Introduction

The Department of the Interior (DOI) is a federal executive department responsible for the conservation and use of roughly three-quarters of U.S. public lands. DOI defines its mission as to protect and manage the nation's natural resources and cultural heritage for the benefit of the American people; to provide scientific and scholarly information about those resources and natural hazards; and to exercise the country's trust responsibilities and special commitments to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and island territories under U.S. administration.1 Initially conceived as a "home department" in 1849 to oversee a broad array of internal affairs,2 DOI has evolved to become the nation's principal land management agency, charged with administering the use of more than 480 million acres of public lands, 700 million acres of subsurface minerals, and 1.7 billion acres of the outer continental shelf (OCS).3

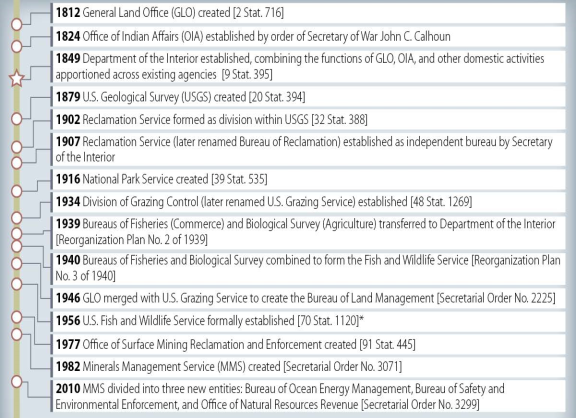

As is the case for many federal departments, DOI's organizational structure and functions are under continual congressional examination as part of Congress's lawmaking and oversight functions. Similarly, DOI's executive branch structure and operations are also the subject of administrative scrutiny. Over the course of the department's roughly 170-year history, DOI has evolved in response to the needs of the nation and at the behest of Congress and the President (see Figure 1 for a timeline of selected events that influenced the current structure of the department). Some of these changes have been relatively broad in nature, such as the creation of a new agency or regulatory body. Other shifts have been smaller in scope, such as modifications to interagency processes or reorganizations in how resources or responsibilities are distributed among offices or programs.4

DOI reorganization proposals put forth by the Trump Administration have renewed attention to the structural relationship between the department's various bureaus and their regulatory responsibilities. In March 2017, President Trump signed an executive order calling on agency leaders to, "if appropriate," submit a proposed reorganization plan for their agencies to the director of the Office of Management and Budget within 180 days.5 In September 2017, then-Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke issued a reorganization proposal for DOI in response to this order. In June 2018, President Trump issued a more expansive government-wide reorganization proposal, which included further recommendations and proposals affecting the structure of DOI.6 In addition to these broader proposals, smaller interagency administrative changes either took effect in FY2019 or are proposed for FY2019 implementation, including the transfer and consolidation of several department offices and programs.

This report is a primer to understanding the organizational framework under which DOI operates, while providing context for how ongoing and proposed reorganizations might affect these operations. The report provides a timeline of congressional and executive actions that have shaped the structure and function of DOI since its establishment. It also offers a brief summary of DOI's history, mission, and current structure, as well as an overview of the primary functions of its multiple bureaus and offices as of December 2018. Employment figures and corresponding maps illustrate the varying regional office structures among DOI bureaus, as they exist currently. In addition, the report includes an overview of the annual funding and appropriations process for the department. Although the report provides a broad summary of the proposed reorganization efforts under way or in effect as of December 2018, it does not offer a detailed analysis of these plans or their potential impact on DOI's structure and function. A list of CRS experts for the issue areas covered by DOI and its bureaus is at the end of the report. In general, this report contains the most recently available data and estimates as of December 2018.

Establishment of the Department: A Brief History

Prior to the establishment of DOI in 1849, Congress apportioned domestic affairs in the United States across the three original executive departments: Department of State, Department of War (now Department of Defense), and Department of the Treasury.7 The Department of State housed the nation's Patent Office, and the Department of War housed the Office of Indian Affairs and the Pension Office, which at the time administered pensions solely for military personnel.8 Meanwhile, the General Land Office (GLO), which oversaw and disposed of the public domain, was placed by Congress within the Department of the Treasury because of the revenue generated by the GLO from land sales.9

By the 1840s, the growing federal estate acquired through the Louisiana Purchase, the Mexican-American War, and the newly negotiated Oregon Territory placed an increasing burden on the departments and their leadership.10 In 1848, then-Secretary of the Treasury Robert J. Walker submitted to Congress a proposal that would bring together GLO, the Office of Indian Affairs, and several other disparate offices and functions under a single, separate executive department.11 Congress officially established the Department of the Interior on March 3, 1849.12

In addition to absorbing the functions of the Patent Office, the Office of Indian Affairs, Pension Office, and GLO, the newly established DOI assumed responsibility for a wide range of other domestic matters. As part of DOI's organic legislation, Congress conferred on the Secretary of the Interior the "supervisory and appellate powers" held by the President over the commissioner of Public Buildings, as well as oversight responsibility for both the U.S. Census and the Penitentiary of the District of Columbia.13 Over time, Congress further expanded the department's functions to include the construction of the national capital's water system, the colonization of freed slaves in Haiti, water pollution control, and the regulation of interstate commerce.14 Most of these early activities eventually were transferred from DOI's charge as Congress began to authorize and create new executive departments and independent agencies to handle this growing list of responsibilities.

Now, DOI has evolved to focus primarily on protecting and managing natural resources, conducting scientific research, and exercising the nation's trust responsibilities to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and affiliated island communities.

