Introduction

Since 2002, Canada has been the United States' top agricultural export market. Mexico was the second-largest export market until 2010, when China displaced Mexico as the second-leading market with Mexico becoming the third-largest U.S. agricultural export market. In FY2018, U.S. agricultural exports totaled $143 billion, of which Canada and Mexico jointly accounted for about 27%. USDA's Economic Research Service estimates that in 2017 each dollar of U.S. agricultural exports stimulated an additional $1.30 in business activity in the United States. That same year, U.S. agricultural exports generated an estimated 1,161,000 full-time civilian jobs, including 795,000 jobs outside the farm sector.1 U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico are an important part of the U.S. economy, and the growth of these markets is partly the result of the North American market liberalization under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).2

On September 30, 2018, the Trump Administration announced an agreement with Canada and Mexico for a U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) that would possibly replace NAFTA. NAFTA entered into force on January 1, 1994, following the passage of the implementing legislation by Congress (P.L. 103-182).3 NAFTA was structured as three separate bilateral agreements: one between Canada and the United States, a second between Mexico and the United States, and a third between Canada and Mexico.4

Provisions of the Canada-U.S. Trade Agreement (CUSTA), which went into effect on January 1, 1989, continued to apply under NAFTA (see Table 1). CUSTA opened up a 10-year period for tariff elimination and agricultural market integration between the two countries. The agricultural provisions agreed upon for CUSTA remained in force as provisions of the new NAFTA agreement. While tariffs were phased out for almost all agricultural products, NAFTA (in accordance with the original CUSTA provisions) exempted certain products from market liberalization. These exemptions included U.S. imports from Canada of dairy products, peanuts, peanut butter, cotton, sugar, and sugar-containing products and Canadian imports from the United States of dairy products, poultry, eggs, and margarine. Canada liberalized its agricultural sector under NAFTA, but liberalization did not include its dairy, poultry, and egg product sectors, which continued to be governed by domestic supply management policies and are protected from imports by high over-quota tariffs.

Quotas that once governed bilateral trade in these commodities were redefined, under NAFTA, as tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) to comply with the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture (URAA), which took effect on January 1, 1995.5 A TRQ is a quota for a volume of imports at a favorable tariff rate, which was set at zero under NAFTA. Imports beyond the quota volume face higher over-quota tariff rates.

|

January 1989 |

Canada-United States Trade Agreement implemented. |

|

January 1994 |

NAFTA enters force, tariffs eliminated for many products, including: |

|

U.S. tariffs on Mexican corn, sorghum, barley, soymeal, pears, peaches, oranges, fresh strawberries, beef, pork, poultry, most tree nuts, and carrots; and |

|

|

Mexican tariffs on U.S. sorghum, fresh strawberries, oranges, other citrus, carrots, and most tree nuts. |

|

|

January 1998 |

Completion of 10-year transition period between Canada and the United States. |

|

Remaining Canadian tariffs on U.S. products eliminated, except for exempted products such as dairy, poultry, and eggs. |

|

|

Remaining U.S. tariffs on Canadian products removed, except for dairy products, peanuts, peanut butter, cotton, sugar, and sugar-containing products. |

|

|

U.S. tariffs eliminated on Mexican nondurum wheat, soy oil, cotton, and oranges. |

|

|

Among others, Mexican tariffs eliminated on imports of U.S. pears, plums, apricots, and cotton. |

|

|

January 2003 |

Completion of nine-year transition period under NAFTA between Mexico and the United States. |

|

Among others, U.S. tariffs eliminated on imports of Mexican durum wheat, rice, dairy, winter vegetables, frozen strawberries, and fresh tomatoes. |

|

|

Among others, Mexican tariffs eliminated on imports of U.S. wheat, barley, soybean meal and soybean oil, rice, dairy products, poultry, hogs, pork, cotton, tobacco, peaches, apples, oranges, frozen strawberries, and fresh tomatoes. |

|

|

January 2008 |

Completion of 14-year transition period under NAFTA between Mexico and the United States. In 2008, the remaining few tariffs were removed. |

|

U.S. tariffs eliminated on imports of Mexican frozen concentrated orange juice, winter vegetables, sugar, and melons. |

|

|

Mexican tariffs eliminated on imports of U.S. corn, sugar, dried beans, milk powder, high fructose corn syrup, and chicken leg quarters. |

|

|

May 2017 |

Trump Administration sends a 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to renegotiate and modernize NAFTA. |

|

August 2017 |

Renegotiation talks begin. |

|

September 30, 2018 |

Trump Administration sends a 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to enter into an agreement with Mexico and Canada to modify and modernize NAFTA. |

|

November 30, 2018 |

President Trump and presidents of Canada and Mexico sign proposed USMCA. |

|

April 2019 |

U.S. International Trade Commission report assessing potential economic impacts of USMCA submission to the President and Congress expected. |

Source: For NAFTA, S. Zahniser and J. Link, Effects of North American Free Trade Agreement on Agriculture and the Rural Economy, Economic Research Service, WRS-02-1, July 2002; H. Brunke and D. A. Sumner, "Role of NAFTA in California Agriculture: A Brief Review," University of California, AIC Issues Brief# 21, February 2003; S. Zahniser and Z. Crago, NAFTA at 15: Building on Free Trade, USDA Report WRS-09-03, March 2009; and CRS Report R44981, NAFTA Renegotiation and the Proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), by M. Angeles Villarreal and Ian F. Fergusson.

