Introduction

The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP; previously the Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program) provides federally purchased commodities and a smaller amount of cash support to food banks, food pantries, soup kitchens, shelters, and other types of emergency feeding organizations serving low-income households and individuals.1 Commodities include fruits, vegetables, meats, and grains, among other foods. In addition to serving needy individuals, TEFAP's domestic commodity purchases support the agricultural economy by reducing supply on the market, thereby increasing food prices. TEFAP is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS).

TEFAP was established under the Emergency Food Assistance Act of 1983 in an effort to dispose of government-held agricultural surpluses and alleviate hunger in the wake of a recession and declining food stamp benefits.2 Since then, TEFAP has evolved into a permanent program with mandatory, annually appropriated funding that operates in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and four U.S. territories.3 The program was most recently reauthorized by the 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334).

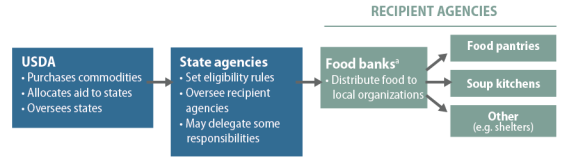

At the federal level, TEFAP is administered by USDA-FNS in collaboration with USDA's purchasing agencies: the Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) and Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). At the state level, TEFAP is administered by a state distributing agency designated by the governor or state legislature; generally, they are state departments of health and human services, agriculture, or education. Federal commodities and funds may flow through the state or directly to feeding organizations (called recipient agencies) based on how the state structures the program.4 States will often task food banks with processing and distributing food to local feeding organizations. Food banks typically operate regional warehouses and distribute food to other organizations rather than to households directly.5 Figure 1 depicts the flow of commodities and funds through TEFAP.

|

|

Source: Adapted from USDA-FNS, White Paper on the Emergency Food Assistance Program, 2013. a. States may distribute food to recipient agencies directly or task recipient agencies with food distribution to other recipient agencies. States often delegate this responsibility to food banks. |

TEFAP is part of a larger web of food assistance programs.6 Some of these programs provide cash assistance while others primarily distribute food. TEFAP foods may reach individuals who do not qualify for other food assistance programs or supplement the assistance that individuals receive through other programs. With more than $400 million in appropriated funding in FY2020, TEFAP is the largest source of federal support for emergency feeding organizations. Other related federal programs include the Federal Emergency Management Agency's (FEMA's) Emergency Food and Shelter Program, funded at $125 million in FY2020, which, among its other services for homeless individuals, provides food through shelters, food banks, and food pantries.7 In addition, USDA's Commodity Supplemental Food Program, funded at $245 million in FY2020, distributes monthly food packages to low-income elderly individuals through local organizations, which can include food banks and pantries.8

This report begins by describing the population using emergency food assistance. It goes on to discuss the TEFAP program, including its administration at the federal, state, and local levels, eligibility rules, and funding structure. The report concludes by summarizing TEFAP's role in disaster response and recent reauthorization efforts. Appendix A lists TEFAP expenditures from the program's inception in 1983 to present; Appendix B provides a brief legislative history of TEFAP; and Appendix C lists TEFAP funding by state.

|

Definitions Emergency feeding organizations (EFOs): "The term 'emergency feeding organization' means a public or nonprofit organization that administers activities and projects (including the activities and projects of a charitable institution, a food bank, a food pantry, a hunger relief center, a soup kitchen, or a similar public or private nonprofit eligible recipient agency) providing nutrition assistance to relieve situations of emergency and distress through the provision of food to needy persons, including low-income and unemployed persons." Common types of EFOs:

Source: Section 201A of the Emergency Food Assistance Act (7 U.S.C. 7501) |

The Demand for Emergency Food Assistance

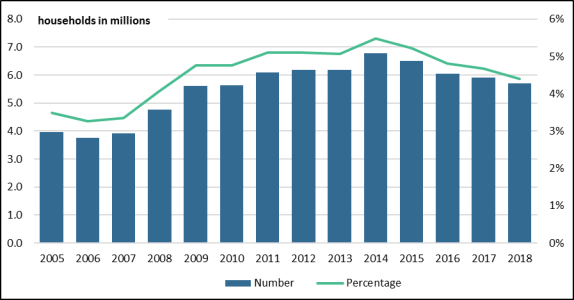

According to an analysis of Current Population Survey (CPS) data by USDA's Economic Research Service (ERS), an estimated 5.7 million households (4.4%) utilized food pantries (see Figure 2) and at least 657,000 households (0.5%) utilized soup kitchens in 2018.9 However, this is likely an underestimate of the population using emergency food assistance because the sample did not include certain households with incomes over 185% of the poverty guidelines and the CPS does not fully capture households who are homeless or in tenuous housing arrangements. For comparison, a survey by Feeding America, a nonprofit membership and advocacy organization, estimated that approximately 15.5 million households accessed its network of feeding organizations in 2013 (the same year, ERS estimated that 6.9 million households used food pantries and soup kitchens). The Feeding America network represents a large segment of emergency feeding organizations nationwide.10