DOI Today: Leadership, Structure, and Functions

Overview

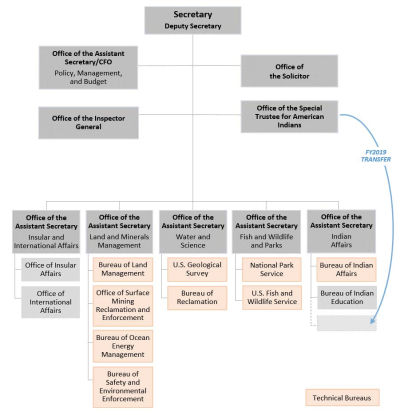

DOI is a Cabinet-level department that employs approximately 65,000 full-time employees across nine technical bureaus and various administrative and programmatic offices.15 In addition to its headquarters in Washington, DC, DOI has staff in roughly 2,400 locations across the United States, including both regional offices and field centers.16 Each of DOI's technical bureaus and programmatic offices has a unique mission and set of responsibilities, as well as a distinct organizational structure that serves to meet its functional duties.17 Figure 2 shows the DOI organization chart as of December 2018.

|

Figure 2. DOI Organizational Chart of Key Positions and Bureaus (as of December 2018) |

|

|

Source: CRS using information from DOI Office of the Secretary: Department-Wide Programs, Budget Justifications and Performance Information Fiscal Year 2019, pp. OS-1, at https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/fy2019_os_budget_justification.pdf. Notes: CFO = Chief financial officer. This chart does not depict every office within the department but rather key positions and bureaus reflected in this report. The FY2019 Budget Justification for the Office of the Special Trustee for American Indians (OST) proposes a change in the reporting relationship of the OST from the Office of the Secretary to the Assistant Secretary—Indian Affairs. This proposed change is reflected here. See "Departmental Offices and Programs" section for more information. |

|

DOI Presidential Appointees Requiring Senate Confirmation Secretary Deputy Secretary Assistant Secretary—Fish, Wildlife, and Parks Assistant Secretary—Insular Affairs Assistant Secretary—Land and Minerals Management Assistant Secretary—Policy, Management, and Budget/Chief Financial Officer Assistant Secretary—Water and Science Assistant Secretary—Indian Affairs Chairperson—National Indian Gaming Commission Special Trustee—American Indians Commissioner—Bureau of Reclamation Director—Bureau of Land Management Director—U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director—National Park Service Director—Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement Director—U.S. Geological Survey Inspector General Solicitor Notes: For a more complete discussion of Senate confirmation process, see CRS Report RL30959, Presidential Appointee Positions Requiring Senate Confirmation and Committees Handling Nominations, by Christopher M. Davis and Michael Greene. |

Leadership

The leadership team and senior executives of DOI provide oversight and guidance for the department's various offices, bureaus, and field locations. The department is administered and overseen by the Secretary of the Interior (referred to in this report as the Secretary) and a Deputy Secretary, who serves in a leadership capacity under the Secretary. The President appoints both positions, and the U.S. Senate confirms them (see text box for a full list of DOI appointees requiring Senate confirmation). Serving under the Secretary and Deputy Secretary are six Assistant Secretaries, who oversee DOI's nine technical bureaus and different administrative and programmatic offices (see Figure 2 for these position titles and responsibilities).18

In addition to the Secretary, the Deputy Secretary, and the six Assistant Secretaries, DOI has a number of other congressionally mandated leadership positions. Like other Cabinet-level agencies, DOI has an inspector general, who administers the office responsible for providing oversight to DOI's programs, operations, and management.19 The DOI solicitor heads the Office of the Solicitor, which provides legal counsel, advice, and representation for the department.20 In 1994, Congress established the position of special trustee for Indian Affairs to manage DOI's fiduciary responsibilities to American Indians.21 Since its establishment, the Office of the Special Trustee (OST) has operated independently from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), which held these responsibilities prior to 1994.22 Finally, the chairperson of the National Indian Gaming Commission oversees an independent regulatory body within DOI responsible for administering and promoting economic development through gaming on Indian lands.23 Similar to the Special Trustee, the chairperson of the commission operates in an independent capacity separate from the Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs.

Technical Bureaus: History, Missions, and Current Structures

Nine technical bureaus comprising more than 90% of the DOI workforce are responsible for implementing the department's mission and responsibilities.24 The names, structures, and duties of these bureaus have evolved over time in accordance with both administrative actions and shifts in the authorities provided to them by Congress. Below is a brief overview of each bureau, the historical context within which it was created, its organizational structure, and its current mission and responsibilities.

Bureaus appear below in alphabetical order. An "At a Glance" box provides a snapshot of key information and data for each respective bureau. The "Established" date reflects the year in which a bureau was created. The "Key Statute" listed may represent the initial legislative authorization for a bureau to carry out its regulatory duties, or it may reference an agency's organic act, which articulates it mission and/or responsibilities. This information does not reflect the full list of governing statutes for DOI bureaus, as each bureau is subject to numerous laws. The number of employees listed for each bureau reflects the average for the four reporting periods from September 2017 to June 2018, with employment figures rounded to the nearest hundred, as reported to OPM. These annual averages differ from the figures included in the narrative sections of each agency, which reflect June 2018 figures, the most recently reported by OPM's Fedscope database as of the publication of this report. DOI employee data are discussed in more detail in the section "DOI Employment."

