Introduction

Individual nation states have developed intellectual property rights (IPR) regimes reflecting their domestic needs and priorities, although the United States and other countries have acceded to several IP-related conventions and treaties since the 1800s. Over time, IPR protection and enforcement have come to the forefront as a key international trade issue for the United States—largely due to the role of intellectual property in an innovative U.S. economy and as a U.S. competitive advantage—and figure prominently in the multilateral trade policy arena and in regional and bilateral U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs).

Congress has legislative, oversight, and appropriations responsibilities related to IPR and trade policy more generally. This role of Congress stems from the U.S. Constitution, which provides Congress with the power to "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries" and to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations."1 Since 1988, Congress has included IPR as a principal U.S. trade negotiating objective, and has passed laws such as "Special 301" to advance protection and enforcement of U.S. IPR in global markets. The context for congressional interest may include policy concerns such as: the role of IPR in the U.S. economy; the impact of IPR infringement on U.S. commercial, health, safety, and security interests; the effect of foreign indigenous innovation and localization requirement on U.S. IPR; and the balance or relationship between protecting IPR to stimulate innovation and advancing other public policy goals.

This report discusses the different types of IPR and IPR infringement, the role of IPR in the U.S. economy, estimated losses associated with IPR infringement, the organizational structure of IPR protection, U.S. trade policy, and issues for Congress regarding IPR and international trade.

IPR Definitions

Types of IPR

IPR are legal rights granted by governments to encourage innovation and creative output. They ensure that creators reap the benefits of their inventions or works. They take a variety of forms, such as patents, trade secrets, copyrights, trademarks, or geographical indications. Through IPR, governments grant a temporary legal monopoly to innovators by giving them the right to limit or control the use of their creations by others. IPR may be traded or licensed to others, usually in return for fees and/or royalty payments. Although the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement) provides minimum standards for IPR protections, such rights are granted on a national basis and are, in general, enforceable only in the country in which they are granted. However, WTO members are obligated to abide by WTO rules, and their IPR enforcement practices can be challenged by other WTO members through the WTO dispute settlement process.

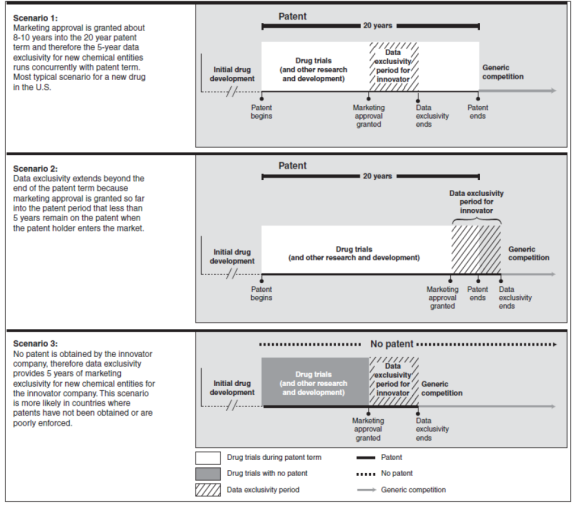

Patents

The Patent Act (Title 35 of the United States Code) governs the issuance and use of patents in the United States. Patents are granted for inventions of new products and processes (known as utility patents). Patents also may be granted for new designs and plant varieties. For an invention to be patentable, it must be new and "non-obvious" (involving an inventive step), and have a potential industrial or commercial application. The patent provides the holder with the exclusive right to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing into the United States the patented invention for a period of 20 years.2 The patent right is based on the proposition that granting inventors a temporary monopoly over their invention will encourage innovation and promote the expenditure of money on research and development (R&D). The temporary monopoly may allow a patent holder to recoup these up-front costs by charging higher prices for the patented invention. In return for this economic rent, the patent holder must disclose the content of the invention to the public, along with test data and other information concerning the invention. This is meant to spur further creativity by those seeking to build on the patent after its expiration. Domestically, patents are granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) of the Department of Commerce.

Trade Secrets

Any type of valuable information, including a "formula, pattern, compilation, program, device, method, technique, or process," may be kept by its owner as a trade secret. To be a trade secret, the information must derive independent economic value from not being generally known or readily ascertainable by others, and be subject to reasonable efforts by the owner to maintain its secrecy.3 Examples of trade secrets include blueprints, customer lists, pricing information, and source code. While protection of patents and copyright is an exclusive matter of federal law, trade secret protection is found not only in federal law, but also in state law. Most states have adopted the Uniform Trade Secret Act (UTSA), a model law drafted by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws.

There are important differences between trade secrets and patents. Individuals do not have to apply for trade secret protection as they would for patents. Protection of trade secrets originates immediately with the creation of the trade secret; there is no process for applying for protection or registering trade secrets. Trade secret protection does not expire unless the trade secret becomes generally known. In contrast, patent applicants must disclose information about their innovation to the PTO in order to acquire a patent. The scope of protection is also different: patents preclude almost all uses of the invention by others, whereas trade secret law only prevents acquisition or misappropriation of a trade secret by improper means, such as theft. Patents thus offer right holders stronger protection but for a limited period of time. While applying for a patent can be a costly and lengthy process, patents are valuable if the confidentiality of the innovation is fragile (e.g., if the invention is easily reversed engineered) or if the area of research is highly competitive.

Copyright

Protection of copyrights in the United States is based on the Copyright Act (Title 17 of the United States Code). Copyrights protect original expressions of authorship, fixed in physical and/or digital forms. Such protections include literary or artistic works such as books, music, sound recordings, movies, paintings, architectural works, and computer code, and (in some cases) databases. Traditionally, copyrights differed from patents in that there was no claim to industrial applicability or novelty of the idea. The expression of the idea—the particular way it was conveyed in words, images, or sounds—and not the idea itself, was being copyrighted. While some of the criteria for copyrights differ from those of patents, the objective is the same: furthering creativity by promoting investments of time, money, and effort to create works of cultural, social and economic significance. U.S. law provides copyright protection for life of the author plus 70 years for personal works, or 120 years from creation (or 95 years from publication) for corporate works. Copyrights may be registered by the U.S. Copyright Office of the Library of Congress, although protection arises immediately upon fixation in a tangible medium of expression.

Trademarks

Trademark protection in the United States is governed jointly by state and federal law. The main federal statute is the Lanham Act of 1946 (Title 15 of the United States Code). Trademarks permit the seller to use a distinctive word, name, symbol, or device to identify and market a product or company. Marks can also be used to denote services from a particularly company. The trademark allows quick identification of the source of a product, and for good or ill, can become an indicator of a product's quality. If for good, the trademark can be valuable by conveying an instant assurance of quality to consumers. Trademark law serves to prevent other companies with similar merchandise from free-riding on the association of quality with the trademarked item. Thus, a trademarked good may command a premium in the marketplace because of its reputation. To be eligible for a trademark, the words or symbol used by the business must be sufficiently distinctive; generic names of commodities, for example, cannot be trademarked. Trademark rights are acquired through use or through registration with the PTO.

A related concept to trademarks is geographical indications (GIs), which are also protected by the Lanham Act. The GI acts to protect the quality and reputation of a distinctive product originating in a certain region; however, the benefit does not accrue to a sole producer, but rather the producers of a product originating from a particular region. GIs are generally sought for agricultural products, or wines and spirits. Protection for GIs is acquired in the United States by registration with the PTO, through a process similar to trademark registration.

Theft of Intellectual Property

Infringement

IPR infringement is the misappropriation or violation of the IPR. In the case of patents, infringement of a patent owner's exclusive rights involves a third party's unauthorized use, sale, or importation of the patented invention. Copyright infringement occurs when a third party engages in reproducing, performing, or distributing a copyrighted work without the consent of the copyright owner. The greatest challenge to the patent right in the context of international trade is infringement in foreign countries, or non-observance by WTO member states of the minimum standards of the TRIPS Agreement. In addition to the term infringement, other terms are used to describe certain violations of IPR.