Data on the number of TEFAP recipients specifically are not available, in part because TEFAP commodities are mixed in with other commodities provided by emergency feeding organizations and because of "the transient nature of participation."11

|

Figure 2. Number of Households Using Food Pantries, 2005-2018 And as a percentage of households nationwide |

|

|

Source: CRS graphic based on data contained in statistical supplements to Household Food Security in the United States, USDA Economic Research Service, for 2005-2018. Notes: This represents the number of households who reported that they received emergency food from a food pantry, food bank, or church in the last 12 months. This may be an underestimate of the number of households using food pantries due to the fact that the Census's Current Population Survey (CPS) Food Security Supplement focuses on households with incomes under 185% of the poverty guidelines and excludes homeless individuals and underrepresents those in tenuous housing arrangements. See Statistical Supplement to Household Food Security in the United States in 2018, p. 21, https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=94869. |

Characteristics of Emergency Food Recipients

Food insecurity is common among households using emergency feeding organizations.12 According to the ERS analysis, 65.7% of households using food pantries and soup kitchens were food insecure in 2018, meaning that they had difficulty providing enough food for all of their members at times during the year due to a lack of resources.13 Roughly half of these households experienced very low food security, meaning that the food intake of some household members was reduced and normal eating patterns were disrupted due to limited resources. Nationally, the percentage of households experiencing food insecurity was 11.1% in 2018, down from a recent high of 14.9% in 2011.14

According to the ERS analysis, in 2018 households using food pantries were more likely to have incomes below 185% of poverty compared to the general population (67% vs. 21%) and to include children (36% vs. 29%).15 Meanwhile, according to the 2014 Feeding America survey, individuals using meal programs (e.g., soup kitchens and shelters) were generally single-person households and were more likely to be homeless. In 2013, just over 70% of households using the Feeding America network of meal programs had a single member and nearly 34% were homeless or living in temporary housing.16

In addition, emergency feeding organizations may act as a safety net for food insecure households who are ineligible for or do not participate in other federal food assistance programs. For example, in the case of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), households may have an income too high to qualify for assistance but still experience difficulty purchasing food, or they may fail to meet other program eligibility rules.17 Among households using feeding organizations affiliated with Feeding America's network, a little more than half (55%) reported receiving SNAP benefits in 2013.18

Program Administration

Federal Role

TEFAP is administered by USDA's Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), which is responsible for allocating aid to states (see "State Allocation Formula") and coordinating the ordering, processing, and distribution of commodities. Specifically, FNS receives requests for certain quantities and types of commodities from state agencies, which place orders based on their entitlement allocation and in consultation with recipient agencies.19 FNS then collaborates closely with USDA's purchasing agencies—the Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) and Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC)—to fulfill the orders.20 FNS also collaborates with AMS and CCC to purchase bonus commodities throughout the year that are not based on state requests but rather USDA's discretion to support different crops. Commodities are delivered to state distribution points, which may be operated by a state agency, private contractor, or recipient agency.21 According to a 50-state survey conducted by the Washington State Department of Agriculture in 2015, most states reported that commodities were sent to nonprofit-run warehouses (i.e., food banks).22

FNS also issues regulations and guidance and provides general oversight of states' TEFAP operations. FNS provides oversight by reviewing and approving state TEFAP plans, which are documents that outline each state's operation of TEFAP. States are required to submit amendments to the plan for approval "when necessary to reflect any changes in program operations or administration as described in the plan, or at the request of FNS, to the appropriate FNS Regional Office."23

State Role

TEFAP is administered at the state level by an agency designated by the governor "or other appropriate State executive authority" that enters into an agreement with FNS.24 As of 2015, states most commonly housed TEFAP in a health and human services department (19 states), agriculture department (14 states), or education department (8 states).25 State agencies administering TEFAP are responsible for creating eligibility criteria (see "Eligibility Rules for Individuals and Households"), selecting recipient agencies, distributing commodities and funds to recipient agencies, and overseeing recipient agencies. States also maintain state TEFAP plans, which contain program and eligibility rules.26

Federal regulations allow states to delegate a number of responsibilities to recipient agencies, if desired. States can (and often do) delegate the responsibility of warehousing and transporting commodities to one or more eligible recipient agencies, most often to food banks.27 They also frequently delegate the role of selecting and contracting with other recipient agencies; for example, enabling a food bank to contract with multiple food pantries.28 States cannot delegate their responsibility to set eligibility rules or oversee recipient agencies.29

States must review at least 25% of recipient agencies contracting directly with the state (e.g., food banks) at least once every four years, and at least one-tenth or 20 (whichever is fewer) of other recipient agencies each year.30 If the state finds deficiencies in the course of review, the state agency must submit a report with the findings to the recipient agency and ensure that corrective action is taken.

Local Role

Organizations that are eligible for TEFAP aid are referred to as recipient agencies in the Emergency Food Assistance Act. According to the statute, recipient agencies are public or nonprofit organizations that administer

- emergency feeding organizations;

- charitable institutions;

- summer camps or child nutrition programs;

- nutrition projects operating under the Older Americans Act of 1965; or

- disaster relief programs.31

The first category of organizations—emergency feeding organizations—receive priority under TEFAP statute and regulations and also receive the majority of TEFAP aid.32 Emergency feeding organizations are defined as public or nonprofit organizations "providing nutrition assistance to relieve situations of emergency and distress through the provision of food to needy persons, including low-income and unemployed persons."33 They include food banks, food pantries, soup kitchens, and other organizations serving similar functions.

