Introduction

This report provides background information and analysis on the following topics:

- Various aspects of U.S.-Turkey relations, including (1) Turkey's strategic orientation; (2) U.S./NATO cooperation and how a Turkish purchase of an S-400 air defense system from Russia has affected Turkey's participation in the F-35 aircraft program and could lead to sanctions; and (3) the situation in northern Syria, including with Kurdish-led militias. The S-400/F-35 issue has attracted close congressional scrutiny, and how the United States and Turkey handle the issue could have broad implications for bilateral relations.

- Domestic Turkish developments, including politics under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's largely authoritarian and polarizing rule, and significant economic concerns.

For additional information, see CRS Report R41368, Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas.

|

|

Geography |

Area: 783,562 sq km (302,535 sq. miles), slightly larger than Texas |

|

People |

Population: 81,257,239 (2018) Most populous cities: Istanbul 14.8 mil, Ankara 5.3 mil, Izmir 4.2 mil, Bursa 2.9 mil, Antalya 2.3 mil (2016) % of Population 14 or Younger: 24.3% Ethnic Groups: Turks 70%-75%; Kurds 19%; Other minorities 7%-12% (2016) Religion: Muslim 99.8% (mostly Sunni), Others (mainly Christian and Jewish) 0.2% Literacy: 96.2% (male 98.8%, female 93.6%) (2016) |

|

Economy |

GDP Per Capita (at purchasing power parity): $27,391 Real GDP Growth: -1.7% Inflation: 16.1% Unemployment: 14.3% Budget Deficit as % of GDP: 2.3% Public Debt as % of GDP: 28.0% Current Account Deficit as % of GDP: 0.7% International reserves: $92 billion |

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by Hannah Fischer using Department of State boundaries (2011); Esri (2014); ArcWorld (2014); DeLorme (2014). Fact information (2019 estimates unless otherwise specified) from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database; Turkish Statistical Institute; Economist Intelligence Unit; and Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook.

Turkey's Strategic Orientation: The United States, Russia, and Others

Numerous points of tension have raised questions within the United States and Turkey about the two countries' alliance, as well as Turkey's commitment to NATO and Western orientation. For their part, Turkish leaders may bristle because they feel like Turkey is treated as a junior partner, and they have arguably sought greater foreign policy diversification through stronger relationships with more countries.1

A number of considerations drive the complicated dynamics behind Turkey's international relationships. Turkey's history as both a regional power and an object of great power aggression translates into wide popularity for nationalistic political actions and discourse.2 Moreover, Turkey's cooperative relationships with countries whose respective interests may conflict involve a balancing act. Threats from Syria and Iraq and the regional roles of the United States, Russia, and Iran further complicate Turkey's situation.

Concerns among Turkish leaders that U.S. policy might hinder Turkey's security, which date back at least to the 1991 Gulf War,3 have been fueled during this decade by the following developments:

- Close U.S. military cooperation against the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIS) with Syrian Kurdish forces linked to the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), a U.S.-designated terrorist organization that has waged an on-and-off insurgency against the Turkish government since the 1980s while using safe havens in both Syria and Iraq.

- Perceived U.S. support for or acquiescence to events during post-2011 turmoil in Egypt and Syria that undermined Sunni Islamist figures tied to Turkey.

- Many Western leaders' criticism of President Erdogan for ruling in an increasingly authoritarian manner. Erdogan's sensitivity to Western concerns was exacerbated by a 2016 coup attempt that Erdogan blames on Fethullah Gulen, a former Turkish imam who leads a worldwide socioreligious movement and lives in the United States.

