Conservation Compliance and U.S. Farm Policy

The Food Security Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-198, 1985 farm bill) included a number of significant agricultural conservation provisions designed to reduce farm production and conserve soil and water resources. Many of the provisions remain in effect today, including the two compliance provisions—highly erodible land conservation (sodbuster) and wetland conservation (swampbuster). The two provisions, collectively referred to as conservation compliance, require that in exchange for certain U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) program benefits, a producer agrees to maintain a minimum level of conservation on highly erodible land and not to convert wetlands to crop production.

Conservation compliance affects most USDA benefits administered by the Farm Service Agency (FSA) and the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). These benefits can include commodity support payments, disaster payments, farm loans, and conservation program payments, to name a few. If a producer is found to be in violation of conservation compliance, then a number of penalties could be enforced. These penalties range from temporary exemptions that allow the producer time to correct the violation, to a determination that the producer is ineligible for any USDA farm payment and must pay back current and prior years’ benefits.

A controversial issue in the 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79) debate was whether federal crop insurance subsidies should be included on the list of program benefits that could be lost if a producer were found to be out of compliance with conservation requirements on highly erodible land and wetlands. Ultimately the 2014 farm bill did add federal crop insurance subsidies to the list of benefits that could be lost, but created separate considerations when addressing compliance violations and the loss of federal crop insurance premium subsidies compared with the loss of other farm program benefits. How compliance is calculated, where compliance provisions apply, and traditional exemptions and variances were not amended. The 2014 farm bill also extended limited protection for native sod in select states.

The levels of interest and debate generated by the changes to conservation compliance in the 2014 farm bill are likely to continue with implementation, raising additional questions and oversight in Congress. Recent concerns about a growing backlog of wetland determinations in the Northern Plains and approaching compliance deadlines for crop insurance policyholders have been raised. Additionally, the reduction in soil erosion from highly erodible land conservation continues, but at a slower pace than following the enactment of the 1985 farm bill. The leveling off of erosion reductions leaves broad policy questions related to conservation compliance, including whether an acceptable level of soil erosion on cropland has been achieved; whether additional reductions could be achieved, and, if so, at what cost; and how federal farm policy could encourage additional reductions in erosion.

Conservation Compliance and U.S. Farm Policy

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Conservation Compliance Today

- Sodbuster

- Swampbuster

- Sodsaver

- Affected Program Benefits

- Implementation

- Issues for Congress

- Wetland Determinations

- 2014 Farm Bill Implementation

- Crop Insurance

- Wetland Mitigation Banking and Violations

- Oversight

- Erosion and Conversion Rates

- Conclusion

Tables

Summary

The Food Security Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-198, 1985 farm bill) included a number of significant agricultural conservation provisions designed to reduce farm production and conserve soil and water resources. Many of the provisions remain in effect today, including the two compliance provisions—highly erodible land conservation (sodbuster) and wetland conservation (swampbuster). The two provisions, collectively referred to as conservation compliance, require that in exchange for certain U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) program benefits, a producer agrees to maintain a minimum level of conservation on highly erodible land and not to convert wetlands to crop production.

Conservation compliance affects most USDA benefits administered by the Farm Service Agency (FSA) and the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). These benefits can include commodity support payments, disaster payments, farm loans, and conservation program payments, to name a few. If a producer is found to be in violation of conservation compliance, then a number of penalties could be enforced. These penalties range from temporary exemptions that allow the producer time to correct the violation, to a determination that the producer is ineligible for any USDA farm payment and must pay back current and prior years' benefits.

A controversial issue in the 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79) debate was whether federal crop insurance subsidies should be included on the list of program benefits that could be lost if a producer were found to be out of compliance with conservation requirements on highly erodible land and wetlands. Ultimately the 2014 farm bill did add federal crop insurance subsidies to the list of benefits that could be lost, but created separate considerations when addressing compliance violations and the loss of federal crop insurance premium subsidies compared with the loss of other farm program benefits. How compliance is calculated, where compliance provisions apply, and traditional exemptions and variances were not amended. The 2014 farm bill also extended limited protection for native sod in select states.

The levels of interest and debate generated by the changes to conservation compliance in the 2014 farm bill are likely to continue with implementation, raising additional questions and oversight in Congress. Recent concerns about a growing backlog of wetland determinations in the Northern Plains and approaching compliance deadlines for crop insurance policyholders have been raised. Additionally, the reduction in soil erosion from highly erodible land conservation continues, but at a slower pace than following the enactment of the 1985 farm bill. The leveling off of erosion reductions leaves broad policy questions related to conservation compliance, including whether an acceptable level of soil erosion on cropland has been achieved; whether additional reductions could be achieved, and, if so, at what cost; and how federal farm policy could encourage additional reductions in erosion.

Federal policies and programs traditionally have offered voluntary incentives to producers to plan and apply resource-conserving practices on private lands. It was not until the 1980s that Congress took an alternative approach to agricultural conservation through enactment of the Food Security Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-198, 1985 farm bill). The bill's more publicized provisions—the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP),1 highly erodible land conservation (sodbuster), and wetland conservation (swampbuster)2—remain significant today. The latter two "conservation compliance" provisions require that in exchange for certain U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) program benefits, a producer agrees to maintain a minimum level of conservation on highly erodible land and not to convert wetlands to crop production.

The Agricultural Act of 2014 (2014 farm bill, P.L. 113-79) added federal crop insurance subsidies to the list of program benefits that could be lost if a producer were found to be out of compliance with conservation requirements on highly erodible land and wetlands. Compliance violations related to the loss of federal crop insurance premium subsidies now have separate considerations from violations related to the loss of other farm program benefits. How compliance is calculated, where compliance provisions apply, and traditional exemptions and variances were not amended. The 2014 farm bill also extended limited protection for native sod in select states.

