Introduction

The Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) is one of the most-tracked single accounts funded by Congress each year. Managed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), it is the primary source of funding for the federal government's domestic general disaster relief programs. These programs, authorized under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, as amended (42 U.S.C. 5121 et seq.), outline the federal role in supporting state, local, tribal, and territorial governments as they respond to and recover from a variety of incidents. They take effect in the event that nonfederal levels of government find their own capacity to deal with an incident is overwhelmed.

The current environment for emergency management policy assumes this federal role in domestic disaster relief as the default position and the availability of resources through the DRF a necessary requirement. However, this was not always the case. The concept of general disaster relief provided by the federal government predates both FEMA and the Stafford Act, but federal involvement in relief after natural and man-made disasters was very rare before the Civil War, and was at times considered unconstitutional. Domestic disaster relief efforts became more common after the Civil War, but were not seen as a necessary obligation of the federal government. Standing federal domestic disaster relief programs and a pool of resources to fund them only emerged after the Second World War. Prior to the development of these programs, domestic disaster relief and recovery was a matter for private nongovernmental organizations and state and local governments.

Once established, the federal role in domestic disaster response and recovery grew, proving politically popular and resilient despite periodic concerns about management, execution, and budgetary impacts. The DRF is the source of funding for most general disaster relief programs, so it is an indicator of the scope of those programs and the volume of taxpayer-funded aid they provide. Understanding the trends in the growth of the federal government's role in general disaster relief and recovery, and the associated costs of that role, may be useful as Congress considers changes in both emergency management and budgetary policies.

This report introduces the DRF and provides a brief history of federal disaster relief programs. It goes on to discuss the appropriations that fund the DRF, and provides a funding history from FY1964 to the present day, discussing factors that contributed to those changing appropriations levels. It concludes with discussion of how the budget request for the DRF has been developed and structured, given the unpredictability of the annual budgetary impact of disasters, and raises some potential issues for congressional consideration.

What is the Disaster Relief Fund and how is it used?

The DRF is the primary source of funding for the federal government's general disaster relief program—response and recovery efforts pursuant to a range of domestic emergencies and disasters in existing law—as opposed to specific relief and recovery initiatives that may be enacted for individual incidents.

What determines whether an incident qualifies as an emergency or disaster?

Under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (P.L. 93-288, as amended; hereinafter "the Stafford Act"), the President can declare that an emergency exists or a major disaster is occurring.1 These declarations make state, tribal, territorial, and local governments2 eligible for a variety of assistance programs, many of which are funded from the DRF.3 Declarations usually are made at the request of a state, tribal, or territorial government.

Does all federally funded disaster relief come from the DRF?

While the DRF funds Stafford Act disaster relief and recovery programs, several other federal departments and agencies have significant roles in disaster preparedness, relief, recovery, and mitigation. These include the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Small Business Administration, U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the Department of Health and Human Services. While FEMA may fund some of their activities out of the DRF through mission assignments, their broader disaster-related programs are funded through separate appropriations.4

What federal government activities are funded under the DRF?

Currently, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) coordinates federal disaster response and recovery efforts, and manages the DRF, which funds activities in five categories:

- 1. Activity pursuant to a major disaster declaration—This activity represents the vast majority of spending from the DRF. FEMA's primary "Direct Disaster Programs" are the Individual Assistance (IA),5 Public Assistance (PA),6 and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) programs.7 Federal assistance provided by other federal agencies at FEMA's direction through "mission assignments" is also paid for from the DRF.8

- 2. Predeclaration surge activities—These are activities undertaken prior to an emergency or major disaster declaration to prepare for response and recovery, such as deploying response teams or prepositioning equipment.

- 3. Activity pursuant to an emergency declaration—This is federal assistance to supplement state and local efforts in providing emergency services in any part of the United States.

- 4. Fire Management Assistance Grants (FMAGs) for large wildfires—This is assistance for the mitigation, management, and control of any fires on public or private lands that could, if unchecked, worsen and result in a major disaster declaration.9

- 5. Disaster Readiness and Support (DRS) activities—These are ongoing, non-incident specific activities that allow FEMA to provide timely disaster response, operate its programs responsively and effectively, and provide oversight of its emergency and disaster programs.

The role of the federal government has evolved over the years, but emergency response and disaster relief has historically been a federalized "bottom-up" operation, starting from the local or tribal governments affected, backed up by the state or territorial government,10 and then turning to the federal government if their capacity is overwhelmed. The broadening of the federal role has been a factor in which activities are funded under the DRF.

|

DRF Activities and Statutory Budget Controls Implementation of budget controls in 2011 led to changes in the way DRF appropriations were structured to support Stafford Act activities. Since FY2012, the first fiscal year of statutory limits on discretionary spending under the Budget Control Act (BCA), a distinction has been made between budget authority for the activities pursuant to a specific major disaster declaration—the first of the activities listed above—and budget authority for other activities. The former now often carries a special "disaster relief" designation, defining it as being provided pursuant to a major disaster declaration under the Stafford Act, and triggering an adjustment in discretionary spending limits to accommodate it. Budget authority for the other four activities, covering other Stafford Act functions not linked to response and recovery from a specific major disaster, is derived from the undesignated portion, referred to as the "base." This remaining budget authority is counted against discretionary spending limits. There is no restriction on budget authority from the "base" being used for the costs of specific major disasters. During catastrophic disasters funds have been transferred from the base to the major disaster category, and back again once that category was replenished. The statutory discretionary budget limits laid out in the BCA and the disaster relief adjustment mechanisms will expire after FY2021 under current law. |

Under what statute is the Disaster Relief Fund authorized?

The DRF is not separately authorized as a distinct entity, but the activities it funds are authorized under the Stafford Act (42 U.S.C. 5121 et seq.).

Where are appropriations for the Disaster Relief Fund provided?

Since FY1980—FEMA's first annual appropriation—the DRF has been funded through its own appropriation within FEMA's budget, first under the heading "Disaster Relief," and then "Disaster Relief Fund" starting in FY2012. FEMA's annual appropriations were first provided through the VA, HUD, and Independent Agencies Appropriations Act, but have been included in the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations act since FY2004. Since the first "Disaster Relief" appropriation for FY1948, most of the DRF's appropriations have been provided through supplemental appropriations. See Figure 1 and Figure 2 for details.

Are specific Disaster Relief Fund appropriations for specific disasters?

DRF appropriations have historically been provided for general disaster relief, rather than specific presidentially declared disasters or emergencies.

The most recent iterations of the appropriations bill text indicate the funds are provided for the "necessary expenses in carrying out the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act," thus covering all past and future disaster and emergency declarations.11 Previous versions of the appropriations language going back to 1950 also referenced the legislation authorizing general disaster relief rather than targeting specific disasters. On a number of occasions, specific disasters have been mentioned in the appropriation, but funding was not specifically directed to one disaster over others.

While many disaster supplemental appropriations bills are associated with a specific incident or incidents—such as P.L. 113-2, "the Sandy Supplemental"—the language in that act does not limit the use of the disaster relief appropriation to that specific incident.12

How is the DRF being spent?

Since the enactment of P.L. 112-74, Congress has received regular reporting on spending from the DRF. Monthly reports on such spending since March 2013 are available on FEMA's website.13 Currently, the reports include information on DRF balances, actual and projected obligations from the DRF for large-scale disasters broken down by disaster declaration, and obligations and expenditures aggregated by incident. These reports also include estimates of the DRF balance through the end of the current fiscal year.