Perhaps partly in response to Turkey's concerns that some U.S. policies might not serve its interests, Turkey has sought a more independent course. Despite Turkey's long history of discord with Russia, and some ongoing disagreements between the two countries on Syria, Turkey may be disposed to cooperate more with Russia in hopes of reducing threats that Turkey faces, influencing regional political outcomes, and decreasing Turkey's military and economic reliance on the West. After a low in Turkey-Russia relations in 2015-2016—brought about by the Turkish downing of a Russian plane near the Turkey-Syria border and Russia's temporary imposition of sanctions—Erdogan and Russian President Vladimir Putin have cultivated closer ties. Putin showed support for Erdogan during the 2016 coup attempt, and subsequently allowed Turkey to carry out military operations in northern Syria that helped roll back Kurdish territorial control and reduce refugee flows near Turkey's border.4

Turkey's more independent foreign policy also may be reflected in its efforts to establish military, political, and economic linkages with countries in its surrounding regions—sometimes explained by reference to shared Muslim identity or historical ties dating back to the Ottoman Empire. However, Turkey's efforts to increase its influence and offer itself as a "model" for other regional states appear to have been set back by a number of developments since 2011: (1) conflict and instability that engulfed the region and Turkey's own southern border, (2) Turkey's failed effort to help Muslim Brotherhood-aligned groups gain lasting power in Syria and North Africa, and (3) domestic polarization accompanied by government repression.5

Additionally, Turkey's regional ambitions have contributed to difficulties with some of its neighbors. Sunni Arab states like Saudi Arabia and Egypt regard Turkey suspiciously because of the Turkish government's Islamist sympathies and close relationship with Qatar.6 Turkey's rivalry with these Arab states is reflected by their support for opposing sides in Libya's civil war,7 as well as by maritime facilities that Turkey has or plans to have in Qatar, Somalia, Sudan, and northern Cyprus.8 Turkey maintains relations with Israel, but these previously close ties have become distant and—at times—contentious during Erdogan's time as prime minister and president. Turkey's dispute with the Republic of Cyprus over Eastern Mediterranean energy exploration has brought the Republic of Cyprus, Israel, and Greece closer together—a development supported by the United States9—and has led to Western criticism of Turkey and some specific European Union measures aimed at discouraging Turkish drilling near Cyprus.10 Turkey, for its part, has called on the Republic of Cyprus to agree to energy revenue sharing with Turkish Cypriots who are represented by a Turkey-supported de facto government in the northern one-third of the island.

U.S./NATO Cooperation with Turkey

Overview

Turkey's location near several global hotspots makes the continuing availability of its territory for the stationing and transport of arms, cargo, and personnel valuable for the United States and NATO. From Turkey's perspective, NATO's traditional value has been to mitigate its concerns about encroachment by neighbors. Turkey initially turned to the West largely as a reaction to aggressive post-World War II posturing by the Soviet Union. In addition to Incirlik Air Base near the southern Turkish city of Adana, other key U.S./NATO sites include an early warning missile defense radar in eastern Turkey and a NATO ground forces command in Izmir. Turkey also controls access to and from the Black Sea through its straits pursuant to the Montreux Convention of 1936.

Current tensions have fueled discussion from the U.S. perspective about the advisability of continued U.S./NATO use of Turkish bases. The Trump Administration reportedly reduced the U.S. military presence at Incirlik in 2018 while contemplating broader reductions in Turkey.11 There are historical precedents for such changes. On a number of occasions, the United States has withdrawn military assets from Turkey or Turkey has restricted U.S. use of its territory or airspace. These include the following:

- 1962—Cuban Missile Crisis. The United States withdrew its nuclear-tipped Jupiter missiles from Turkey as part of the secret deal to end this crisis with the Soviet Union.

- 1975—Cyprus. Turkey closed most U.S. defense and intelligence installations in Turkey during the U.S. arms embargo that Congress imposed in response to Turkey's military intervention in Cyprus.

- 2003—Iraq. A Turkish parliamentary vote did not allow the United States to open a second front from Turkey in the Iraq war.

