Background

Unaccompanied alien1 children are defined in statute as children who

1) lack lawful immigration status in the United States,2

2) are under the age of 18, and

3) are either without a parent or legal guardian in the United States, or without a parent or legal guardian in the United States who is available to provide care and physical custody.3

Most unaccompanied children are apprehended between U.S. ports of entry along the southwestern border with Mexico. Apprehensions are made by the U.S. Border Patrol (USBP), an agency within the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS's), Customs and Border Protection (CBP). Less frequently, unaccompanied children are deemed inadmissible at U.S. ports of entry along the border by CBP's Office of Field Operations or apprehended in the interior of the country by DHS's Immigration and Customs Enforcement.4

During the 2000s, the number of apprehended unaccompanied children who were subsequently put into removal proceedings and referred to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) averaged 6,700 annually and ranged from a low of about 4,800 in FY2003 to a peak of about 8,200 in FY2007.5

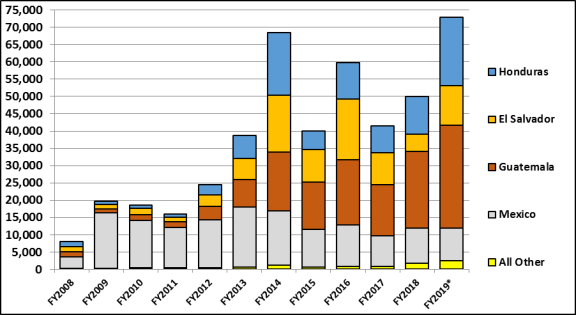

Starting in FY2009, the number of UAC apprehensions at the Southwest border was substantially higher compared to prior years and then increased consistently between FY2011-FY2014 (Figure 1). By FY2014, UAC apprehensions had reached a then-record of 68,541, leading some Members of Congress as well as the Obama Administration to characterize the issue as a humanitarian crisis.6 UAC apprehensions have since remained relatively high while fluctuating considerably (see "UAC Apprehension Levels" below).7

Reasons why unaccompanied minors migrate to the United States are often multi-faceted and difficult to measure analytically.8 During FY2014, when UAC apprehensions reached a then-record, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) analyzed several major factors contributing to UAC out-migration. These included violent crime, economic conditions, poverty, and the presence of transnational gangs. CRS also examined factors attracting UAC to the United States, such as the search for economic opportunity, the desire to reunite with family members, and incentives posed by U.S. immigration policies.9 Critics of the Obama Administration's policy response at the time suggested that the sizeable increase in UAC flows resulted from a perception of child-related, immigration policy loopholes.10 Critics often cited the 2008 statute11 that treats UAC from contiguous countries (Mexico and Canada) differently than UAC from noncontiguous countries (see "Customs and Border Protection" below). Those same criticisms have been reiterated more recently in response to the continued high level of UAC apprehensions at the Southwest border.12

This report opens with an analysis of UAC apprehensions data, discusses current policy on the treatment, care, and custody of the UAC population, and describes the responsibilities of each federal agency involved. The report then reviews both administrative and congressional actions to address UAC surges from FY2014 to the present.

UAC Apprehension Levels

UAC apprehensions began to increase substantially in FY2011, from 16,067, to 24,481 in FY2012, and 38,759 in FY2013 (Figure 1). In FY2014, CBP apprehended 68,541 UAC, more than in any of the previous six years and more than four times as many UAC as in FY2011. Since FY2014, UAC apprehensions have fluctuated considerably, declining to 39,970 in FY2015, increasing to 59,692 in FY2016, declining to 41,435 in FY2017, and increasing to 50,036 in FY2018. In the first 11 months of FY2019, they reached 72,873, a level that now exceeds the peak reached in FY2014.13

As noted above, figures presented for UAC apprehensions (between U.S. ports of entry) do not include figures for UACs who are deemed inadmissible (at U.S. ports of entry). The latter numbered 7,246 in FY2017, 8,624 in FY2018, and 4,235 for the first 11 months of FY2019.14 These totals represent 15%, 15%, and 5%, respectively, of all UAC apprehended and deemed inadmissible by CBP during that time.

Nationals of Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Mexico account for the majority of unaccompanied children apprehended at the Mexico-U.S. border (Figure 1).15 Apprehensions of Mexican UAC rose substantially from FY2008 to FY2009 and have fluctuated since then between roughly 9,000 and 17,000 UAC apprehensions per year. In contrast, the number of apprehensions of UAC from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador have increased substantially starting in FY2012, and have remained high since then. In FY2009, Mexican UAC accounted for 82% of all 19,668 UAC apprehensions that year, while the other three Central American countries accounted for 17%. By the first 11 months of FY2019, those proportions had reversed, with Mexican UAC comprising 13% of the 72,873 UAC apprehensions and UAC from the three Central American countries comprising 85%. This demographic shift has had major administrative impacts given the difference in how U.S. federal agencies process UAC originating from Mexico and Canada compared to their counterparts from the Northern Triangle (see "Processing and Treatment of Apprehended UAC" below).16

The majority of UAC apprehensions in FY2019 have occurred within the Rio Grande and El Paso border sectors (45% and 22%, respectively, in the first 11 months of FY2019).17 Data on UAC who were in ORR care each month indicate that during the first 11 months of FY2019, the female UAC proportion was 31% and the proportion of UAC under age 15 was 23%.18

Over the past decade, an increasing number of children have arrived at the Southwest border accompanied by an adult, a trend that in some cases has had implications for federal agencies processing unaccompanied children (see "Zero Tolerance Immigration Enforcement Policy" below). Apprehensions of "family units" (at least one alien minor with at least one parent or legal guardian) numbered 11,116 in FY201219 and, like UAC apprehensions, climbed substantially in subsequent years. In the first 11 months of FY2019, family unit apprehensions totaled 457,871, a level that surpasses the sum of all family unit apprehensions since FY2012 (394,762), the first year that CBP published family unit apprehension figures.20 Family units apprehended in FY2019 migrated almost entirely from the Northern Triangle.21

Legal Foundation of Current Policy

A court settlement and two laws most directly guide U.S. policy on the treatment and administrative processing of UAC: the Flores Settlement Agreement of 1997, the Homeland Security Act of 2002, and the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008.