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)

|

At a Glance: Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) |

|

|

Established: 1824 Key Statute: Snyder Act of 1921 (42 Stat. 208) Mission: "To enhance the quality of life, to promote economic opportunity, and to carry out the responsibility to protect and improve the trust assets of American Indians, Indian Tribes, and Alaska Natives." Leadership: Director Headquarters: Washington, DC Average Staff: 7,600 (including staff from the Bureau of Indian Education) Regions: 12 |

|

|

Source: *Bureau of Indian Affairs, "About Us," at https://www.bia.gov/about-us. |

|

Established in 1824, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is the oldest bureau within DOI, predating the department by 25 years. Then-Secretary of War John C. Calhoun established the Office of Indian Affairs to help centralize what was at the time a fractured administrative approach to Indian policy and relations in the United States.25 It was not until 1832 that Congress officially recognized the Office of Indian Affairs as a bureau of the War Department by appointing a commissioner to oversee the agency.26 The Office of Indian Affairs was transferred to DOI in 1849, when the department was created. DOI formally adopted the name Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1947.27

BIA provides services to federally recognized American Indian and Alaska Native tribes and their nearly 1.9 million members.28 These services include disaster relief, child welfare, and road construction, as well as the operation and funding of law enforcement, tribal courts, and detention facilities within native villages and reservations.29 The bureau also is responsible for protecting and administering assets on tribal lands, including the management of 55 million surface acres and 57 million acres of subsurface mineral estates held in trust by the United States.30

The BIA was also previously responsible for providing elementary and secondary education and educational assistance to Indian children through BIA's Office of Indian Education Programs. In 2006, however, the Secretary of the Interior separated the BIA education programs from the rest of the BIA and placed them in a new Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) under the Assistant Secretary—Indian Affairs.31 As of FY2018, the BIE education system served approximately 47,000 students through 169 elementary/secondary schools and 14 dormitories located in 23 states.32 For the purposes of this report, BIE is not considered a technical bureau of DOI. However, BIE employment figures are included in BIA totals listed above and in the "DOI Employment Levels" section.

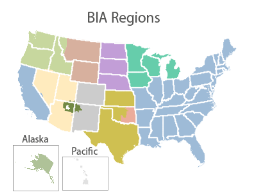

The BIA is administered by a director who oversees the agency's functions and reports to the Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs. Similar to other DOI agencies, the BIA has a three-tiered organizational structure, with leadership and senior executives operating from headquarters in Washington, DC, and 12 regional offices that oversee 53 field offices (referred to as agencies by the BIA); these agencies deliver program services directly to tribal communities.33 As of June 2018, the BIA and BIE combined had roughly 7,000 employees.34

Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

|

At a Glance: Bureau of Land Management (BLM) |

|

|

Established: 1946 Key Statute: Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (90 Stat. 2744) Mission: "To sustain the health, diversity and productivity of public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations."* Leadership: Director Headquarters: Washington, DC Average Staff: 9,800 Regions: 12 (state offices) |

|

|

Source: *BLM, "Our Mission," at https://www.blm.gov/about/our-mission. |

|

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) was created in 1946, following the merger of DOI's General Land Office (GLO) and the U.S. Grazing Service, known previously as the Division of Grazing Control and subsequently as the Division of Grazing.35 BLM manages just under 250 million acres of public land—roughly 10% of the total U.S. land area. The vast majority of this land (more than 99%) is located in 12 western states, including Alaska.36 The agency also is responsible for approximately 800 million acres of the federal onshore subsurface mineral estate and for mineral development on about 60 million acres of Indian trust lands.37 BLM manages public lands under the dual framework of multiple use and sustained yield, as required under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976.38 These uses include a wide range of activities, such as energy and mineral development, livestock grazing, and preservation, as well as hunting, fishing, and other recreational activities.39

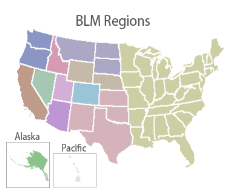

The BLM national headquarters in Washington, DC, is home to the agency's leadership, which provides strategic direction, policy guidance, and oversight of BLM's national-level activities. Twelve state offices—which are akin to the regional office structure of other agencies—carry out BLM's mission within their respective geographical areas of jurisdiction.40 Reporting to these 12 state offices are numerous district offices, which are further divided into localized field offices. Field offices oversee the day-to-day management of public land resources and the on-the-ground delivery of BLM programs and services. BLM also has several national-level support and service centers. As of June 2018, BLM had roughly 10,700 employees.41

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM)

|

At a Glance: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) |

|

|

Established: 2010 Key Statute: Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act of 1953 (67 Stat. 462) Mission: "To manage development of U.S. outer continental shelf energy and mineral resources in an environmentally and economically responsible way."* Leadership: Director Headquarters: Washington, DC Average Staff: 600 Regions: 4 |

|

|

Source: *BOEM, "About BOEM," at https://www.boem.gov/About-BOEM/. |

|

Established in 2010, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) manages development of the nation's energy and mineral resources on the outer continental shelf (OCS). The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA) of 1953 defines the OCS as all submerged lands lying seaward of state coastal waters that are subject to federal jurisdiction, constituting approximately 1.7 billion acres.42 Under OCSLA, the Secretary of the Interior has the authority to manage the development of the OCS.43

Prior to BOEM's establishment, the Secretary delegated the leasing and management authority granted by OCSLA to the DOI agency known as the Minerals Management Service (MMS).44 During its existence, MMS had three primary responsibilities concerning offshore development: resource management, safety and environmental oversight and enforcement, and revenue collection. Following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, concerns about perceived conflicts between these three missions prompted then-Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar to reorganize the agency. MMS was formally abolished, and three new units were established within DOI: BOEM, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), and the Office of Natural Resource Revenue (ONRR).