Conservation Compliance Today

The 1985 farm bill included a number of significant conservation provisions designed to reduce crop production and conserve soil and water resources. The highly erodible land conservation provision (sodbuster) introduced in the 1985 farm bill was not intended to "allow the Federal government to impose demands on any farmer or rancher concerning what may be done with their land; ... only that the Federal government will no longer subsidize producers who choose to convert highly erodible land to cropland unless they also agree to install conservation system(s)."3 Similarly, the wetland conservation provision introduced in the 1985 farm bill does not authorize USDA "to regulate the use of private, or non-Federal land"; rather, "the objective of this provision is to deny various Federal benefits to those producers who choose to drain wetlands for the purpose of producing agricultural commodities."4 Since the enactment of the 1985 farm bill, each succeeding farm bill has amended the compliance provisions. For a brief history of the farm bill legislative changes to the conservation compliance provisions since the 1985 farm bill, see Appendix.

Sodbuster

The highly erodible land conservation provision, as enacted in the 1985 farm bill, introduced the concept that in exchange for certain federal farm benefits a producer must implement a minimum level of conservation. The provision, still in force today, applies the loss of benefits to land classified as highly erodible that was not in cultivation between 1980 and 1985 (i.e., newly broken land, referred to as sodbuster) and any highly erodible land in production after 1990, regardless of when the land was put into production. Land meeting this classification can be considered eligible for USDA program benefits if the land user agrees to cultivate the land using an approved conservation plan.

In addition to the application of an approved conservation plan, a number of exemptions are possible.5

- Good faith. If the person has acted in good faith and without the intent to violate the compliance provisions, then the producer may be granted up to one year to comply with a conservation plan.

- land that currently has, or if put into agricultural production would have, an excessive average annual rate of erosion in relation to the soil loss tolerance level (see "The 'T'' Factor" text box, below); or

- cropland that is classified as class IV, VI, VII, or VIII land under the land capability classification system in effect on December 23, 1985.

- Graduated penalty. Under some circumstances, producers could be subject to a minimum of $500 and no more than $5,000 loss in benefits, rather than a loss of all benefits.

- Allowable variance. If a conservation system fails and the failure is determined to be technical and minor in nature, and to have little effect on the erosion control purposes of the conservation plan, then the producer may not be found out of compliance. Similarly, the producer may not be found out of compliance if the system failure was due to circumstances beyond the control of the producer.

- Temporary variance. A producer may be granted a temporary variance for practices prescribed in the conservation plan due to issues related to weather, pests, or disease. USDA has 30 days from the date of the request to issue a temporary variance determination; otherwise the variance is considered granted.

- Economic hardship. A local Farm Service Agency (FSA) county committee, with concurrence from the state or district FSA director and technical concurrence from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), is allowed to permit relief if it is determined that a conservation system causes a producer undue economic hardship.

- Federal crop insurance premium subsidies. Producers new to compliance requirements (after enactment of the 2014 farm bill on February 7, 2014) have five reinsurance years7 to develop and comply with a conservation plan. Producers with compliance violations prior to February 7, 2014, are allowed two reinsurance years to develop and comply with a conservation plan before the loss of the crop insurance premium subsidies.

|

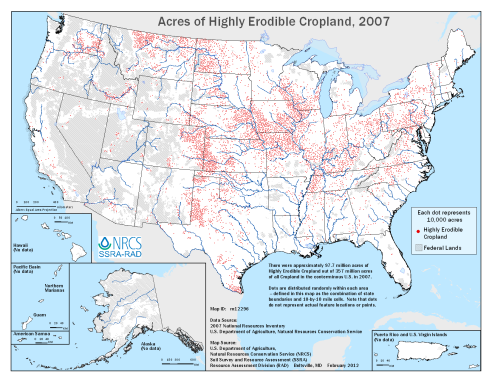

What Is "Highly Erodible"? For land to be considered highly erodible (as defined under 16 U.S.C. 3801), it must be: The land capability classification system is an interpretive grouping on soil maps made primarily for agricultural purposes. Capability "classes" are broad categories of soils with similar hazards or limitations. There are eight classes, with soil damage and limitations on use becoming progressively greater from class I to class VIII.6 NRCS classifies about 101.1 million acres of U.S. cropland—approximately 28% of total cropland—as highly erodible (see Figure 1). |

Swampbuster

The "swampbuster" or wetland conservation provision extends the sodbuster concept to wetland areas. Producers who plant a program crop on a wetland converted after December 23, 1985, or who convert wetlands, making agricultural commodity production possible, after November 28, 1990, are ineligible for certain USDA program benefits. This means that, for a producer to be found out of compliance, crop production does not actually have to occur; production only needs to be made possible through activities such as draining, dredging, filling, or leveling the wetland.

Similar to sodbuster, the 2014 farm bill amends the wetlands conservation provision to include crop insurance premium subsidies as an ineligible benefit if found to be out of compliance. The amendment treats the time of wetland conversion differently (Table 1). The amendment also extends the list of exemptions for compliance violators, allowing additional time (one or two reinsurance years) for producers to remedy or mitigate the wetland conversion before losing crop insurance premium subsidies.

|

Timing |

Violation |

Penalty |

|

Newly Converted Wetlands—wetlands converted after February 7, 2014. |

Converted wetland violation impacting five or more acres. |

Ineligible for crop insurance premium subsidies, unless exemption applies or required mitigation actions are taken. |

|

Converted wetland violation impacting less than five acres. |

Ineligible for crop insurance premium subsidies, unless the landowner pays 150% of the cost of mitigation to a wetland restoration fund or conducts the required mitigation actions. |

|

|

Prior Converted Wetlands—wetlands converted before February 7, 2014. |

Any converted wetland violation. |

Eligible for crop insurance premium subsidies. Ineligible for other USDA program benefits, unless exemption applies or required mitigation actions are taken. |

|

New Insurance Policies—wetlands converted after February 7, 2014, but before a new insurance policy or plan is made available for the first time. |

Any converted wetland violation. |

Ineligible for crop insurance premium subsidies, if prior conversions are not mitigated within two reinsurance years. |

Source: 16 U.S.C. 3821(c)(2).

Notes: Table only applies to federal crop insurance premium subsidies. All other existing wetland compliance violations were unaffected by the 2014 farm bill provision.