The United States and Mexico agreement under NAFTA did not exclude any agricultural products from trade liberalization. Numerous restrictions on bilateral agricultural trade were eliminated immediately upon NAFTA's implementation, while others were phased out over a 14-year period. Remaining trade restrictions on the last handful of agricultural commodities (such as U.S. exports to Mexico of corn, dry edible beans, and nonfat dry milk and Mexican exports to the United States of sugar, cucumbers, orange juice, and sprouting broccoli) were removed upon the completion of the transition period in 2008.6 Under NAFTA, Mexico eliminated all the tariffs and quotas that formerly governed agricultural imports from the United States.

In addition to directly improving market access, NAFTA set guidance and standards on other policies and regulations that facilitated the integration of the North American agricultural market. For example, NAFTA included provisions for rules of origin, intellectual property rights, foreign investment, and dispute resolution. NAFTA's sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) provisions made a significant contribution toward the expansion of agricultural trade by harmonizing regulations and facilitating trade.7 Because NAFTA entered into force before URAA, NAFTA's SPS agreement is considered to have provided the blueprint for URAA's SPS agreement.

Regarding trade in agricultural products, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USITC) asserts that USMCA would build upon NAFTA to make "important improvements in the agreement to enable food and agriculture to trade more fairly, and to expand exports of American agricultural products."8

For USMCA to enter into force, Congress would need to ratify the agreement. It must also be ratified by Canada and Mexico. The timeline for congressional approval of USMCA would likely occur under the Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) timeline established under the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-26).9 At various times, President Trump has stated that he intends to withdraw from NAFTA.10 Some observers have suggested that delays in congressional action on USMCA could make it harder for Canada to consider USMCA approval this year because of upcoming parliamentary elections in October 2019.11

Provisions of USMCA

USMCA seeks to expand upon the agricultural provisions of NAFTA by further reducing market access barriers and strengthening provisions to facilitate trade in North America. An important change in USMCA compared to NAFTA is that the United States agreement with Canada would expand TRQs for imports of U.S. agricultural products into Canada. Other important changes from NAFTA include the agreement between the three countries—Canada, Mexico, and the United States—to further harmonize trade in products of agricultural biotechnology and apply the same health, safety, and marketing standards to agricultural and food imports from USMCA partners as for domestic products.

Expansion of Market Access Provisions

As agreed upon by the leaders of the United States, Canada, and Mexico, all food and agricultural products that have zero tariffs under NAFTA would remain at zero under USMCA. Under USMCA, agricultural products exempted from tariff elimination under the agreement signed between the United States and Canada would be phased out for further market liberalization. Canada currently employs a supply management regime that includes TRQs on imports of dairy and poultry under its NAFTA and World Trade Organization (WTO) market access commitments. Under NAFTA, U.S. dairy has access into the Canadian market under Canada's WTO commitment provisions. For poultry, NAFTA TRQs were established in accordance with the original CUSTA provisions as a percentage of Canada's domestic production.12 When Canada joined the WTO in 1995, it committed to provide poultry market access at the level that is the greater of its commitment under the WTO or under NAFTA.13 For chicken meat, the NAFTA TRQ, set at 7.5% of the previous year's domestic production, is higher than the WTO TRQ set at 39,844 metric tons.14 Canada's chicken meat NAFTA TRQ was 90,100 metric tons in 2018, and the estimate is 95,000 metric tons for 2019.15

Both the poultry and dairy TRQs under NAFTA are global rather than specific to U.S. imports. The WTO dairy TRQs often have specific allocations for individual countries. For example, the bulk of Canada's WTO cheese quota is allocated to the European Union (EU), and the entire WTO powdered buttermilk TRQ is allocated to New Zealand.16 Overall, Canada's TRQs appear to have restricted imports of dairy, poultry, and egg products, as the imported volumes for these products have regularly equaled or exceeded their set quota limits.17

Under USMCA, Canada agreed to increase market access specifically to U.S. exporters of dairy products via new TRQs that are separate from Canada's existing WTO commitments. These additional TRQs apply only to the United States. For chicken meat and eggs, the USMCA replaces the NAFTA commitment with U.S.-specific TRQs. For turkey and broiler hatching eggs and chicks, Canada's NAFTA commitment would be replaced with a minimum access commitment under USMCA, which is not specific to U.S. imports but applies to imports from all origins. While USMCA would expand TRQs for U.S. exports, U.S. over-quota exports would still face the steep tariffs that currently exist under Canada's WTO commitment.18

The United States, in turn, agreed to improve access to Canadian dairy products, sugar, peanuts, and cotton. The United States would increase TRQs for Canadian dairy, sugar, and sweetened products. Tariffs on cotton and peanut imports into the United States from Canada would be phased out and eliminated five years after the agreement would take effect.

