Introduction

Approximately 27 million trips are taken on public transportation on an average day. Federal assistance to public transportation is provided primarily through the public transportation program administered by the Department of Transportation's (DOT's) Federal Transit Administration (FTA). The federal public transportation program was authorized from FY2016 through FY2020 as part of the Fixing America's Surface Transportation (FAST) Act (P.L. 114-94). This report discusses the major issues that may arise as Congress considers reauthorization.

In federal law, public transportation—also known as public transit, mass transit, and mass transportation—includes local buses, subways, commuter rail, light rail, paratransit (often service for the elderly and disabled using small buses and vans), and ferryboats, but excludes Amtrak, intercity buses, and school buses (49 U.S.C. §5302). About 48% of public transportation trips are made by bus, 38% by heavy rail (also called metro and subway), 5% by commuter rail, and 6% by light rail (including streetcars). Paratransit accounts for about 2% of all public transportation trips, and ferries about 1%.1

Public transportation accounts for about 3% of all daily transportation trips and about 7% of commute trips.2 Although ridership is heavily concentrated in a few large cities and their surrounding suburbs, especially the New York City metropolitan area, public transportation is provided in a wide range of places including small urban areas, rural areas, and Indian land.3

The Federal Public Transportation Program

Most federal funding for public transportation is authorized in multiyear surface transportation acts. The FAST Act authorized $61.1 billion for five fiscal years beginning in FY2016, an average of $12.2 billion per year. The authorization for FY2020 is $12.6 billion. Of the total five-year amount, 80% was authorized from the mass transit account of the Highway Trust Fund. Funding authorized from the Highway Trust Fund is provided as contract authority, a type of budget authority that may be obligated prior to an appropriation. The other 20% was authorized from the general fund of the U.S. Treasury as appropriated budget authority.4

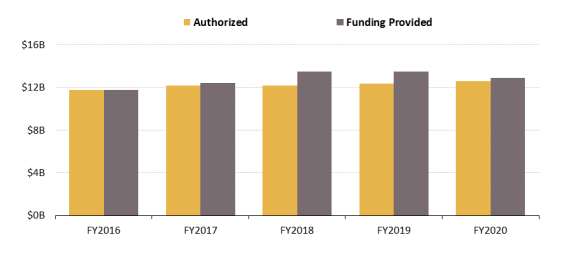

Funding for public transportation is sometimes provided under other authorities. The FY2018, FY2019, and FY2020 appropriations acts (P.L. 115-141, P.L. 116-6, P.L. 116-94), for example, provided additional general fund money for several programs that typically receive funding only from the Highway Trust Fund, thereby raising the general fund share of federal public transportation expenditures to about 28% in FY2018, 26% in FY2019, and 21% in FY2020. Funding for the Public Transportation Emergency Relief Program, which provides grants for emergency repairs following natural disasters or other emergencies, is typically from the general fund provided in supplemental appropriations acts.5 Transit projects can also be funded with money transferred (or "flexed") from federal highway programs by state and local officials. In FY2016, the last year for which data are available, $1.3 billion in highway funds was flexed to transit.6 Excluding flexed highway funds and emergency relief funding, funding provided in FY2017 through FY2020 was above the level authorized in the FAST Act (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Federal Public Transportation Program Funding FY2016-FY2020 |

|

|

Sources: Fixing America's Surface Transportation (FAST) Act (P.L. 114-94); Senate appropriations reports; Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141); Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6); Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94). Notes: Funding provided includes contract budget authority and appropriated budget authority; and excludes flexed federal highway funding and Public Transportation Emergency Relief Program funding. |

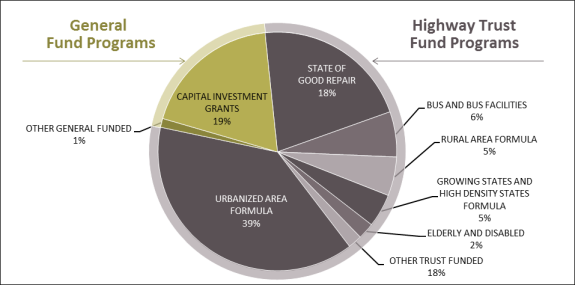

There are six major programs for public transportation authorized by the FAST Act: (1) Urbanized Area Formula; (2) State of Good Repair; (3) Capital Investment Grants (CIG) (also known as "New Starts"); (4) Rural Area Formula; (5) Bus and Bus Facilities; and (6) Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities. Typically, funding for all of these programs, except CIG, comes from the mass transit account of the Highway Trust Fund. CIG funding comes from the general fund. There are also a number of other much smaller programs (Figure 2).