Recipient agencies are responsible for serving and distributing TEFAP foods to individuals and households. As discussed above, they may also have additional responsibilities as delegated by the state agency; for example, food banks, which operate food warehouses, may be tasked with distributing food to subcontracting recipient agencies like food pantries and soup kitchens, which in turn distribute foods or serve prepared meals to low-income individuals and families.

In addition, recipient agencies must adhere to program rules. For example, they must safely store food and comply with state and/or local food safety and health inspection requirements.34 Recipient agencies must also maintain records of the commodities they receive and a list of households receiving TEFAP foods for home consumption.35 There are also restrictions on the types of activities that can occur at distribution sites. Recipient agencies must ensure that any unrelated activities are conducted in a way that makes clear that the activity is not part of TEFAP and that receipt of TEFAP foods is not contingent on participation in the activity.36 Activities may not disrupt food distribution or meal service and may not be explicitly religious.37 In addition, recipient agencies may not engage in recruitment activities designed to persuade an individual to apply for SNAP benefits.38

|

Characteristics of Emergency Feeding Organizations The most recent nationally representative survey of emergency feeding organizations was conducted in 2000 by USDA's Economic Research Service (ERS).39 ERS found that there were approximately 400 food banks, 32,700 food pantries and 5,300 soup kitchens in the United States in 2000.40 These organizations were reliant on both private and public donations, including TEFAP support. According to the survey, TEFAP foods comprised 14% of foods distributed by the emergency food assistance system and TEFAP administrative funds comprised 12% to 27% of organizations' operating costs in 2000.41 However, this proportion may fluctuate from year to year. More recently, Feeding America reported that TEFAP foods made up 17% of the foods distributed by their network of approximately 200 food banks in FY2017.42 Most food banks in the ERS survey were secular, nonprofit organizations, while the majority of food pantries and soup kitchens were nonprofit organizations associated with a religious group.43 Food banks were likely to be affiliated with a national organization, including Feeding America (previously Second Harvest), United Way, Foodchain, Salvation Army, the Red Cross, and Catholic Charities.44 All types of emergency feeding organizations were dependent on volunteers.45 |

Eligibility Rules for Individuals and Households

Under broad federal guidelines, states set eligibility rules for individuals and households participating in TEFAP. Eligibility rules differ for organizations distributing commodities directly to households (e.g., food pantries) and organizations providing prepared meals (e.g., soup kitchens). States must develop income-based standards for households receiving foods directly, but cannot set such standards for individuals receiving prepared meals. However, organizations serving prepared meals must serve predominantly needy persons, and states "may establish a higher standard than 'predominantly' and may determine whether organizations meet the applicable standard by considering socioeconomic data of the area in which the organization is located, or from which it draws its clientele."46

Income eligibility rules for households receiving TEFAP foods directly vary by state. Many states limit income eligibility to household incomes at or below 185% of the poverty guidelines.47 Some states also confer household eligibility based on participation in other federal and state programs (known as categorical eligibility).48

States may also create other eligibility rules for households' receipt of TEFAP foods, such as requiring identification or proof of residency within the state.49 However, according to federal regulations, length of residency cannot be a criterion.50

Funding and Appropriations

Federal assistance through TEFAP is primarily provided in the form of USDA-purchased domestic agricultural commodities (USDA Foods). A smaller amount of assistance is provided in the form of cash support for administrative and distribution costs.

There are two types of TEFAP commodities: entitlement commodities and bonus commodities. Entitlement commodities are appropriated entitlements, meaning that the authorizing law sets the level of spending but an annual appropriation is needed to provide funding.51 Funding for bonus commodities is not included in the TEFAP appropriation and is instead provided by separate USDA budget authority. These funds are used by USDA for bonus commodity purchases for the program throughout the year. TEFAP's administrative funds are discretionary spending, requiring an annual appropriation.

In FY2020, the enacted appropriation provided $322.3 million for entitlement commodities and $79.6 million for administrative costs.52 Appropriations for TEFAP's entitlement commodities were contained in the SNAP account and appropriations for administrative costs were contained in the Commodity Assistance Program (CAP) account. In FY2018 (the most recent year with complete data), USDA purchased and distributed $308.9 million in bonus commodities for TEFAP.53 Bonus commodities are projected to increase in FY2019 as a result of the Administration's trade aid package (discussed below).

|

TEFAP's Authorizing Laws The Emergency Food Assistance Act of 1983: governs TEFAP operations and authorizes mandatory funding for administrative costs (7 U.S.C. 7501-7516) The Food and Nutrition Act of 2008 (previously the Food Stamp Act): Section 27 authorizes mandatory funding for TEFAP commodities (7 U.S.C. 2036) |

