Introduction

This report provides an overview of the federal response to domestic violence—defined broadly to include acts of physical and nonphysical violence against spouses and other intimate partners—through the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA).1 FVPSA programs are carried out by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS's) Administration for Children and Families (ACF) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). ACF administers most FVPSA programming, including grants to states, territories, and Indian tribes to support local organizations that provide immediate shelter and related assistance for victims of domestic violence and their children. ACF also provides funding for a national domestic violence hotline that responds to calls, texts, and web-based chats from individuals seeking assistance. The funding for ACF also supports state domestic violence coalitions that provide training for and advocacy on behalf of domestic violence providers within each state, as well as multiple resource centers that provide training and technical assistance on various domestic violence issues for a variety of stakeholders. The CDC funds efforts to prevent domestic violence through a program known as Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Through Allies (DELTA). The House Committee on Education and Labor and the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pension (HELP) Committee have exercised jurisdiction over FVPSA.

The report begins with background on the definitions of domestic violence and related terms. This background section also describes the risk factors for domestic violence and estimates of the number of victims. The next section of the report addresses the history leading up to the enactment of FVPSA, and the major components of the act: a national domestic violence hotline, support for domestic violence shelters and nonresidential services, and community-based responses to prevent domestic violence. The report then discusses efforts under FVPSA to assist children and youth exposed to domestic violence, including teen dating violence.

Finally, the report provides an overview of FVPSA's interaction with other federal laws, including the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) and the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 (VAWA, P.L. 103-322). FVPSA was the first federal law to address domestic violence, with a focus on providing shelter and services for survivors; however, since the enactment of VAWA in 1994, the federal response to domestic violence has expanded to involve multiple departments and activities that include investigating and prosecuting crimes and providing additional services to victims and abusers. FVPSA also includes provisions that encourage or require program administrators to coordinate FVPSA programs with related programs and research carried out by other federal agencies. The appendices provide further detail about FVPSA-related definitions and funding, and statistics related to domestic violence victimization.

Background

Definitions

The FVPSA statute focuses on "family violence," which can involve many types of family relationships and forms of violence. FVPSA defines the term as acts of violence or threatened acts of violence, including forced detention, that result in physical injury against individuals (including elderly individuals) who are legally related by blood or marriage and/or live in the same household.2 This definition focuses on physical forms of violence and is limited to abusers and victims3 who live together or are related by blood or marriage; however, researchers and others generally agree that family violence is broad enough to include nonphysical violence and physical violence that occurs outside of an intimate relationship.4 Such a definition can encompass a range of scenarios—rape and other forms of sexual violence committed by a current or former spouse or intimate partner who may or may not live in the same household; stalking by a current or former spouse or partner; abuse and neglect of elderly family members and children; and psychologically tormenting and controlling a spouse, intimate partner, or other member of the household.

While family violence can encompass child abuse and elder abuse, FVPSA programs focus on individuals abused by their spouses and other intimate partners. Further, FVPSA references the terms "domestic violence" and "dating violence" as they are defined under VAWA, and discusses these terms alongside family violence. (The FVPSA regulations also define these terms as generally consistent with VAWA, but recognize that the term "dating violence" encompasses additional acts.)5 The VAWA definition of "domestic violence" encompasses forms of intimate partner violence—involving current and former spouses or individuals who are similarly situated to a spouse, cohabiting individuals, and parents of children in common—that are outlawed under state or local laws. VAWA defines "dating violence" as violence committed by a person who has been in a social relationship of a romantic or intimate nature with the victim; and where the existence of such a relationship is determined based on consideration of the length of the relationship, the type of relationship, and the frequency of interaction between the individuals involved. (Appendix A provides a summary of these and related terms as they are defined in statute.)

The federal government responds to child abuse and elder abuse through a variety of separate programs. Federal law authorizes and funds a range of activities to prevent and respond to child abuse and neglect under Titles IV-B and IV-E of the Social Security Act and CAPTA.6 Separately, the Older Americans Act (OAA), the major federal vehicle for the delivery of social and nutrition services for older persons, has authorized projects to address elder abuse. In addition, the OAA authorizes, and the federal government funds, the National Center on Elder Abuse. The center provides information to the public and professionals regarding elder abuse prevention activities, and provides training and technical assistance to state elder abuse agencies and to community-based organizations.7 The Social Services Block Grant, as amended, also includes elder justice provisions, including several grant programs and other activities to promote the safety and well-being of older Americans.8

Risk Factors for Domestic Violence

The evidence base on domestic violence does not point strongly to any one reason that it is perpetrated, in part because of the difficulty in measuring social conditions (e.g., status of women, gender norms, and socioeconomic status, among others) that can influence this violence. Still, the research literature has identified two underlying influences: the unequal position of women and the normalization of violence, both in society and some relationships.9 Certain risk variables are often associated with—but not necessarily the causes—of domestic violence. Such factors include a pattern of problem drinking, poverty and economic conditions, and early parenthood.10 For example, substance abuse often precedes incidents of domestic violence. A U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) study found that substance abuse tracked closely with homicide, attempted homicide, or the most severe violent incidents of abuse perpetrated against an intimate partner. Among men who killed or attempted to kill their intimate partners, over 80% were problem drinkers in the year preceding the incident.11

Profiles of Survivors

Estimating the number of individuals involved in domestic violence is complicated by the varying definitions of the term and methodologies for collecting data. For example, some research counts a boyfriend or girlfriend as a family relationship while other research does not; still other surveys are limited to specific types of violence and whether violence is reported to police. Certain studies focus more broadly on various types of violence or more narrowly on violence committed among intimate partners. In addition, domestic violence is generally believed to be underreported. Survivors may be reluctant to disclose their victimization because of shame, embarrassment, fear, or belief that they may not receive support from law enforcement.12

Overall, two studies—the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) and the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS)—show that violence involving intimate partners is not uncommon, and that both women and men are victimized sexually, physically, and psychologically.13 Women tend to first be victimized at a younger age than men. Further, minority women and men tend to be victimized at higher rates than their white counterparts.

National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey

NISVS provides information on the prevalence of domestic violence among individuals during their lifetimes and in the past 12 months prior to the survey. The CDC conducted the study annually in each of 2010-2012 and in 2015.14 The survey examines multiple aspects of intimate partner violence—including contact sexual violence, which encompasses rape and other acts; physical violence, including slapping, kicking, and more severe acts like being burned; and stalking, which is a pattern of harassing or threatening tactics. Select findings from the study are summarized in Table B-1. Generally, the 2015 survey found that women and men were victimized at about the same rate over their lifetime.15 Over one-third (36%) of women and more than one-third (34%) of men in the United States reported that they experienced sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetimes. However, women were more likely than men to experience certain types of intimate partner violence, including contact sexual violence (18% vs. 8%), stalking (10% vs. 2%), and severe physical violence (21% vs. 15%). Women were also much more likely than men to report an impact related to partner violence over their lifetimes (25% vs 11%). Such impacts included having injuries, being fearful, being concerned for their safety, missing work or school, needing medical care, or needing help from law enforcement.

