|

|

|||

|

Global Health Programs (USAID) |

|

|

|

|||

|

International Military Education and Training |

|

|

|

|||

|

International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement |

|

|

|

|||

|

Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining and Related Programs |

|

|

|

|||

|

P.L. 480 Title II |

|

|

|

|||

|

Total |

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of State, "Bangladesh," in Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Assistance, Supplementary Tables, Fiscal Year 2018, 2017, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/271014.pdf.

Note: In September 2017, the United States pledged to spend nearly $32 million on an aid package to help displaced Rohingya. Previously, between October 2016 and early September 2017, the U.S. government provided almost $63 million in humanitarian assistance "for vulnerable communities displaced in and from Burma."35

U.S.-Bangladesh Trade

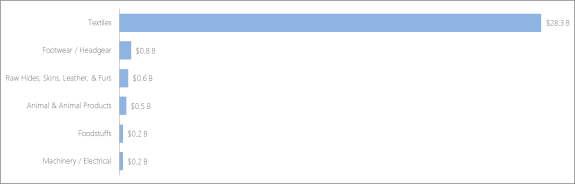

According to USTR, in 2016, Bangladesh was the United States' 50th-largest trading partner in terms of total, two-way goods trade. Exports of U.S. goods to Bangladesh were worth approximately $895 million in 2016 and supported an estimated 6,000 U.S. jobs in 2015. In 2016, major U.S. exports to Bangladesh included miscellaneous grain, seeds, fruit (soybeans) ($249 million), cotton ($96 million), machinery ($83 million), food waste, animal feed ($72 million), and iron and steel ($72 million).36 From Bangladesh, the United States primarily imported woven apparel ($3.8 billion), knit apparel ($1.4 billion), miscellaneous textile articles ($206 million), headgear ($174 million), and footwear ($105 million).37 However, between 2015 and 2016, Bangladeshi garment exports to the United States declined slightly, from about $5.4 billion in 2015 to $5.3 billion in 2016.38 U.S. goods exports to Bangladesh increased 169% from 2006 to 2016.39

The United States and Bangladesh signed a Trade and Investment Cooperation Framework Agreement (TICFA) in 2013, setting up an annual meeting to identify challenges to the countries' bilateral-trade and investment relationship.40 In 2015, U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in Bangladesh amounted to $589 million—an increase of 24.3% from 2014.41 American trade and investment interests also include developing natural gas reserves thought to be in the Bay of Bengal off Bangladesh's coast.42

In 2013, the United States suspended Bangladesh's designation as a beneficiary country under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) program over concerns about workers' rights. As a result, U.S. imports of GSP-eligible products from Bangladesh lost their duty-free status.43 The United States has welcomed Bangladesh's efforts to improve labor conditions in the country, including thousands of factory inspections, but not enough has been done to reimplement GSP privileges.44 The United States has called on Bangladesh to go further to protect workers from unfair labor practices and give workers in export processing zones the same rights as workers elsewhere.45

U.S. Human Rights Concerns

The United States has expressed some concerns about human rights issues in Bangladesh. In 2017, the State Department issued its Human Rights Report, detailing numerous human rights abuses in the country. As mentioned above, the report states that

The most significant human rights problems were extrajudicial killings, arbitrary or unlawful detentions, and forced disappearances by government security forces; the killing of members of marginalized groups and others by groups espousing extremist views; early and forced marriage; gender-based violence, especially against women and children; and poor working conditions and labor rights abuses.46

The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom raised concerns about Bangladesh's human-rights situation, particularly for religious minorities in the country. According to the commission's 2017 annual report, there has been an uptick in violent attacks against religious minorities, as well as against secular bloggers, intellectuals, and foreigners in Bangladesh.47

In September 2017, the State Department issued a statement, saying that the United States was "very concerned" about the influx of Rohingya into Bangladesh. Between October 2016 and September 2017, the U.S. government "provided nearly $63 million in humanitarian assistance for vulnerable communities displaced in and from Burma throughout the region."48 More recently, on September 20, 2017, the United States pledged to spend an additional $32 million on humanitarian aid for the Rohingya.49

Political Setting

Bangladesh is a parliamentary democracy with a unicameral legislature, the Jatiya Sangsad. The 300 members of parliament are directly elected for five-year terms, and an additional 50 seats—which are reserved for women—are filled by the political parties in proportion to their respective vote shares.50 The Awami League, led by Prime Mister Sheikh Hasina, and the Bangladesh National Party, led by Khaleda Zia, are the two main political parties. The Awami League has been viewed as relatively more secular in its approach though some have recently accused the government of "pandering to Islamist zealots."51

According to the International Foundation for Electoral Systems, Bangladeshi elections face several challenges, including a "restricted space for political dialogue; [a] lack of coordination around electoral reform;" and an "absence of leaders equipped to promote peaceful electoral and political processes."52 The United States has been concerned about political unrest and instability in Bangladesh. Following Bangladesh's most recent election in 2014, former U.S. Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Richard Hoagland opined that "the political impasse and negative governance trends in Bangladesh don't bode well for sustainable growth" in the country.53

The AL won the 2008 election, as well as the 2014 election that was boycotted by the BNP (Table 1).54 The BNP boycotted because the AL government did not set up a neutral caretaker government prior to the vote. Starting in 1996, caretaker governments oversaw Bangladesh's general elections. However, in 2011, the AL-controlled parliament ended the caretaker-government system.55 Partially as a result of the BNP's boycott, the AL won an overwhelming majority in parliament in 2014.56

After the election, in January 2015, the BNP called for a nationwide blockade and a series of strikes, known as hartals in South Asia. During the resulting demonstrations, over 120 people were killed.57 Khaleda Zia's motorcade came under attack by AL activists a few months later, while she was campaigning for her party's mayoral candidate in Dhaka, the country's capital. Fifteen members of her entourage were injured.58 In response to the postelection unrest, the State Department issued a statement, saying it was "gravely concerned" about the "unrest and violence" in Bangladesh.59

