Super PACs in Federal Elections: Overview and Issues for Congress

Super PACs emerged after the U.S. Supreme Court permitted unlimited corporate and union spending on elections in January 2010 (Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission). Although not directly addressed in that case, related, subsequent litigation (SpeechNow v. Federal Election Commission) and Federal Election Commission (FEC) activity gave rise to a new form of political committee. These entities, known as super PACs or independent-expenditure-only committees (IEOCs), may accept unlimited contributions and make unlimited expenditures aimed at electing or defeating federal candidates. Super PACs may not contribute funds directly to federal candidates or parties. Super PACs must report their donors to the FEC, although the original source of contributed funds—for super PACs and other entities—is not necessarily disclosed.

This report provides an overview of policy issues surrounding super PAC activity in federal elections. Congress has not amended the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) to recognize formally the role of super PACs. The FEC issued rules in 2014 to reflect their presence. The most substantial policy guidance about super PACs occurred through advisory opinions that the agency issued in 2010 and 2011 after the Citizens United and SpeechNow decisions.

Various issues related to super PACs may be relevant as Congress considers how or whether to pursue legislation or oversight on the topic. These include relationships with other political committees and organizations, transparency, and independence from campaigns. Throughout the post-Citizens United period, relatively few bills have been devoted specifically to super PACs, although some bills would address aspects of super PAC disclosure requirements or coordination with campaigns or other groups. As of this writing, relevant legislation in the 114th Congress includes H.R. 424, H.R. 425, H.R. 430, H.R. 5494, S. 6, S. 229, S. 1838, and S. 3250.

Since their inception during the 2010 election cycle, super PACs have raised and spent more than $2 billion. Although the number of these groups has increased rapidly, only a few groups typically dominate most super PAC spending. Super PACs can emerge and disappear intermittently; groups that are active one election cycle may be diminished or absent in the next. In some cases, super PACs have formed to support single candidates and have featured few donors.

For those advocating their use, super PACs represent freedom for individuals, corporations, and unions to contribute as much as they wish for independent expenditures that advocate election or defeat of federal candidates. Opponents of super PACs contend that they represent a threat to the spirit of modern limits on campaign contributions designed to minimize potential corruption.

This report will be updated periodically to reflect major policy developments.

Super PACs in Federal Elections: Overview and Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- What Are Super PACs?

- Why Might Super PACs Matter to Congress?

- How Have Super PACs Been Regulated?

- What Information Must Super PACs Disclose?

- Overall, How Much Money Have Super PACs Raised and Spent?

- What Major Super PAC Legislative or Oversight Issues Might be Relevant for Congress?

- Conclusion

Figures

- Figure 1. Super PAC Receipts, Disbursements, and Independent Expenditures 2010-2014

- Figure 2. Super PACs Reporting Financial Activity, 2010-2014

- Figure 3. Super PAC Independent Expenditures Compared with Other Independent Expenditures, 2010-2014

- Figure 4. Sample Disclosure with Direct Spending Versus Contributions to Other Entities

Tables

- Table 1. Basic Structure of Super PACs versus Other Political Committees and Organizations

- Table 2. Super PAC Receipts, Disbursements, and Independent Expenditures 2010-2014

- Table 3. The 10 Super PACs Reporting the Most Receipts and Disbursements for the 2014 Election Cycle

- Table 4. 114th Congress Legislation Substantially Related to Super PACs

Summary

Super PACs emerged after the U.S. Supreme Court permitted unlimited corporate and union spending on elections in January 2010 (Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission). Although not directly addressed in that case, related, subsequent litigation (SpeechNow v. Federal Election Commission) and Federal Election Commission (FEC) activity gave rise to a new form of political committee. These entities, known as super PACs or independent-expenditure-only committees (IEOCs), may accept unlimited contributions and make unlimited expenditures aimed at electing or defeating federal candidates. Super PACs may not contribute funds directly to federal candidates or parties. Super PACs must report their donors to the FEC, although the original source of contributed funds—for super PACs and other entities—is not necessarily disclosed.

This report provides an overview of policy issues surrounding super PAC activity in federal elections. Congress has not amended the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) to recognize formally the role of super PACs. The FEC issued rules in 2014 to reflect their presence. The most substantial policy guidance about super PACs occurred through advisory opinions that the agency issued in 2010 and 2011 after the Citizens United and SpeechNow decisions.

Various issues related to super PACs may be relevant as Congress considers how or whether to pursue legislation or oversight on the topic. These include relationships with other political committees and organizations, transparency, and independence from campaigns. Throughout the post-Citizens United period, relatively few bills have been devoted specifically to super PACs, although some bills would address aspects of super PAC disclosure requirements or coordination with campaigns or other groups. As of this writing, relevant legislation in the 114th Congress includes H.R. 424, H.R. 425, H.R. 430, H.R. 5494, S. 6, S. 229, S. 1838, and S. 3250.

Since their inception during the 2010 election cycle, super PACs have raised and spent more than $2 billion. Although the number of these groups has increased rapidly, only a few groups typically dominate most super PAC spending. Super PACs can emerge and disappear intermittently; groups that are active one election cycle may be diminished or absent in the next. In some cases, super PACs have formed to support single candidates and have featured few donors.

For those advocating their use, super PACs represent freedom for individuals, corporations, and unions to contribute as much as they wish for independent expenditures that advocate election or defeat of federal candidates. Opponents of super PACs contend that they represent a threat to the spirit of modern limits on campaign contributions designed to minimize potential corruption.

This report will be updated periodically to reflect major policy developments.

Introduction

The development of super PACs is one of the most recent components of the debate over money and speech in elections. Some perceive super PACs as a positive consequence of deregulatory court decisions in Citizens United and related case SpeechNow. For those who support super PACs, these relatively new political committees provide an important outlet for independent calls for election or defeat of federal candidates. Others contend that they are the latest outlet for unlimited money in politics that, while legally independent, are functional extensions of one or more campaigns. This report does not attempt to settle that debate, but it does provide context for understanding what super PACs are and how they are relevant for federal campaign finance policy. The report does so through a question-and-answer format that emphasizes recurring public policy questions about super PACs.1

Now that super PACs have become established players in American elections, this updated report focuses on the background and policy matters that appear to be most relevant for legislative and oversight concerns.2 The report discusses selected litigation to demonstrate how those events have changed the campaign finance landscape and affected the policy issues that may confront Congress; it is not, however, a constitutional or legal analysis.

Finally, a note on terminology may be useful. The term independent expenditures (IEs) appears throughout the report. IEs refer to purchases, often for political advertising, that explicitly call for election or defeat of a clearly identified federal candidate (e.g., "vote for Smith," "vote against Jones"). Campaign finance lexicon typically refers to making IEs, which is synonymous with the act of spending funds for the purchase calling for election or defeat of a federal candidate. Parties, traditional PACs, individuals, and now, super PACs, may make IEs. IEs are not considered campaign contributions and cannot be coordinated with the referenced candidate.3

What Are Super PACs?

Brief Answer

Super PACs first emerged in 2010 following two major court rulings. As a result of the rulings, in Citizens United and SpeechNow, new kinds of PACs emerged that were devoted solely to making independent expenditures.4 These groups are popularly known as super PACs; they are also known as independent-expenditure-only committees (IEOCs). Independent expenditures (IEs) are frequently used to purchase political advertising or fund related services (such as voter-canvassing). IEs include explicit calls for election or defeat of federal candidates but are not considered campaign contributions.

IEs must be made independent of parties and candidates. In campaign finance parlance, this means IEs cannot be coordinated with candidates or parties. Determining whether an expenditure is coordinated can be highly complex and depends on individual circumstances.5 In essence, however, barring those making IEs from coordinating with candidates means that the entity making the IE and the affected candidate may not communicate about certain strategic information or timing surrounding the IE. The goal here is to ensure that an IE is truly independent and does not provide a method for circumventing contribution limits simply because an entity other than the campaign is paying for an item or providing a service that could benefit the campaign.