Reauthorization Issues

Program Funding

The average of $12.2 billion per year authorized for the federal public transportation program in the FAST Act represented about a 14% increase (unadjusted for inflation) from the previous authorization, the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21; P.L. 112-141).7 The Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works reported a bill in August 2019 (S. 2302) that would reauthorize highway infrastructure programs through FY2025 with a 27% increase over the funding provided by the FAST Act.8 A similar increase in the annual authorization of public transportation funding would provide for federal expenditures of about $15.5 billion per year.

|

Figure 2. Federal Public Transportation Program Funding Shares Funding Authorized, FY2016-FY2020 |

|

|

Source: Federal Transit Administration, "FAST Act Program Totals," https://www.transit.dot.gov/funding/grants/fast-act-program-totals. |

A higher level of federal funding might improve the condition and performance of public transportation infrastructure. One indicator of the condition of public transportation infrastructure is the reinvestment backlog, which DOT defines as "an indication of the amount of near-term investment needed to replace assets that are past their expected useful lifetime."9 DOT estimated the reinvestment backlog to be $98 billion in 2014, about 13% of the total value of transit assets.10

In its biennial Conditions and Performance report, DOT projects how various future spending levels might affect the condition of public transportation infrastructure. The most recent report was published in November 2019 and used 2014 as the base year for projections. Capital expenditures on public transportation in 2014, DOT noted, totaled $17.7 billion from all sources, including federal, state, and local government support. Of this amount, $11.3 billion was spent on preserving the existing system and $6.4 billion on expansion. If this spending pattern were to continue over the 20 years between 2015 and 2034, DOT estimates, the investment backlog would grow to $116 billion (in 2014 inflation-adjusted dollars), an increase of 18%.11

DOT constructed two scenarios to estimate how much spending would be needed to eliminate the backlog and accommodate new riders. Under the assumption of low ridership growth, DOT estimated, $23.4 billion would be needed annually, an increase of about 32% (in 2014 inflation-adjusted dollars). In a scenario projecting high ridership growth, $25.6 billion would be needed annually, an increase of 45% (in 2014 inflation-adjusted dollars). DOT did not estimate the spending necessary if ridership is stagnant or dropping. However, it did estimate that $18.4 billion annually (adjusted for inflation) would eliminate the reinvestment backlog over 20 years if there was no spending on expansion.12

The focus of the federal public transportation program is on capital expenditures, but the program also supports operational expenses in some circumstances, as well as safety oversight, planning, and research. Greater federal support for transit operations could increase the quantity of transit service offered or reduce fares. In the past, particularly in the 1970s and early 1980s, such support caused the costs of providing service to increase, particularly through increases in wages and fringe benefits and by expanding services on routes with less demand.13 With greater flexibility to use federal funding for operating expenses, transit agencies could neglect maintenance and asset renewal, leading to a more rapid decline in the condition of capital assets. Existing flexibility to use capital funds for maintenance may help agencies preserve equipment and facilities.

DOT does not make any recommendations about the relative shares of public transportation funding that should be borne by federal, state, and local governments. The federal share of government spending on public transportation has been around 15% to 20% over the past 30 years.14 A higher level of funding by the federal government may not necessarily translate into more spending overall if transit providers substitute federal dollars for their own.