During the 1980s, allegations of UAC mistreatment by the former Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)22 led to a series of lawsuits against the U.S. government that eventually resulted in a 1997 consent decree, the Flores Settlement Agreement (Flores Agreement).23 The Flores Agreement established a nationwide policy for the detention, treatment, and release of UAC and recognized the particular vulnerability of UAC as minors while detained without a parent or legal guardian.24 It required that immigration officials detaining minors provide (1) food and drinking water, (2) medical assistance in emergencies, (3) toilets and sinks, (4) adequate temperature control and ventilation, (5) adequate supervision to protect minors from others, and (6) separation from unrelated adults whenever possible. For several years following the Flores Agreement, criticism continued over whether the INS had fully implemented the drafted regulations.25

Five years later, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (HSA, P.L. 107-296) divided responsibilities for the processing and treatment of UAC between the newly created DHS and ORR. To DHS, the law assigned responsibility for the apprehension, transfer, and repatriation of UAC. To ORR, the law assigned responsibility for coordinating and implementing the care and placement of UAC in appropriate custody, reunifying UAC with their parents abroad if appropriate, maintaining and publishing a list of legal services available to UAC, and collecting statistical information on UAC, among other responsibilities.26 The HSA also established the statutory definition of UAC as unauthorized minors not accompanied by a parent or legal guardian. Despite these developments, criticism continued that the Flores Agreement had still not been fully implemented.

Responding to ongoing concerns that CBP was not adequately screening apprehended UAC for evidence of human trafficking or persecution, Congress passed the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA, P.L. 110-457). The TVPRA directed the Secretary of DHS, in conjunction with other federal agencies, to develop policies and procedures to ensure that UAC in the United States who are removed are safely repatriated to their countries of nationality or of last habitual residence.

The TVPRA set forth special rules for UAC from contiguous countries (i.e., Mexico and Canada), requiring that they be screened for evidence of human trafficking within 48 hours of apprehension. It mandated that unaccompanied children determined not to be human trafficking victims or not to have a fear of returning to their home country or country of last habitual residence be returned to their countries without additional penalties. It also required the Secretary of State to negotiate agreements with Mexico and Canada to manage the UAC repatriation process.

The TVPRA mandated that unaccompanied children from noncontiguous countries—as well as UAC from contiguous countries apprehended at the border and determined to be human trafficking victims or to have a fear of returning to their home country or country of last habitual residence, or who are apprehended away from the border—be transferred to the care and custody of ORR and placed in standard removal proceedings.

Processing and Treatment of Apprehended UAC

Several DHS agencies handle the apprehension, processing, and repatriation of UAC, while ORR handles the care and custody of UAC. The Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) in the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) conducts immigration removal proceedings.

CBP apprehends, processes, and temporarily holds UAC along U.S. borders. DHS's Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) physically transports UAC referred to ORR from CBP to ORR custody. ORR is responsible for sheltering UAC while they await an immigration hearing. DHS's U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is responsible for the initial adjudication of asylum applications filed by UAC after the children have been placed in removal proceedings. EOIR conducts immigration proceedings that determine whether UAC may be allowed to remain in the United States or must be deported to their home countries. ICE is responsible for repatriating UAC who are ordered removed from the United States. The following sections elaborate on each federal agency's role.

Customs and Border Protection

CBP's U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) and Office of Field Operations (OFO) are responsible for apprehending and processing unaccompanied children that arrive, respectively, between U.S. ports of entry (POEs) at or near the U.S. border, or at a POE.27 Most UAC are apprehended between POEs and are transported to USBP facilities. UAC apprehended at POEs by are escorted to CBP secondary screening areas.

When CBP confirms a foreign national under age 18 lacks U.S. lawful immigration status and is unaccompanied, the minor is classified as an unaccompanied alien child under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), processed for immigration violations, and the consulate that represents the child's country of citizenship is notified that DHS has detained him or her. CBP also collects and enters identifying information about the UAC into DHS databases.28 With the exception of Mexican and Canadian UAC who meet the three criteria discussed below, the TVPRA requires that USBP turn UAC over to ICE for transport to ORR within 72 hours of determining that the children meet the UAC definition.

As mentioned, the TVPRA directed the Secretary of Homeland Security, in conjunction with the Secretary of State, the Attorney General, and the Secretary of Health and Human Services, to develop policies and procedures to ensure that UAC are safely repatriated to their country of nationality or last habitual residence. Of particular significance, the TVPRA requires CBP to follow certain criteria for UAC who are nationals or habitual residents of a contiguous country.29 Although the screening provision only applies to UAC from contiguous countries, in March 2009 DHS issued a policy that, in essence, made the screening provisions applicable to all UAC.30

For UAC from contiguous countries, the INA requires that CBP personnel must screen each unaccompanied child within 48 hours of apprehension to determine if the following statements are true:

- the UAC has not been a victim of a severe form of trafficking in persons and there is no credible evidence that the minor is at risk of being trafficked upon return to his/her country of nationality or last habitual residence;

- the UAC does not have a fear of returning to his/her country of nationality or last habitual residence owing to a credible fear of persecution; and

- the UAC is able to decide independently to return voluntarily to his/her country of nationality or last habitual residence.31

If CBP determines that all three of the above statements are true about a UAC and, therefore, that he or she is inadmissible under the INA,32 the UAC must return to his or her home country. In such cases, CBP can permit the child to withdraw his/her application for admission,33 allowing the minor to return voluntarily to his or her country of nationality or last habitual residence.

The TVPRA contains provisions for the treatment of UAC from contiguous countries while in the care and custody of CBP, and it provides guidance for CBP personnel on repatriating minors. It requires the Secretary of State to negotiate agreements with Mexico and Canada for repatriation of their UAC that serve to protect the children from trafficking. These agreements, at minimum, must include provisions that (1) ensure the handoff of the minor children to an appropriate government official; (2) prohibit returning UAC outside of "reasonable business hours;" and (3) require border personnel of the contiguous countries be trained in the terms of the agreements.