Under the wetlands compliance provision, the following lands are considered exempt:

- a wetland converted to cropland before enactment (December 23, 1985);

- artificially created lakes, ponds, or wetlands;

- wetlands created by irrigation delivery systems;

- wetlands on which agricultural production is naturally possible;

- wetlands that are temporarily or incidentally created as a result of adjacent development activities;

- wetlands converted to cropland before December 23, 1985, that have reverted back to a wetland as the result of a lack of drainage, lack of management, or circumstances beyond the control of the landowner;

- wetlands converted if the effect of such action is minimal; and

- authorized wetlands converted through a permit issued under Section 404 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. 1344), for which wetland values, acreage, and functions of the converted wetland were adequately mitigated.

|

Wetlands Mitigation Under wetlands conservation, compliance violators have the option of mitigating the violation through the restoration of a converted wetland, the enhancement of an existing wetland, or the creation of a new wetland.8 Debate over these wetland mitigation requirements arose during the 2014 farm bill and centered on the concern that some producers were required to mitigate wetlands with a greater than 1-to-1 acreage ratio (i.e., more than one acre of mitigated wetland is required to replace one acre of wetland lost). This is allowed by statute if "more acreage is needed to provide equivalent functions and values that will be lost as a result of the wetland conversion to be mitigated." The provisions remained unchanged in the 2014 farm bill. The conference report (H.Rept. 113-333), however, included language encouraging USDA to use a wetland mitigation ratio not to exceed 1-to-1 acreage. The 2014 farm bill also provided $10 million in mandatory funding for mitigation banking efforts. In August 2016, NRCS awarded over $7 million for agricultural wetland mitigation bank projects through the Wetland Mitigation Banking Program. NRCS received over 24 applications and funded 10 projects located in the Midwest and Northern Great Plains states. Projects were selected based on the applicants' experience with wetland mitigation banking and geographic location to potential agricultural wetland conversion.9 |

Sodsaver

The 2014 farm bill amended and expanded the "sodsaver" provision, which reduces benefits for crops planted on native sod. The provision applies only to native sod acres in Minnesota, Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Nebraska.10 If a producer chooses to plant an insurable crop on native sod, then crop insurance premium subsidies are reduced by 50 percentage points during the first four years of planting.11 Crops planted on native sod also will have higher fees under the noninsured crop disaster assistance program (NAP)12 and reduced yield guarantees.13 This provision is expected to reduce the federal incentive to produce on native sod.

Affected Program Benefits

As it exists today, conservation compliance applies to most farm program payments, loans, or other benefits administered by FSA and NRCS. Table 2 includes the statutory description and examples of specific USDA program benefits that are affected if a producer is found to be out of compliance with the highly erodible land and wetland conservation provisions.

|

Statutory Description |

Examples of Benefits |

|

Contract payments under a production flexibility contract, marketing assistance loans, and any type of price support or payment made available under the Agricultural Market Transition Act, the Commodity Credit Corporation Charter Act (15 U.S.C. 714 et seq.), or any other Act. |

Price Loss Coverage (PLC) payments, Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) payments, Margin Protection Program (MPP), and Marketing Assistance Loans |

|

A farm storage facility loan made under Section 4(h) of the Commodity Credit Corporation Charter Act (15 U.S.C. 714b(h)).a |

Farm Storage Facility Loan |

|

Disaster paymentsa |

Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance program (NAP), ad hoc disaster assistance programs, Emergency Forest Restoration Program (EFRP), Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honey Bees, and Farm-raised Fish (ELAP), Livestock Forage Program (LFP), Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP), and Tree Assistance Program (TAP) |

|

A farm credit program loan made, insured, or guaranteed under the Consolidated Farm and Rural Development Act or any other provision of law administered by FSA.b |

FSA Farm Operating Loans, Farm Ownership Loans, and Emergency Disaster Loans |

|

Any portion of the premium paid by the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation Act (7 U.S.C. 1501 et seq.) |

Federal crop insurance premium subsidiesc |

|

A payment made pursuant to a contract entered into under the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) or any other provision of Subtitle D of the Food Security Act of 1985, as amended |

Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP), Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), and Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP). |

|

A payment made under Section 401 or 402 of the Agricultural Credit Act of 1978 (16 U.S.C. 2201 or 2202). |

Emergency Conservation Program (ECP) and Emergency Watershed Protection (EWP) Program |

|

A payment, loan, or other assistance under Section 3 or 8 of the Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act (16 U.S.C. 1003 or 1006a). |

Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention program |

Source: 16 U.S.C. 3811 and 16 U.S.C. 3812.

Notes: The examples listed should not be considered an exhaustive list. Also affected would be any payments made under Section 4 or 5 of the Commodity Credit Corporation Charter Act (15 U.S.C. 714b or 714c) for the storage of an agricultural commodity acquired by the CCC.

a. Applies only to highly erodible land conservation provisions.

b. Only applies if the proceeds of the loan will be used for a purpose that contributes to the conversion of wetlands that would make production of an agricultural commodity possible or for a purpose that contributes to excessive erosion of highly erodible land. Loans made before enactment of the 1985 farm bill are not affected.

c. Does not apply retroactively. Only applies to reinsurance years following final determination and after all administrative appeals.

If a producer requests any payment, loan, or other benefit subject to the conservation compliance provision, then the provision applies to all land owned by the producer or the producer's affiliates. This includes land located anywhere in the United States or U.S. territories, without regard to whether payments, loans, or other benefits are actually received for such land. In other words, if producers are found out of compliance on one portion of their land, they are deemed out of compliance for all land owned or associated with them, regardless of where it is located.14

Implementation

Both NRCS and FSA implement conservation compliance as part of USDA farm programs. FSA has primary responsibility for making producer eligibility determinations about conservation compliance. NRCS has primary responsibility for technical determinations associated with conservation compliance.

NRCS conducts compliance status reviews on farm and ranch lands that have received USDA benefits and which are subject to the conservation compliance provisions (highly erodible land, wetland compliance, or both). A compliance status review is an inspection of a cropland tract to determine whether the USDA farm program beneficiary is in compliance with the conservation compliance provisions (Table 3). NRCS selects a random sample of tracts for annual compliance reviews from data supplied by FSA. Other tracts may be selected for review based on recommendations from other USDA agencies, whistleblower complaints, observed potential violations by NRCS, and tracts with prior year variances.15 The review process requires an NRCS employee to make an on-site determination when a violation is suspected, and ensures that only qualified NRCS employees report violations. Ultimately, penalties for noncompliance are determined by FSA. Penalties may range from a good faith exemption that allows producers up to one year to correct the violation, to a determination that the producer is ineligible for any government payment and must pay back current and prior years' benefits.

