Land management is a principal mission for four federal agencies: the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and the National Park Service (NPS), all in the Department of the Interior (DOI), and the Forest Service (FS) in the Department of Agriculture (USDA). Together, these agencies administer approximately 610 million acres, about 95% of all federal lands.1 In addition, the agencies have various programs that provide financial and technical assistance to state or local governments, other federal agencies, and/or private landowners.

Each year, the four agencies receive billions of dollars in appropriations for managing federal lands and resources and related purposes (e.g., state and local grant programs). Together, the four agencies had total appropriations of $16.36 billion in FY2018.2 Most of the FY2018 funds—$13.19 billion (81%)—came from discretionary appropriations enacted by Congress through appropriations laws. However, each of the agencies also has mandatory appropriations provided under various authorizing statutes enacted by Congress.3 Laws authorizing mandatory appropriations allow the agencies to spend money without further action by Congress. In FY2018, the four agencies together had $3.17 billion in mandatory appropriations, which was 19% of the total appropriations for the year. Each of the four agencies had a dozen or more mandatory accounts in FY2018. Many of them were relatively small, with funding of less than $5.0 million each, for instance. However, several mandatory accounts each exceeded $100.0 million.

This report focuses on the mandatory appropriations for the four major federal land management agencies.4 It first discusses issues for Congress in considering whether to establish mandatory appropriations for programs or activities. Next, it briefly compares the FY2018 mandatory appropriations of the four agencies. The report then provides detail on the FY2018 mandatory accounts of each of the four federal agencies, as well as additional context on these appropriations over a five-year period (FY2014-FY2018).

Issues for Congress

The Constitution (Article I, §9) prohibits withdrawing funds from the Treasury unless the funds are appropriated by law. A number of issues arise for Congress in deciding the type of appropriations to provide and the terms and conditions of appropriations. One consideration is whether mandatory (rather than discretionary) appropriations best suit the purposes of the program or activity and Congress's role in authorizing, appropriating, and conducting oversight. Another question is how to fund any mandatory appropriations—namely, whether through general government collections (in the General Fund of the Treasury) or through a specific collection (e.g., from a particular activity or tax). A third issue is how to use the funds in a mandatory account, such as for agency activities, revenue sharing with state and local governments, or grant programs.

Mandatory vs. Discretionary Appropriations

Congress may consider various factors in deciding whether to provide discretionary or mandatory appropriations for a program or activity. A key consideration is whether authorizing or appropriating laws will control funding.5 Discretionary spending programs generally are established through authorization laws, which might authorize specific levels of funding for one or more fiscal years. However, the annual appropriations process determines the extent to which those programs actually will be funded, if at all. Mandatory spending is controlled by authorization laws. For this type of spending, the program usually is created and funded in the same law, and the law typically includes language specifying that the program's funding shall be made available "without further appropriation." Many of the mandatory appropriations covered in this report are provided under laws within the purview of the House Committee on Natural Resources and the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. In contrast, discretionary appropriations are provided through appropriations laws within the purview of the House and Senate Committees on Appropriations.6

The frequency with which Congress prefers to review program funding can be a factor in deciding whether to establish mandatory or discretionary appropriations. Authorizing laws (providing mandatory appropriations) generally are permanent and are reviewed not on a particular schedule but rather on an as-needed basis, as determined by the authorizing committees. On the one hand, this can foster stability in mandatory funding, in that the funding mechanisms may not be revised frequently. On the other hand, mandatory appropriations may fluctuate if they depend on revenue sources that might vary from year to year, such as on economic conditions.

In contrast, Congress generally provides discretionary appropriations on an annual basis. This allows for program funding to be adjusted from year to year in response to changing conditions and priorities, and it provides Congress with opportunities for regular program oversight. However, this approach may provide less certainty of funding from year to year, as each program essentially competes with other congressional priorities within overall budget constraints.

Congress has chosen to fund some programs or activities with both mandatory and discretionary appropriations.7 In these cases, both the authorizing laws and the appropriations laws govern a portion of program funding. This approach may allow annual review and decisionmaking on discretionary appropriations to supplement mandatory funding; it also may allow flexibility in providing each type of funding for a different purpose. However, this dual approach may be less efficient or reliable than one type of funding.8

Funding Sources

Congress determines the funding source(s) that support mandatory appropriations. Although many factors may influence the selection of a funding source, a primary consideration is whether the monies should come from government collections in the General Fund of the Treasury or a specific collection, which often is deposited in a special account. The General Fund is the default for government collections unless otherwise specified in law, and it contains monies under a variety of authorities. Many if not all Americans might contribute to the General Fund, for example through income or other taxes. This source might be favored for some mandatory appropriations because it allows central funds to support federal lands managed on behalf of the general public.

In practice, few of the FY2018 mandatory accounts for the four land management agencies received funding from the General Fund. One account that received monies from the General Fund is BLM and FS payments under the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000 (SRS).9 SRS authorized an optional, alternative revenue-sharing payment program for FS generally and for BLM for certain counties in Oregon. The payment amount is determined by a formula based in part on historical revenue payments. Funding for the payment derives from agency receipts and transfers from the General Fund of the Treasury.

Alternatively, Congress may choose to fund mandatory accounts for the four land management agencies from specific collections. In FY2018, specific collections derived from agency receipts, taxes, license fees, tariff and import duties, and donations, among other sources. This approach might be preferred because the revenues derive from activities related to land management and use, especially if the collections are used to invest in the lands and communities from which they are derived.

In FY2018, nearly all mandatory appropriations for the four federal land management agencies were funded by specific collections. Many of these appropriations derived from agency receipts under laws that provide for the collection and retention of money from the sale, lease, rental, or other use of the lands and resources under the agencies' jurisdiction. Agency land uses contributing to receipts included timber harvesting, recreation, and livestock grazing.10

Under some laws, agencies retain 100% of their receipts (e.g., each agency's Operation and Maintenance of Quarters account).11 Other laws direct an agency to retain a portion of receipts; for instance, BLM's Southern Nevada Public Land Sales account contains 85% of receipts from certain BLM land sales and exchanges in Nevada. Still other laws allow an agency to decide the amount of receipts to be deposited in a special account. The FS Knutson-Vandenberg Trust Fund, for example, contains revenue generated from timber sales, with the amount of deposits determined by FS on a case-by-case basis.

Federal excise taxes and fuel taxes funded (at least in part) other FY2018 mandatory appropriations. For example, excise taxes, charged on specific items or groups of items, funded two major FWS programs—Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration (sometimes referred to as Pittman-Robertson) and Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration (sometimes referred to as Dingell-Johnson). Under both programs, the taxes are paid primarily by the people who might benefit from the subsequent expenditures. For the Wildlife Restoration program, taxed items include certain guns, ammunition, and bows and arrows, with the funds primarily used for wildlife restoration programs. Under the Sport Fish Restoration program, the taxed items include sport fishing equipment; this program also receives taxes on motor boat and small engine fuels. The appropriations are used for sport fish restoration programs.

Under licensing fee programs, land users might pay for a particular activity, with the receipts intended to benefit these users or support a related agency program. In FY2018, licensing fees were used for a major FWS program—the Migratory Bird Conservation Account. Under this program, hunters purchase "Duck Stamps" in order to hunt waterfowl and collectors purchase the stamps for collection and conservation purposes. FWS primarily uses the funds derived from these purchases to acquire lands and easements and to protect waterfowl habitat, with the lands and easements added to the National Wildlife Refuge System. Licensing fees also were used in FY2018 to support two relatively small FS programs—Smokey Bear and Woodsy Owl—with the proceeds shared between the licensing contractor and FS (for wildfire prevention and environmental conservation initiatives, respectively).

Tariffs and import duties funded some FY2018 mandatory accounts. For instance, FS's Reforestation Trust Fund receives tariffs collected on imported wood products, up to $30.0 million annually. In addition, import duties on fishing boats and tackle support FWS's Sport Fish Restoration account, and import duties on certain arms and ammunition support FWS's Migratory Bird Conservation account.

The federal land management agencies have authority to accept donations from individuals and organizations for agency projects and activities. All but FS have mandatory authority for some or all donations.12 For instance, in FY2018, FWS and NPS each had a primary mandatory account comprised of the donations. BLM had two relatively small mandatory accounts containing donations for particular purposes (i.e., rangeland improvements and cadastral surveys.)