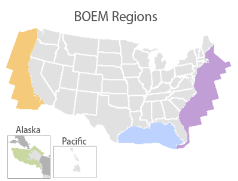

As of June 2018, BOEM employed approximately 500 people to carry out its mission of managing offshore conventional and renewable energy resources on the OCS.45 The agency's leadership in Washington, DC, divides itself between three programmatic offices covering strategic resource development, environmental analysis and applied science, and offshore renewable energy development. Meanwhile, regional offices oversee on-the-ground operations and policy implementation in the four OCS regions in the Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico, the Pacific, and Alaska.46

Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation)

|

At a Glance: Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) |

|

|

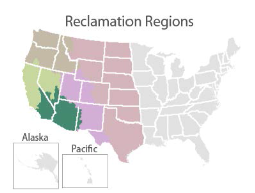

Established: 1902 Key Statute: Reclamation Act of 1902 (32 Stat. 338) Mission: "To manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public."* Leadership: Commissioner Headquarters: Washington, DC Denver, CO (administrative) Average Staff: 5,400 Regions: 5 |

|

|

Source: *Bureau of Reclamation, "About Us—Mission/Vision," at https://www.usbr.gov/main/about/mission.html. |

|

The large-scale construction of federal dams and irrigation projects throughout the 20th century was born, in part, out of a growing need for water supplies in the arid and rapidly expanding western United States.47 To meet this need, Congress passed the Reclamation Act of 1902, which set aside federal dollars to fund irrigation projects in 13 western states.48

Shortly thereafter, Congress established the U.S. Reclamation Service as a program within the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). In its first five years, the service began work on more than 30 projects across the American West. In 1907, the Secretary of the Interior elevated the program to an independent bureau within DOI before renaming it the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) in 1923.49 Since its establishment, Reclamation has constructed or overseen the completion of more than 600 projects across the western United States.50 Beneficiaries of these projects generally repay the costs for construction and operations of these facilities to the federal government over extended terms (in some cases without interest). The exception are costs deemed "federal" in nature, as federal costs are nonreimbursable.51

Whereas Reclamation originally focused almost entirely on building new water storage and diversion projects, the agency now largely focuses on the operation and maintenance of existing facilities.52 Reclamation's mission also has expanded to include support for other efforts to improve water supplies in the western United States, such as promoting water reuse and recycling efforts, desalination projects, and Indian water rights settlements.

A presidentially appointed commissioner oversees the work of Reclamation and, along with other senior-level executives, manages the overall operations of the agency from its headquarters in Washington, DC. Due to the amount of projects and employees based in western states, Reclamation also maintains federal offices in Denver, CO, which administer many of Reclamation's programs, initiatives, and activities. These programs include efforts that address dam safety, flood hydrology, fisheries and wildlife resources, and research programs that seek to improve management and increase water supplies. Meanwhile, five regional offices manage Reclamation's water projects and oversee various local area offices responsible for the day-to-day operations of the nearly 180 projects currently under the agency's authority.53 As of June 2018, Reclamation had roughly 5,500 employees.54

Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE)

|

At a Glance: Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) |

|

|

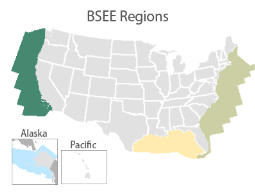

Established: 2010 Key Statute: Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act of 1953 (67 Stat. 462) Mission: "To promote safety, protect the environment, and conserve resources offshore through vigorous regulatory oversight and enforcement."* Leadership: Director Headquarters: Washington, DC Average Staff: 800 Regions: 4 |

|

|

Source: *BSEE, "About Us," at https://www.bsee.gov/who-we-are/about-us. |

|

Following the 2010 restructuring of MMS, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) inherited the safety and environmental enforcement functions previously carried out by MMS. These functions are primarily concerned with the offshore energy industry on the OCS—largely oil and natural gas production. BSEE's responsibilities include regulation of worker safety, emergency preparedness, environmental compliance, and resource conservation.55

BSEE is administered by a director based out of the agency's headquarters in Washington, DC. The agency also has a second headquarters location in Sterling, VA, that oversees many of BSEE's national programs (see below) and provides technical and administrative support for the bureau.56 To carry out the duties of the department, BSEE coordinates between leadership in these two locations and staff operating across three regional offices (serving Alaska, the Pacific, and the Gulf of Mexico OCS regions),57 and five Gulf Coast district offices (Houma, Lafayette, Lake Charles, and New Orleans, LA, and Lake Jackson, TX).58 Senior leadership sets the policies and performance goals implemented at these local offices across the agency's six national programs.59 As of June 2018, BSEE had approximately 800 employees across the United States.60

National Park Service (NPS)

|

At a Glance: National Park Service (NPS) |

|

|

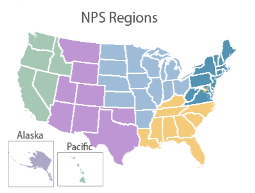

Established: 1916 Key Statute: National Park Service Organic Act of 1916 (39 Stat. 535) Mission: "To preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the national park system for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations."* Leadership: Director Headquarters: Washington, DC Average Staff: 19,700 Regions: 7 |

|

|

Source: *NPS, "About Us," at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/index.htm. |

|

In 1916, the National Park Service Organic Act (Organic Act) centralized administration of the nation's national parks and national monuments. With the Organic Act, Congress created the National Park Service (NPS) and established the agency's dual mandate—to protect the country's natural and cultural resources while providing for their public use and enjoyment.61 In undertaking that mission, NPS administers approximately 80 million acres of federal land, including 418 units that comprise the National Park System across all 50 states and U.S. territories.