Highway Trust Fund Issues

The solvency of the Highway Trust Fund and its two accounts, the highway account and the mass transit account, is a major issue in reauthorization of funding for the public transportation program. Outlays from the mass transit account have outpaced receipts for over a decade, an imbalance the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects will continue in the future under current law. For the five-year period beginning in FY2021, CBO expects the gap between revenues and outlays to total $26 billion, an average of $5.2 billion annually (Table 1).15

The primary revenue source for the Highway Trust Fund is motor fuel taxes, which were last raised in 1993. Currently, of the 18.3 cents-per-gallon tax on gasoline and 24.3 cents-per-gallon tax on diesel that go to the Highway Trust Fund, 2.86 cents is deposited in the mass transit account. Congress has chosen to transfer general fund monies into the mass transit account to permit a higher level of spending than motor fuel tax revenues alone could sustain. These transfers have totaled $29 billion since they began in 2008. The FAST Act transferred $18.1 billion to the mass transit account from the general fund.

|

Fiscal Year |

Revenue |

Spending |

Difference |

|

2021 |

$6.3 |

$10.8 |

-$4.6 |

|

2022 |

$6.1 |

$11.2 |

-$5.0 |

|

2023 |

$6.1 |

$11.3 |

-$5.3 |

|

2024 |

$6.0 |

$11.5 |

-$5.5 |

|

2025 |

$6.0 |

$11.8 |

-$5.8 |

|

Five-year: FY2021-FY2025 total |

$30.5 |

$56.7 |

-$26.2 |

|

Five-year: FY2021-FY2025 average |

$6.1 |

$11.3 |

-$5.2 |

Source: Congressional Budget Office, "Highway Trust Fund Accounts—CBO's May 2019 Baseline," https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-05/51300-2019-05-highwaytrustfund_1.pdf.

Notes: Mass transit account revenue includes a projected $1 billion transferred annually from the highway account. Totals may not add due to rounding.

According to FTA, a balance of at least $1 billion in the mass transit account is required to ensure that the agency has sufficient funds to make mandated payments to transit agencies. CBO estimates that if Congress were to extend current law without providing for further transfers from the general fund to the mass transit account, the balance in the mass transit account would be about $300 million at the end of FY2021 and would reach zero at some point in FY2022.16 This would likely require FTA to slow payments to transit agencies. Outlays also outpace receipts in the highway account, but solvency problems are expected to arrive earlier in the mass transit account.

Bringing the receipts and outlays of the mass transit account into balance would involve a cut in program spending, an increase in revenues paid into the account, or a combination of the two. An increase in revenues could involve a commitment to regular transfers from the general fund. With the highway account facing similar problems, another possible change would be to redirect revenues from the mass transit account to the highway account and to fund the transit account with a general fund appropriation each year. This likely would make transit funding less certain, and it would not make up the entire shortfall in the highway account.

Financing

In addition to grants, the federal government supports public transportation infrastructure with direct loans and tax preferences for municipal bonds.17 Changes to two major federal loan programs relevant to public transportation—the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program and the Railroad Rehabilitation and Infrastructure Finance (RRIF) program—could be considered in reauthorization.

TIFIA provides long-term, low-interest loans and other types of credit assistance for the construction of surface transportation projects (23 U.S.C. §601 et seq.). Although the maximum federal share of project costs that may be provided by the TIFIA program was raised in MAP-21 from 33% to 49%, DOT has stated that it will provide more than 33% only in exceptional circumstances.18 To date, TIFIA has not covered more than 33% of the cost of any project. By limiting the TIFIA share in this way, DOT appears to be trying to maximize the leveraging of nonfederal resources, but it may be excluding projects that may not be financially viable without greater federal assistance. Public transportation projects typically cover a relatively small share of their costs from user fees, thus they usually need more government support than highway and bridge projects. Congress could direct DOT to consider a higher federal share in more circumstances or across the board.

Some project sponsors have stated that the lengthy process and upfront costs for obtaining TIFIA assistance led them not to seek TIFIA loans. The FAST Act required DOT to expedite projects thought to be lower-risk—those requesting $100 million or less in credit assistance with a dedicated revenue stream unrelated to project performance and standard loan terms—but this has apparently not had a significant effect: two projects have received TIFIA loans of less than $100 million since the passage of the FAST Act. Congress could make small TIFIA loans more attractive by changing a requirement that project sponsors obtain two credit ratings; at present, that requirement applies to TIFIA loans for projects with debt of $75 million or more. Less stringent requirements for credit ratings may increase the risk to the government of these loans.19 Reauthorization legislation also could incorporate various proposals that have been suggested to speed up approvals, such as requiring more frequent meetings of the DOT officials who make recommendations on project loans to the Secretary of Transportation (known as the Council on Credit and Finance), hiring additional staff to more quickly assess applications, and mandating that DOT regularly publish information about the time it takes loan applications to reach milestones.