Some of the plotters of an unsuccessful coup attempt in Turkey in July 2016 apparently used Incirlik air base, causing temporary disruptions of some U.S. military operations. The attempted coup and subsequent disruptions may have eroded some trust between the two countries, while also raising U.S. questions about Turkey's stability and the safety and utility of Turkish territory for U.S. and NATO assets. As a result of these questions and U.S.-Turkey tensions, some observers have advocated exploring alternative basing arrangements in the region.12

The cost to the United States of finding a replacement for Incirlik and other sites in Turkey would likely depend on a number of variables including the functionality and location of alternatives, where future U.S. military engagements may happen, and the cost of moving or expanding U.S. military operations elsewhere. While an August 2018 report cited a Department of Defense (DOD) spokesperson as saying that the United States is not leaving Incirlik,13 some reports suggest that expanded or potentially expanded U.S. military presences in Greece and Jordan might be connected with concerns about Turkey.14

An assessment of the costs and benefits to the United States of a U.S./NATO presence in Turkey, and of potential changes in U.S./NATO posture, revolves to a significant extent around three questions:

- To what extent does strengthening Turkey relative to other regional actors serve U.S. interests?

- To what extent does the United States rely on the use of Turkish territory or airspace to secure and protect U.S. interests?

- To what extent does Turkey rely on U.S./NATO support, both politically and functionally, for its security and regional influence?

S-400 Acquisition from Russia and Removal from F-35 Aircraft Program

U.S.-Turkey tensions over Turkey's ongoing acquisition of a Russian S-400 air defense system and the resulting U.S. removal of Turkey from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program could have broad implications for bilateral relations and defense cooperation. It also could impact Turkey's role in NATO.

In July 2019, Turkey reportedly began taking delivery of Russian S-400 components at Murted air base near Ankara, Turkey's capital.15 The first batch of missiles for the S-400 system is scheduled to arrive in Turkey in September 2019, and the head of Turkey's defense procurement agency has said that Turkey expects the system to be operational sometime this year.16 President Erdogan has said that the system will be fully deployed by April 2020.17

In response to the beginning of S-400 deliveries to Turkey, the Trump Administration announced on July 17 that it was removing Turkey from participation in the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program.18 Turkey had planned to purchase 100 U.S.-origin F-35s and has been one of eight original consortium partners in the development and industrial production of the aircraft.19 If Turkey does not receive the F-35, it might turn to other sources—possibly including Russia—to fill its capability need for next-generation aircraft and other major defense purchases.20

|

End of Turkish Involvement: Impact on the F-35 Program Because the F-35 program features multinational industrial inputs, unwinding Turkey's involvement could present financial and logistical challenges. Turkish companies have been involved in about 6%-7% of the supply chain—building displays, wiring, fuselage structures, and other parts—for F-35s provided to all countries.21 With some lead time to anticipate Turkey's possible removal from the program, the F-35 joint program office within DOD has identified alternative suppliers for the Turkish subsystems.22 According to Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen Lord, existing contracts with Turkish suppliers for over 900 parts would reportedly wind down by March 2020, and the United States "is spending between $500 million and $600 million in non-recurring engineering in order to shift the supply chain."23 According to an April 2019 statement from the joint program office's director, Vice Admiral Mathias Winter, "the evaluation of Turkey stopping would be between [a] 50- and 75-airplane impact over a two-year period."24 It is unclear whether the United States or the F-35 consortium could be liable for financial penalties beyond refunding Turkey's initial investment in the program, an estimated $1.5 billion.25 Additionally, the depot to service engines for European countries' F-35s was initially slated to be in Turkey. However, according to Under Secretary Lord, "There are two other European MRO&Us [maintenance, repair, overhaul and upgrade facilities] that can absorb the volume with no issue whatsoever."26 The CEO of Lockheed Martin, the primary contractor for the F-35, said in May 2019 that if Turkey did not purchase the 100 aircraft, the consortium would not have difficulty finding willing buyers for them. Two possible buyers include Japan and Poland.27 |