As for U.S.-Mexico trade in agricultural products, under NAFTA, Mexico eliminated all the tariffs and quotas that formerly governed agricultural imports from the United States, and the proposed USMCA provides for no further market access changes for imports by Mexico of U.S. agricultural products.

The proposed changes in the market access regime for U.S. agricultural exports to Canada under USMCA are summarized in Table 2. Canada's import restrictions on U.S. dairy products was a high-profile issue for the United States in the USMCA negotiations, so it is noteworthy that under USMCA, Canada agreed to reduce certain barriers to U.S. dairy exports, a key demand of U.S. dairy groups. For one, Canada would make changes to its milk pricing system that sets low prices for Canadian skim milk solids, which is believed to have undercut U.S. exports. Six months after USMCA goes into effect, Canada would eliminate its Class 7 milk price (which includes skim milk solids and is designated as Class 6 in Ontario) and would set its price for skim milk solids based on a formula that takes into account the U.S. nonfat dry milk price. In the future, the United States and Canada would notify each other if either introduces a new milk class price or changes an existing price for a class of milk products.

Under USMCA, Canada would maintain its dairy supply management system, but the TRQs would be increased each year for U.S. exports of milk, cheese, cream, skim milk powder, condensed milk, yogurt, and several other dairy categories. While existing in-quota tariffs for U.S. dairy exports to Canada are mostly zero, the over-quota rates can be as high as 200%-300%.19 USMCA includes provisions on transparency for the implementation of TRQs, such as providing advance notice of changes to the quotas and making public the details of quota utilization rates so that exporters could monitor the extent to which the quotas are filled.

While WTO TRQs are available to U.S. dairy product exporters under the current NAFTA provisions, the new TRQs proposed by Canada under USMCA would expand the access that U.S. dairy products would have into Canada. Large portions of Canada's WTO TRQs are allocated to other countries, such as cheese to the EU and powdered buttermilk to New Zealand. Thus, USMCA TRQs would open additional market opportunities for U.S. dairy exports to Canada. For example, the 64,500 metric ton fluid milk TRQ currently provided under NAFTA is available only for cross-border shoppers, but USMCA would allow up to 85% of the proposed new fluid milk TRQ, which would reach 50,000 metric tons by year 6, to U.S. commercial dairy processors. In response to another concern raised by the U.S. dairy industry, Canada agreed to cap its global exports of skim milk powder and milk protein concentrates and to provide information regarding these volumes to the United States. USMCA includes a requirement that the United States and Canada meet five years after the implementation of the agreement—and every two years after that—to determine whether to modify the dairy provisions of the agreement.

|

Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) |

Tariff Rate, % |

|

|

NAFTA commitments continue: Tariffs eliminated for almost all agricultural products under NAFTA |

0 |

|

|

NAFTA liberalization exemption: Dairy and poultry imports into Canada |

TRQs opened under WTO commitments |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota tariffs |

|

Dairy, U.S.-specific TRQs, in addition to TRQs under WTO, proposed by Canada |

||

|

Fluid milk TRQ begins at 8,333 MT and increases by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6 |

50,000 MT by year 6, 56,905 MT by year 19 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

Skim milk powder TRQ begins at 1,250 MT and increases by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6 |

7,500 MT by year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

Cheese TRQ begins at 2,084 MT and increases by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6 |

12,500 MT by year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

Cream TRQ begins at 1,750 MT and increases by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6 |

10,500 MT by year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

Whey TRQ begins at 689 MT and increases by 1% each year after year 6, until year 10 |

4, 135 MT by year 6 |

0 after year 10 |

|

Other dairy products (butter and cream powder, concentrated and condensed milk, yogurt and buttermilk, powdered buttermilk, ice cream, other dairy and margarine) begins at 2,561 MT and increases by 1% each year for 13 years after year 6 |

15,365 MT by year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over quota >200% Margarine, 0 after year 5 |

|

Poultry Products, New TRQs proposed by Canada |

||

|

Chicken meat, to increase by 1% each year for 10 years after year 6 |

47,000 MT in year one, reaching 57,000 MT by year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

Turkey meat, TRQ increase restricted to ≤ 1,000 MT after |

≥ 3.5% of Canada's previous year's domestic production |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >200% |

|

Eggs and products (eggs and egg-equivalent), to increase by 1% for 10 years after year 6 |

1.67 million dozen in year one, reaching 10 million dozen in year 6 |

0 in-quota; WTO MFN over-quota >163% |

|

Broiler hatching eggs and chick products |

≥ 21.1% of Canada's domestic production for that year |

0 in-quota, >200% over quota |

Source: Agreement between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada Text, Signed November 30, 2018; Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement, https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/assets/pdfs/agreements-accords/cusfta-e.pdf; USDA GAIN Report CA0125, 2000, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gainfiles/200008/30677853.pdf. Poultry over-quota tariff rates are as stated under Canada's WTO tariff schedule, WT/TPR/S/112 - WTO Documents Online.