Uses of the Funds

Laws that establish mandatory accounts typically specify how the monies will be used. A general question for Congress is whether the receipts should be retained for use by the collecting agency or shared with state or local governments or other entities or individuals. For accounts retained for agency use, there are additional considerations. These considerations include whether the monies should be available for a broad array of agency activities or restricted to more narrow purposes, such as Administration priorities, purposes related to the activities that generated the receipts, or activities exclusively at the sites that generated the revenues. For shared accounts, additional considerations include how to divide the funds (e.g., among states) and whether and how to provide revenue-sharing payments or establish grant programs.

Agency Activities

Some of the FY2018 mandatory accounts of the four federal land management agencies were authorized to be used by the agencies. Supporters have viewed this approach as fostering reinvestment in lands from which revenues were derived, which can support continued land uses. Critics contend that agency discretion over use of receipts could incentivize revenue-generating uses over other priorities, such as habitat conversation.

Some of the mandatory FY2018 accounts were available to be used for broad purposes. For example, the four agencies' Recreation Fee accounts can be used for maintenance and facility enhancement, visitor services, law enforcement, and habitat restoration, among other purposes. Similarly, the NPS account for Concession Franchise Fees is authorized for visitor services and high-priority resource management programs and operations. Under both of these fee programs, most of the fees are retained at the collecting site.

Other FY2018 mandatory accounts funded specific agency activities related to the derivation of the receipts. For example, receipts of salvage timber sales fund the FS Timber Salvage Sale Fund; the appropriations can be used to prepare, sell, and administer other salvage sales. As another example, the NPS Transportation Systems Fund is derived from fees for public transportation services within the National Park System. It is used for costs of transportation services in the collecting park units.

State and Local Compensation

Some mandatory spending authorities require revenue sharing with state or local governments, essentially as compensation for the tax-exempt status of federal lands. The accounts commonly provide for compensation based on a specified share of agency receipts. Issues of debate have centered on the level of and basis for compensation and the extent to which consistent and comprehensive compensation should be made across federal lands.

In FY2018, some of the compensation programs encompassed a broad land base (e.g., all national forests), whereas others had a much narrower base (e.g., the national forests in three counties in northern Minnesota). In addition, some programs specified the allowed uses of the funds, and others were not restricted. FS payments to states, for example, can be used only on roads and schools, whereas BLM sharing of grazing receipts can be used generally for the benefit of the counties in which the lands are located.

For some lands or resources, there is no compensation. Where there is compensation, the proportion granted to state and local governments has varied widely, even among programs of one agency. For BLM, for instance, the proportion of revenues from land sales that is shared with states is generally 4% (of gross proceeds) but is 15% for Nevada for certain land sales in the state. In addition, the state share of grazing fee receipts is 12.5% within grazing districts but 50% outside of grazing districts. Some (but not all) compensation programs reduce payments under the Payments in Lieu of Taxes Program.13

Grant Programs

Still other mandatory accounts provide funding for states (and other entities) through formula or competitive grants. They typically provide federal money to accomplish some shared goal or purpose. The area of the state and the size of the population are common parameters used in calculating payments for formula grants. Further, payments typically are made for less than 100% of project costs. For instance, in two FWS grant programs with formula allocations (Wildlife Restoration and Sport Fish Restoration), states and territories may receive a maximum of 75% of costs of projects related, respectively, to wildlife restoration and sport fish habitat (among other purposes). Some observers have viewed the combination of a formula fixed in law and mandatory spending as giving states substantial predictability of federal funding.

Other mandatory accounts are allocated for grants through competition among projects. For example, under the Migratory Bird Conservation account, waterfowl habitat acquisitions must be approved by a federally appointed panel based on nominations of the Secretary of the Interior, among other requirements.

Agency Accounts with Mandatory Appropriations

Overview and Comparison

This section provides information on the mandatory appropriations for each of the four federal land management agencies. It first presents a brief comparison of the number and dollar amounts of mandatory accounts for the four agencies collectively. It then provides detail on each agency's FY2018 mandatory appropriations. For each agency, the discussion separately describes each account with at least $5.0 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018, including the enabling legislation and the source and use of the funds. It then collectively summarizes each agency's accounts with less than $5.0 million in FY2018 mandatory appropriations. For each agency, the section provides a table showing the amount of mandatory appropriations for each account and a figure comparing the accounts.

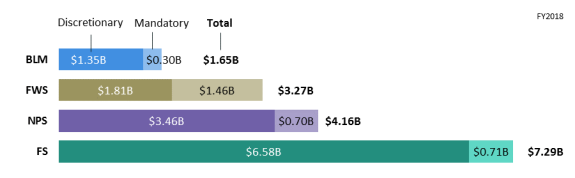

Collectively, in FY2018, the four agencies received $3.17 billion in mandatory appropriations, which was 19% of their total mandatory and discretionary appropriations of $16.36 billion. Discretionary appropriations of $13.19 billion accounted for the remaining 81% of total appropriations for the four agencies.

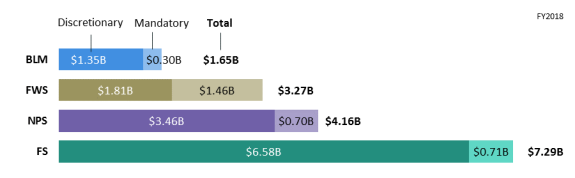

The total dollar amount of mandatory appropriations varied widely among the agencies, from $300.4 million for BLM to $1.46 billion for FWS, as did the percentage of each agency's total appropriation that was mandatory (from 10% for FS to 45% for FWS). Figure 2 shows total appropriations for each agency and the portions that were discretionary and mandatory. Specifically, in FY2018, mandatory appropriations were as follows, in order of increasing amounts:

- $300.4 million for BLM, which was 18% of total agency discretionary and mandatory appropriations ($1.65 billion);

- $704.9 million for NPS, which was 17% of total agency discretionary and mandatory appropriations ($4.16 billion);

- $705.1 million for FS, which was 10% of total agency discretionary and mandatory appropriations ($7.29 billion); and

- $1.46 billion for FWS, which was 45% of total agency discretionary and mandatory appropriations ($3.27 billion).

In FY2018, the four agencies operated with a total of 68 mandatory accounts.14 FWS had the fewest accounts (12), followed by NPS (16), BLM (18), and FS (22). Moreover, the amount of mandatory appropriations ranged widely among accounts, from less than $0.1 million (for several accounts) to $829.1 million (for FWS's Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration). In general, most of the accounts were relatively small. Specifically, of the 68 accounts,

- 33 (49%) each had mandatory appropriations of less than $5.0 million,

- 24 (35%) each had mandatory appropriations of between $5.0 million and $50.0 million,

- 3 (4%) each had mandatory appropriations of between $50.0 million and $100.0 million, and

- 8 (12%) each had mandatory appropriations exceeding $100.0 million.

|

Figure 2. Discretionary, Mandatory, and Total Appropriations for the Four Major Federal Land Management Agencies, FY2018

(in billions of dollars)

|

|

|

Sources: Created by CRS, based on sources including FY2020 agency budget justifications, which contain FY2018 actual funding levels, at http://www.doi.gov/budget for Department of the Interior agencies and https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/media_wysiwyg/usfs-fy-2020-budget-justification.pdf for Forest Service; and FY2018 appropriations laws, including Division G of P.L. 115-141, P.L. 115-72, and P.L. 115-123 and accompanying explanatory statements.

Notes: Figures reflect supplemental appropriations, sequestration reductions, deferrals, and transfers. BLM = Bureau of Land Management; FWS = Fish and Wildlife Service; NPS = National Park Service; FS = Forest Service.

|

Bureau of Land Management

BLM currently administers 246 million acres, heavily concentrated in Alaska and other western states. BLM lands, officially designated as the National System of Public Lands, include grasslands, forests, high mountains, arctic tundra, and deserts.