Unaccompanied children from noncontiguous countries who are not subject to TVPRA's special repatriation procedures for UAC from Mexico or Canada (i.e., withdrawal of application for admission) are placed in standard removal proceedings pursuant to INA Section 240. The TVPRA specifies that in standard removal proceedings, UAC are eligible for voluntary departure under INA Section 240B at no cost to the child.34

As noted, OFO processes UAC apprehended at POEs at CBP secondary screening areas and UAC apprehended between POE are processed at USBP facilities. In January 2008, CBP issued a memorandum entitled "Hold Rooms and Short Term Custody."35 Following the issuance of this policy, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) criticized the Border Patrol for failing to uphold related provisions in current law and the Flores Agreement.36 In 2010, the DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued a report concluding that while CBP was in general compliance with the Flores Agreement, it needed to improve its handling of UAC.37 In 2015, CBP issued standards to address the interaction of its personnel with detained individuals.38 Yet, NGOs continued to criticize CBP for its treatment of UACs and other detainees.39 In 2018, a multi-disciplinary team from DHS's OIG conducted unannounced site inspections at nine CBP facilities within the El Paso and Rio Grande Valley border sectors in Texas. The OIG reported that the CBP facilities appeared to be operating in compliance with the 2015 standards.40

Immigration and Customs Enforcement

ICE is responsible for physically transferring UAC from CBP to ORR custody. ICE also may apprehend UAC in the U.S. interior during immigration enforcement actions. In addition, ICE represents the government in removal proceedings before EOIR.

ICE is also responsible for the physical removal of all foreign nationals, including UAC, who have final orders of removal or who have elected to voluntarily depart from the United States while in removal proceedings.41 ICE notifies the country of the foreign national being removed from the United States.42 To safeguard the welfare of all UAC, ICE has established policies for repatriating UAC, including

- returning UAC only during daylight hours;

- recording transfers by ensuring that receiving government officials or designees sign for custody;

- returning UAC through a port designated for repatriation;

- providing UAC the opportunity to communicate with a consular official prior to departure for the home country; and

- preserving the unity of families during removal.43

To implement a removal order for a UAC, however, the U.S. government must secure travel documents from his or her country. As such, the United States depends on the willingness of foreign governments to accept the return of their nationals. Each country has documentary requirements for repatriation of their nationals.44 While some allow ICE to use a valid passport to remove an alien (if the alien possesses one), others require ICE to obtain a specific repatriation document.45 According to one report, obtaining travel documents can become problematic, because countries may change their documentary requirements or object to a juvenile's return.46

Once the foreign country has issued travel documents, ICE arranges the UAC's transport. If the return involves plane travel, ICE personnel accompany the UAC to his or her home country. ICE uses commercial airlines for most UAC removals. ICE provides two escort officers for each UAC.47 Mexican UAC are repatriated in accordance with nine Local Repatriation Agreements (LRAs) covering the full length of the U.S.-Mexico border, which require that ICE notify the Mexican Consulate for each UAC repatriated. Additional specific requirements apply to each LRA (e.g., specific hours of repatriation).48

Office of Refugee Resettlement

The Unaccompanied Alien Children Program at ORR provides for the custody and care of unaccompanied alien minors who have been apprehended and referred by CBP or ICE, or who have been referred by other federal agencies. The TVPRA directed that HHS ensure that UAC "be promptly placed in the least restrictive setting that is in the best interest of the child."49 The HSA required that ORR develop a plan to ensure the timely appointment of legal counsel for each UAC,50 ensure that the child's interests are considered in decisions and actions relating to his or her care and custody, and oversee the infrastructure and personnel of UAC residential facilities, among other responsibilities.51 ORR also screens each UAC to determine if the child has been a victim of a severe form of trafficking in persons, if there is credible evidence that the child would be at risk if returned to his/her country of nationality or last habitual residence, and if the child has a possible claim to asylum.52

ORR arranges to house the child in one of its network of shelters while seeking to place him or her with a sponsor, typically a family member. According to ORR, the majority of the youth are cared for initially through a network of about 170 state-licensed shelters in 23 states.53 These ORR-funded and supervised care providers offer classroom education, mental and medical health services,54 case management, and socialization and recreation. ORR oversees different types of shelters to accommodate unaccompanied children with different circumstances, including standard shelter care, secure care, and transitional foster care.55 A juvenile may be held in a secure facility only if he or she

- is charged with criminal or delinquent offense,

- threatens or commits violence, displays unacceptably disruptive conduct in a shelter,

- presents an escape risk,

- is in danger and is detained for his/her own safety, or

- is part of an influx of minors that results in insufficient bed space at standard facilities.56

ORR shelter personnel also facilitate the release of UAC to family members or other sponsors who are able to care for them.57 The Flores Agreement outlines the following preference ranking for sponsor types: (1) a parent; (2) a legal guardian; (3) an adult relative; (4) an adult individual or entity designated by the child's parent or legal guardian; (5) a licensed program willing to accept legal custody; or (6) an adult or entity approved by ORR.58 Removal proceedings continue even when UAC are placed with parents or other relatives.

In making these placement determinations, ORR conducts an investigation, which includes criminal background and sex-offender registry checks. It also confirms the identity of the adult assuming legal guardianship for the UAC, ensures that the adult does not have a record of abusive behavior and ensures the sponsor's ability to provide for the physical and mental well-being of the child.59 ORR has also begun collecting biometric (fingerprint) and immigration legal status information from sponsors (see "Trump Administration Action" below). ORR may consult with the consulate of a UAC's country of origin as well as interview the UAC to ensure he or she agrees with the proposed placement. In a range of circumstances, ORR may require a home study as an additional precaution.60 In addition, the parent or guardian is required to complete a Parent Reunification Packet to attest that he or she agrees to take responsibility for the UAC and provide proper care.61 ORR reports that most children it serves are reunified with family members.62 For the second quarter of FY2019, ORR reported that children spent an average of 47 days in ORR shelters, an increase from the 34-day average in January 2016 but a decline from the 93-day average in November 2018.63

In cases where a sponsor cannot be located, UAC are placed in a long-term care setting, such as community based foster care or extended care group home.64 According to ORR, long-term foster care involves "ORR-funded community-based foster care placements and services to which eligible unaccompanied alien children are transferred after a determination is made that the child will be in ORR custody for an extended period of time. Unaccompanied alien children in ORR long-term foster care typically reside in licensed foster homes, attend public school, and receive community-based services."65