Commodity Food Support

Entitlement Commodities

Mandatory funding for TEFAP commodities is authorized by Section 27 of the Food and Nutrition Act (7 U.S.C. 2036). The act authorizes $250 million annually plus additional amounts each year in FY2019 through FY2023 as a result of amendments made by the 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334). In FY2019, the additional amount was $23 million; for each of FY2020-FY2023, the additional amount is $35 million. Both the base funding of $250 million and the additional amounts are adjusted for food price inflation.54 Based on this statutory criteria, the FY2020 appropriation provided $322.3 million for TEFAP's entitlement commodities (contained in the SNAP account) (see Table 1).55

Appropriations occasionally provide additional discretionary funding for commodities beyond the levels set in the Food and Nutrition Act. Most recently, $19 million was appropriated through a general provision in FY2017.

Historically, appropriations laws have allowed states to convert a portion of their funds for entitlement commodities into administrative funds. In past years, states were allowed to convert 10% of funds; FY2018 and FY2019 appropriations increased the proportion to 15%; and the FY2020 appropriation increased the proportion to 20%. States generally exercise this option; for example, in FY2018 states converted $25.9 million out of a possible $43.1 million in eligible funds.56 States are also allowed to carry over entitlement commodity funds into the next fiscal year.57

Bonus Commodities

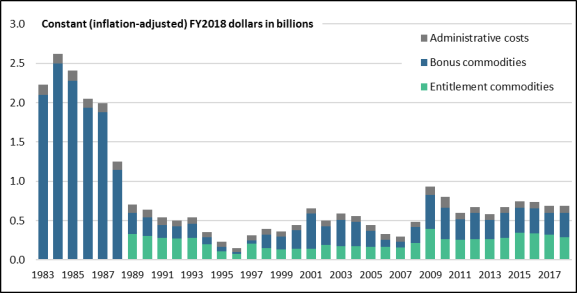

Bonus commodities are purchased at USDA's discretion throughout the year using separate (non-TEFAP) USDA budget authority for that purpose. USDA's purchases of bonus commodities are based on agricultural surpluses or other economic problems, as raised by farm and industry organizations or USDA's own commodity experts. The amount and type of bonus commodities that USDA purchases for TEFAP fluctuates from year to year, and depends largely on agricultural market conditions. In FY2018, USDA purchased $308.9 million in bonus commodities for TEFAP. The level of bonus commodities has fluctuated substantially over time (see Figure 3).

USDA's 2018 and 2019 Trade Aid Packages

In 2018 and 2019, the Trump Administration announced two trade aid packages aimed at assisting farmers impacted by retaliatory tariffs.58 USDA's 2018 trade aid package, announced in August 2018, included $1.2 billion in purchases of bonus commodities for distribution to TEFAP and other domestic food assistance programs.59 USDA's 2019 trade aid package, announced in May 2019, provided another $1.4 billion for such purposes.60 Trade aid purchases resulted in an influx of bonus commodities in TEFAP in FY2019 that will likely continue into FY2020.

USDA's Purchasing Authorities: Section 32 and the Commodity Credit Corporation

USDA's purchases of bonus commodities stem from two accounts: Section 32 and the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC).61

Section 32 of the Act of August 24, 1935, is a permanent appropriation that sets aside the equivalent of 30% of annual customs receipts to support the farm sector through the purchase of surplus commodities and a variety of other activities.62 The Section 32 appropriation has totaled nearly $10 billion annually in recent years, a small portion of which goes toward TEFAP commodities.63 USDA's Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) makes Section 32 purchases.

The CCC is a government-owned entity that finances authorized programs that support U.S. agriculture. Its operations are supported by USDA's Farm Service Agency. The CCC has permanent, indefinite authority to borrow up to $30 billion from the U.S. Treasury to finance its programs.64

Prior to the trade aid purchases, Section 32 has historically financed TEFAP commodities to a greater extent than the Commodity Credit Corporation.65 Unlike CCC support, which is normally limited to price-supported commodities (such as milk, grains, and sugar), Section 32 is less constrained in the types of commodities that may be provided, and can include meats, poultry, fruits, vegetables, and seafood.

Within USDA, the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) works closely with AMS and the CCC to determine what purchases are made for TEFAP. FNS also solicits input from state and local agencies. According to TEFAP's authorization of appropriations in the Food and Nutrition Act, USDA must, "to the extent practicable and appropriate, make purchases based on (1) agricultural market conditions; (2) preferences and needs of States and distributing agencies; and (3) preferences of recipients."66

Types of Foods

USDA-purchased agricultural products (USDA Foods) in TEFAP include a variety of products, such as meats, eggs, vegetables, soup, beans, nuts, peanut butter, cereal, pasta, milk, and juice.67 Most foods are nonperishable and ready for distribution when delivered to states, although some foods, such as some meat and dairy products, require refrigeration.68 States and recipient agencies can request entitlement commodities from a list of USDA Foods. USDA selects bonus foods based on market conditions.69 In FY2018, bonus food purchases included "beans, blueberries, catfish, cheese, cherries, chicken, ground beef, lentils, milk, mixed fruit, peaches, plums, pork chops, raspberries, strawberries, tomato sauce, and turkey."70