Women and men of color, particularly individuals who are multiracial, tended to experience domestic violence at higher lifetime rates. As reported in the 2010 NISVS, women who are multiracial (57%) were most likely to report contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner, followed by American Indian or Alaska Native women (48%), black women (45%), white women (37%), Hispanic women of any race (34%), and Asian or Pacific Islander women (18%). Among men, those who were black (40%) and multiracial (39%) were more likely to experience intimate partner violence than white (32%) and Hispanic (29%) men; estimates were not reported for American Indian or Alaska Native or Asian or Pacific Islander males because the data were unreliable.16

Special Populations

The 2010 NISVS examined the prevalence of this violence based on how adult respondents identified their sexual orientation (heterosexual or straight, gay or lesbian, or bisexual). The study found that overall, bisexual women had significantly higher lifetime prevalence of sexual violence, physical violence, and stalking by an intimate partner when compared to both lesbian and heterosexual women.17

The 2010 NISVS also surveyed women on active duty in the military and the wives of active duty men. These women were asked to respond to whether they experienced intimate partner violence over their lifetime and during the four years prior to the survey. The study found that the majority of women affiliated with the military were significantly less likely to be victims of intimate partner violence compared to women in the general population. However, active duty women who were deployed during the three years prior to the survey were significantly more likely to have experienced intimate partner violence during this period and over their lifetime compared to active duty women who were not deployed. Among those who deployed, 12% had been victims of physical violence, rape, or stalking by an intimate partner during the past three years and 35% had experienced victimization over their lifetime. This is compared to 10% (during the past three years) and 28% (lifetime prevalence) of women who had not deployed.18

National Crime Victimization Survey

The National Crime Victimization Survey is a survey coordinated by DOJ's Bureau of Justice Statistics within the Office of Justice Programs.19 NCVS surveys a nationally representative sample of households. It is the primary source of information on the characteristics of criminal nonfatal victimization and on the number and types of crimes that may or may not be reported to law enforcement authorities. NCVS surveyed respondents about whether they have been victims of a violent crime, including rape/sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and simple assault; and for victims, the relationship to the perpetrator.20 The survey reports the share of crimes that are committed by an intimate partner (current or former spouses, boyfriends, or girlfriends), other family members, friends/acquaintances, or strangers. The survey found that nearly 600,000 individuals were victims of intimate partner violence in 2016.21 An earlier NCVS study examined changes in the rate of intimate partner violence over time. The study found that the number of female victims of domestic violence declined from 1.8 million in 1994 to about 621,000 in 2011. Over this period, the rate of serious intimate partner violence—rape or sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault—declined by 72% for females and 64% for males. Approximately 4% of females and 8% of males who were victimized by intimate partners were shot at, stabbed, or hit with a weapon over the period from 2002 through 2011.22

Effects of Domestic Violence

Domestic violence is associated with multiple negative outcomes for victims, including mental and emotional distress and health effects. The 2015 NISVS study found that these effects appeared to be greater for women. About 1 in 4 women (25.1%) and 1 in 10 men (10.9%) who experienced sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime reported at least one impact as a result of this violence, including being fearful; being concerned for their safety or having an injury or need for medical care; needing help from law enforcement; missing at least one day of work; or missing at least one day of school.23

Domestic Violence: Development of the Issue

Early marriage laws in the United States permitted men to hit their wives, and throughout much of the 20th century family violence remained a hidden problem.24 Victims, mostly women, often endured physical and emotional abuse in silence. These victims were hesitant to seek help because of fear of retaliation by their spouses/partners and concerns about leaving their homes, children, and neighborhoods behind. Women were worried that they would be perceived as deviant or mentally unstable or would be unable to get by financially. In addition, victims were often blamed for their abuse, based on stereotypical notions of women (e.g., demanding, aggressive, and frigid, among other characteristics).25

In the 1960s, shelters and services for victims of domestic violence became available on a limited basis; however, these services were not always targeted specifically to victims per se. Social service and religious organizations provided temporary housing for displaced persons generally, which could include homeless and abused women. In addition, a small number of organizations provided services to abused women who were married to alcoholic men. Beginning in the 1970s, the "battered women's movement" began to emerge; it sought to heighten awareness of women who were abused by spouses and partners. The movement developed from influences both abroad and within the United States. In England, the first battered women's shelter, Chiswick Women's Aid, galvanized support to establish similar types of services. In addition, the feminist movement in the United States increasingly brought greater national attention to the issue.26

As part of the battered women's movement, former battered women, civic organizations, and professionals opened shelters and began to provide services to victims, primarily abused women and their children.27 Shelters were most often located in old homes, at Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) centers, or housed in institutional settings, such as motels or abandoned orphanages.

In addition to providing shelter, groups in the battered women's movement organized coalitions to combine resources for public education on the issue, support groups for victims, and services that were lacking. For example, the YWCA and Women in Crisis Can Act formed a hotline for abused women in Chicago. These and other groups convened the Chicago Abused Women's Coalition to address concerns about services for battered women. The coalition spoke to hundreds of community groups and professional agencies about battered women's stories, explained the significance of violence, detailed how violence becomes sanctioned, dispelled common myths, and challenged community members to provide funding and other support to assist abused women. The coalition mobilized around passage of a state law to protect women and require police training on domestic violence, among other accomplishments.28

Based on a survey in the late 1970s, 111 shelters were believed to be operating across all states and in urban, suburban, and rural communities. These shelters generally reported that they provided a safe and secure environment for abused women and their children, emotional support and counseling for abused women, and information on legal rights and assistance with housing, among other supports. Approximately 90 of these shelters fielded over 110,000 calls for assistance in a given year.29

Around this same time, the public became increasingly aware of domestic violence. In 1983, Time magazine published an article, "Wife Beating: The Silent Crime," as part of a series of articles on violence in the United States. The article stated: "There is nothing new about wife beating…. What is new is that in the U.S. wife beating is no longer widely accepted as an inevitable and private matter. The change in attitude, while far from complete, has come about in the past 10 to 15 years as part of the profound transformation of ideas about the roles and rights of women in society."30 In 1984, then-U.S. Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti established the Department of Justice Task Force on Family Violence, which issued a report examining the scope and impact of domestic violence in America. The report also provided recommendations to improve the nation's law enforcement, criminal justice, and community response to offenses that were previously considered "family matters."31

Congressional Response

Largely as a result of efforts by advocates and the Justice Department, Congress began to take an interest in domestic violence issues. The House Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families conducted a series of hearings in 1983 and 1984 on child abuse and family violence throughout the country, to understand the scope of family violence better and explore possible federal responses to the problem. The committee heard from victims, domestic violence service providers, researchers, law enforcement officials, and other stakeholders about the possible number of victims and the need for additional victim services. In 1984, the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA) was enacted as Title III of the Child Abuse Amendments of 1984 (P.L. 98-457). Title I of that law amended the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), and most of the seven subsequent reauthorizations of FVPSA have occurred as part of legislation that reauthorized CAPTA.32 This includes the most recent reauthorization (P.L. 111-320), which extended funding authority for FVPSA through FY2015. As discussed later in this report, Congress subsequently broadened the federal response to domestic violence with the enactment of the Violence Against Women Act of 1994.

FVPSA Overview

As originally enacted, FVPSA included both a social service and law enforcement response to preventing and responding to domestic violence. Grants were authorized for states, territories, and Indian tribes to establish and expand programs to prevent domestic violence and provide shelter for victims. In addition, the law authorized grants to provide training and technical assistance to law enforcement personnel, and this funding was ultimately used to train law enforcement personnel throughout the country. From FY1986 through FY1994, funding for these grants was transferred from HHS to DOJ, which carried out the grants under the Office for Victims of Crime (OVC). DOJ funded 23 projects to train law enforcement officers on domestic violence policies and response procedures, with approximately 16,000 law enforcement officers and other justice system personnel from 25 states receiving this training. The training emphasized officers as participants working with other agencies, victims, and community groups in a coordinated response to domestic violence.33 Over time, FVPSA was expanded to include support of other activities, including state domestic violence coalitions and grants that focus on prevention activities; however, authorization of funding for FVPSA law enforcement training grants was discontinued in 1992, just before the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 authorized a similar purpose. Specifically, VAWA authorizes training and support of law enforcement officials under the Services, Training, Officers, and Prosecutors (STOP) Grant program.