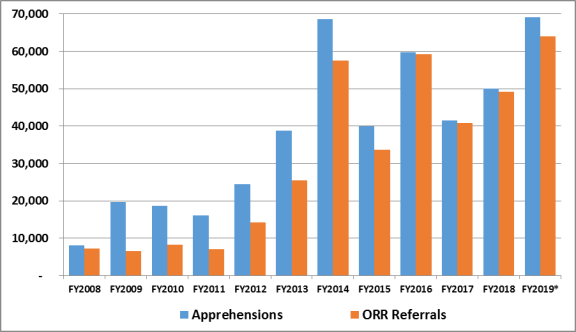

Figure 2 shows both annual UAC apprehensions and annual referrals of unaccompanied children to ORR since FY2008. As expected, as the number of apprehensions increase, so to do referrals to ORR, but in recent years, as children from noncontiguous countries have dominated the share of all UAC apprehensions, the percentage of UAC apprehended who are referred to ORR has increased. In FY2009, when unaccompanied children from the three Northern Triangle countries comprised 17% of all UAC apprehensions, the proportion of children referred to ORR was 34% of total apprehensions. In the first 10 months of FY2019, when unaccompanied children from Northern Triangle countries comprised 85% of all UAC apprehensions, the proportion of UAC referred to ORR was 92%. As noted above, not all UAC are referred to ORR; for instance, many UAC from contiguous countries voluntarily return home.

|

Figure 2. UACs Apprehended and Referred to ORR Custody, FY2008-FY2019* |

|

|

Source: Apprehensions: See sources for Figure 1 above; Referrals: FY2008-FY2018: HHS, Administration for Children and Families, Fiscal Year 2019, Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, p. 43; FY2019: HHS, "Latest UAC Data—FY2019," September 6, 2019, https://www.hhs.gov/programs/social-services/unaccompanied-alien-children/latest-uac-data-fy2019/index.html. Notes: *The FY2019 figures represent the first 10 months of the fiscal year, through July 31, 2019. FY2019 ORR referral figure computed by multiplying ORR 30-day average number of UAC referrals for each month by that month's number of days and summing those products across the first 10 months of the fiscal year. |

The sizable increases in UAC referrals since FY2008 have challenged ORR to meet the demand for its services while maintaining related child welfare protocols and administrative standards.66 These challenges attracted public attention in January 2016 when a Senate investigation indicated that in FY2014, some UAC, who originally were sponsored by distant relatives and parental-approved guardians, ended up being forced to work in oppressive conditions on an Ohio farm. The related Senate report outlined a range of what it characterized as serious deficiencies related to the safe placement of children with distant relatives and unrelated adults as well as post-placement follow-up.67 During the Senate Homeland Security Committee hearing that followed, HHS officials acknowledged limitations of their screening and post-placement follow-up procedures for such sponsors. They also contended that HHS liability terminates once custody of an unaccompanied minor is handed over to a sponsor.68 According to news reports, DHS and HHS agreed to establish new guidelines within a year to prevent episodes such as the farm-related trafficking incident from reoccurring, an outcome that the GAO reported in 2018 remained unfulfilled.69

In April 2018, during a Senate Homeland Security Committee hearing, an HHS official testified that ORR was unable to account for 1,475 of the 7,635 unaccompanied children placed with sponsors between October and December of 2017.70 According to HHS, ORR began voluntarily conducting post-placement outreach as a "30-day checkup" to ensure that children and their sponsors did not require additional services even though HHS maintained that it had no legal responsibility to locate UAC after placement with sponsors. Some observers suggested that many nonresponsive sponsors may be residing in the United States illegally and may be reluctant to respond to official post-placement outreach.71 A 2016 HHS OIG report found a similar proportion of UAC unaccounted for, post-placement.72

Some observers have raised concerns over ORR's handling of many children who "age out" of UAC status once they reach age 18. Recent reports have described incidents of children being abruptly taken into ICE custody on or soon after their 18th birthdays and placed in adult immigration detention.73 Such treatment has led to at least one lawsuit.74 Some have attributed this practice to a lack of ORR transition planning for children who will soon reach age 18.75

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

As mentioned, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is responsible for the initial adjudication of asylum applications filed by UAC.76 If either CBP or ICE determines that an apprehended child is a UAC and transfers him/her to ORR custody, USCIS generally will take jurisdiction over any asylum application, even where evidence shows that the child reunited with a parent or legal guardian after CBP or ICE made the UAC determination. As of enactment of the TVPRA, USCIS also has initial jurisdiction over asylum applications filed by UAC with pending claims in immigration court, with cases on appeal before the Board of Immigration Appeals, or with petitions under review with federal courts. UAC must appear at any hearings scheduled in immigration court, even after petitioning for asylum with USCIS.77

Executive Office for Immigration Review

The Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) is responsible for conducting removal proceedings and adjudicating immigration cases.78 Generally, an immigration removal proceeding allows the foreign national and the U.S. government to present testimony so that the immigration judge can determine whether the foreign national is removable or qualifies for some type of relief from removal (i.e., the alien is permitted to remain in the United States either temporarily or permanently). The TVPRA requires that HHS ensure, "to the greatest extent practicable," that UAC have access to legal counsel. It also authorizes HHS to appoint independent child advocates for child trafficking victims and other vulnerable unaccompanied children.79

EOIR's policies for conducting UAC removal hearings are intended to ensure that children understand the nature of the proceedings, effectively present evidence about their cases, and have appropriate assistance. The policy guidelines discuss possible adjustments to create "an atmosphere in which the child is better able to participate more fully in the proceedings." Under these guidelines, immigration judges should

- establish special dockets for UAC that are separate from the general population;

- allow child-friendly courtroom modifications (e.g., judges not wearing robes, allowing the child to have a toy, permitting the child to testify from a seat rather than the witness stand, allowing more breaks during the proceedings);

- provide courtroom orientations to familiarize the child with the court;

- explain the proceedings at the outset;

- prepare the child to testify;

- employ child-sensitive questioning; and

- encourage the use of pro bono legal counsel if the child is not represented.80

On July 9, 2014, in response to the UAC surge, EOIR issued new guidelines that prioritized cases involving unaccompanied children and nondetained families above other cases in the immigration courts and placed these cases on the same level as those of detained aliens.81 EOIR has since revised these priorities three times. Its most recent guidance, issued January 17, 2018, does not prioritize UAC cases.82

Table 1. UAC Initial Case Completion by Outcome and Legal Representation

(FY2018 and first half of FY2019)

|

Outcome |

Cases With Legal Representation |

Cases Without Legal Representation |

Total Cases |

|||

|

Cases |

% of Total |

Cases |

% of Total |

Cases |

% of Total |

|

|

Removal |

3,721 |

39% |

9,179 |

90% |

12,900 |

65% |

|

Termination |

3,836 |

40% |

571 |

6% |

4,407 |

22% |

|

Voluntary Departure |

1,444 |

15% |

460 |

4% |

1,904 |

10% |

|

Relief Granted |

458 |

5% |

7 |

0% |

465 |

2% |

|

Other |

84 |

1% |

9 |

0% |

93 |

0% |

|

Total |

9,543 |

100% |

10,226 |

100% |

19,769 |

100% |

Source: Executive Office for Immigration Review, unpublished data provided to CRS, May 13, 2019.