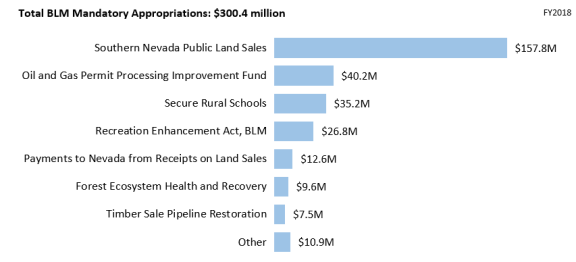

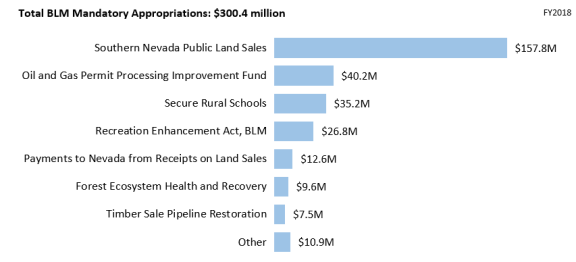

BLM had 18 accounts with mandatory spending authority in FY2018.15 Seven of these accounts had appropriations each exceeding $5.0 million, with the largest account containing $157.8 million. The accounts typically are funded from agency receipts of various sorts. Although several are compensation programs that provide for revenue sharing with state or local governments, most accounts fund BLM activities. Table 1 and Figure 3 show the BLM mandatory appropriations for FY2018.

FY2018 mandatory appropriations for BLM for all 18 accounts were $300.4 million. This amount was 18% of total BLM mandatory and discretionary appropriations of $1.65 billion in FY2018. Discretionary appropriations of $1.35 billion accounted for the remaining 82% of total BLM appropriations.16

Table 1. Mandatory Appropriations for Bureau of Land Management (BLM), by Account, FY2018

(in millions of dollars)

|

BLM Account

|

FY2018

|

|

Accounts with $5.0 Million or More

|

|

|

Southern Nevada Public Land Sales and Earnings on Investments (Federal Funding)

|

$157.8

|

|

Oil and Gas Permit Processing Improvement Fund

|

$40.2

|

|

Secure Rural Schools

|

$35.2

|

|

Recreation Enhancement Act, BLM

|

$26.8

|

|

Payments to Nevada from Receipts on Land Salesa

|

$12.6

|

|

Forest Ecosystem Health and Recovery

|

$9.6

|

|

Timber Sale Pipeline Restoration

|

$7.5

|

|

Accounts with Less Than $5.0 Million

|

|

|

Expenses, Road Maintenance Deposits

|

$3.3

|

|

Payments to States from Grazing Feesb

|

$2.9

|

|

Resource Development, Protection, and Management

(Taylor Grazing Act)

|

$1.1

|

|

Public Survey

|

$1.0

|

|

Operations and Maintenance of Quarters

|

$0.7

|

|

Payments to States from Proceeds of Sales

|

$0.7

|

|

Lincoln County Land Sales

|

$0.6

|

|

Payments to Counties, National Grasslands

|

$0.4

|

|

Washington County, Utah Land Acquisition Account

|

$0.1

|

|

Stewardship Contract Excess Receipts

|

<$0.1

|

|

Naval Petroleum Reserve-2 Lease Revenue Account

|

<$0.1

|

|

Total Mandatory Appropriations

|

$300.4

|

Source: U.S. Department of the Interior, BLM, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2020, at https://www.doi.gov/budget/appropriations/2020.

Notes: Accounts are listed in decreasing order of FY2018 mandatory appropriations. Amounts in column may not sum to total shown due to rounding.

a. This account reflects payments to Nevada under two laws, P.L. 96-586 and P.L. 105-263.

b. This account reflects payments to states under three separate accounts.

|

Figure 3. Comparison of Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Mandatory Appropriations by Account, FY2018

(in millions of dollars)

|

|

|

Source: Created by CRS, based on U.S. Department of the Interior, BLM, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2020, at https://www.doi.gov/budget/appropriations/2020.

Notes: "Other" reflects the total of accounts with less than $5.0 million in mandatory appropriations for FY2018, as shown in Table 1. Amounts for bars may not sum to total shown due to rounding.

|

Southern Nevada Public Land Sales and Earnings on Investments (Federal Funding)

Several laws authorize the sale of some public lands in Nevada. The most extensive authority is the Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act (SNPLMA).17 Under this authority, BLM is authorized to sell or exchange land in Clark County, NV, with a goal of allowing for community expansion and economic development in the Las Vegas area. Of total receipts, 85% are deposited in a special account, which may be used for activities in Nevada, such as federal acquisition of environmentally sensitive lands; capital improvements; and development of parks, trails, and natural areas in Clark County. (The other 15% of receipts are allocated to the state of Nevada, as discussed in "Payments to Nevada from Receipts on Land Sales," below.)

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for this account was $157.8 million. Appropriations vary depending on the amount and value of lands sold. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, the annual mandatory appropriation increased from $51.6 million in FY2014, although FY2018 was the only year in which the appropriation exceeded $100.0 million.18

Oil and Gas Permit Processing Improvement Fund

The Oil and Gas Permit Processing Improvement Fund was established by the Energy Policy Act of 2005.19 The fund supports BLM's oil and gas management program and includes 50% of rents from onshore mineral leases as well as revenue from fees charged by BLM for applications for permits to drill (APDs).20 BLM uses the receipts from both sources for the coordination and processing of oil and gas use authorizations on onshore federal and Indian trust mineral estate land. The receipts generally are targeted for use in particular areas; receipts from onshore mineral leases are used by BLM "project offices,"21 and not less than 75% of the revenue from APD fees is to be used in the state where collected.

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for the Oil and Gas Permit Processing Improvement Fund was $40.2 million. Appropriations have varied based on factors such as the number of active, nonproducing leases (on which rents are paid) each year, the number of APDs issued each year, and the addition of APD fees to the fund beginning in FY2016. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, the annual mandatory appropriation increased overall from $14.1 million in FY2014, with the highest funding level in FY2018 ($40.2 million). The appropriation averaged $24.1 million annually over the five-year period.

Secure Rural Schools

The Oregon and California (O&C) and Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) grant lands are lands that were granted to two private firms, then returned to federal ownership for failure to fulfill the terms of the grants.22 The federal government makes revenue-sharing payments to the western Oregon counties where these lands are located to compensate for the tax-exempt status of federal lands. Under the Act of August 28, 1937, the payments for the O&C lands are 50% of receipts (mostly from timber sales).23 Under the Act of May 24, 1939, CBWR payments are up to 75% of receipts but cannot exceed the taxes that a private landowner would pay.24 The funds may be used for any governmental purpose.

Because of declining receipts, Congress enacted the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000 (SRS) to provide alternative payments—initially through FY2006—based in part on historic rather than current receipts.25 The law has been amended and payments have been reauthorized several times. Most recently, the 115th Congress provided SRS payments for FY2017 and FY2018.26 Under SRS, most of the funds are paid to the O&C and CBWR counties for governmental purposes.27 BLM retains a small portion of the funds for use on the O&C and CBWR lands.

SRS payments are disbursed after the fiscal year ends. The FY2018 mandatory appropriation—to cover the FY2017 SRS payment—was $35.2 million. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, the appropriation fluctuated between $35.2 million in FY2018 and $39.6 million in FY2014, except in FY2017. In FY2017, the appropriation for SRS was $0, due to the (temporary) expiration of the SRS program. Because of the expiration, payments to the O&C counties reverted to the revenue-sharing payments authorized under the aforementioned 1937 and 1939 statutes and were $22.9 million in FY2017.

Recreation Enhancement Act, Bureau of Land Management

The Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act (FLREA) authorizes five agencies, including BLM, to charge and collect fees for recreation.28 The program initially was authorized for 10 years but has been extended, most recently through September 30, 2020.29 FLREA authorizes different kinds of fees, outlines criteria for establishing fees, and prohibits charging fees for certain activities or services. Under the law, BLM charges standard amenity fees in areas or circumstances where a certain level of services or facilities is available and expanded amenity fees for specialized services.

The agency retains the collected fees. In general, at least 80% of the revenue is to be retained and used at the site where it was collected, with the remaining fees used agency-wide. Under law, the Secretary of the Interior can reduce the amount of collections retained at a collecting site to not less than 60% for a fiscal year, if collections are in excess of reasonable needs.30

The law gives BLM (and other agencies in the program) broad discretion in using revenues for specified purposes, which primarily aim to benefit visitors directly. Purposes include facility maintenance, repair, and enhancement; interpretation and visitor services; signs; certain habitat restoration; and law enforcement. The Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture may use a portion of the revenues to administer the recreation fee program.31

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for BLM's Recreation Enhancement Act was $26.8 million.32 Appropriations vary depending on fee rates, the number of locations charging fees, and the number of visitors to BLM lands. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, the annual mandatory appropriation increased overall from $17.7 million in FY2014 to $26.8 million in FY2018, the highest funding level. The appropriation averaged $22.2 million annually over the five-year period.