Notes: The TRQs for turkey meat and for broiler hatching eggs and chicks are USMCA minimum global commitment level of anticipated current year's production or the WTO commitment volume, whichever is greater. MT denotes metric tons.

Under USMCA, Canada has proposed to replace its NAFTA commitments for poultry and eggs with new TRQs. Under USMCA, the duty-free quota for chicken meat would start at 47,000 metric tons on the agreement's entry into force and would expand to 57,000 metric tons in year six. It would then continue to increase by 1% per year for the next 10 years (Table 2). The United States would also have access to Canada's WTO chicken quota available to imports from all origins of 39,844 metric tons.20

Under USMCA, Canada's TRQ for imports of U.S. eggs would be phased in over six equal installments, reaching 10 million dozen by year six and then increasing by 1% per year for the next 10 years. The annual TRQ for turkey and broiler hatching eggs and chicks would be set by formulas based on Canadian production (see Table 2). The TRQs for turkey and broiler-hatching eggs and chicks are USMCA minimum global access commitments based on the greater of Canada's anticipated current year production or its WTO commitment volume.

Improved Agricultural Trading Regime

Under USMCA, several key provisions would further expand the Canadian and Mexican market access to U.S. agricultural producers.21 With the exception of the wheat grading provision between Canada and Mexico, the following provisions, which aim to improve the trading regime, apply to all three countries:

- Wheat. Canada and the United States have agreed that they shall accord "treatment no less favorable than it accords to like wheat of domestic origin with respect to the assignment of quality grades."22 Currently, U.S. wheat exports to Canada are graded as feed wheat, which generally commands a lower price. Under USMCA, U.S. wheat exports to Canada would receive the same treatment and price as equivalent Canadian wheat if there is a predetermination that the U.S. wheat variety is similar to a Canadian variety. Canada maintains a list of registered wheat varieties, but the United States does not have a similar list. U.S. wheat exporters would first need to have U.S. varieties approved and registered in Canada before they would be able to benefit from this equivalency provision. According to some stakeholders, this process can be onerous and take several years.23

- Cotton. The addition of a specific textile and apparel chapter to the proposed USMCA may support U.S. cotton production. The chapter promotes greater use of North American–origin textile products such as sewing thread, pocketing, narrow elastics, and coated fabrics for certain end items.

- Spirits, wine, beer, and other alcoholic beverages. Each country must treat the distribution of another USMCA country's spirits, wine, beer, and other alcoholic beverages as it would its own products. The agreement also establishes new rules governing the listing requirements for a product to be sold in a given country with specific limits on cost markups of alcoholic beverages imported from USMCA countries.

- SPS provisions. USMCA's SPS chapter calls for greater transparency in SPS rules and regulatory alignment among the three countries. It would establish a new mechanism for technical consultations to resolve SPS issues. SPS provisions provide for increasing transparency in the development and implementation of SPS measures; advancing science-based decisionmaking; improving processes for certification, regionalization and equivalency determinations; conducting systems-based audits; improving transparency for import checks; and promoting greater cooperation to enhance compatibility of regulatory measures.

- Geographical indications (GIs). The United States, Canada, and Mexico agreed to provide procedural safeguards for recognition of new GIs, which are place names used to identify products that come from certain regions or locations. USMCA would protect the GIs for food products that Canada and Mexico have already agreed to in trade negotiations with the EU and would lay out transparency and notification requirements for any new GIs that a country proposes to recognize. The agreement also details a process for determining whether a food name is common or is eligible to be protected as a GI.

- In a side letter accompanying the agreement, Mexico confirmed a list of 33 terms for cheese that would remain available as common names for U.S. cheese producers to use in exporting cheeses to Mexico. The list includes some terms that are protected as GIs by the EU, such as Edam, Gouda, and Brie.

- USMCA provisions would protect certain U.S., Canadian, and Mexican spirits as distinctive products. Under the proposed agreement, products labeled as Bourbon Whiskey and Tennessee Whiskey must originate in the United States. Similar protections would exist for Canadian Whiskey, while Tequila and Mezcal would have to be produced in Mexico. In a side letter accompanying the agreement, the United States and Mexico further agree to protect American Rye Whiskey, Charanda, Sotol, and Bacanora.

- Protections for proprietary food formulas. USMCA signatories agree to protect the confidentiality of proprietary formula information in the same manner for domestic and imported products. The agreement would also limit such information requirements to what is necessary to achieve legitimate objectives.

- Biotechnology. The agricultural chapter of USMCA lays out provisions for trade in products created using agricultural biotechnology, an issue that was not covered under NAFTA. USMCA provisions for biotechnology cover crops produced with all biotechnology methods, including recombinant DNA and gene editing. USMCA would establish a Working Group for Cooperation on Agricultural Biotechnology to facilitate information exchange on policy and trade-related matters associated with the products of agricultural biotechnology. The agreement also outlines procedures to improve transparency in approving and bringing to market agricultural biotech products. It further outlines procedures for handling shipments containing a low-level presence of unapproved products.