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

|

Total Tracts Reviewed |

18,704 |

22,210 |

24,309 |

23,627 |

22,127 |

|

Total Acres Reviewed (approx.) |

3.3 million |

2.8 million |

3.6 million |

3.6 million |

3.2 million |

|

Tracts Out of Compliance |

344 |

530 |

744 |

680 |

606 |

|

Wetland Conservation Violation Only |

177 |

158 |

343 |

216 |

240 |

|

Both Highly Erodible Land and Wetland Conservation Violations |

167 |

372 |

401 |

21 |

22 |

|

Percentage Out of Compliance |

1.8% |

2.4% |

3.1% |

2.9% |

2.7% |

|

Number of States Recording Non-Compliance |

28 |

32 |

30 |

34 |

38 |

|

Variances or Exemptions Issued |

732 |

887 |

1,081 |

1,354 |

1,121 |

Source: USDA, NRCS, complied by CRS.

Note: Information for 2014 is the most recent available.

The Risk Management Agency (RMA) at USDA administers the federal crop insurance program and has limited responsibilities with conservation compliance implementation. RMA and associated approved insurance providers16 are prohibited from making any eligibility determinations regarding conservation compliance.17 Implementation duties are limited to providing approved insurance agents with compliance-related records and notifying FSA and NRCS of cases of misrepresentation, fraud, or schemes and devices where appropriate.

Issues for Congress

The 1985 farm bill created the highly erodible land conservation and wetland conservation compliance provisions, which tied various farm program benefits to conservation standards. These provisions have been amended with each subsequent farm bill, including the most recent 2014 farm bill. As the 114th Congress continues to review the implementation of farm programs, issues related to conservation compliance could be debated.

Wetland Determinations

Beginning in the 2000s, weather events and expanded production in the northern plains states resulted in an increased number of wetland determination requests from producers in order to remain in compliance with wetland conservation provisions. NRCS has sole responsibility for making wetland determinations, and the growing number of requests has resulted in a backlog.

This backlog has continued to grow in recent years, reaching to over 4,000 pending wetland determinations in the Prairie Pothole region in the summer of 2015.18 As of July 2016, pending wetland determinations totaled less than 3,000. According to testimony, NRCS continues to chip away at the backlog by redirecting staff and resources to the Prairie Pothole region states with a goal of eliminating the backlog within three years.19 Budget restrictions are cited as the primary obstacle for reducing the backlog sooner.20

In November 2014, NRCS proposed changes to the offsite methods used to make wetlands determination in Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota.21 The changes allow the four Prairie Pothole states to make initial wetland determinations based on new mapping technology rather than on-site visits. A producer may request an on-site wetland determination if unsatisfied with the initial off-site determination.22 The proposal was met with opposition from a number of wildlife and conservation organizations that expressed concern that the off-site methods may not accurately account for seasonal and temporary wetlands, and that additional analysis should be conducted to ensure the determination methods are at least as accurate as the previous methods.23 In response, NRCS officials say the new process will be faster, cheaper, more accurate, and more consistent across the four states.24

2014 Farm Bill Implementation

On April 24, 2015, USDA published an interim final rule (2015 rule) amending conservation compliance regulations in accordance with changes made in the 2014 farm bill.25 The rule made three main amendments: (1) applied conservation compliance provisions to federal crop insurance premium subsidies, (2) modified easement provisions related to wetland mitigation banks, and (3) amended provisions related to agency discretion for certain violations. The level of interest and debate generated by the changes to conservation compliance in the 2014 farm bill is likely to continue as USDA proceeds with implementation.

Crop Insurance

The majority of changes made by the 2015 rule are in response to the 2014 farm bill's addition of federal crop insurance subsidies to the list of program benefits that could be lost if a producer were found to be out of compliance with conservation requirements on highly erodible land and wetlands. The changes and deadlines for compliance are correlated to the changes made in the 2014 farm bill.26 How compliance is calculated, where compliance provisions apply, and traditional exemptions and variances were not amended by the rule. Producers must continue to self-certify their compliance with the sodbuster and swampbuster provisions, and approved conservation plans currently in place will remain valid.

The first deadline following the 2014 farm bill was on June 1, 2015.27 To remain eligible for crop insurance premium subsidies, producers are required to certify their compliance with sodbuster and swampbuster provisions using a form known as an AD-1026. USDA conducted a number of outreach activities to notify producers who were enrolled in the crop insurance program but did not have a current AD-1026 compliance form on file with FSA.28 In July 2015, USDA reported a 98.2% certification rate, suggesting that those not certified were likely no longer farming or had filed forms with discrepancies that may still be reconciled.29

Wetland Mitigation Banking and Violations

Under wetlands conservation, compliance violators have the option of mitigating the violation through the restoration of a converted wetland, the enhancement of an existing wetland, or the creation of a new wetland. The 2015 rule amends regulations related to wetland mitigation banking and defining wetland conservation violations.

Wetland mitigation banking is a type of wetlands mitigation whereby a wetland is created, enhanced, or restored, and "credit" for those efforts is sold to others as compensation for the loss of impacted wetlands elsewhere. While wetland mitigation banks are not new, challenges related to access and cost have prevented agricultural producers from utilizing this option for mitigation. The 2014 farm bill changes the wetland mitigation banking provision to allow for third parties to hold wetland mitigation easements, rather than USDA itself. The 2014 farm bill also created a permanent wetland mitigation banking program and provided $10 million in mandatory funding (discussed above).

Other changes in the 2015 rule were not directed by the 2014 farm bill, including a clarification regarding wetland conservation violations. According to the rule, there are two types of wetland conservation violations with two different consequences. The first type is violations for production on converted wetland, which can result in a graduated penalty determined by USDA, rather than a denial of all benefits.30 The second type is a conversion of wetland to production, which can result in a denial of all benefits.31 According to USDA, previous language was used by producers who converted a wetland to argue that USDA has discretion to issue a graduated penalty similar to that of production on converted wetlands rather than a full denial of benefits. It is unclear what level of confusion existed prior to this change and what impact, if any, this clarification will have on determining wetland compliance violations and associated appeals in the future.