Payments to Nevada from Receipts on Land Sales

As noted in "Southern Nevada Public Land Sales and Earnings on Investments (Federal Funding)," SNPLMA allocates 15% of receipts from land sales near Las Vegas to the state of Nevada. Specifically, it allocates 5% of receipts to the state's general education program and 10% of receipts to the Southern Nevada Water Authority for water treatment and transmission facilities in Clark County. (The other 85% of receipts under SNPLMA are deposited in a special federal account, as discussed above.)33

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for payments to Nevada from receipts on land sales was $12.6 million. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, the annual mandatory appropriation fluctuated from a low of $5.1 million in FY2014 to a high of $15.8 million in FY2017 and averaged $10.7 million.

Forest Ecosystem Health and Recovery

The Forest Ecosystem Health and Recovery Fund was created by the Department of the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 1993.34 Its purposes and authority have been amended several times. Under current law, funds are derived from the federal share (i.e., the monies not granted to the states or counties) of receipts from the sale of salvage timber from any BLM lands. Salvage sales involve the timely removal of insect-infested, dead, damaged, or down trees that are commercially usable, to capture some of the economic value of the timber resource before it deteriorates or to remove the associated trees for forest health purposes. In general, the fund is used to respond to forest damage and to reduce the risk of catastrophic damage to forests (e.g., through severe wildfire). More specifically, the money can be used to plan, prepare, administer, and monitor salvage timber sales, as well as to reforest salvage timber sites. It also can be used for actions that address forest health problems that could lead to catastrophic damage, such as tree density control and hazardous fuels reduction.35

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for the Forest Ecosystem Health and Recovery Fund was $9.6 million. Appropriations vary from year to year, in part because sales and associated deposits may occur over multiple years. They also vary due to factors that influence tree mortality (e.g., catastrophic wildfires, insect infestations), market fluctuations for the demand and price of the associated harvested wood products, and the expiration or reauthorization of SRS payments.36 Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, the annual mandatory appropriation averaged $7.7 million, ranging from a low of $3.3 million in FY2017 to a high of $12.0 million in FY2015.

Timber Sales Pipeline Restoration

The Timber Sales Pipeline Restoration Fund was authorized by the Omnibus Consolidated Rescissions and Appropriations Act, 1996,37 for BLM (and FS; see "Forest Service" section below). The fund contains the federal share of receipts (i.e., the monies not granted to the states or counties) from certain canceled-but-reinstituted O&C timber sales.38 The account operates as a revolving fund, with 75% of the receipts from timber sales used to prepare additional sales (other than salvage). The other 25% of the receipts is to be used for recreation projects on BLM land. Under law, when the Secretary of the Interior finds that the allowable sales level for the O&C lands has been reached, the Secretary may end payments to this fund and transfer any remaining money to the General Fund of the Treasury as miscellaneous receipts.

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for the Timber Sales Pipeline Restoration Fund was $7.5 million. Appropriations vary from year to year, in part because sales and associated deposits may occur over multiple years. They also vary based on market fluctuations for the demand and price of the associated harvested wood products and the expiration or reauthorization of SRS payments.39 Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, the annual mandatory appropriation fluctuated from a low of $0.4 million in FY2017 to a high of $9.8 million in FY2015 and averaged $5.2 million annually.

Accounts with Less Than $5.0 Million

BLM had 11 additional accounts with mandatory appropriations of less than $5.0 million each in FY2018.40 These accounts collectively received $10.9 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018 and ranged from less than $0.1 million to $3.3 million, as shown in Table 1. Three of the accounts are payment programs under which BLM shares proceeds of land sales or land uses (e.g., livestock grazing) with states and counties. Under some authorities, the states and counties may use the payments for general purposes, such as for the benefit of affected counties; other laws specify particular purposes for which the payments can be used, such as for schools and roads.

Various sources fund the other eight accounts, with BLM retaining the proceeds for particular purposes, as follows:

- Two of the accounts are funded by land sales in particular areas and are used for purposes including land acquisition, resource preservation, and the processing of land use authorizations.

- Two accounts are funded by contributions for cadastral surveys and for administering and improving grazing lands and are used for these purposes.

- One account is funded from rents paid by BLM employees living in government housing and is used to maintain and repair the housing.41

- One account is funded by revenues from mineral lease sales on a particular site and is used to remove environmental contamination.

- One account is funded primarily by fees collected from commercial users of roads under BLM jurisdiction and is used to maintain the areas.

- One account is funded by timber receipts under stewardship contracts and is used for purposes including other stewardship contracts.42

Fish and Wildlife Service

FWS administers the National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS), which consists of land and water designations. The system includes wildlife refuges, waterfowl production areas, and coordination areas, as well as mostly territorial lands and submerged lands and waters within mainly marine wildlife refuges and marine national monuments. FWS also manages other lands within and outside of the NWRS.43

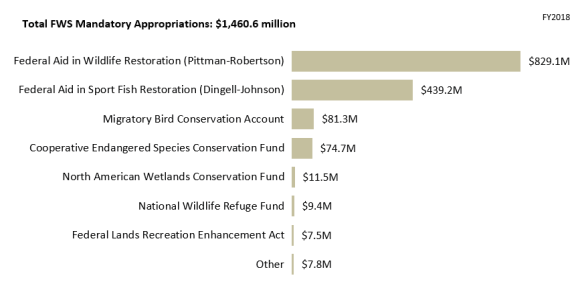

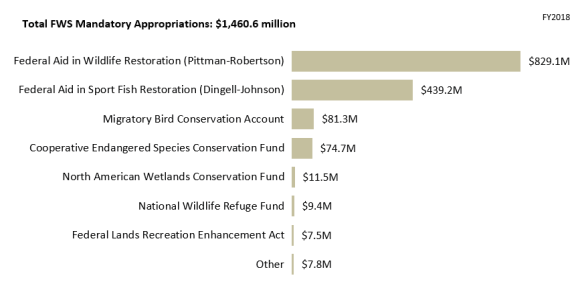

FWS had 12 accounts with mandatory spending authority in FY2018.44 Seven of these accounts had appropriations each exceeding $5.0 million, and the largest had $829.1 million.45 Funding mechanisms for these accounts vary, including receipts; excise and fuel taxes; and fines, penalties, and forfeitures. In addition, three of the accounts receive discretionary appropriations in addition to the mandatory appropriations shown in this report.46 Several accounts, including some of the largest, provide grants to states (and other entities); other accounts fund agency activities or provide compensation to counties. Table 2 and Figure 4 show the FWS mandatory appropriations for FY2018.

FY2018 mandatory appropriations for all 12 FWS accounts were $1.46 billion. This amount was 45% of total FWS mandatory and discretionary appropriations of $3.27 billion in FY2018. Discretionary appropriations of $1.81 billion accounted for the remaining 55% of total FWS appropriations.47

Table 2. Mandatory Appropriations for Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), by Account, FY2018

(in millions of dollars)

|

FWS Account

|

FY2018

|

|

Accounts with $5.0 Million or More

|

|

|

Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration (Pittman-Robertson)

|

|

|

Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration (Dingell-Johnson)

|

|

|

Migratory Bird Conservation Account

|

|

|

Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Funda

|

|

|

North American Wetlands Conservation Fundb

|

|

|

National Wildlife Refuge Fundc

|

|

|

Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act

|

|

|

Accounts with Less Than $5.0 million

|

|

|

Contributed Funds

|

|

|

Operations and Maintenance of Quarters

|

|

|

Lahontan Valley & Pyramid Lake Fish and Wildlife Fund

|

|

|

Proceeds from Sales

|

|

|

Community Partnership Enhancement

|

|

|

Total Mandatory Appropriations

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of the Interior, FWS, Budget Justifications and Performance, Fiscal Year 2020, pp. EX-23 and MP-2, at https://www.fws.gov/budget/2020/FY2020-FWS-Budget-Justification.pdf.