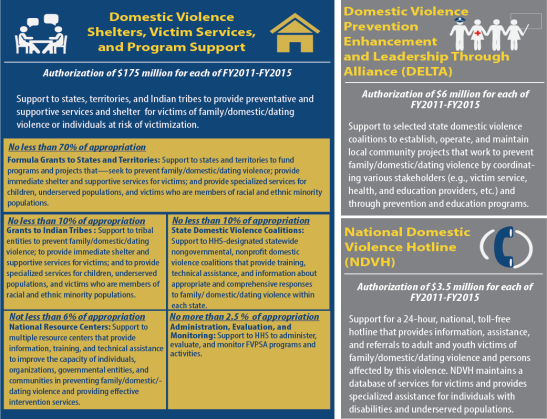

As outlined in Figure 1, FVPSA currently authorizes three major activities: domestic violence prevention activities under a program known as DELTA; the national domestic violence hotline; and domestic violence shelters, services, and program support. The CDC administers the DELTA program. The Family and Youth Services Bureau (FYSB) in HHS/ACF administers funding for the hotline and the domestic violence shelters and support.

|

Figure 1. Summary of Activities Authorized and Funded Under the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). |

Funding

Authorization of funding under FVPSA has been extended multiple times, most recently through FY2015 by the CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-320). Congress has appropriated funding in subsequent years. Table 1 includes actual funding from FY1993 to FY2018, which includes reductions in some years, and appropriated funding for FY2019 for the three major FVPSA activities. Congress appropriated just over $180 million for FY2019, the highest total to date.

|

DELTA |

National Domestic |

Shelter, Services, |

Total |

|

|

FY1993 |

N/A |

N/A |

$24,678,619 |

$24,678,619 |

|

FY1994 |

N/A |

N/A |

$32,645,000 |

$32,645,000 |

|

FY1995 |

N/A |

$1,000,000 |

$32,645,000 |

$33,645,000 |

|

FY1996 |

N/A |

$400,000 |

$47,642,500 |

$48,042,500 |

|

FY1997 |

N/A |

$400,000 |

$72,800,000 |

$73,200,000 |

|

FY1998 |

N/A |

$1,200,000 |

$86,642,206 |

$87,842,206 |

|

FY1999 |

$5,998,000 |

$1,200,000 |

$88,778,000 |

$95,976,000 |

|

FY2000 |

$5,866,000 |

$1,957,000 |

$101,118,000 |

$108,941,000 |

|

FY2001 |

$5,866,000 |

$2,157,000 |

$116,899,000 |

$124,922,000 |

|

FY2002 |

$5,866,000 |

$2,157,000 |

$124,459,000 |

$132,482,000 |

|

FY2003 |

$5,828,000 |

$2,157,000 |

$124,459,000 |

$132,444,000 |

|

FY2004 |

$5,303,000 |

$2,982,000 |

$125,648,000 |

$133,933,000 |

|

FY2005 |

$5,258,000 |

$3,224,000 |

$125,630,000 |

$134,112,000 |

|

FY2006 |

$5,181,000 |

$2,970,000 |

$124,643,000 |

$132,794,000 |

|

FY2007 |

$5,110,000 |

$2,970,000 |

$124,731,000 |

$132,811,000 |

|

FY2008 |

$5,021,000 |

$2,918,000 |

$122,552,000 |

$130,491,000 |

|

FY2009 |

$5,511,000 |

$3,209,000 |

$127,776,000 |

$136,496,000 |

|

FY2010a |

$5,525,000 |

$3,209,000 |

$130,052,000 |

$138,786,000 |

|

FY2011 |

$5,423,000 |

$3,202,000 |

$129,792,000 |

$138,417,000 |

|

FY2012 |

$5,411,000 |

$3,197,000 |

$129,547,000 |

$138,155,000 |

|

FY2013b |

$5,350,000 |

$2,992,000 |

$121,225,000 |

$129,552,000 |

|

FY2014c |

$5,414,000 |

$4,500,000 |

$133,521,000 |

$143,221,000 |

|

FY2015c |

$5,414,000 |

$4,500,000 |

$135,000,000 |

$144,914,000 |

|

FY2016c |

$5,500,000 |

$8,250,000 |

$150,000,000 |

$163,750,000 |

|

$5,487,000 |

$8,223,479 |

$150,517,702 |

$164,210,518 |

|

|

$5,500,000 |

$9,250,000 |

$158,398,811 |

$173,148,811 |

|

|

FY2019c |

$5,500,000 |

$10,250,000 |

$164,500,000 |

$180,250,000 |

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Administration for Children and Families (ACF), FY1998-FY2020 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees; and Congressional Research Service correspondence with HHS, ACF and HHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), September and November 2012, April 2016, August 2017, and November 2018; HHS, ACF, ACF Operating Plans FY2013-FY2018, and HHS, CDC, CDC Operating Plans FY2013-FY2018; U.S. Congress, House Committee on Rules, 113th Cong., 2nd sess., Committee Print 113-32 to the Senate Amendment to the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014 (H.R. 3547), which was enacted as P.L. 113-76; Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2015 (P.L. 113-235); U.S. Congress, House Committee on Rules, 114th Cong., 1st sess., Rules Committee Print 114-39 to accompany the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (H.R. 2029), which was enacted as P.L. 114-113; U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Congressional Record, vol. 163, part No. 76, Book III (May 3, 2017), p. H3952 and p. H3994; U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Congressional Record, vol., 164, part No. 50, Book III (March 22, 2018), p. H2700 and p. H2745; and U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., Conference Report to Accompany Department of Defense and Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations Act, 2019 and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2019 (H.R. 6157), which was enacted as P.L. 115-245.

Notes: Funding is allocated for DELTA via HHS/CDC; and shelter, support services, and program support and the Domestic Violence Hotline via HHS/ACF. N/A means not applicable.

a. Funding for FY2010 was just over $130 million. When FY2010 dollars were appropriated in December 2009, FVPSA required that "a portion of the excess" (of funds for shelter, support services, and program support) above $130 million was to be reserved for projects to address the needs of children who witness domestic violence. This rule was triggered in FY2010 and the excess funding went to a grant program, Expanding Services for Children and Youth Exposed to Domestic Violence. FVPSA was reauthorized in December 2010, and this provision was changed to require that when the appropriation exceeds $130 million, HHS must first reserve 25% of the excess funding for specialized services for abused parents and children exposed to domestic violence (42 U.S.C. §10403(a)(2)(A)(i)).

b. The final appropriations law for FY2013 was Consolidated and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2013 (P.L. 113-6). The FY2013 funding levels provided were based on the operating plan provided by HHS to Congress. This funding included a 0.2% rescission, per P.L. 113-6, and a sequestered amount of 5.0%, per the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), as amended by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-240).