Notes: Figures may not sum to totals presented because of rounding.

CRS reviewed recent EOIR data covering October 1, 2017, through March 31, 2019 (Table 1). Over this 18-month period, EOIR received 38,060 new UAC cases and completed 19,769 cases.83 Of the total completed cases, 12,900 resulted in removal orders, of which 10,025 (78%) were issued in absentia, meaning that the UAC had not shown up to the hearing. Of the other total completed cases that did not result in a removal order, 4,407 were terminated,84 1,904 resulted in voluntary departure,85 and 93 resulted in other outcomes.86 In 465 cases (2% of all initial case completions for this period), children received some form of immigration relief. Typical forms of immigration relief for UAC include asylum, special immigrant juvenile (SIJ) status for abused, neglected, or abandoned children who are declared dependent by state juvenile courts,87 and "T nonimmigrant status" for victims of trafficking.88

Outcomes varied considerably depending upon whether children received legal representation. Of the 10,226 children without legal representation, 90% (9,179) were ordered removed, and of those, 91% (8,375) were removed in absentia. In contrast, of the 9,543 children with legal representation, only 39% (3,721) were ordered removed, and of those, only 44% (1,650) were removed in absentia. Similarly, 5% of represented children (458) received some form of immigration relief compared with a handful of nonrepresented children (7).

Administration and Congressional Action

The Obama and Trump Administrations, as well as Congress, have taken action since 2014 to respond to the increase in UAC apprehensions. During 2014, when UAC apprehensions reached a record at the time, the Obama Administration developed a working group to coordinate efforts of the federal agencies involved in responding to the issue. The Obama Administration also temporarily opened additional shelters and holding facilities to accommodate the large number of UAC apprehended at the border, initiated programs to address root causes of child migration from Central America to the United States, and requested funding from Congress.

The Trump Administration, also facing high levels of UAC and family unit apprehensions, has taken steps to provide housing for unaccompanied minors while also attempting to reduce both the flow of migrants illegally crossing the Southwest border and the number of families who file meritless asylum claims to gain U.S. entry. The Administration has also implemented a biometric and biographic information-sharing agreement between ORR and DHS that is intended to ensure greater child safety and immigration enforcement.

Obama Administration Action

In response to the surge of UAC apprehensions, the Obama Administration in June 2014 announced the formation of a Unified Coordination Group headed by Craig Fugate, the Administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), with representatives from key agencies.89 The FEMA administrator's role was to "lead and coordinate Federal response efforts to ensure that Federal agency authorities and the resources granted to the departments and agencies under Federal law … are unified in providing humanitarian relief to the affected children, including housing, care, medical treatment, and transportation."90

From the outset of the 2014 surge, CBP maintained primary responsibility for border security operations at and between ports of entry and, working with ICE, provided for the care of unaccompanied children in temporary DHS custody.91 DHS coordinated with the Departments of Health and Human Services, State, and Defense, as well as the General Services Administration and other agencies, to ensure a coordinated and prompt response within the United States in the short term, and in the longer term to work with migrant-sending countries to undertake reforms to address the causes behind the recent flows.92

To manage the UAC influx, ORR relied upon its network of shelters operated by nonprofit organizations with experience providing UAC-oriented services (e.g., medical attention, education). HHS also coordinated with the Department of Defense (DOD), which temporarily made facilities available for UAC shelter at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, Naval Base Ventura County, California, and Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Arrangements to house UAC at all three sites ended August 2014.93 Subsequently, two other DOD locations, Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico and Fort Bliss, Texas, were used to shelter UAC in early 2016 and in late 2016-early 2017, respectively.94

To provide children entering the immigration court system with legal representation during removal proceedings, EOIR partnered with the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS), a federal agency that administers AmeriCorps.95 Together they created "Justice AmeriCorps" in 2015, a grant program that enrolled approximately 100 lawyers and paralegals as AmeriCorps members.96 In FY2014, DOJ's Legal Orientation Program, tasked with providing legal orientation presentations to sponsors of unaccompanied children in EOIR removal proceedings, served over 12,000 custodians for children released from ORR custody.97

In June 2014, DHS initiated a program to work with the Central American countries on a public education campaign to dissuade UAC from attempting to migrate illegally to the United States and a range of other issues.98 Additional Administration initiatives include partnering with Central American governments to combat gang violence, strengthening citizen security, spurring economic development, and supporting the reintegration and repatriation of returned citizens.99

In September 2014, the Obama Administration announced a new Central American Minors (CAM) refugee program to provide a safe, legal, and orderly alternative to U.S. migration that would not serve as a pathway for unaccompanied children to join undocumented relatives in the United States.100 The program, targeting children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, was meant to discourage them from migrating to the United States, by enabling at least some of them to be considered for refugee status at home. The Trump Administration terminated the CAM program in August 2017.101

Trump Administration Action

Actions by the Trump Administration regarding unaccompanied children have largely emphasized efforts to provide housing for unaccompanied children as well as reduce the number of adults migrating to the United States with children as "family units" in the past year.102 They include increasing the use of temporary influx shelters in response to an increasing UAC caseload, sharing more sponsor information between ORR, CBP, and ICE, reclassifying children whose parents are prosecuted for illegal entry as UAC and housing them in ORR shelters, and proposing new regulations to expand the amount of time children can spend in detention beyond the current 20-day limit.