Historical Context for Federal Disaster Relief Funding

Disaster relief has not always been a part of the mission of the federal government. For nearly 80 years, federal domestic disaster relief was minimal, extremely narrow in scope, and largely did not address the humanitarian side of the relief equation, leaving that to private organizations and local levels of government. Even as the country emerged from the Civil War with more of a national identity and a sense that the federal government could act to provide relief in some circumstances, disaster aid remained limited, responding only after the fact on a case-by-case basis. Only after World War II did the concept emerge of a federal role in responding to disasters broadly defined, led by the President and funded in advance, as opposed to case-by-case responses to needs in the wake of the most severe events led by ad hoc congressional action. Over the ensuing years, the general disaster relief program and its funding grew, adopting concepts of assistance that once had been reserved for catastrophic events to respond to more common natural disasters. In the 1970s, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) was established, institutionalizing the federal role in disaster response, recovery, mitigation, and preparedness—the role we recognize today. At the heart of that role is the set of relief programs that have evolved since the 1940s, known collectively as the Stafford Act, which are funded by the Disaster Relief Fund appropriation.

1789-1947: Case by Case, After the Fact

The Constitution provides little specific direction on the question of how the United States should confront disasters. While allusions to the intent of the Constitution speak to promoting domestic tranquility and promoting the general welfare, limitations on the federal role in state affairs combined with practical politics of the day to limit federal involvement in disaster relief and recovery in the early years of the country.

The federal government did provide disaster relief on some occasions. Some observers note at least 128 instances from 1803 to 1947 when natural disasters prompted the federal government to provide some type of ad hoc relief on a case-by-case basis for specific incidents after they occurred.14 Prior to the Civil War, these measures largely consisted of refunds of duties paid on goods destroyed in customs house fires, allowance for delayed payments of bonds, and land grants for resettlement.15

Proponents of disaster relief argued that the "general welfare" clause of the Constitution warranted the federal role in disaster relief.16 Opponents did not find this justification convincing, as it was nonspecific,17 and argued that certain natural disasters (such as flooding of the Mississippi River) were foreseeable, and therefore state and local governments had an obligation to be prepared.18 They also contended that it was improper for the government to provide relief for specific places with money it collected for the common good;19 and that the federal government could not afford to provide universal relief.

As the U.S. economy became more robust, federal revenues grew, weakening the position of those in Congress who opposed a federal role in disaster assistance on the basis of the lack of such resources.

Congressional willingness to provide assistance was not always sufficient to ensure its provision, however. In 1887, President Grover Cleveland vetoed a bill that would have provided $10,000 to pay for seeds for farmers in Texas after a drought, arguing as follows:

I can find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution; and I do not believe that the power and duty of the General Government ought to be extended to the relief of individual suffering which is in no manner properly related to the public service or benefit. A prevalent tendency to disregard the limited mission of this power and duty should, I think, be steadfastly resisted, to the end that the lesson should be constantly enforced that though the people support the Government, the Government should not support the people.

The friendliness and charity of our countrymen can always be relied upon to relieve their fellow-citizens in misfortune. This has been repeatedly and quite lately demonstrated. Federal aid in such cases encourages the expectation of paternal care on the part of the Government and weakens the sturdiness of our national character, while it prevents the indulgence among our people of that kindly sentiment and conduct which strengthens the bonds of a common brotherhood.20

Much of the disaster relief provided in this period was nongovernmental in nature. In 1881, Clara Barton founded the American National Red Cross (ANRC),21 which provided disaster aid from funds it raised from private sources. One year before a catastrophic earthquake struck San Francisco in 1906, the incorporating legislation for the ANRC was revised to task the organization with "mitigating the sufferings caused by pestilence, famine, fire, floods, and other great national calamities, and to devise and carry on measures for preventing the same."22 In the days after the earthquake, President Theodore Roosevelt issued an appeal for assistance from the public for the ANRC's relief efforts:

In the face of so horrible and appalling a national calamity as that which has befallen San Francisco, the outpouring of the nation's aid should, as far as possible, be entrusted to the American Red Cross, the national organization best fitted to undertake such relief work.... In order that this work may be well systematized and in order that the contributions, which I am sure will flow in with lavish generosity, may be wisely administered, I appeal to the people of the United States, to all cities, chambers of commerce, boards of trade, relief committees and individuals to express their sympathy and render their aid by contributions to the American Red Cross.23

While the federal government provided assistance in response and recovery in the San Francisco case on an ad hoc basis, the majority of the assistance provided was through private means. Congress appropriated $2.5 million in the days after the quake for the Secretary of War to provide "subsistence and quartermaster's supplies ... to such destitute persons as have been rendered homeless or are in needy circumstances as a result of the earthquake and commissary stores to such injured and destitute persons as may require assistance,"24 but nonfederal cash contributions to the ANRC and the local relief organizations exceeded $9 million in the two years following the disaster.25

The ANRC served as the major institutional source of relief for disaster victims in the United States, serving communities and individuals in cooperation with state and local governments with relatively little direct contributions from the federal government for many years. The Red Cross continued to play a leading role in nongovernmental disaster relief as the federal government's role in disaster aid evolved and expanded through the 20th century and into the 21st.

1947-1950: General Disaster Relief Funding from the Federal Government Begins

After the Second World War, the federal government started becoming more involved in disaster relief beyond specific incident-by-incident relief efforts. In 1947, P.L. 80-233 authorized the federal government to provide surplus property to state and local governments for disaster relief under the Disaster Surplus Property Program. Less than eight months later, the Administrator of the Federal Works Agency noted in a letter to President Harry S. Truman that the program would not provide adequate relief to communities over the longer term.

The next year, Congress made its first appropriation for general disaster relief. The Second Deficiency Appropriation Act, 1948,26 which was enacted on June 25, 1948, provided funding directly to the President as follows:

DISASTER RELIEF

Disaster Relief: To enable the President, through such agency or agencies as he may designate, and in such manner as he shall determine, to supplement the efforts and available resources of State and local governments or other agencies, whenever he finds that any flood, fire, hurricane, earthquake, or other catastrophe in any part of the United States is of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant emergency assistance by the Federal Government in alleviating hardship, or suffering caused thereby, and if the governor of any State in which such catastrophe shall occur shall certify that such assistance is required, $500,000, to remain available until June 30, 1949, and to be expended without regard to such provisions regulating the expenditure of Government funds or the employment of persons in the Government service as he shall specify: Provided, That no expenditures shall be made with respect to any such catastrophe in any State until the governor of such State shall have entered into an agreement with such agency of the Government as the President may designate giving assurance of expenditure of a reasonable amount of the funds of the government of such State, local governments therein, or other agencies, for the same or similar purposes with respect to such catastrophe: Provided further, That no part of this appropriation shall be expended for departmental personal services: Provided further, That no part of this appropriation shall be expended for permanent construction: Provided further, That within any affected area Federal agencies are authorized to participate in any such emergency assistance.27

Although this legislation comes with broad latitude for the President in expending these funds, this appropriation contained several hallmarks that continue in today's disaster relief structure:

- the President makes the determination that a disaster has occurred, and that federal aid is required;

- the state has a role in certifying the need and committing state resources to be eligible for federal support;

- aid is to "supplement the efforts and available resources of State and local governments or other agencies," rather than to fund the entire relief effort; and

- the President may direct federal agencies to participate in emergency assistance.