Each NPS unit is overseen by a park superintendent, who manages day-to-day administration in accordance with both the agency's mission and any laws and regulations specific to the unit.62 These units and their leadership report to seven regional directors, who oversee park management and program implementation across defined geographic regions. At the national level, NPS is led by a director and senior executives who manage national programs, policy, and budget from the agency's headquarters in Washington, DC.63 As of June 2018, NPS employed roughly 23,000 employees.64

Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE)

|

At a Glance: Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) |

|

|

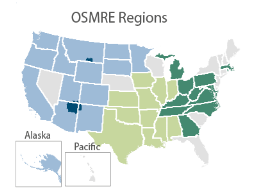

Established: 1977 Key Statute: Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (91 Stat. 445) Mission: "To ensure that coal mines are operated in a manner that protects citizens and the environment during mining and assures that the land is restored to beneficial use following mining, and to mitigate the effects of past mining by aggressively pursuing reclamation of abandoned coal mines."* Leadership: Director Headquarters: Washington, DC Average Staff: 400 Regions: 3 |

|

|

Source: *OSMRE, "Our Mission and Vision," at https://www.osmre.gov/about/MissionVision.shtm. Notes: OSMRE Western Region works with three tribal partners to carry out the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA): the Crow Tribe, the Hopi Tribe, and the Navajo Nation. These partners are represented by the dark blue sections of the Regional Map above but do not together comprise a separate region. |

|

The Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) was established as a bureau within DOI following passage of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) in 1977.65 The law provided the new agency with the statutory authority to carry out and administer a nationwide program aimed at regulating coal mining in the United States. In particular, OSMRE works with states and tribal communities to reclaim abandoned coal mines, and regulate active surface coal mining operations to minimize adverse impacts to the environment and local communities. SMCRA also authorizes OSMRE to issue federal payments to the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) coal mineworker health benefits plans.66

OSMRE serves as the lead regulatory authority over surface coal mining and reclamation activities for states and tribal communities under the authority granted by Title V of SMCRA.67 SMCRA does, however, allow OSMRE to delegate regulatory primacy to states and tribes upon demonstration that a given state or tribe has established regulatory requirements consistent with federal standards.68 Although OSMRE operates in an oversight capacity for states that have established such regulatory primacy, no tribe has attained this delegated authority to date (although tribes are eligible to seek regulatory primacy as well).69

OSMRE fulfills its missions through a three-tiered organizational structure: headquarters in Washington, DC; three regional Offices (Appalachian, Mid-continent, and Western Offices); and multiple area and field Offices that report directly to the regional offices.70 OSMRE is the smallest of DOI's technical bureaus, employing approximately 400 people nationwide as of June 2018.71

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)

|

At a Glance: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) |

|

|

Established: 1940 Key Statute: Fish and Wildlife Act of 1956 (70 Stat. 1120) Mission: "To conserve, protect and enhance fish, wildlife and plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people."* Leadership: Director Headquarters: Washington, DC Falls Church, VA Average Staff: 8,700 Regions: 8 |

|

|

Source: *FWS, "About the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service," at https://www.fws.gov/help/about_us.html. |

|

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) is the principal federal agency tasked with the conservation, protection, and restoration of fish, wildlife, and natural habitats across the United States and its insular territories. The history of FWS can be traced back to the creation of two now-defunct agencies in the late 1800s: the U.S. Commission on Fish and Fisheries in the Department of Commerce and the Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy in the Department of Agriculture.72 These two agencies were transferred to DOI in 1939 and subsequently consolidated, creating a single agency known at the time as the Fish and Wildlife Service.73 In 1956, Congress established the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.74

The FWS has a primary-use mission "to conserve, protect and enhance fish, wildlife and plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people."75 Among its responsibilities, FWS manages the National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS) under the authority granted by the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act of 1966.76 The NWRS is a network of lands and waters set aside to conserve the nation's fish, wildlife, and plants that has grown to include more than 560 refuges, 38 wetland management districts, and other protected areas. More than 836 million acres of lands and waters comprise the NWRS; of these lands and waters, 146 million acres are classified as National Wildlife Refuges.77

In addition, FWS, along with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the Department of Commerce, is responsible for implementing the Endangered Species Act (ESA).78 The ESA aims to protect species that are in danger of becoming extinct or could be in danger of becoming extinct in the near future.79 FWS also assists in international conservation efforts, enforces federal wildlife laws, and administers grant funds to states and territories for fish and wildlife programs.

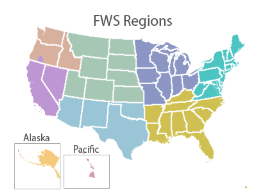

Similar to most DOI agencies, FWS has a three-tiered organizational structure comprised of national, regional, and local field offices across the United States. The headquarters office—led by an agency director—is split between two locations in Washington, DC, and Falls Church, VA, which together have primary responsibility for policy formulation and budgeting across the agency's 13 major program areas.80 Eight regional offices oversee FWS field offices and science centers across the United States and U.S. territories, which implement these policies and programs at the local level.81 As of June 2018, FWS had roughly 9,000 employees across the country.82

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

|

At a Glance: U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) |

|

|

Established: 1879 Key Statute: Organic Act of 1879 (20 Stat. 394) Mission: "To serve the Nation by providing reliable scientific information to describe and understand the Earth; minimize loss of life and property from natural disasters; manage water, biological, energy, and mineral resources; and enhance and protect our quality of life."* Leadership: Director Headquarters: Reston, VA Average Staff: 8,100 Regions: 7 |

|

|

Source: *USGS, "Who We Are," at https://www.usgs.gov/about/about-us/who-we-are. |

|

In 1878, the National Academy of Sciences issued a report to Congress asking Congress to provide a plan for surveying and mapping the western territories of the United States.83 In response, Congress passed an appropriations bill the following year that authorized the creation of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Congress established the USGS for the express purpose of overseeing the "classification of the public lands, and examination of the geological structure, mineral resources, and products of the national domain."84 The authorities and responsibilities of USGS have shifted and evolved over time, with many of its prior activities leading to the formation of new governmental agencies.85 Today, however, USGS serves as the science agency of DOI, providing physical and biological information across seven interdisciplinary areas: (1) water resources, (2) climate and land use change, (3) energy and minerals, (4) natural hazards, (5) core science systems, (6) ecosystems, and (7) environmental health.86 Unlike other DOI bureaus, USGS has no regulatory or land management mandate.