While USMCA addresses a number of issues that restrict U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico and Canada, it does not include all of the changes sought by U.S. agricultural groups. For instance, the agreement does not include changes to trade remedy laws to address imports of seasonal produce as requested by Southeastern U.S. produce growers. It also does not address nontariff barriers to market access for U.S. fresh potatoes in Mexico24 and Canada. Canada's Standard Container Law (part of the Fresh Fruits and Vegetable Regulations of the Canadian Agricultural Products Act) prohibits the importation of U.S. fresh potatoes to Canada in bulk quantities (over 50 kilograms).25 Finally, the agreement does not address the removal of retaliatory tariffs on U.S. agricultural exports imposed by Canada and Mexico in response to U.S. Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum. Some U.S. agriculture stakeholders have expressed concern that the potential benefits of implementing USMCA would be outweighed by the retaliatory tariffs imposed on U.S. agricultural exports by Canada and Mexico.26

U.S. Agricultural Trade with Canada and Mexico

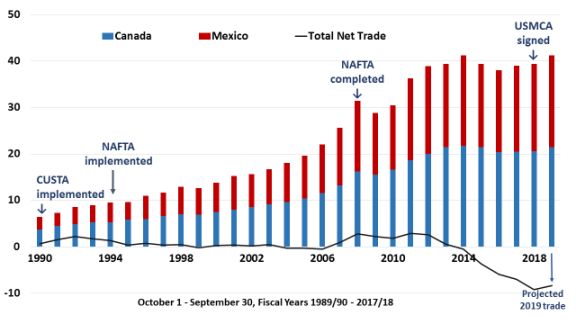

Since 2002, Canada and Mexico have been two of the top three export markets for U.S. agricultural products (competing with Japan until 2009, when China moved into the top three). In recent years, the two countries have jointly accounted for about 40% of the total value of U.S. agricultural exports. Intraregional trade in North America has increased substantially since the implementation of CUSTA and NAFTA and in the wake of Mexico's market-oriented agricultural reforms, which started in the 1980s (Figure 1). The value of total U.S. agricultural product exports to Canada and Mexico rose from under $7 billion at the start of CUSTA in FY1990 to almost $10 billion at the start of NAFTA in FY1994 and peaked at $41 billion in FY2014. The lower level of exports since FY2014 is partly due to a drought-related decline in livestock production in parts of the United States; increased Canadian production of corn, rapeseed, and soybeans; increased use of U.S. corn as ethanol feedstock; growth in U.S. export markets outside of NAFTA; and increased competition from outside of NAFTA.27 Since mid-2018, U.S. exports of certain products have been adversely affected by the imposition of retaliatory tariffs by Canada and Mexico in response to the Trump Administration's application of a 25% tariff on all U.S. steel imports and a 10% tariff on all U.S. aluminum imports under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962.28

Similar to the growth in U.S. agricultural exports, U.S. imports of agriculture and related products from Canada and Mexico grew from about $6 billion in FY1990 to $8 billion in FY1994, and U.S. agricultural exports continued to increase after NAFTA came into force on January 1, 1994, reaching $48 billion in FY2018. For FY2019, USDA projects that total U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico will to decline to $41.2 billion, while U.S. imports from those countries are projected at $49.6 billion.29

U.S. Agricultural Exports to Canada and Mexico

Table 3 presents U.S. agricultural exports to Canada for selected years since 1990, the year after the implementation of CUSTA. The other years in the table include 1995 (the year following the start of NAFTA), 2009 (the year following the full implementation of NAFTA), and the last three years with complete fiscal year data: 2016, 2017, and 2018.

U.S. agricultural exports to Canada averaged over $20 billion between FY2016 and FY2018 period (Table 3) and accounted for 14% of the total value of U.S. agriculture exports in FY2018. While the overall value of U.S. agricultural exports to Canada has increased under NAFTA, U.S. exports of consumer-ready food products registered the greatest increase, accounting for almost 80% of the value of all U.S. agricultural exports to Canada in FY2018. Canada accounted for 24% of the value of total U.S. consumer-ready food product exports to all destinations in FY2018.

In FY2018, Canada accounted for 72% of the total value of U.S. fresh vegetable exports to all destinations, 54% of nonalcoholic beverage exports to all destinations, 51% of snack food exports to all destinations, 33% of total exports of fresh fruit, 33% of live animal exports, and 26% of total U.S. wine and beer exports to all destinations. Canada is also an important market for bulk agricultural commodities, and Canadian imports of U.S. corn, soybeans, rice, pulses, and wheat have increased since the implementation of NAFTA.

