Introduction

Domestic violence is a term often used to describe abuse of a spouse or child in the home. Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a subset of domestic violence that is committed against a spouse, or current or former dating partner. IPV is treated as a public health issue and is monitored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at the national level. According to the CDC, approximately one in five women and one in seven men report having experienced severe physical violence from an intimate partner in their lifetime.1 In addition, crime statistics suggest that 16% of all U.S. homicide victims are killed by an intimate partner. Nearly half of female homicide victims are killed by a current or former male intimate partner.2 IPV criminal offenses are typically defined and prosecuted at the state level; however, federal law imposes penalties on some domestic violence offenders.3 Military IPV offenders may be prosecuted in civilian courts, but are also subject to punitive measures within the military justice system under Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) provisions.4

From a military effectiveness perspective, IPV may lead to productivity losses, degraded servicemember or unit readiness, and subsequent costs to the Department of Defense (DOD).5 When servicemembers are victims, associated mental and physical trauma may affect their ability to deploy or serve in worldwide assignments and can lead to capability gaps in units. In addition, qualified veterans who were victims of IPV may require additional care for co-morbid conditions through the Veterans' Health Administration (VHA).

Congress has constitutional authority to fund, regulate, and oversee the Armed Forces, including the military justice system. Congress has used this authority in recent years to mandate domestic violence prevention and victim response policies, programs, and services. As such, there is enduring congressional interest on domestic violence prevention and response, victim well-being, and perpetrator accountability.

This report starts with an overview of IPV in the Armed Forces, including risk factors, prevalence, and concerns specific to military families and certain subgroups. The next section focuses on DOD prevention activities, including efforts to screen out high-risk individuals, increase awareness, and address relationship stresses before they escalate. This section is followed by a discussion of intervention activities implemented by clinical service providers, military commanders, and other stakeholders. The next section describes actions taken by DOD and the Congress to provide victim support, resources, and advocacy. Following that, the report touches on how military law enforcement organizations respond to and investigate allegations of domestic abuse and how offenders are held accountable under the military justice system. Finally, the report touches on some continuing issues for congressional oversight and action.

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a crime characterized by recidivism and escalation, meaning offenders are likely to be repeat abusers, and the intensity of the abuse or violence is likely to grow over time. IPV can harm victims in various ways, resulting in physical injury, mental health problems, and adverse pregnancy outcomes (e.g., low birth weight, preterm birth, and neonatal death).6 Many victims of IPV continue to struggle with stress and anxiety long after incidents occur. For example, national surveys have found that among victims of IPV, 41% of women and 10% of men have experienced symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).7

In addition, alleged perpetrators can face decreased productivity at work, loss of income, and incarceration. Domestic violence can also affect the behavior and well-being of subsequent generations. Research has shown that children who grow up in a home where IPV occurs are at higher risk for behavioral, cognitive, and emotional disorders.8 Relatedly, studies have indicated that perpetrators often have a history of experiencing abuse or witnessing abusive relationships within their families as a children or young adults.

Factors unique to military service may exacerbate risks for both perpetrators and victims of IPV.9 First, servicemembers and their families frequently move for various assignments.10 This separates individuals from natural support networks, which can heighten stress on intimate partnerships, including those involving caretakers, and lead to social isolation. Whereas a victim of domestic abuse might normally escape a situation by temporarily moving in with a local family member or trusted friend, this option may not be readily available, particularly for those located at overseas or remote installations.11 Similarly, difficulties in coping with frequent moves and other pressures associated with military service (e.g., a spouse's long hours, shift work, or unpredictable deployments) may contribute to marital conflict and instability (e.g., reunification cycles, separation, or divorce). In addition, frequent household moves may complicate the capacity of nonmilitary spouses to achieve full employment. Lack of financial independence and the threat of lost or reduced military benefits may serve as a disincentive for military spouse victims to seek help in cases of abuse. Finally, prior interpersonal trauma is also indicated as a risk factor for both perpetrators and victims. Some data suggest that women who have experienced abuse in childhood may be more likely to join the military to escape a violent or unstable home environment.12

At the same time, some factors unique to military service may mitigate IPV incidence. For example, access to health care (TRICARE), stable pay and benefits, and the availability of installation-based family support services may help with financial stability and early intervention for at-risk couples. In addition, military servicemembers who are perpetrators of abuse may face more immediate or severe sanctions for IPV than their civilian counterparts (e.g., reductions in pay, loss of employment, and/or benefits). Military commanders have broad discretion to impose administrative remedies, penalties, or referrals for judicial action for abusers under their command (see section on "Commander's Authority"). In this way, military commanders can play an important role in IPV intervention, and in establishing a climate where victims feel safe to report and perpetrators are held accountable.

DOD Organization and Definitions

Prior to 1980, the military services (Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps) conducted their own family advocacy programs, primarily under their respective military medical service programs.13 In response to a 1979 U.S. General Accounting Office (now called the U.S. Government Accountability Office) report that characterized military service family violence prevention programs as inconsistent and understaffed, DOD established the Military Family Resource Center (MFRC) as a three-year demonstration project through a DOD-subsidized grant from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).14 In 1981, Congress first appropriated funds for DOD family violence prevention and between 1981 and 1983, responsibility for total funding of the program transitioned to DOD's sole responsibility.15 During that time, DOD also published Directive 6400.1, establishing the Family Advocacy Program and an Advocacy Committee with representatives from the services and DOD.16 Given the success of the MFRC demonstration and DOD's interest in consolidating programs under a single secretariat, DOD transferred MFRC activities to the Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Force Management and Personnel in August of 1985.

The Military Family Act of 1985 formally established an Office of Family Policy under the Office of the Secretary of Defense to "coordinate programs and activities of the military departments to the extent that they relate to military families."17 Congress later amended and codified the act under Chapter 88 of Title 10, U.S. Code, in 1995 as part of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 1996 and renamed the Office of Family Policy as the Office of Military Family Readiness Policy. Currently, this office falls under the purview of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (USD) for Personnel and Readiness (P&R).18 Within USD (P&R), the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Community and Family Policy has oversight responsibility for military family programs, including domestic violence prevention and response. The military services implement domestic violence prevention and response through the Family Advocacy Program (FAP). Military law enforcement activities fall under the purview of USD (P&R) and the Defense Human Resource Activity (DHRA), while central incident databases are housed in the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC), also under DHRA.

Family Advocacy Program (FAP)

Currently, the Family Advocacy Program (FAP) is the designated program within DOD and the services to address "domestic abuse, child abuse and neglect, and problematic sexual behavior in children and youth" through prevention, awareness, treatment, and rehabilitation services.19 The military services implement the FAP. FAP managers also work in coordination with civilian agencies involved in domestic violence response. In 2016, Congress required the FAP to provide an annual report to Congress on child abuse and neglect and domestic abuse in military families.20

Family Advocacy and Family Assistance Funding

Family advocacy and family assistance programs are funded through annual appropriations as part of the Defense-wide Operation and Maintenance budget for DOD dependents education. DOD-requested FAP funds are directed to each of the military services to implement clinical intervention programs, "in the areas of domestic abuse, intimate partner violence, child abuse and neglect, and problematic sexual behavior in children and youth."21 FAP funding also supports a DOD hotline for reporting allegations of child abuse, training for domestic violence responders and members of the chain of command, public awareness activities, support for obtaining civilian protection orders, and research on domestic violence prevention. According to DOD budget documents, defense-wide funding for family assistance supports

programs and outreach services to include, but not limited to: the 1-800 Military OneSource call center; the Military and Family Life Counseling Program; financial outreach and non-medical counseling; Spouse Education and Career Opportunities; child care services; youth programs; morale, welfare and recreation programs and, support to the Guard and Reserve service members, their families, and survivors. Funding supports DoD-wide service delivery contracts to support all Active Duty, Guard, and Reserve Components.22

The total defense-wide funding request for family assistance and family advocacy for FY2020 was $877 million, an increase of 5.5% from the previous year (see Table 1).

|

FY2015 (actual) |

FY2016 (actual) |

FY2017 (actual) |

FY2018 (actual) |

FY2019 (enacted) |

FY2020 (requested) |

|

|

Family Advocacy Program (FAP) |

705.5 |

194.9 |

194.3 |

198.2 |

208.2 |

230.6 |

|

Family Assistance |

632.4 |

596.2 |

628.9 |

622.9 |

646.0 |

|

|

TOTAL |

705.5 |

827.3 |

790.5 |

827.2 |

831.1 |

876.5 |

Source: Compiled by CRS from DOD budget documents for Defense-wide Operation and Maintenance, DOD Dependents Education.