Increasing UAC Shelter Capacity

To respond to surges of unaccompanied children arriving at the Southwest border alone or as part of family units who were subsequently separated, ORR has employed temporary "influx care facilities"103 to supplement its existing network of state-licensed shelters. These facilities tend to be considerably larger than standard ORR-supervised shelters and are typically opened on federally owned or leased properties (in which case, the facility is not subject to State or local child care licensing standards). To date, ORR has opened, and subsequently closed, three such shelters, in Tornillo, Texas (Tornillo shelter), Homestead, Florida (Homestead shelter), and Carrizo Springs, Texas. At the end of December 2018, ORR was housing more than 14,000 children in all of its shelters (including influx shelters),104 an increase from a reported 9,200 children in January 2017.105 As of July 31, 2019, ORR had an average of 9,338 children in its care, a maximum number of 15,897 beds, and an average occupancy rate of 70%.106

Tornillo Shelter, Texas

Located 35 miles southeast of El Paso on the Mexico border, the Tornillo shelter operated from June 2018 until January 2019. It was run by a private firm, BCFS Health and Human Services (Emergency Management Division), a company known for providing emergency services following major disasters like Hurricane Katrina.107 Even though some reported that Tornillo was opened in response to the demand for UAC shelter space prompted by the Trump Administration's zero tolerance policy,108 HHS clarified that children separated as the result of border enforcement actions were specifically not sheltered at the Tornillo shelter.109 BCFS officials reportedly expected that the shelter would remain open only for several weeks, but ORR extended that timeframe, as the number of apprehended unaccompanied children increased during the second half of 2018.110 By September, conventional ORR shelters were reportedly reaching their maximum capacity, and older children were transferred to Tornillo just prior to their expected release to sponsors.111

Concerns of child welfare advocates centered on the shelter's size and remote location, the children's duration of stay,112 and ORR's process for transferring the children to the facility.113 In November 2018, HHS's OIG issued a memorandum in which it identified significant vulnerabilities regarding what it considered as insufficient personnel background checks and an insufficient number of mental health clinicians at Tornillo.114 The following month, HHS responded to the OIG describing actions taken in response to the report's findings.115

In December 2018, in response to the growing number of UAC in ORR custody, as well as a reported request from shelter operator BCFS,116 the Administration relaxed the requirements of its information collection and sharing policy with regard to potential UAC sponsors. (See "Information Sharing between ORR, ICE, and CBP" below). According to one news report, the number of children housed in all ORR-supervised shelters subsequently dropped substantially by mid-January.117

Homestead Shelter, Florida

The Homestead shelter is operated by Comprehensive Health Services Incorporated (CHSI), a subsidiary of Caliburn International Corporation. Located in Florida about 30 miles south of Miami, it is currently the largest UAC facility operating in the United States and the only one operated by a for-profit corporation. Like the former Tornillo shelter, it is located on federal land and is not subject to local or state regulations governing child shelters.118

HHS began using Homestead as a temporary shelter for unaccompanied children in June 2016 and sheltered approximately 8,500 children over approximately 10 months until it closed temporarily in April 2017.119 In March 2018, the Homestead shelter reopened.120 In February 2019, it reportedly added 1,000 beds in response to the closing of the Tornillo shelter.121 From March 2018 to February 26, 2019, the shelter housed more than 6,300 unaccompanied children and oversaw 4,850 sponsor placements. As of February 26, 2019, Homestead was housing about 1,600 children who had spent an average of 58 days in the shelter.122 According to HHS, Homestead contains 1,700 beds and can expand to as many as 2,350 beds.123

ORR maintains that the same policies and range of services available to unaccompanied children at its conventional ORR-supervised shelters were found at Homestead. Some news reports cited a congressional delegation who characterized conditions at the shelter as inhumane and unsuitable for children.124 Other immigration observers refuted that characterization.125

On August 3, 2019, ORR announced that the Homestead shelter had been closed and that all children in it had been placed with sponsors or relocated to the network of state-licensed UAC shelters. As of this report date, there are no children residing in any influx care facility, although reportedly, the facility may open again.126

Carrizo Springs, Texas

On June 7, 2019, the Associated Press reported that ORR would be opening up a new temporary influx shelter in Carrizo Springs, Texas, about 120 miles southwest of San Antonio. The facility, which sits on government-leased land and once housed oil field workers, can reportedly house as many as 1,600 children.127 It is operated by BCFS, the same privately run nonprofit organization that operated the Tornillo facility described above.128 Initially, the facility was operating at substantially below capacity,129 and less than a month after it opened, it was closed.130

Influx Shelters on U.S. Military Installations

As it did during the Obama Administration, HHS has again coordinated with DOD to explore and possibly open temporary influx shelter facilities on U.S. military installations. Based on the anticipated number of UAC referrals, HHS is again activating a facility at Fort Sill Army Base near Lawton, OK, as a temporary emergency influx shelter. The facility will have bed capacity for approximately 1400 children. As of the date of this report, ORR had not indicated when the facility would open.131

Information Sharing between ORR, ICE, and CBP

As noted, ORR tries to find sponsors, typically family members, for UAC to live with while they await their removal proceedings. For years, immigration enforcement advocates and some Members of Congress decried that an indeterminate but sizeable proportion of UAC sponsors were unauthorized aliens, and that ORR neither collected, nor shared with DHS, information on sponsors' legal status. Immigration advocates contended that such information sharing mandates would discourage the sponsorship of unaccompanied children.

In April 2018, ORR, ICE, and CBP entered into a memorandum of agreement (MOA) providing for the sharing of information from the time that UAC are referred by either CBP or ICE to ORR, through their time in ORR custody, and upon their release from ORR custody to a sponsor.132 Under the MOA, ORR agreed to collect and share with ICE and CBP information about unaccompanied children in their custody, such as, their arrests, unauthorized absences, death, abuse experienced, and violent behavior, as well as age determination findings and gang affiliation information. The MOA also mandated the sharing of information about potential sponsors and all adults living with them. Such information included citizenship, immigration status, criminal history, and immigration history.

According to the agreement, ORR would share with ICE this information as well as biographic and biometric (fingerprint) information about potential sponsors and their household members. In return, ICE would provide ORR with the summary criminal and immigration histories of the potential sponsors and all adult members of their households so that ORR could make more complete suitability determinations regarding the UAC sponsors.

The Trump Administration and immigration enforcement advocates described the policy as necessary to ensure the safety and well-being of children placed with sponsors.133 Immigrant advocates contended that the new policy would increase the number of children that remain in federal custody while they seek immigration relief, increase detention costs, and extend family separation.134 They also questioned the relevance of an adult's immigration status to a child's safe placement with a sponsor.135

After the policy was implemented, ICE began to arrest unauthorized aliens who came forward to sponsor unaccompanied children. From July through November 2018, ICE is reported to have arrested 170 potential sponsors—109 of whom had no previous criminal histories—and placed them in deportation proceedings.136 Matthew Albence, a senior ICE official who testified before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee in September 2018, confirmed these activities and asserted that an estimated 80% of active UAC sponsors and family members living with them were residing in the country illegally.137

Some have linked the new information-sharing agreement with increases in the average number of days unaccompanied children spend in ORR custody.138 During FY2015 and FY2016, unaccompanied children spent an average of 34 and 38 days in ORR custody, respectively.139 In FY2017, that average increased to 48 days. In FY2018, the figure increased to 60 days, and for the first three months of FY2019, it stood at 89 days140 before declining to 47 days as of August 2019.141 Other factors, such as the number of children that require shelter, may affect the time unaccompanied children spend in ORR custody, making it difficult to attribute changes in average ORR custody time solely to the information-sharing MOA between ORR and DHS.