Piracy

The term "piracy" generally refers to copyrights and generally refers to widespread, intentional infringement. The major challenge facing copyright protection is piracy, either through physical duplication of the work, illegal dissemination of copyrighted material (such as computer software, music, or movies) over the internet, and/or participation in commercial transactions of copyrighted materials without the consent of the copyright owner. Piracy can also mean the registration or use of a famous foreign trademark that is not registered in the country or is invalid because the trademark has not been used.

Counterfeiting

An imitation of a product is referred to as a "counterfeit" or a "fake." Counterfeit products are manufactured, marketed, and distributed with the appearance of being the genuine good and originating from the genuine manufacturer.4 The purpose of counterfeit goods is to deceive consumers about their origin and nature, harming both the trademark owner and consumers. Counterfeiting and copying of original goods are major challenges for trademarked products. The counterfeited product can be sold for a premium because of its association with the original item, while reducing the sales of the original items. Consumer experience with a counterfeited good of inferior quality can damage the reputation of the trademark product. Additionally, counterfeited goods of inferior quality may be potentially harmful to health and safety. Popular examples of counterfeit products include fake fashionwear (e.g., counterfeits of brand-name bags and watches) or fake pharmaceutical products (e.g., counterfeits of brand-name prescription medicines).

Trade Secret Theft

Misappropriation of trade secrets is a civil violation under federal and state laws. Theft of trade secrets may also be a federal crime in some circumstances. Industrial espionage refers to the stealing of trade secret information that relates to a product in interstate or foreign commerce, to the economic benefit of third parties and to the injury of the trade secret owner (18 U.S.C. 1832). Economic espionage refers to the stealing of a trade secret when the intent to benefit a foreign power (18 U.S.C. 1831).5 Trade secret theft can occur through cyber means (see below).6

Cybertheft

Criminal activity, including IP theft, increasingly occurs in the online environment. Internet-related crimes are often referred to as cybercrime, though no one definition appears to exist for it within the U.S. government.7 One of type of cybercrime is cybertheft, which broadly may be defined as crimes in which a computer is used to steal money or other things of value and can include "embezzlement, fraud, theft of intellectual property, and theft of personal and financial data."8 Other terms that may encompass internet-related IPR theft include cyber intrusions and cyberattacks.

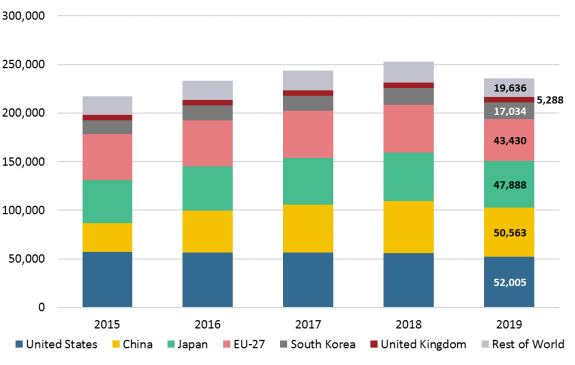

Innovation Indicators

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), innovation is the "implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), or process, a new marketing method, or a new organizational method." Possible innovation-related indicators include activities concerning commercializing inventions and new technologies.9 Trends in the total number of patent applications under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), an international patent filing system administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), may be illustrative (see Figure 1).10 The United States remains the source of the world's largest number of PCT filing applications, followed by China and Japan; together, these three countries accounted for almost 64% of all PCT applications filed in 2019. China overtook the European Union (EU) and Japan in 2017.11 While China has become a top patent filer, the number of patents (quantity) does not necessarily reflect leadership in patent quality and innovativeness.12 The top fields of technology in PCT filings were digital communication, computer technology, audio-visual technology, electrical machinery/apparatus/energy, and optics.13

Role of IP in U.S. Economy and Trade

Intellectual property generally is viewed as a long-standing strategic driver of U.S. productivity, economic growth, employment, higher wages, and exports. It also is considered a key source of U.S. comparative advantage, such as in innovation and high-technology products. Nearly every industry depends on it for its businesses. Industries that rely on patent protection include the aerospace, automotive, computer, consumer electronics, pharmaceutical, and semiconductor industries. Copyright-reliant industries include the software, data processing, motion picture, publishing, and recording industries. Trademarks and trade secrets are widely used in most industries, but certain industries are especially trademark-intensive, including the apparel, pharmaceuticals, and electronics industries.14 Other industries that directly or indirectly benefit from IPR protection include retailers, traders, and transportation businesses, which support the distribution of goods and services derived from intellectual property.15

Overall Role

IP-intensive industries play a major role in the U.S. economy and international trade. What follows are some findings from a 2016 study by the U.S. Department of Commerce.16

- U.S. economic impact. In 2014, a subset of the most intellectual property-intensive industries directly supported 27.9 million jobs in the United States, or about 18% of total U.S. employment. They also indirectly supported 17.6 million U.S. jobs via the supply chain in other industries. In 2014, the wages of employees working in IP-intensive industries tended to be about 46% higher on average than those working in non-IP-intensive industries. These industries accounted for about $6.6 trillion in value added to the U.S. economy, more than one-third of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).

- U.S. trade in goods. In 2014, IP-related merchandise exports amounted to $842 billion (52% of total U.S. merchandise exports), while IP-related merchandise imports reached $1,391 billion (about 70% of total U.S. merchandise imports). Key sectors for IP-intensive merchandise exports include semiconductor and electric parts, basic chemicals, pharmaceuticals and medicine, measuring and medical instrument, and computer and peripheral equipment.17

- U.S. trade in services. In 2012, exports of services by IP-intensive industries totaled about $81 billion (about 12% of total U.S. private services exports). Key sources of services exports included the software publishing, financial services, computer systems design and related services, motion picture and video, and management and technical consulting industries. The study did not provide information on imports of services by IP-intensive industries, though it should be noted that the United States runs an overall surplus in international trade in services.18

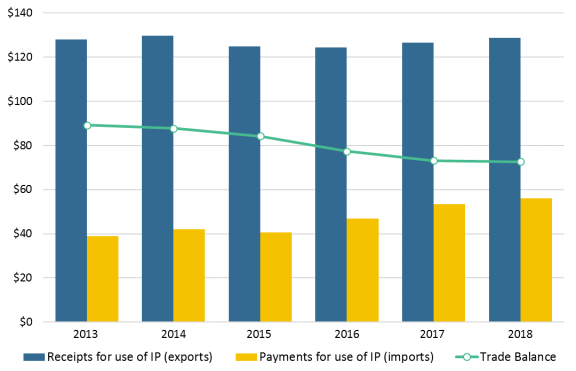

Royalty and Licensing Charges

The role of IP-intensive industries in U.S. trade in services includes charges for U.S. IP, i.e., receipts (exports) and payments (imports) of royalties and licensing fees. Rights holders may authorize the use of technologies, trademarks, and entertainment products that they own to entities in foreign countries, resulting in revenues through royalties and license fees. Between 2013 and 2018, U.S. receipts for use of royalties and licensing fees have remained relatively steady while there has been a slight increase in payments from U.S. firms to foreign firms. In 2018, U.S. receipts from cross-border trade in royalties and license fees (relating to patent, trademark, copyright, and other intangible rights) totaled $129 billion, while U.S. payments of royalties and license fees to foreign countries amounted to $56 billion, resulting in a trade surplus of $73 billion (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 2. U.S. Trade in Services: Royalties and License Fees from Intellectual Property Use, 2013-2018 (billions of U.S. dollars) |

|

|

Source: BEA, U.S. International Services data. |

Specific U.S. Industries

Industry-specific figures may further demonstrate the role of IP in the U.S. economy. For example:

- Copyright industries. According to a study commissioned by the International Intellectual Property Alliance (IIPA), in 2017, industries categorized as part of the "core" copyright industries (e.g., computer software, videogames, books, newspapers, periodicals and journals, motion pictures, recorded music, and radio and television broadcasting) contributed about $1.3 trillion to the U.S. economy ("value-added" to current GDP), representing about 6.9% of the U.S. economy. The study also estimated that the "core" copyright industries employed nearly 5.7 million workers in 2017, representing about 4% of the total U.S. workforce. In addition, the study estimated that foreign sales of certain U.S. copyright sectors totaled $191.2 billion in 2017.19

- Pharmaceutical industry. Between 1998 and 2019, employment in the industry grew 26%. According to the Pharmaceutical Researchers and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), in 2017, American biopharmaceutical companies supported more than 800,000 jobs in R&D and more than 4 million jobs in total, when accounting for indirect jobs (vendors and suppliers) and induced jobs (additional private economic activity).20 According to PhRMA, R&D investment was about $97 billion in 2017.21

- Manufacturing industry: Based on data from a study by NDP Analytics, a private-sector research firm, IP-intensive manufacturing industries performed better than non-IP-intensive industries when comparing key economic measures: R&D investment, wages, exports, value-added, and gross output.22 For example, in 2015, the study estimated that exports per employee for IP-intensive manufacturing industries averaged about $177,033, compared to about $63,778 on average for non-IP-intensive manufacturing industries.23

- Software industry: Software.org, an independent research organization, reported that the software industry directly employs around 3 million workers and more than 14 million when accounting for indirect jobs in 2018. The report also stated that the industry directly contributed $845 billion in value-added to the U.S. GDP and invested almost $83 billion in R&D.24

"Fair Use" Industries

Some advocacy groups assert that empirical analysis of the role of IPR in the U.S. economy may not fully evaluate the economic and commercial benefits of lawful exceptions and limitations to exclusive rights—referred to broadly as "fair use." The "fair use" doctrine provides limitations and exceptions to the exclusive rights afforded by copyright law. It permits limited use of copyrighted works without requiring permission from the right holder in certain cases, examples of which may include news reporting, research, teaching, and library use.25 For example, by one estimate, in 2014, businesses that rely on "fair use" exceptions to U.S. copyright law generated total revenue of $5.6 trillion on average and $2.8 trillion on average of value-added (16% of total U.S. current dollar GDP).26 Additionally, employment associated with "fair use" totaled around 18 million of U.S. employment in 2014, and U.S. exports associated with "fair use" totaled $368 billion in 2014.27

Quantifying IPR Infringement

Advances in information and communications technology (ICT) and declining costs of transportation, spurred by lower trade barriers, have fundamentally changed information and trade flows. Such changes have created new markets for U.S. exporters, but at the same time, have been associated with the proliferation of counterfeiting and piracy on a global scale.

Several factors contribute to the growing problem of IPR infringement. While the costs and time for research and development are high, most IPR infringement occurs with relatively low costs and risks, and a high profit margin. According to PhRMA, it takes a pharmaceutical company over 10 years of R&D on average to create a new drug, with the average cost to develop a drug about $2.6 billion during the 2000s to early 2010s. In 2017, the biopharmaceutical industry invested around $91 billion for research and development in the United States.28 In contrast, drug counterfeiters can lower production costs by using inexpensive, and perhaps dangerous or ineffective, ingredient substitutes.

The development of technologies and products that can be easily duplicated, such as recorded or digital media, also has led to an increase in counterfeiting and piracy. Increasing internet usage has contributed to the distribution of counterfeit and pirated products. Additionally, civil and criminal penalties often are not sufficient deterrents for piracy and counterfeiting. The United States is especially concerned with foreign IPR infringement of U.S. intellectual property. Compared to foreign countries, IPR infringements levels in the United States are considered to be relatively low.29

Limitations on Data Estimating IPR Infringement Costs

Quantification of the economic losses associated with IPR infringement has been a long-standing focus in the academic, policy, and industry literature. Many experts agree that it is difficult to quantify the magnitude of IPR theft with any precision. Reasons may include

- Illicit nature of IPR infringement. Because IPR infringement is illicit and secretive, tools that are used to measure legitimate business activity cannot necessarily be used to measure economic losses from IPR infringement. As such, it may be easier to quantify the positive contribution of copyright industries to the U.S. economy more precisely than to measure the losses to the U.S. economy from copyright piracy.

- Quantifying specific components of economic impact. The economic impact of IPR infringement depends on a range of factors, including the different types of infringing goods being sold, the rate at which consumers substitute buying infringing goods for legitimate goods, and IPR infringement's deterrent effect on R&D and other investment. It may be difficult to measure precisely these components of the economic impact of IPR infringement.30

- Assumptions used to calculate economic impact. Methods for calculating data on counterfeiting and piracy often involve certain assumptions. Estimates of losses from IPR infringement can be highly sensitive to how these assumptions are derived and weighted. The basic economic model employed in some IPR loss estimates assumes that there is substitutability between pirated and legitimate goods. For example, under this model, sales of pirated goods may be equated to revenue losses of legitimate U.S. copyright businesses. Some analysts suggest that legitimate firms face a competition threat only if the individuals purchasing IPR-infringing products would be able and willing to purchase the legitimate product at the price offered when IPR infringement is not present.31 For consumers in developing countries, especially, this assumption may not be tenable.

- IPR infringement in the digital environment. While IPR infringement in the past primarily constituted counterfeiting and piracy of physical goods (such as CDs and books), there has been a growing amount of piracy taking place through digital mediums (such as illegal downloading and streaming of music, movies, and books over the internet). The use of virtual private networks (VPN) also makes it harder to track down the original location of infringement. It may be more complex to measure IPR infringement that takes place in the digital environment, and in turn, more difficult to measure the associated economic losses accurately. Quantifying the economic cost of trade-secret theft may be hampered by the reluctance of companies to disclose such theft, as well as difficulties assessing the monetary value of the secrets stolen. U.S. trade losses due to copyright infringement may be higher than reported because estimates often do not account for all forms of piracy, such as internet piracy. One study estimates that nearly 24% of global internet traffic infringes on copyright.32

- Sources of data. Estimates on economic losses from IPR infringement come from a range of sources, including academic, policy, and industry sources. According to a U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) study, the U.S. government does not systematically collect data or analyze the impacts of counterfeiting and piracy on the U.S. economy. In many cases, the federal government relies on estimates conducted by industry groups. However, companies may be reluctant to disclose their IPR losses because of possible reputational and commercial risks, and industry associations may not always release their proprietary data sources and methods, complicating efforts to verify such estimates.33

International Economic Effects

While assessments of the overall global economic costs of infringement on copyrights, trademarks, and patents are limited, available evidence indicates that the adverse economic effects of global IPR infringement stand in the hundreds of billions of dollars, and are increasing. Customs data on seizures of counterfeit and pirated goods may offer some idea of the magnitudes involved in terms of impact on producers and exporters.

A 2019 study jointly conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) examined international trade in counterfeit goods using customs seizure data for 2014 through 2016.34 The OECD/EUIPO study estimated that the value of international trade in counterfeit and pirated goods was as much as $509 billion (equivalent to 3.3% of world trade) in 2016, up from the estimated $461 billion (2.5% of world trade) in 2013, according to a 2016 joint OECD-EUIPO study.35 The study also noted the industries impacted by IP infringement increased when compared to a previous study: products seized by customs between 2014 and 2016 covered 92% of Harmonized System (HS) chapters compared to 80% for the 2011 to 2013 period.36 OECD noted the significant increase in the use of small parcels as the form of delivery, which presents more challenges for customs officials to detect counterfeit and pirated goods. According to a 2017 OECD study that estimated trade of counterfeit and pirated information and community technology (ICT) goods, fake ICT goods accounted for up to 6.5% of total ICT trade and almost 43% of seized goods infringed the IP rights of U.S. firms.37 Counterfeit ICT goods may be consumer electronics, communication equipment, and electronic components.