The conditions laid out in this appropriation were echoed in the next two appropriations, provided in 1949, which totaled $1 million.28

1950-1966: The Disaster Relief Act of 1950—General Relief and Specific Relief

The Disaster Relief Act of 1950 formalized the structure outlined in the initial appropriations legislation, and indicated for the first time that

it is the intent of Congress to provide an orderly and continuing means of assistance by the Federal Government to States and local governments in carrying out their responsibilities to alleviate suffering and damage resulting from major disasters, to repair essential public facilities in major disasters, and to foster the development of such State and local organizations and plans to cope with major disasters as may be necessary.29

Section 8 of the act limited the authorized disaster relief funding to $5 million in total.30 This restriction did not effectively constrain funding, however. The first supplemental appropriation for general disaster relief authorized under the Disaster Relief Act for 1950 provided $25 million, and a waiver of the Section 8 limitation.31 The first authorized annual appropriation for general disaster relief was for $800,000, enacted August 31, 1951, less than two months later.32 Annual appropriations were "to be available until expended," rather than expiring as previous general disaster relief appropriations had, and their use for administrative expenses was statutorily capped at 2% per year.33

Under the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations, the federal government's role in disaster relief expanded further.34 Federal general disaster relief programs broadened in 1962, with the inclusion of several American territories, and grants for repair of state facilities.35

However, Congress still passed specific legislation authorizing relief programs pursuant to other major disasters. In 1964 and 1965, post-disaster legislation provided specific relief for victims of an earthquake in Alaska,36 flooding in western states,37 and victims of Hurricane Betsy in Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi.38 In a history of disaster relief legislation, one observer described the situation thus:

In 1962, 1964, and 1965, Congress had sought to preserve P.L. 81-875 [the Disaster Relief Act of 1950] and yet provide disaster assistance in the case of the very big disasters by special legislation only for the states named. Although no one at the time appeared aware that the new types of assistance would become precedents for general legislation, it was in the nature of the system that ultimately they would be reenacted for general use.39

1966-1974: The Disaster Relief Act of 1966—General Relief Broadens

The Disaster Relief Act of 196640 revised the general disaster assistance program by providing more assistance to public colleges and universities, as well as authorizing assistance to repair local public facilities.41 The Disaster Relief Act of 196942 was enacted in response to Hurricane Camille, although the expansion of the federal role in disaster assistance it represented had been included in legislation since 1965. It included broader public and individual assistance, including temporary housing, food assistance, unemployment assistance, and the federal government funding up to half the cost of repair and restoration of public facilities, and providing matching funds to help states develop preparedness plans.43 Not all of these costs would be borne by the funding provided to the President, and the programs were only authorized through calendar 1970, but they represented a significant broadening of federal government involvement.

The Disaster Relief Act of 197044 consolidated the previous disaster relief legislation into a single act, and made many of the Camille-driven programs permanent, including a permanent program to provide temporary housing assistance, and programs for debris removal and permanent repair and replacement of state and local public facilities.

1974-Present: The Era of Federally Coordinated Emergency Management

The Disaster Relief Act of 197445 provided for a more robust preparedness program, and introduced the concept of "emergency" declarations to accommodate assistance in cases where an incident did not rise to the "major disaster" threshold.46

The Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Amendments of 1988 (P.L. 100-707, hereinafter DREAA) renamed the Disaster Relief Act of 1974 as the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (the aforementioned Stafford Act).47 It made the following programmatic changes:

- Authorized the President to declare an emergency under the Stafford Act in "any occasion or instance" in which federal aid is needed—allowing for assistance without a major disaster declaration;48

- Defined a "major disaster" as "any natural catastrophe ... or, regardless of cause, any fire, flood, or explosion, in any part of the United States, which in the determination of the President causes damage of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant major disaster assistance.... "49

- Established a 75% minimum level of assistance for the immediate response, debris removal, and repair of public facilities; and

- Provided for a 50/50 cost share for hazard mitigation grants.50

The Stafford Act and the DREAA are the pieces of legislation that structure the current relationship between the federal and state government in emergency management and disaster relief. These laws, which appear at 42 U.S.C. 5121 et seq., continue to be amended, with reform legislation frequently following on the heels of exceptionally large disasters, or complexes of disasters. This has happened three times since FEMA was incorporated into DHS in 2003:

- 1. The Post Katrina Emergency Reform Act of 2006 (PKEMRA)51—Enacted as a sixth title to the FY2007 DHS Appropriations Act, PKREMRA reauthorized and restructured FEMA, and made amendments to the Stafford Act, including allowing federal assistance to be provided in the absence of a specific request, improved assistance for individuals with disabilities, and expanded availability of public assistance to non-governmental organizations.

- 2. The Sandy Recovery Improvement Act (SRIA)52—Enacted as a part of the FY2013 supplemental appropriations act, SRIA included alternative procedures for the Stafford Act Public Assistance program to allow disaster impacted area to get assistance on the basis of cost estimates rather than reimbursement of costs, among other reforms.

- 3. The Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018 (DRRA)53—Enacted through language that was attached to an FAA reauthorization measure in the wake of wildfires in California as well as Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria, DRRA has provisions to broaden federal investments from the DRF into mitigation efforts to protect public infrastructure, as well as making improvements to the Public Assistance and Individual Assistance programs. For additional information on these reforms, see CRS Report R45819, The Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018 (DRRA): A Summary of Selected Statutory Provisions.

Appropriations for General Disaster Relief

Types of Appropriations for Disaster Relief

General disaster relief activities by the federal government under the Stafford Act are funded through the appropriations process. Three types of appropriations support these activities:

Supplemental Appropriations are requested by the Administration on an ad hoc basis, generally to address a need not sufficiently covered in the annual appropriations process. These move on a short timetable and generally do not go through the complete committee process. More than 82% of net appropriations for the DRF have been provided through supplemental appropriations.

Annual Appropriations: Requested by the Administration in February as a part of the annual budget process, these are expected to be passed by Congress and enacted into law prior to the start of the fiscal year in October. Annual appropriations measures fund the core activities of the government and are developed through the committee process.

Continuing Appropriations: Provided when annual appropriations work remains unresolved at the beginning of the new fiscal year, these appropriations are temporary budget authority provided at a rate for operations based on the prior fiscal year to allow the government to continue functioning. The measure that provides them is termed a "continuing resolution," or "CR." These continuing appropriations may expire (in the case of an interim CR), or extend to the end of the fiscal year (in the case of a "long-term" CR).

Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief

The current Disaster Relief Fund concept can trace its birth back to an appropriations bill in the 1940s—the Second Deficiency Appropriations Act, 1948.54 Deficiency appropriations bills, which provided funding to meet unanticipated needs during the fiscal year, were a forerunner of modern supplemental appropriations bills. The severity, frequency, and resultant costs to the federal government of the array of disasters that will strike the United States have always been unpredictable in an annual budgetary context. To respond to this uncertainty, disaster relief funding frequently has been provided through deficiency, and later supplemental, appropriations.

When Congress and the Administration began to express concerns about the budget deficit in the 1980s, efforts were made to restrain supplemental spending by limiting it to cases of "dire emergency." With the implementation of budget control in the 1990s, a special designation for emergency spending was created. If both Congress and the Administration agreed that certain spending was an emergency requirement, budget limits would be adjusted to accommodate that spending. Congress used the emergency designation on a disaster relief appropriation for the first time in an FY1992 supplemental appropriations act.55 Congress continues to use emergency designations in supplemental appropriations legislation to provide budgetary flexibility.

At one point, Congress was statutorily required to use the designation for disaster relief appropriations. Under the terms of the aforementioned FY1992 supplemental appropriations act, beginning in FY1993, Congress required "all amounts appropriated for disaster assistance payments [under the Stafford Act] that are in excess of either the historical annual average obligation of $320,000,000, or the amount submitted in the President's initial budget request, whichever is lower" to be designated as emergency requirements under a specific provision of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985.56 This practice of emergency designation above a particular threshold was followed until FY2000, when a clause appeared in the appropriation noting that discretionary appropriations were being provided notwithstanding the restrictions of this section of the U.S. Code.57

With the passage of the Budget Control Act in 2011, which provided additional budgetary flexibility for the costs for major disasters, supplemental disaster relief appropriations declined in frequency, but remained a primary contributor to balances in the DRF. See the "DRF Funding History: FY1964-FY2019" section below for details.

Annual Appropriations

As was noted above, the first general disaster relief funding was provided in an annual appropriations act in 1948, and carried its own authorizing provisions. Stand-alone authorization for general disaster relief first came in 1950.