At the moment, the Jatiya Party (Ershad) is supporting the current AL government, even though it is considered the opposition.60 JI, the largest Islamist party in Bangladesh, historically has been allied with the BNP. Prior to the 2014 vote, the Bangladesh Election Commission banned JI from participating in the election.61 The commission, as well as the Supreme Court, ruled that the party's charter was not in accordance with the country's constitution.62 In early 2017, the AL and BNP were able to work together to appoint a new election commission, but the BNP remains doubtful of the commission's independence.63 The next national election is due in 2019, and some observers believe that Sheikh Hasina is grooming her son, Sajeeb Ahmed Wajed, to become the AL's next leader.64

Since independence in 1971, there often have been tensions between the military and successive civilian governments. The military ruled the country—both directly and indirectly—for nearly 17 years, and there have been three coups and several mutinies.65 Two presidents have been killed in military coups, including Sheikh Hasina's father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, as well as Khaleda Zia's husband, Ziaur Rahman.66 (Both men served as president of Bangladesh and were key figures in the country's struggle for independence from Pakistan in 1971.) Bangladesh returned to a parliamentary democracy in 1991 after Lieutenant General H. M. Ershad resigned. (In 1982, he seized power in a coup and served as president until 1990.)67 Prior to the 2008 general election, the military backed a caretaker government—which represented, according to some, "a de facto coup" since it stayed in power for two years.68 From 2007 to the end of 2008, the military supported the caretaker government's anticorruption program, which convicted 116 politicians and businessmen. The government tried to convict and exile Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia, but it eventually needed to back down, in order to ensure that both of their parties took part in the December 2008 election.69

In 2015, some observers believed that the military was potentially planning a coup because of the AL-BNP political feud and the resulting instability.70 However, there was no such coup. According to the opposition leader, Khaleda Zia, Sheikh Hasina has been "buying" the loyalty of the armed forces by approving military procurement deals and promotions.71 Tensions between security forces and the government over corruption and low wages led members of a paramilitary unit, known as the Bangladeshi Rifles (BDR), to mutiny in February 2009, killing 74 people, including 57 officers.72

|

Bangladeshi Political Parties |

2008 Election Results |

2014 Election Results |

|

Awami League (AL) |

49.0% |

79.1% |

|

Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) |

33.2% |

|

|

Jatiya Party (Ershad)b |

7.0% |

11.3% |

|

Bangladesh Islamic Assembly |

4.6% |

|

|

National Socialist Party |

0.6% |

1.8% |

|

Worker's Party Bangladesh |

0.3% |

2.1% |

Source: IFES Election Guide: People's Republic of Bangladesh; NDI; CNN; Brookings Institution.

Note: Percentages are rounded to the nearest tenth.

a. The BNP boycotted the 2014 vote.

b. The Jatiya Party has several factions.

c. JI was disqualified from taking part in the 2014 election after its charter was found to be in violation of Bangladesh's constitution.

International Crimes Tribunal

|

The Blood Telegram The United States continued to support Pakistan during the events of 1971.73 At the time of the conflict, Archer Blood, the former U.S. Consul General in Dhaka, informed Washington about the scale of the killing—even using the term "genocide." Nevertheless, former President Richard Nixon and former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger "stood stoutly behind Pakistan's generals" and "barely tried to exert leverage over Pakistan's military government."74 Nixon and Kissinger were loath to intervene because they were trying to establish relations with the People's Republic of China, and Pakistan's military leader, General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan, was the liaison between Nixon and Chinese leader Zhou Enlai. Yahya did, in fact, facilitate Kissinger's—and then Nixon's—visits to the PRC, laying the groundwork for improved relations between the two countries.75 |

The International Crimes Tribunal was established in 2009 to try to prosecute those who committed war crimes, such as murder and rape, during Bangladesh's 1971 war of independence from Pakistan.76 The U.S. government has supported bringing Bangladeshi war criminals to justice, and it has encouraged the ICT to follow a "fair and transparent" judicial process.77

Previously, Pakistan (then-West Pakistan) and Bangladesh (then-East Pakistan) were one Muslim-majority country—which came about after the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947.78 During the separatist war between the two territories in 1971, hundreds of thousands to over 1 million people are believed to have died. Perhaps 10 million more were displaced.79 At the time, Bangladesh's independence forces, along with India, were battling the Pakistani army, which largely was composed of troops from then-West Pakistan and their local sympathizers in Bangladesh.80 JI's paramilitary wing, Al-Badr, collaborated with the West Pakistani military, and it reportedly targeted students and politicians, among others, who were sympathetic to Bangladesh's independence struggle.81

As part of the ICT process, a number of leaders from the JI party and the BNP have been arrested and accused of war crimes. Several have been convicted and executed.82 The BNP and JI have opposed the ongoing trials and view them as being part of an AL effort to further consolidate its political advantage.83 According to Human Rights Watch, the trials favor the prosecution, and the defense often does not have a chance to "challenge the credibility of prosecution witnesses."84

According to the State Department, the court has carried out five executions from 2010 through 2016. Four of those individuals were JI members; the other one was from the BNP.85 In May 2016, the ICT executed Matiur Rahman Nizami, the Amir (or President) of JI.86 As mentioned above, in April 2017, the ICT also handed down death sentences to two people who were convicted of committing war crimes during the 1971 war.87

While some observers have been critical of the ICT's use of the death penalty, others have welcomed the strong stance against Islamist extremism. One commentator has observed that "Western governments have been lukewarm to hostile" to the April 2015 execution of senior JI leader Muhammad Kamaruzzaman for his role in war crimes:

[T]hough Bangladesh has addressed many concerns about its trials, judicial standards certainly don't match those of Denmark or Switzerland. Yet the chorus of criticism in Western capitals ends up serving a perverse purpose. It strengthens precisely those groups in Bangladesh who most threaten human rights, individual liberty and religious freedom. [Those concerned with human rights] ... ought to applaud Bangladesh for showing pluck to take on a thuggish Islamist movement....88

Following Kamaruzzaman's execution, the State Department issued a statement, saying that the United States supports "bringing to justice those who committed atrocities in the 1971 Bangladesh War of independence." However, the statement also emphasized that the ICT process "must be fair and transparent."89