c. Funding exceeded $130 million in each of FY2014 through FY2019, triggering the requirement under FVPSA that HHS must first reserve 25% of the excess funding for specialized services for abused parents and children exposed to domestic violence. The FY2016 appropriations request notes that "[i]n previous budgets [FY2013 through FY2015], this provision was overridden in order to direct resources to shelters." HHS, ACF, FY2016 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, p. 212; and based on correspondence with HHS, ACF, April 2016. Of excess funding available for 2016, $5 million has been reserved for specialized services for abused parents and children exposed to domestic violence and related technical assistance. Of the $20.5 million in excess funding for FY2017, $5.1 million has been reserved for these supports. HHS, ACF, FY2017 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees; and CRS correspondence with HHS, ACF, April 2016 and August 2017. Of the $35 million in excess funding for FY2018, $5.6 million has been reserved for these supports. CRS correspondence with HHS, ACF, November 2018.

d. The final appropriations law for HHS was the Consolidated and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31). The FY2017 funding levels provided are based on the operating plan provided by HHS to Congress, with further information from HHS that funds were subsequently transferred from Shelter, Services, and Support ($482,298) and the National Domestic Violence Hotline ($26,521) under the 1% transfer authority for the HHS Secretary in P.L. 115-31. CRS correspondence with HHS, ACF, April 2016 and August 2017; and HHS, "FY2017 ACF Operating Plan" and "FY2017 CDC Operating Plan."

e. The final appropriations law for HHS was the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141). The FY2018 funding levels provided are based on the operating plan provided by HHS to Congress, with further information from HHS that funds were subsequently transferred from Shelter, Services, and Support ($1,600,000) under the 1% transfer authority for the HHS Secretary in P.L. 115-141 and $1,889 in lapsed appropriations. CRS correspondence with HHS, ACF, November 2018; and HHS, "FY2018 ACF Operating Plan" and "FY2018 CDC Operating Plan."

Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Through Alliances (DELTA)34

Since 1994, FVPSA has authorized the HHS Secretary to award cooperative agreements to state domestic violence coalitions that coordinate local community projects to prevent domestic violence, including such violence involving youth. Congress first awarded funding for prevention activities in FY1996 under a pilot program carried out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The pilot program was formalized in 2002 under a program now known as the Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Through Alliances (DELTA) program. The focus of DELTA is preventing domestic violence before it occurs, rather than responding once it happens or working to prevent its recurrence.35 The program has had four iterations:

- DELTA, which was funded from FY1996 through FY2012 and involved 14 states;

- DELTA Prep, which extended from FY2008 through FY2012 and involved 19 states that had not received the initial DELTA funds;

- DELTA FOCUS, which extended from FY2013 through FY2017 and involved 10 states, all of which had previously received funding under DELTA or DELTA Prep; and

- DELTA Impact, which began with FY2018 and involves 10 states, all of which except one has previously received DELTA funding.

As originally implemented, the program provided funding and technical assistance to 14 state domestic violence coalitions to support local efforts to carry out prevention strategies and work at the state level to oversee these strategies. Local prevention efforts were referred to as coordinated community responses (CCRs). The CCRs were led by domestic violence organizations and other stakeholders across multiple sectors, including law enforcement, public health, and faith-based organizations. For example, the Michigan Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence supported two CCRs—the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services and the Lakeshore Alliance Against Domestic and Sexual Violence—that focused on faith-based initiatives. Both CCRs held forums that provided resources and information about the roles of faith leaders in preventing the first-time occurrence of domestic violence. The 14 state domestic violence coalitions developed five- to eight-year domestic violence prevention plans known as Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Plans. These plans were developed with multiple stakeholders, and they discuss the strategies needed to prevent first-time perpetration or victimization and to build the capacity to implement these strategies. The CDC issued a brief that summarizes the plans and identifies the successes and challenges for state domestic violence coalitions in supporting and enhancing intimate partner violence prevention efforts. Overall, the report found that states improved their capacity to respond to intimate partner violence through evidence-based planning and implementation strategies.36

DELTA Prep

DELTA Prep was a project that extended from FY2008 through FY2012, and was a collaborative effort among the CDC, the CDC Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.37 Through DELTA Prep, the CDC extended the DELTA Program to 19 states38 that did not receive the initial DELTA funds. State and community leaders in these other states received training and assistance in building prevention strategies, based on the work of the 14 state domestic violence coalitions that received DELTA funds. DELTA Prep states integrated primary prevention strategies into their work and the work of their partners, and built leadership for domestic violence prevention in their states.

DELTA FOCUS

DELTA FOCUS (Focusing on Outcomes for Communities United within States) continued earlier DELTA work. From FY2013 through FY2017, DELTA FOCUS funded 10 state domestic violence coalition grantees to implement and evaluate strategies to prevent domestic violence. Funding was provided by the coalitions to 18 community response teams that engaged in carrying out these strategies.39 DELTA FOCUS differed from DELTA and DELTA Prep by placing greater emphasis on implementing prevention strategies rather than building capacity for prevention. DELTA FOCUS also put more emphasis on evaluating the program to help build evidence about effective interventions.

DELTA Impact

DELTA Impact, which began in FY2018, provides funding to 10 state domestic violence coalitions.40 This grant supports community response teams in decreasing domestic violence risk factors and increasing protective factors by implementing prevention activities that are based on the best available evidence. Grantees are implementing and evaluating policy efforts under three broad strategies to address domestic violence prevention: (1) engaging influential adults and peers, including by engaging men and boys as allies in prevention; (2) creating protective environments, such as improving school climates and safety; and (3) strengthening economic supports for families.

National Domestic Violence Hotline41

As amended by the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) of 1994, FVPSA directs the HHS Secretary to award a grant to one or more private entities to operate a 24-hour, national, toll-free hotline for domestic violence. Since 1996, HHS has competitively awarded a cooperative agreement to the National Council on Family Violence in Texas to operate the National Domestic Violence Hotline (hereinafter, hotline).42 The agreement was most recently awarded for a five-year period that extends through the end of FY2020.

FVPSA requires that the hotline provide information and assistance to adult and youth victims of domestic violence, family and household members of victims of such violence, and "persons affected by victimization." This includes support related to domestic violence, children exposed to domestic violence, sexual assault, intervention programs for abusive partners, and related issues. As required under FVPSA, the hotline carries out multiple activities:

- It employs, trains, and supervises personnel to answer incoming calls; provides counseling and referral services; and directly connects callers to service providers. In FY2018, the hotline received about 23,000 calls each month and responded to 74% of all calls. It also had an average of nearly 4,000 online chats on a monthly basis. HHS reported that some calls were missed due to increased media coverage of domestic violence, increased Spanish chat services, and forwarding of calls from local domestic violence hotlines due to severe weather.43

- It maintains a database of domestic violence services for victims throughout the United States, including information on the availability of shelter and services.

- It provides assistance to meet the needs of special populations, including underserved populations, individuals with disabilities, and youth victims of domestic violence and dating violence. The hotline provides access to personnel for callers with limited English proficiency and persons who are deaf and hard of hearing.