Building on the 2016 OECD-EUIPO work is a study commissioned by the Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy (BASCAP), a business initiative organized by the International Chamber of Commerce. According to BASCAP, the total value of counterfeit and pirated products was an estimated $923 billion to $1.1 trillion in 2013, and is projected to reach $1.9 to $2.8 trillion in 2022 (see Table 1).38

Table 1. Estimated International Economic Losses Due to Counterfeiting and Piracy, Selected Years

(billions of U.S. dollars)

|

Category |

2013 |

2022 |

|

Internationally traded counterfeit and pirated products |

$461 |

$991 |

|

Domestically produced and consumed counterfeit and pirated products |

$249-456 |

$524-959 |

|

Digitally pirated products |

$213 |

$384-856 |

|

Total |

$923-1,130 |

$1,900-2,810 |

Source: Frontier Economics, The Economic Impacts of Counterfeiting and Piracy, A Report Commissioned by Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy (BASCAP), February 2017.

Notes: BASCAP economic loss estimates are restricted to the 35 OECD member countries.

U.S. Economic Effects

While specific estimates vary, the available data suggest that U.S. economic losses from IPR infringement are significant.

Customs Seizure Data

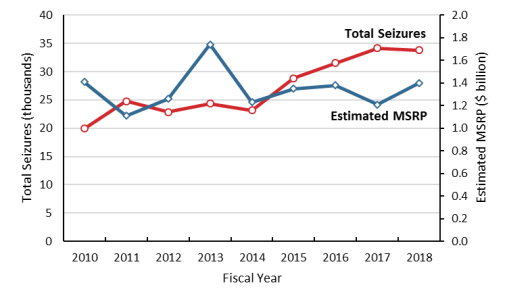

Data on pirated and counterfeit seizures of imports at U.S. borders by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) shed light on the magnitude of the issue in the U.S. context. In FY2018, the number of IPR seizures at the U.S. border totaled 33,810 commodities (shipped by express, mail, cargo, and other ways) valued at $1.4 billion (manufacturer's suggested retail price, MSRP).39 The total number of seizures per year has been increasing while the estimated value remained relatively constant since 2014 (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. Overview of IPR Seizures by CBP FY2010-FY2018 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, IPR annual seizure statistics. |

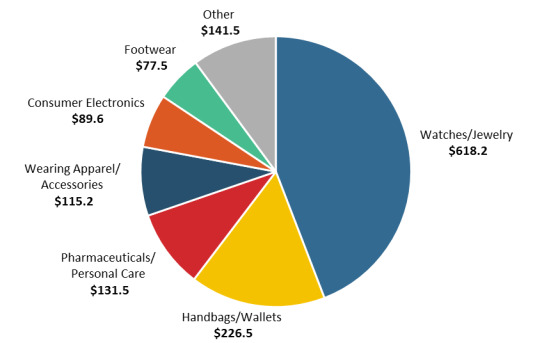

China and Hong Kong ranked as the two largest source economies for seizures by value (see

Table 2). The commodities seized were diverse, with watches/jewelry and handbags/wallets being the top two types seized. Goods seized in FY2018 included shipments of circumvention devices that violated the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA, P.L. 105-304). Customs data may be limited in that they do not reflect digital-based IPR infringement.

Table 2. IPR Seizures at U.S. Borders: Source Economies, FY2018

(Estimated MSRP, millions of U.S. dollars)

|

U.S. Trading Partner |

Estimated MSRP |

% of Total |

|

Total |

$1,399.9 |

100% |

|

China |

$761.1 |

54.0% |

|

Hong Kong |

$440.3 |

31.0% |

|

India |

$20.0 |

1.0% |

|

Korea |

$10.1 |

0.7% |

|

Canada |

$7.8 |

0.6% |

|

Turkey |

$5.8 |

0.4% |

|

Vietnam |

$5.2 |

0.4% |

|

Taiwan |

$5.0 |

0.4% |

|

Malaysia |

$4.7 |

0.3% |

|

Pakistan |

$2.8 |

0.2% |

|

All Others |

$137.1 |

10% |

Source: CRS analysis of data from Department of Homeland Security, "Intellectual Property Rights Seizure Statistics Fiscal Year 2018."

Notes: Based on manufacturer's suggested retail price (MSRP) of goods had they been genuine.

Overall U.S. Estimates

U.S. industries that rely on IPR protection claim to lose billions of dollars in revenue annually due to piracy and counterfeiting. Beyond these direct losses, the United States may face additional "downstream" losses from counterfeiting and piracy. IPR infringement could result in the loss of jobs that would have been created if the infringement did not occur, which could translate into lost earnings by U.S. workers and, in turn, lost tax revenues for federal, state, and local governments.40 Attempts have been made in specific economic sectors to quantify the IPR infringement levels and related losses to legitimate U.S. businesses.

A private Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property estimates the total level of U.S. economic losses to international theft of U.S. IP to be hundreds of billions dollars per year. In 2017, the commission estimated the annual cost to the U.S. economy due to counterfeit goods, pirated software, and theft of trade secrets to be between $225 billion and $600 billion; this estimate does not include the costs of patent infringement and economic espionage because they are difficult to quantify.41 These estimates have been cited widely, including in the annual IP report to Congress by the U.S. Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator (IPEC), a statutorily created position in the White House (P.L. 110-403).42 Efforts also have been made to quantify U.S. economic losses from IPR infringement in terms of specific countries (see text box).

|

Estimate of Losses to U.S. Firms from IPR Infringement in China The U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) estimated losses to "firms in the U.S. IP-intensive economy that conducted business in China in 2009" to be about $48.2 billion in sales, royalties, or license fees due to IPR infringement in China. According to the ITC, this estimate is based on statistical analysis that falls within a broad range of $14.2 billion to $90.5 billion; the range reflects limitations of the underlying data as many firms were unable to calculate losses. In terms of specific sectors, the information/other services sector sustained the largest losses—at a point estimate of $26.7 billion, within a range of $11.8 billion to $48.9 billion. In terms of specific types of IPR infringement, losses from copyright infringement were the largest—at a point estimate of $23.7 billion, within a range of $10.2 billion to $37.3 billion. ITC also estimated that firms in the U.S. IP-intensive economy spent about $4.8 billion (within a range of $279.1 million to $9.4 billion) in 2009 to address possible Chinese IPR infringement. According to submissions from stakeholders to the 2018 U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Section 301 report on China, there are also intangible losses to U.S. firms from IPR infringement. For example, technology transfer requirements when U.S. firms want to invest in the Chinese market may make U.S. firms less competitive in the global market when they lose exclusive rights to their IP. In its submission to USTR for the purpose of the Section 301 report, a U.S. firm estimated that it sustained "more than $120 million in damages in the form of lost sales and revenue" as a result of Chinese state-sponsored cyber theft. The firm further stated that it lost its first-mover advantage and competitiveness in the market. Source: ITC, China: Effects of Intellectual Property Infringement and Indigenous Innovation Policies on the U.S. Economy, Investigation No. 332-519, USITC Publication 4226, May 2011; USTR, Findings of the Investigation into China's Acts, Policies, Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation Under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, March 22, 2018. Note: ITC results reflect responses to an ITC questionnaire to 5,051 U.S. firms in sectors considered to be IP-intensive. ITC used statistical sampling techniques to extrapolate results to the U.S. IP-intensive economy (16.3% of the U.S. economy). The statistical significance of the findings varied. See the report for more information. |

In terms of losses from cyber theft of IP, a 2018 report by McAfee and the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) estimates annual losses to be $10 billion to $12 billion in the United States and $50 billion to $60 billion globally.43

The Organizational Structure of IPR Protection

Given the importance of intellectual property to the U.S. economy and the economic losses associated with counterfeiting and piracy, the United States is a leading advocate of strong global IPR rules. Since the mid-1980s, the United States has integrated IPR policy in its international trade policy activities, pursuing enhanced IPR laws and enforcement through multilateral, regional and bilateral trade agreements, and national trade laws.