Once the initial separate authorization was put in place for general disaster relief, appropriations were provided for FY1952, FY1956-FY1958, and FY1962. With the broadening of the relief program to cover more types of damages and the authorization of aid on general terms that had only been made on a case-by-case basis before the mid-1960s, appropriations for general disaster relief became more common—and larger. Annual appropriations for general disaster relief have been provided each year since FY1964, with only two exceptions.58

Disaster Relief Designation

The adoption of a special designation for the costs of major disasters under the Stafford Act as a part of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) made it easier to provide budget authority to the DRF in the annual appropriations process.59 In the first seven appropriations cycles since the implementation of this designation in FY2012, more budget authority was provided for the DRF in annual appropriations measures than in the 63 prior cycles combined, accounting for inflation. The gross appropriation for the DRF of $12.558 billion in FY2019 was the largest annual appropriation ever for the DRF, breaking the record set by the FY2018 annual appropriation. That record appears likely to be broken again, as the Trump Administration requested $14.550 billion for the DRF in FY2020, and both House and Senate committee-reported annual DHS appropriations bills meet or exceed that funding level.

Since the FY2013 budget request, FEMA has bifurcated its annual appropriations request between the costs of major disasters—the "Disaster Relief Category"—and everything else funded by the DRF—"Base Disaster Relief," which includes funding for emergency designations, fire management assistance, pre-disaster declaration surge activities, and Disaster Readiness and Support Programs. The former category is eligible for the designation as "disaster relief," a designation that triggers an upward adjustment of statutory discretionary spending limits to accommodate it without triggering sequestration. The latter category is not, and scores as discretionary spending.

Continuing Appropriations

Even though the DRF is a "no-year" fund, and its appropriations are available until expended, it does get temporary replenishment from continuing resolutions (CRs) at times, until its annual appropriations are finalized.

In FY1982, for the first time, interim general disaster relief funding was provided in a CR through an "anomaly," a provision providing funds at an operating rate different from that base rate of operations provided in the resolution.60

These "anomaly" provisions may also provide flexibility that can help avoid some of the complications that can arise under the constraints of operating under continuing appropriations. For example, CRs generally provide funding at a constant rate of operations, with certain restrictions. This can complicate disaster response and recovery, when calls for funding vary in scale and timing from year to year. When FEMA responds to major disasters of significant size while operating under a CR, either FEMA requests special flexibility from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB)—which apportions funding to agencies—or CRs direct flexibility to be provided to ensure adequate resources are available for disaster response and recovery. Such language can be found in the initial CRs for FY2018 through FY2020, which all provide that the funds provided "may be apportioned up to the rate for operations necessary to carry out response and recovery activities" under the Stafford Act.61

|

Lapses in Annual Appropriations and the DRF Most annual appropriations expire at the end of the fiscal year. On several occasions in recent history, neither annual nor continuing appropriations were enacted prior to the beginning of the fiscal year, leading to a "funding gap" or "lapse" in appropriations. When this occurs, partial shutdown of government functions and emergency furlough of employees ensues for functions that are not funded through fee revenues or multiyear appropriations, and do not immediately protect life and property. The Disaster Relief appropriation can fund disaster relief operations, as its appropriations do not expire at the end of the fiscal year, but lapses in annual appropriations have an impact on agency efficiency. Some disaster-related functions have been subject to emergency furlough in the past.62 Such furloughs may indirectly affect the ability of a component to carry out its mission. For example, in the event of a shutdown and furlough, while staff directly engaged in activities to prevent loss of life or property are not subject to furlough, other staff are not available to review grant requests or approve the release of appropriated funds for non-emergency disaster recovery grants from the DRF. |

DRF Funding History: FY1964-FY2019

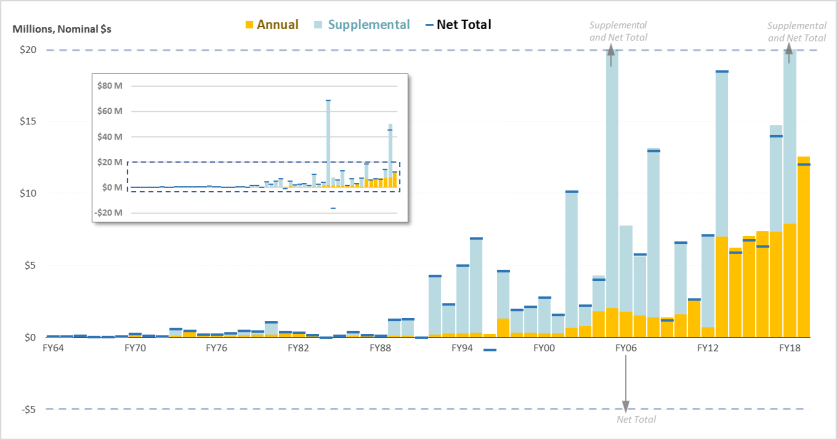

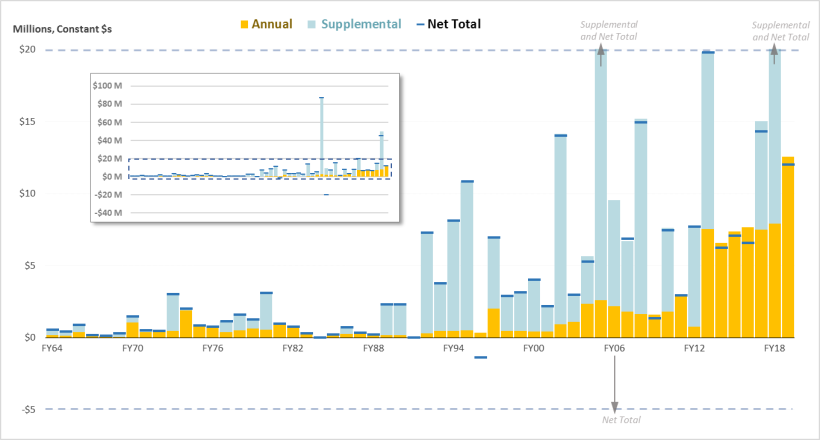

The following figures show appropriations for the DRF from FY1964 through FY2019.

Each fiscal year shows a gross total of annual appropriations and discretionary appropriations (represented by a two-part bar) and a net total (represented by a black mark on each bar), which takes into account rescissions and transfers from the DRF. An inset graphic provides the scale to include funding levels for several outlier years,63 while showing the detail of appropriations for the more typical years. The first figure shows data in nominal dollars, and the second shows constant FY2019 dollars.

The figures show an increase in appropriations for the DRF starting in the 1990s, largely due to increases in supplemental appropriations. Annual appropriations rose significantly in the early 2000s and again starting in FY2013. Even with the surge in appropriations for the 2017 catastrophic series of disasters, which included Hurricane Harvey, Hurricane Maria, and the California wildfires, FY2005 remains the single highest year for appropriations for the DRF, when a series of hurricanes, including Katrina, Rita, and Wilma hit the southeastern United States.64

A table showing the underlying data for each figure appears in the Appendix.

|

Figure 1. Nominal Dollar Disaster Relief Appropriations, FY1964-FY2019 |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of appropriations laws. Notes: Totals for FY2005, FY2006, and FY2017, referenced by the arrows, are beyond the scale of the main graph and are shown on the inset. FY2013 numbers do not reflect the impact of sequestration. Supplemental data include contingent appropriations and all appropriations under the heading of "Disaster Relief" or "Disaster Relief Fund" including the language "for an additional amount." Reductions reflected in the Net Total data include transfers and rescissions specifically enumerated in appropriations acts. For information on trends in the declarations that helped drive the demand for these appropriations, see CRS Report R42702, Stafford Act Declarations 1953-2016: Trends, Analyses, and Implications for Congress. |

|

Figure 2. FY2019 Dollar Disaster Relief Appropriations, FY1964-FY2019 |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of appropriations laws. Notes: Totals for FY2005, FY2006, and FY2017, referenced by the arrows, are beyond the scale of the main graph and are shown on the inset. FY2013 numbers do not reflect the impact of sequestration. Supplemental data include contingent appropriations and all appropriations under the heading of "Disaster Relief" or "Disaster Relief Fund" including the language "for an additional amount." Reductions reflected in the Net Total data include transfers and rescissions specifically enumerated in appropriations acts. For information on trends in the declarations that helped drive the demand for these appropriations, see CRS Report R42702, Stafford Act Declarations 1953-2016: Trends, Analyses, and Implications for Congress. |

Factors in Changing Appropriations Levels

FEMA's budget justifications have noted for years, in one form or another, that "[t]he primary cost driver associated with Major Disasters is disaster activity."65 Although year-to-year disaster relief appropriations are largely driven by disaster activity and ongoing recovery needs, when analyzing historical data over an extended time frame, other factors such as programmatic changes in general disaster relief and certain changes in the budget process may also warrant consideration.