Since 2007, the hotline has operated a separate helpline for youth victims of domestic violence, the National Dating Abuse Helpline (known as loveisrespect.org), which is funded through the appropriation for the hotline. This helpline offers real-time support primarily from peer advocates trained to provide support, information, and advocacy to those involved in abusive dating relationships, as well as others who support victims.44 In FY2018, the helpline received a monthly average of about 2,400 calls; 4,000 online chats; and nearly 1,300 texts.45

A 2019 study of these two lines examined a number of their features, including who contacts the lines, the study needs and demographic characteristics of those contacts, how contacts reach the lines, and the type of support they receive. The study found that nearly half (48%) the contacts were victims/survivors and another 39% did not identify themselves. The remaining contacts were from family/friends, abusers, and service providers. According to the study, the service most commonly provided to contactors was emotional support and contactors valued this support highly.46 The National Domestic Violence Hotline has collaborated with the National Indigenous Women's Resource Center to develop and fund the StrongHearts Native Helpline for Native American survivors of domestic abuse.47 The helpline uses the technology and infrastructure of the hotline, and draws from the National Indigenous Women's Resource Center to provide Native-centered, culturally appropriate services for survivors and others.

Overview of Shelter, Services, and Support

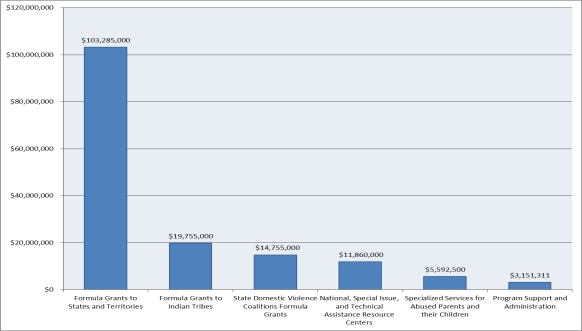

Funding for shelter, support services, and program support (hereinafter, shelter and services) encompasses multiple activities: formula grants to states and territories; grants to tribes; state domestic violence coalitions; national and special issue resource centers, including those that provide technical assistance; specialized services for abused parents and children exposed to domestic violence; and program support and administration. Figure 2 shows FY2018 allocations for activities included as part of shelter, support services, and program support.

The following sections of the report provide further information about grants to states, territories, and tribes; and state domestic violence coalitions. In addition, the report provides information about national and special issue resource centers. The section of the report on services for children and youth exposed to domestic violence includes information about FY2018 and earlier support for specialized services for abused parents and children exposed to domestic violence.

Formula Grants to States, Territories, and Tribes

No less than 70% of FVPSA appropriations for shelter and services must be awarded to states and territories through a formula grant. The formula grant supports the establishment, maintenance, and expansion of programs and projects to prevent incidents of domestic violence and to provide shelter and supportive services to victims of domestic violence. Each of the territories—Guam, American Samoa, U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands—receives no less than one-eighth of 1% of the appropriation, or, in combination, about one-half of 1% of the total amount appropriated. Of the remaining funds, states (including the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) receive a base allotment of $600,000 and additional funding based on their relative share of the U.S. population.48 Appendix C provides formula funding for FY2018 and FY2019 by state and territory.

In addition, no less than 10% of FVPSA appropriations for shelter and services are awarded to Indian tribes. Indian tribes have the option to authorize a tribal organization or a nonprofit private organization to submit an application for and to administer FVPSA funds.

In applying for grant funding, states and territories (hereinafter, states) must make certain assurances pertaining to the use and distribution of funds and to victims. Nearly all of the same requirements that pertain to states and territories also pertain to tribes.

Selected Grant Conditions Pertaining to Use and Distribution of Funds49

States may use up to 5% of their grant funding for state administrative costs. The remainder of the funds are used to make subgrants to eligible entities for community-based projects (hereinafter, subgrantees) that meet the goals of the grant program. No less than 70% of subgrant funding is to be used to provide temporary shelter and related supportive services, which include the physical space in which victims reside as well as the expenses of running shelter facilities.50 No less than 25% of subgrant funding is to be used for the following supportive services and prevention services:51

- assisting in the development of safety plans, and supporting efforts of victims to make decisions about their ongoing safety and well-being;

- providing individual and group counseling, peer support groups, and referrals to community-based services to assist victims and their dependents in recovering from the effects of domestic violence;

- providing services, training, technical assistance, and outreach to increase awareness of domestic violence and increase the accessibility of these services;

- providing culturally and linguistically appropriate services;

- providing services for children exposed to domestic violence, including age-appropriate counseling, supportive services, and services for the nonabusing parent that support that parent's role as caregiver (which may include services that work with the nonabusing parent and child together);

- providing advocacy, case management services, and information and referral services concerning issues related to domestic violence intervention and prevention, including providing assistance in accessing federal and state financial assistance programs; legal advocacy; medical advocacy, including provision of referrals for appropriate health care services (but not reimbursement for any health care services); assistance in locating and securing safe and affordable permanent housing and homelessness prevention services; and transportation, child care, respite care, job training and employment services, financial literacy services and education, financial planning, and related economic empowerment services;

- providing parenting and other educational services for victims and their dependents; and

- providing prevention services, including outreach to underserved populations.

States must also provide assurances that they will consult with and facilitate the participation of state domestic violence coalitions in planning and monitoring the distribution of grants and administering the grants (the role of state domestic violence coalitions is subsequently discussed further).52 States must describe how they will involve community-based organizations, whose primary purpose is to provide culturally appropriate services to underserved populations, including how such organizations can assist states in meeting the needs of these populations. States must further provide assurances that they have laws or procedures in place to bar an abuser from a shared household or a household of the abused persons, which may include eviction laws or procedures, where appropriate. Such laws or procedures are generally enforced by civil protection orders, or restraining orders to limit the perpetrators' physical proximity to the victim.

In funding subgrantees, states must "give special emphasis" to supporting community-based projects of "demonstrated effectiveness" carried out by nonprofit organizations that operate shelters for victims of domestic violence and their dependents; or that provide counseling, advocacy, and self-help services to victims. States have discretion in how they allocate their funding, so long as they provide assurances that grant funding will be distributed equitably within the state and between urban and rural areas of the state.

|

What are "eligible entities" that can receive subgrant funding from states? A local public agency, or nonprofit private organization—including faith-based and charitable organizations, community-based organizations, tribal organizations, and voluntary associations—that assists victims of domestic violence and their dependents and has a documented history of effective work on this type of violence; or a partnership of two or more agencies or organizations that includes an agency or organization described above and an agency or organization that has a demonstrated history of serving populations in their communities, including providing culturally appropriate services. Source: 42 U.S.C. §10408(c). |

Subgrantees that receive funding must provide a nonfederal match—of not less than $1 for every $5 of federal funding—directly from the state or through donations from public or private entities.53 The matching funds can be in cash or in kind. Further, federal funds made available to a state must supplement, and not supplant, other federal, state, and local public funds expended on services for victims of domestic violence.

States have two years to spend funds. For example, funds allotted for FY2019 may be spent in FY2019 or FY2020. The HHS Secretary is authorized to reallocate the funds of a state, by the end of the sixth month of a fiscal year that funds are appropriated, if the state fails to meet the requirements of the grant. The Secretary must notify the state if its application for funds has not met these requirements. State domestic violence coalitions are permitted to help determine whether states are in compliance with these provisions. States are allowed six months to correct any deficiencies in their application.