In explaining the U.S. decision to remove Turkey from the F-35 program, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen Lord said, "Turkey cannot field a Russian intelligence collection platform [within the S-400 system] in proximity to where the F-35 program makes, repairs and houses the F-35. Much of the F-35's strength lies in its stealth capabilities, so the ability to detect those capabilities would jeopardize the long-term security of the F-35 program."28 A security concern regarding the F-35 could compromise its global marketability and effectiveness.29 While some Russian radars in Syria may have already monitored Israeli-operated F-35s,30 intermittent passes at long ranges reportedly might not yield data on the aircraft as conclusive as the more voluminous data available if an S-400 in Turkey could routinely monitor F-35s.31 However, one U.S.-based analyst has said that U.S. concerns are "overblown" and that Russian tracking of F-35s in Turkey would not significantly differ from monitoring elsewhere.32

While Under Secretary Lord said that Turkey's S-400 purchase is inconsistent with its NATO commitments and will negatively affect interoperability, she also stated that Turkey "remains a close NATO ally and our military-to-military relationship remains strong."33

CAATSA Sanctions?

The Turkey-Russia S-400 transaction could trigger the imposition of U.S. sanctions under Section 231 of the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA, P.L. 115-44). It appears that President Trump is examining the question of sanctions but has not reached specific conclusions.34 On July 12, the Chairs and Ranking Members of the Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services Committees issued a joint statement urging the President "to fully implement sanctions as required by law" under CAATSA.35 In late July, President Trump reportedly asked a group of Republican Senators for flexibility on sanctions implementation regarding Turkey while pursuing a deal potentially allowing Turkey to remain in the F-35 program if it (1) agrees not to use the S-400 and (2) acquires a U.S. Patriot air defense system.36 Turkish officials maintain that the S-400 is a "done deal" and any purchase of Patriot would be in addition to the S-400.37 However, some analysts and former U.S. officials maintain that Turkey's S-400 acquisition may not be final, or that a verifiable arrangement that prevents S-400 data gathering on the F-35 could allow the two systems to coexist in Turkey.38

Senator Lindsey Graham reportedly advised Turkey's foreign minister in late July that if Turkey does not activate the S-400 system, it may not face U.S. sanctions.39 Shortly thereafter, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo seemed to reinforce this point in an interview,40 and the State Department spokesperson said that the CAATSA legislation does not mandate a timetable for sanctions.41

President Erdogan—amid a financial crisis in Turkey (see "Economic Concerns" below)—has appealed directly to President Trump to soften any penalties that Turkey might face.42 According to one media report, Erdogan has threatened to retaliate against any sanctions, including by withdrawing Turkey from NATO and kicking the United States out of Incirlik air base.43

Turkey's Rationale and Implications for NATO

In announcing its decision in December 2017 to acquire S-400s instead of U.S. or European alternatives, Turkey claimed that it turned to Russia because NATO allies rebuffed Turkish attempts to purchase an air defense system from them.44 Turkey also cited various practical reasons, including cost, technology sharing, and territorial defense coverage.45 However, one analysis asserted that the S-400 deal would not involve technology transfer, would not defend Turkey from ballistic missiles (because the system would not have access to NATO early-warning systems), and could weaken rather than strengthen Turkey's geopolitical position by increasing Turkish dependence on Russia.46 Although Turkish officials later said that the deal would include technology transfer,47 a Russian observer analyzing terms of the deal suggested that co-production—if it were to happen—probably would not involve meaningful technology transfer.48

For some observers, the S-400 issue raises the possibility that Russia could take advantage of U.S.-Turkey friction to undermine the NATO alliance.49 In April 2019, Vice President Mike Pence asked publicly whether Turkey wants "to remain a critical partner in the most successful military alliance in history" or "risk the security of that partnership."50 In 2013, Turkey reached a preliminary agreement to purchase a Chinese air and missile defense system, but later (in 2015) withdrew from the deal, perhaps partly due to concerns voiced within NATO, as well as China's reported reluctance to share technology.51