Human Rights

Many observers view politically motivated violence—perpetrated by both opposition- and government-aligned forces—as one of the key threats to human rights in Bangladesh. The United States has expressed concern over the country's political unrest, as well as its lack of labor-rights protections.90 According to the U.S. Department of State's 2016 Human Rights Report:

The most significant human rights problems [in Bangladesh] were extrajudicial killings, arbitrary or unlawful detentions, and forced disappearances by government security forces; the killing of members of marginalized groups and others by groups espousing extremist views; early and forced marriage; gender-based violence, especially against women and children; and poor working conditions and labor rights abuses.91

More than 500 Bangladeshis died in "2014 election-related violence" and, as mentioned above, Odhikar, the human rights group, reported that 215 people were killed and that 9,050 were injured because of inter- or intra-party clashes in 2016.92

Unlawful detentions also have occurred, as have forced disappearances. In 2016, Mir Ahmed Bin Quasem and Hummam Quader Chowdhury—the sons of prominent figures in the JI and BNP, respectively—were detained and held without charge.93 They did not have access to lawyers or their families. Hummam Quader Chowdhury was later released in March 2017, but, according to recent reports, Mir Ahmed Bin Quasem still has not been seen.94 (Notably, both men's fathers were executed by the ICT.)95 Over the course of eight days in 2016, Bangladesh's security forces rounded up nearly 15,000 people, following a series of attacks against liberal activists.96 Many of the detainees were, according to Human Rights Watch, members of the political opposition, including JI's student wing.97 Additionally, the AL government reportedly has filed 37,000 lawsuits against the BNP.98

The Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) is an elite unit of Bangladesh's security forces that has been implicated in a number of human rights violations. The AL government has reportedly used accusations of terrorist activity, seen by many as unfounded, to mobilize the RAB against elements within the opposition, including JI members.99 (The BNP also reportedly used the RAB as a "death squad" when it controlled the government.)100 Amnesty International found that, of the 20 disappearance cases it investigated between 2012 and 2014, several seemed to suggest that the police or RAB were involved.101 In the first nine months of 2016, between 118 and 150 individuals were killed in "crossfire" incidents—which are deaths resulting from purported shootouts between suspects and security forces. The RAB, allegedly, was responsible for 34 of those deaths. Observers say that the "crossfire" incidents are likely extrajudicial killings.102 In January 2017, the Narayanganj District and Sessions Court "sentenced 26 people, including 16 RAB members, to death for their role" in the killing of a local politician. However, such convictions are rare.103

Bangladesh has of late been clamping down on the country's media, according to observers. In 2016, two editors—who worked for leading newspapers in the country—were charged with several crimes, including criminal defamation and sedition.104 Since 2013, the staff of one of those newspapers, Prothom Alo, has faced more than 100 criminal cases.105

Freedom of expression has come under increasing threat from Islamist extremists in Bangladesh—as evidenced by the recent killing of Dr. Avijit Roy, a secular blogger who was Bangladeshi-American.106 He was killed by an Islamist extremist group and, in the view of one analyst, Roy's murder, and others like it, "have opened a new front between the values of syncretic, secular, humanistic Bangladeshi culture against a rigid worldview incapable of allowing difference to coexist."107 Although Bangladesh was founded as a secular country, some say that Islamist extremists have discredited secularism in the eyes of many Bangladeshis.108 "The politics has been turned into the secular versus the Islamists," according to Abdur Rashid, who is a retired army major general and the executive director of the Institute of Conflict, Law and Development Studies in Dhaka.109

Bangladesh has struggled with inter-religious tensions and violence, particularly between Islamist extremists and Hindus. Muslims account for about 89.1% of Bangladesh's population. Hindus account for 10.0%. Other religious groups, including Buddhists and Christians, account for about 0.9%.110 (When Bangladesh gained independence in 1971, Hindus were about 23% of the population.)111 According to the Hindu American Foundation, 495 Hindu homes, 169 temples, and 585 shops were attacked, damaged, or looted in 2014 election-related violence.112 In spring 2016, three Hindu priests were killed.113 There also have been attacks on the country's Buddhist, Christian, and Ahmadiyya communities.114 According to the advocacy group Hindu-Buddha-Christian-Oikya Parishad, in the first three months of 2016, there were three times as many violent incidents involving minorities than in all of 2015.115

Human trafficking and unequal rights for women are problems in Bangladesh, as well. While there is a lack of reliable quantitative data, "human trafficking in Bangladesh is believed to be extensive both within the country and to India, Pakistan and the Middle East."116 Many, including children, are reportedly trafficked into sexual exploitation or forced labor. According to the State Department's Trafficking in Persons Report for 2017, "Observers reported police took bribes and sexual favors to ignore potential trafficking crimes at brothels." The report places Bangladesh on the Tier 2 Watch List.117 In March 2017, Bangladesh's parliament passed a law making it legal for girls under the age of 18 to marry. Already, around 52% of Bangladeshi girls are married by the time they are 18, and 18% are married by age 15.118 The government, observers believe, pushed the bill to increase its popularity among religious groups.119

Child labor is a problem in Bangladesh, as well. In December 2016, the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), a U.K.-based think tank, conducted a survey, examining the prevalence of child labor in eight slum settlements in Dhaka. The results suggested that child labor was "endemic" in the area, affecting 45% of 14-year-old children. (Child labor—as defined by ILO—is work that "deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development.") Another survey—conducted in 2013 by the government—reported that about 3.5 million children aged 5 to 17 were working, including 1.7 million as child laborers.120

Rohingya121

In Burma, the Rohingya, a Muslim minority group, have faced persecution at the hands of the majority Buddhist population.122 Burma views the Rohingya as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, and tensions between Burma's Rohingya and Buddhist communities remain high, especially in Arakan (Rakhine) State.123 Since August 2017, an estimated half a million Rohingya have crossed the border into Bangladesh, fleeing from the latest outbreak of violence in Rakhine.124 In September 2017, the United Nations high commissioner for human rights condemned Burma, saying that the government was "carrying out 'a textbook example of ethnic cleansing' against the Rohingya."125 On September 20, 2017, the United States pledged to spend nearly $32 million on an aid package to help displaced Rohingya—in addition to the nearly $63 million that the U.S. government already has provided in humanitarian assistance "for vulnerable communities displaced in and from Burma" since October 2016.126