Notes: Accounts are listed in decreasing order of FY2018 mandatory appropriations. Amounts in column may not sum to total shown due to rounding.

a. The amount shown reflects mandatory appropriations. The fund also receives discretionary appropriations, which totaled $53.5 million in FY2018.

b. The amount shown reflects mandatory appropriations. It does not reflect $40.0 million in FY2018 discretionary appropriations or transfers from the Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson restoration programs (of $17.8 and $17.2 million, respectively), which are included in the Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson amounts shown in the table.

c. The amount shown reflects mandatory appropriations. The fund also receives discretionary appropriations, which totaled $13.2 million in FY2018.

|

Figure 4. Comparison of Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) Mandatory Appropriations by Account, FY2018

(in millions of dollars)

|

|

|

Source: Created by CRS, based on U.S. Department of the Interior, FWS, Budget Justifications and Performance, Fiscal Year 2020, pp. EX-23 and MP-2, at https://www.fws.gov/budget/2020/FY2020-FWS-Budget-Justification.pdf.

Notes: "Other" reflects the total of accounts with less than $5.0 million in mandatory appropriations for FY2018, as shown in Table 2. Amounts for bars may not sum to total shown due to rounding.

|

Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration (Pittman-Robertson)

In 1937, the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act created the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Fund, also known as the Pittman-Robertson Fund, in the Treasury.48 As amended, the act directs that excise taxes on certain guns, ammunition, and bows and arrows be deposited into the fund each fiscal year for allocation and dispersal in the year following their collection.49 The Appropriations Act of August 31, 1951, provided for mandatory appropriations for the excise taxes deposited into the Pittman-Robertson Fund in the year after they are collected.50 Many programs are funded from the Pittman-Robertson Fund.51 The majority of the annual funding is allocated to states and territories, which can receive funding to cover up to 75% of the cost of FWS-approved wildlife restoration projects, including acquisition and development of land and water areas. Funding also is provided for hunter education programs and multistate conservation grants. FWS is authorized to use a limited amount of the funds to administer the program. In addition, interest on balances in the account is allocated to the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund.52

Pittman-Robertson received $829.1 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018. This amount included $17.8 million for projects under the North American Wetlands Conservation Act (see "North American Wetlands Conservation Fund"). The mandatory appropriation for Pittman-Robertson varies based on the amount of federal excise taxes collected. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, annual mandatory appropriations varied by more than $100 million, with a low of $725.5 million in FY2016 and a high of $829.1 million in FY2018. The appropriation averaged $790.0 million annually over the five-year period.

Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration (Dingell-Johnson)

In 1950, Congress passed the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act, now known as the Dingell-Johnson Sport Fish Restoration Act.53 The act authorized funding equal to the amount of taxes collected on certain sport fishing equipment to be allocated to the states to be used to carry out sport fish restoration activities.54 The Appropriations Act of August 31, 1951, provided for mandatory appropriations for the amounts used to carry out the act.55 Since its passage, the Dingell-Johnson Act has been amended several times to add additional programs and to modify the source of funding. In 1984, funding for this act became part of a larger Aquatic Resources Trust Fund established in the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984.56 In 2005, the account name was changed to the Sport Fish Restoration and Boating Fund.57 In its current form, the fund receives deposits from five sources: (1) taxes on motorboat fuel (after $1 million is credited to the Land and Water Conservation Fund); (2) taxes on small engine fuel used for outdoor power equipment; (3) excise taxes on sport fishing equipment, such as fishing rods, reels, and lures; (4) import duties on fishing boats and tackle; and (5) interest on unspent funds in the account. Deposits into the fund are available for appropriation in the year after they are collected.

As amended, the Dingell-Johnson Act funds many programs through the Dingell-Johnson Fund. The majority of funds are used for formula grants to states and territories for projects to benefit sport fish habitat, research, inventories, education, stocking of sport fish into suitable habitat, and more.58 The states and territories can receive funding to cover up to 75% of the cost of restoration projects, including acquiring and developing land and water areas. In addition to funds apportioned to states for sport fish restoration projects, funding is allocated to administer various other FWS programs, including Boating Infrastructure Improvement, National Outreach, Multistate Conservation Grants, Coastal Wetlands, Fishery Commissions, and the Sport Fishing and Boating Partnership Council.59 In addition, FWS uses monies from the fund to carry out projects identified through the North American Wetlands Conservation program.60

Dingell-Johnson received $439.2 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018. This amount included $17.2 million for projects under the North American Wetlands Conservation Act (see "North American Wetlands Conservation Fund" for more information). The mandatory appropriation for Dingell-Johnson fluctuates from year to year, because the amount of deposits into the fund varies annually. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, annual mandatory appropriations varied by more than $35 million, with a low of $406.8 million in FY2014 and a high of $442.3 million in FY2016. The appropriation averaged $430.9 million annually over the five-year period.

Migratory Bird Conservation Account61

The Migratory Bird Conservation Account was created in 1934 as the repository for revenues derived from the sale of Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamps, commonly known as Duck Stamps.62 In addition to revenues from Duck Stamps, the fund receives deposits from import duties on certain arms and ammunition, as well as other sources.63 Funding in the Migratory Bird Conservation Account can be used for the printing and sales costs of Duck Stamps and for the Secretary of the Interior to acquire lands and easements and protect waterfowl habitat, with the lands and easements added to the NWRS.64 Prior to acquisition of a property for addition to the NWRS, the Migratory Bird Conservation Commission must approve the property from a list of properties that the Secretary of the Interior nominates for acquisition. Also prior to acquisition, the state in which the acquisition is to occur must enact a law consenting to acquisition by the United States, FWS must consult with the state, and the state's governor must approve the acquisition.65

The Migratory Bird Conservation Account received $81.3 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018. The mandatory appropriation for the Migratory Bird Conservation Account varies from year to year based on fluctuations in deposits from the sale of Duck Stamps and import duties. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, annual mandatory appropriations varied by nearly $20 million, with a low of $62.6 million in FY2015 and a high of $82.3 million in FY2017. The appropriation averaged $72.7 million annually over the five-year period.

Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund

Unlike the other mandatory accounts, the mandatory appropriation for the Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund (CESCF) is not directly available for allocation and disbursal.66 Rather, the mandatory appropriation is paid into a special fund, known as the CESCF, from which funding may be made available in subsequent years through further discretionary action by Congress. As such, the mandatory appropriation for CESCF is different from the mandatory appropriations for other FWS accounts. The mandatory appropriation that is annually deposited into the CESCF consists of an amount equal to 5% of the combined amount covered in the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration and Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration accounts and an amount equal to the excess balance above $500,000 of the sum of penalties, fines, and forfeitures received under the Endangered Species Act and the Lacey Act.67 Funding made available from the CESCF through discretionary appropriations supports grant funding programs that assist states with the conservation of threatened and endangered species and the monitoring of candidate species on nonfederal lands.68

The CESCF received $74.7 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018.69 The mandatory appropriation for the CESCF varies from year to year due to fluctuations in Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson and in the penalties, fines, and forfeitures collected. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2 018, annual mandatory appropriations varied by more than $8 million, between a low of $67.7 million in FY2016 and a high of $75.9 million in FY2017.

North American Wetlands Conservation Fund

The North American Wetlands Conservation Act was enacted in 1989 to provide funding mechanisms to carry out conservation activities in wetlands ecosystems throughout the United States, Canada, and Mexico.70 The funding supports partnerships among interested parties to protect, enhance, restore, and manage wetland ecosystems, and it requires that the partner stakeholders match the federal funding at a minimum rate of one to one.71 Mandatory funding for the program comes from court-imposed fines for violations of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.72 Additional mandatory funding is derived from interest earned on funds from excise taxes on hunting equipment under Pittman-Robertson and transfers from Dingell-Johnson.73 (See "Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration (Pittman-Robertson)" and "Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration (Dingell-Johnson)" for more information.)

The North American Wetlands Conservation Fund received $11.5 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018.74 The mandatory appropriation for the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund varies from year to year due to fluctuations in fines related to violations of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, mandatory appropriations varied by more than $8 million, with a low of $11.4 million in FY2017 and a high of $19.6 million in FY2015. The appropriation averaged $16.2 million annually over the five-year period.