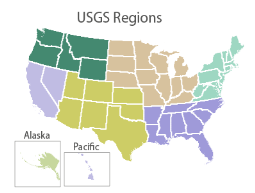

In addition to its seven programmatic areas, USGS is further organized into seven geographic regions, each under the supervision of a regional director. The regional directors report to a presidentially appointed director based out of the agency's headquarters in Reston, VA. Within each region, USGS operates science centers, laboratories, and field offices that monitor, assess, and conduct research on a wide range of topics.87 Overall, USGS had roughly 8,000 employees as of June 2018.88

Departmental Offices and Programs89

In addition to the nine technical bureaus, DOI has multiple departmental offices that provide leadership, coordination, and services to the department's various bureaus and programs. These offices coordinate department-wide activities and oversee specialized functions under DOI's jurisdiction not administered directly at the bureau level.

Office of the Secretary

The Office of the Secretary provides leadership for the entire department through the development of policy and through executive oversight of the annual budget and appropriations process. The Office of the Secretary also manages the administrative operations of DOI, including (but not limited to) financial services, information technology and resources, acquisition, and human resources. In addition, the Office of the Secretary manages six other department-wide programs, offices, and revolving funds:

- 1. Central Hazardous Materials Fund provides remediation services to national parks, national wildlife refuges, and other DOI-managed lands impacted by hazardous substances. This remediation process follows the guidelines established under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA)—also known as the Superfund statute.90

- 2. Natural Resource Damage Assessment and Restoration program coordinates and oversees DOI's restoration efforts for DOI-managed lands impacted by oil spills or the release of hazardous substances. In partnership with federal, state, and tribal co-trustees, the program conducts damage assessments, planning, and restoration implementation on DOI lands.

- 3. Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR) is responsible for the collection, accounting, and verification of any natural resource and energy revenue generated from federal and Indian leases and royalty payments. (See "Bureau of Ocean Energy Management" section for the history behind ONRR's creation.)

- 4. Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) program makes payments to nearly 1,900 local government units across the United States and its insular areas where certain federal lands are located. The PILT payments are intended to help offset the loss in property taxes to local governments caused by the presence of federal lands, which largely are exempt from taxation.91

- 5. Wildland Fire Management program is responsible for addressing wildfires on public lands. The program is comprised of the Office of Wildland Fire and the four DOI land management bureaus with wildland fire management responsibilities (BIA, BLM, FWS, and NPS).92

- 6. Working Capital Fund (WCF) is a revolving fund that finances centralized administrative services and systems to DOI bureaus and offices.93 The WCF aims to reduce duplicative systems and staff across DOI; it provides financing for centralized functions that provide payroll, accounting, information technology, and other support services.

Office of the Solicitor

In 1946, Congress established the Office of the Solicitor to provide advice, counsel, and legal representation to DOI.94 The office manages DOI's Ethics Office and resolves Freedom of Information Act appeals. To accomplish this work, the Office of the Solicitor employs more than 400 employees, 300 of whom are licensed attorneys.95 The Office of the Solicitor is organized into the Immediate Office of the Solicitor, the Ethics Office, five legal divisions, an administrative division, and eight regional offices.96

Office of the Inspector General

In 1978, Congress established inspector general positions and offices in more than a dozen specific departments and agencies, including DOI.97 The mission of the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) is to provide independent oversight and accountability to the programs, operations, and management of the department. OIG has three primary office divisions: (1) the Office of Management serves as the administrative arm; (2) the Office of Investigations conducts, supervises, and coordinates internal investigations on a variety of potential abuses; and (3) the Office of Audits, Inspections, and Evaluations reviews DOI programs and operations for effectiveness and evaluates the financial statements and expenditures of these programs.98 The OIG also operates three regional offices, located in Herndon, VA; Lakewood, CA; and Sacramento, CA.

Office of the Special Trustee for American Indians

The American Indian Trust Fund Management Reform Act established the Office of the Special Trustee for American Indians (OST) in 1994.99 The OST provides fiduciary oversight and management of the more than 55 million surface acres and 57 million subsurface mineral acres of tribal assets held in trust by the federal government.100 The office carries out its mission from a national office in Washington, DC, and through five regional offices across the nation.101

The OST operates independently from BIA, which carried out these trust responsibilities prior to the 1994 legislation. However, in 2016, Congress passed the Indian Trust Asset Reform Act (ITARA) requiring the Secretary to prepare "a transition plan and timetable for the termination of the Office of the Special Trustee" within two years.102 Although OST still exists, the 2019 Budget Justification proposes transferring some of the functions of OST to other DOI agencies and offices to comply with the reorganization requirements mandated by Congress in ITARA.103 The Budget Justification also includes a proposal to have OST—and the appointed Special Trustee—report directly to the Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs starting in FY2019.104 More information regarding this change in OST organizational structure and function is provided in the "DOI Reorganization Plans and Proposals: Issues for Congress" section.

Office of Insular Affairs

The United States acquired its first insular territories in 1898 with the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands and the acquisition of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines from Spain following the Spanish-American War.105 For much of the early 20th century, territorial oversight of these new possessions fell largely to the War Department. In 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Division of Territories and Island Possessions to centralize responsibility for coordinating oversight of the nation's insular regions.106 The division—now known as the Office of Insular Affairs—currently administers federal oversight of American Samoa, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, with the goal of promoting their economic, social, and political development.107 The office also administers federal assistance and U.S. economic commitments to the Freely Associated States: the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau.108

DOI Employment Levels

As of June 2018, the total number of employees working for DOI was 69,563, according to OPM (see Table 1).109 The data reflect "on-board employment" figures, which calculate the number of employees in pay status at the end of the quarter. Data are published on a quarterly basis (March, June, September, and December); however, figures for September and December 2018 were not available prior to the publication of this report. Because OPM data include full-time, part-time, and seasonal staff, employment totals tend to spike during the summer months, when agencies such as NPS, BLM, and FWS increase their seasonal workforce.