Table 1 below provides an overview of how super PACs compare with other political committees and politically active organizations. In brief, super PACs are both similar to and different from traditional PACs. Super PACs have the same reporting requirements as traditional PACs, and both entities are regulated primarily by the federal election law and the FEC as political committees. Unlike traditional PACs, super PACs cannot make contributions to candidate campaigns. Super PACs' abilities to accept unlimited contributions make them similar to organizations known as 527s and some 501(c) organizations that often engage in political activity.6 However, while those groups are governed primarily by the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), super PACs are regulated primarily by the FEC. Unlike 527s as they are commonly described, super PACs are primarily regulated by the federal election law and regulation.

Table 1. Basic Structure of Super PACs versus Other Political Committees and Organizations

(Refers to federal elections only)

|

Is the entity typically considered a political committee by the FEC? |

Must certain contributors be disclosed to the FEC? |

Can the entity make contributions to federal candidates? |

Are there limits on the amount the entity can contribute to federal candidates? |

Can federal candidates raise funds the entity plans to contribute in federal elections? |

Are there limits on contributions the entity may receive for use in federal elections? |

|

|

Super PACs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Not permitted to make federal contributions |

Yes, within FECA limits |

No |

|

"Traditional" PACsa |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

$5,000 per candidate, per election |

Yes, within FECA limits |

$5,000 annually from individuals; other limits established in FECAb |

|

National Party Committees |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

$5,000 per candidate, per election |

Yes, within FECA limits |

$33,400 per year (for 2016 cycle) from individuals; other limits established in FECA; Additional $100,200 limit for each special party account |

|

Candidate Committees |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

$2,000 per candidate, per election |

Yes, within FECA limits |

$2,700 per candidate, per election from individuals (2016 cycle); other limits established in FECA |

|

527sc |

No |

No, unless independent expenditures or electioneering communicationsd |

No |

Not permitted to make federal contributions |

N/A |

No |

|

501(c)(4)s, (5)s, (6)se |

No |

No, unless independent expenditures or electioneering communicationsf |

No |

Not permitted to make federal contributions |

N/A |

No |

Source: CRS adaptation from Table 1 in CRS Report R41542, The State of Campaign Finance Policy: Recent Developments and Issues for Congress, by R. Sam Garrett; and Federal Election Commission, "Contribution Limits for 2015-2016 Federal Elections," http://www.fec.gov/ans/answers_general.shtml#How_much_can_I_contribute.

Notes: National party committees may accept individual contributions up to the $100,200 amount shown in the table for separate accounts for (1) presidential nominating conventions (headquarters committees [e.g., DNC; RNC] only); (2) recounts and other legal compliance activities; and (3) party buildings. For additional discussion, see CRS Report R43825, Increased Campaign Contribution Limits in the FY2015 Omnibus Appropriations Law: Frequently Asked Questions, by R. Sam Garrett.

a. This report uses the term traditional PACs to refer to PACs that are not super PACs. Here, the term includes separate segregated funds, nonconnected committees, and leadership PACs. The table assumes these PACs would be multicandidate committees. Multicandidate committees are those that have been registered with the FEC (or, for Senate committees, the Secretary of the Senate) for at least six months; have received federal contributions from more than 50 people; and (except for state parties) have made contributions to at least five federal candidates. See 11 C.F.R. §100.5(e)(3). In practice, most PACs attain multicandidate status automatically over time.

b. As noted later in this report, nonconnected PACs utilizing an exemption per the Carey case may raise unlimited amounts for independent expenditures if those amounts are kept in a separate bank account and not used for contributions.

c. As the term is commonly used, 527 refers to groups registered with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) as Section 527 political organizations that seemingly intend to influence federal elections in ways that place them outside the FECA definition of a political committee. By contrast, political committees (which include candidate committees, party committees, and political action committees) are regulated by the FEC and federal election law. There is a debate regarding which 527s are required to register with the FEC as political committees. FEC contributor disclosure for these organizations applies only to those who designate their contributions for use in independent expenditures or electioneering communications. This table does not address general reporting obligations established in tax law or IRS regulations. For additional discussion, see CRS Report RS22895, 527 Groups and Campaign Activity: Analysis Under Campaign Finance and Tax Laws, by L. Paige Whitaker and Erika K. Lunder.

d. Federal tax law requires that 527s periodically disclose to the IRS information about donors who have given at least $200 during the year. See 26 U.S.C. §527(j). This information is publicly available. See 26 U.S.C. §6104.

e. For additional discussion of these groups, see CRS Report RL33377, Tax-Exempt Organizations: Political Activity Restrictions and Disclosure Requirements, by Erika K. Lunder; and CRS Report R40183, 501(c)(4)s and Campaign Activity: Analysis Under Tax and Campaign Finance Laws, by Erika K. Lunder and L. Paige Whitaker.

f. Federal tax law requires that these groups disclose information to the IRS about donors who have given at least $5,000 annually. See 26 U.S.C. §6033. Unlike information on donors to political committees and 527s, however, this information is confidential and not made public. See 26 U.S.C. §6104.

Discussion

Super PACs originated from a combination of legal and regulatory developments. The 2010 Citizens United7 decision did not directly address the topic of super PACs, but it set the stage for a later ruling that affected their developments. First, as a consequence of Citizens United, corporations and unions are free to use their treasury funds to make expenditures (such as for airing political advertisements) explicitly calling for election or defeat of federal or state candidates (independent expenditures or IEs), or for advertisements that refer to those candidates during pre-election periods, but do not necessarily explicitly call for their election or defeat (electioneering communications). Previously, such advertising would generally have had to be financed through voluntary contributions raised by traditional PACs (those affiliated with unions or corporations, nonconnected committees, or both).

A second case paved the way for what would become super PACs. Following Citizens United, on March 26, 2010, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia held in SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission8 that contributions to PACs that make only IEs—but not contributions—could not be constitutionally limited.

Also known as independent-expenditure-only committees (IEOCs), the media and other observers called these new political committees simply super PACs. The term signifies their structure akin to traditional PACs but without the contribution limits that bind traditional PACs. As discussed in the next section, after Citizens United and SpeechNow, the FEC issued advisory opinions and regulations that offered additional guidance on super PAC activities.

Why Might Super PACs Matter to Congress?

Brief Answer

The development of super PACs is one of the most recent chapters in the long debate over political spending and political speech. Super PACs emerged quickly after the Citizens United and SpeechNow decisions and have become a powerful spending force in federal elections. Although the FEC amended its rules in 2014 to recognize super PACs, those who are concerned about the role of these groups in federal elections generally contend that more stringent regulations, or a statutory change from Congress, is necessary.9 In addition, super PACs can substantially affect the political environment in which Members of Congress and other federal candidates compete, as discussed later in this report.

Discussion

Several policy issues and questions surrounding super PACs might be relevant as Congress considers how or whether to pursue legislation or oversight. These topics appear to fall into three broad categories:

- the state of law and regulation affecting super PACs,

- transparency surrounding super PACs, and

- how super PACs shape the campaign environment.

For those advocating their use, super PACs represent newfound (or restored) freedom for individuals, corporations, and unions to contribute as much as they wish for independent expenditures that advocate election or defeat of federal candidates. Opponents of super PACs contend that they represent a threat to the spirit of modern limits on campaign contributions designed to minimize potential corruption. Additional discussion of these subjects appears throughout this report.

How Have Super PACs Been Regulated?

Brief Answer

Thus far, Congress has not enacted legislation specifically addressing super PACs. Existing regulations and law governing traditional PACs apply to super PACs in some cases. In addition, the FEC issued rules in 2014 that recognized super PACs and reflected advisory opinions that the commission issued soon after Citizens United and SpeechNow.