Note: DOD did not report separate line items for FY2015 Family Assistance and FAP funding. Total funding for Family Assistance and FAP covers a broader range of activities than IPV.

FAP Personnel and Accreditation

DOD policy requires specific credentialing for those assigned as FAP managers, including a master's or doctoral level degree in the behavioral sciences from an accredited U.S. university or college, state licensure, and certain experience.23 Service Secretaries are also responsible for establishing criteria for other FAP personnel, and for annual accreditation and certification of installation FAPs. According to DOD, the FAP is supported by over 2,000 government and contracted personnel.24

Definitions

The CDC uses the term intimate partner violence (IPV) to describe "physical violence, sexual violence, stalking and psychological aggression (including coercive acts)" by a current or former spouse or dating partner. DOD often refers to IPV as domestic violence or domestic abuse. Domestic violence is defined as an offense with legal consequences under the U.S. Code, the UCMJ, and state laws, while domestic abuse refers to a pattern of abusive behavior. DOD defines four types of abusive behavior: (1) physical abuse, (2) emotional abuse, (3) sexual abuse, and (4) neglect of spouse (see text box below on "DOD Definitions of Domestic Abuse and Domestic Violence").

Under the DOD definition, a victim of domestic violence may be a current or former spouse, an intimate partner sharing a common domicile, or a person with whom the abuser shares a child. Under the CDC's definition, an intimate partner does not need to share a common domicile or child. DOD's narrower definition of what constitutes IPV correlates to victim and dependents' eligibility for certain benefits or services following an incident of reported abuse (see section below on "Victim Support and Services"). Sexual violence involving military personnel in which the offender and victim do not share a domicile, child, or other legal relationship (i.e., spouse or former spouse), is typically handled by DOD's Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (SAPR) program.25

|

DOD Definitions of Domestic Abuse and Domestic Violence Domestic Violence. An offense under the U.S. Code, the UCMJ, and state laws involving the use, attempted use, or threatened use of force or violence against a person, or a violation of a lawful order issued for the protection of a person who is:

Domestic Abuse. Domestic violence or a pattern of behavior resulting in emotional/psychological abuse, economic control, and/or interference with personal liberty that is directed toward a person who is:

Types of Maltreatment

Source: DOD, Domestic Abuse Involving DoD Military and Certain Affiliated Personnel, DODI 6400.06, May 26, 2017. For a complete list of maltreatment categories and corresponding definitions, see http://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodm/640001m_vol3.pdf. |

Incident Data and Reporting

DOD collects data on domestic abuse incidents through the FAP Central Registry, created by in 1994. In 1999, as part of the FY2000 NDAA, Congress explicitly mandated that DOD maintain a centralized database and collect annual reports from the Services on

(1) Each domestic violence incident reported to a commander, a law enforcement authority of the armed forces, or a family advocacy program of the Department of Defense.

(2) The number of those incidents that involve evidence determined sufficient for supporting disciplinary action and for each such incident, a description of the substantiated allegation and the action taken by command authorities in the incident.

(3) The number of those incidents that involve evidence determined insufficient for supporting disciplinary action and for each such case, a description of the allegation.26

The military services collect data at the installation level. Each installation's FAP enters data into its respective service registry and then submits reports to the DMDC, which maintains the registry for all of DOD.27 Data elements include demographic information, individual identifiers (i.e., name and social security number), relationship indicators, incident details (e.g., location and date), and the type and severity of abuse.28 When an FAP office receives a report of domestic abuse, an incident determination committee (IDC) determines whether the incident "met criteria" to be submitted and tracked within the database.29 Incidents that do not meet the criteria for domestic abuse are also included in the database, but identifiable individual information is not tracked. DOD uses the aggregate data in this registry to produce annual reports to Congress, analyze the scope of abuse and trends, and support budget requests for domestic violence prevention resources.

The FAP Central Registry is not the only database that includes domestic violence information involving military servicemembers. DOD also maintains the Defense Incident-Based Reporting System (DIBRS) as a central repository at DMDC for criminal incident-based statistical data.30 DIBRS includes criminal activity related to domestic abuse, but would typically not capture cases without law enforcement involvement. (See section on "Crime Reporting to National Databases" for more detail.) While GAO has highlighted concerns about gaps and overlaps in these two databases (see text box below on "GAO Reviews of DOD Domestic Violence Data Collection Efforts"), DOD has resisted consolidating them, stating that

DIBRS and the Services' FAP Central Registries, from which the DoD Central Registry contains limited data elements, serve fundamentally different purposes: law enforcement and clinical treatment, respectively. […] Using the FAP database for law enforcement data collection purposes will significantly degrade the perception of the FAP as a program that provides clinical assistance to troubled families.31

In some cases, the DOD's database for military sexual assault, the defense sexual assault incident database (DSAID) may also capture data on incidents of sexual abuse involving spouses or intimate partners.32 The prevalence of intimate partner sexual assault or stalking of servicemember victims may also be captured in DOD's annual workforce and gender relations (WGR) surveys. These surveys would not generally capture all types of domestic abuse, and surveys do not include military spouses. Therefore, while incidents of domestic abuse that are reported to FAP or other military officials are generally captured in the data, it is possible that the actual prevalence (including unreported incidents) within the military is higher than reported.

|

GAO Reviews of DOD Domestic Violence Data Collection Efforts In 2006, as part of a congressionally mandated review of the management of domestic violence programs and systems, GAO found significant deficiencies in data collection and reporting.33 In particular, the GAO noted that until January 2006, the Central Registry only contained reported incidents of abuse involving spouses and not intimate partners. In addition, a review of DIBRS information found that a number of installations were not reporting disciplinary actions taken by the commanders, as required by statute. In 2010, Congress asked GAO to review the progress made by DOD on the recommendations from the 2006 review.34 In the 2010 review, GAO raised concerns about potential for overlap, gaps, or data reliability issues between the DIBRS and FAP databases.35 GAO also noted in the 2010 report that while previous attempts to get a more accurate count of domestic violence incidents by matching DIBRS and Central Registry data had been made, there was no systematic methodology in place for matching data or ensuring accuracy.36 |

What Proportion of the Military-Connected Population is Affected?