The RRIF program was originally created to support freight railroads, particularly small freight railroads known as short lines, but loans are increasingly being made to commuter railroads.20 Legislative changes have made RRIF loans more attractive to commuter railroads. Recent changes also permit loans for transit-oriented development, that is economic development projects, including commercial and residential development, physically or functionally related to a passenger rail station. Several large loans have been made to transit agencies for commuter rail projects in the past few years, including $908 million to the Dallas Area Rapid Transit to finance a project from Dallas-Fort Worth Airport, $220 million to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority for positive train control (PTC), and almost $1 billion to the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority, also for PTC.

The federal government requires project sponsors to make a payment known as a credit risk premium to offset the risk of a default. No federal funding has been authorized to pay the credit risk premiums for RRIF borrowers, although $25 million was made available for this purpose in the 2018 appropriations act.21 To enhance the attractiveness of RRIF for public transportation projects, Congress could authorize a federal subsidy for the credit risk premium from the Highway Trust Fund. Alternatively, Congress could provide for the credit risk premium from the general fund directly or as part of another program. For example, the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94) makes RRIF credit risk premiums eligible for grants under the BUILD Transportation Discretionary Grants Program. Another RRIF-related proposal is to extend the authority to provide loans for transit-oriented development projects, which expires on September 30, 2020.22

Capital Investment Grants (CIG) Program

Because the CIG program receives funding from the general fund, not the Highway Trust Fund, appropriators have greater influence over its funding than they do over other transit programs. Nevertheless, the authorization sets a benchmark for the program's funding level, creates the program's overall structure, and can provide more or less discretion for FTA in the program's implementation. These characteristics could be more important in reauthorization than usual because of disagreements about the existence and operation of the program between Congress and the Trump Administration.

During the Obama Administration, FTA, among others, recommended significant increases in CIG funding to accommodate demand by project sponsors, especially because projects to expand the capacity of existing transit facilities, known as Core Capacity projects, were made eligible for funding beginning in FY2013. FTA noted in its FY2017 budget submission that the number of projects in the CIG "pipeline" had grown from 37 in FY2012 to 63 in FY2016.23 In addition, FTA asked Congress in its FY2017 budget request to increase annual CIG funding from the $2.3 billion authorized by the FAST Act to $3.5 billion, to accelerate projects to "not only potentially lower financing costs incurred on these projects, but also allow FTA to better manage the overall program given the ever growing demand for funds."24

For FY2018 and FY2019, the Trump Administration proposed that funding should be limited to projects with existing commitments from the federal government, and that CIG funding should be phased out. In its funding recommendation for FY2018, FTA noted that "future investments in new transit projects would be funded by the localities that use and benefit from these localized projects."25 House and Senate appropriators rejected this approach, directing FTA to continue working with project sponsors to develop projects, including issuing project evaluation ratings, and requiring the allocation of appropriations, with deadlines, to projects that have met the program requirements.26

With pressure for continued operation of the program, FTA has made several announcements of allocations of CIG funding to new projects. In July 2019, FTA stated that from the beginning of the Trump Administration in January 20, 2017, FTA had made CIG funding commitments to 25 new projects totaling $7.63 billion.27 It appears that FTA has dropped its call for phasing out the program; it recommended funding of $1.5 billion in FY2020, including $500 million for new projects.28 Congress agreed to nearly $2 billion for the program in the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94).