Discussion

The FEC is responsible for administering civil enforcement of FECA and related federal election law.10 A December 2011 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NRPM) posing questions about what form post-Citizens United rules should take11 remained open until late 2014, reflecting an apparent stalemate over the scope of the agency's response to the ruling. In October 2014, the commission approved rules essentially to remove portions of existing regulations that Citizens United had invalidated, such as spending prohibitions on corporate and union treasury funds.12 These rules recognized the presence of super PACs and reflected the Citizens United and SpeechNow precedents permitting corporations (and, implicitly, unions) to make IEs and super PAC contributions. The rules did not, however, create substantially new prohibitions on or requirements for super PACs. In fact, the FEC's most substantive guidance on super PACs had already appeared in FEC advisory opinions (AOs).13 These AOs responded to questions posed by members of the regulated community, as those governed by campaign finance law are sometimes known, seeking clarification about how the commission believed campaign finance regulation and law applied to specific situations applicable to super PACs.

Six AOs are particularly relevant for understanding how the FEC interpreted the Citizens United and SpeechNow decisions with respect to super PACs, as briefly summarized below.

- In July 2010, the FEC approved two related AOs in response to questions from the Club for Growth (AO 2010-09) and Commonsense Ten (AO 2010-11).14 In light of Citizens United and SpeechNow, both organizations sought to form PACs that could solicit unlimited contributions to make independent expenditures (i.e., form super PACs). The commission determined that the organizations could do so. In both AOs, the commission advised that while post-Citizens United rules were being drafted, political committees intending to operate as super PACs could supplement their statements of organization (FEC form 1) with letters indicating their status.15 The major policy consequence of the Club for Growth and Commonsense Ten AOs was to permit, based on Citizens United and SpeechNow, super PACs to raise unlimited contributions supporting independent expenditures.16

- In June 2011, the commission approved an AO affecting super PAC fundraising. In the Majority PAC and House Majority PAC AO (AO 2011-12), the commission determined that federal candidates and party officials could solicit contributions for super PACs within limits.17 Specifically, the commission advised that contributions solicited by federal candidates and national party officials must be within the PAC contribution limits established in FECA (e.g., $5,000 annually for individual contributions).18 It is possible, however, that federal candidates could attend fundraising events—but not solicit funds themselves—at which unlimited amounts were solicited by other people.

- In AO 2011-11, the commission responded to questions from comedian Stephen Colbert. Colbert's celebrity status generated national media attention surrounding the request, which also raised substantive policy questions. The Colbert request asked whether the comedian could promote his super PAC on his nightly television program, The Colbert Report.19 In particular, Colbert asked whether discussing the super PAC on his show would constitute in-kind contributions from Colbert Report distributor Viacom and related companies. An affirmative answer would trigger FEC reporting requirements in which the value of the airtime and production services would be disclosed as contributions from Viacom to the super PAC. Colbert also asked whether these contributions would be covered by the FEC's "press exemption," thereby avoiding reporting requirements.20 In brief, the commission determined that coverage of the super PAC and its activities aired on the Colbert Report would fall under the press exemption and need not be reported to the FEC. If Viacom provided services (e.g., producing commercials) referencing the super PAC for air in other settings, however, the commission determined that those communications would be reportable in-kind contributions.21 Viacom would also need to report costs incurred to administer the super PAC.22 Although the super PAC subsequently terminated its operations, the AO guidance potentially remains relevant for other super PACs that might in the future operate in connection with media organizations.

- On December 1, 2011, the FEC considered a request from super PAC American Crossroads. In AO 2011-23, Crossroads sought permission to air broadcast ads featuring candidates discussing policy issues. American Crossroads volunteered that the planned ads would be "fully coordinated" with federal candidates ahead of the 2012 elections, but also noted that they would not contain express advocacy calling for election or defeat of the candidates.23 In brief, the key question in the AO was whether Crossroads could fund and air such advertisements without running afoul of coordination restrictions designed to ensure that goods or services of financial value are not provided to campaigns in excess of federal contribution limits.24 (As a super PAC, Crossroads is prohibited from making campaign contributions; coordinated expenditures would be considered in-kind contributions.) Ultimately, the FEC was unable to reach a resolution to the AO request. In brief, at the open meeting at which the AO was considered, independent commissioner Stephen Walter and Democrats Cynthia Bauerly and Ellen Weintraub disagreed with their Republican counterparts, Caroline Hunter, Donald McGahn, and Matthew Petersen, about how FEC regulations and FECA should apply to the request.25 As a result of the 3-3 deadlocked vote, the question of super PAC sponsorship of "issue ads" featuring candidates appears to be unsettled. Although deadlocked votes are often interpreted as not granting permission for a planned campaign activity, some might also regard the deadlock as a failure to prohibit the activity. As a practical matter, if the FEC is unable to reach agreement on approving or prohibiting the conduct, it might also be unable to reach agreement on an enforcement action against a super PAC that pursued the kind of advertising Crossroads proposed.

- Also at its December 1, 2011, meeting, the FEC considered AO request 2011-21, submitted by the Constitutional Conservatives Fund PAC (CCF), a leadership PAC.26 CCF and other leadership PACs are not super PACs, although the CCF AO request is arguably relevant for super PACs. Specifically, in AO request 2011-21, CCF sought permission to raise unlimited funds for use in independent expenditures, as super PACs do. The FEC held, in a 6-0 vote, that because CCF is affiliated with a federal candidate, the PAC could not solicit unlimited contributions. To the extent that the CCF request is relevant for super PACs, it suggests that leadership PACs or other committees affiliated with federal candidates may not behave as super PACs.

What Information Must Super PACs Disclose?

Brief Answer

Super PACs must follow the same reporting requirements as traditional PACs. This includes filing statements of organization27 and regular financial reports detailing most contributions and expenditures.

Discussion

In the Commonsense Ten AO, the FEC advised super PACs to meet the same reporting obligations as PACs known as nonconnected committees (e.g., independent organizations that are not affiliated with a corporation or labor union). These reports are filed with the FEC28 and made available for public inspection in person or on the commission's website.

Super PACs and other political committees must regularly29 file reports with the FEC30 summarizing, among other things,

- total receipts and disbursements;

- the name, address, occupation, and employer31 of those who contribute more than $200 in unique or aggregate contributions per year;

- the name and address of the recipient of disbursements exceeding $200;32 and

- the purpose of the disbursement.33

Reporting timetables for traditional PACs, which apply to super PACs, depend on whether the PAC's activity occurs during an election year or non-election year.

- During election years, PACs may choose between filing monthly or quarterly reports. They also file pre- and post-general election reports and year-end reports.34

- During non-election years, PACs file FEC reports monthly or "semi-annually" to cover two six-month periods. The latter include two periods: (1) "mid-year" reports for January 1-June 30; and (2) "year-end" reports for July 1-December 31.35

Super PACs also have to report their IEs.36 IEs are reported separately from the regular financial reports discussed above. Among other requirements,

- independent expenditures aggregating at least $10,000 must be reported to the FEC within 48 hours; 24-hour reports for independent expenditures of at least $1,000 must be made during periods immediately preceding elections;37 and

- independent expenditure reports must include the name of the candidate in question and whether the expenditure supported or opposed the candidate.38

The name, address, occupation, and employer for those who contributed at least $200 to the super PAC for IEs would be included in the regular financial reports discussed above, but donor information is not contained in the IE reports themselves. In addition, as the "Is Super PAC Activity Sufficiently Transparent?" section discusses later in this report, the original source of some contributions to super PACs can be concealed (either intentionally or coincidentally) by routing the funds through an intermediary.

Overall, How Much Money Have Super PACs Raised and Spent?