Violence in Arakan (Rahkine) State

The latest outbreak of violence began in August 2017 when Rohingya insurgents—called the Arakan Rohingya Solidarity Army (ARSA)—carried out attacks against Burmese police and military outposts.127 Afterward, the Burmese security forces launched "'clearance operations' to root out the insurgents." However, the security forces allegedly have been targeting civilians and burning Rohingya villages. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have been displaced and have crossed the border into Bangladesh.128

Previously, in October 2016, Rohingya militants attacked Border Guard Police bases in Burma and killed nine officers.129 In response, Burma's security forces conducted a campaign in Rakhine State. It was, observers say, a "disproportionate" response, affecting a large portion of the population. Human rights groups released a series of reports, documenting alleged abuses, including extrajudicial killings and mass rapes "associated with [Burmese] military operations."130 To escape the security forces' crackdown, about 74,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh where they were not granted refugee status.131

According to Refugees International, before the most recent influx of an estimated 480,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh, there were three categories of displaced Rohingya in the country: (1) 33,000 government-recognized refugees; (2) 200,000-500,000 Rohingya living in Bangladesh as Undocumented Myanmar Nationals (UMN); and (3) 74,000 Rohingya—also considered UMN—who fled Burma between October 2016 and February 2017. (Under Bangladeshi law, the UMN are illegal foreigners residing in the country.)132 Since the UMN are technically stateless—and in turn lack access to state protections and services—they are vulnerable to exploitation and human trafficking.133

In 2015, the plight of the Rohingya and some Bangladeshis similarly gained international attention when many of them took to the sea to escape persecution and to find a better life. According to some accounts, armed groups of Buddhists in Burma forced Rohingya to get on migrant boats and leave the country. It is estimated that 25,000 Southeast Asian migrants—including those from Burma and Bangladesh—"took to the seas" during the first three months of 2015.134

Possible Militant Ties

There is much uncertainty related to ARSA and the extent to which it has outside support. ARSA has denied that it has ties to international terrorist groups and portrays itself as an ethno-nationalist group seeking to defend its own people.135 Despite this, some observers view ARSA as a militant group with possible links to international terrorists.136 Others emphasize that the recent attacks against the Rohingya have created a situation that may present opportunities for recruitment of Rohingya by international terrorist organizations, such as the Islamic State (IS), even if ARSA itself has no ties to such groups.137

An International Crisis Group (ICG) report from December 2016 described the emergence of a Muslim insurgent group called the Harakah al-Yaqin (HaY), now known as the ARSA. ICG described HaY as led by a committee of Rohingya emigres in Saudi Arabia and as a group without a terrorist agenda. The ICG report warned that a disproportionate response by Burma "could create conditions for further radicalizing sections of the Rohingya population."138 Unconfirmed Indian media reports point to ties between elements within the Rohingya community and Pakistan's ISI, as well as with Pakistan- and Bangladesh-based terrorist groups.139 Even if ARSA has no links with terrorist groups, the presence of so many dispossessed and abused Rohingya in Bangladesh would appear to make it a fertile ground for recruitment for terrorist groups.140 It is Bangladesh's policy not to allow ARSA to establish a base in Bangladesh, and the country's Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Mohammed Shahriar Alam, has stated that the Rohingya present a security issue as well as a humanitarian issue and that Bangladesh would take prompt action if ARSA tries to enter the country.141

U.S. Government Response to the Rohingya Crisis

The United States has called on Burma to protect its Rohingya population. In July 2017, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley called on Burma to allow a human rights fact-finding mission into the country. "The international community," she said in a statement, "cannot overlook what is happening in" the country.142 In September 2017, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Southeast Asia Patrick Murphy called on the Burmese government to implement the suggestions proposed by the Rakhine Commission. Previously established by the Burmese government, the commission was tasked with "finding conflict-prevention measures, ensuring humanitarian assistance, rights and reconciliation … and promoting long-term development plans in the restive state."143 Some analysts have criticized the U.S. government for not doing enough to protect the Rohingya.144

Legislation introduced in Congress would condemn the human rights abuses in Rakhine state, call on Burma's leaders to end persecution of the Rohingya, and possibly impose foreign assistance sanctions. The Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2018 (S. 1780) stipulates that Economic Support Funds to Burma may not go to any "individual or organization [that] has committed a gross violation of human rights, including against Rohingya and other minority groups." The bill further specifies that "None of the funds appropriated ... under the headings "International Military Education and Training" and "Foreign Military Financing Program" may be made available for assistance for Burma."145 H.Res. 528 and S.Res. 250 would condemn "horrific acts of violence against Burma's Rohingya population" and call upon Aung San Suu Kyi "to play an active role in ending this humanitarian tragedy."146 Representative Edward Royce, chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, issued a letter to Suu Kyi. "Your government and the military," it read, "have a responsibility to protect all of the people of Myanmar [Burma], regardless of their ethnic background or religious beliefs."147

Bangladesh Government Response to the Rohingya Crisis

The government of Bangladesh has opened its borders, admitting an estimated half a million Rohingya since August 25, 2017.148 Bangladesh's capacity to accommodate the latest influx of Rohingya is limited. It already had an estimated 400,000 Rohingya living in the country, and many Rohingya are living in the open—outside of official camps in the border area with Burma. However, Bangladesh is establishing a new camp for the Rohingya, in addition to two existing official camps. The new camp is planned to have 14,000 shelters, each of which reportedly will be able to accommodate six families.149 Bangladesh has also considered a plan to relocate Rohingya to Thengar Char Island in the Bay of Bengal. However, the island is considered "uninhabitable" and is "prone to flooding."150 Respiratory infections, diarrhea, dysentery, and other ailments are reportedly spreading among the Rohingya in Bangladesh, and there is a great need for clean drinking water, food, and sanitation. Foreign Secretary M. Shahidul Haque has stated that Bangladesh considers the Rohingya to be "forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals" and not migrants, or illegals or refugees.151 Bangladesh has called on Burma to repatriate the displaced Rohingya and on international organizations to assist Bangladesh in caring for the Rohingya until they can return to Burma.