A number of analysts have sought to explain possible political motivation for Turkey's actions on the S-400 deal by citing Turkey's willingness to act more independently in the context of U.S.-Turkey tensions and other regional trends (see "Turkey's Strategic Orientation: The United States, Russia, and Others" above). Some have raised the possibility that Turkey may seek to defend against U.S.-origin aircraft of the type used by elements within the Turkish military during the 2016 coup attempt.52 Other contributing factors to the S-400 decision may include nationalistic strains within Turkish domestic politics,53 as well as Turkey's desires for more diversified sources of arms procurement due partly to its experience from the 1970s U.S. arms embargo over Cyprus.54 According to one analyst, "the Turkish government seems determined to remain equidistant between Russia and [the] US in the near future, despite the fact that Turkey's economy and institutions are anchored in its century-old Western orientation."55 The same analyst asserts that U.S. policymakers face a dilemma in finding a way to discourage Turkey-Russia defense cooperation without either harming Turkey's economic stability or pushing the country closer to Russia.56

Additional Relevant Legislation

In 2018, Congress enacted legislation that subjected Turkey's possible F-35 purchase to greater scrutiny. Under Section 1282 of the FY2019 John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 115-232), DOD submitted a report to Congress in November 2018 on a number of issues affecting U.S.-Turkey defense cooperation, including the S-400 and F-35.57

Much of the report was classified, but an unclassified summary said that the U.S. government has told Turkey that purchasing the S-400 would have "unavoidable negative consequences for U.S.-Turkey bilateral relations, as well as Turkey's role in NATO."58 The listed consequences included potential CAATSA sanctions, as well as risk to Turkish participation in the F-35 program and to broader bilateral defense industrial cooperation.59

Congress has mandated that no U.S. funds can be used to transfer F-35s to Turkish territory until DOD submits a report—required no later than November 1, 2019—updating the November 2018 report mentioned above. Pursuant to Section 7046(d)(2) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), the update is to include a "detailed description of plans for the imposition of sanctions, if appropriate," for an S-400 purchase. In June 2019, the House passed H.Res. 372, a nonbinding resolution calling for consequences if Turkey does not cancel the S-400 deal.

In 2019, five separate provisions have either passed a house of Congress or been reported by a committee (H.R. 2500, S. 1790, S. 1102, two in H.R. 1740) that would each prevent the use of funds to transfer F-35s to Turkey. Most of the provisions (other than the defense appropriations provision in H.R. 1740) are subject to waiver if the executive branch can certify in some manner that Turkey does not plan to take delivery of or keep the S-400.

Syria

Turkey's involvement in Syria's conflict since 2011, which includes a post-2016 military presence in parts of the country, has been complicated and costly. During that time, Turkey's priorities in Syria appear to have evolved. While Turkey still officially calls for Syrian President Bashar al Asad to leave power, it has engaged in a mix of coordination and competition with Russia and Iran (both Asad supporters) on some matters since intervening militarily in Syria starting in August 2016. Turkey may want to protect its borders, project influence, promote commerce, and counter other actors' regional ambitions.

Turkey's chief objective has been to thwart the PKK-linked Syrian Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) from establishing an autonomous area along Syria's northern border with Turkey. Turkey considers the YPG and its political counterpart, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), to be the top threat to Turkish security, given the boost the YPG/PYD's military and political success could provide to the PKK's insurgency within Turkey.60 The YPG plays a leading role in the umbrella group known as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which also includes Arabs and other non-Kurdish elements.