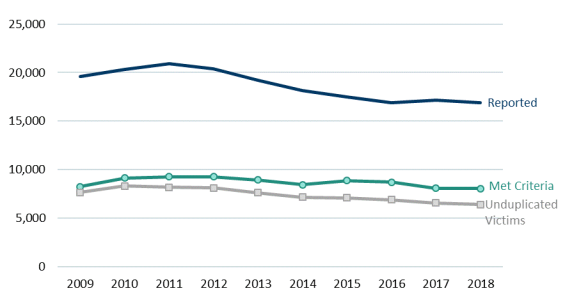

The total active duty population is over 1.3 million, approximately 16% of whom are women.37 In addition, the total number of active duty military spouses is about 600,000, about 25% of which are age 25 or younger.38 Based on data collected by the services, there were 16,912 reported incidents of spouse and intimate partner abuse in FY2018.39 Of these, roughly half (8,039) of the reports met the criteria for abuse under DOD definitions, affecting 6,372 victims (see Figure 1 below).40 Physical abuse accounted for 73.7% of all met criteria incidents, followed by emotional abuse (22.6%). Sexual abuse and neglect accounted for a smaller proportion of domestic abuse incidents—3.6% and 0.06% respectively.41

There has been little change in the rate or number of reported incidents that met criteria for domestic abuse since FY2009. While the total number of incidents in FY2018 is 19% lower than the number of incidents at the most recent peak in FY2011, the total force size also shrank during that time. In fact, the rate of incidents that met criteria for spouse abuse has not varied significantly since FY2008.42 While there are no clear trends in the number of incident reports, there are some indications that the categories of abuse being reported may have changed over the past eight years. The number of reported domestic abuse incidents involving sexual abuse has generally increased incrementally since FY2009, when DOD added this as a category for reporting (there was a slight drop in reported incidents in FY2018). This change in reporting may be due to a number of factors, including an actual increase in these types of IPV; cultural shifts in the perception of sexual abuse within existing relationships; and greater general awareness of sexual violence, reporting avenues, and available resources among military servicemembers, military-connected intimate partners, and first responders.43

Victim Profile

Victims of reported abuse are predominately (two-thirds) female. About half of the victims who reported spouse abuse to DOD and two-thirds who reported intimate partner abuse were members of the military at the time the abuse took place (see Table 2 below). In FY2018, DOD reported 15 domestic abuse fatalities (13 spouses and 2 intimate partners).44 Of the fatalities, three victims had previously reported abuse to DOD's FAP and four of the perpetrators had been reported previously for at least one prior abuse offense. Nine of the offenders were civilians with military victims.

|

Number of unique victims |

Sex of victims |

Victims by military status |

|||

|

male |

female |

military |

civilian |

||

|

Spouse abusea |

5,550 |

35% |

65% |

54% |

46% |

|

Intimate partner abuseb |

822 |

29% |

71% |

62% |

38% |

Source: DOD, Report on Child Abuse and Neglect and Domestic Abuse in the Military for Fiscal Year 2018, April 2019, pp. 42, 44, 45, 55, and 56.

Notes:

a. Victims married to an offender and who experienced at least one incident of maltreatment that meets criteria for abuse (i.e., physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, or spousal neglect).

b. Victims who experienced at least one incident of maltreatment that meets criteria for abuse and are former spouses, share a child in common with the offender, or are current or former partners who have shared a common domicile.

Offender Profile

Servicemembers account for a majority of reported offenders. In FY2018, 57% of the reported spouse-abuse offenders were servicemembers.45 DOD-reported female offenders were more likely to be civilians, and were the perpetrators in 40% of physical spouse abuse incidents (see Table 3). This percent of female physical abuse offenders reported by DOD is higher than the literature would predict for the general population. Multiple studies suggest that women are less likely to be the primary perpetrator of physical violence in a relationship and that when they use violence it is nearly always in response to physical violence by their partner.46 However, it is unclear from the data if physical abuse perpetrated by women is retaliatory. Sexual abuse cases were almost entirely perpetrated by men (96%) which is consistent with the research.47

|

Sex of offenders |

||

|

Type of abuse |

male |

female |

|

Physical |

60% |

40% |

|

Emotional |

75% |

25% |

|

Sexual |

96% |

4% |

|

Neglect |

100% |

0% |

|

Spouse abuse (total) |

62% |

38% |

Source: DOD, Report on Child Abuse and Neglect and Domestic Abuse in the Military for Fiscal Year 2018, April 2019.

Perpetration of IPV in military partnerships may be underrepresented in DOD incident data, particularly if the victims are civilians, unmarried to the perpetrator, or not residing on a military installation. Incidents that occur outside of a military installation are less likely to be witnessed by military first responders and unmarried civilian intimate partners of a servicemembers are typically ineligible to be treated at military treatment facilities (MTFs). Coordination between civilian and military officials for domestic violence reporting is discussed in later sections (see "Confidentiality: Restricted and Unrestricted Reporting" and "Community Coordination").

Younger Troops are at Higher Risk of Offending and Being Victimized

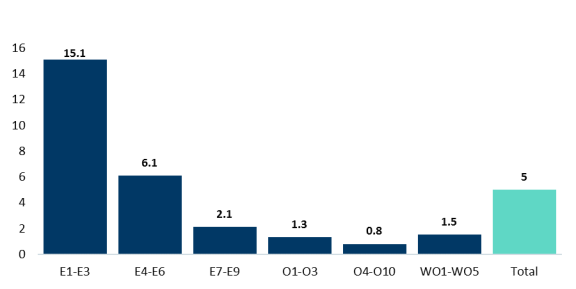

National-level data suggest that intimate partner violence primarily begins at a young age: an estimated 71% of females and 58% of males reported having first experienced sexual violence, intimate partner physical violence, or stalking before the age of 25.48 In addition, approximately 23% of female victims reported having first experienced intimate partner violence before the age of 18.49 Similarly, rates of reported domestic abuse in the military are highest among junior enlisted (E-3 and below) families who are typically between the ages of 18 and 24. In FY2018, the rate of offenders in the grades of E-1 to E-3 was 15.1 per 1,000 married couples; in contrast to the overall rate of 5 per 1,000 married couples (see Figure 2).50

How does IPV in the Military Compare to the Civilian Population?

A number of factors complicate comparisons of military and nonmilitary IPV datasets, particularly the infrequent reporting of national civilian data and differences between how DOD and federal nonmilitary data are reported, collected, and aggregated. For example, each state may have different laws and processes for recording IPV, whereas all military branches use a common IPV definition and process. In addition, military members and their spouses and partners are, on average, younger than the general population. Therefore, direct (unweighted) comparisons of incident rates at the national or local level should be interpreted with some caution.

Some studies, nonetheless, have compared IPV prevalence data across military and civilian populations. Since 2010, the CDC has conducted the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), which collects data from adult men and women on past-year and lifetime experiences of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence at the state and national levels.51 In 2010, CDC randomly sampled military women and wives of active duty members to compare IPV prevalence rates among civilians, military women and military spouses and generally found similar prevalence rates across the populations.52 Where there were differences, active duty women were generally found to have a decreased risk of IPV relative to the civilian population. Nevertheless, active duty women who were deployed in the previous three years were significantly more likely to have experienced physical and sexual IPV compared with those who had not deployed.53

Table 4. Estimated Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence: Comparisons Across Military and Civilian Female Populations

2010

|

Type of Intimate Partner Violence |

General Population Women |

Active Duty Women (deployed w/in 3 years) |

Active Duty Women (not deployed w/in 3 years) |

Wives of Active Duty Men (deployed w/in 3 years) |

Wives of Active Duty Men (not deployed w/in 3 years) |

|

Contact Sexual Violence |

|||||

|

Lifetime |

20.0% |

13.7% |

11.4% |

13.4% |

13.1% |

|

3-years |

3.7% |

4.5% |

4.0% |

3.5% |

- |

|

Psychological Aggression |

|||||

|

Lifetime |

56.7% |

47.2% |

41.1% |

41.2% |

40.0% |

|

3-years |

28.2% |

22.6% |

24.7% |

15.8% |

12.0% |

|

Severe Physical Violence |

|||||

|

Lifetime |

26.9% |

21.9% |

16.0% |

20.6% |

15.9% |

|

3-years |

6.2% |

5.7% |

5.4% |

4.8% |

- |

Source: CDC, Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence, Stalking, and Sexual Violence Among Active Duty Women and Wives of Active Duty Men—Comparisons with Women in the U.S. General Population, 2010, Technical Report, March 2013, Tables 2, 3, 6, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20 http://www.sapr.mil/public/docs/research/2010_National_Intimate_Partner_and_Sexual_Violence_Survey-Technical_Report.pdf.