Bangladesh has reportedly started biometric registration of Rohingya at camps near Cox's Bazar. Bangladesh's government previously worked with NGOs on immunization campaigns, and in 2014, it came up with a strategy that "led to expanded access and protection services" for Rohingya migrants who are not recognized as refugees.152 In September 2017, the U.S. State Department issued a statement, saying that the United States "applaud the government of Bangladesh's generosity in responding to this humanitarian crisis and appreciate their continued efforts to ensure assistance reaches the affected population."153 However, in the past, some international human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch criticized Bangladesh, saying its government forced back Rohingya fleeing from Burma and placed restrictions on international aid organizations operating in the country.154

An estimated 8 million to 10 million Bangladeshis fled to India in 1971 in the wake of atrocities committed by the West Pakistan army and local sympathizers in East Pakistan during Bangladesh's struggle for independence. Hundreds of thousands of Bengalis died during this conflict. This experience informs many Bangladeshis' sympathetic perspective on the plight of the Rohingya.

Labor Issues/Factory Safety155

Workers' rights and safety in Bangladesh have been the focus of much international attention, particularly in the apparel-production industry. In June 2013, the United States suspended Bangladesh's designation as a beneficiary country under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) program over concerns about workers' rights in the country. As a result, U.S. imports of GSP-eligible products from Bangladesh lost their duty-free status.156 So far, the United States has not reinstated Bangladesh's GSP benefits.

Bangladesh is an important part of the global textile-supply chain, and its garment industry employs approximately four million workers.157 Yet successive factory disasters have led to additional global and U.S. scrutiny of Bangladesh's labor rights regime, especially following the Rana Plaza garment factory collapse which killed over 1,000 workers in April 2013.158 The Rana Plaza factory provided clothing to several European and American brands, reportedly including Children's Place, Benetton, Cato Fashions, and Mango.159 As of April 2017, many victims' families still had not been compensated, even though a $30 million fund was established to do just that following the disaster.160 (Reportedly, several international brands and retailers paid less than expected into the fund.)161 In 2015, Bangladesh police charged the owner of the Rana Plaza factory and 41 others with murder, and in August 2017, he was sentenced to three years in jail.162

Many Bangladeshi factories reportedly are substandard and unsafe. Following the Rana Plaza collapse, inspections were conducted as part of the Accord for Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh—an initiative involving over 180 brands and retailers, reportedly including H&M.163 The inspectors discovered safety hazards in all of the 1,106 garment factories that were examined and requested that Bangladeshi authorities immediately evacuate 17 factories.164 In 2013, the International Labour Organization (ILO) started an initiative—the Improving Fire and General Building Safety in Bangladesh project—to train building inspectors and improve the capabilities of Bangladesh's Fire Service and Civil Defence (FSCD) force.165 (The U.S. Department of Labor funded the project.)166 A 2016 fire broke out at a packaging factory in Tongi, north of Dhaka, killing 23 people.167

It is difficult to unionize in Bangladesh. A June 2017 report from the International Trade Union Confederation indicated that there were few to any guarantees of worker rights in Bangladesh, and the organization ranked the country among the 10 worst, in terms of worker-rights protections. Some 10% of the country's garment factories are unionized, and registering to create a union is difficult, in part because at least 30% of the workforce—"a relatively high level"—must agree to it.168

Bangladesh's economy relies heavily on foreign remittances, and the government has tried to protect its citizens working abroad. A bilateral treaty with Saudi Arabia, for instance, stipulates that Saudi Arabian employers must pay for Bangladeshi female workers' travel expenses and that domestic workers must be employed by a third party, not by a private household.169 However, according to the U.S. State Department's 2017 Trafficking in Persons Report, Bangladesh's government has allowed the Bangladesh Association of International Recruiting Agencies to set high recruitment fees, thereby making many laborers "indebted and vulnerable to trafficking."170

Despite labor rights abuses, the garment industry has provided many Bangladeshi women with opportunities that have given them some independence. Many women in Bangladesh work in the garment sector—which accounted for over 80% of the country's exports in 2016.171 According to an ILO study, about 41% of Bangladeshi women are employed—a much higher rate than in India (25.8%) and Pakistan (22%).172 It reportedly has become "more culturally acceptable for women to enter the labour force in general" in Bangladesh, and currently about 80% of the country's garment employees are women.173 That has "served as a repellant against early marriage and in turn reductions in fertility."174

Peacekeeping

Bangladesh is today consistently one of the largest contributors of troops, police, and experts to United Nations international peacekeeping efforts. Bangladesh began peacekeeping operations in 1988. As of July 2017, more than 6,900 of the country's troops and police were serving in 13 U.N. peacekeeping operations.175 Many of Bangladesh's troops have served as U.N. peacekeepers in Africa, including in the Central African Republic and in the Democratic Republic of Congo.176 In September 2017, three U.N. soldiers from Bangladesh were killed in Mali.177

Through the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI), which is United States' primary security assistance program for strengthening international capacity and capability to train, sustain, deploy, and effectively conduct peacekeeping operations around the world, the United States is helping Bangladesh to open a new multipurpose training facility at the Bangladesh Institute for Peace Support Operation Training (BIPSOT).178 In his remarks while visiting the BIPSOT in 2011, then-U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon observed that approximately 1 in 10 United Nations peacekeepers were from Bangladesh before noting their sacrifice for the global good.179

Economic Development and Trade

Although it remains one of the world's poorest nations, Bangladesh has experienced significant GDP growth over the past decade, expanding at about 6% per year since 1996.180 The Economist Intelligence Unit projects that Bangladesh's real GDP will grow by about 6.4% in 2017/2018 through 2020/21.181 However, more will likely need to be done to accommodate the number of Bangladeshis entering the workforce. About 2.1 million youths enter the job market every year, according to one senior World Bank official, and it is seen as vital that the country creates more jobs for them.182 Nearly half of Bangladeshis work in the agriculture sector.183