Selected Grant Conditions Pertaining to Victims54

In FY2017, programs funded by grants for states and tribes supported over 240,000 clients in residential settings and more than 1 million clients in nonresidential settings. Nearly 93% of clients reported that they had improved knowledge of planning for their safety. Also in FY2017, programs were not able to meet 226,000 requests for shelter.55

The grant for states addresses the individual characteristics and privacy of participants and shelters. Both states and subgrantees funded under FVPSA may not deny individuals from participating in support programs on the basis of disability, sex, race, color, national origin, or religion (this also applies to FPVSA-funded activities generally). In addition, states and subgrantees may not impose income eligibility requirements on individuals participating in these programs. Further, states and subgrantees must protect the confidentiality and privacy of victims and their families to help ensure their safety. These entities are prohibited from disclosing any personally identifying information collected about services requested, and from revealing personally identifying information without the consent of the individual, as specified in the law. If disclosing the identity of the individual is compelled by statutory or court mandate, states and subgrantees must make reasonable attempts to notify victims, and they must take steps to protect the privacy and safety of the individual.

States and subgrantees may share information that has been aggregated and does not identify individuals, and information that has been generated by law enforcement and/or prosecutors and courts pertaining to protective orders or law enforcement and prosecutorial purposes. In addition, the location of confidential shelters may not be made public, except with written authorization of the person(s) operating the shelter. Subgrantees may not provide direct payment to any victim of domestic violence or the dependent(s) of the victim. Further, victims must be provided shelter and services on a voluntary basis. In other words, providers cannot compel or force individuals to come to a shelter, participate in counseling, etc.

State Domestic Violence Coalitions56

Since 1992, FVPSA has authorized funding for state domestic violence coalitions (SDVCs). A SDVC is defined under the act as a statewide nongovernmental, nonprofit private domestic violence organization that (1) has a membership that includes a majority of the primary-purpose domestic violence service providers in the state;57 (2) has board membership that is representative of domestic violence service providers, and that may include representatives of the communities in which the services are being provided; (3) has as its purpose to provide education, support, and technical assistance to such service providers so they can maintain shelter and supportive services for victims of domestic violence and their dependents; and (4) serves as an information clearinghouse and resource center on domestic violence for the state and supports the development of policies, protocols, and procedures to enhance domestic violence intervention and prevention in the state.58

Funding for SDVCs is available for each of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and four territories (American Samoa, Guam, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands). Each jurisdiction has one SDVC, and these coalitions are designated by HHS. Funding is divided evenly among these 56 jurisdictions. SDVCs must use FVPSA funding for specific activities, as follows:

- working with local domestic violence service programs and providers of direct services to encourage appropriate and comprehensive responses to domestic violence against adults or youth within the state, including providing training and technical assistance and conducting needs assessments;

- participating in planning and monitoring the distribution of subgrants and subgrant funds within the state under the grant program for states and territories;

- working in collaboration with service providers and community-based organizations to address the needs of domestic violence victims and their dependents who are members of racial and ethnic minority populations and underserved populations;

- collaborating with and providing information to entities in such fields as housing, health care, mental health, social welfare, or business to support the development and implementation of effective policies, protocols, and programs that address the safety and support needs of adult and youth victims of domestic violence;

- encouraging appropriate responses to cases of domestic violence against adult and youth victims, including by working with judicial and law enforcement agencies;

- working with family law judges, criminal court judges, child protective service agencies, and children's advocates to develop appropriate responses to child custody and visitation issues in cases of children exposed to domestic violence, and in cases where this violence is concurrent with child abuse;

- providing information to the public about prevention of domestic violence and dating violence, including information targeted to underserved populations; and

- collaborating with Indian tribes and tribal organizations (and Native Hawaiian groups or communities) to address the needs of Indian (including Alaska Native) and Native Hawaiian victims of domestic dating violence, as applicable in the state.59

Training and Technical Assistance Centers

As originally enacted, FVPSA authorized a national information and research clearinghouse on the prevention of domestic violence. As part of the act's reauthorization in 1992, the language about the clearinghouse was struck and replaced with authorization for resource centers on domestic violence, including special issue resource centers to address key areas of domestic violence. Reauthorization of FVPSA in 2010 added authorization for a national resource center on American Indian women and three culturally specific resources, which had previously been funded through discretionary funds.60 The 2010 law also authorized special issue resource centers that provide training and technical assistance on domestic violence intervention and prevention topics and state resource centers to address disparities in domestic violence in states with high proportions of Indian (including Alaska Native) or Native Hawaiian populations.61

In total, HHS administers grants for 14 training and technical assistance centers that are funded by the FVPSA appropriation for shelter, services, and support. The purpose of these resource centers is to provide information, training, and technical assistance on domestic violence issues. This assistance is provided by nonprofit organizations and other entities to multiple stakeholders—individuals, organizations, governmental entities, and communities—so that they can improve their capacity for preventing and responding to domestic violence.

Teen Dating Violence

Background

Teenagers may be exposed to violence in their dating relationships. The CDC reports that on an annual basis, 1 in 9 female teens and 1 in 13 male teens experienced physical dating violence involving a person who hurts or tries to hurt a partner by hitting, kicking, or using another type of physical force. Further, over 1 in 7 female teens and nearly 1 in 19 male teens reported experiencing sexual dating violence in the last year, which includes forcing or attempting to force a partner to take part in a sexual act, sexual touching, or a nonphysical sexual event (e.g., sexting) when the partner does not or cannot consent.62

The FVPSA statute references dating violence throughout and uses the definition of "dating violence" that is in VAWA. The term is defined as violence committed by a person who is or has been in a social relationship of a romantic or intimate nature with the victim, and where the existence of the relationship is determined based on the length, type, and frequency of interaction between the persons in it.63

Domestic violence shelters and supportive services funded by FVPSA are intended for adult victims and their children if they accompany the adult into shelter. The law does not explicitly authorize supports for youth victims of dating violence who are unaccompanied by their parents; however, the law does not limit eligibility for shelter and services based on age. Access to domestic violence shelters and supports for teen victims, including protective orders against abusers, varies by state.64 The primary source of support for teen victims under FVPSA is provided via the National Domestic Violence Hotline. The hotline includes the loveisrespect helpline and related online resources. Youth victims can call, chat, or text with peer advocates for support. The loveisrespect website includes a variety of materials that address signs of abuse and resources for getting help.65

Children Exposed to Domestic Violence

Background

FVPSA references children exposed to domestic violence, but does not define related terminology. According to the research literature, this exposure can include children who see and/or hear violent acts, are present for the aftermath (e.g., seeing bruises on a mother's body, moving to a shelter), or live in a house where domestic violence occurs, regardless of whether they see and/or hear the violence. A frequently cited estimate is that between 10% and 20% of children (approximately 7 million to 10 million children) are exposed to adult domestic violence each year.66 The literature about the impact of domestic violence is evolving. The effects of domestic violence on children can range from little or no effect to severe psychological harm and physical effects, depending on the type and severity of abuse and protective factors, among other variables.67

Multiple FVPSA activities address children exposed to domestic and related violence:

- One of the purposes of the formula grant program for states is to provide specialized services (e.g., counseling, advocacy, and other assistance) for these children.68

- The National Resource Center on Domestic Violence is directed to offer domestic violence programs and research that include both victims and their children exposed to domestic violence.

- The national resource center that addresses mental health and trauma issues is required to address victims of domestic violence and their children who are exposed to this violence.

- State domestic violence coalitions must, among other activities, work with the legal system, child protective services, and children's advocates to develop appropriate responses to child custody and visitation issues in cases involving children exposed to domestic violence.

In addition to these provisions, the FVPSA statute authorizes funding for specialized services for abused parents and their children. FVPSA activities for children exposed to domestic violence have also been funded through discretionary funding and funding leveraged through a semipostal stamp.