As noted above, in response to concerns about the increased average length of time that UAC are spending in ORR custody, as well as a reported request from shelter operator BCFS,142 the Administration in December 2018 relaxed some requirements of its information collection and sharing policy. The new policy, which remains current, continues to require background checks for all members of the sponsor's household over age 18, but it limits the collection and sharing with DHS of fingerprint data to sponsors only, not other adults in the sponsor's household.143

Zero Tolerance Immigration Enforcement Policy

On May 7, 2018, DOJ implemented a "zero tolerance" enforcement policy for persons who entered the United States illegally between ports of entry. Under the zero tolerance policy, DOJ sought to prosecute all adult aliens apprehended crossing the border illegally, without making exceptions for asylum seekers or migrants with minor children. Close to 3,000 children are known to have been separated as the result of the zero tolerance policy.144 DOJ's policy represented a change in the level of enforcement of an existing statute rather than a change in statute or regulation.145

Criminally prosecuting adults (regardless of nationality) makes them subject to detention in federal criminal adult detention facilities. Under the zero tolerance policy, when a parent entered the U.S. illegally with a minor and was detained in criminal detention, DHS treated the child as an unaccompanied alien child and transferred him or her to ORR custody. Once the parent's criminal prosecution for illegal entry or reentry ended and any sentence was served, the parent could be reunited with the child.

For families who arrived at a U.S. port of entry and request asylum, the process was different. While DOJ and DHS have broad statutory authority to detain alien adults,146 alien children must be detained according to guidelines established in the Flores Agreement, the HSA, and the TVPRA described above. A 2015 judicial ruling held that children could remain in family immigration detention (as distinct from immigration detention for single adults or ORR shelters for unaccompanied children) for no more than 20 days.147 If parents are not released with them, DHS reclassifies the children as UAC and transfers them to ORR for care and custody.

Following mostly critical public reaction, President Trump issued an executive order on June 20, 2018, mandating that DHS maintain custody of alien families during the pendency of any criminal trial or immigration proceedings.148 CBP subsequently stopped referring most illegal border crossers to DOJ for criminal prosecution. ICE continued, family detention space permitting, to detain family units for up to 20 days. A federal judge then issued an injunction prohibiting family separation and requiring that all separated children be promptly reunited with their families.149

Reuniting families presented a considerable challenge to ORR, CBP, and ICE. Immigrant advocates criticized the Administration's efforts at family reunification for what some described as an uncoordinated implementation process that lacked an effective plan to reunify separated families.150 Reports subsequently issued by the OIG for both DHS and HHS indicated that CBP had omitted information about the separated children's family members after classifying them as unaccompanied alien children and referring them to ORR, and described limitations with its information technology system for tracking such children.151 The resulting delay in reunifying families meant that two to three thousand additional children spent an indeterminate amount of additional time in ORR shelters.152 HHS reprogrammed or transferred $385 million from other HHS programs to ORR, reportedly to cover the additional expenses stemming from the zero tolerance policy.153

Proposed Regulations to Replace the Flores Settlement Agreement

On September 7, 2018, DHS and HHS jointly published proposed regulations on the apprehension, processing, care, and custody of alien children that would replace the Flores Agreement.154 The proposed regulations mainly address detention for children within family units but also contain some provisions affecting unaccompanied children. While ostensibly adhering to the basic purpose of the Flores Agreement "in ensuring that all juveniles in the government's custody are treated with dignity, respect, and special concern for their particular vulnerability as minors," the rule would amend current licensing requirements for family residential centers to allow families to be detained together during the full length of their immigration proceedings. This rule would thereby allow ICE to overcome the 20-day immigration detention restriction for families that was imposed as part of the Flores Agreement. The final rule was issued on August 23, 2019,155 and lawsuits were subsequently filed to prevent its enactment.156

Opponents of the proposed rule have criticized it for potentially allowing children to be indefinitely detained with their parents in unsafe and inappropriate conditions.157 Supporters contend that, in its current form, the Flores Agreement incentivizes unlawful migration to the United States and the filing of meritless asylum claims.158

Congressional Action

When UAC apprehensions reached a then-record in 2014, policymakers initially focused on whether the various agencies responding to it had adequate funding. As the surge began to wane, congressional attention shifted to mechanisms to prevent its recurrence. In recent years, congressional focus has emphasized funding ORR operations. ORR's UAC program is one line item in its Refugee and Entrant Assistance account.159 Legislative proposals to either limit the number of UAC admissions or facilitate their entry and care have been introduced in the House and the Senate but none have been passed into law. Described below are funding requests, legislative action regarding funding, and executive branch budget execution, including budgetary transfers, reprogramming of funds, and reallocations since FY2015.

FY2015

In its FY2015 budget released in March 2014, the Obama Administration did not request funding increases to address the UAC surge. However, on May 30, 2014, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) updated its cost projections for addressing the growing UAC population. It requested $2.3 billion for FY2015 for ORR's UAC program and $166 million for DHS for CBP overtime, contract services for care and support of UAC, and transportation costs.160

On July 8, 2014, the Administration requested a $3.7 billion supplemental appropriation for FY2015, much of which was directly related to addressing the UAC surge The request included $433 million for CBP, $1.1 billion for ICE, $1.8 billion for HHS's UAC program, $64 million for DOJ, and $300 million for the Department of State (DOS).161

In December 2014, the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2015 (P.L. 113-235) provided nearly $1.6 billion for ORR's Refugee and Entrant Assistance Programs for FY2015, with the expectation that most of these funds would be directed toward the UAC program. In addition, P.L. 113-235 included a new provision allowing HHS to augment appropriations for the Refugee and Entrant Assistance account by up to 10% through transfers from other discretionary HHS funds.162

In March 2015, the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2015 (P.L. 114-4) provided $3.4 billion to ICE for detection, enforcement, and removal operations, including transportation of unaccompanied alien children. The act required that DHS estimate the number of UAC apprehensions expected in the budget year and the number of necessary agent or officer hours and related costs. It also provided for budgetary flexibility through the optional reprogramming of funds.163