National Wildlife Refuge Fund

The Refuge Revenue Sharing Act was enacted to compensate counties for the loss of revenue due to the tax-exempt status of NWRS lands administered by FWS.75 The National Wildlife Refuge Fund, also called the Refuge Revenue Sharing Fund, accumulates net receipts from the sale of certain products, which are used to pay the counties in the year following their collection pursuant to the act.76 The act also authorizes FWS to deduct funds from the receipts to cover certain costs related to revenue-producing activities. Counties receive payments for FWS-managed lands that were acquired (fee lands) or reserved from the public domain. Counties receive a payment for fee lands based on a formula that pays the greater of (1) $0.75 per acre, (2) three-fourths of 1% of fair market value of the land, or (3) 25% of net receipts.77 Payments for reserved lands are 25% of the net receipts.78 In a given year, if receipts are not sufficient to cover the payments, the act authorizes annual discretionary appropriations to make up some or all of the difference.79 If receipts exceed the amount needed to cover payments, the excess is transferred to the Migratory Bird Conservation Account.80 From FY2014 to FY2017, mandatory and discretionary spending together provided between 20% and 30% of the full, authorized level in the formula, with mandatory appropriations making up between 28% and 41% of the total.81

The National Wildlife Refuge Fund received $9.4 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018.82 The mandatory appropriation for the National Wildlife Refuge Fund fluctuates from year to year due to changes in revenues collected that determine the available funding. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, annual mandatory appropriations varied by more than $4 million, with a low of $7.0 million in FY2014 and a high of $11.4 million in FY2016.

Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act83

In general, FLREA allows national wildlife refuge managers to retain not less than 80% of entrance and user fees collected at the refuge to improve visitor experiences, protect resources, collect fees, and enforce laws relating to public use, among other purposes.84 The remaining amount (up to 20%) is to be made available for agency-wide distribution.85 In practice, some FWS regions have chosen to return 100% of funds to the collecting sites.

The Recreation Fee Program received $7.5 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018. Appropriations vary depending on fee rates, the number of locations charging fees, and the number of visitors to FWS lands. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, the annual mandatory appropriation increased by more than $2 million, with a low of $5.1 million in FY2014 and a high of $7.5 million in FY2018.

Accounts with Less Than $5.0 Million

FWS had five additional accounts with mandatory appropriations of less than $5.0 million each in FY2018. These accounts collectively received $7.8 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018, and they ranged from $0.2 million to $4.0 million, as shown in Table 2. These accounts receive funding from donations and receipts collected for certain activities. For some accounts, the activities are restricted to selected refuges or properties.86 In general, these funds are used for fish and wildlife conservation purposes or for the maintenance or conservation of specific FWS-administered resources. Specific purposes include the following:

- The Contributed Funds account consists of donations, which are used to support various fish and wildlife conservation projects.87

- The Operations and Maintenance of Quarters Fund receives the rents and charges from employees occupying FWS quarters and is used to maintain the structures.88

- The Lahontan Valley and Pyramid Lake Fish and Wildlife Fund uses the receipts associated with a water rights settlement in Nevada to support restoration and enhancement of wetlands and fisheries in the area. Proceeds from the sale of certain lands in the area also are deposited in the fund.

- The Proceeds from Sales Fund uses the receipts from sales of resources on U.S. Army Corps of Engineers land managed by FWS to cover the expenses of managing those sales and carrying out development, conservation, and maintenance of these lands.

- The Community Partnership Enhancement Fund supports collaboration with local groups (e.g., state, local, or academic organizations) whose contributions support local refuges.

Forest Service

FS is charged with conducting forestry research, providing assistance to nonfederal forest owners, and managing the 193-million-acre National Forest System (NFS). The NFS consists of national forests, national grasslands, land utilization projects, and several other land designations.89

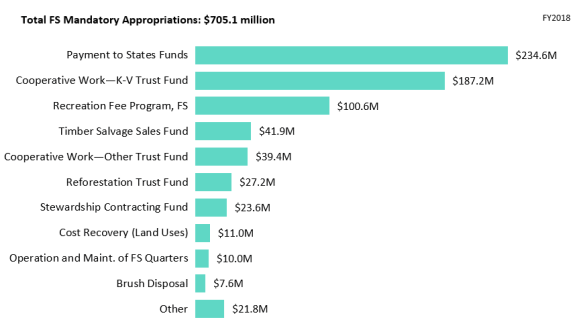

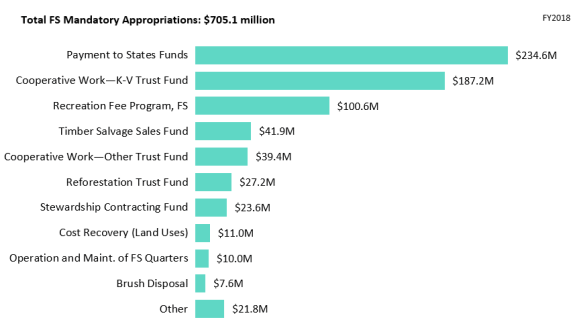

FS had 22 accounts with mandatory spending authority in FY2018.90 Of the 22 accounts, 10 had mandatory appropriations each exceeding $5.0 million in FY2018, with the largest account containing $234.6 million. The remaining 12 accounts had appropriations of less than $5 million each in FY2018 (and half of those had less than $1 million each). Agency receipts fund many of these accounts, although one is supplemented by the General Fund of the Treasury, as needed. Almost all of the accounts support agency activities, but one is for a compensation program. In addition, import tariffs fund one account and license fees fund another. Table 3 and Figure 5 show the FS mandatory appropriations for FY2018.

FY2018 mandatory appropriations for FS for all 22 accounts were $705.1 million. This amount was nearly 10% of total FS mandatory and discretionary appropriations of $7.29 billion in FY2018. Discretionary appropriations of $6.58 billion accounted for the remaining 90% of total FS appropriations.91

Table 3. Mandatory Appropriations for Forest Service (FS), by Account, FY2018

(in millions of dollars)

|

FS Account

|

FY2018

|

|

Accounts with $5.0 Million or More

|

|

|

Payment to States Fundsa

|

|

|

Cooperative Work—Knutson-Vandenberg (K-V) Trust Fund

|

|

|

Recreation Fee Program, FS

|

|

|

Timber Salvage Sale Fund

|

|

|

Cooperative Work—Other Trust Fund

|

|

|

Reforestation Trust Fund

|

|

|

Stewardship Contracting Fund

|

|

|

Cost Recovery (Land Uses)

|

|

|

Operation and Maintenance of FS Quarters

|

|

|

Brush Disposal

|

|

|

Accounts with Less Than $5.0 million

|

|

|

Conveyance of Administrative Sites

|

|

|

Land Between the Lakes Management and Trust Fundb

|

|

|

Timber Sales Pipeline Restoration

|

|

|

Timber Purchaser Election Road Construction

|

|

|

Forest Botanical Products

|

|

|

Restoration of Forest Lands and Improvements

|

|

|

Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie Rental Fees

|

|

|

Commercial Filming and Still Photography Land Use Fees

|

|

|

Organizational Camps Program

|

|

|

Licensee Programs: Smokey Bear and Woodsy Owlc

|

|

|

FS Go Green Program

|

|

|

Site Specific Lands Act

|

|

|

Total Mandatory Appropriations

|

|

Source: FS, FY2020 Budget Justification, March 2019, at https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/media_wysiwyg/usfs-fy-2020-budget-justification.pdf.

Notes: Accounts are listed decreasing order of FY2018 mandatory appropriations. Amounts in column may not sum to total shown due to rounding.

a. The Payment to States account consists of several funds that are used to issue payments to specified state and local governments under several different authorities. FS generally groups the funds together for reporting purposes and at times provides additional details about each fund and associated payment but did not do so for FY2018 in the FY2020 Budget Justification.

b. These are two separate accounts but were combined for this table. The Land Between the Lakes Management permanent appropriation had $4.5 million in mandatory appropriations for FY2018. The Land Between the Lakes Trust Fund had $0.1 million in mandatory appropriations for FY2018.

c. These are two separate accounts but were combined for this table. The Smokey Bear Licensee Program had $0.4 million in mandatory appropriations for FY2018, and the Woodsy Owl Licensee Program had <$0.1 million in mandatory appropriations for FY2018.

|

Figure 5. Comparison of Forest Service (FS) Mandatory Appropriations by Account, FY2018

(in millions of dollars)

|

|

|

Source: Created by CRS, based on FS, FY2020 Budget Justification, March 2019, at https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/media_wysiwyg/usfs-fy-2020-budget-justification.pdf.