Specialized Services for Abused Parents and Their Children/Expanding Services for Children and Youth Exposed to Domestic Violence69

Since 2003, FVPSA has specified that funding must be set aside for activities to address children exposed to domestic violence if the appropriation for shelter, victim services, and program support exceeds $130 million.70 Under current law, if funding is triggered, HHS must first reserve not less than 25% of funding above $130 million to make grants to a local agency, nonprofit organization, or tribal organization with a demonstrated record of serving victims of domestic violence and their children. These funds are intended to expand the capacity of service programs and community-based programs to prevent future domestic violence by addressing the needs of children exposed to domestic violence. Funding has exceeded $130 million in FY2010 and FY2014 through FY2019.

In FY2010, funding for shelter and services was just over $130 million. HHS reserved the excess funding as well as FVPSA discretionary funding (under shelter, victim services, and program support) to fund specialized services for children through an initiative known as Expanding Services for Children and Youth Exposed to Domestic Violence. HHS also used discretionary money to fund the initiative in FY2011 and FY2012. Total funding for the initiative was $2.5 million. This funding was awarded to five grantees—four state domestic violence coalitions and one national technical assistance provider—to expand supports to children, youth, and parents exposed to domestic violence and build strategies for serving this population.71 For example, the Alaska Network on Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault, the state domestic violence coalition for Alaska, used the funding to improve coordination between domestic violence agencies and the child welfare system. Their work involved developing an integrated training curriculum and policies, and creation of a multidisciplinary team of child welfare and domestic violence stakeholders in four communities.

Funding again exceeded $130 million in each of FY2014 through FY2019, thereby triggering the set-aside. In FY2014 and FY2015, HHS directed the extra funding for shelter, services, and support.72 In FY2016 through FY2018, HHS provided funding for specialized services for abused parents and their children and expects to continue such funding for FY2019.73 Of the approximately $20 million in excess funding for each of these three years, approximately $5.0 million to $5.6 million was allocated in each year for these services.74 This recent funding has been allocated to 12 grantees to provide direct services under the grant, Specialized Services for Abused Parents and their Children (SSPAC). Grantees include domestic violence coalitions and other entities. They are working to alleviate trauma experienced by children who are exposed to domestic violence, support enhanced relationships between these children and their parents, and improve systemic responses to such families. A separate grant of $500,000 annually—known as Expanding Services to Children, Youth, and Abused Parents (ESCYAP)—has been awarded to the nonprofit organization Futures Without Violence to provide training and technical assistance to the 12 grantees and facilitate coordination among them.75

FVPSA Interaction with Other Federal Laws

In addition to the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), FVPSA has been reauthorized by VAWA and shares some of that law's purposes. In addition, FVPSA interacts with the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) because some FVPSA-funded programs receive VOCA funding to provide legal and other assistance to victims.76 Further, FVPSA includes provisions that encourage or require HHS to coordinate FVPSA programs with related programs and research carried out by other federal agencies.

Child Abuse and Neglect

FVPSA does not focus on child abuse per se; however, in enacting FVPSA as part of the 1984 amendments to CAPTA, some Members of Congress and other stakeholders noted that child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence are not isolated problems, and can arise simultaneously.77 The research literature has focused on this association. In a national study of children in families who come into contact with a public child welfare agency through an investigation of child abuse and neglect, investigative caseworkers identified 28% of the children's households as having a history of domestic violence against the caregiver and 12% of those caregivers as being in active domestic violence situations. Further, about 1 out of 10 of the child cases of maltreatment reported included domestic violence.78

CAPTA provides funding to states to improve their child protective services (CPS) systems. It requires states, as a condition of receiving certain CAPTA funds, to describe their policies to enhance and promote collaboration between child protective service and domestic violence agencies, among other social service providers.79 Other federal efforts also address the association between domestic violence and child abuse. For example, the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program supports efforts to improve the outcomes of young children living in communities with concentrations of domestic violence or child maltreatment, among other factors. The program provides grants to states, territories, and tribes for the support of evidence-based early childhood home visiting programs that provide in-home visits by health or social service professionals with at-risk families.80

Separately, the Family Connection Grants81 program, authorized under Title IV-B of the Social Security Act, provided funding from FY2009 through FY2014 to public child welfare agencies and nonprofit private organizations to help children—whether they are in foster care or at risk of entering foster care—connect (or reconnect) with birth parents or other extended kin. The funds were used to establish or support certain activities, including family group decisionmaking meetings that enable families to develop plans that nurture children and protect them from abuse and neglect, and, when appropriate, to safely facilitate connecting children exposed to domestic violence to relevant services and reconnecting them with the abused parent.82

In addition, HHS and the Department of Justice supported the Greenbook Initiative in the early 2000s. The Greenbook was developed from the efforts of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges,83 which convened family court judges and experts on child maltreatment and domestic violence. In 1999, this group developed guidelines for child welfare agencies, domestic violence providers, and dependency courts in responding to domestic violence and child abuse in a publication that came to be known as the Greenbook. Soon after, HHS and DOJ funded efforts in six communities to address domestic violence and child maltreatment by implementing guidelines from the Greenbook.84 The HHS-led Federal Interagency Working Group on Child Abuse and Neglect includes a Domestic Violence Subcommittee.85 The committee focuses on interagency initiatives that address children exposed to domestic violence and promoting information exchange and joint planning among federal agencies.

Violence Against Women Act (VAWA)86

FVPSA has twice been amended by VAWA. Both FVPSA and VAWA are the primary vehicles for federal support to prevent and respond to domestic violence, including children and youth who are exposed to this violence; however, FVPSA has a more singular focus on prevention and services for victims, while VAWA's unique contributions are more focused on law enforcement and legal response to domestic violence.

VAWA was enacted in 1994 after Congress held a series of hearings on the causes and effects of domestic and other forms of violence against women. Some Members of Congress and others asserted that communities needed a more comprehensive response to violence against women generally—not just against intimate partners—and that perpetrators should face harsher penalties.87 The shortfalls of legal response and the need for a change in attitudes toward violence against women were reasons cited for the passage of the law. Since VAWA's enactment, the federal response to domestic violence has expanded to involve multiple departments and activities that include investigating and prosecuting crimes, providing additional services to victims and abusers, and educating the criminal justice system and other stakeholders about violence against women.

Although VAWA also addresses other forms of violence against women and provides a broader response to domestic violence, some VAWA programs have a similar purpose to those carried out under FVPSA. Congress currently funds VAWA grant programs that address the needs of victims of domestic violence. These programs also provide support to victims of sexual assault, dating violence, and stalking. For example, like the FVPSA grant program for states, territories, and tribes, VAWA's STOP (Services, Training, Officers, Prosecutors) Violence Against Women Formula Grant program provides services to victims of domestic and dating violence (and sexual assault and stalking) that include victim advocacy designed to help victims obtain needed resources or services, crisis intervention, and advocacy in navigating the criminal and/or civil legal system.88 Of STOP funds appropriated, 30% must be allocated to victim services. STOP grants also support activities that are not funded under FVPSA, including for law enforcement, courts, and prosecution efforts. Another VAWA program, Transitional Housing Assistance Grants for Victims of Domestic Violence, provides transitional housing services for victims, with the goal of moving them into permanent housing. Through the grant program to states, territories, and tribes, FVPSA provides immediate and short-term shelter to victims of domestic violence and authorizes service providers to assist with locating and securing safe and affordable permanent housing and homelessness prevention services.