Since 2014, the SDF has been the main U.S. ground force partner against the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIS). Even though Turkey is also a part of the anti-IS coalition, U.S. operations in support of the SDF—largely based from Turkish territory—have fueled U.S.-Turkey tension because of Turkey's view of the YPG as a threat.61 As part of SDF operations to expel the Islamic State from its main Syrian redoubt in Raqqah in 2017, the U.S. government pursued a policy of arming the YPG directly while preventing the use of such arms against Turkey,62 and then-Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis announced an end to the direct arming of the YPG near the end of the year.63 Following the Raqqah operation, U.S. officials contrasted their long-standing alliance with Turkey with their current but temporary cooperation with the YPG.64

After Turkey moved against IS-held territory in northern Syria (Operation Euphrates Shield, August 2016-March 2017) as a way to prevent the YPG from consolidating its rule across much of the border area between the two countries, Turkey launched an offensive directly against the YPG in Afrin district in January 2018. In Afrin and the other areas Turkey has occupied since 2016 with the help of allied Syrian opposition militias, Turkey has organized local councils and invested in infrastructure.65 Questions persist about how deeply Turkey will influence future governance in these areas.

President Trump announced in December 2018 that the United States would withdraw the approximately 2,000 U.S. troops stationed in Syria, but subsequent Administration statements indicate that at least several hundred U.S. troops remain and will do so indefinitely. The future of the U.S. military presence in Syria could have important implications for Turkey and the YPG. Turkey has refused to guarantee the YPG's safety, with Erdogan insisting that Turkey should have a free hand with the YPG and other groups it considers to be terrorists.66 Various analyses surmise that a U.S. troop withdrawal could lead the YPG toward an accommodation with Russia and the Syrian government.67

In January, amid reports that the U.S. military had begun preparing for withdrawal,68 President Trump tweeted that he would "devastate Turkey economically" if it hit the Kurds, and at the same time proposed the creation of a 20-mile-deep "safe zone" on the Syria side of the border.69 U.S. officials favor having a Western coalition patrol any kind of buffer zone inside the Syrian border, with some U.S. support, while Turkey wants its forces and Syrian rebel partners to take that role.70 In August 2019, the United States and Turkey agreed to set up a joint operations center to manage a safe zone, though questions remain about the zone's geographical scope, who will patrol it, its effect on the SDF/YPG, and whether Syrian refugees in Turkey will be able to resettle there.71 Turkish military action could cause the SDF to shift its forces, possibly undermining its ongoing efforts at guarding tens of thousands of IS prisoners and their families.72

|

Syrian Refugees in Turkey In addition to its ongoing military activities in Syria, Turkey hosts about 3.6 million registered Syrian refugees—more than any other country. Turkish officials estimate that they have spent more than $37 billion on refugee assistance.73 According to these official estimates, the Syrian refugee population in Turkey increased in 2018 even though around 291,000 refugees returned to Syria.74 With the large-scale return of refugees to Syria uncertain, Turkey has focused on how to manage their presence in Turkish society by addressing their legal status, basic needs, employment, education, and impact on local communities.75 Problems in the Turkish economy may be fueling some negative views of the refugees among Turkish citizens—especially in areas where refugees are concentrated—and some violence between the two groups has been reported.76 |

How U.S.-Turkey coordination plays out in northeastern Syria could influence Turkey's presence in western Syria, particularly in key contested areas like Idlib province, where Russian and Syrian government forces operate in proximity to Turkish forces as part of a "de-escalation zone" agreement reached between Turkey and Russia in September 2018. Turkey-backed forces stationed at points around the province appear to have failed to prevent territorial gains by Al Qaeda-linked Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS) jihadists who also oppose the Syrian government.

Domestic Turkish Developments

Political Developments Under Erdogan's Rule

President Erdogan has ruled Turkey since becoming prime minister in 2003. After Erdogan became president in August 2014 via Turkey's first-ever popular presidential election, he claimed a mandate for increasing his power and pursuing a "presidential system" of governance. Analyses of Erdogan sometimes characterize him as one or more of the following: a pragmatic populist, a protector of the vulnerable, a budding authoritarian, an indispensable figure, and an Islamic ideologue.77 Erdogan is a polarizing figure, with about half the country supporting his rule, and half the country against it. U.S. and European Union officials have expressed a number of concerns about rule of law and civil liberties in Turkey,78 including the government's influence on media and Turkey's reported status as the country with the most journalists in prison.79

While there may be some similarities between Turkey under Erdogan and countries like Russia, Iran, or China, some factors distinguish Turkey from them. For example, unlike Russia or Iran, Turkey's economy cannot rely on significant rents from natural resources if foreign sources of revenue or investment dry up. Unlike Russia and China, Turkey does not have nuclear weapons under its command and control. Additionally, unlike all three others, Turkey's economic, political, and national security institutions and traditions have been closely connected with those of the West for decades.