Table 3. Major U.S. Agriculture Exports to Canada

Millions U.S. dollars, selected October 1-September 30 fiscal years

|

1990 |

1995 |

2009 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

% Share of Total U.S. Ag Exports, FY2018a |

|

|

Total agriculture |

3,730 |

5,895 |

15,541 |

20,392 |

20,442 |

20,569 |

14 |

|

Total consumer oriented |

2,565 |

4,361 |

11,835 |

16,374 |

16,291 |

16,127 |

24 |

|

Prepared food |

126 |

487 |

1,355 |

1,904 |

1,891 |

1,876 |

31 |

|

Fresh vegetables |

463 |

755 |

1,472 |

1,868 |

1,850 |

1,834 |

72 |

|

Fresh fruit |

520 |

578 |

1,353 |

1,639 |

1,594 |

1,555 |

33 |

|

Snack foods |

147 |

337 |

1,042 |

1,333 |

1,346 |

1,360 |

51 |

|

Tree nuts |

59 |

82 |

256 |

596 |

639 |

674 |

8 |

|

Pork and pork products |

26 |

49 |

521 |

782 |

797 |

763 |

12 |

|

Dairy products |

29 |

67 |

329 |

589 |

672 |

627 |

11 |

|

Beef and beef products |

270 |

379 |

629 |

765 |

789 |

768 |

9 |

|

Poultry meat and products |

111 |

165 |

433 |

527 |

468 |

428 |

10 |

|

Eggs and products |

26 |

32 |

70 |

119 |

92 |

120 |

20 |

|

Wine and beer |

47 |

79 |

334 |

589 |

593 |

588 |

26 |

|

Nonalcoholic beverages |

74 |

197 |

757 |

1,178 |

1,093 |

1,078 |

54 |

|

Corn |

69 |

115 |

300 |

153 |

107 |

263 |

2 |

|

Soybeans |

63 |

17 |

121 |

99 |

134 |

163 |

1 |

|

Rice |

45 |

62 |

177 |

149 |

148 |

165 |

10 |

|

Wheat |

0 |

0 |

12 |

15 |

19 |

20 |

0 |

|

Pulses |

8 |

6 |

41 |

70 |

139 |

79 |

13 |

|

Live animals |

73 |

128 |

92 |

114 |

176 |

280 |

33 |

|

Sugar and sweeteners |

126 |

129 |

252 |

418 |

412 |

389 |

27 |

|

Distillers grains |

1 |

2 |

117 |

95 |

109 |

121 |

5 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Trade Data, BICO-HS10, accessed from fas.usda.gov/gats March 5, 2019.

Notes: Data are not adjusted for inflation. As defined by USDA, consumer-oriented products includes meats, fruit, vegetables, processed food products, beverages, and pet food.

a. "% share" reflect the Canadian market share of total global U.S. exports in each category.

Table 4 provides a summary of key U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico for selected years since FY1990. Total U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico grew from $2.7 billion in FY1990 to $3.7 billion in FY1995 after NAFTA came into force, reaching $18.8 billion in FY2018. Grains and meats account for the largest share of exports, but growth has been strong among most products including dairy, prepared food, fruit, tree nuts, sugars and sweeteners, wine and beer, and distillers dry grains.

Between FY2016 and FY2018, U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico averaged over $18 billion, accounting for 13% of the total value of U.S. agricultural exports to all destinations in FY2018 (Table 4). Consumer-ready products as a group account for a significant share of U.S. exports to Mexico at 13% of the total value of U.S. agricultural exports in FY2018. Mexico is also a major U.S. export market for a number of bulk agricultural commodities, meat, and dairy products. In FY2018, Mexico accounted for 25% of the total value of U.S. corn exports to all destinations, 24% of the total value of U.S. dairy exports, 22% each of the total value of U.S. pork and poultry exports, 12% of the total value of U.S. wheat exports, and 8% of the total value of U.S. soybeans exports to all destinations.