According to a 2012 USDA study, TEFAP foods are relatively nutritious compared to foods in the average American diet.71 The study found that TEFAP entitlement and bonus foods delivered to states in FY2009 scored 88.9 points out of a possible 100 points on the Healthy Eating Index—a measure of compliance with federal dietary guidelines—compared to 57.5 points scored by the average American diet.72 Keeping in mind that TEFAP foods are generally meant to supplement diets, the study also found that these foods would supply 81% of fruits, 69% of vegetables, 98% of grains, 171% of protein, 36% of dairy, 84% of oils, and 39% of the maximum solid fats and added sugars recommended for a 2,000-calorie diet.73

Administrative Cash Support

TEFAP provides funds to cover state and recipient agency costs related to processing, storing, transporting, and distributing USDA-purchased commodities, as well as administrative costs related to determining eligibility, training staff, recordkeeping, and publishing announcements.74 Administrative funds can also be used to support states' food recovery efforts.75

The Emergency Food Assistance Act of 1983 authorizes $100 million to be appropriated annually for administrative costs.76 In FY2020, appropriations provided $79.6 million in discretionary funding for TEFAP administrative funds. The administrative fund appropriation was higher in FY2019 and FY2020 compared to prior years (see Table 1).77 The Emergency Food Assistance Act of 1983 also authorizes up to $15 million to be appropriated for TEFAP infrastructure grants (and this authority was extended by the 2018 farm bill); however, funds have not been appropriated for these grants since FY2010.78

The statute specifies that administrative funds must be made available to states, which must in turn distribute at least 40% of the funds to emergency feeding organizations.79 However, states are required to match whatever administrative funds they keep. As a result, states typically send nearly all of these funds to emergency feeding organizations.80

States can convert any amount of their administrative funds to food funds, but this happens to a lesser extent than the conversion of food funds to administrative funds. In FY2018, states converted only $64,214 of administrative funds to food funds.81

|

Appropriations |

Purchases |

||

|

Fiscal Year |

Administrative Funds |

Entitlement Commodities |

Bonus Commodities |

|

2008 |

49.7 |

190.0 |

178.1 |

|

2009a |

49.5 |

250.0 |

373.7 |

|

2010a |

49.5 |

308.0 |

346.6 |

|

2011 |

49.4 |

247.5 |

235.3 |

|

2012 |

48.0 |

260.3 |

304.2 |

|

2013b |

49.4 |

265.8 |

228.5 |

|

2014 |

49.4 |

268.8 |

298.8 |

|

2015 |

49.4 |

327.0 |

302.9 |

|

2016 |

54.4 |

318.0 |

305.5 |

|

2017 |

59.4 |

316.0 |

268.6 |

|

2018 |

64.4 |

289.5 |

308.9 |

|

2019c |

109.6 |

294.5 |

Not avail. |

|

2020 |

79.6 |

322.3 |

Not avail. |

Source: FY008-FY2019 data from congressional budget justifications for FY2010-FY2020; FY2020 appropriations from the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94) and accompanying explanatory statement.

Notes: Appropriations displayed are prior to any conversions of entitlement commodity funds into administrative funds. Table does not include TEFAP infrastructure grant appropriations (most recently, $6 million was appropriated in FY2010).

a. Note that the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) provided an additional $150 million in funding for TEFAP entitlement commodities and administrative costs in FY2009 and FY2010 (not reflected in table).

b. Table does not include a supplemental appropriation of $5.7 million for TEFAP disaster assistance in FY2013.

c. The FY2019 administrative fund appropriation includes $30.0 million in a transfer of Commodity Supplemental Food program prior-year funds.

Funding Trends

Figure 3 displays TEFAP's expenditures on administrative costs, entitlement commodities, and bonus commodities from the program's inception (FY1983) to FY2018 (see Appendix A for specific dollar amounts). Originally, bonus foods were the only type of commodities in TEFAP; the program served as a means for disposing of large stockpiles of government-held commodities. Beginning in FY1989, the value of bonus foods dropped substantially as federal acquisitions and stocks waned, and commodities purchased specifically for TEFAP became the majority of the commodities in the program according to requirements in law (see Appendix B, "Legislative History of TEFAP").

TEFAP expenditures increased in FY2009 and FY2010, largely as a result of additional funding for entitlement commodities and administrative costs provided by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA; P.L. 111-5). The 2008 farm bill (P.L. 110-246) also increased funding for TEFAP's entitlement commodities. Since FY2011, spending on bonus and entitlement commodities has fluctuated between approximately $500 million and $600 million (inflation-adjusted).

|

|

Source: CRS calculations using USDA-FNS budget justifications for FY1983-FY2020. Amounts are in FY2018 dollars, adjusted for inflation by CRS using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) U.S. city average series for all items, seasonally adjusted. See Appendix A for exact amounts and notes. |

State Allocation Formula

TEFAP's entitlement commodity and administrative funds are allocated to states based on a statutory formula that takes into account poverty and unemployment rates.82 Specifically, USDA calculates each state's share of the total national number of households with incomes below the federal poverty level and each state's share of the total national number of unemployed individuals. A state's share of households in poverty is then multiplied by 60% and its share of unemployed individuals is multiplied by 40% to calculate the state's share of TEFAP commodities and funds. For example, if a state has 4% of all households in poverty and 2% of all unemployed individuals, it would receive (4% x 60% = 2.4%) + (2% x 40% = 0.8%) = 3.2% of TEFAP funds.83 As noted previously, states may carry over any extra food or administrative funds for one fiscal year (e.g., from FY2019 to FY2020).