Multilateral IPR System

World Trade Organization (WTO)

At the center of the present multilateral trading system is the World Trade Organization, an international organization established in 1995 as the successor to the General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade (GATT).44 The WTO was established as the result of the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations (1986-1994), which led to agreements to liberalize and establish or enhance rules on trade in goods, services, agriculture, and other nontariff barriers to trade. One of the Uruguay Round agreements was the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, which sets minimum standards on IPR protection and enforcement with which all WTO member states must comply. The United States, European countries, and the IPR business community were instrumental in including IPR on the Uruguay Round agenda. Many developing countries were wary of including IPR in trade negotiations, preferring to discuss treatment of IP under the World Intellectual Property Organization (see below) instead. However, developing countries agreed to address IP issues in the WTO after being granted delayed compliance periods, and after achieving negotiating goals on other issues, such as the end of quotas on textiles and clothing.

While previous international treaties on IPR continue to exist, the TRIPS Agreement was the first time that intellectual property rules were incorporated into the multilateral trading system. Two basic tenets of the TRIPS Agreement are national treatment (signatories must treat nationals of other WTO members no less favorably in terms of IPR protection than the country's own nationals) and most-favored-nation treatment (any advantage in IPR protection granted to nationals of another WTO member shall be granted to nationals of all other WTO member states).

Much of the TRIPS Agreement sets out the extent of the agreement's coverage of the various types of intellectual property: patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets, GIs, industrial designs, layout of circuitry design, and test data. The TRIPS Agreement provisions build on several existing IPR treaties administered by the WIPO (discussed below). Another part of the TRIPS Agreement provides standards of enforcement for IPR covered by the agreement. It enumerates standards for civil and administrative procedures and remedies, the application of border measures, and criminal procedures. A Council for the TRIPS Agreement was established to monitor implementation of the agreement and transitional arrangements were devised for developing countries. Finally, the agreement provides for the resolution of disputes under the Uruguay Round Agreement's Dispute Settlement Understanding (see text box). The binding nature of the WTO dispute settlement mechanism, with the possibility of the withdrawal of trade concessions (usually the reimposition of tariffs) for noncompliance, sets this agreement apart from previous IPR treaties that did not have effective dispute settlement mechanisms.

|

U.S. WTO Cases Against China on IPR The United States has filed three cases against China regarding IP: two that challenged Chinese practices under the TRIPS Agreement and one challenge under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). The first two were brought under the George W. Bush Administration and the third under President Trump. DS 362: Measures Affecting the Protection and Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights. In this case brought in 2007, the dispute settlement panel largely ruled in the favor of the United States that

DS542: Certain Measures Concerning the Protection of Intellectual Property Rights. In this case, the United States alleges that China allows domestic firms to continue to use patented technology after a licensing contract ends and requires contracts that discriminate against foreign technology. Consultations were requested in March 2018, and a panel was composed in January 2019. However, the case has been suspended since June 11, 2019, to allow for continued consultations between the United States and China. The United States and China signed a phase one trade agreement on January 15, 2020, to resolve some issues raised by the United States under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. Among other things, China committed to strengthen IP enforcement, but most U.S. concerns on IP, technology transfers, and other issues remain to be addressed in a potential phase two deal.45 |

The TRIPS Agreement also seeks a balance of rights and obligations between protecting private right holders and the obligation "to secure social and cultural development that benefits all."46 Article 7 declares that

... the protection and enforcement of IPR should contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage of producers and users of technological knowledge and in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare and to a balance of rights and obligations.

This paragraph attempts to link the protection of IPR with greater technology transfer, including technology covered by IPR protection, to the developing world. The language itself has been interpreted in various ways. Developed countries have tended to consider this language exhortatory, but developing countries have tried, without much success, to make technology transfer a meaningful obligation within the TRIPS Agreement system. Article 66.2 of the agreement requires developed country members to provide incentives to their enterprises and institutions to promote technology transfer to least-developed countries (LDCs) to assist them in establishing a viable technology base. Developed countries report annually on their efforts to encourage technology transfer.

Complying with international IPR standards may impose greater burdens on developing countries than developed countries. Developing countries generally have to engage in greater efforts to bring their laws, judicial processes, and enforcement mechanisms into compliance with the TRIPS Agreement. Consequently, developing countries were given an extended period of time in which to bring their laws and enforcement mechanisms into compliance with the TRIPS Agreement. Developing countries and post-Soviet states were given an additional four years from the entry into force of the agreement (January 1, 1995). For products that were not covered by a country's patent system (such as pharmaceuticals in many cases), an additional five years was granted to bring such products under coverage. For developing countries, all provisions of the TRIPS agreement should now be in force. For the least developed countries, the phase-in period for IPR commitments was originally extended 10 years to January 1, 2006 (Article 66.1). In 2002, the WTO extended IPR obligations for LDCs with respect to pharmaceuticals to January 1, 2016.47 In addition, the WTO has extended the overall transitional period twice for LDCs.48 As such, LDCs are not required to apply TRIPS Agreement provisions—other than Articles 3, 4, and 5, until July 1, 2021, or until they cease to be LDCs.49 Article 66.1 acknowledges the:

special needs and requirements of least-developed country Members, their economic, financial and administrative constraints, and their need for flexibility to create a viable technological base.

Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health

In agreeing to launch the Doha Round of WTO trade negotiations, trade ministers adopted a "Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health" on November 14, 2001.50 The Declaration sought to alleviate developing country dissatisfaction with aspects of the TRIPS regime. It delayed the implementation of patent system provisions for pharmaceutical products for LDCs until 2016. The declaration committed member states to interpret and implement the agreement to support public health and to promote access to medicines for all. The Declaration recognized certain "flexibilities" in the TRIPS Agreement to allow each member to grant compulsory licenses for pharmaceuticals and to determine what constitutes a national emergency, expressly including public health emergencies such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis or other epidemics. Paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration directed the WTO members to formulate a solution to a related concern, the use of compulsory licensing by countries with insufficient or inadequate manufacturing capability. (See COVID-19 text box below.)

On the eve of the Cancun Ministerial in August 2003, WTO members agreed on a Decision51 to waive the domestic market provision of the TRIPS article on compulsory licensing (Article 31(f)) for exports of pharmaceutical products for "HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and other epidemics" to LDCs and countries with insufficient manufacturing capacity. This Decision was incorporated as an amendment to the TRIPS agreement at the Hong Kong Ministerial in December 2005.