Oversight

In 2015 and 2016, the USDA's Office of the Inspector General (OIG) evaluated the process NRCS and FSA used to identify and monitor conservation compliance provisions.32 In a series of audit reports, OIG found a number of weaknesses with NRCS's internal controls. The final OIG report notes that NRCS state offices have developed inadequate guidance for consistently applying standards in conducting compliance reviews. Of particular concern is the treatment and control of gully erosion,33 which the report highlights as being inconsistently applied across states, therefore leading to inconsistent noncompliance determinations. The report also found that NRCS guidance on the role of a wetland compliance reviewer needed updating to reflect the review's role when wetland inventory maps are found to be inaccurate. This lack of guidance has led to inconsistencies across states.

|

The "T" Factor Soil erosion occurs for a variety of natural and manmade reasons. An evaluation of different soil types and surrounding conditions (e.g., soil depth, slope, etc.) allows soil scientists to determine what an "acceptable" rate of soil erosion is for a given area. This is commonly referred to as "T" or soil loss tolerance rate. T is the maximum rate of annual soil loss that will permit crop productivity to be sustained economically and indefinitely on a given soil. Erosion is considered to be greater than T if either the water (sheet and rill) erosion or the wind erosion rate exceeds the soil loss tolerance rate. The higher the T value, the more soil erosion can be tolerated. The use of T is one of the bases for identifying highly erodible land associated with conservation compliance. The erodibility index for a soil is determined by dividing the potential average annual rate of erosion for each soil by its predetermined soil loss tolerance (T) value. T is also used as one of the criteria for planning soil conservation systems required by conservation compliance. Conservationists focus on reducing soil loss to or below T by applying practices, such as terraces, contour strips, grassed waterways, and residue management. The use of T has been and will likely remain controversial. Some soil scientists have suggested that the current values of T far exceed the actual soil formation rates and therefore are not truly "sustainable" (Craig Cox, Andrew Hug, and Nils Bruzelius, Losing Ground, Environmental Working Group, April 2011). Despite these concerns, T remains the only commonly used standard by which soil erosion is measured. |

Annually, NRCS selects a random sample of tracts for annual compliance reviews from data supplied by FSA. As part of their investigation, OIG determined that NRCS did not use a comprehensive set of eligible tracts in 2015, because it included only producers participating in one program. Also, FSA had inadvertently omitted 10 states that historically make up about 34% of eligible tracts.34 Overall, NRCS and FSA concurred with the OIG findings and recommendations. However, stakeholders' views continue to vary on how well USDA is enforcing the conservation compliance provisions. For instance, environmental organizations advocate for more consistent and rigorous status reviews. Producer organizations advocate for continued flexibility and more additional voluntary programs incentives to support any necessary improvements.

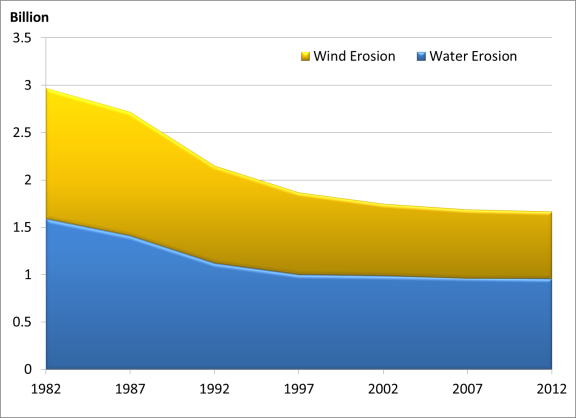

Erosion and Conversion Rates

The reduction in soil erosion from highly erodible land conservation continues, but at a slower pace than following enactment of the 1985 farm bill (Figure 2). The leveling off of reduced erosion leaves several broad policy questions, including whether an acceptable level of soil erosion on cropland has been achieved; whether additional reductions could be achieved, and if so, at what cost; and how federal farm policy should encourage additional reductions in erosion. Some environmental and conservation groups have asked Congress to tighten compliance requirements as one way of reducing soil erosion. Many agricultural groups, however, prefer additional financial incentives through voluntary conservation programs, such as EQIP.

According to USDA's Natural Resource Inventory, in 2012, 101 million acres (28% of all cropland) was eroding above soil loss tolerance (T) rates (see text box).35 This compares to 175 million acres (42% of cropland) in 1982. Between 1982 and 2012, farmers reduced total cropland soil erosion by 44% (Figure 2). The bulk of this reduction occurred following the 1985 farm bill and the implementation of CRP and conservation compliance requirements. Reduction in soil erosion may also be attributed to other factors. Estimates indicate that compliance provisions could be responsible for approximately 295 million tons, or 25% of the 1.2 billion ton reduction in cropland soil erosion that occurred between 1982 and 1997 (most recent information available).36 Another 31%, or 365 million tons, reduced could be attributed to land use changes, including CRP enrollment.37

|

Figure 2. Soil Erosion on Cropland by Year (billions of tons) |

|

|

Source: USDA, NRCS, Summary Report: 2012 National Resources Inventory, August 2015, http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcseprd396218.pdf. Notes: Total includes cultivated and non-cultivated cropland. Water erosion includes sheet and rill erosion. |

In addition to soil erosion reductions following the 1985 farm bill, the number of wetlands converted to cropland was also reduced. Unlike the highly erodible land conservation provision, the impact of the wetland conservation provision is increasingly difficult to measure.

Swampbuster is one of several federal, state, and local policies that discourage the conversion of wetlands to other uses.38 Other farm bill programs, such as Wetland Reserve Easements in the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) and CRP, seek to provide a reverse effect and encourage landowners to restore wetlands. Between 1997 and 2007, USDA estimates that the United States experienced a net wetlands gain of about 250,000 acres.39 Sixty percent of the gross loss (440,000 acres) during that time period is attributed to urban and industrial development and 15% is attributed to agriculture.