Incident Frequency and Severity

The two largest factors affecting year-to-year disaster relief appropriations are disaster activity, which varies in frequency and severity, and the ongoing recovery costs from previous disasters. Federal involvement in disaster response and recovery occurs when lower levels of government find their capabilities are overwhelmed and turn to the federal government for help. Reduced (or increased) numbers of calls for relief mean reduced (or increased) need for disaster relief appropriations.

The incidents that lead to expenditures from the DRF vary in scale. Equally powerful storms may strike a community a glancing blow or a direct hit. An earthquake may hit a rural area, or a major city with complex infrastructure. Stricken communities, states, territories, and tribes have varying levels of preparedness for particular types of disaster. Spending to help large, complex communities rebuild disaster-damaged facilities and infrastructure and mitigate against future disasters is a significant multiyear cost largely paid for from the Disaster Relief Fund.

Some observers have noted that as the U.S. population grows and develops property in disaster-prone areas, and as patterns of severe weather shift, the costs of disasters are likely to continue to rise.66 According to the National Centers for Environmental Information of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, from 1980 through October 2019, the United States has averaged slightly more than six weather-related disaster events that each cost $1 billion or more each year. From 1980 through 2007, more than seven billion-dollar events occurred in only one year (1998). Since 2007, only one year has seen fewer than seven such events, and ten or more such events have occurred each year from 2015 to 2019.67

Using Figure 2, one can contrast this period of high-frequency, high-impact events of the 2010s to the relatively calm period of the 1980s. Without the driver of large disasters, DRF appropriations remained modest. Over the period from FY1981 to FY1991, abnormally low levels of disaster activity led to no supplemental appropriations for 7 of those 11 fiscal years, and no annual appropriations in either FY1984 or FY1991—the only two fiscal years for which this has occurred since FY1964. By contrast, over the last six years, the DRF has required sustained high levels of appropriations, including three of its six highest total appropriations ever by fiscal year, even adjusting for inflation, and back-to-back largest annual appropriations in FY2018 and FY2019.

Further analysis of recent years shows the association between spending from the DRF and the frequency of high-cost events is closer than the association with the number of major disaster declarations. Table 1 shows data from FEMA regarding the number of major disasters declared from FY2004 through FY2019. It also shows FEMA's accounting for the number of major disasters incurring more than $500 million in projected costs to FEMA in terms of the federal share of Stafford Act programs, and the totals of those costs by fiscal year of the incident. The last column shows the total gross appropriations for the DRF for each fiscal year.

Table 1. Disaster Declaration Activities and Projected Costs of Catastrophic Disaster Declarations, FY2004-FY2019

|

Fiscal Year |

Number of Catastrophic Disaster Declarations |

Total Projected FEMA Costs of Catastrophic Disasters ($millions, nominal) |

Total Gross DRF Appropriation ($millions, nominal) |

||||

|

2004 |

65 |

5 |

|

|

|||

|

2005 |

45 |

5 |

|

|

|||

|

2006 |

53 |

1 |

|

|

|||

|

2007 |

67 |

0 |

|

|

|||

|

2008 |

68 |

3 |

|

|

|||

|

2009 |

63 |

0 |

|

|

|||

|

2010 |

79 |

1 |

|

|

|||

|

2011 |

98 |

2 |

|

|

|||

|

2012 |

46 |

1 |

|

|

|||

|

2013 |

65 |

3 |

|

|

|||

|

2014 |

48 |

0 |

|

|

|||

|

2015 |

44 |

0 |

|

|

|||

|

2016 |

41 |

2 |

|

|

|||

|

2017 |

60 |

8 |

|

|

|||

|

2018 |

54 |

2 |

|

|

|||

|

2019 |

53 |

4 |

|

|

|||

|

Total |

959 |

37 |

|

|

|||

|

Annual Average |

59.3 |

2.3 |

|

|

|||

Source: Email from FEMA Office of Congressional Affairs to CRS, September 24, 2019, and data from FEMA's database of disaster declarations by year, as of November 12, 2019 (https://www.fema.gov/disasters/year).

Notes: DRF appropriations totals reflect the impacts of rescissions and legislatively directed transfers. Due to the nature of the data presented, the information in the figure represents nominal dollars. FY2013 data does not include the impact of sequestration.

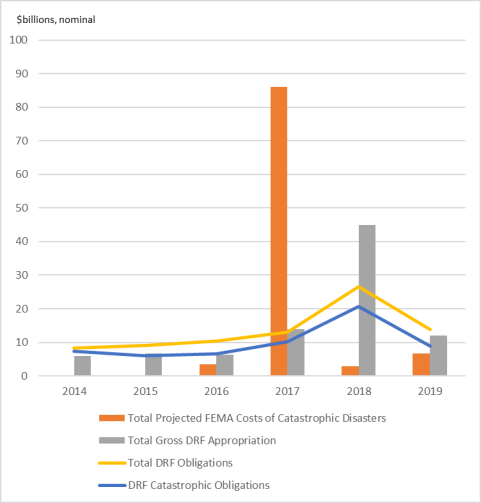

Taking the FEMA catastrophic event cost projections and the net total DRF appropriations from the two right-hand columns in Table 1 and matching them up in Figure 3 illuminates two key points about the DRF. First, catastrophic events are the major driver of DRF funding, rather than the volume of major disaster declarations. Second, while a large amount of appropriations are provided for the DRF in the immediate aftermath of catastrophic incidents, subsequent years' appropriations and obligations are also elevated to address long-term recovery costs.68

Figure 3 focuses on FY2014 through FY2019, supplementing the above data with obligation data, shown as lines that illustrate total annual obligations for the DRF and for catastrophic disasters from the DRF.

A large appropriation for the DRF in FY2013 followed Hurricane Sandy. The obligations in excess of the appropriations in FY2014 and FY2015 show those resources being spent down, as no catastrophic incidents occurred to generate new demand. Harvey, Irma, Maria, and the 2017 California wildfires led to large projected costs of FY2017 catastrophic disasters. The spike in immediate appropriations doesn't match that projection, but instead appears the following year, as the obligations do not occur immediately.

Disaster relief appropriations continue to pay these costs for years after catastrophic incidents: in FY2020, FEMA plans to obligate $12.3 billion in DRF funding for ongoing recovery from past catastrophic disasters, including over $6.2 billion for the four 2017 events mentioned above, $513 million for Hurricane Sandy (2012) and $200 million for costs from hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma (2005).

|

Figure 3. Catastrophic Disasters, DRF Appropriations and Obligations, FY2014-FY2019 |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of FEMA data reflected in Table 1 and monthly DRF reports. Notes: DRF appropriations totals reflect the impacts of rescissions and legislatively directed transfers. Due to the nature of the data presented, the information in the figure represents nominal dollars. Catastrophic obligations are net of deobligations. |

Programmatic Changes in Disaster Relief

Over the long term, alterations to the scope of federal disaster relief programs affect the type and level of federal spending when disasters occur. The Disaster Relief Act of 1950 authorized funding to repair local public facilities at the President's discretion. As the brief history above relates, the federal program for general disaster relief has evolved into a much broader program, of which local public facilities is only one facet.