Brief Answer

Since their inception in the middle of the 2010 election cycle, super PACs have raised and spent more than $2 billion. More than half that amount—almost $1.4 billion as of June 2016—went toward IEs supporting or opposing federal candidates. (Remaining amounts apparently were spent on items such as administrative expenses and nonfederal races.)39

Discussion

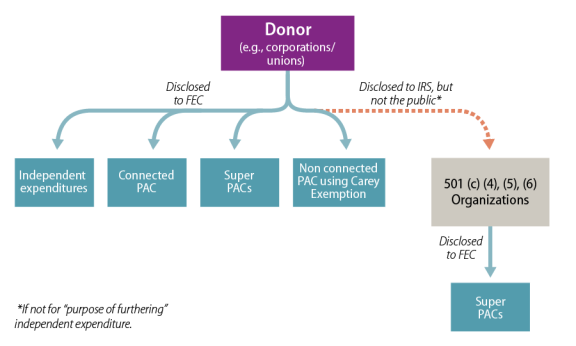

Table 2 and Figure 1 below summarize super PAC receipts, disbursements, and IEs between the 2010 and 2014 election cycles.

|

Cycle |

Total Receipts |

Total Disbursements |

Total Independent Expenditures |

|

2010 |

$92,796,286 |

$90,939,186 |

$64,884,926 |

|

2012 |

$823,988,592 |

$796,888,222 |

$606,808,037 |

|

2014 |

$696,189,286 |

$687,239,439 |

$339,401,450 |

Source: Data for the 2012 and 2014 cycles appear in Federal Election Commission (FEC) data in files accompanying "Table 3a, Independent Expenditure-Only Political Committee Financial Activity" in the respective 24-month super PAC (IEOC) summary for the listed election cycles, http://fec.gov/press/campaign_finance_statistics.shtml. The FEC provided commensurate 2010 data in response to a CRS request.

|

Figure 1. Super PAC Receipts, Disbursements, |

|

|

Source: Data for the 2012 and 2014 cycles appear in Federal Election Commission (FEC) data in files accompanying "Table 3a, Independent Expenditure-Only Political Committee Financial Activity" in the respective 24-month super PAC (IEOC) summary for the listed election cycles, http://fec.gov/press/campaign_finance_statistics.shtml. The FEC provided commensurate 2010 data in response to a CRS request. |

Table 3 summarizes financial activity of the 10 super PACs reporting the largest receipts and expenditures for 2014. The table reports total disbursements rather than only IEs. Therefore, it is important to note that although these entities raised and spent the most overall, other super PACs might have more direct impact on the election through higher spending on IEs that call for election or defeat of particular candidates.

Table 3. The 10 Super PACs Reporting the Most Receipts and Disbursements

for the 2014 Election Cycle

|

Committee Name |

Total Receipts |

Total Disbursements |

|

NEXTGEN CLIMATE ACTION COMMITTEE |

$77,836,875 |

$74,032,090 |

|

SENATE MAJORITY PAC |

$66,914,461 |

$66,914,067 |

|

HOUSE MAJORITY PAC |

$38,081,217 |

$37,982,069 |

|

AMERICAN CROSSROADS |

$31,764,829 |

$31,381,853 |

|

FREEDOM PARTNERS ACTION FUND INC |

$29,111,416 |

$25,755,878 |

|

ENDING SPENDING ACTION FUND |

$24,451,993 |

$24,201,752 |

|

NEA ADVOCACY FUND |

$21,824,216 |

$20,892,879 |

|

AMERICANS FOR RESPONSIBLE SOLUTIONS-PAC |

$21,343,357 |

$19,532,856 |

|

WORKERS' VOICE |

$20,384,973 |

$20,333,958 |

|

INDEPENDENCE USA PAC |

$17,457,953 |

$17,767,774 |

Source: CRS analysis of Federal Election Commission (FEC) data files accompanying "Table 3a, Independent Expenditure-Only Political Committee Financial Activity" in the 24-month super PAC (IEOC) activity summary for the 2014 election cycle, http://fec.gov/press/campaign_finance_statistics.shtml.

Note: Committee names appear as listed in the cited source.

Some general patterns of super PAC activities have emerged since 2010, as noted briefly below.

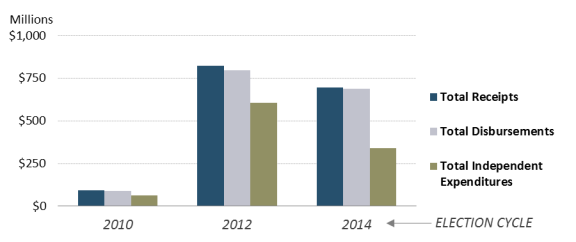

- Super PACs have proliferated since they first emerged in 2010. As Figure 2 below shows, approximately 80 organizations quickly formed in response to the 2010 Citizens United and SpeechNow rulings. By 2012, 455 super PACs were active in federal elections. The figure increased to almost 700 in 2014—an increase of more than 800% in just four years.40

|

Figure 2. Super PACs Reporting Financial Activity, 2010-2014 |

|

|

Source: CRS figure based on Federal Election Commission (FEC) data files accompanying "Table 3a, Independent Expenditure-Only Political Committee Financial Activity" in the 24-month super PAC (IEOC) activity summary for relevant election cycles, http://fec.gov/press/campaign_finance_statistics.shtml. Notes: The figure excludes super PACs that registered with the FEC but did not report receipts, disbursements, or both greater than $0. Consequently, the number of super PACs shown in the figure differs from sources that list all registrants (e.g., the FEC Committee Summary File). |

- Super PAC financial activity also has increased rapidly. The first super PACs spent a total of approximately $93 million, almost $65 million of which was spent on IEs advocating for or against candidates, during the 2010 cycle.41 These figures are notable not only for their size, but also because most of these organizations did not operate until the summer of the election year. As Table 2 shows, super PAC fundraising and spending escalated quickly in subsequent election cycles. As would be expected, super PAC spending peaked, at almost $800 million, during the only presidential election year for which they were in operation, 2012. As of this writing in the final months of the 2016 presidential election, the pattern appears likely to continue. Partial-cycle FEC summary data show that by March 2016, super PACs already had raised more than they did during the entire 2014 cycle ($697.7 million versus $696.2 million). They also had already spent more than $529 million, including $275.6 million on IEs. By June 2016, super PACs had spent $772.7 million, including $367.8 million on IEs.42 Center for Responsive Politics analysis of FEC data accessed in August 2016 found more than 2,300 super PACs had raised almost $1 billion and spent almost $500 million in IEs.43

- From the beginning, a relatively small proportion of super PACs have been responsible for most super PAC financial activity. Just 10 super PACs accounted for almost 75% of all super PAC spending in 2010.44 In 2012, although more than 800 super PACs registered with the FEC, only about 450 of those groups reported raising or spending funds (as shown in Figure 2).45 Furthermore, although all super PACs combined spent less than $100 million in 2010, two Republican super PACs alone—Restore Our Future and American Crossroads—each spent more than $100 million in 2012. These two groups were the only super PACs that raised or spent more than $100 million in 2012. The most financially active Democratic super PAC, Priorities USA Action, spent approximately $75 million. All other super PACs individually raised and spent less than $50 million.46 A small number of groups continued to dominate in 2014, when the five highest-spending super PACs alone were responsible for disbursing more than $236 million, about 35% of the total for all super PACs that election cycle.47

- Despite some exceptions, for-profit corporations generally have not made large contributions to super PACs as some predicted they would after Citizens United.48 On the other hand, as discussed elsewhere in this report, for-profit corporations, unions, and other entities are widely believed to support super PACs through politically active tax-exempt organizations (e.g., 501(c)(4)s). Furthermore, some super PACs (and politically active tax-exempt organizations) have played what one group of researchers call "ephemeral" roles, in which they engage in particular races but subsequently shift their focus or cease operations altogether.49