Victims of Crime Act (VOCA)

FVPSA requires that entities receiving funds under the grant programs for states, territories, and tribes use a certain share of funding for selected activities, including assistance in accessing other federal and state financial assistance programs. One source of federal finance assistance for victims of domestic violence is the Crime Victims Fund (CVF), authorized under the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) and administered by the Department of Justice's Office of Victims of Crime (OVC). Within the CVF, funds are available for victims of domestic violence through the Victim Compensation Formula Grants program and Victims Assistance Formula Grants program. The Victims Compensation Grants may be used to reimburse victims of crime for out-of-pocket expenses such as medical and mental health counseling expenses, lost wages, funeral and burial costs, and other costs (except property loss) authorized in a state's compensation statute. In recent years, approximately 40% of all claims filed were for victims of domestic violence. The Victims Assistance Formula Grants may be used to provide grants to state crime victim assistance programs to administer funds for state and community-based victim service program operations. The grants support direct services to victims of crime including information and referral services, crisis counseling, temporary housing, criminal justice advocacy support, and other assistance needs. In recent years, approximately 50% of victims served by these grants were victims of domestic violence.89

Federal Coordination

Both FVPSA, which is administered within HHS, and VAWA, which is largely administered within DOJ, require federal agencies to coordinate their efforts to respond to domestic violence. For example, FVPSA authorizes the HHS Secretary to coordinate programs within HHS and to "seek to coordinate" those programs "with programs administered by other federal agencies, that involve or affect efforts to prevent family violence, domestic violence, and dating violence or the provision of assistance for adults and youth victims of family violence, domestic violence, or dating violence."90 In addition, FVPSA directs HHS to assign employees to coordinate research efforts on family and related violence within HHS and research carried out by other federal agencies.91 Similarly, VAWA requires the Attorney General to consult with stakeholders in establishing a task force—comprised of representatives from relevant federal agencies—to coordinate research on domestic violence and to report to Congress on any overlapping or duplication of efforts on domestic violence issues.92

In 1995, HHS and DOJ convened the first meeting of the National Advisory Council on Violence Against Women. The purpose of the council was to promote greater awareness of violence against women and to advise the federal government on domestic violence issues. Since that time, the two departments have convened subsequent committees to carry out similar work. In 2010, then-Attorney General Eric Holder rechartered the National Advisory Committee on Violence Against Women, which had previously been established in 2006 under his predecessor.93 As stated in the charter, the committee is intended to provide the Attorney General and the HHS Secretary with policy advice on improving the nation's response to violence against women and coordinating stakeholders at the federal, state, and local levels in this response, with a focus on identifying and implementing successful interventions for children and teens who witness and/or are victimized by intimate partner and sexual violence.

Separately, the director for FVPSA programs and the deputy director of HHS's Office on Women's Health provide leadership to the HHS Steering Committee on Violence Against Women.94 This committee supports collaborative efforts to address violence against women and their children, and includes representatives from the CDC and other HHS agencies. The members of the committee have established links with professional societies in the health and social service fields to increase attention on women's health and violence issues. In addition to these collaborative activities, multiple federal agencies participate in the Federal Interagency Workgroup on Teen Dating Violence, which was convened in 2006 to share information and coordinate teen dating violence program, policy, and research activities to combat teen dating violence from a public health perspective. The workgroup has funded a project to incorporate adolescents in the process for developing a research agenda to address teen dating violence.95 Finally, the Office of the Vice President (under Joe Biden) coordinated federal efforts to end violence against women, including by convening Cabinet-level officials to address issues concerning domestic and other forms of violence against women.96

|

Term |

Definition |

|

"Domestic Violence:" The Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA) references the definition under the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 (VAWA), as amended, at 34 U.S.C. §12291(a)(8). |

Felony or misdemeanor crimes of violence committed by a current or former spouse of the victim, by a person with whom the victim shares a child in common, by a person who is cohabiting with or has cohabitated with the victim as a spouse, by a person similarly situated to a spouse of the victim under the domestic or family violence laws of the jurisdiction receiving grant monies, or by any other person against an adult or youth victim who is protected from that person's act under the domestic or family violence laws of the jurisdiction. |

|

"Family Violence:" FVPSA defines this term at 42 U.S.C. §10402(4). |

Any act or threatened act of violence, including any forceful detention of an individual, that (1) results or threatens to result in physical injury; and (2) is committed by a person against another individual (including an elderly individual) to or with whom such person is related by blood, is or was related to by marriage, or was otherwise legally related to, or is or was lawfully residing with. |

|

"Dating Violence:" FVPSA references the definition under VAWA, as amended, at 34 U.S.C. §12291(a)(10). |

Violence committed by a person who has been in a social relationship of a romantic or intimate nature with the victim; and where the existence of such a relationship is determined based on consideration of the length of the relationship, the type of relationship, and the frequency of interaction between the persons involved. |

|

"Elder abuse:" FVPSA references this term, but does not point to a specific definition. The term is defined under VAWA, as amended, at 34 U.S.C. §12291(a)(11). |

Any action against a person who is 50 years of age or older that constitutes the willful infliction of injury, unreasonable confinement, intimidation, or cruel punishment with resulting physical harm, pain, or mental anguish; or deprivation by a person, including a caregiver, of goods or services with intent to cause physical harm, mental anguish, or mental illness. |

|

"Child abuse:" FVPSA references this term, but does not point to a specific definition. The term is defined under the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), at 42 U.S.C. §5101 note. |

At a minimum, any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act that presents an imminent risk of serious harm. |

|

"Stalking:" FVPSA references this term, but does not point to a specific definition. The term is defined under VAWA, as amended, at 34 U.S.C. §12291(a)(30). |

Engaging in a course of conduct directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to (1) fear for his or her safety or the safety of others; or (2) suffer substantial emotional distress. |

|

"Sexual assault:" FVPSA references this term, but does not point to a specific definition. The term is defined under VAWA, as amended, at 34 U.S.C. §12291(a)(29). |

Nonconsensual sexual act proscribed by federal, tribal, or state law, including when the victim lacks capacity to consent. |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS).

Appendix B. Prevalence and Effects of Domestic Violence

Table B-1. Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of Violence

Committed by an Intimate Partner and Related Impacts

National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, 2015

|

Lifetime |

Past 12 Months |

||||

|

Weighted Percentage |

Estimated Number |

Weighted Percentage |

Estimated Number |

||

|

Women |

|||||

|

Any contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or |

36.4% |

43,579,000 |

5.5% |

6,584,000 |

|

|

Contact sexual violence |

18.3% |

21,897,000 |

2.4% |

2,932,000 |

|

|

Physical Violencea |

30.6% |

36,632,000 |

2.9% |

3,455,000 |

|

|

Stalking |

10.4% |

12,499,000 |

2.2% |

2,591,000 |

|

|

IPV-Related Impact |

25.1% |

30,025,000 |

3.0% |

3,635,000 |

|

|

Men |

|||||

|

Any contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or |

33.6% |

37,342,000 |

5.2% |

5,786,000 |

|

|

Contact sexual violence |

8.2% |

9,082,000 |

1.6% |

1,833,000 |

|

|

Physical Violencea |

31.0% |

34,436,000 |

3.8% |

4,255,000 |

|

|

Stalking |

2.2% |

2,485,000 |

0.8% |

918,000 |

|

|

IPV-Related Impact |

10.9% |

12,118,000 |

1.9% |

2,101,000 |

|