This evolution has occurred gradually. Some of this evolution was the result of incorporating assistance offered in response to specific disasters in the 1960s and 1970s into the general relief programs under the Stafford Act. Another facet of this evolution was the broadening of the federal role in helping respond to smaller-scale incidents, including proactive declarations prior to potential disasters to reduce their impact. In addition, disaster relief programs funded through the DRF now include disaster mitigation programs that are not limited to mitigating the disaster that triggered them, but are also intended to reduce the impact (and by extension, the cost) of disasters over the long term.

The impacts of programmatic expansions are reflected in Figure 2, with the trend of increased general disaster relief appropriations on a small scale associated with expansions under the Disaster Relief Act of 1969 and the Disaster Relief Act of 1970, and on a larger scale with the expansion of programs under the Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Amendments of 1988. While the decrease in disaster activities in the 1980s reduced the annual demand for disaster relief appropriations, once the number of declared disasters rose again, and emergencies and mitigation also drew on DRF resources, demand for those resources grew rapidly.

Programmatic broadening in general disaster relief has continued in the 21st century. For a more detailed discussion of all these changes to authorized programs, see "1966-1974: The Disaster Relief Act of 1966—General Relief Broadens" and "1974-Present: The Era of Federally Coordinated Emergency Management."

Changes in the Budget Process

Changes in congressional budget processes have at times been discussed as a means of limiting the budgetary impact of disaster relief spending. However, the budget controls that have been approved and implemented have more often been provided with provisions to ensure disaster relief budget authority remains available if needed.

Prior to 1985, Congress provided appropriations to fund the federal government without specific statutory limitations on overall spending. The 1985 Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act put limits on deficit spending in place. The Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 placed express limits on discretionary spending for the first time.

The 1990 act also provided an exception to those limits, allowing Congress, together with the President, to declare certain spending to be an emergency requirement, and therefore not subject to those limits. This was used to provide additional appropriations for disaster relief. Although the original set of discretionary limits expired, the emergency spending designation has continued as part of the appropriations process.

In 2011, the Budget Control Act (P.L. 112-25) not only reestablished statutory spending limits, but also provided a special designation for the costs of major disasters, in addition to the emergency designation. The amount of funding that can be designated as disaster relief—defined as spending pursuant to a major disaster declaration—is limited by a formula based on past spending on disaster relief. It is not a restriction on how much can be spent on disasters, however—funding in excess of the allowable adjustment for disaster relief is still eligible for an emergency designation. This formula was adjusted by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 to account for emergency-designated spending on disasters. The special designation for disaster spending will expire along with the discretionary spending limits in 2021.

The impact of these changes in the budget process on disaster relief appropriations appears to be limited to the structure of the total appropriations, rather than the amount. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) noted that in the 1970s, "about 5%" of supplemental funding was for disasters.69 In a report reviewing supplemental appropriations enacted during the 1980s, CBO indicated that number fell to less than 1%.70 This can be attributed to the drop in disaster activity discussed above. In a similar report on the 1990s, CBO observed an increase in the use of supplemental appropriations to provide disaster relief, noting the following:

[I]n the 1990s, Presidents Bush and Clinton tended to request—and the Congress tended to provide in regular appropriations—less than what would eventually be spent in those disaster-related accounts. (Some observers say the underfunding was an effort to keep total appropriations under the [budget enforcement] caps.) When a disaster or emergency arose, the Congress enacted supplemental appropriations during the fiscal year, usually at the request of the President. That supplemental funding was designated emergency spending and was therefore not counted under the discretionary spending caps.71

Figure 1 and Figure 2 do not show a distinct impact of budget controls on the overall level of disaster spending. However, they do show an increase in the amount of funding provided in annual appropriations versus supplemental appropriations starting in FY2012. The addition of the disaster relief designation under the Budget Control Act enabled higher funding levels for disasters in the annual appropriations bills, as disaster relief-designated appropriations did not compete with other appropriations for limited discretionary resources, either within the allocations provided to the subcommittee funding FEMA, or within the overall discretionary spending limit. In the early years of the disaster relief designation, this increased annual funding also reduced the frequency and urgency of supplemental appropriations for the DRF.

However, Congress has provided emergency-designated relief for catastrophic disasters in supplemental appropriations, whether statutory budget controls were in place or not.

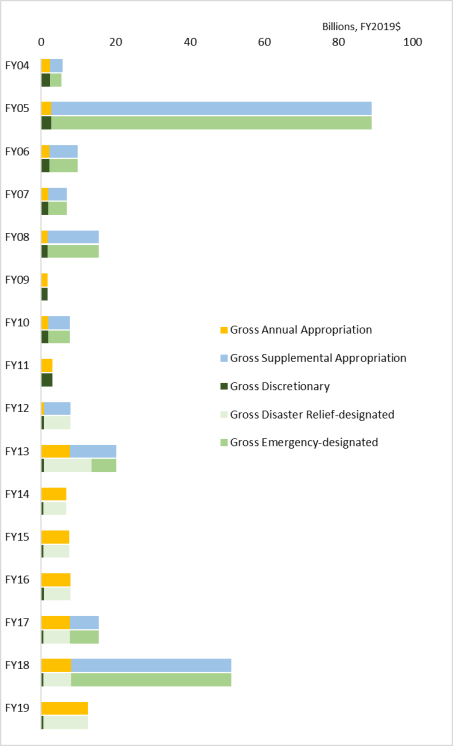

Figure 4 shows funding for the DRF from FY2004 through FY2019, showing, for each fiscal year, the breakdown between annual and supplemental appropriations, then the breakdown of funding provided within budget limitations (discretionary spending) and beyond budget limitations (disaster relief and emergency designated spending). It shows the pre-BCA usage of the emergency designation to cover supplemental appropriations for the DRF, and the usage of the disaster relief designation to cover increased DRF annual appropriations, beginning in FY2013.

Budgeting Practices for Disaster Relief

Management of Disaster Relief Funds

The responsibility for managing DRF appropriations has shifted among agencies as the general disaster relief function grew. In March 1951, President Truman initially delegated the authority for directing federal agencies in a disaster to the Housing and Home Finance Administrator at the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD);72 then in January 1953 the responsibility was shifted to the Federal Civil Defense Administration in the Department of Defense (DOD).73 In 1961, the authority was moved within the department to the Office of Civil Defense Mobilization, which had its name changed in 1961 to the Office of Emergency Planning, and changed again in 1968 to the Office of Emergency Preparedness.74 It remained with that office until its abolishment in 1973, when disaster relief powers were transferred from DOD back to HUD, where those powers were exercised by the Federal Disaster Assistance Administration (FDAA).75

Although management responsibilities were vested in various parts of the federal bureaucracy, appropriations for general disaster relief were provided directly to the Executive Office of the President from FY1948 through FY1973. For FY1974, funds were still described as "Funds Appropriated to the President," but they were provided within HUD's appropriations.76

1978: The Creation of the Federal Emergency Management Agency

In 1978, responding to support for a more cohesive emergency management structure at the federal level, President Jimmy Carter issued Reorganization Plan #3, which created the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). At the time, disaster relief functions were vested in three agencies: the FDAA (at HUD, managing general federal disaster relief), the Federal Preparedness Agency (FPA—part of the General Services Administration); and the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency (DCPA—part of the Department of Defense). This was the first time that emergency management functions at the national level were expressly centralized into a single federal agency. FEMA had a three-part role:

- Mobilizing federal resources,

- Coordinating federal efforts with state and local governments, and

- Managing the efforts of the public and private sectors in disaster responses.

FY1980 was the first year appropriations for "Disaster Relief" were provided to FEMA.

Calculation of the Annual Appropriations Request

A review of selected FEMA budget justifications shows how the executive branch has discussed its decision concerning how much to request for disaster relief.