New York and New Jersey Gateway Program

The Gateway Program, which involves a set of projects in a 10-mile section of the Northeast Corridor (NEC) between Penn Station in Newark, NJ, and Penn Station in New York City, would be designed to improve intercity passenger rail service by Amtrak, which owns the underlying infrastructure, as well as commuter rail service provided by New Jersey (NJ) Transit. NJ Transit ridership in the corridor is approximately 50 million passenger trips per year, making this among the most heavily traveled public transportation routes in the country.29

The project sponsors—the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, in cooperation with the Gateway Program Development Corporation, New Jersey Transit Corporation, and Amtrak—have proposed $7 billion in CIG program funding for the costliest Gateway Program project to date. The $14 billion project is for the construction of a new tunnel under the Hudson River, the restoration of the current tunnel that was damaged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, and the preservation of the Hudson Yards right-of-way linking the proposed new tunnel with Pennsylvania Station in New York City. In addition, the project sponsors propose to borrow several billion dollars for tunnel construction from the federal government through the RRIF program. NJ Transit, the lead sponsor of the $1.6 billion Portal North Bridge project across the Hackensack River in New Jersey, has proposed a CIG grant to cover about half the cost.30 The Gateway Program overall is estimated to cost about $30 billion.31

The federal amount sought for the Gateway Program is equal to several years of funding for CIG, at recent funding levels, and could potentially overwhelm a program that is responsible for aiding projects throughout the country. The largest CIG grant since FY2007 is $2.6 billion. FTA typically pays out such grants in smaller amounts over a prolonged construction period; single-year allocations of funding for individual projects have rarely exceeded $200 million.

The proposed use of federal loans in conjunction with federal grants for the Gateway Program is also controversial.32 The statute governing TIFIA (23 U.S.C. §603(b)(8)) states that proceeds from a TIFIA loan "may" be used as a nonfederal share of project costs if the loan will be repaid from nonfederal funds. The Trump Administration has been critical of CIG project sponsors using both federal grants and loans on public transportation projects. In June 2018, FTA circulated a letter stating the following:

given the competitive nature of this discretionary program, the [CIG] statute specifically urges FTA to consider the extent to which the project has a local financial commitment that exceeds the required non-government share of the cost of the project. To this end, FTA considers U.S. Department of Transportation loans in the context of all Federal funding sources requested by the project sponsor when completing the CIG evaluation process, and not as separate from the Federal funding sources.33

The appropriations committees have taken action to prevent this policy from being implemented. For instance, Section 165 of Division G of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), states that "none of the funds made available under this Act may be used for the implementation or furtherance of new policies detailed in the 'Dear Colleague' letter distributed by the Federal Transit Administration to capital investment grant program project sponsors on June 29, 2018." In a potential reauthorization, Congress could seek to eliminate permanently DOT's discretion to block project sponsors from combining CIG grants and TIFIA loans on a single project. Bills pending in the House, H.R. 731 and H.R. 1849, would allow recipients of TIFIA and RRIF support to elect to have the loans treated as nonfederal funds.

Expediting CIG Projects

Applying for CIG funding requires the development of extensive data and the preparation of many detailed reports and other documents, all of which are reviewed by FTA in making project approval determinations. Legislative changes in MAP-21 and the FAST Act sought to simplify the process. For example, MAP-21 reduced the number of separate FTA approvals for more expensive projects from four to three, and for less expensive projects from three to two. The less expensive projects, known as small starts projects, are those that cost $300 million or less to build and require $100 million or less of CIG funding. Moreover, MAP-21 authorized the use of project justification warrants in certain cases "that allow a proposed project to automatically receive a satisfactory rating on a given criterion based on the project's characteristics or the characteristics of the project corridor." 34 The FAST Act created an Expedited Project Delivery for Capital Investment Grants Pilot Program to more quickly review up to eight projects involving public-private partnerships in which the federal grant is 25% or less of the project cost. The federal share of a CIG project is typically about 50%.

There have been no comprehensive evaluations of whether these changes have resulted in projects progressing more quickly through the CIG pipeline. However, there are options that could be considered to further speed CIG projects. For instance, the threshold for projects to qualify as small starts could be increased, and the use of warrants could be permitted in more circumstances. FTA has been slow to implement the Expedited Project Delivery for Capital Investment Grants Pilot Program.35 Increasing the permitted maximum federal share of project costs under the pilot program, currently 25%, might make the program more attractive to transit agencies.