- Just as a small number of super PACs is responsible for most spending, relatively few donors provide super PAC funding. As noted elsewhere in this report, super PACs must report their donors, but existing reporting obligations fall to the entity receiving the contribution rather than to the contributor. As a result, there is no definitive "official" summary of all contributions from specific individuals.50 Media accounts and other research have reported that a small group of donors provides some of the most consequential super PAC funding. During the 2016 cycle, for example, the Washington Post reported that as of February of the election year, 41% of super PAC funds raised at that point in the cycle had come "from just 50 mega-donors and their relatives."51 Some super PACs with few donors (including candidate relatives) have played major roles in promoting particular candidates, especially in presidential races.52

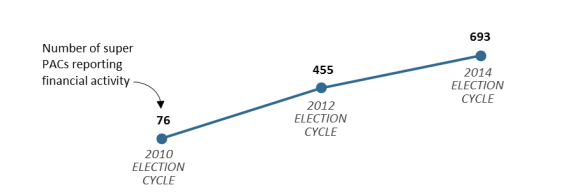

- In some cases, super PACs are the primary "outside" spenders in campaigns. The extent to which super PACs choose to become involved in individual races varies substantially. As Figure 3 below shows, super PACs accounted for about half of all IEs in the 2012 cycle. Super PACs were less dominant in IEs overall in 2014, but they nonetheless spent more on IEs than did political parties.53 In the 2016 election cycle (not shown in the figure), super PAC spending accounted for almost 84.7% of IEs made through June 30.54

|

Figure 3. Super PAC Independent Expenditures Compared with |

|

|

Source: CRS figure based on Federal Election Commission (FEC) data files accompanying "Table 1, Independent Expenditure Totals (Overall Summary Data)," for the 2014 and 2012 (which includes 2010 data) cycles, http://fec.gov/press/campaign_finance_statistics.shtml. |

What Major Super PAC Legislative or Oversight Issues Might be Relevant for Congress?

Brief Answer

As super PACs become increasingly common in politics—but without recognition in statute—Congress could consider conducting oversight or pursue legislation to clarify these new groups' place in federal campaigns. Super PAC activity might also be relevant for congressional oversight of the FEC as that agency continues to consider various rulemakings and reporting requirements. Looking ahead, questions about super PAC relationships with other organizations (particularly the issues of coordination and contribution limits), transparency, and their effect on future elections may be of particular interest.

Discussion

Super PACs address some of the most prominent and divisive issues in campaign finance policy. Most attention to super PACs is likely to emphasize their financial influence in elections, as is typically the case when new forces emerge on the campaign finance scene. Underlying that financial activity is law, regulation, or situational guidance (e.g., advisory opinions)—or the lack thereof—that shape how super PACs operate and are understood.

Policy Approaches

As noted previously, despite Citizens United and SpeechNow, Congress has not amended federal election law to reflect the rise of super PACs or otherwise regulate the groups, although the FEC has issued regulations and advisory opinions based on court decisions. If Congress considers it important to recognize the role of super PACs in election law itself, Congress could amend FECA to do so. As it has generally done with other forms of PACs, Congress could also leave the matter to the FEC's regulatory discretion.55 The following points may be particularly relevant as Congress considers how or whether to proceed.

- If Congress believes that additional clarity would be beneficial, it could choose to enact legislation. This approach might be favored if Congress wishes to specify particular requirements surrounding super PACs, either by amending FECA, or by directing the FEC to draft rules on particular topics. Legislation has a potential advantage of allowing Congress to specify its preferences on its timetable. It has the potential disadvantage of falling short of sponsors' wishes if sufficient agreement cannot be found to enact the legislation.

- Relatively little legislation has been devoted specifically to super PACs. Table 4 below briefly summarizes relevant legislation introduced during the 114th Congress.

Table 4. 114th Congress Legislation Substantially Related to Super PACs

(The table contains only those provisions directly relevant for super PACs.)

|

Legislation, Short Title |

Primary Sponsor |

Committee Referral |

Brief Summary of Super PAC Provisions |

Most Recent Major Action |

|

Empowering Citizens Act |

Price (N.C.) |

House Administration; Ways and Means |

Would prohibit federal candidates and officeholders from fundraising for super PACs; primarily public financing legislation |

— |

|

Stop Super PAC-Candidate Coordination Act |

Price (N.C.) |

House Administration |

Would create statutory definition of prohibited candidate-super PAC coordination |

— |

|

DISCLOSE 2015 Act |

Van Hollen |

House Administration; Judiciary; Ways and Means |

Would extend various disclaimer and disclosure requirements applicable to campaign-related spending by super PACs, corporations, unions, and tax-exempt organizations in certain circumstances |

— |

|

We the People Act of 2016 |

Price (N.C.) |

House Administration; Judiciary; Oversight and Government Reform; Financial Services; Ways and Means |

In addition to other provisions not directly relevant to super PACs, contains Stop Candidate-Super PAC Coordination Act provisions to create statutory definition of prohibited candidate-super PAC coordination |

— |

|

We the People Act of 2016 |

Udall |

Rules and Administration |

In addition to other provisions not directly relevant to super PACs, contains Stop Candidate-Super PAC Coordination Act provisions to create statutory definition of prohibited candidate-super PAC coordination |

— |

|

Democracy Is Strengthened by Casting Light On Spending in Elections Act of 2015 |

Whitehouse |

Rules and Administration |

Would extend various disclaimer and disclosure requirements applicable to campaign-related spending by super PACs, corporations, unions, and tax-exempt organizations in certain circumstances |

— |

|

Stop Super PAC-Candidate Coordination Act |

Leahy |

Rules and Administration |

Would create statutory definition of prohibited candidate-super PAC coordination |

— |

|

Empowering Citizens Act |

Udall |

Rules and Administration |

Would prohibit federal candidates and officeholders from fundraising for super PACs; primarily public financing legislation |

__ |

Source: CRS analysis of bill texts.

Notes: The table excludes provisions in the listed bills that are not directly relevant for super PACs. For additional information about provisions in these and other campaign finance legislation, see CRS Report R41542, The State of Campaign Finance Policy: Recent Developments and Issues for Congress, by R. Sam Garrett. In addition, congressional requesters may obtain from the author a CRS congressional-distribution memorandum that briefly summarizes all 114th Congress legislation that is substantially related to campaign finance.

- As an alternative to legislation, Congress could choose to defer to the FEC (or perhaps other agencies, such as the IRS or SEC) with respect to new or amended rules affecting super PACs. This approach has the potential advantage of delegating a relatively technical issue to an agency (or agencies) most familiar with the topic, in addition to freeing Congress to pursue other agenda items. It has the potential disadvantage of producing results to which Congress might object, particularly if the six-member FEC deadlocks, as it has done on certain high-profile issues in recent years. If Congress chose the rulemaking approach, providing as explicit instructions as possible about the topics to be addressed and the scope of regulations could increase the chances of the rules reflecting congressional intent. Doing so might also increase the chances that consensus could be achieved during the implementation process.

Potential Policy Questions and Issues for Consideration

Despite high-profile activity, much about super PACs remains unknown. The following points may warrant consideration as the super PAC issue continues to emerge.

What is the Relationship Between Super PACs and Other Political Committees or Organizations?

As noted previously, the FEC considers super PACs to be political committees subject to the requirements and restrictions contained in FECA and FEC regulations. As such, super PACs are prohibited from coordinating their activities with campaigns or other political committees (e.g., parties).56 Some observers have raised questions about whether super PACs were or are really operating independently or whether their activities might violate the spirit of limits on contributions or coordination regulations. The following points may be relevant as Congress assesses where super PACs fit in the campaign environment.