OPM figures differ from DOI Budget Office data. The DOI Budget Office calculates employment by full-time equivalents (FTEs), defined as the total number of regular straight-time hours (not including overtime or holiday hours) worked by employees, divided by the number of compensable hours applicable to each fiscal year.110

|

Agency |

Sep-17 |

Dec-17 |

Mar-18 |

Jun-18 |

Average Totals |

|||||

|

Bureau of Land Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Bureau of Reclamation |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Bureau of Safety & Environmental Enforcement |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Indian Affairs |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

National Park Service |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Office of the Inspector General |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Office of the Secretary of the Interior |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Office of the Solicitor |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Office of Surface Mining Reclamation & Enforcement |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

U.S. Geological Survey |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total—Department of the Interior |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM), FedScope database, Employment cubes, Cabinet-Level Agencies parameter set to Department of the Interior, at https://www.fedscope.opm.gov/.

Notes: Numbers reflect employees on board (in a pay status). Figures may not add up to totals shown due to rounding. "Indian Affairs" is meant to include the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE). Per data provided to CRS from DOI, "Office of the Secretary of the Interior" includes employees from the Office of Insular Affairs, Office of the Special Trustee for American Indians, and the various Assistant Secretaries Offices that oversee DOI bureaus and agencies.

The OPM Fedscope data presented in Table 1 are available by location of employment for each bureau and office reflected. Table 2 shows DOI employment figures both within and outside the DC core-based statistical area (CBSA). OPM defines a CBSA as "a geographic area having at least one urban area of population, plus adjacent territory that has a high degree of social and economic integration with the core as measured by commuting ties."111 CBSAs differ from metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs)—a separate statistical definition also reported on by OPM—which typically encompass a smaller geographic area than CBSAs. For example, the DC MSA includes many but not all of the counties and surrounding cities covered under the DC CBSA. For instance, the DC MSA excludes Reston, VA, where the headquarters of USGS is located.112

Table 2. DOI Employment: Inside vs. Outside the DC Core-Based Statistical Area (CBSA)

(as of June 2018)

|

Agency |

Inside DC CBSA |

Outside DC CBSA |

Total Employment |

% Inside DC CBSA |

||||

|

Bureau of Land Management |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Bureau of Reclamation |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Bureau of Safety & Environmental Enforcement |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Indian Affairs |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

National Park Service |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Office of the Inspector General |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Office of the Secretary of the Interior |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Office of the Solicitor |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Office of Surface Mining Reclamation & Enforcement |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

U.S. Geological Survey |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Totals—Department of the Interior |

|

|

|

|

Source: OPM, FedScope database, Employment Trend cubes, Cabinet-Level Agencies parameter set to Department of the Interior, at https://www.fedscope.opm.gov/.

Notes: Data reflect places of employment for DOI staff, not places of residence. Included in the DC CBSA figures are DOI staff considered to be based out of headquarters as well as administrative, regional, and field staff based within the boundaries of the geographic definition. For example, National Park Service staff who work at the National Mall and Memorial Parks unit in Washington, DC, are considered field staff but are included in the DC CBSA figures. "Indian Affairs" is meant to include the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE). Per data provided to CRS from DOI, "Office of the Secretary of the Interior" includes employees from the Office of Insular Affairs, Office of the Special Trustee for American Indians, and the various Assistant Secretaries Offices that oversee DOI bureaus and agencies.

Overview of DOI Appropriations

Discretionary funding for DOI is provided primarily through Title I of the annual Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies appropriations bill.113 The Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) and the Central Utah Project are the exceptions, as they receive funding through the Energy and Water Development appropriations bill.114 Several of the agencies that receive discretionary funds through these two appropriations bills also receive mandatory funding under various authorizing statutes.

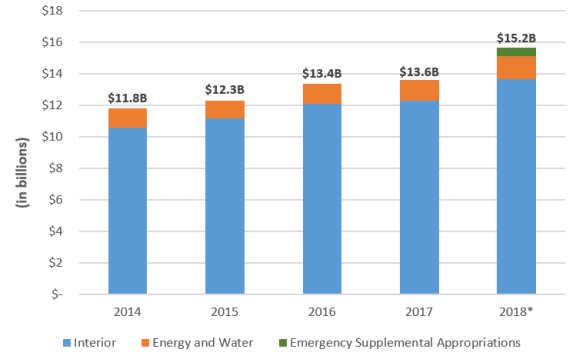

DOI Discretionary Appropriations: FY2014-FY2018115

Figure 3 shows the budget trends for both the Interior and the Energy and Water appropriations bills over the past five fiscal years (FY2014-FY2018). From FY2014 to FY2018, total DOI appropriations increased 29% in current dollars. This increase includes the $566 million in FY2018 emergency supplemental appropriations for disaster relief appropriated to DOI in P.L. 115-72 and P.L. 115-123. If supplemental appropriations are not considered, total DOI appropriations increased 23% over the same period.116

|

Figure 3. DOI Discretionary Appropriations: FY2014-FY2018 (in current dollars) |

|

|

Sources: CRS, with data from the annual Interior Budget in Brief for FY2016-FY2019. Figures for each of FY2014-FY2017 were taken from the volume published two years following the fiscal year in question (e.g., for FY2014, figures are from FY2016 document). FY2018 figures are from data provided to CRS by the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. Notes: Totals include rescissions and transfers authorized by the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies and the Energy and Water Development appropriations bills. Figures reflect Emergency Supplemental Appropriations for FY2018, which include $50 million enacted as part of the Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-72), and $516 million enacted as part of the Further Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-123, Division B, Subdivision I). |