Falling Public Transportation Ridership

According to data from the American Public Transportation Association (APTA), annual transit ridership reached a modern-era high of 10.7 billion trips in 2014. Since then, it has fallen by almost 8% to 9.9 billion trips in 2018.36 National trends in public transportation ridership are not necessarily reflected at the local level; thus, different areas may have different reasons for growth or decline. But at the national level, the two factors that most affect public transportation ridership are competitive factors and the supply of transit service. Several competitive factors, notably increased car ownership, the relatively low price of gasoline over the past few years, and the growing popularity of bikeshare, scooters, and ridesourcing services such as Lyft and Uber, appear to have reduced transit ridership. The amount of transit service supplied has generally grown over time, along with government investment, but average fares have risen faster than inflation, possibly deterring riders.

The future of public transportation ridership in the short to medium term is likely to depend on population growth, the public funding commitment to supplying transit, and factors that make driving more or less attractive, such as the price of parking, the extent of highway congestion, and the implementation of fuel taxes, tolls, and mileage-based user fees.

Under current law, federal grants to transit agencies are based mainly on population, population density, and the amount of service provided. Congress could address the issue of declining ridership by tying the allocation of federal formula funds to agencies' success in boosting ridership or fare revenue.

Over the long term, the introduction of fully autonomous vehicles could reduce transit ridership, unless restrictions or fees make them an expensive alternative. However, there is significant uncertainty about when, or whether, fully autonomous vehicles will affect ridership. Given this uncertainty, federal capital funding might focus on buses, which last about 10 years, and not new rail systems that take many years to build and will remain in service for decades. Another option would be to redirect CIG funding from building new rail systems and lines to refurbishing rail transit in the large and dense cities where rail transit currently carries large numbers of riders.

The emergence of new mobility options may have reduced transit ridership, but it also may present an opportunity for transit agencies to provide new services to improve customer mobility. FTA has funded some pilot projects through the Research, Development, Demonstration, and Deployment program. An option in reauthorization would be to fund a program that focuses on boosting transit ridership through mobility and technological innovations.37

Climate Change

Surface transportation is a major source of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, the main human-related greenhouse gas (GHG) contributing to climate change. At the same time, the effects of climate change on environmental conditions, such as extreme heat and global sea level rise, pose a threat to transportation infrastructure. Surface transportation reauthorization may seek to address environmental conditions with mitigation provisions that aim to reduce GHG emissions from surface transportation and adaptation provisions that aim to make the surface transportation system more resilient. S. 2302, the reauthorization bill reported by the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works in August 2019, included provisions that address climate change.38

GHG emissions from the transportation sector come mainly from passenger cars and light trucks. Public transportation might contribute to a reduction of GHG emissions if trips made in personal vehicles, particularly single-occupant trips, are made by trains and buses instead. The efficiency of public transportation in terms of GHG emissions depends, in part, on the amount of ridership in relation to the amount of transit supplied. GHG emissions from public transportation are also dependent on the sources of fuel used to power trains and buses, including the way in which electricity is generated.39

Specific policy options that might be considered to reduce GHG gases from public transportation vehicles could include funding for alternatives to diesel-powered buses, particularly electric buses using electricity generated from renewable sources. This could include a higher level of funding for the Low or No Emission Vehicle (Lo-No) Program.40 In the FAST Act, the discretionary Lo-No Program was funded as a $55 million annual set-aside from the Bus and Bus Facilities Program. Another possibility would be to require buses purchased using federal funds to have low or no emissions.41 Electric buses cost more to purchase than traditional diesel-powered buses, although the lifecycle cost is comparable. To overcome this, the federal government could offer low-interest or no-interest loans for the nonfederal share of the cost of buying electric buses.42

Adaptation is action to reduce the vulnerabilities and increase the resilience of the transportation system to the effects of climate change. Although much of the funding administered by FTA can be used to assess the potential impacts of climate change on public transportation infrastructure and to apply adaptation strategies, there is currently no dedicated surface transportation funding for adaptation projects. Reauthorization could create a new grant program dedicated to adaptation planning and projects or require that funds from other programs be set aside for such purposes.

Emergency Relief Program

The Public Transportation Emergency Relief (ER) Program (49 U.S.C. §5324; 49 C.F.R. §602) provides federal funding on a reimbursement basis to states, territories, local government authorities, Indian tribes, and public transportation agencies for damage to public transportation facilities or operations as a result of a natural disaster or other emergency and to protect assets from future damage, so-called resilience projects.