Erdogan's consolidation of power has continued amid domestic and international concerns about growing authoritarianism in Turkey. He outlasted the July 2016 coup attempt, after which Turkey's government detained tens of thousands and took over or closed various businesses, schools, and media outlets.80 Despite laying the primary blame for the attempted coup on Fethullah Gulen and his movement,81 the government's crackdown apparently targeted many Turkish citizens outside of the Gulen movement.82 Over 150 people, mostly from the military, were sentenced to life in prison in June 2019 for various charges related to the coup attempt.83 Additionally, as part of the post-coup crackdown, Turkey has detained a number of Turks employed at U.S. diplomatic facilities in Turkey.84

Erdogan scored key victories in an April 2017 constitutional referendum and June 2018 presidential and parliamentary elections—emerging with the expanded presidential powers he had sought. Some allegations of voter fraud and manipulation surfaced in both elections.85 Erdogan's Islamist-leaning Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi, or AKP) maintained the largest share of votes in March 2019 local elections, but lost some key municipalities to opposition candidates, mostly from the secular-leaning Republican People's Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, or CHP). Disputes over the Istanbul mayoral election led to a re-run of that race in June 2019 that yielded a significant victory for the CHP candidate. Despite Istanbul's symbolic importance, it remains unclear to what extent, if at all, losing control of Turkey's largest city poses a real threat to Erdogan's rule.86 A combination of factors, including Erdogan's governing style and the ongoing economic downturn, appears to be fueling efforts by former top AKP figures such as former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu and former Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan to consider political involvement outside the party.87

Economic Concerns

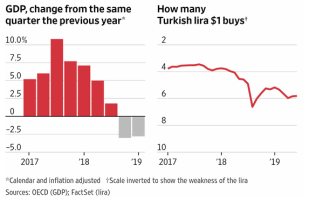

The Turkish economy slowed considerably during 2018 (see Figure 2 below), entering a recession in the second half of the year with negative consequences both for consumer demand and for companies seeking or repaying loans in global markets.88 Forecasts for 2019 generally remain negative.89 During 2018, the Turkish lira depreciated close to 30% against the dollar in an environment featuring a globally stronger dollar, rule of law concerns and political uncertainty, and significant corporate debt.

|

|

Source: Wall Street Journal, June 2019. |

Some observers speculate that Turkey may need to turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a financial assistance package.90 This would be a sensitive challenge for President Erdogan because his political success story is closely connected with helping Turkey become independent from its most recent IMF intervention in the early 2000s.91 In January 2019, Turkey's parliament voted to grant Erdogan broader emergency powers in case of a financial crisis.92

The government appears to be trying to stimulate growth via familiar measures to boost consumer demand. A former Turkish economic official claimed in January that by offloading the "debt crisis of the real sector" onto the banking sector, the government has exacerbated the crisis and that a "harsh belt-tightening policy" with or without the IMF is thus inevitable.93 In July, Erdogan fired the central bank's governor for his unwillingness to loosen monetary policy, and shortly thereafter the new governor cut the key interest rate by 4.25%.94 He may be inclined to make additional cuts.95 However, a number of analysts assess that consumer and investor confidence in Turkey's economy could remain low without resolution of the debt loads carried by Turkish banks and private companies.96 Greater political turmoil in Turkey, or increased foreign policy tensions (including potential U.S. sanctions related to Turkey's S-400 acquisition), could spur further economic decline.