"Past Experience" and Various Averages

In the early 1980s (1983-1985), FEMA provided justifications for the Disaster Relief appropriation that included management and coordination, individual assistance, and public assistance activities. These activities were also supported under the Emergency Management Planning and Assistance appropriation and the Salaries and Expenses appropriation for FEMA. These justifications noted that actual disaster relief requirements were based on unpredictable external factors. The FY1984 justification noted, "The budget requests mentioned are based on average projection of disaster occurrence. Any significant change from the projected totals, through either more or larger size incidents, could generate an increased request."77

However, despite that uncertainty, a request for a specific budget number leads to questions about the basis for that particular number. In the FY1986 process, FEMA explicitly noted it was projecting its anticipated need "on the basis of past experience with disasters."78 Between September 1984, when FEMA submitted its budget request to the Office of Management and Budget for review, and February 1985, when the budget justification was provided to Congress, additional "experience" was apparently accumulated that reduced the projected demand for disaster relief from $350 million to $275 million.79

By the FY1989 appropriations cycle, the language justifying the request had evolved into "an assessment of historical averages," and included specific data on the average annual disaster relief obligations for a seven-year period,80 as well as the disaster relief obligations for the most recently concluded fiscal year. The budget justification then included a request, noting the request and the projected obligation data that justified it included $30 million in savings through unspecified "legislative and administrative reforms."81

As has been noted before, by the late 1980s and into the 1990s, concerns about deficit spending led to the discussion of budget controls, and ultimately their implementation.

The FY1992 request highlighted the difficulty in simply using averages of past obligations. According to the justification, the average annual obligation from 1981 to 1989 of $270 million was exceeded by the FY1990 obligation of over $2 billion for costs related to Hurricane Hugo82 and the Lomo Prieta earthquake.83

The FY1994 request included a great deal of information on prior-year activities, discussing these elements in the context of average levels of obligations, and noting the impact of larger disasters in prior years, but did little to specifically justify the request level of $292 million.84

Five-Year Averages (With Exceptions)

For FY1995, the budget discussion evolved, as FEMA justified the request on the basis of the first five years of activities under the Stafford Act, and the series of major disasters that had struck.85 The use of the five-year average continued through the 1990s and early 2000s, with disaster support costs—the costs of maintaining disaster response capabilities that are not attributable to a specific disaster—included as well. Certain very large disasters were not included in the average. For example, for FY1999, FEMA explicitly excluded the costs of the Northridge earthquake, plus disaster support costs.86 For FY2003, not only was Northridge excluded from the average, but so were the impacts of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

By FY2009, the justification had again evolved: "Coupled with funding from recoveries of prior year obligations and unobligated funds carried forward, the appropriation request will fund the five-year average obligation level for direct disaster activity (excluding extraordinary events, such as the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001, the 2004 hurricanes in Florida and other states, and Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma in 2005 and 2006 and excluding disaster readiness and support functions)."87 In FY2011, the Administration simplified the request language by referring to disasters that cost less than $500 million as "non-catastrophic disaster activity." That year, in addition to the request for the DRF based on the five-year average of "non-catastrophic" disaster relief obligations, the Administration made a concurrent request for $3.6 billion for the costs of prior catastrophic storms and wildfires.

The Budget Control Act Era: Ten-Year Averages, Reserves, and Flexibility

The 2010s saw continued debate on deficit spending, coupled with a continuing desire to fund disaster relief programs. When Congress passed the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), it created statutory caps on spending as well as a special mechanism to exempt some of the costs of major disasters from those caps. (See "Changes in the Budget Process" for details.)

A $500 million reserve fund was included in the Administration's budget request for FY2012. This was intended to help ensure resources were available on short notice in hurricane season.88 This rose to $1 billion in FY2015. For FY2019, the reserve request increased to $2 billion "due to the uncertainty around the availability of additional supplemental funding to continue addressing the 2017 hurricanes."89

In FY2013, FEMA shifted from using a 5-year average to using a 10-year average of non-catastrophic obligations, plus the estimated requirements for past catastrophic disasters, plus the reserve, as the basis for their overall DRF request.90

|

When the DRF Runs Low At times, the balance in the DRF has dropped to a point that raised concerns about the availability of adequate resources in the DRF to fund Stafford Act programs in the face of disasters. When this occurs, FEMA implements "Immediate Needs Funding" (INF) restrictions, which allow FEMA to prioritize, to an extent, obligation of funds for short-term requirements from the DRF. These INF restrictions do not affect individual assistance, or public assistance programs that reimburse emergency response work and protective measures carried out by state and local authorities—it temporarily puts on hold funding for long-term recovery projects and hazard mitigation projects that FEMA does not have in its system.91 The most recent example of INF restrictions as of this report was in August 2017, when Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, and Hurricane Irma was anticipated to strike U.S. interests. FEMA initiated immediate needs funding on August 28, 2017, as the unobligated balance in the DRF fell below $2.8 billion in the middle of responses to multiple major disasters.92 FEMA lifted the restriction on October 2, 2017, when the DRF was replenished by a $7.4 billion supplemental enacted on September 8, 2017 (P.L. 115-56, Division B), and by the release of additional budget authority pursuant to a continuing resolution (P.L. 115-56, Division D, §129).93 Prior to that implementation, INF restrictions were put into place in each year from FY2003 through FY2006, as well as FY2010. |

Emergency Contingency Funding and Reserve Funds

At times, the Administration and Congress have examined methods of speeding up or broadening the availability of funds to address emergencies and disasters by changing how they were appropriated. Examples of this include the use of contingent appropriations and the proposal to establish a reserve fund for disaster relief.

Contingent Appropriations

In some of its first exercises of the emergency designation, Congress chose to provide a portion of the appropriation for the DRF as emergency-designated budget authority contingent on the Administration specifically requesting the additional funds and designating them as an emergency requirement. An example of this structure can be found in P.L. 103-75, a supplemental appropriations bill for FY1993:

For an additional amount for ''Disaster relief", $1,735,000,000, and in addition, $265,000,000, which shall be available only to the extent an official budget request for a specific dollar amount, that includes designation of the entire amount of the request as an emergency requirement as defined in the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as amended, is transmitted by the President to Congress, to remain available until September 30, 1997, for the Midwest floods and other disasters: Provided, That the entire amount is designated by Congress as an emergency requirement pursuant to section 251(b)(2)(D)(i) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as amended, and title I, chapter II, of Public Law 102-229.94

The FY2002 annual disaster relief appropriation was the last annual appropriation that included this type of contingent appropriation.

Reserve Funds

While appropriations requests for the DRF for many years included a special appropriated reserve within the DRF for unanticipated catastrophic disasters, the concept of a budgetary reserve fund outside the DRF has also been proposed in the past, which would enable appropriations for broader non-Stafford disaster relief initiatives.

In FY2002, alongside a request for the DRF that included disaster support costs and funding for prior-year disasters, the Administration proposed the creation a of $5.6 billion National Emergency Reserve allowance to support the costs of "significant new disasters." The DRF, the Small Business Administration (SBA) Disaster Loan Program, and wildfire programs at the Department of Agriculture and Department of the Interior would have been the primary recipients of this funding.95 The annual reserve would have been established in the budget resolution, and based on the average annual spending on "extraordinarily large events." It would have been allocated to the appropriations subcommittees to fund presidential requests for emergency requirements if two criteria were met: "the events were sudden, urgent, unforeseen, and not permanent; and adequate funding for a normal year has been provided for the applicable program by the Appropriations Committees." Unused reserve amounts could be rolled over into the next year.96 The proposal was not adopted.

Rescissions and the DRF

Rescissions are cancellations of previously appropriated budget authority. They are made at times to redirect unobligated balances to other purposes through further appropriation, or to offset a portion of the cost of the legislation that carried them. From the establishment of the DRF in FY1948 through FY2003, rescissions were made three times from the DRF.97 From FY2004 through the present day, rescissions have been made nine times.