- Concerns about super PAC independence appear to be motivated at least in part by the reported migration of some candidate campaign staff members to super PACs that have stated their support for these candidates. Similarly, some super PACs reportedly have been organized or otherwise substantially supported by individuals with long-standing personal or professional connections to the candidates those super PACs support.57

- A second source of concern may be that legally separate organizations (e.g., 501(c) tax-exempt political organizations, which are generally not regulated by the FEC or federal election law) operate alongside some super PACs.58 Media reports (and, it appears, popular sentiment) sometimes characterize these entities, despite their status as unique political committees or politically active organizations, as a single group. Some also question whether large contributions—that would be prohibited if they went to candidate campaigns—were essentially routed through super PACs as IEs. Donors who wish to do so may contribute to candidate campaigns in limited amounts and in unlimited amounts to super PACs supporting or opposing these or other candidates.

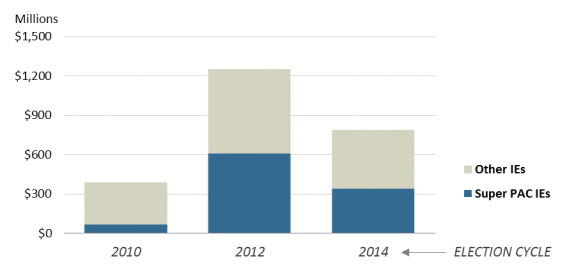

- As noted previously, super PACs must identify donors who contributed at least $200. This requirement sheds light on contributions that go directly to super PACs, but not necessarily those that go indirectly to super PACs. In particular, the original source of contributions to trade associations or other organizations that later fund IEs through super PACs could go unreported. For example, assume Company A made a contribution to Trade Association B, and placed no restrictions on how the contribution could be used. Trade Association B then used Company A's funds to contribute to a super PAC. Trade Association B—not Company A—would be reported as the donor on FEC reports. As Figure 4 below shows, an essential element in this relationship in this series of events is whether the original contribution was "made for the purpose of furthering" an independent expenditure. In practice, this means that those who do not wish their identities to be reported to the FEC could make an unrestricted donation to an intermediary organization, which then funnels the money to a super PAC. (They might also choose to donate to a politically active 501(c) entity for strategic or policy reasons, such as supporting advocacy generally, which might include contributions to super PACs.) By contrast, if a corporation, union, or individual chose to contribute directly to a super PAC, or to make IEs itself, the entity's identity would have to be disclosed to the FEC.

- Because super PACs are prohibited from coordinating their activities with campaigns, Congress might or might not feel that gathering additional information about super PACs' independence is warranted. Whether or not super PACs are sufficiently independent and whether their activities are tantamount to contributions could be subject to substantial debate and would likely depend on individual circumstances.

- Concerns about the potential for allegedly improper coordination between super PACs and the candidates they favor are a prominent aspect of debate.59 Some might contend that more coordination would benefit super PACs and candidates by permitting them to have a unified agenda and message, whereas others could argue that prohibiting any coordination is important to preserve independence. Candidate frustration with "outside" spending is not unique to super PACs. Indeed, uncoordinated activities by traditional PACs, parties, and interest groups are a common occurrence in federal elections. Some observers contend that the ability to coordinate should, therefore, be increased. Others, however, warn that permitting more communication between outside groups and campaigns would facilitate circumventing limits on campaign contributions. If Congress chose to limit potential coordination between super PACs and candidates or parties, it could amend FECA to supersede the existing coordination standard, which is currently housed in FEC regulations and has long been complex and controversial.60

- Over time, some "traditional" PACs—not operating as super PACs—have adapted super PAC organizational characteristics. Specifically, in October 2011, the FEC announced that, in response to an agreement reached in a recent court case (Carey v. FEC),61 the agency would permit nonconnected PACs—those that are unaffiliated with corporations or unions—to accept unlimited contributions for use in independent expenditures. The agency directed PACs choosing to do so to keep the IE contributions in a separate bank account from the one used to make contributions to federal candidates.62 As such, nonconnected PACs that want to raise unlimited sums for IEs may create a separate bank account and meet additional reporting obligations rather than forming a separate super PAC.

Is Super PAC Activity Sufficiently Transparent?

In addition to the organizational questions noted above—which may involve transparency concerns—Congress may be faced with examining whether enough information about super PACs is publicly available to meet the FECA goal of preventing real or apparent corruption.63 The following points may be particularly relevant as Congress considers transparency surrounding super PACs.

- In the absence of additional reporting requirements, or perhaps amendments clarifying the FEC's coordination64 rules, determining the professional networks that drive super PACs will likely be left to the media or self-reporting. In particular, relationships between super PACs and possibly related entities, such as 527 and 501(c) organizations, generally cannot be widely or reliably established based on current reporting requirements.65

- As is the case with most political committees, assessing super PAC financial activities generally requires using multiple kinds of reports filed with the FEC. Depending on when those reports are filed, it can be difficult to summarize all super PAC spending affecting federal elections. Due to amended filings, data can change frequently. Reconciling IE reports with other reports (e.g., those filed after an election) can also be challenging and require technical expertise. Streamlining reporting for super PACs might have benefits of making data more available for regulators and researchers. On the other hand, some may argue that because super PAC activities are independent, their reporting obligations should be less than for political committees making or receiving contributions.

- Because super PACs (and other PACs) may file semi-annual reports during non-election years, information about potentially significant fundraising or spending activity might go publicly unreported for as long as six months. Consequently, some super PACs did not file detailed disclosure reports summarizing their late "off-year" activity until early election-year primaries are held. For example, some super PAC spending that occurred in late 2011 or late 2015 ahead of the 2012 and 2016 New Hampshire and South Carolina primaries, and Iowa caucuses, was not disclosed until well after the contests were held.

- Given the preceding points, a policy question for Congress may be whether the implications of the current reporting requirements represent "loopholes" that should be closed or whether existing requirements are sufficient. If additional information is desired, Congress or the FEC could revisit campaign finance law or regulation to require greater clarity about financial transactions. As with disclosure generally, the decision to revisit specific reporting requirements will likely be affected by how much detail is deemed necessary to prevent corruption or accomplish other goals.

Conclusion

Super PACs are only one element of modern campaigns. Regular media attention to super PACs might give an overstated impression of these organizations' influence in federal elections. Nonetheless, super PACs have joined other groups in American politics, such as parties and 527 organizations, that are legally separate from the candidates they support or oppose, but whom some regard as practically an extension of the campaign. As with most campaign finance issues, whether Congress decides to take action on the super PAC issue, and how, will likely depend on the extent to which super PAC activities are viewed as an exercise in free speech by independent organizations versus thinly veiled extensions of individual campaigns.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For a discussion of current campaign finance issues generally, see CRS Report R41542, The State of Campaign Finance Policy: Recent Developments and Issues for Congress, by R. Sam Garrett. |

| 2. |

The original version of this report, issued in 2011 and available to congressional clients upon request for historical reference, was among the first comprehensive analyses of super PACs in federal elections. This initial version and several updates tracked super PAC activity in recent election cycles and spending in particular races. The current update includes selected analysis of quantitative data for illustrative purposes, but it is not intended to be a comprehensive analysis of super PAC financial activity. Some of the financial totals in this version of the report differ slightly from data in previous versions. Unless otherwise noted, this update relies of FEC summary statistics (cited throughout) that were unavailable when this report was initially issued. As the Appendix in previous versions explains, those versions relied on CRS analysis of independent expenditure reports and committee summary files in the absence of summary statistics that are now available. Both approaches relied on the most current data available at the time. |

| 3. |

On the definition of IEs, see 52 U.S.C. §30101(17). |

| 4. |

130 S. Ct. 876 (2010); and 599 F.3d 686 (D.C. Cir. 2010) respectively. |

| 5. |

The discussion here is not intended to be exhaustive. For additional information, see, for example, 11 C.F.R. §109.20 and 11 C.F.R. §109.21. |