State Funding

States must match any administrative funds that are not allocated to emergency feeding organizations or expended by the state on behalf of such organizations.84 In practice, most states use 80% to 100% of their administrative funds to support emergency feeding organizations, resulting in a small state match requirement.85

Beyond the state match, 14 states reported supplying additional state funds "to support the TEFAP program either directly or indirectly" in the 2015 Washington State Department of Agriculture survey (discussed previously).86 There is a maintenance of effort requirement in TEFAP, meaning that states cannot reduce their own funding or commodity support for recipient agencies below the level that they were supporting such organizations at the program's inception or FY1988 (when the maintenance of effort went into effect)—whichever is later.87

Role of TEFAP During Disaster Response

States have the authority to distribute existing inventories of USDA Foods to disaster relief organizations when the President issues a disaster declaration.88 This includes foods from TEFAP inventories and other food assistance programs such as the National School Lunch Program.89 For example, foods intended for TEFAP were used for disaster response in Florida, Texas, and Puerto Rico following Hurricanes Irma, Harvey, and Maria in 2017.90 TEFAP foods used for disaster assistance are replenished by USDA, so the overall level of commodities in the program is not affected and program operations continue in the aftermath of a disaster.

At times, Congress may appropriate additional funds for TEFAP for the purposes of disaster relief. Most recently, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123) provided $24 million in supplemental funding for TEFAP commodities and administrative funds to jurisdictions that received a major disaster or emergency declaration related to the consequences of Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria or wildfires in 2017.

The 2018 Farm Bill

In addition to reauthorizing and extending TEFAP's funding, the 2018 farm bill (§4018 of P.L. 115-334) made policy changes to TEFAP. The law authorized Farm to Food Bank Projects (as termed by USDA), which are projects that support the harvesting, processing, packaging, and/or transporting of raw or unprocessed commodities from agricultural producers, processors, and distributors to emergency feeding organizations. The law provided $4 million in annual mandatory funding for the projects from FY2019-FY2023 and required at least a 50% nonfederal match. States must include a plan of operations for Farm to Food Bank Projects in their state TEFAP plans in order to receive federal funding. The law gives USDA discretion to determine how funds are allocated to such states; through rulemaking published in October 2019, USDA established that funds would be allocated the same way as current TEFAP entitlement funds, based on their share of households in poverty and unemployed persons (see "State Allocation Formula").91

The 2018 farm bill also required states to include, in their TEFAP state plans, a plan to provide emergency feeding organizations and other recipient agencies with the opportunity to provide input on commodity preferences and needs (e.g., in regards to USDA Foods), such as through a state advisory board. In addition, the law required USDA to issue guidance outlining best practices to minimize food waste of commodities donated by non-USDA entities. USDA issued guidance regarding this provision on August 15, 2019.92

The TEFAP provisions in the 2018 farm bill largely drew from language in the Senate-passed 2018 farm bill (the Senate version of H.R. 2). The House-passed 2018 farm bill (the House version of H.R. 2) included different TEFAP proposals. The House bill would have provided higher funding for TEFAP's entitlement commodities ($250 million plus $60 million in each of FY2019-FY2023, adjusted annually for inflation).93 Like the Senate bill, the House bill would have established farm to food bank projects; however, unlike the Senate bill, the House bill would have provided $20 million out of the entitlement commodity appropriation for the projects. In addition, the House bill would have limited the projects to the procurement of excess fresh fruits and vegetables grown in the state or surrounding regions.