Manufacturing—particularly of ready-made garments—is a key component of Bangladesh's economy. Bangladesh is the second-largest exporter of ready-made garments in the world after China.184 In 2016, garment exports exceeded $25 billion, accounting for more than 80% of the country's total exports.185

Bangladesh's economy is one of the world's most dependent on foreign remittances. About $15 billion in remittances came from Bangladeshis working overseas in 2015 constituting the country's largest source of foreign-exchange earnings.186 However, during the 2016-2017 fiscal year, remittances fell by 14.5% from the previous fiscal year—a drop from about $15 billion to $12.8 billion. According to analysts, the reported drop is in part the result of expatriate workers sending their remittances through informal channels, such as mobile banking and the hundi, which is an illicit fund-transferring system.187 Many of the new migrant workers went to Saudi Arabia.188 Estimates of the number of Bangladeshis working abroad vary. By one estimate Bangladesh will send an estimated 1 million workers abroad in 2017.189

Bangladesh's Energy Regulatory Commission (BERC) reportedly announced that gas prices would be raised by an average of 22.7% in 2017.190 The decision was met with protests, but it was necessary, according to one BERC official, because gas was sold at half its actual cost and the subsidies were unsustainable.191 The hike was supposed to take place in two phases, but the second price increase has been held up by the courts.192 Bangladesh relies on liquefied natural gas (LNG) to cover 53% of its energy needs, and the country's gas reserves will last for another 10 to 12 years, according to some analysts. At present, Bangladesh "is developing an import terminal"—the Moheshkhali Floating LNG project—with the International Finance Corporation and Excelerate Energy, a U.S.-based company.193

Recently, the IMF reported that the banking sector faces "underlying risks," partially because of large loans that were made to borrowers who have few incentives to repay. In June 2017, the government set aside $250 million to recapitalize the country's state-owned banks.194 However, according to some observers, the country's regulators have not been effective at tackling the sector's underlying problems, such as poor risk management and few penalties being levied on defaulters.195 Partially as a result, state-owned banks have a "high level" of nonperforming loans—in other words, loans that are in default or are close to being in default—and operating profits at Bangladesh's six state-owned commercial banks fell by 37% in 2016.196

According to the World Bank's 2017 Doing Business Index, Bangladesh ranked 176th out of 190 countries. Major problems include difficulties for businesses in Bangladesh to get access to electricity and to get contracts enforced.197 (About 60 million people—or about 40% of Bangladesh's population—do not have access to electricity.)198 The country also has a poor infrastructure-transportation network, and according to Transparency International's 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index, Bangladesh ranked 145th out of 176 countries.199 In May 2017, the cabinet approved legislation that would make it easier for businesses to get licenses, register land, and link with utilities. Known as the One-Stop Service Act, parliament must approve the legislation before it can take effect.200

In 2016, the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development reported that Bangladesh received $2.3 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2016—a record amount—but some observers say that the country could attract more FDI if it improved its infrastructure, streamlined its bureaucracies, and tackled corruption.201

|

|

Source: UN Comtrade Database (Accessed August 2017), Foreign Trade Online. Adapted by CRS. |

Environmental, Climate, and Food Security

Demographic pressures and environmental problems—including those linked to climate change—increasingly are challenges for Bangladesh, and they may result in thousands, perhaps millions, of people being displaced in future years. If that does happen, many of these people likely will move to crowded cities or to neighboring countries, such as India, leading to further strains on social services and, perhaps, regional instability.

The 2015 Climate Change Vulnerability Index reported that Bangladesh's economy is the most vulnerable in the world to climate change.202 About 80% of the country's land mass is on a floodplain and is less than 5 meters (some 16 feet) above sea level.203 It has been projected that seas near Bangladesh could rise by as much as 13 feet by 2100—which is four times the projected global average.204 According to an Institute of Medicine study released in January 2017, between 2011 and 2050, about 9.6 million people in Bangladesh may be displaced because of climate change.205 Some scientists suggest that rising sea levels—along with additional factors, such as land settling because of groundwater extraction—will lead to 17% of Bangladesh's land being inundated and will potentially displace up to 18 million people by 2050.206 Many of the displaced may move to the country's cities, including Dhaka.207 In recent years, 50,000 to 200,000 people have been displaced annually due to riverbank erosion.208 Moreover, some analysts believe cyclones likely will become more intense.209 One cyclone—Cyclone Mora—forced the evacuation of 350,000 people in 2017.210

Bangladesh's population is projected to increase from about 160 million people to around 200 million in 2050. Population increases may lead to further internal displacement, cross-border migration, and potentially rising tensions between the country and its neighbors, including India.211 Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries on earth with around 1,120 people per square kilometer.212

Bangladesh's government has invested more than $10 billion to address the potential effects of climate change, and much of that funding has gone toward strengthening river embankments, implementing early warning systems, improving government capacities, and building emergency cyclone shelters.213 To date, 2,500 such shelters have been built.214 Bangladesh's government also has discussed the possibility of imposing a carbon tax on fossil fuels.215

According to EIU's 2016 Global Food Security Index, Bangladesh ranks second-to-last in food security among the 23 countries of the Asia and Pacific region. (Laos is the lowest-ranked country). Of the 113 countries ranked in the Index, Bangladesh ranked 95th. Bangladesh's total score, though, did improve from 2015.216 One USDA Foreign Agriculture Service member is reported to have said that "the food safety environment in Bangladesh was ... among the worst he has observed globally."217 Indeed, Bangladesh has the "highest prevalence of underweight children in South Asia," and more than half of the population does not have access to clean water and sanitation.218