The amendment required ratification from two-thirds of WTO member states. The deadline for ratification was extended five times before the amendment entered into force on January 23, 2017. To date, 102 of the total 162 WTO members52 have ratified the amendment.53 A group of high-income countries (Australia, Canada, the European Union, Iceland, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, and the United States) declared they would not avail themselves of this option as importers.54

The system established by the WTO allows LDCs and countries without sufficient manufacturing capacity to issue a compulsory license to a company in a country that can produce such a product. After a matching compulsory license is issued by the producer country, the drug can be manufactured and exported subject to various notification requirements, as well as quantity and safeguard restrictions. While several exporting countries have established laws and procedures for implementing this system, one (Rwanda) has availed itself of the system to import HIV/AIDS medicines from a generic manufacturer in Canada.55

|

COVID-19 and Access to Medicine The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may reopen a debate over the relationship between WTO trading rules and countries' ability to obtain needed drugs or vaccinations. As noted above, TRIPS created the first enforceable minimum standards for international IPR. It affirmed that patents "shall be available for any inventions…in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are capable of industrial application." It also applied the principle of nondiscrimination on issuance of patents based on technology, place of invention, or site of use. This standard was particularly important to innovative pharmaceutical manufacturers because several countries did not provide for patenting pharmaceutical products prior to TRIPS, or, as in the case of India, provided process patents that covered the manufacturing process but not product itself. However, TRIPS does provide for limited exceptions to the patent right. For example, a country may limit patent rights provided the limitation does not "unreasonably" conflict with the normal exploitation of a patent. The agreement also contains exceptions allowing a party to exclude from patentability items to protect human life and health, as well as diagnostic, therapeutic and surgical measures. The Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health (see above) affirmed that TRIPS provisions should be interpreted to promote public health and access to medicine. TRIPS also allows for compulsory licensing, but places limitations on its use. A compulsory license is an authorization by a government for third parties (such as a company or the government itself) to manufacture or use a product under patent without the permission of the rights holder. TRIPS permits signatories to issue compulsory licenses for patented inventions, if the third party attempts to obtain permission from the patent holder and negotiates reasonable commercial terms, although this requirement can be waived in times of national emergency or other extenuating circumstances. In any case, the third party must provide "adequate" remuneration to the patent holder for the use of the patent. Another restriction limits its use primarily to the domestic market, although countries may issue compulsory license to send products to least-developed countries that lack domestic production capabilities. The allowance for least-developed countries and a clarification of the meaning of national emergency became part of the amendment to TRIPS that originated with the Doha Declaration. U.S. bilateral and regional FTAs largely have not addressed the issue of compulsory licensing, but have contained provisions incorporating the Doha Declaration. In practice, the use of compulsory licenses has been rare; the threat of invoking a compulsory license as a negotiating tactic for countries to obtain better prices from a manufacturer has been more common. The United States generally has sought to dissuade other nations from using compulsory licensing, even placing greater limitations on its use in early U.S. FTAs with Australia, Singapore, and Jordan. However, with the COVID-19 virus, it has been reported that certain governments are taking preliminary steps to revisit its use. Israel is the first country to issue a compulsory license in the context of COVID-19 for the AbbVie drug Kaletra (lopinavir/ ritonavir). The next day AbbVie announced it would no longer enforce patents worldwide for lopinavir/ritonavir.56 In March 2020, the parliaments of Canada and Germany passed legislation clarifying or streamlining the ability to use compulsory licenses in their countries. The National Assemblies of Chile and Ecuador are calling for the use of compulsory licenses in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.57 For more information see, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10436, COVID-19: International Trade and Access to Pharmaceutical Products, by Nina M. Hart. |

World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)

In addition to the WTO, the other main multilateral venue for addressing IPR issues is the World Intellectual Property Organization, a specialized agency affiliated with the United Nations, with its own executive, legislative, and budgetary powers. Established in 1970, following the 1967 WIPO Convention's entry into force, WIPO is charged with fostering the effective use and protection of intellectual property globally. WIPO's mandate focuses exclusively on intellectual property, in contrast to the WTO's broader international trade mandate. WIPO's antecedents are the 1883 Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property and the 1886 Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Work. Most of the substantive provisions of these two treaties are incorporated in the WTO's TRIPS Agreement. WIPO's primary function is to administer a group of IPR treaties which put forth minimum standards for member states. All international IPR treaties, save TRIPS, are administered by WIPO.

The Trump Administration has prioritized the need to counter growing Chinese influence in global functional organizations, including WIPO. Its goal is to preserve the integrity of these organizations to ensure they remain impartial and credible and that their focus and work continue to support U.S. interests and key tenets of the open global trading system, including protection of IPR. In On February 26, 2020, China's ambassador to the United Nations Chen Xu accused the United States of meddling in the upcoming World Intellectual Property Organization leadership election. U.S. diplomats reportedly lobbied to block China's candidate, Wang Binying, and promote Daren Tang, a candidate nominated by Singapore. On March 4, 2020, the WIPO Coordination Committee nominated Daren Tang to be the next Director General of WIPO. Mr. Tang prevailed with 55 votes, while Ms. Wang received 28 votes.

To address digital technology issues not dealt with in the TRIPS Agreement, WIPO established the WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT) and WIPO Performance and Phonograms Treaty (WPPT) in 1996, oftentimes collectively referred to as the "WIPO Internet Treaties." These treaties establish international norms aimed at preventing unauthorized access to and use of creative works on the internet or other digital networks.

Other WIPO activities include patent law harmonization efforts. In 2000, WIPO signatories adopted the Patent Law Treaty (PLT), which called for harmonization of patent procedures. This agreement went into force on April 28, 2005. Discussions began in 2001 for a Substantive Patent Law Treaty (SPLT), which would target harmonization issues specifically related to patent grants, but were put on hold in 2006. Different views reportedly emerged among developed and developing countries on what should be the objectives of substantive harmonization of patent laws, including whether it was an appropriate goal.58 Government leaders participating in the Group of 8 (G-8) meeting in July 2008 called for "accelerated discussions" of the SPLT.59 While discussions remain stalled, the main focus of the WIPO's work in this area has been on "building a technical and legal resource base from which to hold informed discussions in order to develop a work program" on various patent issues.60 Presently, patent law harmonization efforts also are occurring in groupings outside of WIPO, including the Trilateral Cooperation, composed of the European Patent Office, Japan Patent Office, and U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO); another forum is the IP5, composed of the members of the Trilateral Cooperation and also the Korean Intellectual Property Office and China's State Intellectual Property Office.61

WIPO's other functions include assisting member states through training programs, legislative information, intellectual property institutional development, automation and office modernization efforts, and public awareness activities. WIPO's enforcement activities are more limited than those of the WTO. Through its Advisory Committee on Enforcement (ACE), WIPO cooperates with member states to promote international coordination on enforcement activities.

U.S. Trade Law

Several provisions of U.S. law address IPR trade policy and enforcement. These laws are implemented and administered by a number of U.S. government agencies and coordinating bodies (see Table 4 and Appendix A).

Special 301

Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 as amended (P.L. 93-618, 19 U.S.C. §2242) is the principal U.S. statute for identifying foreign trade barriers due to inadequate intellectual property protection. The 1988 Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act (P.L. 100-418) strengthened section 301 by creating "Special 301" provisions, which require the USTR to conduct an annual review of foreign countries' intellectual property policies and practices. By April 30 of each year, the USTR must identify countries that do not offer "adequate and effective" protection of IPR or "fair and equitable market access" to U.S. entities that rely on intellectual property rights. According to an amendment to the Special 301 provisions by the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (P.L. 103-465), the USTR can identify a country as denying sufficient intellectual property protection even if the country is complying with its TRIPS commitments. These findings are submitted in the USTR's annual "Special 301" report (see Table 3). Most recently, the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-125) added trade secrets to list of the types of IPR whose protection by a foreign country is subject to monitoring under Special 301.

The USTR can designate countries in one of several statutorily or administratively created categories:

- Priority Foreign Country: A statutory category for those designated by the USTR as having "the most onerous or egregious acts, policies or practices that deny intellectual property protection and limit market access to U.S. persons or firms depending on intellectual property rights protection" with the "greatest adverse impact (actual or potential) on the relevant United States products." These countries may be investigated under section 301 provisions of the Trade Act of 1974.62 If a country is named as a "Priority Foreign Country," the USTR must launch an investigation into that country's IPR practices. The USTR may suspend trade concessions and impose import restrictions or duties, or enter into a binding agreement with the priority country that would eliminate the act, policy, or practice under scrutiny. Since the advent of the WTO, the United States has brought cases to the WTO rather than impose unilateral retaliation.