Table 4. Major U.S. Agriculture Exports to Mexico

Millions U.S. dollars, selected October 1-September 30 fiscal years

|

1990 |

1995 |

2009 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

% Share of Total U.S. Ag Exports, FY2018a |

|

|

Agricultural products |

2,671 |

3,720 |

13,325 |

17,618 |

18,608 |

18,845 |

13 |

|

Total consumer oriented |

553 |

1,156 |

5,135 |

8,073 |

8,326 |

8,590 |

13 |

|

Fresh vegetables |

11 |

30 |

145 |

111 |

110 |

148 |

6 |

|

Fresh fruit |

31 |

89 |

361 |

510 |

543 |

616 |

13 |

|

Snack foods |

27 |

40 |

181 |

293 |

292 |

306 |

12 |

|

Tree nuts |

10 |

20 |

144 |

265 |

251 |

358 |

4 |

|

Pork and pork products |

71 |

104 |

719 |

1,283 |

1,521 |

1,421 |

22 |

|

Dairy products |

75 |

130 |

657 |

1,186 |

1,350 |

1,346 |

24 |

|

Beef and beef products |

102 |

164 |

933 |

1,021 |

969 |

1,036 |

13 |

|

Poultry meat and products |

50 |

183 |

574 |

948 |

923 |

950 |

22 |

|

Eggs and products |

8 |

15 |

30 |

173 |

172 |

169 |

28 |

|

Wine and beer |

10 |

17 |

100 |

185 |

186 |

189 |

8 |

|

Nonalcoholic beverages |

6 |

40 |

77 |

131 |

127 |

123 |

6 |

|

Corn |

528 |

355 |

1,586 |

2,541 |

2,588 |

2,835 |

25 |

|

Soybeans |

217 |

413 |

1,362 |

1,366 |

1,607 |

1,667 |

8 |

|

Wheat |

46 |

116 |

595 |

528 |

923 |

619 |

12 |

|

Cotton |

39 |

186 |

390 |

334 |

401 |

372 |

6 |

|

Rice |

62 |

73 |

346 |

258 |

289 |

261 |

16 |

|

Live animals |

85 |

66 |

77 |

113 |

135 |

119 |

14 |

|

Sugar and sweeteners |

92 |

58 |

301 |

614 |

623 |

697 |

48 |

|

Distillers grains |

0 |

3 |

252 |

357 |

361 |

422 |

18 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Trade Data, BICO-HS10, accessed from fas.usda.gov/gats 5 March 2019.

Notes: Data are not adjusted for inflation. As defined by USDA, consumer-oriented products includes meats, fruit, vegetables, processed food products, beverages, and pet food.

a. "% Share" reflect the Mexican market share of total global U.S. exports in each category.

U.S. Imports from Canada and Mexico

U.S. agricultural imports from Canada and Mexico have increased in value from $26 billion in FY2009—the first full year since the complete market liberalization under NAFTA in 2008—to over $48 billion in FY2018 (Table 5).

Table 5. Major U.S. Agriculture Imports from Canada and Mexico

Millions U.S. dollars, selected October 1-September 30 fiscal years

|

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|||||||||||

|

From Canada |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total agriculture |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Snack foods |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Red meats |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Processed fruit and vegetables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Fresh vegetables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Live animals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Other vegetable oils |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Wheat |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Coarse grains |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Roasted, instant coffee |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Nursery products |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Feeds and fodders |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Planting seeds |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

From Mexico |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total agriculture |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Other fresh fruit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Fresh vegetables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Wine and beer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Snack foods |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Processed fruit and veg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Red meats |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Other consumer oriented |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Live animals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Tree nuts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Fruit and vegetable juices |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Bananas and plantains |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Roasted, instant coffee |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Trade Data accessed from fas.usda.gov/gats March 5, 2019.

Notes: Data are not adjusted for inflation.

Major U.S. imports from Canada include snack foods, meats, and processed fruit and vegetable products. U.S. purchases of hogs and cattle from Canada had increased since NAFTA began, but these imports have declined since FY2016. North American market dynamics and the prevailing hog cycle dynamics in the NAFTA countries have affected live animal trade patterns in recent years. Similarly, U.S. coarse grain imports from Canada have also declined in recent years, likely the result of larger U.S. feed grain supplies. U.S. imports from Mexico mostly consist of fresh fruit and vegetables, alcoholic beverages, snack foods, and processed fruit and vegetable products.

Economic Effects of NAFTA versus USMCA

Many studies have assessed the effects of NAFTA on agriculture and the possible effects if NAFTA were to be terminated. It is difficult to isolate the effects of NAFTA from the market liberalization begun under CUSTA and from Mexico's unilateral trade liberalization measures in the 1980s and early 1990s, which included joining the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1986.30 Nevertheless, NAFTA is credited with facilitating trade in North America by reducing tariffs and other market access barriers and by providing a stable and improved trading environment in the region.31 Studies conducted by USDA indicate that U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico have been higher than they would have been in the absence of NAFTA. One such study concluded that NAFTA particularly expanded trade in those commodities that underwent the most significant reductions in tariff and nontariff barriers, including U.S. exports to Canada of wheat products, beef and veal, and cotton and U.S. exports to Mexico of rice, cattle and calves, nonfat dry milk, cotton, processed potatoes, apples, and pears.32

An October 2018 study commissioned by the Farm Foundation examines the potential economic benefits associated with (1) USMCA compared with the provisions provided under NAFTA, (2) USMCA in an environment with prevailing retaliatory tariffs on U.S. agricultural products in response to U.S. tariff increases on imports of steel and aluminum, and (3) the effect of a complete U.S. withdrawal from USMCA/NAFTA.33 The methodology used by the study assumes that each of the three trade policy scenarios would need to remain in place for at least three to five years or until the market equilibrium stabilizes following the initial policy shock. Thus, the estimated effects from the study can be considered as the long-run impacts. The study considers only proposed changes under USMCA to market access for U.S. agricultural exports to Canada, such as changes in TRQs and tariff rates. It does not consider other changes proposed for agriculture or for other sectors such as manufacturing and automobiles. The study's conclusions under these three scenarios follow.

- 1. Comparing USMCA to NAFTA, the study estimates that USMCA would generate a net increase in annual U.S. agricultural exports to Canada of $450 million—about 1% of current U.S. exports under NAFTA. This estimated increase would reflect increases in exports of dairy products (+$280 million) and meat (+$210 million), which would be partially offset by a decline in exports of other agricultural products (-$40 million).