Bangladesh is the world's fourth-largest rice producer, but much of the crop is consumed domestically, and according to USAID, Bangladesh remains "food deficient.219 In April 2017, flash floods reportedly "damaged over 700,000 tons of rice." (Unofficial estimates suggest that around 2.2 million tons may have been damaged.)220 Overall, rice accounts for "about two-thirds of the population's dietary intake."221 Some studies suggest that Bangladesh's rice production may decrease by 8% by 2050 due to the effects of climate change, including increased salinity levels along the coast.222 In some areas—particularly the north—droughts already seem to be becoming more common, and rising salinity levels in the Barisal Division in the southwest has made agriculture unprofitable, resulting in internal migration, particularly to Dhaka.223

The Ministry of Food monitors the government's rice reserves—which are meant to provide price support to rice farmers, if need be—but the reserves have decreased during the last year, in part because of a government-imposed 25% import duty.224 In June 2017, the government lowered the duty to 10%, following flash floods and an outbreak of rice-blast disease that led to soaring rice prices. Originally, the higher-rate rice duty was imposed to protect farmers from cheap Indian rice.225

In Bangladesh, waterways and rivers are used as transportation networks, and some projects—including one from the World Bank—have worked to ensure that these waterways remain resilient to the potential effects of climate change.226 Recently, because of seasonal changes in water levels, Bangladesh's government has resorted to dredging to keep waterways open.227 For instance, the Gorai River is a major source of freshwater for southwest Bangladesh, and it collects water from the Ganges. Yet, during the dry months, the Gorai becomes disconnected from the Ganges, causing a decrease in its freshwater flow. The government launched the Gorai River Restoration Project in 2009 to dredge and, ultimately, reconnect the two rivers. However, as of April 2017, some accounts suggest that the project has not been particularly successful.228

Regional Issues

Islamist Extremism

The U.S. and Bangladeshi governments see a common interest in working to counter extremist Islamists and their ideology. Bangladesh participates in the U.S. State Department's Antiterrorism Assistance program, which provides participating states with counterterrorism training and equipment, and the United States and Bangladesh signed the Counterterrorism Cooperation Initiative in 2013.229 In July 2016, the State Department sent Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs, Nisha Desai Biswal, to Dhaka to discuss U.S.-Bangladesh counterterrorism cooperation.230 The 2016 U.S. State Department Country Report on Terrorism states that

Bangladesh experienced a significant increase in terrorist activity in 2016. The Government of Bangladesh has articulated a zero-tolerance policy towards terrorism, made numerous arrests of terrorist suspects, and continued its counterterrorism cooperation with the international community.231

There are signs that transnational terror networks operate in Bangladesh. In January 2014, Bangladeshi police arrested three suspected members of Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)—otherwise known as the Pakistani Taliban.232 Between September 2014 and October 2015, about 15 people with alleged links to IS were arrested in Bangladesh.233 In April 2016, a local employee at the U.S. Embassy was killed, along with a friend, and Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) claimed responsibility.234 The Islamic State also has "claimed more than two dozen attacks in Bangladesh since September 2015." One of the attacks killed over 20 people at Dhaka's Holey Artisan Bakery in July 2016.235 The bakery—which is near the U.S. Embassy—was a popular site with expatriates, and several foreigners were killed, including nine Italians, seven Japanese, one U.S. citizen, and one Indian.236

The full extent to which domestic Islamist groups have links with the IS or other international terrorist groups is unclear. Bangladesh's government was reluctant to blame IS for the Holey Artisan Bakery attack. Rather, it accused Jama'atul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB), a domestic militant group, of carrying out the assault, and it tried to minimize the group's links with IS.237 (The government banned JMB in 2005.) An aide to Sheikh Hasina said: "[The Islamic State is] not an organized group here. People with Islamic State links are here. But that is not to say [the] Islamic State is here."238

According to some observers, the government wants to downplay IS's presence in Bangladesh because it is trying to use the alleged threat of domestic militancy "as an excuse to stifle dissent."239 One observer pointed out:

[Choosing a] name decides who takes action against the [terrorist] organization and thereby who reaps the political fruits of its annihilation…. Call it Islamic State and the reins go into the hands of the international community. Naming it neo-JMB makes it home grown and therefore the reins stay in the hands of Sheikh Hasina. And when she keeps saying "BNP-Jamaat BNP-Jamaat," it builds the ground for effectively annihilating the political opposition in the name of fighting terrorists.240

After the bakery attack, some information came to light suggesting that IS had developed connections with Bangladeshi militants. For instance, IS knew about and approved the attack before it was carried out, according to some reports.241 Tamim Ahmed Chowdhury—who reportedly was an IS coordinator in Bangladesh and the leader of a JMB branch—praised the attackers "as fallen comrades."242 (In August 2016, Bangladeshi security forces killed Chowdhury in a shootout.)243 Some observers say that JMB has "'essentially repurposed' itself by trying to link itself to ISIS."244 However, some analysts point out that IS likely played little, if any, direct role in planning the Holey Artisan Bakery attack.245

Increasingly, in Bangladesh, terrorists are using different or bolder tactics. In the past, Bangladeshi militants often would ambush their targets or detonate bombs—in 2005, for instance, JMB detonated bombs in 63 of Bangladesh's 64 districts.246 But during the assault on the Holey Artisan Bakery, the attackers did not retreat. Rather, they stood their ground until they were killed by security forces.247 As one journalist observed, "Taken together, the attacks in the second half of 2016 pointed to a whole new level of indoctrination. Where Islamists of the past had killed in the name of religion, the new breed was willing to die for it."248 More recently, in March 2017, IS claimed responsibility for a suicide-bomber attack on the Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport, as well as a failed attack on the Rapid Action Battalion barracks in Dhaka.249

Harkat-ul-Jihad-al Islami Bangladesh (HUJI-B) is another U.S.-designated Islamist terrorist group in the country, and it is considered the "fountainhead of the militant groups in Bangladesh."250 The U.S. State Department reports that HUJI-B is believed to have links with Al Qaeda and with official elements in Pakistan, including Pakistani ISI operatives.251 According to the Delhi-based South Asia Terrorism Portal, HUJI-B operations commander, Mufti Abdul Hannan, trained in Peshawar, Pakistan before going to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan. HUJI-B has been linked to the Asif Reza Commando Force, which claimed responsibility for a 2002 attack against the American Center in Kolkata.252 Dhaka banned HUJI-B in 2005. In March 2017, the Supreme Court upheld the death sentence for Hannan. He was sentenced to death due to his role in a 2004 attack on the U.K. high commissioner to Bangladesh. The attack killed three police officers. Seventy other people were injured, but the high commissioner escaped without injury.253