Appendix A. TEFAP Expenditures, FY1983-FY2018

Table A-1. TEFAP Expenditures (Obligations), FY1983-FY2018

Constant (inflation-adjusted) FY2018 dollars in millions

|

Fiscal Year |

Administrative Funds |

Entitlement Commodities |

Bonus Commodities |

Total |

|

1983 |

126.4 |

0.0 |

2,098.5 |

2,224.9 |

|

1984 |

121.4 |

0.0 |

2,501.1 |

2,622.5 |

|

1985 |

133.5 |

0.0 |

2,276.4 |

2,409.9 |

|

1986 |

114.3 |

0.0 |

1,934.1 |

2,048.4 |

|

1987 |

111.1 |

0.0 |

1,879.4 |

1,990.5 |

|

1988 |

106.7 |

0.0 |

1,146.5 |

1,253.3 |

|

1989 |

101.9 |

326.0 |

275.5 |

703.3 |

|

1990 |

97.0 |

308.5 |

230.7 |

636.3 |

|

1991 |

92.4 |

280.8 |

165.0 |

538.1 |

|

1992 |

80.5 |

271.3 |

152.6 |

504.5 |

|

1993 |

78.1 |

278.5 |

183.8 |

540.4 |

|

1994 |

67.8 |

202.5 |

82.1 |

352.4 |

|

1995 |

66.0 |

107.6 |

58.1 |

231.6 |

|

1996 |

49.3 |

78.8 |

22.9 |

151.0 |

|

1997 |

65.2 |

203.7 |

46.1 |

315.0 |

|

1998 |

71.4 |

153.8 |

167.3 |

392.5 |

|

1999 |

69.1 |

134.6 |

162.2 |

365.9 |

|

2000 |

63.8 |

144.4 |

236.9 |

445.1 |

|

2001 |

63.3 |

141.1 |

452.6 |

657.0 |

|

2002 |

75.8 |

188.2 |

239.3 |

503.3 |

|

2003 |

81.4 |

177.7 |

330.2 |

589.4 |

|

2004 |

78.9 |

171.3 |

310.6 |

560.8 |

|

2005 |

75.6 |

168.4 |

199.1 |

443.2 |

|

2006a |

79.0 |

169.4 |

83.4 |

331.8 |

|

2007 |

70.5 |

158.8 |

70.8 |

300.2 |

|

2008 |

66.5 |

212.3 |

207.4 |

486.2 |

|

2009b |

103.5 |

392.8 |

436.6 |

932.9 |

|

2010b |

139.8 |

266.4 |

398.2 |

804.5 |

|

2011 |

78.7 |

255.6 |

263.4 |

597.7 |

|

2012 |

71.9 |

265.5 |

332.5 |

669.8 |

|

2013a |

69.1 |

265.8 |

245.7 |

580.7 |

|

2014 |

73.1 |

283.6 |

316.2 |

672.9 |

|

2015 |

78.1 |

345.0 |

319.5 |

742.6 |

|

2016 |

81.4 |

334.8 |

319.3 |

735.5 |

|

2017 |

85.3 |

323.7 |

275.1 |

684.1 |

|

2018 |

90.7 |

287.5 |

308.9 |

687.1 |

Source: CRS calculations using USDA-FNS budget justifications for FY1983-FY2020. Amounts are in FY2018 dollars, adjusted for inflation by CRS using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) U.S. city average series for all items, seasonally adjusted.

Notes: Obligations after conversions. For fiscal years 2002 to 2008, states were allowed to convert $10 million of entitlement commodity funds into administrative funds. For fiscal years 2009 to 2017, states were allowed to convert 10% of entitlement commodity funds into administrative funds. For FY2018, they were allowed to convert 15%. States may convert any amount of administrative funds into food funds, but this happens to a lesser extent. For FY2015-FY2018, table includes any entitlement commodity funds that states carried over into the next fiscal year.

a. Includes roughly $6 million in supplemental funding for disaster relief in FY2006 and FY2013.

b. Includes $178 million in supplemental American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funding in FY2009 and FY2010. ARRA funding included $100 million in TEFAP commodity funding and $50 million in TEFAP administrative funding that was distributed in FY2009 and FY2010. An additional $28 million from the WIC ARRA contingency fund was reprogrammed as TEFAP administrative funds in FY2010.

Appendix B. Legislative History of TEFAP

Legislative History, 1981 to 200194

1980s. TEFAP began in 1981-1982 as a temporary expedient designed to dispose of stockpiles of government-held food commodities. Establishment of TEFAP occurred in the aftermath of noticeable reductions in the coverage of and benefits provided by federal food assistance programs (e.g., food stamps, school meal programs) legislated in 1981 and 1982, and in the midst of an economic recession and concern over hunger and homelessness.

The Reagan Administration began distribution of excess federally held food commodities in 1981-1982. These commodities, often termed bonus commodities, were in excess of those needed to fulfill other domestic and international federal commitments to provide food commodities (e.g., to schools operating school meal programs). In 1983, Congress followed up with legislative authority that created what was known for more than a decade as the Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), as well as funding for grants to help with distribution costs.95 Establishment of TEFAP helped reduce federal commodity stocks (and storage costs associated with holding them), provided an alternative source of food assistance for low-income individuals, and supported an expanding network of emergency food aid providers that also drew food and other resources from many nongovernmental sources.

In TEFAP's early years, the only significant federal expenditures involved were appropriations for the grants supporting providers' distribution costs; the bonus commodities that were provided were acquired under separate USDA programs to support the agricultural economy.96 However, when commodity holdings began to drop substantially in the late 1980s because of changes in agricultural policies and the economy, Congress established the practice of providing federal funds to buy food commodities specifically for donation through TEFAP (in addition to continuing support for cash grants for distribution costs).