Notes: The age range for women in these data is18-59 years. Contact sexual violence as completed forced penetration, attempted forced penetration, completed alcohol- or drug-facilitated penetration, being made to penetrate someone else, sexual coercion, and other unwanted sexual contact experiences. Severe physical violence includes acts such as being hit with something hard, being kicked or beaten, or being burned on purpose. Psychological aggression includes expressive aggression (e.g., name-calling, or insulting or humiliating an intimate partner) and coercive control, which includes behaviors that are intended to monitor, control, or threaten an intimate partner. Contact sexual violence for wives of active duty men not deployed within three years is not reported due to high standards errors or small sample size.

Prevention

DOD has focused on a number of activities to prevent IPV and mitigate the escalation and repetition of violence or abuse following an initial offense.54 The CDC has identified several individual, relationship, community, and societal risk factors for domestic violence (see Appendix B). Some of these risk factors are inherent in the military environment. For example, youth is considered a risk factor, and the bulk of servicemembers are recruited and enlisted or appointed between the ages of 17-26. On the other hand, military protocols for entry screening, education and training, and support structures may provide protective factors and deterrence.

Entry Screening

DOD and the services use medical, cognitive, and other qualification standards to screen those seeking entry into the Armed Forces for IPV risk factors. For example, DOD medical standards generally prohibit enlistment or appointment of individuals with a history of personality or behavioral disorders.55 In addition, a history of drug or alcohol abuse can be a disqualifying factor.56 Past misconduct and criminal convictions can also disqualify individuals.

Those disqualified from service may request a conduct waiver, which typically requires specific information about the offense(s) and "letters of recommendation from responsible community leaders, such as school officials, clergy, and law enforcement officials, attesting to the applicant's character or suitability."57 Convicted domestic violence offenders, on the other hand, are typically ineligible for conduct waivers, pursuant to the Lautenberg Amendment Gun Control Act of 1968.58 Domestic battery or other violent offenses committed without conviction may also be disqualifying.59

|

The Lautenberg Amendment and Military Service Some studies have found that access to firearms increases the risk for intimate partner homicide.60 Consequently, Congress has taken actions to reduce firearm access for known offenders. A 1996 amendment to the Gun Control Act of 1968 (P.L. 104-208, 18 U.S.C. §922) makes it a felony for any individual convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence to ship, transport, possess or receive firearms or ammunition. The 1996 amendment, sometimes referred to as the Lautenberg Amendment (named after its sponsor, Senator Frank Lautenberg), also makes it a felony for another person to sell or otherwise dispose of a firearm to any person they have reasonable cause to believe has such a conviction, regardless of when the conviction occurred. There are no exceptions for military personnel or military-issued weapons. As a result, those convicted of domestic violence would be unable to carry a firearm and are thus ineligible for entry into military service.61 According to DOD policy, if a member is found to have been convicted of a domestic violence conviction in a civilian court or a general or special court martial, an appropriate military authority will "immediately retrieve all government-issued firearms and ammunition, suspend his/her authority to possess government-issued firearms or ammunition, and advise them to dispose of their privately owned firearms and ammunitions lawfully. These actions shall also be taken if there is reasonable cause to believe a military member has a qualifying conviction."62 |

In recent years, as recruiting quantity targets have increased to force end-strength numbers, the Services, and particularly the Army, have increased the use of conduct, and other waivers.63 Some have questioned whether those with waivers for any kind of misconduct (e.g., drug, alcohol, or traffic violations) are at higher risk for misconduct offenses while serving in the military.64 One study of Army enlistments between 2003 and 2008 found that while those with conduct waivers for any reason did have higher rates of alcohol and drug-related offenses, the waivers were not significantly associated with substantiated incidents of domestic abuse.65

Education, Training, and Awareness

Prevention programs for domestic violence include education and training components, some of which are required in both law and policy. The FY2000 NDAA required DOD to establish a standard training curriculum for commanding officers on handling domestic violence cases.66 In a 2004 memorandum, the USD (P&R) also required specialized training for military chaplains on confronting a potential domestic violence situation.67

The Family Advocacy Program (FAP) is charged with promoting awareness of domestic abuse through education, training, and information dissemination.68 Training for commanders, troops, counselors, and health care personnel typically focuses on increasing awareness of IPV warning signs and appropriate responses. Training for troops might include workshops or briefings on healthy relationships and family resiliency. Generally, domestic violence prevention training is not mandatory and is not applied uniformly across and within the services. The military services have experimented with tailored education programs for higher-risk demographics. The Navy, for example, has initiated a series of workshops on relationship abuse awareness and prevention that targets junior enlisted members.69 DOD's Military Onesource website also offers a range of self-serve resources and tools to learn more about domestic violence.70

|

Domestic Violence Awareness Month In 1989, the 101st Congress passed the first joint resolution designating October as National Domestic Violence Awareness Month (S.J.Res. 133). The military services typically recognize this month through purple ribbon awareness campaigns and activities (e.g., ceremonies, workshops, posters/fliers, and social media). |

Military and Family Life Counseling

Relationship stressors are indicated as risk factors for IPV. Part of DOD's prevention activities include no-cost, nonmedical, confidential counseling services for members and their families through the Military and Family Life Counseling (MFLC) program.71 These services are part of DOD's prevention activities and include relationship counseling, anger/conflict management, and deployment adjustment (i.e., separation and reintegration). DOD provides these services through a contractor to active and reserve personnel and their immediate families at over 200 military installations or in nearby civilian community centers worldwide. Family life counselors do not handle domestic abuse cases—these are typically referred to the FAP and medical providers, as required. Members and their spouses may also participate in other service-level programs, like chaplain-led marriage retreats or family resiliency workshops under their installation's family readiness program.72 While commanders or others may refer couples to these programs, participation in them is generally optional.

Interventions

While prevention activities generally target the entire population, interventions are targeted at high-risk couples or individuals, or provided after a first alleged offense.73 Interventions include removing individuals and family members from any immediate risk of harm, initiating an investigation, ensuring ongoing safety, and preventing future escalation or offender recidivism. Response to domestic abuse often involves coordination among military commanders, law enforcement officials, health care personnel, social workers, and legal representatives. DOD policies outline specific roles and responsibilities for each of these responders.74 The FY2019 NDAA required the establishment of multidisciplinary teams on military installations to enhance collaboration in response and management of domestic abuse cases.75 The law requires each team to include (1) one or more judge advocates, (2) personnel from military criminal investigation organizations (MCIOs), (3) mental health professionals, (4) family advocacy caseworkers, and (5) other personnel as appropriate.