- Priority Watch List: An administrative category created by the USTR for those countries whose acts, policies, and practices warrant concern, but who do not meet all of the criteria for identification as Priority Foreign Country. The USTR may place a country on the Priority Watch List when the country lacks proper intellectual property protection and has a market of significant U.S. interest. If designated on the Priority Watch List, the USTR must develop an action plan with respect to that foreign country. If the President, in consultation with USTR, determines that the foreign country fails to meet the action plan benchmarks, then the President may take appropriate action with respect to the foreign country.

- Watch List: An administrative category created by USTR to designate countries that have intellectual property protection inadequacies that are less severe than those on the Priority Watch List, but still attract U.S. attention.

- Section 306 Monitoring. A tool used by USTR to monitor countries for compliance with bilateral intellectual property agreements used to resolve investigations under section 301.

- Out-of-Cycle Review. A tool used by USTR to monitor countries' progress on intellectual property issues, and which may result in status changes for the following year's Special 301 report. In 2010, USTR also began publishing annually the Notorious Markets List as an out-of-cycle review separately from the annual Special 301 report; the report identifies online and physical markets "that reportedly engage in, facilitate, turn a blind eye to, or benefit from substantial copyright piracy and trademark counterfeiting."

|

Special 301 Category |

2020 Special 301 Designation |

|

Priority Foreign Country |

|

|

Priority Watch List |

Algeria, Argentina, Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Ukraine, and Venezuela |

|

Watch List |

Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Guatemala, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mexico, Pakistan, Paraguay, Peru, Romania, Thailand, Trinidad & Tobago, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam |

|

Section 306 Monitoring |

China |

|

Out-of-Cycle Reviews |

|

Source: CRS adaption from USTR, 2020 Special 301 Report.

Notes: For the 2020 Special 301 Report, USTR reviewed the IPR policies and practices of more than 100 countries, and designated 36 of the countries in one of several categories.

The Special 301 statute provides the overall guideline for identifying countries for the various lists. However, placement on one of the lists takes into consideration a host of factors specific to the country, including the level and scope of the country's IPR infringement and their impact on the U.S. economy, the strength of the country's IPR laws and the effectiveness of their enforcement, progress made by the country in improving IPR protection and enforcement in the past year, and the sincerity of the country's commitment to multilateral and bilateral trade agreements. No "weighting criteria" or formula exists to determine the placement of a country on the watch list. Furthermore, no particular threshold exists for determining when a country should be upgraded or downgraded on the list. In making determinations, the USTR gathers information based on its annual trade barriers reports, as well as consultations with a wide variety of sources, including industry groups, other private sector representative, Congress, and foreign governments.

Section 301

Title III of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (Sections 301 through 310, 19 U.S.C. §2411)—collectively referred to as "Section 301"—grants the USTR a range of responsibilities and authorities to investigate and take action to enforce U.S. rights under trade agreements and respond to certain foreign trade practices.63 Section 301 provides a statutory means by which the United States imposes trade sanctions on foreign countries that violate U.S. trade agreements or engage in acts that are "unjustifiable" or "unreasonable" and burden U.S. commerce. Prior to 1995, the United States used Section 301 extensively to pressure other countries to eliminate trade barriers and open markets to U.S. exports. The creation of an enforceable dispute settlement mechanism in the WTO significantly reduced U.S. use of Section 301. The United States retains the flexibility to determine whether to seek recourse for foreign unfair trade practices in the WTO and/or act unilaterally. President Trump has been more willing to act unilaterally to promote what the Administration considers to be "free," "fair," and "reciprocal" trade. The President has imposed increased tariffs under Section 301 on U.S. imports from China due to concerns over China's forced technology transfer requirements and intellectual property rights practices, including cyber-enabled theft of U.S. IPR and trade secrets.64 The Phase I trade deal that the Trump Administration reached with the Chinese government addresses some aspects of IP issues, while leaving other systemic IP issues to address in potential bilateral trade talks.65

Section 337

Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (19 U.S.C. §1337), prohibits unfair methods of competition or other unfair acts in the importation of products into the United States. It also prohibits the importation of articles that infringe valid U.S. patents, copyrights, processes, trademarks, semiconductor products produced by infringing a protected mask work (e.g., integrated circuit designs), or protected design rights. While the statute has been used to counter imports of products judged to be produced by unfair competition, monopolistic, or anti-competitive practices, in recent years it has become increasingly used for its IPR enforcement functions. Under the statute, the import or sale of an infringing product is illegal only if a U.S. industry is producing an article covered by the relevant IPR or is in the process of being established. Unlike other trade remedies, such as antidumping or countervailing duty actions, no showing of injury due to the import is required for "statutory" IP cases.

The U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) administers Section 337 proceedings. ITC investigates complaints either brought to it, mainly by companies, or ones commenced under its own initiative. An administrative law judge provides an initial determination to the ITC which can accept the initial determination or order a further review of it in whole or in part. If the ITC finds a violation, it may issue two types of remedies: exclusion orders or cease and desist orders.

- Exclusion orders, enforced by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), are issued to stop infringing imports from entering the United States. Exclusion orders can be general or limited. General exclusion orders apply to all products that are found in violation of Section 337, regardless of source. Limited exclusion orders apply to the goods originating from the specific firm(s) found to be in violation of Section 337. Limited exclusion orders typically are the more commonly issued type of exclusion order. The ITC issues general exclusion orders if such a broad-based exclusion is necessary to prevent the circumvention of the limited exclusion order, or if there is a pattern of violation and it is difficult to identify the source of infringing products.

- Cease and desist orders, enforced by ITC, require the firm to stop the sale of the infringing product in the United States.

The ITC may consider several public interest criteria and decline to issue a remedy. Also, the President may disapprove a remedial order during a 60-day review period for "policy reasons." A presidential review of a remedial order often considers several relevant factors, including "(1) public health and welfare; (2) competitive conditions in the U.S. economy; (3) production of competitive articles in the United States; (4) U.S. consumers; and (5) U.S. foreign relations, economic and political."66

The number of active Section 337 investigations conducted by the ITC generally has trended upward over the past decade (see text box). The overwhelming majority of Section 337 cases involve allegations by private firms of patent infringement. Investigations concern a range of technologies, including smartphones and other wireless devices, smart televisions, semiconductors, GPS devices, windshield wiper blades, and tires.67 According to the ITC, there is "substantial overlap between the industries that dominate our IP docket and the four industries determined in a Department of Commerce study to be the most patent-intensive industries in the United States"—computer and peripheral equipment, communications equipment, semiconductor and other electronic components, and other computer and electronic products.68

|

FY2019 Section 337 Statistics Number of new complaints and ancillary proceedings – 58 (compared to 40 in FY2006) Number of investigations and ancillary proceedings completed – 60 (compared to 30 in FY2006) Number of active investigations: 127 in FY2019 (compared to 70 in FY2006) Types of unfair acts alleged in active investigations: sole patent infringement – 110; solely trademark infringement – 3; solely trade secret misappropriation – 4; combination of unfair acts alleged - 10 Number of investigations completed on the merits: 22 (compared to 12 in FY2006) Length of investigations completed on the merits: shortest – 9.4 months, longest – 29.3 months, average -17.7 months (compared to, in FY2006, shortest – 3.5 months, longest 19.0 months, and average – 12.0 months) Number of active exclusion orders (as of December 31, 2018): 114 Number of remedial orders issued: general exclusion orders - 5, limited exclusion orders - 10, cease and desist orders – 16 (compared to, in FY2006, GEOs – 3, LEOs -5, CDOs – 2) Settlement/consent order share of total number of investigations terminated – 33% of 42 investigations (compared to 46% of 26 investigations in FY2006) Complaints withdraw share of total number of investigations terminated – 12% of 42 investigations (compared to 8% of 26 investigations in FY2006) Source: U.S. International Trade Commission. |

Legislative efforts related to Section 337 have focused on addressing jurisdictional problems associated with holding foreign websites accountable for piracy and counterfeiting, renewing congressional and public debate about the balance between protecting U.S. intellectual property and promoting innovation.69 Congress could take these issues up again, as well as other issues, including the effectiveness of CBP's enforcement of Section 337 exclusion orders. A 2014 Government Accountability Office study found that CBP's management of its exclusion order process at ports contained weaknesses that result in inefficiencies and an increased risk of infringing products entering U.S. commerce; it recommended that CBP update its internal guidance related to sharing information sharing for trade alerts and monitoring.70 CBP has since implemented recommendations to ensure that active exclusion orders from the ITC are posted on CBP's intranet.71

Generalized System of Preferences

The Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) is a U.S. trade and development program that provides preferential duty-free entry to certain products from designated developing countries.72 The purpose of the program is to foster economic growth in developing countries by increasing their export markets. GSP operates on a nonreciprocal basis. The Trade Act of 1974, as amended (19 U.S.C. §2461-67), authorized the GSP for a ten-year timeframe, and the program has been renewed from time to time. Congress most recently extended the GSP program until December 31, 2020, in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141).