Conclusion

Since its introduction in the 1985 farm bill, conservation compliance has remained a controversial issue. Most producers prefer voluntary financial incentive programs such as EQIP, to policies such as conservation compliance, which discourages the degradation of private lands by restricting access to other federal benefits. With continued fiscal challenges, increasing or maintaining funding levels for financial incentive programs could be difficult. Conservation compliance, on the other hand, does not increase federal spending but continues to be unpopular among many producer groups. The compliance requirements have also made significant contributions to reducing soil erosion and maintaining wetlands since the 1980s. These environmental gains appear to be leveling off, however, and raise questions about conservation compliance's ability to further conservation goals. Similar to previous farm bills, the changes to conservation compliance in the 2014 farm bill debate were controversial. As Congress evaluates the implementation of the 2014 farm bill, conservation compliance might continue to generate interest.

Appendix. A Brief Legislative History of Conservation Compliance

Prior to the 1985 farm bill, approximately two dozen soil and water conservation programs existed. These programs reflected a pattern that was established in the 1930s—voluntary cooperation from land users and incentive-based programs—and changed little in 50 years. The expansion of agricultural production in the 1970s to respond to growing world demand for farm products was accompanied by an increase in soil erosion.40 Much of this erosion was attributed to producers expanding their acreage into "marginal" land—land that easily erodes and is often less productive. Intense production practices were supported by many of the federal farm policies in place at the time.

In 1977, Congress enacted the Soil and Water Resources Conservation Act (P.L. 95-192, referred to as the RCA). The RCA required USDA to appraise the nation's natural resources on nonfederal land and provide Congress with an annual evaluation report. Many of the soil and water resource issues were highlighted in the 1980 RCA report and drew attention to the high societal cost of soil erosion and wetland conservation that resulted from intense production.41 As part of the National Program for Soil and Water Conservation, USDA presented the alternative of "cross-compliance," in which farmers who receive USDA benefits would be required to meet minimum conservation standards.42

In the early 1980s, large-scale commodity surpluses of certain agricultural products developed from weak global demand and advances in agricultural productivity. In response, during the 1985 farm bill debate, Congress sought new farm policies to increase export markets and reduce domestic production, thereby reducing surpluses. The result was what some classified as a radical departure from the traditional conservation approach.

1985 Farm Bill

The Food Security Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-198, 1985 farm bill) included a number of significant conservation provisions designed to reduce production and conserve soil and water resources. The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), as authorized in the 1985 farm bill, was allowed to remove up to 45 million acres of land from production under multi-year rental agreements. The financial incentives of CRP far exceeded those of most early conservation programs, and CRP remains the largest conservation program (in terms of funding) to date.43 The other conservation provisions were highly erodible land conservation (sodbuster) and wetland conservation (swampbuster). Despite the historic significance of these provisions there was surprisingly little debate recorded at the time.

Sodbuster

The highly erodible land conservation provision, as enacted in the 1985 farm bill, introduced the requirement that in exchange for certain federal farm benefits a producer must implement a minimum level of conservation. The provision applies the loss of benefits to land classified as highly erodible that was not in cultivation between 1980 and 1985 (i.e., newly broken land, referred to as sodbuster) and any highly erodible land in production after 1990, regardless of when the land was put into production. Land meeting this classification could be considered eligible for USDA program benefits if the land user agreed to cultivate the land using an approved conservation plan.

There were two main exceptions. First, the farmer had until January 1, 1990, or two years after the completion of a soil survey—whichever was later—to be actively applying an approved conservation plan. Second, if a farmer was actively applying an approved conservation plan, then they had until January 1, 1995, to be full in compliance with the plan. The program benefits that could be lost included

- price supports and related payments,

- farm storage facility loans,

- crop insurance,

- disaster payments,

- any farm loans that will contribute to excessive erosion of highly erodible land, and

- storage payments made to producers for crops acquired by the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC).

Swampbuster

The "swampbuster" or wetland conservation provision extends the sodbuster requirement to wetland areas. Producers who plant a program crop on a converted wetland would be ineligible for certain USDA program benefits. The most controversial debate over the swampbuster provision was on the definition of an affected wetland areas. This resulted in many wetland areas being exempt, including

- wetlands converted before enactment (December 23, 1985),

- artificially created lakes, ponds, or wetlands,

- wetlands created by irrigation delivery systems,

- wetlands on which agricultural production is naturally possible, or

- wetlands converted if the effect of such action is minimal.

Changes Since the 1985 Farm Bill

Since the enactment of the 1985 farm bill, each succeeding farm bill has amended the compliance provisions (both highly erodible land and wetland conservation).

1990 Farm Bill

The compliance provisions were amended in several ways in the Food, Agriculture, Conservation, and Trade Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-624, 1990 farm bill). Conservation provisions were expanded to include wetlands converted after enactment (November 28, 1990), where agricultural commodity production was made possible. This meant that crop production did not actually have to occur in order to be found out of compliance, only that production was made possible through activities such as draining, dredging, filling, or leveling the wetland. The 1990 farm bill added six more federal farm programs to the list of benefits that could be lost for non-compliance, including many of the conservation programs. A graduated penalty was added so that under some circumstances, producers could be subject to a loss in benefits of between $500 and $5,000. This graduated penalty may be applied only once every five years. The revisions protect tenant farmers who may be ruled out of compliance because of the actions of the landowner or previous tenants. Compliance exemptions were also expanded to include highly erodible land set aside, or taken out of production, under the commodity support programs.

1996 Farm Bill

Beginning in 1994, conservation policy discussions in Congress focused on identifying ways to make the compliance programs less intrusive on farmer activities. As a result, conservation compliance provisions were significantly amended in the Federal Agricultural Improvement and Reform Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-127, referred to as the 1996 farm bill). Many of the conservation compliance changes enacted in the 1996 farm bill were meant to provide producer flexibility and reduce the impact on farm operations. Some of the major amendments to highly erodible land conservation compliance in the 1996 farm bill include

- removing crop insurance from the list of benefits that could be lost if the farmer is found out of compliance;

- adding production flexibility contracts44 to the list of benefits that could be lost if found out of compliance;

- highly erodible land exiting CRP would not be held to a higher compliance standard than nearby cropland;

- providing violators with up to one year to meet compliance requirements;

- developing procedures to expedite variances for weather, pest, or disease problems;

- requiring an erosion measurement before the conservation system is implemented;

- allowing third parties to measure residue and require that residue measurements take into account the top two inches of soil;

- allowing producers to modify plans as long as the same level of treatment is maintained;

- allowing local county committees to permit relief if a conservation system causes a producer undue economic hardship; and

- establishing a wind erosion estimation pilot study to review and modify as necessary wind erosion factors used to administer conservation compliance.