Clinical Interventions

When an incident is reported to the FAP, a team assesses the situation and coordinates clinical case management, including treatment, rehabilitation, and ongoing monitoring and risk management. FAP employees are typically professional social workers. According to DOD, there are over 2,000 funded positions across the military departments for delivery of FAP services, including "credentialed/licensed clinical providers, Domestic Abuse Victim Advocates, New Parent Support Home Visitors, and prevention staff."76

Military Protective Orders

Once a servicemember has allegedly committed an act of domestic violence, and it is reported to the member's commander, the commander is responsible for holding the perpetrator accountable and taking actions to protect the victim.77 The commander may, for example, issue a military protective order (MPO) to help ensure the victim's safety.78 An MPO generally prohibits contact between the alleged offender and the domestic violence victim.79 A servicemember must obey an MPO at all times, whether inside or outside a military installation; violations may be subject to court martial or other punitive measures. The commanding officer may also restrict an accused servicemember to a ship or to his or her barracks to keep the parties separate. There may be some cases when the victim is a servicemember and the alleged abuser is a civilian. Commanders cannot issue an MPO for civilians, but may arrange for temporary housing on the installation for the servicemember victim and bar the accused civilian from installation access.

While military commanders have a high degree of control over the activities on an installation, they typically lack jurisdiction over events in civilian communities. Approximately 63% of military personnel live in private housing located outside of a military installation.80 Because of this, coordination between military and civilian law enforcement authorities is often required to provide for victim safety. The FY2000 NDAA included a provision to create incentives for collaboration between military installations and civilian community organizations working to prevent and respond to domestic violence.81 In 2002, Congress required that civilian protection orders (CPOs) have full force and effect on military installations.82 This means that if a servicemember violates the terms of a CPO, he or she may be subject to disciplinary actions under the UCMJ, in the same way as if violating an MPO. Military commanders, by regulation, are also encouraged to issue an MPO to support an existing CPO, or to provide some protection to a victim while the victim pursues a CPO.83 MPOs are unenforceable by civilian law enforcement. In 2008, however, Congress required the commander of a military installation to notify civilian authorities when an MPO is issued, changed, or terminated with respect to individuals who live outside of the installation.84 Procedures for coordination and information-sharing between military and local officials are established through formal memoranda of understanding (MOUs).

Expedited Transfer and Administrative Reassignments

In an effort to protect servicemembers reporting sex-related offenses from retaliation, Congress required in 2011 that DOD develop policies and procedures for consideration of station changes or unit transfers of active duty member victims who report sex-related offenses under the UCMJ.85 Per statute, an individual's commanding officer must approve or disapprove an application for transfer within 72 hours of submission. If the commander disapproves the transfer, the applicant may request review from the first general officer in the chain of command. The law requires a decision from the general officer within 72 hours of the submission of the request. Congress expanded the application of such transfer policies and procedures to cover military servicemembers who are victims of physical or sexual IPV through the FY2018 NDAA.86 The act specified that transfer policies and procedures are to be implemented once abuse has occurred, irrespective of whether the offender is a member of the Armed Forces.

In the FY2014 NDAA, Congress also added a provision that allows commanders and others with authority to reassign or remove from a position of authority individuals who are alleged to have committed or attempted sex-related offenses. The law is specific that reassignment action is "not as a punitive measure, but solely for the purpose of maintaining good order and discipline within the member's unit."87 Advocates for this provision had argued that reassignment of the victim could be seen as penalizing the victim instead of the perpetrator.88

Covered offenses under the expedited transfer (10 U.S.C. §673) and administrative reassignment (10 U.S.C. §674) authorities currently do not include the UCMJ offense for domestic violence, which was added in 2018 as part of the FY2019 NDAA (See section below on "Domestic Violence Punitive Article").89

Victim Support and Services

In the past decade, DOD has developed methods for incident reporting, data collection, and analysis of IPV trends. There is some evidence to suggest, however, that the actual prevalence of domestic abuse in the military could be underreported. While DOD conducts annual surveys of servicemembers to determine the prevalence of sexual assault and harassment in the military, it does not conduct or report on similar surveys with the military spouse population or on the prevalence of non-sex-related abuse by intimate partners. Indeed, IPV prevalence can be difficult to measure, and within the academic literature there is a broad range of prevalence estimates for victimization and perpetration involving military servicemembers. One meta-analysis undertaken by the VA suggests that among active duty servicemembers, the 12-month prevalence of IPV perpetration was 22%, and victimization was 30%—rates higher than those of actual incident reports within DOD.90 Another (nonscientific) survey conducted by a military family advocacy group in 2017 found that 15% of the military and veteran family respondents did not feel physically safe in their relationship. Among those experiencing abuse, the survey found that "87% of military spouse respondents did not report their physical abuse, citing their top two reasons for not reporting the abuse was that they felt it was not a big deal and they did not want to hurt their spouse or partner's career."91

Intimate partner abuse for the perpetrator is often connected with coercive control and monitoring of the victim's activities (e.g., controlling phone or email passwords, and restricting bank account access), and thus some victims may be fearful of seeking help. Confidentiality concerns, financial dependency, and lack of support structures can all create barriers to reporting IPV. Congress and DOD have taken some actions to try to reduce these barriers, to encourage victims to report, and to increase access to victim support services.

Confidentiality: Restricted and Unrestricted Reporting

Responding to concerns from military family members about confidentiality in reporting incidents of domestic abuse, Congress required in 1999 that DOD establish policies and procedures, which provide "maximum protection for the confidentiality of dependent communications" with service providers, such as therapists, counselors, and advocates.92 DOD has since developed distinct reporting streams that can accommodate varying levels of confidentiality. In an unrestricted reporting scenario, domestic abuse is reported to law enforcement, FAP, or the chain of command. Such a report would typically set off a sequence of actions to include a criminal investigation of the alleged offender. In some cases, a victim may be hesitant to trigger these events but may want to access support services in a confidential manner. In recognition that some victims may be deterred from reporting based on confidentiality concern, DOD has established a restricted reporting option. With some exceptions, this reporting option allows victims to disclose information to a victim advocate, victim advocate supervisor, or healthcare provider without that information being disclosed to other authorities.93 The restricted reporting options allows the victim time to access medical care, counseling, and victim advocacy services while providing some time to consider relationship choices and next steps.

|

Whom to Call for Victims of Abuse Military-connected victims of domestic abuse may contact the local Family Advocacy Program94 or call the 24/7 National Domestic Abuse Hotline at 800-799-SAFE (7233). Those in immediate danger of assault or physical injury should call 911. Those on a military installation, may also call their military law enforcement office. |

Victim Advocacy Services

In 2003, as part of the FY2004 NDAA, Congress called for the development of a Victim Advocate Protocol for victims of Domestic Violence.95 Among other things, the Protocol requires victims of domestic abuse be notified of victim advocacy services and be provided access to those services 24 hours a day (either in person or by phone).96 Victim advocates play a substantial role in supporting the victim following a domestic violence incident. They help victims and other at-risk family members by developing a safety plan,97 referring them to ongoing care through military or civilian providers, and providing information on other resources (e.g., chaplain or legal services, transitional compensation).98 Victim advocates can be DOD employees, military contractors, or other civilian providers.