- 2. Under the scenario where USMCA would enter into force but the retaliatory tariffs imposed by Canada and Mexico on U.S. agricultural exports would remain in place, the study projects U.S. agricultural export losses from the retaliatory tariffs of $1.8 billion annually, which would more than offset the projected gains of $450 million from USMCA ratification.

- 3. Under the scenario of a U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA without USMCA ratification, tariffs on U.S. exports to Canada and Mexico would be expected to return to the higher WTO most-favored-nation (MFN) rates, the highest level of applied tariffs rates under WTO commitments. In this circumstance, the study finds that U.S. agricultural and food exports to Canada and Mexico would decline by about $12 billion, or 30% of the value of U.S. agricultural exports to these markets in FY2018. This loss is expected to be partially offset by an increase of $2.6 billion in U.S. exports to other countries for a net loss in export revenues of $9.4 billion. A loss of this order would represent a decline of 24% compared with the total value of U.S. agricultural exports to these countries in FY2018.

To date, similar studies assessing the effect of USMCA on U.S. agriculture as a whole are not available.

U.S. Agricultural Stakeholders on USMCA

Individual commodity groups have stated that they expect to benefit from market access gains. For example, the National Turkey Federation stated that USMCA would expand market access resulting in a 29% increase in U.S. turkey exports to Canada.34 A broad coalition of U.S. agricultural stakeholders is advocating for USMCA's approval,35 contending that the proposed agreement would further expand market access for U.S. agriculture. Most leading agriculture commodity groups have expressed their support for USMCA.36 The U.S. wheat industry states that although challenges remain in further opening commerce for U.S. wheat farmers near the border with Canada, USMCA retains tariff-free access to imported U.S. wheat for long-time flour milling customers in Mexico.37 The American Farm Bureau Federation expressed satisfaction that the USMCA not only locks in market opportunities previously developed but also builds on those trade relationships in several key areas.38

On the other hand, other farm sector stakeholders, such as the National Farmers Union and the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, have expressed concern that the proposed agreement does not go far enough to institute a fair trade framework that benefits family farmers and ranchers.39

Some agricultural market observers question whether the benefits to U.S. agriculture of USMCA over NAFTA will be more than incremental.40 Critics also point out that most U.S. agricultural exports currently enjoy zero tariffs under NAFTA and that the main market access gain under USMCA is through limited quota increases. A researcher for the International Food Policy Research Institute recently concluded that farm production costs would be expected to increase because of domestic content provisions in the agreement in tandem with the new U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum imports.41

Upon signing of the USMCA on November 30, 2018, President Trump stated, "This new deal will be the most modern, up-to-date, and balanced trade agreement in the history of our country, with the most advanced protections for workers ever developed."42 Regarding agriculture, Secretary Perdue echoed the sentiments expressed by most of the agricultural commodity groups: "The new USMCA makes important specific changes that are beneficial to our agricultural producers. We have secured greater access to the Mexican and Canadian markets and lowered barriers for many of our products. The deal eliminates Canada's unfair Class 6 and Class 7 milk pricing schemes, opens additional access to U.S. dairy into Canada, and imposes new disciplines on Canada's supply management system. The agreement also preserves and expands critical access for U.S. poultry and egg producers and addresses Canada's discriminatory wheat grading process to help U.S. wheat growers along the border become more competitive."43

Outlook for Proposed USMCA

The proposed USMCA would have to be approved by Congress and ratified by Mexico and Canada before entering into force.44 On August 31, 2018, pursuant to TPA, President Trump provided Congress a 90-day notification of his intent to sign a free trade agreement with Canada and Mexico. On January 29, 2019—60 days after an agreement was signed, and as required by TPA—U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer submitted to Congress changes to existing U.S. laws that would be needed to bring the United States into compliance with the proposed USMCA. A report by the USITC on the possible economic impact of TPA is not expected to be completed until April 20, 2019, due to the 35-day government shutdown. The report has been cited by some Members of Congress as key to their decisions on whether to support the agreement.45

Some policymakers have stated that the path to ratifying USMCA by Congress is uncertain partially because the three countries have yet to resolve disputes over tariffs on U.S. imports of steel and aluminum, as well as retaliatory tariffs that Canada and Mexico have imposed on U.S. agricultural products.46 The conclusion of the proposed USMCA did not resolve these tariff disputes.

On January 30, 2019, Senator Chuck Grassley called on the Trump Administration to lift tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from Canada and Mexico before Congress begins considering legislation to implement the USMCA.47 Representatives of the U.S. business community, agriculture interest groups, other congressional leaders, and Canadian and Mexican government officials have also stated that these tariff issues must be resolved before the USMCA enters into force.48

Other Members of Congress have raised issues regarding labor and environmental provisions of USMCA. Speaker Pelosi has stated that she wants "stronger enforcement language" and that the USMCA talks should be reopened to tighten enforcement provisions for labor and environmental protections.49

Some trade observers believe that delays in congressional action on USMCA could make it harder for Canada to consider USMCA approval this year because of upcoming parliamentary elections in October 2019.50