Several changes were made in the 1996 farm bill to the wetland conservation provisions as well. Similar to the provisions for highly erodible land, wetland conservation provisions were meant to provide greater program flexibility. Major changes included

- exempting swampbuster penalties when wetland values and functions are voluntarily restored following a specified procedure;

- providing that prior converted wetlands will not be considered "abandoned" as long as the land is only used for agriculture;

- giving the Secretary of Agriculture discretion to determine which program benefits violators are ineligible for and to provide good-faith exemptions;

- establishing a pilot mitigation banking program (using the CRP);

- repealing required consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; and

- expanding the definition of agricultural lands used in a 1994 interagency Memorandum of Agreement.

While the 1996 farm bill reduced the impact of the compliance requirements it also expanded the voluntary incentive-based programs for agricultural conservation. For the first time the majority of conservation funding was authorized as mandatory funding.45 Total funding levels for conservation were increased. The conservation agenda was also broadened by adding wildlife considerations and evaluating nonpoint source pollution from agricultural sources.

2002 Farm Bill

The Food Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-171, 2002 farm bill) continued and expanded many of the conservation priorities in the 1996 farm bill, especially those related to voluntary incentive programs and increased funding. Few changes were made to the conservation compliance provisions. The primary change was the requirement that USDA not delegate authority to other parties to make highly erodible land determinations. Also, any person who had highly erodible land enrolled in the CRP was given two years after a contract expires to be in full compliance.

2008 Farm Bill

The Food, Conservation and Energy Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-246, referred to as the 2008 farm bill) again made few changes to the conservation compliance provisions. The primary change was the addition of a second level of review by the state or district FSA director, with technical concurrence from the state or area NRCS conservationist if USDA determines that this exception should apply.

The 2008 farm bill also created the "sodsaver" provision under the crop insurance title (XII). The sodsaver provision would have made producers who planted crops (five or more acres) on native sod ineligible for crop insurance and the noninsured crop disaster assistance (NAP) program for the first five years of planting. The 2008 farm bill limited the provision to virgin prairie converted to cropland in the Prairie Pothole National Priority Area, but only if elected by the state. States included in the Prairie Pothole National Priority Area are portions of Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Iowa. Ultimately no governors opted to participate in the program and sodsaver was never activated.

2014 Farm Bill

When the farm bill debate began in 2012, the fiscal climate made reductions in the farm bill baseline all but certain. One of the largest programs on the chopping block was direct payments in the commodity title. Because conservation compliance is tied to farm program benefits the loss of such a large benefit would ultimately reduce the incentive to comply with conservation requirements. Conservation advocates cited the need for additional farm program benefits to be tied to conservation compliance in exchange for the loss of direct payments. Ultimately the Agricultural Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-79, 2014 farm bill) added the federally funded portion of crop insurance premiums to the list of benefits that could possibly be lost if a producer were found out of compliance. The amendments, however, treat compliance violations and the loss of federal crop insurance premium subsidies separate from the loss of other farm program benefits.

Additionally, the 2014 farm bill amended the sodsaver provision by removing the elective option, reducing crop insurance subsidies rather than eliminating them, and expanding the provision to six states. For a more detailed comparison of changes made by the 2014 farm bill, see CRS Report R43504, Conservation Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79).

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

CRP is not discussed in depth in this report. For additional information and issues related to CRP, see CRS Report R40763, Agricultural Conservation: A Guide to Programs. |

| 2. |

Highly erodible land conservation and wetland conservation are collectively referred to as conservation compliance in this report. |

| 3. |

H.Rept. 99-271, p. 84. |

| 4. |

Ibid., p. 88. |

| 5. |

In addition to those listed, a producer who participated in a USDA program that set aside land for the purpose of reducing production of an agricultural commodity, may also not be considered ineligible. Many of these "set-aside" programs are no longer utilized. |

| 6. |

USDA, Soil Conservation Service, Land Capability Classifications System, Agricultural Handbook 210, 1961, http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_052290.pdf. |

| 7. |

A reinsurance year is a 12-month period that begins on July 1. |

| 8. |

16 U.S.C. 3822(f). |

| 9. |

For additional information on the Wetland Mitigation Banking Program, see http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/programs/farmbill/?cid=NRCSEPRD362686. |

| 10. |

Section 11014 of the crop insurance title (title XI). Sodsaver was originally authorized in the 2008 farm bill and only applied to the Prairie Pothole National Priority Area. The provision was never activated and is discussed further in Appendix. |

| 11. |

In 2016, an average of 63% of the total crop insurance premium is paid for by the federal government, and the remainder by the participating farmer. Therefore, a 50 percentage point reduction would lower a premium subsidy rate of 63% to 13%. |

| 12. |

For additional information on crop insurance and NAP, see CRS Report R40532, Federal Crop Insurance: Background; CRS Report RS21212, Agricultural Disaster Assistance; or CRS Report R43494, Crop Insurance Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79). |

| 13. |

The yield guarantee for a crop insurance policy is a producer's "normal" crop yield based on actual production history (APH). In the absence of actual yield data (e.g., production on native sod or no yield documentation on existing fields), a "transition yield" (T-yield) is assigned, which is based on a portion of 10-year average county yields for the crop. The 2014 farm bill sets the T-yield factor on native sod equal to 65% of the 10-year average county yield for production on native sod. For other cropland, the percentage can be higher depending on the number of years of actual data included in the APH. Also, "yield substitution" is not allowed; that is, low farm yields must be used in the APH rather than replacing them with potentially higher T-yields as allowed for other cropland. |

| 14. |

One exception to this was created in the 2014 farm bill. If a tenant is considered ineligible for benefits under conservation compliance and USDA determines that the tenant has made a good faith effort to comply with restoration or mitigation requirements and the landowner continues to refuse to comply, then the denial of benefits may be limited to the farm that is the basis of the ineligibility. The 2015 rule clarified that because federal crop insurance policies are not constructed on a "farm" basis, tenant relief provisions will be achieved through a prorated reduction of premium subsidies on all of a person's policies and plans of insurance. Similarly, a landlord's premium subsidy on all policies and plans of insurance will be prorated in the same manner when a landlord is in violation because of the actions (or inactions) of their tenant or sharecropper (7 C.F.R. 12.9). |