Other events have shed light on evolving terrorist networks in the region. In October 2014, for instance, an accidental bomb explosion in the Burdwan District of Indian West Bengal killed two suspected members of JMB and wounded another. Members of JMB reportedly have infiltrated from Bangladesh into India's border districts where they have sought out new recruits in several madrassas.254 Also, since several militant groups have been banned—including HUJI-B and JMB—their members have gone on to form other groups. One of these groups, Jund al-Tawheed wal Khilafah (JTK), has operatives who are former JMB members.255

Islamist extremists also have targeted secular activists and bloggers, such as Avijit Roy. The Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT)—which has links to al-Qaeda and is now a banned organization—created a "hit list of 84 'atheist' bloggers," leading to the murders of several liberal activists, including secular blogger Nazimuddin Samad in April 2016.256 The assailants were members of Ansar al-Islam, which, according to police, has links with AQIS and grew in part from ABT.257 (For a description of Bangladesh's terrorist groups and their links with IS and AQIS, see Table 2.)

Nevertheless, the AL government has tried to placate some of the country's Islamists. It has, for example, pledged to build a mosque in every town, making use of a $1 billion gift from Saudi Arabia.258 These gestures, Sheikh Hasina's son reportedly admitted, are meant to shield the AL from religious criticism.259

At present, there is an ongoing struggle over secularism in Bangladesh. By some accounts, Islamists have largely discredited secularism in the eyes of many Bangladeshis. The chief of Bangladesh's police counterterrorism unit, Monirul Islam, observed that, "'In general, people think they have done the right thing, that it's not unjustifiable to kill' the bloggers, gay people and other secularists."260

|

Groups Believed to Be Affiliated with IS |

Groups Believed to Be Affiliated with AQIS |

|

Jama'atul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) emerged in 1998. It aimed to establish an Islamic state in Bangladesh. In 2005, it launched a series of coordinated attacks around the country, involving about 500 bombs. The group was banned in 2005. However, several offshoots have emerged, including one that goes by the acronym BEM. Many JMB members support the IS, and there reportedly has been communication—and perhaps some coordination—between JMB leaders and the IS. The Bangladesh government has blamed the JMB for several attacks, including for the one on the Holey Artisan Bakery in Dhaka.261 Jund al-Tawheed wal Khilafah is a relatively new group, and little is known about it. However, it is believed to include former JMB members, and it has been accused of recruiting Bangladeshis to join the IS in Syria. |

Ansar al Islam, which used to be known as the Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT), is reportedly an AQIS affiliate in Bangladesh. The group emerged in 2013, and drew inspiration from Anwar al-Awlaki. It has claimed responsibility for several attacks, mainly against secular bloggers and activists, such as Avijit Roy. The Bangladesh government has banned both Ansar al Islam and ABT.262 Harkat-ul-Jihad-al Islami Bangladesh (HUJI-B) was established in the late 1980s with the aim of creating an Islamic state in Bangladesh. Its ranks initially were filled with Islamists, who had fought against the Soviets in Afghanistan, and the group was reportedly linked with Al Qaeda, as well as with Pakistan's intelligence services. HUJI-B carried out a series of attacks against AL politicians and their supporters, and it was—and perhaps still is—connected with other militant groups in Bangladesh, including the JMB. Bangladesh's government banned the group in 2005. One of the most recent HUJI-B offshoots is known as Tanjim-e-Tamiruddin. The U.S. designated HUJI-B a foreign-terrorist organization. Islami Chaatra Sibir (ICS) is the student wing of Jemaat-i-Islami, which was established in 1941. The student group, reportedly, has close links with Pakistan's intelligence services, and it has received funding from Saudi Arabia. Also, the ICS apparently helped to recruit youth to travel to Taliban-controlled Afghanistan where they served under the direct command of Osama bin Laden. |

Geopolitical Context

Positioned at the intersection of India, China, Southeast Asia, and the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh occupies a geo-strategically important location—not only to the South Asian sub-region, but also to Asia as a whole. When Bangladesh gained independence in 1971, it weakened Pakistan's position relative to India and set the stage for India to play a larger role beyond South Asia. Some analysts also have pointed to the area's growing importance as a result of China's Belt and Road Initiative—previously known as the One Belt, One Road Initiative—which emphasizes energy investments, trade and transit linkages throughout the region.263 India and China, according to some observers, are competing for influence in Bangladesh, leading to an uptick in Sino-Indo tensions.264 India, for instance, reportedly is worried that Sino-Bangladeshi energy cooperation has come to exceed Indo-Bangladeshi energy cooperation.265

Bangladesh's foreign policy seeks to promote trade, economic development, and diplomatic linkages. Dhaka is a member of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and values close ties with Muslim states, but it remains a relatively moderate Muslim nation. Bangladesh also is a member of the South Asia Association for Regional Cooperation and the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation, which aims to foster regional collaboration on trade, poverty reduction, and efforts to counter transnational crime and terrorism. Additionally, Bangladesh is a member of the Bangladesh-China-India Myanmar (BCIM) group—which has proposed an economic corridor to connect Kolkata, India, with Kunming, China, to facilitate a more integrated regional economy.266 The group has, however, struggled with internal conflicts—especially between China and India—over market access and trade deficits.267

India

Increasingly, according to observers, China and India are competing for influence in Bangladesh, particularly over trade and energy routes in the region. In 2015, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Bangladesh, leading to a 65-point Joint Declaration that addressed several issues, including cooperation on energy, "cross border transport connectivity," and "zero tolerance" for terrorism or extremism.268 The Joint Declaration "recalled with gratitude India's enormous contribution to the glorious Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971."269 Also, during the 2015 summit, Bangladesh and India signed an agreement clarifying their common border, thereby removing a source of tension between the two countries.270 Historically, India has been more supportive of AL governments, given their more secularist outlooks.271