Special Victims' Counsel/Victims' Legal Counsel

A Special Victims' Counsel (SVC) or Victims' Legal Counsel (VLC) is a judge advocate or civilian attorney who satisfies special training requirements and is authorized to provide legal assistance to victims of sexual assault throughout the military justice process.99 Currently SVC/VLC services are not authorized for victims of domestic violence; however, recent legislative proposals have sought to expand such services to this population. A provision in the FY2019 NDAA required DOD to submit a report on feasibility and advisability of expanding SVC/VLC eligibility to victims of domestic violence and asked for an analysis of personnel authorizations with respect to the current case workload. DOD found that expanding this eligibility to domestic violence victims would "significantly increase the caseload of SVC/VLC programs across the board."100 If SVC/VLC support were made available to victims of domestic violence, each of the military services "would require additional SVC/VLC authorizations and sufficient time to train personnel to implement new mission requirements."101

Transitional Compensation

Some spouses are wholly or highly financially dependent on their military intimate partner, possibly discouraging some victims from reporting IPV. Therefore, the prospect of the member being incarcerated or discharged from the military can provide a disincentive for an abused spouse to seek help. In a 1993 House Armed Services hearing on Victims' Rights, the Ranking Member noted that "with few exceptions, when a military member is incarcerated because of violence or abuse, the family is cut loose by DOD and left without medical coverage, without counseling, without housing, without the support of the military community."102

Congress sought to redress this disincentive to reporting through the FY1994 NDAA, which authorized the temporary provision of monetary benefits, called transitional compensation, to dependents of servicemembers or former servicemembers who were separated from the military due to IPV.103 One of the motivating arguments for establishing the transitional compensation benefit was that it could provide a measure of financial security to spouses or former spouses. The provision was codified in 10 U.S.C. §1059 and applies to cases involving members who, on or after November 30, 1993 are

- separated from active duty under a court-martial sentence resulting from a dependent-abuse offense,

- separated from active duty for administrative reasons if the basis for separation includes a dependent-abuse offense, or

- sentenced to forfeiture of all pay and allowances by a court-martial that has convicted the member of a dependent-abuse offense.

Transitional compensation payments are exempt from federal taxation, provided at the dependency and indemnity compensation (DIC) rate, and authorized for at least 12 months but no more than 36 months.104 For individuals to be eligible, they must be current or former dependents of servicemembers, including spouses, former spouses, or dependent children.105 Intimate partners who are not or were never married to servicemembers are generally ineligible to receive compensation from DOD. While in receipt of transitional compensation, dependents are also entitled to military commissary and exchange benefits, and may receive dental and medical care, including mental health services, through military facilities as TRICARE beneficiaries.106

Forfeiture and/or Coordination of Benefits

Recipients of transitional compensation benefits must certify eligibility on an annual basis to retain payments. In addition, payments will cease if the eligible spouse or former spouse

- remarries, on the date of remarriage,

- cohabitates with the servicemember after punitive or other adverse action has been executed, or

- is found to have been an active participant in the conduct constituting the criminal offense, or actively aided or abetted the member in such conduct against a dependent child.107

Payments may also cease if a court-martial sentence is remitted, set aside, or mitigated to a lesser punishment. Spouses or former spouses may not receive both transitional compensation and court-ordered payments of retired pay and must elect to receive one or the other of those benefits, if applicable.108

Access to Retired Pay and Benefits

A military servicemember typically becomes eligible for a pension from the federal government after 20 years of service.109 Under the Uniformed Services Former Spouses Protection Act (USFSPA), up to 50% of the member's disposable military retired pay may be awarded by court order to a former spouse in a divorce settlement.110 In some cases, a member may be eligible for retired pay by virtue of longevity in service; however, punitive actions in response to member misconduct may terminate eligibility for retired pay. In 1992, Congress authorized the military departments to make court-ordered payments of an amount of disposable retired pay to abused spouses or former spouses in cases where the member has eligibility to receive retired pay terminated due to misconduct related to the abuse.111 So, for example, if a retired member, through court martial sentencing as a result of a domestic violence offense, becomes ineligible to receive retired pay, the Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS) may still pay a court-ordered portion of what the member might otherwise be eligible for, to the member's spouse or former spouse. A spouse or former spouse, while receiving payments under this chapter, is also eligible to receive any other benefits a spouse or former spouse of a retired member may be entitled, including medical and dental care, commissary and exchange privileges, and the Survivor Benefit Plan.112

Emergency Housing and Accommodations

In situations where a servicemember is the perpetrator of violence, the commanding officer may restrict that individual to the barracks, ship, or other installation housing and issue MPOs (as discussed in section "Military Protective Orders". The primary objective is typically to remove the offender from the home, to protect the victim. On the other hand, there may be scenarios where commanders have less control over housing of the perpetrator (e.g., in the case where the offender is a civilian living outside an installation). In such cases, DOD policies also require that victim advocates facilitate provision of shelter and safe housing resources for victims.113 According to the services, commanders typically draw on a number of housing options on the installation (e.g., temporary lodging) or in the local civilian community (e.g., shelters, hotels, etc.).

Relocation Benefits

Military families move frequently to different assignments worldwide, often far away from family and support networks. Moving expenses for the family under a member's orders are paid by the Department of Defense. Generally, civilian spouses are only eligible for these benefits when the family moves together under the military sponsor's orders. For some abused spouses, it may be prohibitively expensive to independently execute a household move following a domestic abuse incident, particularly for those accompanying servicemembers stationed overseas. In 2003, as part of the FY2004 NDAA, Congress added a provision that allows for certain travel and transportation benefits for dependents who are victims of domestic abuse in the absence of military orders for a permanent change of station move.114 When relocation is advisable to ensure the safety of the victim, the Secretary of the military department concerned may authorize movement of household effects and baggage at the government's expense, plus travel per diem paid to the dependent. The authorization for these benefits allows for a move to an appropriate location in the United States or its possessions, or if the abused dependent is a foreign national, to their country of national origin.

Federal Crime Victims Fund

In 1984, the Crime Victims Fund (CVF, or the Fund) was established by the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA, P.L. 98-473) to provide funding for state victim compensation and assistance programs.115 The CVF does not receive appropriated funding.116 Rather, deposits to the CVF come from a number of sources including criminal fines,117 forfeited bail bonds, penalties, and special assessments collected by the U.S. Attorneys' Offices, federal courts, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons from offenders convicted of federal crimes.118 The largest source of deposits into the CVF is criminal fines.119 U.S. military servicemembers and their families are eligible for these victim assistance and compensation programs.

The Office for Victims of Crime (OVC) within the Department of Justice (DOJ) administers the CVF.120 As authorized by VOCA, the OVC awards CVF money through formula and discretionary grants to states, local units of government, individuals, and other entities.121 Grants are allocated according to VOCA statute, and most of the annual funding goes toward the two VOCA formula grants: the victim compensation formula grant and victim assistance programs. The grants are distributed to states and territories according to guidelines established by VOCA.122

Victim compensation formula grants may be used to reimburse crime victims for out-of-pocket expenses such as medical and mental health counseling expenses, lost wages, funeral and burial costs, and other costs (except property loss)123 authorized in a state's compensation statute. Victims are reimbursed for crime-related expenses that are not covered by other resources, such as private insurance. Since FY1999, medical and dental services have accounted for close to half of the total payout in annual compensation expenses.124 In FY2017, "the vast majority of applications related to a victimization (52,461 or 96%) were related to domestic and family violence."125

Victim assistance formula grants support a number of services for crime victims, including the provision of information and referral services, crisis counseling, temporary housing, and criminal justice advocacy support. States are required to prioritize the following groups: (1) underserved populations of victims of violent crime,126 (2) victims of child abuse, (3) victims of sexual assault, and (4) victims of spouse abuse.127 States may not use federal funds to supplant state and local funds otherwise available for crime victim assistance. According to the OVC, victims of domestic violence make up the largest number of victims receiving services under the victim assistance formula grant program. In FY2017, over five million crime victims were served by these grants, 43% of whom were victims of domestic and/or family violence.128

Military Law Enforcement Response

DOD and the Services have a general framework under the UCMJ, and other laws, for responding to violent offenses.129 DOD domestic abuse policies superimpose specific requirements onto this framework. Among other things, DOD policy states commanders are required to respond to reports of domestic abuse in the same manner as they would to credible reports of any other crime and must ensure that military service offenders are held accountable for acts of domestic violence through appropriate disposition under the UCMJ.130 Similarly, law enforcement and military criminal investigation personnel are required to investigate reports of domestic violence and respond to them as they would to credible reports of any other crime.131