| 15. |

Additionally, compliance reviews are required at least once every three years on tracts owned or operated by USDA employees who receive USDA payments. National Food Security Act Manual, 5th edition, Part 518, Subpart A, §518.1 (A)(1)(viii), November 2010. |

| 16. |

Insurance policies for the federal crop insurance program are sold and completely serviced through 18 approved private insurance companies known as approved insurance providers. For additional information on how federal crop insurances is administered, see CRS Report R40532, Federal Crop Insurance: Background. |

| 17. |

16 U.S.C. 3821(c)(4)(C). |

| 18. |

Prairie potholes are depressional wetlands that fill with snowmelt and rain in the spring. Some of these wetlands are temporary, and some are permanent. Most of the prairie potholes are located in portions of Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Iowa and make up the Prairie Pothole National Priority Area. The northern plains location of these wetlands is ideal habitat for migratory waterfowl and provides natural flood control for snow melt and spring rains. |

| 19. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry, Farmers and Fresh Water: Voluntary Conservation to Protect Our Land and Waters, testimony of Jason Weller, Chief of the NRCS, 113th Cong., 2nd sess., December 3, 2014. |

| 20. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry, The Agricultural Act of 2014 Implementation After One Year, testimony of Tom Vilsack, Secretary of USDA, 114th Cong., 1st sess., February 24, 2015. |

| 21. |

USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service, "Notice of Proposed Changes to Section I of the Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota State Technical Guides," 79 Federal Register 65615, November 5, 2014. The proposal was not a rulemaking action, and therefore no final proposal was issued. Public comments were addressed on NRCS's website: http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/PA_NRCSConsumption/download?cid=nrcseprd399229&ext=pdf. |

| 22. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Agriculture, Subcommittee on Conservation and Forestry, Implementing the Agricultural Act of 2014: Conservation Programs, 114th Cong., 1st sess., June 11, 2015, H.Hrg. 114-17, p. 55. |

| 23. |

Letter from 29-90 Sportsmen's Club, Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, and Friends of the Big Sioux, et al. to Jason Weller, Chief of the Natural Resources Conservation Service, February 3, 2015, http://www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=NRCS-2014-0013-0084. |

| 24. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies, Budget Hearing—Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment, testimony of Chief Jason Weller, 114th Cong., 2nd sess., February 26, 2016. |

| 25. |

USDA Office of the Secretary, "Conservation Compliance," 80 Federal Register 22873-22885, April 24, 2015. |

| 26. |

For additional information, see CRS Report R43504, Conservation Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79). |

| 27. |

USDA, Federal Crop Insurance Corporation, "General Administrative Regulations; Catastrophic Risk Protection Endorsement; Area Risk Protection Insurance Regulations; and the Common Crop Insurance Regulations, Basic Provisions," 79 Federal Register 37155-37166, July 1, 2014. |

| 28. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Agriculture, Subcommittee on General Farm Commodities and Risk Management, Farm Bill, Implementing the Agricultural Act of 2014: Commodity Policy and Crop Insurance, 114th Cong., 1st sess., March 26, 2015. |

| 29. |

USDA, "Record Number of Farmers and Ranchers Certified Under 2014 Farm Bill Conservation Compliance," press release, July 10, 2015, http://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USDAOC/bulletins/10e8a2c. |

| 30. |

16 U.S.C. 3821(a)(2). |

| 31. |

16 U.S.C. 3821(d). |

| 32. |

USDA, Office of Inspector General, USDA Monitoring of Highly Erodible Land and Wetland Conservation Violations, Audit Report 50601-0005-31, June 2016, https://www.usda.gov/oig/webdocs/50601-0005-31.pdf. |

| 33. |

Gully erosion is a process whereby water concentrates in narrow channels and removes the soil through narrow areas to varying depths. There are two types of gully erosion: ephemeral and classic. |

| 34. |

USDA, Office of Inspector General, USDA Monitoring of Highly Erodible Land and Wetland Conservation Violations (Interim Report), Audit Report 50601-0005-31, March 2016. |

| 35. |

USDA, NRCS, Summary Report: 2012 National Resources Inventory, August 2015, http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcseprd396218.pdf. |

| 36. |

Roger Claassen, "Have Conservation Compliance Incentives Reduced Soil Erosion?" USDA, ERS, Amber Waves, June 2004, http://www.ers.usda.gov/AmberWaves/June04/Features/HaveConservation.htm. |

| 37. |

Ibid. The 2014 farm bill reduced the acreage enrollment in CRP from an authorized level of 32 million acres declining to 24 million by FY2018. This could have a potential impact on soil erosion, the magnitude of which is unclear. |

| 38. |

The other major federal policy is Section 404 of the Clean Water Act. For additional information, see CRS Report RL33483, Wetlands: An Overview of Issues. |

| 39. |

USDA, RCA Appraisal: Soil and Water Resources Conservation Act, Washington, DC, July 2011, http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb1044939.pdf. |

| 40. |

J. Douglas Helms, Leveraging Farm Policy for Conservation: Passage of the 1985 Farm Bill, USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Historical Insights Number 6, June 2006, http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb1044129.pdf. |

| 41. |

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Summary of Appraisal, Parts I and II, and Program Report, GPO 1980 633-769/460, 1980. |

| 42. |

U.S. Department of Agriculture, A National Program for Soil and Water Conservation, 1982 Final Program Report and Environmental Impact Statement, GPO 1982-0-522-010/3711, September 1982. |

| 43. |

CRP is currently authorized to enroll up to 32 million acres and annually spends an average of over $2 billion in mandatory funding. The purpose of CRP has long been debated. In its early years, some believed the program's sole purpose was for production control. Others saw CRP as a soil erosion control program. Today, many view it as a wildlife habitat program. The program's objectives and purpose are not debated in this report. For additional information and issues related to CRP reauthotization, see CRS Report R42093, Agricultural Conservation and the Next Farm Bill. |

| 44. |

Producer flexibility contracts are now referred to as direct payments. |

| 45. |

Mandatory funding is made available by multiyear authorizing legislation and does not require annual appropriations or subsequent action by Congress. |