Five of the nine occurred before the enactment of the BCA:

- In FY2004, $225 million of an earlier $500 million supplemental appropriation to the DRF was rescinded as an offset for federal funding for certain wildfire costs in California.98

- In FY2006, over $23.4 billion of $60 billion in gross appropriations for the DRF was rescinded and reappropriated to other disaster recovery programs across the government.99

- In FY2008 and FY2009, three rescissions of DRF funding for the Hazard Mitigation Program for the state of Mississippi were made to pay for a grant for the state to purchase and deploy an interoperable communications system.100

With the restructuring of the DRF appropriation under the BCA, FEMA faced a new challenge. Periodically, obligated funds that were no longer needed or eligible to be used for their original purpose would be "deobligated" and returned to the DRF for use. With the division of the DRF into the base and the costs of major disaster, deobligated funds that had been appropriated without a designation were ultimately considered to be a part of the base. Base funds have the same flexibility as the original undesignated appropriation in terms of use. They can be used for a major disaster or any other Stafford Act activity, while the disaster relief-designated portion can only be used for costs pursuant to a declaration of a major disaster.

These were not insignificant amounts—in FY2013, FEMA recovered $910 million.101 Because the base spends out at a much slower rate than the disaster relief-designated portion of the DRF, a sizeable unobligated balance accrued. Both the Obama Administration and Trump Administration proposed rescinding portions of the unobligated recovered funds, including a request from the Trump Administration to rescind $250 million in FY2020. From FY2014 through FY2017, almost $2.5 billion was rescinded from the DRF, which offset a portion of the cost of the annual DHS appropriations bills.102

The appropriations committees took a different approach in FY2019, specifically including language in the DHS appropriations act to use unobligated balances to fund part of the existing DRF appropriation.103 This has the same net effect as rescinding the funds, but also makes a statement that the DRF balances are being used for Stafford Act purposes. Similar provisions are under consideration for FY2020 as of this writing.

Issues for Congress

The federal government has defined a role for itself in emergency management and disaster recovery, as a backstop for state, local, territorial, and tribal governments, with roles in providing limited relief for individuals and support for mitigation efforts. FEMA's DRF appropriation funds a great deal of the federal effort. As the DRF appropriation is simply an amount of budget authority provided to support a role in disasters that is defined through separately crafted laws and policies, many of the issues related to the DRF are less about the appropriation than they are about that separately defined federal role.

Should the purpose of the DRF be rescoped?

Despite the magnitude of funding provided through the DRF for a range of activities and programs, other appropriations support disaster-related activities in other departments and agencies. As noted earlier, HUD, USDA, DOT, DOD, and SBA all fund various disaster relief and recovery programs.

At various times in the past, efforts have been made to fund activities through the DRF that are not part of the current portfolio of Stafford Act programs. The Stafford Act already encompasses a wide range of emergency management, disaster relief, and disaster response activities. Making non-Stafford programs eligible for DRF funding is something Congress could choose to do, but it would not provide any obvious policy or budgetary advantage. Existing non-Stafford programs have their own funding streams, management, and oversight. Providing their resources through a new appropriation could complicate their funding stream and congressional oversight. While making the programs eligible for funding from the DRF could make additional budget authority available, it would be more transparent and direct for Congress to simply fund the program through its existing appropriation.

There is no special budgetary treatment for appropriations for the DRF—only for appropriations which are designated for the costs of major disasters under the BCA. Shifting discretionary spending out of one appropriations subcommittee's jurisdiction into another provides no overall budgetary benefit—the total amount of spending remains the same. Subcommittee allocations are set and reset every year (sometimes multiple times each year) at the discretion of the House and Senate appropriations committees, so such a move could well result in no net impact on available resources.

The concept of a broader funding stream providing discretionary resources for DRF, SBA, and USDA disaster relief programs has also been considered before. Such an idea, floated by a previous Administration but rejected by Congress, might have made more resources available in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, but it is not clear that reorganizing funding would make the programs subject to more thorough oversight or make them more effective. It could limit the ability of Congress to provide specific oversight or direction through appropriations to the separate programs.

Congress could also break up the DRF into appropriations for the individual Stafford Act programs or groups of programs. This might allow for additional specific congressional oversight and direction, but it could reduce the flexibility that exists within the DRF to shift its resources to meet unanticipated disaster needs by segmenting the available resources.

How much is enough to have on hand?

Appropriations are frequently provided on the basis of what can be spent on a project in a given fiscal year. This thinking informs part of the funding request, as it includes a basis of spending on open disasters, where recovery is ongoing. A 10-year average informs the portion of the DRF budget request that pays for response and recovery from disasters that cost less than $500 million. Previous and current Administrations have sought additional reserve funds over and above those projected needs to pay for potential "no notice" events. On the other hand, as was noted above, from FY2014 to FY2017, almost $2.5 billion in funding was rescinded from unobligated balances in the DRF, and in FY2019, unobligated balances were used to offset appropriations for the DRF. In the present constrained budget environment, Congress continues to weigh the proper level of reserves for FEMA to keep on hand in the DRF.

What accommodations should be made in the federal budget for disaster relief?

While disaster relief is a relatively small part of the discretionary budget, and an even smaller part of the overall federal budget, disaster relief spending is anticipated to continue growing in the coming years. In modern history, Congress has been generally willing to provide resources for major disasters on an as-needed basis. However, discussions of deficit and debt continue in Congress, and may increase in frequency and volume as the Budget Control Act nears expiration in FY2021. The central question is this: Does disaster relief represent enough of a priority for the federal government to maintain the status quo notwithstanding potential increasing costs?

When budget controls were put in place in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2010s, exceptions were provided to help ensure relief and recovery efforts would continue to be funded. With the expiration of the Budget Control Act statutory caps on discretionary spending, one limitation on disaster relief spending—albeit one with a limited practical effect, as noted above—will go away. The allowable adjustment for disaster relief will expire as well, which may have more of an impact, as Congress has used it to move disaster relief spending more fully into the annual appropriations process. The adjustment has effectively allowed most of the annual DRF appropriation to be provided without competing against other homeland security priorities for the discretionary funding provided under the Homeland Security appropriations subcommittee's allocation. Congress may consider whether they want that process to continue.

Congress may also debate whether to try to limit disaster relief spending. The most direct means of doing this would not be to change the DRF appropriation, but by changing the underlying laws that authorize the programs it funds. Implementing relief limits or deductibles for states or smaller jurisdictions, larger nonfederal cost shares, or changes in the declaration process may prove unpopular, and having to vote for them once in more durable authorizing legislation may be more practical than doing so annually in appropriations legislation, which expires.

Appendix. General Disaster Relief Appropriations, FY1964-FY2019

Table A-1. Nominal Dollar Disaster Relief Appropriations, FY1964-FY2019

Thousands of dollars of budget authority

|

Fiscal Year |

Annual Appropriations |

Supplemental (includes contingency appropriations) |

Fiscal Year Total |

Net Fiscal Year Total |

|

1964 |

20,000 |

50,000 |

70,000 |

70,000 |

|

1965 |

20,000 |

35,000 |

55,000 |

55,000 |

|

1966 |

55,000 |

65,000 |

120,000 |

120,000 |

|

1967 |

15,000 |

9,550 |

24,550 |

24,550 |

|

1968 |

20,000 |

— |

20,000 |

20,000 |

|

1969 |

10,000 |

35,000 |

45,000 |

45,000 |

|

1970 |

170,000 |

75,000 |

245,000 |

245,000 |

|

1971 |

65,000 |

25,000 |

90,000 |

90,000 |

|

1972 |

85,000 |

— |

85,000 |

85,000 |

|

1973 |

92,500 |

500,000 |

592,500 |

592,500 |

|

1974 |

400,000 |

32,600 |

432,600 |

432,600 |

|

1975 |

200,000 |

— |

200,000 |

200,000 |

|

1976 |

187,500 |

— |

187,500 |

187,500 |

|

1977 |

100,000 |

200,000 |

300,000 |

300,000 |

|

1978 |

150,000 |

300,000 |

450,000 |

450,000 |

|

1979 |

200,000 |

194,000 |

394,000 |

394,000 |

|

1980 |

193,600 |

870,000 |

1,063,600 |

1,063,600 |

|

1981 |

375,570 |

— |

375,570 |