In 1993, as part of the FY1994 NDAA, Congress specified certain responsibilities for military law enforcement officials in response to domestic violence. In particular, the law requires that in cases where there is evidence of physical injury, or where a deadly weapon or dangerous instrument has been used, officials must report the incident within 24 hours to the appropriate commander and to a local FAP representative.132 Military law enforcement includes both installation law enforcement (ILE), MCIOs, and the Defense Criminal Investigative Service (DCIS), which is an arm of the DOD Inspector General. The term defense criminal investigative organization (DCIO) is used to describe the military criminal investigative organizations and DCIS. Current DOD policy requires that either a MCIO or another appropriate law enforcement organization investigate domestic violence and specifies that MCIOs are to investigate all unrestricted reports of domestic violence involving sexual assault or aggravated assault with grievous bodily harm.133

|

Military Law Enforcement Organizations To fully understand which law enforcement organization is responsible for investigating domestic violence, it is helpful to distinguish between installation law enforcement (ILE) and MCIO. These organizations have different levels of responsibility for investigating crimes and corresponding levels of proficiency. Military Criminal Investigative Organization (MCIO) An MCIO is composed of servicemembers or civilians who are military department criminal investigators (special agents). MCIOs include the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command (USACIDC), the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), and the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI). A typical MCIO special agent must be 21 or older, have at least two years of military service, have a minimum of 60 college semester hours, and have a minimum General Technical (GT) score of 110 (the same minimum score required for commissioned officers in the Army); and have successfully completed a special agent course accredited by the Federal Law Enforcement Training Accreditation Board (typical course length is 15 weeks. )134 They have general jurisdiction over offenses under the UCMJ. MCIO personnel are under the control and supervision of the military department's provost marshal.135 An MCIO investigates serious offenses analogous to felonies and is expressly responsible for investigating all sexual assault offenses under the UCMJ.136 Installation Law Enforcement (ILE) ILE is made up of servicemembers or civilians who are military installation police or police investigators whose jurisdiction is limited to military installations. ILE includes U.S. Army Military Police, Naval Security Forces, Air Force Security Forces, and U.S. Marine Corps Military Police. ILE personnel are under the control and supervision of an installation provost marshal or equivalent official. ILE investigates incidents that do not fall within a MCIO's jurisdiction, namely, minor military offenses and offenses analogous to a misdemeanor.137 ILE are responsible for investigating offenses under Article 128 (Assault) with a maximum punishment that is less than one year. |

DODIG Review of Law Enforcement Actions

A 2019 report by the Department of Defense Inspector General (DODIG) found that law enforcement response actions were generally consistent with DOD policies; however, the DODIG noted DCIOs did not consistently comply with DOD policies when responding to nonsexual domestic violence incidents involving adult victims (see Table 5).138 In particular, the audit revealed that responders often did not have necessary equipment for collecting and preserving evidence and that incident reports did not get proper supervisory review. In 22% of the reviewed cases law enforcement failed to report the incident to the FAP and in 82% of those cases failed to submit criminal history data to the Defense Central Index of Investigations (DCII), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Criminal Justice Information Services Division (CJIS), and the Defense Forensics Science Center. (See discussion below under "Crime Reporting to National Databases.")139

|

Category for Noncompliance |

Total |

Army |

Navy |

Marine Corps |

NCIS |

Air Force |

|

Crime scene search not conducted |

33% |

50% |

56% |

24% |

5% |

35% |

|

Required evidence not collected |

8% |

5% |

0% |

6% |

0% |

29% |

|

Required photographs not taken |

92% |

100% |

100% |

88% |

58% |

100% |

|

Interviews not conducted |

27% |

37% |

21% |

22% |

17% |

24% |

|

Interviews not thorough |

54% |

71% |

64% |

27% |

25% |

87% |

|

FAP not notified |

24% |

31% |

42% |

12% |

0% |

38% |

|

Subjects not indexed in DCII |

55% |

59% |

100% |

62% |

17% |

34% |

|

Fingerprint cards not submitted as required |

71% |

94% |

100% |

41% |

18% |

94% |

|

Final disposition reports not submitted as required |

76% |

98% |

100% |

51% |

24% |

94% |

|

DNA sample not submitted as required |

55% |

42% |

100% |

46% |

6% |

97% |

Source: Table derived from DODIG, Evaluation of Military Services' Law Enforcement Responses to Domestic Violence Incidents, DODIG -2019-075, April 19, 2019.

Notes: Noncompliance rates are based on a sample of 219 of the 956 incident responses that were reported between October 1, 2014, and September 30, 2016. NCIS is the Naval Criminal Investigative Service. While the Navy had the highest non-compliance rates, they also had the smallest sample of incidents (18 total).

In general, actions by the Navy Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS)—the only MCIO included in the IG report—were more likely to be in compliance than those by military law enforcement.140 In the report, the Army and the Air Force do not distinguish between ILEs and MCIOs, and relevant criminal investigation jurisdiction policies for these military services show that their MCIOs do not have responsibility for investigating domestic violence.141 Presumably, with the exception of the NCIS data, all other data in the table are based on ILE responses to domestic violence incidents. Among other things, the DOD IG found that military service law enforcement organizations, largely ILE, did not consistently comply with DOD policies when responding to nonsexual domestic violence incidents involving adult victims.142 The IG findings and the data in the table appear to suggest that ILE are less proficient at domestic violence responses and investigations, whereas an MCIO, using NCIS as the sole example, is more proficient at responding to them.

Crime Reporting to National Databases

Law and policy require military law enforcement to provide certain crime reports to DOD and national crime databases throughout a criminal investigation of a servicemember. The Services are required to maintain automated information systems that comply with the Defense Incident-Based Reporting System (DIBRS), which complies with the FBI National Law Enforcement Data Exchange (N-DEx) System.143 The FBI's N-DEx system is a repository of criminal justice records and data from law enforcement agencies in the United States and it is managed by the FBI's Criminal Justice Information Service (CJIS).

DIBRS captures criminal incidents of domestic violence that are reported to law enforcement in compliance with the following laws144;

- The Uniform Federal Crime Reporting Act of 1988,145

- The Victims' Rights and Restitution Act of 1990,146

- The Lautenberg Amendment to the Gun Control Act,147 and

- The Jacob Wetterling, Megan Nicole Kanka, and Pam Lychner Sex Offender Registration and Notification Program.148

DIBRS data is subsequently reported to the Federal Bureau of Investigation's National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS).149 As repository for federal and state crime activity, NIBRS data is used for analyzing crime trends and developing policy approaches to reduce criminal activity.150

Specific records of investigations are located in the Defense Central Index of Investigations (DCII), an automated central index that identifies investigations conducted by DOD investigative agencies. DCII is typically used by DOD security and investigative agencies and other federal agencies to determine security clearance status and the physical location of criminal and personnel security investigative files.151

Per DOD policy for collating investigation data, MCIOs are responsible for

- Titling and indexing subjects of criminal investigations in the DCII when there is credible information that a subject of an investigation committed a criminal offense (under the UCMJ or any other federal criminal statute).152

- Reporting disposition information within 15 days of final disposition of military judicial or nonjudicial proceedings; approval of a request for discharge, retirement, or resignation in lieu of court-martial; or, discharge resulting from anything other than honorable characterization of service based on investigations UCMJ violations.153