FTA's ER program does not have a permanent annual authorization. Rather, all funds are authorized on a "such sums as necessary" basis and require an appropriation from the Treasury's general fund. Because of this, FTA cannot provide funding immediately after a disaster or emergency is declared. Transit agencies, therefore, typically rely on the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to fund immediate needs beyond the capacity of state and local government. This could slow the response of transit agencies and blur the lines of responsibility between FTA and FEMA if funds are later appropriated for the ER program. Adding a quick-release mechanism to FTA's ER program would allow FTA funds to be approved and distributed within a few days of a disaster. Such a program already exists for the Federal Highway Administration, with an annual authorization of funds from the Highway Trust Fund, and FTA's program could similarly be authorized an amount from the mass transit account of the fund. Such an authorization, however, would place a new claim on resources of the mass transit account.

The FTA's ER program does not have a limit on the amount that can be spent on resilience projects. Although this may allow for better projects, it can result in Congress appropriating larger amounts than might otherwise be necessary, and it could also be a way for transit agencies to fund betterments and new facilities that have little direct connection to the goals of repairing damages and making the transit systems resilient to future natural hazards. A separate resilience program and changes to the ER program may be a more effective way to protect public transportation infrastructure from future disasters.

Public Transportation Safety

Public transportation is a relatively safe mode of passenger transportation compared with traveling by car and light truck. The fatality rate per passenger mile for cars and light trucks is about double that of transit buses and five times that of heavy rail. While the fatality rate per passenger mile for commuter rail is more comparable with cars and light trucks, most commuter rail fatalities are nonusers, such as trespassing pedestrians and those in vehicles struck at grade crossings.43

The federal government's role in public transportation safety has been expanded significantly since 2008. One of the major changes was the requirement in the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-432) for commuter railroads, along with Amtrak and freight railroads, to install positive train control (PTC), systems that use signals and sensors to monitor and control railroad operations.

The federal requirement for PTC resulted in significant capital costs for commuter rail agencies, of which about 10% has been borne by the federal discretionary and formula funds.44 In addition to the initial costs of installing PTC, commuter rail agencies claim that there will be ongoing costs associated with PTC estimated to be about $160 million per year.45 Consequently, PTC implementation may have a detrimental effect on the overall financial condition of commuter rail agencies, and, without more funding from federal, state, or local government, may have a detrimental effect on the condition of commuter rail assets. Commuter rail agencies have proposed the creation of a new federal PTC funding program that could pay some or all of these ongoing costs.46 Separately, proposals have been advanced to dedicate federal funding for commuter railroads to improve the safety of highway-rail grade crossings.

Buy America

With the aim of protecting American manufacturing and manufacturing jobs, Buy America laws place domestic content restrictions on federally funded transportation projects.47 Buy America requirements vary according to the specific DOT funding program and administering agency. For projects funded by FTA there is a 100% U.S.-made requirement for iron, steel, and manufactured goods. However, Buy America does not apply to rolling stock if more than 70% of components, by value, are produced domestically and final assembly is in the United States. An addition to Buy America law in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (P.L. 116-92, §7613) prohibits transit agencies purchasing railcars and buses from certain government-owned, -controlled or -subsidized companies, such as the China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation and BYD, even if they are otherwise Buy America-compliant.

Waivers of Buy America requirements can be provided by DOT agencies under certain circumstances, but these can be difficult and time-consuming to obtain. To speed up the waiver process, Congress could require that a waiver decision be made within a specific number of days. Each DOT agency has its own Buy America requirements, creating complications when a project involves funding from more than one of the agencies. Congress might seek to standardize Buy America requirements across the department. Other proposals have been to make Buy America requirements more stringent. For example, the Buy America 2.0 Act (H.R. 2755, 116th Congress) would increase the share of public transit rolling stock components and subcomponents that must be produced in the United States by five percentage points annually beginning in FY2021, reaching 100% by FY2026. Such measures may make it more costly and time-consuming for transit agencies to procure vehicles.