Notes: "Other" reflects the total of accounts with less than $5.0 million in mandatory appropriations for FY2018, as shown in Table 3. K-V = Knutson-Vandenberg. Amounts for bars may not sum to total shown due to rounding.

|

Payment to States Funds

Payment to States Funds provide compensation or revenue-sharing payments to specified state and local governments.92 The payments are required based on different laws with varying (but sometimes related) purposes and disbursement formulas, as summarized below. The funds generally consist of receipts from sales, leases, rentals, or other fees for using NFS lands or resources (e.g., timber sales, certain recreation fees, and communication site leases).

- 25% Revenue-Sharing Payments.93 The Act of May 23, 1908, requires states to receive annual payments of 25% of the average gross revenue generated over the previous seven years on the national forests in the state, for use on roads and schools in the counties containing those lands.94 Funded through receipts, the payment is made to the state after the end of the fiscal year. The state cannot retain any of the funds but allocates the payment to the counties based on the area of national forest land in each county.

- SRS Payments. SRS authorized an optional, alternative payment to both the FS 25% revenue-sharing payments and the BLM payments to the counties in Oregon containing the O&C and CBWR lands.95 The payment amount is determined by a formula that is based in part on historical revenue payments and that declines overall by 5% annually. Similar to the 25% revenue-sharing payments, the payment is made after the end of the fiscal year and the bulk of the payment is to be used for roads and schools in the counties containing the national forests. The agency may retain a portion of the payment for use on specified projects. Funding for the payment first comes from receipts and, if necessary, is supplemented through transfers from the General Fund of the Treasury. The original authorization for SRS payments expired at the end of FY2006, but Congress reauthorized the payments several times (through various laws) and payments were made annually from FY2001 through FY2016. The authorization expired for the FY2016 SRS payment, and counties received the 25% revenue-sharing payment for one year, in FY2017. Congress then reauthorized the SRS payments for two years (FY2017 and FY2018).96 SRS payments are disbursed after the fiscal year ends, so the FY2017 payment was made in FY2018 and the FY2018 payment was made in FY2019.

- National Grassland Fund Payments. These payments are authorized by the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act, which requires payments of 25% of net (rather than gross) receipts directly to the counties for roads and schools in the counties where the national grasslands are located.97 These payments are sometimes referred to as Payments to Counties, because the payment is made directly to the counties and the allocation is based on the national grassland acreage in each county.

- Payments to Minnesota Counties. Enacted in 1948, this program pays three northern Minnesota counties 0.75% of the appraised value of the land, without restrictions on using the funds.98

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for the Payment to States Funds was $234.6 million. The funding level in this account varies annually, depending on fluctuations in revenue from the NFS and whether SRS is authorized. For example, over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, annual mandatory appropriations averaged $269.6 million. The FY2018 appropriation was lower than the annual average, and the FY2017 appropriation ($73.1 million) was much lower than the annual average. These low figures occurred primarily because of the expiration of SRS payments in FY2017. SRS payments are generally higher than 25% payments and often require supplemental funding from the General Fund of the Treasury.

Cooperative Work—Knutson-Vandenberg Trust Fund

The Knutson-Vandenberg (K-V) Trust Fund was established by the Act of June 6, 1930, and is funded through revenue generated by timber sales.99 The agency determines the amount collected on each sale, which can be up to 100% of receipts from the sale. The fund is used for two purposes. First, the fund is used on the site of the timber sale to reforest and improve timber stands or to mitigate and enhance non-timber resource values. Second, unobligated balances from the fund may be used for specified land management activities within the same FS region in which the timber sale occurred.100

The K-V Trust Fund received $187.2 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018. Because the deposits are determined on a sale-by-sale basis, the balance in the fund varies from year to year. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, mandatory appropriations ranged from a low of $61.5 million in FY2015 to a high of $250.0 million in FY2014. The average annual mandatory appropriation was $155.7 million.

Recreation Fee Program, Forest Service

FS charges and collects recreational fees under several programs and deposits those funds into the Recreation Fees account to be used for specified purposes. Under FLREA, FS is one of five federal agencies authorized to charge, collect, and retain fees for specified recreational activities on federal lands. 101 FLREA directs that at least 80% of the fees collected from FS are to be available without further appropriation for use at the site where they were collected. FS typically uses the money for visitor services, law enforcement, and other purposes authorized under FLREA. In addition to FLREA, FS is authorized to collect and retain fees at two specific sites: Grey Towers National Historic Site and the Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area (NRA).102 FS is authorized to use the fees collected at the Grey Towers National Historic Site for program support and administration. The agency may use the fees collected at the Shasta-Trinity NRA for the same purposes as FLREA, as well as for direct operating or capital costs associated with the issuance of a marina permit. FS also administers the multiagency National Recreation Reservation Service program, which collects reservation fees for those recreational facilities on federal lands that allow reservations. FS is responsible for collecting the fees and issuing pass-through payments to other agencies.

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for the Recreation Fee Program was $100.6 million. Appropriations vary depending on fee rates, the number of locations charging fees, and the number of visitors to FS lands. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, mandatory appropriations ranged from a low of $70.7 million in FY2014 to a high of $100.6 million in FY2018. The average annual mandatory appropriation during the period was $87.2 million.

Timber Salvage Sale Fund

The Timber Salvage Sale Fund is funded through receipts from timber sales (or portions of sales) designated as salvage by the agency, and its funds may be used to prepare, sell, and administer other salvage sales.103 Salvage sales involve the timely removal of insect-infested, dead, damaged, or down trees that are commercially usable to capture some of the economic value of the timber resource before it deteriorates or to remove the associated trees for stand improvement. The fund may be used for timber sales with any salvage component.104

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for the FS Timber Salvage Sale Fund was $41.9 million. Appropriations vary from year to year, based on factors that influence tree mortality (e.g., catastrophic wildfires, insect infestations) and market fluctuations for the demand and price of the harvested timber. From FY2014 to FY2018, mandatory appropriations ranged from a low of $33.2 million in FY2014 to a high of $41.9 million in FY2018. The mandatory appropriation averaged $37.5 million annually over the five-year period.

Cooperative Work—Other Trust Fund

This trust fund collects deposits from cooperators and partners for use on NFS lands or for funding research programs.105 The deposits may be made under an assortment of instruments, including cooperative agreements, permits, or contracts, and with a variety of partners, for services involving any aspect of forestry ranging from timber measurement to fire protection, among others. These services vary widely in scope and duration, and the associated deposits also vary widely, commensurate with the scale of those services. The deposits may be made pursuant to a specific agreement or project, or they may include funds pooled from multiple cooperators for later spending on related projects. The amount of deposits is specified in each instrument.

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for the trust fund was $39.4 million. Because the fund consists of deposits under many individual cooperative agreements or other instruments, the funding level varies considerably from year to year. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, mandatory appropriations ranged from a low of $34.6 million in FY2014 to a high of $84.1 million in FY2016. The mandatory appropriation averaged $48.2 million annually over the five-year period.

Reforestation Trust Fund

The Reforestation Trust Fund was created in 1980 to eliminate the backlog of reforestation and timber stand improvement work on NFS lands.106 Deposits to this account come from tariffs on specified imported wood products, up to $30.0 million annually.107 Funds may be used for a range of activities related to reforestation (e.g., site preparation for natural regeneration, seeding, or tree planting) and to improve timber stands (e.g., removing vegetation to reduce competition, fertilization).

In FY2018, the Reforestation Trust Fund received $27.2 million in mandatory appropriations. Funding generally has been at or around the maximum of $30.0 million annually. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, the mandatory appropriation averaged $29.4 million annually.

Stewardship Contracting Fund108

Congress authorized FS and BLM to combine timber sale contracts and land restoration services contracts into stewardship contracts.109 This allows the agencies to retain and use the revenue generated from the sale of timber to offset the cost of specified restoration work on their lands. FS and BLM each are authorized to retain any receipts in excess of the cost of the restoration work in their respective Stewardship Contracting Funds and to use those funds on future stewardship contracts.

In FY2018, the mandatory appropriation for the Stewardship Contracting Fund was $23.6 million. Funding varies based on the extent that there are receipts in excess of costs. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, mandatory appropriations ranged from a low of $11.2 million in FY2014 to a high of $23.6 million in FY2018 and averaged $15.8 million annually.