- Submitting fingerprint cards and final disposition of investigations to the FBI CJIS regarding servicemembers investigated for violating an offense under the UCMJ, based on probable cause.154

|

Crime Data Reporting Failure: the Devin Kelley Case While crime data reporting procedures are in place, a single instance of noncompliance can result in severe harm. In November 2017, a former member of the U.S. Air Force entered the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, and shot and killed 26 people using a weapon he purchased from a licensed firearms dealer. The former member, Devin Kelley, had been convicted by general court-martial for a felony-level domestic violence offense stemming from an assault on his wife and stepson.155 He was sentenced to confinement and given a bad conduct discharge from the Air Force.156 Under existing law and policy at the time, Kelley should have been prohibited from purchasing a weapon from a licensed federal firearm dealer. However, on six separate occasions, Kelley was able to purchase firearms from stores that were Federal Firearms Licensees and completed the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives Form 4473, which is required to obtain a firearm license.157 A subsequent report by the DOD Inspector General (DODIG) found that after Kelley's court martial conviction, the Air Force failed to submit his fingerprints and final disposition report to the FBI's Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division for inclusion in its databases as required by DOD and Air Force policy. In particular, the DODIG found that the Air Force missed four opportunities in the course of the investigation, prosecution, and incarceration of Kelley to submit his fingerprints to the FBI and two opportunities to submit final disposition information.158 In 2019, the Air Force launched a modernized criminal data reporting system, called the Air Force Justice Information System, to provide a "centralized hub of criminal data reporting, automatic flagging of federally reporting of offenses, providing installation breech tracking and criminal data reporting trends and analytics that allow for predictive analytics."159 |

Military Justice System

While some domestic violence offenders in the military may be subject to local or host nation jurisdiction, active duty servicemembers worldwide may be held accountable for domestic violence offenses under the military justice system. The military justice system is established in Title 10 of the United States Code and is separate from and independent of the federal criminal justice system established in Title 28.160 Congress enacts this authority through the articles (statutes) that make up the UCMJ, under Chapter 47, of Title 10, U.S. Code.161 The President implements the UCMJ by executive order through the Manual for Courts-Martial (MCM).162 The MCM establishes detailed rules for administering justice.163Among other things, The MCM contains the major components of military justice:

- Jurisdiction—Court-Martial Convening Authority for the three levels of courts-martial and the jurisdiction of each one (chapter II, part II, MCM).

- Criminal Procedure Code—Rules for Courts-martial provide for the administration of military justice (chapters III – XIII, part II, MCM).

- Rules of Evidence—Military Rules or Evidence established the evidential procedure for judicial proceedings at a court-martial (part III, MCM).

- Criminal Code—Punitive Articles in the UCMJ criminalize specific conduct (part IV, MCM).

The MCM also includes the procedure for nonjudicial punishment (NJP) and maximum punishment information for each punitive article.164

Commander's Authority

The authority to prosecute or refer charges to court martial falls within the jurisdiction of a command and its commander.165 Commanders at every level are responsible for deciding whether to take action regarding misconduct occurring in a command over which they have authority.166 When addressing misconduct, a commander acts as an adjudicator of first instance to determine whether misconduct warrants disposition in a judicial, nonjudicial, or administrative process.167 A commander can also determine to take no action against an offender. These determinations are known as disposition decisions. They are made at the lowest level of command with direct authority over an offender, unless disposition authority is withheld by a higher-level commander.

DOD requires all commanders to refer allegations of domestic violence by a victim, or credible reports of domestic violence by a third party, to an appropriate law enforcement organization.168 Law enforcement personnel must promptly complete a detailed written report of the investigation and forward it to the alleged offender's commander.169 The commander must then review the report and obtain advice from an appropriate legal officer before determining disposition.170

Court-Martial

Upon review of the investigative report, the commander may refer the case to court-martial for trial. There are three courts-martial levels with jurisdiction over UCMJ offences.171 The first two levels—summary and special courts-martial—are courts of limited jurisdiction (minor and misdemeanor offenses).172 The third and highest level—general court-martial—is a court of general jurisdiction (felony offenses).173 A general court-marital can impose the maximum punishment prescribed for a crime in the UCMJ.174 A trial by general court-martial typically consists of a military judge, prosecutor, defense counsel, and members.175 The members are a panel of servicemembers who can render guilty or not guilty verdicts, like a civilian jury, and make sentencing decisions, unlike a civilian jury.176

Domestic Violence Punitive Article

The punitive articles in the UCMJ are the offenses that fall within the jurisdiction of a court-martial.177 Prior to 2019, domestic violence offenses were typically prosecuted under the general offense of assault under Article 128 (Assault).178 Congress amended the UCMJ in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 by adding a specific punitive article for domestic violence—Article 128b—effective on January 1, 2019.179 This punitive article prescribes punishment, as a court-martial may direct, for any person subject to UCMJ jurisdiction who:

(1) commits a violent offense against a spouse, an intimate partner, or an immediate family member of that person;

(2) with intent to threaten or intimidate a spouse, an intimate partner, or an immediate family member of that person-

(A) commits an offense under [the UCMJ] against any person; or

(B) commits an offense under [the UCMJ] against any property, including an animal;

(3) with intent to threaten or intimidate a spouse, an intimate partner, or an immediate family member of that person, violates a protection order;

(4) with intent to commit a violent offense against a spouse, an intimate partner, or an immediate family member of that person, violates a protection order; or

(5) assaults a spouse, an intimate partner, or an immediate family member of that person by strangling or suffocating;180

Article 128b generally requires a threat or violent offense or the specific act of strangulation or suffocation to trigger the UCMJ. Research has found that strangulation is an associated risk factor for intimate partner homicide of female victims.181

Sentencing

After a guilty verdict or plea, and without delay, a court-martial imposes a sentence that is within its authority and discretion.182 Specific punishments for UCMJ offenses tried by a court-martial are reprimand; forfeiture of pay and allowances; fine; reduction in pay grade; restriction to specified limits; hard labor without confinement; confinement; punitive separation; and death.183 A single punitive article can include a range of offenses from minor to serious; the maximum punishment increases as the severity of the offense increases.

As noted above, domestic violence was previously included in the general assault article (Article 128) before it became a nominative offense under Article 128b.184 Punishment under Article 128 includes a maximum punishment as low as three months for simple assault and a maximum punishment as high as dishonorable or bad conduct discharge, total forfeitures, and 20 years' confinement, for assault with intent to commit specified offenses, such as murder, rape, and rape of a child.185 Domestic violence was distinguishable from other types of assault under Article 128 (Assault) by the greater severity of its punishment.186 DOD has not yet amended the most recent MCM issued in 2019 to include a maximum punishment for Article 128b (Domestic Violence), which became law around the time DOD issued the 2019 MCM.

Military Rules of Evidence

The Military Rules of Evidence (MRE) are established by executive order as part of the Manual for Courts-Martial.187 They are analogous to civilian rules of evidence, particularly the Federal Rules of Evidence.188 There are two rules within the MRE that specifically apply to domestic violence (i.e., privileged conversations with victim advocates, and testimony of children who witness an event).

Victim Advocate—Victim Privilege

A victim who has suffered direct physical or emotional harm as the result of a sexual or violent offense has a privilege to refuse to disclose, and to prevent any other person from disclosing, a confidential communication made between the alleged victim and a victim advocate, or between the alleged victim and DOD Safe Helpline staff.189 The communication must have been made for the purpose of facilitating advice or assistance to the victim.190 A victim advocate is a person, other than a trial counsel, any victims' counsel, law enforcement officer, or military criminal investigator in the case, who is appropriately designated as such.191

Remote Live Testimony of a Child

If a child is a victim or witness of domestic violence, a military judge must allow remote live testimony if the judge finds on the record that

It is necessary to protect the welfare of the particular child witness;

The child witness would be traumatized, not by the courtroom generally, but by the presence of the accused; and,

The emotional distress suffered by the child witness in the presence of the accused is more than slight.192