| 6. |

As the term is commonly used, 527 refers to groups registered with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) as Section 527 political organizations that seemingly intend to influence federal elections in ways that may place them outside the FECA definition of a political committee. By contrast, political committees (which include candidate committees, party committees, and political action committees) are regulated by the FEC and federal election law. There is a debate regarding which 527s are required to register with the FEC as political committees. For additional discussion, see CRS Report RS22895, 527 Groups and Campaign Activity: Analysis Under Campaign Finance and Tax Laws, by L. Paige Whitaker and Erika K. Lunder. All political committees, including super PACs, are Section 527 political organizations for tax purposes. |

| 7. |

130 S. Ct. 876 (2010). For additional discussion, see CRS Report R43719, Campaign Finance: Constitutionality of Limits on Contributions and Expenditures, by L. Paige Whitaker. |

| 8. |

599 F.3d 686 (D.C. Cir. 2010). |

| 9. |

For the 2014 FEC rules implementing Citizens United, see Federal Election Commission, "Independent Expenditures and Electioneering Communications by Corporations and Labor Organizations," 79 Federal Register 62797, October 21, 2014. |

| 10. |

For additional discussion, see CRS Report R44318, The Federal Election Commission: Overview and Selected Issues for Congress, by R. Sam Garrett; and CRS Report R44319, The Federal Election Commission: Enforcement Process and Selected Issues for Congress, by R. Sam Garrett. |

| 11. |

Federal Election Commission, "Independent Expenditures and Electioneering Communications by Corporations and Labor Organizations," 248 Federal Register 80803, December 27, 2011. |

| 12. |

Federal Election Commission, "Independent Expenditures and Electioneering Communications by Corporations and Labor Organizations," 79 Federal Register 62797, October 21, 2014. |

| 13. |

AOs provide an opportunity to pose questions about how the commission interprets the applicability of FECA or FEC regulations to a specific situation (e.g., a planned campaign expenditure). AOs apply only to the requester and within specific circumstances, but can provide general guidance for those in similar situations. See 52 U.S.C. §30108. |

| 14. |

The AOs are available from the FEC website at http://saos.nictusa.com/saos/searchao. |

| 15. |

For sample letters, see Appendix A in AOs 2010-09 and 2010-11. A template is available at http://www.fec.gov/pdf/forms/ie_only_letter.pdf. |

| 16. |

AOs do not have the force of regulation or law. Although AOs can provide guidance on similar circumstances in other settings, some may argue that AOs cannot, in and of themselves, create broad guidance about super PACs or other topics. |

| 17. |

Majority PAC was formerly known as Commonsense Ten, the super PAC discussed above. |

| 18. |

On limitations on contributions to PACs, see Table 1 in CRS Report R41542, The State of Campaign Finance Policy: Recent Developments and Issues for Congress, by R. Sam Garrett. This section assumes a super PAC would achieve multicandidate committee status. Multicandidate committees are those that have been registered with the FEC (or, for Senate committees, the Secretary of the Senate) for at least six months; have received federal contributions from more than 50 people; and (except for state parties) have made contributions to at least five federal candidates. See 11 C.F.R. §100.5(e)(3). In practice, most PACs attain multicandidate status automatically over time. |

| 19. |

Colbert's super PAC was popularly known as the Colbert Super PAC. It was registered with the FEC as Americans for a Better Tomorrow, Tomorrow. The committee terminated its operations in 2012. |

| 20. |

On the press exemption, see 52 U.S.C. §30101(9)(B)(i); 11 C.F.R. §100.73; 11 C.F.R. §100.132; and discussion in AO 2011-11, pp. 6-8. |

| 21. |

See AO 2011-11, pp. 7-9. AOs are available from the FEC website at http://saos.nictusa.com/saos/searchao. |

| 22. |

Ibid., p. 9. |

| 23. |

See AO request (AOR) 2011-23, p. 5. The AOR was filed, as is typical, in a letter from the requester's counsel to the FEC General Counsel. See Letter from Thomas Josefiak and Michael Bayes to Anthony Herman, General Counsel, FEC, October 28, 2011, in the AO 2011-23 documents at http://saos.nictusa.com/saos/searchao. |

| 24. |

Coordination is discussed later in this report. On coordination and the three-part regulatory test for coordination, see, respectively 52 U.S.C. §30116(a)(7)(B) and 11 C.F.R. §109.21. |

| 25. |

Commissioners Bauerly and Weintraub issued a "statement of reasons" document explaining their rationale, as did Commissioner Walther and the three Republican commissioners. See Cynthia L. Bauerly and Ellen L. Weintraub, Statement on Advisory Opinion Request 2011-23 (American Crossroads), Federal Election Commission, Washington, DC, December 1, 2011; Steven T. Walther, Advisory Opinion Request 2011-23 (American Crossroads): Statement of Commissioner Steven T. Walther, Federal Election Commission, Washington, DC, December 1, 2011; and Caroline C. Hunter, Donald T. McGahn, and Matthew S. Petersen, Advisory Opinion Request 2011-23 (American Crossroads): Statement of Vice Chair Caroline C. Hunter and Commissioners Donald T. McGahn and Matthew S. Petersen, Federal Election Commission, Washington, DC, December 1, 2011. |

| 26. |

Leadership PACs are PACs affiliated with Members of Congress that provide an additional funding mechanism to support colleagues' campaigns. Although historically the purview of members of the House and Senate leadership, many Members of Congress now have leadership PACs. Leadership PACs are separate from the candidate's principal campaign committee. |

| 27. |

This is FEC form 1. Essentially, it provides the FEC with information about how to contact the campaign and identifies the treasurer. |

| 28. |

Political committees devoted solely to Senate activities file reports with the Secretary of the Senate, who transmits them to the FEC for public positing. In theory, if a super PAC were devoted solely to affecting Senate campaigns, it is possible the super PAC would file with the Secretary rather than with the FEC. Nonetheless, the information would be transmitted to the FEC. |

| 29. |

Reporting typically occurs quarterly. Pre- and post-election reports must also be filed. Non-candidate committees may also file monthly reports. See, for example, 52 U.S.C. §30134 and the FEC's Campaign Guide series for additional discussion of reporting requirements. |

| 30. |

As noted previously, unlike other political committees, Senate political committees (e.g., a Senator's principal campaign committee) file reports with the Secretary of the Senate, who transmits them to the FEC. See 52 U.S.C. §30102(g). |

| 31. |

The occupation and employer requirements apply to contributions from individuals. |

| 32. |

FECA contains some exceptions. For example, all disbursements used to make contributions to another political committee must be itemized, regardless of amount. See 52 U.S.C. §30104(b)(4). |

| 33. |

FEC policy guidance has stated that "when considered along with the identity of the disbursement recipient, must be sufficiently specific to make the purpose of the disbursement clear." In general, however, political committees have broad leeway in describing the purpose of disbursements. For example, the commission has noted that generic terms such as "administrative expenses" are inadequate, but "salary" is sufficient. The quoted material and additional discussion appears in Federal Election Commission, "Statement of Policy: Purpose of Disbursement," 72 Federal Register 887-889, January 9, 2007. |

| 34. |

Quarterly reports are due to the FEC on April 15, July 15, and October 15. The final quarterly report is due January 31 of the next year. Monthly reports are due to the commission 20 days after the end of the previous month. The year-end report is due by January 31 of the year after the election. Pre-election reports summarizing activity for the final weeks of an election period must be filed with the FEC 12 days before the election. Monthly or quarterly reports are not required if their due dates fall near an otherwise required pre-election report. Post-general reports must be filed 30 days after the election; post-primary reports are not required. Additional requirements apply to special elections. See 11 C.F.R. §104.5(c)(1). |

| 35. |

The reports are due to the FEC by July 31 and January 31 respectively. See 11 C.F.R. §104.5(c)(2). |