Cost Recovery (Land Uses)

FS is authorized to collect and retain fees to cover the costs of processing and monitoring certain special-use authorizations for the use and occupancy of NFS lands.110 The processing and monitoring fees are based on the estimated number of hours it will take FS to process the application (or renew the authorization) and to monitor the activity to ensure compliance with the authorization. The rates are updated annually to adjust for inflation.

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for Cost Recovery (Land Uses) was $11.0 million. Funding varies based on the number and type of special-use authorizations. From FY2014 to FY2018, mandatory appropriations ranged from a low of $5.4 million in FY2014 to a high of $11.0 million in FY2018 and averaged $7.8 million annually.

Operation and Maintenance of Forest Service Quarters

This account allows the agency to collect rent from employees who use government-owned housing and to use the funds to maintain and repair the structures.111 The FY2018 mandatory appropriation was $10.0 million. Over the five years from FY2014 to FY2018, funding was relatively consistent and mandatory appropriations averaged $9.0 million annually.

Brush Disposal

This account receives money from timber purchasers. The fund is used on timber sale sites to dispose of treetops, limbs, and other debris from timber cutting; reduce fire and insect hazards; assist reforestation; and conduct related activities. FS identifies the amount required to cover the costs of those activities for each timber sale.112

The FY2018 mandatory appropriation for Brush Disposal was $7.6 million. From FY2014 to FY2018, mandatory appropriations ranged from a low of $7.6 million in FY2018 to a high of $9.7 million in FY2015. The appropriation averaged $8.3 million annually.

Accounts with Less Than $5.0 Million

FS had 12 additional accounts with mandatory appropriations of less than $5.0 million each in FY2018, all of which can be used on specified agency activities.113 These accounts collectively received $21.8 million in mandatory appropriations in FY2018, and they ranged from less than $0.1 million to $4.7 million, as shown in Table 3.

Nine of these accounts are funded through receipts or fees for use of NFS lands or resources, with FS retaining the proceeds for particular purposes, as follows. Three accounts are associated with the sale of timber or non-timber wood products and may be used for implementation of additional timber sales, payment for road construction associated with timber sales, or program administration. Four accounts are associated with land use fees. Of these, two accounts are funded through land use fees for specific purposes (e.g., commercial filming or photography, organizational camps) and two accounts are funded through land use fees in specific areas; the funds in those accounts generally may be used for program administration and other specified purposes. Two accounts are funded through land sales and are used for purposes such as land acquisition, building maintenance, rehabilitation, and construction.

Of the remaining three accounts, one is funded through licensee royalty fees and used to support nationwide initiatives related to wildfire prevention and environmental conservation. Another account is funded through recoveries from judgements, settlements, bond forfeitures, and related actions from permittees or timber purchasers who fail to complete the required work, and the funds are used to complete the work or repair any associated damage. The other account is funded through revenue generated from recycling or other waste reduction or prevention programs; its funds are used to implement other recycling, waste reduction, or prevention programs.

National Park Service

NPS administers the National Park System, with 80 million acres of federal land in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The system contains 419 units with diverse titles, including national park, national preserve, national historic site, national recreation area, and national battlefield, among others.114

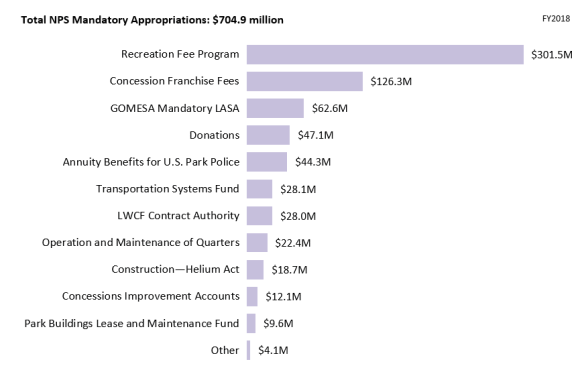

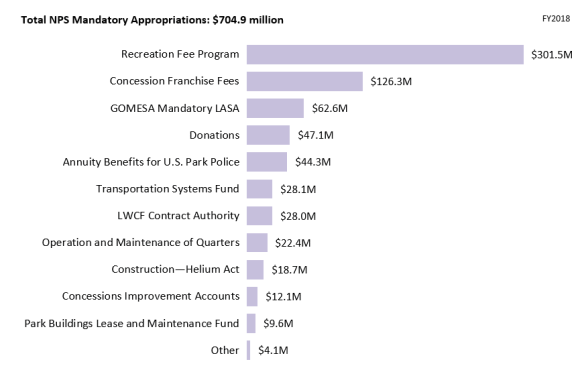

NPS had 16 accounts with mandatory spending authority in FY2018. Of these, 11 accounts had mandatory appropriations each exceeding $5.0 million; the largest had $301.5 million. Funding sources for the accounts vary and include agency receipts, offshore energy development revenues, District of Columbia payments, the General Fund of the Treasury, donations, and an endowment. Almost all of the accounts support agency activities, but one is for recreation assistance grants to states and another is a compensation program.115 Table 4 and Figure 6 show NPS mandatory appropriations for FY2018.

FY2018 mandatory appropriations for all 16 NPS accounts totaled $704.9 million. This amount was 17% of the $4.16 billion total for NPS mandatory and discretionary appropriations combined in FY2018. Discretionary appropriations of $3.46 billion accounted for the remaining 83% of total NPS appropriations.116

Table 4. Mandatory Appropriations for National Park Service (NPS), by Account, FY2018

(in millions of dollars)

|

NPS Account

|

FY2018

|

|

Accounts with $5.0 Million or More

|

|

|

Recreation Fee Program

|

$301.5

|

|

Concession Franchise Fees

|

$126.3

|

|

GOMESA Mandatory Land Acquisition and State Assistance

|

$62.6

|

|

Donations

|

$47.1

|

|

Annuity Benefits for U.S. Park Police

|

$44.3

|

|

Transportation Systems Fund

|

$28.1

|

|

Land and Water Conservation Fund Contract Authority

|

$28.0

|

|

Operation and Maintenance of Quarters

|

$22.4

|

|

Construction—Helium Act

|

$18.7

|

|

Concessions Improvement Accounts

|

$12.1

|

|

Park Buildings Lease and Maintenance Fund

|

$9.6

|

|

Accounts with Less Than $5.0 Million

|

|

|

Deed Restricted Parks Fee Program

|

$2.3

|

|

Filming and Photography Special Use Fee Program

|

$1.8

|

|

Payment for Tax Losses on Land Acquired for Grand Teton Nat. Park

|

<$0.1

|

|

Delaware Water Gap, Route 209 Operations

|

<$0.1

|

|

Preservation, Birthplace of Abraham Lincoln

|

<$0.1

|

|

Total Mandatory Appropriations

|

$704.9

|

Source: NPS, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2020, at https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/fy2020-nps-justification.pdf.

Notes: Accounts are listed in decreasing order of FY2018 mandatory appropriations. Amounts in column may not sum to total shown due to rounding. GOMESA = Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act (43 U.S.C. §1331 note).

|

Figure 6. Comparison of National Park Service (NPS) Mandatory Appropriations by Account, FY2018

(in millions of dollars)

|

|

|

Source: Created by CRS, based on NPS, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2020, at https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/fy2020-nps-justification.pdf.

Notes: "Other" reflects the total of accounts with less than $5.0 million in mandatory appropriations for FY2018, as shown in Table 4. GOMESA = Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act (43 U.S.C. §1331 note). LASA = Land Acquisition and State Assistance. LWCF = Land and Water Conservation Fund. Amounts for bars may not sum to total shown due to rounding.

|

Recreation Fee Program

Like other federal land management agencies, NPS charges, retains, and spends recreation fees under FLREA.117 FLREA authorizes NPS to charge entrance fees at park units and to charge certain recreation and amenity fees for specialized uses of park facilities and services.118 FLREA directs that, in general, at least 80% of the fees collected at a park unit are to be available without further appropriation for use at the site where they were collected.119 In practice, NPS's policy is to allow park units that collect less than $0.5 million annually to retain 100% of collections at the site; park units that collect over $0.5 million annually retain up to 80% of collections. Funds not retained at the collecting site are placed in a centralized account for use agency-wide, including at sites where fee collection is infeasible or relatively low. NPS projects compete for funding from this centralized account, and the NPS director ultimately selects projects for funding. 120