DOI Discretionary Appropriations: FY2018 by Agency

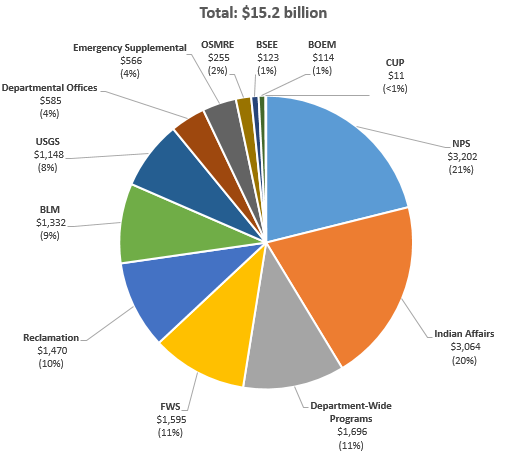

Figure 4 shows the breakdown of enacted FY2018 appropriations for DOI bureaus, offices, and programs funded through the Interior and the Energy and Water appropriations bills. Figures are presented in total dollars (in millions) and as percentages of the department's $15.2 billion in enacted appropriations for FY2018. Supplemental emergency appropriations for FY2018 are shown as a separate segment of the total DOI budget; however, these funds were distributed across several DOI bureaus and programs.

|

Figure 4. DOI Discretionary Appropriations for FY2018, by Agency (in millions) |

|

|

Sources: Prepared by CRS with data from the House Appropriations Committee. Supplemental figures taken from the Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-72), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123). Notes: Figures may not add to total shown due to rounding. Per the Interior Budget in Brief for FY2019, "Indian Affairs" is meant to include the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE), and the Office of the Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs (AS-IA); "Departmental Offices" includes funding for the Office of the Secretary, Insular Affairs, Office of the Solicitor, Office of Inspector General, and the Office of the Special Trustee for American Indians; "Department-Wide Programs" includes funding for Wildlife Fire Management, Central Hazardous Materials Fund, Natural Resource Damage Assessment Fund, Working Capital Fund, and Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT). Additional abbreviations are (clockwise): Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), Central Utah Project (CUP), National Park Service (NPS), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE). |

DOI Reorganization Plans and Proposals: Issues for Congress

Executive branch reorganization efforts are an ongoing area of congressional interest and scrutiny as part of Congress's lawmaking and oversight functions. Congress uses a variety of tools—including authorizing legislation, appropriations legislation, and oversight activities—to shape and organize the executive branch and its agencies.117

Several changes to DOI and its organizational structure have taken effect starting in FY2019. Congress previously authorized and approved some of these changes and proposals in the form of appropriations and/or authorizing legislation. Other changes—including broader reorganization proposals put forth by the Trump Administration—have been proposed for FY2019 but are not in effect.

The 115th Congress approved several internal office transfers and realignments. For instance, Congress transferred appropriations for the Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR) from DOI's Office of the Secretary to Department-Wide Programs for FY2018.118 Meanwhile, the 2019 Interior Budget in Brief reflects the transfer of both DOI's Oceans Program and the Office of International Affairs from the Office of the Assistant Secretary, Policy, Management and Budget to the Office of the Assistant Secretary, Insular and International Affairs.119

The 114th Congress passed legislation authorizing the reorganization of the Office of the Special Trustee for American Indians (OST). In 2016, ITARA directed the Secretary to—among other things—"ensure that appraisals and valuations of Indian trust property are administered by a single bureau, agency, or other administrative entity within the Department" not later than 18 months after enactment.120 To comply with this requirement, the FY2019 budget request reflects the approved transfer of the Office of Appraisal Services within OST to the Office of the Secretary's Appraisal and Valuation Services Office, thereby consolidating all appraisal activities within a single entity.121 This change is in addition to a proposed shift in the reporting relationship of OST also included in the FY2019 request. Under this proposal, starting in FY2019, OST would report through the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs rather than directly to the Office of the Secretary (see Figure 2).122

As noted in the "Introduction" to this report, the Trump Administration also proposed additional, broader DOI reorganizational plans for consideration. On March 13, 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13781 to "improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability of the executive branch."123 The order required executive agency heads to, "if appropriate," submit a proposed reorganization plan for their agencies to the director of the Office of Management and Budget within 180 days. Then-Secretary of the Interior Zinke subsequently submitted a proposal for reorganization aimed at—among other goals—improving agency coordination and service to the public.124 Included in this proposal is a plan to consolidate the various agency-specific regional boundaries (as seen in the "At a Glance" boxes included in each bureau summary) into 12 Unified Regional Boundaries. In addition, the plan looks to shift some resources and authority "to the field," potentially in the form of staff, budget, and/or facilities.

President Trump issued a separate set of reorganization recommendations in June 2018 as part of the Delivering Government Solutions in the 21st Century report.125 Two proposals in particular would affect DOI and its structure. The first would consolidate most of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' (USACE's) Civil Works Division within DOI, including USACE's activities related to flood and storm damage reduction and aquatic ecosystem restoration.126 The second recommendation would transfer NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service from the Department of Commerce to DOI and merge it with the FWS. This proposal would consolidate administration of the ESA and other wildlife laws under one agency.127

The transfers and reorganization proposals discussed here illustrate the potential changes in the structure of DOI and its operations. They also provide insight into areas of possible congressional and executive branch interest moving forward. The 116th Congress may consider additional oversight of these proposals and/or propose new initiatives and plans for the organization and administration of DOI and its bureaus.