Although GSP is nonreciprocal, it can be used to promote stronger intellectual property protection and enforcement abroad. Under the GSP statute, the President must consider a set of mandatory criteria that a country must fulfill in order to be designated as a GSP beneficiary. Additionally, the President may evaluate a country on the basis of certain discretionary criteria, including the country's provision of IPR protection.73 For example, in light of heightened concern over India's intellectual property environment, President Trump removed India from the Generalized System of Preferences beneficiary list on May 31, 2019.74

The GSP program undergoes an annual review by the GSP Subcommittee of the interagency Trade Policy Staff Committee (TPSC), which is headed by the USTR. As part of its evaluation, the TPSC addresses concerns about specific country practices (such as intellectual property protection) and makes recommendations to the President. In October 2019, the President partially restored GSP benefits to Ukraine for certain products based on the determination that the country made progress towards providing IPR protection; Ukraine's GSP benefits had been suspended in December 2017.75 Based on industry petitions concerning IPR protection, USTR reports as ongoing its reviews of the country practices of Indonesia, South Africa, and Uzbekistan.76

|

Department of Commerce |

Department of Homeland Security |

Department of Justice |

Other Federal Agencies |

Coordinating and Advisory Bodies |

|

Patent and Trademark Office International Trade Administration |

Customs and Border Protection Immigration and Customs Enforcement U.S. Secret Service |

Civil Division Criminal Division Federal Bureau of Investigation Office of Justice Program U.S. Attorney's Office |

U.S. Trade Representative Department of Health and Human Services (Food and Drug Administration) Library of Congress (Copyright Office) Department of State U.S. Agency for International Development U.S. International Trade Commission |

Office of the U.S. Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator (IPEC) National Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center (IPR Center) Interagency for Trade Implementation, Monitoring, and Enforcement (ICTIME) Private Sector Advisory Committee System |

Source: CRS analysis.

Notes: For more information, see Appendix A.

U.S. Trade Promotion Authority and Negotiating Objectives

Trade promotion authority (TPA) is the time-limited authority that Congress uses to set U.S. trade negotiating objectives, to establish notification and consultation requirements, and to have implementing bills for certain reciprocal trade agreements considered under expedited procedures, provided certain statutory requirements are met.77 In recent grants of TPA, IPR issues have become important negotiating objectives.

IPR negotiating objectives for FTAs were first enacted by the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-418). The statute sought enactment and enforcement of adequate IPR protection from negotiating partners. It also sought to strengthen international rules, dispute settlement, and enforcement procedures through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and other existing intellectual property conventions. This negotiating mandate led to the establishment of the TRIPS Agreement during the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade liberalization negotiations and the IPR provisions in the North American Free Trade Agreement. In the period since the 1988 Act, the IPR provisions of NAFTA and the TRIPS Agreement became the template for other bilateral or regional FTAs. The focus of IPR negotiating objectives shifted from creating to strengthening the IPR trade regime with the Trade Promotion Authority Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-210), under which several FTA negotiations were concluded by the George W. Bush Administration.

2002 Trade Promotion Authority

The IPR negotiating objectives in the 2002 TPA were highly significant to the future contours of U.S. FTA negotiations. The objective to negotiate trade agreements IPR terms that "reflect a standard of protection similar to that found in U.S. law" led to the negotiation of provisions that go beyond the level of protection provided in the WTO TRIPS Agreement. Often referred to as "TRIPS-plus" provisions, they include expanding IPR to new sectors, establishing more extensive standards of protection, and reducing the flexibility options available in TRIPS, such as with respect to compulsory licensing. Some of the new measures also address technological innovations that have come about since the TRIPS Agreement.

The objective to apply existing IPR protections to digital media reflected the changing nature of global commerce. The language sought to extend provisions for IPR protection to new and emerging technologies and methods of transmission and dissemination. The language also called for standards of enforcement to keep pace with technological change and allow right holders legal and technological protections for their works over the internet and other new media.

May 10, 2007 Bipartisan Trade Agreement

The May 10, 2007 Bipartisan Trade Agreement ("May 10 Agreement")—related to the then-pending FTAs with Colombia, Panama, Peru, and South Korea—established certain flexibilities for patent protections to promote further access to medicines in developing countries while maintaining a strong overall level of IPR protection.78 After the transfer of control of the House following the 2006 elections, some Members of the new Democratic majority sought certain changes in these pending U.S. FTAs. With respect to IPR, the congressional leadership sought to ensure that pending FTAs allowed developing country trading partners enough flexibility both to meet their IPR obligations and to promote access to life-saving medicines. A Bipartisan Trade Agreement between the Bush Administration and the House leadership, building on the 2002 TPA negotiating objectives, was reached on May 10, 2007.79 Following the Agreement, IPR language previously negotiated in the FTAs with Peru, Panama, and Colombia was modified to reflect its principles. The U.S.-South Korea FTA (KORUS) was not modified because the United States considers South Korea to be a developed country.

2015 Trade Promotion Authority

Congress passed the Bipartisan Comprehensive Trade Promotion and Accountability Act (P.L. 114-26) (TPA-2015) in June 2015, and President Obama signed the legislation on June 29, 2015. The IPR negotiating objectives include and expand on the 2002 objectives. The 2015 objectives recognize the importance of digital trade to the economy and seek provisions to prohibit cyber- and trade secret theft. The IPR objectives are considered principal negotiating objectives. This means that a procedural disapproval resolution could be introduced to strip FTA implementing legislation of expedited legislation procedures if the legislation fails "to make progress on the policies, priorities, and objectives of the Act."80 The objectives include

- Furthering adequate and effective protection of IPR through accelerated full implementation of the TRIPS Agreement and by ensuring FTAs negotiated by the United States "reflect a standard of [IPR] protection similar to that found in U.S. law";

- Protecting IPR related to new technologies and new methods of transmission and distribution in a manner that "facilitates legitimate trade";

- Eliminating discriminatory treatment in the use and enforcement of IPR;

- Ensuring adequate rights holder protection through digital rights management practices;

- Providing for strong enforcement of IPR;

- Negotiating the prevention and elimination of government involvement in violations of IPR such as cyber-theft or piracy;81 and

- Reaffirming the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, with additional language to "ensure that trade agreements foster innovation and access to medicine."82

Free Trade Agreements and Negotiations under the Trump Administration

In recent years, the United States increasingly has focused on free trade agreements (FTAs) as an instrument to promote stronger IPR regimes by foreign trading partners. IPR chapters in trade agreements include provisions on patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets, GIs, and enforcement. In general, the United States has viewed the TRIPS Agreement and WIPO-administered treaties as a minimum standard and has pursued higher IPR protection and enforcement levels through regional and bilateral FTAs. To date, the United States has entered into 14 FTAs with 20 countries.

United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)

|