1988-1990. In 1988, after the Reagan Administration indicated plans to phase out TEFAP because of the lack of commodity inventories, Congress mandated funding (starting at $120 million for FY1989) in the Hunger Prevention Act of 1988 to buy commodities for distribution through TEFAP, thereby "entitling" the program to a minimum level of support regardless of the level of federal commodity holdings. The law also created a separate mandatory program to buy commodities for soup kitchens and other organizations not receiving TEFAP commodities (mandatory funding was provided at $40 million for FY1989). While some soup kitchens and other entities could receive federal food donations through a small separate initiative to help charitable organizations and others could participate as local TEFAP providers, the separate program was established out of a concern that most commodities for emergency feeding were going to local agencies that distributed food packages directly to individuals and families (e.g., food pantries), rather than to shelters, soup kitchens, and other providers serving meals in congregate settings.

Two years later, the 1990 omnibus farm bill made commodity and cash-grant funding authority for TEFAP and the soup kitchen program discretionary—that is, expenditures on commodities and distribution-cost grants were made dependent on annual appropriations decisions, not mandated by the authorizing law entitling the program to a specific minimum funding level.

1990s. Although the authorizing law for TEFAP, the Emergency Food Assistance Act (EFA) of 1983, has been amended a number of times and the word "Temporary" has been dropped from the program's official title, perhaps the most significant changes since 1988 were made in 1996. The 1996 farm bill (P.L. 104-127) extended the discretionary authority to appropriate money for commodities and distribution-cost grants for TEFAP and soup kitchen programs through FY2002. But, more significantly, the subsequent 1996 welfare reform law (the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act; P.L. 104-193) changed how these federal efforts are structured and funded.

The welfare reform law (1) consolidated TEFAP and the soup kitchen program in one statute (the EFA) so that states could get a single TEFAP grant of commodities and distribution-cost funds for all types of emergency feeding organizations, and (2) mandated funding of $100 million a year (through FY2002) to purchase food commodities for the program. This was in addition to any commodities that might be bought with money appropriated under discretionary authority in the EFA and any bonus commodities that might be made available at USDA's discretion. This second change was intended to entitle the program to a minimum level of commodity support when regularly appropriated money is not made available to buy commodities or excess federal commodity holdings for TEFAP distribution are minimal or nonexistent. It was accomplished through an amendment to the Food Stamp Act (now, the Food and Nutrition Act) effectively setting aside $100 million a year in "entitlement" appropriations under the act to purchase TEFAP commodities.

As a result, the majority of funding for TEFAP (i.e., for commodity purchases) typically is now made available under the aegis of the Food and Nutrition Act appropriation unless Congress chooses to appropriate additional money for commodities under authority provided in the EFA. The minority of funding—funds for administrative and distribution costs—is appropriated under the authority of the EFA.

Appendix C. TEFAP Funding by State

|

State/Territory |

FY2019 Allocation |

|

Alabama |

$6,532,547 |

|

Alaska |

1,147,381 |

|

Arizona |

9,518,819 |

|

Arkansas |

3,934,458 |

|

California |

49,202,084 |

|

Colorado |

5,345,599 |

|

Connecticut |

4,115,772 |

|

DC |

1,210,392 |

|

Delaware |

1,219,642 |

|

Florida |

25,764,399 |

|

Georgia |

14,373,035 |

|

Guam |

359,769 |

|

Hawaii |

1,237,315 |

|

Idaho |

1,944,522 |

|

Illinois |

16,984,560 |

|

Indiana |

7,566,751 |

|

Iowa |

2,913,005 |

|

Kansas |

3,432,497 |

|

Kentucky |

6,413,583 |

|

Louisiana |

7,417,749 |

|

Maine |

1,310,217 |

|

Maryland |

6,449,489 |

|

Massachusetts |

6,985,816 |

|

Michigan |

13,173,233 |

|

Minnesota |

5,318,432 |

|

Mississippi |

4,705,105 |

|

Missouri |

7,157,597 |

|

Montana |

1,282,736 |

|

N Mariana Isl. |

232,236 |

|

Nebraska |

1,754,807 |

|

Nevada |

3,874,261 |

|

New Hampshire |

1,063,002 |

|

New Jersey |

9,870,552 |

|

New Mexico |

3,482,535 |

|

New York |

26,144,053 |

|

North Carolina |

14,592,537 |

|

North Dakota |

679,771 |

|

Ohio |

15,535,583 |

|

Oklahoma |

5,313,211 |

|

Oregon |

5,110,136 |

|

Pennsylvania |

16,052,827 |

|

Puerto Rico |

13,271,945 |

|

Rhode Island |

1,282,694 |

|

South Carolina |

6,552,924 |

|

South Dakota |

979,974 |

|

Tennessee |

8,232,480 |

|

Texas |

36,306,909 |

|

Utah |

2,743,331 |

|

Vermont |

723,547 |

|

Virgin Islands |

276,975 |

|

Virginia |

8,543,588 |

|

Washington |

8,729,913 |

|

West Virginia |

2,917,143 |

|

Wisconsin |

5,881,972 |

|

Wyoming |

602,026 |

Source: USDA-FNS, TEFAP Administrative Funds and Food Entitlement Allocations: FY2019, December 2019, https://www.fns.usda.gov/tefap/total-tefap-assistance-states.

Notes: Table shows state allocations after conversion of any entitlement commodity funds to administrative funds, and administrative funds to commodity funds. Includes any funds carried over from FY2018.