FY2016

In its FY2016 budget, the Obama Administration requested contingency funding, in addition to base funding, for several agencies in the event of another surge of unaccompanied children. For ORR's UAC program, the Administration requested $948 million in base funding (the same as FY2015) and $19 million in contingency funding.164 Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) which met the base funding request but appropriated no monies for contingency funding.165

For FY2016 DHS funding, the Administration requested $203.2 million in base funding and $24.4 million in contingency funding for CBP for costs associated with the apprehension and care of unaccompanied children.166 The Administration requested $2.6 million in contingency funding for ICE for transportation costs associated with UAC apprehensions if such apprehensions exceeded those in FY2015.167 Neither the Senate168 nor the House169 committee-reported FY2016 DHS appropriations bills would have funded these requests. The Administration requested an additional $50 million (two-year funding spread over FY2016 and FY2017) for EOIR to expand a program to provide legal representation to UAC.170 Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) which did not provide this additional EOIR funding request. In the law, Congress provided CBP with $204.9 million in base funding but did not provide the contingency funding requested. Congress provided ICE with $24.3 million in UAC transportation funding but did not fund the contingency transportation request.171

FY2017

For FY2017, the Trump Administration requested $1.3 billion for ORR for unaccompanied children. This UAC program request included $1.2 billion in base funding. It also included contingency funding, which, if triggered by larger than expected caseloads, would start at $95 million and could expand to $400 million.172 For UAC operations within DHS, the Administration requested $13.2 million for transportation and removal activities, including $3 million in contingency funding; and $217.4 million for CBP, including $5.4 million in contingency funding.

Congress, in turn, passed two continuing resolutions (CRs) to fund ORR for FY2017. Congress first passed the Continuing Appropriations and Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2017, and Zika Response and Preparedness Act (P.L. 114-223), which funded ORR, ICE, and CBP from October 1, 2016, through December 9, 2016, at the same level and under the same conditions as FY2016, less an across-the-board reduction of 0.496%. Under the terms of the CR, HHS retained its authority from the 2016 bill (P.L. 114-113) to augment this account by up to 10% using transfers from other HHS accounts. HHS reportedly used this authority to transfer $167 million into the account in November 2016, due to a surge in the UAC caseload.173

Prior to congressional consideration of a second CR, the Administration requested that any new CR include a provision providing a higher operating level for the Refugee and Entrant Assistance account. This stemmed from an increased caseload resulting from the growth in the number of unaccompanied children from Central American countries apprehended at the Southwest border. The Administration requested funding for the account at an annual rate of $3.9 billion, of which $2.9 billion would be used for unaccompanied children. However, the Administration separately noted that it might be possible to meet caseload demands at a lower level than requested, indicating that at a minimum this would require $500 million for the Refugee and Entrant Assistance account, of which $430 million would be used for unaccompanied children, as well as additional transfer authority in the event of higher than anticipated costs.174

Congress then passed a second FY2017 CR, the Further Continuing and Security Assistance Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 114-254), which funded most federal agencies through April 28, 2017.175 It funded ORR programs at the same level and under the same conditions as in FY2016, minus an across-the-board reduction of 0.1901%.176 However, this CR also contained a special provision authorizing HHS to transfer up to $300 million to fund ORR programs dedicated to unaccompanied children as of February 1, 2017.177 After March 1, 2017, if the UAC caseload for FY2017 exceeded by 40% or more the UAC caseload for the comparable period in FY2016, the CR appropriated up to an additional $200 million in new funding.

Congress subsequently passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), which funded most federal agencies for the remainder of FY2017. It funded ORR programs at the same level and under the same conditions as in FY2016. P.L. 115-31 rescinded the provision in P.L. 114-254 to provide up to $200 million in new funding if the UAC caseload met the conditions described above. Ultimately, final funding approved for ORR's unaccompanied alien children program for FY2017, including transfers, totaled $1.4 billion.178

FY2018

For FY2018, the Trump Administration requested $948 million for ORR's UAC program. The request included an option to augment appropriations for the Refugee and Entrant Assistance account by up to 10% through transfers from other discretionary HHS funds. The request excluded contingency funding provisions found in several previous years' requests.179

Congress responded by passing the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), which funded the Refugee and Entrant Assistance account at $1.9 billion. Transfers permitted by Congress within HHS to this account totaled $186 million. Within the account, funding for the Unaccompanied Alien Children program was increased to $1.3 billion (+$355 million relative to FY2017).180 Final actual spending for the UAC program for FY2018, including permissible transfers and reprogramming, was $1.6 billion.181

FY2019

For FY2019, the Trump Administration requested $1.0 billion for ORR's UAC program.182 The Administration further requested the option to augment appropriations for the Refugee and Entrant Assistance account by up to 10% through transfers from other discretionary HHS funds. The budget also created a $200 million contingency fund if caseloads met certain conditions.

Congress responded by passing the Department of Defense and Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations Act, 2019 and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-245), which funded HHS's Refugee and Entrant Assistance account at $1.9 billion. Within the account, funding for the Unaccompanied Alien Children program was $1.3 billion, the same as for FY2018.183

On May 17, 2019, OMB notified Congress that it anticipated a budget shortfall for the UAC program of $2.9 billion because of a 57% increase in the number of UAC referrals to ORR compared to the same time period during the previous year. The notification indicated that HHS had already reallocated $286 million to the UAC program using the HHS Secretary's transfer authority pursuant to P.L. 115-245 and had reprogrammed $99 million within the Refugee and Entrant Assistance account.184 Congress responded by passing the Emergency Supplemental Appropriations for Humanitarian Assistance and Security at the Southern Border Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-26) which contained nearly $2.9 billion in emergency-designated appropriations for the Refugee and Entrant Assistance account. These funds were primarily intended to support the growing demands placed on the UAC program. Among the bill's many provisions, it required HHS to reverse any reprogramming within the account that had been carried out pursuant to the OMB notification.

FY2020

For FY2020, the Trump Administration has requested $1.3 billion, the same as the FY2019 appropriation. The Administration also requests transfer authority to allow additional funding of up to 20% of the appropriated amount into the account which is above the 15% maximum that Congress provided in FY2019. The budget also includes a request for a mandatory contingency fund capped at $2.0 billion over three years, probabilistically scored at $738 million, if caseload trends meet certain conditions.185

H.R. 2740, the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2020, recommends appropriating $1.8 billion for ORR's UAC program, $500 million above the FY2019 enacted and FY2020 budget request levels.186