| 36. |

Separate reporting obligations apply to electioneering communications. |

| 37. |

See, for example, 52 U.S.C. §30104(g). |

| 38. |

52 U.S.C. §30104(g)(3)(B). |

| 39. |

These figures are based on CRS calculations using the data cited in this section. |

| 40. |

These figures exclude hundreds of groups that registered with the FEC but subsequently reported no (or minimal) financial activity. CRS calculated the percentages based on Federal Election Commission (FEC) data in files accompanying "Table 3a, Independent Expenditure-Only Political Committee Financial Activity" in the respective 24-month super PAC (IEOC) summary for the listed election cycles, http://fec.gov/press/campaign_finance_statistics.shtml. The FEC provided commensurate 2010 data in response to a CRS request. |

| 41. |

Remaining amounts apparently were spent on items such as administrative expenses and nonfederal races. These totals appear in Table 2 of this report. |

| 42. |

These data appear in the files accompanying Federal Election Commission (FEC), "Table 3a, Independent Expenditure-Only Political Committee Financial Activity" for the 2016 cycle, http://fec.gov/press/campaign_finance_statistics.shtml. |

| 43. |

See Center for Responsive Politics, "Super PACs," http://www.opensecrets.org/pacs/superpacs.php?cycle=2016. This CRS report will be updated after the FEC finalizes 2016-cycle data. |

| 44. |

The FEC provided CRS with data on spending by individual committees. The text in this section is based on CRS analysis of those data, including aggregating the totals and calculating percentages listed in the text. |

| 45. |

The FEC subsequently administratively terminated some super PACs that had no financial activity. |

| 46. |

This information is based on CRS analysis of committee summary files and independent expenditure reports. Additional methodological information appears in the Appendix of previous versions of this report, which is available to congressional clients upon request for historical reference. |

| 47. |

These figures are based on CRS analysis of Federal Election Commission (FEC) data files accompanying "Table 3a, Independent Expenditure-Only Political Committee Financial Activity" in the 24-month super PAC (IEOC) activity summary for the 2014 election cycle, http://fec.gov/press/campaign_finance_statistics.shtml. |

| 48. |

See, for example, Kenneth P. Doyle, "Super PACs Get Millions From Corporations," Daily Report for Executives, August 11, 2015, accessed via CRS subscription; and Matea Gold and Anu Narayanswamy, "Super PACs are on Pace to Raise $1 Billion," The Washington Post, May 12, 2016, p. A6. |

| 49. |

For additional discussion generally, see, for example, Robert G. Boatright, Michael J. Malbin, and Brendan Glavin, "Independent Expenditures in Congressional Primaries after Citizens United: Implications for Interest Groups, Incumbents, and Political Parties," Interest Groups & Advocacy, vol. 5, no. 2 (May 2016), pp. 119-140. See also Wesleyan Media Project and Center for Responsive Politics, Outside Group Activity, 2000-20016, special report, Middletown, CT, August 24, 2016, http://mediaproject.wesleyan.edu/releases/disclosure-report/. |

| 50. |

In brief, although individual contributors must be identified as described previously in this report, this information does not provide readily available summaries of all contributions from the same donor. For additional discussion, see, for example, CRS Report R41542, The State of Campaign Finance Policy: Recent Developments and Issues for Congress, by R. Sam Garrett; and CRS Report R43334, Campaign Contribution Limits: Selected Questions About McCutcheon and Policy Issues for Congress, by R. Sam Garrett. |

| 51. |

Matea Gold and Anu Narayanswamy, "50 Donors with Outsize Impact," The Washington Post, April 17, 2016, p. A1. |

| 52. |

See, for example, Robert Faturechi and Jonathan Stray, "Rapid Rise in Super PACs Dominated by Single Donors," ProPublica, April 20, 2015, https://www.propublica.org/article/rapid-rise-in-super-pacs-dominated-by-single-donors. |

| 53. |

This distinction does not appear in the table. In 2014, super PACs made $339.4 million in IEs compared with $229.0 million for parties. See Federal Election Commission, "Table 1, Independent Expenditure Totals (Overall Summary Data)," for relevant election cycles, http://fec.gov/press/campaign_finance_statistics.shtml. |

| 54. |

CRS calculated this percentage based on FEC data that show super PACs made $367.8 million in IEs, compared with $434.2 million in IEs overall. See Federal Commission, "FEC Summarizes First 18 Months of Campaign Activity for 2015-2016 Election Cycle," FEC Record online newsletter, September 2016, http://www.fec.gov/pages/fecrecord/2016/october/18monthsummary2016cycle.shtml. |

| 55. |

For example, traditional PACs, known as separate segregated funds, originally arose from advisory opinions in the 1970s. Congress later incorporated the PAC concept into FECA amendments. For a historical overview, see, for example, Robert E. Mutch, Campaigns, Congress, and Courts: The Making of Federal Campaign Finance Law (New York: Praeger, 1988), pp. 152-185; and Anthony Corrado, "Money and Politics: A History of Federal Campaign Finance Law," in The New Campaign Finance Sourcebook, Anthony Corrado, Thomas E. Mann, Daniel R. Ortiz, and Trevor Potter (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2005), pp. 7-47. |

| 56. |

As noted previously, this report reflects common understanding of regulation and law as applied to super PACs. Subsequent changes in law or regulation that explicitly address super PACs could yield alternative findings. |

| 57. |

See, for example, Nicholas Confessore, "Lines Blur Between Candidates and PACs with Unlimited Cash," New York Times, August 27, 2011, p. A1; Nicholas Confessore, "How Deep Pockets of One Family Helped Shake Up Trump Campaign," New York Times, August 19, 2016, p. A15; Steven Greenhouse, "A Campaign Finance Ruling Turned to Labor's Advantage," New York Times, September 26, 2011, p. A1; Fredreka Schouten, "Advocates Blue Lines Between Campaigns and Super PACs," The Arizona Republic, September 27, 2015, p. B3; and Kenneth P. Vogel, "Super PACs' New Playground: 2012," Politico, August 10, 2011, online edition retrieved via LexisNexis. |

| 58. |

For example, American Crossroads is a registered super PAC; Crossroads Grassroots Policy Strategies (GPS) is a 501(c)(4) tax-exempt organization. The same is reportedly true for perceived Democratic counterparts Priorities USA Action and Priorities USA, respectively. See, for example, the sources noted in the previous footnote; and Eliza Newlin Carney, "The Deregulated Campaign," CQ Weekly Report, September 19, 2011, p. 1922. |

| 59. |

The Justice Department has successfully prosecuted at least one criminal case involving prohibited coordination between a campaign committee and a super PAC. See U.S. Department of Justice, "Campaign Manager Sentenced to 24 Months for Coordinated Campaign Contributions and False Statements," press release, June 12, 2015, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/campaign-manager-sentenced-24-months-coordinated-campaign-contributions-and-false-statements. |

| 60. |

The coordinated communication regulations are at 11 C.F.R. 109.21. |

| 61. |

Civ. No. 11-259-RMC (D.D.C. 2011). |

| 62. |

Federal Election Commission, "FEC Statement on Carey v. FEC: Reporting Guidance for Political Committees that Maintain a Non-Contribution Account," press release, October 5, 2011, http://www.fec.gov/press/Press2011/20111006postcarey.shtml. |

| 63. |

For additional discussion of disclosure matters generally, see CRS Report R41542, The State of Campaign Finance Policy: Recent Developments and Issues for Congress, by R. Sam Garrett. |

| 64. |

See, for example, 11 CFR §109.20-11 CFR §109.23. |

| 65. |

See, for example CRS Report R41542, The State of Campaign Finance Policy: Recent Developments and Issues for Congress, by R. Sam Garrett; and Eliza Newlin Carney, "The Deregulated Campaign," CQ Weekly Report, September 19, 2011, p. 1922. |